The past 30 years have witnessed the law on consent move progressively towards a patient-focused approach. This shift, from paternalism to informed consent, is well documented by Rix (Reference Rix2017). The UK Supreme Court Montgomery ruling (Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board (Scotland) [2015]) consolidates this move, making what matters or is important from the perspective of the patient (i.e. patient's values) central to consent. Montgomery, however, also incorporates other value perspectives, including those of the clinician. The ruling thus makes shared decision-making between clinician and patient the basis of consent in clinical care.

In this article we: (a) describe the elements of consent as set out in Montgomery and how these reflect current General Medical Council (GMC) and related guidance on shared decision-making; (b) outline the skills and other elements of values-based practice that, together with evidence-based practice, support shared decision-making in clinical care; and (c) give examples of how Montgomery and values-based practice together support shared decision-making in psychiatry.

The Montgomery ruling

The facts of the case in Montgomery are readily stated (see Rix Reference Rix2017). Mrs Nadine Montgomery, who had diabetes, gave birth by vaginal delivery to a baby while under the care of an obstetrician, Dr McLellan. Sadly, her baby suffered severe birth trauma as a result of shoulder dystocia. This is a well-recognised complication of vaginal delivery in women with diabetes. Dr McLellan had, however, not warned Mrs Montgomery of this risk nor offered her the option of an elective caesarean section. Mrs Montgomery consequently sought damages in negligence. Two lower courts found against her, citing the Bolam principle (Box 1). The Supreme Court reversed this decision, allowing her appeal in their judgment delivered in March 2015.

BOX 1 Bolam and Montgomery

The Bolam principle is a rule for assessing the legal standard of care in negligence cases involving professionals. It says that a doctor (or other skilled professional) will not be held negligent so long as they act in accordance with the practice of a responsible and skilled body of their professional peers (Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee [1957]). Bolam was applied in Sidaway v Board of Governors of the Bethlem Royal Hospital and the Maudsley Hospital [1985] as the standard of care in relation to a doctor's duty to inform in medical treatment cases. Montgomery overturned Sidaway but left Bolam otherwise intact. This means that the Bolam test continues as the test for the appropriate standard of care in negligence for technical aspects of diagnosis and treatment. But the duty to inform now requires shared decision-making based on Montgomery.

The Montgomery case has sparked a good deal of controversy, with legal experts calling into question ‘the competence of the courts to adjudicate on matters of clinical judgement’ (Montgomery Reference Montgomery and Montgomery2016). Nonetheless, it remains true that the law requires what amounts to values-based shared decision-making as the basis of consent, so that the values of all concerned should be heard and a true dialogue form the basis of consent.

Four elements of the Montgomery model of consent

Some commentaries have tended to focus on what Montgomery has to say about risk disclosure. This is important, but is only one of four key elements of its model of consent. We shall look briefly at each of these as summarised in Box 2 and then indicate how they come together in shared decision-making.

BOX 2 Four elements of the Montgomery model of consent

-

1 Disclosure of material risks

-

2 Disclosure of benefits as well as risks

-

3 Disclosure of risks and benefits not just for the intervention being considered but for any reasonable alternatives that may be available

-

4 Disclosure by way specifically of dialogue between the clinician and patient

Consent in Montgomery starts with disclosure of ‘material risks’. Under Bolam rules, what is material is a matter primarily for professional judgement. This is why two lower courts rejected Mrs Montgomery's claim for damages. In deciding against warning her patient about shoulder dystocia Dr McClelland, they concluded, had acted consistently with the practice of a body of her peers. The Montgomery judges, however, took a very different line. Contemporary standards of practice, they argued (as represented in particular by GMC guidance such as Good Medical Practice (General Medical Council 2013)), demand an approach that defines the materiality of a risk from the perspective primarily not of the clinician but of the patient. They summarised their patient-focused test of materiality thus:

‘The test of materiality is whether, in the circumstances of the particular case, a reasonable person in the patient's position would be likely to attach significance to the risk, or the doctor is or should reasonably be aware that the particular patient would be likely to attach significance to it’ (Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board (Scotland) [2015]: para. 87).

