Many of the record-setting number of women running for political office in the 2018 midterm elections emphasized their feminine strengths to gain an advantage with voters. For example, Kelda Roys, a candidate for Wisconsin governor, aired a campaign ad featuring her breastfeeding her child. Female candidates can emphasize the feminine advantage they bring to the table by talking about being mothers (Deason, Greenlee, and Langer Reference Deason, Greenlee and Langer2015), presenting themselves as more honest and less corrupt than typical politicians (Barnes, Beaulieu, and Saxton Reference Barnes, Beaulieu and Saxton2018b), or prioritizing issues that reflect the stereotypic issue strengths of women (Herrnson, Lay, and Stokes Reference Herrnson, Lay and Stokes2003). Emerging female candidates see feminine stereotypes as a strength. It is not clear whether these feminine-focused campaign strategies resonate positively with voters.

One perspective argues that female candidates can leverage feminine stereotypes to their advantage (Herrnson, Lay, and Stokes Reference Herrnson, Lay and Stokes2003; Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Valentino, Ansolabehere, Simon and Norris1996). For example, female candidates can benefit from stereotypes about women as more honest in the wake of a corruption scandal (Barnes and Beaulieu Reference Barnes and Beaulieu2014). Another perspective argues that emphasizing feminine stereotypes leads voters to see female candidates as unqualified for political office (Ditonto Reference Ditonto2017). Feminine stereotypes characterize women as lacking the knowledge needed for political office (Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2014). A third perspective argues that stereotypic feminine messages have no effect on how voters make decisions about female candidates (Brooks Reference Brooks2013; Dolan Reference Dolan2014). There is no clear consensus about how voters respond to messages reinforcing feminine stereotypes. One reason for this ambiguity, I argue, is that current approaches do not distinguish between messages that emphasize feminine traits and messages that emphasize feminine issues.

I resolve the conflict about the role of feminine stereotypes in voter decision-making through a unique theoretical and methodological approach. My theoretical approach is unique in that I draw on role congruity theory and theories of political leadership to identify how voters will respond to messages that emphasize feminine traits versus messages that emphasize feminine issues. I isolate the effects of feminine traits and feminine issues through the use of experiments so that I can trace the effects of these types of messages on voter decision-making. Previous approaches use observational data examining the content of campaign ads or candidate websites (see, e.g., Dolan Reference Dolan2014; Schneider Reference Schneider2014b), but this method cannot offer insights into how voters respond to feminine messages because it is not possible to determine with complete certainty whether people actually saw the campaign ads. This study is certainly not the first to use an experiment to trace the effects of stereotyping (see, e.g., Bauer Reference Bauer2015b; Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Valentino, Ansolabehere, Simon and Norris1996), but it is among the first to separately isolate the roles of traits and issues in voter decision-making. I also integrate theories about partisan stereotypes with theories of gender stereotypes, in doing so, build on a growing body of scholarship testing how these stereotypes intersect (Bauer Reference Bauer2018a; Cassese and Holman Reference Cassese and Holman2018; Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2016).

I delineate the effects of trait-based and issue-based feminine messages through two survey experiments. The results uncover several novel findings that contribute to research on campaign strategy, gender stereotypes, partisan stereotypes, and voter decision-making. First, I show that voters do not respond similarly to all types of messages that hew to feminine stereotypes. Second, I find that trait-based feminine messages activate feminine stereotypes, while issue-based messages do not activate these stereotypes. Third, trait-based messages undermine perceptions of women as leaders, while issue-based messages do not. Fourth, the results suggest there may be differences across female candidate partisanship in voter responses to trait-based feminine messages. This research lends insight into which strategies help female candidates combat gender biases at the polls and which messages exacerbate gender biases.

FEMININE STEREOTYPES IN VOTER DECISION-MAKING

Feminine stereotypes characterize women as caring, compassionate, and sensitive and as more likely to engage in supportive or communal activities. Masculine stereotypes characterize men as aggressive, tough, and strong and as more likely to engage in assertive or agentic behaviors (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002; Koenig et al. Reference Koenig, Eagly, Mitchell and Ristikari2011). Gender stereotypes, in a political context, broaden to include policy issues. Stereotypic women's issues include health care, social welfare policy, and pay equity; stereotypic men's issues include defense, foreign policy, and national security (Alexander and Anderson Reference Alexander and Anderson1993; Herrnson, Lay, and Stokes Reference Herrnson, Lay and Stokes2003; Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993; Petrocik, Benoit, and Hansen Reference Petrocik, Benoit and Hansen2003; Schneider Reference Schneider2014a). Candidates can activate stereotypes through feminine traits and/or feminine issues.

