INTRODUCTION

The xanthophyll lutein (L) and its isomer zeaxanthin (Z) are among over 600 organic pigments within the carotenoid family (Britton, Liaaen-Jensen, & Pfander, Reference Britton, Liaaen-Jensen and Pfander2004; Khachik, Beecher, Goli, & Lusby, Reference Khachik, Beecher, Goli and Lusby1991). L and Z are not produced endogenously and thus must be consumed through green vegetables, colored fruits, and other aspects of diet (Hammond et al., Reference Hammond, Johnson, Russell, Krinsky, Yeum, Edwards and Snodderly1997; Malinow, Feeney-Burns, Peterson, Klein, & Neuringer, Reference Malinow, Feeney-Burns, Peterson, Klein and Neuringer1980). They traverse the blood-retina barrier to accumulate in several regions of the eye (Bernstein et al., Reference Bernstein, Khachik, Carvalho, Muir, Zhao and Katz2001) but are taken up most selectively in the central region of the retina, referred to as the macula (Bone, Landrum, & Tarsis, Reference Bone, Landrum and Tarsis1985). The importance of L and Z to eye health is well-established, particularly in protecting against age-related macular degeneration (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Dou, Wu, Huang, Huang, Xu and Lin2012; SanGiovanni & Neuringer, Reference SanGiovanni and Neuringer2012).

L and Z also accumulate preferentially in human brain tissue (Craft, Haitema, Garnett, Fitch, & Dorey, Reference Craft, Haitema, Garnett, Fitch and Dorey2004; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Vishwanathan, Johnson, Hausman, Davey, Scott and Poon2013). Together with other xanthophylls (e.g., ß-cryptoxanthin), L and Z account for two-thirds or more of total brain carotenoid concentrations (Craft et al., Reference Craft, Haitema, Garnett, Fitch and Dorey2004).

Most studies determine L and Z levels by measuring blood serum concentrations or by evaluating the optical density of the macular pigment layer (MPOD; Hammond, Wooten, & Smollon, Reference Hammond, Wooten and Smollon2005). Serum levels tend to be influenced by recent food consumption while MPOD reflects longer-term dietary habits (Hammond et al., Reference Hammond, Johnson, Russell, Krinsky, Yeum, Edwards and Snodderly1997). MPOD correlates with postmortem brain tissue concentrations in primates and humans and is considered the most reliable proxy for neural levels (Hammond et al., Reference Hammond, Wooten and Smollon2005; Vishwanathan, Neuringer, Snodderly, Schalch, & Johnson, Reference Vishwanathan, Neuringer, Snodderly, Schalch and Johnson2013; Vishwanathan, Schalch, & Johnson, Reference Vishwanathan, Schalch and Johnson2016).

Human and animal studies have shown a relationship between L and Z dietary intake and MPOD. Rhesus monkeys raised on xanthophyll-free diets exhibit absent or severely depleted macular pigment (Malinow et al., Reference Malinow, Feeney-Burns, Peterson, Klein and Neuringer1980). In older women (N=1698), self-reported dietary intake of L and Z positively correlated with MPOD, even after adjusting for medical and lifestyle factors (Mares et al., Reference Mares, LaRowe, Snodderly, Moeller, Gruber, Klein and Chappell2006). Adults who augmented their diets with 60 grams of spinach daily for 15 weeks showed a 19% increase in MPOD on average (Hammond et al., Reference Hammond, Johnson, Russell, Krinsky, Yeum, Edwards and Snodderly1997). L and Z supplements also significantly increase MPOD in both young and older adults (e.g., Landrum et al., Reference Landrum, Bone, Joa, Kilburn, Moore and Sprague1997; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Makridaki, van der Veen, Carden, Parry and Berendschot2013; Stringham & Hammond, Reference Stringham and Hammond2008; Weigert et al., Reference Weigert, Kaya, Pemp, Sacu, Lasta, Werkmeister and Schmetterer2011). For example, Stringham and Hammond (Reference Stringham and Hammond2008) found 6 months of L and Z supplementation (12 mg/daily) to significantly increase MPOD in healthy adults (Cohen’s d=0.97) and improve visual performance. Several other studies have similarly reported improvements in visual function resulting from supplementation (e.g., Kvansakul et al., Reference Kvansakul, Rodriguez-Carmona, Edgar, Barker, Koëpcke, Schalch and Barbur2006; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Lin, Zou, Xu, Li and Xu2009; Yagi et al., Reference Yagi, Fujimoto, Michihiro, Goh, Tsi and Nagai2009), suggesting functional benefits of enhancing MPOD.

An emerging literature also suggests a relation of L and Z dietary intake to cognition in older adults (for reviews, see: Erdman et al., Reference Erdman, Smith, Kuchan, Mohn, Johnson, Rubakhin and Neuringer2015; Johnson, Reference Johnson2012, Reference Johnson2014; Maci, Fonseca, & Zhu, Reference Maci, Fonseca and Zhu2016). For example, a carotenoid-rich dietary pattern in late middle age was associated with better episodic memory, verbal fluency, working memory, and executive functioning 13 years into the future (Kesse-Guyot et al., Reference Kesse-Guyot, Andreeva, Ducros, Jeandel, Julia, Hercberg and Galan2014). Similarly, greater intake of vegetables containing L and Z has been longitudinally associated with slower rates of cognitive decline in older adults (Kang, Ascherio, Grodstein, Reference Kang, Ascherio and Grodstein2005; Lee, Kim, & Back, Reference Lee, Kim and Back2009; Morris, Evans, Tangney, Bienias, & Wilson, Reference Morris, Evans, Tangney, Bienias and Wilson2006). MPOD and serum L and/or Z concentrations have been found to positively correlate with a range of cognitive functions in older adults (Akbaraly, Faure, Gourlet, Favier, & Berr, Reference Akbaraly, Faure, Gourlet, Favier and Berr2007; Feeney et al., Reference Feeney, Finucane, Savva, Cronin, Beatty, Nolan and Kenny2013; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Vishwanathan, Johnson, Hausman, Davey, Scott and Poon2013; Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Coen, Akuffo, Beatty, Dennison, Moran and Nolan2015; Renzi, Dengler, Puente, Miller, & Hammond, Reference Renzi, Dengler, Puente, Miller and Hammond2014; Renzi, Iannacocone, Johnson, & Kritchevsky, Reference Renzi, Iannaccone, Johnson and Kritchevsky2008; Vishwanathan et al., Reference Vishwanathan, Iannaccone, Scott, Kritchevsky, Jennings, Carboni and Johnson2014). Greater serum L is associated with reduced risk for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease mortality (Feart et al., Reference Feart, Letenneur, Helmer, Samieri, Schalch, Etheve and Barberger-Gateau2015; Min & Min, Reference Min and Min2014). In addition, Alzheimer’s disease patients have lower MPOD and serum L and Z relative to age-matched controls (Nolan et al., Reference Nolan, Loskutova, Howard, Moran, Mulcahy, Stack and Thurnham2014).

