INTRODUCTION

Pertussis, or ‘whooping cough’, is a vaccine-preventable bacterial infection caused by Bordetella pertussis [Reference Heymann1] and remains endemic in most parts of the world [2]. A highly contagious disease, particularly in the first 2 weeks of infection, pertussis can result in significant morbidity and mortality [Reference Heymann1]. In 2014, global immunisation coverage for receipt of all three doses of a primary course of pertussis vaccine was 86% (>90% in Australia) [3]. High infant coverage does not mitigate against pertussis outbreaks, however, as evidenced by Australia's nationwide outbreak in 2010, where pertussis was the most commonly notified vaccine-preventable disease (>50% of all such notifications) [4, Reference Pillsbury, Quinn and McIntyre5]. During pertussis epidemics in Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (hereafter respectfully referred to as ‘Indigenous’) are affected over three times more than non-Indigenous Australians, with higher rates of morbidity, mortality and hospitalisations [Reference Sinclair, Joseph and Menzies6]. The current National Immunisation Program in Australia recommends an acellular pertussis vaccine for infants at 6–8 weeks of age, followed by doses at 4 and 6 months with booster doses at 18 months, 4 years and 10–15 years. An adult booster in the form of dTpa is recommended at 50 years for those who have not received a diphtheria-tetanus boost in the previous 10 years; and dTpa recommended for those ⩾65 years who have not received a pertussis-containing vaccine in the previous 10 years [7].

Pertussis is commonly transmitted to infants from exposure to parents, siblings – responsible for up to 80% of infections – and to a lesser extent grandparents and exposure to other children in child care and other health care settings [Reference Wiley, Zuo, Macartney and McIntyre8]. One Australian study of pertussis notifications from 2008 to 2012 identified siblings as the most common source of infection to infants younger than 6 months of age [Reference Bertilone, Wallace and Selvey9]. As vaccine-induced immunity wanes over time, it is likely that these school-aged siblings become vulnerable to acquiring pertussis infection and hence are the most likely source of transmission [Reference Wiley, Zuo, Macartney and McIntyre8–Reference Viney, McAnulty and Campbell-Lloyd10].

Control of pertussis continues to be a high public health priority, with prevention of severe disease in infancy a specific focus. Recent control strategies have included preventing pertussis in infants by minimising exposure to potential cases and the ‘cocoon strategy’ of vaccinating parents, caregivers and others with infant contact. This seeks to minimise the likelihood that infants will come into contact with an infectious case [Reference Wiley, Zuo, Macartney and McIntyre8, 11].

Infants younger than 6 months of age, who are too young to complete the primary immunisation course, can now get protection via maternal antibody transfer through a pertussis-containing vaccine given to women in the third trimester of each pregnancy [Reference Amirthalingam12–Reference Dabrera14]. In August 2014, Queensland was the first state to introduce a funded pertussis vaccination program in pregnancy in Australia [15]. Subsequently, pertussis vaccination in pregnancy was recommended nationally in Australia in 2015 [7] and is now funded by every state and territory across the country [Reference Beard16]. The Australian Government's Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee is considering whether to add the maternal pertussis vaccine to the National Immunisation Program [17].

In order to evaluate the impact of the maternal pertussis vaccination program, particularly in infants younger than 4 months of age where disease burden and severity are typically highest [Reference Wood18–20], an understanding of the epidemiology of pertussis is required, prior to the implementation of the program. Our study aimed to analyse baseline rates of pertussis notifications by: age-group; sex; women of childbearing age; and Indigenous status.

METHODS

Study design and population

We conducted baseline retrospective descriptive analyses of all confirmed and probable (clinical) pertussis notifications in Queensland from 1 January 1997 to 31 December 2014, inclusive. Cases of pertussis were classified according to the Australian National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System definition below (Box 1) [21], there were no changes to the case definition throughout the study period. Acellular pertussis vaccine replaced whole-cell pertussis vaccine in the schedule in July 1997; December 1997 for the 18 month and 4–5 years booster doses only and March 1999 for the 2, 4 and 6 month doses [15], signalling a period of difference in the type of vaccine for two of the 18 year study period.

Box 1. Pertussis case definition, Australian National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System

Laboratory definitive evidence – Isolation of Bordetella pertussis OR detection of B. pertussis by nucleic acid testing OR Seroconversion in paired sera for B.pertussis using whole cell or specific B.pertussis antigen(s) in the absence of recent pertussis vaccination

Laboratory suggested evidence – In the absence of recent vaccination, significant change (increase or decrease) in antibody level (IgG, IgA) to B. pertussis whole cell or B. pertussis specific antigen(s) OR single high IgG and/or IgA titre to Pertussis Toxin (PT) OR single high IgA titre to Whole Cell B. pertussis antigen

Clinical evidence – A coughing illness lasting 2 or more weeks OR paroxysms of coughing OR inspiratory whoop OR post-tussive vomiting

Epidemiological evidence – Link established when there is contact between two people involving a plausible mode of transmission at a time when: one of them is likely to be infectious (from the catarrhal stage, approximately 1 week before to 3 weeks after onset of cough) AND the other has an illness which starts within 6 to 20 days after this contact AND at least one case in the chain of epidemiologically linked cases (which may involve many cases) is a confirmed case with either laboratory definitive or laboratory suggestive evidence

