6.1 Introduction

The urgency to halt and reverse the alarming rates of biodiversity loss is grounded in the most comprehensive and up-to-date evidence (e.g. Reference DasguptaDasgupta, 2021; Reference Díaz, Settele and BrondízioDíaz et al., 2019) and has been translated into a forward-looking governance agenda for stimulating biodiversity conservation (CBD, 2020a; see Chapter 1 for a more detailed overview). Preparations for this Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework have centralized the issue of raising the financial resources necessary for promoting this agenda. This outlook has spurred a wealth of new publications in recent years that address the financial challenges for the foreseeable future (OECD, 2019; 2020; Reference Tobin-de la Puente and MitchellTobin-de la Puente and Mitchell, 2021; Reference Turnhout, McElwee and Chiroleu‐AssoulineTurnhout et al., 2021; UNDP, 2018; 2020). Although the new challenges raised by the COVID-19 pandemic have postponed the development of the Post-2020 framework (see Chapter 1), they have also kindled debates on a reconfiguration of the global economic system through a “green recovery” that potentially benefits biodiversity conservation (Reference McElwee, Turnout and Chiroleu-AssoulineMcElwee et al. 2020; Reference Sandbrook, Gómez-Baggethun and AdamsSandbrook et al. 2020). These developments underline that now is the right time for critically reflecting on how to maintain and enhance a biodiverse world.

Building primarily on a critical review of literature on biodiversity finance instruments, in this chapter we aim to take these reflections a step further by assessing the role of finance from the transformative biodiversity governance perspective adopted in this book. This perspective emphasizes the necessity of a transformative change to address the underlying drivers of biodiversity loss. To realize this change, this book argues that governance approaches must be integrative, inclusive, adaptive, transdisciplinary and anticipatory (see Chapter 1). We start by defining biodiversity finance, classifying the diversity of instruments that it encompasses and exploring the challenges that it seeks to address. This sets the stage for a critique of the fundamental premises of what we refer to as “innovative financial instruments” (see below) based on four interrelated questions that capture the five dimensions of transformative governance.

1. How comprehensive is “financeable” biodiversity? Biodiversity finance conceptualizes nature from an anthropocentric, mechanical and managerial perspective;

2. Who values “financeable” biodiversity (and how)? Although transformative governance requires a recognition of value pluralism, biodiversity finance instruments inherently transpose monetary values;

3. How does biodiversity finance deal with uncertainty? Biodiversity finance instruments frame biodiversity loss as a (manageable) material risk;

4. How profound are the transformative changes fostered by biodiversity finance? There are many ways in which biodiversity finance can foster integrative governance, but it does not challenge the systemic drivers of biodiversity loss.

Our critical reflection on biodiversity finance instruments and their role in a broader governance setting points to the strengths and weaknesses of these instruments, which are presented and discussed in the concluding section.

6.2 Key Developments in Biodiversity Finance

In this section, we provide our understanding of biodiversity finance, which serves as the basis for critique in the subsequent section. We start by arguing that despite the broad range of instruments, most biodiversity finance instruments have common roots in a “nature-as-natural-capital” view (see Reference SullivanSullivan, 2018). Subsequently, we discuss three interrelated arguments found in the literature that reflect the core challenges for biodiversity finance (see Reference Anyango-van ZwietenAnyango-van Zwieten, 2021). First, it is generally asserted that there is a “funding gap” for biodiversity conservation, which leads to the argument that financial instruments need upscaling. Second, one of the primary candidates for this upscaling is a greater involvement of the private sector and market-based instruments, as most biodiversity finance still comes from public sources. Third, key to leveraging or “unlocking” private finance for conservation are financial instruments built on the view of biodiversity loss as material risk (Reference DempseyDempsey, 2016). These three combined arguments are the primary target of our critical assessment in Section 6.3.

6.2.1 The Diversity of Biodiversity Finance

Biodiversity finance encompasses a diversity of instruments. A widely used definition provided by UNDP (2018: 6) describes biodiversity finance as “the practice of raising and managing capital and using financial and economic mechanisms to support sustainable biodiversity management” (see Reference Tobin-de la Puente and MitchellTobin-de la Puente and Mitchell, 2021). Alternatively, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2020: 7) refers to biodiversity finance as any “expenditure that contributes – or intends to contribute – to the conservation, sustainable use and restoration of biodiversity.” These definitions suggest a breadth of possibilities and require some sorting out. The lexicon offered by Reference PirardPirard (2012) offers some clarity. It states, firstly, that not all economic instruments are markets, pointing to regulatory price signals (e.g. eco-taxes) or voluntary price signals (e.g. certification, labels, norms) that intervene in existing markets to correct for market failures. There is also the establishment and regulation of “direct markets” for products and services directly derived from biodiverse ecosystems, such as ecotourism, forest and fisheries products, and others. Finally, we group together three remaining categories – Reference PirardPirard (2012) refers to these as “tradable permits” (e.g. carbon credits or fishing quotas), “reverse auctions” (e.g. payments for ecosystem services – PES) and “coasean-type agreements” (e.g. conservation easements or concessions) – that demand innovative ways of addressing biodiversity loss through processes of agreements, auctions or trade. Moreover, these categories encompass instruments that are highly heterogeneous with respect to the type of exchange and the involvement of public and/or private organizations (Reference Koh, Hahn and BoonstraKoh et al., 2019; Reference Pirard and LapeyrePirard and Lapayre, 2014). This chapter primarily addresses this third heterogenous conglomerate of categories, also referred to as “innovative financial mechanisms” (Reference Anyango-van ZwietenAnyango-van Zwieten, 2021), which is distinct from other instruments that are premised on the stimulation or correction of existing social relations (i.e. direct markets and regulatory and voluntary price signals). They are innovative in the way in which they materialize specifically for biodiversity conservation in new hybrid forms of governance arrangements and represent new products and services, including through modifications to traditional mechanisms.