Several reviews have called for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to determine whether low carotenoid levels contribute to cognitive loss or perhaps represent a consequence, either through neuropathological processes or poor nutritional decisions (Erdman et al., Reference Erdman, Smith, Kuchan, Mohn, Johnson, Rubakhin and Neuringer2015; Johnson, Reference Johnson2012, Reference Johnson2014). To the authors’ knowledge, only one such RCT exists (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, McDonald, Caldarella, Chung, Troen and Snodderly2008) in a sample of older women randomly assigned to receive 4 months of daily DHA (a polyunsaturated fatty acid; n=14), L (n=11), combined supplementation (n=14), or placebo (n=14). The group receiving L showed significant gains in verbal fluency relative to placebo at 4 months (d=0.61). The combined (DHA + L) group evidenced improvements in verbal fluency (d=0.90), learning (d=0.70), and memory (d=0.58) at 4 months.

The means by which L and Z influence brain function is an understudied area, but several mechanisms have been proposed (Erdman et al., Reference Erdman, Smith, Kuchan, Mohn, Johnson, Rubakhin and Neuringer2015; Zamroziewicz & Barbey, Reference Zamroziewicz and Barbey2016). L and Z have strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, which may counter the deleterious effects of age-related oxidative stress and neuroinflammation (Bokov, Chaudhuri, & Richardson, Reference Bokov, Chaudhuri and Richardson2004; Butterfield, Bader Lange, & Sultana, Reference Butterfield, Bader Lange and Sultana2010; Heneka et al., Reference Heneka, Carson, El Khoury, Landreth, Brosseron, Feinstein and Kummer2015; Rosano, Marsland, & Gianaros, Reference Rosano, Marsland and Gianaros2012). L and Z may also benefit neurocognitive function through their positive effects on cell membrane fluidity, permeability, stability, thickness, and ion exchange (Erdman et al., Reference Erdman, Smith, Kuchan, Mohn, Johnson, Rubakhin and Neuringer2015; Krinsky, Mayne, & Sies, Reference Krinsky, Mayne and Sies2004; Widomska & Subczynski, Reference Widomska and Subczynski2014). Relatedly, carotenoids such as L and Z may improve cellular communication by altering gene expression (e.g., connexin 43; Bertram, Reference Bertram1999) and enhancing inter-neuronal signaling at gap junctions (Stahl & Sies, Reference Stahl and Sies2001).

The present study was a 12-month RCT that sought to expand the research base on neural mechanisms underlying the relation of L and Z to cognition in community-dwelling older adults using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Cross-sectional results from the study sample at baseline (Lindbergh et al., Reference Lindbergh, Mewborn, Hammond, Renzi-Hammond, Curran-Celentano and Miller2016) revealed a negative relationship of pre-intervention L and Z levels (measured via serum and MPOD) to blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal in several brain regions during an fMRI-adapted verbal learning task. Lindbergh et al. (Reference Lindbergh, Mewborn, Hammond, Renzi-Hammond, Curran-Celentano and Miller2016) interpreted the observed results to reflect a potential role of L and Z in promoting neural efficiency (the neural efficiency hypothesis; Renzi & Hammond, Reference Renzi and Hammond2010) during cognitive performance, particularly in brain regions with established risk for age-related degeneration. This interpretation was based in part on the revised Scaffolding Theory of Aging and Cognition (STAC-r), which emphasizes “life-course” variables, including nutrition, in shaping the structure and function of the aging brain (Reuter-Lorenz & Park, Reference Reuter-Lorenz and Park2014). More specifically, Lindbergh et al. (Reference Lindbergh, Mewborn, Hammond, Renzi-Hammond, Curran-Celentano and Miller2016) speculated that L and Z buffer age-related neuropathological processes and thus reduce the associated need for compensatory neural recruitment in response to cognitive challenge (Park & Reuter-Lorenz, Reference Park and Reuter-Lorenz2009; Reuter-Lorenz & Park, Reference Reuter-Lorenz and Park2014). Although L and Z are not specifically mentioned in the STAC-r, this would be consistent with the more general construct of “neural resource enrichment” discussed by Reuter-Lorenz and Park (Reference Reuter-Lorenz and Park2014, p. 361), which encompasses various nutritional and lifestyle factors. As with most research on this topic, however, Lindbergh et al.’s (Reference Lindbergh, Mewborn, Hammond, Renzi-Hammond, Curran-Celentano and Miller2016) conclusions were limited by the cross-sectional nature of the analyses.

The RCT design of the current investigation addressed limitations of cross-sectional analyses and permitted evaluation of L and Z’s effects on the aging brain relative to placebo. An fMRI-adapted verbal learning and memory paradigm was employed in which participants were asked to learn and recall word pairs. Within the framework of the STAC-r (Reuter-Lorenz & Park, Reference Reuter-Lorenz and Park2014), L and Z were expected to function as “neural resource enrichment,” ultimately countering the effects of neurophysiological decline and reducing the need for compensatory scaffolding. Accordingly, it was expected that older adults receiving L and Z supplementation would exhibit increased neurobiological efficiency as evidenced by reduced neural activity (i.e., BOLD signal) required to meet task demands relative to controls. Based on regions-of-interest (ROIs) identified through prior literature (e.g., Bookheimer et al., Reference Bookheimer, Strojwas, Cohen, Saunders, Pericak-Vance, Mazziotta and Small2000, Reference Bookheimer, Renner, Ekstrom, Li, Henning, Brown and Small2013; Cabeza & Nyberg, Reference Cabeza and Nyberg2000; Clément & Belleville, Reference Clément and Belleville2009), the anticipated effects during verbal learning were expected to predominate in medial temporal lobe, supramarginal and angular gyri, precuneus, dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, anterior and posterior cingulate gyrus, Broca’s area, cerebellum, and premotor areas. A similar network of brain regions was expected to show effects during verbal recall with the addition of anterior prefrontal cortex and medial parieto-occipital regions (retrosplenial cortex and cuneus) given somewhat different processes involved in retrieval versus encoding (Cabeza & Nyberg, Reference Cabeza and Nyberg2000).

