1 From abbey to cathedral and court: music under the Merovingian, Carolingian and Capetian kings in France until Louis IX

Music for much of the Middle Ages is mostly treated as a trans-national repertoire, except in the area of vernacular song. Nevertheless, many of the most important documented developments in medieval music took place in what is now France. Certainly, if the concept of ‘France’ existed at all for most of the Middle Ages, it did not encompass anything like the modern hexagone: French kings (or, more properly, ‘kings of the French’) usually did not directly control all the territories they nominally ruled, and southern territories in particular sought to maintain their political and cultural distinctiveness. Still, it can be useful to consider medieval music in relation to other developments in French culture. From the intersections of chant and politics in the Carolingian era, to the flowerings of music and Gothic architecture, to the growth of vernacular song in the context of courtly society, music participated in broader intellectual and institutional conversations. While those conversations did not generally have truly national goals, they took place within what is now France, among people who often considered themselves to be, on some level, French.

The Gallican rite of Merovingian France (c. 500–751)

As the Roman empire gradually disintegrated, its authority was largely replaced by local leaders and institutions. The Christian church took up some of the empire’s unifying functions, but it too was geographically fractured as communication became more difficult. A distinct Gallican liturgy can be seen even before the conversion of Clovis, the first of the Merovingian kings, around the year 500. In light of future events, it is interesting to note that the earliest document attesting to Gallican liturgy is a letter by Pope Innocent I, dated 416, requesting that the churches of Gaul follow the Roman rite, but surviving texts attest to the persistence of the local liturgy.1

While the existence of a Gallican rite is clear enough, what it sounded like is harder to determine.2 No musical sources survive, since Gregorian chant effectively suppressed Gallican melodies before the advent of notation in the ninth century. Some texts and descriptions give hints, and traces may remain within the Gregorian liturgy, but teasing out the details is difficult, and scholars do not always agree on methods or results.3 What evidence survives suggests less a single coherent rite than a heterogeneous body of materials whose specific contents may vary from place to place, perhaps sharing a basic liturgical structure but using different readings or prayers. Though it largely disappeared, Gallican chant provided the Frankish roots onto which the Roman rite was grafted to create what we know as Gregorian chant. This new hybrid was inextricably linked to Carolingian reforms.

The Carolingian renaissance and the creation of ‘Gregorian’ chant (751–c. 850)

While the effective power of the Merovingian kings declined over the seventh century, that of the mayors of the palace who ruled in the king’s name increased, until in 751 Pépin III (the Short, d. 768) definitively took the royal title himself. He sought to enhance his new royal status in part by a renewed Frankish alliance with Rome.4Pope Stephen II travelled to Francia, making the first trip of any pope north of the Alps, and in 754, at the royal abbey of Saint-Denis, he anointed Pépin and his sons. By the end of the century Pépin’s son Charles, later known as Charlemagne (r. 768–814), was the most important ruler in the West, controlling much of what is now France, Germany and Italy, and he was crowned by the pope in Rome on Christmas Day 800.5

The Carolingians took their role as protectors of the church seriously, seeking to reform religious life through the better education of clerics.6 The cultural flowering that resulted, often called the Carolingian renaissance, built on both Merovingian and Gallo-Roman roots. Monastic and cathedral schools were created to foster basic Latinity, which could be passed by parish priests to the laity, and to provide further education in the liberal arts and theology. Both patristic texts and classical works by authors such as Cicero, Suetonius and Tacitus, largely neglected in Frankish lands for a couple of hundred years, were copied in the new script known as Carolingian minuscule, developed at the monastery of Corbie.7 Not only were older texts copied, but Carolingian masters wrote new commentaries on both sacred and secular texts, as well as poetry and treatises on a wide variety of subjects. Through all this can be seen not only a concern for proper doctrine, but also an increased emphasis on the written word.

The church was also the primary beneficiary of many developments in the visual sphere.8 Liturgical manuscripts and other books were often highly decorated, both on the page and in their bindings, which may include ivory carvings or jewels. New churches, cathedrals and monasteries were built and supplied with elaborate altar furnishings, such as chalices and reliquaries. Few examples survive of textiles and paintings, but ample evidence exists of their use. Charlemagne’s court chapel at Aachen is a superlative example of visual splendour in the service of both religion and royal power.

The importing of the Roman liturgy and its chant into the Frankish royal domain was an important part of the Carolingian reforming agenda. Roman liturgical books and singers circulated in Francia as early as the 760s. The effort to displace the existing Gallican liturgy in favour of the Roman, however, was never as successful as the Carolingian rulers might have liked. The number of documents that mandate the Roman use suggests a general lack of cooperation on the part of the Franks, and the surviving books attest to far greater diversity in practice than Carolingian statements would suggest.9 Moreover, melodic differences between the earliest sources of Gregorian chant and later Roman manuscripts show that Gregorian chant is in reality a hybrid, created through the interaction of the rite brought from Rome and Frankish singers. Susan Rankin compares Gregorian and Roman versions of the introit Ad te levavi, arguing that the Gregorian version shows a Carolingian concern for ‘reading’ its text in terms of both sound and meaning to a greater degree than the Old Roman melody does.10 This fits within the Carolingian reforming ideas already seen. In any case, Gregorian chant eventually became more than just another local liturgy: it was transmitted across the Carolingian empire and beyond, and given a uniquely divine authority through its attachment to Gregory I (d. 604), Doctor of the Church, reforming pope and saint. The earliest surviving Frankish chant book, copied about 800, uses his name, and an antiphoner copied in the late tenth century provides what becomes a familiar image: Gregory (identifiable by monastic tonsure and saintly nimbus) receiving the chant by dictation from the Holy Spirit in the shape of a dove.11

