1 Introduction

In 1960, Frene Ginwala, a United Kingdom-trained lawyer, went into exile with hundreds of other African National Congress (ANC) activists after the South African government instituted a ban on the ANC and police killed scores of protesters during what became known as the Sharpeville Massacre. During her thirty years in exile, Ginwala became indispensable to the ANC; she helped develop secret routes to move ANC activists across the South African border, including Oliver Tambo and Nelson Mandela, and advanced key ANC party platforms, including the organization’s position on gender equality. She also traveled around the globe, educating others on the organization’s anti-apartheid struggle.Footnote 1 Ginwala returned to South Africa in 1990 when the ANC ban was lifted and took up a prominent role in the ANC Women’s League. In this role, she pushed for women to be included in the negotiations to end apartheid and the subsequent transition process, and for women’s interests to be integrated into the new constitution (Hassim Reference Hassim2002). She carried on these priorities after she was elected to parliament in 1994 and became the first speaker of the post-apartheid National Assembly. She repeatedly connected the empowerment and advancement of women to liberation priorities and prospects for a peaceful democratic transition (Geisler Reference Geisler2000).

Ginwala was not an aberration among former ANC activists. Women who participated in noncombat roles, like Ginwala, and those who participated in Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the ANC’s armed wing, became mainstays in South African politics after the transition (Geisler Reference Geisler2000). Like Ginwala, many other female politicians from the ANC pushed for the fulfillment of the promises made to women throughout the war and in the negotiated settlement. Fearing their marginalization from post-conflict political discussions and opportunities (Geisler Reference Geisler2000), female former ANC members mobilized, contested in spaces from which they had been excluded, and advocated for the implementation of gendered policies every step of the way (Waylen Reference Waylen2014). This work extended beyond the immediate transition period, as ANC women activists were elected to parliament in subsequent post-conflict elections. Looking back, Ginwala concluded that ANC women’s successes “did not happen out of nothing … it is a process of which the MPs have been a part” (Geisler Reference Geisler2000, 607). As Ginwala suggests, women’s successes were borne of a long struggle to which ANC women were committed both during and after the fight against apartheid. ANC female MPs’ wartime roles positioned them to continue advocating for their political goals in elected office. In fact, many of the women running on the ANC ticket were deeply embedded in the organization’s earlier fight against apartheid (Geisler Reference Geisler2000). This embeddedness offered them the clout and influence with which to pursue their policy goals.

ANC women’s success in pushing post-conflict policy is illuminating not only because they were able to leverage their wartime roles into postwar gains, but also because it demonstrates that long-term gains for women demand sustained post-conflict activism, some of which takes place within government institutions and includes female militants.

Sudan’s 2005 comprehensive peace agreement further underscores the challenges militant women face when trying to introduce provisions that benefit women into peace agreements and the strategies they pursue to ensure the terms’ implementation after conflicts end. Women buoyed the multi-decade rebellion staged by the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM), even fighting on the frontlines alongside men. Despite their centrality to the movement, few women were initially included in the peace process, and they struggled to have their demands heard. The peace agreement included gender-inclusive peace terms, but they were watered down and vague. For example, the SPLM’s women members and other female activists advocated for the inclusion of a 25% gender quota, but the final agreement only included a provision establishing that men and women would have equal social and political rights without detailing measures by which those goals would be achieved. Disappointment with the terms written into the agreement led SPLM female cadres to use their residual wartime political influence to ensure women made greater post-conflict gains. Electoral politics became a vehicle by which these militant women built and then maintained post-conflict power; they used their roles as elected Members of Parliament (MPs) and cabinet members to continue pushing their demands after the peace process concluded. Importantly, after the first postwar election, women parliamentarians’ and activists’ successful mobilization led to the adoption of the 25% gender quota they were unable to achieve during negotiations (Tønnessen and al-Nagar Reference Tønnessen and al-Nagar2013). Minister Anne Itto, a former SPLM combatant and peace delegate during the negotiation process, proffered that the implementation process was paramount to the actual provisions listed in the peace agreement, as an agreement that goes unimplemented is meaningless (Itto Reference Itto2006). Thus, Itto and her SPLM colleagues made sure the window of opportunity for rebel women to usher in change did not close fully when the conflicts terminated. Instead, former female rebels used the implementation process as an additional opening to influence political and social outcomes for women. In this Element, we show that former rebel women seize these opportunities and do so with great effect.

Much of the scholarship on women in peace processes and postwar transitions shows that women’s inclusion leads to better outcomes for women and peace broadly (Duque-Salazar et al. Reference Duque-Salazar, Forsberg and Olsson2022; Ellerby Reference Ellerby2016; Krause et al. Reference Krause, Krause and Bränfors2018; Reid Reference Reid2021; True and Riveros-Morales Reference True and Riveros-Morales2019). Yet, extant research focuses mainly on how women affect the adoption of gendered provisions within negotiated settlements, offering less insight into whether and how these promises are implemented. As the narratives from South Africa and Sudan suggest, however, the push for gender-inclusive policies – and the attendant effects of these advancements – does not conclude with the signing of a peace settlement. Rather, it involves a lengthy and often arduous fight to implement these policies, in which women play a key role. Without implementation, the gains these settlements’ promise to women remain little more than “scraps of paper.”

In this project, we consider women’s roles in the implementation of gendered policies after war. We build on the rich literature on women’s inclusion during peace processes to ask how women influence compliance with the gendered provisions included in peace agreements. Our research contributes to this body of work by shifting focus from asking when and why peace agreements contain gender-inclusive terms to examining the extent to which parties attempt to implement these terms written into agreements. In other words, we seek to better understand when the promises in agreements become realized. Further, we consider how the electoral process can provide opportunities for women who were members of former non-state armed groups like the ANC and SPLM to affect the implementation process after wars abate. We ask specifically how women’s representation in rebel parties – violent armed groups that transition into political parties – can impact compliance with gender-inclusive peace agreement terms. Finally, we explore whether women legislators’ wartime connections to rebel groups affect the realization of the policies laid out in gendered peace provisions.

We conceptualize gendered provisions as any peace agreement provisions that reference women, girls, gender, or gender-based/sexual violence (Bell et al. Reference Bell, Badanjak and Beujouan2024). Data suggests 39% of peace agreements between 1990 and 2018 include such provisions (Olson Lounsbery et al. Reference Lounsbery, Marie and Rose2024). These terms have become even more prevalent since the passage of United Nations Security Council resolution (UNSC) 1325 (Olson Lounsbery et al. Reference Lounsbery, Marie and Rose2024), as nearly half of the agreements between 2000 and 2016 include at least one gender-inclusive agreement term (True and Riveros-Morales Reference True and Riveros-Morales2019). Sudan’s 2011 Doha agreement stipulated, for example, that “in accordance with the UNSCR 1325 (2000), the Commission shall ensure that all forms of violence that specifically affect women and children are heard and redressed in a gender sensitive and competent manner.”Footnote 2 Burundi’s 2006 Dar-es-Salaam agreement proposed that the country’s prospective “Truth and Reconciliation Commission shall … reflect the broadest representation of the Burundi society in its political, social, ethnic, religious and gender aspects.”Footnote 3 Colombia’s 2016 Comprehensive Peace Agreement provides a much more detailed example in asserting the following: “taking account of the fact that women face greater social and institutional barriers in terms of political participation, as a result of deep-rooted discrimination and inequality, as well as structural conditions of exclusion and subordination, there will be significant challenges in guaranteeing their right to participation and facing up to and transforming these historical conditions will involve developing affirmative measures that will safeguard women’s participation in the various areas of political and social representation.”Footnote 4

