Introduction

The Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) initiative was established in 2007 with the aim of providing evidence-based therapies for the treatment of anxiety and depression. More recently, however, many IAPT services have developed beyond this initial remit to include treatment for additional mental health problems, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as well as supporting the management of long-term health conditions (including coronary heart disease, diabetes and chronic pain). Over 900,000 people now access IAPT services each year (NHS England, 2016). Within IAPT, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is the model of choice and therapy is guided by evidence-based practice (EBP), which is endorsed by NICE (National Institute of Clinical Excellence) guidelines and protocols (Mirza and Corless, Reference Mirza and Corless2009).

IAPT's Black and Minority Ethnic's (BME) ‘Positive Action Guide’ (2009) recognizes that people from BME communities may have additional barriers to overcome in order to access psychological therapy. One potential barrier identified is that of language and it is acknowledged that ‘non-English-speaking people may not be able to communicate their needs effectively if an IAPT service lacks appropriate language capacity. This could mean that proper and correct assessments may not be made.’ As the number of BME clients including refugees has increased in recent years, there has been increased requirement for the use of interpreters to facilitate communication in assessment and treatment in IAPT (IAPT, 2013).

Context

Consistent with the notion that talking therapies should be accessible to all (Roth and Pilling, Reference Roth and Pilling2007), the IAPT programme adopts a stepped care approach. The stepped care approach is based on the key fundamental assumptions of equivalence of outcomes, resource efficiency and the delivery of interventions that are acceptable to clients and practitioners (Bower and Gilbody, Reference Bower and Gilbody2005). Within the structure, the stepped care pathways facilitate access, and enable movement that ensures psychological benefits through efficient use of trained practitioners and resources.

The focus of this study is at steps 2 and 3 of the stepped care model. Step 2 delivers guided self-help (GSH) interventions, based on the CBT model, to people who present with mild to moderate depression and anxiety. GSH intervention is implemented by a CBT trained Psychological Well-being Practitioner (PWP) and may be delivered face-to-face or via telephone contact. Intervention could include computerized CBT, physical health group programmes and psycho-educational workshops, depending on the needs of the client, and may be complemented by the use of self-help books, and information leaflets, during and in-between sessions. Clients attend up to six sessions within step 2, but are moved up to step 3 if there is no improvement in outcome (Roth and Pilling, Reference Roth and Pilling2007).

Step 3 provides high-intensity psychological therapy to people with moderate to severe depression and anxiety disorders. Therapies include CBT or interpersonal therapy, usually delivered by a psychologist or CBT-trained therapist (NICE, 2009). Clients can be referred by their GP, or another health professional, to the IAPT services to be assessed and stepped up, or down, as required in the care pathway.

Therefore, working with interpreters to facilitate communication within the therapies delivered at steps 2 and 3 in IAPT is essential to provide accessible talking therapies to BME, and refugee communities, who are not fluent in English. Clients requiring the support of an interpreter often present with complex problems, including social, economic and diaspora related issues, as well as physical health conditions (IAPT, 2013; Dubus, Reference Dubus2016).

To date, working with interpreters is not a skill that has been given a lot of attention in most IAPT training programmes. With evidence-based practice as the dominant discourse in primary care, and CBT the psychological therapy of choice, much of the research has focused on the effectiveness of its protocols and standards (Mirza and Corless, Reference Mirza and Corless2009). While is estimated that almost 40% of people accessing IAPT also have physical health problems, including long-term conditions (NHS England and NICE Implementation Guide, 2016), there have been very few studies focused on the work with interpreters in IAPT; particularly with regard to interventions where there are co-morbid psychological and physical health conditions.

The aim of this study is to explore the experience of cognitive behavioural therapists and PWPs working within an IAPT service, who have worked in collaboration with interpreters to facilitate communication with clients during CBT and GSH. It is intended that the results of the study will contribute towards the development of practice protocols for working with language barriers in primary health care.

Evidence from literature

Of relevance to this study, the process of collaborative working with interpreters, and how this impacts on therapeutic outcomes, has been studied in mental health services and psychotherapy. While the roles and functions of interpreters has been widely debated, and contested, in the literature (e.g. Westermeyer, Reference Westermeyer1990; Drennan and Swartz, Reference Drennan and Swartz1999, Reference Drennan and Swartz2002; Farooq and Fear, Reference Farooq and Fear2003; Hamerdinger and Karlin, Reference Hamerdinger and Karlin2003; Tribe and Morrissey, Reference Tribe and Morrissey2004; Wallin and Ahlström, Reference Wallin and Ahlström2006; Tribe and Thompson, Reference Tribe and Thompson2008; Pugh and Vetere, Reference Pugh and Vetere2009; Dubus, Reference Dubus2016) the findings of most studies indicate that the outcomes of therapy delivered with interpreters are as effective as those delivered without (Brune et al., Reference Brune, Eiroá-Orosa, Fischer-Ortman, Delijaj and Haasen2011; Brisset et al., Reference Brisset, Leanza and Laforest2013).

Several models of interpreting are posited within mental health and other settings. The most distinctive model of interpretation is the ‘linguistic’ or ‘blackbox’ model, in which verbatim translations are sought, an approach criticized for objectifying the role of the interpreter (Westermeyer, Reference Westermeyer1990; Drennan and Swartz, Reference Drennan and Swartz1999; Tribe and Morrissey, Reference Tribe and Morrissey2004; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Martell, Pazdirek, Caruth and Lopez2005; Searight and Searight, Reference Searight and Searight2009). Alternatively, the role of the interpreter as a ‘cultural broker’, in which relevant cultural meanings are interpreted, has also been identified (Drennan and Swartz, Reference Drennan and Swartz1999; Tribe and Morrissey, Reference Tribe and Morrissey2004; Dubus, Reference Dubus2016). Equally, a constructionist model focuses on meanings rather than verbatim translations (Tribe and Morrissey, Reference Tribe and Morrissey2004). In some settings, such as family therapy, bilingual interpreters have been trained in relevant skills and worked as co-therapist while using their interpreting skills (Rankin, Reference Rankin1999; Raval and Smith, Reference Raval and Smith2003).