Analysis and statistical methods

We calculated summary statistics as appropriate, using proportions, counts and average annual notification rates per 100 000 population by year of notification, age, sex and Indigenous status. We used age-specific Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) estimated Queensland resident population data for the respective years 1997–2014 as the denominator when calculating the average annual notification rates [22]. For children, younger than 12 months old, age-specific notification rates and incidence rate ratios were also calculated by month of age and by Indigenous status. Incidence rate ratios in these children were calculated using only notifications where the ‘Indigenous status’ field was complete. Indigenous population denominator data were estimated as ~8% of total Queensland children younger than 12 months of age [23]. We used the 15–<45 year age group to reflect women of child-bearing age in our population [Reference Hilder, Parker, Jahan and Chambers24]. Using notification counts, we calculated rates and incidence rate ratios by sex and Indigenous status specifically in the 15–<45 year age-group. Data were analysed using Stata v.14 (StataCorp, Texas, USA) and graphs and figures were compiled using Microsoft Excel.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for this project was provided by the Children's Health Queensland Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/14/QRCH/367).

RESULTS

Study population

There were 53 901 notifications of pertussis over the study period, consistent with the case definition in Box 1. The modal month for notifications was November (11%), whereas April (6%) had the lowest percentage of notifications.

Baseline characteristics of all notified cases

Over the 18 year observation period (1997–2014), the median age of persons notified with pertussis was 35·2 years, ranging from a median of 12·6 years in 1997 to 54·5 years in 2007 (overall age range: <1–99 years). Thirty per cent of all notifications (16 438/53 901) had the ‘Indigenous status’ field complete and of these; 1630 (10%) were recorded as being Indigenous.

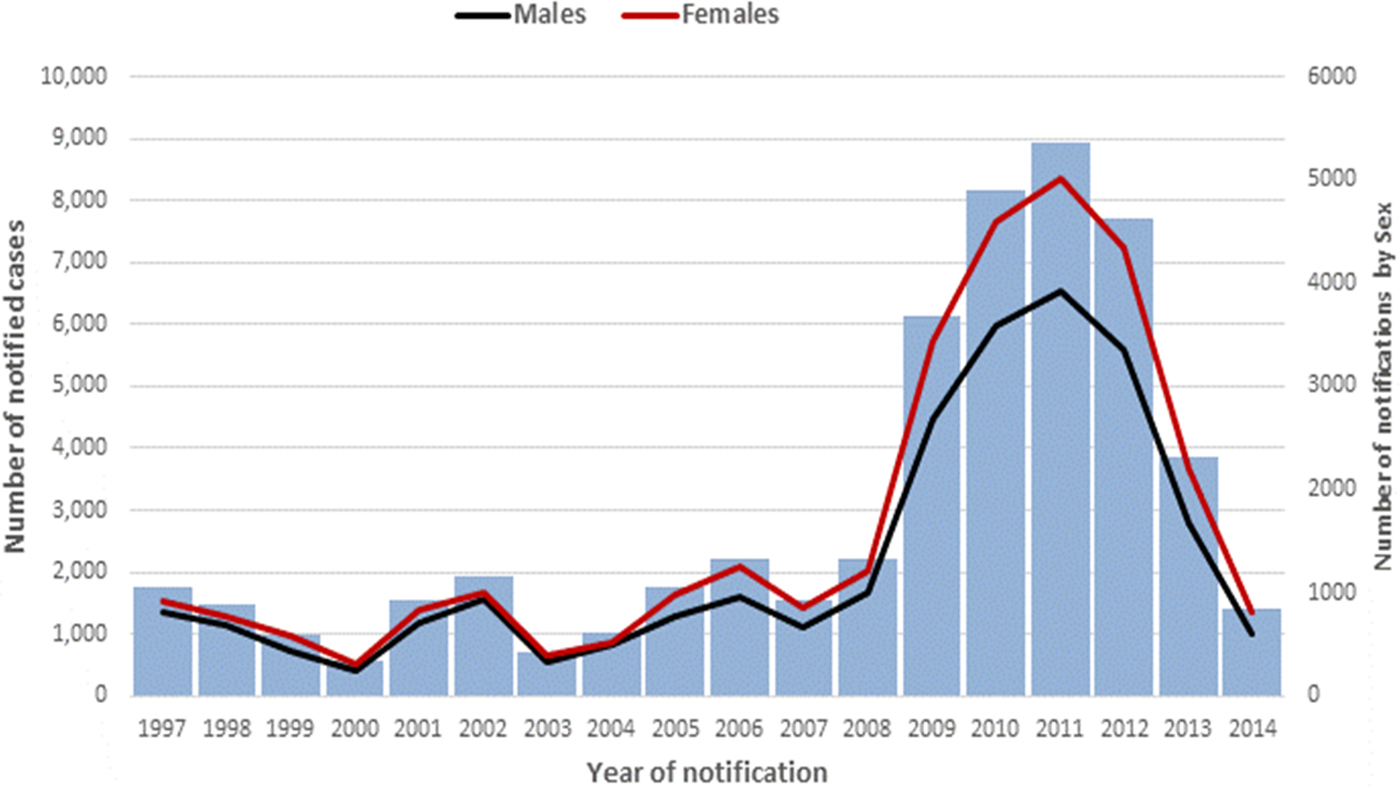

After 12 years of low and stable counts, pertussis notifications were substantively higher over the 2009–2013 period before returning to near-baseline levels in 2014 (Fig. 1). The highest number of notifications occurred in 2011 (8984), whilst the lowest number of notifications was 537 in 2000. Females made up 56% of all notifications and 61% of notifications in Indigenous peoples. There were more females compared with males for each year of notification (Fig. 1) and across almost all age groups when expressed as age-specific rates (data not shown).