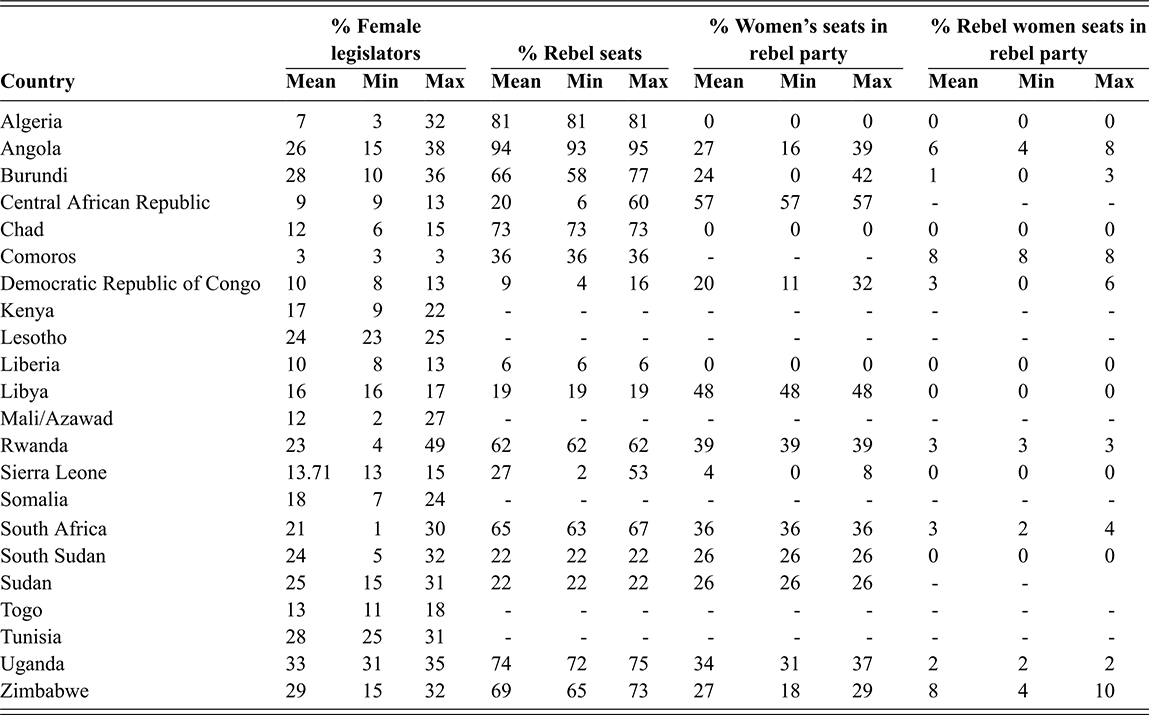

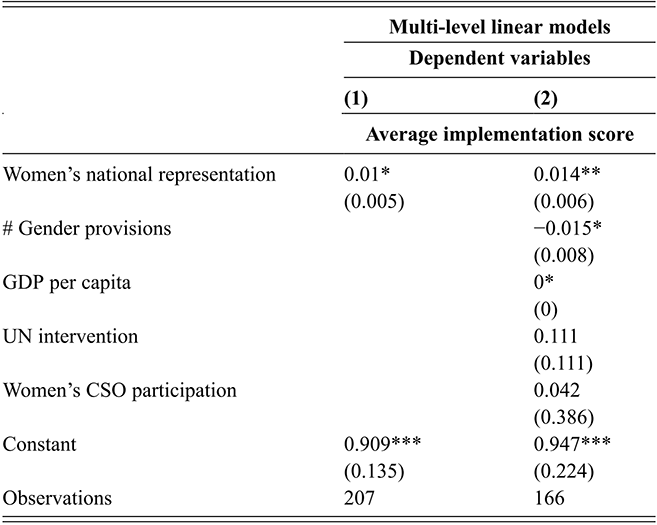

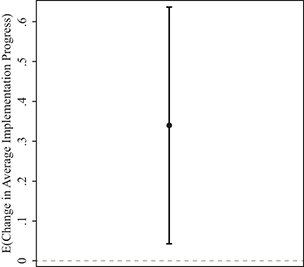

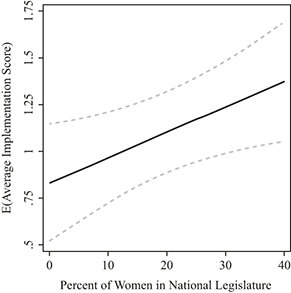

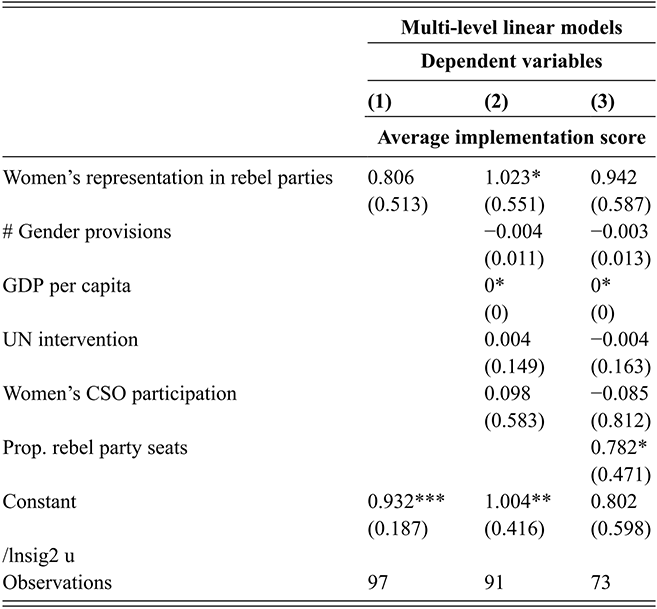

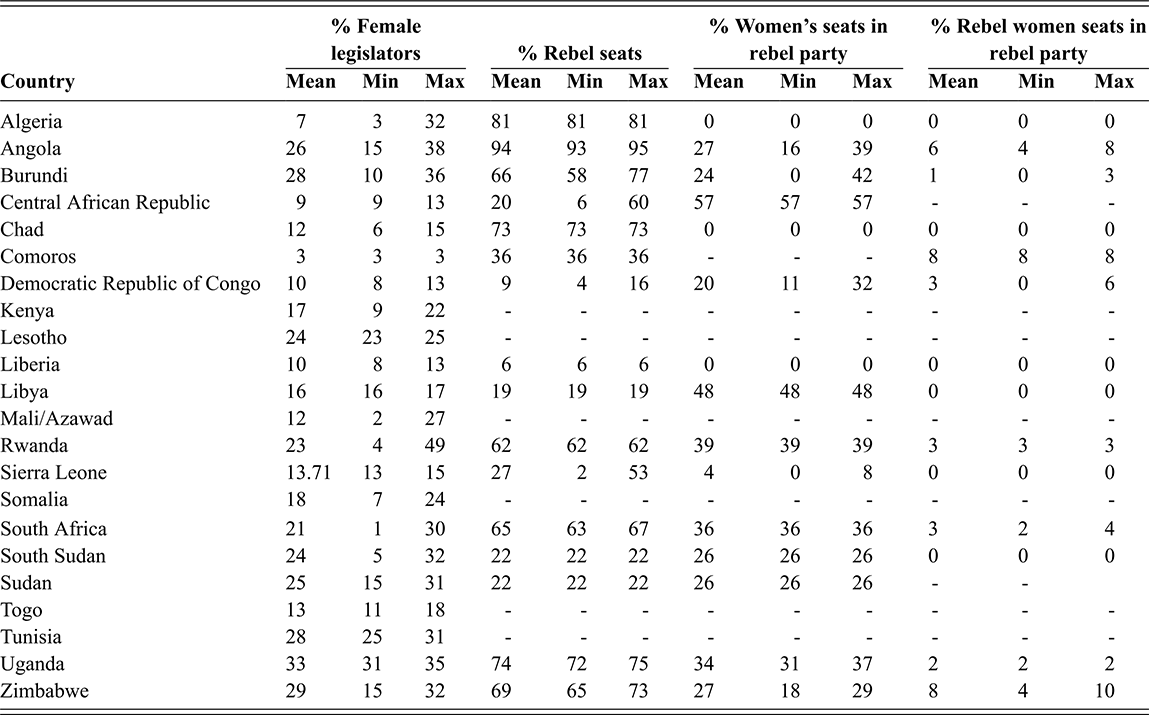

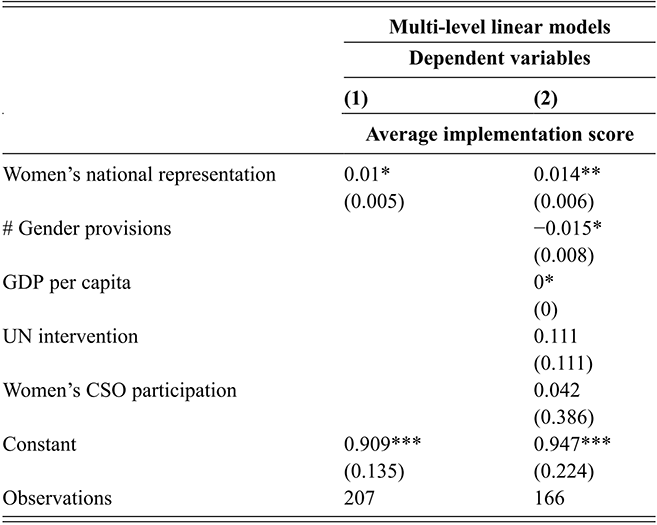

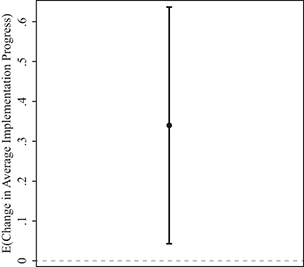

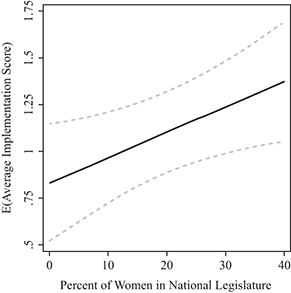

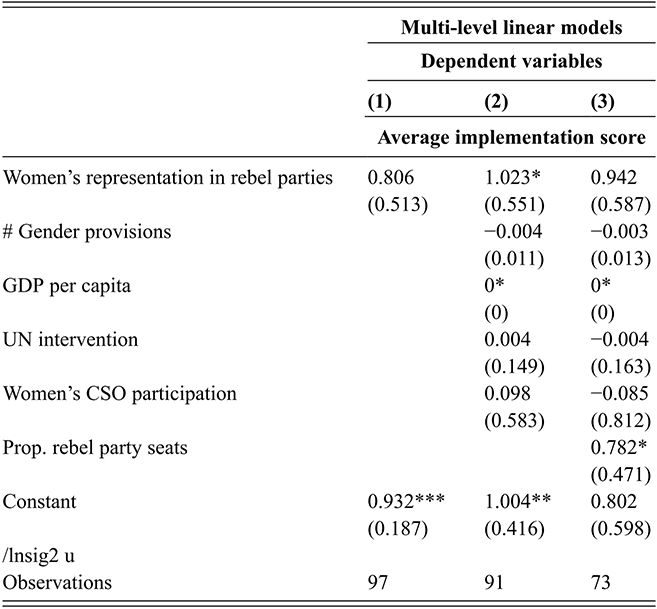

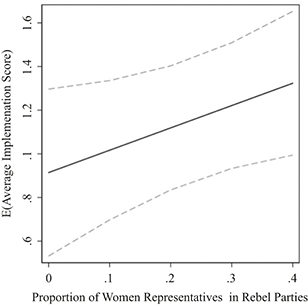

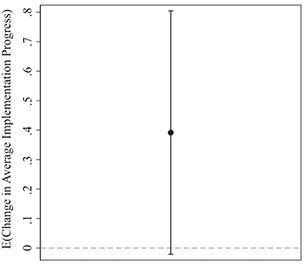

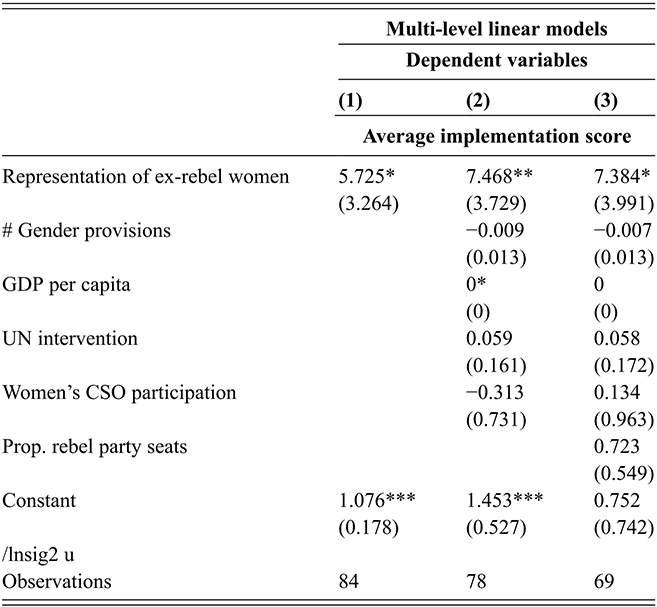

Using a novel dataset on the implementation of gender provisions in African peace agreements, we find evidence that women’s national representation and the representation of ex-rebel women are associated with higher levels of implementation of gender peace provisions. We complement these findings with brief illustrative cases from Angola, Rwanda, and Colombia. We find support for our key argument in the African cases. We use our illustrative case of Colombia to explore how these findings may travel, but emphasize the need for further data collection to confirm that our argument generalizes to other regions.