This is an important passage. But there is more to consent in Montgomery than just risk disclosure so defined. ‘It follows from this approach’, the Montgomery judges continue, that the materiality of a risk:

‘is likely to reflect a variety of factors […] for example […] the importance to the patient of the benefits sought to be achieved by the treatment, the alternatives available, and the risks involved in those alternatives’ (para. 89, our italics).

This in turn means, they continue in the next paragraph, that the doctor's role:

‘involves dialogue, the aim of which is to ensure that the patient understands the seriousness of her condition, and the anticipated benefits and risks of the proposed treatment and any reasonable alternatives, so that she is then in a position to make an informed decision’ (para. 90, our italics).

The model of consent thus defined is not a legal invention. The Montgomery judges based it on submissions by the GMC. They cite, in particular, GMC guidance on shared decision-making as the basis of consent (General Medical Council 2008, para 5):

‘“The doctor explains the options to the patient, setting out the potential benefits, risks, burdens and side effects of each option, including the option to have no treatment. […] The patient weighs up the potential benefits, risks and burdens of the various options as well as any non-clinical issues that are relevant to them. The patient decides whether to accept any of the options and, if so, which one.”’ (cited in Montgomery at para. 78.)

Read in isolation this passage might suggest a consumerist model of consent in which (like a customer in the retail trade) ‘the patient is always right’. Montgomery, though again reflecting professional guidance, makes clear that this is not what is intended. The patient's values (i.e. what matters or is important to the patient) are indeed at the heart of clinical decision-making in Montgomery. But in coming to a shared decision, the patient's values have to be weighed in the balance with a number of other values, including those of the clinician.

The importance of clinicians' values in Montgomery is signalled first in a number of exceptions to the duty to disclose material risks. These are summarised in Box 3. Two of these exceptions (‘risk of harm’ and ‘necessity’) directly reflect the long established ‘primum non nocere’ (first do no harm) principle of medical ethics.

BOX 3 Three exceptions to the duty to disclose risks

Montgomery follows precedent in recognising three exceptions to the duty to disclose:

-

1 Opting out: the patient does not wish to know about risks (but, even then, the GMC says that doctors should try to give basic information and must explain the potential consequences of not having the relevant information) (General Medical Council 2008: paras 13–15).

-

2 Risk of harm: there is a risk of serious harm should the patient be informed. But the GMC adds: ‘“serious harm” means more than that the patient might become upset or decide to refuse treatment’ (General Medical Council 2008: para. 16); and Montgomery warns that the ‘therapeutic exception’ should be exceptional.

-

3 Necessity: in an emergency, the doctrine of necessity applies, for example if the patient is ‘unconscious or otherwise unable to make a decision’ (Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board (Scotland) [2015]: para. 88).

Montgomery further reflects medical values in restricting the options that the doctor is obliged to consider to those that are ‘reasonable’ (para. 87). Options that are ‘futile or inappropriate’ (para. 115) are thereby excluded. Just who decides what is futile or inappropriate is left unstated. But there is a clear commitment to the medical value of scientific evidence in the Montgomery judges' appeal to evidence-based guidelines from the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (para. 112) and from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (para. 116). Still other balancing elements implicit in Montgomery include the values of other team members (para. 75) and of the wider society as represented by health economic and other strategic values (para. 75) bearing on the effective and equitable delivery of healthcare.

The shared decision-making therefore underpinning consent in Montgomery depends on balancing what is important to the patient concerned as the primary value driving clinical decision-making against the values of the clinician and others. The patient, as the Montgomery judges put it, is entitled to have their values ‘take[n] into account’ (para. 115). Taken into account, then, weighed in the balance, no more. But also no less – it was precisely because Mrs Montgomery's values were not taken into account that the Montgomery judges overturned the findings of two lower courts and allowed her appeal. So there is a balance to be struck. This is where values-based practice has a role to play.

Values-based practice

Values-based practice is one of a number of approaches (including ethics and health economics) developed in recent years to support working with values in healthcare. Values-based practice adds to these a skills-based approach to balanced decision-making within frameworks of shared values.