The need to learn, understand and transmit this new body of liturgical song led to developments in notation and practical theory that are first attested in Frankish lands.12 The earliest surviving examples of notation come from the 840s, and the first fully notated chant books were copied at the end of the ninth century. A system of eight modes may have been in use as early as the late eighth century, as witnessed by a tonary, which classifies chant melodies according to mode, copied around 800 at the Frankish monastery of Saint-Riquier. Treatises explaining the modes and other aspects of chant theory appear in the ninth century; early examples include the Musica disciplina of Aurelian of Réôme, a Burgundian monk writing in the first half of the ninth century, and Hucbald (d. 930), a scholar and teacher from the royal abbey of Saint-Amand. In addition to chant books and treatises on practical theory, the earliest surviving copy of Boethius’s treatise on music, a fundamental source for the transmission of ancient Greek speculative theory to the Latin West, was copied in the first half of the ninth century, perhaps at Saint-Amand. The proper performance of chant, as aided by these tools, was an essential element in the education of clerics in Carolingian times and beyond.

Monastic culture under the later Carolingians and the early Capetians (c. 840–c. 1000)

By his death Charlemagne ruled much of Western Europe, but the later ninth century and the tenth century were marked by a return to local concerns, even while the authority of monarch and church were acknowledged. This attitude may be reflected in the flowering of musical creativity associated with individual religious institutions. Even as Gregorian chant took hold, new chants were created to enhance local saints’ cults, and new genres such as sequences and hymns allowed additions to established liturgies. Just as glosses became important in the second half of the ninth century as a way of commenting on texts, tropes were created to enhance existing chants, adding words and/or music to explain or expand upon the original.13 For instance, the notion of Jesus’ birth as the fulfilment of prophecy is underlined in this trope added to the Christmas introit found in a manuscript from Chartres (chant text underlined):

Polyphony, which will be discussed in the next chapter, likewise began as a way to enhance chant. While these practices can be found all over the Christian West, and some specific examples were transmitted widely, these additions to the central Gregorian repertoire were not standardised, but rather locally chosen, and often locally composed.

A major factor in the fracturing of the Carolingian empire was the common practice of dividing territory among all male heirs, rather than passing on a title only to the eldest. When Charlemagne’s son Louis the Pious died in 840, he left three sons. At the Treaty of Verdun in 843, they agreed on a division of the empire, and Charles the Bald, the youngest, inherited most of what is now France. The notion of a unified kingdom, however, was difficult to maintain as areas such as Brittany, Gascony, Burgundy and Aquitaine each held on to their own culture and traditions, and often their own laws and language. The Frankish kingdom was further challenged by Viking raids, which became more numerous from the 840s. In 845 the Vikings reached Paris, and from the 850s winter settlements can be found in the Seine valley. In 911, Charles the Bald’s grandson Charles the Simple ceded the area around Rouen, creating what eventually became the duchy of Normandy. A further crisis came in 888, when, for the first time since Pépin III became king in 751, there was effectively no adult Carolingian candidate to take the throne. After a century of conflict, Hugh Capet was elected king in 987. Under these circumstances, it is not surprising that Frankish culture was located more within individual religious institutions than at a royal court.

Monasteries were particularly important sites for the creation of new types of chant, and for the study and transmission of learning in general. From Alcuin, an English monk who was Charlemagne’s chief advisor and was named abbot of Saint-Martin of Tours in 796, to Suger (c. 1081–1151), abbot of Saint-Denis and confidant of Louis VI, and beyond, churchmen were key advisors to kings. New monasteries flourished even as royal power waned, and old ones were reformed and better endowed by local patrons, who requested in return prayers for their souls and those of their relatives. The best-known reform house was founded at Cluny in 910 by William the Pious, duc d’Aquitaine.15Cluny and its many daughter houses fostered proper celebration of the Office, reinforcing the idea that a monastery’s primary work is corporate prayer. Cluniac houses, like Benedictine monasteries, cathedrals, chapels in royal palaces and other churches, were adorned with new buildings and decorations to enhance the liturgy, which was preserved in notated and sometimes decorated manuscripts. Reforming impulses also led to the formation of new orders, most notably the Cistercians in the twelfth century, and the Franciscans and Dominicans in the thirteenth. These tended to take a more austere attitude towards chant, but they too copied liturgical books.

