Chapter 4 Big questions, big data

One of the reasons that a society discovers itself in a crisis of long-term thinking is the problem of information overload. Information overload is not a new story in and of itself. European humanists in the Renaissance experienced it, as new editions of classical texts, new histories and chronology, and new information about the botany and fauna of Asia and the Americas rapidly swamped the abilities of scholars to aggregate information into encompassing theories or useful schedules. Indeed, many of our basic tools for search and retrieval – the index, the encyclopaedia, and the bibliography – came from the first era of information overload, when societies were feeling overwhelmed about their abilities to synthesise the past and peer into the future.1

We live in a new era of ‘big data’, from the decoding of the human genome to the billions of words of official reports annually churned out by government offices. In the social sciences and humanities big data have come to stand in for the aspiration of sociologists and historians to continued relevance, as our calculations open new possibilities for solving old questions and posing new ones.2 Big data tend to drive the social sciences towards larger and larger problems, which in history are largely those of world events and institutional development over longer and longer periods of time. Projects about the long history of climate change, the consequences of the slave trade, or the varieties and fates of western property law make use of computational techniques, in ways that simultaneously pioneer new frontiers of data manipulation and make historical questions relevant to modern concerns.3

Over the last decade, the emergence of the digital humanities as a field has meant that a range of tools are within the grasp of anyone, scholar or citizen, who wants to try their hand at making sense of long stretches of time. Topic-modelling software can machine-read through millions of government or scientific reports and give back some basic facts about how our interests and ideas have changed over decades and centuries. Compellingly, many of these tools have the power of reducing to a small visualisation an archive of data otherwise too big to read. In our own time, many analysts are beginning to realise that in order to hold persuasive power, they need to condense big data in such a way that they can circulate among readers as a concise story that is easy to tell.

While humanity has experimented with drawing timelines for centuries, reducing the big picture to a visualisation is made newly possible by the increasing availability of big data.4 That in turn raises the pressing questions of whether we go long or short with that data. There are places in the historical record where that decision – to look at a wider context or not – makes all the difference in the world. The need to frame questions more and more broadly determines which data we use and how we manipulate it, a challenge that much longue-durée work has yet to take up. Big data enhance our ability to grapple with historical information. They may help us to decide the hierarchy of causality – which events mark watershed moments in their history, and which are merely part of a larger pattern.

New tools

In the second decade of the twenty-first century, digitally based keyword search began to appear everywhere as a basis for scholarly inquiry. In the era of digitised knowledge banks, the basic tools for analysing social change around us are everywhere. The habits of using keyword search to expand coverage of historical change over large time-scales appeared in political science and linguistics journals, analysing topics as diverse as the pubic reaction to genetically modified corn in Gujarat, the reception of climate change science in UK newspapers, the representation of Chinese peasants in the western press, the persistence of anti-semitism in British culture, the history of public housing policy, and the fate of attempts by the British coal industry to adapt to pollution regulations.5 In 2011 and 2013, social scientists trying to analyse the relationship between academic publications about climate and public opinion resorted to searching the Web of Science database for simple text strings like ‘global warming’ and ‘global climate change’, then ranking the articles they found by their endorsement of various positions.6 In short, new technologies for analysing digitised databases drove a plurality of studies that aggregate information about discourses and social communities over time, but few of these studies were published in mainstream history journals.7 There was a disconnection between technologies clearly able to measure aggregate transformations of discourses over decades, and the ability, the willingness, or even the courage of history students to measure these questions for themselves.

To overcome this resistance, new tools created for longue-durée historical research, and specifically designed to deal with the proliferation of government data in our time, have become an ever more-pressing necessity. Here we give one example, drawn from Jo Guldi’s experience, of how the challenges of question-driven research on new bodies of data led to the creation of a new tool. In the summer of 2012, she led a team of researchers that released Paper Machines, a digital toolkit designed to help scholars parse the massive amounts of paper involved in any comprehensive, international look at the over-documented twentieth century. Paper Machines is an open-source extension of Zotero – a program that allows users to create bibliographies and build their own hand-curated libraries in an online database – designed with the range of historians’ textual sources in mind.8 Its purpose is to make state-of-the-art text mining accessible to scholars across a variety of disciplines in the humanities and social sciences who lack extensive technical knowledge or immense computational resources.

While tool sets like Google Books Ngram Viewer utilise preset corpora from Google Book Search that automatically emphasise the Anglo-American tradition, Paper Machines works with the individual researcher’s own hand-tailored collections of texts, whether mined from digital sources like newspapers and chat rooms or scanned and saved through optical character recognition (OCR) from paper sources like government archives. It can allow a class, a group of scholars, or scholars and activists together to collect and share archives of texts. These group libraries can be set as public or private depending on the sensitivity and copyright restrictions of the material being collected: historians of Panama have used a Zotero group library to collect and share the texts of government libraries for which no official finding aid exists. The scholars themselves are thus engaged in preserving, annotating, and making discoverable historical resources that otherwise risk neglect, decay, or even intentional damage.

With Paper Machines, scholars can create visual representations of a multitude of patterns within a text corpus using a simple, easy-to-use graphical interface. One may use the tool to generalise about a wide body of thought – for instance, things historians have said in a particular journal over the last ten years. Or one may visualise libraries against each other – say, novels about nineteenth-century London set against novels about nineteenth-century Paris. Using this tool, a multitude of patterns in text can be rendered visible through a simple graphical interface. Applying Paper Machines to text corpora allows scholars to accumulate hypotheses about longue-durée patterns in the influence of ideas, individuals, and professional cohorts.

