In November 2012, Xi Jinping officially became general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the country’s “first-in-command” (yibashou, 一把手). Soon after entering office, as a precursor to a broader and bolder anticorruption campaign, Xi initiated a campaign to combat government waste, with a particular emphasis on excessive eating and drinking at official banquets. The campaign was part of a larger initiative to improve cadre culture and reduce negative perceptions of government leaders, particularly at the local level.

Prior to Xi’s campaign, in September 2012, I arrived in China to conduct fieldwork in central Anhui Province and coastal Jiangsu Province on the underlying causes of county-level developmental variation, with a particular focus on three pairs of counties situated directly across from each other on the shared provincial border. During this first phase of fieldwork, the developmental divergence between the three Jiangsu counties and the three Anhui counties was readily apparent in industrial and urban development as well as in the attitude of local cadres. Despite sharing similar geographic and cultural histories, and despite having similar levels of wealth and industrialization in the mid 1990s, the Jiangsu counties now outshined their Anhui counterparts. Yet a common theme continued to characterize all six counties: feasting was a no-holds-barred exercise in over-ordering and general gluttony.

I returned to the same six counties in April 2013 for a second round of fieldwork and rapidly discovered a highly indicative change: feasting culture in the three Anhui counties remained unchanged, but feasting culture in Jiangsu had evolved. While officials still tended to over-order, in Jiangsu they made a point of referencing Xi’s dictum and doggy-bagging every unfinished dish. In Anhui, references to Xi were often made as well, but these references were followed by guffaws, not “to-go” bags.

I will argue in this book that what may at first seem like a trivial throw-away comparison represents a larger pattern of divergent cadre behavior, with important developmental implications. Jiangsu’s cadre promotion institutions have created pro-growth incentives for county leaders, and these leaders have translated their personal promotion incentives into bolder and more creative local development ideas as well as stricter control of local cadres in an effort to improve local investment environments. In Anhui, provincial authorities have been more concerned with stability maintenance (weiwen, 维稳) in local counties, leading to less courageous and less innovative county-level approaches to governance and economic policy. Largely as a result of these contrasting provincial emphases, counties in Jiangsu have vastly outperformed their Anhui counterparts since the mid 1990s, in terms of both economic and institutional development. In the six case study counties, the three counties in Jiangsu were on average slightly poorer than their three Anhui counterparts in 1994, the first year of the analysis; by 2007 they were over 60 percent wealthier. Although not the only factor explaining these outcomes, I argue that different governance and growth environments influenced by provincial variation in promotion emphases explain a significant share of the divergence.

Explaining the Developmental Orientation of Local Governments

The developmental orientation and effectiveness of China’s local governments in recent decades presents a quandary. Local governments have intervened frequently in local economies, with rampant opportunities for rent-seeking and inefficient obstruction of markets. Corruption has been widespread, and the incidence and perceptions of corruption increase at lower levels of government. And yet in the past 35 years, increased levels of decentralization have been accompanied by the highest sustained economic growth in modern economic history. During this “growth miracle,” many governments have had “helping hands” that benefit local businesses and help produce local growth. Other local governments have instead wielded “grabbing hands” that prey on local residents and businesses and stunt economic development. This variation in local government behavior is reflected in economic outcomes: although China as a whole has grown rapidly, this growth has been uneven. China’s richest county is over 100 times richer in per capita terms than its poorest county, the difference between Singapore and Liberia.

Existing theories go a long way in explaining the pro-development orientation of China’s local governments; they also go a long way in explaining predatory behavior. Yet these theories do not sufficiently explain the variation in behavior across local governments. As I discuss below, many of these existing theories concentrate on the incentives created by decentralization. For instance, theories based on fiscal federalism highlight the incentives for revenue maximization at the local level as spurring developmental approaches to nurturing local industry. Alternatively, theories based on implementation bias and authoritarian fragmentation that focus on pathological local government behavior highlight the lack of control over local actors within a highly decentralized system. These models do not focus on variation beyond that created by underlying economic conditions created by history or geography: in other words, local governments may be a priori pro-development or corrupt due to a combination of fiscal decentralization and political centralization, but the consequences of these incentives vary with initial conditions.

This book seeks to explain the variation in local government behavior that is left unexplained by existing theories. By focusing particular attention on the economic and institutional roles played by local leaders, I explain why so many governments have had “helping hands,” and why other local governments have not performed similar roles. I argue that significant variation in developmental orientation, and thus developmental outcomes, arises as a result of regionally varying incentives for promotion faced by county leaders as well as the formal and informal institutional roles that these leaders play.

Decentralization, Federalism, and Developmentalism

A key theme of the reform-initiating 11th Central Committee Third Plenum in 1978 was to devolve economic power to localities. Following the Plenum, local economies grew rapidly. Improvements in agricultural productivity gave way to rapid growth of local industry, particularly in township and village enterprises (TVEs).Footnote 1 While a conventional view sees China’s growth as a market-driven process resulting from a relaxation of government controls, a more compelling understanding of China’s growth attributes rapid growth to an increasingly pro-development orientation of many local governments.Footnote 2 With decentralization in a state-dominated economy, local governments in China have assumed highly interventionist roles, often taking on characteristics of a local developmental state.Footnote 3 Local governments often have more direct control over the economy than national counterparts, and the interventionism of Chinese local governments seems to increase as one moves down the administrative hierarchy. In one of the most cited accounts of developmentally minded local governments in China, Jean Oi’s “local state corporatism,” local governments act like corporations in their management of state firms while utilizing a “combination of inducements and administrative constraints characteristic of a state corporatist system” to both encourage and control the private sector (Oi Reference Oi1999, 99). The local developmental state idea in China also finds a champion in the discussions of local development “models,” and particularly the South Jiangsu or “Sunan” model (sunan moshi, 苏南模式).Footnote 4

Analyses of China’s growth often attribute this local “developmentalism” to incentives for revenue maximization following from increased fiscal decentralization. In the 1980s, the Party-state devolved expenditure and revenue collection authority to local levels in order to promote growth and facilitate the transition to a market economy (Shirk Reference Shirk1993).Footnote 5 Consequently, according to “market-preserving federalism,” the central government committed itself to fiscal reforms that allowed local governments to keep marginal revenues, aligning local government incentives with revenue maximization and leading to pro-market and pro-growth policies and behavior (Montinola, Qian, and Weingast Reference Montinola, Qian and Weingast1995). Federalism induced competition among jurisdictions, leading to experimentation and imitation and increased factor mobility through competition for capital and migrant labor.Footnote 6