A number of Frankish abbeys can be associated with specific musical developments. The library of the Benedictine monastery of Saint-Gall, in modern Switzerland, still holds a number of the earliest surviving manuscripts containing musical notation, as well as standard works such as Boethius’s Consolatio philosophiae, classical authors such as Cicero, Virgil and Ovid, and vernacular texts.16Saint-Gall was also the home of major early creators of tropes and sequences such as Notker and Tuotilo, and an early example of the Quem quaeritis dialogue can be found there.17 Another early centre of both troping and Latin song, as well as liturgical drama and early polyphony, was the abbey of Saint-Martial in Limoges, founded in 848. The cultural flowering associated with this monastery in the late tenth century and eleventh century included an attempt to proclaim its namesake, a third-century bishop, as an apostle. This effort, spearheaded by Adémar de Chabannes, who wrote a new liturgy for Martial, was ultimately unsuccessful, but it did enhance the fame of the abbey and its value as a pilgrimage site.18

Saint-Denis, just outside Paris, had been a royal abbey since Merovingian times, and served as burial site of many French kings.19Pope Stephen II and his schola cantorum stayed there in 754, and demonstrations of the Roman chant and liturgy probably took place at the abbey at that time. New efforts to foster Denis’s cult in the ninth century led to the conflation of the third-century bishop of Paris with the fifth-century theologian Pseudo-Dionysius, in turn linked to Dionysius the Areopagite, a Greek disciple of Paul. The octave or one-week anniversary of this enhanced Denis’s feast was celebrated by a Mass with Greek Propers, the only one of its kind. In the twelfth century Abbot Suger, a close advisor and friend to Louis VI who had been educated at the abbey, built one of the earliest manifestations of the new Gothic architectural style there, replacing a Carolingian church. Aspects of the building reflect principles of Pseudo-Dionysian thought, and a mid-eleventh-century rhymed office for Denis emphasises ‘the light of divine wisdom’ as described in the theology of Pseudo-Dionysius.20Saint-Denis did not cultivate polyphony, as the cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris did, but its widespread practice of melismatic embellishments of chant can be seen as an attempt to move the singer or listener to the immaterial world, reflecting the belief that vocalisation without words approximated angelic speech and the Divine Voice.21

The Capetians and the age of cathedrals (987–c. 1300)

The focus on individual institutions as sites for musical developments continued under the early Capetians. While monasteries continued to serve an important role, urban cathedrals received increased attention, especially in the royal heartland still known as the Île-de-France. The election of Hugh Capet (r. 987–96) did not immediately lead to a resurgence of royal authority across the land, but it increased over the course of the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Primogeniture was still gaining acceptance and was not uncontested, so the early Capetians formally crowned and associated their eldest sons with them in their own lifetimes. This stability of succession allowed them time to build power. They also encouraged a new ideal of kingship: while coronation had long been seen as a sacrament, and the notion that the monarch is defender of the church had long roots, the early Capetians went a step further to build an image of the king as holy man. This can be seen in Helgaud of Fleury’s life of Robert the Pious (r. 996–1031), and in the widespread belief in the king’s touch, by which scrofula and other illnesses were said to be cured.22 The strongest manifestation of the sacralisation of kingship was the canonisation of Louis IX in 1297.

The early Capetians directly controlled only the area around Paris, but they gradually extended their geographic control westwards and southwards, and this culminated in the reclaiming of Normandy from the English kings in 1204. Philip Augustus (r. 1179–1223) further enhanced the position of Paris as his royal capital, building a new wall to protect recent growth. An economic recovery, beginning in the second half of the eleventh century, also benefited the French kings: the agricultural riches of northern France, including the royal domain, began to be realised, and trade between these areas and markets to the north, south and east was strengthened. Urban areas, especially Paris, became transportation hubs. Because cathedrals, unlike monasteries, tend to be located in cities, they benefited from this economic activity through the patronage of kings, nobles and townsfolk. New buildings were created in the new Gothic style, which encouraged liturgical and musical developments as well.

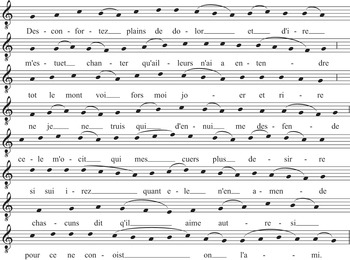

After the cathedral in Chartres burned in 1020, Bishop Fulbert (d. 1028) began work on the current building, which was also dedicated to the Virgin Mary. The Marian cult already active there was enhanced, with a new focus on the Nativity of the Virgin.23 The liturgy fashioned for this new celebration combined chants for Advent and Christmas from the traditional Gregorian repertoire with newly composed material, including three responsories attributed to Fulbert himself. The best-known of these outlines the lineage of Mary through the Jesse tree, which is spectacularly expressed in glass at the west end of the cathedral (see Example 1.1).24

The shoot of Jesse produced a rod, and the rod a flower; and now over the flower rests a nurturing spirit. [V.] The shoot is the virgin Genetrix of God, and the flower is her Son.