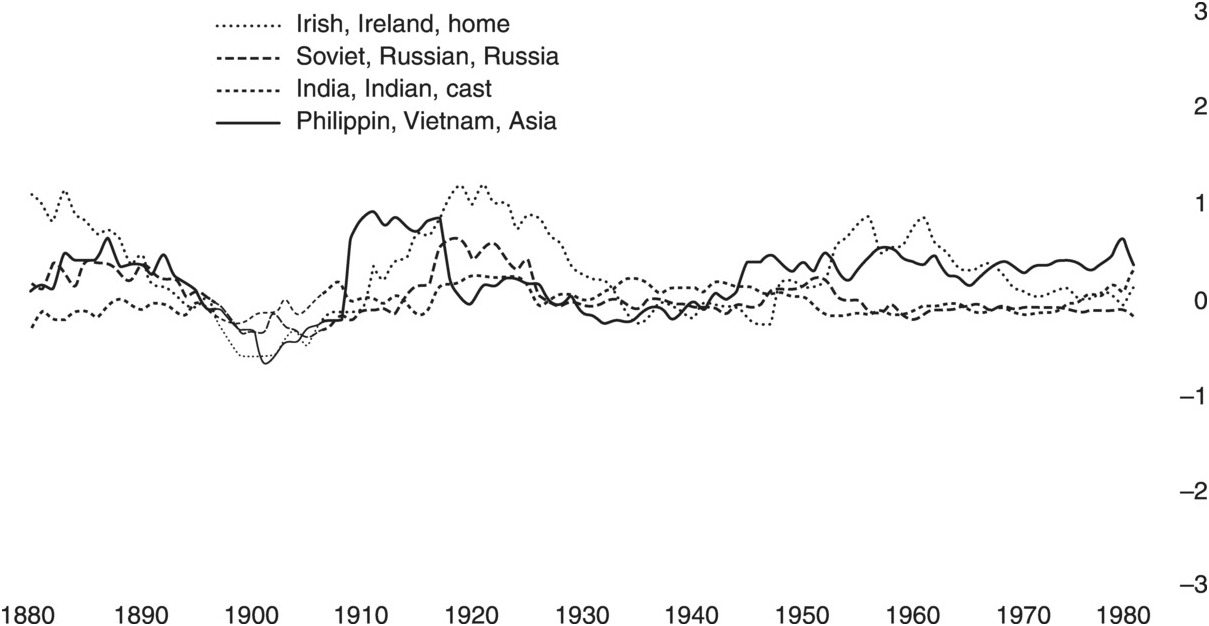

By measuring trends, ideas, and institutions against each other over time, scholars will be able to take on a much larger body of texts than they normally do. For example, in applying Paper Machines to a hand-curated text corpus of large numbers of bureaucratic texts on global land reform from the twentieth century, it has been possible to trace the conversations in British history from the local stories at their points of origin forward, leaping from micro-historical research in British archives into a longue-durée synthesis of policy trends on a worldwide scale. That digitally enabled research operates through a threefold process: digitally synthesising broad swathes of time, critically inquiring into the micro-historical archive with digitally informed discernment about which archives to choose, and reading more broadly in secondary literatures from adjacent fields. For example, in Figure 4, the topic-modelling algorithm MALLET has been run on a corpus of scholarly texts about land law. The resulting image is a computer-guided timeline of the relative prominence of ideas – some mentioning Ireland and some mentioning India – that can then be changed and fine-tuned. This visualisation of changing concepts over time guides the historian to look more closely in her corpus at the 1950s and 1960s, when the intellectual memory of land struggles in Ireland was helping to guide contemporary policy in Latin America.

Figure 4 Relative prominence of mentions of India, Ireland, and other topics in relationship to each other, 1880–1980. (Thin lines indicate fewer documents upon which to base analysis.)

This digitally driven research provides the basis for Guldi’s The Long Land War, a historical monograph telling the story of the global progress of land reform movements, tracing ideas about worker allotments and food security, participatory governance, and rent control from the height of the British Empire to the present.9 Paper Machines has synthesised the nature of particular debates and their geographic referents, making for instance timelines and spatial maps of topics and place-names associated with rent control, land reform, and allotment gardening. It has also shown which archives to choose and which parts of those archives to focus upon. Paper Machines was designed as a tool for hacking bureaucracies, for forming a portrait of their workings, giving an immediate context to documents from the archive. The user of Paper Machines can afford to pay attention to the field agents, branch heads, and directors-general of UN offices, or indeed to the intermediate faculty of the University of Wisconsin and the University of Sussex who offered advice to both bureaucrats and generations of undergraduates. The tool allows us to instantly take the measure of each of these organs, identifying the ways in which they diverge and converge. All of their staff spoke a common language of modernisation theory: of national governments, democratic reform, government-provided extension, training and management, and the provision of new equipment that resulted in quantitatively verifiable increased production.

Traditional research, limited by the sheer breadth of the non- digitised archive and the time necessary to sort through it, becomes easily shackled to histories of institutions and actors in power, for instance characterising universal trends in the American empire from the Ford and Rockefeller Foundations’ investments in pesticides, as some historians have done. By identifying vying topics over time, Paper Machines allows the reader to identify and pursue particular moments of dissent, schism, and utopianism – zeroing in on conflicts between the pesticide industry and the Appropriate Technology movement or between the World Bank and the Liberation Theology movement over exploitative practices, for example. Digitally structured reading means giving more time to counterfactuals and suppressed voices, realigning the archive to the intentions of history from below.

Other similar tools can offer metrics for understanding long-term changes over history from the banal to the profound. Google Ngrams offers a rough guide to the rise and fall of ideas.10 Humanists like Franco Moretti and historians like Ben Schmidt have been crucial collaborators in the design of tools for visualisation over time, in Moretti’s case collaborating with IBM to produce the ManyEyes software for ‘distant reading’ of large bodies of text; in Schmidt’s case, working alongside the genetic biologists who coded the software behind Google Ngrams to ensure that the software produced reliable timelines of the textual dominance of certain words from generation to generation.11

Tools such as these lend themselves to scholars looking to measure aggregate changes over decades and centuries. The arrival in the past ten years of mass digitisation projects in libraries and crowd-sourced oral histories online announced an age of easy access to a tremendous amount of archival material. Coupled with the constructive use of tools for abstracting knowledge, these digital corpora invite scholars to try out historical hypotheses across the time-scale of centuries.12 The nature of the tools available and the abundance of texts render history that is both longue durée and simultaneously archival a surmountable problem, at least for post-classical Latin – a corpus ‘arguably span[ning] the greatest historical distance of any major textual collection today’ – and for sources in major European languages created since the Renaissance.13

Tools for comparing quantitative information have come to question standard narratives of modernity. For Michael Friendly, data visualisation has made possible revisiting old theories of political economy with the best of current data on the experience of the past, for instance, using up-to-date data to recreate William Playfair’s famous time series graph showing the ratio of the price of wheat to wages in the era of the Napoleonic Wars. Friendly has proposed that historians turn to the accumulation of as many measures of happiness, nutrition, population, and governance as possible, and become experts at the comparative modelling of multiple variables over time.14 These skills would also make history into an arbiter of mainline discourses about the Anthropocene, experience, and institutions.

