By the year 2050, the percentage of older adults represented within the global population is projected to nearly double, from 12–22 per cent (World Health Organization, 2017). Although aging is associated with a variety of physical health issues, the simultaneous negative impact of mental health symptoms, such as depression, are often overlooked (World Health Organization, 2017). This is despite research suggesting that 10–15 per cent of older adults experience depressive symptoms as well as an additional 2 per cent being diagnosed with major depressive disorder (Kok & Reynolds, Reference Kok and Reynolds2017). Depression affects various aspects of one’s well-being including overall quality of life, demonstrated by the finding that an 8.3 quality-adjusted life year gap exists between older adults with depression and those without (Jia & Lubetkin, Reference Jia and Lubetkin2017).

Older adults are at a heightened risk of experiencing both social isolation and loneliness, because of (among other things) the death of friends and family, mobility-related issues, and cognitive decline (Coyle & Dugan, Reference Coyle and Dugan2012). Often, loneliness and social isolation are studied as separate entities, as social isolation is often understood as an objective state relating to the number of social relationships or frequency of contact with others, whereas loneliness is understood as a subjective emotional state (Newall & Menec, Reference Newall and Menec2017). However, Newall and Menec (Reference Newall and Menec2017) argue that although one could experience loneliness without social isolation, or vice versa, researching both objective circumstances and subjective feelings together may provide a more holistic understanding of mental health, especially with respect to the outcomes of intervention studies. For example, having fewer social relationships does not necessarily mean that one experiences loneliness, as long as one has the social relationships that they desire; therefore, increasing the number of social relationships that one has may not equate to decreased feelings of loneliness (Newall & Menec, Reference Newall and Menec2017). Nonetheless, loneliness and social isolation are associated with one another (Shankar, McMunn, Demakakos, Hamer, & Steptoe, Reference Shankar, McMunn, Demakakos, Hamer and Steptoe2017), and are often related to greater feelings of psychological distress, symptoms of depression, and poor physical health (Alpert, Reference Alpert2017; Taylor, Taylor, Nguyen, & Chatters, Reference Taylor, Taylor, Nguyen and Chatters2016; van Beljouw et al., Reference van Beljouw, van Exel, de Jong Gierveld, Comijs, Heerings and Stek2014). Factors associated with loneliness in older adults include social isolation, gender, ethnicity, socio-economic status, and poor mental health (Cohen-Mansfield, Hazan, Lerman, & Shalom, Reference Cohen-Mansfield, Hazan, Lerman and Shalom2015). Taken together, potential remedies for social isolation and loneliness should consider both subjective and objective dimensions, while also taking other social determinants of health into consideration.

Current Options for the Treatment of Depression among Older Adults

As major depressive disorder exists on a spectrum of severity, treatment options also vary widely (Skultety & Zeiss, Reference Skultety and Zeiss2006). This is coupled with the issue that many treatment options are often required, because almost 70 per cent of older adults do not respond directly to antidepressant medication and are in need of supplementary treatment (Kok & Reynolds, Reference Kok and Reynolds2017). Although drug therapy is commonly used, it may not be the most suitable option for older adults with depression because of the high potential for co-morbidity with other chronic conditions that require medication, which may result in unanticipated drug interactions (Kok & Reynolds, Reference Kok and Reynolds2017). Cognitive behavioural therapy has been shown to be effective in treating depression, especially in a group setting (Wuthrich, Rapee, Kangas, & Perini, Reference Wuthrich, Rapee, Kangas and Perini2016). However, commonly reported barriers to pursuing therapy include the costs associated with therapy, doubts regarding the usefulness of treatment, and a perception of indifference amongst therapists (Wuthrich & Frei, Reference Wuthrich and Frei2015). Ultimately, other types of treatments must also be considered.

One cost-effective treatment option (with few side effects) that is gaining ground is the idea that one’s social group memberships and relationships can be effective remedies for many psychological health ailments—in the literature, this phenomenon has come to be known as the “social cure” (Haslam et al., Reference Haslam, McMahon, Cruwys, Haslam, Jetten and Steffens2018; Jetten, Haslam, & Haslam, Reference Jetten, Haslam and Haslam2012). However, although actively maintaining social group relationships is believed to reduce loneliness and depression (Cruwys, Haslam, Dingle, Haslam, & Jetten, Reference Cruwys, Haslam, Dingle, Haslam and Jetten2014; Newall et al., Reference Newall, Chipperfield, Clifton, Perry, Swift and Ruthig2009), there is a wide range of potential barriers—environmental, psychological, and economic—that may prevent older adults from doing so (Nicholson, Reference Nicholson2012). For example, environmental or economic barriers such as living alone, on a fixed income, or in a rural location might decrease one’s social network activity substantially (Nicholson, Reference Nicholson2012). Other psychological and physical barriers may include widowhood, cognitive decline, and sensory loss (Nicholson, Reference Nicholson2012). As such, it is important to explore potential treatment options that help older adults to maintain their social relationships, while ensuring that the various barriers they encounter, such as issues with mobility and health concerns, are taken into consideration (Nef, Ganea, Müri, & Mosimann, Reference Nef, Ganea, Müri and Mosimann2013).

