To America’s watch-me-woke-it-up CEOs I say: When the time comes that you need help with a tax break or a regulatory change, I hope the Democrats take your calls, because we may not. Starting now, we won’t take your money either.

This may be the most openly corrupt thing any Senator has said. It’s the part everyone knows: these crooks sell access. Others have the sense not to admit it. This is why our republic is broken. Immoral politicians selling power we’ve entrusted to them like it’s theirs to sell.

1.1 Introduction

It is commonly said that business is a “game” and that the role of a “player” (business firm) is to “win” (maximize profits) subject to playing by the “rules of the game” (whatever is legal). The implicit idea is that business and politics are separate realms, the first designed to serve private interests through the provision of goods and services, and the second to serve public interests through the provision of national security, a functioning set of legal and political institutions, efficient rules for market competition, and a healthy natural environment. Yet as the abovementioned epigraphs suggest, business and politics are far from separate; they are deeply intertwined through flows of money and information, and business often plays a key role in setting the rules of the game it plays.

In theory, if the public sector sets appropriate rules, then aggressive pursuit of self-interest by the private sector produces socially beneficial outcomes, as Adam Smith (Reference Smith1776) argued two centuries ago, Kenneth Arrow and Gerard Debreu (Reference Arrow and Debreu1954) proved mathematically seventy years ago, and Milton Friedman (Reference Friedman1970) preached in the New York Times Magazine fifty years ago. Yet despite a constant flow of rhetoric about the wonders of the “free market,” Americans increasingly question whether their system of capitalism is delivering the goods. They see average Americans struggling to get by, while the media debate when the world’s richest man, Jeff Bezos, will become the world’s first trillionaire (Molina, Reference Molina2020). They see government providing tax cuts to corporations and the rich and seeming impotent to rein in the market power of technology titans like Amazon, Apple, Facebook (now Meta), Google (now Alphabet), and Twitter. They are convinced the system is rigged against them, and that money buys favors in Washington, DC.

In the face of all this, it is not surprising that there is a growing movement to demand more accountability from business about its role in politics, that is, to demand corporate political responsibility (CPR) as a key complement to corporate social responsibility (CSR) (Lyon et al., Reference Lyon, Delmas and Maxwell2018). More and more companies face proxy votes on disclosing their political spending. Institutional investors with concerns about environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues are demanding more information about corporate spending on politics, and what it accomplishes. Activist groups increasingly call for companies to put their professed “purpose” into action by aligning their political activity with their mission, vision, and values. Environmentally conscious consumers want to know whether the companies they patronize for their “net zero” commitments secretly lobby against regulations to address climate change. As a recent article put it: “Ready or not, the era of corporate political responsibility is upon us” (Lyon, Reference Lyon2021).

In common parlance, the word “responsibility” has two very different meanings. The first reflects causality, that is, the extent to which one thing causes another. The second reflects character, that is, the extent to which an individual or organization is mature and wise in its actions. The two meanings are related, in the sense that a responsible adult takes into account the impacts of his or her actions on others. In legal usage, a “responsible adult” is a guardian of a minor, who is expected to act on behalf of the well-being of the minor. More generally, a responsible adult grants others some degree of moral weight in decisions that may involve personal gains at the expense of costs imposed on others.

Both meanings of responsibility are relevant for CPR. If corporations have no influence on political outcomes, they can hardly be held responsible for them. But if corporations have no influence on politics, why do they spend billions of dollars each year on campaign contributions and lobbying? Thus, the second meaning is of primary interest here. What would it mean for corporations to be responsible participants in the political process? Is it appropriate for them to lobby for policies that would increase their profits at the expense of the broader public?

This chapter offers an initial exploration of the meaning of CPR, from both perspectives. It seeks to open rather than to settle a profound conversation about the appropriate role of business in our modern political system and about the appropriate form of capitalism itself. It begins by defining a set of key terms, and then turns to the first definition of responsibility, briefly surveying the evidence of corporate influence on government policy. It pivots to the second definition of responsibility, highlighting three key pillars that are essential if business is to fulfill its role as a “responsible adult” in the political realm: transparency, accountability, and responsibility. Finally, it provides an overview of the remainder of the volume.

1.2 Defining Key Terms

Although definitions seldom make for riveting reading, it is important to define some key terms before proceeding.

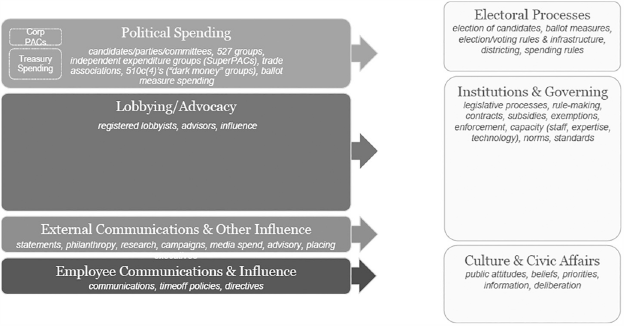

Corporate political activity (CPA) includes any attempts by a company to influence the political process. When ordinary people think of corporate political engagement, they often use the term “lobbying” as a blanket word to capture any attempts to influence government. That usage is far too broad, however, and it is necessary to make additional distinctions about influence activities. CPA encompasses a wide range of influence tactics, as shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Forms of political influence