In law and other forms of institutional history, where the premium on precedent gives longue-durée answers a peculiar power, there will be more of such work sooner rather than later. New tools that expand the individual historian’s ability to synthesise such large amounts of information open the door to moral impulses that already exist elsewhere in the discipline of history, impulses to examine the horizon of possible conversations about governance over the longue durée. Scholars working on the history of European law have found that digital methods enable them to answer questions of longer scale: for example, the Old Bailey Online, covering English cases from the period 1673 to 1914 – the largest collection of subaltern sources now available in the English-speaking world; or Colin Wilder’s ‘Republic of Literature’ project which, by digitising early-modern legal texts and linking the text-based information to a gigantic social networking map of teachers and students of law, aims to show who drove legal change in early modern Germany, where many of our first ideas of the public domain, private property, and mutuality emerged.15 Projects of this kind offer a tantalising grip on the kind of multi-researcher questions, extending across time and space which, by aggregating information on a scale hitherto unknown, may help to transform our understanding of the history of laws and society.

In the new era of digital analysis, the watchword of the fundable project must be extensibility – will this dataset work with other forms of infrastructure? Will these texts help us to tell the long story, the big story – to fill in the gaps left by Google Books? Or is this a single exhibition, which can only be appreciated by the scholar absorbed in reflection about a decade or two? Will students scramble to get the text in a format which the tools of digital analysis can make sense of?

Long-term thinkers frequently avoid engaging digital tools for analysing the big picture. The new longue durée-ists might have been expected to step into this role of carefully analysing the data of many disciplines, as their stories synthesise and interweave narratives borrowed from other places. But they have often shied away from big data; they generally prefer to construct traditional synthetic narratives by way of secondary sources. When there is such a mismatch between goals and resources, there may yet be opportunities for more ambitious work on a larger scale. Some have heard the clarion call to return to the big picture, and some have responded to the promise of the digital toolkit. But few have used the two together, applying tools designed to analyse large troves of resources to questions about our long-term past and long-term future.

The rise of big data

In the six decades since the Second World War, the natural and the human sciences have accumulated immense troves of quantifiable data which is rarely put side by side. The rise of public debate has driven the availability of more and more time-designated data, which have been made available in interchangeable formats by governments, climate scientists, and other entities. The world needs authorities capable of talking rationally about the data in which we all swim, their use, abuse, abstraction, and synthesis. Such data have been accumulated over decades of research supporting new theses, for instance, the academic consensus on climate change. Big data have been steadily accumulating from all quarters since the first ice-cores were drilled in the 1960s and computer-based models have extended the data collected around meteorology into possible suggestions about how our atmosphere was changing in relationship to pollution.16

In history journals, these datasets have so far had relatively little impact, but in nearby fields, scientists of climate and atmosphere have tabulated global datasets for the twentieth century, a portrait of planetary droughts and floods as they increased over the century.17 Particular studies model how farms and farmers in Switzerland, the Netherlands, or the Atlantic coast of the United States have responded over the course of centuries to vanishing wetlands, surging floods, and changing maize or other crop yields influenced by rising temperatures.18 They have even experimented with datasets that correlate a range of cultural and social responses in history to moments of global climate change.19 An article in the journal Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions compares social complexity, food production, and leisure time over the last 12,000 years to the prospect of technological innovation to come, and takes information even from the fall of Rome. Climate change has been offered as evidence for China’s century-long cycles of war and peace over millennia, for the ‘General Crisis’ of the seventeenth century, and as the original cause of the civil war in Darfur.20 As a result of the accumulation of data about our deep atmospheric past, the past of the environment now appears provocatively human in its outward aspect.

Once one starts to look, the untapped sources of historical data are everywhere. Government offices collect long time-span assessments of energy, climate, and the economy. The US Energy Information Administration publishes a Monthly Energy Review going back as far as 1949. These tables of energy consumption have been analysed by climate scientists, but much less frequently by historians. Official data on population, government balance of payments, foreign debt, interest and exchange rates, money supply, and employment are collected from world governments and made available to scholars by international governance bodies like UNdata and Euromonitor International and by private databases like IHS Global Insight. The IMF has collected finance statistics for every government in the world from 1972.21 Government data collected over long-time scales have been analysed in sociology, climate science, and economics.22 These streams of data have traditionally been less frequently taken advantage of by historians, but that may be changing. As historians begin to look at longer and longer time-scales, quantitative data collected by governments over the centuries begin to offer important metrics for showing how the experiences of community and opportunity can change from one generation to the next.

There is a superabundance of quantitative data available in our time, material that was hardly available if at all in the 1970s, when history last had a quantitative turn. The historian working today can work with maps that layer atop each other decades if not centuries of international trade routes, population growth, average income, rainfall, and weather.23 She can leaf through an atlas of the international slave trade based on one of the great digital projects over the longue durée, the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database which accumulates information on some 35,000 slave voyages from the sixteenth century to the nineteenth century carrying over 12 million enslaved people.24 Using Google Earth, she can peel back transparencies made from sixteenth- to nineteenth-century maps showing London’s growth. For any study, big or small, the data that form a background to our work now abound.

Very little of the data that have been accumulated in this time has yet been interpreted. The information age – first named as such in 1962, and defined as the era when governments regularly monitored their populations and environments, collecting data on soil erosion, weather, population, and employment – has resulted, as of the twenty-first century, in the accumulation of historically deep data.25 Collected frequently enough over time, those numbers sketch the shape of changing history, changing contexts of consequences – the whole of which are rarely put together by observers inside the disciplines. These quantitative data have begun to superabound, offering rich frontiers for a new school of quantitative analysis. Yet much of that data has only been assessed in the moment, over the short time-scale of economic findings about recent trends.

