3.1 Introduction

The Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) (the Post-2020 Framework) is expected to embody transformative change through the adoption of the framework’s “Theory of Change” (CBD, 2020). Its implementation must recognize that the global biodiversity governance architecture needs to transform to lead the required personal and social transformations, including shifts in values, beliefs and patterns of social behaviors (Reference Chaffin, Garmestani and GundersonChaffin et al., 2016), necessary to successfully tackle biodiversity loss. Against this backdrop, the overarching goal of this chapter is to analyze what needs to be transformed in global biodiversity governance, including institutional structures that shape values, beliefs and behavioral change. The chapter examines obstacles and opportunities for transformation, with the indirect objective of informing implementation of the Post-2020 Framework; at the time of writing, the CBD is expected to adopt the Post-2020 GBF in 2022.

The chapter firstly introduces the key global biodiversity treaty, the 1992 UN Convention on Biological Diversity, and its principal institutional body, the Conference of the Parties (COP) (Section 3.2). The evolution of the CBD is analyzed along with its procedural mechanisms, including its decision-making and review mechanisms. Secondly, the chapter presents the other relevant international institutions in what constitutes the “regime complex” for global biodiversity governance (Section 3.3). Within this complex, biodiversity governance takes place at multiple levels, from global to local, and in different sectors, including some of those most responsible for biodiversity loss such as agriculture, trade and development. The evolution of biodiversity governance beyond the CBD is also explored by analyzing the role of private actors, including business and civil society, in global biodiversity governance. Thirdly, the implementation of global biodiversity laws and policies is examined through global and national governance processes (Section 3.4). The final section draws upon the analyses to propose ways to transform and strengthen global biodiversity governance (Section 3.5), before concluding. The chapter is mainly based on legal analyses, while also drawing on more generic biodiversity governance literature.

3.2 The Convention on Biological Diversity

3.2.1 The CBD, from Seed to Sapling

The CBD opened for signatures at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, known as the Earth Summit, in Rio in 1992, marking the start of the “postmodern era” of environmental regulation (Reference Sands, Bodansky, Brunnée and HeySands, 2007). The Convention, having now near universal ratification (with the major exception of the United States), marked a paradigm shift, from earlier species-specific and ecosystem-based nature conservation conventions to a holistic and development-oriented approach to biodiversity. The CBD is a framework convention that sets out basic principles, general objectives, and rather broad and qualified provisions. The three objectives are biodiversity conservation, sustainable use, and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits. Legal polycentricity, intergenerational responsibilities, and the need for inclusive and participatory processes were new concepts recognized by the treaty (Reference Sands, Bodansky, Brunnée and HeySands, 2007).

In addition, three legally binding protocols have been agreed to date under the CBD Art 28 mechanism: the 2000 Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety, the 2010 Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the 2010 Kuala Lumpur Supplementary Protocol on Liability and Redress (Supplementary to the Cartagena Protocol). While these protocols cover the second and third objective of the CBD respectively, it is remarkable that no protocol has been agreed relating to the first objective of the CBD, biodiversity conservation. Thus, the first objective has been addressed by the COP only through its non-legally binding instruments like strategic plans, visions, goals and targets, decisions, guidelines and recommendations.

The design of CBD targets has improved since the first broad “2010” biodiversity target, which called state parties “to achieve a significant reduction of the current rate of biodiversity loss at the global, regional and national level by 2010 as a contribution to poverty alleviation and to the benefit of all life on earth” (CBD COP6, 2002). This target was unmet and superseded by the 2020 strategic plan and the twenty Aichi Targets (ATs), agreed at CBD COP10 in 2010 (see Chapter 1). The ATs were designed to be SMART (specific, measurable, ambitious, realistic and time-bound) and to improve the initial 2010 target (Reference Harrop and PritchardHarrop and Pritchard, 2011). However, well before the 2020 deadline it was clear that most of the ATs would not be achieved (IPBES, 2019; SCBD, 2020).