This melody begins by hovering around its final, D, dipping down to A at the word ‘Jesse’, in the process emphasising Jesse as the root of this genealogical tree. It then rises a little, centring on F with hints of G at the two appearances of the word virga (rod), showing how the branch lifts away from the root, but by moving downwards again links the branch to that root, as well as to the flower it produces. When the Spirit rests on that flower, it releases a luxurious melisma on the word almus (nurturing), which both rises to A, the highest note of the chant, and falls to the octave below before cadencing on the final. The effect is one of a gradual ascent, but one that is thoroughly grounded, like the Jesse tree itself. A similar process operates in the verse, which explains the image described in the respond: the melody rises to A on dei (God), then falls to flos (flower), showing how Christ ultimately serves as both culmination and source of the Jesse tree. Fulbert, or whoever composed the music, did not choose the perhaps obvious path and create a melody that rises inexorably from beginning to end through an authentic range (or that might even extend its range to show the scope of the tree’s ascent), but by using a plagal mode, with a relatively limited compass that envelops its final, he followed a different path, one that emphasises stability and rootedness.25

Example 1.1 Fulbert of Chartres, Stirps Jesse, responsory for the Nativity of the Virgin, respond only

Notre-Dame of Paris, at the heart of Philip Augustus’s capital city, is perhaps the best-known Gothic cathedral. It was renowned for its cultivation of polyphony, which will be discussed in the next chapter, but chant and other forms of monophonic song continued to be central to its liturgical life.26 Its canons had connections outside the cathedral, most notably at the abbey of Saint-Victor and the nascent university. Saint-Victor was a major centre of Augustinian reform in the twelfth century, balancing rejection of the world with serving the laity and seeking to create clerics who would teach ‘by word and example’.27 Its canons translated their reforming doctrine into liturgical song through a substantial group of sequences, many associated with Adam (d. 1146), who served as a canon and precentor of Notre-Dame before retiring to the abbey. Philip, chancellor of Notre-Dame from 1217 to 1236, wrote a number of conductus texts (for more on the conductus see below), though it is uncertain whether he wrote music, and indeed several are linked to melodies by Perotin, who will be discussed in the next chapter. Since Philip’s position brought him into contact with the university, it is not surprising that some of his conductus refer to student conflicts in the early thirteenth century.28

The growth of the University of Paris reflected a renewed concern for the proper education of clerics. Paris became the centre of a new cadre of clerks, associated with noble and royal households, educated at cathedral schools and universities and often remunerated in part through the acquisition of church benefices. University-trained clerics also enhanced the rosters of monasteries, cathedrals and other sacred foundations. This educated non-noble class, whether based at church or court or moving between the two, provided a number of the creators and performers of the written musical tradition, monophonic and polyphonic, in both Latin and the vernacular. Music as an abstract mathematical art was one of the seven liberal arts, but Joseph Dyer argues that it and the other disciplines in the quadrivium were effectively eliminated from the curriculum at the University of Paris by the mid-thirteenth century in favour of other subjects, especially Aristotelian logic.29 There is evidence, however, that university students had significant contact with practical music-making, through their early education, the liturgical practices of colleges and relationships with cathedral canons and singers of the Chapelle Royale. Peter Abelard and Peter of Blois are known to have written songs in Latin, and Abelard also composed hymns and six planctus. In perhaps the best-known witness to university-related music-making, the theorist known to us as Anonymous IV, probably a monk of St Albans in England, tells us about sacred music in Paris, especially Notre-Dame polyphony, on the basis of his experience as a university student.

Cathedrals were not the only witnesses to the Gothic style. After Louis IX (r. 1226–70) bought the Crown of Thorns from the Byzantine emperor in 1241, he built a chapel within the royal palace to house it. The Sainte-Chapelle is a masterpiece of colour in glass and paint that visibly links the French kings to those of the Old Testament and both to Christ the King.30 These connections were made in the liturgy for the chapel as well, perhaps most notably in the Offices created to celebrate Louis IX after canonisation:

The King of kings, laying out a kingly wedding feast for the king’s son, offers him, after the race in the stadium, the delights of heaven in glorious exchange. [V] In exchange for the kingdom of earthly things, Louis has the celestial kingdom as reward.31

In this responsory, Louis is explicitly linked to the New Testament parable, and both Christ (by analogue) and Louis are offered celestial kingship for their earthly work. The responsory is less melismatic than many examples, perhaps in part so that it can reflect the rhyming text.32 Its fourth-mode melody is restless, beginning with a leap from D to A and cadencing on various pitches before the extended melismas on glorioso commercio (glorious exchange, referring to Louis’s exchange of earthly rule for spiritual delights) close on E, as though finding at last in heaven the rest the saint could not find on earth.

Secular monophony and the growth of courtly song (c. 1100–c. 1300)

To this point we have focused mostly on music for the church, but other forms of Latin song appear as early as the ninth and tenth centuries. Particularly associated with the abbey of Saint-Martial is a group of songs variously called carmen, ritmus and especially versus. While many of these pieces are sacred or even para-liturgical, they also include planctus or laments, such as those on the death of Charlemagne and on the battle of Fontenay (842), satirical songs and so forth. These songs are mostly syllabic and usually strophic in form, with a single melody used for multiple stanzas of text, though the planctus and lai share the paired-verse form of the sequence, where a new melody is used for each pair of verses.33 From the twelfth century Latin songs called conductus appear in Aquitaine and Paris; these are likewise strophic and largely syllabic, though sometimes melismas appear at the beginning and/or the end of the stanza. The conductus can be either monophonic or polyphonic, with all voices moving together homorhythmically.