Most studies highlight the importance of using trained interpreters in order to limit any errors of interpretations that could impact on clinical judgements for practitioners (e.g. Flores et al., Reference Flores, Abreu, Barone, Bachur and Lin2012; Gray et al., Reference Gray, Hilder and Stubbe2012). Recent evidence has shown that trained interpreters make fewer communication errors than those who are not formally trained. More specifically, Flores et al. (Reference Flores, Abreu, Barone, Bachur and Lin2012) found that the number of hours in training, rather than the duration of experience of interpreting, was related to improving accuracy of interpretation. However, most interpreters have been trained to work in medical and legal settings (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Martell, Pazdirek, Caruth and Lopez2005) and in these settings the understanding, and relevance, of psychological constructs may not be emphasized.

Other studies have focused on the complex dynamics, and emotional reactions, that have been created by the presence of interpreters and their impact on the therapeutic process (e.g. Miller et al., Reference Miller, Martell, Pazdirek, Caruth and Lopez2005; Raval and Smith, Reference Raval and Smith2003; Tribe and Thompson, Reference Tribe and Thompson2009a). Additionally, there has been research into the difficulties in communication of empathy, experienced by therapist, during these three-way interactions (Pugh and Vetere, Reference Pugh and Vetere2009). Difficulties can be encountered by therapist, interpreter and clients within these relationships. These tend to relate to issues of trust, control and power (Brisset et al., Reference Brisset, Leanza and Laforest2013), which need to be negotiated and balanced within the three-way relationship.

Within the CBT field there is limited research into the impact of the use of interpreters on therapy outcomes; however, there is some indication that treatment of PTSD, facilitated through interpreters, can be as effective as intervention that does not require interpretation (d'Ardenne et al., Reference d'Ardenne, Farmer, Ruaro and Priebe2007; Brune et al., Reference Brune, Eiroá-Orosa, Fischer-Ortman, Delijaj and Haasen2011; Lambert and Alhassoon, Reference Lambert and Alhassoon2015). d'Ardenne et al. (Reference d'Ardenne, Farmer, Ruaro and Priebe2007) developed protocols for providing interpreter-facilitated CBT within a psychological trauma clinic with the aim of overcoming cultural and language barriers for trauma patients presenting for psychological therapy. This study has contributed to our understanding of working collaboratively with interpreters, and thus improving therapeutic outcomes, in the delivery of trauma-focused CBT. It has also added weight to the call for specific training of interpreters working within psychological services.

In a case study exploring the use of an interpreter in the treatment of a woman with depression and simple phobia within an IAPT service, Mofrad and Webster (Reference Mofrad and Webster2012) identified the complexity of ‘working as a triad’ but that the use of the interpreter enabled communication with this client, increasing cultural understanding. However, they concluded that with regard to using interpreters in IAPT there is a ‘deficit in high intensity training and lack of literature to support therapists’.

Even more pertinent to the current study, Costa and Briggs (Reference Costa and Briggs2014) conducted a qualitative study exploring the experiences of IAPT clients who had received therapy with the help of an interpreter. Their findings indicated three patterns of response: negative impacts on the therapy, the interpreter as conduit for therapy and the therapist and interpreter jointly demonstrating a shared enterprise. Their findings indicate that the roles, and functions, of interpreters as perceived by the client can be varied and they conclude that further research into this area is needed.

Challenges when working therapeutically with an interpreter can clearly exist. The potential for the client to develop their primary alliance with the interpreter, rather than with the therapist, has been highlighted as a concern for therapists in a number of studies (Raval and Smith, Reference Raval and Smith2003; Tribe and Morrissey, Reference Tribe and Morrissey2004; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Martell, Pazdirek, Caruth and Lopez2005).

However, supporting the assertion that the involvement of an interpreter can have a positive influence on the therapist and client experience, Tribe and Thompson (Reference Tribe and Thompson2009b) suggest that working through an interpreter can give the therapist more time to think, thus allowing them to be more reflective about their interventions. It has also been suggested that the interpreter can serve as a supportive presence for patients (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Martell, Pazdirek, Caruth and Lopez2005; Searight and Searight, Reference Searight and Searight2009).

Taking this appreciation further, Hamerdinger and Karlin (Reference Hamerdinger and Karlin2003) suggest that an interpreter's presence, and the complexity involved in this work, ‘allow for opportunities for transference and counter-transference that do not exist in dyads’, and that this opens the door to ‘work that is not possible using any other approach’.

With relevance to this study, it has been argued that the terms transference and counter-transference, which are rooted in psychodynamic therapies, are not used in the language of CBT. However, the experiences of negative cognitions, including schemas, that can create doubts and difficult emotional responses during CBT are not denied. How these are managed and taught in order to improve interpersonal effectiveness and balance in CBT programmes has been debated in the literature (e.g. Gilbert and Leahy, Reference Gilbert and Leahy2007; Prasko et al., Reference Prasko, Diveky, Grambal, Kamaradova, Mozny and Sigmundova2010). Consistent with the guiding principles of collaborative working, and maintaining a positive therapeutic relationship, Prasko et al. (Reference Prasko, Vyskocilova, Slepecky and Novotny2012) outline how supervision could be used to reflect upon these issues within CBT.

Given the complexities involved in delivering interpreter-facilitated therapy, including the potential for miscommunication and challenges in establishing therapeutic alliance, the British Psychological Society (BPS) has developed practice guidelines for psychologists working with interpreters in health settings (Tribe and Lane, Reference Tribe and Lane2009). However, it has also been suggested that more research is needed to clarify the roles and functions of interpreters during this collaborative working (Costa and Briggs, Reference Costa and Briggs2014).

