The final two chapters of this book will focus upon the Great War and assess the opportunities it provided for the woman surgeon, both on the home front and, firstly, as near to the various battlefields as women were permitted. It is vital to recognise from the outset that women were aware of the need to take advantage of what warfare could offer them as well as their desire to be as useful as possible to the war effort. No one expected the situation to last beyond the span of the fighting and this was acknowledged at the time.Footnote 1 In 1917, the Girl's Own Paper warned youthful aspirants to a surgical career not to be ‘dazzled by the glamour’ of women's co-operation with the allied armies: ‘these are temporary conditions, and when peace reigns once more it will not be from the military hospitals that the first demands upon them will be made’.Footnote 2 When considering female participation in wartime surgical activities, the excitement of the performance must be measured against the knowledge of its temporality. Additionally, however, the embracing of this moment as an opportunity to enhance wider skills and techniques, the valuable experience gained, must also be acknowledged. The Great War might have provided a chance of a lifetime for women surgeons, but what dominated the thoughts of those involved was that they needed to obtain useful work, rather than worry about its inevitable brevity.

In a recent study of British military medicine between 1914 and 1918, Mark Harrison laments the ‘fragmented’ nature of medical history focused on this period. While specific, detailed accounts increase in numbers, works of synthesis are few, ensuring that ‘a rounded view of what medicine meant to contemporaries’ is missing.Footnote 3 Harrison also notes the absence of the mundane from analyses of wartime medicine. Shellshock or venereal disease has proved more fascinating than the everyday discomforts of trench foot, for example.Footnote 4 The heroic actions of a single surgeon in saving the life of a dying patient is far more exciting than the prosaic reality of the team effort required to keep him alive before, during and after the operation itself. In these two chapters, I want to provide a synthesis of women's surgical participation in the Great War in order to examine what performing surgery on soldiers meant to a number of women surgeons and, by extension, their patients. Although I will explore the undoubted thrill experienced by women charting new surgical territories, I agree with Harrison that the quotidian requires attention too.Footnote 5 More often than not, the momentary excitement stifled the exhaustion, momentarily. Near the battlefield, the stoic feats of 24-hour operating were few in comparison with the many days of lull, of the treatment of civilians and routine procedures on hernias and appendixes. The watching and waiting alternated with the constant need to generate electricity for vital X-ray equipment, let alone light for the operating theatre. At home, unprecedented new posts in general hospitals increased exponentially between 1914 and 1918 for women as more medical men left for the front, but both here and in women-run institutions day-to-day survival necessitated financial support, harder to come by in wartime. Indeed, the division between work at home and at the front does not hold in some instances. Louisa Aldrich-Blake and Agnes Savill, for example, worked both at Royaumont in France and at the RFH and the NHW respectively during the war. In considering a variety of wartime case studies, but without losing focus on the vicissitudes of experience, a more complex picture of the activities of the woman surgeon between 1914 and 1918 can be obtained.

‘Surgery Just as Men Do’

Some women surgeons offered assistance to the military as soon as war broke out, but, turned down again and again, their enterprise was largely self-initiated and their services given to their country's allies.Footnote 6 The two most prominent organisations established were the Women's Hospital Corps, set up by Flora Murray and Louisa Garrett Anderson in 1914 and backed by the Women's Social and Political Union, and the Scottish Women's Hospitals (SWH), founded by Elsie Inglis, which came into existence a year later with support from the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies.Footnote 7 Garrett Anderson and Inglis had surgical backgrounds, but, as women, were considered unsuitable for frontline service, whether alongside men or on their own. A gamut of reactions to women's proposals, summed up succinctly by Murray, included disapproval, curiosity, amusement and obstinate hostility.Footnote 8 Such responses to the female surgeon were, of course, not new, but, after proving themselves in their profession for half-a-century and gradually having gained the acceptance of their colleagues, rejection when their country needed qualified and experienced doctors most was hard to take.Footnote 9 Obstinacy extended both ways, however, and women were undeterred. Garrett Anderson and Murray set up in Paris, impressed the relenting authorities enough to be offered a hospital at Wimereux, and then returned home in 1915 to take charge of what became the Endell Street Military Hospital, run entirely by women. The Scottish Women's Hospitals established units across Europe, treating allied soldiers in France, Serbia, Greece, Corsica, Romania and Russia. An advance casualty clearing station was also run by the Scottish Women at Villers-Cotterets, 40 miles away from Royaumont, until it was overrun by the Germans almost a year after its establishment, in the summer of 1918.Footnote 10 When they were presented with what Murray labelled ‘an exceptional opportunity in the field of surgery’, women surgeons grasped hungrily at the chance afforded them.Footnote 11

In a letter written from Serbia in January 1917, Louise McIlroy, Chief Surgeon of the SWH Girton and Newnham Unit (GNU), lamented the possibility of being forced to share her position with a male Serbian colleague. ‘It not only breaks with our trust with the public, who supply us with funds for women only’, McIlroy fumed, ‘but it takes away from us the one part of our work that has been doubted so much at the beginning, namely the capacity to do Surgery just as men do.’Footnote 12 Here, McIlroy illustrated the paradox of the woman surgeon in the Great War. The exclusiveness of the hospitals run only by women, set up initially because of opposition to their serving near the battlefield or with the army, was what made them unique and worthy of financial support. Simultaneously, however, in order to be successful, women needed to draw attention to the fact that they were performing surgery exactly as men did. That, in effect, there was no difference at all in their mode of operating. Ideally, the woman surgeon at the front had to be both female and male in her approach to avoid loss of public support and professional valuation. This tricky balancing act, one which female surgeons had, of course, been carrying out since their entry into the medical profession, was exacerbated by wartime conditions. As such, accounts of superhuman capabilities characterised depictions of surgery by women, which stressed the difficulty of procedures and feats of endurance. Any cracks were to be swiftly covered over. If war was the best school for surgeons, then women were being tested in uncharted surgical territories and could not be found wanting.

What was so astounding about the private correspondence of women surgeons who served abroad between 1914 and 1918 was that they did not question their ability to carry out procedures with which they could not have been familiar. Inexperience, according to newly qualified Leila Henry, who became a junior surgeon at Royaumont, was simply not to be acknowledged. Although she had only graduated in 1916 and spent a year at the Sheffield Royal Infirmary, Henry expressed no doubt about her surgical skills, which were honed at an institution situated in a bustling city attacked by Zeppelin raids. Treatment of accidents, common to industrial centres, as well as the more recent German bombing of munitions’ targets, gave Henry an insight into injuries caused by the explosions of modern warfare. Despite her youth and what would have been perceived as inexperience, Henry claimed confidently that: ‘I felt equally competent to deal with war injuries, given an opportunity’. Initially rejected by the SWH's head office in Edinburgh, Henry retorted that ‘youth had nothing to do with it; it was experience that counted!’Footnote 13 Although Ruth Verney only witnessed the very end of the war when she left for Salonika in autumn 1918, she was desperate to learn as much as possible, in addition to developing her clinical skills. In a letter to her family, she noted that, along with another young doctor, only a year her senior, ‘we feel we must do some work no matter whether it has all been done before or not’.Footnote 14 Verney's youthfulness caused a French colleague to wonder if she had begun her studies in the cradle, but Verney did not mind.Footnote 15 When looking back upon wartime adventures in the late 1970s, she remembered with fondness her health, strength and unceasing happiness. Everything was ‘frightfully interesting’, even the treatment of an injured thumb in one of the villages.Footnote 16 Adaptation of existing expertise and strong self-belief were what gave women the confidence they could operate as well as men, even if the surroundings and procedures were foreign to them. What they did not know, they could learn as they worked, and they were more than eager to do so.

