INTRODUCTION

The aim of this article is to examine the effect of political change on labour relations. In this case study we encounter the state both as an actor and implementer of political change as well as being itself the product of a process of political change. It covers approximately a hundred years between 1840 and 1940 and examines three cities: Ankara, Bursa, and Salonica. The primary focus throughout will be the state, or polities in general, as employers, and their role in constituting labour relations. However, the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire and the nation-building processes that led to the formation of the Greek and Turkish nation states are the historical common ground upon which imperial polities or nation states not only facilitated labour relations as employers within their respective populaces, but also actually crafted their national populations.

It is essential from the outset to explain the limitations of the available data and concomitantly narrow scope of this undertaking. While the labour relations categories of the Global Collaboratory on the History of Labour Relations are powerful tools for comparing shifts in labour relations across time and space, the limitations of the occupational data used for this study mean that those tools are unsuitable and so will not be used. Later in this introduction I will delineate the data sources and the methodology developed for their use, before doing so I must explain what I could not do. For this article I used three sets of sources: an Ottoman tax survey from the mid-nineteenth century, and one Turkish and one Greek census from the twentieth century. The Ottoman survey has the advantage of providing individual occupational titles, but unfortunately those titles are difficult to code into the Collaboratory’s categories of labour relations. The chief problem is that for most occupations it is impossible to differentiate between self-employed individuals, employers, and sometimes employed; this creates such a high level of ambiguity that the precise labour relations must remain unclear. The explanatory capability of the taxonomy of labour relations cannot therefore be fully utilized in this case. The rare and invaluable detail of the uncoded individual occupational titles can thus be both a blessing and a curse.Footnote 1 Finally, I opted to code the occupational titles into a customized version of the 1935 Turkish population census for the purposes of compatibility. More importantly, it is a more efficient methodology for reaching the main goal of this study, which is to detect shifts in the employment of people working for the polities of the cities chosen as they changed from being part of the Ottoman Empire to being part of the separate Greek and Turkish states during the period from the 1840s to the 1940s.

The occupational data to be found in the early twentieth-century Greek and Turkish national censuses are coded into generic categories, so it is not possible to extract individual occupational titles or labour relations in order to compare them with the mid-nineteenth century data. Until the 1950s, categories of occupations in Turkish censuses did not differentiate labour relations, with occupations instead grouped into broad categories according to fields of economic activity. Among the categories, we see that “public services” stands out, since it records the specific labour relation of “working for the state”. All other categories are ambiguous about labour relations in general and about working for the state in particular, and it is because of that limitation of the sources that the focus here will be on public service occupations. However, “public services” must then be reinterpreted and extended to create a more inclusive category for the mid-nineteenth century Ottoman urban setting. That is why I have used the category “public utility services” as a proxy to examine inclusion of Ottoman urban dwellers in such employment – or their exclusion from it. For the first half of the twentieth century, Greek and Turkish census data on occupations are also suitable to use for the same categories of public utility services; this enabled me to compare not only urban settings in the mid-nineteenth century, but also the effects of nation-state-building policies. That was possible because the data cover not only occupations, but also the people in them within public utility services in the same cities in the mid-twentieth century. What the data reveal are the especially profound effects on employment chances of religion and gender combined, as well as the effects of national differences on chances of occupational advancement and exclusion in these two examples of state-making.

This article focuses on occupational changes in the urban economies of three cities, Ankara, Bursa, and Salonica, between the 1840s and the 1940s. During that century, each of these cities experienced extreme social and demographic change resulting from radical political transformations. In the 1840s, the inhabitants of these cities had diverse ethno-religious affiliations and lived under the political rule of the Ottoman central authority. In the 1940s, Ankara was the capital of Turkey and Bursa an important urban industrial centre; by then, the populations of the two cities had almost entirely lost their non-Muslim and non-Turkish elements. Ankara’s state apparatus has employed large numbers of both civilian and military personnel ever since. Salonica in the late 1920s still had a very large Jewish community, yet all other non-Christian and, to a great extent, non-Greek elements of the urban population did not survive the political shift from the Ottoman Empire to the Greek state in 1913. After the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922,Footnote 2 both Salonica and Athens saw a huge influx of Orthodox ChristianFootnote 3 immigrants from Turkey, as a result of the compulsory population exchange between Greece and Turkey in 1923. The Greek capital, Athens, was the final destination of most of those migrating to Greece and was where the state apparatus employed most of its servants. In the following sections, therefore, Athens, too, has been included in the analysis for 1928. There is, therefore, a comparative perspective on the respective capacities of the Turkish and Greek bureaucracies to create employment shortly after the 1923 population exchange. However, the rest of the study will be focused on Ankara, Bursa, and Salonica, for which purpose public-sector employment will have a broader meaning to refer to more than just the group of civil servants working for the apparatus of the national state or the municipality. It will, in fact, include the men and women living in the cities who actually provided the public utility services, such as religious, educational, and health services, and served in the administration at local and neighbourhood level. That includes the job of neighbourhood headman, security agents in the neighbourhoods and marketplaces, and membership of military units or the fire brigade. I believe that this categorization is more useful when applied to the mid-nineteenth century Ottoman polity as well as to the Greek and Turkish nation states of the 1930s.

Two sources were used. First, a detailed Ottoman tax survey, the temettuat,Footnote 4 conducted in 1844 and 1845,Footnote 5 for Ankara, Bursa, and Salonica, and secondly the national censuses of Greece, for 1928, and of Turkey, for 1927, 1935, and 1945. There are two parts to the study. The first examines the occupational data and ethno-religious characteristics of the inhabitants of the same three cities in 1845 and tries to compare the dynamics behind employment in the public utility services in those cities by taking into consideration occupational choices as well as residential patterns at the neighbourhood level. The results of that investigation were then mapped. Meanwhile, the second part focuses on the drastic demographic changes that followed the 1923 population exchangeFootnote 6 and how those changes affected employment in general and public utility services in particular for men and women living in Ankara/Bursa and Salonica/Athens.

A TALE OF THREE CITIES, 1845–1945

In the nineteenth century, the Ottoman state had a pluralistic structure and in both the capital, Istanbul, and in other urban centres religious and communal authorities were part and parcel of the diverse polity of what was a multi-ethnic and multi-religious empire. The Ottoman Empire achieved extraordinary longevity and through the centuries its polity went through enormous changes and successfully absorbed major crises. The Ottoman dynasty and the central state authority maintained control for more than 500 years between the end of a short interregnum in 1413 and the end of its empire after World War I. As for the three cities selected for examination here, they were integrated into the Ottoman Empire quite early, with Bursa actually the birthplace of the Ottoman state structure. The Byzantine city of Prousa (modern-day Bursa) became the first capital of the newly created Ottoman state in the fourteenth century and Ankara did not acquire its socio-economic urban qualities as early as Bursa, although it was central to the Anatolian core region of the empire throughout its existence. Ankara developed into an important urban centre in the nineteenth century, and then, in 1923, after the end of the Ottoman Empire, it became the capital of the successor state, the Turkish Republic. Salonica had been incorporated into the empire in 1430 and remained an Ottoman city until 1913. By the 1840s, all these cities, with their long histories in the empire, were important constituting urban centres of Ottoman social and economic life. An important point to note here is that all three of the cities suffered catastrophic events in the early twentieth century that tore apart their urban socio-economic fabric, something especially true for the Jews of Salonica under German occupation during World War II. These calamities involved fires, earthquakes, and man-made disasters, such as deportations, forced migration, and ethnic cleansing, and there were other social-engineering projects implemented by new nation states and occupying forces. The table below lists some indicators of economic development for the second half of the nineteenth century, and important dates of destruction from the twentieth century, for all three cities.