Method

Design

This study employed a cross-sectional, qualitative methods design. A convenient, and purposive, sample of participants was recruited from current therapists working within a London NHS IAPT service. Semi-structured interviews were carried out with participants to explore their experience of working with interpreters in therapy. Data were analysed using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006).

Procedure and recruitment

Data relating to the use of interpreters within the IAPT service were accessed, via the agency that provided the interpreter service, for the 3.5-year period prior to the study. A total of 350 requests for interpreters were made to the local language agent during this period. These data enabled the retrieval of outcome data, from the Intranet Access Psychotherapy Patient Management System (IAPTUS), for those clients who completed assessment and treatment with the help of interpreters at both Step 2 and Step 3. A total of 137 clients were seen with interpreters; of these, 91 clients were assessed and seen for one to two sessions and then either discharged, signposted to other services or declined services. These ratios and use of care pathways are consistent with those who did not need interpreters at the time. A total of 46 clients completed CBT and GSH treatment and received between four and 26 face-to-face therapy sessions with a total of 707 assessments, or treatment sessions, being completed with an interpreter in attendance. These sessions were carried out, with the aid of an interpreter, in a total of 24 languages. The languages most required were Tamil, Turkish, Polish and Kurdish.

Participants

A total of thirteen therapists, who had experienced working with an interpreter to facilitate communication during CBT, or GSH interventions, were recruited to the study. Of these, seven therapists were PWPs trained in delivering Step 2 CBT interventions and six were cognitive behaviour therapists trained in delivering CBT and other high-intensity therapies. Eleven of the therapists were female and two were male. Four of the participants were from the BME community and could speak more than one language. Experience of working within the IAPT service ranged from 2 to 5 years. Table 1 presents the profile which describes their role in IAPT, the level and intensity of therapy carried out, as well as the number of sessions interpreted with each participant.

Table 1. Participant profiles and number of sessions interpreted

Procedure

Research interviews were arranged with each participant at a time convenient to them within the IAPT service offices. Prior to commencing the interview, confidentiality procedures were reviewed and written consent obtained. A semi-structured interview schedule was used to prompt open-ended questions regarding the participant's experience of working collaboratively with interpreters in therapy. All interviews were carried out by the lead author (L.T.) and interview times ranged from 30 to 60 minutes.

Data analysis

Interviews were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim. Thematic analysis was applied to the interpretation of the data. Thematic analysis (Braun and Clark, Reference Braun and Clarke2006) was chosen for its applicability across an array of epistemological, and theoretical, positions as well as its compatibility with both essentialist and constructionist models which characterize CBT. In the first stage of analysis, manual coding was carried out to develop familiarity with the data and to identify initial codes that were then reviewed and combined to create themes. During data analysis, the researcher consistently checked her interpretations against the interview transcripts guaranteeing that these were grounded and reflective of the data. Two of the participants, and a research supervisor, reviewed the interview data against the themes to check for consistency and to provide triangulation.

Transparency has become a prominent issue within qualitative research methods. A critical realist approach acknowledges the subjective role of the researcher in the construction of knowledge (Macleod, Reference Macleod and Hook2004) and that researchers are not passive containers in which data are dispensed (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz, Hesse-Biber and Leckenby2006). It is therefore noted that the lead author, responsible for data collection and analysis, is a psychologist with high-intensity CBT training working within the IAPT setting and has experience of working with interpreters in this setting. It is also noted that participants were drawn from the same professional setting and were known to the researcher.

