Concerns abound about the impact of social media on adolescents as it increasingly becomes an integral part of their social lives. One of the concerns that has received a great deal of attention is the impact of social media on adolescents’ mental health (Gordon, Reference Gordon2020). A large number of studies have been conducted to investigate the impact; however, the findings are mixed, showing both positive and negative impact (Baker & Algorta, Reference Baker and Algorta2016; Best et al., Reference Best, Manktelow and Taylor2014; Seabrook et al., Reference Seabrook, Kern and Rickard2016). What is clear in this growing body of research with seemingly contradictory findings is that the relation between social media use and adolescent mental health is much more complex than originally thought. In line with the recognition of this complexity, more and more researchers examine the mechanism of this relation within the framework of a psychological theory (Keles et al., Reference Keles, McCrae and Grealish2019).

Adolescent Identity Development on Social Media

In a recent theoretical review, Granic et al. (Reference Granic, Morita and Scholten2020) suggested that, in order to understand the impact of digital media on adolescents’ mental health, it is essential to consider their core developmental concern: identity development. For decades, developmental psychologists have studied the challenging transition adolescents are expected to make in order to become functional members of society – that is, moving past identifying with the roles and values of others and toward making social commitments that are in accord with their own interests, aptitudes, and values (Erikson, Reference Erikson1968; Kroger, Reference Kroger2004). Whether or not adolescents successfully make this transition has important implications for their mental health (e.g., Azmitia et al., Reference Azmitia, Syed and Radmacher2013; Kuiper et al., Reference Kuiper, Kirsh and Maiolino2016). Since a considerable proportion of identity development processes is now taking place on social media, it is important to examine how the use of social media affects these processes.

A Model of Adolescent Identity Development

To present a model of adolescent identity development, we build on the theoretical framework proposed by Granic et al. (Reference Granic, Morita and Scholten2020). In this framework, progression toward (a) commitment to person–society integrated values and (b) the construction of a coherent life story constitutes adolescent identity development. The framework specifies key factors at intrapersonal, interpersonal, and cultural levels that shape adolescent identity development. Key factors at the intrapersonal level are psychological needs that drive adolescents to uphold and unite personal and social values and form a coherent life story. Key interpersonal factors are the characteristics of narrative partners that affect how adolescents construct and develop stories about themselves. Finally, key cultural factors are cultural values, norms, and narratives that set the boundaries within which adolescents explore and make commitment choices. This chapter focuses on processes at the interpersonal level, where intrapersonal and cultural factors intersect, as these processes are most pertinent to social media. Specifically, we discuss narrative and dialogical processes as an interpersonal mechanism of identity development (Hammack, Reference Hammack2008; McLean & Pasupathi, Reference McLean and Pasupathi2012). Through sharing self-stories with others, individuals encounter various perspectives, reflect on and learn about themselves, and consolidate or change their commitments, values, and narratives. Furthermore, we clearly differentiate between the subjective and objective aspects of identity by drawing on McAdams’s (Reference McAdams, Westenberg, Blasi and Cohn1998) exposition of the self-as-subject (meaning-making process) and the self-as-object (product of the meaning-making process). We explain how the two aspects of identity develop together through narrative and dialogical processes (see Figure 3.1).

Chapter Overview

We begin by describing the subjective aspect of identity development: changes in commitments and values.1 We explain how conventional commitments change to self-evaluated commitments during adolescence and the key role of introspection in this transition. We then describe the objective aspect of identity development: changes in a self-story, or narrative identity. We explain the process of constructing a coherent life story during adolescence and the function of narrative partners in this process. After the description of each aspect of adolescent identity development, we discuss how the use of social media may facilitate or hinder the key processes involved. Since the field of identity development is just beginning to incorporate social media in its research, our discussion will consist mainly of hypothetical links between social media use and adolescent identity development. However, the paucity of research in this area also means there are many avenues for future research. Therefore, the chapter concludes with future directions for studying the impact of social media use on adolescent identity development.

The Subjective Aspect of Identity Development: Changes in Commitments and Values

Identity is first and foremost the self as subject. Although developmental psychologists have taken different approaches to conceptualizing and studying the subjective self and its changes, there are some commonalities in their descriptions (Kroger, Reference Kroger2004). In this chapter we focus on Erikson’s (Reference Erikson1968) theory of the life cycle and Loevinger’s (Reference Loevinger1976) theory of ego development. Erikson laid out a series of crises that people face in their lifetime and must resolve for proper functioning and development. Although he described all the crises as having some bearing on identity, he characterized the fifth one – which takes place in adolescence – as a major crisis for identity. Erikson conceptualized identity in several different ways. However, later psychologists have focused on his conception of identity as ideological and occupational commitments and expanded it to include interpersonal commitments (e.g., Luyckx et al., Reference Luyckx, Goossens and Soenens2006; Marcia, Reference Marcia1966).

Loevinger (Reference Loevinger1976) also developed a theory of changes in the subjective self, namely ego development theory. Unlike Erikson’s theory, Loevinger’s theory is not built around chronological age, and therefore the ego stages are not tied to age-related challenges and tasks. The theory describes changes in various aspects of the self, such as impulse control, conscious preoccupations, and cognitive and interpersonal styles. At its core, ego development theory is about changes in an individual’s frame of reference, the values in accordance with which an individual makes experience meaningful and coherent (Hy & Loevinger, Reference Hy and Loevinger1996). In short, changes in commitments and values constitute the subjective aspect of identity development.

The Formation of Self-Evaluated Commitments in Adolescence

Identity development is a lifelong process. Throughout life, identity undergoes qualitative changes (Kroger, Reference Kroger2004). However, particular attention has been paid to the type of identity that is thought to mark the entrance to adulthood. According to Erikson’s (Reference Erikson1968) theory of the life cycle, childhood is a period in which individuals learn the roles of adults around them and focus on becoming skillful at preparatory tasks provided by their family, school, and community. Children are therefore identified with the roles and values of others in the immediate environment. In adolescence, psychological needs and social demands drive individuals to explore different occupations and ideologies in the larger society and commit to occupations and ideologies that match their own interests, aptitudes, and values to find their niche in society. This serves as the foundation for adulthood.

It is now widely recognized that identity exploration and commitment are iterative processes (Bosma & Kunnen, Reference Bosma and Kunnen2001; Grotevant, Reference Grotevant1987; Kerpelman et al., Reference Kerpelman, Pittman and Lamke1997; Luyckx et al., Reference Luyckx, Goossens and Soenens2006). For example, Luyckx et al. (Reference Luyckx, Goossens and Soenens2006, Reference Luyckx, Klimstra, Duriez, Van Petegem and Beyers2013) suggested that identity formation involves two cycles. The first one consists of exploration in breadth and commitment-making. In this cycle, individuals explore various values and goals and make initial commitments. The second cycle consists of exploration in depth and identification with commitment. Specifically, current commitments are continually re-evaluated through self-reflection and interpersonal dialogue, and if individuals feel confident about their commitments, they identify with them.

A similar developmental sequence can be found in Loevinger’s (Reference Loevinger1976) ego development theory: progression from the Conformist stage to the Conscientious stage via the Self-Aware stage. At the Conformist stage, social belonging is of paramount importance, and most effort is put into gaining acceptance by a social group. Individuals at this stage conform to the norms and values of their social groups, which are based on external characteristics (e.g., physical appearance, outward behavior). Thus, they seek social acceptance and recognition by trying to look or behave in a socially desirable manner. At the next, Self-Aware stage, individuals begin to explore inner aspects of themselves, and conformity starts to become less rigid. When the next, Conscientious stage is reached, individuals have gained a rich understanding of their motives and personality traits. Individuals at this stage therefore evaluate and commit to social values based on their internal characteristics (i.e., the formation of self-evaluated commitments; Loevinger, Reference Loevinger1987). Although ego development was conceptualized independently of chronological age, research has shown that the progression from the Conformist stage toward the Conscientious stage commonly takes place during adolescence (Syed & Seiffge-Krende, Reference Syed and Seiffge-Krenke2015; Westenberg & Gjerde, Reference Westenberg and Gjerde1999).