Isabel Emslie went one step further than Henry and Verney and, in addition to energetic youth and health, added risk to her wartime experience. After working with the GNU under McIlroy for three years, in the summer of 1918 she took charge of her own unit in Ostrovo, Serbia. For Emslie, it was either ‘lack of foresight’ or ‘recklessness’ which allowed her to live from day to day, accomplishing tasks ‘without seeing half the difficulties’.Footnote 17 When she stayed on in Serbia after the war ended, operating on civilian cases in Vranja, it was temerity which kept her going. As the only capable surgeon there, Emslie undertook major, specialist operations which would never have ‘fallen to [her] lot’ at home.Footnote 18 Little experience in plastic operations for burns, for example, did not matter. Emslie ‘did [her] best and nature gracefully completed my efforts’.Footnote 19 The knowledge that war would not last indefinitely haunted the women throughout their time abroad. An awareness that, as Elizabeth Courtauld, surgeon at Royaumont, put it in letters of November and December 1918 that the ‘congenial work’ of these ‘gorgeous times’ would soon be over; the parting horrid and the breaking up of everything, though inevitable, distressing.Footnote 20 The determination to take advantage of the opportunities was evident; no one wanted to waste a moment. Neither were those who were intending not to utilise their surgical skills in the future as welcome as those were dedicated to the specialty. When Frances Ivens, the Chief Surgeon at Royaumont, sent a request in the early stages of the hospital's existence for a new member of staff, she was very clear about the person she wanted:

We need another good junior surgeon to take the place of Miss Ross in a month. I should like someone who is working for the US [sic] or FRCS, having had an H.S. post, if possible, but recently qualified. It is a waste to take on general practitioners who will not make use of the surgical techniques they acquire.Footnote 21

While military surgery was unlikely to sustain most surgeons’ careers, Ivens wanted to ensure that those volunteering were there for professional enhancement. Surgery carried out during wartime could only be beneficial to anyone serious about learning and progressing as surgeons when they returned home.

This was precisely how the few who left Royaumont under dark clouds reflected upon the institution's operations. Doris Stevenson, who went to the hospital as an orderly in May 1918, lasted three weeks at her post. Already experienced in nursing, having served six miles from the front since November 1916, Stevenson was horrified by conditions at Royaumont. Among a long list of complaints about the standards of hygiene and chaotic organisation, Stevenson voiced her belief that ‘[t]his hospital appears to be a school for women doctors at the expense of the sisters and us organised, undisciplined orderlies of good will and intention’.Footnote 22 In a later letter, Stevenson claimed that the staff existed in a rarefied exalted state, which bore no resemblance to reality: ‘the whole spirit of Royaumont is ludicrous to the few of its members who have seen something of the world, the spirit is positively Prussian in its puffed-upness’.Footnote 23 Frances Ivens’ retort was blunt, addressing directly the accusation that the surgeons benefited at the expense of the sisters and orderlies: ‘such a statement [was] merely malicious and devoid of fact’. She added that the doctors worked ‘as hard if not harder than others, and both day and night’.Footnote 24 In gathering witnesses to testify against Stevenson's attack, Ivens included a letter from Agnes Anderson who stated, simply, that how the hospital was regarded by the doctors was no concern of the orderlies.Footnote 25 While this did not condone the accusations levelled against the surgical staff, neither did it deny them. If Royaumont resembled a school for the development of women's surgical skills, Anderson remained noticeably tight-lipped on the subject, while actively and vociferously defending other criticisms of the way in which the institution operated.

Another woman who left Royaumont dissatisfied with what she saw made pointed accusations about the surgery itself. In October 1915, Dr Margaret Rutherford resigned her post in protest at the recklessness of surgical procedure at the hospital. Since Royaumont's opening at the beginning of the year, cases had been light, but recently, Rutherford remarked, more serious injuries had been sent. Of particular concern for Rutherford were the cerebral injuries; the trephining of two patients, for example, had produced ‘grave results’. Three days before her resignation, another case had been received, where surgical treatment was necessary. Rutherford feared a repetition of previous outcomes and advised Ivens, ‘for her own sake and that of the Hospital’, to seek a second opinion about the advisability of going ahead. Ivens removed Rutherford publicly from the theatre and, despite reassurance that the suggestion had been friendly rather than critical, Rutherford felt she could only resign rather than suffer from her chief's lingering resentment at this reaction.Footnote 26 Doubt about surgical capabilities in wartime situations was clearly not restricted to male colleagues. This letter was serious enough to ensure that Beatrice Russell, as honorary secretary of the Personnel Committee in Edinburgh, made a swift visit to France, ‘as a medical woman can see with expert's eyes what is being done’, noted Miss Loudon, Royaumont's administrator.Footnote 27 As the women wanted to be seen in the best possible light by the public at home, who were funding their enterprise, it was important that reports placed in suffrage publication Common Cause were positive about surgery carried out at Royaumont. Even deaths were concealed. As Loudon noted, only half-jokingly, a few days after Rutherford's resignation: ‘Another rather dismal report for we have had two deaths (please don't send this information to the Common Cause).’Footnote 28 This desperation to keep even a small number of fatalities from the public was translated into a report in the periodical which simply noted the visit of Russell and Miss Kemp and told the story of ‘A Typical Breton Patient’, shoemaker Jean Carron.Footnote 29 A week later, Russell's report appeared, although the focus was on the day-to-day running of Royaumont. While the work was ‘the real soul of the Hospital’ ‘one cannot speak in detail in a nonmedical journal’. Confidence and satisfaction dominated this account, however, in what was designated an ‘entirely surgical’ institution.Footnote 30

This fear of letting the public see inside the operating theatre dogged the SWH. What the women wanted their supporters to see were heroic, superhuman efforts, which saved the lives of their patients; the ‘operating, operating, operating’ carried out by candlelight during constant threat of attack.Footnote 31 Surgeons could ‘devise no system of shifts’, unlike the rest of the teams, because even if they did have the luck to spend four or five hours in bed, ‘they were constantly being called up to serious cases and to emergency operations’.Footnote 32 They certainly did not want the circulation of tales about breakdowns, sheer exhaustion and occupational injuries. Ivens’ focus in her BMJ article on ‘The Part Played by British Medical Women in the War’ was surgical and scientific achievement, despite personal risk and hardship.Footnote 33 This was in stark contrast to some in the official service of the army, who offered franker details of physical and mental collapse. In the BMJ of 2 June 1917, two months before Ivens’ assessment of women's contribution, Surgeon-General Sir Anthony Bowlby and Colonel Cuthbert Wallace described the current surgical situation in France. They remarked upon the stoicism required for operating day and night at casualty clearing stations near the front and consequent necessity for a relay of personnel. In spite of shift patterns, however, they noted that the work was ‘exceedingly trying, and it must be reckoned on that not a few of the staff will be more or less knocked up after three or four weeks of it’.Footnote 34 Nearly 60 years after the end of the war, Ruth Verney was asked if she found the work ‘too demanding physically’. ‘Oh no’, she replied. ‘I was very healthy. I got jaundice once but it was soon over.’Footnote 35 Even in women's private letters, ‘knocking up’ was viewed with horror. Royaumont was ‘not a place for delicate people or those who tire easily’, as orderly Agnes Anderson remarked.Footnote 36 Minor illness was inevitable, but to be sent home for what the surgeon Elizabeth Courtauld named darkly as ‘urgent reasons’, even if it meant undreamt-of leave, was dreaded.Footnote 37 The terror of missing out was palpable. As radiographer Edith Stoney succinctly concluded: ‘I could not have faced the risk of being inefficient. […] We are all out to do the best we can and give the best help we each of us can give – and other things matter very little these days.’Footnote 38 Exposure of any weakness to a wider audience was, therefore, tantamount to treason, as one former member of Royaumont was to discover.

Vera Collum, radiology assistant and part-time chronicler of the SWH's exploits for the British press under the pseudonym ‘Skia’, felt the wrath of her colleagues when her notes were published without permission. As they had successfully concealed any dissent from the Common Cause throughout the war, the publication of biographical details, complete with unexpurgated episodes of ‘knocking up’, created havoc. The offending article appeared at the end of December 1918 and was intended to cheer the Croix de Guerre awarded to the staff of Royaumont and Villers-Cotterets. Instead, gossipy anecdotes drew attention to the breaking down from overwork and overstrain of Augusta Berry, assistant physician and surgeon, Ruth Nicholson, second surgeon, and Miss Martland, surgeon. That it was the surgeons who had ‘knocked up’ presented a direct link between the operating theatre and the weakness of the female surgeon. Collum was additionally horrified at her own presentation, which had been written in the third person, but had commented on the burns sustained to her hands and neck from persistent X-ray exposure. Again this linked the whole team to physical suffering sustained while carrying out the essential requirements of modern surgery. Such intimate detail caused Collum to shudder: ‘[t]he allusions to my X ray burns simply made my flesh creep with horror!’Footnote 39 The publication of unguarded notes meant for private eyes only ‘constituted a breach of good taste’. Collum was now forced to ‘smooth down the unfortunate victims’.Footnote 40 While her health and strength had not been questioned, Ivens retorted that they ‘all feel that it is a pity there is not more supervision of the Press work by a medical member of the Committee who would safeguard our interests from the ethical point of view, and who would see the right papers were supplied with information’.Footnote 41 Collum's oversight was all the more surprising given her letter of July 1915 about the necessity of a press campaign to garner more funds for the SWH. Royaumont was doing such good work removing prejudice against women surgeons that it was necessary to ‘“boom”’ it even more carefully in the press. In words that must have come back to haunt her, Collum concluded: ‘There is a good deal more method and science in a press campaign than most amateurs realise. Monday's mutton must not be recognisable in Tuesday's stew, especially when the stew and the joint are for different households.’Footnote 42 In December 1918, Collum had accidentally permitted communal dining on the meat and bones of the Royaumont staff; her overzealousness in promoting their achievements instead exposed their frailties.