A secondary aim was to replicate and extend previous findings showing a positive relation of L and Z to cognition in older adults. Consistent with the bulk of the available literature, it was hypothesized that L and Z supplementation would benefit performance on the fMRI-adapted verbal learning task in terms of number of words successfully recalled relative to placebo.

METHOD

Participants

75 community-dwelling older adults (64–86 years of age) were recruited via newspaper advertisements, flyers, and electronic media (e.g., listservs) as part of a larger intervention study. Exclusionary criteria included left-handedness, traumatic brain injury, macular degeneration, gastric conditions that may interfere with supplement absorption, corrected visual acuity worse than 20:40, MRI incompatibility, Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) total score > 19, or neurological disorder. Of the 75 participants eligible for inclusion following an initial phone screening, more thorough medical history review revealed that seven participants were incompatible with the MRI environment. Three more participants became uncomfortable within the scanner and requested to stop due to claustrophobia (n=2) or sensitivity to noise (n=1). An additional participant was unable to remain awake. Sixteen volunteers elected not to complete the study for various reasons, and behavioral data for one individual were lost due to technical malfunction. Three volunteers were obviously unable to grasp the fMRI task, yielding a final sample size of 44 (experimental n=30; control n=14) for analyses.

Procedures

A single-site, double-blind, RCT design was employed. Eligible participants were assigned using a 2:1 experimental to control group ratio to receive either a supplement containing L (10 mg) and Z (2 mg) or a physiologically inert placebo of identical appearance provided by DSM Nutritional Products (Basel, Switzerland). Randomization was performed by generating a set of numerical codes corresponding to either the active supplement or the placebo. These codes were placed in an opaque envelope and drawn for each participant by the study coordinator, who did not have any data collection responsibilities. Participants were instructed to consume one pill per day with a meal for 1 year. As noted previously, baseline (cross-sectional) fMRI findings from this study evaluating the relation of naturally circulating L and Z levels to neural activity, prior to supplementation, have been published elsewhere (Lindbergh et al., Reference Lindbergh, Mewborn, Hammond, Renzi-Hammond, Curran-Celentano and Miller2016). Lindbergh et al. (Reference Lindbergh, Mewborn, Hammond, Renzi-Hammond, Curran-Celentano and Miller2016) used a largely overlapping, although not completely identical, subset of the sample in final analyses due to somewhat different variables of interest (see Lindbergh et al., Reference Lindbergh, Mewborn, Hammond, Renzi-Hammond, Curran-Celentano and Miller2016).

The RCT entailed eight laboratory visits in addition to a physical examination with a health professional to verify appropriate health for the study (see Table 1). Eligible participants completed three baseline sessions occurring within a 2-week period, including vision testing, cognitive testing, measurement of L and Z concentrations in macular pigment, and acquisition of neuroimaging data. Bi-monthly contact assessed compliance, adverse events, and any health changes that could render participants ineligible for participation. Pill counts were conducted at 4 month, 8 month, and 12 month visits and participants were only provided with enough pills to last until their next visit. The 12 month (post-intervention) visit was completed across three sessions that mirrored the baseline visit.

Table 1. Study timeline

Note. Cog. testing=cognitive testing, which included the Geriatric Depression Scale and Wechsler Test of Adult Reading at Visit 1; Mos=months. Baseline visits 1, 2, and 3 occurred within a 2-week window, as did post-intervention visits 6, 7, and 8. The post-intervention visits occurred at 12 months. Vision testing included measurement of macular pigment optical density (MPOD).

Participants were compensated with $300 distributed across four time points (i.e., baseline, 4 months, 8 months, and 12 months). If participants required transportation to experimental sessions, $20 was provided to the collateral driver at each time point.

The study was approved by the University of Georgia Institutional Review Board and the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki were closely followed by all study personnel.

Measures

Wechsler Test of Adult Reading

Premorbid intellectual functioning was estimated using the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR), which involves reading a list of 50 words with atypical grapheme to phoneme relationships (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler2001). Full-scale intelligence quotient estimates were calculated using an algorithmic combination of WTAR performance (i.e., number of words correctly pronounced) and demographic (i.e., age, education, race, sex, and geographic region) variables (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler2001).

GDS

The GDS was used to screen for significant depressive symptomatology (Yesavage et al., Reference Yesavage, Brink, Rose, Lum, Huang, Adey and Leirer1983). The GDS is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 30 items with yes/no response options, yielding a total score ranging from 0 to 30 (0–9=normal; 10–19=mild; 20–30=severe).

MPOD

L and Z accumulate preferentially in the central area of the retina, referred to as the macula (Bone et al., Reference Bone, Landrum and Tarsis1985). Pigment within the human macula consists of L and Z embedded in retinal tissue (Bone et al., Reference Bone, Landrum and Tarsis1985). The density of the macular pigment layer (MPOD) is frequently used to index L and Z levels within the central nervous system (e.g., Vishwanathan et al., Reference Vishwanathan, Schalch and Johnson2016) and can be measured noninvasively using customized heterochromatic flicker photometry (cHFP), a widely validated technique (Stringham et al, Reference Stringham, Hammond, Nolan, Wooten, Mammen, Smollon and Snodderly2008). The reader is referred to our published baseline findings for a detailed description of the cHFP procedure (Lindbergh et al., Reference Lindbergh, Mewborn, Hammond, Renzi-Hammond, Curran-Celentano and Miller2016), although it is important to note that Lindbergh et al. (Reference Lindbergh, Mewborn, Hammond, Renzi-Hammond, Curran-Celentano and Miller2016) used MPOD as a predictor (i.e., independent variable) in the fMRI analyses. By contrast, in the present analyses, MPOD data are presented only as a validity check on our intervention to verify that our supplementation effectively increased L and Z status over the course of the study. Briefly, cHFP involved presenting a 1-deg visual stimulus consisting of two narrow-band light sources, peaking at 460 nm and 570 nm, using a macular densitometer (Macular Metrics; Rehoboth, MA). After determining customized flicker sensitivities, the lower (i.e., 460 nm) waveband radiance was manipulated relative to the 570 nm waveband to measure the point at which flickering could no longer be perceived. This sequence was conducted again with a 2˚ target and fixation point at 7˚ nasally to provide a parafoveal reference measurement where MPOD approaches zero. The two loci were then contrasted for an MPOD measurement at 30 minutes of retinal eccentricity.