In sum, the transition from conventional commitments to self-evaluated commitments constitutes the subjective aspect of adolescent identity development. This transition is marked by changes in the mode of commitment – from conformity to self-evaluated commitment – and the nature of commitments – from external to internal characteristics.

Identity Exploration and Introspection

Exploration to gain an understanding of one’s environment and oneself is considered a key mechanism of identity development (Grotevant, Reference Grotevant1987). Erikson (Reference Erikson1968) emphasized the importance of psychosocial moratorium, the period during which adolescents explore different ideologies and occupations in society and find suitable ones. Such exploration entails introspection to find out one’s own interests, values, and aptitudes. In Loevinger’s (Reference Loevinger1976) ego development, we have seen that progression from the Conformist stage to the Conscientious stage goes through the Self-Aware stage, where individuals begin introspection to gain a deeper understanding of their internal characteristics. In order to move on from rigid conformity, individuals must shift their focus from external to internal aspects of themselves to understand their own interests and values, which they can then use to evaluate and choose social values to commit to. Indeed, introspection was found to be the most common factor in identity development (Kroger & Green, Reference Kroger and Green1996).

The capacity for introspection begins to develop in adolescence (Sebastian et al., Reference Sebastian, Burnett and Blakemore2008), making it a sensitive period for cultivating the capacity. Counseling, psychotherapy, and educational programs have been used to aid adolescents’ identity exploration (Kroger, Reference Kroger2004). Marcia (Reference Marcia1989) suggested that it is important to create an open and safe environment that encourages free exploration and serves as a safety net if adolescents’ choices go awry. Indeed, it has long been noted that open and accepting relationships are crucial in facilitating self-exploration (Rogers, Reference Rogers1961). As we discuss later in the chapter, identity exploration and introspection often happen during or following interpersonal dialogue, and the characteristics of conversational partners greatly affect the extent to which individuals engage in self-exploration and gain insights into themselves.

Social Media and the Adolescent Development of Commitments and Values

We have explained the adolescent development of commitments and values: the transition from conventional to self-evaluated commitments. We now discuss how the use of social media may affect this transition. To reiterate, identity exploration and introspection inherent in the exploration are a key mechanism through which adolescents move on from conformity and preoccupation with external characteristics and form self-evaluated commitments. Therefore, the use of social media would facilitate the transition if it supports identity exploration and introspection. Conversely, the use of social media would hinder the transition if it prevents identity exploration and introspection, increases conformity, and makes adolescents fixated on appearance.

A Playground for Identity Exploration

Social media provides the opportunity for people to try out different versions of themselves and see what feels right (Casserly, Reference Casserly2011). When asked about who they are on social media, people often report that they have different personas depending on the platform (Zhong et al., Reference Zhong, Chang, Karamshuk, Lee and Sastry2017). This may be because different platforms tend to attract different audiences by virtue of their design and functionality. For example, Instagram may be well suited to expressing people’s artistic side and therefore popular among artists, while Reddit may cater to their contemplative, intellectual side and attract curious minds and experts. The beauty of social media is therefore that all platforms taken together serve as a playground in which individuals can explore different aspects of themselves. However, there is also the downside of a plethora of options: Too many options can create paralysis and lead to ruminative exploration, keeping adolescents from completing the cycle of identity formation (Beyers & Luyckx, Reference Beyers and Luyckx2016). As we have discussed, successful adolescent identity development requires not only exploration of commitment options but also introspection to evaluate whether these options fit one’s personality. Therefore, social media platforms that provide space for identity exploration as well as self-reflection may be more conducive to identity development than those that provide space for the former only.

Potent Social Norms and Values

While social media offers plenty of opportunities for identity exploration, the large scale of social media also enables potent social norms and values, potentially making it more difficult for adolescents to move on from conformity. Most adolescents in the pre–social media era are likely to have negotiated with trends and conventions that manifested themselves in a relatively small social group, at most on a national scale. With social media, however, adolescents now have the possibility to observe trends on a much larger global scale, likely experiencing greater pressure to conform to these trends. Indeed, norms and values on social media may have stronger influence than those offline because they are more widely shared and more readily accessed (Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018).

Social attitudes that currently prevail in Western cultures and may be magnified by social media are anti-mainstream sentiments (Vinh, Reference Vinh2021). Those who follow counterculture movements are usually called hippies or hipsters, going against what – in their eyes – everyone else is doing. One reflection of this trend is the popularity of prank videos on social media, in which people violate social conventions and norms for entertainment. The anti-mainstream sentiments have appealed to so many people that they themselves have become the norm and the source of conformity. Thus, social media can spread and magnify trends rapidly to create potent social norms and values, including those that espouse anti-mainstream sentiments.

Inescapable Past Selves

An essential condition for identity development is the freedom to leave behind old identities and explore new ones. Unfortunately, such freedom is not always guaranteed on the Internet. What people say and do on the Internet is permanently recorded and often remains on the Internet for future generations to unearth (Eichhorn, Reference Eichhorn2019; Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Telzer and Prinstein2020). This permanence of information on the Internet, especially on social media, can be problematic for identity development (see Davis & Weinstein, Reference Davis, Weinstein and Wright2017). Traces of old identities on social media can mislead others into thinking that the old identities still hold true and make it difficult for individuals to change or to fully embrace the change. There is the increasing occurrence of people being criticized or getting fired for what they said or did on the Internet in the past even though these views or deeds no longer reflect them (e.g., Arora, Reference Arora2021). Accordingly, there are signs of adolescents and young adults erasing their social media posts for fear of repercussions (Davis & Weinstein, Reference Davis, Weinstein and Wright2017; Jargon, Reference Jargon2020; Smith, Reference Smith2013). These privacy issues therefore seem to be making it difficult for individuals to free themselves from the past and move forward.

However, reminders of one’s past selves may also benefit identity development. In adolescent years, individuals may go through many different phases. For example, an adolescent may experience the “goth” phase from age 15 to 16 years, reflected in a series of photos of a black-clothed self with plaid skirts and chains. From age 17 to 18 years, this adolescent may be absorbed in environmentalism, reflected in posts and photos depicting community efforts and environmental protests. Transition between such phases may sometimes feel fluent and smooth and may be easily forgotten. Snippets of social media content and interactions in the past can help individuals recall parts of their past selves that they may otherwise have forgotten. Being reminded of past selves can also help individuals reflect on the development they have gone through and understand that identity is never permanent and continues to change over time (Pasupathi et al., Reference Pasupathi, Mansour and Brubaker2007). It is nonetheless important that the right to social media data belong to users so that they can access their past data when they want to and they can erase them if they deem them harmful to their current identity.

A Tool for Distraction or Introspection?

One of the concerns that social media has generated is that it may act as a distraction from oneself (The School of Life, n.d.). Social media is filled with information about people’s lives and world events, and passive usage of social media (e.g., reading news feeds) is more common than active usage (e.g., posting status updates; Verduyn et al., Reference Verduyn, Lee and Park2015). The implication is that people are focused mainly on other people’s lives on social media, leaving little room to reflect on their own lives and gain insights into themselves. Furthermore, information overload on social media, which has been shown to lead to “social media fatigue” in some (Bright et al., Reference Bright, Kleiser and Grau2015; Dhir et al., Reference Dhir, Kaur, Chen and Pallesen2019), may deplete cognitive resources necessary for digesting information and integrating it into a sense of self. Indeed, Misra and Stokols (Reference Misra and Stokols2012) found that individuals who experienced an overload of digital information spent less time on contemplative activities such as self-reflection.