Political spending is composed of a variety of different types of financial contributions to political campaigns and independent expenditures, or “outside spending,” all meant to influence the electoral process. As outlined by OpenSecrets.org, these can include, but are not limited to, contributions to political action committees (PACs) and so-called Super PACs, different types of political committees that raise and spend money to support or defeat candidates or legislation. Social welfare organizations (501(c)(4)s), which can engage in political action as long as that is not their “primary” activity, labor and agricultural organizations (501(c)(5)s), who generally spend some, but not all, of their money on political activities, and business leagues (501(c)(6)s), like the US Chamber of Commerce, which, like social welfare organizations, may not make political action their “primary” activity, are all active in the political arena, and are often referred to as “dark money groups” for their lack of donor disclosure requirements. Their political activity ramped up after the Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission ruling in 2010, which held that the use of independent expenditures by corporations, like money spent from corporate treasuries for electioneering communications, is protected speech. Figure 1.2 shows that outside spending has grown sharply since the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision in 2010, from about $500 million in the 2010 election cycle to about $3.3 billion in the 2020 election cycle, nearly a factor of 7. The vast bulk of this spending is done by “Super PACs” organized under section 527 of the tax code. These organizations are required to disclose their spending and their donors. However, the figure underemphasizes the role of 501(c)(4) “social welfare” organizations and 501(c)(6) trade associations, both of which can raise unlimited amounts of cash anonymously, but have to ensure their overtly political activities are not seen as their “primary” activity in order to keep their tax-free status. Thus, they are often used as a way to raise “dark money” which they then give to a 527 Super PAC to do the actual spending, without triggering disclosure requirements. Companies may also spend unlimited amounts to influence the outcomes of ballot measures.

Figure 1.2 Lobbying expenditures and outside spending by election cycle

Notes: Only includes outside spending reported to FEC. 501(c)(4): social welfare; 501(c)(5): unions; 501(c)(6): trade associations. Other includes “corporations, individual people, other groups, etc.”

The other form of CPA included in Figure 1.2 is lobbying expenditures, which dwarf campaign spending. These funds are spent on either a firm’s internal lobbyists or a third-party lobbying firm, both of whose main goals are the provision of information to government officials. As lobbyists attempt to convey the likely effects of proposed policies and to shape these policies to benefit their clients, they are required to submit to some basic disclosure requirements. These mandated disclosures show that lobbying expenditures have increased dramatically since the early 2000s, with business interests dominating this arena (Drutman, Reference Drutman2015). Moreover, the figures probably greatly underestimate true spending on lobbying, as they do not include the “shadow lobbying” industry, composed of individuals who perform essentially the same tasks as lobbyists, but categorize themselves as “advisors” and escape mandatory lobbying disclosure rules; although data are scarce, it is estimated that the “shadow lobbying” business may be as large as the disclosed lobbying business (Thomas and LaPira, Reference Thomas and LaPira2017).

Meanwhile, external communications and other outreach can include spending on “informational” campaigns to shape public opinion, such as the organized doubt creation orchestrated by members of the oil industry (Oreskes and Conway, Reference Oreskes and Conway2011) or “grassroots” lobbying groups (astroturf lobbying) that appear to be spontaneous uprisings of individuals, but are actually funded and directed covertly by business groups (Lyon and Maxwell, Reference Lyon and Maxwell2004; Walker, Reference Walker2014). Support for think tanks, some of which are simply partisan advocates (Chiroleu-Assouline and Lyon, Reference Chiroleu‐Assouline and Lyon2020) and philanthropic giving, which may be deployed strategically by companies in need of political support (Bertrand et al., Reference Bertrand, Bombardini, Fisman and Trebbi2020), serve as two other methods of influence, while ballot initiatives, which can be influenced by most of the above-mentioned methods, have their own distinct dynamics of influence.

Lastly, employee communications and influence that encourages employees to be politically active is yet another way for corporations to influence the political process. Some of these efforts may be politically neutral “get out the vote” messages, but after Citizens United, there is no federal protection for workers against employer pressure to fund or vote for particular candidates or take public positions viewed as beneficial to the company.

Although public disclosure policies vary across the different types of CPA, as discussed in more detail by Lyon and Mandelkorn (Reference Lyon, Mandelkorn and Lyon2023), in general, these policies are so lax that it is impossible to get an accurate assessment of total spending on CPA. Nevertheless, publicly disclosed data provide a lower bound on spending on political influence.

With caveats regarding the limitations of available data, it is clear that the role of money in US elections continues to grow. As shown in Figure 1.3, the total cost of federal elections (i.e., spending by candidates’ campaigns, political parties, and independent interest groups) grew steadily from the 2000 election cycle through the 2016 election cycle, from about $3 billion to $6 billion, and then jumped sharply upward to $14 billion during the 2020 election cycle. In general, total spending on congressional races exceeds that for presidential races. Figure 1.3 also shows that lobbying spending has grown apace with electoral spending, from about $3 billion total across 1999 and 2000 to about $7.5 billion total across 2009 and 2010, and stayed around $7 billion per two-year election cycle through 2020.