Our novel research draws together two related, though frequently siloed, bodies of literature: that on women, peace, and security and that on rebel party transitions. Previous work on the role of women in peace processes emphasizes the importance of women gaining a seat at the negotiating table and the adoption of gendered peace provisions, but fails to consider whether women’s continued presence and pressure impact when such provisions come to life. At the same time, the research on rebel party politics demonstrates the importance of these political organizations and their memberships in supporting or threatening postwar peace but focuses more on conflict relapse and peace durability than on how these organizations promote compliance with specific agreement terms or whether group-level characteristics such as gender diversity impact the implementation process. While newer work has begun to consider women’s representation in rebel parties, it has focused mainly on explaining patterns of their descriptive representation rather than assessing their substantive impact. In the sections that follow, we discuss these bodies of literature in greater depth, highlighting how we build on previous work to advance our understanding of women’s roles in the implementation processes. We then offer an overview of our theoretical argument and findings. We conclude with a summary of the sections of this Element.

1.1 Women’s Inclusion, Gender Policies, and Peace Transitions

Though war has detrimental and often uneven impacts on the livelihoods and security of women, it can also usher in a “window of opportunity,” in which women find avenues to carve out space for themselves in political, social, and economic spheres of life that would have been unthinkable prior to the war. War is associated with short and medium-term gains in women’s empowerment (Webster et al. Reference Webster, Chen and Beardsley2019). Women’s political representation also often rises after wars, in part due to institutional changes like the adoption of gender quotas and pressure from international and domestic women activists (Tripp Reference Tripp2015). Women’s rights after wars also increase as new constitutions are drafted and implemented (Tripp Reference Tripp2016). Moreover, gains for women offer broad benefits to a state’s postwar peace, security, and stability, as many scholars find that higher levels of women’s political representation are associated with a lower likelihood of conflict relapse and longer peace duration after war (Demeritt et al. Reference Demeritt, Nichols and Kelly2014; Shair-Rosenfield and Wood Reference Sarah and Wood2017). These findings accord with the research demonstrating negative relationships between women’s participation in politics, on one hand, and the likelihood of military crises (Caprioli Reference Caprioli2000, Reference Caprioli2005), human rights abuses (Melander Reference Melander2005b), and conflict severity (Melander Reference Melander2005a) on the other.

Women’s inclusion in peace processes can also lead to distinctive and consequential outcomes. First, peace negotiations that include women are likelier to end in signed agreements, and resulting agreements are more readily implemented (O’Reilly et al. Reference O’Reilly, Ó Súilleabháin and Paffenholz2015). Women’s participation is also correlated with a longer duration of post-conflict peace (Krause et al. Reference Krause, Krause and Bränfors2018). Women’s participation in the formal peace process creates positive externalities for women, as gendered peace provisions are likelier to be adopted when women serve in peace delegations (Anderson Reference Anderson2015; Ellerby Reference Ellerby2016; True and Riveros-Morales Reference True and Riveros-Morales2019), especially in more central roles (Good 2024). Finally, peace agreements that include gendered provisions are associated with higher levels of women’s rights after wars (Reid Reference Reid2021), as well as increased civil liberties and political representation (Bakken and Buhaug Reference Bakken and Buhaug2020).

Scholars have offered many explanations for how women produce such positive outcomes. In general, the successful adoption of gender provisions in agreements is the result of significant, sustained advocacy by women activists, including those with a formal seat at the table and those without. First, women’s inclusion in the peace process can broaden the perspectives that are represented and diversify the interests of those negotiating – ensuring the process better embodies the interests of society (Anderlini Reference Anderlini2000; Anderson Reference Anderson2015; Ellerby Reference Ellerby2016; Paffenholz et al. Reference Paffenholz, Ross, Dixon, Schluchter and True2016). Moreover, female negotiators draw attention to women’s issues and advocate for provisions that begin to address these concerns. Second, women in peace processes are often effective at building influential cross-cutting coalitions that reach across the aisle to women in other delegations and foster ties with women in civil society groups (Krause et al. Reference Krause, Krause and Bränfors2018; O’Reilly et al. Reference O’Reilly, Ó Súilleabháin and Paffenholz2015; Paffenholz et al. Reference Paffenholz, Ross, Dixon, Schluchter and True2016). These broad, diverse alliances increase the chance that the warring sides are able to find common ground and enable negotiating parties to generate settlements that are more reflective of society at large (Krause et al. Reference Krause, Krause and Bränfors2018). These processes result in more expeditious and equitable peace settlements (Tamaru and O’Reilly Reference Tamaru and O’Reilly2018).

For example, when the Colombian government first sat down at the negotiating table with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia-People’s Army (FARC-EP) in 2012, there was only one woman included in the FARC-EP delegation, and the government delegation had no women representatives (Céspedes-Báez and Ruiz Reference Céspedes-Báez and Ruiz2018). This sparked outrage among women’s groups, including civil society leaders, FARC-EP women guerrillas, and international activists, who all put mounting pressure on the delegations to put forth a more inclusive slate. This pressure led the Colombian process to become the most gender-inclusive peace process to date (Bouvier Reference Bouvier2016). A key pressure point was the coalition between militant and nonmilitant women. Similarly, in Guatemala, Luz Mendez, a former United National Revolutionary Unity (URNG) guerrilla, was one of just two women appointed to the negotiation team. However, she was forceful in promoting women’s rights during the peace process and was aided by a coalition that included women’s civil society organizations (Krause et al. Reference Krause, Krause and Bränfors2018). This alliance ensured that the resultant provisions were representative of a broad array of women’s interests (Méndez Reference Méndez, Durham and Gurd2005).

Though the potential payoffs of women’s inclusion are high, the path to inclusion is still littered with hindrances. Women are largely underrepresented in these processes. Between 1992 and 2019, women accounted for only 13% of mediators, 6% of signatories, and 6% of negotiators in peace processes.Footnote 5 Even when women occupy one of the rare seats at the table, gendered hierarchies hinder their ability to contribute equally (Anderson and Golan Reference Anderson and Golan2023). Women’s expertise is often assumed to be limited to “women’s issues,” excluding them from other critical discussions (Aharoni Reference Aharoni2011; Ellerby Reference Ellerby2013). Furthermore, even with regard to the adoption of gendered provisions, negotiating actors often push back against the inclusion of these provisions despite significant international support and pressure for their inclusion (Hirblinger et al. 2019; Itto Reference Itto2006; Paffenholz et al. Reference Paffenholz, Ross, Dixon, Schluchter and True2016).

Moreover, recent scholarship cements the idea that it matters which women are included in peace processes. In particular, new studies show that the specific women at the table can influence the possibilities for peace and the outcomes of conciliation. Brannon and Best (Reference Brannon and Best2022), for example, demonstrate that delegations’ selection criteria can affect the quality of women’s contributions, as women selected for their reliability and loyalty may be more likely to uphold the status quo and toe the party line. Likewise, Paffenholz et al. (Reference Paffenholz, Ross, Dixon, Schluchter and True2016) suggest that in the Philippines, the selection of female delegates, who were mainly wives and family members of rebel leaders, stunted coalition building among women delegates, as the women affiliated with the rebels were unwilling to cross the party line. Research has also begun to show that women’s representation within militant groups can influence the conflict resolution process. Brannon et al. (Reference Brannon, Thomas and DiBlasi2024) for example, show that gender-diverse rebel groups are more likely to participate in peace talks with the state, and this can be attributed, in part, to the propensity for armed groups that recruit women to make peace overtures more frequently. At the same time, women’s participation in rebel groups can affect which gendered policies are advanced in peace settlements. Since rebel women have distinct interests from nonmilitant women, their inclusion increases the chances that gendered provisions relevant to their interests as combatants and women from marginalized backgrounds are adopted (Thomas Reference Thomas2023).

While the scholarship on gender and peace processes has offered a rich understanding of the causes, consequences, and complications of women’s roles in peace processes, little is known about the implementation of these terms post-conflict. Gender peace provisions can fall by the wayside after wars end, and outside pressure on and attention to these issues dissipates. Moreover, many gendered provisions require longer time horizons and sustained attention for them to be implemented successfully since they often require that underlying gender relations are restructured and inequalities are redressed (Joshi et al. Reference Joshi, Olsson, Gindele, Alvarez and McQuestion2020). One of the few inquiries into this question suggests women’s mobilization – mainly through civil society organizations – can encourage the implementation of gender-inclusive stipulations but only where governments are willing to prioritize gender issues (Duque-Salazar et al. Reference Duque-Salazar, Forsberg and Olsson2022). Extant research has overlooked the key question of when and why a state might come to view gender issues as priorities and has not examined the full range of women’s coalitions that could be mobilized to facilitate this process. Our research fills this lacuna, offering deeper insight into women’s contributions to postwar peace and gender politics.