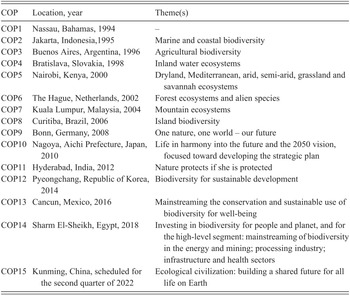

3.2.2 An Active Body: The CBD COP

The CBD COP is the governing body of the CBD, where state parties make decisions by consensus to advance implementation of the Convention. It is in a unique position to strengthen global biodiversity governance to steer change. The COP can advance the evolution and implementation of the CBD by (i) agreeing and furthering ambitions through decisions that are soft law but guide parties, and (ii) creating a space to positively encourage and promote implementation of obligations. It creates a space for the development of shared understandings of the legal regulation of biodiversity, and norms through the elaboration of guidelines on various topics. The thematic priorities of COPs (see Table 3.1) have changed from predominantly ecosystem-based themes (COP1–COP9) to addressing the main drivers of biodiversity loss (COP10–COP14). Themes of earlier COPs do not necessarily tally with their focus or substantial outcomes. For example, COP7’s theme was “Mountain Ecosystems” and, while a work program on this theme was adopted, more notably a work program on protected areas and the Addis Ababa principles on sustainable use were also adopted, which received more attention and subsequently are seen as more important. Changing narratives indicate the broadening of agendas of the CBD and the themes of more recent COPs better match their outcomes.Footnote 1 COP15 follows this trend and hooks onto an important concept: “Ecological Civilization: Building a Shared Future for All Life on Earth.”

Table 3.1 CBD COP themes

Due to the broad scope and comprehensive character of the CBD COP, it is essential that there is buy-in from a very wide range of actors. The Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG) responsible for developing the Post-2020 Framework utilizes a theory of change approach to guide the development of a nature framework for all, not just for signatories from the Ministry of Environment, but for the whole of government, multilateral institutions, Indigenous People and local communities (IPLC), nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and business. This could be challenging. A study of the 2016 CBD COP13 in Cancun, Mexico, found a poor representation of government ministers from the economic sectors from both the global north and south, indicating the limited buy-in of biodiversity negotiations nationally, and that disadvantaged actors from the global south were unable to participate as effectively in negotiations due to the limited size of their delegations and lack of expertise to cover all agenda items (Reference SmallwoodSmallwood, 2019). This unbalanced dimension creates power dynamics that are problematic in consensus decision-making and in creating obligations that rest on genuine shared understandings: not all relevant actors are present and exposed to the processes of influence and persuasion at COP meetings (Reference BrunnéeBrunnée, 2002; Reference SmallwoodSmallwood, 2019).

The CBD COP has a long history of engagement with stakeholders such as women, children and youth, NGOs, local authorities, trade unions, business and industry, science and technology, and farmers as observers to its meetings. IPLC have a well-established engagement and influence that is unique for the CBD compared to other intergovernmental processes (Reference ParksParks, 2018). Such nongovernmental actors are central actors in international environmental regimes including the CBD (Reference Spiro, Bodansky, Brunnée and HeySpiro, 2007), exerting influence through: domestic political processes such as rallying voters, lobbying law makers, disseminating information, bringing legal actions and working with media and academia (Reference Chayes and ChayesChayes and Chayes, 1995); advancement of domestic NGO agendas in the international sphere (Reference Spiro, Bodansky, Brunnée and HeySpiro, 2007); and agenda-setting (Reference Arts, Mack and FalknerArts and Mack, 2006). Nongovernmental actors also take on certain key functions within international negotiations, including supplying policy research and development to states (for instance, the 5th Global Biodiversity Outlook is a product of “collected efforts” including individuals from nongovernmental organizations and scientific networks), supplying information on compliance,Footnote 2 facilitating negotiationsFootnote 3 and participating in national delegations (Reference SmallwoodSmallwood, 2019).

A specificity of the CBD COP has also been its ambition to include businesses in its activities. A 2006 COP decision on business participation defines a “business and biodiversity” agenda.Footnote 4 Subsequent COP decisions aim to facilitate private sector engagement and encourage businesses to “adopt practices and strategies that contribute to achieving the goals and objectives of the Convention and the Aichi Targets” (COP12 Decision XII/10). A Global Partnership for Business and Biodiversity and a Business and Biodiversity Forum have been established, and the 2017 Business and Biodiversity Pledge has 141 signatories, including some large corporations such as Monsanto, L’Oréal and DeBeers; however, most relevant multinational corporations to biodiversity loss are not signatories. Despite these decisions and initiatives on business, to date the level of business involvement has been less than aimed for by the CBD COP (Reference van Oorschot, van Tulder and Kokvan Oorschot et al., 2020).