Scholars in more recent years have questioned the fiscal federalism framework. Fiscal federalism “with Chinese characteristics” helps induce interjurisdictional competition, but without political centralization governments are as likely to have corrupt “grabbing hands” as developmental “helping hands,” regardless of revenue imperatives.Footnote 7 As per Robert Klitgaard’s famous formula, “corruption equals monopoly plus discretion minus accountability”: with increasing discretion as a result of decentralization, failure to increase accountability will tend to result in increased corruption, all else equal (Klitgaard Reference Klitgaard1988, 75). Arguments that fuse local economic autonomy with enhanced political centralization thus have more explanatory power in terms of the China local growth success story. Xu (Reference Xu2011) and Landry (Reference Landry2008) describe a decentralized authoritarian regime that combines political centralization with economic decentralization, helping to explain both the alignment of local incentives with national goals as well as the responsiveness of localities to national reforms, albeit with “implementation bias.”Footnote 8 In China’s economically decentralized and politically centralized regime, officials are upwardly accountable, with little direct downward accountability above the village level. The key means by which the CCP maintains political centralization in an economically decentralized state is hierarchical control through personnel management. During the reform era, explicit rule-based personnel management has evolved considerably. Administratively, since the late 1980s and particularly the mid 1990s, the center has attempted to formalize and control the cadre management system through increased institutionalization.

Institutionalization of cadre management enables the central government to transmit priorities throughout the administrative hierarchy through control over personnel decisions. This hierarchical personnel management system enables yardstick competition for advancement between local leaders, and there is considerable evidence that the CCP emphasizes economic growth in these performance contracts.Footnote 9 Indeed, the “GDP worship” of local officials is often perceived as common knowledge (Zhuang Reference Zhuang2007), and many studies have uncovered a relationship between growth and promotion, implying that performance management serves an effective development role.Footnote 10 This is the basis of the “tournament promotion” (jinsheng jinbiaosai, 晋升锦标赛) hypothesis: if growth is a key target, then meritocratic promotions will incentivize faster growth and enhance actual growth outcomes. According to this logic, the combination of economic decentralization and local policy autonomy with hierarchical compliance through political centralization helps provide an understanding for local developmentalism. In other words, economic and fiscal decentralization provide local governments with the ability to promote economic growth, and centralized political control provides local cadres with the incentive to promote economic growth.

Unexplained Regional Variation in Local Developmental Orientation

Yet a puzzle remains. Not all local government economic intervention has been positive; China has produced predatory local states that stand in stark contrast to the local developmental state idea. As Chalmers Johnson has noted, “The state can structure market incentives to achieve developmental goals … but it can also structure them to enrich itself and friends at the expense of consumers, good jobs, and development” (Woo-Cumings Reference Woo-Cumings1999, 48). Some “developmentally” minded behavior can quickly become predatory, and many behaviors in an interventionist mode can become more predatory as time progresses (Tsai Reference Tsai2002, 250). For instance, the Asian Financial Crisis led many Asian countries that had previously been considered “developmental” to be defined as “crony capitalist.” Variation can also be seen between local developmental states. Thun (Reference Thun2006) identifies three local development models in China: local developmental states, laissez-faire local states, and centrally controlled SOEs. More broadly, local governments often play distinctly nondevelopmental roles, and studies of local Chinese governments have utilized a wide range of definitions across the “developmental” and “predatory” spectrum.Footnote 11 Corruption is endemic, and much of this corruption is distinctly antidevelopment.Footnote 12