Challenges Posed by Surgery during the Great War

The questioning of surgical ability was not alien to those faced, for the first time, with the horrors of modern warfare. Surgery during the Great War was pursued with caution, doubt and instinct. Experience could be drawn upon, but every injury sustained revealed something new for even seasoned army surgeons.Footnote 43 Women were not any different in this respect. Many had, of course, as has been shown throughout this book, considerable understanding of complex abdominal procedures, as well as a desire to take up and perfect risky surgical treatment for malignant diseases. While they had dealt with women and children on the wards, LSMW students had been attending Gate, the RFH's Casualty Department, as part of their training since the association between the two institutions began and would have encountered male victims of industrial accidents, for example.Footnote 44 Verney and Henry had gained experience at home in Manchester and Sheffield respectively, dealing with traumatic injuries caused by workplace or wartime incidents.Footnote 45 Convalescent soldiers were encountered on the wards by women at home before they departed for service abroad.Footnote 46 Cooter's claim that, by the end of the nineteenth century, children's hospitals were predominantly surgical, dealing largely with orthopaedic cases, is pertinent to consider in this context.Footnote 47 Many women had experience in children's hospitals and this could have given them greater confidence in approaching the bones and joints of men. In 1912, for example, Garrett Anderson and Murray had established the Women's Hospital for Children in Harrow Road, West London, which held a clinic for London County Council orthopaedic cases on Friday mornings.Footnote 48 Elsie Inglis worked at the Edinburgh Hospital and Dispensary for Women and Children and the Hospice, which saw an increase in its surgical work in the decade before the war started.Footnote 49 Although the surgery was predominantly gynaecological, Inglis and her colleagues also treated diseases of the bones and joints. It was accepted, both by the public and the profession, that women would care for children, but, as Cooter suggests, this could have given anyone working in such institutions a relatively free rein to experiment with new techniques.Footnote 50 This is not to suggest that women were as well prepared for their military surgery as they would have desired, but that they were often little different to male colleagues from general practices, who had perhaps performed only minor surgery in recent years or other men with specialties which were not directly applicable to the results of warfare. That they had carried out any major surgery was an undoubted benefit. Such were the conditions experienced on the Western Front, however, that even the most well-trained professional military surgeon had a great deal to learn.

Articles in the medical press about the progress of surgery during the Great War make interesting reading, allowing an insight into the ways in which surgeons relearned their craft between 1914 and 1918. The newly established British Journal of Surgery, for example, was rapidly filled with case studies of every kind of injury.Footnote 51 When the Second World War was in its infancy, Ivens reminded colleagues of the need to publish surgical developments for those operating at the front and beyond. In a letter of December 1939 to the BMJ, Ivens exclaimed ‘[m]ay I now too, even after this lapse of time, acknowledge with gratitude the value of the articles on fractures under war conditions by Sir Robert Jones which appeared in your journal in 1916’. ‘They were read and reread’, she continued, until the pages were ragged!’Footnote 52 While surgeons could draw upon experience to assist them, heavily illustrated, multi-part articles advocating best practice were evidently much in demand. Indeed, surgeons learned from the work of others and applied that research to their own circumstances, whether through reading medical journals or actual observation of others’ practice. Instinct was only part of the surgical process. At an RAMC meeting in January 1917 to consider the advisability of laying down guidance for the treatment of war wounds, Professor James Swain claimed that ‘progress is not made from uniformity’, while Sir Berkeley Moynihan offered this assessment on surgical progression: ‘[t]he whole progress of surgery has depended on the different interpretations that different men have given to the same methods of solving the same problem’.Footnote 53 Bowlby and Wallace's 1917 synthesis of ‘The Development of British Surgery at the Front’ offered a number of ways in which the surgeon at the front learned and relearned how to operate. Really sound opinions could only come when the surgeon had considerable experience of the injury – in this case, the necessity of amputation. Without this knowledge, the advice of those who had been able to form judgement through practise was the best bet before a decision was made. Although they pointed to general rules of operation, Bowlby and Wallace also drew attention to the necessity of departing from ideals when the condition of either patient or limb was in doubt. ‘Working out the best method of treatment’ was another means of proceeding when new problems arose, as in the prevalence of gas gangrene on the Western Front, something to which this chapter will return later. Surgical ‘working out’ was encouraged by bacteriological analysis in this particular instance. Without complete answers, suggestions could suffice. The authors continued to discuss treatments ‘in vogue at the present moment’, implying both that they were not previously popular and that they were likely once again to fall out of fashion. Abdominal surgery, for example, had gone from being considered impossible to prevalent. Confidence was attained, in this field, through attempts, failures, and continual risk: ‘each man had to learn the best methods for himself’. Individual experimentation was coupled with ‘diffusion of more accurate knowledge’, obtained via the ways in which the wounded were transported from field to hospital.Footnote 54 Similarly, head injuries had been operated upon immediately, as they were in civilian practice, but observation led to the encouragement of a different procedure, which allowed rest before surgery. Discussion and debate, when coupled with close attention to casualties’ reaction to treatment, altered how surgeons operated. When faced with the challenges of modern warfare, specialist surgery was forced to give way to general approaches which then, once again, and through practise, became expertise.Footnote 55 Surgery during the Great War developed through the experience of experimentation.

By the 1910s, as we saw in the previous chapter, risky surgical procedures were favoured by those attempting to treat grave malignancies. As Bowlby and Wallace illustrated in 1917, the Great War further revealed the value of a willingness to experiment in order to achieve the best results. However, this radical approach was tempered with a conservative bent. This was especially the case as far as amputation was concerned. It did not take long for surgeons at the front to realise that preservation of limbs was vital for soldiers’ eventual return to civilian life.Footnote 56 Patients resisted surgery when they became aware that they might come round from an anaesthetic minus a useful body part, whether that was because of their terror at loss of livelihood or their religious beliefs. The administrator of Royaumont, Miss Loudon, wrote to the Edinburgh Committee to relay a conversation she had had with a patient whose finger had been saved by Frances Ivens. ‘“If I had been in a Military Hospital”’, he confided, “I should have lost my finger”’. It would make such a difference in the future if they had the ‘proper number of fingers’.Footnote 57 When writing about Royaumont in Blackwood's, Collum referred to a number of patients who recoiled initially in terror at what they believed were ‘senseless slashes of the surgeon's knife’.Footnote 58 In an age of the radical approach in some areas, however, amputations, and the pre-anaesthetic, pre-aseptic showmanship that was inextricably attached to such procedures, had correspondingly decreased. With time to operate, thanks to the unconscious patient, surgeons, either in military or civilian practice, were removing fewer limbs than their predecessors.Footnote 59 If surgical theory and practice had turned towards conservation for procedures such as amputation,Footnote 60 the war forced rethinking about the best way to treat mangled body parts. The injuries seen by surgeons from the battlefields were unlike those experienced even just over a decade earlier on the veldt of South Africa. Differences in the terrain soon made themselves clear. Wounds from modern warfare were exacerbated by the richness of the soil in which the injured fell, which, in turn, swiftly contaminated wounds.Footnote 61 Gas gangrene was the bane of surgeons, whose successful operations would be rendered null and void by this evil-smelling, ferocious killer. Medical treatment, and especially tight bandages or plaster of Paris, effectively sealed infections. As Ivens noted in 1939, an application of bandages which under ordinary conditions would earn a special commendation killed rather than cured.Footnote 62 Surgeons learned that instant operative action was not always the best course to take. While an urgent response was necessary with war wounds, it was not always surgical. Watching the patient closely was sometimes the best way to react. The result of even slight wounds, if infected, could change the course of treatment or the condition of the injured man instantly. Although they were reluctant to admit it,Footnote 63 surgeons needed the assistance of nurses and orderlies, as well as the scientific confirmation which could be obtained through pathological and bacteriological findings or X-ray images. What had once been seen, at best, as ancillary to surgery became vital in this new environment in anticipating and proving surgical diagnoses.