Nevertheless, social media has some functionalities that could help people gain insights into themselves. For example, Facebook’s “Year in Review” posts provide users with a chance to reflect on their life experiences in the past year. Such reflection may bring people insights into what kind of things they value and are interested in and what they are good at. Furthermore, as we discuss later, social media significantly increases the chance to receive feedback about oneself from others (e.g., boyd & Heer, Reference boyd and Heer2006), thereby deepening self-understanding.

Emphasis on Appearance

Another important issue to consider is the extent to which social media promotes preoccupation with appearance. Although social media can be used for a variety of purposes, posting pictures of one’s physical appearance (i.e., selfies) is popular among adolescents, and many adolescents are preoccupied with how others perceive their physical appearance on social media (Boursier & Manna, Reference Boursier and Manna2018; Choukas-Bradley et al., Reference Choukas-Bradley, Nesi, Widman and Galla2020). The increasing use of clickbaits to attract followers on social media may also be contributing to their perceived importance of appearance and superficial impressions. Preoccupation with appearance on social media is associated with a number of negative mental health indices among adolescents (Choukas-Bradley et al., Reference Choukas-Bradley, Nesi, Widman and Galla2020). While having a healthy body image is important, adolescent identity development entails a shift in the source of self-esteem from external to internal attributes. Therefore, social media is likely to be harmful to adolescents to the extent that it makes them fixated on appearance.

The design and affordances of social media platforms may affect the degree to which adolescents focus on external aspects of themselves. For example, photo-based social media platforms such as Instagram may attract those who are concerned with physical appearance, and consequently social values and norms that revolve around physical appearance may be more prevalent on these platforms. Therefore, the use of photo-based platforms may put adolescents at higher risk of being influenced by appearance-based values and norms. Furthermore, given that individuals can explore and express their internal characteristics more easily using concepts and words rather than images, text-based platforms such as Reddit and Tumblr might be more conducive to introspection and the expression of inner qualities. It is nonetheless important to note that the nonverbal expression of internal characteristics is possible (e.g., an expression of creativity in dancing), and photo-based platforms can also serve as a place for more mature expressions of identity.

The Objective Aspect of Identity Development: Changes in a Narrative Identity

Thus far, we have discussed the subjective aspect of identity development: changes in commitments and values. We now turn to the objective aspect, manifestations of the changes. Commitments and values manifest themselves in several ways. For example, people strive to fulfill their commitments and values; therefore, commitments and values are manifested in goal-striving (Maslow, Reference Maslow1970; Schwartz, Reference Schwartz, Seligman, Olson and Zanna1996). Moreover, values act as a frame of reference in perception to create “coherent meanings in experience” (Hy & Loevinger, Reference Hy and Loevinger1996, p. 4). Thus, they are reflected in the meanings that individuals assign to objects and events. When this meaning-making process is applied to past experiences, it often takes the form of storytelling. A story about the self that an individual creates based on their past experiences has been termed “narrative identity” (McAdams, Reference McAdams2018; Singer, Reference Singer2004). In storytelling, individuals make sense of and organize their past experiences by relating them to important aspects of themselves (Pasupathi et al., Reference Pasupathi, Mansour and Brubaker2007). In other words, past experiences that are relevant to one’s goals and values (i.e., self-defining memories) make up the main contents of a narrative identity (Blagov & Singer, Reference Blagov and Singer2004; Singer et al., Reference Singer, Blagov, Berry and Oost2013). In short, commitments and values (identity-as-subject) act as the guiding principles of storytelling to make sense of and organize past experiences into a narrative identity (identity-as-object; see Figure 3.1).

The Construction of a Coherent Life Story in Adolescence

As adolescents’ commitments change from conventional to self-evaluated commitments, corresponding changes likely occur in their narrative identities. During adolescence, a narrative identity changes from relatively disjointed descriptions of roles and habits to an autobiographical narrative, which demonstrates more complex reflective thinking and a causal understanding of one’s life experiences (Habermas & de Silveira, Reference Habermas and de Silveira2008; McAdams, Reference McAdams, Westenberg, Blasi and Cohn1998). Specifically, adolescents’ narrative identities increasingly take the form of a life story, which tells how the past self has grown into the present self, which may then become an envisioned future self (McAdams, Reference McAdams2018; McAdams & McLean, Reference McAdams and McLean2013). Their past, present, and future become clearly differentiated and yet causally connected to form a temporally coherent life story (Habermas & Bluck, Reference Habermas and Bluck2000; Pasupathi et al., Reference Pasupathi, Mansour and Brubaker2007). In addition to temporal coherence, there is another type of coherence that likely emerges in adolescents’ narrative identities: person–society coherence (Syed & McLean, Reference Syed and McLean2016). This type of coherence shows alignment between individuals’ personal attributes and their social contexts. As discussed earlier, adolescent identity development is progression toward commitment to social values that match personal interests, values, and talents. Therefore, narrative identities likely exhibit temporal and person–society coherence toward the end of adolescent development, weaving together the past self that was identified with the roles and values of others, the present self that commits to person–society integrated values, and the future self that will fulfill these values.

Besides these structural changes, adolescent identity development is likely to be accompanied by related changes in the theme of a narrative identity. Granic et al. (Reference Granic, Morita and Scholten2020) suggested that the dynamics of the needs for agency and communion shift during adolescence and that this shift may be reflected in the relative prominence on agency versus communion themes in a narrative identity. Specifically, as adolescents start to engage in self-exploration and gain better insight into their own interests and values, a predominance of communion themes may give way to a predominance of agency themes (see Van Doeselaar et al., Reference Van Doeselaar, McLean, Meeus, Denissen and Klimstra2020, for some indirect support for this). Toward the end of adolescent identity development, when the needs for agency and communion become more balanced, agency and communion themes may become relatively equalized and united in a narrative identity.

Another theme that is relevant to adolescent identity development is external versus internal focus. As discussed earlier, the nature of commitments changes from external to internal characteristics during adolescence. Therefore, the theme of adolescents’ narrative identities is likely to change from that of trying to look good and behave properly to that of cultivating their inner traits.

Dialogue and the Function of Narrative Partners

Storytelling is inherently a social activity and therefore usually involves dialogue (Hammack, Reference Hammack2008; Hermans, Reference Hermans2004). A narrative identity expressed in storytelling can be affirmed or challenged, which may in turn consolidate, weaken, or change commitments and values (McLean & Pasupathi, Reference McLean and Pasupathi2012; Thorne, Reference Thorne2000; see Figure 3.1). Thus, storytelling and dialogue are an important mechanism of identity development. Whether storytelling and dialogue contribute meaningfully to identity development depends heavily on the characteristics of their narrative partners (McLean et al., Reference McLean, Pasupathi and Pals2007; Pasupathi & Hoyt, Reference Pasupathi and Hoyt2009). There are three essential functions that narrative partners serve: (a) elaboration, (b) grappling, and (c) attention and validation (Granic et al., Reference Granic, Morita and Scholten2020).