Although quite comprehensive, Reference PirardPirard’s (2012) lexicon does not encompass all biodiversity finance, as the role of the financial sector is becoming increasingly recognized in biodiversity conservation debates. Direct involvement of this sector was still incipient in the early 2010s. Early gray literature had already begun advocating for the pivotal role that the financial sector could play in stimulating biodiversity conservation (e.g. Reference Huwyler, Käppeli, Serafimova, Swanson and TobinHuwyler et. al., 2014; IUCN, 2012), but estimates of the contribution by such instruments were still absent from key biodiversity finance publications (e.g. Reference Parker, Cranford, Oakes and LeggettParker et al., 2012). Fast-forward a decade and the financial sector becomes increasingly important for its potential to “unlock” private capital for biodiversity conservation (UNDP, 2020). According to Reference Deutz, Heal and NiuDeutz et al. (2020), for example, green financial products like green bonds, green loans, equity funds and others account for US$3.8–6.3 billion (Table 6.1; see also Reference Tobin-de la Puente and MitchellTobin-de la Puente and Mitchell, 2021). Green (or blue) bonds, of which biodiversity is a small share of the total green bonds market, offer the possibility of raising financial resources for green development projects and natural assets (e.g. marine protected areas and sustainable fisheries management in Seychelles) in exchange for a return to the investor after the contract period ends (Reference Tobin-de la Puente and MitchellTobin-de la Puente and Mitchell, 2021). We distinguish between these biodiversity-related green financial products and other approaches that redirect existing investment flows without a clear link to biodiversity, such as “divesting,” environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria, positive and negative screening, or other norms and standards that guide investment portfolios away from unsustainable practices and sectors (e.g. the oil industry) and toward sustainable ones (Reference Deutz, Heal and NiuDeutz et al., 2020).

Despite myriad differences, most gray literature produced in recent years indicates that the overarching purpose of these innovative financial instruments is to redirect socioeconomic practices through value or price signals in a way that benefits biodiversity conservation. The UNDP (2018: 6) states that biodiversity finance “is about leveraging and effectively managing economic incentives, policies, and capital to achieve the long-term well-being of nature and our society” (see also Reference Tobin-de la Puente and MitchellTobin-de la Puente and Mitchell, 2021). Alternatively, Reference DasguptaDasgupta (2021) suggests that “finance is an enabling asset that facilitates investments in capital assets [… and …] plays a role in determining both the stock of natural capital and the extent of human demands on the biosphere” (p. 467). This means that a core function of finance is to “confer value to the three classes of capital goods [produced capital, human capital, natural capital] by facilitating their use” (p. 325). Moreover, Dasgupta argues that “the value of biodiversity is embedded in the accounting prices of natural capital” (p. 43). These conceptualizations suggest that the contribution of finance to biodiversity conservation is to value or price natural capital. This is the case even in the financial sector, where biodiversity loss may be viewed as a calculable material risk in terms of physical flows (Reference DempseyDempsey, 2016), corporate reputation or broader impacts (e.g. Reference Deutz, Heal and NiuDeutz et al., 2020; DNP and PBL, 2020; see also Section 6.3.3). We therefore argue that the view of “nature-as-natural-capital” (Reference SullivanSullivan, 2018) forms the foundation for most innovative biodiversity finance mechanisms and, therefore, the critiques presented in this chapter are directly targeted at this view.

6.2.2 Principal Challenges for “Unlocking” Biodiversity Finance

Much biodiversity finance literature often proceeds from a compelling argument that, on the one hand, biodiversity conservation is economically important as many sectors rely on it, but, on the other hand, effective implementation of biodiversity conservation is costlier than is currently provided by financial instruments. The implementation of the CBD Strategic Plan for Biodiversity (2011–2020), for example, would incur annual costs of US$150–440 billion (UNDP, 2018). More recently, Reference Deutz, Heal and NiuDeutz et al. (2020) have reported an annual funding need of US$722–967 billion by 2030 for the sustainable management of protected areas, landscapes and seascapes, and urban environments (see also Reference Tobin-de la Puente and MitchellTobin-de la Puente and Mitchell, 2021). Such estimates have been used as the basis for estimating what is called the “funding gap.”

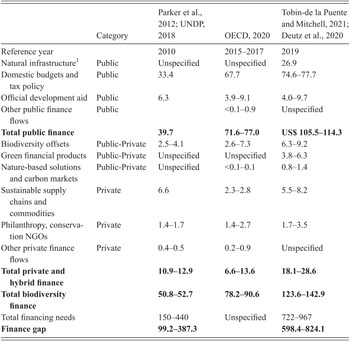

Many studies that estimate the funding gap compare the funding needs discussed above with the financial resources spent on biodiversity conservation (see Table 6.1). Although an accurate comparison of these results needs to account for differences in definitions, methodologies, assumptions and epistemologies, they illustrate the general trends over time in emphasizing the funding gap. At the global level, for example, Reference Parker, Cranford, Oakes and LeggettParker et al. (2012) have estimated biodiversity finance resources to be US$50.8–52.7 billion in 2010, while Reference Deutz, Heal and NiuDeutz et al. (2020) estimated this to be US$123.6–142.9 billion in 2019. More important than the apparent growth of available biodiversity finance over time, both studies report a funding gap of US$99.2–387.3 billion and US$598.4–824.1 billion, respectively. This funding gap problem plays out at lower levels of governance as well, particularly with respect to protected areas. The European Union Natura 2000 network of protected areas, for example, requires a total investment of €5.8 billion per year for its maintenance and ecological improvement (Reference Kettunen, Torkler and RaymentKettunen et al., 2014), but the EU’s advance budgetary allocation between 2007 and 2013 was only €0.6–1.2 billion per year (Reference Kettunen, Baldock and GantiolerKettunen et al., 2011). Likewise, lion conservation in protected areas in Africa receives US$0.4 billion annually despite indicating a need for US$1.2–2.4 billion (Reference Lindsey, Miller and PetraccaLindsey et al., 2018), while the Brazilian protected areas had a funding deficit of nearly US$360 million for their management costs in 2016 (Reference Silva, Dias, Cunha and CunhaSilva et al., 2021). Notwithstanding the estimate variation or the scale of governance, the central argument remains the same: finance needs upscaling to address the funding gap.

Table 6.1 Overview of global biodiversity finance sources and needs. Amounts are in billion US$ (categories are based on Reference Deutz, Heal and NiuDeutz et al., 2020)

| Category | Reference Parker, Cranford, Oakes and LeggettParker et al., 2012; UNDP, 2018 | OECD, 2020 | Reference Tobin-de la Puente and MitchellTobin-de la Puente and Mitchell, 2021; Reference Deutz, Heal and NiuDeutz et al., 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference year | 2010 | 2015–2017 | 2019 | |

| Natural infrastructure1 | Public | Unspecified | Unspecified | 26.9 |

| Domestic budgets and tax policy | Public | 33.4 | 67.7 | 74.6–77.7 |

| Official development aid | Public | 6.3 | 3.9–9.1 | 4.0–9.7 |

| Other public finance flows | Public | <0.1–0.9 | Unspecified | |

| Total public finance | 39.7 | 71.6–77.0 | US$ 105.5–114.3 | |

| Biodiversity offsets | Public-Private | 2.5–4.1 | 2.6–7.3 | 6.3–9.2 |

| Green financial products | Public-Private | Unspecified | Unspecified | 3.8–6.3 |