Table 1 Turning points and demographic shocks in the history of the cities.

OCCUPATIONS AND ETHNO-RELIGIOUS CHARACTERISTICS OF THE CITIES IN THE MID-NINETEENTH CENTURY

The micro data on occupational titles derived from the 1845 Ottoman tax survey are very rich in detail but are not coded and so not aggregated, which is a major limitation. However, the fact that the data are available at all can be seen as an advantage, for two reasons. First, it is, of course, still possible to make comparisons across time for Ottoman or Turkish cities by coding the Ottoman data into the occupational categories of the Turkish national censuses from the twentieth century. Secondly, the Ottoman data can likewise be coded into internationally accepted and utilized schemes of occupational classifications, specifically HISCO (Historical International Standard Classification of Occupations), developed by the International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam,Footnote 7 and PSTI (Primary-Secondary-Tertiary International), originally developed by the Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure and subsequently adopted by INCHOS, the International Network for the Comparative History of Occupational Structure.Footnote 8

However, it is unfortunate that for the twentieth century the occupational data contained in the 1928 Greek census are unsuitable for conversion into either HISCO or PSTI. More importantly, no uncoded individual micro data are available for either Greek or Turkish cases, and those data are available only as aggregated cross-tabulations. As a result, for the comparative purposes of this study neither HISCO, nor PSTI but the coding scheme for the 1935 Turkish national census was used to convert the occupational data from the 1845 Ottoman survey and the data given in the 1928 Greek census.

As can be traced in the table above, the inhabitants of the cities experienced drastic social-engineering projects. We can conclude that Salonica’s population went through Hellenization and that the inhabitants of Ankara and Bursa experienced Turkification and Islamification. In the 1840s, the populations of the cities had diverse ethno-religious characteristics, and nation-state-making was not then in operation. The Ottoman tax survey of 1845 used the household as its data collection unit, and it gives detailed information about both the ethno-religious characteristics and the occupations of heads of households for each of the three cities. In numerous cases, more than one gainfully employed male (including brothers or sons of household heads) was registered per household along with their occupations and income-yielding assets. Nevertheless, a lack of regularity and uniformity means it is impossible to conclude that every man with an income or an occupation was included in the survey. In that sense, 1845 is a pre-census survey, for it did not achieve universal coverage. As a result, there is a mismatch in the units of data collection between the 1845 survey and the twentieth-century Greek and Turkish national censuses, which were based on personal data from individuals rather than households. However, for our purposes – a two-stage comparison among the three cities in 1845 and then in the twentieth century – that change in the unit of comparison is not problematic. Real incompatibility would arise only if one wished to treat the datasets as if they constituted a unified panel dataset and make percentual or distributional comparisons of occupations across time among cities between the 1840s and the 1940s; that is not the intention of this paper.