Women's Surgical Experiences

With expertise in a variety of abdominal procedures, a number of women had a surgical advantage over some male counterparts. They had also revealed a willingness to experiment with new techniques, which proved necessary to the vicissitudes of wartime injuries. Adaptations were necessary in some cases, however, in order to permit comfort and ease of movement in the theatre while operating. For example, white overalls sent to Royaumont for the theatre were ‘more suitable for the other sex’; they were too short and very full around the waist, while the mackintosh aprons were not long enough to cover skirts sufficiently.Footnote 64 What women surgeons actually did during the Great War and how they were received by their patients has been obscured by rhetoric, the hagiography that Geddes has discussed, and the lack of available statistics.Footnote 65 For example, the problematic Corsican Unit, in 1917, was described as having ‘very confusing and badly kept records’, and this was not unusual.Footnote 66 Women had a different war to some men in that they did not operate at casualty clearing stations but at base hospitals further down the line or, as Garrett Anderson, Murray, or the radiologist Florence Stoney served, in military hospitals at home.Footnote 67 This meant that they often received wounded who had been patched up and sent on, ensuring that they had to deal with the results of initial treatment as well as carrying out their own procedures. Royaumont, for example, was 25 miles away from the firing line and ten from Creil, which was the distributing centre for the French wounded.Footnote 68 It also meant that they received a number of cases whose injuries were slight, but who went on to develop gas gangrene. They were, therefore, in an ideal position to utilise experimental resources produced by laboratory studies. Royaumont, as we shall see, carried out trials of serum produced by the French to combat gas gangrene and Endell Street was given bismuth-iodoform-paraffin paste (B.I.P.P.) which ensured wounds could be healed quicker without constant, disruptive changing of bandages.Footnote 69 Women's hospitals were sites of scientific, as well as surgical experimentation. Consequently, they are ideal for examining the relationship between very different members of a surgical team and assessing the ways in which surgery between 1914 and 1918 was assisted by, relied upon and incorporated developments in radiology and bacteriology. This is not to claim that the contact between surgery and its satellites was without friction in practice, but that debates between them invigorated surgical technique and saved lives and limbs.

In similar fashion to trench warfare, there were rushes and lulls in surgery near the front lines. Most accounts published about women's hospitals focused on the difficulty of the cases and the skilfulness of the treatment given, prompted by the surgeons themselves and the committees concerned with press matters at home. Mrs Curnock's Daily Mail account of a ‘Women's War Hospital’ in October 1914 followed a day's action at the Hôtel Claridge in Paris, recently established by Garrett Anderson and Murray. The tone was sentimental, stressing the devotion of the ‘wonderful women doctors’ who operated tirelessly ‘[a]ll day and all night’ to save ‘plucky’ Tommies, who arrived in a constant stream, filling all eighty beds.Footnote 70 Beyond the seriousness of the operations, head and limb cases were mentioned; the two interviewees had ‘smashed thighs’ and were proud of their ‘twin’ injuries. By far the most dramatic, heavily publicised encounters were those of the SWH. Two instances provoked especially awed coverage. In Serbia, Elsie Inglis, the Commissioner of the SWH, and her units were the focus of much scrutiny when the enemy overran the country. Inglis’ unit and that of Dr Alice Hutchinson remained to tend to their Serbian patients, while the others retreated across the mountains.Footnote 71 The National Weekly in April 1917 focused on the perilous experiences of escape and imprisonment, while stressing the women's professional disappointment at not being able to go on caring for their charges.Footnote 72 Elsie Inglis ‘related her adventures’ to an eager Common Cause on her return via Zurich in the late winter of 1916, noting that they had also treated Germans when their hospital was taken over.Footnote 73 By the autumn of 1916, the indefatigable Inglis was off again in order to set up another unit in Russia. Upon her death after returning from the Russo-Romanian front in November 1917, obituaries were filled with accounts of stoicism, freedom from self-seeking, and professional detachment combined with ‘born leadership’.Footnote 74 Eulogies stressed her universal appeal. She was ‘“Our Doctor Inglis”’,Footnote 75 deeply beloved and venerated. For her colleagues, she was an exemplar of high energy and unselfishness, the ultimate stimulation to greater effort.Footnote 76

The second prominent exposure of the woman surgeon's selfless courage came in June 1918 at Villers-Cotterets. ‘Bombed Hospital Amputations by Candlelight’ was the sensational headline in the Glasgow Herald. This was succeeded by the personal account of X-ray assistant, Marion Butler, which stressed the privations experienced by the surgeons, who even had to prostrate themselves in a field to escape German planes.Footnote 77 Collum also provided a detailed account of the hospital's candlelit operations during German aerial bombardment and the staff's daring escape.Footnote 78 In this article, Collum used the ways in which the women operated during the aftermath of the Battle of the Somme and the summer of 1918 as evidence of theory in practice:

So chance – or destiny – flung our little emergency unit of women into the one spot in the whole of France where it could prove of greatest value during that great struggle, and that later struggle – for Paris – in June-July 1918, and where it could also seize the opportunity to translate its experiment into successful enterprise, its improvisation into a perfected organisation, functioning at high tension during two critical periods of stress and strain.Footnote 79

Both periods of surgical frenzy tested resources. Collum adopted a rope metaphor to examine how the women fared during the physical and psychological strain of a rush. After the Somme, they were ‘stretched taut’, but ‘not a strand of the rope was frayed’.Footnote 80 During the events of May and June 1918, they were ‘tried up to and beyond our strength’; but with a ‘frayed’ rope, even with some broken strands, ‘it held’.Footnote 81 At the end of May, Villers-Cotterets had been bombarded aerially night and day, which necessitated a blackout everywhere except the operating theatre. This was run by carefully shaded candlelight and appeared a ‘hell and a shambles’. Wounded men were ‘carried just as they had fallen’. There were ‘[n]ine thigh amputations running; men literally shot to pieces; the crashing of bombs and thunder of ever-approaching guns’: ‘[T]he operating hut, with its plank floor and the tables and the instruments on them literally dancing to the explosions; the flickering candles; the anxiety lest the operated cases might haemorrhage and die in the dark.’Footnote 82 This frenzy was compounded when staff and wounded made their way back to Royaumont. In 15 days, noted Collum, they had brought in, X-rayed and operated upon 1,000 wounded. Collum herself made 85 X-ray examinations in 24 hours. Two emergency operating theatres opened, ensuring that there were three working all day, two at night. With such pressure, Ivens and her deputy, Ruth Nicholson, slept only three hours a day for a fortnight. X-ray and the rest of the theatre teams worked 18 hours, while resting for six. Thanks to their superhuman efforts, only 40 of the 1000 wounded men died.Footnote 83

Personal correspondence, manuscripts and reports confirmed the dramatic nature of the summer offensive. The matron, Gertrude H. Lindsay, remarked on the surgical staff's incredible commitment; they ‘worked magnificently’, carrying on without any awareness of the change between day and night, not one member ‘showed any nervousness’.Footnote 84 ‘[S]leep was out of the question, and one never felt it advisable to undress’, concluded Elizabeth Courtauld. They worked all night, ‘hard at it and working under difficulties. Terrible cases came in’: ‘Between 10.30 and 3.30 or 4am we had to amputate 6 thighs and 1 leg, mostly by the light of bits of candle, held by the orderlies’. Courtauld gave anaesthetic ‘more or less in the dark at my end of the patient’.Footnote 85 After her return from Salonika, Edith Stoney went to France and joined the Villers-Cotterets team. In June, she wrote to the Committee about the frantic packing, unpacking and repacking of valuable X-ray equipment, when orders were given more than once to evacuate: no mean feat, given the circumstances. Staff had to ensure patients, but also dressings, bandages, drugs, splints, and, of course, X-ray apparatus, made the journey back to Royaumont. A false alarm about evacuation meant the replacement of electric wiring and the reinstallation of necessary equipment for the many injured who were pouring into the hospital. Florence Anderson, once orderly and now masseuse and radiographer's assistant, exclaimed that the dismantling and then reconstruction of the X-ray installation was a ‘tour de force’, which ran successfully all night.Footnote 86 Less romantically than Collum implied in her Blackwood's article, Stoney noted that, as well as candles, she was responsible for the lighting of a 50-candlepower electric lamp, which was carefully shaded by being stuck in a cocoa tin. As they had already evacuated the electrician, Stoney had to assist in working the engine for the X-rays. The surgeons operated all night; Stoney went to bed at 4 a.m. Three hours later, operations were still being performed. Upon the final evacuation warning, the staff left, with as much as they could transport. All the while, they remained under heavy bombardment. When they made return visits to Villers-Cotterets, to collect equipment, it was noticed that personal items had been looted, boxes broken into, X-ray plates spoilt and apparatus broken or lost. The loss of their own clothes and effects brought home after the fact the horrors of what they had gone through. Courtauld was frustrated at the loss of her rubber bath, others their books and ‘knic-knacs’. The former had even wanted to dig up and burn vegetables grown by the staff to avoid the ‘Hun’ profiting from them, but only managed to pick a bunch of radishes, which then had to be abandoned.Footnote 87 Yet, within 24 hours of recovery, the reclaimed Gaiffe table was running at Royaumont and 600 examinations were made on it by Stoney herself.Footnote 88 As the number of casualties was so enormous, the bravery of the X-ray team in returning to Villers-Cotterets to collect what was left paid dividends when they were able to mobilise the reclaimed equipment to assist at Royaumont during its busiest days. To use Collum's analogy, the events of May and June 1918 proved that the rope could be partially unravelled, but that this did not affect its overall strength. The experiment was a success.