Corporate social responsibility means corporate efforts that go beyond compliance with legal requirements on either the environmental or social dimensions of performance. This could include corporate commitments to reduce greenhouse emissions or achieve “net zero” carbon emissions by a certain date, initiatives to create opportunity for historically underrepresented minorities, or policies to support human rights in developing countries.

CPR means transparency and accountability of corporate lobbying and other political influence, as well as a commitment to advocate publicly for policies that sustain the systems upon which markets, society, and life itself depend. The latter would include advocating for the elimination of market failures and special-interest subsidies, which undermine the performance of the capitalist system, and for the maintenance of the Earth’s climate, a functioning representative political system, and planetary biodiversity.

Political corporate social responsibility (PCSR) holds that firms have a responsibility to fill in gaps in global regulatory governance where the nation-state has failed to do so and to make “a more intensive engagement in transnational processes of policy making and the creation of global governance institutions” (Scherer and Palazzo, Reference Scherer and Palazzo2011, p. 910). Thus, firms may provide public health benefits, address AIDS, and promote societal peace and stability. PCSR emphasizes Habermas’s concept of “deliberative democracy,” which explores the formation and “transformation of preferences” through dialogue and analyzes the conditions under which deliberation “will lead to more informed and rational results, will increase the acceptability of the decisions, will broaden the horizon of the decision maker, will promote mutual respect, and will make it easier to correct wrong decisions that have been made in the past” (Scherer and Palazzo, Reference Scherer and Palazzo2007, p. 1107). The authors distinguish PCSR from mere corporate responses to stakeholder pressure, arguing that PCSR calls for moral leadership from companies.

Relative to CPR, PCSR is a broader and more encompassing concept, and includes corporate participation in both private and public politics. CPR, in contrast, focuses on corporate engagement in public politics. An example that illustrates the difference is the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), which puts forward voluntary standards for forest management that many companies have adopted. Companies also participate in the governance of the FSC and the articulation of the standards it promotes. Scherer and Palazzo (Reference Scherer and Palazzo2007) use this as an example of PCSR, but it would not be an example of CPR because it does not involve the public political process. Scherer and Palazzo (Reference Scherer and Palazzo2007) laud corporate engagement with FSC as “a corporate move into the political processes of public policy making” (Scherer and Palazzo, Reference Scherer and Palazzo2007, p. 1110), but we do not consider FSC to be a public policy process at all because there are no governments involved. Moreover, simply engaging with a voluntary standards organization provides no assurance that a firm is actually enhancing sustainability outcomes. Instead, it may simply be driving standards down, which would not count as CPR, in my view.

Corporate citizenship (CC) means “the role of the corporation in administering citizenship rights for individuals” (Matten and Crane, Reference Matten and Crane2005, p. 173). They elaborate:

With regard to social rights, the corporation basically either supplies or does not supply individuals with social services and, hence, administers rights by taking on a providing role. In the case of civil rights, the corporation either capacitates or constrains citizens’ civil rights and, so, can be viewed as administrating through more of an enabling role. Finally, in the realm of political rights, the corporation is essentially an additional conduit for the exercise of individuals’ political rights; hence, the corporation primarily assumes administration through a channeling role.

This conception is quite different from the conception of CPR as describing the way in which a corporation exercises its own rights within the political system.

1.3 Is Corporate Political Activity Responsible for Government Outcomes?

In practice, the worlds of business and politics are not neatly separated, despite appeals for business to stay out of politics altogether (Reich, Reference Reich1998). There is a widespread perception that the US political system has been corrupted by money and corporate influence, so that the “players” are setting the rules, to the detriment of the rest of society. Politicians from across the political spectrum decry the capture of our government by the wealthy. Independent Bernie Sanders says, “A few wealthy individuals and corporations have bought up our private sector and now they’re buying up the government. Campaign finance reform is the most important issue facing us today, because it impacts all the others.”Footnote 3 At the other end of the political and credibility spectrum, Republican Donald Trump also claims “the system is rigged,” at least whenever he loses. And closer to the middle of the political spectrum, Democratic Senator Sheldon Whitehouse warns that “corporations of vast wealth and remorseless staying power have moved into our politics to seize for themselves advantages that can be seized only by control over government.”Footnote 4

Ordinary Americans largely agree with these assessments. Even in 2009, before the Citizens United v. FEC ruling removed constraints on corporate political spending, 80 percent of Americans agreed with the following statement: “I am worried that large political contributions will prevent Congress from tackling the important issues facing America today, like the economic crisis, rising energy costs, reforming health care, and global warming.” In the first presidential contest after the Citizens United decision, 84 percent of Americans agreed that corporate political spending drowns out the voices of average Americans, and 83 percent believed that corporations and corporate CEOs have too much political power and influence. This aligns with more recent research showing that 84 percent of people think government is benefiting special interests, and 83 percent think government is benefiting big corporations and the wealthy.Footnote 5

Moving beyond public opinion, numerous books suggest that American government has been captured by business, from Whitehouse’s own Captured: The Corporate Infiltration of American Democracy to Lee Drutman’s The Business of America Is Lobbying to Alyssa Katz’s The Influence Machine: The US Chamber of Commerce and the Corporate Capture of American Life. All of these books suggest that corporate influence has successfully raised profits by cutting taxes on business, weakening antitrust enforcement, allowing the outsourcing of American jobs to low-wage countries, undermining environmental law, and limiting corporate tort liability for social harms such as defective products, lung cancer from tobacco use, and climate change.