Like evidence-based practice, values-based practice recognises that:

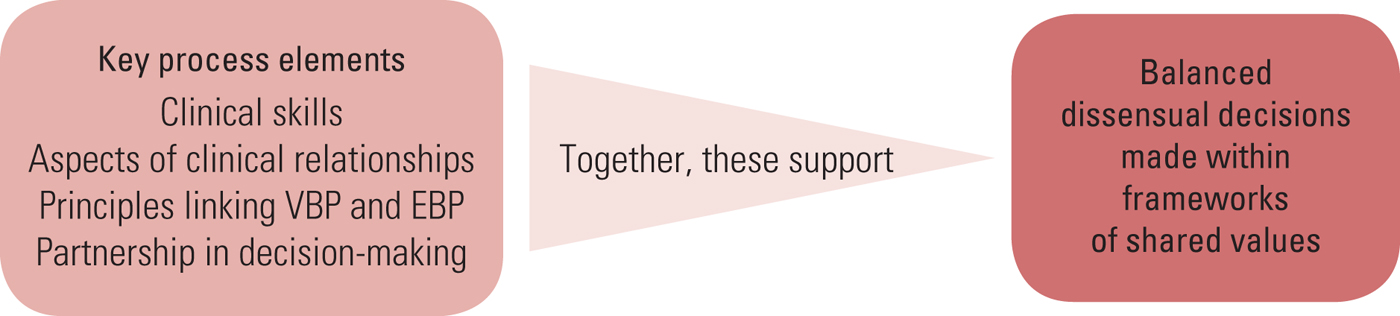

Values-based practice is thus a partner to evidence-based practice (Fulford Reference Fulford2011). Evidence-based practice offers a process that balances complex and conflicting evidence as it bears on clinical decision-making. Values-based practice offers a counterpart balancing process for values. The process of values-based practice is shown diagrammatically in Fig. 1.

FIG 1 The process of values-based practice (VBP). EBP, evidence-based practice.

With its aim of balanced decision-making, values-based practice supports the balanced decision-making required by Montgomery. Note in Fig. 1 that the decisions may be dissensual because it will not always be possible to reach a consensus, yet conflicting values remain relevant: ‘differences of values, instead of being resolved, remain in play to be balanced according to the circumstances presented by particular decisions’ (Fulford Reference Fulford, Peile and Carroll2012: p. 32). For further discussion of ‘dissensus’ see Fulford (Reference Fulford, Peile and Carroll2012: pp. 165–182). Dissensus, then, does not preclude the possibility of consensus about shared values, but allows the possibility of a balanced approach to working together even where values are in conflict (Fulford Reference Fulford, ten Have and Sass1998). Box 4 sets out the process elements of values-based practice mentioned in Fig. 1. They are further described in Fulford (Reference Fulford and Radden2004, Reference Fulford, Peile and Carroll2012).

BOX 4 The ten process elements of values-based practice

Clinical skills

-

1 Awareness of values

-

2 Reasoning about values

-

3 Knowledge of values

-

4 Communication skills

Professional relationships

-

5 Person-centred practice

-

6 Multidisciplinary team work

Evidence-based practice and values-based practice

-

7 The two feet principle: all decisions are based on both values and evidence

-

8 The squeaky wheel principle: values are only noticed when they cause problems

-

9 The science-driven principle: as science and technology advance new and diverse values emerge driving the need for attention to the evidence and the facts

Partnership

-

10 Consensus and dissensus

In the rest of this section we illustrate how values-based practice supports shared decision-making with a worked example of a training exercise used to develop one of its four skills areas, raised awareness of individual values.

If you want to learn more about values-based practice a comprehensive reading guide including self-training and other resources is available at http://valuesbasedpractice.org.

A worked example

Raised awareness is the starting point for all values-based training (Woodbridge Reference Woodbridge and Fulford2004). Our natural tendency is to assume that we understand each other's values. But all too often we are wrong. So it is important clinically to find out what is important to our patients. Otherwise we will not be in a position to ‘take into account’ our patients' values in the process of shared decision-making required by Montgomery.