| Nature-based solutions and carbon markets | Public-Private | Unspecified | <0.1–0.1 | 0.8–1.4 |

| Sustainable supply chains and commodities | Private | 6.6 | 2.3–2.8 | 5.5–8.2 |

| Philanthropy, conservation NGOs | Private | 1.4–1.7 | 1.4–2.7 | 1.7–3.5 |

| Other private finance flows | Private | 0.4–0.5 | 0.2–0.9 | Unspecified |

| Total private and hybrid finance | 10.9–12.9 | 6.6–13.6 | 18.1–28.6 | |

| Total biodiversity finance | 50.8–52.7 | 78.2–90.6 | 123.6–142.9 | |

| Total financing needs | 150–440 | Unspecified | 722–967 | |

| Finance gap | 99.2–387.3 | 598.4–824.1 |

1 According to Reference Deutz, Heal and NiuDeutz et al. (2020: 121), natural infrastructure involves “networks of land and water bodies that provide ecosystem services for human populations, which produce similar outcomes to implemented gray infrastructure.”

In addition to the identification of a funding gap, the studies reported here identify another feature of biodiversity finance, which is that the bulk of this finance still comes from public sources. The comparisons in Table 6.1 demonstrate this clearly for global biodiversity finance, where contributions from public sources currently vary between 73.8 percent and 92.5 percent (percentages were based on the estimates reported by Reference Deutz, Heal and NiuDeutz et al., 2020). Moreover, public finance for biodiversity conservation competes with other important goals. For instance, international funding through conservation NGOs is less than 1 percent of official development assistance (ODA) to Africa (Reference Brockington and ScholfieldBrockington and Scholfield, 2010). While public finance alone is unlikely to be sufficient for closing the funding gap (Reference Huwyler, Käppeli, Serafimova, Swanson and TobinHuwyler et. al., 2014), private finance has been slow in directing financial resources to biodiversity conservation. Between 2004 and 2015, most private investments were made in (more) sustainable food and fiber production (US$6.5 billion), so outside the innovative financial instruments that we are focusing on here. Investments in habitat conservation (US$1.3 billion) and water quality and quantity (US$0.4 billion) were much lower, although the latter was still backed by substantial public investments (US$21.5 billion between 2009 and 2015) (Reference HamrickHamrick, 2016).

To address this gap, most studies argue for “unlocking” private finance (e.g. UNDP, 2020). In this respect, many innovative financial mechanisms are targeted at enhancing private sector funding, increasing involvement of private capital and implementing market-based instruments (Reference Anyango-van ZwietenAnyango-van-Zwieten, 2021; Reference Clark, Reed and SunderlandClark et al., 2018; EC, 2011; Reference Gutman and DavidsonGutman and Davidson, 2007; Reference MilesMiles, 2005; Reference PirardPirard, 2012; Reference Thiele and GerberThiele and Gerber, 2017; UNDP, 2020). Similarly, stakeholders have started to build the “business case” for biodiversity conservation to attract private sector involvement by pointing out cost reduction, return-on-investment and risk mitigation motives, among others (IUCN, 2012; OECD, 2019). The UNDP and the European Commission, for example, launched the Biodiversity Finance Initiative (BIOFIN) in 2012 to seek new methodologies for “optimal” and “evidence-based” biodiversity finance plans and solutions (UNDP, 2018; 2020). The European Commission also launched its own EU Business @ Biodiversity Platform (B@B) in 2007. Arguably, the most promoted instruments for leveraging financial resources are deemed to be market-based, meaning that “biodiversity conservation [is] financed through and undertaken with the aim of generating profitable returns for their investors” (Reference Dempsey and SuarezDempsey and Suarez, 2016: 654). At the same time, such for-profit instruments still face challenges, including lack of scale (often the projects are too small), lack of financial track record, lack of so-called angel investors at the risky early-stage phase and poor project design without “investable, simple and understandable conservation asset classes” (Reference Anyango-van ZwietenAnyango-van Zwieten, 2020; Reference Huwyler, Käppeli, Serafimova, Swanson and TobinHuwyler et al., 2014: 27). The task ahead, these publications assert, is to address these challenges and scale up private finance to close the funding gap.

6.2.3 Toward a Critical Assessment of Biodiversity Finance

Unlocking private finance has a broader and more important role in mainstreaming biodiversity in all socioeconomic sectors by closing a “different gap” between the current state-of-affairs and a transformative change thereof. In practice, this requires catalyzing more structural transformations of economic and financial systems because “all economic sectors need to contribute to conserving biodiversity and ecosystems and their sustainable management” (CBD, 2020b; Reference Díaz, Settele and BrondízioDíaz et. al., 2019; UNDP, 2020: 12). In this context, the CBD’s Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework was, at the time of writing this chapter, expected to incite new and additional financial resources, stimulate corporate sector accountability and establish more rigorous safeguards for private sector engagement (Reference Ching, Lin and BeirutChing and Lin, 2019). Greening finance, then, involves a broader transition of biodiversity governance into a “whole-of-society approach” (Reference Van Oorschot, Kok and Van TulderVan Oorschot et al., 2020) where existing biodiversity finance instruments catalyze this transition rather than merely addressing the “funding gap” for biodiversity conservation. The establishment of the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) in 2017, for example, aims to “mobilize mainstream finance to support the transition toward a sustainable economy” (NGFS, 2020), promote the adoption of sustainable and responsible investment principles and address the environmental and societal impacts of the policy portfolios of central banks across the world (NGFS, 2019; see Section 6.3.3. for an example from Brazil). At the same time, this approach still faces substantial challenges, such as reshaping entrenched investment norms, risk definitions and investment practices in the financial sector (Reference Crona, Eriksson and LerpoldCrona et al., 2021).

Recognizing that the whole-of-society approach advocated by the Post-2020 Framework was still in the initial stages of development, the critical assessment of biodiversity finance presented in the remainder of this chapter focuses on the innovative financial instruments that aim to catalyze this approach. For purposes of clarity, we understand such instruments to encompass not only “tradable permits,” “reverse auctions” and “coasean-type agreements,” in Reference PirardPirard´s (2012) lexicon, but also new financial products like nature derivatives and weather insurances that mitigate the material risks of biodiversity loss (Reference Anyango-van ZwietenAnyango-van Zwieten, 2021). Our analysis thereby excludes price signals (e.g. US$274–542 of harmful subsidies, see Reference Deutz, Heal and NiuDeutz et al., 2020), although we acknowledge their importance within the broader context of biodiversity finance. Furthermore, we acknowledge the intense controversies around the extent to which instruments like biodiversity offsetting, PES or nature derivatives are market-based, economic or financial, but at the same time argue that this variety of instruments share common ontological and epistemological foundations. Focusing on innovative financial instruments is therefore our attempt to capture this common ground.

