2.1 Introduction

This chapter provides a departure point for the academic journey in the rest of this book, by positioning ritual in pragmatics and defining its key pragmatic features.

The relationship between language use and ritual is far from being simple. Ritual practices appear in the whole spectrum of human interaction, including forms of behaviour which are polar opposites, such as highly formalised and institutionalised interaction1 versus socially controversial ritual insults and aggression.2 Further, ‘ritual’ has many popular meanings and interpretations, spanning ceremonies, through religious practices and in-group interactional habits, to manifestations of daily civility. Also, there is significant variation across linguacultures with regard to the degree of importance dedicated to ritual in its fully-fledged, ceremonial interpretation and the meaning of ‘ritual’. For instance, in Japanese, the word gishiki 儀式 is almost inseparable from conventional ceremonies and has an essentially positive meaning,3 while as Reference MuirMuir (2005) argues, in ‘Western’ linguacultures influenced by Latin, the word ‘ritual’ has a much broader semantic scope and it has a potentially negative connotation. At the same time, ritualists like Reference StaalStaal (1982) argue that humans are ‘addicted’ to ritual activity, i.e., ritual seems to equally prevail in any linguaculture irrespective of the connotation of the actual meaning of ‘ritual’ and comparable expressions. Due to such complexities, it may ever be a futile attempt to try capturing the relationship between ritual and language by relying on any popular definition of ‘ritual’. Instead, in the rest of this book I will use ‘ritual’ as a technical term, and I will often refer to ritual with the collective term ‘interaction ritual’, which is to be introduced in more detail in Section 2.2 of this chapter. Such a detailed definition is needed because, as was noted in Chapter 1, it may be problematic even to rely on a single academic working definition of ‘ritual’.

Ritual has a massive interface with many other pragmatic phenomena, in particular linguistic politeness, i.e., the ways in which language users build up and maintain their relationships, and impoliteness, i.e., the ways in which interactants disrupt and destruct their relationships. This is most likely the main reason why experts in the pragmatics of ritual have been reluctant to provide a single comprehensive definition of ritual.4 For instance, in historical pragmatic research in which ritual has been broadly studied, the concept of ‘ritual’ has remained vaguely defined from a pragmatic point of view (see e.g., Reference ArnovickArnovick 1984; Reference Bax, Jucker, Fritz and LebsanftBax 1999). The difficulty of defining ritual in pragmatics may also relate to the fact that ritual research has its roots in anthropology and sociology rather than linguistics. As an example, one may consider the ritual framework of Reference Durkheim and CosmanÉmile Durkheim (1912 [1954]), which has had an enormous influence on anthropology and sociology, and even on anthropological linguistics, but has had a limited impact on pragmatics. Of course, there are various important intersections between anthropology, sociology and pragmatics, but as far as mainstream pragmatics is concerned, such intersections have limited influence, and therefore so has ritual itself. For instance, Durkheim described ritual as a cluster of practices organised around sacred objects, by means of which communities are bound together and socially reproduce themselves. ‘Social reproduction’ is straightforward to interpret from a pragmatic viewpoint, even though it is not a linguistic concept, and it is not a coincidence that the working definition in Chapter 1 included this notion. However, while the Durkheimian notion of ‘sacred’ has been implanted into pragmatic thought through Reference GoffmanGoffman’s (1967) concept of ‘face’, sacredness in its fully-fledged ritual tribal/historical (non-urban) meaning is not a phenomenon that pragmaticians would normally study.

Such cross-disciplinary differences have terminological implications. Take the concept of ‘liminality’ as an example (see also Section 2.4). Liminality is a ritual term that describes the mental or relational changes that ritual triggers. ‘Liminality’ was introduced by the anthropologists Reference Van GennepArnold van Gennep (1960) and Reference TurnerVictor Turner (1969) into ritual research. Although ‘liminal’ is not unheard of in pragmatics, it has primarily been used by scholars such as Reference AlexanderAlexander (2004) working on the interface between pragmatics and sociology. While Senft and his colleagues (e.g., Reference Senft and BassoSenft & Basso 2009), as well as Reference BaxBax (2003a) carried out invaluable work enriching pragmatics with the terminological inventory of ritual research, their work has remained relatively marginalised in pragmatics. This does not imply that ritual terminology has been entirely ignored in the field. ‘Ritual’ has been featured as a simple concept in such important works as Reference AustinAustin (1962) and Reference Brown and LevinsonBrown and Levinson (1987). Further, notions such as rights and obligations – which is essential to ritual and which received impetus from the Wittgensteinian philosophy, most notably Wittgenstein’s notion of ‘language games’ – have been important in pragmatic inquiries.5 However, ritual terminology in its own right has been neglected in the mainstream of the field of pragmatics.

The aim of this chapter is to fill this knowledge gap by positioning and defining ritual from the pragmatician’s point of view, and also to provide an overview of the key terms of ritual research. The structure of the chapter is as follows. Section 2.2 provides a synopsis of how ritual has been seen in pragmatics, by describing the two main ways in which pragmaticians interpreted ritual phenomena. Here I also discuss the value of Goffman’s notion ‘interaction ritual’, which encompasses the above-outlined two major pragmatic views on ritual. Section 2.3 presents the concept of ‘ritual perspective’, that is, the idea that interaction ritual offers a powerful perspective through which one can approach and interpret language use across many linguacultures and context types. Finally, Section 2.4 provides a definition of the key pragmatic features of interaction ritual, followed by a conclusion in Section 2.5.

2.2 Pragmatic Views on Ritual

In the following, let us discuss how previous pragmatic research has interpreted ritual and why a Goffmanian view helps us to interconnect these interpretations.

2.2.1 Interpretations of Ritual in Pragmatics

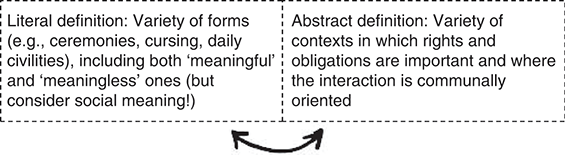

In pragmatics, ‘ritual’ has been interpreted in two different albeit closely interrelated ways: in a literal and an abstract sense. According to the first ‘literal’ definition, ritual encompasses a wide variety of behaviours, spanning ceremonies, through cursing, to manifestation of daily civil language such as Small Talk. Ritual in this sense includes both very ‘meaningful’ rites such as prayers, and ‘meaningless’ ones such as social niceties. ‘Meaningless’ here is borrowed from Reference EdmondsonEdmondson’s (1981) seminal work, describing the lack of referential message, which however does not correlate with a lack of social message. For instance, the remark ‘It’s nice weather, isn’t it’ is a typical ritual utterance, which does not say anything ‘actual’ but at the same time conveys an important social meaning. In the second more abstract sense, ritual encompasses any conventionalised interaction in contexts where rights and obligations are set and the interaction is communally oriented. For instance, ‘You are fired’ uttered by a manager is an Informative speech act which is typically ritual because it animates the voice of an institution, uttered by a speaker who is both a ratified ‘principal’ and ‘animator’ in Reference GoffmanGoffman’s (1979) sense, endowed with a right to produce this utterance. Figure 2.1 illustrates the above-outlined two definitions of ritual in pragmatics:

The boxes in Figure 2.1 have dashed lines because the two above-outlined definitions are not in contradiction: they simply interpret ritual from different angles, i.e., either through form (of behaviour) or context. Also, some phenomena such as ‘apology’ can simultaneously be interpreted in both these senses, e.g., as a form (speech act) realised in a ritual context and as a ritual context and a related activity which triggers some expected form of behaviour. As this book will show, these definitions of ritual trigger different data analytic procedures. The double-headed arrow in Figure 2.1 indicates that these definitions of ritual can – and are advised to – be used in combination.

I will consider how such combined research can be carried out in more detail later in this section. Yet, before so doing, let us discuss the trajectory of these two different but closely related interpretations of ritual in pragmatic research. In early pragmatic work in the 1980s, the concept of ritual emerged in studies on routinised language use, speech acts, politeness and discourse. Representatives of such research are Reference CoulmasCoulmas (1981), Reference EdmondsonEdmondson (1981) and Reference Edmondson and HouseEdmondson and House (1981) who all used ritual to discuss seemingly ‘empty’ but socially meaningful (and often ceremonial) communication. In their renowned framework of linguistic politeness, Reference Brown and LevinsonBrown and Levinson (1987) used the concept of ritual to capture ceremonial aspects of language use. For Brown and Levinson, ritual as a ceremonial phenomenon was such an important phenomenon that they opened their work with a reference to the seminal research of Durkheim. The following excerpt represents how ritual is typically used by Brown and Levinson:

Greetings and farewells, and in general rituals of beginning and terminating encounters often contain … bald-on-record commands. In Tzeltal we have:

… (43) ban. (farewell)

Go.

(44) naklan. (offer to visitor)

Sit down.

(45) solan. (trail greeting)

Pass.

Brown and Levinson included both macro–social and micro–in-group rituals in their discussion of the ceremonial aspects of politeness. For example, they drew attention to

a parallel between interpersonal ritual and institutionalized rites … [which helped them forming their] ideas about typical dyadic rituals of interpersonal communication [and which] suggest a startlingly simple theory of a symbolism of exchange.

Ritual also played an important role in later criticisms of the Brown and Levinsonian paradigm. In particular, East Asian critiques of Brown and Levinson – such as Reference IdeIde (1989) and Reference GuGu (1990) – used ritual data to argue against the validity of Brown and Levinson’s framework. For example, Ide used the following example to argue why, according to her, Brown and Levinson’s universalistic approach to politeness as a strategic form of behaviour is wrong:

#Sensei-wa kore o yonda

# ‘The professor read this.’

According to Ide, talking about a lecturer in Japanese triggers a ceremonial ritual style, and so speakers of Japanese are not free to ‘strategically’ use politeness as argued by Reference Brown and LevinsonBrown and Levinson (1987). In other words, Ide argued that certain ritual contexts preclude the use of strategic or ad hoc language use. Yet, as Reference Kádár and BaxKádár and Mills (2013) pointed out, East Asian critiques of Brown and Levinson did not attempt to systematically integrate their arguments into ritual theory, even though they used examples like the one above of a clearly ceremonial and ritual nature. Along with politeness researchers like Brown and Levinson, experts of various other pragmatic areas such as historical pragmatics (e.g., Reference BaxBax 2001, Reference Bax, Culpeper and Kádár2010; Reference ReichlReichl 2003) and second language (L2) pragmatics (e.g., Reference Keshavarz, Eslami, Ghahreman, Bardovi-Harlig, Felix-Brasdefer and Saleh OmarKeshavarz et al. 2006; Reference Bruti and WernerBruti 2018) also often defined ritual in a literal way, i.e., as a ceremony of some kind. For the ritual pragmatician, such studies represent a fundamental academic background because they show that the ceremonial and routinised aspects of interpersonal interaction are at least as important as free-flowing and often idiosyncratic conversation.

Pragmatics has also witnessed the development of another body of research on ritual where ritual tends to be interpreted in a more abstract sense – i.e., as a cluster of conventionalised practices – beyond what a lay person normally understands when using the word ‘ritual’. To the best of my knowledge, such research in pragmatics started with the seminal study of House who developed a ritual line of analysis and an essentially ritual concept – ‘standard situation’ (Reference House, Blum-Kulka, House and KasperHouse 1989) – to distinguish normative behaviour from politeness behaviour, without however explicitly pursuing interest in ritual. As Reference House, Blum-Kulka, House and KasperHouse (1989) pointed out, in standard situations, the interactants are bound by rights and obligations to produce and respond to utterances in certain preset ways. For example, a policeman is likely to produce the speech act Request ‘Please move your car’ to reprimand a driver parking in the wrong place, and the driver is likely to utter ‘Yes’ in response (instead of e.g., the Request for information ‘Why’). As House argues, such behaviour is very little (if at all) related to politeness but rather it is somehow preset and normative (i.e., ritual as now we would say) – an argument which was well ahead of its time! Later on, the above-outlined interest in context triggering ritual language use has gained momentum in North American pragmatic research on civility, in particular the work of Jeffrey Alexander and his colleagues (e.g., Reference AlexanderAlexander 2004; Reference Alexander, Giesen and MastAlexander et al. 2006). Recently, Reference HorganMervyn Horgan (2019, Reference Horgan2020) made a fundamental contribution to this line of research, by examining how breaches of civility indicate language user’s awareness of ritual contexts in their daily lives. Juliane House and myself pursued a somewhat different but closely related line of research as we examined how language use, in particular the choice of certain pragmatically loaded expressions, indicate awareness of the ritual frame and related contextual rights and obligations (e.g., Reference Kádár and HouseKádár & House 2020a; see also Chapter 8). Through this research we could identify how context triggers instances of language use which may not be called ‘ritual’ in the popular sense of the word, but which has all the key pragmatic features of ritual.