Fig. 1. A number of pertussis notifications by year and sex, Queensland, 1997–2014.

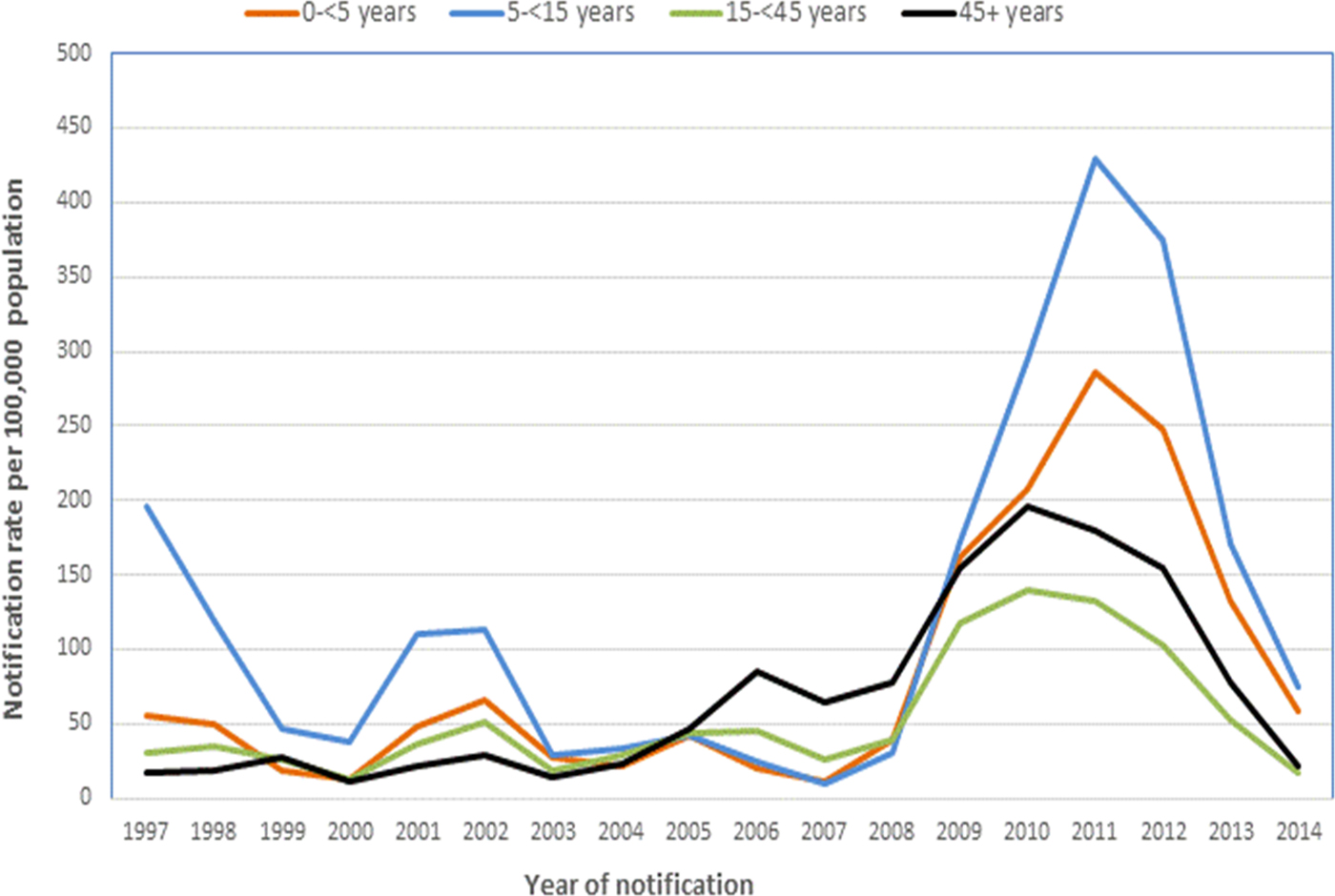

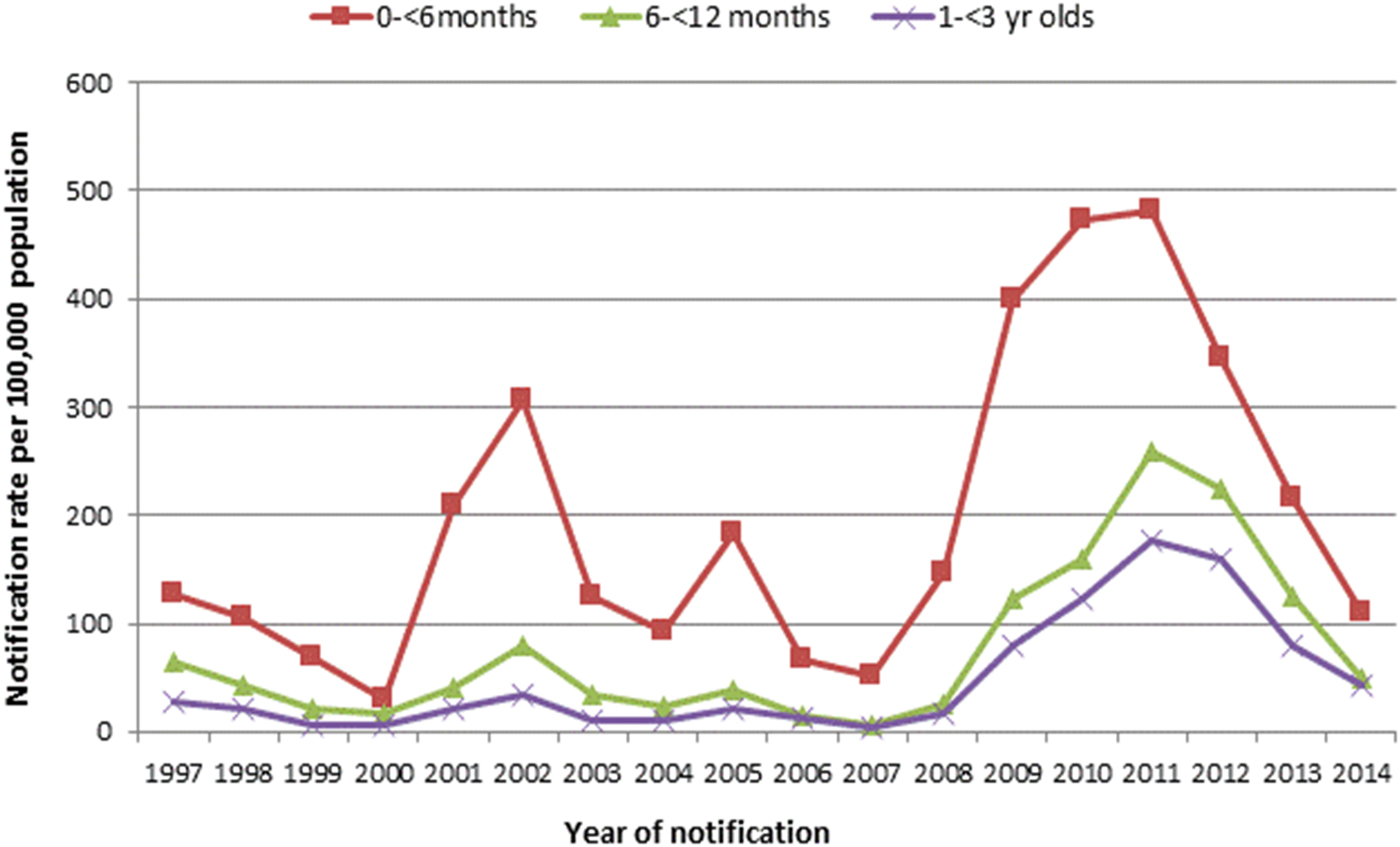

There were minor peaks in notification rates in 2001–2002 and 2005–2006, preceding a marked peak in 2009–2012. The same epidemic cycle of pertussis was evident in the average annual age-specific notification rates for all age-groups (Fig. 2) as well amongst children younger than 3 years of age (Fig. 3). Infants aged younger than 6 months had the highest notification rates during each epidemic cycle and notification year when compared with other children younger than 3 years (Fig. 3). The age-specific rate among infants was also higher than all other age groups with the exception of school-aged children (those aged 5–<15 years) in 2001–2002 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Average annual notification rates of pertussis per 100 000 population, by year of notification and age group, Queensland, 1997–2014.

Fig. 3. Age-specific notification rates of pertussis in children younger than 3 years of age per 100 000 population per year, by age group, Queensland, 1997–2014.