6.3 Deconstructing Biodiversity Finance for Transformative Change

This section addresses the four central questions that are in line with the core purposes of this book, as presented in the introduction. It also critically discusses innovative financial instruments in light of the five dimensions of transformative governance (i.e. integrative, inclusive, adaptive, transdisciplinary and anticipatory; see Chapter 1 for full definitions). Based on this framework, we first deconstruct discussions in the literature and then summarize each subsection with our critique.

6.3.1 How Comprehensive Is “Financeable” Biodiversity?

All innovative finance instruments have a material basis for making transactions possible. Many instruments tie financial resources to objects like credits, rights, quotas, offsets and permits that in many ways give access to natural capital (e.g. Reference Koh, Hahn and BoonstraKoh et al., 2019; Reference May, Bernasconi, Wunder and LubowskiMay et al., 2015; Reference Van der Hoff and Rajãovan der Hoff and Rajão, 2020). This access to natural capital should be understood as its utilization either as a source of natural resources (e.g. permits to extract fish from Antarctic waters) or as a sink for the wasteful byproducts of economic activity (e.g. credits for greenhouse gas emissions or Tradable Development Rights). Nonmarket instruments like results-based payments require a clear definition of the “results” or “performance” (e.g. emissions reductions) in relation to conservation objectives (Reference Van der Hoff, Rajão and LeroyVan der Hoff et al., 2019). In the financial sector, we encounter bonds, derivatives, securities, swaps, futures and insurances, among others, that facilitate investments in conservation (e.g. green bonds) or hedge against the risk of biodiversity loss (e.g. weather derivatives) (Reference BrackingBracking, 2012; Reference Little, Parslow and FayLittle et al., 2014; Reference Ouma, Johnson and BiggerOuma et al., 2018; Reference SullivanSullivan, 2018). For purposes of argumentation, we will refer to this material basis as “financeable objects.”

Following Reference Callon and MuniesaCallon and Muniesa (2005: 1233–1234), these financeable objects are the outcome of processes of “objectification” and “singularization” of (parts of) biodiversity and by which financial transactions become possible. Objectification emphasizes the materiality of this object, which means that they have tangible and objective properties that characterize them as a “good” (e.g. rubber), “service” (e.g. pollination) or more abstract (financial) products like derivatives. These objects become financeable through “singularization,” which “consists in a gradual definition of the properties of the product [or object], shaped in such a way that it can enter into the consumer’s world and become attached to it.” This means that the object can be assigned a value (see below) and appropriated by others. Take biodiversity offsets as an example (Reference Koh, Hahn and BoonstraKoh et al., 2019): In most schemes, the biodiversity in areas with natural vegetation is assessed based on indicators of habitat type, species, threat level, richness, rarity, diversity and connectivity, among others. These indicators are then used to classify these areas and establish biodiversity offset credits. The number of credit types range from only one (e.g. the Rio Tinto QIT Madagascar Minerals [RTQMM] offsets) or two (e.g. species and ecosystem credits in the New South Wales Biodiversity Conservation Trust), to up to eight (wetland mitigation banking in the United States). These credits are the financeable objects of biodiversity offsetting that can be acquired by developers to compensate for their impact on nature. Even in cases where such exchange does not take place (say, results-based payments for REDD+), one may argue that financing parties may obtain other gains from the “investment,” like satisfying domestic political constituencies (e.g. Reference AngelsenAngelsen [2017] calls this “political offsets”).

The translation of biodiversity into “financeable objects” poses several challenges to transformative biodiversity governance because it denotes a very managerial approach to nature conservation. Reference SullivanSullivan (2017, Reference Sullivan2018) calls this approach a “nature-as-natural-capital” view that is enacted through processes of commensuration (i.e. enhancing the comparability of nature), aggregation (i.e. a preference of total quantities over qualitative specificity) and capitalization (i.e. producing natural assets or, in this chapter, financeable nature). It embodies an ontological understanding of nature as mechanically composed of “gears and bolts” (Reference WorsterWorster, 1994) or “rivets” (Reference DempseyDempsey, 2016) that, epistemologically, can be fully known and, more importantly, used and managed to meet human needs and preferences, thereby representing instrumental values (see Chapter 2). Although this ontological and epistemological view is enormously powerful (think about the ecosystem services concept), the downside is that it excludes a vast array of alternative ways of knowing and interacting with nature, which precludes possibilities for transdisciplinary governance. Although ecologists and economists have been working closely together on nature conservation issues since the 1980s, Reference DempseyDempsey (2016) argues that this collaboration leans more toward economic than ecological pragmatics. Many studies have lamented the ecologically reductionist conceptualizations of nature hidden in the “nature commodification” of PES schemes (e.g. Reference Kosoy and CorberaKosoy and Corbera, 2010; Reference WilsonWilson, 2013), the metrics of biodiversity offsetting (Reference Marshall, Wintle, Southwell and KujalaMarshall et al., 2020) and the methodology of biodiversity valuation (Reference Farnsworth, Adenuga and de GrootFarnsworth et al., 2015). Finally, such objects exclude alternative sources of intrinsic, spiritual and other forms of meaning (Reference LabandLaband, 2013) in order to only reflect the measurable and delineable properties of the financeable object.

Another problem with financeable objects is that they need to be rigid in order to become operational, which allows little space for adaptation. The market for Tradable Development Rights (TDRs) in Brazil, also called Environmental Reserve Quota (or Cota de Reserva Ambiental – CRA), is a case in point. Rural landowners in Brazil are obliged by law to conserve native vegetation on their properties (up to 80 percent in the Amazon), demanding restoration in case of a deficit and allowing deforestation in case of surplus. The CRA market offers an alternative option: Landowners with a surplus may issue and sell CRAs rather than deforest, while those with a deficit may acquire CRAs instead of restoring native vegetation (Reference May, Bernasconi, Wunder and LubowskiMay et al., 2015). For over two decades of political development, this market has been subject to substantial expansions, one of which involves the geographical boundaries of trade (i.e. from trade within watershed to trade within biome and across states) (Reference Van der Hoff and Rajãovan der Hoff and Rajão, 2020). These expanded trade boundaries, the outcome of political pressure from the rural caucus, were challenged by a supreme court ruling that demanded a proof of similar “ecological identity” of properties engaged in a CRA exchange. Although this ruling is considered positive from a biodiversity conservation standpoint, it also poses significant challenges to ecologists to establish a workable indicator and thus slows down the operationalization of the market (Reference Rajão, Del Giudice, van der Hoff and de CarvalhoRajão et al., 2021).