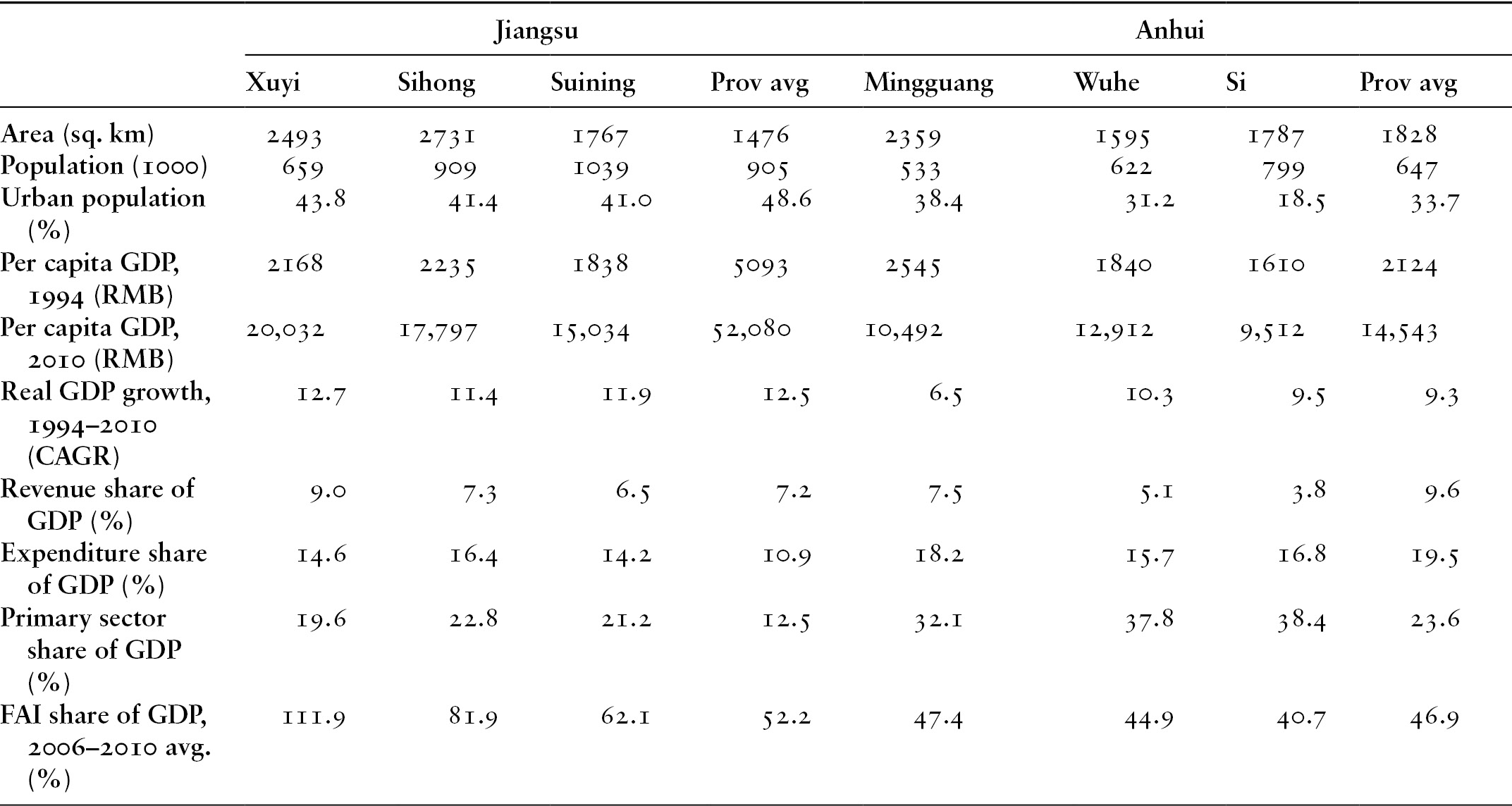

Why have some governments been more “developmental” than others? The authoritarian decentralization argument fusing economic decentralization with political centralization can explain away cases of predation and low growth as those in which political incentives fail to work. Local outcomes would be expected to vary if incentives for economic growth do not always travel down administrative ranks due to weak incentives or a lack of monitoring. However, this would only explain random variation in outcomes. As I show in this book, however, the variation in government approaches is systematic and varies by region. Current explanations for local developmentalism do not account for this systematic regional variation. Decentralization and local autonomy have resulted in high variation in county economic outcomes both across provinces and within provinces. There has been strong regionalism in economic outcomes; during most of the reform era, counties in coastal provinces have grown much faster than counties in other regions, and as a result poor counties are now concentrated in western and central provinces (see Figure 1.1). This economic regionalism can perhaps be explained by geographic conditions and local opportunity, but in addition to economic variation across regions, there has also been less-discussed variation in local governance across regions with regard to levels of corruption, institutional innovation, and government-business relations, as I demonstrate in later chapters (see Figure 1.1 for the regional contrast in Local Government Innovation Prize winners). I argue that these governance outcomes have been related to economic outcomes in virtuous and vicious circles; they are not merely consequences of growth outcomes, but also contributors to growth outcomes.

Figure 1.1. Regional variation in poverty and government innovation

Regional national poor counties (国家级贫困县) and Local Government Innovation Prize (中国地方政府创新奖) winners

As a consequence of regional variation, an analysis of local government development orientation must take a sub-national perspective. Given China’s vast regional differences in geography, culture, and institutions, applying a uniform national model to explain development outcomes is potentially misleading; this is especially true given that provinces and prefectures establish their own rules for fiscal transfers and criteria for personnel management. Much of the literature referenced above has a tendency to look at China as a single case rather than a set of regions/localities, which is problematic given that much national-level research necessarily involves national means, masking internal variation and leading to “mean-spirited” analysis (Snyder Reference Snyder2001, 98).Footnote 13 Sub-national comparison is thus important for studying China, a large country in which many policies and institutions have explicit regional variation, and in which the central Party-state often implements regional strategies that explicitly favor one region over another.Footnote 14 There is thus no reason to expect that the personnel management institutions and criteria for promotion that incentivize local leaders should be identical across regions and provinces; indeed, the central documents focused on local performance measurement are explicit about regional and local variation in targets.Footnote 15 Variation in incentives will lead to variation in outcomes, assuming that local actors have the autonomy and power to affect these outcomes; indeed that is the argument of this book.

Argument of the Book

Ask a Jiangsu county-level official why neighboring counties in Anhui have failed to develop, and nine times out of ten you will receive the same answer: “they’re backwards” (tamen de suzhi luohou, 他们的素质落后). These assertions of cultural determinacy are made boldly and flippantly, representing an apparent long-term historical stereotype. Yet there are no ethnic or religious differences between these bordering counties, and cross-border migration is common and relatively unimpeded. Indeed, in the late 1990s, local interviews in Southern Jiangsu pointed to culture as a major reason for Northern Jiangsu’s developmental challenge, in particular a “Central Plains stereotype” of a simple, satisfied people lacking drive (Jacobs Reference Jacobs, Hendrischke and Chongyi1999). As Northern Jiangsu has developed, the stereotype has slowly disappeared. However, while observed “cultural differences” seem to be a perceived consequence of economic development rather than a determinant of this development, “cadre culture” and local governance do differ in growth-affecting ways across the two provinces. Provincial institutions have interacted with local conditions to alter local institutional cultures. Cadres interact with each other, with businesses, and with local citizenry in ways that have been largely shaped by these provincial institutions. I argue that this behavior is a direct consequence of central policies that work their way down the administrative hierarchy in oft-unanticipated ways. The consequent corruption and low-growth economic environments, i.e., “backwardness,” result not from a lack of upward accountability and control, but rather from high levels of upward accountability with inconsistent objectives and no local oversight in the form of downward accountability.

More broadly, in this book I explain regional variation in county development outcomes by analyzing the relationship between provincial political institutions, local governance, and leadership roles. I focus on two related questions: What is the role of county Party secretaries in determining local governance and growth outcomes? Why do county Party secretaries emphasize particular developmental priorities? These questions are interrelated. Much of the variation in county economic outcomes, and particularly in pro-growth governance as a condition for high growth, stems from the differing roles and abilities of county Party secretaries in creating pro-growth institutional environments, and these leadership roles are themselves explained by the incentives given to county leaders by provincial authorities. Here, I briefly elaborate on these questions and provide the basic arguments that I will flesh out in later chapters.

What is the Role of County Party Secretaries in Determining Local Governance and Growth Outcomes?

As a starting point for analyzing how leader actions affect local governance and growth, it is essential to understand the variation in county growth and the relationship between governance and growth. The developmental state literature has identified many ways in which governments can intervene proactively and positively, and in China the importance of local governments is usually taken as a given.Footnote 16 Yet reform and openness along with socioeconomic development have altered the bases for local growth and the role of local governments. As China has recentralized fiscal revenues since the mid 1990s, the local revenue/expenditure gap has expanded and the importance of intergovernmental fiscal transfers for local government finances has increased dramatically, with important implications for expenditure priorities.Footnote 17 Fiscal reforms have not taken place in a vacuum: China’s socioeconomic conditions have changed rapidly, altering local incentives and capabilities. In particular, a growing private sector and reduced barriers to mobility have increased the relative importance of private mobile capital. As the private sector has grown, the role of local governments has necessarily changed, with less potential for direct management of firms. Fiscal reforms have increased incentives for local industrialization in order to generate local revenue sources, and the growth of private capital has enabled counties to attract industrial investment.

In this context, China’s counties, along with the country as a whole, have become more capital-intensive, particularly over the past decade, and investment has become the dominant source of growth. This compares to the 1990s, when labor and capital (particularly foreign direct investment) flowed to large cities, and county-level growth was led by productivity increases, predominantly through restructuring. As the ability to attract capital has become the most important determinant of county growth, the policies of successful local governments have focused on improving local investment environments. The most important determinant of the ability to attract investment has shifted from preferential policies, which have largely become equalized across counties and provinces, to county reputation, infrastructure, and service-oriented government, referring to government that is both pro-business in the sense of preventing government failures of corruption and excessive fee collection, and also service-oriented in its ability to assist firms through correction of market failures and more direct “developmental state”-type interventions.