Economic data indeed document that corporate market power and the concentration of wealth have been rising: market concentration, price/cost markups, profits, and capital’s share of income relative to labor have all risen sharply over the past four decades. In the United States, aggregate price markups over marginal cost rose from 21 percent in 1980 to 61 percent in 2019, while the average profit rate rose from 1 to 8 percent. This is consistent with the decline in labor’s share of income from around 62 percent in 1980 to 56 percent in 2019 (DeLoecker et al., Reference De Loecker, Eeckhout and Unger2020). The top 10 percent of Americans captured 33 percent of net income (excluding capital gains) in 1980 but 41 percent by 1998, while the top 1 percent saw their share rise from 8 percent to 14 percent (Piketty and Saez, Reference Piketty and Saez2003). Wealth is even more highly concentrated: the top 10 percent held 77 percent of the wealth in the United States in 2018, up from about 65 percent in 1980. At the other extreme, the average real disposable cash income of the bottom 50 percent in the United States rose only slightly from $16,000 in 1980 to $18,600 in 2016 (Saez and Zucman, Reference Saez and Zucman2020).

But is this growing concentration of wealth and profits the result of CPA, or is it the “natural” outcome of broader trends such as globalization and technological change? This is the $64 million question, but it is very difficult to answer authoritatively, in part because so much of CPA is intentionally hidden from the public. Bessen (Reference Bessen2016) attempts to address the question directly and concludes that both corporate investment in intangibles and CPA have played a role in rising profits, but since 2000 political action has been the more important factor; in addition, he finds that the relatively few major extensions of regulation have raised corporate profits significantly. At the same time, the highly publicized work of Princeton political scientists Gilens and Page (Reference Gilens and Page2014) finds that “economic elites and organized groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on U.S. government policy, while average citizens and mass-based interest groups have little or no independent influence.” This is consistent with polling data showing that many policies supported by a wide majority of Americans die in committee. According to recent polling by Data for Progress and Civis Analytics, the majority of Americans support expanded paid family leave policies, corruption reforms to rein in conflicts of interest among lawmakers, and the government manufacture of out-of-patent generic drugs, all of which have been introduced in recent bills that have failed to pass.Footnote 6 Lawrence Lessig (Reference Lessig2015) argues that the role of money in politics is to edit public choices by ensuring that the only candidates who can afford to compete for election are those acceptable to moneyed interests.

Although it is conventional wisdom among political scientists that money buys access to politicians, recent research advances have documented the effect clearly: randomized field experiments demonstrate that money does indeed buy access to politicians (Kalla and Broockman, Reference Kalla and Broockman2016). As if to prove this point, Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) wrote a sneeringly self-righteous opinion piece in the Wall Street Journal that sternly told companies not to object to Republican-sponsored bills to protect “election integrity” in the wake of Trump’s false claims that the 2020 election was “stolen” (Cruz, Reference Cruz2021). For those with short attention spans, he also tweeted the quote that introduces this chapter.

None of the foregoing proves conclusively and scientifically that corporate capture of the political process is the root cause of growing market concentration, rising economic inequality, and the inability of ordinary people to influence their own government. In fact, some observers argue that business has been held hostage by greedy career politicians whose notion of the public interest is limited to keeping themselves in power (Crow and Shireman, Reference Crow and Shireman2020). A related view is that the fundamental problem in US politics is the lack of competition in the US electoral system, with only two viable parties to choose from (Drutman, Reference Drutman2020; Gehl and Porter, Reference Gehl and Porter2020). Since the Supreme Court unleashed unlimited amounts of anonymous political spending in 2010, the parties have had an insatiable demand for cash to fund vicious and uninformative attack ads that can be used to destroy the other side. And Corporate America makes an easy mark for politicians like Cruz who openly admit that their votes are for sale.

If Big Business has been corrupted by immoral politicians, though, it seems to have gone to the Dark Side willingly. Tom Donohue, former president of the US Chamber of Commerce, bragged in 2010 about what was reported as the Chamber’s “hard-hitting $75 million ad campaign to elect a Republican House” and he promised to spend “closer to a hundred million” on the 2012 elections (Katz, Reference Katz2015, p. 177). Unfortunately, it is impossible to conduct the requisite empirical research to disentangle the complex web of political influence without data on the role of business in the political sphere – and Congress intentionally prevents those data from being made public.Footnote 7

1.4 The CPR Movement

In light of the dysfunctional state of US politics, the strong circumstantial evidence of corporate capture of the policy process, and the growing role of “dark money” in American politics, it is small wonder that a movement has emerged to hold companies accountable for their role in the political process. Companies are accustomed to stakeholder demands for CSR, and this new movement can be seen as an extension reflecting the awareness that “CSR Needs CPR,” as one recent article puts it (Lyon et al., Reference Lyon, Delmas and Maxwell2018).

