Introduction

“The great disruptor” was a term applied to President Donald Trump by both his friends and his foes as his administration pursued policies on countless issues that were not only the opposite of former President Barack Obama’s, but in many cases out of step with decades of Republican orthodoxy. In foreign policy this trend towards disruption was clearly on display in US relations with the Korean peninsula. Appearing to turn traditional diplomacy towards the two Koreas on its head, Trump went to extraordinary lengths to cultivate friendly relations with North Korea (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea or DPRK), while at the same time demanding humiliating concessions on trade and security issues from South Korea (Republic of Korea or ROK) – an American ally of nearly seven decades.

Both policies were seen at the time as dramatic breaks with the past, and in some senses this was true. No sitting US president had ever met face to face with any member of the Kim family – the hereditary dictators of the DPRK. While other presidents had sought changes in the US–ROK alliance, including the withdrawal of American forces, none had paired them with the insults and dismissiveness towards the ROK that Trump displayed.

In the broader historical context of US relations with the Korean peninsula, however, President Trump’s policies towards the ROK and the DPRK appear more as variations on a theme than dramatic breaks with the past. For many South Koreans Trump’s bullying was just the latest chapter in their troubled history with the US: a history in which American leaders make decisions and demands with little regard for the consequences on the peninsula. While Trump’s three meetings with Kim Jong-un could rightly be called historic in a narrow sense, there is ample evidence they were just the latest installment of what some scholars refer to as “entrepreneurial diplomacy” with the DPRK – a type of diplomacy that thrives in the absence of official diplomatic relations between the two states and tends to yield greater benefits to the practitioners themselves.

This chapter will provide a broad historical context for understanding the Trump administration and its approach to the Korean peninsula. It will proceed in three sections. The first section will survey US relations with the Korean peninsula from 1882 to the creation of both the ROK and the DPRK in 1948. An understanding of this period is essential to grasping why Koreans harbor feelings of distrust towards the US, rooted in what they believe was the American role in Korea’s colonization and division. The second section will examine US relations with the ROK since 1948, paying special attention to the evolution of the US–ROK alliance from its beginnings in 1953 as a grudging American concession to the ROK to a broad partnership between the two states based on shared interests and values. The third section will examine US–DPRK relations since 1948 to explain both the absence of official relations between the two states and how entrepreneurial diplomats have thrived in this void. Each section highlights the relevance of these historical periods to the Trump administration’s approach to Korea. The chapter concludes with some general thoughts about what was, and was not, new about Trump’s Korea policy.

A Reliable Ally? US Relations with the Korean Peninsula, 1882–1948

Any conception of US–Korean relations starting in the mid-twentieth century will have difficulty accounting for the ambivalence many in the ROK currently feel towards the US, which on the one hand is the ROK’s indispensable ally, and on the other was at least complicit in the three great Korean tragedies of the twentieth century: Korea’s colonization by Japan, its division in 1945, and the Korean War.

Formal diplomatic relations between the US and the Kingdom of Joseon, as Korea was then known, were established by the 1882 Treaty of Peace, Amity, Commerce, and Navigation (hereafter the 1882 Treaty). This treaty was primarily the result of the efforts of two men: Chinese diplomat and strategist Li Hungzhang and American Admiral Robert Shufeldt. Li hoped the establishment of relations between the US and Joseon would forestall Japanese ambitions on the Korean peninsula and preserve the Chinese sphere of influence there. Shufeldt’s ambitions were likely more personal. For him, negotiating a treaty that “opened” Korea to the US would give him a legacy in some ways comparable to the then-renowned Commodore Mathew Perry, who had “opened” Japan. Shufeldt personally lobbied the State Department to be given the task. Such personal ambitions gave Shufeldt the stamina necessary to persevere through the long and tortuous negotiations with Li, in which Shufeldt doggedly resisted Li’s attempts to insert into the treaty language recognizing a Chinese sphere of influence in Korea.Footnote 1 All negotiations were held in China, with Li negotiating on behalf of the Koreans. Shufeldt did not meet a Korean diplomat until the brief signing ceremony in what is now Incheon.

The result was a treaty that was far more important to the Kingdom of Joseon than it was to the US. King Gojong, the last monarch of traditional Korea, placed a great deal of confidence in Korea’s relationship with the US, even believing that the 1882 Treaty entailed an American commitment to Korea’s independence.Footnote 2 Gojong’s belief was the result of wishful thinking – some of which was encouraged by American diplomats and missionaries in Seoul – as well as a misinterpretation of Shufeldt’s insistence that the US would not recognize a Chinese sphere of influence in Korea. Unfortunately for Gojong and Joseon, American policymakers intended no such commitment to Korea. As one American diplomat in China wrote in 1883, “having opened the door to Corea [sic] we should go in and do what good we may,” but “We [the US] have very little to lose whether Corea becomes a province of China or is annexed to Japan or remains independent.”Footnote 3 A clearer statement of American ambivalence towards the Korean peninsula during this period can hardly be found.

The true American position on Korea became clear in 1904 when the Japanese occupied the Korean peninsula during the Russo-Japanese War and began the process of colonization. Korean envoys, including future ROK president Syngman Rhee, sent to the US to request support for Korea’s independence based on Gojong’s understanding of the 1882 Treaty, were met with evasive answers from the Theodore Roosevelt administration, if they were answered at all. Roosevelt’s Secretary of War, William Howard Taft, had already informed the Japanese prior to the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War that the US had no interest in the Korean peninsula, and in return received assurances that Japan had no interest in the Philippines, an American colony since 1898.

This exchange of views, known as the Taft–Katsura Memorandum, was not a quid pro quo, much less a “secret treaty” [밀약] as it is still widely known in Korean; the US was disinterested in Korea regardless of the Japanese stance on the Philippines. Still, Roosevelt’s inaction angered Korean nationalists, who believed the US had disregarded its responsibilities towards Korea and been complicit in Japan’s colonization. The Taft–Katsura Memorandum, and the alleged violations of the 1882 Treaty that it entails, is still relevant in US–Korean relations over a century later. For North Koreans, the Taft–Katsura Memorandum is an early example of what they believe is American perfidy and a link between the Japanese colonization of Korea and Korea’s later division. For many South Koreans, it is evidence of at least tacit American complicity in their country’s colonization by Japan. The episode also raises doubts about the US’s trustworthiness as an ally, which have never gone away entirely and were exacerbated more by Donald Trump than by any other recent president.