Not every week was as exciting. More variegated detail can be obtained from private letters or official documents sent back to Britain. It was apparent that the Corsican Unit of the SWH undertook ‘Very few major operations’, for example, while the GNU in Salonika was initially bombarded with medical cases, rather than wounded, which led McIlroy to look forward to an advance and the resulting ‘plenty of work to do in surgery again’.Footnote 89 Also in Salonika, new recruit Verney complained on Armistice Day that she found ‘the work unutterably slack and time on my hands’, but with ‘champagne and aste spumante for dinner’, she exclaimed with glee: ‘your daughter is not what she was!’.Footnote 90 Royaumont posted weekly reports to the Committee in Edinburgh, for example, although precise statistics were not often included. In April 1915, however, a very detailed assessment of the situation since January was submitted and allows an insight into how the hospital functioned in its first few months. It is quoted in full to illustrate the types of cases received by the institution.

| Patients admitted: Jan 13-Feb 13 | 74 | ||

| Feb 13-March 13 | 77 | ||

| Operations performed: Jan 13-Feb 13 | 11 | ||

| Feb 13-March 13 | 36 | ||

| Deaths: Jan 13-Feb 13 | 1 | ||

| Feb 13-March 13 | 1 | ||

| Patients admitted week ending March 20 | 67 | ||

| March 27 | 45 | ||

| Operations performed week ending March 20 | 17 | ||

| March 27 | 25 | ||

| Patients in hospital week ending March 20 | 135 | ||

| March 27 | 158 | ||

| X Ray examinations. Jan 13-Feb 13 | 27 | ||

| Feb 13-March 13 | 44 | ||

| week ending March 20 | 41 | ||

| week ending March 27 | 53 | ||

| Photographs taken Jan 13-March 27 | 119 | ||

| Analysis of Cases: Jan 13-March 27 | |||

| Surgical | Medical | ||

| Shrapnel Wounds | 62 | Pleurisy, Bronchitis, Pneumonia | 36 |

| Bullet Wounds | 32 | Septic Throats | 4 |

| Joint Injuries | 17 | Rheumatism and Sciatica | 21 |

| Fractures | 14 | Typhoid | 5 |

| Contusions | 10 | Gastritis | 5 |

| Septic Wounds | 10 | Skin Affections | 10 |

| Appendicitis | 7 | Commotio Cerebri | 5 |

| Gland Afflictions | 6 | Nephritis | 2 |

| Haemorrhoids | 5 | Jaundice | 3Footnote 91 |

| Grenade Wounds | 5 | ||

| Burns | 3 | ||

| Frozen Feet | 3 | ||

| Typhoid abscess | 1 | ||

| Haemorrhage Colitis | 1 | ||

This rare case analysis was striking because of the number of operations performed. Between January and March 89 procedures were carried out; the figures more than doubled over the three months. In her letter accompanying the report, Ivens exclaimed at the ‘enormous increase’ of work over the past five weeks, but, in comparison with the type of press coverage women surgeons were receiving, these numbers were small. Patients were starting to come directly to the hospital from the front because of the facilities provided by the rail network and some were now not passing through the distribution centre at Creil.Footnote 92 Yet, while the 200 beds were almost full at times, they were not always occupied by surgical patients.

The mixture of medical and surgical cases was especially interesting, given the focus on women's surgical skills and the designation of the hospitals as centres of pure surgery. Overall, for example, two-thirds (66.3 per cent) of the total number of patients between January 1915 and February 1919 at Royaumont and Villers-Cotterets, both military and civilian, were operated upon, but that left a third who were medical patients.Footnote 93 There were 176 surgical cases over the three-month period between January and March 1915, but a corresponding 91 medical cases, ensuring 65.9 per cent of patients, rather than the much higher numbers suggested by supporters, were designated surgical. Of these, at least 19 had conditions not associated with warfare. In amongst evident war wounds caused by bullets, grenades or shrapnel were the more quotidian appendicitis, gland afflictions, colitis, or even more prosaic haemorrhoids. Three had frozen feet, the sort of condition that Harrison remarked attracted little interest from medical historians of the conflict. As the report revealed, exciting and new surgical challenges were not the only ones experienced by the surgeon at the front. In an interview from 1977, Verney remarked succinctly that the GNU in Salonika ‘had an awful lot of work which you wouldn't see in England. It was rather interesting in that way and then we had the ordinary well, casual appendix and so on’.Footnote 94 Often such all-too-familiar ailments presented themselves for treatment, as well as medical complaints associated with lung problems, aching joints and the frustrating inconveniences associated with the immobility of trench fighting.Footnote 95 In fact, it was not until October 1915 that the hospital experienced its first amputations. As Loudon noted, one day had seen two arm amputations, one right, one left, on different men. These were the ‘first’, she remarked, as they ‘don't count fingers’.Footnote 96 One more had been added by 19 October, with several ‘on the verge’.Footnote 97 This was ‘a poor boy of 21 who has had to lose his leg’.Footnote 98 The thousandth patient was admitted in August 1915. ‘Sergeant Le Begnee’ [sic] was suffering from appendicitis and appeared not to have come straight from the trenches, even though he had fought at some point in the war.Footnote 99 Initially, complained Ivens, Royaumont was not sent many ‘big cases’. The work was, therefore, only occasionally ‘quite interesting’.Footnote 100 Many seriously wounded men were sent elsewhere, as they were expected to take longer to recover than the hospital could support. By 1919, it was concluded that the GNU, which had moved three times since its original establishment in Troyes, had dealt with 6,497 patients: 2,733 of whom were surgical; 3,764 medical. Therefore, 42.1 per cent of the work carried out by the unit was surgery, 57.9 per cent medicine.Footnote 101 Endemic diseases, such as malaria and dysentery, dominated in the summer of 1916 when the Unit was in Salonika, and it was only in the spring of 1917 that surgical work became the main focus of the hospital.Footnote 102 As the women were to discover, not every case demanded special knowledge; frequently patients were admitted for the most routine of procedures which could be encountered in a civilian hospital at home. Surgical ‘interest’ was not always piqued by the cases arriving daily.

At times, indeed, institutions near the front must have been confronted with strangely familiar conditions. For Royaumont, it was the expectation of medical and surgical care from local citizens which took them by surprise. During the lulls between attacks, the hospital saw 1,537 civilians for consultations, while general practitioners of nearby villages sent in a further 537 patients for operation. The total number of patients at Royaumont and Villers-Cotterets during the four-year period during which the SHW occupied them was 10,861 and operations were carried out 7,204 times.Footnote 103 French civilians counted for 25 of Royaumont's deaths, which, given that there were only 159 deceased military personnel between 1915 and 1919 at the hospital, pointed to the severity of local cases. Courtauld noted that by December 1918, the ‘civils’ were being admitted once more and were, consequently, ‘flocking in to take advantage of treatment just before we close’.Footnote 104 Civilian care was more popular in British hospitals, as Courtauld noted in her letter, after the war had finished, but Royaumont had been involved with the local populace throughout its existence. When Verney arrived in Belgrade after the conflict had ended, she worked almost entirely with civilians. As well as prisoners of war, they were caring for a ‘mass’ of children sent in by the Save the Children Fund, and had also contributed to the building of a well for local water.Footnote 105 Although every surgical case in wartime or novel surroundings was an experience, some patients began to look more than a little familiar.