The first flickering of a revolution in using macroscopic data to look at the big picture is beginning to show on the horizons of some of the world’s research universities, where interest in government-collected data has prompted a resurgence of cliometrics, which refers to the study of History (embodied by the Greek muse, Clio) through the history of things that can be quantitatively measured – wealth, goods, and services that were taxed and recorded, and population. That school was first in vogue in the 1970s, when economic historians like Robert Fogel and Stanley Engerman compared the poor nutrition of mill-labourers in the American north and slaves in the American South, using those numbers to argue that capitalism was actually worse than slavery for the victims of a society in terms of how much food a worker and a slave consumed. There was a lot to be said about Fogel’s and Engerman’s numbers, and about any sense in which slavery could be considered ‘better’ or ‘more rational’ than the market, and perhaps for the reasons of this confusion of argument, cliometrics afterwards disappeared.26 The micro-history that triumphed in those debates was, as we have seen, if anything over-fastidious in its interpretation of first-person experiences as a guide to the interpretation of slavery as well as capitalism. Banished for its sins, cliometrics has not been part of the graduate training of most students of history or in economics for some time now. But in a new era of big data, the evidence available is richer and aggregated from more institutions than before.

The counting of things that can be measured as a guide to doing history is now back in abundance, and with greater sensitivity to questions of class, race, identity, and authority than ever before. Following in the path of an older quantitative turn, data-driven historians like Christopher Dyer have returned to the use of probate records from late medieval England to demonstrate an ethos of care for the poor and sustaining the common good.27 When historian Thomas Maloney set out to learn the impact of racism on unemployed men during the Great Depression, he turned to forgotten troves of government data as well. Government records on selective service integrated with employment records allowed him to measure trends in Cincinnati over two decades, and to learn that men who lived in segregated neighbourhoods actually fared better than those on the verge of integration.28 Questions such as these illuminate the way in which a new quantitative turn is adding subtleties of racial experience and belonging, all theorised under a micro-historical turn linked to the availability of long-run datasets.

Outside history departments, however, the ambitions attached to these datasets are of much greater scale. Since the 1970s, non-profit think-tanks like Freedom House, The International Research and Exchanges Board (IREX), and the Rand Corporation have subsidised the efforts of political scientists to put together databanks that track characteristics like ‘peace’ and ‘conflict’, ‘democracy’ and ‘authoritarianism’, or ‘freedom of the press’ and ‘human rights’ across the nations of the world.29 Since the late 1990s, some of these datasets have incorporated information about time, tracking collections of events related to the expansion of rights, reaching back to 1800 and forward up to the present.30 While some of these datasets are personal or proprietary, others are available for sharing, and this sharing has generated innovation in the way we understand these variables. Big data can also push historical insight into the nature of inequality. Economic historians and sociologists are already tracking inequality over centuries and across nations, searching for the patterns of belonging, and preliminary studies have begun to demonstrate the wide variability in the experience of men and women, blacks and whites, migrants and stationary people across large time-scales as well.31

The richness of so much data on the long term raises important methodological issues of how much background any scholar should possess to understand a particular moment in time. When mapped against histories of weather, trade, agricultural production, food consumption, and other material realities, the environment interweaves with human conditions. Layering known patterns of reality upon each other produces startling indicators of how the world has changed – for instance, the concentration of aerosols identified from the mid twentieth century in parts of India has been proven to have disrupted the pattern of the monsoon in the latter part of the twentieth century.32 Maps that layer environmental disturbances and human events onto each other already reveal how humans are responding to global warming and rising sea-levels. In parts of the Netherlands, rising waters had already begun to shift the pattern of agricultural cultivation two hundred years ago.33 By placing government data about farms next to data on the weather, history allows us to see the interplay of material change with human experience, and how a changing climate has already been creating different sets of winners and losers over decades.

The implications of these studies are immense. Even before the advent of big data, in 1981 Amartya Sen had already established a correlation between higher levels of democracy and averting famines.34 But more recently scholars dealing with big data have used historical indexes of democracy and WHO-provided indexes of disease, life expectancy, and infant mortality to establish a pattern that links democracy to health in most nations’ experience over the course of the twentieth century.35 Different kinds of data provide correlations that evince the shape of the good life, demonstrating how societies’ relationships with particular health conditions change dramatically over a century.36 The data also suggest how different the experience of history can be from one part of the world to the next, as in the farming regions where agricultural productivity produced a generation of short adults, marked for the rest of their life by malnourishment.37 Aggregated historically across time and space, in this way big data can mark out the hazards of inequality, and the reality of systems of governance and market that sustain life for all.

What all of this work proves is that we are awash in data – data about democracy, health, wealth, and ecology; data of many sorts. Data that are assessed, according to the old scheme of things, appears in several different departments – democracy in political science or international relations; wealth in sociology or anthropology; and ecology in earth science or evolutionary biology. But data scientists everywhere are starting to understand that data of different kinds must be understood in their historical relationship. Aerosol pollution and the changing monsoon have a causal relationship. So do rising sea-levels and the migration of farmers. All of the data are unified by interaction over time. Creative manipulation of archives of this kind give us data unglimpsed by most economists and climate scientists. When data are expanded, critiqued, and examined historically from multiple points of view, ever more revealing correlations become possible.

Invisible archives

One of the particular tricks of the historian is to peer into the cabinet of papers marked ‘DO NOT READ’, to become curious about what the official mind has masked. This tactic, too, is gaining new life in an era of big data. Rich information can help to illuminate the deliberate silences in the archive, shining the light onto parts of the government that some would rather the public not see. These are the Dark Archives, archives that do not just wait around for the researcher to visit, but which rather have to be built by reading what has been declassified or removed. Here, too, big data can help to tell a longer, deeper story of how much has disappeared, when, and why.

In the task of expanding the archive in ways that destabilise power, historians are taking the lead. Historian Matthew Connelly devised a website which he calls a ‘Declassification Engine’, designed for helping the public to trace unpublished or undocumented US Department of State reports. The techniques he has used should make it possible to perform a distant reading of reports that were never even publicly released. In fact, his research has revealed an enormous increase in declassified files since the 1990s. Rather than classifying specific files understood to be deeply sensitive because of individuals or projects named therein, in the 1990s the US government began to automatically withhold entire state programmes from public access. By crowd-sourcing the rejection of requests for Freedom of Information Acts, Connelly’s Declassification Engine was able to show the decades-long silencing of the archives.38

In the era of the NGO, government-sourced data streams have been supplemented by multiple other datasets of human experience and institutions over time, made possible by the crowd-sourcing power of the Internet. The use of the Internet for collecting and sharing data from various sources has also given rise to the bundling of new collections of data by non-governmental activist groups monitoring the path of capitalism. Indeed, social scientists have been compiling their own datasets for generations, but since the 1990s many of those datasets have been computerised and even shareable.39 The result is a generation of databases critical of both nation-states and corporations, which give evidence for alternative histories of the present. In 2012, four German research universities banded together with the International Land Coalition to begin collecting information on the nearly invisible ‘land grab’ happening across the world as a result of the mobilisation of finance capital.40 In the era of data, we can make visible even those histories that both the state and investors would rather we not tell.