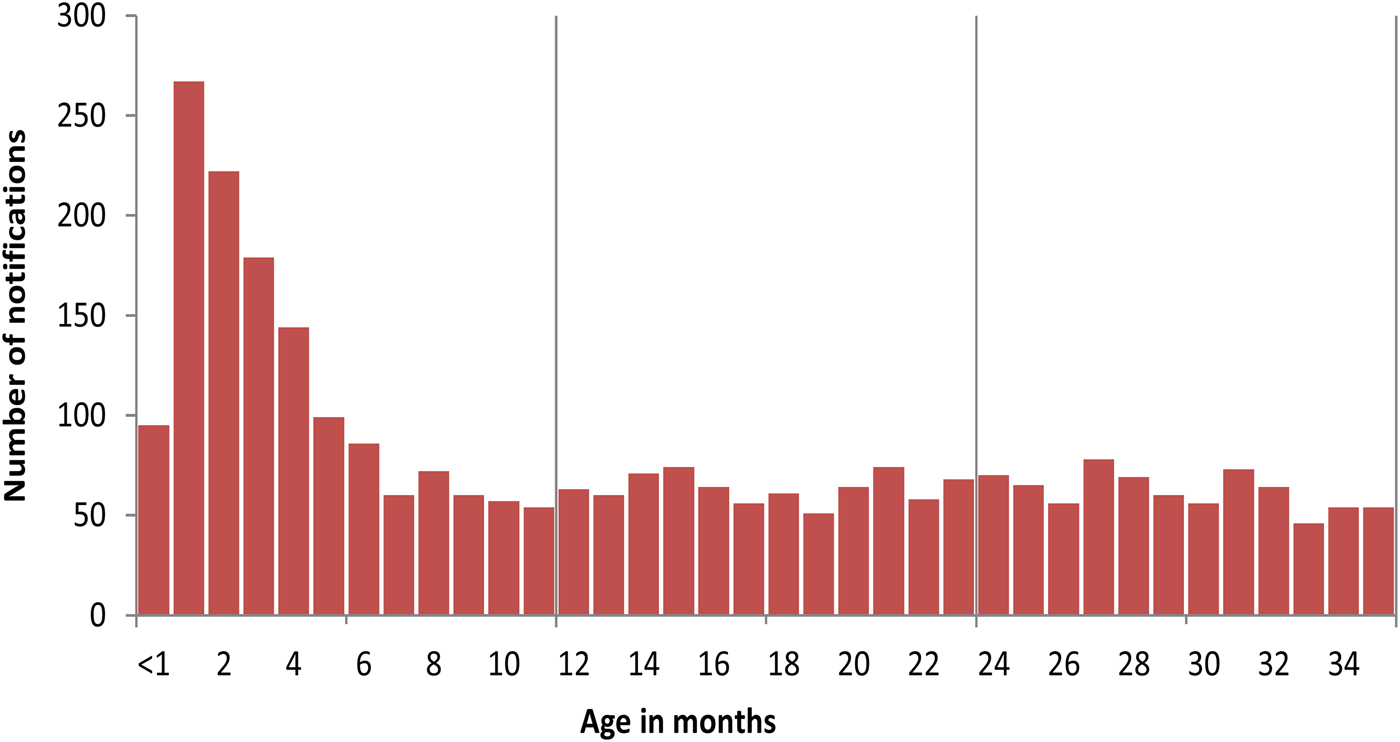

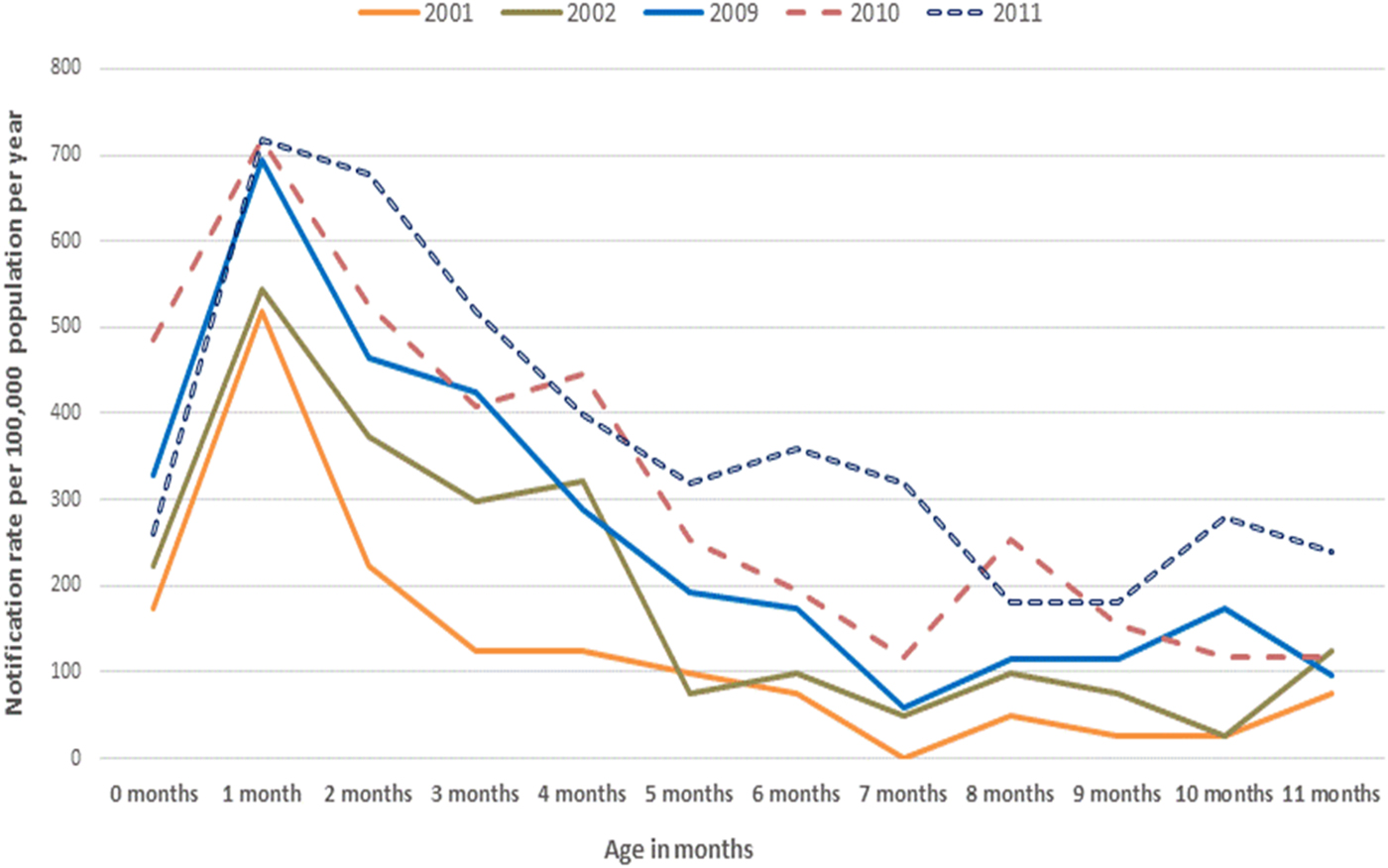

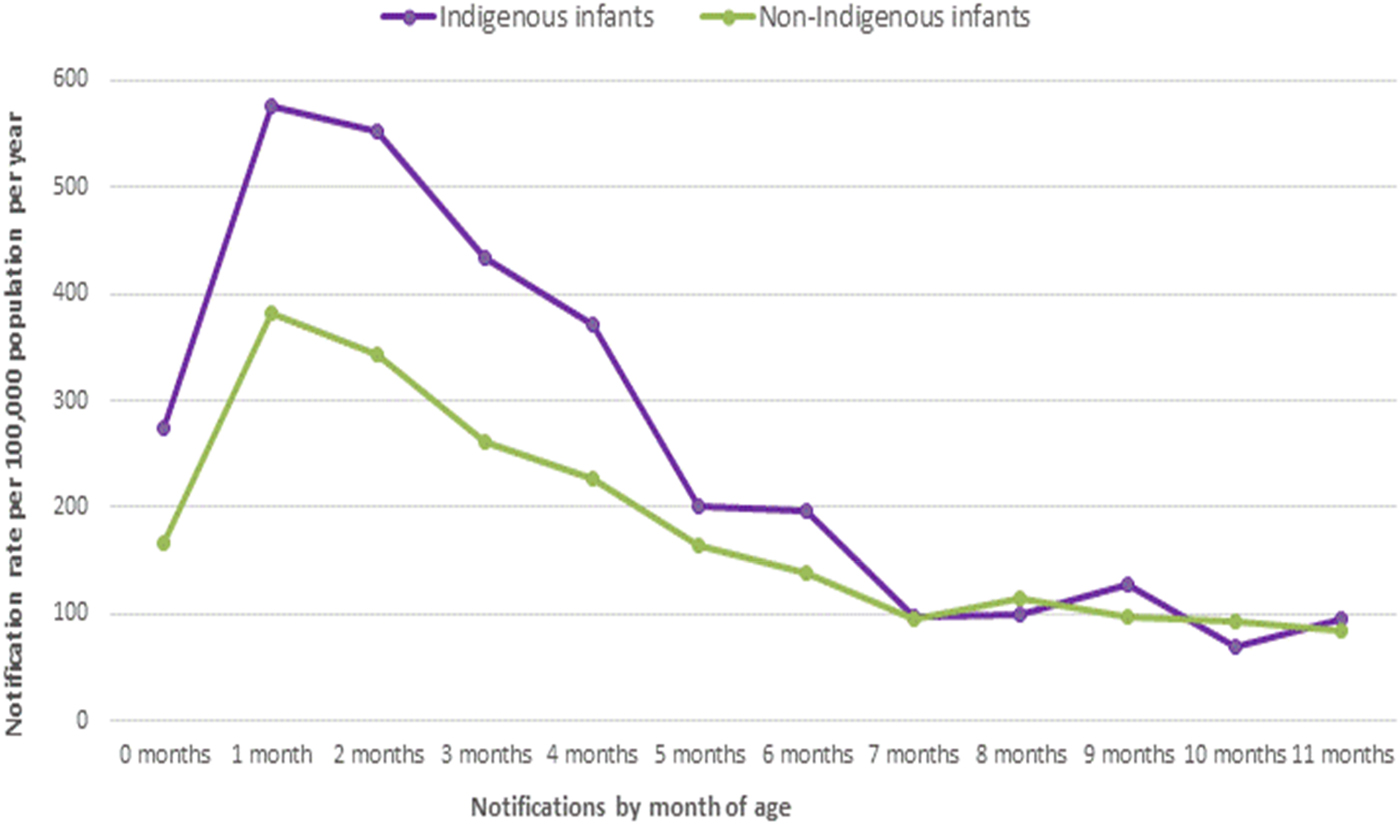

Over the study period, the average annual age-specific notification rate amongst infants younger than 6 months of age was 196·5 per 100 000 population per year. Twenty-one per cent (163/761) of these notifications were Indigenous infants. Among infants aged younger than 3 years, the number of notifications peaked between 1 and 4 months of age (Figs 4 and 5).

Fig. 4. A number of pertussis notifications in children younger than 3 years of age, Queensland, 1997–2014.

Fig. 5. Rates of pertussis notifications per 100 000 population per year in infants younger than 12 months of age, by selected epidemic years, Queensland.