From 1905 to 1945, Japan occupied and then colonized Korea. This colonization was recognized by the US, which quickly downgraded its embassy in Seoul to a consulate. Ironically, it was during this period that American interest in the Korean peninsula grew. In 1907 Korea experienced one of the great Christian revivals of the twentieth century, and American missionaries began to tout the possibility of Korea becoming the first “Christian nation” in Asia. American interest in Korea grew further after the 1919 March First Movement, a nationwide nonviolent demonstration demanding Korea’s independence from Japan. The brutal Japanese response to this movement and the largely mistaken belief that the Japanese were specifically targeting Korean Christians led to an outpouring of sympathy in the US and around the world.

Savvy Korean nationalists in the US, many of them Christians, lobbied hard to convert this sympathy towards Korea into support for its independence. They also cleverly included alleged American violations of the 1882 Treaty in their lobbying, accusing American diplomats of regarding treaties as just “mere scraps of paper” – the same accusation American policymakers made against Germany to partially justify the American entry into World War I. These lobbying efforts resulted in a great deal of media attention on Korea, and even injected Korea as an issue into the debate over the Versailles Treaty in the US Senate. In March 1920, a reservation to the Versailles Treaty obligating the US to recognize Korea’s independence fell just six votes short of passing.Footnote 4 By 1921 Korean activists in the US could claim some remarkable successes in their efforts to interest Americans in Korea’s independence, but they could not change American policy, which still recognized Japan’s colonization of Korea, albeit with perhaps greater misgivings than in 1904.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and the American entry into World War II reopened the question of American policy towards Korea. Korean activists, led by Rhee, cleverly exploited the explosion of anti-Japanese sentiment and the increasing belief that the US had made a mistake by “appeasing” Japan in Korea in 1904. Their arguments about a “Christian Korea” and allegations of violations of the 1882 Treaty still resonated. In this environment they were more successful. In the 1943 Cairo Declaration, the US and other allies pledged that after the defeat of Japan, Korea would be decolonized and made independent “in due course.” However, inter-allied rivalry over the future of Korea and postwar “decolonization” (what would happen to British colonies?) as well as factionalism within the Korean independence movement abroad meant that few concrete actions were taken to put the Cairo Declaration into practice.

In the summer of 1945, as Japan’s defeat seemed increasingly certain, Korean activists, American missionaries, and US congressmen all demanded that the Truman administration take concrete action to guarantee Korea’s future independence. Korean allegations that the late President Franklin Roosevelt had made a “secret treaty” at the Yalta Conference giving the Soviet Union control of Korea in exchange for entry into the war against Japan angered Americans who, based on Stalin’s actions in Eastern Europe, were becoming more and more distrustful of Soviet intentions in East Asia. This coalition, made up of Americans genuinely interested in Korea and those deeply skeptical of the Soviet Union, placed political pressure on the Truman administration to act, as did the belief that a truly independent Korea would likely lead to a more stable East Asia.Footnote 5

However, any coherent American policy was overtaken by events when the Soviet Union entered the war with Japan on August 8 by invading Manchuria and the Korean peninsula just before the Japanese surrender. Since the nearest American forces were still weeks away in Okinawa, it seemed all but certain that Korea would be occupied by the Soviet Union. To avoid a unilateral Soviet occupation of Korea, the Truman administration suggested a joint occupation, with the 38th parallel serving as the boundary between the Soviet and American zones. The Soviets could have easily refused the suggestion, but they accepted it without comment, hoping the Truman administration would agree to a Soviet presence in occupied Japan, a request that was not granted.

One of the ironies of Korea’s division is that although the Truman administration cared enough about the fate of Korea to suggest a joint occupation, it refused to make any long-term commitment to its independence or security. This is partially attributable to disagreements within the administration over Korea’s value to the US. Although the selection of the 38th parallel as a dividing line between the two occupations was made by two American colonels, the decision was driven by political not military leaders. American generals protested that Korea had no strategic value and that almost no planning had been done for its occupation. Though General Douglas MacArthur was nominally in command of the occupations of both Japan and southern Korea, he stubbornly refused to take responsibility for Korea, telling aides, “They [the Truman State Department] wanted Korea and got it … I wouldn’t touch it with a ten-foot barge pole.”Footnote 6

Unsurprisingly, the American occupation of southern Korea did not go well. Because hardly any advanced planning had been done, it was not until four months into the joint occupation (December of 1945) that American and Soviet diplomats agreed to a common policy on Korea: an international trusteeship possibly lasting five years. Even those Koreans identified as “pro-American” were violently opposed to trusteeship and demanded immediate independence. Making matters worse, the US and the Soviet Union could not agree on which Koreans should be invited to participate in the trusteeship process. The Soviets insisted that only those supportive of trusteeship could participate, a condition that would have excluded all but a minority of Koreans. The US insisted on much broader participation, even to include those opposed to trusteeship. US–Soviet negotiations broke down on this point.

Attempting to break the impasse in 1947, the Truman administration brought the issue of Korea to the newly created United Nations (UN). A solution in the form of UN General Assembly Resolution 112 (II) was passed unanimously (with six abstentions) on November 13, 1947. This resolution created a UN commission to oversee the election of a unified Korean National Assembly that would subsequently create a united national government for Korea. The resolution also called for the withdrawal of all occupying forces from the peninsula after this government was created.Footnote 7 Unfortunately for the hopes of a unified Korea, Soviet occupation forces would not allow UN officials to enter northern Korea and so elections were held in the American zone only, resulting in the creation of the Republic of Korea on August 15, 1948. The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea was proclaimed on September 9, 1948, outside of any UN or international process.

While many parties, including the Koreans themselves, contributed to the division of their country becoming permanent, there is a tendency among Koreans to view the US as particularly responsible. A 2005 poll conducted by the Korean Society Opinion Institute found that 53 percent of South Koreans considered the US mainly responsible for the division of Korea, while only 14 percent believed the Soviet Union was mainly responsible.Footnote 8 One can only imagine that if the same poll were conducted in North Korea, the percentage of North Koreans believing the US was responsible would be significantly larger.

This perception exists for two reasons. First, while the joint occupation of Korea did not make the creation of two separate states inevitable, it was a necessary condition for this development, and it was an American, and not a Soviet or Korean, idea. Second, many Koreans feel that the US expedited the creation of a separate state in the south to extricate the US from a mess of its own making, rather than staying engaged until Korea could be reunified. The counterpoints to this are that while the joint occupation was an American suggestion, it was never supposed to be permanent, and that the creation of the ROK was widely supported by many Koreans who believed that if they could not have unification, they should at least have independence and the end of the American occupation. However, while historians can debate the accuracy of the perception that the US is largely responsible for Korea’s division, the perception exists and colors US–Korean relations to this day.