The CBD stresses the importance of “mainstreaming,” that is, the inclusion of biodiversity considerations into nonenvironmental policy areas that impact or rely on biodiversity (Reference YoungYoung, 2011). Art 6(b) of the CBD requires Parties to integrate the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity into sectoral and cross-sectoral activities. Subsequently, means of furthering mainstreaming have been an endeavor of the CBD COP. The first goal of the 2011–2020 CBD strategic plan, agreed at COP10, was to address the underlying causes of biodiversity loss by mainstreaming biodiversity across production sectors and society (GEF, 2016; GEF et al., 2007; SCBD, 2020).Footnote 5 In addition, COP decisions on mainstreaming have been agreed, and mainstreaming was adopted as the key theme at COP13 and COP14. So far, mainstreaming is mostly considered an issue of policy coherence that is yet to be realized at global and national levels, let alone making significant links with communities such as business to realize the whole of society approach advocated by the CBD.

The CBD has two permanent subsidiary bodies: First, Art 25 of the Convention established an open-ended intergovernmental scientific advisory board, the Subsidiary Body on Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice (SBSTTA). The SBSTTA provides advice and makes recommendations to the COP and has met twenty-four times from 1995 to 2020. Second, COP12 established a Subsidiary Body for Implementation (SBI) in 2014, whose mandate includes strengthening mechanisms to support implementation of the Convention and any strategic plans adopted under it, and identifying and developing recommendations to overcome obstacles encountered. Due to the soft law nature of most CBD decisions, the CBD has adopted a facilitative approach toward implementation by monitoring national implementation through national reporting (Art 26). Besides, a system of voluntary peer review of National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs) and their implementation is under development. The methodology was tested in two countries (Ethiopia and India), and later three countries have been reviewed in a pilot phase (Montenegro, Sri Lanka, Uganda) (CBD, 2020).

3.3 The Biodiversity Regime Complex

3.3.1 The Intergovernmental Components of the Regime Complex

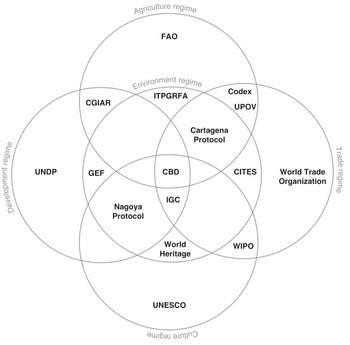

Intergovernmental biodiversity governance has also evolved beyond the CBD. Indeed, due to its comprehensive scope, the CBD has gradually become the central element of a biodiversity regime complex, consisting of five pre-existing international regimes that progressively became regime complexes as well (see Figure 3.1, based on Reference Morin and OrsiniMorin and Orsini, 2014).

Figure 3.1 The regime complex on biodiversity (with a selection of international institutions provided as illustrations of the constituent elements)

CBD: Convention on Biological Diversity

CGIAR: Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research

CITES: Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora

FAO: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

GEF: Global Environment Facility

IGC: WIPO Intergovernmental Committee on Intellectual Property and Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and Folklore

ITPGRFA: International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture

UNDP: United Nations Development Programme

UNESCO: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

UPOV: International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants

WIPO: Word Intellectual Property Organization

The first is the environmental regime. The first objective of the CBD, biodiversity conservation, facilitated interactions between the CBD and a pre-existing cluster of multilateral agreements within the environmental regime. Some of these agreements are biodiversity-related conventions such as the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, the Convention on Migratory species (CMS) and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). In 2007, these conventions started to collaborate in the framework of a broader Liaison Group of the Biodiversity-Related Conventions. The environmental conservation regime also consists of treaties that are not exclusively biodiversity-related, such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) (also adopted at the Rio Summit). A Joint Liaison Group of the Rio conventions has been established to enhance coordination and explore options for cooperation and synergistic action.Footnote 6

The second is the agricultural regime. The interactions here are established on a dual basis: agriculture practices are one of the main drivers for biodiversity loss, but agricultural biodiversity is also under threat, and constitutes the basis of food security (IPBES, 2019, see also Chapter 13). How best to manage agricultural biodiversity raises several questions, as agricultural genetic resources are not only important components of biodiversity but also constitute essential food resources (Reference SpannSpann, 2017). In addition, the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety to the CBD also interacts with the agricultural regime by developing rules concerning the use, especially in agriculture, of genetically modified organisms. The CBD has always considered the agricultural sector to be a priority for mainstreaming.

The third is that of trade. Natural resources, like any other type of good, are traded; and biodiversity is subject to innovation protection, through instruments of intellectual property rights such as patents under the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) of the World Trade Organization (Reference Raustiala and VictorRaustiala and Victor, 2004). To counter TRIPS, the CBD stated the principle of state sovereignty over natural resources, which allows states to regulate access to biodiversity within their borders.