Extant scholarship offers conflicting conclusions about whether campaign strategies that hew to feminine stereotypes benefit or disadvantage female candidates. Several studies find that voters respond positively to female candidates who emphasize feminine traits or issues (Barnes and Beaulieu Reference Barnes and Beaulieu2014; Herrnson, Lay, and Stokes Reference Herrnson, Lay and Stokes2003; Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Valentino, Ansolabehere, Simon and Norris1996; Kahn Reference Kahn1994). For example, female candidates benefit from their perceived expertise on stereotypically feminine issues when these policy issues top the electoral agenda (Herrnson, Lay, and Stokes Reference Herrnson, Lay and Stokes2003; Kahn Reference Kahn1994). Other studies find that voters respond negatively to campaign messages that emphasize feminine traits or issues (Bauer Reference Bauer2015b; Ditonto Reference Ditonto2017). Finally, a third approach finds that campaign strategies that emphasize feminine traits or issues have little effect on voter decision-making (Brooks Reference Brooks2013), in part because partisanship factors more heavily into vote choice (Dolan Reference Dolan2014). There is no clear consensus about how voters respond to campaign strategies that highlight feminine stereotypes.

Current scholarship treats feminine issues and feminine traits as equal sources of stereotypic information. Scholars assume that if feminine issue strategies benefit female candidates, then feminine trait strategies will also benefit female candidates. There is reason to be skeptical of this conclusion. Cassese and Holman (Reference Cassese and Holman2018), for example, find that feminine trait attacks hurt female candidates, but feminine issue attacks leave female candidates relatively unscathed. This finding suggests that voters think about feminine issues and feminine traits in very different ways. Feminine traits contribute to the perception that female candidates have a high level of expertise on stereotypic women's issues (Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993), but emphasizing feminine traits can increase the perceived incongruity between women and leadership roles (Bauer Reference Bauer2015b; Ditonto Reference Ditonto2017). It may be that voters connect feminine traits to the broader stereotypes about women as ill suited for political office, but voters may respond more positively to messages about feminine issues.

This article builds on work identifying the complex relationship between gender and partisan stereotypes (Bauer Reference Bauer2018b; Sanbonmatsu and Dolan Reference Sanbonmatsu and Dolan2009; Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2016). Stereotypes about women, including trait and issue stereotypes, align with stereotypes about Democrats, and stereotypes about men align with stereotypes about Republicans (Hayes Reference Hayes2011; Winter Reference Winter2010). The intersection between gender stereotypes and partisan stereotypes means that feminine trait and feminine issue messages can affect Democratic and Republican female candidates in different ways (Bauer Reference Bauer2018a). Highlighting feminine issues or feminine traits may benefit Democratic female candidates because these qualities overlap with partisan stereotypes (Winter Reference Winter2010). Republican female candidates may not benefit from strategies that highlight feminine stereotypes because these qualities break with partisan stereotypes.

FEMININE TRAITS AND FEMININE ISSUES—WHAT'S THE DIFFERENCE?

I integrate research from social psychology with political science research on voter decision-making to delineate why and how voters will respond differently to feminine issue messages relative to feminine trait messages. I argue that messages about feminine traits activate broader feminine stereotypes, while messages about stereotypically feminine issues do not activate these stereotypes. This distinction is subtle but important. Feminine traits lead voters to see female candidates as lacking the qualities needed for leadership, but feminine issues lead voters to think about a female candidate's performance in office.

Role congruity theory argues that stereotypes about women and stereotypes about men developed from the observance of women and men in separate and distinct social roles (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002). The observance of women in communal social roles, such as caring for children, led to the development of the stereotype that women are compassionate and kind (Prentice and Carranza Reference Prentice and Carranza2002). Therefore, being a woman with feminine traits is congruent with serving in communal roles. Likewise, the observance of men in agentic social roles, such as being a political leader, led to the development of the stereotype that men are assertive and authoritative (Koenig et al. Reference Koenig, Eagly, Mitchell and Ristikari2011). A female candidate who emphasizes feminine traits activates the intrinsic association between being female and serving in supportive roles rather than serving in political leadership roles. Emphasizing feminine traits can increase the extent to which voters see female candidates as having a high level of expertise on stereotypically feminine issues (Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993), but trait-based feminine messages will lead voters to see female candidates as lacking the qualities needed to serve in leadership roles. Issue-based feminine messages, I argue, will not have this effect.