The exercise shown in Box 5 is a forced-choice exercise. You may want to try this before reading on. Like other skills-based areas of medicine, values-based practice is better understood by trying it for yourself rather than just reading about it.

BOX 5 Forced-choice exercise

Imagine you have developed early symptoms of a potentially fatal disease.

There are two possible evidence-based treatments, both of which offer advantages but neither of which is perfect:

-

• Treatment A – gives you a guaranteed period of remission but no cure

-

• Treatment B – gives you a 50:50 chance of ‘kill or cure’

It's your decision – what is the minimum period of remission you would want from Treatment A to persuade you to choose that treatment rather than the 50:50 ‘kill or cure’ option offered by Treatment B?

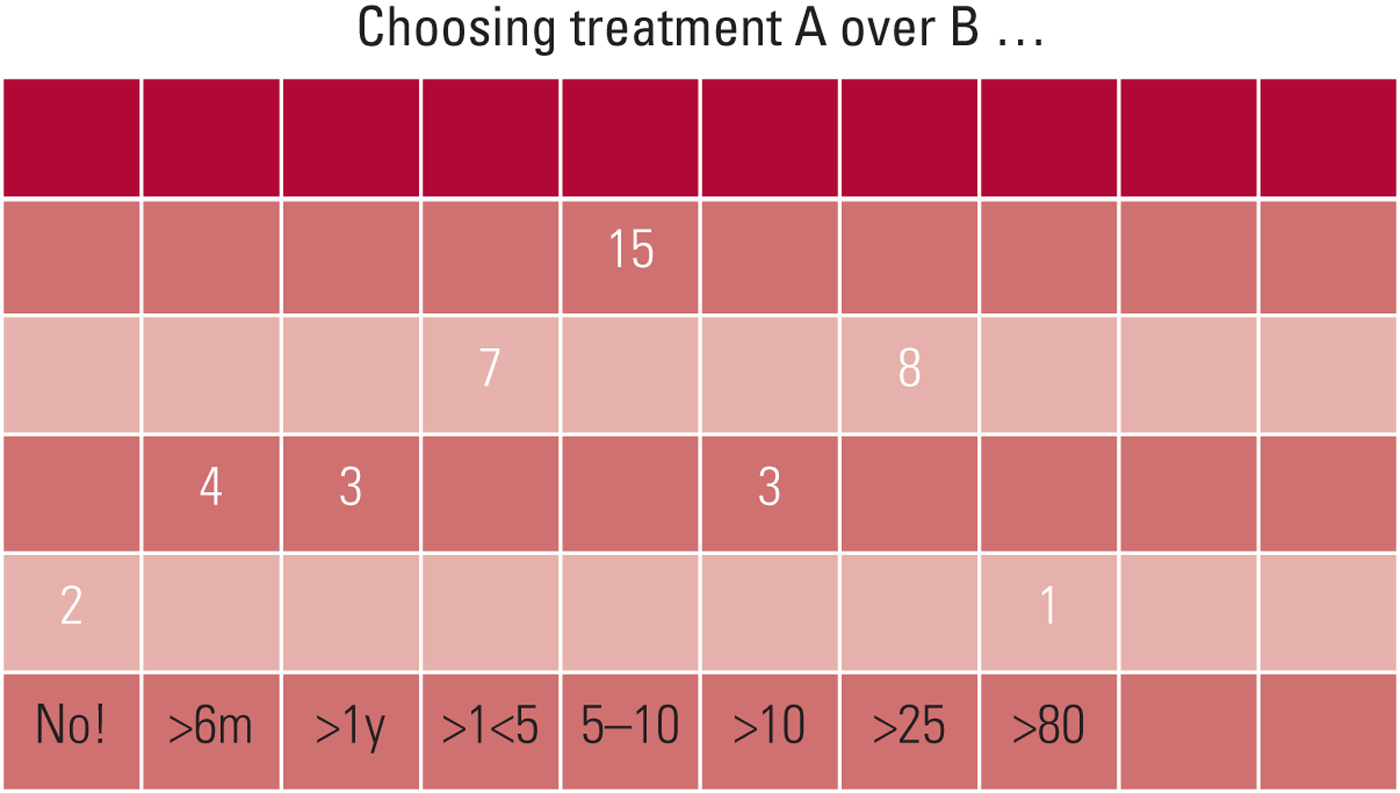

Mostly people don't find it easy! This is part of the message. But the main message is in the extraordinary range of answers people give. The range shown in Fig. 2 is from a seminar with a group of clinicians, but it is typical. Just 41 people's answers range from under 6 months to over 80 years. In training sessions, people are often really surprised by the answers that other group members – even people who know each other well (Handa Reference Handa, Fulford-Smith and Barber2016) – come up with. If you tried the exercise, where did your answer come? Think about why you chose the period you did and why others choose very different periods.

FIG 2 Results when the forced-choice exercise described in Box 1 was completed by a group of 43 clinicians.

In plenary discussion, the group quickly came to see that their wide range of answers reflects a correspondingly wide range of their individual values. For some people what was important was to complete a key project (a PhD, for example): so their minimum period was quite short (under 6 months in this case). For people with young families, on the other hand, their priority was to last long enough to see their children safely grown up: so they needed a minimum of 10 or more years. Still other people opted for the 50:50 ‘kill or cure’ option regardless. Two people in this group said they would ‘want it over with’ rather than facing a definite date of death, however far away.

The messages then are that, yes, our individual values really are very different one from another, and no, we can't assume we know what matters even to people we know well (let alone, therefore, the patient we met for the first time a few minutes ago). All this in turn plays out in clinical decision-making. In this forced-choice exercise everyone has the same evidence base. They have indeed an artificially simple evidence base. Usually the evidence is more complex and ambiguous than in the imaginary scenario in the exercise. Also, equivalent choices made for real are that much more challenging for being emotively charged. Yet this is what is demanded of patients in the shared clinical decision-making required by Montgomery.