First, narrative partners help people elaborate on their stories (Fivush et al., Reference Fivush, Haden and Reese2006; Pasupathi et al., Reference Pasupathi, Mansour and Brubaker2007). To construct a meaningful and coherent life story from past experiences, you must derive meaning from these experiences, and a simple recounting of past experiences is often insufficient (Blagov & Singer, Reference Blagov and Singer2004; Singer et al., Reference Singer, Blagov, Berry and Oost2013). Therefore, narrative partners’ requests for elaboration are essential. Blagov and Singer (Reference Blagov and Singer2004) specified four dimensions of self-defining memories, which have implications for elaboration requests. Specifically, elaboration requests are likely to be especially helpful if they use a time frame most conducive to meaning-making in a given situation (e.g., “Tell me exactly what happened in that moment”; “How did you change during your college years?”) and ask about affect, or more specifically, emotional valence and intensity (e.g., “How did the experience make you feel?”; “How much impact did the experience have on you?”), content, or the relevance to values and goals (e.g., “Why is the experience important to you?”; “How does the experience help you achieve your goals?”), and meaning, or learning and growth (e.g., “What did you learn from the experience?”; “How did the experience change you as a person?”).

The second important function of narrative partners is “grappling”, which is an act of supporting identity exploration in a dialogue while maintaining an attitude of open-mindedness and patience (Granic et al., Reference Granic, Morita and Scholten2020). Engaging in dialogue with others is essentially identity exploration because different people uphold different values and you are encouraged to take others’ perspectives in dialogue (Hermans, Reference Hermans2004). Your values and narratives may sometimes be challenged in the process, and listening to alternative views may bring new insights and weaken or change your values and commitments. However, such a challenge is likely most fruitful when it is done in an open and accepting relationship (Rogers, Reference Rogers1961). Moreover, it is important that narrative partners remain patient despite unexpected perspective changes and contradictions, which are due to occur during identity exploration (Granic et al., Reference Granic, Morita and Scholten2020).

Finally, narrative partners provide attention and affirmation. When narrative partners listen attentively and affirm your life story, your values and goal endeavors are reflected back to you and become consolidated (McLean & Pasupathi, Reference McLean and Pasupathi2012; Pasupathi & Rich, Reference Pasupathi and Rich2005). Those who show interest and give you affirmation are usually the ones who share your values and commitments. As discussed earlier, adolescent identity development is considered complete when they find their niche in society, where like-minded others share the interests and values that adolescents have discovered through self-exploration (Erikson, Reference Erikson1968). Therefore, finding narrative partners who share personal values and aspirations is important especially toward the end of adolescent identity development.

Social Media and the Adolescent Development of a Narrative Identity

We have discussed how commitments and a narrative identity develop together through storytelling and dialogue in adolescence. In this section we explore different ways in which social media can support or obstruct storytelling and dialogue, thereby facilitating or hindering the adolescent development of a narrative identity.

Dialogue with Diverse Groups of People

Social media emerged with the advent of the Web 2.0, a dramatic change of the Internet from a place for passive consumption to active participation, interaction, and collaboration (Peters, Reference Peters2020). Anyone who has access to the Internet can express and share their views and stories on social media, and there are usually others – sometimes hundreds and thousands of people – who validate or reject their views and stories. Storytelling and dialogue in such a large, interconnected social environment have never existed before. Social media has made it easy to have dialogue with people who come from different cultures and backgrounds, thus significantly increasing the chance of encountering different perspectives. Since taking different perspectives during social interaction is essential for identity development (Hermans, Reference Hermans2004; Kroger, Reference Kroger2004), social media can be a great tool for adolescents’ identity development. While there is some concern about the increasing frequency of conflicts resulting from the increased contact with diverse groups of people, conflicts can be meaningful experiences and contribute to identity development, especially if they are managed with understanding (Rogers, Reference Rogers1961). Therefore, the presence of moderators who are discerning but also empathetic would be valuable.

Censorship

There has been growing concern and controversy surrounding censorship on social media (Heins, Reference Heins2014). Social media platforms such as Twitter and YouTube recently came under fire after deleting posts or banning users and channels that express certain ideological views (e.g., BBC News, 2020; Zaru, Reference Zaru2021). Social media companies have long suggested that their platforms provide a space for the free exchange of views and ideas. However, it has become apparent that these platforms are not neutral public platforms, but rather, just like traditional media, they promote certain content and suppress others according to their interests and ideologies (Lewis, Reference Lewis2021). Although social media companies began to acknowledge such editorial actions, it remains largely unclear how they are curating content. As we have just discussed, dialogue with diverse groups of people plays an essential role in identity development. Therefore, if social media platforms exercise editorial power, it is important that they make their decisions transparent so that people can make informed decisions about which platforms to use for a meaningful dialogue.

Narrative Elaboration on Social Media

Social media platforms generally support the elaboration of narratives as they provide comment sections and encourage dialogue between users. However, the unique affordances of social media platforms may affect the extent to which users elaborate on their stories. For example, Twitter sets a strict character limit for posts and comments and may therefore hinder the elaboration of narratives and deep dialogue compared to platforms like Facebook, Reddit, and Tumblr. Indeed, in an in-depth interview with activists, Comunello et al. (Reference Comunello, Mulargia and Parisi2016) found that the activists perceived platform affordances as having a significant impact on their ability to express themselves, with one of them reporting that the possibility to write longer texts allowed him to better articulate his opinions. Misunderstandings between users may be more common on platforms that restrict the length of posts and comments because short posts and comments do not easily allow clarification of meaning. Such platforms might predispose users to insult each other instead of asking each other questions to elaborate on their self-stories.

Attention and Validation on Social Media

Social media offers unprecedented opportunities to be listened to and validated by others. Before social media, individuals whose values and beliefs deviated from the norm had difficulty finding someone who would listen to or affirm their views (e.g., Gray, Reference Gray2009). It is now much easier to find like-minded others because social media platforms such as Facebook and Reddit enable people to search for various communities. This is, for example, reflected in online activism by various groups of people (Bennett, Reference Bennett2014; Buell Hirsch, Reference Buell Hirsch2014; Sandoval-Almazan & Gil-Gracia, Reference Sandoval-Almazan and Gil-Garcia2014). However, the downside of such diverse and specific communities is that they can create echo chambers and shun interaction outside the communities (Singer, Reference Singer2020). An optimal social media environment may therefore be that which makes it easy to find like-minded people while encouraging communication and interaction between diverse groups.

Attention and validation are most effective if they come from close people (Carr et al., Reference Carr, Wohn and Hayes2016). Hayes et al. (Reference Hayes, Carr and Wohn2016) found that people experienced more personal support on platforms that allowed them to easily narrow their audience and share posts with close friends (e.g., Snapchat). Therefore, adolescents who are in the phase of identity consolidation may benefit more by using platforms that make it easy to target posts to close friends.

Future Research Directions

Now that we have presented a theoretical model of adolescent identity development and discussed how the use of social media may facilitate or hinder the development, we suggest a few directions for future research. First, it is important to study how narrative identities typically develop during adolescence. Since many adolescents currently use social media for identity expressions (i.e., narrative identities), it is possible to examine the adolescent development of a narrative identity on social media (Granic et al., Reference Granic, Morita and Scholten2020). Although social media platforms have tightened restrictions on data access over the past few years (e.g., Facebook Business, 2018; Hemsley, Reference Hemsley2019), private data download options and application programming interfaces remain a viable avenue for collecting social media data for research (Lomborg & Bechmann, Reference Lomborg and Bechmann2014; Taylor & Pagliari, Reference Taylor and Pagliari2018). Adolescents’ social media posts can be analyzed with research methods that have been developed to study narrative identities (Adler et al., Reference Adler, Dunlop and Fivush2017). The narrative research framework specifies how to code narrative identities in terms of structure (e.g., coherence) and theme (e.g., agency, communion). New coding manuals need to be developed for themes that are relevant to adolescent identity development but not included in the framework (e.g., external versus internal focus). It is important to note, however, that people are not given narrative prompts to elicit detailed information on social media. Therefore, it may be necessary to use an additional method such as an interview to fully understand what is being expressed in social media posts. Alternatively, researchers may develop an application to add narrative prompts to social media posts. Once the methods are developed, researchers can conduct longitudinal studies to examine how the structure and theme of narrative identities change during adolescence.