There are two reasons why issue-based messages will not activate feminine stereotypes. First, issue-based messages are part of the broader set of strategies that candidates, both male and female, use to develop relationships with constituents, signal legislative priorities, and secure reelection (Fenno Reference Fenno1978; Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974). Issue-based gender stereotypes certainly relate to the communal roles performed by women, but I suggest that emphasizing feminine issues will not undercut female candidates. Issue-based feminine messages tell voters which types of policies a female candidate will prioritize as a political leader (Alexander and Anderson Reference Alexander and Anderson1993; Dunaway et al. Reference Dunaway, Lawrence, Rose and Weber2013; Holman Reference Holman2013; Kahn Reference Kahn1994; Schneider Reference Schneider2014a). For example, prioritizing education will lead voters to think that the female candidate will prioritize other issues that affect children such as health care if she is elected to political office and that, as a legislator, the candidate will sponsor bills related to those issues. Feminine traits, however, draw attention to the personal qualities of the female candidate as a woman (Bauer Reference Bauer2015c; Bos Reference Bos2015; Ditonto Reference Ditonto2017). Hearing a female candidate described as caring, for example, may lead a voter to think she will prioritize issues such as health care, but these feminine traits will also lead a voter to associate the candidate with other feminine traits, such as being weak or passive and lacking masculine qualities, that fit with what voters want in political leaders, such as being assertive or decisive (Bauer Reference Bauer2015b; Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2014).

Second, for female candidates, feminine issue messages send important signals to voters about representation (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999). Talking about issues that fit into women's stereotypic strengths that are also issues that disproportionately affect women signal to voters that this is a candidate who will substantively represent women in the legislature. Feminine issue messages, unlike feminine trait messages, may also be interpreted as a message about collective representation. Interpreting feminine issue messages as the priorities of a candidate and as signals about collective representation both require voters to think about how the candidate will perform in a leadership role and not whether the candidate can fill a leadership role. The first prediction is that trait-based feminine strategies will more strongly activate broader feminine stereotypes relative to issue-based feminine strategies.

This first prediction focuses on the effects of trait-based versus issue-based feminine messages for just female candidates. Differences should occur in the effects of trait-based messages across candidate sex. The congruity between being male and serving in a leadership role is so strong that highlighting qualities inconsistent with masculine conceptions of political leadership should not lead voters to see men as ill qualified for political leadership (Bauer Reference Bauer2018a; Bauer and Carpinella Reference Bauer and Carpinella2018). Issue-based feminine messages should not activate feminine stereotypes for either female or for male candidates because issue-based messages do not activate role congruity considerations. My second prediction is that emphasizing feminine traits will activate feminine stereotypes more strongly for female candidates compared with male candidates who also engage in trait-based feminine strategies.

These first two predictions argue that feminine trait messages will activate feminine stereotypes, while feminine issue messages will not. The next prediction turns to identifying how trait-based and issue-based messages affect how voters see female candidates as political leaders. Feminine traits do not fit with the more masculine traits that voters associate with political leadership; therefore, trait-based feminine strategies will lead voters to see female candidates as lacking critical leadership qualities (Bauer Reference Bauer2015c). Issue-based feminine strategies will not undermine how voters evaluate female candidates as leaders because these types of messages lead voters to think about the performance of female candidates as leaders. The congruity between being male and being a leader means that trait-based feminine messages will not harm male candidates. I predict that emphasizing feminine traits will reduce electoral support for female candidates but not male candidates, and emphasizing feminine issues will not reduce electoral support for either female or male candidates.

The Role of Female Candidate Partisanship

The intersection of partisan stereotypes with gender stereotypes can lead voters to respond differently to messages disseminated on behalf of a Democratic female candidate relative to a Republican female candidate. There are several ways that gender and partisan stereotypes could affect voter responses to trait-based and issue-based feminine messages. First, there may be differences in the effects of feminine trait messages based on the partisanship of a female candidate. The overlap between feminine stereotypes and partisan stereotypes may protect Democratic female candidates from the negative role incongruity effects of feminine trait messages. Recent work shows that Republican female candidates who violate partisan expectations receive more negative evaluations relative to Democratic female candidates who also violate partisan expectations (Bauer Reference Bauer2018a). Following this research, I predict that emphasizing feminine traits will adversely affect Republican female candidates relative to Democratic female candidates because these qualities are not only inconsistent with leadership role stereotypes but are also inconsistent with partisan stereotypes.