Our critical assessment of the nature of financeable objects denotes an argument against the role of finance in transformative biodiversity governance. Such objects necessarily build on an economic conceptualization of nature that emphasizes its measurability, its manageability, its anthropocentrism and its instrumentalism. More importantly, this economism can potentially drown out other approaches to nature conservation, such as arguments for conserving pristine nature (Reference DempseyDempsey, 2016) or a harmonious relationship with nature that embeds local livelihoods (e.g. buen vivir, see Chapters 2, 8 and 9), which attests to poor inclusive governance. The difficulty (if not impossibility) of other ontologies and epistemologies to shape this financeable object also preclude the manifestation of a truly transdisciplinary governance. Moreover, this constrained transdisciplinarity limits possibilities for adaptive governance, as the CRA trade in Brazil exemplifies.

6.3.2 Whose Values Does “Financeable” Biodiversity Represent (and Whose Are Excluded)?

The process of singularization does not stop at defining the financeable object. According to Reference Callon and MuniesaCallon and Muniesa (2005: 1233), “the thing that ‘holds together’ [the financeable object] is a good if and only if its properties represent a value for the buyer.” Applied to biodiversity finance, it suggests that financing biodiversity conservation occurs only if the destination (i.e. the financeable object) of these resources is considered to be valuable. Biodiversity indicators by themselves do not immediately prompt a mobilization of financial resources, but once they are packaged in, say, development rights or biodiversity offsets, they become valuable to potential financers. This value perception is fundamental. Results-based payments to the Brazilian Amazon Fund, for example, were based on demonstrated deforestation reductions in the Amazon region,Footnote 1 but its financers (mainly the Norwegian government) had slightly different criteria for “valuable” results than Brazil. Brazil held the belief that it deserved to be rewarded for past achievements (deforestation fell from nearly 30,000 km2 in 2004 to less than 5,000 km2 in 2012) and therefore maintained that annual results accumulate over time. By contrast, financers retained the preference for financing only the most recent results (e.g. Norway’s payments in 2017 referred to results obtained in 2016). As deforestation rates went up in the 2010s, annual “results” significantly declined and financers were compelled to stop payments due to lack of “valuable results” (Reference Van der Hoff, Rajão and Leroyvan der Hoff et al., 2018). In other words, the financeable object – be it an offset, a bond or a permit – needs to be perceived as valuable by the financer, otherwise financing is unlikely to take place.

Innovative financial instruments communicate the value to financiers in monetary terms. Section 6.2 already noted Reference DasguptaDasgupta’s (2021) conceptualization of biodiversity finance as a conveyor of biodiversity value through natural capital accounting prices. Economists claim that the previous inexistence of such prices was (and still is) the underlying problem of biodiversity loss. Reference Pearce, Markandya and BarbierPearce, Markandya and Barbier (1989: 5), for example, argued that when “something is provided at a zero price, more of it will be demanded than if there was a positive price.” For landowners in the Brazilian Amazon, for example, standing forests have little value and legislation obliging them to conserve forests is perceived as an obstruction to land development (e.g. agriculture) and thus incurs high opportunity costs (Reference Metzger, Bustamante and FerreiraMetzger et al., 2019; Reference Stickler, Nepstad, Azevedo and McGrathStickler et al., 2013). Putting a price on these forests could change these perceptions. One of the main ideas behind the CRA market in Brazil, for example, was to allow landowners with vegetation beyond legal requirements to sell quota to those with deficits (in the final regularization, this was expanded to include PES as well) instead of legally clearing the land for, say, agricultural development (Reference Van der Hoff and Rajãovan der Hoff and Rajão, 2020; see also Section 6.2.1). Other finance instruments raise the costs of development projects (Reference Koh, Hahn and BoonstraKoh et al., 2019) or risks related to biodiversity loss (Reference Little, Parslow and FayLittle et al., 2014). The value of biodiversity reflected in these prices transposes the idea that using (or destroying) nature is no longer for free, but involves foregone opportunities or additional costs.

Prices, however, muddle the value of biodiversity in two ways. Firstly, the anthropocentrism implied in the type of biodiversity knowledge that forms the foundation of financeable objects (see Section 6.3.1), to which economists assign a “use value” and, subsequently, an exchange value. The ecosystem services concept is a notable reflection of these use values of biodiversity and there is currently a wealth of different tools to inform decision-makers (Reference Grêt-Regamey, Sirén, Brunner and WeibelGrêt-Regamey et al., 2017; Reference Martinez-Harms, Bryan and BalvaneraMartinez-Harms et al., 2015). According to critical scholars, however, this use value of biodiversity overemphasizes those aspects of nature that instrumentally benefit humankind, but downplays, excludes or even fails to perceive others that may be otherwise valuable. Economists have come a long way in identifying future use or non-use values (e.g. option, bequest and existence values; [see Reference Tietenberg and lewisTietenberg and Lewis, 2018]), but other uses of ecosystems that reflect cultural, aesthetic, spiritual and intrinsic values are extremely hard to express numerically (Reference Small, Munday and DuranceSmall et al., 2017; see also Chapters 2, 8 and 9). Recognition of such value pluralism is not new, but has been advocated in predominantly noneconomist disciplines like anthropology (e.g. Reference GraeberGraeber, 2001) and environmental ethics (e.g. Reference HourdequinHourdequin, 2015) and has become an important theme in the critical discipline of ecological economics (Reference SpashSpash, 2017). Even Reference Costanza, de Groot and BraatCostanza et al. (2017), who famously and controversially valued the world’s ecosystem services at US$16–54 trillion per year, acknowledge that the economic definition of value is too narrow as individuals are unable to appreciate or even perceive how some ecosystem services are valuable to them. The prevalence of use values in biodiversity finance (see Reference DempseyDempsey, 2016) is a far cry from this value pluralism, which attests to its constrained ability to promote transdisciplinary governance.