In some issue areas, such as climate change, the extension of CSR into CPR is a natural outgrowth. Climate activists have been increasingly frustrated since the failure of the Lieberman-Warner bill to pass in 2009. They have watched with disgust as companies such as Exxon funded doubt-mongering strategies through “think tanks” such as the George C. Marshall Institute and the Competitive Enterprise Institute (Oreskes and Conway, Reference Oreskes and Conway2011), the latter of which once produced a gauzy TV ad with the tag line: “Carbon dioxide: they call it pollution, we call it life.” They have watched with anger as the Chamber of Commerce took not a “lowest common denominator” approach to climate lobbying, but simply a “lowest possible” approach. In the spring of 2008, as Lieberman-Warner was in committee,

[T]he Chamber sponsored an apocalyptic TV and Internet ad campaign aimed at the senators who would decide. On the screen of one ad, a man bundled in a scarf and coat prepared his morning eggs in a pan held over burning candles, before he joined a pack of commuters jogging down the highway to work. “Climate legislation being considered by Congress could make it too expensive to heat our homes, power our lives and drive our cars,” warned the voice of God in the ad. “Is this really how Americans want to live? Washington politicians should not demand what technology cannot deliver. Urge your senator to vote no on the Lieberman-Warner climate bill.”

And activists watched with despair from the sidelines as coal executive Robert Murray donated $300,000 to Donald Trump’s inauguration shortly before he sent Trump his “Action Plan” for the new Administration, and sat back and saw much of it get enacted (Friedman, Reference Friedman2018). It is no wonder climate activists are focusing on how fossil fuel companies block climate policy.

In other issue areas, however, the calls for CPR are more of a surprise. The unprecedented January 6, 2021, assault on Congress led many companies to “pause” their funding of legislators who refused to certify the legitimacy of the 2020 presidential election. And the slew of voter registration bills moving through state legislatures in the wake of the 2020 election have also drawn rebukes from many corporate leaders who accept the claims of the Black community that the bills will disproportionately make it harder for Black Americans to vote. Both of these issues came into existence solely due to the losing candidate’s repeated falsehoods that the election was “stolen” by massive amounts of voting fraud. Only corporate executives with a keen sense of history and awareness of the parallels between the fire in the Reichstag in February 27, 1933, and the assault on Congress would have had any hope of predicting the emergence of these new CPR issues.Footnote 8

These calls for CPR have arisen more frequently, not only in public, but in shareholder meetings as well. According to recent reporting by the New York Times, in 2019 there were fifty-one political spending proposals at S&P 500 companies, which received an average of 29 percent support and zero proposals passed (Livni, Reference Livni2021). In 2020, six of the fifty-five political spending proposals at S&P 500 companies 2020 passed, with average support rising to 35 percent. As of June 2021, of the thirty resolutions introduced that year, five of the seven proposals put up for a vote had passed. In the face of relatively few political spending reporting guidelines as mandated by law, more successful shareholder political spending resolutions could lead to much needed transparency surrounding corporate political activities.

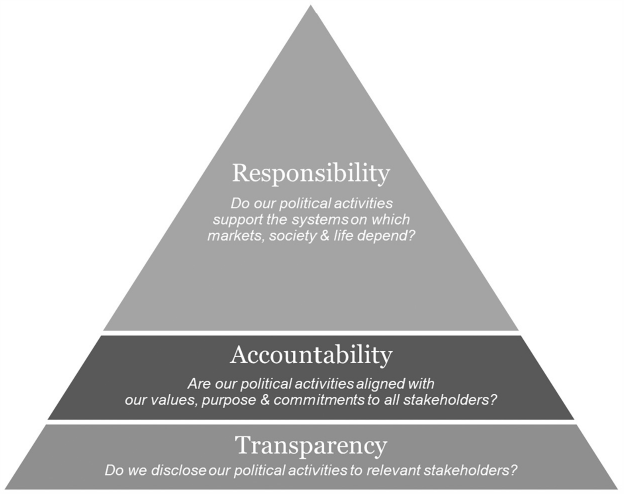

1.5 The Three Levels of CPR

The concept of CPR was articulated in an article by Lyon et al. (Reference Lyon, Delmas and Maxwell2018). Transparency, accountability, and responsibility comprise the three tiers of CPR, as illustrated in Figure 1.4.

Figure 1.4 The three tiers of corporate political responsibility

Transparency covers whether or not a firm discloses their political activities to the relevant parties. While some elements of CPA, like lobbying expenditures, must be disclosed legally, others forms, like contributions to 501(c)(4) “social welfare organizations” and 501(c)(6) trade associations, need not be disclosed at all. Firms can voluntarily report these activities, with more firms recently choosing to release political engagement reports, as discussed in more depth by Lyon and Mandelkorn (Reference Lyon, Mandelkorn and Lyon2023), but production of these reports is currently limited and there are no accepted norms of best practice yet. Some organizations like Vigeo Eiris and Influence Map are helping to lead a charge toward more widespread, careful analysis of CPA, but much work remains to be done with regard to measuring transparency.

Accountability focuses on whether firms’ political activities are “aligned with [their] values, purpose and commitments to all stakeholders.” Like the transparency tier below, it is difficult to measure and evaluate whether a firm is being “accountable.” Not only is data needed to accurately measure a firm’s CPA, but additional data and analysis is needed to measure the congruence between a firm’s CPA and its stated values. Organizations like CPA-Zicklin are working hard to improve accountability for the political spending elements of CPA, developing a “Model Code” to help guide corporate political expenditures and advocacy and ensure that firms do not exercise their political clout at the expense of shareholders, employees, or other stakeholders. This work represents an important advance, yet further efforts are required to ensure full accountability across the private sector, as described in more detail in Lyon and Mandelkorn (Reference Lyon, Mandelkorn and Lyon2023).