Results

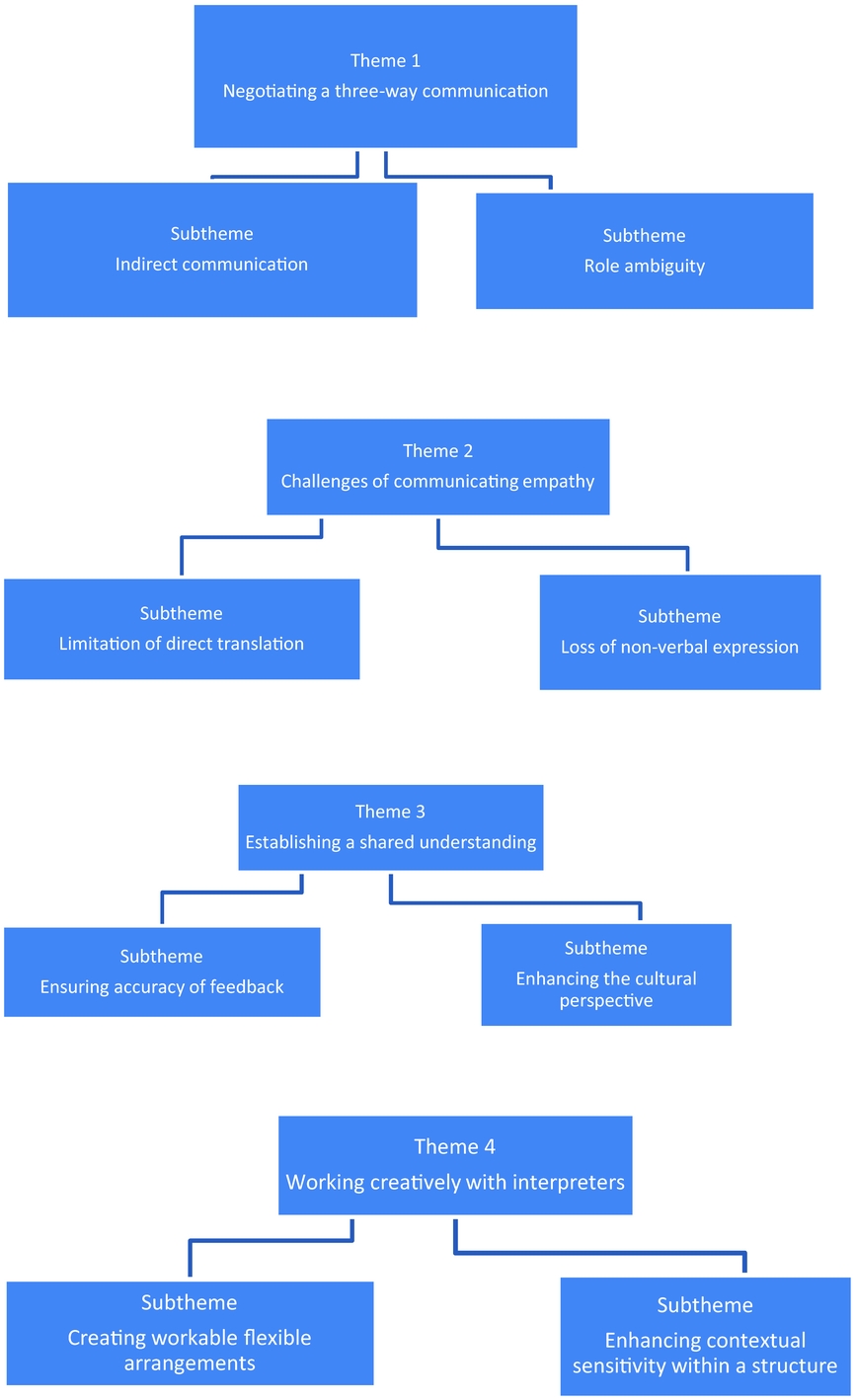

Following data analysis, four main themes representing both the challenges and new understandings that emerged during collaborative working with interpreters, were identified. These are as follows: negotiating three-way interaction, challenges in communicating empathy, establishing a shared understanding and creative collaboration with interpreters.

These themes, and their associated subthemes, are shown in Fig. 1 and are discussed below; direct extracts have been used to illustrate the connection between themes and data to enhance the transparency of the analysis.

Figure 1. Themes and subthemes

Negotiating a three-way interaction

The inclusion of an interpreter in the therapeutic process was seen as a significant change to the one-to-one communication traditionally experienced in individual therapy. Instead of the usual direct communication between therapist and client, this interaction was now being facilitated via a third person and this indirect communication required some adaptation.

(P2, Step 3): ‘They have their relationship with the clients, it is live, and there are two conversations.’

(P6, PWP): ‘They may share culture and same language; the client may see the interpreter as the person that is helpful.’

As well as practical concerns regarding interpreted therapy, including time and resource implications, participants expressed concern about the impact that interpreted communication may have on clinical care. In the IAPT context clinical responsibilities include assessing risks and making informed decisions about mental status and medical history. Clear communication is important for referral systems, and identification of appropriate intervention, within a stepped care model. Participants expressed concern that indirect communications may lead to misinterpretation and impair clinical outcomes.

Another subtheme related to a sense of ambiguity that some participants identified regarding roles within therapy, which led to feelings of uncertainty about engagement and collaborative working. This role ambiguity was particularly expressed by participants who delivered ongoing CBT interventions; their concerns were that this three-way communication could interfere with the therapeutic alliance, and interpersonal effectiveness, which is considered to be associated with good outcome.

The following accounts demonstrate how these concerns about engagement were expressed:

(P1, Step 3): ‘The person might not feel listened to, the third person is quite part of the equation, you're never sure, you're never quite sure if the engagement is happening between them and the interpreter rather than them and you, you're never sure who is building rapport.’

(P5, Step 3): ‘The therapeutic relationship changes as the clients speak directly to the interpreter they may become overfriendly as they are the ones having the dialogue and you being interpreted for.’

Participants also expressed a concern that lack of clarity around roles may lead to a power imbalance created by the language shared by the therapist and interpreter, as illustrated in the following extract:

(P12, PWP): ‘Client feels dominated by both you guys speaking English, also you can feel disempowered as you suggest things to do whereas you do not have the language to do it. You have this language that they do not have. It is about working out how we use power in guided self-help.’

In this abstract the imbalance of power within the interaction is made visible and its effects, and intentions to respond, are articulated. There is an acknowledgement that the experience of not being able to speak a common language can be disempowering and lead to feelings of being excluded for both client and therapist.

Due to uncertainties about role and relationship within the therapeutic encounter some participants experienced the interpreter as assuming a role as co-therapist, as expressed below:

(P9, PWP): ‘Sometimes interpreter gets too involved thinking that they have to be co-therapist and that can be difficult to manage. It disrupts the engagement as everything you say has to be interpreted.’

(P7, PWP): ‘The hardest thing is the interpreter takes on the role of the clinician.’

(P5, Step 3): ‘If the interpreter has no communication skills in working with someone therapeutically then it becomes hard while I'm not saying they should be co-facilitators.’

In response to their concerns regarding the potential for miscommunication and role ambiguity, most participants expressed a preference for a linguistic model of interpreting, in which the interpreter translates the words of the therapist while minimizing their relationship with the client. In this study this preference seemed to be motivated by the need for accurate interpretations to make informed clinical decisions and risk management.

Participants also identified the challenges for interpreters working in this setting and identified a need for additional training for interpreters to support their understanding of their role within the therapeutic process.

Challenges of communicating empathy

Participants identified that working with an interpreter presented additional challenges to communicating understanding, and empathy, which are considered crucial aspects of developing the therapeutic alliance. The limitation of direct translation within interpreter facilitated triad was highlighted.

(P12, PWP): ‘Displaying warmth and empathy can be difficult and feel slowed down, you don't know if you have responded to everything.’

Despite a preference for a linguistic model, participants in this study perceived the medical, non-involved approach of the interpreter as contradicting their empathic stance as therapists. When it was felt that the interpreter was unable to express the intentions of the therapist, participants went to greater efforts to express these to the client themselves.

(P9, PWP): ‘When they interpret it they just say it, it's not communicated with the same warmth and genuineness . . . this is when you need to extend yourself, to express your genuine understanding.’