Neuroimaging

FMRI task

Participants engaged in a verbal learning task, conceptually derived from the Wechsler memory scale paired associates learning test (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler2009), similar to previously published fMRI paradigms (e.g., Bookheimer et al., Reference Bookheimer, Strojwas, Cohen, Saunders, Pericak-Vance, Mazziotta and Small2000, Reference Bookheimer, Renner, Ekstrom, Li, Henning, Brown and Small2013; Braskie, Small, & Bookheimer, Reference Braskie, Small and Bookheimer2009), and described in detail elsewhere (Lindbergh et al., Reference Lindbergh, Mewborn, Hammond, Renzi-Hammond, Curran-Celentano and Miller2016). The basic goal of the task was to learn unrelated word pairs (e.g., “UP” and “FOOT”). E-Prime software (version 1.2, Psychology Software Tools, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA) was used to program and present the task in conjunction with MRI compatible goggles (Resonance Technology Inc., Northridge, CA). Participants provided responses using right and left index finger buttons on Cedrus Lumina LU400 MRI compatible response pads (Cedrus, San Pedro, CA).

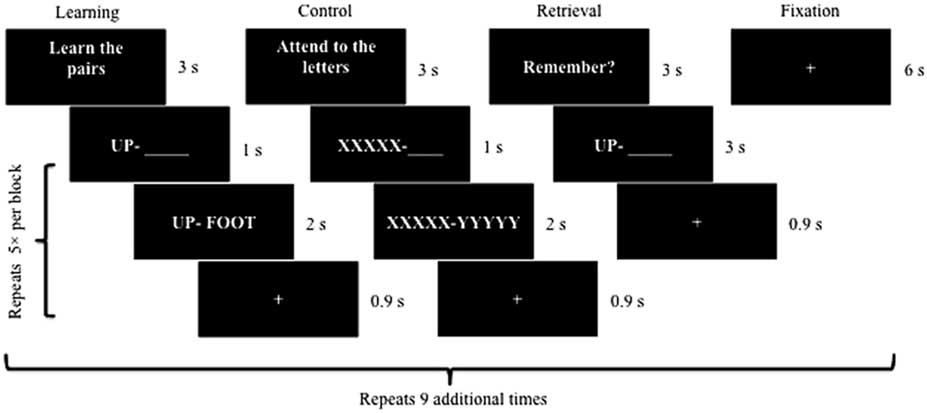

The task entailed 10 each of learning blocks, control blocks, retrieval blocks, and baseline fixation blocks (see Figure 1). During learning blocks, the first word of each pair was displayed in isolation on the left side of the screen (1 s) followed by presentation of the second word on the right side, such that both words could be viewed side by side (2 s). There were 10 word pairs total with 5 pairs presented during each encoding block. During retrieval trials, participants were presented with the first word in each pair (3 s) and asked to mentally recall the second word to prevent head motion, consistent with procedures used in analogous fMRI-adapted verbal learning tasks (e.g., Bookheimer et al., Reference Bookheimer, Strojwas, Cohen, Saunders, Pericak-Vance, Mazziotta and Small2000, Reference Bookheimer, Renner, Ekstrom, Li, Henning, Brown and Small2013). Participants were instructed to make a right index finger press if they successfully retrieved the second word or a left index finger press to indicate unsuccessful retrieval. A control task interspersed learning and retrieval blocks, which mimicked the learning block except that “XXXXX” and “YYYYY” were presented in place of word pairs. Immediately post scan, participants engaged in cued recall of the “second word” in each pair (maximum score: 10) to help assess task engagement within the scanner.

Fig. 1 Visual schematic of the fMRI-adapted verbal learning task. Each block (i.e., learning, control, retrieval, and fixation) was presented 10 times. Five different word pairs were included within every learning block followed by five XXXXX – YYYYY pairings within every control block. Similarly, participants attempted to recall the second word of five different word pairs during each retrieval block.

MRI acquisition

Scans were acquired on a General Electric (GE; Waukesha, WI) 3 T Signa HDx MRI system. A high-resolution three-dimensional T1-weighted fast spoiled gradient recall echo sequence was used to collect structural scans (repetition time [TR]=7.5 ms; echo time [TE]=< 5 ms; field of view [FOV]=256 × 256 mm matrix; flip angle=20°; slice thickness=1.2 mm; 154 axial slices) with a total acquisition time of 6 min and 20 s. This protocol collected 176 images, providing coverage from the brainstem to the top of the head.

Functional scans were aligned to each participant’s anterior commissure-posterior commissure line and acquired axially with a T2*-weighted single shot echo planar imaging (EPI) sequence (TR=1500 ms; TE=25 ms; 90° RF pulse; acquisition matrix=64 × 64; FOV=220 × 220 mm; in-plane resolution=220/64 mm; slice thickness=4 mm; 30 interleaved axial slices). Four dummy scans were collected at the outset of the run and discarded. The EPI sequence consisted of 486 volumes covering the cortical surface and a portion of the cerebellum with a total acquisition time of 12 min and 24 s. Magnitude and phase images were also acquired (1 min and 40 s each) for fieldmap-based unwarping (TR=700 ms; TE=5.0/7.2 ms; FOV=220 × 220 mm matrix; flip angle=30°; slice thickness=2 mm; 60 interleaved slices).

Data analyses

Functional neuroimaging data were processed and analyzed using Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM12, Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK). The dcm2nii conversion tool was used to convert data from GE DICOM to NIFTI format (Rorden, Reference Rorden2007). The preprocessing pipeline included slice time correction to address non-sequential, interleaved acquisition and realignment of functional images to the first volume of the functional run to adjust for head movement. To account for phase and magnitude variations across the scan, fieldmaps were used to realign and unwarp images. Co-registration of anatomical scans to the first image of the functional scan was followed by registration of anatomical and functional images to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) template. The anatomical image was segmented into bone, air, cerebrospinal fluid, non-brain soft tissue, and brain tissue (i.e., white and gray matter). Deformation fields were applied to permit spatial normalization to MNI space and images were smoothed with a 6.75 mm full-width half-maximum Gaussian filter.