The second layer of problems with the prices of financeable objects refers to the repercussions of translating nature into use values and exchange values. Firstly, prices exacerbate the commensurability of inherently distinct dimensions of nature that are reflected in nonmonetary numeric assessments of biodiversity (Reference SullivanSullivan, 2017). Monetary valuation reduces “the problem of scarcity [of nature] into a problem of scarcity of capital, considered as an abstract category expressible in homogeneous monetary units” (Reference NaredoNaredo, 2003: 250). Commensurate nature can thus be considered on a par with economically or technologically alternative actions. For instance, Brazilian landowners can choose their preferred course of action depending on their situation. Those with conservation deficits can choose between restoring degraded land or acquiring CRA, while those with vegetation beyond legal requirements can choose to legally clear it or sell CRA credits (Reference May, Bernasconi, Wunder and LubowskiMay et al., 2015). Secondly, an emphasis on prices widens the gap between what innovative financial instruments define as valuable and the local perceptions and values of peoples on the ground. For example, the Brazilian Amazon Fund disburses financial resources to a myriad of projects that contribute to regional sustainability despite unclear contributions to emissions reductions (Reference Correa, van der Hoff and RajãoCorrea et al., 2019), which become prejudiced as Brazil’s basis for receiving donations is eroded (see above; Reference Van der Hoff, Rajão and LeroyVan der Hoff et al., 2018). Conversely, the introduction of monetary values for biodiversity through, say, PES initiatives may risk “crowding out” the intrinsic motivations of local people to conserve nature (Reference Akers and YasuéAkers and Yasué, 2019). Nonmonetary values thus become sidelined, while “valuable” development and conservation projects prevail (see also Reference Laschefski, Zhouri, Puzone and MiguelLaschefski and Zhouri, 2019; Reference Villén-Pérez, Mendes, Nóbrega, Gomes Córtes and De MarcoVillén-Pérez et al., 2018). These problems pose significant challenges for integrative and inclusive governance.

6.3.3 How Does Biodiversity Finance Deal with Uncertainty?

There are many similarities between the “nature-as-natural-capital” view and what Reference DempseyDempsey (2016) calls the “biodiversity loss as material risk” perspective. The central tenet is that biodiversity loss is a financial and economic risk that has (or will have) an impact on the bottom line. This is a fast-developing awareness: in 2010 biodiversity loss featured inconspicuously as “less prominent” in the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) Global Risks Landscape report but dominated its global risks reports in 2021 (WEF, 2010; 2021). Two key responses to this growing awareness are that biodiversity loss needs to be managed as a business risk as well as treated as an opportunity for profit-making. The management and commodification of biodiversity risks have translated into new financial products including green bonds, rainforest bonds and climate bonds, biodiversity and nature derivatives, weather derivatives, catastrophe bonds and commodity index funds (Reference Ouma, Johnson and BiggerOuma et al., 2018; Reference SullivanSullivan, 2018). This calculative management of biodiversity risks is different from a precautionary approach that acknowledges the difficulty or impossibility of such calculations, preferring not to seek out the threshold of the “critical rivet” (Paul and Anne Ehrlich, cited in Reference DempseyDempsey, 2016). The agricultural sector, for example, may insure itself against unpredictable climate patterns like low precipitation, severe drought and destructive storms (e.g. Reference Souza and AssunçãoSouza and Assunção, 2020), but cannot account for the full complexity of impending ecosystem “tipping points” to irreversibly transition to unfavorable landscapes (e.g. Reference Lovejoy and NobreLovejoy and Nobre, 2019). The calculative, managerial approach to uncertainty adopted by the financial sector, therefore, does not correspond with the precautionary definition of anticipatory governance.

In terms of inclusive and transdisciplinary governance, risk management instruments such as biodiversity derivatives, bonds and futures are designed to give preeminence to financial actors, their expertise and knowledge (Reference BrackingBracking, 2012). Though “spark[ing] the interest and imagination of investors” (Reference Brockington, Büscher, Dressler and FletcherBrockington, 2014: 123), these instruments are severed from actual conservation (Reference BüscherBüscher, 2013). Take regional precipitation patterns as an example. Reference Strand, Soares-Filho and CostaStrand et al. (2018) estimate that a decreased capacity of Amazonian forests to provide this climate regulation service reduces rents and productivity for the soybean, beef and hydroelectricity sectors, incurring an average cost of US$1.81, US$5.43 and US$0.32 per hectare per year, respectively. Although understanding how these sectors negatively impact their own business through land clearing has the potential to raise awareness about the “real costs” of biodiversity loss, the challenge is to make these costs felt at the individual company level (see Reference DempseyDempsey, 2016). Reference Rode, Pinzon and StabileRode et al. (2019: 7) found that the identification and valuation of ecosystem services does not readily attract investments, but “require[s] specific stakeholder processes and verification procedures” for this information to become part of these stakeholders’ worlds (see also Reference Callon and MuniesaCallon and Muniesa, 2005). Using the concepts of Reference SullivanSullivan (2018), investable nature requires not only its understanding as capital (qualification) in numeric or monetary terms (quantification), but also its subsequent “fabrication” into a “leverageable” asset class (materialization). Some risks become financeable objects (e.g. bonds, futures and other derivatives), while others become quantitative indicators that inform decision-making.

Not all uncertainties can readily become “calculated” risks and require substantial initial investment to catalyze private sector interest. In this respect, according to Reference ChristiansenChristiansen (2021: 96), blended finance emphasizes the role of public finance “to pursue so-called ‘crowding-in’ of investments by either lowering [real or perceived] risks or increasing [anticipated] returns for private investments,” especially during the initial “seed-stages” of conservation projects. Blended finance is the use of public and philanthropic funds to leverage private finance. Evaluating the Unlocking Forest Finance (UFF) project in Brazil and Peru, Reference Rode, Pinzon and StabileRode et al. (2019: 7) emphasize that investor expectations and requirements do not “reflect the realities of the current scale, return and risk structures of sustainable landscape investments on the ground.” These challenges, they argue, could be mitigated through the mobilization of blended finance that includes philanthropy to ensure direct conservation benefits or impact monitoring, NGOs to offer technical support for implementation, and governments to reduce risk of investment. Blended finance, then, may offer a “proof of concept” to build investor confidence in making sustainable investments (Reference ChristiansenChristiansen, 2021). It is in these initial stages that learning – or adaptive governance – is most likely to take place (Reference Rode, Pinzon and StabileRode et al., 2019). At the same time, the investor requirements related to financial returns and risk exposure tend to drown out other criteria for assembling the investment portfolio, at least in the case of sustainable agriculture. In catering to these requirements, blended finance adheres to the predominant investor milieu and thereby risks relinquishing aspects of inclusive (not all projects are financed) and transdisciplinary (not all criteria are weighed equally) governance.

In practice, businesses, farmers, investors and corporations perceive biodiversity losses as reputational or regulatory risks (Reference DempseyDempsey, 2016). With respect to the latter, for example, introducing sustainability performance as a condition for granting rural credit has great potential to prompt the immediate behavioral change of rural producers (e.g. Reference Rode, Pinzon and StabileRode et al., 2019). In Brazil, the introduction of such sustainability criteria in 2008 by the Central Bank has had significant repercussions for its agricultural sector and contributed to the declining deforestation rates in the Brazilian Amazon at the time (Reference Assunção, Gandour, Rocha and RochaAssunção et al., 2019). In this case, biodiversity loss comes at a price: restricted access to finance. This example underscores that consideration of biodiversity loss as a material risk by private sector organizations still requires strong encouragement through blended finance initiatives and strong governmental institutions. Moreover, it signals that economic efficiency continues to prevail even in the “triple bottom-line” over environmental protection and social equality (Reference ChristiansenChristiansen, 2021). Despite its contribution to internalizing externalities, the “biodiversity loss as material risk” perspective still denotes a limited contribution to transformative governance.