I will argue that local leaders determine the effectiveness and direction of local governance. A strong individual role is an important, but unexplored, aspect of the pro-growth “authoritarian decentralization” literature described above. One well-known combination of economic/fiscal decentralization and political centralization applies a multidivisional “M-form” corporate hierarchy to China’s intergovernmental relations, which sees each branch (local government) division as a semi-autonomous unit under central control: the leaders of each branch compete in tournament competitions for recognition and promotion.Footnote 18 Note that the incentives and behavior of individuals within the branch are assumed to respond to the branch (local government) leader. In other words, local leaders are seen as branch CEOs. Oi (Reference Oi1999) describes the county Party secretary as “akin to a ‘hands-on’ chairman of the board, who sets policy direction, decides development strategy, and makes long-term plans.” Indeed, as a result of this interventionist role, county leaders are often referred to as “mom and dad officials” (fumuguan, 父母官) (Zhong Reference Zhong2003).Footnote 19 Yet while a strong role is observed and, often, assumed, implying that local Chinese leaders are likely to have systematic effects on economic outcomes, these effects have not been explored systematically in the literature in the way that CEO personal effects on firm outcomes have been.Footnote 20 Moreover, many studies see recent institutional trends in China as weakening the power of local Party secretaries, both as a consequence of strengthened bureaucracies and as a consequence of institutional reforms to limit individual power.Footnote 21

I argue instead that China’s local leaders continue to wield significant amounts of power through formal and informal institutions, and they are able to affect growth outcomes through both policy control and personnel control over the local bureaucracy. Local leaders affect growth outcomes through system bargaining for fiscal transfers and investments, and they can affect local investment environments as well as firm efficiency through direct firm-level interventions, control over development zone policies, and instilling more pro-growth local governance. Leaders’ personal characteristics determine their personal capacity to allocate resources, promote firm efficiency, attract investment, and bargain within the system. I propose that four broadly defined characteristics determine their growth-effectiveness: connections (system bargaining as well as relationships, or “guanxi,” with private businesses), creativity (local innovations and entrepreneurialism), control (ensuring cadre compliance and responsiveness), and courage (daring to implement controversial reforms). When leaders have connections, creativity, control, and courage, the counties they lead exhibit effective governance and have achieved economic successes; counties whose leaders do not have these characteristics have fallen behind.

Why Do County Party Secretaries Emphasize Particular Development Priorities?

If leaders differ in their approach to local economic growth, is this dependent simply on random variation in personal characteristics, or are leader actions and policies shaped by institutions? County Party secretaries decide whether and how to promote growth in order to maximize personal utility; in other words, they behave in a strategic way so as to maximize attainment of their preferences.Footnote 22 Constrained in the tools they can use, leaders’ solutions to personal utility maximization are based on the institutions in which they operate. Leaders both create and are subject to what Tsai (Reference Tsai2002, 14–18) calls the “local logics of economic possibility,” and their approaches to local growth and governance depend on evolving economic and fiscal constraints as well as personal incentives provided by cadre management systems. Officials in China are upwardly accountable, with little direct downward accountability; therefore, the personnel management system has become the most important institution for explicitly shaping local leader incentives.Footnote 23 Personnel management is designed to ensure compliance in a principal-agent framework with asymmetric information and limited monitoring capacity.Footnote 24 By helping the center achieve local compliance without the need for constant monitoring, the personnel management system provides a partial solution to the principal-agent problem.Footnote 25

Although the number of formal institutions and rules guiding China’s cadre management system have increased significantly over the reform period, questions remain regarding the degree to which these formal rules are followed as well as the priorities that are embedded in the system (direction of control) and the effectiveness of the system (degree of control). In terms of direction, performance evaluation systems need to be constructed with an eye towards specific goals, yet at the most basic level a debate remains over whether the underlying rationale behind China’s system is development or political control, or whether these two goals can exist simultaneously. Cadres also face incentives outside of the cadre management system. While ideology has decreased in importance, privatization in a growing economy has provided potential career possibilities for cadres who seek to “jump into the sea” (xiahai, 下海) of private business. These outside opportunities may have changed the efficacy of promotion incentives: although the cadre management system includes bonuses, monetary opportunities outside the system, particularly in wealthy regions, are no doubt greater.Footnote 26

Despite the changing socioeconomic environment, I argue that personnel management institutions are highly effective at transmitting political and economic priorities down the administrative hierarchy, and that the strength of the cadre management system in providing promotion incentives to county leaders has not declined as private sector opportunities have increased. Where many others agree that upward accountability remains effective, the originality of my argument is that although cadres are equally responsive to promotion incentives across regions, regional goals and incentives themselves differ, resulting in regional variation in cadre behavior and local development outcomes. In particular, I will demonstrate that the incentives provided to county leaders focus predominantly on CCP goals of growth and stability, with the emphasis differing by region: poorer central provinces have emphasized stability maintenance in their management of country-level cadres, while wealthy coastal provinces have emphasized economic growth.

To return to the overarching question: Why have certain regions in China had virtuous circles of growth and governance improvement while others have experienced vicious circles of low growth and poor governance? I argue that local leaders head highly interventionist governments and have large personal systemic effects on outcomes. They are incentivized by a hierarchical promotion system whose criteria are based largely on performance, but these performance criteria differ between regions and provinces as part of a national strategy to maintain both high rates of growth as well as social and political stability. This system has incentivized leaders in poorer regions to emphasize stability maintenance, leading to less effective government-business relations and lower institutional capacity, and it has incentivized leaders in wealthier regions to emphasize economic growth, which has in turn incentivized these leaders to pursue effective government-business relations and heightened control over local cadres. Given the high degree of power wielded by county Party secretaries, this incentive system has been partly responsible for producing regional inequality in outcomes. Three decades after Deng’s famous aphorism to let some get rich first, China’s hierarchical cadre management system is still helping some get rich faster.

Research Design

The arguments in this book are based on research findings from fieldwork in six bordering counties in Jiangsu and Anhui provinces as well as quantitative analyses using unique county-level economic and biographical data. In-depth county cases are complemented by broader provincial and nationwide analyses. The primary focus is on top leadership (county Party secretaries) in rural counties (xian, 县) and county-level cities (xianjishi, 县级市), excluding county-level urban districts (shixiaqu, 市辖区).Footnote 27 Counties are arguably the most important hierarchical level in China with regard to economic growth as well as political stability.Footnote 28 As the center of the rural-urban nexus, counties have comprehensive economic responsibilities and are also key for social and political stability, with county governments responsible for managing many of the major social contradictions in China’s development (Zhu Reference Zhu2011). Decentralization in the reform era has increased county government involvement in local economic and industrial development, and by concentrating local power has also strengthened the hands of local county Party secretaries.Footnote 29 These county “first-in-command,” or yibashou, are frequently seen as unchallenged bosses of “independent kingdoms”; the leader of no other level of administration in China has the same degree of unchecked power.