The surrounding population evidently took advantage of a well-equipped hospital in their midst and the women surgeons found themselves operating upon their own sex at Royaumont. In a letter of March 1915 to Inglis, Ivens expressed the ‘embarrassment’ felt at their outpatient facilities. While they did not operate upon women at Royaumont, they carried out procedures at the nearby Beaumont Hospital when cases appeared on their doorstep. At the Beaumont, they had received two cases and a third, who had a bad malignant condition, could not be persuaded to leave Royaumont, so they had secreted her in a little room far away from the men. Another woman, who required operative treatment, had mysteriously ‘appeared’ that afternoon.Footnote 106 The situation was so unexpected that Ivens had been compelled to send for throat and gynaecological instruments: ‘It was the last thing which I thought would be necessary!’ She also requested a Paquelin cautery, frequently utilised for gynaecological malignancies, as they were clearly receiving a ‘lot of’ conditions requiring cauterisation. As they had already borrowed and broken one, at present, she added ironically, we have nothing available but the ‘kitchen poker’.Footnote 107 The frustration of having to deal with cases she thought were left behind in Britain was obvious in this surgeon-to-surgeon letter. At this point, additionally, there were many surgeons and not enough to keep them busy. In a convoluted sentence, Ivens sighed: ‘[we] have really not nearly as much as they could do if the need arose’. A feeling of not being wanted for ‘serious’ surgery pervaded this letter, as well as the boredom of waiting around for action on the battlefield to intensify. Although this was early on in the hospital's existence and the locals were only mentioned when there was a lull, they evidently utilised Royaumont's facilities and the surgical expertise on offer into the final year of the war. While they were only taken in when they needed operative assistance and sent out as soon as possible, in a letter to Miss Kemp of February 1918, Ivens made reference to 16 women patients that day. Around half of them were suffering from appendicitis; several had malignancies. By this point, however, Ivens’ attitude to the female patients had changed significantly. Now she remarked upon their ‘extraordinary gratitude’ and the staff's corresponding feeling that it was ‘very gratifying to be appreciated’.Footnote 108 Although local women comprised no more than 5 per cent of the now 300-bed hospital, they formed a consistent hospital population over the time Royaumont was open. So much so that Ivens wondered what the civilians would do without their assistance when they closed at the end of the war. Recognition and thankfulness also came from the authorities of the small towns, whose inhabitants received treatment from the women surgeons.Footnote 109 The constant presence of female patients must have ensured that their surgeons could not forget either past or future.

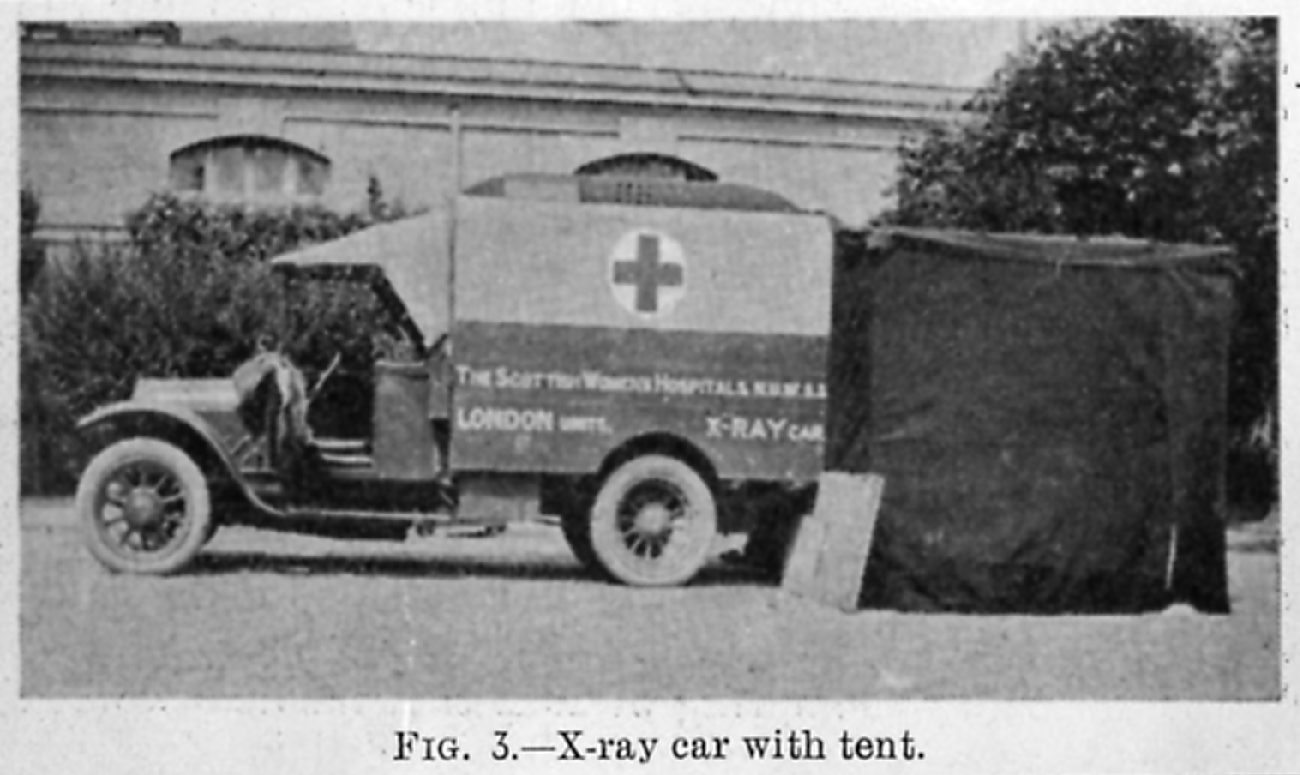

‘Appreciation’ at being necessary to others outside their institutions was also apparent from correspondence. Female expertise in X-ray work was especially sought after by nearby hospitals, who possessed neither their own specialists nor enough suitable equipment to carry out skilled exposures. Mobile X-ray vans in France had been popularised by Marie CurieFootnote 110 and the SWH had been keen to invest in such facilities (Illustration 4.1). Agnes Savill, the radiologist at Royaumont, was an early beneficiary of a fully equipped car, and her knowledge and apparatus was in demand by other institutions in the vicinity. In October 1915, for example, her services were required at a hospital a few miles away, which had only one ambulance and no X-ray equipment. Instead of sending the patients to Royaumont to be X-rayed, which had been the usual occurrence,Footnote 111 a mobile unit could go directly to the injured to prevent them from suffering further disruption to their recovery. Sixteen cases were photographed ‘on the spot’ by Savill. ‘Naturally’, noted the administrator, Cicely Hamilton, ‘the car greatly extends our usefulness in that direction’.Footnote 112 Common Cause remarked similarly on the value of this ‘Travelling’ vehicle.Footnote 113 Evidently, however, its exceptional nature was overpraised in the same publication. ‘We were rather amused’, remarked Loudon wryly ‘to see the fairy tales in the Common Cause re the X Ray Car’.Footnote 114 Indeed, the periodical claimed that the French military authorities had said that ‘the car is the finest X-ray car ever used in France’ and will enable ‘such work to be done much nearer the lines than has hitherto been possible’.Footnote 115 It was, by the time Loudon wrote the letter, less hyperbolically going to ‘a hospital to see some patients (if one may use the expression)’.Footnote 116 Usefulness was less apparent in Greece, however, when the promised car was delayed and then proved ineffective on local terrain. Publicly funded organisations such as the SWH directed their money towards the purchase of such recent technological innovations, which could then be displayed for supporters to admire the utility of their generosity. Such showiness was not popular with Edith Stoney, the radiographer for the GNU in Salonika, who baulked at the tours made in Scotland with the newly purchased X-ray car in the autumn of 1916. The proceeds of a flag day held in Glasgow for the memory of dead nurse Edith Cavell were put towards the purchase and equipment of the car.Footnote 117 As it was the first of its kind fitted up in Scotland, great pride in the workmanship and a desire to show it off to the public led to its display. The apparatus was also utilised at Glasgow Royal Infirmary, where sterling work was done on 90 cases a day.Footnote 118 This ‘local show’ astounded Stoney, who suggested no one could admire the car itself, with its polished fittings; the actual photographs based on ‘real use’ would be the ‘best guarantee’ of its proper deployment.Footnote 119 Keeping it in Scotland was certainly not helping the war effort, she fumed.