Issue-based messages can also affect Democratic and Republican female candidates in different ways. Issue-based messages may provide a greater boost to Democratic female candidates because these messages affirm existing beliefs about the issue strengths of these candidates (Herrnson, Lay, and Stokes Reference Herrnson, Lay and Stokes2003; Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Valentino, Ansolabehere, Simon and Norris1996). Another approach, however, argues that breaking with partisan stereotypes to highlight issues associated with the opposing political party benefits candidates (Petrocik, Benoit, and Hansen Reference Petrocik, Benoit and Hansen2003). Because issues are not strongly tied to the role congruity expectations voters hold for political leaders, I predict that there will be few differences in how voters respond to the issue-based feminine messages of Republican female candidates relative to Democratic female candidates.

EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

Using a series of survey experiments, I test how voters respond to trait-based and issue-based feminine messages. An experiment is appropriate because the method has a high level of internal validity (Morton and Williams Reference Morton and Williams2010). Observational analyses lend insight into whether candidates highlight feminine stereotypes in campaign messages, but these analyses cannot capture whether voters see and use this information directly in their decision-making. Thus, experiments are the best method for tracing voter responses to certain types of messages.

I use two experiments with the same basic structure but with different experimental samples. The first study manipulates feminine strategies (issues or traits) along with candidate sex (male or female). The second study only manipulates the type of feminine strategy that a candidate used, feminine issues or feminine traits, and does not manipulate candidate sex. Both experiments matched participants into conditions in which they saw a message from a candidate with whom they shared partisanship. Democratic participants saw a message about a Democratic candidate and Republican participants saw a message about a Republican candidate. Independent participants selected the party they lean more closely toward. This shared partisanship offers a more conservative estimate of any negative effects that might come from highlighting feminine traits or feminine issues. In the first study, I collapse the conditions across partisanship because of low statistical power. This second study has a slightly higher level of statistical power than the first study, which allows me to test the differences in the effects of feminine messages across female candidate partisanship.Footnote 1Table 1 lists the full set of conditions across these two studies.

Table 1. Experimental conditions

Note: I fielded Study 2 in November 2016. Participants only evaluated candidates with whom they shared partisanship.

The studies emphasize the same traits and issues. The feminine trait manipulation described the candidate as caring, sensitive, compassionate, and nurturing. The use of these traits comes from existing research on the attributes of stereotypes about women and men (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002; Koenig et al. Reference Koenig, Eagly, Mitchell and Ristikari2011), and candidates often use these traits in campaign communication (Bauer Reference Bauer2015a; Fridkin and Kenney Reference Fridkin and Kenney2015; Schneider Reference Schneider2014b). The feminine issue manipulation highlighted the candidate's focus on education, health care, social welfare, and the environment. These issue manipulations come from existing research on the gendered nature of issue ownership (Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993; Petrocik, Benoit, and Hansen Reference Petrocik, Benoit and Hansen2003; Schneider Reference Schneider2014a). I embedded the trait and issue manipulations in a newspaper clip that provided a brief update about the candidate's Senate race. Each condition uses the same basic text with only the traits and issues changed. Using a newspaper article to embed the manipulation enhances the external validity of the experiments because voters learn about candidates from the news (Darr Reference Darr2016).Footnote 2

I conducted a pre-test to be sure that the feminine issues and feminine traits fit into broader stereotypes about women; and I include the full results in Appendix B online. The pre-test determined the assignment of the issues and traits as feminine following the approach of the partisan stereotype literature. This approach determines partisan ownership based on 60% of participants associating a specific issue or trait with a political party (Petrocik Reference Petrocik1996). If at least 60% of participants indicated that women were better at an issue or a trait, I classified it as a feminine issue. The issues and traits in the manipulations are similar in content to common measures used to manipulate and measure partisan stereotypes (Petrocik, Benoit, and Hensen Reference Petrocik, Benoit and Hansen2003). This overlap is intentional and benefits my research design. Other research used this approach to discern differences in the effects of different types of messages across female candidate party (Bauer Reference Bauer2018a; Cassese and Holman Reference Cassese and Holman2018). The intersection of partisan and gender stereotypes may lead to differences in feminine trait and issue strategies for female candidates of different political parties.