1.2 The Implementation of Peace Agreements

While a body of research has examined the dynamics and outcomes of negotiated settlements or peace processes, there has been less scholarly attention on the implementation of such agreements. Although conflict negotiations represent an important step in securing peace, the negotiation stage does not represent a “definitive endpoint” of conflict (Mockinlay et al. Reference Mockinlay, Darby and MacGinty2005, 4). Likewise, though monumental, the signing of peace agreements marks only the beginning of peacebuilding efforts. The post-agreement period can be rife with uncertainty about former warring parties’ commitments to uphold their side of the bargain. Thus, the efficacy of an agreement and the peace it creates depends on whether its provisions are implemented (Joshi and Wallensteen Reference Joshi and Wallensteen2018; Mockinlay et al. Reference Mockinlay, Darby and MacGinty2005; Stedman Reference Stedman2001). Joshi and Quinn (Reference Joshi and Quinn2017) argue that the implementation of agreements is even more critical than the negotiation process because it normalizes relationships between formerly hostile groups, solves credible commitment and information problems, and perhaps most importantly, addresses the root causes of the civil conflict. The degree to which agreements are implemented thus affects post-conflict peace duration and decreases the chances of future conflict eruption or reoccurrence (Joshi and Quinn Reference Joshi and Quinn2016, Reference Joshi and Quinn2017; Joshi and Wallensteen Reference Joshi and Wallensteen2018; Stedman Reference Stedman2001).

Former rebels’ buy-in is foundational to the implementation of these agreements, as they can act as spoilers to these processes or as bulwarks against backsliding. Former rebel groups’ transformation into political parties (rebel parties), a provision frequently written into contemporary negotiated agreements (Matanock Reference Matanock2017, Reference Matanock2018), can play a sizable role in shaping the direction of the implementation process. Former rebel parties’ commitments to the use of institutionalized and peaceful means to drive policy, and their willingness to make political compromises, can help ensure that the transition from war to postwar politics is peaceful (Lyons Reference Lyons2016a). Moreover, when rebel parties gain political power and influence through the electoral process, their cooperation becomes necessary to advance the implementation process (Mockinlay et al. Reference Mockinlay, Darby and MacGinty2005). Where they hold significant power, rebel parties can shape which provisions are implemented and how.

Scholars have studied how rebel party behavior influences the stability of the implementation period. Studies have considered how vulnerability and competition among former belligerents impacts perceived costs and benefits of reigniting war (Bekoe Reference Bekoe2003, Reference Bekoe2005), how guaranteed spoils in the form of government positions improve implementation and peace duration (Hartzell and Hoddie Reference Hartzell and Hoddie2003; Jarstad and Nilsson Reference Jarstad and Nilsson2008; Joshi et al. Reference Joshi, Lee and Ginty2017a), and how wartime party structures and intra-elite competition among former rebels parties influence rebels’ capacity to successfully adapt to new, institutionalized political rules of the game (Ishiyama and Batta Reference Ishiyama and Batta2011; Ishiyama and Widmeier Reference Ishiyama and Widmeier2020; Lyons Reference Lyons2016b; Manning Reference Manning2004, Reference Manning2007). Much of this work suggests implementation is affected by the iterative nature of inter- and intra-party relationships. Among all political parties in government, including rebel parties, priorities are informed by actors’ needs to differentiate themselves from other parties through policy spoils for supporters, and the degree to which they want to appear willing to cooperate with their opposition (Joshi et al. Reference Joshi, Lee and Ginty2017a; Joshi and Quinn Reference Joshi and Quinn2017). Intra-party conflict can also shape priorities, particularly in newly formed rebel parties. Studies suggest that rebel party leaders must have buy-in from elites and majority coalitions for agreements to succeed (Bekoe Reference Bekoe2003, Reference Bekoe2005; Lyons Reference Lyons2016b; Mockinlay et al. Reference Mockinlay, Darby and MacGinty2005). Former combatants, who maintain significant sway over their former rebel parties after wars end, are also influential in this process (Sindre Reference Sindre2016a, Reference Sindre2016b).

Broadly, this work suggests rebel party politics can have a significant influence on the uptake of an implementation process. Namely, compliance with a peace agreement will be determined by the interests of those who hold power and those who support the relevant powerbrokers. Following this logic, we contend that when women are among those who hold power, gendered peace agreement provisions are more likely to be translated into post-conflict law and practice. To date, existing work has not considered the role of gender – whether that is the influence of women in rebel parties or how rebel parties prioritize gender-inclusive provisions – in influencing how organizations approach fulfilling their obligations to the peace process. This oversight is glaring given the many ways women affect rebel organizational dynamics and the peace process more specifically.

1.3 Theoretical Argument

In this Element, we argue that women drive the implementation of gendered peace provisions after wars. Though we consider the effect of women’s national representation, we focus primarily on women who are elected representatives in rebel parties, who can use their positions to encourage the implementation of gendered peace provisions. We expect, however, that women representatives’ ability to impact the implementation process is conditioned by their positionality within postwar political power structures. It is important to focus on the role of women within former rebel parties since former belligerents – particularly those that attain post-conflict political power – can wield significant influence over the state’s implementation priorities after war. Women’s roles within these parties offer them access and leverage to shape the implementation of agreements, specifically gendered provisions. Moreover, rebel women’s wartime networks and experiences uniquely position them to hold their former organizations accountable for the commitments they made during peace negotiations.

We test three implications of this broad argument. First, we explore whether women’s national level of political representation is associated with higher levels of implementation of gendered peace provisions. This builds on research that suggests women’s inclusion in peace processes generally leads to better outcomes with regard to gendered provisions and peace duration. Second, we examine whether rebel parties with a higher percentage of women party members are likelier to push for the implementation of gender peace provisions, following research suggesting the proportion of women within wartime rebel movements correlates with the inclusion of gendered agreement terms. Third, we consider differences among women representatives in rebel parties, arguing that not all women within these parties have an equal impact on peace agreement implementation. Although any women within a post-rebel party might impact the implementation of gender-inclusive terms, we argue that the recruitment of a greater number of women who served in the rebel group during the war will amplify women’s influence over implementation because rebel women will maintain closer network ties to rebel elites and are more likely to have been involved in the process of negotiating gendered stipulations. By examining these three forms of women’s representation, we seek to understand which women impact the implementation of gendered peace provisions as well as how women’s positions within wartime networks influence postwar gender politics.

Throughout our argument, we highlight the distinct role of former rebel women represented in rebel parties. We argue that women’s presence in key positions of power within post-conflict governments can increase the chance of implementation. Our argument is probabilistic, not determinative, however. We do not expect women rebel party legislators to always affect implementation. We also do not believe women’s participation in rebellion is sufficient to ensure gender provisions are implemented. Instead, we argue that women’s appointment to government roles through rebel parties is crucial, though we also accept that there are limits to what they can accomplish.

Moreover, we do not expect that former rebel women alone drive implementation. We hypothesize that women legislators writ large can also positively affect implementation, though we argue rebel women can act as critical agents in these environments.Footnote 6 We proffer that former rebel women will be crucial nodes in legislative networks, influencing rebel party politics through their wartime ties and building coalitions with other women legislators. Though there may be a small number of ex-rebel women elected, research on women and politics has demonstrated that a small minority of actors within legislatures can still have a significant effect on outcomes (Bratton Reference Bratton2005; Crowley Reference Karlyn2011). Thus, we expect that even if rebel women represent a minority of seats in the legislature, they may still have an important and unique effect on implementation.

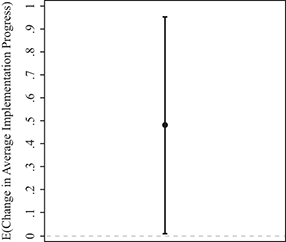

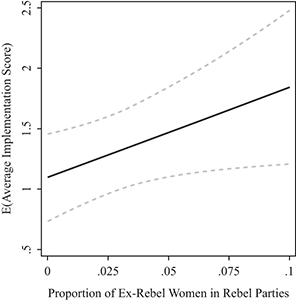

1.4 Overview

Our Element is organized as follows: In the next section, we ground our study in previous research on former wartime belligerents, commitment problems, and powersharing. We present our theoretical argument in Section 3. In Section 4, we offer our research design and present our novel dataset on the implementation of gender peace agreement provisions. Section 5 offers an empirical analysis of our core arguments, which proposes that women’s representation in rebel parties will be associated with greater implementation of gender-inclusive peace provisions. We first test the relationship between women’s national representation and implementation, finding evidence that women’s political representation in national parliaments fosters implementation. We then consider the role of women representatives within rebel parties, finding mixed results regarding their impact on implementation. Our final test most directly tests our argument by considering the effect of female representatives of rebel parties that were former combatants, finding robust evidence that higher levels of female ex-rebel representation in rebel parties is associated with higher rates of implementation. We bolster these statistical tests with qualitative evidence from Angola, Rwanda, and Colombia.

In Section 6, we conclude by highlighting our contributions to several bodies of literature, including gender and peace processes, rebel party politics, and women’s roles in peace transitions. We discuss the real-world implications of our findings, especially how our findings call for revisions to the current iteration of the Women, Peace, and Security agenda. We conclude with a discussion of important questions that emerge from our theory and findings.

2 Former Rebel Parties and the Implementation of Peace

Although peace agreements are not merely “scraps of paper” (Fortna Reference Fortna2003), reaching a deal does not guarantee peace or ensure that the issues underlying a conflict are resolved. Resolving these issues, however, is key to sustainable peace (Werner Reference Werner1999). While treaties are often carefully designed to address belligerents’ grievances, there are often substantial barriers to their full implementation. Peace processes can be impeded by warring parties’ lack of will and inability to follow through with their commitments. Issues that might be deemed ancillary are especially likely to be neglected during this implementation phase. Sidelining these “secondary” issues is especially likely to impact the implementation of gender-inclusive peace terms since even the rebel groups that push for women’s interests often cast gender issues as subordinate to the primary conflict issues. Even while promoting women’s inclusion, militant organizations, such as the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO), Communist Party of Nepal-Maoist (CPN-M), and the ANC have conceptualized women’s issues as ancillary and secondary to the main lines of conflict (Brechenmacher and Hubbard Reference Brechenmacher and Hubbard2020; Katto Reference Katto2014; Pavarti Reference Pavarti2005). When the need to prioritize certain provisions arises, belligerents may be especially unfaithful to gender-inclusive terms.

Given the tendency for implementing parties to prioritize some provisions over others, the enactment of gender-inclusive peace agreement terms may be observed only under certain conditions. To affect implementation, rebel parties first need to have access to the reins of power. We conceptualize access to power as the ability to participate in the legislature as an official political party. Although there are other mechanisms of rebel-state powersharing, we argue that the ability to compete in elections provides rebels with the means and opportunity to contest power over the long term. While other types of powersharing institutions include temporary provisions that enable rebels to share power during a transitional administration, the ability to take part in elections in the future allows rebels to impact implementation after these temporary institutions are replaced.