Following the above pre-processing steps, the General Linear Model (SPM12) was applied to create BOLD signal activation maps of encoding minus control trials and recall minus control trials. A p < .05, family-wise-error (FWE) corrected statistical threshold with a minimum of eight contiguous voxels was selected for analyses given optimal balance between Type I and II errors (Lazar, Reference Lazar2008).

ROIs were defined using the WFU PickAtlas version 3.0.5 (Maldjian, Laurienti, Burdette, & Kraft, Reference Maldjian, Laurienti, Burdette and Kraft2003; Maldjian, Laurienti, & Burdette, Reference Maldjian, Laurienti and Burdette2004). Consistent with prior studies (e.g., Bookheimer et al., Reference Bookheimer, Strojwas, Cohen, Saunders, Pericak-Vance, Mazziotta and Small2000, Reference Bookheimer, Renner, Ekstrom, Li, Henning, Brown and Small2013; Cabeza & Nyberg, Reference Cabeza and Nyberg2000; Clément & Belleville, Reference Clément and Belleville2009), ROIs during learning trials included medial temporal lobe, supramarginal and angular gyri, precuneus, dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, anterior and posterior cingulate gyrus, Broca’s area, cerebellum, and premotor areas. Recall trials consisted of these ROIs as well as anterior prefrontal cortex, retrosplenial cortex, and cuneus (Cabeza & Nyberg, Reference Cabeza and Nyberg2000).

To assess the anticipated effect of L and Z supplementation on brain activity, a 2×2 flexible factorial model was used in second level ROI analyses with group (placebo vs. supplement) as a between-subjects factor and time (baseline vs. post-intervention) as a within-subjects factor. Significant group × time interactions within the aforementioned ROIs would be consistent with the expectation that L and Z intake alters neural activation relative to placebo. Repeated measure within-group comparisons were used to more specifically characterize significant interactions within ROIs in terms of directionality (i.e., increases vs. decreases in BOLD signal). All second level ROI analyses were conducted separately for encoding and retrieval given non-identical neural underpinnings of these two processes (Cabeza & Nyberg, Reference Cabeza and Nyberg2000).

Behavioral performance was also assessed to help verify task engagement and evaluate for intervention effects. Within-scanner self-reported recall of the second word in each pair on the last two recall blocks (maximum score=10), when learning is expected to be maximal, was calculated. These values were then correlated with actual cued recall assessed immediately post scan to evaluate performance validity. Behavioral performance was also subject to a 2×2 mixed design analysis of variance (ANOVA) to investigate the expected group (placebo vs. supplement) by time (baseline vs. post-intervention) interaction.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

Sample characteristics and (self-reported) dietary intake of vegetables, fruit, fish, and meat at baseline for both the placebo and supplement groups are presented in Table 2. Although there were no statistically significant differences between groups, the supplement group was somewhat older than the placebo group (small-to-medium effect size).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics

Note. GDS=Geriatric Depression Scale; M=mean; SD=standard deviation; WTAR=full-scale intelligence quotient predicted from the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading. Dietary intake represents self-reported servings of vegetables, fruits, fish, and meats per week.

Analysis of pill count data and results from bi-monthly compliance phone calls revealed no significant differences between groups with respect to adherence (ps all>.05). From the 24 total phone contacts, the average number of self-reported missed pills over the course of the study was only three for both the supplement and control groups. Taken together with the results from MPOD measurements (see below), the pill counts and phone contacts suggest acceptable adherence to the prescribed supplementation regimen.

There were no significant differences between older adults who dropped out of the study (N=16) and those who completed the study (N=44) with respect to age, education level, premorbid intellectual functioning, sex, race, and dietary intake (ps > .05). In addition, MPOD and cognitive performance of individuals who completed the baseline vision (N=11) and fMRI (N=9) sessions but subsequently dropped were comparable to completers (ps > .05).

MPOD

Table 3 presents MPOD values, which were used to verify a biological response to L and Z supplementation. Given that MPOD data were available at both 8 months and 12 months, we employed an average of these two time points to estimate L and Z changes over the course of the intervention. An average was employed to increase the stability of the measurement by doubling the number of observations, particularly given the relatively small number of individuals in the control group (n=14). Importantly, neither the supplement group nor the control group showed a significant change in MPOD between the 8 and 12 month time points. As expected, the supplement group evidenced a significant increase in MPOD across time [t(29)=2.46; p=.016] while the placebo group’s MPOD remained constant [t(13)=.05; p=.961]. The supplement group’s MPOD was significantly greater than the control group’s MPOD following the intervention [t(42)=2.44; p=.019], despite the two groups showing comparable MPOD at baseline (p > .05).

Table 3. Intervention effects on MPOD and cognition

Note. M=mean; MPOD=macular pigment optical density; SD=standard deviation; Word recall=number of words recalled on the final two blocks of the fMRI-adapted verbal learning paradigm (maximum=10); *=average of 8-month and 12-month (post-intervention) time points.

We note that the same pattern of results is obtained if the data are analyzed without averaging across 8 and 12 month time points. That is, the supplement group’s MPOD at 12 months showed a significant increase relative to baseline (p=.03; d=0.84) while the placebo group’s MPOD at 12 months does not significantly differ from baseline.

Zero-order bivariate correlations between MPOD and demographic variables are provided in Table 4. MPOD values at baseline were not significantly related to age, education, depressive symptomatology, or estimated intellectual functioning (ps all > .05).

Table 4. Zero-order bivariate correlations between MPOD and sample characteristics

Note. GDS=Geriatric Depression Scale; MPOD=macular pigment optical density; WTAR=full-scale intelligence quotient predicted from the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading. Values are presented as Pearson’s r (p value).