Infants younger than 12 months of age

Further analysis of pertussis notification rates by month of age for all infants younger than 12 months of age showed the average annual age-specific notification rates were highest in those at 1 month of age at 307·7 per 100 000 population per year (Table 1). This was also evident when examining the average annual notification rates by year of pertussis epidemics in Queensland (Fig. 5). Seventy-two per cent of these data were complete for the variable ‘Indigenous status’ in this age group (1007/1401). Of these data available for ‘Indigenous status’ – 21% or 211/1007 of infants under 12 months were recorded as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander. A similarly high proportion was also evident in infants younger than 6 months of age 163/761 (21%). The notification rates for Indigenous infants younger than 12 months of age were substantively higher across all months of age compared with non-Indigenous infants in the same age group, peaking at 576·3 per 100 000 per year at 1 month of age compared with 382·0 in non-Indigenous infants (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Rates of pertussis notifications per 100 000 population in infants younger than 12 months of age, by Indigenous status, Queensland 1997–2014.

Table 1. Pertussis notifications by month of age and Indigenous status in children aged younger than 12 months, Queensland, 1997–2014

* Average annual notification rate per 100 000 population per year for Queensland 1997–2014, inclusive.

† Denominators calculated using estimated age-standardised Australian Bureau of Statistics Indigenous population for Queensland [25].

‡ Incident rate ratios between Indigenous and non-Indigenous infants.

§ Total incidence rate ratio between Indigenous and non-Indigenous infants younger than 12 months of age. Numbers differ due to missing data for ‘Indigenous status’.

║ Deaths recorded as being as a direct result of pertussis infection.

Deaths

Whilst death due to a notifiable condition is not itself notifiable, there were six deaths recorded in the notification dataset which were directly related to pertussis infection (Table 1). All six deaths occurred in infants younger than 2 months of age (fewer than 56 days of age lived). One child was identified as being Indigenous. Five out of the six deaths were male infants (83%) and deaths occurred between July and September in the years 2001 (2), 2002 (2), 2005 (1) and 2012 (1), consistent with the years of pertussis notification peaks in Queensland. The deaths were not clustered geographically.

Women of child bearing age

Average annual notification rates per 100 000 population were higher in females in all age groups throughout the period of observation compared with males of the same age groups. Specifically, women of child bearing age in Queensland [Reference Hilder, Parker, Jahan and Chambers24] (15–<45 years) recorded 40% higher average annual notification rates per 100 000 population per year compared with males in the same age groups. For Indigenous women aged 15–<45 years, this result was 90% higher than in men for the same age group. Indigenous women also recorded almost double the number of total notifications compared with Indigenous males in the same age group (Table 2). Overall notification rates for persons aged 15–<45 years were higher in non-Indigenous peoples compared with Indigenous peoples (Table 2).

Table 2. A number of pertussis notifications and rates per 100 000 population among persons aged 15–<45 years, by sex and Indigenous status, Queensland, 1997–2014

* Average annual notification rates per 100 000 population, 1997–2014 inclusive.

† Incident rate ratios between males and females.

‡ Incident rate ratios between Indigenous and non-Indigenous males and females.

§ Denominators calculated using estimated age-standardised Australian Bureau of Statistics Indigenous population for Queensland [Reference Heymann1].

Numbers differ due to missing data for the variable ‘Indigenous status’.

DISCUSSION

We analysed routine surveillance data for the years 1997–2014 to understand the epidemiology of pertussis (‘whooping cough’) in Queensland, Australia, prior to the implementation of the maternal vaccination program in August 2014. We found that amongst infants younger than 12 months of age, pertussis notifications were highest in those younger than 4 months of age, peaking in infants between 1 and 2 months of age. Women were over represented in all age groups, particularly in the child bearing and child caring age groups, as were Indigenous women and infants.

Average annual notification rates

The median age for the entire cohort of 35·2 years (n = 53 901) hides the increase in the median age over time (reflecting diagnoses in older age groups). Moreover, this measure does not reflect the burden of disease by age, which is evident in the analyses of age-specific notification rates by year of notification. Notifications for pertussis in Queensland rose markedly from 2009 to 2012 during the nationwide epidemic [Reference Viney, McAnulty and Campbell-Lloyd10, 20]. Infants between 1 and 2 months of age recorded the highest average annual notification rates of 307·7 per 100 000 population per year which was most evident during these epidemic peaks. Rates were almost double in Indigenous infants of the same age. Rates declined sharply once infants were older than 5 months of age in both populations. Whilst age-specific notification rates in Queensland increased for all age groups from 2009, rates in infants younger than 6 months of age were particularly high, as was the case for rates in Indigenous women in all age groups compared with men in the same age groups. Specifically, women of child bearing ages (15–<45 years) in Australia [Reference Hilder, Parker, Jahan and Chambers24] often had more than double the rates of pertussis infections compared with males in the same age group and again this was even more evident when comparing rates between Indigenous men and women in the same age groups. It is possible that this may be an effect of child bearing, child caring, or health-seeking behaviour. Apart from mortality, our findings are consistent with the current literature which reports that pertussis incidence, morbidity and mortality are generally all higher in females than males [2, Reference Pillsbury, Quinn and McIntyre5, Reference Viney, McAnulty and Campbell-Lloyd10, Reference Carlsson19]. Our study found five out of the six deaths (83%) due to pertussis infection were amongst male infants. All deaths occurred in children younger than 2 months (<56 days) of age.