Another important direction for future research is to study how the design and affordances of social media platforms affect key processes of identity development (introspection, elaboration, grappling, attention, and validation). For this line of research, it is important to first examine the unique affordances and features of different social media platforms. For example, researchers may assess the diversity of communities on social media platforms (see, e.g., Bisgin et al., Reference Bisgin, Agarwal and Xu2012; De Salve et al., Reference De Salve, Guidi, Ricci and Mori2018, for the methods). To assess the processes of identity development, researchers can code adolescents’ posts as well as others’ comments and reactions by using or adapting existing methods for studying these processes (e.g., Pasupathi & Hoyt, Reference Pasupathi and Hoyt2009; Pasupathi & Rich, Reference Pasupathi and Rich2005) or developing new ones.

However, like the analysis of narrative identities, the study of identity development processes may require more than social media data (especially introspection, which does not easily manifest itself). It would therefore be best to combine the coding of social media content with other methods that probe individuals’ experiences on social media (e.g., interviews). One useful approach is the stimulated recall method, in which interviews are conducted around objective data to aid the recollection of experiences associated with the data (Bloom, Reference Bloom1953). Using social media data as memory cues can facilitate the recollection of thoughts and feelings that occurred during the use of social media (Griffioen et al., Reference Griffioen, Van Rooij, Lichtwarck-Aschoff and Granic2020).

Finally, a worthwhile research direction is to develop applications that support key identity development processes and examine whether they facilitate adolescents’ identity development. For example, researchers may design an application based on the four dimensions of self-defining memories (Blagov & Singer, Reference Blagov and Singer2004) to help the meaning-making and organization of past experiences:

Affect: Users can rate the emotional valence and intensity of social media posts so that they can gain insights into what kind of events have an impact on them and the nature and degree of the impact.

Content: Users can assign value and commitment tags to their social media posts so that they can make explicit connections between their values and commitments and their life experiences.

Meaning: Social media posts are accompanied by narrative prompts so as to help users derive meaning from their experiences and construct a meaningful and coherent narrative identity.2

Time specificity: Users’ social media posts can be displayed in different time frames (e.g., a given moment in time, day, week, month, year, and life stage) so that users can create narratives in these different time frames and later integrate these narratives into a life story.

After applications are developed, researchers can conduct studies (e.g., randomized control trials) to evaluate their efficacy in facilitating adolescent identity development. It is recommended that researchers take person-specific effects into account when evaluating the effects of social media (e.g., see Valkenburg et al., Reference Valkenburg, Beyens, Pouwels, van Driel and Keijsers2021).

Conclusion

In this chapter we have suggested that it is important to study how the use of social media affects adolescent identity development in order to understand the mechanism of the impact of social media on adolescent mental health. We presented a model of the dual aspect of adolescent identity development – progression toward the formation of self-evaluated commitments and values and the construction of a coherent life story – and discussed how the use of social media may facilitate or hinder the key processes involved, namely introspection, storytelling, and dialogue. It was suggested that future research should devise methods for studying narratives on social media and discover how narrative identities develop during adolescence. We also suggested examining the design and affordances of social media platforms and how they affect the key processes of identity development. We hope that this chapter will provide a useful framework for future research on the impact of social media on adolescents and encourage media developers to design social media environments that support identity development.

Peer relationships have always served an important role in adolescent development. The quality of peer relationships is a driving force in adolescents’ academic functioning (Wentzel et al., Reference Wentzel, Jablansky and Scalise2021), sense of self (Bellmore & Cillessen, Reference Bellmore and Cillessen2006), and mental health (La Greca & Harrison, Reference La Greca and Harrison2005). Furthermore, many – if not most – of the core developmental tasks that adolescents must traverse require navigating the peer context. Adolescents obviously cannot establish intimate peer relationships or explore romantic feelings and sexuality without engaging with their peers. Even experimenting with different versions of the self often requires feedback from peers to help understand how the external world will receive a potential internal self (Erikson, Reference Erikson1968).

Digital communication and social media have likely reshaped adolescents’ peer relationships and social environment more than any other force in the 21st century. Digital communication is adolescents’ preferred method for engaging with peers (Anderson & Jiang, Reference Anderson and Jiang2018), beyond even face-to-face interaction (Lenhart et al., Reference Lenhart, Ling, Campbell and Purcell2010). Nearly 90% of adolescents report using social media platforms every single day (Lenhart, Reference Lenhart2015), primarily to interact with the same peers and friends they interact in their offline lives. It is not surprising then that adolescents’ digital peer interactions are related to a range of outcomes similar to in-person peer interactions: self-concept and self-esteem (Steinsbekk et al., Reference Steinsbekk, Wichstrøm, Stenseng, Nesi, Hygen and Skalická2021), involvement in risk behavior (Ehrenreich et al., Reference Ehrenreich, Underwood and Ackerman2014), and mental health (Vannucci & McCauley Ohannessian, Reference Vannucci and McCauley Ohannessian2019). Digital communication is a critically important context that has transformed the way that the peer process unfolds and impacts adolescents (Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018a, Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018b).

This chapter will begin with an examination of the features of social media that make it such a powerful context in which peer interaction occurs, briefly reviewing the theoretical underpinnings of this context. We will review recent research on how three important peer constructs unfold and are shaped by digital media: peer influence, social connectedness (vs. isolation), and popularity and social status. We will then discuss challenges and opportunities for studying peer relationships in the context of digital media. Finally, we will conclude with a discussion of the future directions in this field.

Theoretical Considerations

Much of the early research examining how digital communication relates to peer relationships was guided by existing, “offline” developmental theory. This perspective coalesced in co-construction theory (Subrahmanyam et al., Reference Subrahmanyam, Smahel and Greenfield2006), which suggested that adolescents use social interaction in digital spaces as a means to explore the same developmental issues occurring in their offline lives. Accordingly, adolescents are active participants in the construction of the online content that they consume and create, building environments that can facilitate their developmental needs. Subrahmanyam and colleagues viewed these on- and offline environments as being “psychologically continuous” (Subrahmanyam et al., Reference Subrahmanyam, Reich, Waechter and Espinoza2008, p. 421). In line with this perspective, many early studies of peer relations in the digital sphere sought to examine whether important peer processes truly did translate between realms. For example, do adolescents’ offline social deficits translate into online spaces (i.e., the rich-get-richer hypothesis) or are online contexts used as a more comfortable space to compensate for their offline deficits (social compensation; Kraut et al., Reference Kraut, Patterson, Lundmark, Kiesler, Mukophadhyay and Scherlis1998, Reference Kraut, Kiesler, Boneva, Cummings, Helgeson and Crawford2002; Valkenburg & Peter, Reference Valkenburg and Peter2007)? Alternatively, considerable research examined the extent to which individuals who engaged in offline bullying behaviors or were subjected to offline victimization were also involved in these aggressive relations online (Kowalski et al., Reference Kowalski, Giumetti, Schroeder and Lattaner2014), and whether there was similar overlap in offline and online prosocial behavior (Wright & Li, Reference Wright and Li2011).