Participants drew upon their ability to demonstrate empathy non-verbally in attempts to match what they could not communicate verbally. However, concern about their non-verbal expressions of warmth and empathy being lost within the process was highlighted as another sub-theme.

(P13, PWP): ‘I know I choose my words very carefully so that I don't come across as harsh or judgemental and show this with my hands and voice, but I'm not always sure if the interpreter does the same with their words.’

(P8, PWP): ‘It could be like any medical appointment, here I'm sitting with facial expression trying to communicate empathy if the interpreter communicates that with a blank face then we cannot communicate empathy through the interpreter.’

Participants indicated that therapy was enhanced if the interpreter was able to mirror the therapist's empathic approach.

(P4, Step 3): ‘Interpreters play a role in positive outcomes. . . If an interpreter has an understanding and displays empathy. . . rather than those that are business like, while I am not advocating that interpreter becomes therapist.’

Participants’ recognition of the complexity of the interpreter's role, in both accurately conveying content and meaning within the communication whilst also mirroring the emotional intent of the therapist, is highlighted here.

Establishing a shared understanding

Within CBT and guided self-help, acknowledging the client's feedback is important in order to confirm a shared understanding of their difficulties, which in the culture of collaborative working leads to the creation of jointly constructed solutions. Participants in this study felt that the interpretation process refereed this shared understanding through adding or omitting information.

In the first sub-theme the need to ensure accuracy of feedback from the client is highlighted. Concerns that shared understanding may be lost if this accuracy of feedback was not negotiated fully were expressed, as highlighted by the extracts below.

(P1, Step 3): ‘I was not always confident in the understanding . . . If we are not clear that the interpreter asked what we said we don't know what is coming back.’

(P7, PWP): ‘You are not sure if the client understands. Sometimes it's difficult to give the information you want to give, and it's difficult to get the information you want.’

(P2, Step 3): ‘Using an interpreter restricts what you can do in therapy. Understanding seems to be the bit that is missing.’

There were also concerns that the understanding, and assumptions, of the interpreter were mediating the shared understanding between client and therapist.

(P13, PWP): ‘You never know if you have responded to the assumptions of the interpreter or the client.’

The perceived challenges to developing a shared understanding was not only expressed in relation to spoken language but also with regard to written materials used during sessions. In IAPT therapists are required to use questionnaires for measuring and monitoring outcomes. As explained by participants in this study, sometimes these have to be interpreted from English due to unavailability of relevant measures in other languages. Fears about meanings being lost in translation were motivated by concerns about reliability, and validity, of these interpreted measures.

(P1, Step 3): ‘Unless you speak the language yourself, we don't know how well these questionnaires have been translated. These might not be authentic or clearly translated, but then it's part of working with the interpreter.’

(P2, Step 3): ‘Sometimes written stuff is the challenge, not all measures are translated correctly or in the right dialect, and resources are not always available.’

In a second sub-theme it was recognized that the interpreter could bring knowledge, and insight, to the therapeutic process that could enhance the cultural perspective. Some participants highlighted how the interpreter's ability to communicate concepts in a culturally relevant way could play a key role in mediating their shared understanding.

(P7, PWP): ‘The client is not just looking to the interpreter for the word, they are looking for understanding.’

It was also recognized that this could pose significant challenges for the interpreter in terms of both understanding the psychologically specific terminology used and finding ways to communicate this to the client in a language which may not have a direct translation.

(P2, Step 3): ‘It's not the word itself it's the context and meaning, because of the terminology and words used in CBT. Translating the words do not necessary make things meaningful.’

(P11, PWP): ‘Sometimes interpreters are able to use their culturally specific metaphors for example “heart-aching”. Some words do not exist in other languages; the other main challenge is not being able to have the resources, the language and techniques.’

Shared understanding between patients and health care providers is often difficult even where language and culture are not barriers. A client's understanding of their health problems is unique and influenced by a combination of different factors, which include local knowledge and their belief-systems.

However, it is noted that there remains an inevitable uncertainty with regard to shared understanding and alliance:

(P9, PWP): ‘The client and I will never know whether or not we had a shared understanding. No one will ever know.’

Creative collaboration with interpreters

While the clients who required interpreted therapy were often experienced as having more complex presentations, and multifaceted problems, therapists were willing to learn new ways of collaborative working, which included the interpreter as part of the therapeutic process. In the following accounts, therapists shared what they had experienced as helpful when working collaboratively with interpreters within the IAPT service.

(P5, Step 3): ‘There is the satisfaction that no one is discriminated or excluded.’

(P10, Step 3): ‘I think we could encourage people who cannot speak a language to attend our workshops and group therapy, we can be inventive, maybe the interpreter can be outside the room and interpret via ear piece etc.’

In these abstracts therapists were suggesting other ways of dealing with communication barriers so that clients who could not speak English could be included in other available CBT interventions. There was a sense of learning from practice as shown in the extracts:

(P9, PWP): ‘It is still a work in progress but I have learned a lot.’

(P8, PWP): ‘. . . my experience is that it's not easy, it's more difficult than just the consideration of time. . . you get a lot of complex trauma stories, money problems, psychosocial problems.’

(P12, PWP): ‘. . .these clients are more severe and sometimes they have not had the opportunities that most clients I have assessed with PTSD had.’

Participants acknowledged the complex needs of these clients and expressed a willingness to adapt and engage. For example, the duration of session for clients needing interpreters were usually longer: up to 90 minutes for Step 3, face-to-face, CBT and up to 60 minutes for Step 2, face-to-face GSH.

Participants also expressed a desire to promote shared understanding, and the challenges they identified encouraged curiosity and creative methods of engaging. The following extracts demonstrate how participants tried to develop collaborative approaches:

(P13, PWP): ‘You end up very structured because you have to think about what you say, it becomes less collaborative but there are ways of getting over that. . . Sit on the desk together, look at something together, and check cultural relevance and values with patient and interpreter.’

(P9, PWP): ‘It's about being creative, whatever you say draw a picture, act it out, be on your toes.’