Study 1 uses an adult convenience sample recruited through Amazon's Mechanical Turk (MTurk), and Study 2 uses a national sample of U.S. adults recruited through Survey Sampling International (SSI). Studies find that these samples produce results comparable to nationally representative samples. The sample characteristics of the studies are comparable to one another in terms of participant sex and partisanship though the MTurk sample is somewhat younger than the SSI sample.Footnote 3

I include a measure of feminine stereotype activation adapted from psychology research (Rudman, Greenwald, and McGhee Reference Rudman, Greenwald and McGhee2001) and used extensively in political science work on candidate stereotyping (Bauer Reference Bauer2015b; Cassese and Holman Reference Cassese and Holman2018 Holman, Merolla, and Zeckmeister Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2016; Krupnikov and Bauer Reference Krupnikov and Bauer2014). The scale, while it is not an implicit measure of stereotypes, is designed to measure “the automatic concept-attribute associations that are thought to underlie implicit stereotypes” (Rudman, Greenwald, and McGhee Reference Rudman, Greenwald and McGhee2001, 1165). The measure consists of a series of semantic differential items that ask participants to place each candidate on scales ranging from strong to weak, harsh to lenient, and hard to soft. One end of each scale item aligns with feminine stereotypes (weak, lenient, caring, warm, and soft), and the other end aligns with masculine stereotypes (strong, harsh, distant, cold, and hard).Footnote 4 If voters think about feminine traits through role incongruity, then the feminine trait condition should more strongly activate broader stereotypes about women, while the feminine issue condition should not activate these broader stereotypes. The final measure averages the scale items, and I recode the final variable to range from 0 to 1, where values closer to 1 indicate a stronger association with feminine stereotypes and values closer to 0 indicate no feminine stereotype activation.

Trait-based feminine messages will decrease the evaluations that female candidates receive as political leaders. Talking about feminine traits, such as being caring, sensitive, and nurturing, does not fit with the stereotypes that voters hold of political leaders, and this lack of fit will lead to a negative effect on the leadership evaluation variable. To assess this effect, I asked participants to rate female candidates on a set of leadership qualities.Footnote 5 Participants rated the extent to which the candidate was a strong leader, competent, and experienced. I combined these three items into a single leadership scale.Footnote 6 I chose these qualities because voters prioritize these traits in political leaders (Bauer Reference Bauer2017; Conroy Reference Conroy2015; Holman, Merolla, and Zeckmeister Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2016; Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993) and because voters see female candidates as lacking these qualities (Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2014). Feminine traits, if the results follow from the prediction, will lead voters to see female candidates as lacking strong leadership, competence, and experience compared with strategies that focus on feminine issues.

STUDY 1 RESULTS

I start by testing whether there is a difference in the extent to which trait-based and issue-based feminine messages activate broader feminine stereotypes.Footnote 7 I expect that emphasizing feminine traits will increase the salience of feminine stereotypes, but emphasizing feminine issues will not activate these broader cultural stereotypes. The stereotype activation effect from trait-based feminine messages should be larger for female candidates relative to male candidates. I conduct two types of comparisons using the stereotype activation scale. First, I compare the extent to which feminine stereotypes are active and salient considerations within the candidate sex conditions but across the trait and issue messages for female and male candidates. Second, I compare the stereotype activation levels for the female candidate relative to the male candidate in the feminine trait and then the feminine issue condition.Footnote 8