In selecting counties for analysis, I controlled for initial conditions, geography, culture, and history in order to examine how variation in provincial institutions leads to variation in local government behavior and developmental outcomes.Footnote 30 I therefore sought out a border between two regions in which counties on both sides of the border had similar levels of development in the early 1990s. Selection of a set of six bordering counties in northwest Jiangsu Province and eastern Anhui Province enabled matching along these terms.

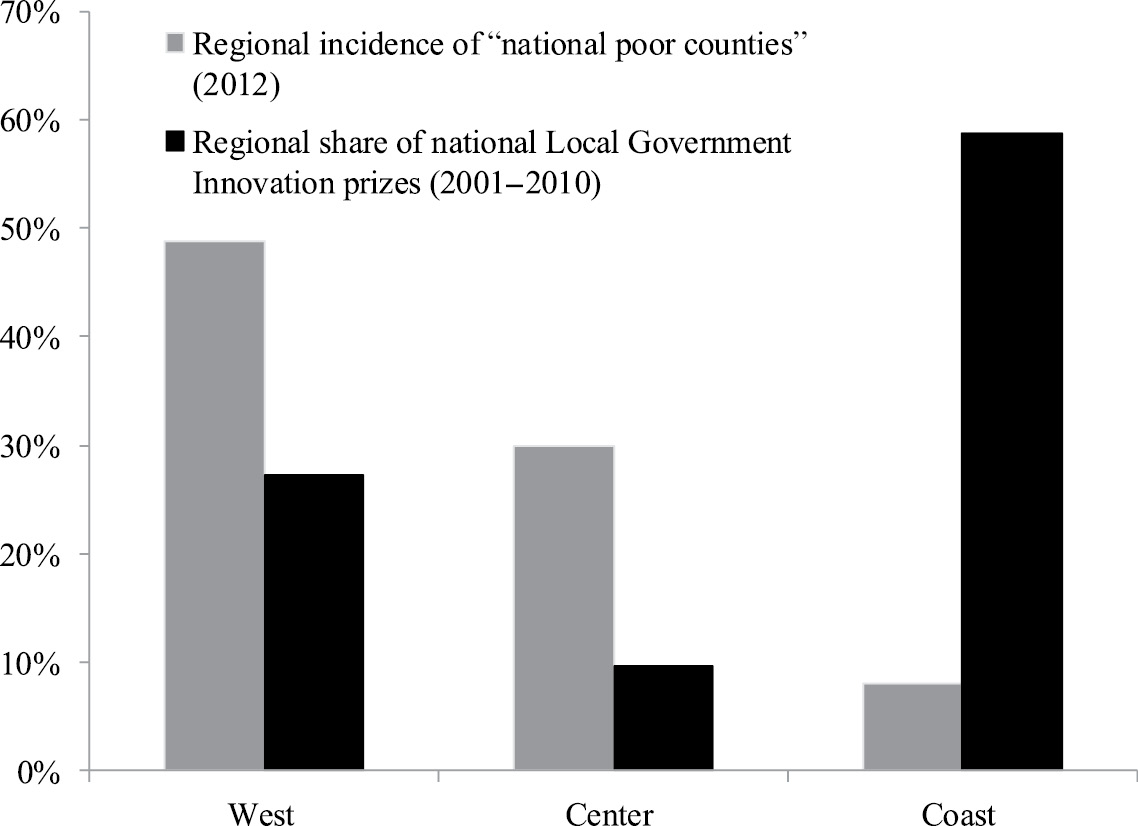

In selecting provinces, Jiangsu and Anhui are in many ways ideal comparative cases for county-level analysis. The two provinces have the same number of county-level units (105) and similar numbers of rural counties and county-level cities (58 and 61, respectively), as well as large populations (5th and 8th largest, respectively) densely packed in small areas (24th and 22nd in land area). Border regions in the two provinces have similar geography. Importantly, the two provinces are representative of China’s coastal and central regions. China’s economic regions are clearly defined, and provinces within regions tend to share highly similar economic outcomes.Footnote 31 As shown in Figure 1.2, the coastal region includes Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shandong, and Guangdong, and central China includes Shanxi, Anhui, Jiangxi, Hunan, Henan, and Hubei.Footnote 32 In 2010, these provinces were home to 59 percent of China’s population and accounted for 68 percent of China’s GDP. Respectively, the coastal region accounted for 48 percent of China’s GDP and 32 percent of the population, while the central region accounted for 20 percent of GDP and 27 percent of the population. With a per capita GDP of 20,749 RMB, Anhui in 2010 was slightly poorer than the central region average (24,123 RMB); with a per capita GDP of 52,642 RMB, Jiangsu was slightly richer than the coastal region average (49,194 RMB). In other words, the coast is approximately twice as wealthy as the center, and Jiangsu and Anhui are representative of this divergence.Footnote 33

