No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

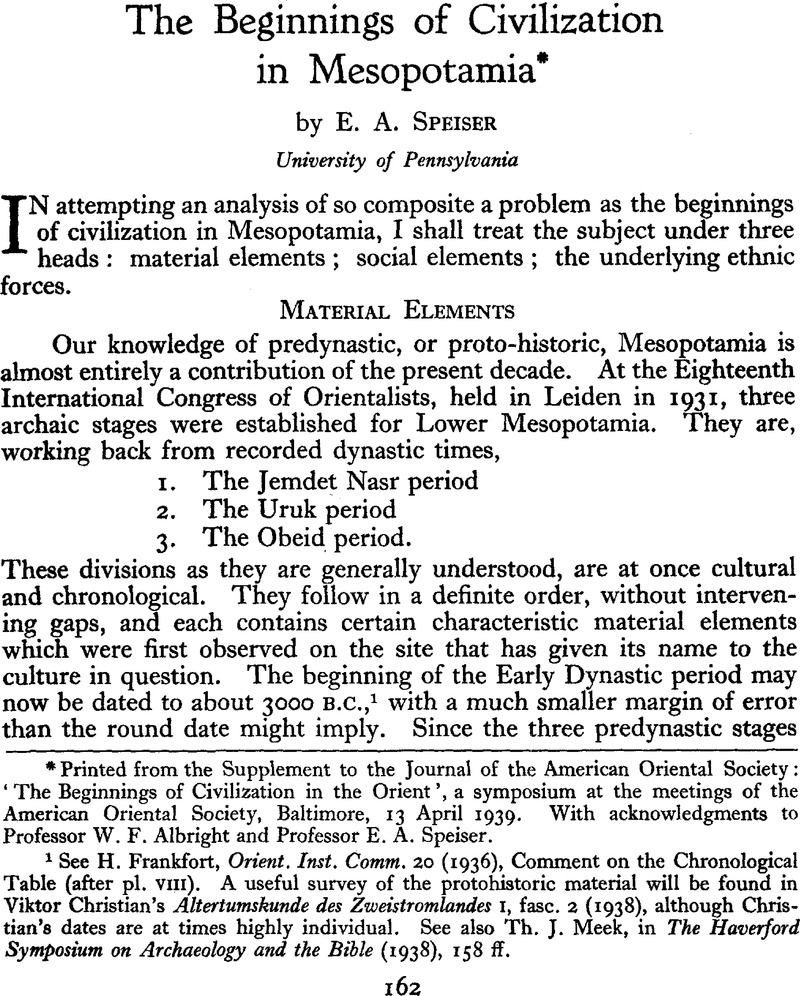

The Beginnings of Civilazation in Mesopotamia*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 January 2015

Abstract

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Antiquity Publications Ltd 1941

References

* Printed from the Supplement to the Journal of the American Oriental Society: ‘ The Beginnings of Civilization in the Orient’, a symposium at the meetings of the American Oriental Society, Baltimore, 13 April 1939. With acknowledgments to Professor W. F. Albright and Professor E. A. Speiser.

1 See H. Frankfort, Orient. Inst. Comm. 20 (1936), Comment on the Chronological Table (after pl. VIII). A useful survey of the protohistoric material will be found in Viktor Christian’s Altertumskunde des Zweistromlandes I, fasc. 2 (1938), although Christian’s dates are at times highly individual. See also Th. J. Meek, in The Haverford Symposium on Archaeology and the Bible (1938), 158 ff.

2 e.g. Uruk, archaic II-XVIII.

3 See above, note I.

4 That is to say, they are earlier than the deepest stratified deposits known from Mesopotamia. The stage in question has been reported from J. Garstang’s excavations at Jericho, and may be anticipated from his discoveries at Mersin.

In grouping together the Halaf and Samarra deposits I have had in mind only their relative chronology. On contextual grounds Samarra proves to be an early phase of the Obeid-Susa I group.

5 I would compare, for example, the motives published by N. G. Majumdar in Mem. of the Arch. Survey of India 48 (1934), pl. XXXVIII, 1-8 (called to my attention by Dr Marian Welker) with Gawra XIII ; see provisionally BASOR 66, 11.

6 For the figurines from Ur see L. Legrain, Gazette des Beaux-Arts Oct., 1932, p. 142 ; for Gawra there are stamp seals from Levels XI (post-Obeid) and xm which show an analogous treatment of the human figure with similar distortion of the head ; for Susa, cf. E. Pottier, Mém. de la Délég. en Perse 13 (1912), fig. 129.

7 For the differences between north and south which were apparent before the discovery of Gawra xm see M. E. L. Mallowan’s summary in Excavations at Tell Arpachiyah (1935), 70.

8 BASOR 66, 12.

9 A. Falkenstein, Archaische Texte aus Uruk (1936), 3. Although Uruk Ivb may be assigned on internal grounds to the Jemdet Nasr period, the required stage of transition from cylinder seal to tablet makes it necessary to put the process back to the end of Uruk times.

10 4. Vorl. Bertcht, Uruk (1932), 44.