Social Technology: A Newer Alternative

One way for older adults to potentially mitigate the negative effects of loneliness and social isolation, while addressing some of the barriers that they face, may include the use of social networking sites (e.g., Facebook, Twitter) or other technology-based communication systems (e.g., e-mail, Skype). Indeed, introducing the use of social networking as a way of alleviating loneliness and feelings of social isolation may reduce the likelihood of developing major depressive disorder or experiencing depressive symptoms (Fokkema & Knipscheer, Reference Fokkema and Knipscheer2007). Assistive technology as an intervention has been used in other domains with the goal of improving the lives of older adults through, for example, maintaining cognitive integrity (Myhre, Mehl, & Glisky, Reference Myhre, Mehl and Glisky2017), enhancing physical health (Mackert, Mabry-Flynn, Champlin, Donovan, & Pounders, Reference Mackert, Mabry-Flynn, Champlin, Donovan and Pounders2016), and even receiving behavioural treatment for depression (Lazzari, Egan, & Rees, Reference Lazzari, Egan and Rees2011). Likewise, the use of online social networking has helped both to create new relationships and to strengthen existing relationships (especially with younger generations such as grandchildren; Berg, Winterton, Petersen, & Warburton, Reference Berg, Winterton, Petersen and Warburton2017), has been associated with decreased social isolation (Hajek & König, Reference Hajek and König2019), and has been shown to mitigate the effects of loneliness among older adults significantly (Mickus & Luz, Reference Mickus and Luz2002; Quinn, Reference Quinn2013). Online social networking has also been described as a platform to connect with other older adults at any time of day, serving as an opportunity to connect with people around the world, and ultimately decrease feelings of loneliness (Ballantyne, Trenwith, Zubrinich, & Corlis, Reference Ballantyne, Trenwith, Zubrinich and Corlis2010).

Nonetheless, although some research suggests that online social networking has a positive impact on older adults, other research findings in this area are inconclusive, especially because of a relative lack of research conducted specifically on the mental health of older adults using online social networking sites (Nef et al., Reference Nef, Ganea, Müri and Mosimann2013; Neves, Franz, Judges, Beermann, & Baecker, Reference Neves, Franz, Judges, Beermann and Baecker2017). Likewise, research on the relationship between the mental health of older adults and social technology usage may be inconclusive because of a lack of a consensus on how social connectedness outcomes are defined (e.g., loneliness, social isolation, and social participation) and a lack of investigation into the variety of technologies used for communication (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Warburton, Waycott, Batchelor, Hoang and Dow2018). In this regard, communicating with online communities may decrease time spent with family (Sum, Mathews, Pourghasem, & Hughes, Reference Sum, Mathews, Pourghasem and Hughes2008), lead to mixed outcomes based on types of social relationships formed (Hage, Wortmann, van Offenbeek, & Boonstra, Reference Hage, Wortmann, van Offenbeek and Boonstra2016), and may decrease feelings of social isolation without any impact on depression (Saito, Kai, & Takizawa, Reference Saito, Kai and Takizawa2012). Other research has shown that the use of online social networking sites may be linked to decreased depression when the symptoms are severe, but not when they are mild (Kim, Lee, Christensen, & Merighi, Reference Kim, Lee, Christensen and Merighi2015). Inconsistent findings have also emerged related to factors that could influence the association between mental health and online social networking site usage, such as the ethnicity, socio-economic status, and gender of participants (Khalaila & Vitman-Schorr, Reference Khalaila and Vitman-Schorr2018; Minagawa & Saito, Reference Minagawa and Saito2014). Moreover, some older adults may be reluctant to use online social networking sites because of privacy concerns, lack of understanding of how to use the online platforms, and the lack of user-friendly options designed specifically for an older population (Lehtinen, Näsänen, & Sarvas, Reference Lehtinen, Näsänen and Sarvas2009; Nef et al., Reference Nef, Ganea, Müri and Mosimann2013). Indeed, there is some evidence that older adults may not be as motivated to engage in online social networking as their younger counterparts because of the aforementioned concerns (Nef et al., Reference Nef, Ganea, Müri and Mosimann2013). This inconclusive body of research hinders our capacity to fully understand potential associations between online social networking and depressive symptoms among seniors. Therefore, the objective of this scoping review was to gather, summarize, and better understand the existing literature on the use of online social networking and associations with mental health among older adults, in order to potentially inform future interventions, programming, and policies.

Methods

The scoping review methodology was based on the evaluation framework outlined by Arksey and O’Malley (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005).

Step 1: Identifying the Research Question

As stated, our research question was: “Is online social networking associated with depressive symptoms, social isolation, and/or loneliness among older adults?”

Step 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

To identify relevant studies, three members of the research team searched the following databases: PubMed, PsycINFO, and Scopus. These three databases were chosen in consultation with a library specialist because of their comprehensive collections of multidisciplinary articles, including the topics relevant to this scoping review. The search for related articles was done using the advanced search tool from each database, with a predetermined search string: (“mental health” OR loneliness OR depression OR “social isolation”) AND (elderly OR aging OR geriatric OR retired OR retirement OR seniors) AND (Internet OR e-mail OR social technol* OR "social media"). The timeline was limited to articles published between 2008 and 2018, in order to consider a comprehensive number of articles for review while also maintaining recency.