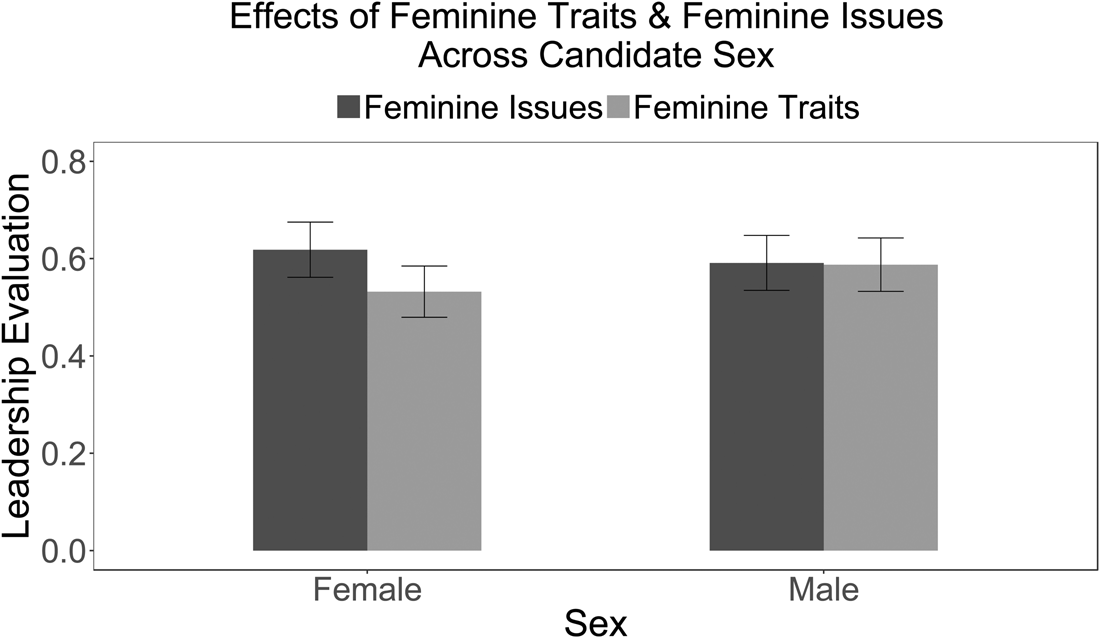

Figure 1 displays the levels of feminine stereotype activation in the female and male feminine issue and trait conditions. Values closer to 1 indicate a higher association with feminine stereotypes, whereas values closer to 0 indicates that feminine stereotypes are not a very active consideration in the minds of voters. Because the variable ranges from 0 to 1, I report differences across the conditions in terms of percentage change to better understand the magnitude of the effect. There are several findings of note in Figure 1. First, in the female candidate condition, trait-based feminine messages (M = 0.66, SD = 0.12) lead to a stronger, 8% (SE = 0.02), spike in feminine stereotype activation relative to issue-based feminine messages (M = 0.58, SD = 0.10), p < .001. This result fits with the theoretical expectations. Second, trait-based feminine messages (M = 0.63, SD = 0.12) relative to issue-based messages (M = 0.55, SD = 0.09) lead to an 8.3% (SE = 0.02) increase in feminine stereotype activation in the male candidate condition, p < .001.

Figure 1. Feminine stereotype activation and candidate sex. 95% confidence intervals included.

Up to this point, the comparisons suggest that trait-based feminine messages increase feminine stereotype activation for both female and male candidates. The key is whether the feminine stereotype activation is stronger in the female condition relative to the male condition. The salience of feminine stereotypes in the trait-based conditions is 3.2% (SE = 0.02) higher in the female condition compared with the male condition, p < .0780. This difference across candidate sex reinforces my theoretical premise that feminine traits activate feminine stereotypes that characterize women as lacking the qualities needed for political leadership, while issue-based feminine messages do not trigger this association.