Since we are particularly interested in the enactment of gender-inclusive peace terms, we believe women within these former rebel parties will play a key role. First, we suggest that the implementation of gender peace provisions will be higher when women’s national representation is higher. This is consistent with extant research that suggests women have played an important role in the negotiation and adoption of gendered peace terms. Second, we assert that the implementation of these provisions will be more likely when women make up a greater share of rebel party legislators. We consider how women within rebel parties may be able to shift priorities and the behavior of former belligerents. Third, we argue that women representatives in rebel parties who were wartime members will have a particularly potent effect on implementation outcomes because they are both able to derive clout from their affiliations with former rebel groups and draw on their wartime (and postwar) coalitions and networks to push for gendered policies. We build this argument, starting with how bargaining problems, powersharing, and resource constraints cause negotiating parties to prioritize some provisions over others and then explaining why rebel-party transitions and women’s representation will help overcome these issues.

2.1 Bargaining Dynamics, Powersharing, and Implementing Peace Agreements

Warring parties often sign peace agreements under immense pressure to end bloodshed, which affects the implementation of post-conflict peace agreements. Belligerents are often faced with the choice to either continue conflict or settle for a subpar bargain. When parties opt for imperfect settlements, agreements may end up including terms that at least one side is displeased with and has little incentive to comply with after violence abates. Since negotiations and concessions are often acceded to when pressure and pain are at their height (Pechenkina and Thomas Reference Pechenkina and Thomas2020; Thomas Reference Thomas2014; Zartman Reference Zartman2005), a signed agreement does not necessarily ensure warring parties will uphold their commitments when circumstances change.

Commitment problems often affect whether parties honor the terms in agreements. Belligerents’ interests in terms of peace can change with expectations about their future strength. Time inconsistency problems, which occur when governments or rebels believe their military capabilities will improve with time, can prevent the implementation of the agreed-upon terms, as parties have incentives to accept peace even if they plan to renege on their promises later (Werner Reference Werner1999). The possibility of these changing interests is particularly concerning for rebels, who are often expected to demobilize before the government makes any headway on upholding their end of the bargain (Fortna Reference Fortna2003; Johnson Reference Johnson2021; Walter Reference Walter2002). The essence of the commitment problem known to impair civil war settlement and engender conflict recurrence is that parties sign deals that are ultimately unenforceable (Walter Reference Walter1997, Reference Walter2002, Reference Walter2009).

As Stedman (Reference Stedman2001, 1) notes, periods directly following the signing of a civil war peace agreement are “fraught with risk, uncertainty, and vulnerability for the warring parties and civilians caught in between.” Those seeking to comply with the agreement can be waylaid by spoilers, which may emerge from both within and outside of the peace process (Stedman Reference Stedman1997). Inside spoilers, which can include both governments and rebels, may not always rely on violence; they may sabotage peace by simply failing to implement key parts of an agreement. Scholars argue, however, that settlements can be designed with features to minimize these risks (Mattes and Savun Reference Mattes and Savun2009); security guarantees and powersharing, for instance, are believed to attenuate commitment problems and lead to more durable peace (Beardsley Reference Beardsley2008; Walter Reference Walter1997, Reference Walter2009).

Powersharing terms appear in half of all comprehensive peace settlements (Joshi and Quinn Reference Madhav and Quinn2015). Previous research finds that when former belligerents share power in post-conflict environments, peace accords are likelier to be implemented and peace is more enduring (Hartzell and Hoddie Reference Hartzell and Hoddie2003; Mattes and Savun Reference Mattes and Savun2009). According to Hartzell and Hoddie (Reference Hartzell and Hoddie2003, 320), powersharing institutions refer to “rules that, in addition to defining how decisions will be made by groups within the polity, allocate decision-making rights, including access to state resources, among collectivities competing for power.” Referring to ethnic powersharing in particular, Roeder and Rothchild (Reference Roeder and Rothchild2005, 31) argue that powersharing institutions aim “to reassure minorities that their interests will be taken into account by guaranteeing the participation of representatives of all the main ethnic groups in the making of governmental decisions.” To have this mollifying effect, representatives need to have access to actual power, which means tokenism – or the accommodation of only a couple of a group’s representatives – is insufficient to provide such assurances (Roeder and Rothchild Reference Roeder and Rothchild2005).

Among the four types of powersharing institutions (i.e., political, economic, military, territorial), scholars have homed in on political powersharing – including electoral proportional representation – as particularly stabilizing (Mattes and Savun Reference Mattes and Savun2009; Walter Reference Walter2002).Footnote 7 Mukherjee (Reference Mukherjee2006, 411) argues that “providing political representation to minorities and leaders of insurgent groups increases their stakes in the political process and reduces their incentives to fight against the state.” Political powersharing can also limit belligerents’ ability to renege on bargains (Mattes and Savun Reference Mattes and Savun2009), which increases the chance that agreements are implemented and peace prevails. Powersharing institutions also help manage belligerents’ mistrust and help parties alter their expectations and perceptions of their opponents (Joshi et al. Reference Joshi, Lee and Ginty2017; Joshi and Quinn Reference Madhav and Quinn2015).

Scholars also argue that the creation of transitional institutions and rebel-to-party transitions, which transform and demilitarize politics, can prove vital for durable peace (Lyons Reference Lyons2015; Spears Reference Spears2000). Such rebel party transitions are most prevalent in Africa (Manning et al. Reference Carrie, Smith and Tuncel2024). Even though electoral contests may be seen as more advantageous to states (Johnson Reference Johnson2021), electoral participation provisions offer a path for rebels to contend in elections and can produce more stable and longer-lasting peace, as these terms encourage parties to uphold their ends of compromise agreements (Matanock Reference Matanock2017).

Rebels’ successful integration into postwar governments can facilitate continued bargaining that can accommodate changing interests. Since formal bargaining continues in the post-accord period (Bekoe Reference Bekoe2003), a time marked by mutual vulnerability and suspicion (Joshi et al. Reference Joshi, Lee and Ginty2017), sharing power can create opportunities for former belligerents to work together to make decisions if wartime negotiations prove insufficient in the post-conflict environment (Lyons Reference Lyons2015). Difficulties and disagreements inevitably arise during the implementation process, but when parties can address issues in real time, disagreements are less likely to derail peace (Hartzell and Hoddie Reference Hartzell and Hoddie2003). Moreover, a commitment to implementation can be a costly signal of a belligerent’s dedication to peace (Hoddie and Hartzell Reference Hoddie and Hartzell2005).

The joint work of implementing agreements can solve common bargaining issues – including information and commitment problems, help address the root causes of conflict, and normalize political relationships between former warring parties (Joshi and Quinn Reference Madhav and Quinn2015). Powersharing helps ensure compliance with an agreement because it enables rebel groups to act as a check on the state, which might otherwise attempt to evade implementation (Joshi et al. Reference Joshi, Lee and Ginty2017). Together, powersharing arrangements and verification provisions increase the likelihood of an agreement’s implementation (Joshi et al. Reference Joshi, Lee and Ginty2017). Offering rebels a stake in the implementation process can increase their ownership over and buy-in to the implementation of the peace process (Molloy and Bell Reference Molloy and Bell2019). In some cases, the implementation process can be a task delegated specifically to coalition governments, which include former rebels (Molloy and Bell Reference Molloy and Bell2019).

According to Joshi and Quinn (Reference Madhav and Quinn2015, 873), the day-to-day process of implementation can enable belligerents to “work together to represent their constituencies and gain recognition for themselves in the process.” While representing their supporters, rebels in post-conflict governments can also advance their own political interests peacefully (Joshi and Mason Reference Madhav and Mason2011). Rebels use negotiated settlements to alter the political status quo, renegotiate the distribution of power (Joshi and Quinn Reference Madhav and Quinn2015), and expand the size of the winning coalition (Joshi and Mason Reference Madhav and Mason2011). The latter can increase the value of providing public goods and reduce the risk of returning to conflict. Indeed, many agreements include terms that cater to a broad civilian constituency, including provisions for the reduction of poverty, discrimination, and repression (Joshi and Quinn Reference Madhav and Quinn2015).

However, even when belligerents have the will to implement and are able to overcome bargaining obstacles, they may lack the ability to fully comply with the agreements they sign under duress. Low state capacity, in particular, can threaten implementation even when states want to follow through (DeRouen et al. Reference DeRouen, Ferguson and Norton2010). Implementation needs willingness but also resources for parties to be able to stick to the bargains (Karreth et al. Reference Karreth, Quinn, Joshi and Tir2019). Yet, states emerging from long and costly civil wars often lack the resources to effectively implement the terms of the agreements (Stedman et al. Reference Stedman, Rothchild and Cousens2002). Since peace agreements often contain a wide range of provisions that need to be implemented to meet the full set of agreement terms (Stedman et al. Reference Stedman, Rothchild and Cousens2002), states facing a resource shortfall may find full compliance with an agreement particularly challenging. Resource constraints can lead states to prioritize some terms over others. Terms that do not address the state’s immediate concerns may be implemented later than others or not at all. Stedman et al. (Reference Stedman, Rothchild and Cousens2002, 3) suggest the decision for states to follow through with their commitments in civil war rests on their willingness to “invest blood and treasure” and their belief that a peace settlement will advance the state’s security interests. However, how they prioritize these terms after the war will vary.

2.2 Variation in Implementation by Provision Type

The combination of bargaining, powersharing, and resource challenges can lead to differences in how specific provisions are implemented. Both the threat of commitment problems derailing peace and the menace of resource constraints have led some scholars to advocate for sequencing the implementation of peace agreement terms (Joshi et al. Reference Joshi, Lee and Ginty2017). This simply calls for some types of provisions to be prioritized over others. For durable peace, scholars argue that belligerents should address commitment problems before they introduce other political changes, including holding post-conflict elections (Joshi et al. Reference Joshi, Lee and Ginty2017). Some research suggests post-conflict stability requires states to prioritize demobilization, disarmament, and reintegration and the demilitarization of politics (Spears Reference Spears2000; Stedman et al. Reference Stedman, Rothchild and Cousens2002). Judicial reforms and improvements to human rights capacity are also important ways to ensure that peace sticks and conflicts do not recur (Spears Reference Spears2000; Stedman et al. Reference Stedman, Rothchild and Cousens2002). Moreover, scholars suggest that belligerents may choose to deviate from agreements as written to address changing interests and updated calculations (Lyons Reference Lyons2015). These deviations become more likely as attention shifts away from third-party preferences and toward localization of the peace process. Thus, states may prioritize peace agreement terms that reflect these imperatives over other terms that are in agreements, including those that address women’s interests and needs.