Peter Abelard wrote six planctus, though their melodies are written only in unheightened neumes that cannot be read, except for this lament of David on the deaths of Saul and Jonathan:

Songs in the language now known as Occitan or Provençal began to appear at the turn of the twelfth century. The relative autonomy of the southern territories and their generally more urban culture may have allowed greater scope for the creation and transmission of vernacular song than was possible in the north. Some have also suggested influence from Arabic songs, by way of Spain, but that cannot be proved. Created by poet-composers known as troubadours, these songs flourished into the thirteenth century, though southern culture was largely cut off by the Albigensian Crusade in the 1220s. Troubadours included both noble amateurs and professionals of lower rank: Guillaume IX, duc d’Aquitaine (d. 1127), and Bernart de Ventadorn (d. c. 1190–1200), who may have been the son of servants of the comte de Ventadorn,35 give an idea of the range possible. Others came from the urban merchant class, and several ended their days in the church; one is known to us only under the name Monge (Monk) de Montaudon. Several women wrote songs, though only one melody, by the comtessa de Dia, survives.

Stylistically, troubadour songs are much like their Latin counterparts: a single melody is used for multiple stanzas of poetry, and mostly syllabic text-setting allows that text to be heard clearly. While laments, crusade songs and satirical songs exist, the most common subject is love, specifically the kind of sacralised devotion known as fin’amors, often translated into English as ‘courtly love’. This is in many ways comparable to the Marian devotion that also flowered in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, and it can be difficult sometimes to determine whether the subject of a given song is the Virgin or an earthly lady. While erotic feelings can exist within fin’amors (or within a mystical spiritual context in Marian devotion), they usually cannot be consummated, because the lady is married, of higher social status, or otherwise unavailable. She can, however, be worshipped, and deeds can be done in her name. As Bernart de Ventadorn writes, ‘Fair lady, I ask you nothing/Except that you take me as your servant.’36 On the other hand, the lady’s rejection can be a mortal blow for the poet, as Bernart says elsewhere:

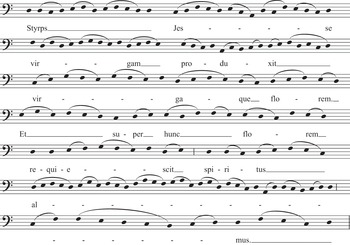

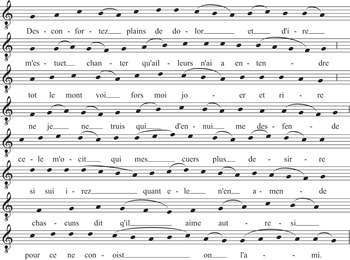

Perhaps more importantly, songs can be sung to and for her, and many examples speak of the narrator’s compulsion to sing. Troubadour songs therefore are in some ways less about love than about singing about love, especially in the high-register examples known as cansos (or grande chanson courtoise).38Gace Brulé (d. after 1213), a minor noble from Champagne and a trouvère, provides one of many examples (see Example 1.2).39

Disconsolate, full of pain and sorrow, I have to sing for I cannot direct my attention elsewhere; I see everyone, except me, play and laugh, nor do I find anyone who can protect me from distress. She whom my heart most desires is killing me, so I am distressed as she offers no redress. Each one says that he loves in this way; one cannot discern a lover by that.

The melody of this song is typical of troubadour and trouvère song in many ways: strophic with a refrain, it sets the text with mostly one note per syllable, sometimes marking the cadences at ends of lines with short melismas. This kind of setting allows the performer to focus on declaiming the text. Lines 1–2 and 3–4 receive paired melodies, which draw the ear to link the lover’s sad state to his separation from those around him. (This reading reflects only the first stanza, which usually seems to be most carefully set to the melody.) The next section rises into the upper range as he sings of how his desire is killing him, but then falls as he realises she will not save him.

Example 1.2 Gace Brulé, ‘Desconfortez’

In the short final stanza or envoi, the poet names himself and refers directly to his song:

This self-referential aspect, foreign to chant and early polyphony, may be reflected in the manuscript transmission of the songs: they often appear in collections organised by author, frequently including author ‘portraits’ and even short ‘biographies’ (vidas). The vidas cannot be trusted for strict documentary veracity, but they demonstrate an interest not only in the songs but in the lives of the individuals who created them, an attitude far removed from the fundamentally anonymous nature of chant and sacred polyphony.