Step 3: Study Selection

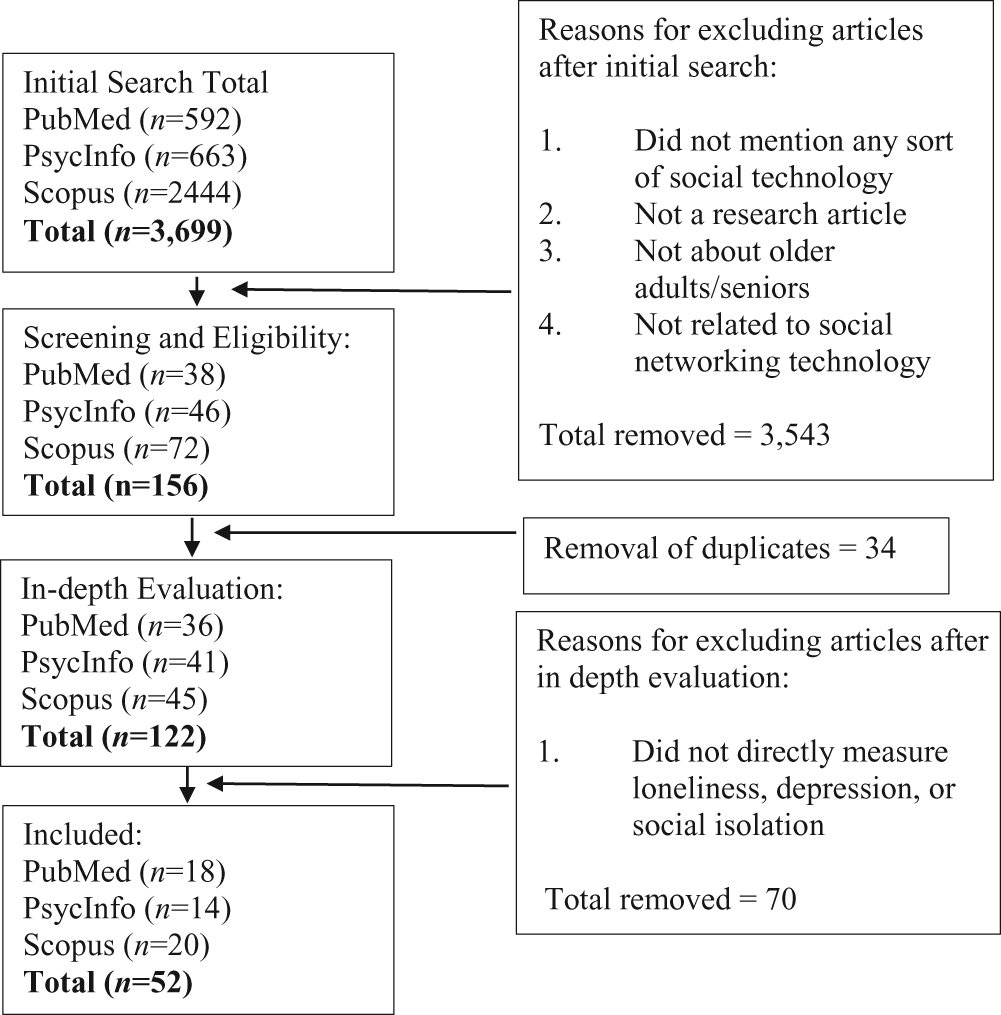

An initial search found 3,699 relevant articles in the databases: 592 from PubMed, 663 from PsycINFO, and 2444 from Scopus (Figure 1). These initial articles were screened based on their abstracts and titles, selecting those that focused on the links among aging (e.g., seniors, retirement), mental health (e.g., social isolation, loneliness, depression), and social technology (e.g., e-mail, social technology, social media). The types of studies included were quantitative and qualitative research, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, literature reviews, randomized control trials, and quasi-experimental, longitudinal, and mixed-method research. Exclusion criteria included outcome measures that were not relevant to mental health, the absence of social technology, or research examining technology that did not fit with social networking factors (e.g., assistive living technologies, robotics). Articles that were not research articles, such as book reviews and editorials, were also excluded. The exclusion criteria led to the overall removal of 3,543 articles, resulting in 156 articles remaining from the initial 3,699. Following this removal process, each of these 156 articles was explored in more depth, ensuring that its outcome variables directly measured depression, social isolation, and/or loneliness, and to remove any duplicates. After this in-depth evaluation, we removed 34 duplicates. As a result, 52 relevant articles remained for this scoping review. These remaining articles were once again reviewed and discussed among the researchers to ensure inter-rater reliability and consensus that every article met the inclusion criteria.

Figure 1. Flow chart of evaluation

Step 4: Charting the Data

The final selection of studies was catalogued into an Excel file that listed the study authors, country, year of publication, DOI, title, duration of intervention and comparison group (if applicable), study population, minimum sample age, sample size, aims of the study, methodology, outcome measures, relevant findings, social factors examined, and mental health outcomes. A simplified version of this spreadsheet summarizing each study’s authors, publication year, country, sample size, minimum sample age, social factor(s) examined, mental health outcome(s), and summary of findings relevant to the current scoping review is presented in Figure 1.

Step 5: Collating, Summarizing and Reporting the Results

Overall, the results of this scoping review led to the evaluation of 52 articles (Table 1). The majority of studies used a quantitative (n = 28), qualitative (n = 8), or mixed methods approach (n = 8). Of the quantitative and mixed methods articles, eight studies had some form of intervention with a control group; of those eight intervention studies, two had randomized sampling while the others were non-randomized. The remaining articles identified in this scoping review were systematic and/or literature reviews (n = 8). Research methods to evaluate the use of online social networking, levels of loneliness and depression, overall feelings of social connectedness, and well-being included self-report scales and interviews. The studies were mostly conducted in the United States (n = 15), with additional studies in Australia (n = 6), the United Kingdom (n = 5), New Zealand (n = 4), South Korea (n = 3), Spain (n = 2), Israel (n = 2), The Netherlands (n = 2), Finland (n = 2), (Brazil (n = 1), the Czech Republic (n=1), China (n = 1), Canada (n = 1), Hong Kong (n = 1), South Africa (n = 1), Taiwan (n = 1), Japan (n = 1), Sweden (n = 1), Norway (n = 1), and Northern Ireland (n = 1).

Table 1. Charted data of the 52 studies identified for this scoping review

Note. CMC= computer mediated communication; ICT = information communication technology; SNS = social networking site; QoL = quality of life.

Results

Based on analysis of the results presented in each of the 52 articles by members of the research team, potential themes were conceptualized. Subsequently, the team members discussed their findings amongst each other in order to reach a consensus on the final themes to be included. As a result, five key themes were generated (with some articles being relevant to more than one theme), including: (1) enhanced communication with family and friends, (2) positive associations with well-being and life satisfaction, (3) decreased depressive symptoms (4) greater independence and self-efficacy, and (5) creation of online communities (non-family relationships).