The fourth regime is the international development regime. Sustainable development was at the heart of the priorities of the 1992 Rio Summit, which adopted the CBD (Reference Ademola, Casey and BridgewaterAdemola et al., 2015). The development regime includes, among others, financial provisions through, for instance, the Global Environment Facility, to assist developing countries to achieve the objectives of the CBD.

The fifth is that of culture. Originally, the main focus of this regime was on cultural heritage through the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Convention (WHC). The WHC is part of the Liaison Group of the Biodiversity-Related Conventions and is increasingly connected with biocultural diversity, alongside other international policies such as the Nagoya Protocol to the CBD, which recognizes the importance of the traditional knowledge associated with genetic resources (Reference Morgera, Tsioumani and BuckMorgera et al., 2014), and the positive role of IPLC in conservation and the biocultural values that they represent (IPBES, 2019).

The existence of a regime complex is both a strength and a weakness for the CBD (“be at the table or be on the menu”). On the one hand, it ensures biodiversity is “at the table” and the various elements of the regime complex give resonance and amplify the biodiversity issue with its multiple dimensions and values (see Chapter 2). On the other hand, it is a weakness and can be seen to be “on the menu” with more powerful components of the regime deciding the fate of biodiversity. Lack of integrative governance between the different intergovernmental components of the complex, and tensions between biodiversity and the trade, agriculture and development dimensions has led to insufficient attention to biodiversity, as evidenced by poor progress on mainstreaming, and missed biodiversity targets. Policy coherence for biodiversity at the global level is an important precondition for “whole of government” approaches for biodiversity, as is being discussed in the Post-2020 Framework.

3.3.2 Governance beyond the Intergovernmental Realm

Since the 1980s, the institutional landscape of global biodiversity governance has shifted from predominantly public to more private and hybrid (public–private) forms of governance involving private actors (Reference Kok, Widerberg, Negacz, Bliss and PattbergKok et al., 2019; Reference Negacz, Widerberg, Kok and PattbergNegacz et al., 2020). The regime complex has expanded and includes new nonstate dimensions that work across state borders; this is referred to as transnational environmental governance (Reference Bulkeley and JordanBulkeley and Jordan, 2012). Neoliberalism has steered the privatization of state functions and promoted the commodification of biodiversity within global markets, thus shifting power relations (Reference Büscher, Sian, Neves, Igoe and BrockingtonBϋscher et al., 2012). For example, in agricultural commodity chains, public, private and, to a lesser extent, not-for-profit organizations play roles in global environmental governance, extending governance beyond legal and policy regimes.

The broader trend toward increased transnational governance can be seen in biodiversity policy as well as other areas, such as climate change and sustainable development (Reference Bansard, Pattberg and WiderbergBansard et al., 2017; Reference Bulkeley and NewellBulkeley & Newell, 2015; Reference Jordan, Huitema and HildénJordan et al., 2015; Reference PattbergPattberg, 2010; Reference Pattberg, Widerberg and KokPattberg et al., 2019; Reference van Oorschot, van Tulder and Kokvan Oorschot et al., 2020; Reference Visseren‐HamakersVisseren-Hamakers, 2013). An increasing number of nonstate and subnational actors (e.g., cities, regions, business and finance) participate in a plethora of national and international cooperative initiatives with the aim of addressing biodiversity loss (Reference Pattberg, Widerberg and KokPattberg et al., 2019; Reference Visseren‐HamakersVisseren‐Hamakers, 2013).

The increasing importance of nonstate and subnational actors, as well as their formal involvement, poses challenges to a state-based UN process like the CBD and the Post-2020 Framework and its further implementation. Collaboration with transnational actors entered a new stage in 2018 when, at COP14, COP presidencies Egypt and China, with the CBD Secretariat, launched the “Sharm El-Sheikh to Kunming Action Agenda for Nature and People” (Reference Kok, Widerberg, Negacz, Bliss and PattbergKok et al., 2019; Reference Pattberg, Widerberg and KokPattberg et al., 2019). The action agenda’s aim is to raise public awareness about the urgent need to stem biodiversity loss and restore biodiversity for both nature and people; to inspire and implement nature-based solutions to meet key global challenges; and to catalyze nonstate and subnational initiatives in support of global biodiversity goals. The action agenda is hosted on an online platform that has received and showcased commitments and contributions to biodiversity from stakeholders across all sectors in advance of COP15. This platform enables the mapping of global biodiversity efforts and helps to identify key gaps and estimate impact. With such a platform, the CBD follows current governance trends “towards transnational environmental governance and the inclusion of non-state action in multilateral agreements” (Reference Pattberg, Widerberg and KokPattberg et al., 2019: 385). Increasing inclusivity is considered an important element of transformative biodiversity governance (see Chapter 1); this is an important development in contributing to the mainstreaming of biodiversity where it matters as part of integrative governance (Reference Bulkeley, Kok and van DijkBulkeley et al., 2020; Reference Karlsson-Vinkhuyzena, Kok, Visseren-Hamakers and TermeeraKarlsson-Vinkhuyzena et al., 2017), and is being framed as a “whole of society approach” in the Post-2020 Framework.