Co-construction was an important advancement, in that it promoted the application of existing developmental theory to the study of adolescents’ online interactions, which had previously functioned with a fractured combination of theories emerging from a variety of disciplines (see Underwood et al., Reference Underwood, Brown, Ehrenreich, Rubin, Bukowski and Laursen2018). However, co-construction theory placed great emphasis on the overlap between adolescents’ on- and offline worlds, highlighting that adolescents are creating these spaces in an effort to fulfill their offline developmental needs (Subrahmanyam et al., Reference Subrahmanyam, Reich, Waechter and Espinoza2008). Although co-construction does not suggest that these spaces are the same (despite being psychologically connected), little focus was placed on systematically identifying the ways in which digital communication functionally changes adolescents’ peer interactions. To bridge this gap, the transformational framework (Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018a, Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018b), sought to systematically identify specific ways that social media transforms peer experiences, proposing five specific methods. First, social media increases the frequency and immediacy of peer interactions, allowing (and encouraging) near-constant contact with peers. Second, and relating to this, social media also amplifies the demands of peer interactions, creating new expectations to be available and responsive to peers. Third, social media changes the qualitative nature and feel of peer interactions, for example by changing the access to various social cues, and placing a greater emphasis on quantitative peer metrics such as number of likes and followers. Fourth, social media affords youth new opportunities for compensating behaviors, such as the opportunity to maintain relationships despite physical distance. Finally, social media also provides adolescents with the potential to engage in entirely new social behaviors, such as virtually stalking romantic partners, or passively viewing the entire peer network.

Although this recently proposed framework has received limited empirical examination to date, initial findings examining the role of social media on women’s body image have generally supported the model (Choukas-Bradley et al., Reference Choukas-Bradley, Nesi, Widman and Higgins2019). Additional research is needed, but the transformation framework builds on existing developmental theory to highlight specific – and testable – ways that peer interactions should differ in, and be affected by, these digital contexts. Perhaps most importantly for its continued utility, the transformational framework highlights seven specific aspects of the social media environment (asynchronicity, permanence, publicness, availability, cue absence, quantifiability, and visualness) that transcend specific digital media platforms and tools (e.g., Facebook vs. Snapchat vs. text messaging). Given the incredible pace in which digital platforms rise and fall in popularity, emphasizing broader features of these platforms is critically important for a cohesive study of peer interactions in digital spaces over time.

Transformed Peer Constructs in Digital Communication

Guided by co-construction and the transformational framework, researchers have established the importance of digital communication in both promoting and inhibiting a variety of peer processes, and at times fundamentally transforming these processes altogether. In the following sections, we will review recent research on the role of social media on three of these important peer processes and constructs: peer influence, social connectedness versus isolation, and popularity/status. These sections will not serve as a comprehensive review but will instead highlight recent trends and future directions.

Peer Influence in Digital Realms

Susceptibility to peer influence peaks during the adolescent years (Steinberg & Monahan, Reference Steinberg and Monahan2007), due to an increased importance of peer relationships and status during this period (Prinstein & Dodge, Reference Prinstein and Dodge2008), as well as neurological development (Sommerville, Reference Somerville2013; Steinberg, Reference Steinberg2008). Adolescents look to their peers as informative models for what behaviors are considered acceptable and desirable (injunctive norms), and to assess the how frequent various behaviors are (descriptive norms; Kallgren et al., Reference Kallgren, Reno and Cialdini2000). Due to the highly public nature of many social media platforms, adolescents are able to spend hours examining the posted lives of their close friends and more distant peers. Because adolescents’ social media feeds display the content produced by their wide social networks, this could also serve to blur the line between proximal norms (their immediate friends) and more distal or global norms (peers in general). A great deal of research on peer influence has focused on how it can affect the development of problematic behaviors such as substance use (Geusens & Beullens, Reference Geusens and Beullens2017a, Reference Geusens and Beullens2017b). Adolescents who believe that their friends and peers are using substances (or hold positive views of substance use) are more likely to engage in this behavior themselves. Depictions of substance use are viewed on social media by both adolescents (Boyle et al., Reference Boyle, Earle, LaBrie and Ballou2017; Carrotte et al., Reference Carrotte, Dietze, Wright and Lim2016) and college-aged adults (Moewaka Barnes et al., Reference Moewaka Barnes, McCreanor, Goodwin, Lyons, Griffin and Hutton2016; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Snelson and Elison-Bowers2010), and these depictions in turn relate to individuals’ perception of injunctive norms (Boyle et al., Reference Boyle, LaBrie, Froidevaux and Witkovic2016; Yoo et al., Reference Yoo, Yang and Cho2016) and their own substance use (Geusens & Beullens, Reference Geusens and Beullens2017b). Substance use presentations on social media likely influence adolescents by changing their perception of the acceptability and prevalence of these behaviors. In one study, viewing peers’ posts about substance use improved the perceived desirability and positive expectancies of substance use behaviors (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Unger and Soto2014). Another study found that viewing friends’ substance use posts on social media predicted elevated drinking one year later, and this relationship was mediated by more positive injunctive peer norms about alcohol (Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Rothenberg, Hussong and Jackson2017).

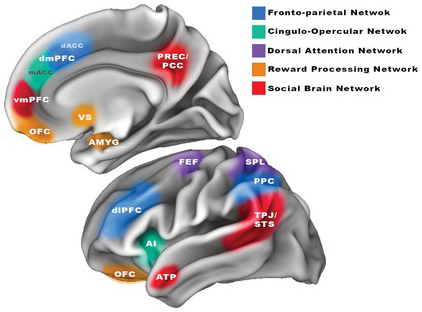

However, social media does not only influence adolescents by allowing them to observe their peers, but also permits adolescents to be observed by their peers as well. Adolescents are heavily influenced by the notion (accurate or inaccurate) that their activities are being viewed and judged by peers. Although the impact of the imaginary audience has been discussed for decades (Elkind, Reference Elkind1967), recent fMRI studies support the neurological underpinnings for this influence process. Simply being in the presence of peers increases adolescents’ susceptibility to peer influence by increasing functioning in the regions of the brain responsible for social cognition and reward seeking (primarily the amygdala, striatum, and prefrontal cortex; Somerville, Reference Somerville2013; Steinberg, Reference Steinberg2008). This increased focus on reward seeking in turn leads to greater risk-taking behavior (Chein et al., Reference Chein, Albert, O’Brien, Uckert and Steinberg2011; O’Brien et al., Reference O’Brien, Albert, Chein and Steinberg2011). In offline contexts, peer presence is a fairly objective variable (for both adolescents themselves and inquiring researchers), but many of the features of social media outlined in the transformation framework (Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018a) may amplify this experience. The availability and the publicness of social media means that peers can be “present” even when the adolescent is physically alone. Furthermore, the quantifiability of these networks, with a numeric quantity of followers and likes, could intensify peer influence. Recent fMRI studies have found that the neurological activation patterns underpinning peer influence when peers are physically present (Chein et al., Reference Chein, Albert, O’Brien, Uckert and Steinberg2011, Steinberg, Reference Steinberg2008) also occur when peers are “present” via Instagram (Sherman, Hernandez, et al., Reference Sherman, Hernandez, Greenfield and Dapretto2018; Sherman et al., Reference Sherman, Payton, Hernandez, Greenfield and Dapretto2016), and the impact of digital peer influence is stronger for adolescents compared to young adults (Sherman, Greenfield, et al., Reference Sherman, Hernandez, Greenfield and Dapretto2018).

The studies highlighted above suggest that social media can extend the reach of peer influence beyond physical presence and interaction with peers. Future research can leverage the networked data available on these platforms to better understand the role of proximal and distal peers in influencing adolescents’ behavior, and to operationalize different levels of peer connection and degrees of separation from each other in more detailed ways. For example, frequency of communication with a peer or even frequency of viewing a peer’s posts might objectively and accurately assess proximity to that peer. Alternatively, metrics used in social network analyses such as network closure and centrality can be used to more clearly define proximal and distal peers (Hanneman & Riddle, Reference Hanneman, Riddle, Scott and Carrington2011). This would allow researchers to go beyond simply asking adolescents to identify and rate their friends and peers, to directly assess with whom an adolescent digitally interacts and is connected. Directly assessing interactions (and observation) at the network level could greatly enhance our understanding of peer influence for a variety of important variables such as mental health, academic performance, and body image issues.