What is true of the International Land Coalition is likely true for many groups: in an age of big data, one activist stance is to collect information on a phenomenon invisible to traditional governments, and to use those data as themselves a tool for international reform. Similar activist databases exist in Wikileaks, the famous trove of whistle-blower-released national papers, and Offshoreleaks, in the context of tax havens, those international sites for individuals and corporations diverting their profits from nation-states, for which journalist Nicholas Shaxson has written a preliminary history of the twentieth century in his Treasure Islands (2011).41

For the moment, the data collected in banks such as these only cover a short historical spectrum, but it begs for supplementation by historians capable of tracing foreign investment in postcolonial real estate – a subject that would look backwards at the history of resource nationalism in the 1940s and 1950s, and at the sudden reversal in the recent decade of these laws, as nations like Romania, Bulgaria, and Iceland open their real estate to international speculation for the first time in a half-century.

Dark Archives and community-built archives dramatise how much big data can offer us in terms of a portrait of the present – what our government looks like now, where investment is moving, and what is the fate of social justice today. Combined with other kinds of tools for analysing the past, including the topic modelling and other tools we discussed above, digital analysis begins to offer an immense toolset for handling history when there is simply too much paper to read. We are no longer in the age of information overload; we are in an era when new tools and sources are beginning to sketch in the immense stretches of time that were previously passed over in silence.

Evidence of displacement and suppression needs to be kept. It is the most fragile and the most likely to perish in any economic, political, or environmental struggle. A few years ago, biodiversity activists in England erected a memorial to the lost species, known and unknown, which perished because of human-caused climate change.42 Even old archives can be suddenly repurposed to illuminating big stories about extinction events, as with the eighteenth-century natural history collections gathered by naturalists working for the East India Company and others that have been used by ecologists to reconstruct the pattern of extinctions that characterised the Anthropocene.43 We need libraries populated with information on plants, animals, and also indigenous peoples and evicted or forgotten peoples, the raw data for Dark Archives of stories that it would be only too convenient to forget. Preservation and reconstruction of datasets in the name of larger ethical challenges poses a worthy challenge for historians of science. They will give us a richer, more participatory picture of the many individuals who experience economic inequality and environmental devastation, of the many hands that have wrought democracy and brought about the ‘modern’ world.

As we have seen, those tools for illuminating the past frequently reverberate back on our understanding of the future: they change how we understand the possibilities of sustainable city building, or inequality over the last few centuries; they help activists and citizens to understand the trajectory of their government, and how to interpret the world economy. All of these means of doing history are also crucial for making sense of world events in present time, and they represent an emerging technology for modelling the background for a long-term future.

How then should we think about the future and the past?

Digitisation by itself is not sufficient to break through the fog of stories and the confusion of a society divided by competing mythologies. Cautious and judicious curating of possible data, questions, and subjects is necessary. We must strive to discern and promote questions that are synthetic and relevant and which break new methodological ground. Indeed, the ability to make sense of causal questions, to tell persuasive stories over time, is one of the unresolved challenges facing the information industry today. Famously, neither Google nor Facebook has had much success in finding an algorithm that will give the reader the single most important news story from their wall or from the magazines over the last year. They can count the most viewed story, but the question of the most influential has challenged them. Experimenting with timelines that would make sense of complex real-world events, Tarikh Korula of TechCrunch and Mor Naaman of Cornell University have produced a website called Seen.co, which charts in real time the relative ‘heat’ of different hashtags on Twitter.44 This enterprise points to the hunger in the private sector for experts who understand time – on either the short durée or the long. Similarly, another event-tracking site, Recorded Future, finds synchronicities and connections between stories, concentrating around particular companies or investment sectors, with a client base of intelligence and corporate arbitrage.45 Its CEO, Christopher Ahlberg, describes its mission as ‘ help[ing] people [to] see all kinds of new stories and structures in the world’.46 The skill of noticing patterns in events, finding corrrelations and connections – all the bailiwick of traditional history – was held by Google to be such a worthwhile venture that the reported initial investment in the company in 2014 was tagged at $8 billion.

The life of the Paper Machines software offers another illustration. Paper Machines was created in 2012 and refined through 2013–14, producing a small number of papers and a large number of blog entries and tweets by faculty and graduate students reflecting on their experience in using it in pedagogy and research. By 2013, however, it had also been adopted by a military intelligence firm in Denmark, advising Danish national intelligence about the nature of official reports from other world intelligence forces.47 Those governments, much like the historical governments that Paper Machines was designed to study, produce too much paper to read – indeed, too much intelligence for other national governments to make useful sense of it. Identifying historical trends that concerned different national security forces turned out to be vital to the efficient processing of official information.

In the decades to come, the best tools for modelling time will be sought out by data scientists, climate scientists, visualisation experts, and the finance sector. History has an important role to play in developing standards, techniques, and theories suited to the analysis of mutually incompatible datasets where a temporal element is crucial to making sense of causation and correlation. Experts trying to explain the history and prospects of various insurance, real-estate, manufacturing, ecological, or political programmes to potential shareholders all need experts in asking questions that scale over time. All of these potential audiences also raise concerns, for many historians, of the moral implications of forms of history that evolve to answer real-world and practical problems.

How the age of big data will change the university

The scale of information overload is a reality of the knowledge economy in our time. Digital archives and toolsets promise to make sense of government and corporate data that currently overwhelm the abilities of scholars, the media, and citizens. The immensity of the material in front of us begs for arbitrators who can help make sense of data that defy the boundaries of expertise – data that are at once economic, ecological, and political in nature, and that were collected in the past by institutions whose purposes and biases have changed over time. Big data will almost certainly change the functions of the university. We believe that the university of the future needs not only more data and greater mathematical rigour, but also greater arbitration of the data that were collected over time.