Illustration 4.1 X-Ray Car with Tent, clearly indicated as belonging to the SWH, British Medicine in the War 1914–1917 (London: British Medical Association, 1917), Wellcome Library, London.

Although this purchase eventually proved ineffectual,Footnote 120 Stoney was much in demand in Gevgeli and then in Salonika, in similar fashion to Savill in France. ‘I have quite a reputation around the other hospitals here for my photos!’, she exclaimed with pride to her sister.Footnote 121 As she had the only complete tent in the area, others having lost theirs on the journey to Serbia, this allowed her to run X-rays, which had to be strictly rationed for the Unit's own patients. X-ray apparatus was a rarity in Serbia,Footnote 122 so Stoney's equipment fascinated. An inspection by the French Medical General from Salonika made ‘his best felicitations on [her] photos, and shook [her] warmly by the hand’, in anticipation of the good work to come when the Unit reached Greece.Footnote 123 When that happened, uncertainty about the course of the war for the Allies in Salonika meant that some hospitals had not felt secure enough to establish their X-ray units. Or, as Stoney put it, ‘some cannot put them up, and some do not take very good photos when up’.Footnote 124 As a consequence, she had received a number of requests from various quarters for assistance, including a British hospital ship. Stoney had recently examined eight French soldiers from other hospitals, four British soldiers and three British naval officers; two of the British men were doctors. Appreciation by colleagues and patients alike was not reflected in the coverage of Stoney's success at home. Her evident frustration at the lack of publicity afforded the GNU since it had left France was very clear in the May 1916 Common Cause article about their experience at Gevgeli. This piece was written by one ‘F.A.S.’, evidently Edith Stoney's sister Florence. It opened with an admonition that ‘very little has appeared’ in the press about the voyage of the Unit to the East and stressed that the staff had been ‘kept so busy that they have had little time to write’.Footnote 125 The focus of the article was on the X-Ray department and the skill of its head. Despite the danger of setting up in a very small room, Edith Stoney's expediency in purchasing a petrol engine in Paris ensured that even in an ‘out-of-the-way’ Serbian village location the X-ray Department was up and running from the outset. When the hospital was ready, the first rush came for Stoney; in two days, she received four chest cases, two head wounds, two abdominal, 11 leg and three arm injuries. Stoney's accuracy in localising, depth and position, was particularly valued, as her assessment could be utilised by the surgeons to remove bullets precisely from wounds. Such precision was also necessary in judging whether it was wiser or more expedient not to operate. The successful running of X-ray equipment contributed to the hospital's excellent reputation and led to Stoney being in demand with other hospitals who sought out her expertise.

This article also made clear how primitive the living and working conditions were for the SWH Units, especially those in Eastern Europe. It illustrated the very personal contribution members of the whole team made to the smooth running of the operating theatres they established. If her sister had not purchased the engine, reminded Florence Stoney, the hospital would be without an X-ray department, but, even more basically, lacking in electric light. Edith Stoney's Cambridge physics education came in handy more than once during her service with the SWH. While fundraising at home was directed towards obtaining state-of-the-art technological apparatus, such as the X-ray car, more fundamental resources, such as heat and light, were required by those operating abroad. On the first night at Gevgeli, indeed, Stoney ‘lighted the whole hospital’ with electricity from her recently procured engine. Now, ‘instead of spending the long winter by the dim light of candles, they had the one luxury of good illumination’.Footnote 126 Electricity made the light source constant and more reliable, allowing manipulation in the operating theatre to scrutinise particular areas of the body.Footnote 127 Stoney's letters were full of the ways in which the women adapted to the difficulties of the surroundings and the circumstances in which they found themselves. The fact that she owned a great deal of her X-ray equipment belied the insistence of the original SWH appeal leaflet on its purchase before leaving of the ‘most modern surgical appliances, dressings and drugs’; X-ray apparatus being ‘an indispensable adjunct to modern surgery’.Footnote 128 Radiology was still a developing, semi-professional surgical ‘adjunct’. Its experimental nature was encapsulated by the personal investment in equipment by those wealthy enough to have a try; some owned the apparatus utilised in institutions, for example.Footnote 129 It was precisely this ownership of vital resources and personal investment in equipment which led to dissent between Edith Stoney and the Committee at home. Alongside the falling out over the X-ray car, Stoney and the Committee were engaged in a longstanding battle over her engine, which was used to power the radiological equipment. Misunderstandings over its usage led to a stalemate, whereby the Committee thought that Stoney had agreed to sell them the engine and the radiographer had insisted that she had not made this promise.Footnote 130 Part of the problem was due to the fact that it was ‘an absolute necessity’ for the GNU, as a moving surgical corps, to keep all the vital apparatus for which it had won its good name. But, correspondingly, as engine, coils and Stoney's artisan assistant were to be left behind in Salonika upon her resignation, the Committee would effectively remove her usefulness, as her own apparatus was fundamental both to the furthering of her career and her efficiency as a specialist war worker.Footnote 131 With an X-ray specialist came equipment and vice versa; one could not exist without the other. This complex situation, where private property became one foundation stone of a unit's success, revealed the tension which existed between individual member and the wider surgical team under desperate conditions. For Stoney, her value could not be separated from the control of her X-ray apparatus. The Committee, however, were untroubled about separating technology from operator, and took a different perspective, choosing to retain the former to keep the unit going.

As Stoney's problems with her own resources illustrated, equipment led to dispute. The Edinburgh Committee were ever alert to the cost of what could appear extraneous from a distance.Footnote 132 So many letters and telegrams were requests for more. Four months into Royaumont's activities, Ivens enclosed a list ‘which had nothing to do with equipment’, but was added solely because of ‘wear and tear’. Without surgical necessities arriving, such as gauze, dressings, linen, wool, and needles, work was at a standstill. It was cheaper to order material from British sources, as French prices were increasing swiftly, and every day ‘runs away with a large quantity of material’.Footnote 133 In October 1915, Ivens responded to Beatrice Russell's letter about the cost of gloves. As Ivens noted, gloves were ‘patched’ and nurses were ‘as economical as possible in their use’. Despite their best intentions, however, tetanus had been found in at least five patients: ‘the frightful risk of communicating these appalling germs either from one patient to another or to nurses and orderlies is always with us’.Footnote 134 The surgeons required rubber gloves and dismissed any attempts by the Committee to order cotton. Thick and impermeable material was fundamental to prevent sepsis.Footnote 135 Despite every aseptic precaution, ‘appalling germs’ infected both patient and surgeon. ‘Even with the greatest care’, warned Ivens, ‘two doctors have sore fingers this week’.Footnote 136 Collum's X-ray burns were not the only injuries she suffered; they were supplemented with a septic finger in August 1915.Footnote 137 The heroic aspect of operation upon operation against the terrors of wartime was tempered in reality by the aching, fatigued and, most worryingly, diseased fingers. Shortages of vital equipment and physical suffering led to a united front of institution against administration, practicality over financial concerns.

The holding together of the surgical team was not always in evidence, however. In her Blackwood's article of 1918, Collum presented an intriguing image of the democracy operating at Royaumont:

During the first year's service we were practically without rules of any description. We were roughly divided into doctors, nurses, and orderlies, but the lines of demarcation were fluid and hardly existed outside working hours. The doctors made no attempt in the early days to keep up their position as officers, except in the wards and the operating theatre and so on. From the point of view of discipline it may have been a mistake, but it produced a hospital organisation that is surely unique.Footnote 138

Such an idyllic atmosphere of equality in leisure time evidently spilled over into the working life of the institution. Even though Collum demarcated the professional spaces of the operating theatre and the wards from areas of rest and relaxation, the lines between the team members, lay and medical, were fluid rather than hierarchical. The overriding impression of Collum's assessment was harmony. Louise McIlroy's unit in Salonika was criticised by its own administrator, Miss Beauchamp, for lax discipline. ‘Petty details, such [as] my riding, entertaining British Admirals, giving permission for the staff to have their friends in their recreation tents, were brought up as evidence against me’. However, she fumed, ‘the work is just as good as ever’.Footnote 139 Enjoyable leisure activities and hard graft were not incompatible for McIlroy. However, SWH correspondence and papers could disagree. Dr Dorothy Cochrane Logan had the unusual distinction of being the only member of medical or surgical staff to be dismissed from Royaumont or, indeed, from any unit of the SWH.Footnote 140 From the letters of Frances Ivens and the minutes of the Personnel Committee, it is possible to piece together the reasons for her dismissal. Ironically, given Collum's reading of Royaumont's politics, Logan was removed from the hospital precisely because she refused to accept hierarchical standings.