Within the category of nonstate actors, the important role of subnational actors, cities, regions and local authorities has been recognized in the CBD since 2010. The “Edinburgh process” allows the active participation of subnational actors in consultations, therefore shaping the Post-2020 Framework and targets. With the global growth of urban populations, Reference Puppim de Oliveira, Balaban and DollPuppim de Oliveira et al. (2011) argue that, even though cities are not directly involved in negotiating environmental agreements, they can play a major role in implementation and influence biodiversity conservation (Reference Bulkeley, Andonova and BäckstrandBulkeley et al., 2012). Increasingly, large urban and regional initiatives, such as the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives, or Covenant of Mayors, actively engage in diverse biodiversity activities and policies (see Chapter 14).

The involvement of business and the financial sector in the CBD is more contested. The first COP decision to encourage stronger business involvement was made in 1996 at COP3, but it took until 2010 for a CBD Business and Biodiversity platform to be established. Businesses within primary sectors, which exert direct pressure on biodiversity but also highly depend on it, have started to develop more biodiversity-friendly production methods, see opportunities in developing nature-based solutions and contribute to various sustainability and corporate social responsibility (CSR) goals, although pressure on biodiversity continues to grow (SCBD, 2020). Furthermore, international networks for business and biodiversity are starting to emerge: In 2019, the Business for Nature network was created with the aim of encouraging the adoption of a post-2020 biodiversity transformative agenda.

This diverse and polycentric institutional landscape of global biodiversity governance, described by Reference Pattberg, Kristensen and WiderbergPattberg et al. (2017; Reference Pattberg, Widerberg and Kok2019), is rapidly expanding. Reference Negacz, Widerberg, Kok and PattbergNegacz et al. (2020) and Reference Curet and PuydarrieuxCuret and Puydarrieux (2020) identified 331 international collaborative initiatives forming a crowded and diverse governance landscape, with international collaborative initiatives transitioning from predominantly public to more hybrid forms, including state, market and civil society actors, performing a broad array of governance functions. Most initiatives focus on information sharing and networking, followed by on-the-ground activities, setting standards and certification. Their activities mostly focus on sustainable use and conservation efforts for sectors such as agriculture, forestry and fisheries, rather than solely conservation. The geographical coverage of the initiatives suggests a wide but uneven distribution of activities. The efforts of the initiatives focus on Europe and Africa, leaving areas of high biodiversity in Asia and Latin America with much less attention (Reference Negacz, Widerberg, Kok and PattbergNegacz et al., 2020). Most initiatives monitor their performance, and more than half report their progress annually. Yet, only one-fourth of them has a verification mechanism in place, making review of progress more challenging (Reference Negacz, Widerberg, Kok and PattbergNegacz et al., 2020).

These more inclusive forms of biodiversity governance that commit to action for biodiversity, by a broad coalition of nonstate and subnational actors, could facilitate transformative change for biodiversity by breaking gridlocks in current negotiations through: fostering a nature-inclusive agricultural transition; pushing governments to increase their ambition levels to create a level playing field for front runners; building new multistakeholder coalitions and finding innovative solutions to existing problems (Reference Hale, Held and YoungHale et al., 2013; Reference Pattberg, Widerberg and KokPattberg et al., 2019). Yet, business engagement also raises serious concerns with business taking a powerful role in reshaping the biodiversity regime to its own profit-making agendas (Reference Büscher, Sian, Neves, Igoe and BrockingtonBüscher et al., 2012; Reference Corson and MacDonaldCorson and MacDonald, 2012; Reference MacDonaldMacDonald, 2010; Reference SpannSpann, 2017). Therefore, to avoid greenwashing, it is important to monitor and review progress. However, tracking the impact of international cooperative initiatives on the ground remains a challenge (Reference Arts, Buijs and GeversArts et al., 2017), and the impact, accountability, legitimacy and transparency of transnational biodiversity initiatives require more research (Reference GuptaGupta, 2008; Reference Jones and SolomonJones and Solomon, 2013).