Enhanced Communication with Family and Friends

A total of 31 articles highlighted the theme of enhanced communication between family and friends. For example, Hogeboom, McDermott, Perrin, Osman, and Bell-Ellison (Reference Hogeboom, McDermott, Perrin, Osman and Bell-Ellison2010) found that the use of online social networking by older adults was positively associated with a greater frequency of communication with family and friends. Likewise, online social networking was associated with older adults communicating more often and having a stronger bond with family than older adults who did not use social technology as often (Berg et al., Reference Berg, Winterton, Petersen and Warburton2017). These authors noted that an advantage of online social networking is the ability to communicate regardless of geographic location (Berg et al., Reference Berg, Winterton, Petersen and Warburton2017; Hogeboom et al., Reference Hogeboom, McDermott, Perrin, Osman and Bell-Ellison2010). This was further supported by qualitative interviews, in which older adults often described the importance of online social networking because it made them feel less isolated and more connected to their families (Chen & Schulz, Reference Chen and Schulz2016; Chiu, Hu, Lin, Chang, & Chang, Reference Chiu, Hu, Lin, Chang and Chang2016).

Of the 31 articles included in this theme, 24 examined the effects that different social groups may have, such as family-related groups, friend-related groups, or both. Indeed, the results of these studies suggested that online social communication facilitated communication with both family and friends. For example, Berg et al. (Reference Berg, Winterton, Petersen and Warburton2017) concluded that the ease of use and availability of social media technology made it possible for older adults to talk with family members and friends who lived far away. Another 5 of the 31 articles (i.e., Blusi, Asplund, & Jong, Reference Blusi, Asplund and Jong2013; Cerna & Svobodova, Reference Cerna and Svobodova2017; Delello & McWhorter, Reference Delello and McWhorter2017; Khalaila & Vitman-Schorr, Reference Khalaila and Vitman-Schorr2018; Lehtinen et al., Reference Lehtinen, Näsänen and Sarvas2009) focused only on communication with family members. For example, Khalaila and Vitman-Schorr (Reference Khalaila and Vitman-Schorr2018) found that online social networking enhanced older adults’ abilities to connect with family, which was associated with lower rates of loneliness. Finally, 2 out of the 31 articles focused specifically on friends (Chopik, Reference Chopik2016; Forsman & Nordmyr, Reference Forsman and Nordmyr2017). Chopik (Reference Chopik2016) found that online social media facilitated online friendships, which was associated with lower levels of loneliness. Likewise, in conducting a systematic review, Forsman and Nordmyr (Reference Forsman and Nordmyr2017) found that a common theme across studies was that online social networking facilitated better interpersonal relationships.

Positive Well-Being and Life Satisfaction

Overall, 25 articles found an association between online social networking and increased well-being and life satisfaction. However, there appeared to be a lack of consensus on the strength of this association across studies. For example, some research (e.g., Forsman & Nordmyr, Reference Forsman and Nordmyr2017; Ihm & Hsieh, Reference Ihm and Hsieh2015) has found a strong association between Internet use and well-being because online social networking can enhance interpersonal relationships and increase access and feelings of belonging to the community. Conversely, other studies have found a lesser association between well-being and online social networking (Chipps, Jarvis, & Ramlall, Reference Chipps, Jarvis and Ramlall2017; Erickson & Johnson, Reference Erickson and Johnson2011; ten Bruggencate, Luijkx, & Sturm, Reference ten Bruggencate, Luijkx and Sturm2018; Woodward et al., Reference Woodward, Freddolino, Wishart, Bakk, Kobayashi and Tupper2013). For example, in a systematic review of 22 research studies, the association between online social networking and well-being could only be determined to be weak, because of the lack of strong non-correlational research (Chipps et al., Reference Chipps, Jarvis and Ramlall2017). Such disparities in findings might be attributed to the socio-economic status of study participants, as some research has demonstrated that individuals with lower socio-economic status and/or lower levels of education may not readily have access to digital devices (Ihm & Hsieh, Reference Ihm and Hsieh2015). In this regard, Erickson and Johnson (Reference Erickson and Johnson2011) found that the association between online social networking and well-being became non-significant after controlling for demographic characteristics, such as income and age. However, Quintana, Cervantes, Sáez, & Isasi (Reference Quintana, Cervantes, Sáez and Isasi2018) found a significant association between online social networking and well-being even when controlling for demographic characteristics.

Fewer Depressive Symptoms

The association between online social networking and fewer depressive symptoms was found in 18 of the 52 articles. However, as with the patterns associated with more positive well-being (noted previously), the strength of this relationship differed across studies, with some finding a significant association (Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Hu, Lin, Chang and Chang2016; Chopik, Reference Chopik2016; Cotten, Ford, Ford, & Hale, Reference Cotten, Ford, Ford and Hale2012; Díaz-Prieto & García-Sánchez, Reference Díaz-Prieto and García-Sánchez2016), while others did not (Erickson & Johnson, Reference Erickson and Johnson2011; Minagawa & Saito, Reference Minagawa and Saito2014). One longitudinal study found that Internet usage reduced the probability of depression by approximately 33 per cent (Cotten et al., Reference Cotten, Ford, Ford and Hale2012). Likewise, other correlational research has found a negative association between depressive symptoms and Internet usage (Choi & Dinitto, Reference Choi and Dinitto2013). However, this association was also found to be influenced by demographic characteristics, such as ethnicity and socio-economic status: racial minority groups were less likely to use the Internet, and education level was a strong predictor of Internet use (Choi & Dinitto, Reference Choi and Dinitto2013). In another study, the use of social technology was associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms, but this association only persisted among women when socio-economic status was taken into consideration (Minagawa & Saito, Reference Minagawa and Saito2014).