There are still reasons to think that a university education is the proper site for long-term research into the past and future, and that such an education should be in high demand at a moment when climates, economies, and governments are experiencing so much flux. The university offers a crucial space for reflection in the lives of individuals and societies. In a world of mobility, the university’s long sense of historical traditions substitutes for the long-term thinking that was the preserve of shamans, priests, and elders in another community. We need that orientation to time insofar as we too want to engage the past in order to better explore the future.

Many of the experts in the modern university are nonetheless ill equipped to handle questions such as these. Even on shorter scales, scientists trained to work with data can sometimes err when they begin to work with big data that were accrued by human institutions working over time. A paper by geographers tried to answer the question of whether the public was responding to data about climate change by keyword searching the ISI Web of Knowledge database for the key topic terms ‘climat* chang*’ and ‘adapt*’.48 Does a word-count of this kind really pass on information about climate change as a rising priority in America? A strategy such as this would never pass muster in a history journal. As we have shown in Chapter 3, even a mountain of evidence about climate change collected by scientists is no indication of public consensus in the world outside the academy. But even on a much more fine-grained level, the analysis described in this project is problematic. Even the strings chosen exclude discourse-dependent variations like ‘global warming’ and ‘environmental change’. Still more importantly, discussion of adaptation among academics is hardly a metric of political action in the outside world.

Even more telling is the case of the data that Americans use to talk about the past and future of unemployment. This measure of national economic well-being circulates among political scientists, economics, and the international media as shorthand for what is politically desirable as a goal for us all. But according to Zachary Karabell, a financial analyst as well as an accredited historian of the indicators with which we measure our society, the way we use the measure of unemployment itself is laden with the biases of short-term thinking. Unemployment excludes many kinds of work from its count, which was originally developed under the New Deal, and true to the biases of its time excludes from the category of ‘employment’ every time an urban farmer starts up a project and all household labour performed by women who have opted to take care of their children or parents rather than seeking employment in the workforce. It also represents a peculiarly short-term horizon for measuring economic well-being or certain goals. Because no institution offered a statistic for ‘unemployment’ of a kind commensurate with our own measure before 1959, many ‘supposed truisms’ of success and failure in a presidential election turn out to be false, writes Karabell. These accepted truisms including the belief, repeated in nearly every electoral cycle, that no American president can be reelected with an unemployment rate above 7.2 per cent. Such fictions ‘are based on barely more than fifty years of information’, writes Karabell. That time horizon, this historian shows, is ‘hardly a blip in time and not nearly enough to make hard and fast conclusions with any certainty’.49

In almost every institution that collects data over time, the way those data are collected is refined and changed from one generation to the next. When Freedom House, the NGO founded in 1941, began collecting datasets on peace, conflict, and democratisation, the metrics it used stressed freedom of the press; a very different standard from the Polity Project’s measures of democracy and autocracy in terms of institutions, developed decades later. Those shifting values in political science mean that the Freedom House and Polity metrics of democracy are both useful, albeit for different projects.50 In other fields, however, the outmoding of measures can cause grave difficulties in the usefulness of data altogether. Not only are measures like employment, the consumer price index (CPI), inflation, or gross domestic product (GDP) calculated on the basis of the way we lived in the era before the microwave oven, but also its theories and supposed laws may reflect enduring biases of old-world aristocrats and Presbyterian elders. According to Karabell, this is one reason why financial institutions in our era are abandoning traditional economic measures altogether, hiring mathematicians and historians to contrive ‘bespoke indicators’ that tell us more about the way we live now.51

We have been navigating the future by the numbers, but we may not have been paying sufficient attention to when the numbers come from. It is vital that an information society whose data come from different points in time has arbiters of information trained to work with time. Yet climatologists and economists nonetheless continue to analyse change over time and to take on big-picture questions of its meaning, including the collapse of civilisations like Rome or the Maya, usually without asking how much of our data about each came from elites denouncing democracy as the source of social breakdown or from later empires trumpeting their own victory.52 In an age threatened by information overload, we need a historical interpretation of the data that swarm over us – both the official record of jobs, taxes, land, and water, and the unofficial record of Dark Archives, everyday experience, and suppressed voices.

War between the experts

The arbitration of data is a role in which the History departments of major research universities will almost certainly take a lead; it requires talents and training which no other discipline possesses. In part, this role consists of the special attachment to the interpretation of the past harboured by historians around the world. Many of the dilemmas about which data we look at are ethical questions that historians already understand. In an era when intelligence services, the finance sector, and activists might all hope to interpret the long and short events that make up our world, historians have much to offer. If History departments train designers of tools and analysts of big data, they stand to manufacture students on the cutting edge of knowledge-making within and beyond the academy.

History’s particular tools for weighing data rest on several claims: noticing institutional bias in the data, thinking about where data come from, comparing data of different kinds, resisting the powerful pull of received mythology, and understanding that there are different kinds of causes. Historians have also been among the most important interpreters, critics, and sceptics investigating the way that ‘the official mind’ of bureaucracy collects and manages data from one generation to the next. The tradition of thinking about the past and future of data may lead back to Harold Perkin’s history of the professions, or before that to Max Weber’s work on the history of bureaucracy.53 What their work has consistently shown is that the data of modern bureaucracy, science, and even mathematics is reliably aligned with the values of the institution that produced it. Sometimes that takes the form of bias on behalf of a particular region that funds most of the projects, as it did for the American Army Corps of Engineers. Sometimes it takes the form of bias on behalf of experts itself – bias that shows that the resources of the poor can never amount to much in a market economy; bias that suggests that economists are indispensable aids to growing the economy, even when most of their scholarship merely supports the concentration of already existing wealth in the hands of the few.54 Historians are trained to look at the various kinds of data, even when they come from radically different sources. These are skills that are often overlooked in the training of other kinds of analysts; the reading of temporally generated sequences of heterogeneous data is a historian’s speciality.

The critique of received mythology about history goes by the name of ‘metanarratives’. Since the 1960s, much work in the theory and philosophy of history has concentrated on how a historian gains a critical perspective on the biases of earlier cultures, including the prejudice that Protestant, white, or European perspectives were always the most advanced. Scepticism towards universal rules of preferment is one vital tool for thinking about the past and the future. There is, so far as history can teach, no natural law that predicts the triumph of one race or religion over another, although there are smaller dynamics that correlate with the rise and fall of particular institutions at particular times, for example access to military technology and infrastructure on an unprecedented scale.55 This scepticism sets historians aside from the fomenters of fundamentalisms about how democracy or American civilisation is destined to triumph over others.