Social Connectedness and Isolation via Social Media

The role of social media in promoting (or inhibiting) social connectedness has received increasing research interest over the past several years. Social connectedness and a feeling of belonging is one of the primary benefits of peer relationships during adolescence, promoting positive psychosocial outcomes (Bradley & Inglis, Reference Bradley and Inglis2012) and protecting against both externalizing and internalizing problems (Newman et al., Reference Newman, Lohman and Newman2007). As social media and digital communication increased in popularity, there was a great deal of speculation about whether these technologies would foster intimacy and connection with peers, or if the reductions in face-to-face interaction would actually diminish adolescents’ sense of belongingness with peers (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Ryan, Gray, McInerney and Waters2014). Some proposed that specific features of social media would provide opportunities to better connect with peers. In a series of interviews conducted with adolescents, Davis (Reference Davis2012) identified that frequent communication with friends through a variety of digital platforms promoted a sense of closeness with these peers. The ability to connect with peers despite physical distance is identified by adolescents as one of the primary benefits of digital communication (Ling, Reference Ling, Harper, Palen and Taylor2005). Indeed, adolescents exchange a great deal of emotionally supportive communication via social media (Siriaraya et al., Reference Siriaraya, Tang, Ang, Pfeil and Zaphiris2011), using these platforms to reach out to peers in times of need (Ehrenreich et al., Reference Ehrenreich, Beron, Burnell, Meter and Underwood2020).

Beyond using social media to directly interact with peers, there is also some evidence that posting broadly to social media platforms without directly connecting with a specific peer (such as a tweet or a status post on Facebook) can reduce loneliness in undergraduate samples (große Deters & Mehl, Reference große Deters and Mehl2013; Lou et al., Reference Lou, Yan, Nickerson and McMorris2012). These findings highlight that the availability of the peer network that social media affords adolescents translates into increases in connection and belongingness, and reductions in loneliness. Indeed, a meta-analysis examining 63 studies found that social media use was positively correlated with perceived social resources from peers (Domahidi, Reference Domahidi2018). Interestingly, a recent study examining specific features of social media platforms found that image-based platforms in particular (e.g., Instagram and Snapchat) reduced users’ loneliness (Pittman & Reich, Reference Pittman and Reich2016). The authors speculate that the emphasis on images facilitates the sense of a “social presence” with peers that is better able to promote connection, aligning with the perspective that the visualness of social media (Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018a) may be an important feature for subsequent research into the role of social media in connection.

In contrast to the potential benefits of social media on adolescents’ peer connection, a separate body of research has suggested that smartphones and social media use are actually reducing social connection and well-being, and account for overall increases in social isolation and loneliness among adolescents (Twenge, Reference Twenge2019). Population-level studies have indeed identified increasing trends in both suicidality and depression over the past decade (Mojtabai et al., Reference Mojtabai, Olfson and Han2016) that coincided with similar rises in cellphone ownership and social media use (Twenge et al., Reference Twenge, Joiner, Rogers and Martin2018). One meta-analysis found that social media use does indeed correlate with perceived loneliness (although the authors suggest that loneliness predicting social media use is the most likely direction of effect; Song et al., Reference Song, Hayeon and Anne2014). One large-scale cross-sectional study of young adults found that social media usage was a significant predictor of social isolation (Primack et al., Reference Primack, Shensa and Sidani2017), and a micro-longitudinal study also found that time spent on social media predicts momentary feelings of social isolation (Kross et al., Reference Kross, Verduyn and Demiralp2013). Furthermore, a few experimental studies have also supported the hypothesis that social media causally predicts maladjustment. College students who were instructed to limit their social media use to no more than 30 minutes per day reported lower levels of depression and loneliness compared to the control group (Hunt et al., Reference Hunt, Marx, Lipson and Young2018). Similarly, individuals randomly assigned to abstain from Facebook for one week reported being happier and less depressed by the end of the week (Tromholdt, Reference Tromholt2016).

Although the immediate and constant connection that social media provides is appealing to adolescents (Davis, Reference Davis2012), there is concern that time spent on these digital platforms comes at the cost of more intimate and socially valuable face-to-face time (Kraut et al., Reference Kraut, Patterson, Lundmark, Kiesler, Mukophadhyay and Scherlis1998). The conflicting evidence on the role of social media in supporting or inhibiting social connection likely reflects methodological limitations for disentangling direction of effect (but see George et al., Reference George, Beron, Vollet, Burnell, Ehrenreich and Underwood2021 and Twenge, Reference Twenge2019 for contrasting perspectives on this). However, it also likely reflects the reality that the way adolescents are using these technologies may be more important than the overall time spent online. In particular, it appears passive social media use (time spent scrolling through peers’ posts without actually interacting or engaging with peers) may be especially harmful for adolescents’ well-being and sense of connection, compared to actively engaging with peers via social media. Time spent passively viewing peers’ social media content indeed predicts reductions in perceived peer support (Frison & Eggermont, Reference Frison and Eggermont2015), increases in social loneliness (Amichai-Hamgurger & Ben-Artzi, Reference Amichai-Hamburger and Ben-Artzi2003; Matook et al., Reference Matook, Cummings and Bala2015) and a sense of disconnection from peers (Amichai-Hamgurger & Ben-Artzi, Reference Amichai-Hamburger and Ben-Artzi2003) that likely grows out of feelings of envy and negative social comparison (de Vries et al., Reference de Vries, Möller, Wieringa, Eigenraam and Hamelink2018; Vogel et al., Reference Vogel, Rose, Okdie, Eckles and Franz2015; Weinstein, Reference Weinstein2017).

In contrast to the consistently negative correlates of passive social media use, active social media use (posting and directly interacting with peers) appears to have much more positive outcomes. Adolescents’ public Facebook posts elicit positive feedback from peers, which in turn increases the perception of peer support (Frison & Eggermont, Reference Frison and Eggermont2015). Similarly, experimentally increasing the frequency of posting publicly on Facebook reduced loneliness among college students (große Deters & Mehl, Reference große Deters and Mehl2013). Social media can also facilitate more private, dyadic interactions among peers, which in turn predicts social connection and support (Frison et al., Reference Frison, Bastin, Bijttebier and Eggermont2019; Frison & Eggermont, Reference Frison and Eggermont2015). It is not surprising that the opportunities for actual peer interaction (active use) promote feelings of connection and support among adolescents; indeed this was identified by adolescents as a primary benefit (Davis, Reference Davis2012). However, the conflicting findings between social media contributing to connection versus isolation highlights the importance of how adolescents are using these media. Future research must continue to focus on the specific online behaviors and usage patterns that foster connection, rather than simply assessing the amount of time spent using these platforms. The transformational framework model (Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018a) may be especially useful in disentangling the conflicting findings that have emerged in this research area. By focusing on the specific features of social media platforms that may be shaping peer interactions in these contexts, researchers can better understand what promotes a sense of connection and peer support, and what may undermine it.

Popularity and Social Status

Because of its highly public nature and constant availability, social media may be especially important in shaping adolescent social status (Nesi & Prinstein, Reference Nesi and Prinstein2019). Although social status has always been an important component of adolescent peer relationships (Harter et al., Reference Harter, Stocker and Robinson1996), social media both intensifies that importance and salience of peer status, and also provides new tools for managing and promoting status (Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018b). The quantifiability of social networks makes social media especially important for adolescents’ perceptions of status. Adolescents are highly aware of a variety of social media metrics assessing popularity (e.g., number of friends, number of likes or retweets; Madden et al., Reference Madden, Lenhart and Cortesi2013).