6.3.4 How Profound Are the Transformative Changes Fostered by Biodiversity Finance?

Innovative financing instruments for biodiversity conservation commonly involve multiactor networks. Firstly, they establish connections between the “users” and “providers” of biodiversity. Examples abound: the CRA market links landowners with vegetation beyond legal requirements to landowners with legal deficits (Reference May, Bernasconi, Wunder and LubowskiMay et al., 2015; Reference Van der Hoff and Rajãovan der Hoff and Rajão, 2020); biodiversity offsetting ties potentially harmful development projects to conservation efforts (Reference Koh, Hahn and BoonstraKoh et al., 2019); responsible investors can buy green bonds from organizations or governments that develop sustainable economic activities or strengthen conservation (for examples, see Reference Deutz, Heal and NiuDeutz et al., 2020); and polluting countries make results-based payments to forested countries (Reference AngelsenAngelsen, 2017; Reference Van der Hoff, Rajão and Leroyvan der Hoff et al., 2018). Secondly, the actor networks of innovative finance instruments often extend beyond “users” and “providers.” Reference Koh, Hahn and BoonstraKoh et al. (2019) make this abundantly clear with respect to biodiversity offsetting. In Germany, for example, municipal governments are responsible for matching the supply side (i.e. buying or leasing land for conservation) and the demand side (i.e. reviewing assessments of biodiversity losses at impact sites) of development impact compensation. Alternatively, wetland mitigation banking in the United States is a mandatory market arrangement under the Clean Water Act (1980) that potentially harmful development projects must adhere to. Reference Koh, Hahn and BoonstraKoh et al. (2019) also argue that many biodiversity offsetting schemes include conservation NGOs (e.g. England, South Africa, Madagascar), consultancies (nearly all schemes evaluated), trust funds (e.g. Australia), and brokers (England, Australia, United States). Reference Barton, Benavides and Chacon-CascanteBarton et al. (2017) have taken this argument a step further by describing Costa Rica’s PES program as a policy mix that combines different actor types in different roles following specific rules (“rules-in-use”) in order to attain conservation objectives (see also Reference Ring, Barton, Martínez-Alier and MuradianRing and Barton, 2015). These examples suggest a potential of some biodiversity finance instruments to foster coordination among different actors toward biodiversity conservation objectives.

Some finance instruments also link conservation actions across governance levels. In the case of the Amazon Fund, the financial resources are passed on by the recipient (i.e. Amazon Fund) to projects that correspond with core categories of Brazilian environmental policies, most notably (1) monitoring and control, (2) land tenure and regularization and (3) sustainable economic activities. More importantly, the Amazon Fund, mediated by the Brazilian Development Bank, acts more like a mediator than a recipient. The transaction of financial resources from investors (e.g. the Norwegian government) to the Amazon Fund is not the final objective, since these resources are passed on to a plethora of other stakeholders across Brazil that comply with specific access requirements (e.g. project documentation). For example, this allowed the Amazon Fund to strengthen and empower protected areas with an investment of over US$66 million (Reference Correa, van der Hoff and RajãoCorrea et al., 2019; Reference Van der Hoff, Rajão and LeroyVan der Hoff et al., 2018). Such an arrangement of transactions enacts what some REDD+ scholars have called a “nested approach,” where individual projects are embedded in broader national and international governance networks (Reference Angelsen, Streck, Peskett, Brown and LuttrellAngelsen et al., 2008). More recent efforts at integration aim to build an architecture for REDD+ transactions (ART) that demand upscaling efforts to national levels and subsuming lower-level performance (e.g. biome or states) within national accounting (see ART, 2021).

Despite the potential of innovative financial instruments to contribute to integrative governance through coordination (e.g. a “nested approach” to REDD+) and combination (e.g. PES policy mix) (see Chapter 1), some nuancing is appropriate here. Firstly, the very rules-in-use that enable such integration to take place also constrain the finance instruments that apply them. For instance, the Brazilian Amazon Fund distributes financial resources based on criteria that include organizational capacity to comply with its strict reporting demands, making it harder for finance to flow to smaller (but no less important) projects (Reference Correa, van der Hoff and RajãoCorrea et al., 2019; Reference Van der Hoff, Rajão and Leroyvan der Hoff et al., 2018). It must further be noted that these rules are politically negotiated. In Brazil’s CRA market, smallholders may supply credits that represent all vegetation on their properties (even when they have a legal deficit), while uncompensated properties located inside protected areas (already protected by law) may supply credits representative of their legal surpluses (Reference Van der Hoff and Rajãovan der Hoff and Rajão, 2020).Footnote 2 The degree to which biodiversity finance instruments are inclusive depends to a large extent on how these rules-in-use are defined.

Another limitation, closely related to the former, is that there are limits to the degree of integration that innovative finance instruments can foster. Outcomes of PES programs, for example, challenge the characterization as a policy mix (see above) evidenced by contextual factors that are unaccounted for and that (positively or negatively) affect their performance. The Costa Rican government actively portrays its PES program as a market instrument, whereas in practice the program has been accepted by recipient farmers as a recognition of their stewardship, more than the prospect of being rewarded, which enhances the likelihood of positive outcomes (Reference Chapman, Satterfield, Wittman and ChanChapman et al., 2020), and the PES program in Chiapas, Mexico, has faced substantial social conflict that threatens its continuity (Reference Corbera, Costedoat, Ezzine-de-Blas and Van HeckenCorbera et al., 2020). Mixed outcomes were also found for biodiversity offsets (Reference Bidaud, Schreckenberg and RabeharisonBidaud et al., 2017). Alternatively, deforestation rates in the Brazilian Amazon have been rising since 2012 despite increased disbursements from the Amazon Fund, which denotes that such instruments rarely operate in isolation and that conservation outcomes are just as much the result of the synergetic effects of factors like a hostile political climate (e.g. the Amazon Fund was extinguished in 2019) and broader commodity market developments. These examples illustrate that the outcomes of innovative financial instruments are affected by contextual factors that cannot be fully accounted for, which suggests that they themselves need to be integrated into a broader policy or governance mix.