We live in an age where big data seem to suggest that we are locked into our history, our path dependent on larger structures that arrived before we did. For example, ‘Women and the Plough’, an economics article in a prestigious journal, tells us that modern gender roles have structured our preferences since the institution of agriculture.56 ‘Was the Wealth of Nations Determined in 1000 bc?’ asks another.57 Evolutionary biology, much like economics, has also been a field where an abundance of data nevertheless has only been read towards one or two hypotheses about human agency. The blame is placed on humans as a species, or on agriculture, or on the discovery of fire. Our genes have been blamed for our systems of hierarchy and greed, for our gender roles, and for the exploitation of the planet itself. And yet gender roles and systems of hierarchy show enormous variations in human history.

When some scholars talk in this way of unchanging rules inherited from hunter-gatherer ancestors, they themselves may forget, persuaded by the bulk of accumulated evidence, that their theory, translated via Darwin and Malthus, remains at its core a philosophy which reasons that an unchanging earth gave to all of its creatures, humankind included, stable patterns of action, which they defied at their peril. In the world of the evolutionary biologist and neo-liberal economist, the possibility of choosing and curating multiple futures itself seems to disappear. These are reductionist fictions about our past and future merely masquerading as data-supported theories; the historian notices that they are also outmoded ones.

At other times, the repeated story instructs us about how to govern our society and deal with other people. When economists and political scientists talk about Malthusian limits to growth, and how we have passed the ‘carrying capacity’ of our planet, historians recognise that they are rehearsing not a proven fact, but a fundamentally theological argument. Modern economists have removed the picture of an abusive God from their theories, but their theory of history is still at root an early nineteenth-century one, where the universe is designed to punish the poor, and the experience of the rich is a sign of their obedience to natural laws.58 Today, anthropologists can point to the evidence of many societies, past and present, where the divisions of class are not expressed in terms of ejectment or starvation.59

The reality of natural laws and the predominance of pattern do not bind individuals to any particular fate: within their grasp, there still remains an ability to choose, embodied in individual agency, which is one cause among many working to create the future. But this is not how many disciplines today reason. As Geoffrey Hodgson has concluded in his analyses of modern economics as a discipline, ‘mainstream economics, by focusing on the concept of equilibrium, has neglected the problem of causality’. ‘Today’, Hodgson concludes, ‘researchers concerned wholly with data-gathering, or mathematical model building, often seem unable to appreciate the underlying problems’.60

Outside of History departments, few scholars are trained to test the conclusions of their own field against conclusions forged on the other side of the university. Biologists deal with biology; economists with economics. But historians are almost always historians of something; they find themselves asking where the data came from – and wondering how good they are, even (or especially) if they came from another historian. In traditional history, multiple causality is embedded in the very structure of departments, such that a student of history gains experience of many possible aspects of history and its causation by taking classes in intellectual history, art history, or history of science – subjects that reflect a reality forged by many hands. Almost every historian today tends to fuse these tools together – they are a historian who deals with the social experience in an ecological context of intellectual ideas and diplomatic policy. In other words, if they treat the last two centuries, they are handling the recorded experience of working-class people, given an ecological disaster, and making a connection to what lawyers said and politicians did. These modern historians at least work, as historian James Vernon urges, ‘to write a history of global modernity that is plural in cause and singular in condition’.61 They are putting the data about inequality and policy and ecosystems on the same page, and reducing big noise to one causally complex story.62

In a world of big data, the world needs analysts who are trained in comparing discrete sets of incompatible data, quantitative and qualitative; words about emotions in court records; judging climate change against attitudes towards nature and its exploitation held by the official mind or the mind of the entrepreneur. Who can tell us about the differences between the kinds of rationality used in climate debates and the kinds of rationality used in talking about inequality? Are these stories really irreconcilable?

Without historians’ theories of multiple causality, fundamentalism and dogmatism could prevail. In this diminished understanding of history, there can be barely more than one imaginable future. Because we are allegedly creatures predetermined by an ancient past, the story goes, our choices are either a future of environmental catastrophe or rule by self-appointed elites, whether biological or technological. By raising the question of how we have learned to think differently from our ancestors, we separate ourselves from uncritical use of data and theories that were collected by another generation for other purposes.63

Historians should be at the forefront of devising new methodologies for surveying social change on the aggregate level. At the very least, they should be comparing and contrasting keyword-enabled searches in journals, policy papers, and news against economic reports and climate data, and even aggregated keyword searches and tweets. These streams of electronic bits comprise, to a great degree, the public context of our time. Historians are the ideal reviewers of digital tools like Ngrams or Paper Machines, the critics who can tell where the data came from, which questions they can answer and which they cannot.

The research university is reborn … with an ethical slant

The methods for handling big data as a historic series of events are still new. We need tools for understanding the changing impact of ideas, individuals, and institutions over time. We need universities to educate students who can turn big data into longue-durée history, and use history to understand which data are applicable and which not. Were historians to return to the longue durée, rather than ignoring it or treating it purely second-hand, they would find themselves in the position of critics of the multiple kinds of data that we have outlined here. Climate data, biodiversity data, data about modern institutions and laws over the last millennia or previous five centuries, prison records, linguistic evidence of cultural change, grand-scale evidence of trade, migration, and displacement are all in the process of being compiled. What is desperately needed is a training capable of weaving them together into one inter-related fabric of time.

The era of fundamentalism about the past and its meaning is over – whether that fundamentalism preaches climate apocalypse, hunter-gatherer genes, or predestined capitalism for the few. Instead, it is time to look for leadership to the fields that have fastidiously analysed their data about the human experience and human institutions. We should invest in tools and forms of analysis that look critically at big data from multiple sources about the history and future of our institutions and societies. Our ability to creatively and knowledgeably shape a viable future in an era of multiple global challenges may depend upon it.