One may argue that pragmatic research not only encompasses but also encourages the co-existence of these two complementary views on ritual. Let us revisit here the previously mentioned ‘crossovers’ in the pragmatic study of ritual. Pragmatics has witnessed a surge of interest in aggressive ritual behaviour, starting with Reference Labov and LabovLabov’s (1972) seminal sociolinguistic work on ‘rude’ rituals. Typically, in such research scholars have examined rude (or at least ‘rough’) forms of pragmatic behaviour which may be described as ritual by some, but which may be too erratic and ‘mundane’ to be described as ritual in comparison to, for example, ceremonies or rites of civility. Also, unlike ceremonies, such rituals only gain a ritual function in specific contexts, which trigger ritual behavior, and so they are examples par excellence for a crossover between ritual as a form and ritual as a context. Let us provide some examples here. Reference RamptonRampton (1995) studied manifestations of ‘crossing’. ‘Crossing’

involves code alternation by people who are not accepted of the group associated with the second language they are using code switching into varieties that are not generally thought to belong to them.

Many forms of crossing are ritual: a typical example includes cases when students realise in-group ritual humour by mimicking a disliked lecturer’s manner of speech. In the study of such a case of language use, one may examine the ‘rite of crossing’ as a context, while one also needs to examine how certain forms of language use – which in themselves may not be ritual – operate in this context. In a similar vein, I also examined how seemingly erratic and aggressive language behaviour such as heckling in stand-up comedy and political speeches can be captured as a context and form of ritual if it is interpreted as part of a broader ritual contextual frame (see Reference KádárKádár 2017). Various other scholars followed the same train of thought in other related areas, such as the study of aggressive ritual socialisation both as a frame and as a form of behaviour (e.g., Reference Blum-KulkaBlum-Kulka 1990; Reference Kádár and SzalaiKádár & Szalai 2020).

2.2.2 The Goffmanian View: Interaction Ritual

We may contend at this point that pragmatics affords various definitions of ritual in a rather liberal way. Indeed, one can witness very little academic debate between pragmatic experts of ritual as regards the accuracy of their ritual definitions. This liberal attitude is different from how scholars of many other pragmatic phenomena have approached their object of research – as an example, one may refer here to fierce definitional discussions in linguistic politeness research (see e.g., Reference EelenEelen 2001). The reason why ritual pragmaticians have rarely (if at all) debated about the validity of their definitions may be partly due to the above-outlined lack of contradiction between various views on ritual, and partly due to the fact that the pragmatic worldview has been heavily influenced by Goffman’s ground-breaking work on ritual. In other disciplines, ritual theory is often attributed to the work of Reference Durkheim and CosmanDurkheim (1912 [1954]), and Goffman himself was influenced by Durkheim.6 However, Durkheim’s work has only had a limited impact on pragmatics (but see Reference Senft and BassoSenft and Basso 2009 cited above).7 Reference GoffmanGoffman (1967, Reference Goffman1974, Reference Goffman1983) demonstrated that rituals are not limited to sacred ceremonies, even though ceremonies are also very important parts of our modern life (consider, for instance, Reference CollinsCollins’s 2004 discussion on ceremonial smoking!). Rather, they include both ‘demarcated’ (Reference StaalStaal 1979) ceremonial events, originally studied in anthropology, and many seemingly ‘insignificant’ mundane events in urban lives, with more relevance for sociologists like Goffman himself. As Reference GoffmanGoffman (1983: 10) argues:

If we think of ceremonials as narrative-like enactments, more or less extensive and more or less insulated from mundane routines, then we can contrast these complex performances with ‘contact rituals’, namely, perfunctory, brief expressions occurring incidental to everyday action – in passing as it were – the most frequent case involving but two individuals.

With the diversity of ritual in mind, Goffman coined the term ‘interaction ritual’, which includes ritual both in a literal and an abstract sense, which are both present in many contexts in industrialised societies. I believe that Goffman’s term is particularly useful because it captures ritual as an interactional process, and also it describes ritual both as a form and as a context. Thus, the way in which ‘ritual’ is interpreted in this book is largely aligned to the Goffmanian worldview, even though I use ritual in a more specific sense than Goffman by attempting to pin it down through its pragmatic characteristics (see more below). For Goffman, ritual is broader than simple language use: it includes all routines of our daily lives including, for example, ‘addressing a person by name, making eye contact, [and] respecting someone’s space’ (see Reference Swidler, Schatzki, Knorr-Cetina and von SavignySwidler 2001: 98).

Similar to Durkheim, Goffman argued that the essence of interaction ritual is that it helps social structures to reproduce themselves (see also the working definition of this book in Chapter 1). Social groups conventionalise a wide variety of interactional practices to create an interactional order, underlied by an invisible moral order. In this book I define ‘moral order’ in the sense of Reference WuthnowWuthnow (1987: 14) who argued that moral order involves ‘what is proper to do and reasonable to expect’, i.e., it is a cluster of unwritten social mores and conventions which serve to maintain the interactional and broader societal order. Unlike the term ‘convention’ in pragmatics which is neutral, ‘moral order’ has an important judgmental facet. This definition of the moral order is essentially discourse analytic, and it differs from how this notion has been interpreted in conversation analysis.8

The fact that Goffman defined ritual as a highly variable phenomenon is logical if one considers that:

social ritual is not an expression of structural arrangements in any simple sense; at best it is an expression advanced in regard to these arrangements. Social structures don’t ‘determine’ culturally standard displays, merely help select from the available repertoire of them.

In sum, Goffman’s view provides a powerful foundation to study ritual. Further, building on Goffman allows us to develop a ritual perspective on language use. Goffman developed a range of concepts such as ‘face’, ‘demeanour’ and ‘deference’ which became the foundations of politeness theory (see Reference HaughHaugh 2013: 50). Yet, Goffman did not use the concept of ‘politeness’, and in the following I will discuss why viewing many instances of interaction as forms of ritual rather than politeness – i.e., adopting a ritual perspective in pragmatic research – is important.

2.3 The Ritual Perspective

Following Goffman’s above-outlined definition of interaction ritual, it is safe to argue that ritual is a phenomenon which is so relevant to our daily interactions that it provides a specific perspective for the scholar to look at language use itself. Adopting such a perspective is important because very many aspects of language use are ritual, even though language users themselves do not always realise that they are acting in a ritual way. While perhaps few pragmaticians would disagree with this claim per se, it is not without controversy because in pragmatic research ritual tends to be perceived as the ‘little brother’ of the much broadly studied phenomenon of politeness (and impoliteness).9 For example, Reference Brown and LevinsonBrown and Levinson (1987) have left the relationship between politeness and ritual largely intact beyond arguing that certain routinised manifestations of politeness are ritual. Many other scholars could be listed here – including both early and recent work such as Reference FergusonFerguson (1976), Reference HeverkateHaverkate (1988), Reference FraserFraser (1990), Reference Kerbrat-OrecchioniKerbrat-Orecchioni (2006), Reference TraversoTraverso (2006), Reference 234Ghezzi and MolinelliGhezzi and Molinelli (2019) and many others – but the main point is that ritual has been subordinated to politeness by practically all politeness researchers who discussed ritual phenomena. This is also valid to experts who focused on ritual in their work, such as Reference BaxBax (2001, Reference Bax, Culpeper and Kádár2010), Reference Held, Watts, Ide and EhlichHeld (1992, Reference Held2010), Reference OhashiOhashi (2008), Reference Paternoster and PaternosterPaternoster (2022), Reference Kádár and BaxKádár and Bax (2013), Reference Kádár and PaternosterKádár and Paternoster (2015) and others. I also followed a low-key approach to the relationship between ritual and politeness in my previous work (Reference KádárKádár 2017): instead of considering how ritual and politeness differ from each other, I tried to identify how certain aspects of politeness and impoliteness can be described as ritual.