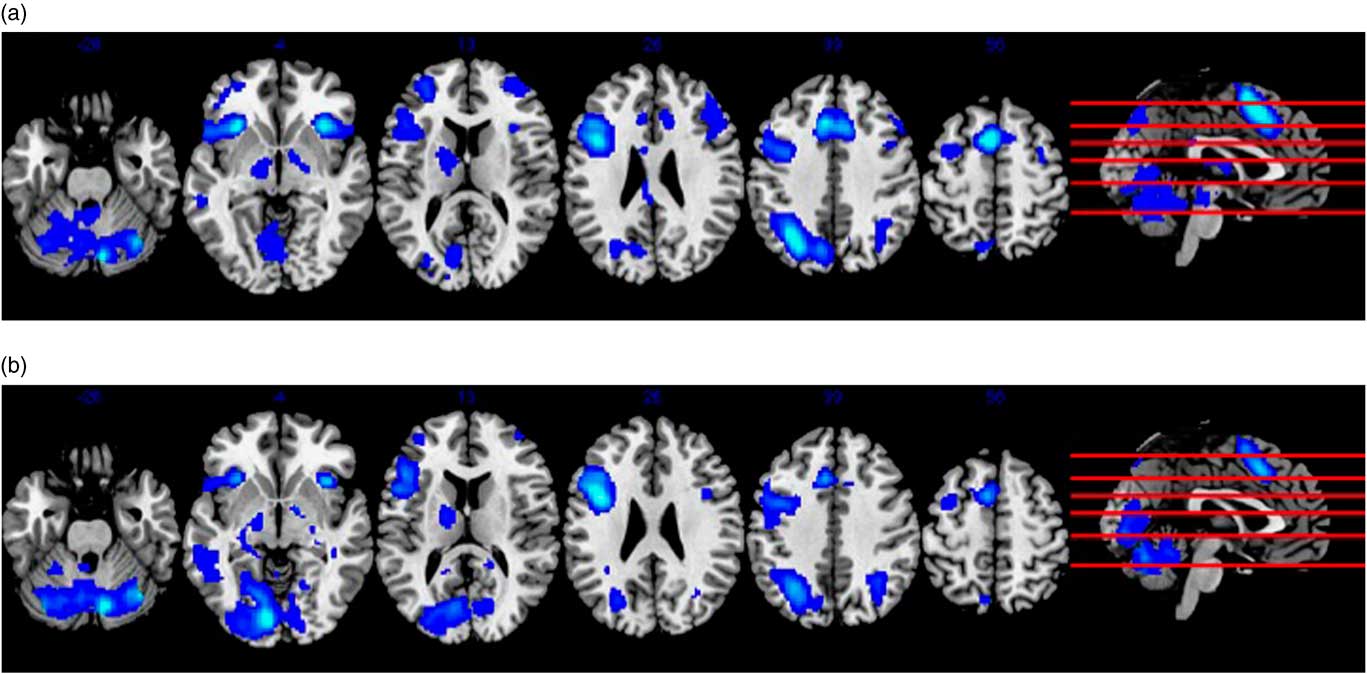

Whole-Brain Analyses

Whole-brain analysis of the encoding minus control contrast in the pooled sample at baseline, independent of supplement status, is shown in Figure 2. Widespread activation was observed in brain regions typically associated with verbal learning in the literature, such as prefrontal (e.g., Broca’s area), medial-temporal (e.g., hippocampus), and cerebellar regions with a general tendency for left-lateralization (p < .05, FWE-corrected, minimum eight contiguous voxels). Whole-brain analysis of the retrieval minus control contrast at baseline also revealed diffuse activation in brain areas commonly associated with verbal retrieval (see Figure 2), including prefrontal, medial-temporal, parieto-occipital, and cerebellar areas (p < .05, FWE-corrected, minimum eight contiguous voxels). Importantly, there were no significant differences in brain activation between supplement and control groups during either learning or retrieval trials at baseline. This finding remained with and without age as a covariate in the between group contrast.

Fig. 2 Panel (a) shows results from whole-brain analysis of the encoding minus control contrast at baseline in the pooled sample, independent of supplement status. Panel (b) similarly depicts whole-brain analysis of the recall minus control contrast in the pooled sample at baseline. Both (a) and (b) represent activity in MNI space superimposed on an anatomical template provided by MRIcron (http://people.cas.sc.edu/rorden/mricron/index.html).

Effects of L and Z on fMRI Performance

Behavioral

The number of self-reported successful retrievals during the verbal learning task is presented by group and time point in Table 3. Importantly, the supplement and control groups showed comparable verbal learning performance at baseline (p > .05). The overall sample’s average recall was 9.02 out of the 10 total word pairs at baseline and 8.61 out of 10 post-intervention. As expected, within-scanner recall significantly correlated with actual cued recall assessed immediately post scan at both time points (baseline r=.47; p=.001; post-intervention r=.42; p=.005), differing from one another by less than two words on average at baseline (mean difference=1.61 words) and post-intervention (mean difference=0.75 words). The observed congruence suggests that participants were actively engaged in the fMRI task and put forth reasonable effort.

A mixed design ANOVA did not yield a statistically significant group (supplement vs. placebo) × time (baseline vs. post-intervention) interaction for number of words recalled within the scanner [F(1,42)=2.53; p=.119], although the effect size was large (d=.84). Analysis of simple effects indicated that the supplement group maintained a similar level of performance at post-intervention relative to baseline [t(29)=−.18; p=.856; d=.07] while the placebo group showed a statistical trend toward decline [t(13)=−1.87; p=.084] characterized by a large effect size (d=1.04).

ROI analysis

Following the encoding minus control contrast, significant group (supplement vs. placebo) × time (baseline vs. post-intervention) interactions were observed in left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (F=21.34; p=.034, FWE-corrected, cluster size: 498 voxels) and anterior cingulate cortex (F=19.63; p=.028, FWE-corrected, cluster size: 146 voxels; see Figure 3). Suprathreshold activation was not found in any of the other ROIs, although the effect was approaching significance in right hippocampus (F=15.13; p=.054, FWE-corrected, cluster size: 20 voxels). To characterize significant interactions, paired t-tests revealed increases in BOLD signal in the supplement group from baseline to post-intervention in left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (p=.014; FWE-corrected) and anterior cingulate cortex (p=.016; FWE-corrected). Importantly, the placebo group did not show activation changes in these regions over the course of the study.

Fig. 3 The above figure depicts significant (p < .05, FWE-corrected) group (supplement vs. placebo) × time (baseline vs. post-intervention) interactions during verbal learning in left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (a) and anterior cingulate cortex (b). Activity is in MNI space and superimposed on an anatomical template provided by MRIcron (http://people.cas.sc.edu/rorden/mricron/install.html).