Greater Independence and Self-Efficacy

A positive association between online social networking and a greater sense of independence and self-efficacy was found in 15 of the 52 articles (e.g., Chen & Schulz., Reference Chen and Schulz2016; Woodward et al., Reference Woodward, Freddolino, Wishart, Bakk, Kobayashi and Tupper2013; Zhang, Reference Zhang2016; Zhou, Reference Zhou2018). Some older adults may be reluctant to use online social networking; however, doing so may help to increase levels of confidence (Delello & McWhorter, Reference Delello and McWhorter2017). For example, Woodward et al. (Reference Woodward, Freddolino, Wishart, Bakk, Kobayashi and Tupper2013) found that teaching older adults how to use online social technology allowed them to engage with online communities and interact with both family and friends. This also helped older adults with issues relating to mobility, as demonstrated by higher self-reported ratings of quality of life and self-efficacy (Woodward et al., Reference Woodward, Freddolino, Wishart, Bakk, Kobayashi and Tupper2013; Zhang, Reference Zhang2016). Additionally, online social technology was described as a platform for older Chinese adults to share culture, news, and media in their native language, which fostered a greater sense of independence because this removed potential difficulties associated with having limited English skills (Zhang, Reference Zhang2016). Greater awareness of current events has also empowered older adults by allowing them to engage in thought-provoking discussions and to make more informed decisions (Chen & Schulz, Reference Chen and Schulz2016). Specifically, among older cancer survivors, online social networking was used as a tool for empowerment by allowing them to find social contacts and health information (Lee, Kim, & Sharratt, Reference Lee, Kim and Sharratt2018).

Creation of Online Communities (Non-Family Relationships)

Finally, a total of 13 articles found that online social networking helped older adults to create new online communities with other older adults. This took place over platforms such as Facebook, as its simple interface provided an opportunity for the creation of entirely new online communities (Berg et al., Reference Berg, Winterton, Petersen and Warburton2017; Forsman & Nordmyr, Reference Forsman and Nordmyr2017). For example, online support groups were formed, which offered an opportunity to give and receive support from those with similar life experiences, such as the death of a loved one (Berg et al., Reference Berg, Winterton, Petersen and Warburton2017). Other types of life experiences that older adults have discussed in their online communities are challenges experienced with aging, such as a loss of mobility or eyesight (Forsman & Nordmyr, Reference Forsman and Nordmyr2017). These communities offered a place for older adults to joke about dealing with these age-related issues and receive information about how to get additional help or resources to overcome them (Forsman & Nordmyr, Reference Forsman and Nordmyr2017). In these online communities, individuals do not often meet the people with whom they are interacting face to face; however, participants often perceived their online social relationships to be as important as close in-person friends or family (Forsman & Nordmyr, Reference Forsman and Nordmyr2017; Lehtinen et al., Reference Lehtinen, Näsänen and Sarvas2009).

Discussion

Within the 52 articles included in this scoping review, five themes were identified that can be captured in two overarching categories; namely (1) mental health and (2) social connectedness. Mental health was discussed in terms of three main themes: depression, autonomy/self-efficacy, and subjective well-being. Social connectedness was further discussed in

two main themes: the creation of new online communities and enhancing existing relationships with family and friends. Taken together, online social networking appears to be associated with several factors tied to positive well-being, related to either mental health or social connections among older adults.

Implications for Older Adults’ Mental Health

In line with previous research, the studies included in this scoping review generally found a positive association between online social networking and subjective well-being (Cotten, Ford, Ford, & Hale, Reference Cotten, Ford, Ford and Hale2014; Erickson & Johnson, Reference Erickson and Johnson2011; Forsman & Nordmyr, Reference Forsman and Nordmyr2017; Ihm & Hsieh, Reference Ihm and Hsieh2015; Khalaila & Vitman-Schorr, Reference Khalaila and Vitman-Schorr2018; Leist, Reference Leist2013; Lifshitz, Nimrod, & Bachner, Reference Lifshitz, Nimrod and Bachner2018; Quintana et al., Reference Quintana, Cervantes, Sáez and Isasi2018). However, well-being itself was often interpreted and measured quite differently across the studies. For example, whereas one study measured well-being as a combination of depressive symptoms, loneliness, and happiness (Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Hu, Lin, Chang and Chang2016), other research included the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Chopik, Reference Chopik2016; Heo, Chun, Lee, Lee, & Kim, Reference Heo, Chun, Lee, Lee and Kim2015), a combination of the UCLA Loneliness Scale, the Life Satisfaction Index, the Self-Efficacy Scale, the Social Support Appraisal Scale, and the Beck Depression Inventory (Erickson & Johnson, Reference Erickson and Johnson2011), or a combination of the Satisfaction with Life Scale, the Enjoyment of Life Scale, and components of the Quality of Life Scale (Quintana et al., Reference Quintana, Cervantes, Sáez and Isasi2018). The lack of a standardized definition of well-being and discrepancies in operationalization may result in measurements of well-being that are neither reliable nor valid (Diener, Scollon, & Lucas, Reference Diener, Scollon and Lucas2003). As a result, each research article’s definition may be inferred through the types of scales used to measure well-being, as opposed to using one formal and consistent definition (Diener, Reference Diener2009). For example, some studies conceptualized well-being as an umbrella term for mental health (Erickson & Johnson, Reference Erickson and Johnson2011), while others analyzed quality of life (Khalaila & Vitman-Schorr, Reference Khalaila and Vitman-Schorr2018), a combination of depressive symptoms and overall satisfaction with life (Lifshitz et al., Reference Lifshitz, Nimrod and Bachner2018), or a combination of satisfaction with life, happiness, and eudaimonia (Quintana et al., Reference Quintana, Cervantes, Sáez and Isasi2018). Nonetheless, despite a lack of consensus regarding the definition of well-being, the research generally demonstrated a positive relationship between online social networking and each study’s respective definition of subjective well-being.