An Evolving Alliance: US–ROK Relations since 1948

Any general characterization of the US–ROK alliance over its nearly seventy-year history is difficult because of the way its purpose and value have evolved. Initially it was not an alliance the US wanted. If the division of Korea in 1945 was an American idea that was resisted by Koreans, the US–ROK alliance was a Korean idea that Americans resisted for years, with disastrous consequences.

Following the creation of the ROK, American forces began preparing to withdraw over the objections of the ROK government, which they did in July 1949, leaving behind just a small force of military advisers to the nascent ROK Army. Realizing an American departure from Korea was inevitable, the ROK sought explicit security guarantees from the US, preferably in the form of a treaty. Although analysts in the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and virtually all knowledgeable Koreans warned that an American withdrawal without explicit security guarantees might lead to a North Korean invasion, American military leaders discounted this possibility.Footnote 9 National Security Council documents indicate the Truman administration believed that the ROK was a strategic liability and wanted to leave the peninsula before any situation arose that might facilitate a longer US commitment.Footnote 10

The American departure facilitated just such an unwanted commitment when the DPRK invaded the ROK on June 25, 1950, in a bid to reunite the peninsula under the leadership of Kim Il-sung. Kim was convinced the Americans had abandoned the ROK, and launched his invasion with the support of Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong. To his surprise, the same American policymakers who just a year before had supported the withdrawal from the ROK now supported military intervention, based on the belief that the invasion was being orchestrated by the Soviet Union and that failure to resist such aggression might lead to further Soviet adventurism.Footnote 11

The Truman administration committed American airpower to defend the ROK immediately. It further sought support in the UN Security Council to resist the invasion, which was quickly granted, but armed intervention took time to organize and deploy. The first American forces rushed to the peninsula to bolster the retreating ROK Army fared badly as they were ill prepared and ill equipped. However, they slowed the North Korean advance and kept the strategic port of Busan open as a resupply and staging area for the American-led United Nations Command (UNC, comprising armed contingents of fifteen other UN member states).Footnote 12

North Korean strategy had relied on the element of surprise and a rapid advance. Kim Il-sung gambled that he could defeat the ROK and unite the Korean peninsula before any foreign intervention could be mobilized. The failed all-out assault on the Busan perimeter left North Korean forces vulnerable to a counterattack and gave the UNC time to plan an amphibious landing at Incheon, a port city just east of Seoul and halfway up the Korean peninsula. Tidal variation at Incheon made landing there extremely risky, but because nearly all North Korean forces were still heavily engaged in fighting near Busan, the UNC landing was largely uncontested.

The Incheon landing broke the North Korean offensive and began a new stage in the war. Threatened with entrapment between UNC forces in Busan and those cutting across the peninsula near Seoul, North Korean forces began a hasty and disorganized retreat back across the 38th parallel. More than half of their invasion force of 70,000 was killed or captured in the process, leaving the DPRK vulnerable to an ROK and UNC counterinvasion. Invading the DPRK to reunite the Korean peninsula was an opportunity too enticing for either Rhee or UNC Commander Douglas MacArthur to resist. On September 30 the first ROK troops crossed the parallel, with UNC forces closely following. Although UN General Assembly Resolution 376 (V) provided the invasion of the DPRK with a fig leaf of international legitimacy, the decision was controversial, in that UN forces originally sent to resist the reunification of Korea by force were redirected to accomplish the same thing, albeit in the service of the ROK.Footnote 13

The UNC invasion of the DPRK was almost a mirror image of the DPRK invasion of the ROK. UNC forces sped up the Korean peninsula meeting little resistance from a dispirited North Korean army. However, in their haste to reach the Yalu River and reunite the peninsula, UNC forces became overextended and vulnerable to flanking attacks from Chinese forces that, unbeknown to most UNC commanders on the ground, had already penetrated deep into North Korea. Chinese leader Mao Zedong had decided to intervene when the UNC forces crossed the 38th parallel. On November 25 a massive Chinese counterattack across northern North Korea caught the UNC by surprise. Chinese forces had penetrated so deeply into North Korea that they were often able to cut off UNC escape routes to the south. The UNC was forced to make a hasty retreat and by late December 1950, the Chinese and what was left of the North Korean Army had retaken Seoul. American forces would regroup and counterattack in March 1951, recapturing Seoul and pushing the combined Chinese and North Korean forces back near the 38th parallel, where the fighting reached a stalemate.

The Korean War would prove much easier to start than to finish. What began as a North Korean attempt to reunify the peninsula transformed into a proxy war in which the world’s most powerful militaries backed opposite sides: the US and UNC allies supporting the ROK and the Chinese supporting the DPRK – with some Soviet assistance. Since the fighting had come to a stalemate with both Korean states intact, there was virtually no hope of a peace treaty that would solve the underlying issue of the unification of Korea. Instead, Chinese, North Korean, and American leaders (representing the UNC) began negotiating an armistice in 1951. ROK President Syngman Rhee refused to participate in the negotiations, even actively sabotaging them, in the hope that the war would continue until Korea was reunified.Footnote 14

An armistice was concluded in July 1953. This agreement established a cease-fire, created a demilitarized zone (DMZ) between the ROK and the DPRK, and called for a “political conference” to be held within three months to “settle through negotiation the questions of the withdrawal of all foreign forces from Korea, the peaceful settlement of the Korean question, etc.”Footnote 15 Unsurprisingly, the subsequent political conference held in Geneva, Switzerland, in July 1954 did not bring any resolution to the Korean question, but the armistice held and all sides were forced to recognize that the division of Korea would continue indefinitely.

For all Korean nationalists, this was a terrible blow. Rhee refused to sign the armistice agreement, and for the rest of his tenure as ROK president occasionally threatened to restart the war. However, Rhee offered to tacitly abide by the armistice in return for a mutual defense treaty with the US. American policymakers long resisted an alliance with the ROK. This was partly out of spite for Rhee, whose pressure tactics during World War II had alienated many in the US government, and partly out of a genuine desire to minimize their commitments to the ROK. Secretary of State Dean Acheson repeatedly rejected the idea of a mutual defense treaty, telling the ROK ambassador that the “tremendous sacrifice” the US was making in Korea should be sufficient reassurance and that the security of the ROK would not be improved “merely by a paper indication of such resolve.”Footnote 16 But Rhee was insistent. As one of the original envoys sent to the US to meet Theodore Roosevelt in 1904 and as one of the chief architects of Korean lobbying in the 1940s using the 1882 Treaty, Rhee understood the value of treaties – even broken ones.