The surviving sources of troubadour song come from the mid-thirteenth century and beyond, considerably later than the main flowering of composition. Some manuscripts come from Occitan areas, but many were copied elsewhere, in northern France, Catalonia and especially Italy. Only four of about forty surviving sources or fragments include musical notation. The notation used, like that for chant, generally gives no information about rhythm, much less other nuances of performance, such as the use of dynamics or instrumental accompaniment. This lack of notational specificity has created difficulties for scholars and modern performers, but it seems to suggest a kind of performative flexibility that could not be written in any system available to thirteenth-century scribes.40 Texts are generally unstable, and where a melody appears in more than one manuscript, there are nearly always variants that show a similar lack of concern for fixity and suggest not only oral transmission but also the possibility that scribes intervened in the copying of melodies as well as texts, creating and fixing problems in transmission and ‘improving’ readings according to their lights.41

While many examples of troubadour song are in the elevated style of the canso, lower-register poetry such as that of the pastourelle also exists, set to popularising melodies reminiscent of dance styles. Such songs were probably performed metrically, whether or not they are so written, and they may well have had some form of improvised instrumental accompaniment. The higher-register songs, on the other hand, may have been performed without accompaniment, facilitating the rhythmic flexibility that allows greater expression of the text.42

From the late twelfth century poet-composers known as trouvères appear in northern lands, working in French dialects. The shift may not be directly attributable to the influence of Eleanor of Aquitaine (c. 1122–1204), as has sometimes been argued, but it is worth noting her extensive family connections to secular song: her grandfather, Guillaume IX, duc d’Aquitaine, was the first documented troubadour, while her descendants included two trouvères, her son Richard, King of England, and Thibaut de Navarre, grandson of Marie de Champagne, one of Eleanor’s daughters by Louis VII and a major literary patron in her own right.43 Paris and the royal court, however, were less important for the development of trouvère song than Picardy and Champagne, and in the thirteenth century Arras became an important centre of trouvère activity among members of the merchant class, notably the poet and composer Adam de la Halle (b. c. 1245–50; d. 1285–8?). Most of the basic formal and stylistic features of trouvère songs are similar to those already outlined for the troubadours, but by the mid-thirteenth century a shift of emphasis may be seen, away from the high-register grant chant courtois and towards less elevated and more popularising styles and genres such as the pastourelle and the jeu-parti.44

Trouvère song survives in written form much more strongly than its southern counterpart. This may be in part because it flourished rather later, so it benefited from the growing book culture of Paris and the Île-de-France during the thirteenth century. It is not surprising, then, that not only more sources exist, but more sources with musical notation, and that therefore far more songs survive with melodies intact. Where Elizabeth Aubrey calculates 195 distinct melodies for 246 troubadour songs, approximately 10 per cent of the surviving poems, surviving in four sources with notation,45Mary O’Neill cites ‘some twenty substantial extant chansonniers’ of trouvère song containing approximately ‘1500 songs [that] survive with their melodies’.46

Ample evidence exists in literature, sermons and other texts for dance music, ceremonial music, popular song and so forth, but few traces of these remain.47 Courtly song and dance were often performed by minstrels or jongleurs, whose activities went beyond music to include storytelling, conversation and other forms of entertainment. Minstrels and heralds also sometimes served diplomatic or messenger roles, since they tended to travel from place to place; in the process, they could facilitate the movement of musical styles and genres. In a song written around 1210 the troubadour Raimon Vidal outlines a fictional journey from Riom at Christmas time to Montferrand (with the Dalfi d’Alvernhe), Provence (and the court of Savoy), Toulouse (where the narrator receives a suit of clothes), Cabarès, Foix (where the count is unfortunately absent) and Castillon, finally arriving at Mataplana in April.48 There is no reason to believe that similar travels were not undertaken by actual musicians.

Music can also be found in dramatic genres, from debate songs and dialogue tropes to more fully developed plays.49 Latin liturgical dramas such as those found in sources from Saint-Martial in Limoges and Saint-Benoit in Fleury, near Orléans, were completely sung, mostly using chant and chant-like styles. The Play of Daniel, one of the best-known examples today, was created by students of the cathedral school in Beauvais in the early thirteenth century for performance in the Christmas season, perhaps in conjunction with Matins on the Feast of the Circumcision (1 January).50 Vernacular religious drama tended to use spoken dialogue along with a wide range of musical styles, from chant to instrumental music. The only French secular drama that survives with a substantial body of music is Adam de la Halle’s Jeu de Robin et de Marion, probably intended to entertain troops from Arras spending Christmas in Italy around 1283. The melodies it contains use the style of popular refrains like those also found inserted into narrative poems, so they may have been borrowed rather than newly composed.

Christopher Page traces a ‘powerful secularising impulse … in many areas of cultural life’ as in other areas of culture during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.51 The ability to write and sing songs becomes an essential attribute of the courtier, a manly art suitable for indoor display in front of women.52 Indeed, this ideal of the noble who can sing and play is common within romance, and this image surely not only reflects lived reality but in turn influenced the training and self-image of young nobles who read and heard such tales. Employing minstrels or jongleurs could also enhance the reputation of a nobleman, because it showed his generosity and ability to entertain his courtiers; those travelling entertainers in turn could carry songs and tales about his prowess to other lands.53

By the thirteenth century clearly secular forms of music were much more likely to be written down and discussed by both courtiers and churchmen than they had ever been. Sacred and secular, however, were frequently intertwined throughout medieval culture: liturgy and politics served each other at the Sainte-Chapelle as at Charlemagne’s court, court functionaries from Alcuin to Machaut were educated in schools tied to the church and rewarded with ecclesiastical positions, and the languages of fin’amors and Marian devotion continually overlapped. Our neat categories do not always fit the medieval reality.