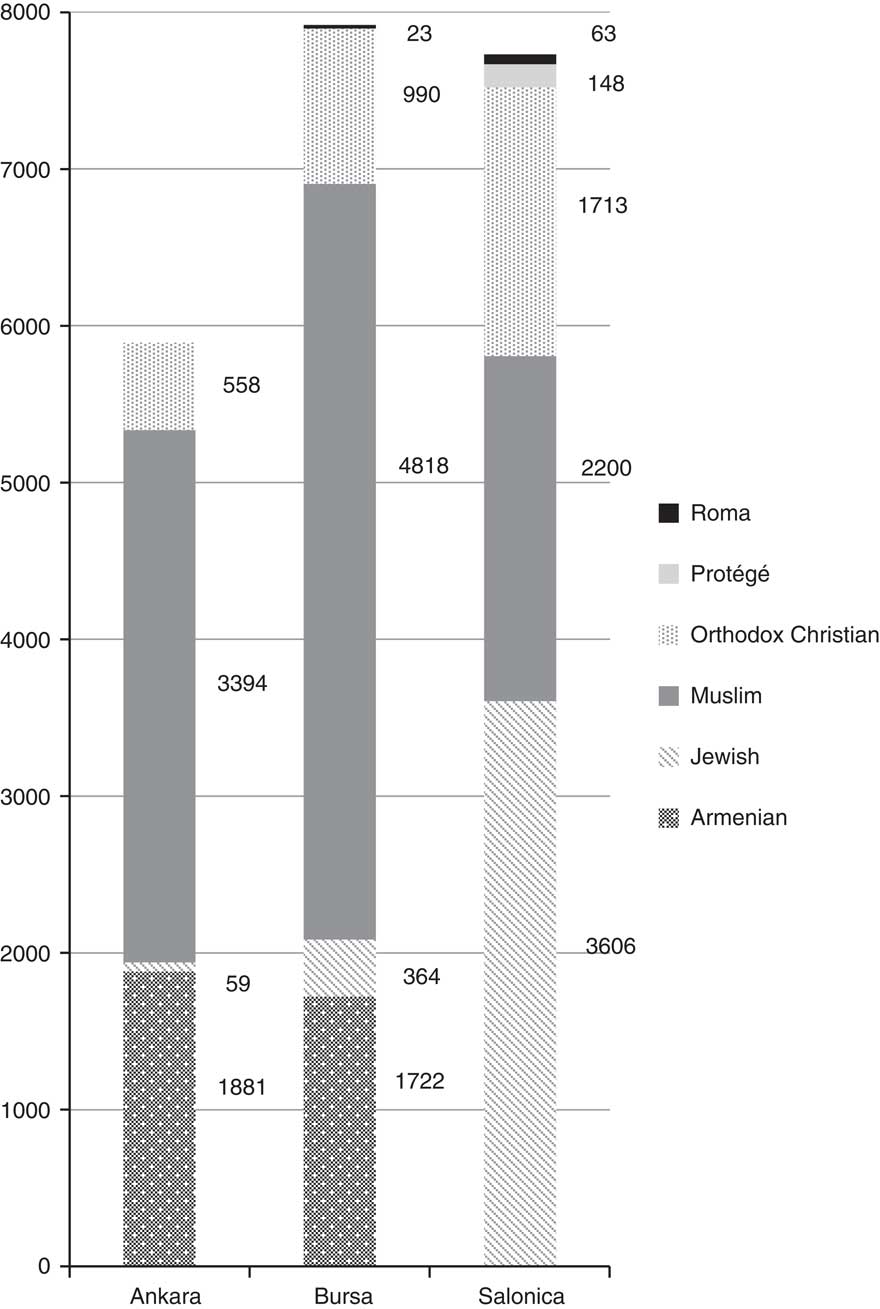

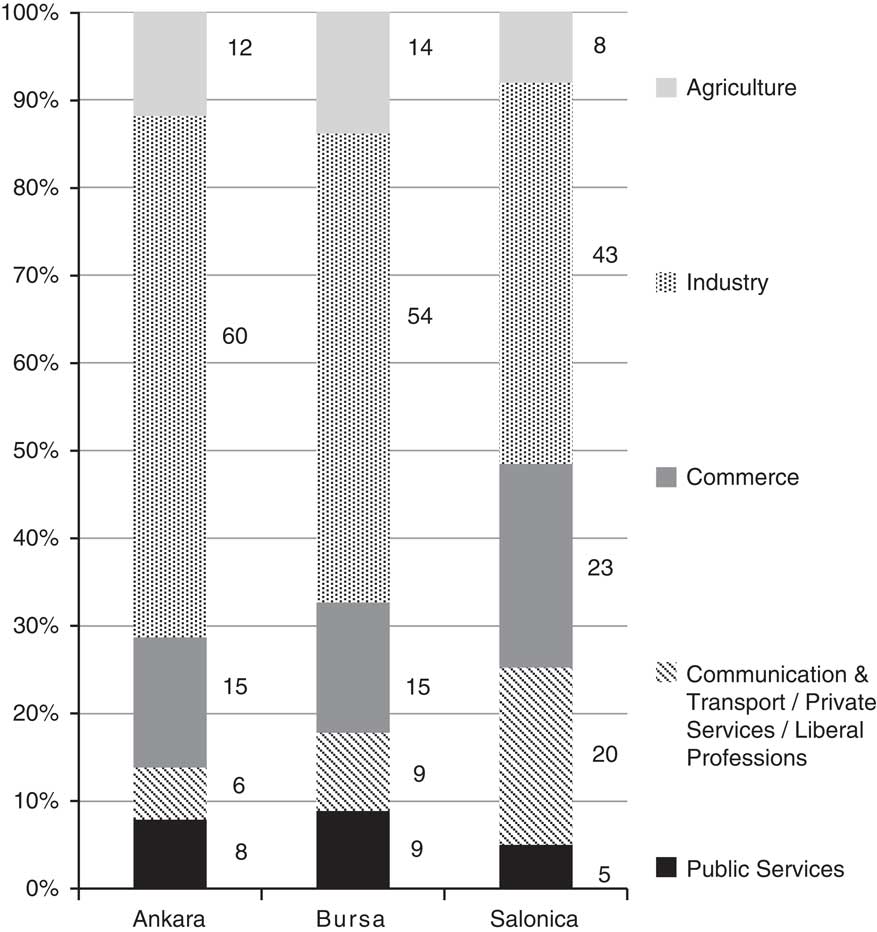

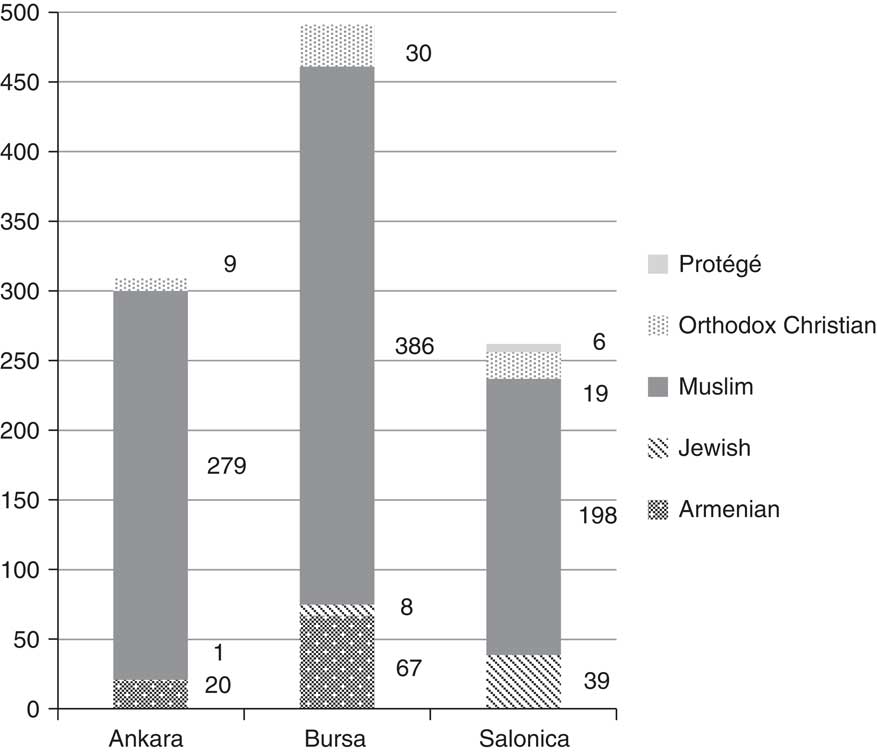

The figures below in Figure 1 were extracted from the survey. They require explanation and they should not be considered exhaustive. The total number of households was calculated from the numbers in available registers in the Ottoman state archives; therefore, the data used and categorized above might be far from being fully comprehensive. There is the double risk of incompleteness, both when the original surveys were conducted in the individual cities and then collated in Istanbul in 1845, to say nothing of the 150 years the registers were kept in the archives until they were catalogued in the 1990s. That said, the registered household numbers match mid-nineteenth century population figures for the cities. Ottoman population registers contemporaneous with the 1845 survey are structured differently. They provide figures for the number of dwellings and the total number of males of any age, including infants, living in them per neighbourhood, but they give no city total. If the neighbourhood totals are added together we reach figures similar to those obtained from the 1845 survey. Although logically, and concomitantly, units of registration differ between the 1845 tax survey and the population registers, comparing the total number of males in households (extracted from the 1845 survey) with the number of dwellings and the total number of males given in the population registers, it is clear that the 1845 tax survey covers a very large proportion of working males in the three cities.Footnote 9 The ethno-religious categories are based on the categories used by the Ottomans themselves for their survey.

Figure 1 Ethno-religious distribution, household heads, Ankara, Bursa, Salonica, 1845.