Raising awareness, as we have indicated, is only the start. But it is a useful start clinically. In the next section we look at how values-based practice, in raising awareness of differences of individual values, supports shared decision-making in psychiatry. We consider two examples, recovery practice and compulsory treatment, representing contrasting balances of values.

Shared decision-making in psychiatry

Psychiatry shares with the rest of medicine the principles of shared values-based decision-making underpinning consent mandated by Montgomery. Good Psychiatric Practice (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2009) mirrors in this respect the GMC guidance on which the Montgomery judges relied (for details see Rix Reference Rix2017). The College's Code of Ethics (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2014), similarly, directly reflects the elements of the Montgomery approach to consent: it emphasises the importance of ‘partnership’ in decision-making (Principle 5.1) based on the ‘sharing of […] understandable information’ (Principle 5.3) about ‘the full range of available treatment options [and] the advantages and disadvantages of each’ (Principle 6.1).

But there is a marked gap between theory and practice:

‘the accounts of people using mental health services, along with observations and surveys of psychiatric practice, all suggest that [shared decision-making] is not fully implemented, with psychiatrists often using persuasion to improve adherence’ (Baker Reference Baker, Fee and Bovingdon2013).

There is a similar gap between theory and practice in decisions about ‘place of residence’ for people with dementia admitted to medical wards (Emmett Reference Emmett, Poole and Bond2013) and, in part, this directly reflects the varied values that can be at play in such decision-making (Greener Reference Greener, Poole and Emmett2012).

One reason for these gaps is that psychiatry raises particularly acute challenges of balancing values (Fulford Reference Fulford1989). This is why the need for values-based practice has been recognised, for example, in forensic psychiatry (Adshead Reference Adshead2009). But that the challenges are generic is illustrated by the role of shared decision-making in recovery practice.

Recovery practice

The importance of values in recovery practice in psychiatry has been widely recognised for some time (Anthony Reference Anthony1993; Baker Reference Baker, Fee and Bovingdon2013). ‘Recovery’ in this context means shifting the focus of treatment from the professional's concern with symptom control to recovery of a good quality of life as defined from the perspective of the individual patient concerned (Allott Reference Allott, Loganathan and Fulford2002). Although ‘recovery’ is a contested notion, it can be linked to experiences of inequality and injustice (Harper Reference Harper and Speed2012), which are likely to be mitigated by an appreciation of the validity of different values if this produces genuinely shared decision-making.