2.3.1 Why Not Subordinate Ritual to Politeness?

Relating politeness and ritual is no doubt important because through considering this relationship one can gain insight into various issues surrounding politeness. An eminent example may be the study of Reference LeechLeech (2005; see also Reference Leech2007), who attempted to capture what brings together politeness in ‘Eastern’ and ‘Western’ linguacultures by proposing ‘a Grand Strategy of Politeness’. In explicating this concept, Leech used highly ritual examples, like the following:

Asymmetries of politeness: Politeness often shows up in opposite strategies of treating S and H in dialogue. Whereas conveying a highly favourable evaluation of H is polite, conveying the same evaluation of S is impolite. Conversely, while conveying an unfavourable evaluation of S is polite, giving the same evaluation of H is impolite… .

Almost as a technical term, I use the phrase courteous belief for an attribution of some positive value to H or of some negative value to S, whereas a discourteous belief is an attribution of some positive value to S or some negative value H. Compare, for example, the courteousness of (a) and the discourteousness of (b):

(a) You’re coming to have dinner with us next week. I insist!

(b) I’m coming to have dinner with you next week. I insist!

There are such asymmetries in Chinese and Japanese honorific usage:

Bìxìng wáng, nín guìxìng? 敝姓王, 您贵姓?

(My surname is Wang, your surname?)

(Namae wa) Buraun desu. O-namae wa?

(My name is Brown. And your name?)

What strikes the ritualist is that all the examples which Leech uses here are highly ritual, and while he does not mention the concept ‘ritual’ in his study, his examples show that ritual may be used as a phenomenon which interconnects pragmatic behaviour in typologically distant linguacultures.

Notwithstanding the importance of studying ritual through the lens of politeness, and politeness through the lens on ritual, in this book I take a different route because I believe that interaction ritual is potentially much more important than any other interpersonal pragmatic phenomena, including politeness. Therefore, in the following I focus on the benefits of an interaction ritual perspective on language use in comparison to the politeness perspective – without, however, arguing that these perspectives are incompatible. On the contrary, I believe that the ritual and politeness views are both important and complementary to each other, but the ritual view needs to receive more attention in pragmatics. Why is this so?

Consider the following utterance:

It gives me a great pleasure to welcome here as our guest this evening Professor Quatsch from the University of Minnesota Junior.

One may argue that here we have a polite utterance in hand. Although any utterance, including this welcoming, may be used in an idiosyncratic way as discursive politeness scholars such as Reference EelenEelen (2001) argued, most would agree that Example 2.1 occurs in a formal public event, and this public interpersonal scenario largely precludes any other use and interpretation of language than a default polite one.10 The speaker who utters the above welcoming may attempt to play on prosody or use other pragmatic phenomena to express that she actually dislikes the welcomed person, which then would be an idiosyncratic realisation of the welcoming.11 However, any such move would likely become salient and could potentially harm the speaker’s own face and reputation. So, when one encounters an utterance such as Example 2.1 uttered in an ordinary way, the question may ultimately emerge: is politeness a matter of interest at all when the speaker is socially dutybound to be polite (or impolite in other occasions)?

This is a rhetorical question, and the answer is meant to be ‘no’. This is why politeness research conventionally prefers studying data with a sense of individuality and ad hoc-ness rather than communal orientation, even when it comes to highly conventionalised phenomena, as otherwise there would be very little for the politeness scholar to look at. This is of course a rather oversimplified statement. While in the so-called ‘discursive’ research (see e.g., Reference MillsMills 2003) politeness has been interpreted on a strictly individual level, various politeness scholars such as Reference Blum-KulkaBlum-Kulka (1987), Reference TerkourafiTerkourafi (2001), Reference Culpeper and DemmenCulpeper and Demmen (2011), Reference HultgrenHultgren (2017) and others have studied conventionalised aspects of polite language usage. Also, many experts of politeness research considered communal aspects of politeness and impoliteness behaviour, including Reference CulpeperCulpeper (2005, Reference Culpeper2011) who considered such behaviour in ‘activity types’ and ‘frames’, Reference TerkourafiTerkourafi (2001) who discussed ‘frames’, and Reference Garcés-Conejos BlitvichGarcés-Conejos Blitvich (2010) who distinguished ‘genres’. However, even in such research, communally oriented behaviour has often been subordinated to individual behaviour, simply due to the focus on politeness. In other words, the aforementioned studies had more interest in ‘trends or preferences in the way people speak in different situations’ (Reference Culpeper, Terkourafi, Culpeper, Haugh and KádárCulpeper & Terkourafi 2017: 18) than in studying why and how certain practices and contexts through which social structures reproduce themselves prompt or even force people to follow certain tendencies of producing and evaluating language – a question which relates to the ritual view on language use. Accordingly, recent politeness inquiries considered the role of pragmatic conventions in language use, without however foregrounding the cohesion between these conventions, which is reasonable if one considers that the primary focus of politeness research is the language use of the individual.

One could argue that ritual has many shared characteristics with notions such as ‘activity type’, which was proposed by Reference LevinsonLevinson (1979) and which has been used in some work in politeness research. However, this is certainly not the case for various reasons. Activity type describes conventions of pragmatic behaviour holding for one particular context. Ritual, on the other hand, has many general pragmatic features which will be introduced later on in this chapter, and which characterise all ritual contexts and manifestations of ritual, i.e., ritual encompasses a much broader phenomenon than activity type.12 Furthermore, the fully-fledged study of ritual often assumes a bottom–up view on data, as this book will show, that is, one often first looks at ritual language use to identify various ritual contexts in which such language use occurs. This is different from how activity type has been used as a notion to capture language use in one particular context. Further, since activity type is chosen by the researcher, politeness scholars who used activity type often pursued interest in polite and impolite behaviour in incidents or case studies which are, for one reason or another, interesting for the researcher and salient for the participants, while there has been little appetite to study instances of ‘boring’ language use such as Example 2.1. To provide a single example here, Reference WattsWatts (2003: 27–28) used activity type to consider the conventional dynamics of incidents like the following one:

Imagine yourself standing in a queue at the booking office of a coach station. It is your turn next, but before you can even begin to order your ticket, someone pushes in front of you and asks the official behind the counter for a single ticket to Birmingham. Fortunately, this sort of thing is not a daily occurrence, but when it does happen, we are likely to feel somewhat annoyed. The least we could have expected is some kind of excuse on the part of the person for her/his action. … If we were asked to comment on the incident afterwards, we would probably suggest that the pusher-in had behaved impolitely, even rudely, to those in the queue. We might not consider his behaviour to have been rude towards the official, but we would have certainly expected the official to point out the ‘rules of the game’ and to refuse to serve her/him.