Although we examined depression, loneliness, social isolation, and mental health more broadly, with regard to depression specifically, the research examined here generally found a link between greater online social networking and fewer depressive symptoms (Cotten et al, Reference Cotten, Ford, Ford and Hale2014; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kim and Sharratt2018; Lifshitz et al., Reference Lifshitz, Nimrod and Bachner2018; Minagawa & Saito, Reference Minagawa and Saito2014). In particular, older adults with depression who lived alone tended to benefit the most from using online social networking (Cotten et al., Reference Cotten, Ford, Ford and Hale2014). Common measures of self-reported feelings of depression included loneliness, loss of appetite, feelings of sadness, lack of motivation, and restlessness (Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Hu, Lin, Chang and Chang2016; Chopik, Reference Chopik2016; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kim and Sharratt2018; Teo, Markwardt, & Hinton, Reference Teo, Markwardt and Hinton2019). A large proportion of the research articles included in this scoping review (Challands, Lacherez, P., & Obst, Reference Challands, Lacherez and Obst2017; Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Hu, Lin, Chang and Chang2016; Chopik, Reference Chopik2016; Cotten et al., Reference Cotten, Ford, Ford and Hale2014; Teo et al., Reference Teo, Markwardt and Hinton2019) used the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), a widely used scale that has also been supported by previous research (Carleton et al., Reference Carleton, Thibodeau, Teale, Welch, Abrams and Robinson2013). Although the CES-D was originally designed to diagnose depression in (middle-aged) adult populations (Radloff, Reference Radloff1977), it has also been shown to be an effective measure of depressive symptoms for community-dwelling older adults (Cosco et al., Reference Cosco, Lachance, Blodgett, Stubbs, Co and Veronese2019; Lewinsohn, Seeley, Roberts, & Allen, Reference Lewinsohn, Seeley, Roberts and Allen1997). Additionally, the association between decreased depressive symptoms and greater online social networking may be mediated by reduced loneliness (Chopik, Reference Chopik2016), as online social networking provides a platform for communication with others, bolstering relationships, participating in leisure activities, and increasing levels of confidence (Chen & Schulz, Reference Chen and Schulz2016). More specifically, applications that allow for video chats, such as Skype, which most closely resemble in-person interactions (compared with e-mail and instant messaging), appear to be associated to a greater extent with fewer depressive symptoms (Teo et al., Reference Teo, Markwardt and Hinton2019). Therefore, this research suggests that the aforementioned benefits that online social networking may provide can serve as preventative measures against depression, loneliness, and even suicidal tendencies (Jun & Kim, Reference Jun and Kim2017).

The research examined in this scoping review also generally suggested an association between online social networking and increased levels of self-efficacy and confidence (Blusi et al., Reference Blusi, Asplund and Jong2013; Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Hu, Lin, Chang and Chang2016; Erickson & Johnson, Reference Erickson and Johnson2011; Leist, Reference Leist2013; Xie, Reference Xie2008). This association was found in correlational and qualitative studies (Díaz-Prieto & García-Sánchez, Reference Díaz-Prieto and García-Sánchez2016; Erickson & Johnson, Reference Erickson and Johnson2011; Szabo, Allen, Stephens, & Alpass, Reference Szabo, Allen, Stephens and Alpass2019; Zhang, Reference Zhang2016; Zhou, Reference Zhou2018) as well as two intervention studies (Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Hu, Lin, Chang and Chang2016; Morton et al., Reference Morton, Wilson, Haslam, Birney, Kingston and McCloskey2018). Because of the small proportion of randomized control trials found in this scoping review, the direction of causality cannot be inferred. It is possible that more autonomous older adults are increasingly likely to use online social networking. However, it is equally likely that online networking allows for older adults to become more independent (Erickson & Johnson, Reference Erickson and Johnson2011). Nonetheless, the two intervention studies (Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Hu, Lin, Chang and Chang2016; Morton et al., Reference Morton, Wilson, Haslam, Birney, Kingston and McCloskey2018) did provide some support for the idea that online social networking may increase levels of autonomy. Regardless of the causal direction, however, increased levels of autonomy and self-efficacy in older adults are important to consider, especially given that a strong sense of self is often linked to greater overall mental health (Morton et al., Reference Morton, Wilson, Haslam, Birney, Kingston and McCloskey2018). Indeed, regaining independence and self-efficacy may be especially important for older adults; in the studies examined here, some older adults reported avoiding potential opportunities for social engagement out of a fear of being rejected, as well as a loss of their “youthful identity” (Goll, Charlesworth, Scior, & Stott, Reference Goll, Charlesworth, Scior and Stott2015). Online social networking can sometimes compensate for the absence of activities requiring a certain level of independence and mobility that older adults sometimes no longer possess, or have increased difficulty with, such as driving (Challands et al., Reference Challands, Lacherez and Obst2017; Choi et al., Reference Choi, Kong and Jung2012). As a result, online social networking may help older adults increase their sense of autonomy through various mechanisms, such as learning new skills (Erickson & Johnson, Reference Erickson and Johnson2011), conversing with other older adults with similar experiences to make informed decisions (Blusi et al., Reference Blusi, Asplund and Jong2013), increasing health literacy (Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Hu, Lin, Chang and Chang2016), and even managing challenges associated with adjusting to a new country (Zhang, Reference Zhang2016). Fortunately, some features of online social networking applications can facilitate ease of use, especially for older adults, including voice control, the ability to provide and ask for logistical support through instant messaging, and language translation (Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Hu, Lin, Chang and Chang2016; Xie, Reference Xie2008). Through the ability to acquire new skills, older adults have reported feeling a greater sense of control over their lives, as well as increased confidence, and self-esteem (Zhang, Reference Zhang2016). As such, older adults felt as though they were able to re-establish a presence within their communities through having access to knowledge of current events, the ability to understand Internet references, and different options for leisure activities (e.g., chatting with distant friends, singing songs, and playing computer games; Blusi et al., Reference Blusi, Asplund and Jong2013).