The ethno-religious categories given above also need clarification. In the Ottoman Empire of 1845 “Muslims” referred to a religious category almost irrespective of ethnicity. For the 1845 survey, all Turks, Kurds, and Arabs were counted and categorized as Muslims with no differentiation of their ethnic characteristics, and for the Ottomans only Roma was a primarily ethnic category. Ottoman Roma and Sinti alike were generally registered simply as Roma (kıptiyan in Ottoman Turkish), with no mention being made of their religious affiliations. Roma in the Ottoman Empire might have been either Muslim or non-Muslim. Figure 1 above shows that no Roma were registered in Ankara and their numbers in Bursa and Salonica were rather modest. By contrast, Orthodox Christians, or rum in the original Ottoman category, were categorized by religion. Like the Muslims, Christians, too, comprised different ethnic origins, including Greeks, Bulgarians, and other Slavic populations. Lastly, there were “Armenians”, whose category was ethno-religious, with the emphasis on ethnicity. This category included mainly Apostolic and Catholic Armenians, who belonged not to the Roman Catholic community but to the Armenian Catholic Church. In Ankara, the registers used “Catholic” as a category for Armenians belonging to the Armenian Catholic Church, but in the empire-wide taxonomy of the nineteenth century other confessions were included as “Armenians”. One specific category, the “protégés” (müstemin in Ottoman Turkish), had, until then, only been seen in Salonica. The heads of those households were mainly Orthodox Christians in possession of European passports, and in 1845 they generally belonged to the Greek clergy, although by the second half of the nineteenth century a new, wealthy group had emerged with closer ties to Western European economic centres. Although similar developments could be seen in most of the port cities of the Ottoman Empire, late-nineteenth century “protégé” status had a more significant role in Salonica. In the 1880s and the 1890s, in particular, protégés were local honorary Europeans, most of whom were wealthy Greek or Jewish merchants,Footnote 10 and the fact that no Armenian household was registered in Salonica is suspicious, although it is also known that there was never a strong Armenian community there.

As the next step for this research, the occupational titles of the household heads were coded according to the occupational classification and field of economic activity taxonomies found in the 1935 census.Footnote 11 The differences between occupations and fields of economic activity are important, albeit not clearly defined in the censuses. In fact, the categories listed below are fields of economic activity rather than occupational ones.Footnote 12 The 1935 Turkish National Census had seven broad fields of economic activity, with descriptions given in Turkish Footnote and French:

Table 2 Broad categories of fields of economic activity/occupations given in the 1935 Turkish National ‘Census’

The category D. Public Services does not correspond with my preferred category for this study of working for the state or polity, since it contains fields of economic activity that cannot be seen as public services, for example communal or religious services offered at the neighbourhood level. Moreover, some of the public utility services, such as postal services, are included in category Ç. Communication and Transport. That therefore meant a mismatch and categorical ambiguity, forcing me to create a new category of public services by using sub-categories of two broad categories: Public Services, and Communication and Transport. After these adjustments, new broad categories appear as below:

Table 3 Adjusted six broad categories of fields of economic activity.

The adjustment means that for each of the selected cities it was now possible to code the micro data of individual occupational titles of heads of households from the 1845 survey into the broad categories above. Obviously, the aim of that exercise was to filter out heads of households who were working for public utility services and to compare their respective proportions among all occupations in the three locations.

Table 4 Distributions of occupational categories, household heads, 1845.

In order to make public services as a share of urban occupations more visible, we can omit the category No or Unknown Professions and redraw the chart using percentages.

Figure 2 Distributions of occupations in five categories, household heads, Ankara, Bursa, Salonica, 1845 (%).

How can we interpret the chart below? What we should not do is use the percentages of heads of households with occupations in public service for any further detailed statistical analysis. The reason for this is, firstly, the aforementioned non-exhaustive nature of the data, and, secondly, and methodologically more importantly, that the chart is based on calculations using data that, although extracted, coded, and recoded from an 1845 Ottoman tax survey, are nevertheless arranged according to the taxonomy of the 1935 Turkish National Census. The numerical values should therefore be used only to analyse the relative importance of occupations in the public services in given locations. However, within the limitations of the model we can still see that the total numbers of occupations in the public services are close for each city, both in terms of their total number and their share of the overall occupational distribution. The same assessment applies for other broad categories of occupations of household heads. Thanks to the quality of the data, we can go further into the category of households with occupations in the public services and break the figures down according to registered ethno-religious affiliations. We can then compare this data with the general ethno-religious distribution of all the city’s households, as shown in Figure 1 above.

Figure 3 Distributions of ethno-religious affiliations of the household heads with occupations in the public service, Ankara, Bursa, Salonica, 1845.

It is no surprise to see that Muslim households are overrepresented among occupations in public services. Nor is it surprising to see Armenian, Orthodox Christian and Jewish subjects also involved in them, given what we learned earlier of the diverse and pluralistic nature of public utility services provided by the Ottomans. Nevertheless, non-Muslim households are greatly underrepresented in Ankara. Why, then, should fewer non-Muslim households have worked in public utility services in Ankara than did non-Muslims in Bursa or Salonica? After all, at 2,498 out of a total of 5,892, non-Muslim households comprised almost half of all households in Ankara in 1845. To answer the question, we need to consider spatial demarcation and try to draw dividing lines appropriate to the social and economic life of mid-nineteenth century Ottoman cities, and, specifically for this exercise, along ethno-religious lines for Ankara, Bursa, and Salonica.