This is therefore a shift of values. Recovery practice involves a shift in focus from what is important from the perspective of the professional to what is important from the perspective of the patient. This shift can be difficult to put into practice, partly it seems because clinicians’ values may differ from those of patients, as shown by Thornicroft et al (Reference Thornicroft, Farrelly and Szmukler2013), who found that implementing joint decision-making in practice was hard to achieve. As already indicated, individual values are highly variable. But epidemiological and other research suggests that, where professionals are by and large concerned with such matters as diagnosis, symptom control and risk management, patients (particularly those with long-term complex conditions) are more concerned with housing, employment and personal relationships. Therefore, recognising these differences and developing the further values-based skills to work with them successfully are a key to recovery practice (South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust 2010). Importantly, this may involve other members of the multidisciplinary team – such as nurses and social workers – whose values may be different again. So the skills needed for values-based interprofessional care may also be important to recovery practice.

This is why values-based practice has for some time been a core theme in recovery (Roberts Reference Roberts, Dorkins and Wooldridge2008; Slade Reference Slade2009). Montgomery indeed makes what is, in all but name, recovery practice the basis of consent in psychiatry. However, the challenge in Montgomery, as in recovery practice, is that the shift of values underpinning both is not absolute. It is a shift only in the balance of values. This may be challenging enough in recovery practice (as with ‘positive risk management’ for example (Robertson Reference Robertson and Collinson2011)). It becomes critical with compulsory treatment.

Compulsory treatment

The connections between the Montgomery ruling and mental health legislation have yet to be tested through the courts. There is, after all, something of a contradiction in the idea of applying standards of legal consent to non-consensual treatment. But as things stand, it seems likely that Montgomery applies to any capacitous patient whether treated under the (non-capacity-based) Mental Health Act 1983 or not. Moreover, consent is required for certain types of treatment for mental disorder administered under Part IV of the Act (as amended in 2007): psychosurgery under section 57, administration of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) to a capacitous patient under section 58A and, under section 58, prolonged medication when the patient has capacity. So Montgomery has an important role to play in these situations. This is emphasised by the Mental Health Act Code of Practice (Department of Health 2015), which in paras 24.36 to 24.39 deals with the provision of information. For instance,

‘The information which should be given should be related to the particular patient, the particular treatment and relevant clinical knowledge and practice. In every case, sufficient information should be given to the patient to ensure that they understand in broad terms the nature, likely effects and all significant possible adverse outcomes of that treatment, including the likelihood of its success and any alternatives to it’ (para. 24.37).

However, even when compulsory treatment is administered under section 63 (Treatment not requiring consent), the Code of Practice at para. 24.41 stipulates that the patient's consent should still be sought ‘where practicable’, suggesting that the Montgomery ruling should be relevant and reflected in good psychiatric practice (and see Yousif Reference Yousif2016).

Montgomery thus requires a balance of values with non-consensual compulsory treatment (of a capacitous patient) under the Mental Health Act just as it does with consensual treatment (of a capacitous patient) in recovery practice. Non-consensual treatment decisions are, by definition, not based on agreement between clinician and patient. But using a values-based approach they may nonetheless be shared decisions in being made within a framework of shared values. The Mental Health Act, moreover, comes with an in-built framework of shared values provided by the guiding principles in the Code of Practice (Department of Health 2015: pp. 22–Reference Roberts, Dorkins and Wooldridge25). These principles directly reflect the Montgomery requirement that the patient's values should be at the heart of decision-making. They stipulate:

-

• the need for independence and the promotion of recovery

-

• participation and involvement

-

• recognising and respecting ‘the diverse needs, values and circumstances of each patient’

-

• that the purpose of treatment is to address the individual patient's needs, ‘taking into account their circumstances and preferences where appropriate’

-

• recognising ‘as far as practicable […] the patient's wishes’.