With respect to possible intervention effects during retrieval, a 2×2 flexible factorial model did not return significant interactions in hypothesized ROIs (ps all > .05, FWE-corrected, minimum 8 contiguous voxels). Exploratory paired t-tests did, however, yield significant increases in left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (t=4.42; p=.045, FWE-corrected, cluster size: 156 voxels) and anterior cingulate cortex (t=4.45; p=.021, FWE-corrected, cluster size: 182 voxels) at post-intervention relative to baseline in the supplement group only (see Figure 4), consistent with findings during encoding. No other ROIs showed changes in BOLD signal that survived the FWE correction in exploratory analyses.

Fig. 4 The above figure shows results from exploratory paired t-tests during verbal recall. Significant (p < .05, FWE-corrected) increases in left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (a) and anterior cingulate cortex (b) were observed in the supplement group at post-intervention relative to baseline. The control group did not show activation changes in these regions over the course of the study. Activity is in MNI space and superimposed on an anatomical template provided by MRIcron (http://people.cas.sc.edu/rorden/mricron/install.html).

DISCUSSION

L and Z supplementation significantly influenced brain function on a verbal learning task relative to placebo. Rather than increasing neural efficiency as predicted, however, carotenoid consumption enhanced BOLD signal in select ROIs, including left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex. A similar pattern was observed during verbal retrieval in exploratory within-group analyses but given non-significance in the omnibus interaction, these findings must be interpreted cautiously. It is noteworthy that a nearly significant effect was observed in right hippocampus during learning, which suggests a possible influence of L and Z in this region as well. The hippocampal effect was in the hypothesized direction of reduced neural activity, although conclusions are limited without having survived statistical correction for multiple comparisons.

The observed increase in prefrontal BOLD signal seems inconsistent with cross-sectional findings from this sample at baseline, which showed a negative relationship of endogenous L and Z levels to neural activity (Lindbergh et al., Reference Lindbergh, Mewborn, Hammond, Renzi-Hammond, Curran-Celentano and Miller2016). However, it is possible the baseline and longitudinal findings are actually complementary. Within the context of the STAC-r (Reuter-Lorenz & Park, Reference Reuter-Lorenz and Park2014), high levels of L and Z consumption over the course of a lifetime may in fact buffer age-related neurophysiological decline and reduce the resulting need for compensatory scaffolding. This would be analogous to a “brain maintenance” effect as described by Nyberg, Lövdén, Riklund, Lindenberger, and Bäckman (Reference Nyberg, Lövdén, Riklund, Lindenberger and Bäckman2012).

Although Lindbergh et al. (Reference Lindbergh, Mewborn, Hammond, Renzi-Hammond, Curran-Celentano and Miller2016) measured L and Z status at a single point in time, we speculate that this cross-sectional measurement at least to some extent reflects, and would correlate with, lifetime eating behaviors. This is consistent with empirical evidence suggesting that dietary patterns are relatively stable across time, at least from childhood through adulthood (e.g., Mikkilä, Räsänen, Raitakari, Pietinen, & Viikari, Reference Mikkilä, Räsänen, Raitakari, Pietinen and Viikari2005). MPOD, one of the predictors used by Lindbergh et al. (Reference Lindbergh, Mewborn, Hammond, Renzi-Hammond, Curran-Celentano and Miller2016), has demonstrated considerable stability in adults over multiple year spans, particularly relative to serum L and Z concentrations (Beatty, Nolan, Kavanagh, & O’Donovan, Reference Beatty, Nolan, Kavanagh and O’Donovan2004; Nolan et al., Reference Nolan, Stack, Mellerio, Godhinio, O’Donovan, Neelam and Beatty2006). Accordingly, to the extent that cross-sectional L and Z levels (particularly MPOD) approximate lifetime eating behaviors, the Lindbergh et al. (Reference Lindbergh, Mewborn, Hammond, Renzi-Hammond, Curran-Celentano and Miller2016) findings may reflect a lifespan neural efficiency effect. Of course, our interpretation relies on the assumption that a “snapshot” measurement of L and Z status in old age meaningfully proxies L and Z intake across the lifespan, and some studies suggest that MPOD (and presumably brain levels) can change in the event that individuals significantly alter carotenoid intakes (e.g., Hammond et al., Reference Hammond, Johnson, Russell, Krinsky, Yeum, Edwards and Snodderly1997; Stringham & Hammond, Reference Stringham and Hammond2008). Longitudinal research will be necessary to verify our interpretations, ideally focusing on changes in both MPOD and serum L and Z concentrations in relation to brain function. Such research may need to begin as early as childhood in light of recent findings that L and Z status in 7- to 10-year-olds positively predicts hippocampal-dependent memory performance (Hassevoort et al., Reference Hassevoort, Khazoum, Walker, Barnett, Raine, Hammond and Cohen2017).

Our current RCT findings neither support nor contradict the possibility of a lifespan neural efficiency effect but rather address a somewhat different question involving the neural effect of elevated L and Z intake circumscribed to a one year period in late life. Results suggest that L and Z consumed in this fashion increases cerebral perfusion and enhances neural response during cognitive performance. While further research is required to identify mechanisms underlying this effect, studies using animal models show that antioxidants restore cerebral blood flow following traumatic brain injury (Bitner et al., Reference Bitner, Marcano, Berlin, Fabian, Cherian, Culver and Tour2012) and hypoxia-induced metabolic stress (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Du, Shih, Shen, Gonzalez-Lima and Duong2013). Aging similarly increases risk for cerebral hypoperfusion, which in turn is associated with cognitive impairment and dementia (D’Esposito, Deouell, & Gazzaley, Reference D’Esposito, Deouell and Gazzaley2003; Ruitenberg et al., Reference Ruitenberg, den Heijer, Bakker, van Swieten, Koudstaal, Hofman and Breteler2005). L and Z may counter these effects by increasing blood flow to regions at risk for poor cerebral perfusion and age-related deterioration.