In an undated letter, received by the Edinburgh Committee on 20 July 1918, Ivens told her side of the tale: ‘I did not accept Miss Logan's resignation for I was not aware that she had resigned’. In fact, she continued, ‘I dismissed her because she refused to give an anaesthetic when asked to do so’. Such ill-discipline and questioning of orders from the Chief Surgeon relieved Royaumont of someone who ‘did not overwork’.Footnote 141 Evidently Logan felt differently, as ‘poisonous remarks about sweating’ had been enough to cause the London Committee to visit their Scottish counterparts. ‘Any suggestion of disunion created such a bad impression’, concluded Ivens. She was very glad to have Logan out of the hospital.Footnote 142 ‘Sweating’ had very particular connotations in first two decades of the twentieth century, as it had in the nineteenth, but would have been a cruel blow when directed at professional members of a surgical team. Low pay, poor conditions, long hours, and often specifically female, working-class and immigrant oppression were composite factors for the ‘sweated’ toiler.Footnote 143 Indeed, in the words of social investigator Clementina Black, sweating was a ‘morass exhaling a miasma that poisoned the healthy elements of industry’.Footnote 144 Sweating's link with the tailoring trade, one requiring accurate stitching, like surgery, also made Logan's comparison contextually fascinating.Footnote 145 For Logan, the regime at Royaumont was akin to nightmarish, exploitative working conditions; for Ivens, her junior was lazy and unruly. Whether Logan refused to give an anaesthetic because she was exhausted and overworked, concerned about doing so, or because she felt that it was beneath her is not clear.Footnote 146 The fluidity of relationships at Royaumont, however, was neither as free from hierarchy nor as nonchalantly regarded as Collum would have her readers believe.

Tensions between Louise McIlroy and Edith Stoney also tell another story from that publicised by Collum. The latter saw herself as the saviour of the GNU: ‘I saved this corps from utter inefficiency as a surgical corps in Serbia (there was no main electricity at Guevgueli)’, she retorted, ‘by buying an engine with my own money’.Footnote 147 In spite of writing a testimonial for Stoney which stressed her co-operative stance within the team, this was not how McIlroy saw her radiographer in personal correspondence.Footnote 148 McIlroy felt that Stoney had lost interest once hostilities had ceased, which had led to the drying up of surgical, and, consequently radiographic, work. Now electrical treatment dominated Stoney's X-ray agenda rather than the localisation of bullets and shrapnel upon which she prided herself. There was no ‘friction’ in the Unit, however, claimed McIlroy.Footnote 149 Stoney offered another assessment of the situation. From the outset, her letters expressed concern over her non-medical background, even though her Cambridge education impressed her colleagues. While assistance was forthcoming from the surgeons, Stoney could not interest them enough to ‘work the apparatus with the patients’, nor did she feel happy about her ‘lack of anatomy’, which ‘makes me very lame’, she noted sadly.Footnote 150 Although X-rays showed ‘the real surgical work of the hospital’, Stoney evidently felt her lack of medical expertise disabling.Footnote 151 Those who were ‘not medical’, she commented later in 1918, were ‘so eaten up these days with the dread of not getting useful enough work’ that their desire to help was visceral.Footnote 152 She also made exactly the same point as McIlroy about the hierarchy of interest in the GNU, but turned it back on her colleagues. The surgeons themselves, remarked Stoney, inevitably found purely surgical cases more ‘“interesting”’ than the fight against disease, which dominated current work in Salonika.Footnote 153 Undoubtedly, however, McIlroy and Stoney respected each other's qualities. The former praised her radiographer's exceptional photographic and localisation skills, her minute and thorough grasp of the physical sciences rendering her far more useful than a medical graduate could have been.Footnote 154 ‘I have never failed to find pieces of projectiles in wounds which have been photographed by Miss Stoney's stereoscopic process’, McIlroy asserted.Footnote 155 Stoney, meanwhile, looked admiringly at her Chief's surgical abilities: ‘Dr McIlroy is a very beautiful operator – in no case localised by me has she failed to find the bullet from my localising.’Footnote 156 It is remarkable how both women praised each other through the prism of their own specialty. Despite their many differences, confidence in their own ways of doing things united Stoney and McIlroy.

Working Together

Whether the X-ray was fundamental to wartime surgery depended on who was asked. For Edith Stoney, it was questionable that a unit could be a surgical one if it did not have X-ray apparatus: ‘The front station from Ostrovo Unit has been left without any X rays at all through the worst of the awful Serbian fighting tho’ a supposed surgical unit.’Footnote 157 The British were slow to adopt the technology, as Bowlby and Wallace noted in their 1917 analysis:

At the beginning of the war x rays were not supplied at the front, but, coincidentally with the development of operating work in the casualty clearing stations, the need of these became apparent. […] [N]ot only have x rays been of great use in guiding the operator, but in many of the abdominal wounds where the missile has been retained they have been of the greatest service to the surgeon in deciding whether or no operation should be done at all. In many other cases, such as some of the wounds of the head or of the knee-joint, it has been found better not to undertake an operation without a preliminary x-ray examination, so that in the present stage of development of surgery at the front the x-ray plant has become essential for the work of the casualty clearing stations.Footnote 158

Even within this one comment it is possible to see how X-rays were initially considered unnecessary, then necessary, but as an accessory to surgery. Bowlby and Wallace discussed radiology as an associate, an advisor or a guide to the surgeon rather than a replacement for surgical understanding. The surgeon should and indeed did retain control over diagnostic decisions. As Alexander McDonald has remarked, there was considerable variation in the extent to which X-ray equipment was used in France and Belgium.Footnote 159 In addition to any scepticism about the value of the technology, Edith Stoney's correspondence also reflected on the difficulties of running apparatus in parts of Europe where even the means to run basic electricity might be scanty. The accounts of the retreat from Villers-Cotterets in the summer of 1918 revealed the practical difficulties involved in the installation of X-ray machinery, as well as the fragility of the easily broken plates and tubes. Disputes over the status of a layperson running equipment and their place in the surgical team could also lead to divisions between radiographic and surgical operators. There were, however, three particular instances where surgery and radiography worked in tandem during the Great War: localising bullets or shrapnel; therapeutic treatment for the wounded; and diagnosing gas gangrene.

The localisation of foreign bodies was vital to surgical success. By accurately pinpointing a bullet or a piece of shrapnel an X-ray could provide the surgeon with a precise location for surgery. As Bowlby and Wallace acknowledged, it might also indicate the advisability or otherwise of operation. If an object was too dangerous to extract, an image of its position could save the patient's life as equally as a surgical procedure would if it was removable. Similarly, those men who survived the war with shrapnel embedded within them, as we shall see in the next chapter, required further surgical care when internal damage resulted.Footnote 160 This did occur in wartime, too, either where the patient had not been X-rayed in the first place or where the surgeon had failed to remove all the debris. Stoney remarked upon four head cases seen in Salonika in 1917. One had been wounded over two months before and had become blind in one eye; the other was temporarily sightless. The blind eye was removed, but the ‘good’ eye, upon localisation, was found to have metal in the orbit, causing the loss of sight. There were also two cases with metal in their lungs. One was ‘awfully thin’, but had benefited from accurate localisation of the detritus which had then been removed by McIlroy. The other had an inch of metal in his face and a piece of shell in the lungs, again identified by X-ray.Footnote 161 For abdominal cases, localisation was necessary to ‘distinguish between the different organs in which the foreign body may lie’.Footnote 162 Given initial reluctance during the Great War to operate on abdominal cases, an accurate image could determine whether the patient's condition was hopeless or salvageable. Stoney commented that she had never localised a foreign body which the surgeon had not then gone on to find, so the skill was in great demand under the exigencies of wartime surgery.Footnote 163 In her 1917 book Women of the War, Barbara McLaren designated such surgical assistance ‘invaluable’.Footnote 164 Confidence in Stoney's technique was such that during her later post at Royaumont, her value was acknowledged when the ‘surgeons refused to operate on wished me to overlook all localisations’.Footnote 165 The crossing out here is intriguing in relation to the place of the non-medical radiographer within the surgical team. In contradistinction to Bowlby and Wallace's assessment of the usefulness of the X-ray, surgery did not take place at Royaumont without radiographic confirmation of surgical diagnosis.