This fictional situation is recognisable as a public service encounter in which none of the participants is expected to know any of the others (although, of course, they may). As a social activity type it is subject to a so-called interaction order, i.e., the politic behaviour of waiting to be served in a queue involves the participant in certain types of behaviour which take place at certain sequentially ordered points in the interaction.

While such an analysis is certainly relevant from a ritual point of view, the ritual view would prompt one to also look at the scenario of standing in a queue at the booking office of a coach station from other angles than the impoliteness-relevant phenomenon of a breach of civility. For example, it would be noteworthy to study ritual conventions of waiting – including pragmatic phenomena such as Small Talk during the waiting time – as well as cases when seemingly ‘nothing is happening’ but people in the public scene nevertheless invisibly communicate with one another by pretending not to notice others, i.e., the phenomenon of ‘civil inattention’ (Reference GoffmanGoffman 1963).

2.3.2 Differences Between the Ritual and the Politeness Perspectives

Returning to Example 2.1, it can be argued that it is not particularly relevant for politeness research because it lacks individuality and ad hoc-ness as far as it is realised in a default way. A seeming solution to make this example politeness-relevant would be to argue that welcoming someone is a ‘polite speech act’, and an individual may make this utterance ‘more or less polite’ by playing on its style. However, such an argument would be false for two reasons: Firstly, rigorous research on speech acts, in particular Reference House, Blum-Kulka, House and KasperHouse (1989), pointed out very early on that there is no straightforward relationship between politeness and speech acts, i.e., illocutions such as Welcome, Request, Apologise and so on are only potentially (if at all) related to politeness. Secondly, if welcoming someone in a public event is meant to be realised in a strictly conventionalised manner – e.g., ‘great pleasure’ in Example 2.1 is a phrase we may hear even if the speaker does not feel such a great pleasure! – ultimately individual preferences for how the speech act in question should be realised are normally overruled by pragmatic conventions (see also Reference IdeIde’s 1989 above-mentioned study). In the case of Example 2.1, such conventions may prevent the individual from ‘tampering’ with the expected style of the speech act because normally an audience expects a public welcoming to have a positive tone.

The second-best option to keep Example 2.1 relevant for politeness research would be then to provide and examine plenty of contextual information behind the utterance, e.g., consider the identities of the speaker, the recipient and the broader ratified audience, the background and trajectory of the public welcoming, the location where the utterance takes place, etc. For such a discursive analysis, it would be a piece of cake if there was an anomaly in the welcoming – something which is however missing from Example 2.1 if it is uttered in a default way. Discursive politeness scholars such as Reference WattsWatts (2003), Reference MillsMills (2003) and many others (including the author of this book in his early career days) have been actually hunting for critical idiosyncratic incidents to interconnect utterances like Example 2.1 with the phenomena of politeness and impoliteness. While in many post-2010 studies this pursuit of extraordinary has somewhat lost its momentum (see an overview in Reference KádárTerkourafi & Kádár 2017), it is still not overreaching to argue that many politeness scholars continue to pursue interest in ‘interesting’ instances of language use. This is particularly valid for research on impoliteness where the nature of the data normally represents the realm of the extraordinary.

The study of interaction ritual offers a perspective which is different from that of linguistic politeness research in two major respects. First, the study of ritual requires the researcher to focus on the default and ‘regular’ aspect of language use, including instances where the participants simply follow ‘boring’ routines (Reference CoulmasCoulmas 1981), such as welcoming someone in a conventional way, as in Example 2.1. In other words, a ritual perspective involves a focus on the ordinary rather than the extraordinary. As Chapters 3 and 4 of this book will show, this perspective does not mean that ritual data itself is boring or even ordinary for some, or that the ritual pragmatician can afford ignoring cases when an idiosyncratic event disturbs the flow of a ritual and upsets the expectations of various participants. However, the ritual pragmatician is advised to interpret instances of extraordinary behaviour through the lens of ordinary: instead of seeing idiosyncrasies as some ‘extras’ to the conventionalised and often ritual aspect of interpersonal interaction in the manner of politeness scholars like Reference WattsWatts (2003), for the ritual pragmatician idiosyncrasies are meant to represent often predictable pragmatic breaches through which one can interpret the ritual phenomenon being breached.

Second, studying the default and ‘regular’ ritual realm of language use implies that the ritual pragmatician normally pursues a simultaneous interest in all three pillar-units of language use, i.e., expressions, speech acts and discourse (see Reference House and KádárHouse & Kádár 2021a). As stated above, politeness research prefers much background information to study utterances like Example 2.1. It also often struggles with bringing together expressions and speech acts with politeness and impoliteness (see e.g., Reference Brown and LevinsonBrown & Levinson 1987; Reference EelenEelen 2001; Reference WattsWatts 2003 and many other classics of the field). More precisely, while cognitive politeness researchers such as Reference Escandell-VidalEscandell-Vidal (1996) and Reference RuytenbeekRuytenbeek (2019) used forms to examine politeness, the mainstream of linguistic politeness research has been dominated by the very reasonable argument – propagated by Reference EelenEelen (2001), Reference WattsWatts (2003) and others – that it is difficult to pin down the relationship between form and politeness in a replicable way.13 This is not the case with interaction ritual research: due to the ritualist’s focus on the conventional ritual aspect of language use in ritual contexts, the study of interaction ritual does not background expressions and speech acts and foreground discourse because ritual always manifests itself in conventionalised and formalised ways. For the ritual pragmatician, it is also often important to consider what is evident from a minimal utterance itself, provided that an utterance provides relevant information as regards basic pragmatic variables, such as the role relationship between the interactants and the public or private nature of an interaction, such as in Example 2.1. This, of course, does not mean that the ritualist may not pursue a discourse-analytic interest: in the spirit of what was summarised in Figure 2.1, one should argue that certain instances of language use can only be understood as ritual if one first considers the ritual context that brings such instances of language use to life.