Implications for Older Adults’ Social Connectedness

In addition to mental health, social connectedness was an overarching theme resulting from this scoping review, which could be further divided into two sub-topics: enhancing existing relationships and the creation of new online communities. Indeed, many of the studies examined here found that online social networking can serve as a tool to enhance existing relationships (Chen & Schulz, Reference Chen and Schulz2016; Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Hu, Lin, Chang and Chang2016; Delello & McWhorter, Reference Delello and McWhorter2017; Khosravi, Rezvani, & Wiewiora, Reference Khosravi, Rezvani and Wiewiora2016; Nimrod, Reference Nimrod2010; Pfeil, Zaphiris, & Wilson, Reference Pfeil, Zaphiris and Wilson2009; ten Bruggencate et al., Reference ten Bruggencate, Luijkx and Sturm2018; Xie, Reference Xie2008). Given that a common function of online social networking is to consistently keep in contact with family members from younger generations (e.g., nieces, nephews, and grandchildren) through applications such as e-mail and video-conferencing, such interactions often strengthen those relationships (Berg et al., Reference Berg, Winterton, Petersen and Warburton2017; Delello & McWhorter, Reference Delello and McWhorter2017; Machado, Jantsch, de Lima, & Behar, Reference Machado, Jantsch, de Lima and Behar2014). This can be especially helpful for older adults who are geographically distant from their family members or for those who struggle with mobility (Chen & Schulz, Reference Chen and Schulz2016; Delello & McWhorter, Reference Delello and McWhorter2017; Heo et al., Reference Heo, Chun, Lee, Lee and Kim2015; Khosravi et al., Reference Khosravi, Rezvani and Wiewiora2016; ten Bruggencate et al., Reference ten Bruggencate, Luijkx and Sturm2018). In this regard, especially given the likelihood of driving cessation among many older adults, online social networking has been shown to be a protective factor against social isolation and loneliness (Challands et al., Reference Challands, Lacherez and Obst2017). As such, older adults may be motivated to use social networking technology (Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Hu, Lin, Chang and Chang2016), with the added benefit of gaining social acceptance amongst their younger family members (Blusi et al., Reference Blusi, Asplund and Jong2013). Older adults have also used online social networking to reconnect with childhood friends (Delello & McWhorter, Reference Delello and McWhorter2017), which may, in some ways, compensate for the shrinking social network that is often associated with aging (Nimrod, Reference Nimrod2010). Likewise, even among older adults living in retirement care, online social networking can be used to engage with other members of their retirement homes and their family (Delello & McWhorter, Reference Delello and McWhorter2017), which also ties back to enhanced subjective well-being, as older adults who feel a stronger sense of group identification with their care communities are also more likely to report increased levels of happiness (Xie, Reference Xie2008; Ysseldyk et al., Reference Ysseldyk, Bond, Tehranzadeh, Wallace, Wu and Fleming2021).

In addition to maintaining existing social contacts, another way in which older adults might compensate for potentially shrinking social networks is through the creation of new online communities. Oftentimes, older adults join or create online communities with other individuals with whom they have common interests, including hobbies, life circumstances, or physical proximity (Khosravi et al., Reference Khosravi, Rezvani and Wiewiora2016; Nimrod, Reference Nimrod2010; ten Bruggencate et al., Reference ten Bruggencate, Luijkx and Sturm2018). For example, support groups are made available through online forums to allow for widow(er)s, caregivers, or those with chronic illness to communicate (Chen & Schulz, Reference Chen and Schulz2016; ten Bruggencate et al., Reference ten Bruggencate, Luijkx and Sturm2018), where members can provide support for one another and share coping strategies that are potentially helpful with their respective circumstances (Xie, Reference Xie2008). This can be especially beneficial, as older adults have reported that seeking help from individuals who can empathize with their current situations is paramount (Pfeil et al., Reference Pfeil, Zaphiris and Wilson2009). For example, elderly women with chronic conditions have had the opportunity to create three-dimensional avatars of themselves in a peer-led forum that allows them to rely on each other for emotional and social support (Khosravi et al., Reference Khosravi, Rezvani and Wiewiora2016). Likewise, older adults can also use online social networking for leisure activities, such as singing karaoke and dancing through videoconferencing (Xie, Reference Xie2008). Other examples include chat rooms where older adults can share advice on how to best use their technological devices (Xie, Reference Xie2008), thus addressing a major mobility barrier (Woodward et al., Reference Woodward, Freddolino, Wishart, Bakk, Kobayashi and Tupper2013). The creation of online communities also has added benefits in rural communities (Berg et al., Reference Berg, Winterton, Petersen and Warburton2017; Blusi et al., Reference Blusi, Asplund and Jong2013). As access to acquaintances, friends, community resources, and even health care services can be limited as a function of geographic location, older adults have reported using videoconferencing to interact with community groups and health care practitioners, often being quite satisfied with this alternative, as it saves travel time and is ultimately more cost efficient (Berg et al., Reference Berg, Winterton, Petersen and Warburton2017).

Implications for Programs and Policy

Taken together, increasing opportunities for older adults to engage in online social networking appears to be a potential method to alleviate loneliness, social isolation, and depression (Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Hu, Lin, Chang and Chang2016; Chow & Yau, Reference Chow and Yau2016; Morton et al., Reference Morton, Wilson, Haslam, Birney, Kingston and McCloskey2018; Neves et al., Reference Neves, Franz, Judges, Beermann and Baecker2017). Generally speaking, intervention programs can ensure that technological devices are accessible to older adults (Blaschke, Freddolino, & Mullen, Reference Blaschke, Freddolino and Mullen2009), empower older adults (Hill, Betts, & Gardner, Reference Hill, Betts and Gardner2015), and provide in-depth training on social networking platforms (Poscia et al., Reference Poscia, Stojanovic, La Milia, Duplaga, Grysztar and Moscato2018). However, a variety of social determinants of health, such as socio-economic status, ethnicity, and living in rural or remote areas, need to be taken into consideration to ensure that equity is achieved so that all older adults are equally able to reap the benefits of online social networking (Ihm & Hsieh, Reference Ihm and Hsieh2015; Khalaila & Vitman-Schorr, Reference Khalaila and Vitman-Schorr2018).