If these revolutions are to pass, historians themselves will have to change as well. They have a future to embrace on behalf of the public. They can confidently begin writing about the big picture, writing in a way transmissible to non-experts, talking about their data, and sharing their findings in a way that renders the power of their immense data at once understandable by an outsider. Their training should evolve to entertain conversations about what makes a good longue durée narrative, about how the archival skills of the micro-historian can be combined with the overarching suggestions offered by the macroscope. In the era of longue-durée tools, when experimenting across centuries becomes part of the toolkit of every graduate student, conversations about the appropriate audience and application of large-scale examinations of history may become part of the fabric of every History department. To reclaim their role as arbiters and synthesisers of knowledge about the past, historians will be indispensable to parse the data of anthropologists, evolutionary biologists, neuroscientists, historians of trade, historical economists, and historical geographers, weaving them into larger narratives that contextualise and make legible their claims and the foundations upon which they rest.

This challenge may have the effect of forcing historians to take a more active role in the many public institutions that govern the data about our past and future, not only government and activist data repositories but also libraries and archives, especially ones that run at cross-purposes with state-making projects where it would be convenient for certain political elites if the documentary evidence of particular ethnicities were erased altogether.64 Societies in the grip of displacement are societies the least likely to have the resources to preserve their own histories. Someone must be responsible for the data that we – and future generations – use to understand what is happening in the world around us.

If historians are to take on the dual roles of arbiter of data for the public and investigator of forgotten stories, they will also need to take a more active part in preserving data and talking to the public about what is being preserved and what is not. Digitisation projects in a world dominated by anglophone conversations and nationalist archives raise issues of the representation of subalterns and developing nations, of minority languages and digital deficits. Where funding for digital documents is linked to nation building projects (as it is in many places), digital archives relating to women, minorities, and the poor risk not being digitised, or, where they are digitised, being underfunded or even unfunded. Just as books need correct temperature and humidity lest they decompose, so do digital documents require ongoing funding for their servers and maintenance for their bits. The strength of digital tools to promote longue-durée synthesis that includes perspectives other than that of the nation-state rests upon the ongoing creation and maintenance of inclusive archives.

Questions such as these draw deeply from the traditions of micro-history with its focus on how particular and vulnerable troves of testimony can illuminate the histories of slavery, capitalism, or domesticity. And, indeed, questions about how to preserve subaltern voices through the integration of micro-archives within the digitised record of the longue durée form a new and vitally important frontier of scholarship. That immense labour, and the critical thinking behind it, deserves to be recognised and rewarded through specially curated publications, grants, and prizes aimed at scholars who address the institutional work of the longue-durée micro-archive. This is another form of public work in the longue durée, one that aims less at public audiences and books with high sales or reading among bureaucrats than at the careful marshalling of documents, objects, stories, resources, and employment to create the micro-archival structure for macro-historical stories of genuine importance.

If historians – or any other historically minded scholars, from students of literature to sociologists – take up this challenge, they may find themselves in the avant garde of information design. They could collaborate with archivists, data scientists, economists, and climate scientists in the curating of larger and more synthetic databases for studying change over time. In the future, historians’ expertise could be sought out in sectors beyond the university. Historians may become tool-builders and tool-reviewers as well as tool-consumers and tool-teachers. Indeed, these changes have the potential to revolutionise the life of some professional historians, as faculty provide data analysis for legislative committees, advise activist campaigns, or consult with Silicon Valley startups, and thereby regain the public role they traditionally occupied and deserve once more to regain. Changes such as these may in turn change both how and who we recruit as future historians, as time spent in other professional arenas or training in computer science will become a potential asset to the field.

In the future, we hope to look forward to digital projects that take advantage of computers’ ability to analyse data at scale. We hope that modes of historiography will ponder the way these projects have or can make interventions in history produced by the single-scholar model of archival readings, synthesising current work and advancing the horizons of what an individual researcher will see. Above all, we hope that these problems of data from multiple sources – material, economic, demographic, political, and intellectual – can be overlaid against each other to produce unanticipated discoveries about change over time and the nature of the contemporary world in which we live.

The long-term perspective of the past can help those talking about the future to resist the kind of dogmatic thinking about past and future that we outlined in Chapter 3. In a world where creationists, environmentalists, and free-market theorists rarely argue against each other, we need experts who are willing to talk about our data in aggregate over the longue durée, to examine and compare the data around us, to weed out what is irrelevant and contrived, and to explain why and how they do so. History can serve as the arbiter here: it can put neo-liberalism, creation, and the environment on the same page; it can help undergraduates to negotiate their way through political and economic ideologies to a sensitivity of the culture of argumentation of many experts and the claims upon which their data rest.

Tools of critical historical thinking about where data come from, about multiple causality, and about bias will free us from the mythologies of natural laws propounded about market, state, and planetary fate in our time, stories that spell starvation and destruction for the masses. They will make clear that dogmatic thinking about the market or the climate that leads to the abandonment of our fellow human beings is a choice, and that other worlds are possible. And they will accomplish that by looking at the hard data of our planetary resources, their use, and the many alternatives displayed in the deep past and the various possible futures.

By focusing on perspectives such as these – and how they disrupt the institutions around us, and lead to better-informed citizens and more open government – universities can learn anew what it means to serve the public. Open-source, reusable tools, building upon existing resources, will encourage historians and indeed the public to look at events in their deep contexts, drawing out the most important narratives possible for a history of the present. Tools for synthesising information about change over time are of increasing importance in an era marked by a crisis about the future, when most institutions do their planning on cycles of less than five years. Yet the strength of big data and digital tools for analysis heralds a future where governments, activists, and the private sector all compete with their own models for understanding long-term prospects.

That demand for information about our past and future could create a new market for tools that synthesise enormous amounts of data about how climate and markets have changed and how governments and public experience have responded. In an era of expanding data, more of those tools for synthesis are surely coming. In the future, historians may step into new roles as data specialists, talking in public about other people’s data, using their own scholarship to compare and contrast the methods of growth economists with the warnings of climate scientists.

There are many humanists and historians in the university who will baulk at an argument that data are indeed the future of the university. The decisions about whether to go long or short, whether to use received consensus or not, and how to use big data are as much ethical questions as methodological ones. Are we content, as historians, to leave the ostensible solutions to those crises in the hands of our colleagues in other academic departments? Or do we want to try to write good, honest history that would shake citizens, policy-makers, and the powerful out of their complacency, history that will, in Simon Schama’s words, ‘keep people awake at night’?65