Ultimately, Rhee had his way. The US–ROK mutual defense treaty was ratified in October 1953. Its origins were inauspicious. It was a grudging American concession to the ROK in return for Rhee’s tacit pledge to abide by the armistice agreement ending the Korean War. For several decades the alliance was hardly something idealistic Americans could be proud of. Economic mismanagement, corruption, and the refusal to normalize relations with Japan until 1965 kept the South Korean economy from growing and the ROK government dependent on American economic as well as military aid. The ROK’s politics were not much better. From 1948 to 1988, the ROK was ruled by a succession of authoritarian leaders. They placed severe restrictions on the press and individual rights, including denying most of their citizens the right to travel abroad, and maintained a feared internal police force. Successive American administrations did place some, usually quiet, pressure on the ROK to reform and liberalize, but were unwilling to take truly vigorous action in support of Korean democracy.

Perhaps predictably, several American presidents sought to reduce the costs of this alliance. In 1971 the Nixon administration ordered the withdrawal of 20,000 American troops from South Korea as part of a broader policy of encouraging allies in the region to bear a greater proportion of the cost of their own defense. President Jimmy Carter ordered his administration to seek the withdrawal of all combat troops from the ROK in 1976 while criticizing the authoritarianism of ROK President Park Chung-hee. These policies renewed ROK fears of abandonment and prompted Park to begin a surreptitious nuclear weapons program. Such a program could be used either to trade for enhanced American commitments or to bolster the ROK’s deterrence should American guarantees be withdrawn.Footnote 17 Opposition in the State and Defense Departments, as well as Congress, thwarted Carter’s attempt to withdraw troops, but the revelation of the “Koreagate” scandal – in which agents of the South Korean government made illicit payments to US congressmen in the hope that they would oppose Carter’s policy – added to the acrimony of this particular moment in US–ROK relations.Footnote 18

The assassination of Park Chung-hee in October 1979 by his own intelligence chief, and the belief that Carter’s policies might have contributed to the assassination, caused a reevaluation of the relationship in both Seoul and Washington. Park’s successor, Chun Doo-hwan, sought improved relations with Washington by ending the ROK’s nuclear weapons program and by reorienting some of the ROK’s defense strategy away from indigenous development and towards purchasing American armaments and technology. The incoming Reagan administration reciprocated by inviting Chun on a state visit to Washington, pledging no reductions in US troop numbers, and limiting its public criticism of the ROK’s human rights violations.

The end of the Cold War might have reopened debates about an American troop presence in the ROK, had the DPRK’s nuclear weapons program not focused American minds on a new type of threat on the peninsula and precluded talk of reducing American commitments to the ROK. The ROK’s rapid economic development that started in the 1980s and its transition to a genuine democracy in the early 1990s also shifted perceptions of the alliance from being a patron–client relationship in which the US defended South Korea from North Korea, into a partnership based on shared interests between similar – if unequal – states.

The political and economic development of the ROK caused its own stresses on the alliance in the late 1990s and 2000s, however. Freedom of speech and of the press allowed Koreans to interrogate their country’s authoritarian past and caused many to be critical of the role the US played in supporting Korean strongmen with aid while only weakly calling for reforms. The American culpability for civilian casualties during the Korean War and during the 1980 Gwangju Uprising have also been occasional flashpoints for anti-American sentiment.Footnote 19

Other developments also sparked tension. The 1997 International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailout of the ROK, with its imposed reforms, and the negotiation and implementation of the United States–Korea Free Trade Agreement (KORUS FTA), 2006–2008, both sparked massive anti-American demonstrations. Many Koreans interpreted these two episodes as American attempts to force open the ROK economy to American competition on unequal terms. The American troop presence in the ROK also resulted in occasional tensions. When two Korean schoolgirls were struck and killed by an American military vehicle in 2002, massive anti-American protests erupted throughout the country and polls briefly showed Korean popular opinion equally split on whether US forces should withdraw.Footnote 20 During this period, South Korean anti-Americanism became significant enough that some observers wondered if it might pose a fundamental threat to the alliance.Footnote 21

By contrast, US–ROK relations between 2008 and 2016 were relatively uneventful. The continued evolution of North Korea’s nuclear weapons program precluded any discussion of troop withdrawals. Opposition to the KORUS FTA died out when it became clear the deal would neither flood the ROK with American products, nor sicken Koreans with allegedly tainted American beef.Footnote 22 Friction between US servicemen and Koreans was also reduced by a base relocation plan that closed dozens of American installations, including those in the center of Seoul, and relocated personnel to the newly built Camp Humphreys in Pyeongtaek, south of Seoul.

The tranquility of this period seemed to indicate that the US–ROK alliance had reached maturity. Korean fears of abandonment and exploitation had abated. The alliance had broadened its scope of cooperation beyond peninsular security to include regional stability, trade, and a shared vision of international relations governed by a rules-based order. The ROK has been a regular contributor of resources to American-led security operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, and off the coast of Somalia, among other places. If the ROK were a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), its defense spending as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) would likely only trail that of the US, having not dropped below 2.3 percent since the 1960s.Footnote 23 Although most American policymakers wisely refuse to define the US–ROK alliance as being opposed to China, it is American assets in the ROK (and Japan) that make the US a regional power in East Asia.

Beyond military ties, cultural exchange has also become a hallmark of the alliance. Since 2001, the ROK trails only India and China in the number of international students it sends to the US for an education (1.1 million), despite having a population that is more than twenty-five times smaller than India’s. Although the fees these students pay are not traditionally thought of as “exports,” they constitute a trade of perhaps even more fundamental value, in which financial resources flow into the US, knowledge of American culture and society flows back to the ROK, and lasting social connections are established.Footnote 24

Despite the obvious evolution in the value of the US–ROK alliance, the Trump administration attacked it at its very foundation. As a candidate and president, Donald Trump criticized this alliance as a “terrible deal” in which the US defended the ROK but received little in return, and accused the ROK of “free-riding” on American security. The Trump administration’s insistence on a “cost plus” formula at alliance cost-sharing negotiations with the ROK in 2019 only added insult to injury. Presidential musings on withdrawing all troops from the ROK reopened Korean fears of abandonment. His administration’s linkage of security and trade policy by demanding that the ROK renegotiate the KORUS FTA or face reduced American commitments reawakened South Korean angst about American economic exploitation.

This zero-sum understanding of the alliance not only failed to appreciate the way it evolved in beneficial ways for both states, but also failed to understand why the alliance was necessary in the first place. Had it not been for the American decisions to suggest the joint occupation of Korea in 1945 and then to withdraw from Korea prematurely in 1949, the division of Korea and the Korean War would have been avoided. Regardless of whether the US–ROK alliance is a “terrible deal” for the US, it was seen by many Koreans as a natural consequence of decisions made in Washington. The alliance was a pledge made by the US to remain committed to the ROK’s defense until the mess brought on by the division of the Korean peninsula was resolved. In this way, Trump’s policies towards the ROK not only escalated tensions in the present, but also reopened historical wounds that had never completely healed.