The pattern of increased BOLD signal is consistent with a small number of RCTs that have examined fMRI changes related to other dietary factors. As examples, nitrates (Presley et al., Reference Presley, Morgan, Bechtold, Clodfelter, Dove, Jennings and Miller2011), pomegranate juice (Bookheimer et al., Reference Bookheimer, Renner, Ekstrom, Li, Henning, Brown and Small2013), flavanols (Brickman et al., Reference Brickman, Khan, Provenzano, Yeung, Suzuki, Schroeter and Small2014), and fish oil (Boespflug, McNamara, Eliassen, Schidler, & Krikorian, Reference Boespflug, McNamara, Eliassen, Schidler and Krikorian2016) have all been found to enhance BOLD signal relative to control conditions. Cholinesterase inhibitors have similarly increased BOLD signal in older adults during memory performance (Goekoop et al., Reference Goekoop, Rombouts, Jonker, Hibbel, Knol, Truyen and Scheltens2004; Saykin et al., Reference Saykin, Wishart, Rabin, Flashman, McHugh, Mamourian and Santulli2004). Of note, several of these interventions observed BOLD signal increases in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex specifically (e.g., Goekoop et al., Reference Goekoop, Rombouts, Jonker, Hibbel, Knol, Truyen and Scheltens2004; Presley et al., Reference Presley, Morgan, Bechtold, Clodfelter, Dove, Jennings and Miller2011; Saykin et al., Reference Saykin, Wishart, Rabin, Flashman, McHugh, Mamourian and Santulli2004), as was found in the present RCT.

Anterior cingulate cortex and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex comprise a closely related functional network (e.g., Fleck, Daselaar, Dobbins, & Cabeza, Reference Fleck, Daselaar, Dobbins and Cabeza2006; MacDonald, Cohen, Stenger, & Carter, Reference MacDonald, Cohen, Stenger and Carter2000) and together mediate executive functions (Gasquoine, Reference Gasquoine2013). Left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex monitors and manipulates verbal information to support encoding (Barbey, Koenigs, & Grafman, Reference Barbey, Koenigs and Grafman2013), and more generally subserves cognitive control processes specific to long-term memory formation (MacDonald et al., Reference MacDonald, Cohen, Stenger and Carter2000; Niendam et al., Reference Niendam, Laird, Ray, Dean, Glahn and Carter2012). This is particularly true when relationships must be built between items (e.g., word pairs; Blumenfeld, Parks, Yonelinas, & Ranganath, Reference Blumenfeld, Parks, Yonelinas and Ranganath2011) and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex activity positively correlates with success on relational encoding tasks (Blumenfeld & Ranganath, Reference Blumenfeld and Ranganath2006).

Anterior cingulate cortex is reliably activated on memory tasks as well, particularly when they are challenging or require a high level of attention (Cabeza & Nyberg, Reference Cabeza and Nyberg2000; Niendam et al., Reference Niendam, Laird, Ray, Dean, Glahn and Carter2012; Shenhav, Botvinick, & Cohen, Reference Shenhav, Botvinick and Cohen2013; Weissman, Gopalakrishnan, Hazlett, & Woldorff, Reference Weissman, Gopalakrishnan, Hazlett and Woldorff2005). Conflict detection and resolution are also rooted in anterior cingulate cortex, which may account for its role in memory decision making (Fleck et al., Reference Fleck, Daselaar, Dobbins and Cabeza2006).

Although L and Z’s behavioral effects on the verbal learning task were not statistically significant, it is notable that the effect size was large. The lack of significance may relate to inadequate power, which is a common phenomenon in fMRI studies that consider behavioral measures (Wilkinson & Halligan, Reference Wilkinson and Halligan2004). A post hoc power analysis revealed that, even with the large effect size we observed, a sample size of 46 (experimental n=31; control n=15) would have been required to detect a significant effect, if present, with a power (1 – β) of 0.90 (Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, & Lang, Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner and Lang2009; Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Lang and Buchner2007). Given that our sample size following attrition was slightly smaller than this (N=44), conclusions must be limited.

However, our findings tentatively suggest that carotenoid supplementation in old age helps maintain cognitive performance across time, possibly buffering against decline; enhanced cerebral perfusion in prefrontal regions offers a potential neural mechanism for this effect. Alternatively, L and Z may not be influencing learning and memory per se, but rather associated cognitive processes (e.g., attention). Finally, the possibility that the effects of L and Z supplementation on overt cognitive function in old age are actually quite modest must also be acknowledged. A longer supplementation period may be required (i.e., > 1 year) or perhaps L and Z intake must be elevated across the lifespan to meaningfully influence cognition.

The present study has limitations. Our sample was racially homogenous, high functioning, and well educated. Future research is warranted to determine whether results generalize to populations characterized by greater diversity and cognitive variability. This is particularly important given that elevated socioeconomic position may reduce the strength of the relationship between dietary factors and cognition (Akbaraly, Singh-Manoux, Marmot, & Brunner, Reference Akbaraly, Singh-Manoux, Marmot and Brunner2009). In light of the high average number of words recalled on the verbal learning task, future RCTs should consider changes using more sensitive neuropsychological measures and in other cognitive domains. The generalizability of our findings may also be influenced by the relatively high number of individuals who dropped out of the study (~27%), although it is encouraging that non-completers did not display any significant differences from completers on demographic and dietary factors. Still, it must be kept in mind that our dietary assessment provided only limited information about food categories, and it is possible differences existed on more specific nutritional variables that have been shown to relate to cognition (e.g., omega-3 fatty acids; Mazereeuw, Lanctôt, Chau, Swardfager, & Hermann, Reference Mazereeuw, Lanctôt, Chau, Swardfager and Herrmann2012). Finally, as with most nutrition studies, there was no true “control” group; L and Z are abundant in a variety of foods. In many respects, the observation of any brain effect beyond routine L and Z consumption in an intact and presumably well-nourished sample speaks to the robust potential for carotenoids to influence neurocognitive function.

Despite its limitations, this is the first RCT to investigate the effects of L and Z supplementation on neural function in vivo during cognitive task performance. More broadly, our results add to the paucity of research that has evaluated the potential of nutrition, a modifiable and inexpensive lifestyle factor, to promote brain health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research project was funded in part by Abbott Nutritional Products (Columbus, OH; research grant to B.R.H., L.M.R., L.S.M.) and the University of Georgia’s Bio-Imaging Research Center (administrative support, L.S.M.). DSM Nutritional Products (Switzerland) provided the supplements and placebos. Additionally, L.M.R. was an employee of Abbott Nutrition during a portion of the grant period while holding a joint appointment at the University of Georgia. B.R.H. has consulted for Abbott Nutrition. No other potential conflicts of interest exist for any of the study authors, including A.N.P., C.A.L., C.M.M., and D.P.T. All statistical analyses were completed independently of supporting agencies.