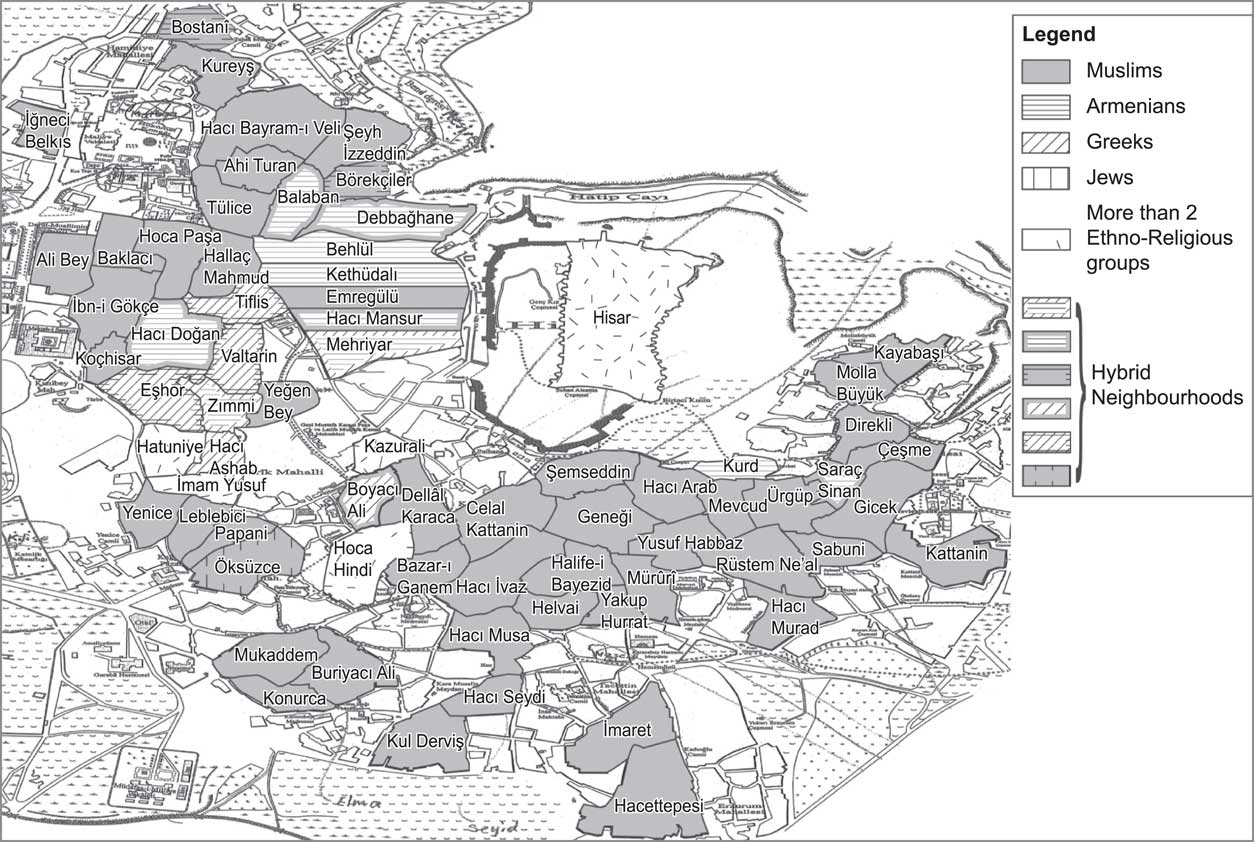

MAPPING RESIDENTIAL PATTERNS AT NEIGHBOURHOOD LEVEL ACCORDING TO ETHNO-RELIGIOUS CHARACTERISTICS

The ethno-religious composition of Ottoman neighbourhoods is a subject of ongoing and unresolved debate in the historiography. Satisfactory comprehensive data on the ethno-religious characteristics of Ottoman neighbourhoods are lacking for suitable levels of numerous cities. There are varying claims about the urban fabric and spatial organization of Ottoman cities, with views in the literature oscillating between visions of peacefully shared urban life and a belief in strict residential segregation along ethno-religious lines. One of the major assets of the temettuat registers is that the unit of record-keeping in urban settings was the neighbourhood, so the registers reveal the ethno-religious affiliations of each neighbourhood’s inhabitants. Since the registers are from 1845, and the earliest detailed modern maps and plans of Ottoman cities are also from the second half of the nineteenth and the early twentieth century, it is technically possible to map the information in the temettuat registers to show the occupational and ethno-religious composition of neighbourhoods in Ankara, Bursa, and Salonica,Footnote 14 although that was not done on those early maps. It is not an easy matter to draw exact borders for all neighbourhoods, especially not for the mid-nineteenth century Ottoman urban spaces, and since not all the neighbourhoods in the 1845 registers could be located on available maps there are blank spaces. All three of the maps are works in progress and I must emphasize that these are preliminary attempts to visualize the information at the neighbourhood level contained in the 1845 registers. So what, then, is the value of these maps for the purposes of this study?

My wish is to question the relationship between the level of ethno-religious heterogeneity and the role of religion in finding occupations in public utility services in Ottoman cities in the mid-nineteenth century. We may presume that before municipal administrations were established most public utility services were provided by ethno-religious communities. To test that presumption, I selected the three cities and compared the ethno-religious composition of their neighbourhoods. I believe that instead of comparing the proportions of the ethno-religious affiliations of registered inhabitants in neighbourhoods as alphabetical lists, showing them on a map – as far as possible – has more explanatory power for the levels and concentrations of ethno-religious heterogeneity in the cities chosen. As part of an atomistic list a neighbourhood would be separated from its place in the spatial organization of a city, which is what constitutes its urban fabric. Therefore, ethno-religious heterogeneity can be more holistically assessed and visualized on a map.

Figure 4 Ankara, 1845, ethno-religious division of neighbourhoods.

For Ankara, the earliest detailed plan on which the neighbourhoods of 1845 Ankara can be detected is that by Carl Christoph Lörcher from 1924.Footnote 15 We used the Lörcher plan as the template to position the neighbourhoods of the 1845 Ankara temettuat registers. In doing so, we were able to locate sixty-nine out of ninety neighbourhoods on this map.Footnote 16

Figure 5 Bursa, 1845, ethno-religious division of neighbourhoods.

The earliest detailed cadastral plan of Bursa is from 1855, and there is also a detailed insurance map of the city from the 1880s that shows neighbourhoods. Using these two maps we were able to locate 129 neighbourhoods out of 142 listed in the temettuat registers for Bursa.Footnote 17

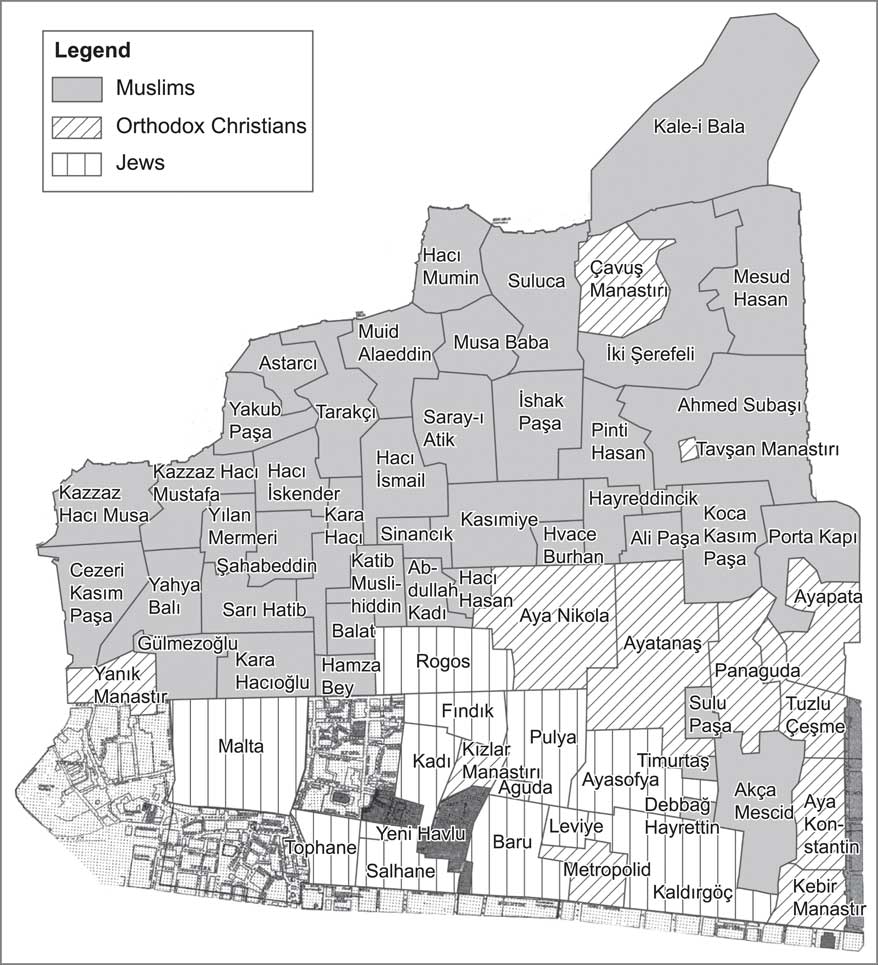

Figure 6 Salonica, 1845, ethno-religious division of neighbourhoods.