Interestingly, we found the total average annual notification rates per 100 000 population per year were higher in non-Indigenous Australian 15–<45 year olds compared with Indigenous 15–<45 year olds (53·4 vs. 28·8, respectively). We believe this to be as a result of poor data quality for the variable ‘Indigenous status’ in notification data, leading to under-ascertainment of pertussis cases in this population. Given hospitalisation rates as a direct result of pertussis infections are 2–3 times higher in Indigenous peoples compared with other Australians [Reference Sinclair, Joseph and Menzies6], comparisons of total notification rates between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in the 15–<45 year old age groups presented in our study may be unreliable. Other Australian studies have reported similar pertussis notification differences between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples and have expressed similar concerns regarding the reliability of their results due to poor data quality [Reference Sinclair, Joseph and Menzies6].

Vaccination strategies

Infants younger than 2 months of age clearly carried the highest burden of pertussis in our study, both in terms of notifications and deaths directly due to pertussis. This pattern is consistent with the national and international literature [Reference Viney, McAnulty and Campbell-Lloyd10, Reference Carlsson19]. The disease burden was 3·5 times higher for Indigenous infants of the same age which is also consistent with national data for a similar time period [Reference Sinclair, Joseph and Menzies6]. These findings indicate that infant vaccination strategies in place during the period of observation were having a limited impact with respect to the protection of these youngest infants. Infants are particularly vulnerable to severe outcomes from pertussis infections at this age, having not yet had the opportunity to be protected by at least two doses of a pertussis-containing vaccine which are recommended in Australia to be given at 6–8 weeks of age, followed by doses at 4 and 6 months [7].

The UK recommended routine pertussis vaccination in pregnancy as a direct response to their pertussis epidemic [Reference Amirthalingam12, Reference Dabrera14]. This strategy has been highly effective in reducing their high pertussis burden in early infancy by 91% [Reference Amirthalingam12]. Other encouraging international data also support the effectiveness of a maternal pertussis vaccination strategy in reducing the burden of illness in infants younger than 6 months of age [Reference Dabrera14]. In Australia, a nationally recommended and State and Territory funded maternal pertussis vaccination program has been operational since 2015 [Reference Beard16]. In Queensland, our data from a pre-maternal pertussis vaccination period clearly show there is a high disease burden in early infancy that would be expected to reduce if adequate vaccination uptake in pregnancy can be achieved. In order to monitor the impact of the maternal pertussis vaccination program, it is essential that post-implementation data are analysed to determine if morbidity and mortality from pertussis are reduced among infants too young to be vaccinated by current childhood immunisation programs. Data are also limited for maternal and infant birth outcomes in women who have received pertussis vaccination during pregnancy. Along with uptake and effectiveness of the maternal pertussis vaccination program, establishing the safety of the vaccine in pregnancy with respect to birth outcomes will also be important.

Limitations

As with all observational data, some of our findings should be interpreted with caution. Data for the variable ‘Indigenous status’ were missing in 70% of cases and where data were available, 10% of cases identified as being Indigenous. Given that ABS figures estimate that 4% of the Queensland population in 2014 identified as being ‘Indigenous’ [23], this may inaccurately reflect an over representation of, or a true burden of disease in the Indigenous population. To improve under-identification of ‘Indigenous status’ in these data, the variable ‘Indigenous status’ added to laboratory request forms is required, as well as ensuring completeness of data for this variable is captured in case report forms. In relation to disease severity, hospitalisation and vaccination data were not available in our dataset. Hospitalisation is an indicator of disease severity and vaccination status is critical for assessing vaccine coverage and vaccine failures, thus more in-depth analyses of these data was unable to be carried out. In Queensland, deaths occurring directly as a result of a notifiable disease are not required to be formally notified. This was reflected in the data as 97% of the notification records had missing data for the variable ‘Died of condition’. Importantly though, of the six deaths that were recorded, all were infants younger than 2 months of age, similar to patterns seen in other Australian and international settings [Reference Viney, McAnulty and Campbell-Lloyd10, Reference Carlsson19]. It is possible, therefore, that the total number of deaths due to pertussis during the observed period may be underestimated. Further analyses using death register data and paediatric intensive care unit data would enhance the data quality.

CONCLUSION

Findings from our study have identified a high disease burden in early infancy and amongst women of child bearing age. Both of these groups should potentially receive a dual benefit from the maternal pertussis vaccination program. Indigenous women need to be a high priority for maternal vaccination from an equity perspective as the disease burden is disproportionately high in this group. Assessment of the epidemiology of pertussis following an operational period of this maternal pertussis vaccination program will be important, as will an evaluation of the uptake, safety and effectiveness of the program in relation to maternal and infant birth outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

National Centre for Epidemiology & Population Health, Australian National University, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Master of Philosophy in Applied Epidemiology (MAE) program. Queensland Health Communicable Diseases Branch, Brisbane and Queensland Government Department of Health. We thank Sarah Sheridan for her assistance with data acquisition and interpretation. Lisa McHugh was supported by the National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, Australian National University, Canberra as part of the Master of Philosophy in Applied Epidemiology (MAE) program. She is currently supported by an Australian Postgraduate Award scholarship by Charles Darwin University and an Enhanced Living scholarship by Menzies School of Health Research as part of a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) degree.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

LMc conducted all aspects of this project from ethics approvals, data analyses and manuscript writing. SBL and KV assisted with supervision of the overall project, cross-checking results and all manuscript drafts. RMA assisted with Stata coding, interpretation of results, assistance with graphics and manuscript editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

None.