In these creative examples the interpreter is included and there seemed to be a change in the conceptualization of collaborative working as noted in the following abstracts:

(P10, Step 3): ‘If both you and interpreter are prepared to get your hands dirty, drawing or even writing on the white board whatever you're trying to say in their language, it's helpful.’

(P13, PWP): ‘You end up very structured because you have to think about what you say, it becomes less collaborative but there are ways of getting over that.’

There is still an appreciation of the structured approach espoused by CBT theory. However, the theme of sitting together, and working collaboratively, was repeated often by participants as an attempt to improve shared understandings.

Consideration of contextual issues that could impact on this work was also articulated. Specifically, cultural factors were acknowledged and participants suggested ways in which these understandings could be promoted within the interpreted therapy setting. These are highlighted in the following abstracts:

(P6, PWP): ‘Sometimes we worry so much about the client having to be seen by a therapist from the same culture.’

(P2, Step 3): ‘Sometimes clients are not comfortable with same community and same culture interpreters as they worry that they may reveal some stuff about them, working with someone outside their culture may make the relationship with therapist stronger.’

(P11, PWP): ‘Make sure that the client is happy bringing culturally relevant material; don't just make assumptions that people want to work with people from their backgrounds, understanding is key.’

Discussion

In this study four inter-related themes were identified; these include: challenges and contradictions of working in triad relationships, lack of shared understanding, challenges of expressing empathy through the interpreter and new ways of collaborating creatively with interpreters. While similar themes have been identified in other studies (e.g. Farooq and Fear, Reference Farooq and Fear2003; Pugh and Vetere, Reference Pugh and Vetere2009; Tribe and Thompson, Reference Tribe and Thompson2009a) the theme of shared understanding has not been as explicit, and recurring, as in this study. It is noted that participants’ accounts also revealed some contradictions, and competing demands, with regard to the roles and functions of interpreters in their work context. This has implications for practice.

The experience of negotiating the three-way relationship was described as potentially anxiety provoking with issues of role ambiguity, and imbalance of power, identified. These initial responses, and expressions of doubt in working with interpreters, have also been reported in earlier studies. For example, in a qualitative study of the experiences of mental health practitioners, Raval and Smith (Reference Raval and Smith2003) found a range of negative feelings expressed in relation to working with language interpreters. These included difficulty establishing a co-worker alliance with the interpreter, and concern that the interpreter forms the primary alliance with the client and takes over their work in session. Many participants in the study reported feelings of anxiety, loss of control, role ambiguity and powerlessness.

Similarly, Miller et al. (Reference Miller, Martell, Pazdirek, Caruth and Lopez2005), in a study of therapists and interpreters working with refugees, found that interpreters formed powerful relationships with the clients and that therapists experienced feelings of exclusion, self-consciousness and anxiety that their work was being evaluated by the interpreter. In CBT practice a strong therapeutic relationship between therapist and client is valued as it promotes collaborative working which is considered central to efficacy and positive outcomes (Beck, Reference Beck1995; Roth and Pilling Reference Roth and Pilling2007). It has also been stated in previous studies that effective integration of interpreters into treatment requires that the alliance between interpreter and therapist is strong and prioritized (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Martell, Pazdirek, Caruth and Lopez2005; Searight and Searight, Reference Searight and Searight2009). It is important to note that in the current study, as practitioners became more creative and flexible in their collaborative working with clients and the interpreter, these feelings changed to ‘work in progress’ and ‘possibilities’, as expressed in their accounts.

Although most participants reported knowledge of the BPS guidelines for working with interpreters (Tribe and Thompson, Reference Tribe and Thompson2008, Reference Tribe and Thompson2011), their accounts of creative collaborations indicate that they drew heavily upon their own professional experiences of CBT and GSH to develop their knowledge and skill when working with interpreters. It is also noted that their conceptualization of collaborative working with the interpreter appeared to change through experience. The accounts of the participants show a change in the conceptualization of collaborative working as they became more creative. In the absence of a common language, the inclusion of an interpreter, in these activities, was conceptualized as enhancing the therapist's knowledge of the client's difficulties and distress.

Previous studies have noted that even within other therapeutic models, therapists resort to more behavioural approaches when communication is facilitated with interpreters (Raval and Smith, Reference Raval and Smith2003). Similarly Lopez et al. (Reference Lopez, Rees and Castro2014) contend that, through its focus on the interactions between observable processes, which include behaviours, feelings and physical sensations, CBT seems to be a much preferred model when communication is facilitated with the help of the interpreter. Mofrad and Webster (Reference Mofrad and Webster2012) also suggest that behavioural interventions in CBT, such as exposure techniques, are easier to deliver with the aid of an interpreter than some other therapeutic approaches. In CBT and GSH therapists demonstrate both counselling skills, which include demonstrating empathy and compassion, in addition to a range of behavioural interventions, which enhance other ways of learning as noted in these studies.

Similarly in this study the participants’ prior knowledge of CBT and GSH, seemingly taken for granted in their first experiences of working with interpreters, contributed to their collaborative working with interpreters. In their accounts of working creatively with interpreters the participants spoke about being ‘more structured’ and ‘think and plan what to say and do’. These notions are consistent with the CBT model which is a ‘formula driven, goal oriented and structured approach’ (Beck, Reference Beck1995; Roth and Pilling, Reference Roth and Pilling2007). This planning and structuring of sessions include thinking about the language, terminology and metaphors as well as resources, which include formulations and worksheets to be completed between sessions. These tools were shared, and appropriate terminology and meanings discussed, with the interpreter prior to sessions. This flexible approach demanded much longer sessions, varying up to a maximum of 60 minutes for GSH and up to 90 minutes for face-to-face CBT.