Professionals and Entrepreneurs: US Relations with the DPRK since 1948

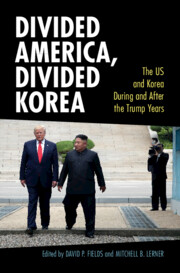

Donald Trump’s three meetings with North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un were some of the most memorable moments of his presidency. This was Trump as he wanted to be seen: the iconoclastic leader who could use unconventional means to solve problems that more conventional leaders could not.

These meetings were indeed historic firsts, in the narrow sense that no sitting president had ever met with a North Korean leader before. However, a careful examination reveals that, far from being sui generis, Trump’s approach to North Korea was just the latest example of what some scholars refer to as “entrepreneurial diplomacy,” in which individuals attempt to foster breakthroughs in US–DPRK relations using unconventional means and outside of normal diplomatic channels. Such entrepreneurial diplomacy is common in this relationship because the US and the DPRK have never had formal diplomatic relations. This lack of formal relations long predates the DPRK’s pursuit of nuclear weapons and even predates the Korean War. Just as the purpose and the nature of the US–ROK alliance have evolved over time, the enmity between the US and the DPRK has also evolved and its origins have become obscure.

From its very inception the DPRK has faced diplomatic isolation. Since it boycotted the UN’s effort to reunite Korea via peninsula-wide elections in 1948 (the process that created the ROK), few countries outside of the Soviet sphere of influence and communist China recognized it. This thwarting of the UN likely contributed to the speed with which the UN backed the American intervention to save the ROK in 1950. Because the Korean War never officially ended, nonrecognition of the DPRK became the de facto stance of many states even long after the fighting ceased.

The DPRK did little to ease its own isolation during the subsequent decades. In the late 1960s, it took concerted action to foment a revolution within the ROK that it hoped would enable reunification under Kim Il-sung. These actions included the infiltration of commandos into the ROK, the attempted assassination of ROK President Park Chung-hee, the hijacking and subsequent kidnapping of South Korean citizens, and attacking US military assets in the region, especially the USS Pueblo.Footnote 25 Because of the concentrated nature of this aggression, some have referred to the 1967–1969 period as the “second Korean War.” Such episodes continued sporadically into the 1970s and 1980s, including several assassination attempts against ROK leaders, the 1983 Rangoon bombing that killed more than twenty people, and the bombing of Korean Air Lines flight 858, which killed 115 people over the Andaman Sea in 1987.

The ROK was not the sole target of North Korean terrorism and criminal activity. In the 1970s as North Korea normalized relations with several European countries, it placed large orders on credit for everything from cars to industrial equipment, which it subsequently refused – or was unable – to pay for.Footnote 26 The issues stemming from these defaults, combined with Korean War-era sanctions imposed by the US, kept North Korea isolated from much of the international financial system in the 1970s and 1980s. In response, the DPRK frequently used its embassies abroad and the immunity afforded to their diplomats to engage in illicit activities.Footnote 27 Kim Jong-il’s admission in 2002 that North Korea had abducted a dozen Japanese citizens in the 1970s and 1980s to serve as language teachers for North Korean spies (and that eight of the twelve were dead), confirmed North Korea’s involvement in human trafficking and aroused suspicions that Japanese citizens were not the only targets.

North Korea’s violations of the human rights of its own citizens are also well known, even if the secretive nature of the Kim regime makes gathering precise data difficult. Estimates of the number of political prisoners being held in North Korean forced labor camps range from 80,000 to 200,000. Despite basic human rights ostensibly being guaranteed in the North Korean constitution, in practice North Koreans do not enjoy freedom of speech, religion, the press, or movement. Freedom House, a nongovernmental organization that conducts research on human rights, political freedom, and democracy, gave North Korea three points out of one hundred in its 2021 “Freedom in the World Report,” among the worst scores globally for a country that is not an active combat zone.Footnote 28 In 2014, a UN commission of inquiry concluded that human rights violations in North Korea were sufficiently severe to be considered “crimes against humanity” and that “the gravity, scale and nature of these violations reveal a State [sic] that does not have any parallel in the contemporary world.”Footnote 29

North Korea’s willingness to engage in terrorism abroad and repression at home kept it isolated from the international community, but it was more an object of loathing than of fear. This began to change in 1993, when the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) concluded that North Korea was no longer in compliance with the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), which it had joined in 1985 – North Korea had been conducting nuclear research since the early 1960s. The IAEA’s conclusion resulted in a UN Security Council Resolution condemning the DPRK, and the Clinton administration seriously considered a military strike on North Korean nuclear facilities. At the last minute, former President Jimmy Carter flew to Pyongyang as a private citizen at the personal invitation of Kim Il-sung to seek a solution. Their meeting opened talks that resulted in the 1994 Agreed Framework in which the DPRK agreed to freeze its nuclear weapons program and permit IAEA inspections in return for the construction of proliferation-proof, light-water nuclear reactors and aid in the form of fuel shipments.

The Agreed Framework was the most comprehensive attempt to date to solve the North Korean nuclear issue. However, partisan infighting within the US government delayed and reduced fuel shipments to North Korea and put the construction of the light-water reactors years behind schedule. Opponents to the deal were motivated by partisanship, but also by the hope that North Korea might soon collapse. The loss of economic aid from the Soviet Union in 1990, the death of Kim Il-sung in 1994, and a prolonged period of famine from 1994 to 1998 – known as the Arduous March in North Korea – seemed to push the DPRK to the breaking point. North Korea’s wretched human rights record also made appropriating money for aid distasteful for many congressmen. Although not prohibited by the 1994 agreement, North Korea’s tests of intermediate-range missiles in 1998 did not help build trust between the two sides.

The Agreed Framework broke down between 2002 and 2006, with the DPRK accusing the US of failing to deliver the agreed levels of aid (which was true) and the US accusing the DPRK of secretly starting a highly enriched uranium program (also true). The Bush administration’s decision to label North Korea as part of the “Axis of Evil” in the 2002 State of the Union Address only reinforced the perception that the US was not fully committed to the deal. North Korea withdrew from the NPT in 2003 and conducted its first nuclear test in October of 2006. Between 2009 and 2017, it conducted five additional tests. These tests have been condemned by the UN Security Council and other international bodies, and calls for the DPRK to return to negotiations have been constant. A few deals, such as the 2012 “Leap Day Agreement,” have been struck, but none has been as comprehensive, nor lasted as long, as the 1994 Agreed Framework.