Figure 1.2. Map of coastal and central provinces

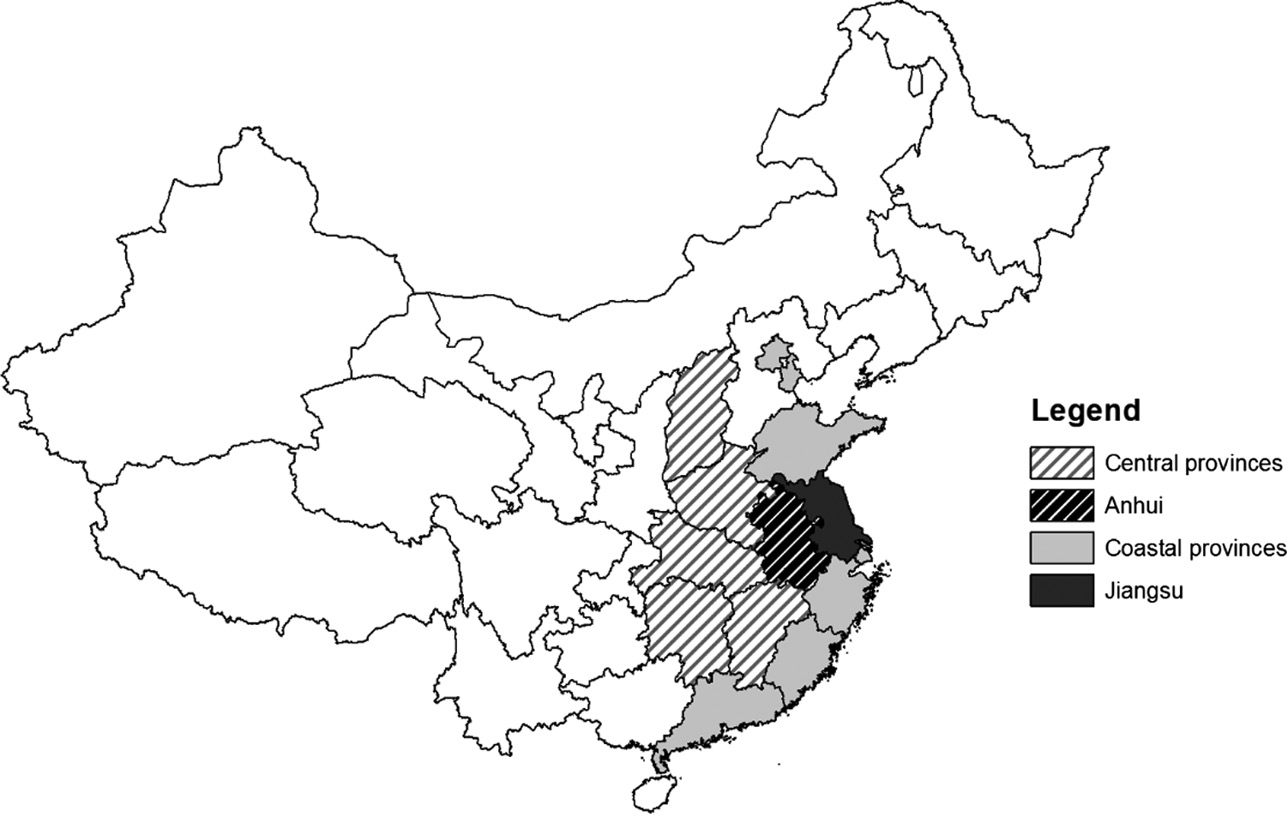

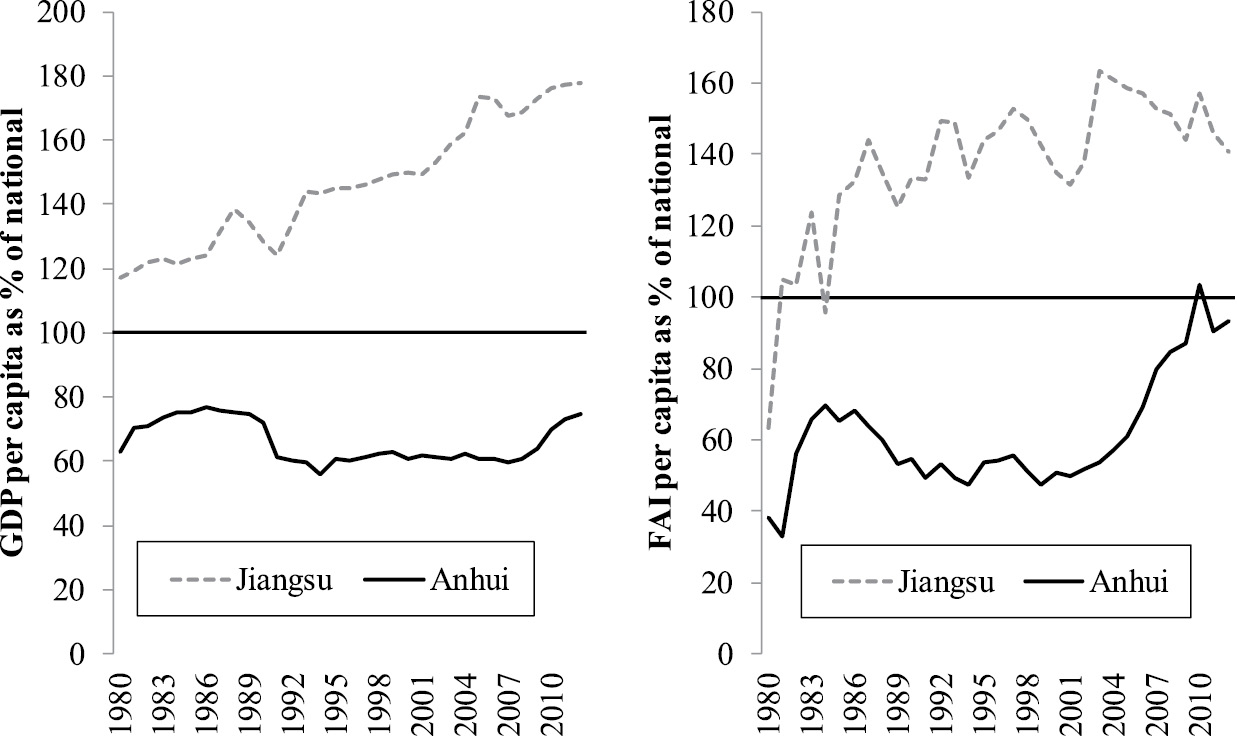

Although Jiangsu is much richer than Anhui overall, wide variance in sub-provincial county income means that there are many counties with similar per capita income and similar levels of industrialization. In 1995, counties in Southern Jiangsu were already comparatively rich, but income in Northern Jiangsu and Anhui was similarly distributed, as seen in the upper panel of Figure 1.3. However, the provinces diverged over the past two decades. By 2010, every one of the poorest category counties was in Anhui.Footnote 34 And while per capita growth and investment have consistently been above the national mean in Jiangsu, they have consistently been below the national mean in Anhui, although Anhui has closed the investment gap in recent years (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.3. Jiangsu and Anhui county income distribution, 1995 and 2010

Note: Cut-off values are calculated using Jenks (natural breaks) optimization method, which minimizes the average deviation from the category mean while maximizing each category’s deviation from other category means, seeking to minimize within-category variation and maximize between-category variation.

Figure 1.4. Per capita GDP investment in Jiangsu and Anhui, 1980–2012

Ratio of provincial to national GDP (left) and FAI (right) per capita (100 = equality), %