Compliance with the terms of peace agreements is also more difficult when the terms constitute greater deviations from the status quo (Ozcelik Reference Ozcelik2020). Thus, provisions focusing on women or gender are less likely to be implemented when ideas of gender inclusion and equality deviate substantially from existing law and practice and when there is less organic domestic interest and support for such provisions. In other words, the implementation of gender-inclusive provisions may be less likely when belligerents are pressured into including these terms, possibly by third parties or even domestic actors, than when those issues are inherently of interest to one or both sides. Stedman et al. (Reference Stedman, Rothchild and Cousens2002) argue that “peace agreements are quintessential coalition-based documents that stem in part from demands of constituencies beyond the warring parties themselves.” Taking these preferences into account can lead to the inclusion of terms that cater specifically to third parties but do not reflect the interests of conflict actors. Downs and Stedman (Reference Downs, Stedman, John, Rothchild and Cousens2002) suggest that due to the advocacy of human rights NGOs, peace processes after the 1990s may have been overly ambitious in their inclusion of provisions aimed at improving women’s rights, in addition to other key human rights concerns, such as child soldiering and de-mining. Similarly, Stedman et al. (Reference Stedman, Rothchild and Cousens2002) suggest the integration of such terms may hinder implementation. Given limited resources and short time horizons, implementing parties often lack the motivation or ability to address these goals (Downs and Stedman Reference Downs, Stedman, John, Rothchild and Cousens2002). So, despite their inclusion in an agreement, supplemental provisions may be given short shrift during implementation.

Post-agreement, when implementing parties contend with resource constraints and the need to address commitment problems adequately, parties may decide to deprioritize the provisions that were included to placate the disparate coalitions and factions that emerged during the peace process – including those that improve women’s lives – in lieu of security-related provisions. We contend, however, that decisions to deprioritize gender-inclusive peace terms are short-sighted given the groundswell of evidence that boosting women’s rights, welfare, political participation, and economic empowerment can be a boon to peace durability and post-conflict stability (Krause et al. Reference Krause, Krause and Bränfors2018; O’Reilly et al. Reference O’Reilly, Ó Súilleabháin and Paffenholz2015; Tamaru and O’Reilly Reference Tamaru and O’Reilly2018). These findings provide evidence that gender-inclusive peace terms are security-related provisions. However, parties in conflict rarely see it this way. Given that an immediate focus on demobilizing and integrating former belligerents as a security guarantee is often prioritized, even well-meaning actors are unlikely to rush to implement terms that they view as peripheral or ancillary to the goal of immediate peace. Thus, we can expect that, on average, gender-inclusive provisions will not be among the first terms implemented in most peace processes.

Echavarría Álvarez et al. (2022) find that fewer gender-conscious provisions have been implemented than what they term “general” provisions. Joshi et al. (Reference Joshi, Olsson, Gindele, Alvarez and McQuestion2020) find that despite an unprecedented number of gender-specific stipulations included in Colombia’s comprehensive peace agreement, only 9% of these provisions were fully implemented three years after the accord was signed, compared to 25% of non-gender-specific terms. Whereas 33% of non-gender-specific terms were uninitiated after three years, more than 47% of Colombia’s gendered peace terms had not yet begun by 2019. Only 7% of the agreements inked during the years 2000–2016 included any specific guidelines for implementing the gender-inclusive provisions incorporated into agreements (UN Women 2018, 33), which offers additional insight into the poor track record for the implementation of gender-inclusive peace terms. These statistics suggest a significant difference in how gender-inclusive provisions are approached compared to non-gender-inclusive terms.

Whether and how rebels view implementing gender provisions remains underexplored. In general, we expect that agreement terms – especially those rebels advocate for – are more likely to be prioritized during the implementation phase when rebel group affiliates meaningfully participate in the government. We argue this can happen through several channels, but we focus on institutions where rebels take part in the administration of the state. We pay particular attention to cases where rebels gain access to power through post-conflict elections for two primary reasons. First, the election of rebel parties to legislatures fits broadly within the concept of post-conflict powersharing. Second, when rebels are elected, they have a popular mandate and may have more public support for the policies they advocate for. This public support may put greater pressure on the state and other powerbrokers to remain faithful in the implementation process. It can also give rebels political cover for demanding the implementation of certain provisions. These avenues ensure that rebels have influence over which provisions are implemented and how.

Further, we expect that rebels’ motivation to implement provisions may vary by provision type. Rebels are not only interested in implementation to gain the personal benefits they are allotted in peace agreements, but they also push for implementation to placate their civilian audiences, who typically prefer peace over continued war (Prorok and Cil Reference Prorok and Cil2022). Studies suggest former rebel parties become more inclusive and more moderate after they transition because of their need to woo voters and broaden their support bases (Storm Reference Storm2020). Maintaining public support becomes even more important as rebels eye future electoral competitions. Moreover, Bramble and Paffenholz (Reference Bramble and Paffenholz2020, 37) remind us that public support for peace agreements is essential, as elite-focused processes may still fail on popular referendum, as they did in both Guatemala and Colombia. Additionally, scholars have argued that where civilians doubt the trustworthiness of government promises of implementation, rebel groups can act as brokers of legitimacy for the state to ensure the viability of the peace process from which they stand to benefit (Breslawski Reference Breslawski2023; Dyrstad et al. Reference Karin, Bakke and Binningsbø2021). Thus, given both rebels’ electoral incentives and their interest in maintaining the legitimacy of the peace process, a rebel organization can use the implementation of a peace accord to appeal to its civilian supporters.

We argue that women representatives in former rebel parties can play an important role in gaining civilian buy-in for the peace process writ large, as women have been found to increase acceptance of peace deals among conflict-affected populations (O’Reilly et al. Reference O’Reilly, Ó Súilleabháin and Paffenholz2015). At the same time, we also expect women’s inclusion in rebel parties to impact that organization’s willingness to implement gender-inclusive peace terms. Indeed, in Sub-Saharan Africa, transitional powersharing arrangements where rebel groups have participated in the government have been associated with improvements in women’s empowerment and equal access to power more broadly (Johnson Reference Johnson2023). We unpack this to understand how women’s representation may be creating such an effect. In the following sections, we discuss research on when and how gendered provisions are implemented and then consider how women’s inclusion in legislatures impacts implementation, including women’s national representation, women’s representation in rebel parties, and specifically the inclusion of female ex-rebels in rebel parties.

3 The Implementation of Gender-Inclusive Provisions

While gender-inclusive peace agreement provisions tend to see lower levels of implementation on average (Echavarría Álvarez et al. 2022; Joshi et al. Reference Joshi, Olsson, Gindele, Alvarez and McQuestion2020), some conflicts do see the implementation of these provisions. Not only is there variation in warring parties’ initial willingness to incorporate gender-inclusive peace terms in agreements (Anderson Reference Anderson2015; Krause et al. Reference Krause, Krause and Bränfors2018; Thomas Reference Thomas2023), but as discussed, parties also vary in their willingness to implement these terms after wars end. We argue that the composition of the potential implementing contingent influences whether gender-inclusive provisions are given attention during peacetime. We believe women will be able to have greater influence over the implementation process when they are among the political insiders or powerbrokers.

When women participate in post-conflict governments, especially under the aegis of former rebel parties, advocacy for gendered provisions will not fall only to women from the incumbent government or third-party groups but can be taken up by those affiliated with former rebels and their coalitions. Expanding the government in this way ensures that a broader set of women have input in the implementation process, which should increase the chance that gender-inclusive provisions are implemented. Moreover, Joshi and Quinn (Reference Madhav and Quinn2015, 874) assert that in a viable implementation process, “outside groups generally lose support to political leaders now on the inside who are seen as exercising more power in the current political arrangement.” Since women rebel party representatives constitute part of the primary warring faction and a core component of the current political constellation, their preferences and advocacy will be harder to sideline than the preferences and interests of third parties (e.g., civil society). This should benefit the implementation of gender-inclusive provisions.

We present a three-fold argument that specifies conditions under which gendered peace provisions are most likely to be implemented. First, women’s national representation will influence the implementation of gendered peace provisions. Second, women’s representation in rebel parties will improve the overall implementation of gendered peace agreements. Third, we argue that women representatives who served in the rebel group during the war will be even more effective at promoting implementation. Throughout these arguments, we focus on how these factors help solve the primary issues that affect implementation: commitment problems and resource allocations in the face of constraints. We discuss these ideas in turn.

3.1 Women’s National Representation

Domestic actors have been responsible for ushering in unprecedented changes in women’s rights after civil conflicts across the globe, but especially in Africa (Tripp Reference Tripp2016). Peace agreements create windows of opportunity for local women to push for substantial changes in gender regimes after war (Tripp Reference Tripp2015, Reference Tripp2016). Women’s pressure and advocacy during the negotiation process have been instrumental in securing provisions that advance women’s rights in peace agreements (Ellerby Reference Ellerby2013; Krause et al. Reference Krause, Krause and Bränfors2018; Reid Reference Reid2021; True and Riveros-Morales Reference True and Riveros-Morales2019). African women activists have paved the way for significant changes in the post-agreement period as well. Rwandan women, for example, lobbied to be included in the post-conflict political environment after the country’s civil war and genocide (Hogg Reference Hogg2009; Mageza-Barthel Reference Mageza-Barthel2016; Powley Reference Powley2003). Largely owing to their participation in drafting the state’s post-conflict constitution and voting guidelines, Rwandan women were able to cement several consequential political changes, including a legislative quota and the establishment of a ministry of women’s affairs.Footnote 8 Notably, the country instituted a quota mandating that 30% of the seats in their lower and upper parliament chambers would be set aside for women. The first post-conflict election in 2003 far surpassed this goal, with nearly 49% of the lower house being comprised of women (Devlin and Elgie Reference Devlin and Elgie2008; Powley Reference Powley2003). Although the series of agreements that were signed in 1992 and 1993 between the Republic of Rwanda and the Revolutionary Patriotic Front were not particularly notable for their gender inclusiveness, women’s leadership in the post-conflict government led directly to the implementation of the gendered terms written into the various agreements. For instance, an October 1992 agreement called on the government to create the Ministry of Family Affairs and Promotion of the Status of Women.Footnote 9 In 1994, the RPF formed the new Ministry of Women and Family Protection with Aloisea Inyumba, former RPF finance commissioner, at the helm as minister (Hunt Reference Hunt2017). According to politician Fatuma Ndangiza, in the early days after the transition, “the ministry was spearheading women’s advancement, gender equality, organizing from grassroots to the national level, empowering women in civil society” because there was not a preexisting blueprint (Hunt Reference Hunt2017, 110). Many of the ministry’s early initiatives aimed at concentrating power into women’s hands and promoting women’s issues were eventually integrated into the constitution as permanent institutions.