Despite little positive change in North Korea’s behavior over time – in just the last decade it has shelled a South Korean island, sunk an ROK Navy warship, used chemical weapons to assassinate Kim Jong-un’s half-brother in Malaysia, and stole eighty-one million dollars from a Bangladesh bank, in addition to conducting four nuclear tests – its diplomatic isolation has actually decreased. There are 164 states that have now established formal diplomatic relations with the DPRK, including the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, and Spain, all NATO allies of the US.Footnote 30 Their doing so is a tacit acknowledgment that isolation has not proven to be an effective means of modifying North Korean behavior.Footnote 31 Still, the ROK, Japan, France, and the US have remained firm in their opposition to normalizing relations with the DPRK without modifications to its behavior including, at the very least, a dismantling of its nuclear weapons program.

The irony of the American policy of not talking to North Korea is that North Korea and the US have so much to talk about. From a formal end to the Korean War, to the repatriation of the remains of American servicemen killed in the conflict, to the return of the USS Pueblo, to the dismantling of North Korea’s nuclear weapons program, many American foreign policy goals related to the Korean peninsula and the region can best be advanced through genuine dialogue with North Korea. Since 1948, any dialogue has been sporadic, and genuine dialogue absent.

Into this void has stepped a diverse array of diplomatic “entrepreneurs” ranging from televangelists, to professional athletes, to BBQ chefs, to US congressmen. Their engagement with North Korea follows the same general pattern: They lament the decades of nonrelations between the US and the DPRK, claim that major changes in the relationship are possible, and offer themselves as the catalyst to jumpstart genuine dialogue.

Billy Graham’s engagement with North Korea, since continued by his son Franklin, is a case in point of how this entrepreneurial diplomacy works. After his first visit to North Korea in 1992, Graham predicted that change in North Korea was just around the corner and that the DPRK was “reaching out toward other nations for some friend.”Footnote 32 For the next 30 years, goodwill and aid, via Franklin Graham’s humanitarian organization, Samaritan’s Purse, flowed to North Korea, despite the hoped-for changes never materializing. As recently as 2018, Franklin Graham maintained that engagement with North Korea would foster greater religious freedom in the country, despite no progress being made on this issue in the last thirty years.Footnote 33

While the Grahams’ engagement has not resulted in any discernible changes in North Korean behavior or improved relations between the US and the DPRK, it has been good for the Grahams and their organizations. Their engagement with North Korea has provided the Graham family with a continued global platform, much the way Billy Graham’s visits to the Soviet Union did during the Cold War. Franklin Graham’s humanitarian trips to North Korea generate extensive coverage – Fox News correspondent Greta Van Sustern is a regular traveling companion on these trips. It has also been good for the North Koreans, as Samaritan’s Purse has given at least $10 million in aid to North Korea since 1997.Footnote 34

The same has been true of the efforts of New Jersey BBQ chef Robert Egan and former NBA star Dennis Rodman. Though their engagement with North Korea was neither as long nor, it must be said, as high-minded as that of the Grahams, it followed the same pattern. Both men decried the lack of US engagement with North Korea and offered themselves as just the type of unconventional diplomats that could foster a breakthrough. In both cases the breakthrough proved to be illusory, but their efforts did result in momentary fame for Egan – including a profile in the New Yorker – and a prolonged period in the celebrity spotlight for Rodman.Footnote 35

Benefits also flowed to North Korea. Dennis Rodman’s visits to North Korea allowed the regime to present a much different image of Kim Jong-un to the world – a genial and basketball-loving young leader, who was perhaps more open to dialogue than either his father or grandfather. As Egan details in his book Eating with the Enemy, the North Korean diplomats he befriended took full advantage of his entrepreneurial diplomacy, not only eating hundreds of meals for free at his restaurant, but also using him as an unpaid fixer for dozens of projects, from organizing shipments of aid to the DPRK (including Viagra) to orchestrating several visits to Pyongyang by American businesspeople. In one of the more bizarre elements of an already bizarre story, Egan convinced the late Pennsylvania State Senator Stewart Greenleaf to make several trips to North Korea to deliver aid and to personally attempt to negotiate a return of the USS Pueblo to the US.Footnote 36 Greenleaf apparently agreed with Egan that visits to Pyongyang were just what the senator needed to raise his profile in preparation for a run for governor of Pennsylvania. While these antics did get Greenleaf briefly mentioned in the New York Times, they were not the headline generators he was hoping for and his run for governor never materialized.Footnote 37

Greenleaf was not the only American legislator to see entrepreneurial possibilities in visits to North Korea. According to a study by Terence Roehrig and Lara Wesel, there have been dozens of entrepreneurial congressional visits to North Korea since 1980. The varying nature of each visit makes general conclusions difficult, but Roehrig and Wesel note that these “visits appeared to lessen, somewhat, the tension between the two governments and encouraged continuing dialogue, though, in the end, they were unsuccessful in achieving a final solution.” If this conclusion is correct, it is easy to understand North Korean support for such entrepreneurial diplomacy, which consistently lessens tensions and urges continued dialogue without resulting in changes in North Korean behavior. It is worth noting that former President Jimmy Carter’s visit to Pyongyang in 1994 – perhaps the highest-profile example of entrepreneurial diplomacy with North Korea prior to 2018 – was made after three years of repeated requests from Kim Il-sung.Footnote 38

What do the entrepreneurial congressmen get out of these visits? Roehrig and Wesel conclude that “Congressional visits received both national and international media coverage,” allowing the congressmen to play a role in shaping US policy towards the DPRK. While shaping US policy was surely a motive, few congressmen could fail to realize the value of the media coverage their efforts received, even if they ultimately failed.Footnote 39

Of course, such entrepreneurial diplomacy is not the only type of interaction between the US and the DPRK. American and North Korean diplomats have not infrequently gathered at Panmunjom in the DMZ, on the fringes of the UN General Assembly in New York, and in places like Stockholm and Geneva to exchange carefully worded policy statements in fruitless attempts to mediate the fundamental challenge the DPRK poses to the rest of the world: North Korea wants all the benefits the international community bestows on member states, without following many of the norms of that community – including those around nuclear weapons and human rights. Until the DPRK gives some concrete indications that it is willing to change its behavior, there is little hope of genuine dialogue between the two states. Professional diplomats understand this and so proceed with caution and rarely seek the limelight.

There are then two traditions in American diplomacy towards North Korea: the cautious approach preferred by the professionals and the opportunistic approach pursued by the entrepreneurs. The professionals approach North Korea with a measured wariness, knowing that success is unlikely. The entrepreneurs approach North Korea with enthusiasm, knowing that engaging with the DPRK will result in media attention even if it fails. Engagement is thus an end in itself.