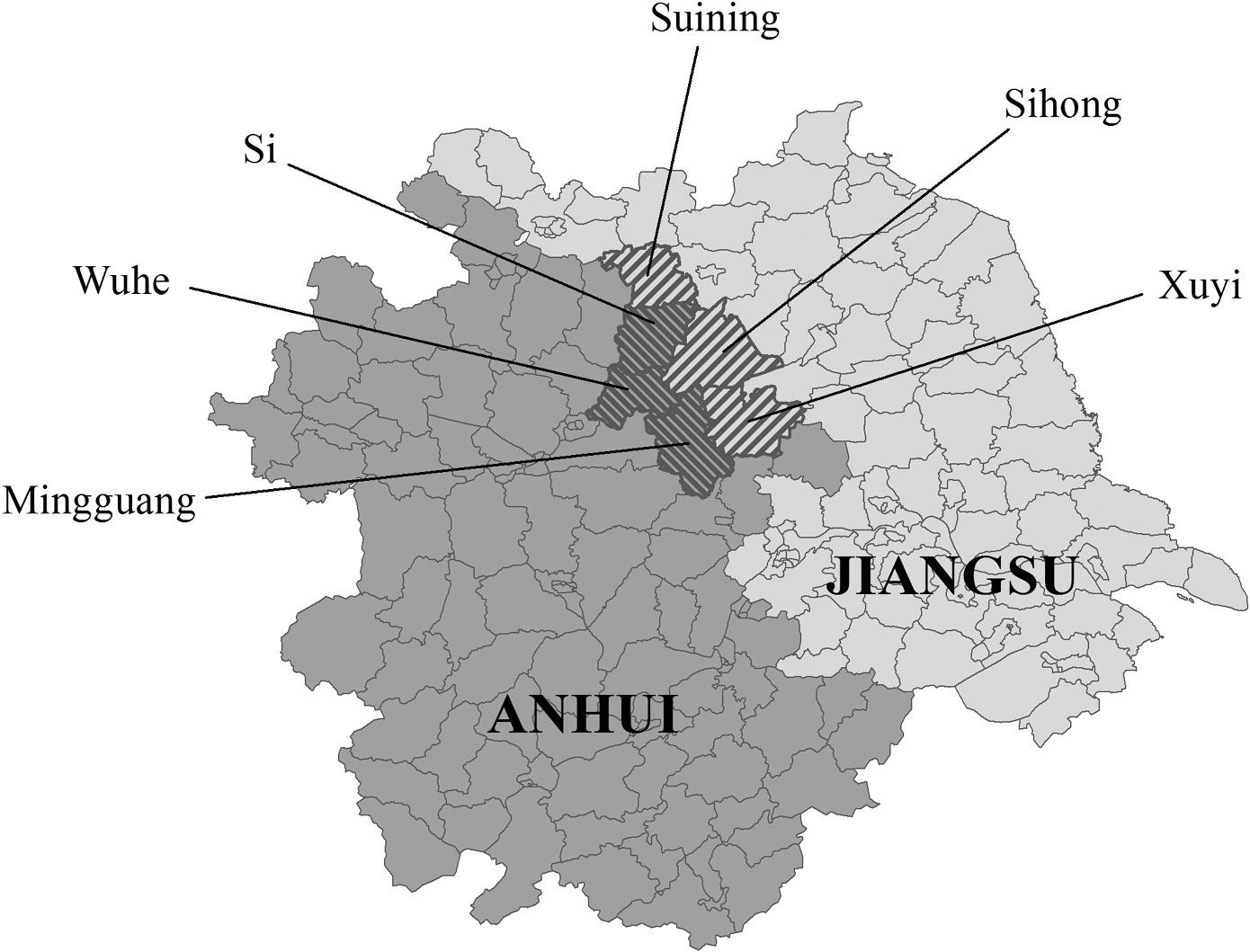

Within these two provinces, fieldwork focused on six neighboring counties in northeastern Anhui and northwestern Jiangsu.Footnote 35 The counties selected are “typical” within their province but also “most similar” (or matched) to the neighboring counties from the other province across dimensions of geography, shared history, and initial conditions at the start of the analysis in the mid 1990s.Footnote 36 All six counties are located along the shared provincial border. Interestingly, and of considerable importance for ruling out historic and persistent provincial differences between the cross-provincial county pairs, two of the three Jiangsu counties were historically part of Anhui. Mingguang City in Anhui and Xuyi County in Jiangsu were a unified single county (Xujia County) under Anhui jurisdiction until the mid twentieth century. Similarly, Sihong County in Jiangsu was formerly under Anhui jurisdiction. All six counties have similar climates, dominated by plains and surrounded by water. The geographic location of the six counties is shown in Figure 1.5.