Indeed, the preoccupation with popularity on social media may have reframed adolescents’ traditional desire for popularity into aspirations for fame and stardom. Content analysis of movies and television viewed by adolescents has found that fame is increasingly portrayed as an important – and achievable – goal (Uhls & Greenfield, Reference Uhls and Greenfield2012), and adolescents who use social networking sites more frequently report a greater emphasis on the value of fame (Uhls et al., Reference Uhls, Zgourou and Greenfield2014). This emphasis on fame is somewhat attributable to the rise in popularity of reality television, wherein “ordinary people” ostensibly become famous for simply living their day-to-day lives (Rui & Stefanone, Reference Rui and Stefanone2016). But adolescents are also highly cognizant of the potential to achieve celebrity simply by acquiring enough social media followers (e.g., “Instagram famous”; Marwick, Reference Marwick2015).

Although social media has made peer status and popularity much more salient, it has also provided a variety of tools adolescents can use in their attempt to improve their status. Prior to the advent of social media, many adolescents no doubt spent their free time envisioning moving up the social hierarchy. However, with the help of smartphones and social networking sites, adolescents can actively work toward improving their number of friends, and curating their self-presentation at all times. Adolescents are quite strategic in leveraging social media to promote a positive and popular image. Many adolescents go to great lengths to ensure that their self-presentation on social media receives positive peer response, including taking numerous photos to select the best image for posting (Yau & Reich, Reference Yau and Reich2019), heavily editing photos to present an attractive image (Bell, Reference Bell2019), curating the activities they disclose to create a fun and glamorous identity (Fardouly & Vartanian, Reference Fardouly and Vartanian2016), and timing posts to maximize peer likes (Nesi & Prinstein, Reference Nesi and Prinstein2019). Indeed in her analyses of adolescents’ digital presentations, Marwick (Reference Marwick2013) suggests adolescents are engaging in “self-branding,” designed to market themselves using techniques similar to consumer products.

Although social media may provide a variety of new tools for managing one’s social status, that does not mean that all adolescents leverage social media to achieve higher status. Using social media in ways that will promote one’s social status requires a significant amount of social competence (Reich, Reference Reich2017) and a great deal of effort (Yau & Reich, Reference Yau and Reich2019). Popular adolescents are more likely to engage with their peers in ways that will promote their existing status, including both positive and aggressive behaviors. Furthermore, popular adolescents who are better able to self-monitor and regulate the online interactions are less likely to be the target of cybervictimization (Ranney & Troop-Gordon, Reference Ranney and Troop-Gordon2020).

Opportunities and Challenges for Studying Peer Relationships in Digital Communication

As social media increases as an important context for adolescents to interact with their peers, it presents both opportunities and challenges for researchers seeking to better understand peer relationships. Perhaps the greatest advantage of social media is that it permits researchers to connect with adolescents where their peer interactions are unfolding. While observing peer interactions used to require artificial lab settings (Piehler & Dishion, Reference Piehler and Dishion2007) or naturalistic observation that was restricted in time and location (Snyder et al., Reference Snyder, McEachern and Schrepferman2010), researchers can now potentially observe peer interactions in digital spaces unobtrusively for extended periods of weeks, months, or years (Hendriks et al., Reference Hendriks, Van den Putte, Gebhardt and Moreno2018; Underwood et al., Reference Underwood, Rosen, More, Ehrenreich and Gentsch2012). Furthermore, because much of adolescents’ digital communication is centered around their smartphones, a variety of additional data collection technologies can be connected with peer relationships and interactions, including ecological momentary assessment (Duvenage et al., Reference Duvenage, Uink, Zimmer‐Gembeck, Barber, Donovan and Modecki2019), geolocation (Boettner et al., Reference Boettner, Browning and Calder2019), and even physical functioning such as sleep patterns (George et al., Reference George, Rivenbark, Russell, Ng’eno, Hoyle and Odgers2019). These technologies provide researchers with a unique opportunity to stitch together a more comprehensive understanding of how peer relationships are impacting adolescents’ functioning and development.

Although the potential for these research methods is truly exciting, they are not without challenges and risk. First, there are important ethical considerations for researchers to capture the volume of data available in adolescents’ digital spaces. Although adolescents seem fairly comfortable with digital observation (Meter et al., Reference Meter, Ehrenreich, Carker, Flynn and Underwood2019), capturing digital communication nonetheless involves novel ethical considerations. Because this data collection can be conducted subtly from smartphones and social media apps, it is important that researchers clearly explain the details of digital data collection. Similarly, since social media data is inherently networked information, challenges arise for navigating when it is necessary to obtain peer consent (and whether that is even possible). This may require a dialogue with IRBs and granting institutions to better reflect the digital contexts in which adolescents live their lives. With tens of millions of adolescents permitting third parties to observe their social media data, these research activities are likely the very definition of minimal risk (see Ehrenreich et al., Reference Ehrenreich, George, Burnell and Underwood2021 for a discussion about this).

Another challenge for researchers is understanding the hidden, guiding hand of the algorithms that decide what is presented on social media platforms. These algorithms constantly evaluate the adolescents’ social media behavior to provide a stream of content tailored to the adolescent (and the marketing forces underlying many of these platforms). The role of these artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms obfuscates peer processes occurring in these platforms. For example, one long-running research inquiry has examined whether adolescents’ similarity to peers is best explained by socialization (learning how to behave from our peers) or selection (choosing peers who behave as we do). Evidence suggests that both of these processes likely work in tandem: adolescents select peers who are similar to them, who in turn further socialize their attitudes and behaviors. However, on social media these two processes become further intertwined (and blurred), as the content an adolescent views and posts themselves will in turn affect who and what is highlighted in their social media feeds. In this way, the content that is socializing the adolescent is also being used to select the peers who will be suggested to them or featured on their feed, and the selection of this network is in turn dictating what content will be presented (and will thus socialize the adolescent further). And all of these “decisions” are being conducted by computer algorithms that are likely hidden to the adolescent. Indeed, much of TikTok’s explosion in popularity during 2020 is attributed to the advanced artificial intelligence recommendation engine that rapidly tailors what videos are suggested based on the user’s previous preferences (see Wang, Reference Wang2020 for an overview of this technology). Much of the research outlined above highlights investigations into how social media features and content impact adolescents peer relationships. But why adolescents are exposed to features and content (e.g., why this specific video is presented at the top of their feed) is being guided by algorithms that are likely poorly understood by both adolescents and developmental scientists.

Future Directions

In their presentation of the transformational framework, Nesi and colleagues (Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018a, Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018b) highlight seven features of the social media context that are important to understanding how peer relationships operate in these environments (asynchronicity, permanence, publicness, availability, cue absence, quantifiability, and visualness). Future research must move away from examining specific social media platforms, and instead focus on their features. Not only do social media platforms rise and fall in popularity, but they also change their form and features over time. Not only is Facebook less popular among adolescents than it was in 2012 (Rideout & Robb, Reference Rideout and Robb2018), but the platform itself is also quite different, with new features constantly being added. By focusing on features of social media that can be assessed on a variety of platforms (e.g., the emphasis on visual content versus textual, the degree of asynchronicity; Nesi et al., Reference Nesi, Choukas-Bradley and Prinstein2018a), researchers can better understand how the broader social media context is shaping adolescents’ peer relationships, and these impacts can be assessed more consistently across time.