Trump’s approach to North Korea was squarely in the entrepreneurial tradition. He claimed as a presidential candidate that he would be willing to have a burger with Kim Jong-un, decried professional diplomats as “fools,” and labeled former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton as a “rank amateur” who despite years of diplomatic experience “still doesn’t get it” for stating that she would not meet with Kim Jong-un without preconditions.Footnote 40

To be sure, there were aspects of Trump’s approach that were distinct from other entrepreneurs. No entrepreneur could have engaged in his war of words with Kim Jong-un in the fall of 2017 and spring 2018. His pledge to meet continued threats from Kim with “fire and fury” and his bragging about the size and potency of his “nuclear button” compared with Kim’s appeared to escalate tensions to dangerous levels. However, it is tempting now to see this war of words as something of a set-up for Trump’s entrepreneurial approach. As a former national intelligence officer has recently commented, “There was a very large gap between the rhetoric and the activity in 2017.”Footnote 41

And so it proved. Just a month after his “nuclear button” tweet, Trump dispatched Vice President Mike Pence to meet secretly with the North Korean delegation to the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympics, though the meeting was canceled at the last minute.Footnote 42 However, less than two weeks later Chung Eui-yong, the ROK’s Director of the Office of National Security, visited the White House with a message from ROK President Moon Jae-in that Kim was committed to denuclearization and wanted to meet with President Trump.

Trump’s acceptance of the invitation shocked and dismayed many members of his administration, none more so than National Security Adviser John Bolton, whose 2020 memoir sheds valuable light on Trump’s approach to North Korea. From the beginning few of Trump’s aides believed that Kim’s pledge was genuine, but Trump seemed uninterested in Kim’s sincerity and instead was fixated on the media coverage. According to Bolton, in the run-up to the Trump–Kim summit in Singapore in June 2018, Trump told Moon to remind the South Korean media how responsible Trump was for the new thaw in relations with the DPRK, and also told Bolton to praise him more on the American Sunday-morning talk shows because “There’s never been anything like this before.” Bolton recounts too how Trump, not wanting to miss a single media opportunity, rushed to Andrews Air Force Base at 3:00 am on May 10 to welcome back three American citizens who had just been released by Kim Jong-un after a visit from Mike Pompeo, then still CIA director. President Trump made the three hostages wait in the plane, and Pompeo wait at the bottom of the gangway, so that he could briefly enter the aircraft and emerge with the hostages as if he had been the one who recovered them. According to Bolton the whole event left Trump on “cloud-nine” since this was a “success even the hostile media could not diminish.”Footnote 43

The weeks preceding the Singapore Summit were anything but smooth. The North Korean Foreign Minister called Vice President Pence “stupid and ignorant” for making comparisons between North Korea and Libya, North Korean negotiators at the DMZ refused to permit the word denuclearization on the summit agenda, and the North Korean advance teams failed to show up in Singapore on the agreed date. There was so much uncertainty, Trump even canceled the summit on May 24 before “uncanceling” it hours later. He reportedly told aides he was unsure whether Kim would agree to denuclearization at the summit, but “I [Trump] want to go. It will be great theater.”Footnote 44

A theatrical performance was the primary lens through which Trump saw his diplomacy towards North Korea. A week before the Singapore Summit, Bolton was astounded to learn that Trump wanted to declare an end to the Korean War without seeking any concession from the North Koreans in return. “He thought it was just a gesture, a huge media score,” wrote Bolton.Footnote 45 On learning from Secretary of State Pompeo after landing in Singapore that the two advance teams had come to an impasse in their negotiations over a joint statement, Trump was unconcerned, telling Bolton “This is an exercise in publicity” and that the summit would “be a success no matter what.”Footnote 46

The Hanoi Summit followed a similar pattern. On his way to meet Kim, Trump reportedly asked aides what would be the “bigger story,” a small deal with Kim or walking away. Bolton assured Trump the latter would be the bigger story. Trump apparently concurred. When Kim made clear only a small deal was on offer, closing the Yongbyon nuclear facility in return for the lifting of all post-2016 sanctions, Trump walked away. As the two leaders parted, Trump offered to give Kim a lift back to Pyongyang on Air Force One. When Kim refused – much to the relief of the president’s aides – Trump lamented what a photo that would have made.Footnote 47 Even in failure, Trump saw an opportunity for self-promotion.

It would be easy to dismiss Bolton’s account of the Singapore Summit and Trump’s approach to North Korea as the slander of a dismissed adviser, if it were not corroborated by Trump himself in several interviews with Bob Woodward for his 2020 book Rage. Trump seemed incapable of discussing his diplomacy towards North Korea without referencing the media it generated. When Woodward asked why he had pivoted from the “fire and fury” rhetoric to meeting Kim, Trump embarked on a long digression about how the US was “losing a fortune” defending the ROK. When Woodward steered the conversation back towards the Singapore Summit, Trump proclaimed, “You know it was the most cameras…. There’s like hundreds of them. It’s free. I get it for free. It costs me nothing. It’s called earned media.” Trump went on a bit longer about the “monster” media event in Singapore before calling on aides to bring Woodward photos of the summit – as if he had not seen them before.Footnote 48 Trump’s behavior was similar in another interview in which Woodward asked about his third meeting with Kim at the DMZ in June 2019. Trump again called for aides to bring in pictures, adding “you know, when you talk about iconic pictures, how about that?”Footnote 49

When Woodward was able to bring Trump’s focus “away from the PR extravaganza” that was his North Korea diplomacy and towards the substance of the meetings, Trump’s views were equally revealing. Trump had his own misgivings regarding Kim’s commitment to denuclearization throughout the process: “It’s really like, you know, somebody that’s in love with a house and they just can’t sell it.”Footnote 50 Trump further explained that at the Hanoi Summit he knew instinctively that Kim was not ready to make a deal, and so after a few fruitless minutes of negotiating asked Kim, “Do you ever do anything other than send rockets up to the air? Let’s go to a movie together. Let’s go play a round of golf” – two activities that would have yielded more “historic” photos, but were unlikely to change the fundamentals of the situation.Footnote 51

Trump engaged in high-level summitry with North Korea despite his own misgivings that his efforts would result in any breakthroughs. This was acceptable to Trump because, like other entrepreneurial diplomats, a breakthrough was not his only motivation. The engagement itself, even if it accomplished little of lasting value, was valuable to him in terms of free publicity alone.