Lastly, responsibility centers on the firm’s role in the public sphere, especially on whether a firm’s political activities “support the systems on which markets, society and life depend.” At first glance, it may seem that responsibility is too subjective an idea to be useful in practice. For example, customers who believe climate change is a Chinese hoax (as claimed by ex-president TrumpFootnote 9) or oil-industry employees whose jobs are at risk may think it irresponsible for a company to support climate policy, while customers who see climate change as an existential threat to life on Earth (as claimed by the vast majority of climate scientists) may find it irresponsible not to support climate policy. But a facile “post-truth” position serves only the narrowly self-interested and the peddlers of falsehoods. A more thoughtful, and practical, perspective can be grounded in the market failures approach to business ethics (Heath, Reference Heath2014). This approach begins from the observation that maximizing profits is justified when markets are competitive because doing so increases overall social welfare. However, when the conditions for perfect competition fail, and we observe market failures like market power, externalities, public goods, and asymmetric information, there is no guarantee that free markets, or profit-maximization, promote welfare. Hence profit-maximizing firms arguably have a responsibility to support the conditions that make markets competitive, and to eschew CPA that exacerbates market failures (Heath, Reference Heath2014). Of course, it is impossible to assess whether a given company is undermining markets or practicing CPR without the first two pillars of transparency and accountability.

Much of the analysis in the rest of this book focuses on the first two tiers, transparency and accountability, both because they are necessary to assess the third tier and because the analysis of market failures and planetary systems requires deep and issue-specific work. However, in the case of climate change, there is already a rich literature on which to draw for assessing CPR, so the book includes an entire section devoted to the topic of responsibility in this particular context. The following section explains the plan of the volume in more detail.

1.6 Overview of the Rest of the Volume

The rest of the book is divided into four main sections, plus a final chapter on the implications for practice. Section I offers insights into the underpinnings of CPR, with an emphasis on the importance of transparency as the foundation stone. Freed, Laufer, and Sandstrom describe the creation and current activities of the Center for Political Accountability, a Washington, DC, nonprofit they helped launch that is the leader in the movement for greater transparency and accountability around corporate spending on electoral campaigns. Lyon and Mandelkorn position corporate election spending within the larger universe of corporate political activity (CPA), and show how holes in the current disclosure system make it impossible to answer many of the most important questions about the influence of business on politics.

Section II focuses on the foundation stone of transparency, providing the latest findings on the causes and consequences of corporate disclosure from two of the leading empirical researchers on CPA. Walker studies the drivers of disclosure, presenting early results of research funded by the National Science Foundation, while Werner studies how investors react to disclosure and what we can learn from their reactions.

Section III moves up the pyramid of CPR one level, turning to corporate accountability to stakeholders for CPA, with a focus on the links between CSR and CPR, especially around employees. Favotto, Kollman, and McMillan test whether firms with better reputations for CSR offer higher-quality information to legislators, using data from corporate testimony before the UK Parliament. Darnell and McDonnell test whether firms with better reputations for CSR elicit more employee contributions to the corporate Political Action Committee. Scherer and Voegtlin take a normative perspective, arguing that multinational companies should connect their Human Resources Management policies to their CSR, with the goal of being both good stewards of employee well-being and good enablers of employee political expression.

Section IV reaches the top tier of the CPR pyramid, tackling the issue of political responsibility in the context of climate change, one of the areas where irresponsible CPA has been the most glaring. Ketu and Rothstein present the perspective of Ceres, a nonprofit that (among other things) rates the world’s 100 largest companies on whether their climate advocacy is responsible or not. Vogel relates the past quarter-century of corporate political engagement around climate change in the United States, showing that “business” is not a monolith and that fundamental principles of political science go a long way toward explaining corporate responsibility and irresponsibility in climate politics. Delmas and Friedman provide empirical evidence suggesting strongly that business firms lobby on both sides of the climate issue, and they shine a light on the gaps in disclosure that make it difficult to hold companies responsible for their political activity around climate policy.

The concluding chapter explores the opportunities and challenges of implementing CPR in practice. Doty draws upon the experience of the Corporate Political Responsibility Taskforce (CPR) at the University of Michigan’s Erb Institute, offering illuminating insights into why CPR is difficult for companies and why it can produce big payoffs if done right.

A more detailed overview of the remaining chapters follows.

Section I Foundations of Corporate Political Responsibility: Metrics for Disclosure and Good Governance

Freed, Laufer, and Sandstrom focus on corporate political spending on elections (either through contributions to politicians or through spending on independent, direct political communications). They draw heavily on the experience of the nonprofit Center for Political Accountability (which the authors were instrumental in founding) and its use of “private ordering” (informal, non-state suasion and advocacy) to drive greater accountability around corporate electoral spending. The Center is generally viewed as the most effective organization promoting political accountability, so its story is central to understanding where CPR stands today. The Center’s success is attributable in part to its consistent focus on electoral spending (as opposed to lobbying) and accountability to shareholders (as opposed to the full range of stakeholders affected by corporate political activity). Future efforts to encompass a broader range of corporate political activity and stakeholder impacts would do well to learn from the experience of the Center.