It is easy to believe that the story of French monophony ends at this point, and indeed polyphony has taken over most readers’ attention well before the end of the thirteenth century. Nevertheless, monophony continued to be performed, and it probably dominated the average person’s daily experience well into the early modern era. Monophonic dance music and popular song surely flourished – it simply was not usually written down. Gregorian chant remained the foundational musical experience of choirboys, so it served as the roots, both literally and figuratively, from which polyphony grew. New chant continued to be composed when needed, for instance by Guillaume Du Fay for a new celebration at Cambrai Cathedral in the 1450s. Since the primary tale of music history, however, is the story of compositional innovation in the written tradition, we turn the page towards a polyphonic future.

Notes

I am grateful to William Chester Jordan and Daniel DiCenso for comments that kept me from several inaccuracies in areas outside my area of specialisation. The members of my research group here at Loyola, as usual, forced me to clarify my thoughts. All remaining errors are my own.

1 et al., ‘Gallican chant’, Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online (accessed 22 May 2014).

2 Specialists in this area emphasise the fundamental heterogeneity of Merovingian liturgy; see, for example, the introduction to Missale gothicum, ed. , Corpus Christianorum Series Latina, 159D (Turnhout: Brepols, 2005), 190–3.

3 For example, see , ‘Toledo, Rome and the Legacy of Gaul’, Early Music History, 4 (1984), 49–99.

4 There had already been extensive contact between Rome and Francia by this time. See , ‘Carolingian music’, in (ed.), Carolingian Culture: Emulation and Innovation (Cambridge University Press, 1994), 275–7; and , The Christian West and its Singers: The First Thousand Years (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010), especially chapters 8–17.

5 Charlemagne was clearly considered to be an emperor, but apparently he avoided taking that title, perhaps wishing to emphasise that he ruled a new, Christian empire rather than simply taking on the mantle of the Romans. See , The Carolingians: A Family who Forged Europe, trans. (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993), 122–3.

6 See , ‘The Carolingian renaissance: education and literary culture’, in (ed.), The New Cambridge Medieval History, vol. II: c. 700–c. 900 (Cambridge University Press, 2008), 709–57. See also the work of , especially The Frankish Kingdoms under the Carolingians, 751–987 (London and New York: Longman, 1983), and Charlemagne: The Formation of a European Identity (Cambridge University Press, 2008).

7 , The Carolingians and the Written Word (Cambridge University Press, 1989); and David Ganz, ‘Book production in the Carolingian empire and the spread of Carolingian minuscule’, in McKitterick (ed.), The New Cambridge Medieval History, vol. II, 786–808.

8 , ‘Emulation and invention in Carolingian art’, in (ed.), Carolingian Culture, 248–73; and Lawrence Nees, ‘Art and architecture’, in McKitterick (ed.), The New Cambridge Medieval History, vol. II, 809–44.

9 , ‘The making of Carolingian Mass chant books’, in et al. (eds), Quomodo cantabimus canticum? Studies in Honor of Edward H. Roesner (Middleton, WI: American Institute of Musicology, 2008), 37–63.

10 Rankin, ‘Carolingian music’, 281–9.

11 The role of Gregory I is summarised in , Western Plainchant: A Handbook (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), 503–13.

12 See Rankin, ‘Carolingian music’, 290–1; and , ‘Some thoughts on music pedagogy in the Carolingian era’, in , and (eds), Music Education in the Middle Ages and Renaissance (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010), 37–51.

13 On the origins of glossing, see McKitterick, The Frankish Kingdoms, 289.

14 Text ed. and trans. in , ‘Liturgy and sacred history in the twelfth-century tympana at Chartres’, Art Bulletin, 75 (1993), 506.

15 McKitterick, The Frankish Kingdoms, 281.

16 Many of the Saint-Gall manuscripts have now been digitised as part of the Virtual Manuscript Library of Switzerland. See www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en (accessed 22 May 2014).

17 This is the mid-tenth-century manuscript St-Gall, Stiftsbibliothek, MS 484; see , ‘On the dissemination of Quem quaeritis and the Visitatio sepulchri and the chronology of their early sources’, Comparative Drama, 14 (1980), 46–69.

18 , The Musical World of a Medieval Monk: Adémar de Chabannes in Eleventh-Century Aquitaine (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

19 , ‘The cult of Saint Denis and Capetian kingship’, Journal of Medieval History, 1 (1975), 43–69; and , A Tale of Two Monasteries: Westminster and Saint-Denis in the Thirteenth Century (Princeton University Press, 2009).

20 The reference to divine luce comes from the verse of the Vespers responsory Cum sol nocturnas, quoted in , The Service-Books of the Royal Abbey of Saint-Denis: Images of Ritual and Music in the Middle Ages (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991), 230. The seventh responsory speaks of ‘the angelic companies’, another Pseudo-Dionysian concept. Reference SpiegelIbid., 232.

21 Reference SpiegelIbid., 245–8.

22 Spiegel addresses the creation of the idea of the holy king in ‘The cult of Saint Denis’. On scrofula, see , ‘The King’s evil’, English Historical Review, 95 (1980), 3–27.

23 , The Virgin of Chartres: Making History through Liturgy and the Arts (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010).