As president, Trump was in a position to maximize the benefits of his entrepreneurial diplomacy, since he could control the media narrative surrounding it to a certain degree. Unlike other entrepreneurial diplomats who have engaged North Korea claiming that a breakthrough was possible, Trump could claim that a breakthrough had actually occurred after his first meeting with Kim Jong-un in Singapore, telling Americans to “sleep well tonight” since North Korea was no longer a threat.Footnote 52 Trump continued to claim a breakthrough had taken place, even as working-level negotiations between the US and DPRK remained unproductive. The breakthrough was that his “good relationship” with Kim Jong-un had kept the US and North Korea from going to war, which Trump repeatedly claimed former President Obama told him was likely in 2016. The Trump–Kim relationship and “No war with North Korea” were repeatedly trotted out by President Trump in 2020 as foreign policy accomplishments, especially in his final presidential debate with then Senator Joseph Biden.Footnote 53 On December 11, 2020, in one of his final tweets related to North Korea, Trump listed “No war with North Korea” as a major accomplishment, in response to a tweet from a supporter arguing that President Trump was more deserving of a Nobel Peace Prize than President Barak Obama. Not going to war with North Korea was clearly a wise policy choice, but since every president since Harry Truman has made that same decision, Trump’s basis for claiming it was a breakthrough and a major accomplishment does not stand up to scrutiny.

The “unprecedented” label of Trump’s approach to North Korea thus needs to be taken with some skepticism. He truly pursued policies that no previous president had attempted, but his diplomacy clearly resembled the strategies pursued by entrepreneurial diplomats before him, which were as much aimed at media attention as they were unlikely breakthroughs. It is important to recall that Trump has known Dennis Rodman since 2009 and claims the Trump family has admired the Grahams for decades, though he likely met both Grahams only in 2013.Footnote 54 He certainly was aware of their activities in North Korea. While Trump may not have recognized their entrepreneurial diplomacy in his attempts, they certainly did. Franklin Graham vociferously praised Trump’s approach to North Korea as it nearly always gave him a chance to talk about his own work there. Dennis Rodman made sure Trump knew he was present in Singapore during the 2018 summit there in case the president wanted to call on his particular diplomatic skills.Footnote 55

In fairness to Trump, publicity was not the sole motivation for his North Korean diplomacy. Trump has never been shy of expressing a high opinion of himself as a dealmaker and it is quite plausible that he believed his outreach could be successful. This was not an entirely baseless hope. Since Kim Jong-un came to power in 2010, several North Korean experts have believed that Kim was determined to bring economic development to North Korea and might be willing at least to take the first steps towards denuclearization in return for sanctions removal and economic aid that would allow him to build the North Korean economy.Footnote 56 If this analysis was correct, there was a potential path towards an agreement for Trump to follow, but it was fraught with uncertainty regarding Kim’s intentions. Interestingly, as a candidate Trump was well aware of the odds stacked against engagement with North Korea. He told supporters in 2016, “There’s a 10 percent or a 20 percent chance that I can talk him [Kim Jong-un] out of those damn nukes because who the hell wants him to have nukes? And there’s a chance – I’m only gonna make a good deal for us.”Footnote 57 As president, Trump may have learned things about Kim that might have caused him to think his chances of success had improved, but statements to Woodward and those recalled by Bolton indicate that doubts remained for him. Whether Trump continued to believe the odds of success were 10 percent or 20 percent, or even increased to 50 percent, these are odds enticing only to the entrepreneurial diplomat for whom failure is no bar to notoriety.

Conclusion

Donald Trump was hardly the first president unaware of the long and complicated history between the US and the Korean peninsula. He was also not the first president to undervalue the US–ROK alliance and seek to change it. However, he was the first president since the ROK’s democratization in 1988 who failed to recognize how the alliance has evolved in ways that were beneficial to the US and who attempted to change the alliance based on this fundamental misunderstanding. Citizen Trump tweeted in 2013 “What do we get from our economic competitor South Korea for the tremendous cost of protecting them from North Korea? – NOTHING!”Footnote 58 There is no indication that President Trump’s views on the US–ROK alliance ever evolved. The president saw the ROK as a competitor on trade and a free-rider on security, instead of a partner in both. He failed to understand how the American presence in the ROK (and Japan) had guaranteed the stability of Northeast Asia for decades, making possible the creation of one of the most vibrant economic engines for growth the world has ever seen. He also failed to appreciate how vital these relations are to the continued stability of this region, and to American interests there, in the age of a rising China.

Fortunately, the ROK’s response to Trump’s policies was itself a testament to how much the alliance has evolved. Rather than an explosion of anti-Americanism – as some expected – or drastic action in the face of American provocations, the ROK generally acted in ways that de-escalated tensions in the relationship. The Moon Jae-in administration agreed to minor changes in the KORUS FTA and limited quotas on some exports, which allowed President Trump to claim victory without changing much about the trading relationship. On security, there was some talk by Korean politicians of developing a domestic nuclear weapons program, but no substantive action. In cost-sharing negotiations, Moon refused to accede to Trump’s demand for a fivefold increase in the ROK’s contribution to the alliance, but did not overly politicize the issue.Footnote 59 Instead Moon waited for the results of the 2020 election, knowing that a change in administration might resolve the matter and return the alliance to a more cordial footing. South Korean leaders today understand the nuances of relations between democratic states, something the military strongmen who used to rule the ROK had difficulty grasping. The relationship is much stronger because of it.

Regarding North Korea, while it is worth mentioning that Trump’s approach was not as original, or as successful, as the former president would like to claim, it was also not the disaster that many experts feared it might be. Trump can rightly be criticized for doing Kim Jong-un the honor of meeting him personally – three times – while asking little in return. Such meetings were undoubtedly useful for Kim both at home and abroad. However, it appears, at least at this juncture, that these summits and Trump’s larger approach to North Korea did little harm to the US position vis-à-vis the DPRK. No sanctions were lifted, no binding agreements were made, no massive amount of aid was delivered. Much of what Trump “gave,” such as the suspension of military exercises with the ROK, can easily be reversed by the Biden administration if it chooses.Footnote 60

On the positive side, the Trump administration conducted something of a natural experiment with North Korea in testing whether “leader-to-leader” engagement could result in a breakthrough. It now seems, at least for the present, that this is unlikely. It is hard to imagine an American leader being more conciliatory or offering more to Kim Jong-un than Donald Trump. Future American leaders should constantly be vigilant for signs that North Korea is ready to engage in a genuine dialogue over its nuclear weapons, but it appears the current DPRK leadership is not.

Still, the legacy of Trump’s approach will largely be shaped by what comes after it, especially in the next Republican administration. While there is little indication that engagement with North Korea will become a new plank in the next Republican platform, economic nationalism, protectionism, and skepticism about allies have gained a firm hold on the party. Should these sentiments develop into future policies targeting the US–ROK alliance the way Trump did, the danger to the alliance could be very grave indeed. Historians may someday look at the Trump administration as the beginning of the end of the US–ROK alliance and the beginning of an American retreat from Northeast Asia.