246 results

Law, Mobilization, and Social Movements

- How Many Masters?

-

- Published online:

- 06 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 28 March 2024

-

- Element

- Export citation

Response to Samuel L. Popkin’s Review of Movements and Parties: Critical Connections in American Political Development

-

- Journal:

- Perspectives on Politics / Volume 20 / Issue 3 / September 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 31 August 2022, pp. 1057-1058

- Print publication:

- September 2022

-

- Article

- Export citation

Crackup: The Republican Implosion and the Future of American Politics. By Samuel L. Popkin. New York: Oxford University Press, 2021. 347p. $27.95 cloth.

-

- Journal:

- Perspectives on Politics / Volume 20 / Issue 3 / September 2022

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 31 August 2022, pp. 1053-1055

- Print publication:

- September 2022

-

- Article

- Export citation

References

-

- Book:

- Power in Movement

- Published online:

- 25 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 11 August 2022, pp 302-342

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Dedication

-

- Book:

- Power in Movement

- Published online:

- 25 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 11 August 2022, pp vii-viii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - Movements in Revolutionary Cycles

- from Part III - Dynamics of Contention

-

- Book:

- Power in Movement

- Published online:

- 25 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 11 August 2022, pp 211-233

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - How Movements Make Meanings

- from Part II - The Powers in Movement

-

- Book:

- Power in Movement

- Published online:

- 25 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 11 August 2022, pp 121-139

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Where Did Movements Come From?

- from Part I - Origins, Theories, and Contentious Action

-

- Book:

- Power in Movement

- Published online:

- 25 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 11 August 2022, pp 25-48

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Preface and Acknowledgments

-

- Book:

- Power in Movement

- Published online:

- 25 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 11 August 2022, pp xiii-xvi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Capitalism, States, and Social Movements

- from Part I - Origins, Theories, and Contentious Action

-

- Book:

- Power in Movement

- Published online:

- 25 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 11 August 2022, pp 49-72

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Figures

-

- Book:

- Power in Movement

- Published online:

- 25 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 11 August 2022, pp x-x

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

11 - Transnational Contention

- from Part III - Dynamics of Contention

-

- Book:

- Power in Movement

- Published online:

- 25 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 11 August 2022, pp 259-281

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- Power in Movement

- Published online:

- 25 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 11 August 2022, pp vi-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Regimes, Opportunities, and Threats

- from Part II - The Powers in Movement

-

- Book:

- Power in Movement

- Published online:

- 25 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 11 August 2022, pp 140-167

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Struggling to Reform

- from Part II - The Powers in Movement

-

- Book:

- Power in Movement

- Published online:

- 25 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 11 August 2022, pp 168-190

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Conclusions

- from Part III - Dynamics of Contention

-

- Book:

- Power in Movement

- Published online:

- 25 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 11 August 2022, pp 282-301

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

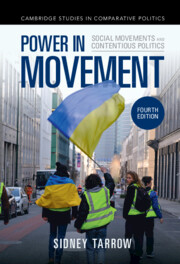

Power in Movement

- Social Movements and Contentious Politics

-

- Published online:

- 25 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 11 August 2022

-

- Textbook

- Export citation

Index

-

- Book:

- Power in Movement

- Published online:

- 25 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 11 August 2022, pp 343-359

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Maps

-

- Book:

- Power in Movement

- Published online:

- 25 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 11 August 2022, pp xi-xi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - Cycles of Contention

- from Part III - Dynamics of Contention

-

- Book:

- Power in Movement

- Published online:

- 25 August 2022

- Print publication:

- 11 August 2022, pp 193-210

-

- Chapter

- Export citation