Lastly, the picture of Salonica’s neighbourhoods in 1845 is based on a map by Vassilis Dimitriadis.Footnote 18 In the preparation of our map we were supported by Dilek Akyalçın Kaya,Footnote 19 and we were able to locate all sixty-eight neighbourhoods in the temettuat registers.

Comparing the residential patterns of the neighbourhoods in the three cities, it is remarkable to see that Salonica’s spatial organization came close to amounting to an ethno-religious segregation of its urban life. In fact, we see a strictly divided city, with not a single mixed neighbourhood. There are only five Orthodox Christian residential units in Muslim or Jewish parts of the city: Çavuş Manastırı, Tavşan Manastırı, Yanık Manastır, Kızlar Manastırı, and Metropolid, all of which were either monasteries with few inhabitants or the Metropolitan residential unit. There were only four Muslim neighbourhoods on the border between the Jewish and Orthodox Christian parts of the city.

Among the three cities selected Bursa lies in the middle as far as ethno-religious segregation is concerned. There are mixed neighbourhoods there, but only one Jewish quarter and no neighbourhood of mixed Orthodox Christians and Armenians. Apart from a single Armenian neighbourhood in the north-west, all the Armenian neighbourhoods are in the south-east of the city. We should not forget that thirteen of Bursa’s neighbourhoods could not be located on the map, but none of them had mixed Armenian and Orthodox Christian inhabitants, and no Jewish household was registered there. As a result, Bursa was still deeply segregated along ethno-religious lines, albeit to a lesser degree than in Salonica.

Ankara’s pattern of neighbourhoods shows the least ethno-religious segregation. There were mixed neighbourhoods shared by Muslims, Armenians, and Orthodox Christians, and the citadel, hisar, along with three other neighbourhoods had more than two ethno-religious groups. There was no homogenous Jewish quarter. Twenty-one neighbourhoods could not be located on the map of Ankara, but sixty-nine of them are present and those missing would not decrease the overall diversity of the ethno-religious groups in all the neighbourhoods. There is even potential for more diversity to be revealed because the largest neighbourhood not yet mapped, Bölücek-i Atik, was another mixed neighbourhood.

Comparison of the residential patterns and the ethno-religious characteristics of public utility sector occupations suggests a correlation between the level of residential segregation and the proportion of non-Muslims in the public utility sector in the city. For example, in Salonica, where we have the most segregated urban fabric, we see the largest proportion (64 out of 262) of non-Muslims with occupations in public services compared with Ankara and Bursa. Again, not surprisingly, Salonica had the highest number of Jewish households with occupations in public services. In a similar vein, the high concentration of Armenians in Bursa is also reflected in the large proportion of Armenian households with occupations in the public sector (67 out of 386). My own interpretation of the situation is twofold. First, before the emergence of central urban municipal organizations,Footnote 20 public services were organized and provided at the communal level, in the neighbourhoods. Secondly, in mixed neighbourhoods, with Muslim and non-Muslim inhabitants, non-Muslims had proportionately fewer occupations in the public utility sector. That claim must, of course, be tested for other locations in the mid-nineteenth century Ottoman Empire, especially from the perspective of the administrative autonomy of communities. Nonetheless, I am confident that given the Islamic ideological base of the Ottoman Empire it is fair to say that in urban locations where their communities were neither building a majority, nor strongly represented, the relative share of public utility service work done by non-Muslims would have been smaller than that done by Muslims.

In the second part of this study the role of the 1923 population exchange and its repercussions on the ethno-religious homogenization and occupational structure will be assessed.

WORKING FOR THE STATE IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY GREECE AND TURKEY

The compulsory exchange of population between Greece and Turkey in 1923 had devastating effects on the urban populations in both countries, for each of which it can be seen as the last and most decisive instance of forced deportations and ethno-religious homogenization. The tables below show the end results of the respective Hellenization and Turkification of the urban populace of the selected cities.

Table 5 Religious affiliations of city population in Athens and Salonica, 1928.

Source: Résultats Statistiques du Recensement de la Population de la Grèce du 15–16 Mai 1928. IV. Lieu de Naissance – Religion et Langue – Sujétion (Athens, 1937).

The demographic impact was greater on the Greek side and was felt mainly in Athens and Salonica. Between 1920 and 1928, the population of Athens soared from 293,000 to 453,000, a fifty-four per cent increase; and Salonica’s rose from 170,000 to 251,000, a thirty-nine per cent increase in only eight years.Footnote 21 That increase was mainly the result of the arrival of Orthodox Christian immigrants deported from Turkey. In the immediate aftermath of the population exchange, the general demographic outcome for Greece was the loss of non-Orthodox-Christian elements of the population, though with the exception of the Jews of Salonica.Footnote 22 Meanwhile, in Turkey, a similarly radical religious homogenization took place, caused both by the extermination of the Armenian population and by the population exchange.

Table 6 Religious affiliations of city population in Ankara and Bursa, 1927, 1935, 1945.

Sources: Turkish national censuses.