Since Goffman’s concept of interaction ritual involves both ceremonial and contact rituals, the pragmatic study of ‘ordinary’ (conventionalised) interaction not only involves examining ceremonial utterances, but practically any utterance and interaction where the interactants simply follow pragmatic expectations. Compare the following example with Example 2.1:

Example 2.2

A: Nice day, isn’t it? B: Yes. A: Hm, bus is a bit late this morning. B: Hm.

Example 2.2 features the speech act Remark (Reference Edmondson and HouseEdmondson & House 1981: 98). Here, the Remark realised by A occurs in a typically ritual Type of Talk, i.e., Small Talk, where the interactants are supposed to exchange words with social symbolic rather than referential meaning. While Example 2.2 does not take place in a public and ceremonial context, unlike Example 2.1, it equally follows a highly conventionalised ritual pragmatic pattern. This is why many language users in English-speaking linguacultures tend to be aware of the fact that ‘Nice day, isn’t it?’ is a typically phatic Remark, rather than a ‘meaningful’ informative utterance.

A formal aspect of language use such as a speech act Remark can, of course, become more relevant for politeness than ritual. Compare Example 2.3 with Example 2.2:

Example 2.3

A: I saw your wife with John at that new Italian restaurant last night. B: Really, there’s supposed to be a new Spanish restaurant opening up soon, isn’t there?

The speech act Remark here is very different from what we could see in Example 2.2: in this interaction B realises Remark as an attempt to switch an unpleasant topic back into ritual Small Talk. By so doing, he also indicates that A talks out of line. From a politeness point of view, this interaction is of definite interest because the Remark here strategically resolves a face-threatening situation.

While interactions like the one featured in Example 2.3 are no doubt important, they are far less routinous that the other interactions featured in this section. So, we can argue that a fundamental advantage of the ritual perspective in pragmatics is that ritual encompasses something much more regular than linguistic politeness or impoliteness: it includes any instance of conventionalised communally oriented interaction where individual pragmatic solutions are somehow backgrounded. The communal orientation of ritual language use may have broader pragmatic implications than what this technical term suggests – consider the following example:

Example 2.4

Juliane: Ach, Daniel, you are always late. Daniel: Well, J, I didn’t miss anything because you were sleeping in your armchair anyway. Juliane: Stupid idiot!!

This is a typically ritual interaction which took place between the author of this book and a dear friend and colleague of his. The author and his colleague work together online on a daily basis and they swear a lot, in order to decrease the stress of academic research. If anyone else overheard this interaction, not mentioning being subject to such an abuse, this third party might have felt offended. However, this had not been the case with the participants for whom swearing represented an in-group ritual with recurrent pragmatic features, which made swearing in their relationship ‘harmless’, in a similar way to many other instances of ritual swearing (see Labov’s previously mentioned Reference Labov and Labov1972 seminal study). Example 2.4 is of course not irrelevant for impoliteness and politeness research, but it represents a case where forms of language use associated with impoliteness do not fulfil any one-off interactional function. Rather, rudeness is locally and constantly reinterpreted here by the micro community of the interactants as a form of ritual endearment: both participants would have missed such ritual swearing and abuse in many interactional episodes during their daily work.14 Thus, in Example 2.4, individualised impolite language use is ultimately far less (if at all) important in comparison to the communal rapport building and face enhancing (see Reference Spencer-OateySpencer-Oatey 2000) ritual function of abuse.

Example 2.4 also points to a key aspect of the ritual perspective, which in my view distinguishes it from the politeness perspective, namely, that in the pragmatic study of rituals one often encounters and studies the ostensible aspect of language use. Ostension is a concept coined by semioticians,15 and in previous pragmatic research on ritual such as Reference KoutlakiKoutlaki (2020: 94) ostensible behaviour described the apparent conformity to customs and ‘the enactment of self’s and others’ status’ through behaviour which is potentially about something else than what meets the eye, as the word ‘ostensible’ suggests. For example, in the encounter above, both participants conformed to in-group ritual conventions of cursing as a form of endearment rather than offence, i.e., here we have an archetype of ritual ostensible behaviour in hand. As Chapters 3 and 6 of this book will show, when a ritual becomes interactionally complex, the participants often use ‘polite’ and ‘impolite’ behaviour not so much to be nice or rude to the other, but primarily to ritually display their own (pragmatic) competence either to the recipient or a broader audience. In other words, polite and impolite phenomena in such ritual settings are both self- and communally oriented (see Reference ChenChen 2001) and often ostensive.

2.3.3 The Ritual–Politeness Scale

Example 2.4 represents a specific case in that here ritual swearing is ‘disarmed’. In Chapter 3, a case study of trash talk will illustrate that ritual abuse can also become very offensive and as such meaningful and potentially sensitive to both the participants and the observers of the ritual. What brings together Example 2.4 with such instances of conflict is that in any ritually relevant interaction (and, I would argue, most of our daily interactions belong to this category) individual pragmatic solutions are backgrounded to the communal conventionalised and ritual form and role of interaction. Being backgrounded does not imply the complete absence of individuality in ritual: following the scalar view of Reference LeechLeech (1983), it is reasonable to argue that fully-fledged interaction ritual represents the conventionalised end and fully-fledged politeness and impoliteness the individual end of language use. It is reasonable to argue that so-called ‘polite rituals’ (manifestations of etiquette) are closer to the ritual than the politeness end of the above-outlined scale. It is also reasonable to argue that rituals which somehow ‘go amiss’ (see Chapter 3) are closer to the impoliteness and politeness end of this scale.

When discussing the communal orientation of ritual, it is also worth revisiting the argument that interaction ritual (just like politeness and impoliteness) is far from being a homogeneous phenomenon. In Reference KádárKádár (2013), I set up a pragmatic typology of interaction ritual, arguing that interactions like Example 2.4 represent in-group rituals, while cases like mediatised ritual trash-talk studied in Chapter 3 are social rituals. There are also lower-level ritual types,16 but putting these aside here, it is valid to argue that the more in-group a ritual is, the more elusive the border between ritual and politeness and impoliteness becomes. While in social ritual it is normally easy to discern if one or more of the participants start to use individual politeness and impoliteness solutions beyond the realm of conventionalised and communally oriented and endorsed language use, it can be difficult even for the participants of an in-group ritual to clearly discern exactly when someone ventures beyond the pragmatic boundaries of a ritual. Consider the following example:

Example 2.5

Juliane: When I die you should collaborate with stupid Ute (pseudonym). Daniel: [silence] Now, watch it Juliane, that was really offensive and stupidly morbid. Juliane: Ach, Daniel.

The interaction in Example 2.5 took place between the same interactants as Example 2.4. In one of their working sessions, while exchanging their usual ritual insults, the author’s friend made a morbid joke that the author of this book found genuinely offensive because (a) the mention of death and (b) the mention of Ute who is regarded by the participants as a hopeless academic, and he immediately gave voice to being offended. Here, perceived offense trespassed the invisible and rather indetermined boundaries of ritual teasing.