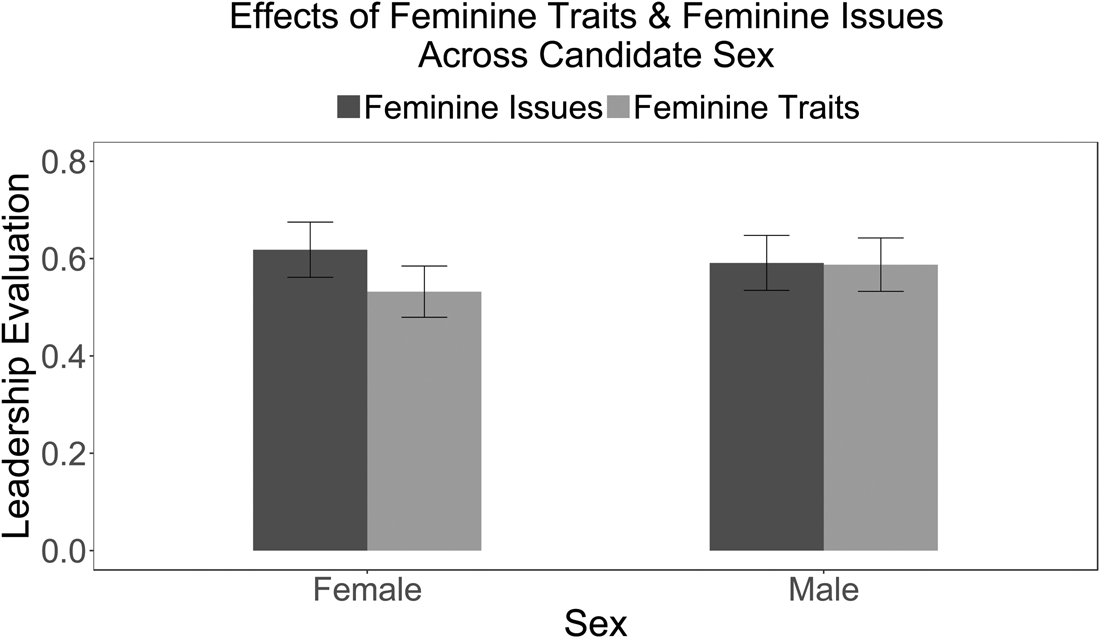

Female candidates, I argue, should receive more negative evaluations on the leadership evaluation scale in the trait-based condition relative to the issue-based condition. I suggest that this negative effect will occur because the feminine traits explicitly referenced in the messages do not fit with the more masculine expectations voters hold for political leaders. Figure 2 displays the average leadership rating of each candidate in the feminine trait and feminine issue conditions on a scale from 0 to 1. Several key patterns emerge from these results. First, the female candidate receives an evaluation that is 9% (SE = 0.04) lower in the feminine trait condition (M = 0.53, SD = 0.25) relative to the feminine issue condition (M = 0.62, SD = 0.26), p = .0305. The negative effect of feminine traits matches the theoretical expectations. Second, it does not matter whether the male candidate emphasizes feminine traits or feminine issues. The male candidate's leadership rating is the same across the trait-based (M = 0.59, SD = 0.25) and the issue-based (SD = 0.59, SD = 0.26) conditions, p = .9255. Third, there is no difference in the leadership rating of the female candidate relative to the male candidate in the issue-based feminine condition, p = .5089. The lack of differences across candidate sex suggests that emphasizing feminine issues might not give female contenders a unique feminine advantage over male opponents.

Figure 2. Effects of feminine traits and feminine issues on leadership evaluations across candidate sex. 95% confidence intervals included.

This first study finds that feminine trait messages relative to feminine issue messages activate feminine stereotypes when the message is on behalf of a female candidate. Messages reinforcing feminine issues do not activate feminine stereotypes. Additionally, the results show that feminine trait messages lead voters to rate female candidates less positively as leaders relative to feminine issue messages.

STUDY 2 RESULTS

The second study investigates how partisanship affects the way voters respond to trait-based and issue-based feminine messages.Footnote 9 The intersection of gender and partisan stereotypes can lead to differences in how voters process trait and issue information about a Democratic female candidate relative to a Republican female candidate. Stereotypes about Democrats align with stereotypes about women, and this alignment could protect Democratic female candidates from a feminine stereotype activation effect.Footnote 10

Figure 3 shows how trait-based and issue-based feminine messages activate feminine stereotypes for Democratic and Republican female candidates with the full group means included in Appendix F online. There is no difference in the effect of trait-based (M = 0.56, SD = 0.19) and issue-based (M = 0.51, SD = 0.13) messages about a Republican female candidate, p = .1444. There are differences in how participants responded to trait-based and issue-based feminine messages on behalf of a Democratic female candidate. Messages that emphasize feminine traits relative to feminine issue messages lead to a stronger spike, 6.2% (SE = 0.021), in feminine stereotype activation looking at comparisons for just Democratic female candidates, p = .0039.

Figure 3. Feminine stereotype activation for Democratic and Republican female candidates. 95% confidence intervals included.

These different patterns suggest that partisan stereotypes could affect how voters respond to the trait-based messages of Democratic and Republican female candidates. To test the role of female candidate partisanship, I estimated an analysis of variance (ANOVA) model with an interaction between the type of message and female candidate partisanship is appropriate. Appendix F, Table A5 online includes this model. The interaction between female candidate party and type of message does not reach significance, but there is a significant main effect for the trait-based feminine message condition—suggesting that trait-based messages activate feminine stereotypes for Democratic and Republican female candidates and that partisanship may not affect the way voters connect feminine traits to broader feminine stereotypes.

Next, I turn to examining whether there are differences across female candidate partisanship in the effects of trait-based and issue-based feminine messages on the leadership evaluations of female candidates. Figure 4 shows the Democratic and Republican female candidate's average ratings in the trait-based and issue-based feminine conditions using the leadership scale. There are no statistically significant differences in the main effects of feminine traits (M = 0.52, SD = 0.19) relative to feminine issues (M = 0.51, SD = 0.21) for Democratic female candidates, p = .7617, using t-test comparisons. This result suggests that emphasizing feminine traits does not undermine or reduce the leadership evaluation of the Democratic female candidate.

Figure 4. Effects of feminine traits and feminine issues on leadership evaluations across female candidate party. 95% confidence intervals included.