As noted for instance in this extract, ‘Sit on the desk together, look at something together, check cultural relevance and values’, the strengths, and resourcefulness, of the interpreter was seen as adding value to this work. The shift in the participant's conceptualization of collaborative working included changing the triangular seating arrangement to sitting together, in order to encourage more explicit, and interactive ways, of working to facilitate communication and shared understanding. The issue of longer sessions and flexibility in sitting arrangement has also been noted in previous studies and has implications for working guidelines with interpreters in CBT (d'Ardenne et al., Reference d'Ardenne, Farmer, Ruaro and Priebe2007; Mofrad and Webster, Reference Mofrad and Webster2012).

As shown in their accounts, participants had an awareness of how contextual issues like history and culture could impact on meaning within the therapy setting. They also expressed concerns and respect about clients’ choices and preferences. By virtue of their background knowledge of the cultural, political and historical aspects of the client's experiences the interpreter may be able to assist with shared understandings of the client's distress (Drennan and Swartz, Reference Drennan and Swartz2002).

Likewise, Pugh and Vetere (Reference Pugh and Vetere2009) adds that these shared understandings are important in improving empathic engagements. As the interpreter often shares an ethnic, and cultural, background with the client, they may be a source of background information and have a role as a ‘cultural resource of information’ (Drennan and Swartz, Reference Drennan and Swartz2002; Tribe and Morrissey, Reference Tribe and Morrissey2004; Tribe and Thompson, Reference Tribe and Thompson2008; Dubus, Reference Dubus2016). In revealing the self-perceptions of interpreters working in health settings, Dubus (Reference Dubus2016) describes how interpreters view their roles, offering both support and cultural understanding; equally describing their roles as multifaceted. However, it is noted that clients may not always feel comfortable working with someone from a shared background, due to concerns about perceptions, and beliefs, which may limit their open expression. In this study, two of the participants, who could speak more than one language, shared how some clients had rejected appointments with them because their names indicated shared ethnic background as them, although not directly known to them. Pugh and Vetere (Reference Pugh and Vetere2009) also found that clients were not always able to volunteer information easily when they shared the same cultural background with interpreters.

Within CBT and GSH, acknowledging the clients’ feedback is important as it can confirm, and enhance, a shared understanding of the client's difficulties. This shared understanding can be complex, due to differences in knowledge systems between the client and therapist, even if they share a language (Beck, Reference Beck1995). Participants in this study also expressed concern that shared understanding between client and therapist was being compromised by the interpreting process, either due to difficulty with direct translation or by the influence of the interpreter's own assumptions. Concerns about information being lost in translation, with omissions, or additions, altering the message, have been identified in previous studies (Farooq and Fear, Reference Farooq and Fear2003; Pugh and Vetere, Reference Pugh and Vetere2009; Tribe and Thompson, Reference Tribe and Thompson2009a). Such fears are not unfounded as errors, omissions and misunderstandings in interpreted encounters, both in medicine and mental health, are well documented in research and literature (Westermeyer, Reference Westermeyer1990; Farooq and Fear, Reference Farooq and Fear2003; Searight and Searight, Reference Searight and Searight2009; Flores et al., Reference Flores, Abreu, Barone, Bachur and Lin2012).

Within IAPT services, communicative encounters in CBT, and GSH, are by both tasks and processes, which requires ‘therapeutic pragmatism’ (Rankin, Reference Rankin1999) and a critical use of knowledge by the therapist to make clinical decisions. The importance of clinical responsibilities during this process has been stressed in most guidelines and studies. These guidelines outline the practical arrangements and also stress that the practitioner should take charge in ensuring effective communication during the session (Westermeyer, Reference Westermeyer1990; Searight and Searight, Reference Searight and Searight2009; Tribe and Thompson, Reference Tribe and Thompson2009b). There have been reports of interpreters editing, and using words which change meaning in medical interpretation, which impact on clinical decisions (Flores et al., Reference Flores, Abreu, Barone, Bachur and Lin2012).

Therapists working within IAPT are also required to use questionnaires for measuring and monitoring outcomes for all clients. Therefore, collaborative working includes interpreting questionnaires, where language-specific ones are not available. It is noted that it is difficult to achieve linguistic equivalence when psychometric measures, and other validated tools, are interpreted. There can be problems of relevance, and potential bias, when psychological constructs, originating from western values and understanding of health and illness, are directly interpreted to other languages (Searight and Searight, Reference Searight and Searight2009). Participants in this study expressed concern that, due to the unavailability of relevant assessment tools in other languages, measures designed for western populations were being translated in sessions. They expressed anxieties originating from the conflict between requirements to measure outcome, and produce evidence of therapeutic change, and concerns that interpretation of measures that were not validated for the population would provide inaccurate assessment results. The experience of the therapists in this study raises interesting questions regarding the application of models of interpreting within the therapeutic setting.

Participants in this study tended to express a preference for a linguistic model that emphasizes verbatim translation and neutrality of the interpreter. This preference seemed to be motivated by concerns about the interpreter becoming overly involved, and exceeding their remit by adopting a role of ‘co-therapist’, as well as their prioritization of the need for accurate interpretations to make informed clinical decisions and assess risk management. Dubus (Reference Dubus2016) has noted that interpreters are taught to channel communication with emphasis on neutrality and accuracy and are often not seen as part of a team during this work.

However, there were some contradictions with regard to styles of interpretations in this study. Participants did acknowledge the limitations of this linguistic model with concerns that the application of direct translation may hinder the development of shared understanding and expression of empathy. The use of a literal linguistic model has been previously criticized for creating de-contextualized communication, lacking in richness and meaningfulness (Tribe and Thompson Reference Tribe and Thompson2009a).

Difficulties in developing empathic connections with clients has been identified in other studies, where different psychotherapy models were used (e.g. Raval and Smith, Reference Raval and Smith2003; Pugh and Vetere, Reference Pugh and Vetere2009). In the current study there were concerns that empathic conversations were not being communicated effectively to allow shared understandings and engagement. These concerns led participants to focus more on the use of non-verbal communication to try to demonstrate empathy, and compassion, to the client in the absence of a common verbal language. Interpersonal effectiveness is an important aspect in enhancing engagement in CBT (Beck, Reference Beck1995; Roth and Pilling, Reference Roth and Pilling2007).