Lyon and Mandelkorn discuss the thorny issue of measuring CPR. They present an overview of the various forms of corporate political action (CPA), and the requirements in the United States for disclosure of each form. They organize the discussion around the metrics needed to assess the three levels of CPR: transparency (disclosing CPA), accountability (ensuring that firms are accountable to their stakeholders for CPA), and responsibility (corporate advocacy for public policies that are consistent with a company’s stated mission, purpose and values, and that strengthen the systems on which markets, states, and life itself depend). They describe the efforts of existing organizations to evaluate CPR, expose information gaps where lax disclosure requirements make it impossible to evaluate CPR today, and suggest improvements needed in order to make it possible for stakeholders to assess whether or not CPA is responsible.

Section II Transparency: Causes and Consequences

Walker presents findings from a large-scale empirical study of the factors driving firms to disclose their political activity. He points out that public politics has largely failed to require thorough disclosure of CPA, and hence private politics has been the main driver of change, consistent with the argument of Freed, Laufer, and Sandstrom. He goes on to examine two key empirical questions: (1) which companies get targeted by shareholder activists seeking greater voluntary CPA disclosure and (2) how have those targeted companies responded? Among his findings are that, overall, companies are targeted by shareholders for CPA-related shareholder resolutions on the basis of their prior political activities, financial characteristics, their history of facing past shareholder resolutions, and other qualitative factors including their reputational challenges, history of engagement on ESG issues, and whether their CPA might appear to be misaligned with other value commitments. Companies, in turn, tend to be more likely to make reforms after facing CPA resolutions in prior years and also, particularly, if and when they become constituents of the S&P 500 Index, as membership in that Index causes a firm to draw considerably greater scrutiny.

Werner offers a set of empirical insights into how markets respond to corporations engaging in dark money expenditures. Studying covert CPA would seem to be an impossible challenge, but Werner is able to shed light on dark money by making use of accidental disclosures of corporate involvement with it. He shares findings from several different studies, and finds that investor responses to accidental disclosure of covert CPA are nuanced. The Supreme Court’s decision in Citizens United did not produce abnormal financial returns for politically active firms, suggesting that investors did not think there was much value in opening the floodgates of corporate political spending. Accidental disclosure of corporate giving to the Republican Governors Association, a highly partisan group, raised share prices for corporate contributors. However, accidental disclosure of giving to the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), whose bland name belies its hard-right activist agenda, caused share prices for corporate contributors to fall. Thus, the effects of corporate engagement with dark money groups seem to be contingent on a variety of factors that require further analysis. Werner holds out little hope that further strides toward CPR can be made through private politics. Instead, he argues that reform efforts should move beyond disclosure and instead focus on constitutional changes that will permit greater regulation of money in politics.

Section III Accountability: Linking Corporate Social Responsibility, Employee Relations, and Corporate Political Responsibility

Favotto, Kollman, and McMillan move beyond disclosure to provide valuable empirical insight into accountability and responsibility, and whether better CSR translates into better CPR. They find consistent differences in the quality of the testimony offered to parliament by high- and low-CSR companies. High-CSR companies were more willing to discuss state interventions into the market in their testimony, more likely to support state regulation and more likely to offer committee members sophisticated justifications for their policy stances than low-CSR companies. The high-CSR firms also tended to use a broader array of reasons for their policy stances and did not focus solely on market interests as low-CSR companies tended to do. Thus, high-CSR companies’ lobbying efforts do appear to be more aligned with the goal of sustainability.

Darnell and McDonnell also explore the links between a company’s CSR and its CPR. More specifically, they examine whether a better reputation for employee relations, or for CSR more broadly, is related to the level of employee contributions to the firm’s corporate political action committee (PAC). They find that a firm’s reputation for employee relations, but not its overall social reputation, is positively associated with employee support of a firm’s PAC. Although these findings do not speak directly to whether a firm’s CPA is responsible, they do illustrate a link between a firm’s informal and formal nonmarket strategies and demonstrate a potential constraint on corporate political influence.

Scherer and Voegtlin delve further into the links between employee relations and CPR, by focusing on the human resource management (HRM) practices of multinational firms in a globalizing world. They propose that HRM should be extended to include a political agenda through two functions: (1) as a “steward” looking out for the wellbeing of the firm’s work force, and (2) as an “enabler” making organizational members competent for helping others. This is consistent with the observation that employees are often the strongest stakeholder group calling for more CPR from their employer, and that employee support for CPR can legitimize and strengthen the firm’s position in the political domain, as shown by Darnell and McDonnell. They also serve as a strong reminder that issues of CPR go beyond the climate crisis and include human and labor rights, and that a deliberative approach that pays close attention to corporate engagement in dialogue (as shown by Favotto et al.) can be a productive avenue for illuminating and possibly strengthening CPR.