The Rwandan case makes plain that an inclusive process is also important at the implementation stage. By contrast, experts suggest implementation is compromised when important groups, including women, are excluded (UN Women 2018). Evidence also demonstrates that accords are likelier to be implemented when women are at the table during peace processes (Krause et al. Reference Krause, Krause and Bränfors2018; O’Reilly et al. Reference O’Reilly, Ó Súilleabháin and Paffenholz2015). Krause et al. (Reference Krause, Krause and Bränfors2018), for instance, find that when women are among an agreement’s signatories, accords tend to include a greater range of terms, including those deemed vital for post-conflict stability (e.g., ceasefire commitment, disarmament, demobilization, reintegration, verification and monitoring, human rights, institutional reforms, development, women’s rights). When women hold a salient formal role within the peace process as agreement signatories, these terms are generally also more likely to be implemented. Thus, women’s representation in the peace process is central to the agreements’ successful implementation.

We expect, then, that in post-conflict contexts, women legislators will also have a positive effect on the implementation of gender peace provisions. Moreover, when more women are elected at the national level, the average implementation rate of gender peace provisions will be higher.

3.2 Women’s Representation in Rebel Parties

Though generally, we expect women legislators to positively affect implementation, the core of our argument is concerned with women represented in the former belligerent parties, whom we expect to have an even greater effect. To date, researchers and practitioners have focused largely on the important role civilian women play during peace processes. This emphasis is grounded in the idea that the civilian public is viewed as both a consequential stakeholder and a guarantor of peace (Braniff Reference Braniff2012). Indeed, scholars have demonstrated that women within civil society have left an indelible mark on shaping and implementing peace accords (Anderson Reference Anderson2015; Krause et al. Reference Krause, Krause and Bränfors2018). Civil society can facilitate information gathering, which contributes to effective monitoring and verification of implementation progress (Ross Reference Ross2017), particularly in inclusive processes (Verjee Reference Verjee2020). Women’s participation in these monitoring teams has been crucial. For example, Barsa et al. (Reference Barsa, Holt-Ivry and Muehlenbeck2016) argue that the women integrated into South Sudan’s Monitoring and Verification Mission, including in community liaison positions, enhanced the mission’s trust-building capabilities, ultimately improving the mission’s ability to garner information from within conflict-affected communities. This increased transparency and information-gathering capability had a direct impact on the implementation of key parts of South Sudan’s 2014 Cessation of Hostilities agreement, including obligations on the protection of civilians, as well as those regarding gender-based and sexual violence. Yet, when women lack a clear role during peace negotiations, it is often more difficult for them to find a concrete post-conflict role (Schädel and Dudouet Reference Schädel and Dudouet2020).

While the focus on the impact of and strategies to get more civil society women involved in peace processes is warranted, existing research has been myopic. It overlooks the potential opening that other women – particularly those aligned with rebel parties – may be able to use to get into the peace process. Our argument highlights the role women representatives from rebel parties play in the implementation process. In doing so, we do not aim to detract from the importance of women in civil society. Instead, we draw attention to another influential grouping of women that has largely been overlooked. While we argue that female representatives from former rebel parties have an advantage over other legislators in their push for the implementation of gender-inclusive peace terms, we also argue that women leaders, including those from civil society groups, constitute an important part of the implementation coalition that ultimately sees gender-inclusive provisions implemented.

Research suggests peace agreements are most likely to be implemented and peace is expected to be more durable when rebels share power in the wake of conflict termination. Rebels’ participation in post-conflict elections has been found to reduce the likelihood of conflict recurrence and encourage democratization (Manning et al. Reference Carrie, Smith and Tuncel2024), while the exclusion of a major rebel party from a post-conflict government can increase the chance that peace fails and violence resumes (Marshall and Ishiyama Reference Marshall, Ishiyama and Ishiyama2018). Failing to include rebels meaningfully in post-conflict governments can exacerbate credible commitment problems and incentivize rebels to act as spoilers. Joo (Reference Joo2025) argues that rebels’ participation in electoral politics can alleviate the dual commitment problem that exists after civil wars; powersharing arrangements can allay both governments’ and rebels’ fears. Participation in the country’s inclusive institutions can enable former rebel groups to attain policy concessions, which can incentivize them to stick to peace. These incentives reduce the government’s fears that rebels will turn back to war. Rebel parties’ participation in state governance also allays rebels’ fears that the government will renege on promises made during the peace negotiations. Governments that fail to uphold war-ending bargains risk not only renewed conflict but also electoral consequences of allowing peace to fail. Thus, governments that allow rebels to transition into rebel parties have strong incentives to accommodate rebel preferences and interests to forestall rebels’ spoiling behavior.

In post-conflict settings, where states are keen to maintain peace and avoid conflict recurrence, the government has incentives to not only allow rebel groups to participate in a post-conflict government but assure rebels they have a true stake in the policy-making process. Offering these veto players (and their representatives) a stake in the political process can reduce armed groups’ incentives to return to conflict (Mukherjee Reference Mukherjee2006). States have similar incentives to carve out specific roles for former rebels in the implementation process to increase their buy-in to peace (Molloy and Bell Reference Molloy and Bell2019). As only veto players have a credible threat to “continue the war unilaterally, if one or more of these actors are not included in a peace process” (Cunningham Reference Cunningham2013, 42), post-conflict governments do not have the same incentives to accommodate the preferences of non-veto player parties. Prioritizing rebel parties’ preferences for the sake of post-conflict stability should diminish the influence of non-rebel parties relative to that of former rebel parties. We argue this dynamic will produce benefits for female legislators from rebel parties, which can be used to influence the implementation of gender peace terms.

We assert that gender-inclusive peace terms are more likely to be put into force when women are active in the implementation process, when they have access to the reins of power, and when gender-inclusive provisions are compatible with at least one of the primary warring parties’ interests. This last point is especially crucial since implementers often prioritize the interests and needs of the primary belligerents over others’ prerogatives in the wake of a conflict. For example, Verjee (Reference Verjee2020, 8) reports that Sierra Leone’s Commission for the Consolidation of Peace (CCP), one of its two monitoring and verification missions, was hamstrung by the preeminence of the warring factions within the institution. According to a former commissioner for the CCP, there were “no women in the commission, no disabled as a result of the war. People were thinking largely about warring factions. But we felt we [as civil society] had something to offer, and we had had a huge engagement in the peace process … We could have been very powerful, but the real power was with the [Revolutionary United Front] RUF and [Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC) leader Johnny] Koroma.” Likewise, during the negotiation of Mali’s 2015 Algiers Accord, under pressure to reach a timely deal, both the warring parties and third parties eschewed an inclusive process, which effectively shut out civil society and cut off a primary path for women’s involvement (Schädel and Dudouet Reference Schädel and Dudouet2020). According to Kew and Wanis-St. John (Reference Kew and Wanis-St John2008, 18) “government and militant leaders, political party heads, warlords, and the usual cast of political elites driving the main forces in dispute – the ones with the guns – still get the lion’s share of attention from international mediators,” which has stymied the influence of local civil society groups.

O’Reilly et al. (Reference O’Reilly, Ó Súilleabháin and Paffenholz2015) contend that although peacebuilding requires input from the broader society, “women – who are rarely the belligerents – are unlikely to be considered legitimate participants” in ending violence. Civilian women may be viewed as lacking authority in the security domain especially, which can impair their ability to participate in the implementation of such provisions. Bramble and Paffenholz (Reference Bramble and Paffenholz2020) argue that, although civil society can contribute meaningfully to security sector reform, female civil society actors’ formal participation has been extremely limited due to the belief that they lack the network and technical capacity to contribute meaningfully to important security initiatives. They argue that, in the past, “extremely sensitive processes relating to decommissioning and intelligence reform that affect the safety of armed groups and the security of the state remained off-limits for civil society participation other than the advisory role of academic experts” (Bramble and Paffenholz Reference Bramble and Paffenholz2020, 31). When women from civil society are allowed to participate in implementation, they may be limited in the types of tasks they can contribute to. In essential areas like security sector reform, legitimacy is often accorded to actors that have participated in a conflict as militants. While this possibly unfounded set of assumptions may constrain women from civil society, it can allow women from former rebel parties to play a more important role in the implementation process, especially regarding security sector reforms.