In summary, the ritual perspective provides insight into a vast array of pragmatic phenomena. This perspective also offers an alternative analytic attitude to pragmatic context and behaviour than the politeness perspective. In conventional politeness and impoliteness research it would be odd, to say the least, to talk about ‘polite and impolite contexts’ because the phenomena of politeness and impoliteness come into existence primarily through the hearer’s evaluations across interpersonal contexts (see Reference EelenEelen 2001). This correlates with the phenomenon that politeness and impoliteness in their fully-fledged sense (i.e., as an end of a ritual–politeness scale) are individualistic albeit often conventionalised phenomena. When it comes to interaction ritual, on the other hand, it is perfectly valid to talk about ‘standard situations’ (see Reference House, Blum-Kulka, House and KasperHouse 1989 above) where rights and obligations and the related ritual order of the interaction are clear to all participants, i.e., these situations provide ritual contexts (see also Figure 2.1).

2.4 The Key Pragmatic Features of Interaction Ritual

In what follows, I define the key pragmatic features of interaction ritual. These features will be referred to throughout this book.

From what has been argued in this chapter thus far, the following may transpire:

they also indicate the presence of such situations and the related rights and obligations of the participants (see the above-mentioned alternative analytic attitude to pragmatic context).

Furthermore, from the examples presented in this chapter it is evident that rituals

are pragmatically salient for the participants even if the participants themselves may not always be aware of this salience until an interactional breach occurs,

operate with conventionalised (recurrent) pragmatic features, and

are realised with ratified roles (e.g., a sense of ratification is due to welcome someone, as in Example 2.1).

These pragmatic characteristics become very visible whenever we look at utterance and speech act-level manifestations of interaction rituals, such as the ones studied in the previous Section 2.3. However, the same pragmatic features also recur in more complex and interactionally co-constructed rituals.

To prove this latter point, in the following I provide an excerpt from Reference Kádár and SzalaiKádár and Szalai (2020), where a colleague of mine and myself examined the ways in which members of a Roma community in Transylvania socialise young children within their community into the interactional practice of ritual cursing. In order to understand the importance of this socialisation process, it is important to consider that cursing in this community is often believed to have the power to cause real harm. Because of this, it is fundamental for young children to be able to distinguish between teasing – and the related ‘harmless’ use of cursing – and ‘real’ uses of cursing. In the following example, two older female members of the Roma community, Kati and Teri, engage in playful ritual cursing with a young girl Zsuzska:

Example 2.6

1. Kati Xal o beng adjeh, hi:::! May the Devil eat today, huh! 2. Teri Mula::h, mula:h, [ja:::j! ((pretends to be crying)) She has died, she has died, oy! 3. Zsuzska ((laughs)) [@@@= 4. Kati Mulah? Has she died? 5. Zsuzska ((partly crying, partly laughing)) =Na! No. 6. Teri Mulāh tji mami e Pitjōka:! Your grandmother Pitjóka died! 7. Kati … Ne még mondjad úgy, mindjárt sír! Do not tell it to her anymore, she is going to cry! 8. Zsuzska Na! No! 9. Kati ((to Zsuzska, consoling her)) Na:, śej, či mulah! No, girl, she has not died!

In lines 1 and 2, Kati and Teri playfully tease Zsuzska by ritually cursing her grandmother. In line 3, Zsuzska responds to the curses with laughter but also begins to cry, indicating that her laughter is more than a simple perception of humour. As the ritual exchange intensifies, Zsuzska appears to be confused as to whether the cursing is meant to be harmful or not. In line 4, Kati appears to notice this confusion: she asks Zsuzska whether Teri’s claim – made in an intentionally overexaggerated tone – that Zsuzska’s grandmother has died is true, to which Zsuzska answers ‘no’, in line 5. However, Teri’s next curse in line 6 forces Zsuzska to the brink of tears again, and in line 7 Kati intervenes to decrease the ‘pressure’ of the interactional ritual on the child, by requesting Teri to reduce the intensity of the cursing. She also consoles the child in line 9.

The ritual features outlined above are clearly visible in the interactionally co-constructed ritual Example 2.6 representing the unit of discourse. The rights and obligations and the related standardness of the situation are straightforward: without these, the socialisation process could not properly work, and the cursing would become abusive. Also, considering that ritual here aims to help the child to acquire skill in cursing, the interaction clearly operates with a recurrent pragmatic inventory and very clear ratified roles, as witnessed by the intervention of the adult Kati in line 7. The interactional salience of the ritual is clear if one considers the emotively loaded responses of the child.

Along with the above-outlined basic pragmatic features, Example 2.6 also points to various more complex features of ritual:

Most importantly, the presence of a ritual frame (see also Reference Kádár and HouseKádár & House 2020a) and a related moral order of things, and the related operation and presence of

Part II of this book will introduce various of these pragmatic properties of ritual in greater detail, so here I only outline them briefly. Note that not all interaction rituals clearly necessarily operate with all four features listed with bullet points above. For example, it is difficult to use concepts such as ritual (self-)display for the utterance-level study of rituals (see Section 2.3). In other words, the more one focuses on the pragmatic unit of discourse in the study of interaction ritual, the more important these distinctive features become.

As the present section will show, the concept of ritual frame is by far the most important among the various features of ritual, and in the rest of this section I devote special attention to this notion.

2.4.1 Ritual Frame: An All-encompassing Concept

The concept of ‘ritual frame’ needs to be discussed separately from the other features of interaction ritual listed above because it is an all-encompassing characteristic which is responsible for the existence of practically all pragmatic features of ritual. Furthermore, ritual frame is a precondition for ritual to occur: it brings the ritual to life and it comes into operation whenever a particular interactional ritual unfolds. As the renowned anthropologist Victor Reference TurnerTurner (1979: 468) argued in his ground-breaking study:

To look at itself, a society must cut out a piece of itself for inspection. To do this it must set up a frame within which images and symbols of what has been sectioned off can be scrutinized, assessed, and, if need be, remodelled and rearranged.

Turner described ritual frame as a physical space: there is a separated area in many tribes for a ritual to take place, and once one enters this area, specific behavioural rules apply and rights and obligations are clearly defined. As Reference GoffmanGoffman (1974) pointed out, in modern urbanised societies we may have fewer such spaces, and the indication of ritual frames often takes place vis-à-vis ritual language use, indicating awareness of a virtual ritual frame in standard situations (Reference House, Blum-Kulka, House and KasperHouse 1989). Ritual frame implies the presence of an interactional moral order (see Reference WuthnowWuthnow 1987 and Reference DouglasDouglas 1999), i.e., an expected order of things according to which the ritual interaction should unfold (see above; see also a detailed discussion of ritual and moral order in Reference KádárKádár 2017).