As can be seen in the above table, by 1927 the male populations of Ankara and Bursa were ninety-five and ninety-seven per cent Muslim, respectively. Both those cities grew rapidly between 1927 and 1945, but percentages of non-Muslim males fell even further as male Muslim populations rose to ninety-eight per cent in Ankara and ninety-nine per cent in Bursa. Such extremely radical demographic shifts were purposely planned and executed as the policies of relatively late, brutal, and militaristic nation-state builders. The newly created Turkish and post-Greco-Turkish-War Greek national states each carved out their nations by implementing drastic social engineering projects, defined along religious lines, rather than the more blurred ethnic ones. As an influential author succinctly commented on the 1923 Greek-Turkish population exchange: “A Western observer, accustomed to a different system of social and national classification, might even conclude that this was no repatriation at all, but two deportations into exile – of Christian Turks to Greece, and of Muslim Greeks to Turkey.”Footnote 23

There is limited literatureFootnote 24 on the impact of the population exchange on the Greek and Turkish economies, and, although no detailed analysis of the effects of the exchange on the occupational structure has yet been conducted, what follows is not an attempt to do that. Instead, I have compared occupational structures, with the focus on public services in Ankara, Bursa, and Salonica – as well as in Athens, but only for the joint census year 1927/1928. In what follows, I will attempt to bring a gendered perspective into the comparison and to assess the role gender played in Greece and in Turkey in finding employment in the public sector in the cities selected in 1927/1928.Footnote 25

In order to do this, a last two-stage data conversion was necessary. As mentioned before, the 1935 Turkish census utilized categories of fields of economic activity very similar to the ones in the Greek census of 1928. Therefore, I first converted the 1928 Greek economic categories into the 1935 Turkish ones and then the 1927 Turkish economic activity codes into the 1935 Turkish codes, so that they would be in accordance with the coding scheme of the data extracted from the 1845 tax survey. The result of that comparison is shown below for males and females. One important caveat is necessary before commenting on the results of this comparison. The occupational data extracted from the Turkish 1927 census encompass the entire urban population of Ankara and Bursa irrespective of age and therefore include infants and the elderly, who were not expected to work. Those groups are registered and then coded into the category “No or Unknown Profession”. The occupational data from the 1928 Greek census, on the other hand, excludes anyone younger than ten years old.Footnote 26 Therefore, the total number of observations varies from the general census used in the preparation of Table 5 above, which gives the total population of Athens as 459,211 and that of Salonica as 244,680. The occupational data from the 1928 Greek census provide information on 387,534 individuals for Athens and on 195,855 for Salonica.

Table 7 Sectoral breakdowns of female occupations, Ankara, Bursa (1927, 1935, 1945), Salonica, Athens (1928).

Table 8 Sectoral breakdowns of male occupations, Ankara, Bursa (1927), Athens, Salonica (1928).

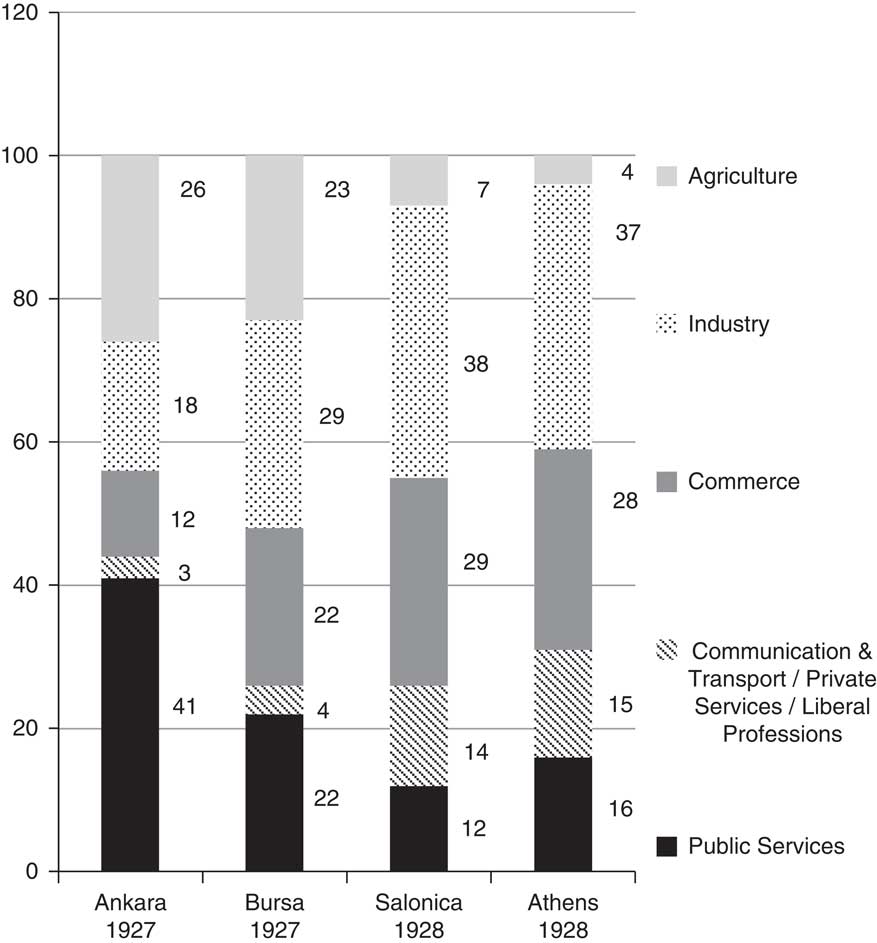

The population exchange and the preceding wars had profound demographic and economic effects. The proportion of the population without an occupation was highest in Athens, at more than twenty-five per cent (57,081 males over ten years old without an occupation out of 193,451 registered males, see Table 8). Salonica had fewer unemployed males but their number was proportionately higher than those in Ankara and Bursa, despite the fact that the Turkish data actually include males under ten years old. Employment in public services could not provide enough jobs to absorb the high level of urban unemployment in either Athens or Salonica. The relative share of occupations in public services is the second lowest, after occupations in agriculture. The figure below compare the number of male inhabitants who had occupations and the distribution of males across occupational categories in percentages.

Figure 7 Distribution of occupational categories, males with occupations, Ankara, Bursa, Salonica, Athens, 1927/1928 (in %).

It is clear from the above chart that the Turkish state apparatus provided employment opportunities both in civil and military sectors to the male inhabitants of its capital city; that was not the case in Athens. Yet, the figures should be seen in relation to the proportion of urban unemployed actually registered in the censuses as having occupations. Indeed, it is at exactly this point that the census data and occupational data extracted from them should be handled with extra care. Not only are the ambiguities in the taxonomy, such as professions, occupations, or fields of economic activity, problematic, people who had an occupation may be used only as a proxy for what their employment actually was. For instance, some residents, registered with certain occupations on the day of the census, might have been unemployed for the rest of the census year, or might have worked in different sectors. The numbers presented above are therefore not suitable for further quantitative analysis. That said, I believe the potential of occupational data extracted from the censuses is still untapped, especially for comparative studies.

Another major advantage of occupational data from the modern national censuses is their units of registration. Since, to a great extent, in twentieth-century censuses households were replaced as the unit of registration by individual citizens, they can be used to avoid a historical and categorical undercount of women and sometimes the direct gender-blind processes of registration practised by earlier surveys. One should be extremely cautious about the gendered technicalities and dynamics of varying methods of census-taking in different locations; even so, the quality of data (and their very presence) on female employment from the national census speaks for itself in comparison with the non-existence of any such data in the 1845 tax survey, which, as we know, registered almost exclusively male members of households. Women were only registered in a negligible number of cases where no male members lived in a household. As a result, very few women appear in the census data, and for most of them no occupation was recorded.