Section IV Responsibility: Corporate Political Responsibility and Climate

Ketu and Rothstein share their experience working to elevate companies’ policy engagement around climate. The authors are both part of Ceres, a nonprofit organization working with influential investors and companies to drive Responsible Policy Engagement on climate change. Recently Ceres produced a report rating the 100 biggest corporations on how well they align their political action with their CSR activities. Although most companies have a long way to go to become leaders in constructive climate policy, there is considerable heterogeneity within the S&P 100. The authors share the key elements they see as part of Responsible Policy Engagement, and suggest ways to accelerate the diffusion of these practices throughout the C-suites of the most influential companies.

Vogel focuses on climate lobbying, from a historical perspective that goes back to the Kyoto Protocol, includes the Waxman-Markey and Lieberman-Warner bills, the Obama administration’s proposed Clean Power Plan, and the international Paris Agreement. He shows that “business” is not a monolithic block when it comes to climate policy. Vogel pays particular attention to the role of collective action, both through trade associations and a wide range of ad hoc climate coalitions. He reminds us that energy companies have strong, even existential, incentives to block climate policy, while the rest of the private sector generally has weak incentives to support it. This raises important questions about the depth of commitment expressed by the many companies that now speak out on behalf of climate policy, and about the limits of what can be accomplished through encouraging business climate advocacy.

Delmas and Friedman focus on corporate lobbying on climate change, which consumed over $2 billion between the years 2000 and 2016. Although such spending is largely perceived as a strategy by industry to oppose regulation, the authors show that there is a U-shaped relationship between greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and lobbying expenditures, suggesting strongly that both dirty and clean firms are active in lobbying. Unfortunately, limitations on legal requirements for detailed disclosure make it impossible to clearly infer corporate positions on policies and fail to capture the full array of CPA. However, there are a number of initiatives aimed at increasing disclosure, coming from investors and asset managers, NGOs, public institutions such as the EU, nonprofits, and academics. The authors offer a series of potential improvements to mandatory disclosure of climate-related political activity, including consideration of content, timing, disclosure channels, users, potentially relevant US regulators, and the value of third parties in aggregating, interpreting, and disseminating information gleaned from disclosures.

Section V Implementing Corporate Political Responsibility: Opportunities and Challenges

Doty returns us to the practitioner perspective, drawing upon the experience of the Erb Institute’s CPR Taskforce (CPRT). She suggests that the new emphasis on CPR heralds a larger conversation about the role of business in society, and argues that if such a conversation is to have legitimacy and lasting impact, it must understand and incorporate the perspectives of practitioners. Like Favotto et al. and Scherer and Voegtlin, Doty presents the principles of deliberative democracy as guidance for this larger conversation. She provides fascinating quotes from participants in Erb CPRT discussions, which shed new light on how businesses think about CPR. Company leaders find the concept of CPR intuitive but scary, and lament the lack of venues for discussing it without the bitter polarization that too often passes for discourse. This, of course, was precisely the rationale for forming the CPRT. Doty sees CPR as likely to find a home within the “G” of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) criteria for investors. She also suggests that firms may need to address governance issues around CPR before they are willing to undertake more disclosure. Finally, she offers a set of ideas for moving CPR into mainstream business practice, and using it as an opening for a renewal of the social contract. If CPR can perform these functions, it will truly be a transformative concept.

1.7 Conclusions

Today, growing numbers of people feel disenfranchised from the political process. In some countries, corporations and outside groups can spend unlimited amounts on elections, but many individuals find it increasingly difficult even to vote. They have seen tax cuts and financial bailouts enacted that benefit large corporations and wealthy individuals at their expense. Americans are convinced the system is rigged, and it is precisely these groups, large corporations and the ultra-wealthy, that they blame. They have seen mega-donors like Sheldon Adelson spend hundreds of millions of dollars every year to elect their preferred candidates, and trade associations like the US Chamber of Commerce spend billions of dollars lobbying to bend legislation to the liking of certain corporate members. In a world increasingly shaped by the wealthy few, many ordinary Americans are looking for ways to hold large corporations accountable for their political actions.

Americans, especially younger ones, care about the political positions taken by the companies from which they purchase and invest. They want the companies they patronize to support progressive climate policies, or cease giving to those who supported the January 6 insurrection. In short, they want firms to exhibit corporate political responsibility.

Unfortunately, as the following chapters document, the current level of disclosure mandated by law in the United States provides a woefully incomplete picture of corporate political activity, rendering it difficult to distinguish the responsible from the irresponsible. Nevertheless, while serious measurement issues remain, great research is being done in this area. The remainder of this volume serves to document some of this research, along with some of the improvements that could be made in CPA metrics to improve our understanding of CPA and CPR.

Even if we cannot answer all of our questions about CPA currently, the need for more firms to demonstrate CPR remains clear. We need enough transparency and disclosure concerning electoral spending and lobbying that one can monitor the scope of a firm’s political influence activities. We need companies to have policies governing the lobbying and political contribution process, with specific officers and boards actively engaged and carefully overseeing their political influence activities. Finally, as some of the most powerful actors in politics, companies must take more responsibility for the health of the governmental systems in which they participate. Public demands are growing for companies to change their role in politics, with increased transparency of electoral spending and lobbying, accountability for corporate political activity within companies, and responsibility for the political system within which they operate serving as the three main levers through which firms can exhibit more CPR, and begin to effect positive change in the political process. This book is an attempt to sharpen academic and practitioner understanding of CPR, and support its emergence into the world of practice.