Training materials based on these guiding principles developed by the Department of Health to support implementation of the Act had the aim of limiting the use of compulsory treatment (Fulford Reference Fulford and King2008). Since implementation, however, there has been growing concern that the number of detained patients has actually risen, with potentially adverse effects on clinical outcomes (House of Commons Health Committee 2013). One explanation for this rise in compulsory treatment is that concerns about safety have in practice outweighed the patient-focused values expressed in the guiding principles (Fulford Reference Fulford, Dewey, King, Sadler, van Staden and Fulford2015). Meanwhile, there is evidence that advance statements lead to ‘a statistically significant and clinically relevant 23% reduction in compulsory admissions in adult psychiatric patients’ (de Jong Reference de Jong, Kamperman and Oorschot2016), suggesting that acknowledging the patient's views and values is beneficial. Applying Montgomery therefore to compulsory treatment, supported by a values-based approach to balanced decision-making within the guiding principles, could help to reduce use of compulsion and thereby improve clinical outcomes.

In any case, Montgomery argues powerfully in favour of a manner of approach to patients. Patients are seen as persons with rights and values, which must be acknowledged and respected. On the one hand, therefore, practitioners should be willing to accept some risks in order to respect (as Lady Hale in Montgomery described it) ‘a person's interest in their own physical and psychiatric integrity, an important feature of which is their autonomy, their freedom to decide what shall and shall not be done with their body’ (para. 108). Taken seriously, this might even lower the tendency to instigate treatment under compulsion. On the other hand, even if compulsory treatment is given, it should be given with as little restraint and with as much real respect as possible.

Conclusions

In this article, we have described the new legal standard of care in consent set out in the recent Supreme Court Montgomery ruling, indicated how the balanced value judgements it requires are supported by raised awareness of individual values and other elements of values-based practice, and given examples of how Montgomery and values-based practice together support shared decision-making in psychiatric practice (Coulter Reference Coulter and Collins2011).

Psychiatry, like other areas of medicine, is caught between the twin pressures of ever-growing demands and ever-shrinking resources. The focus in early commentaries on the new duty to disclose material risks imposed by Montgomery understandably led to concerns that this would add to these pressures. Understood rather as we have presented it here, as requiring partnership in clinical decision-making, Montgomery, far from adding to the pressures of practice, becomes an ally to professionals and patients alike in seeking the resources needed to deliver best practice in contemporary clinical care.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 The Bolam principle:

-

a has been reinforced by the Montgomery Supreme Court judgment

-

b was originally formulated to test decision-making capacity

-

c continues to be relevant as the applicable standard of care for technical aspects of diagnosis and treatment

-

d is named after the English actor James Bolam

-

e established shared decision-making among healthcare professionals.

-

-

2 The model of consent enunciated by the Supreme Court in the Montgomery decision:

-

a calls for a revision of General Medical Council guidance on consent

-

b establishes that only common side-effects of a treatment need to be disclosed to a patient

-

c establishes that only serious side-effects of a treatment need to be disclosed to a patient

-

d establishes that both serious and common side-effects of a treatment need to be disclosed to a patient

-

e includes disclosure of benefits as well as risks by way of dialogue between the clinician and patient.

-

-

3 Values-based practice:

-

a requires complete agreement between those involved in a given decision

-

b at its base requires an awareness of values

-

c provides a hierarchy of values to guide decision-making

-

d privileges the values of a reasonable body of medical opinion

-

e is the antithesis of evidence-based practice.

-

-

4 Recovery practice:

-

a is compatible with values-based practice

-

b ensures that health professionals focus correctly on cure

-

c depends on professional judgement to establish thresholds of disability

-

d is incompatible with the treatment of chronic mental illness

-

e is incompatible with shared decision-making.

-

-

5 The Montgomery judgment:

-

a concerned a patient with schizophrenia in Broadmoor Hospital who developed gangrene in his leg

-

b is less relevant to shared decision-making than the Sidaway case

-

c is relevant even where the Mental Health Act has been used to detain someone against their wishes

-

d establishes informed consent on the basis of the ruling of Lord Justice Montgomery

-

e undermines clinical expertise.

-

MCQ answers

1 c 2 e 3 b 4 a 5 c

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.