Let us now discuss the phenomena of mimesis, (self-)display, escalation (for rites of aggression) and liminality outlined above. In a ritual frame, the participants’ behaviour is not only meant to follow pragmatic conventions, but also they often mimetically re-enact the interaction ritual. As Chapter 5 will show, mimesis not only involves simple reciprocation (see Reference EdmondsonEdmondson 1981) which is present in many daily rituals (such as mutual greeting), but rather talking in an ‘alien’ voice, by taking up assumed roles in the interaction, just like actors on the stage (rather than engaging in ‘crossing’, see above). Mimesis is particularly visible in Example 2.6 where the adult participants prompt the child to mimetically engage in cursing as part of the language socialisation process.

The interaction ritual featured in Example 2.6 also has a sense of ‘lavish and ornate’ display as Reference Bax, Culpeper and KádárBax (2010: 58) puts it: the participants curse practically all the time during the interaction because the ritual frame allows and even prompts them to do this. In other words, they put cursing on display as part of the ritual, and they also engage in a self-display in the sense that they as adults showcase their own skill in realising this ritual phenomenon.

Along with this sense of ‘overexaggeration’, the ritual frame here also triggers a sense of escalation – a phenomenon which characterises rites of aggression only (see Chapter 3). That is, the longer the ritual lasts, the more intensive it becomes.

Finally, the interaction ritual brings the participants into an altered – i.e., liminal – state of mind and status, also in terms of language use. That is, they pass a certain sense of threshold, by leaving behind the boundaries of their ordinary pragmatic constraints and related rights and obligations.

As this brief analysis of Example 2.6 illustrates, the different features of interaction ritual are in an intrinsic relationship: once a ritual frame prompts them to emerge, they tend to emerge in combination. Accordingly, while in Part II of this book I will highlight each of them in different case studies, such an emphasis does not mean that any of these ritual features are somehow ‘stand-alone’. Also, what always needs to be remembered is that all these features are ‘products’ of the ritual frame that underlies any interaction ritual, and which very often also imposes constraints on these pragmatic features. For instance, in Example 2.6 the ritual frame implies that mimetic liminal aggressive (self-)display in ritual needs to be kept within conventional pragmatic boundaries, even though the interaction leads to an escalation where the socialised person bursts out into tears.

2.4.2 Ritual Frame Underlying Methodological Approaches to Ritual

The concept of ritual frame is so important in the study of interaction ritual that it always influences methodological approaches through which the pragmatician can capture ritual (see a more detailed discussion in Part III). Let us here present Figure 2.1 again, in a revised form:

As Figure 2.2 shows, there are two ways in which pragmatics-anchored ritual research may operate. Firstly, the researcher may focus on a pragmatic unit of analysis – expressions, speech acts and routinised or scripted parts of discourse – as a departure point of analysis, hence associating a form of language use with ritual. As Section 2.3 of this chapter has shown, forms of language use like expressions and speech acts tend to gain a ritual function in an actual interaction ritual frame: one can only study their ritual function in a rigorous and replicable way if one considers their conventional use(s) in the interaction ritual frame of specific contexts. The arrow in Figure 2.2 therefore shows that forms of language use which one associates with ritual can only be reliably studied if their use is considered through the concept of ritual frame. Even expressions and speech acts which are very closely associated with ritual in the popular sense, as well as scripts of ceremonies may be no exception to this. One may argue that archetypal formal manifestations of ritual, such as ‘Amen’, are ritual (see more in Chapter 8). However, even in the study of such expressions, and realisations of ‘ritual’ speech acts such as Greet, and scripts like prayers, one needs to consider their situated use in various data if one wants to tease out exactly how they are used in interaction, exactly when they gain a ritual function, and how they evolve over time. In other words, in the study of ritual as a form one may need to consider exactly when and how a particular form associated with ritual becomes ritual.

Figure 2.2 The role of ritual frame in research on interaction ritual.

Secondly, if one approaches ritual as a pragmatically abstract phenomenon, one unavoidably needs to break it down to replicable pragmatic units. While ‘rite of passage’, for example, is certainly a ritual from the anthropologist point of view, for the ritual pragmatician it only represents an event and a context, which imposes certain preset rights and obligations on the participants and observers in the form of a conventionalised ritual frame. The pragmatician in turn examines exactly how the frame of such a ritual influences language use.

2.4.3 Ritual Frame Influencing the Pragmatic Typologisation of Ritual

The concept of ritual frame also helps us to consider how interaction rituals can be captured through a typology, which approaches ritual according to the types of behaviour the ritual frame prompts to emerge. While I will outline such typological considerations in more detail in the following Chapters 3 and 4, let us outline its basics at this point. While all interaction rituals help social structures to reinforce or reformulate themselves, this reinforcement or reformulation can take place in two entirely different ways: either through ‘orderly’ or seemingly ‘disorderly’ ritual events. Following Reference TurnerTurner’s (1979) seminal thought, I will refer to the former orderly event types as rites taking place in ‘structure’ – i.e., the normal society – and the latter disorderly event types as rites taking place in ‘anti-structure’, i.e., a social grouping (or ‘communitas’) which is allowed to temporarily violate the ritual behavioural boundaries of ordinary social life. However, somewhat differently from Turner who pursued interest in societies and cultures rather than language use, I will distinguish conventionalised language use taking place in structure and anti-structure as ‘rites of structure and anti-structure’. Importantly, both these ritual types operate with a well-defined ritual frame and an underlying moral order, i.e., structure and anti-structure represent a typology of ritual frames. An advantage of this simple typology is that it is finite and centres on the (dis)orderly nature of rituals, and as such it is more advantageous from the pragmatician’s point of view than categorising rituals according to their context of occurrence.

2.5 Conclusion

The present chapter has provided a departure point for what is to be discussed in the rest of this book, by positioning interaction ritual and defining its key pragmatic features. The chapter first presented a brief review of previous pragmatic research on ritual, and also explained why Goffman’s notion of interaction ritual is particularly useful for the pragmatician. As a next step, I discussed why a ritual perspective on language use is at least as (if not more) relevant for the study of ordinary language use than the politeness perspective. Following this, I provided an overview of the key pragmatic features of interaction ritual, including both those features which can be described through ‘standard’ pragmatic technical terms such as conventionalisation, and others which are not parts of the standard terminology of pragmatics and interaction studies, such as liminality. I argued that the concept of ritual frame is an all-encompassing notion, which always needs to be considered in the pragmatic study of ritual.

In the following Chapter 3, we will continue the journey started in this chapter, by taking a closer look at interactional rites of aggression and the question as to why the ritual perspective provides a fundamental tool to understand such rituals.