In differentiating between how empathy is expressed in other counselling models, versus the CBT model, Thwaites and Bennet-Levy (Reference Thwaites and Bennett-Levy2007) contend that empathy should be understood as a much broader aspect which includes the relevant communication skills of compassion, and validation. It is argued that the focus of empathy should be on understanding a client's circumstances and experiences, demonstrated in attitude, as well as communicated verbally and non-verbally. In IAPT services, where people present with a range of difficulties, including barriers in articulating their needs directly, this contextual sensitivity for understanding empathy seems appropriate. Both CBT and GSH are intervention based therapies where ability to validate a client's experience, and show compassion, is important (Thwaites and Bennet-Levy, Reference Thwaites and Bennett-Levy2007).

It is recognized that, within a therapy setting, a shift away from a linguistic model may be required. A constructivist model, whereby the interpreter conveys the meaning of the words, and their accompanying emotion, rather than giving a verbatim translation, may be more appropriate. This model acknowledges cultural factors in communication and the fact that some words, or concepts, do not lend themselves to direct translation. Developing this approach further, the cultural broker model (Tribe and Morrissey, Reference Tribe and Morrissey2004; Searight and Armock, Reference Searight and Armock2013) also requires the interpreter to provide cultural education and context to the client.

Implications for practice and conclusions

As 40% of clients referred and assessed in IAPT also have physical health symptoms, related to a long-term condition (NHS England, 2016), in addition to suffering from depression and/or anxiety, communication is key to providing appropriate referral systems and care pathways.

Limitations and future research

It is noted that one of the limitations of this study is its use of a small, purposive sample which may reduce the generalizability of the findings. It is also outside of the scope of this study to report on outcomes of the interpreted therapy reflected on by participants. Future research, which aims to delineate models and processes applied within interpreted therapy settings, in order to identify best practice, is warranted. This further research should employ both quantitative, and qualitative, research methods for triangulation, and convergence, of evidence. As identified in the accounts of the participants in this study, it is sometimes ‘hard to hear the voice of the client in these interactions’. Therefore, there is a need for more research that explores the experiences of clients who have received interpreted CBT and GSH, to expand upon the limited research that has been done in this area (e.g. Costa and Briggs, Reference Costa and Briggs2014). To complement previous findings from the literature (e.g. d'Ardenne et al., Reference d'Ardenne, Farmer, Ruaro and Priebe2007) further research should also endeavour to understand the experience, and perspective, of interpreters working within CBT services and other therapeutic contexts.

Main points

-

(1) The study contributes towards an understanding of knowledge and skills of collaborative working with interpreters during CBT and GSH within an IAPT setting.

-

(2) It is recommended that interpreters working in this context should have some knowledge of mental health, basic knowledge of CBT and good interpersonal skills which include communication and ability to display empathy.

-

(3) This study has highlighted how the principles of working in CBT, which include collaborative, working, joint agenda setting and therapeutic guided activities, can be used creatively, and flexibly, with interpreters.

-

(4) This study has also highlighted importance of helping both therapists and interpreters to develop interpersonal and relational skills, which help them to be more attuned, and perceptive, in therapeutic interactions.

-

(5) The importance of being adaptable, and working creatively, has been an important theme. This includes having longer sessions, to make space to speak to the interpreter before and after sessions, as recommended in the BPS guidelines (Tribe and Lane, Reference Tribe and Lane2009), as well as non-rigid seating arrangements allowing interactive working with resources.

-

(6) In line with the study of Pugh and Vetere (Reference Pugh and Vetere2009), a reconsideration of the therapist's understanding of empathic conversations when working with clients across cultures, and with interpreters, is needed.

-

(7) Clear understanding by the therapist, and interpreter, of their roles and functions has potential to reduce misunderstanding and maximize therapeutic outcomes. The importance of making these roles, and power dynamics within relationships, more explicit during CBT and GSH has been indicated (d'Ardenne et al., Reference d'Ardenne, Farmer, Ruaro and Priebe2007).

-

(8) Taken together the experience of the participants in this study suggests that, rather than being constrained by a particular style of interpreting, a shift between models may be necessary. This experience, alongside evidence from previous studies, reinforces the importance of using trained interpreters (Flores et al., Reference Flores, Abreu, Barone, Bachur and Lin2012; Gray et al., Reference Gray, Hilder and Stubbe2012).

-

(9) Training of interpreters plays an important part in helping to facilitate communication, as shown by the outcomes of work with CBT and PTSD (d'Ardenne et al., Reference d'Ardenne, Farmer, Ruaro and Priebe2007). This study supports the importance of training and supervision for staff working with interpreters, as well as the requirement for additional training for interpreters specific to working within this therapy context.

-

(10) Supervision, within their CBT practice, can support practitioners to explore their expectations, and uncertainties, related to this work. As it is the responsibility of the psychological practitioner to ensure that their communication is effective (Tribe and Thompson, Reference Tribe and Thompson2008), more continuing professional courses are recommended.

Ethical approval

This study was registered with and approved by the Research and Development Department of Oxleas NHS Foundation Trust.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the therapists who shared their experience, and also acknowledge the support of colleagues and management including Anthony Davies, Katy Grazebrook, Thelma Dabor and the research work team Stuart Pack, Harpreet Sanghara, Penny Moyse and Dr Erin Tehee.

Declaration of interest

None.

Learning objectives

-

(1) To develop an overview of working with interpreters in CBT and guided self-help (GSH) within the IAPT stepped-care model.

-

(2) To understand the relevance of language interpreters within the IAPT service.

-

(3) To consider the experience of practitioners working in collaboration with interpreters to facilitate communication in assessment and treatment using CBT.

-

(4) To identify how collaborative working with interpreters could be improved in IAPT.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.