The Republican female candidate's rating decreases by 7.6% (SE = 0.044) on the leadership scale in the trait condition relative to the issue condition, and this difference is marginally significant, p = .0887. This decline suggests that voters may view trait-based feminine messages through the lens of role incongruity and not through the lens of political leadership. If partisanship moderates the effects of trait-based feminine messages for female candidates, then there should be a significant interaction between the type of message and candidate party. I estimated ANOVA models with the appropriate interaction, and the appropriate constituent terms of the interaction; I include the full results of these models in Appendix F, Table A5 online and summarize the results here. The interaction between type of message and party is not statistically significant, p = .1194. There is no significant main effect for the feminine trait condition, p = .2306, but there is a marginally significant main effect for the Democratic Party condition variable, p = .0751. This suggests that voters see both feminine trait and feminine issue messages through the lens of Democratic partisan stereotypes, which reinforce feminine stereotypes more generally (Winter Reference Winter2010).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Together, the results show that voters think about feminine traits and feminine issues in very different ways. The question about whether female candidates gain an advantage from stereotypes associated with their sex depends on the type of “feminine” strategy. Trait-based strategies activate feminine stereotypes and reduce the leadership evaluations of female candidates. The studies conducted here lack the statistical power to test for a mediation relationship between the activation of feminine stereotypes and the negative effect that occurs in the trait-based conditions on the leadership evaluation measure for female candidates. Previous research suggests that activating feminine stereotypes may indirectly contribute to this negative effect (Bauer Reference Bauer2015b, Reference Bauer2015c). Testing the mediating influence of feminine stereotype activation, especially across female candidate partisanship, is a key way that future research can build upon the work started here.

This article focuses on traits and issues as strategies female candidates can use to highlight their feminine strengths. These are not the only strategies female candidates can use that highlight their sex and associated stereotypes about women. For example, female candidates can use images of children and families to evoke feminine stereotypes (Bauer and Carpinella Reference Bauer and Carpinella2018), or female candidates can emphasize maternal identities (Deason, Greenlee, and Langer Reference Deason, Greenlee and Langer2015). More work on identifying the strategies that female candidates use on the campaign trail can lend insight into what it means to “run as a woman” and what effect these strategies have on voter decision-making. Some feminine strategies, such as emphasizing motherhood, may activate feminine stereotypes that can undermine a female candidate's chances for electoral success, whereas strategies that highlight the integrity of women can boost electoral success (Barnes, Beaulieu, and Saxton Reference Barnes, Beaulieu and Saxton2018a).

Identifying differences in how voters respond to feminine strategies of Democratic and Republican female candidates is an important next step in future research. A way to build on this work is to identify more robust samples of Democratic and especially Republican participants to better identify effects. There is a wide partisan gap in women's representation, with Democratic women far outpacing Republican women. Republican female candidates face unique campaign obstacles, including the perceived lack of ideological fit between being female and being Republican (Thomsen Reference Thomsen2015) and the inability of Republican women to attract campaign donations (Crowder-Meyer and Cooperman Reference Crowder-Meyer and Cooperman2018). Republican female candidates may face greater constraints in the types of feminine messages they can disseminate because of the incongruence between gender and partisan stereotypes (Bauer Reference Bauer2018b; Hayes Reference Hayes2011; Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2016).

The intersection of gender and race can create unique challenges and unique opportunities for women of color (Ghavami and Peplau Reference Ghavami and Peplau2012). Analyses of the barriers facing minority women running at the congressional level find that these candidates face a “double disadvantage” because of their marginalized status as both women and minorities (Gershon Reference Gershon2012). At the same time, black female or Latina candidates may gain more leverage from feminine stereotypes because the intersection of gender and racial stereotypes can protect them from a role incongruity effect. Running as a black woman or a Latina can be a “double advantage” (Bejarano Reference Bejarano2013; Brown Reference Brown2014). Voters may respond positively to women of color who rely on trait-based feminine messages because voters frequently stereotype these candidates as having both feminine and masculine qualities (Cargile Reference Cargile, Brown and Gershon2016; Cargile, Merolla, and Schroedel Reference Cargile, Merolla, Schroedel, Navarro, Hernandez and Navarro2016). Scholars should also examine how gender stereotypes affect other marginalized groups such as the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer community (Bergersen, Klar, and Schmitt Reference Bergersen, Klar and Schmitt2018; Doan and Haider-Markel Reference Doan and Haider-Markel2010).

There are many ways female candidates can highlight their strengths, and some of these strategies will resonate more positively with voters compared with others. The women entering the political pipeline bring a diverse and unique set of experiences, perspectives, and strategic appeals. Some of the campaign strategies that focus on feminine stereotypes will be more effective than other strategies. The key is that female candidates need to leverage their status as women in ways that do not activate broader stereotypes about women as lacking the qualities needed for holding political office. Female candidates must persuade voters that they have the qualities voters desire in political leaders. The extent to which female candidates can accomplish this goal successfully ultimately affects broader representation of women in political institutions.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view the supplementary appendices for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X19000084