24 Example 1.1 is edited from Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS fonds latin 15181, fol. 379v; image accessed from http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8447768b/f766.item (accessed 22 May 2014). The manuscript is the first part of a two-volume early fourteenth-century noted breviary from Notre-Dame of Paris according to the CANTUS database (cantusdatabase.org). Spelling is as given in the manuscript, except that abbreviations have been silently expanded and i/j and u/v have been given their modern forms. Slurs indicate ligatures in the source. This chant is also edited in Fassler, The Virgin of Chartres, 414 (text and translation) and 415 (music).

25 This reading is independent of Fassler’s, which rightly stresses the music’s support of the structural units of the text, along with emphasis on key words. Ibid., 125–6.

26 , Music and Ceremony at Notre Dame of Paris, 500–1550 (Cambridge University Press, 1989).

27 The phrase docere verbo et exemplo is common in Augustinian literature. This paragraph is largely based on , Gothic Song: Victorine Sequences and Augustinian Reform in Twelfth-Century Paris (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

28 , ‘Aurelianis civitas: student unrest in medieval France and a conductus by Philip the Chancellor’, Speculum, 75 (2000), 589–614.

29 , ‘Speculative “musica” and the medieval University of Paris’, Music and Letters, 90 (2009), 177–204.

30 , Visualizing Kingship in the Windows of the Sainte-Chapelle (Turnhout: Brepols, 2002), v.

31 , The Making of Saint Louis: Kingship, Sanctity, and Crusade in the Later Middle Ages (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2008), 105, 261.

32 The melody is given as the first responsory for Matins in , ‘Ludovicusdecus regnantium: perspectives on the rhymed office’, Speculum, 53 (1978), 316–17.

33 For the intersections among these three genres, see , Words and Music in the Middle Ages: Song, Narrative, Dance and Drama, 1050–1350 (Cambridge University Press, 1986), 80–2.

34 This melody is from a thirteenth-century English source, Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 79, fols 53v–56. Stevens, Words and Music in the Middle Ages, 121–6.

35 Bernart’s origin is based on untrustworthy sources and has been questioned; for a summary of the issue see , The Music of the Troubadours (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996), 9.

36 From the seventh stanza of ‘Non es meravelha s’eu chan’: , and (eds and trans.), Songs of the Troubadours and Trouvères: An Anthology of Poems and Melodies (New York: Garland, 1998), 64–5.

37 From the seventh stanza of ‘Can vei la lauzeta mover’: Rosenberg, Switten and Le Vot (eds and trans.), Songs of the Troubadours and Trouvères, 68–9.

38 On the self-referentiality of songs, see for instance , Courtly Love Songs of Medieval France: Transmission and Style in the Trouvère Repertoire (Oxford University Press, 2006), 56–62.

39 Example 2.1 is edited from Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS fonds français 845, fol. 38r; image accessed from http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b6000955r/f85.image.r=845.langEN (accessed 22 May 2014). Spelling is as given in the manuscript, except that abbreviations have been silently expanded, apostrophes are given when appropriate, and i/j and u/v have been given their modern forms. Slurs indicate ligatures in the source. See (ed.), Songs of the Trouvères (Newton Abbot: Antico Edition, 1995), xv (text and translation) and 13 (music).

40 The various theories are summarised in Aubrey, The Music of the Troubadours, 240–54. has made the fullest study of the question of instrumental participation in Voices and Instruments of the Middle Ages: Instrumental Practice and Songs in France, 1100–1300 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986).

41 See Aubrey, The Music of the Troubadours, 51–65; and O’Neill, Courtly Love Songs, 53–92.

42 Aubrey discusses the genres of troubadour song in chapter 4 of The Music of the Troubadours, 80–131.

43 The best introduction to Eleanor is , Eleanor of Aquitaine: Queen of France, Queen of England (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009).

44 O’Neill, Courtly Love Songs, especially chapter 5, 132–73. In chapter 6, 174–205, however, O’Neill argues that to some degree Adam de la Halle attempts to reverse this movement, returning to an older aesthetic.

45 Aubrey, The Music of the Troubadours, 49.

46 O’Neill, Courtly Love Songs, 13, 2.

47 has mined this area particularly well in The Owl and the Nightingale: Musical Life and Ideas in France, 1100–1300 (London: Dent, 1989).

48 This song is discussed in , ‘Court and city in France, 1100–1300’, in (ed.), Antiquity and the Middle Ages: From Ancient Greece to the 15th Century (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1990), 209–12, and in Page, The Owl and the Nightingale, 42–60.

49 Most of this paragraph draws from et al., ‘Medieval drama’, Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online (accessed 22 May 2014). See also , ‘Liturgical drama and community discourse’, in and (eds), The Liturgy of the Medieval Church (Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 2001), 619–44.

50 , ‘The staging of The Play of Daniel in the twelfth century’, in (ed.), The Play of Daniel: Critical Essays (Kalamazoo, MI: Medieval Institute Publications, 1996), 15–17.

51 Page, The Owl and the Nightingale, 3.

52 Page, Voices and Instruments, 3–8.

53 Page, The Owl and the Nightingale, 42–4.