Figure 1.5. Sample counties in Jiangsu and Anhui

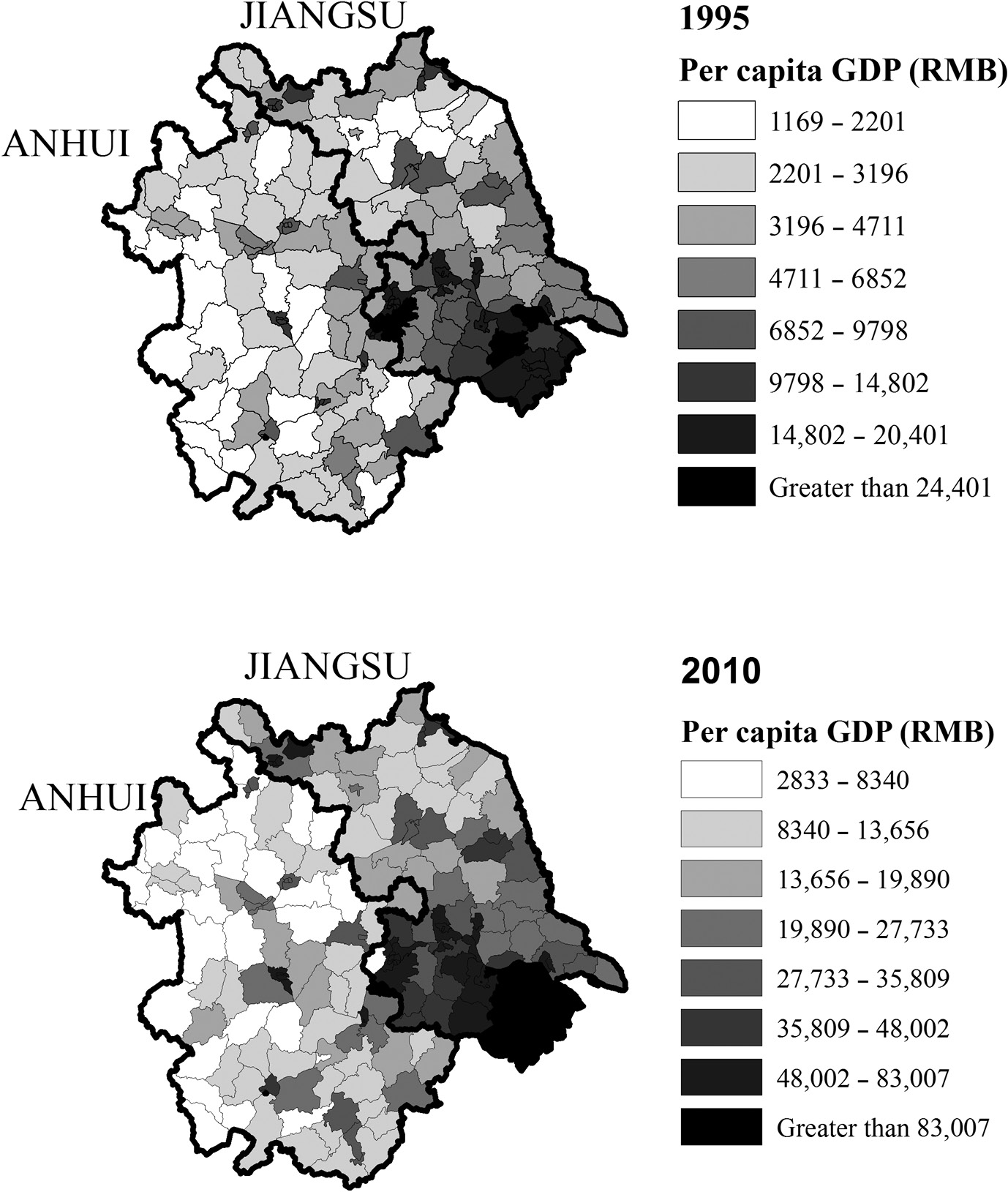

By selecting northwest Jiangsu counties and eastern Anhui counties, counties were matched across initial wealth, geography, and history, with variation coming from provincial institutions and local initiative, enabling an examination of how provincial institutions lead to variation in the dependent variable, economic and institutional development over 1994–2010. Looking at the data presented in Table 1.1 (or finding the counties in Figure 1.3), it is clear that in the mid 1990s, the three Anhui counties were on average wealthier than their Jiangsu counterparts. But by 2010, the Jiangsu counties were all much more economically successful. This is similar to the larger story of Jiangsu and Anhui. Both sets of counties have grown at or near their respective provincial averages over 1994–2010, although this growth rate has been lower in Anhui counties (9.2 percent) than Jiangsu counties (12.5 percent). Across many of the categories presented in Table 1.1, the Anhui counties match the provincial average, while the Jiangsu case counties are less developed than the provincial average (less urban, more agricultural, less wealthy), but similar to the average for Northern Jiangsu. In other words, these counties are not outliers, and are in fact fairly representative of their provinces (or, in the Jiangsu case, representative of a region within the province). While many counties in Anhui and Jiangsu could have been selected to match initial wealth, the geographic proximity of these six counties and thehistoric fluidity of the provincial border around these counties helps to allay concerns of divergent geographic, historical, and cultural influences.

Table 1.1. Case county statistics and provincial county averages, 2010 (except where noted)

| Jiangsu | Anhui | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xuyi | Sihong | Suining | Prov avg | Mingguang | Wuhe | Si | Prov avg | |

| Area (sq. km) | 2493 | 2731 | 1767 | 1476 | 2359 | 1595 | 1787 | 1828 |

| Population (1000) | 659 | 909 | 1039 | 905 | 533 | 622 | 799 | 647 |

| Urban population (%) | 43.8 | 41.4 | 41.0 | 48.6 | 38.4 | 31.2 | 18.5 | 33.7 |

| Per capita GDP, 1994 (RMB) | 2168 | 2235 | 1838 | 5093 | 2545 | 1840 | 1610 | 2124 |

| Per capita GDP, 2010 (RMB) | 20,032 | 17,797 | 15,034 | 52,080 | 10,492 | 12,912 | 9,512 | 14,543 |

| Real GDP growth, 1994–2010 (CAGR) | 12.7 | 11.4 | 11.9 | 12.5 | 6.5 | 10.3 | 9.5 | 9.3 |

| Revenue share of GDP (%) | 9.0 | 7.3 | 6.5 | 7.2 | 7.5 | 5.1 | 3.8 | 9.6 |

| Expenditure share of GDP (%) | 14.6 | 16.4 | 14.2 | 10.9 | 18.2 | 15.7 | 16.8 | 19.5 |

| Primary sector share of GDP (%) | 19.6 | 22.8 | 21.2 | 12.5 | 32.1 | 37.8 | 38.4 | 23.6 |

| FAI share of GDP, 2006–2010 avg. (%) | 111.9 | 81.9 | 62.1 | 52.2 | 47.4 | 44.9 | 40.7 | 46.9 |

In these counties, fieldwork consisted of six months of fact-finding interviews from October to December 2012 and April to June 2013. In addition to interviews with local officials and citizens, case study analysis also benefited from the collection of local documents and media related to finance, local economic conditions, and government work plans. Appendix 1 describes the interview process.

The qualitative case studies are complemented by quantitative analyses at both the national and regional level based on a unique dataset that includes general economic data, detailed fiscal data, census data, geographic data, and county leadership biographies. Appendix 2 describes data sources and presents descriptive statistics. The most original and important data are biographical data covering all counties and county-level cities in Jiangsu and Anhui over 1994–2010.Footnote 37 Biographical data include age, gender, ethnicity, year of party entry, hometown, education, previous employment experience, and subsequent employment. In total, the Jiangsu and Anhui database consists of 2023 county-year observations of county Party secretaries between 1994 and 2010. These data enable analysis of the sources of economic growth, the systematic economic roles of county leaders, and the promotion incentives faced by these leaders.

Structure of the Book

The book proceeds as follows. Chapter 2 analyzes county growth variance and provides evidence on the correlates of growth at the county level, demonstrating the importance of provincial policies and institutions. A discussion of China’s evolving factor markets, particularly for land and labor, demonstrates the developmental trajectory of China’s county growth over the reform era: from TVE-based rural industrial growth in the 1980s to city-led growth in the 1990s, followed by robust county development based on investment attraction over the past decade. Growth accounting exercises and growth regressions identify correlates of growth and support this general story. Chapter 3 then argues that much of the variation in economic outcomes across counties can be explained by differences in local governance. Government effectiveness determines the attractiveness of a region for mobile capital, and government approaches to private capital help boost productivity. Quantitative analysis highlights the relationship between government effectiveness and growth, while case studies highlight the pro-growth nature of combating government failures (corruption and excessive fees) and correcting market failures through proactive state-business relations.

Chapter 4 turns to the individual: China’s county Party secretaries are given high degrees of formal and informal power and autonomy, extending from cadre management to direct economic intervention. After demonstrating that county Party secretaries have systematic growth effects, the chapter looks at cases from the six sample counties to generate a framework through which local leaders affect local economic outcomes, finding that the most important local leader characteristics are connections, creativity, courage, and control. Chapter 5 looks at promotion incentives, finding that in Jiangsu and coastal counties more broadly, county leaders are promoted based on economic growth, while in Anhui and central provinces they are not. Moreover, growth itself is based on leader initiative rather than patron ties, implying that in China’s coastal areas, a “tournament promotion hypothesis” holds, meaning that yardstick competition of local leaders based on economic outcomes helps to explain rapid economic growth. Chapter 6 analyzes this dichotomous regional approach to promotions, providing further evidence that counties in Anhui and other central provinces emphasize stability maintenance over economic development. This surprising phenomenon can be explained by the developmental interaction and contradiction between the central Party-state’s dual objectives of stability and growth. I conclude by tying all of these findings together into a unified framework for local institutional and economic development, and by discussing the implications and importance of this research.