11 See H. Frankfort, Cylinder Seals (1939), 224 ff.

12 The origin of Egyptian writing can scarcely be viewed in any other light. Its ultimate, though indirect, dependence on Mesopotamian writing is indicated by the following considerations. There are hundreds of Mesopotamian tablets from predynastic times as against the single possible instance of the Lion Hunt palette in Egypt with its two written symbols. (On this subject see H. Ranke, Heid. Ak. Wiss, 1924-25, 3 Abh.). According to Siegfried Schott (in Kurt Seine’s Vont Bilde sum Buchstaben [1939] 82) there is nothing in the Egyptian system of writing that points to a long period of development, whereas the evolution of Mesopotamian writing is abundantly illustrated from its very beginning. Moreover, the cylinder seal (admittedly of Mesopotamian origin) provides the link between picture and script ; and Mesopotamian economy (which differs markedly from Egyptian economy in historic times) furnishes an all but automatic explanation for transforming elements of design into elements of script (Falkenstein, op. cit. 32-3, 47). Finally, there is ample evidence of contacts between Mesopotamia and Egypt at the time of the evolution of Mesopotamian writing (A. Scharff, Zeit.f. äg. Spr. 71.89 ff.) But all this indicates no more than that the idea of writing was borrowed by Egypt (for this possibility see Schott, op. cit. 81). In form, the two scripts are strictly independent. Both are based on native artistic elements and the derivative scripts are as different as the respective art styles of Mesopotamia and Egypt.

13 cf. Journ. American Oriental Society, 1938, LVIII, 672-3.

14 A considerable time lag is involved, for example, in the spread of the ‘ chalice ware ‘ from Central Persia to the Nineveh area. On the other hand, the diffusion of the cylinder from Lower Mesopotamia required comparatively little time to reach Elam and Syria.

15 On the possible western origin of these outsiders further information may be expected from Garstang’s excavations at Mersin.

16 Gawra has yielded a charred impression of a stamp seal with an excellent design of an ibex, clearly datable to Halaf times. On the problematical date of the cylinder from Chagar Bazar (Iraq 3, pi. i, 5) see Frankfort, Cylinder Seals 228.

17 Gawra XI-VIII must be treated as a separate culture province in spite of the links with Uruk VI-IV, which testify to the chronological relationship of the two areas. Von Soden has proposed the term ‘ Gawra culture ‘ for the northern province (Der alte Orient 37 1-2, p. 9), but his archaeological interpretation of the culture in question is wholly inadequate.

18 I am referring here only to the polychrome geometric decoration of the period. For the naturalistic elements, as represented in the later Diyala ware, the source must be sought in the Susa 11 group, to use Frankfort’s definition of it. (Archaeology and the Sumerian Problem [1932] 69).

19 Hence the many close ties between the Hurrians and the Hebrews as against the less substantial cultural connexion between the Hebrews and the neighbouring Egyptians. The traditional opposition of the Hebrews to the Egyptians may indeed be viewed in the same light.

20 Archaische Texte ans Uruk.

21 Based on the inner evidence of the script ; cf. ibid. 25-6. For the bearing of the cylinder seals see also Frankfort, Cylinder Seals 1.

22 cf. e.g. Urukagina, Cones B and C, cols, XI-XII (See now the article of B.A. van Proosdij in the Koschaker Festschrift [Studia et Documenta 11 ; Leiden, 1939] 235 ff.)

23 §7 ; cf. M. Schoor, Vorderasiatische Bibliothek 5 (1913) XIII.

24 It is worthy of notice that the Hurrian and Hittite syllabaries rest on a prototype which antedates the Dynasty of Hammurabi; cf. JAOS 58, 189, note 68.

25 See A. Götze, Kleinasien (1933) 125.

26 cf. A. Poebel, AfO 9 (1933-4), 250-1. The influence of Sumerian on the ‘classical’ dialect of Hammurabi Akkadian is stronger than is generally recognized. A good illustration is furnished by the i-form of Akkadian as interpreted by Goetze, JAOS 56. 333.

27 cf. B. Meissner, Babylonien und Assyrien 2, 328.

28 Note, e.g. the individualizing elements in Susa I, the Nineveh area, and Lower Mesopotamia in Obeid times which tend to break down the underlying cultural relationship of these three regions.

29 See the monograph of W. M. Krogman in Or. Inst. Pub. xxx (1937), 213-85

30 Archaeology and the Sumerian Problem 40 ff.

31 AJA 37 (1933), 459 ff.

32 The stamp seals from Gawra VII-VIII, published in my Excavations at Tepe Gazera I (1935), pls. LVI-VIII, can now be supplemented by a large number of seals and impressions from the earlier levels. Their cumulative evidence is to the effect that nothing comparable in style to the seals from Uruk IV and later is present at Gawra until the very end of the Uruk period. In other words, the glyptic style that is characteristic of the Sumerians does not begin to affect the north until the Sumerians had demonstrable contacts with the south.

33 Frankfort’s argument that the Sumerians were ‘ the earliest occupants of the valley of the Two Rivers ‘ rests on the premise ‘ that the continuity in the material culture of Mesopotamia may best be understood as based on a similar ethnic continuity which, in view of the later stages of the development, we have to call from the very beginning Sumerian ‘ (op. cit. 46). The first part of this proposition is self-evident ; ethnic survivals as transmitters of material accomplishments may safely be assumed from the beginning of chalcolithic times at least. But the conclusion does not follow at all. One could say with equal right that the Hurrians of the Kirkuk area were its original population because the texts of the second millennium use the script and reflect many legal and administrative ideas of the preceding millennium. What is characteristically Sumerian in Lower Mesopotamia turns out to strain the normal continuity instead of maintaining it. The underlying influences are eccentric rather than concentric. The Sumerians were later arrivals, therefore, who injected new and vital elements into the inherited civilization.