Finally, and most importantly, biodiversity finance does not challenge the foundations of the capitalist system that is often argued to reinforce many of the known drivers of biodiversity loss (Reference Díaz, Settele and BrondízioDíaz et al., 2019), because it reproduces the existing (skewed) power relations that this system builds on. The adoption of the CRA market in Brazil, for example, does not challenge the notion that, by federal constitution, private land needs to be used “productively” and could not prevent the “flexibilization” of nature conservation requirements via a new Forest Code in 2012 that mostly benefits dominant agribusiness interests (Reference Rajão, Del Giudice, van der Hoff and de CarvalhoRajão et al., 2021; Reference Van der Hoff and RajãoVan der Hoff and Rajão, 2020). In addition, blended finance exacerbates global economic imbalances by giving preferential treatment to donors’ own private sector firms and focusing on middle income countries (Reference PereiraPereira, 2017). These instruments typically aim to influence decision-making processes at the individual level (for example institutional investors) but do not challenge systemic or structural drivers of biodiversity loss. These perennial issues jeopardize the inclusive dimension of transformative governance. By insufficiently challenging the indirect drivers of biodiversity loss, moreover, they cannot be considered transformative as they do not correspond with the definition of transformative governance in Chapter 1, which states that addressing these indirect drivers is fundamental.

6.4 Conclusions and Ways Forward

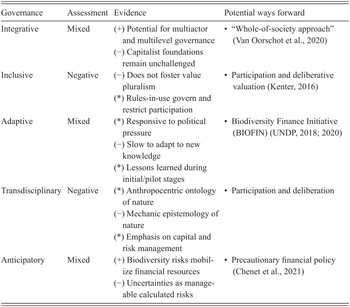

The challenges for innovative financial instruments to support transformative biodiversity governance are substantial as they pose multiple limitations for transformative governance both in terms of its five dimensions and with respect to addressing the drivers of biodiversity loss. Starting with the dimensions (see Table 6.2), our analysis shows that while these instruments may foster integrative governance to some extent (see Section 6.3.4), they exacerbate the marginalization of local communities and values. In addition, the emphasis on financeable objects and monetary values promotes the biodiversity-as-natural-capital and biodiversity-loss-as-material-risk views that underpin the mobilization of financial resources. At the same time, these traits advance an ontological and epistemological understanding of biodiversity that is inherently narrow in terms of both its substance and its value, which undermines the inclusive and transdisciplinary dimensions of transformative governance. Other dimensions contain mixed considerations. With respect to adaptive governance, evidence in the reviewed literature indicates processes of learning taking place, although these mostly tend to occur in the initial stages of instrument development (see Section 6.3.3). In addition, the incorporation of biodiversity-related uncertainties into financial decisions, although in itself positive, follows a managerial and calculative approach that translates these into material risks. In terms of the five dimensions of transformative governance, therefore, innovative financial instruments must be approached cautiously and critically.

Table 6.2 Assessment summary for innovative financial instruments. Symbols refer to positive (+), negative (−) and mixed or neutral (*) assessments and reflect author interpretations

| Governance | Assessment | Evidence | Potential ways forward |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrative | Mixed | (+) Potential for multiactor and multilevel governance | •“Whole-of-society approach” (Reference Van Oorschot, Kok and Van TulderVan Oorschot et al., 2020) |

| (−) Capitalist foundations remain unchallenged | |||

| Inclusive | Negative | (−) Does not foster value pluralism | •Participation and deliberative valuation (Reference KenterKenter, 2016) |

| (*) Rules-in-use govern and restrict participation | |||

| Adaptive | Mixed | (*) Responsive to political pressure | •Biodiversity Finance Initiative (BIOFIN) (UNDP, 2018; 2020) |

| (−) Slow to adapt to new knowledge | |||

| (*) Lessons learned during initial/pilot stages | |||

| Transdisciplinary | Negative | (*) Anthropocentric ontology of nature | •Participation and deliberation |

| (−) Mechanic epistemology of nature | |||

| (*) Emphasis on capital and risk management | |||

| Anticipatory | Mixed | (+) Biodiversity risks mobilize financial resources | •Precautionary financial policy (Reference Chenet, Ryan-Collins and van LervenChenet et al., 2021) |

| (−) Uncertainties as manageable calculated risks |

Some scholars have pointed to interesting measures for moving toward transformative governance. Reference KenterKenter (2016) suggests that deliberative and participatory approaches to valuation could be an appropriate format for supplementing monetary approaches to valuing ecosystem services, which would improve the inclusive governance dimension. Participation and deliberation may also counterbalance the emphasis on anthropocentric, mechanistic and managerial approaches to nature conservation, building toward transdisciplinary governance. With respect to anticipatory governance, innovative financial instruments (and biodiversity finance in general) may consider what Reference Chenet, Ryan-Collins and van LervenChenet et al. (2021) refer to as “precautionary financial policy” to better deal with uncertainties that escape biodiversity risk assessments, thereby improving the anticipatory governance dimension. The limits to strengthening integrative governance through innovative financial instruments underscores the importance of developing a “whole-of-society approach” (Reference Van Oorschot, Kok and Van TulderVan Oorschot et al., 2020). For improvements in the adaptive governance dimension, one may look to the BIOFIN as a platform for learning and feedback (UNDP, 2018; 2020).

It is doubtful, however, that such developments can shape up innovative financial instruments to manifest the transformative governance envisioned in this book. As this chapter has made abundantly clear, the prevailing logics of innovative financial instruments often fall short of the five dimensions discussed above. One may even argue that their proper functioning depends on clear definitions of “financeable objects,” their monetary values and the rules-in-use that govern financial transactions. Moreover, they fail to address the deeper (capitalist) structures that indirectly drive biodiversity loss. In this respect, the new Forest Code in 2012 marked a turning point in Brazilian environmental politics that prompted rising deforestation rates, expanding agricultural production and exports, and dismantling of environmental political structures, among others, that neither the CRA market, the Amazon Fund, REDD+ or PES schemes were able to avoid (Reference Rajão, Del Giudice, van der Hoff and de CarvalhoRajão et al., 2021). To borrow loosely from IPBES’ list of key indirect drivers of transformation (Reference Balvanera, Pfaff, Vina, Brondízio, Settele, Díaz and NgoBalvanera et al., 2019), this underscores that we need to rethink the ways in which we conceive of and value nature; how we live, learn, move and appreciate one another; how we produce, consume and trade; and how we govern and confer rights and obligations. It calls for wider structural and systemic changes to our economies, societies and cultures where finance is a component of a broader system of transformative governance (see Chapter 4 on governance mixes). Biodiversity finance, even if optimally funded, is an iota in the world of global finance and trade that drive biodiversity loss, which means that a serious consideration of the ideas proposed throughout this book is warranted.