Female legislators from rebel parties are less likely to face these same impediments. Given their links to one of the primary warring factions, female legislators who represent rebel parties will have greater dominion over the peace process than female legislators without links to a warring party. Rebel party women legislators can draw on the authority of warring parties to stake a claim to the implementation process. At the same time, we argue that female legislators will be more likely to push for gender provisions than male legislators from the same party. While rebel party men can advance women’s interests, we argue that women politicians will be more likely to push gender-inclusive provisions and encourage other parties to do so as well. Though women are not a monolith and, thus, will not always prioritize or favor policies regarding women or gender, there is ample research that makes the connection between women’s descriptive representation and their substantive representation (Celis et al. Reference Celis, Childs, Kantola and Krook2008; Foos and Gilardi Reference Foos and Gilardi2020; Gilardi Reference Gilardi2015; Hinojosa Reference Hinojosa2012; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999; Paxton and Kunovich Reference Paxton and Kunovich2003; Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2003; Wolbrecht and Campbell Reference Christina and Campbell2007). This work demonstrates women’s representation within political institutions can alter the focus on policy issues relevant to women and gender (Childs Reference Childs2004; Dodson Reference Dodson2006; Greene and O’Brien Reference Zachary and O’Brien2016; O’Brien and Piscopo Reference O’Brien and Piscopo2019; Piscopo Reference Piscopo2011). This may be because women representatives have a genuine interest in issues related to women and gender (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999), they see themselves as responsible for representing the interests of women (Childs Reference Childs2004; Franceschet and Piscopo Reference Susan and Piscopo2008; Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2010), or because they fear backlash for failing to conform to gendered expectations that they represent “feminine” and “communal” issues (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002). Even when they prioritize similar issues, male and female legislators’ stances and areas of emphasis diverge (Greene and O’Brien Reference Zachary and O’Brien2016). Moreover, women’s integration has been found to encourage parties to take up both a greater range of issues and shift parties’ positions on left-leaning issues (Greene and O’Brien Reference Zachary and O’Brien2016). Extrapolating to peace agreement provisions, women legislators may encourage their parties to view a greater range of issues as important and adopt more leftist policy positions, namely those that address women’s rights and welfare and the disadvantaged. Thus, women representatives may be more likely to advocate for the implementation of gendered peace provisions when in government, especially when these provisions also align with the interests of the rebel movement and their supporters.

The election of female candidates can indicate a norm shift, which encourages all parties that hope to contend in elections to take women’s interests and issues seriously to gain vote share. Catalano-Weeks (Reference Weeks2018) argues that even male-dominated parties are incentivized to pursue gender-inclusive legislation, such as quotas, in the face of heightened competition. Thus, we might expect that when female candidates are elected, parties will perceive women’s issues as more salient concerns to the public, compelling them to adopt these policy positions as well. If this is the case, rebel parties will not be the only political factions to advocate for gender-inclusive peace terms; the election of women candidates may also affect the priorities of parties that do not share a deep ideological or political commitment to ensuring equality for women. However, given the crucial role of former rebels in implementation, we expect women representatives’ statuses in rebel parties to increase their overall influence on the process with downstream consequences for implementation.

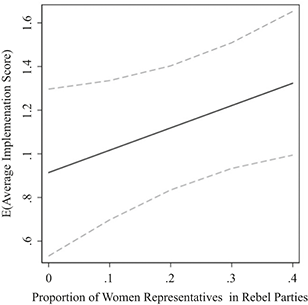

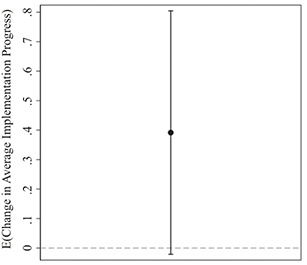

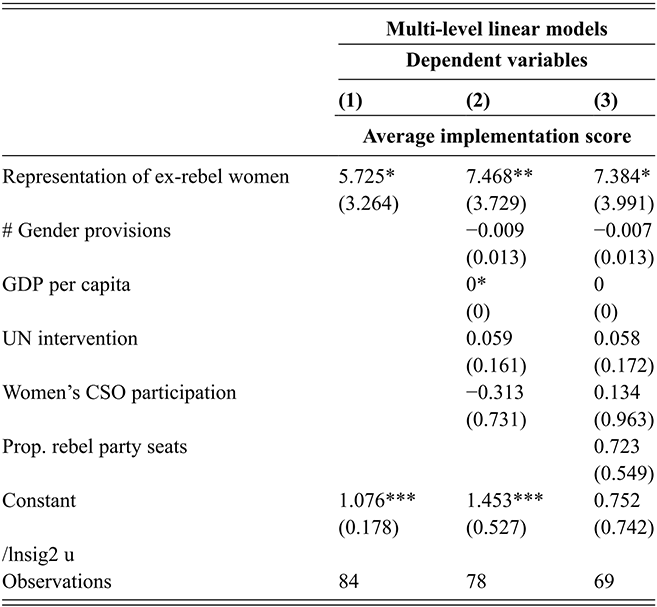

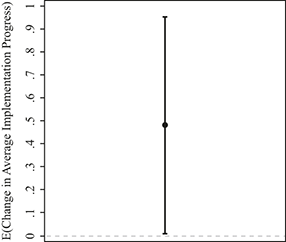

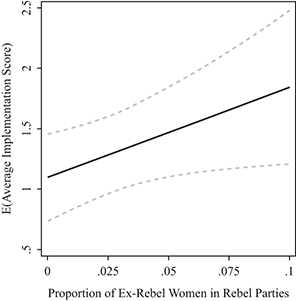

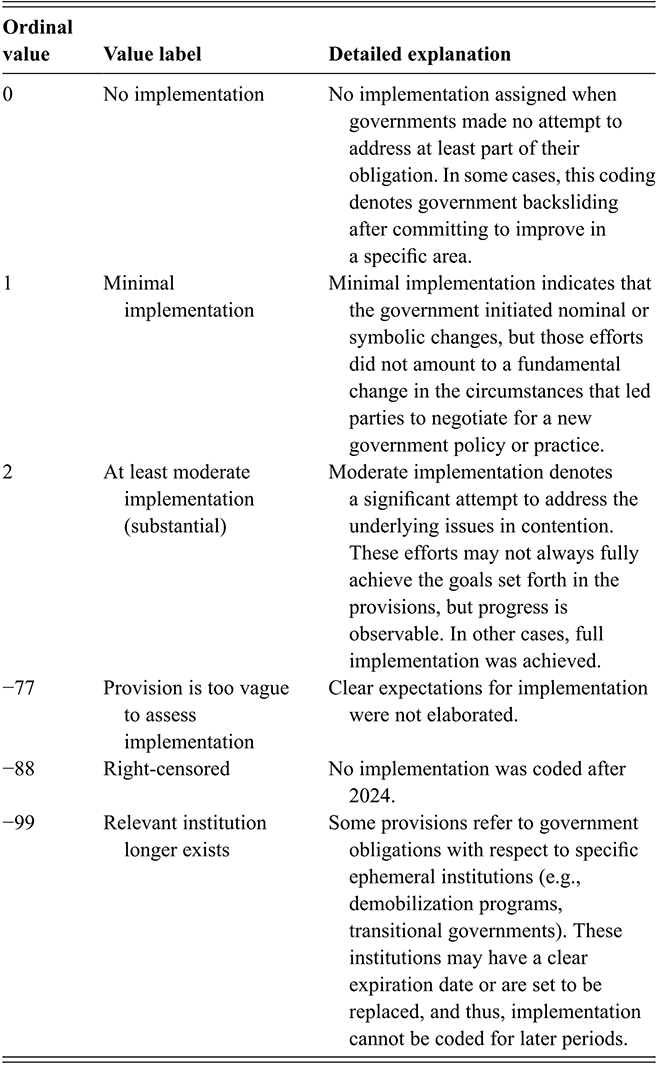

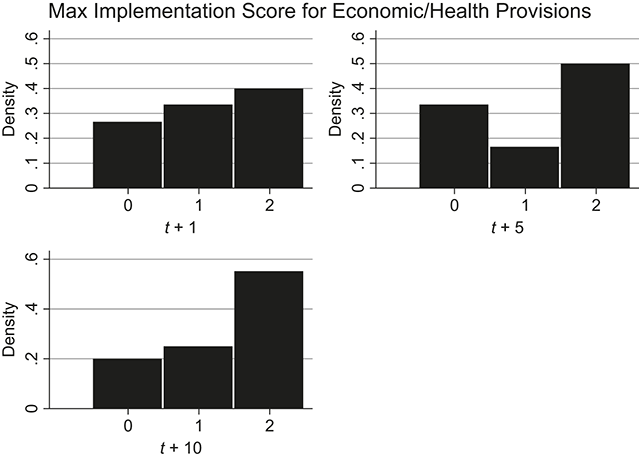

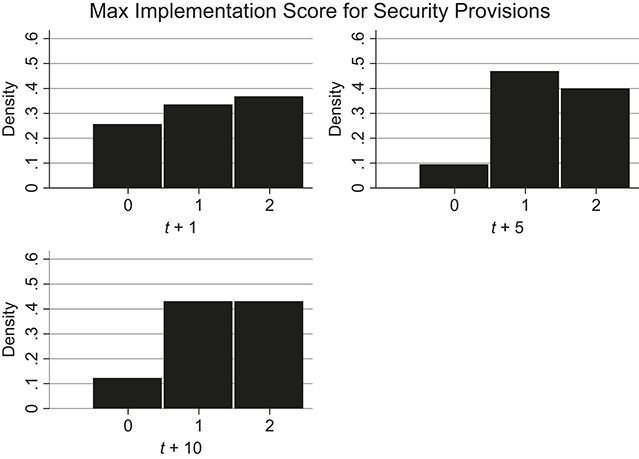

Finally, women participants can make these organizations appear more trustworthy, committed to peace, and more appealing to domestic and international parties (Berry Reference Berry2015, Reference Berry2018; Brannon Reference Brannon2023). We argue rebel parties’ quests for the benefits of women’s support can manifest in their post-conflict recruitment and the policies they prioritize after wars. Studies suggest that women – especially in politics – are viewed as more trustworthy than men (Barnes and Beaulieu Reference Barnes and Beaulieu2014; Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993; Sanbonmatsu Reference Sanbonmatsu2002), which may influence their ability to shape the implementation of peace. In Rwanda, women were seen as “less corruptible” and more committed to reconciliation and peace, which is part of the reason they were appealing recruits for the RPF (Powley Reference Powley2003). Similarly, in Liberia, women activists campaigned on behalf of women candidates, arguing that while men were responsible for the conflicts, women would promote peace (Massaquoi Reference Massaquoi2007). Brannon (Reference Brannon2023) shows that rebel parties consistently run and elect more women than other political parties, arguing that these parties use women representatives to frame the party as more trustworthy and committed to peace by exploiting peaceful feminine stereotypes. Assumptions that women representatives within these rebel parties will promote and successfully impact peace may enhance their ability to successfully do so once in office, creating a pathway for women representatives in rebel parties to promote implementation.