Table 7 shows a severely low degree of participation by females in the labour markets in all the locations selected. The very small number of females with occupations registered in Ankara and Bursa demands explanation; in Ankara in 1927 there were only 180 women with occupations in public service out of a total of 25,205, and the exact breakdown of their occupations is shown. Even the total number of women who had any occupation in any sector was fewer than five per cent in both Ankara and Bursa. I can only conclude that females in Ankara and Bursa were registered as having no or unknown occupations and that their share in the household division of labour went unrecorded.

The situation in Athens and Salonica was different. In Salonica, approximately 100,000 females over the age of ten were registered, around fourteen per cent of them with occupations, while in Athens close to 200,000 females over ten years were registered, eighteen per cent with occupations. Most of those occupations were in industry, followed by the generic category of “Communication & Transport/Private Services/Liberal Professions”. Although smaller than the first two sectors, public services nevertheless offered occupations to thousands of women living in Athens and Salonica in 1928.

The extremely small number of females with occupations reported in Ankara and Bursa cannot be explained by the political and economic weakness of the newly established Turkish state in the 1920s, for its policy was at least intended to increase the inclusion of girls in education and to facilitate female participation in the workforce. However, a look at the occupational information extracted from the later censuses shows that the situation did not change very considerably. Even during the interwar period and immediately after World War II only about ten per cent of the women of Ankara were recorded as having occupations, and in Bursa there were even fewer opportunities for women to be employed. In the same cross sections, the total number of women with occupations fell from 3,744 of 36,873 in 1935 to 3,436 of 42,992 in 1945.

The extremely small proportion of women with occupations in Ankara and Bursa gains another dimension from comparison with the figures for Athens and Salonica. The comparison hints at cultural explanations and poses questions about the division of labour within Muslim and non-Muslim households. The figures above should be considered in light of the radical Turkification and Islamification of city dwellers in Ankara and Bursa and the simultaneous Hellenization going on in Athens and Salonica. Even so, the role of religion should be examined in more depth before any premature conclusions are reached. One judicious remark to be made here would be to highlight the importance of the joint effects of gender and religion in Turkified and Islamicized Ankara and Bursa, which, in their interaction, superimposed a double barrier to entry for women’s employment in Turkish cities compared with Greek cities.

conclusion

In this study, the occupational structures of Ankara, Bursa, and Salonica have been examined through two cross sections, taken from the mid-nineteenth century, when the cities were major urban centres of the Ottoman Empire, and from the late 1920s, when the same cities were re-inventing themselves as economic and political centres of the new nation states of Greece and Turkey, neighbours interconnected in their making and remaking owing to the population exchange of 1923. The results of these two examinations have highlighted the importance of religion to the organization of public utility services at the neighbourhood level in mid-nineteenth century Ottoman cities, and how the same religion limited female employment in Turkish cities in the late 1920s.

For the Ottoman Empire, ethno-religious population groups and the communities they built were crucial to its functioning as a multi-religious and multi-ethnic polity. The effect of religion on both bringing people together and keeping them apart in neighbourhoods with reference to patterns of residential building and as a determinant of occupational choice is an under-researched topic. I would argue that mapping occupational structures onto residential patterns according to ethnicity and religion can reveal aspects of the spatial organization of urban economic and social life in the late Ottoman Empire. I believe that for non-Muslim Ottoman city dwellers, finding employment in the public utility sector was positively correlated with ethno-religious segregation at neighbourhood level in Ankara, Bursa, and Salonica in 1845. It was especially true in neighbourhoods where non-Muslims lived, where everyone belonged to ethno-religious groups, such as the Jewish community in Salonica. On the other hand, mixed neighbourhoods in Ankara resulted in overrepresentation of Muslims in public service sector employment, which suggests that although the Ottoman Empire was a multi-ethnic and multi-religious polity Muslims had leverage in organizing and finding employment in public services at neighbourhood level. This point should be further analysed by examining the components of the public services provided in neighbourhoods and assessing the importance of religion.

The second finding of the study is related to religion and gender. It argues that in the Turkey of the late 1920s adherence – or not – to the Muslim faith affected women’s occupational choices and employment opportunities. Both Greece and Turkey, as successors to the Ottoman Empire, imagined and constructed their nationhood along religious lines, and implemented social-engineering projects to create, respectively, Orthodox Christian and Muslim nations. After 1923, the populations of Ankara, Bursa, and Athens were religiously homogenized, while Salonica, once the metropolis of Mediterranean Jewry under Ottoman rule, with Jews constituting more than half its population, transformed itself into a Greek city with a sizeable Jewish community of around a fifth of its population in 1928. Non-Muslims had disappeared from both Ankara and Bursa by 1928 and hardly any female members of Muslim households were registered as having occupations. Non-Muslim females living in Athens and Salonica, on the other hand, had higher levels of employment, including in the public sector. This finding should also be further developed and the question asked whether Jewish women had equal opportunities for employment, especially in the public sector. In a similar vein, the time span of this examination should be extended to the period after World War II to allow an evaluation of how the loss of Salonica’s Jewish population affected the general occupational structure there.

This article has compared the occupational structures of Ankara, Bursa, and Salonica as they were in the mid-nineteenth century and then again in the first half of the twentieth century. The focus was not on shifts in labour relations, but rather on changes in urban occupational structures. Even so, by focusing on the sub-sectoral group of occupations providing public utility services we have been able to trace the changing dynamics of working for a polity in those cities between the 1840s and the 1920s. I have deliberately used the term “polity”, rather than “state”, because of the wider-ranging and more inclusive nature of the political structures that organized the public utility services for Ankara, Bursa, and Salonica in the mid-nineteenth century. In the 1840s, before the advent of the municipal administrations, several public utility services, including religious, safety, communal, and educational services, were organized and provided in Ottoman urban localities by communities at both town and neighbourhood level. In the second cross section, taken from the 1920s, the three cities had, by then, become important urban centres in two nation states: a consolidating and re-forming Greece and an emerging Turkey. Public utility services were more centrally organized under the new polities and were handed to a newly growing but central occupational category and labour relation, namely public services and public servants. A greater proportion of people in the three cities were employed by the central national state than had been the case in the mid-nineteenth century. In those three towns, the representative bodies of the Ottoman central state changed from provincial administrations with fewer responsibilities for providing public utility services in the 1840s to more centrally organized administrative and municipal structures that acted almost monopolistically as employers of public servants, providing most of the public services in the fields of safety, education, sanitation, and religion.

The political change brought about by the fall of the Ottoman Empire was a drastic one, for it not only dissolved an imperial polity and led to the emergence of, among others, Greek and Turkish nation states, it also led them in their early existence briefly but decisively to war. The Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922 resulted in a compulsory exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey. This transformed the ethno-religious composition on both sides of the Aegean, creating a framework of interaction for the people of both states that affected a number of aspects of social and economic life, including labour relations.