Rural or remote areas may experience issues associated with Internet access, which may further disadvantage populations that already experience a dearth of health care services (Hodge, Carson, Carson, Newman, & Garrett, Reference Hodge, Carson, Carson, Newman and Garrett2017). As previously mentioned, online social networking can be especially beneficial for older adults who are geographically distant from their family and friends, and the implementation of greater opportunities for online social networking can be beneficial, as seen through some intervention studies (Blusi et al., Reference Blusi, Asplund and Jong2013; Dow et al., Reference Dow, Moore, Scott, Ratnayeke, Wise and Sims2008). As such, interventions could also consider strategies for improving Internet access and providing opportunities for older adults to connect with one another, especially as older adults from rural areas are often quite motivated to learn how to use communication technology (Baker, Warburton, Hodgin, & Pascal, Reference Baker, Warburton, Hodgin and Pascal2016).

The intersection between socio-economic status and ethnicity is also an important area of consideration for program and policy makers, particularly with regard to service access in under-served populations. This has been reflected in previous research, in which older adults who did not use the Internet at all (or those who discontinued their Internet usage) were more likely to be from racial minorities and lower socio-economic groups (Choi & Dinitto, Reference Choi and Dinitto2013; Yoon, Jang, Vaughan, & Garcia, Reference Yoon, Jang, Vaughan and Garcia2018). Higher income is often associated with a greater level of access to technology and a greater ability to navigate the technology in question (Hargittai, Piper, & Morris, Reference Hargittai, Piper and Morris2018). Furthermore, this association has been shown to be greater among older, compared with younger, adults (Ihm & Hsieh, Reference Ihm and Hsieh2015). This, in turn, can have a negative impact on health and well-being, as older adults with low socio-economic status may have decreased opportunities to benefit from the advantages that online social networking has to offer (Ihm & Hsieh, Reference Ihm and Hsieh2015), such as the ability to communicate with health care providers from a distance (Choi & Dinitto, Reference Choi and Dinitto2013). Another important issue may be the lack of willingness by some minority group members to participate in online social networking, as experiencing discrimination may influence their motivation to connect with others online (Choi & Dinitto, Reference Choi and Dinitto2013). Some potential ways that policy makers might lessen this “digital divide” include providing free technology and training sessions in public libraries and creating opportunities for people to donate technological devices to individuals from low-income households (Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Jang, Vaughan and Garcia2018).

Limitations

Despite the contributions made by this scoping review toward understanding potential links between online social networking and older adults’ mental health, several limitations should be noted. First, most studies relied on self-reported measures of depressive symptoms, opening up the possibility of eliciting socially desirable responses (Erickson & Johnson, Reference Erickson and Johnson2011) or experiencing difficulty reporting one’s mood in retrospect (Cotten et al., Reference Cotten, Ford, Ford and Hale2014). Nonetheless, some research has demonstrated that self-report measures of health may be as reliable and accurate as clinical scales (Hudson, Anusic, Lucas, & Donnellan, Reference Hudson, Anusic, Lucas and Donnellan2020). Likewise, because of stigma and/or a lack of access to diagnostic and treatment services, some individuals may be prevented from receiving clinical diagnoses of depression; therefore, participant recruitment or analyses based on a formal diagnosis may not be as all-encompassing as hoped (Araya, Zitko, Markkula, Rai, & Jones, Reference Araya, Zitko, Markkula, Rai and Jones2018; Clement et al., Reference Clement, Schauman, Graham, Maggioni, Evans-Lacko and Bezborodovs2014). Although a formal diagnosis was not part of the inclusion criteria for participants in the studies included in this scoping review, administering the same self-report scales to all participants to measure depressive symptoms, such as the CES-D (Challands et al., Reference Challands, Lacherez and Obst2017; Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Hu, Lin, Chang and Chang2016; Chopik, Reference Chopik2016; Cotten et al., Reference Cotten, Ford, Ford and Hale2014; Teo et al., Reference Teo, Markwardt and Hinton2019) may have helped to decrease potential discrepancies among the studies’ findings.

Second, articles from only three databases were examined: PubMed, PsycINFO, and Scopus. Although these databases were chosen a priori as adequate based on the topic of interest, there remains the possibility that our scoping review did not capture all relevant articles. Nonetheless, we consulted an experienced health and bioscience librarian to ensure the comprehensiveness of our search strings, and to ensure that the databases selected represented the most suitable options that would yield the highest number of relevant articles.

Finally, most of the studies included in this scoping review were correlational, and so suggestions of causal relationships should be interpreted cautiously. Future research may consider adopting more randomized controlled trial methodologies and/or longitudinal designs in order to better understand potential causal mechanisms, which would be especially relevant for program and policy implications.

Conclusions

As the older adult population is expected to increase dramatically in the coming years, mental health issues involving loneliness, social isolation, and depression are a growing concern. As “treatment” options for loneliness and social isolation—and the associated mental health impacts—are often difficult to implement, creative solutions that cater to older adults’ unique circumstances (e.g., mobility challenges, decreased social contacts), should be taken into consideration. This scoping review provided greater insight into the current research on the association between online social networking and mental health among older adults. The findings suggest that online social networking may indeed have a positive impact on mental health (including depressive symptoms), while increasing feelings of self-efficacy and independence. As such, interventions designed to provide education and opportunities, such as tutorials on online social networking and opportunities for older adults to use communication technologies, could be potential ways to increase social engagement and decrease loneliness. Nonetheless, various other social factors (e.g., related to other social determinants of health) must also be considered to ensure equitable opportunities for bridging the so-called digital divide that older adults often face, in order for more of them to benefit from this potential online “social cure” (Jetten et al., Reference Jetten, Haslam and Haslam2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Julie-Anne Lemay and Heather MacDonald for their assistance with article selection, and Catherine Haslam, Madeline Lamanna, and Thomas Morton for their feedback on the manuscript. This research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.