3.4 Implementing Biodiversity Law and Policy

3.4.1 NBSAPs: Strengths and Limitations

National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans provide the foundation for national implementation of the CBD. In fact, their provision in the CBD, Article 6(a), is one of only two provisions that are unqualified and binding on Parties to the CBD whatever the circumstances; the other is Article 26 on national reporting. Its twin provision, Article 6(b), requires state parties to integrate the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity into sectoral and cross-sectoral activities, signaling that such mainstreaming should be a key element of NBSAPs.

An upgrade of the role of NBSAPs was made in 2010 by the inclusion of AT 17, stating that “By 2015, each Party has developed, adopted as a policy instrument, and has commenced implementing, an effective, participatory and updated national biodiversity strategy and action plan.”

In early 2021, 191 out of 196 CBD state parties (97%) have developed at least one NBSAP, among which 169 have been developed after the adoption of the ATs. NBSAP processes have led to a better understanding of biodiversity, its value and what is required to address its threats. However, for many first-generation NBSAPs (developed before the ATs), development processes were more technical than political and did not manage to sufficiently influence policy beyond the remit of the Ministry of Environment (or whichever ministry is directly responsible for biodiversity) (Reference Prip, Gross, Johnston and VierrosPrip et al., 2010).

Second-generation NBSAPs were therefore proposed for the post-2010 period. These include national targets to a larger extent and offer an opportunity for a diversity of actors to engage with biodiversity policies and connect relevant decision-makers within a country (Reference Ademola, Casey and BridgewaterAdemola et al., 2015). However, the potential to “make NBSAPs matter” (Reference Ademola, Casey and BridgewaterAdemola et al, 2015: 105) is challenged using national targets more oriented toward classic nature conservation than systemically oriented to address the underlying causes of biodiversity loss through mainstreaming. Such goals and targets are often expressed in general, aspirational terms, without specifications as to how they could be operationalized. Many countries seem to be at a preliminary stage in terms of mainstreaming because a necessary first step is a basic review of all policies and legislation relevant to biodiversity (Reference Prip and PisupatiPrip and Pisupati, 2018). Moreover, many first-generation NBSAPs have not been endorsed beyond the ministry directly responsible for the CBD, indicating that mainstreaming goals and targets has not always been fully coordinated at the political level. Some NBSAPs specify that this remains to be done (Reference Prip and PisupatiPrip and Pisupati, 2018).

While the post-2010 NBSAPs reveal that biodiversity mainstreaming is gaining recognition, the process is at a very early stage and a considerable amount of political and legal work still needs to be done before tangible results can be achieved on the ground. Considering the missed Aichi Targets, this work needs to be prioritized to address the biodiversity crisis in time.

3.4.2 The Implementation Gap

Effective implementation has long been a challenge for the CBD (Reference Butchart, Di Marco and WatsonButchart et al., 2016). Theorists offer different explanations for poor implementation and lack of compliance, and these can be explored in the context of the CBD. International relations rationalists see power dynamics and self-interest as motivations for states to act (Reference Goldsmith and PosnerGoldsmith and Posner, 2005). Enforcement theorists indicate that compliance may require considerable resources in time, political engagement and financing; therefore, sanctions and other enforcement mechanisms are required to incentivize states to comply (Reference KoskenniemiKoskenniemi, 2011). Managerial schools understand that states will generally comply with international law because: (i) it is consent-based and therefore generally serves their interests, (ii) it is an effective cooperative problem-solving method saving costs and (iii) there is a general norm of compliance among states. Subsequently, noncompliance can be explained by ambiguity in international law and capacity limitations (Reference Chayes and ChayesChayes and Chayes, 1993).

Positivist lawyers argue that the lack of hard law provisions in the CBD is a key factor for explaining why there are large gaps in implementation and state parties are not sufficiently achieving the CBD objectives, targets and goals (Reference Harrop and PritchardHarrop and Pritchard, 2011). As a treaty, the CBD is a hard law instrument and contains “hard” obligations, such as Art 6 relating to NBSAPs and Art 26 relating to national reporting. Otherwise, the CBD has largely developed through “soft” or qualified legal obligations, and the treaty itself uses vague and noncommittal language, such as “as appropriate,” “as far as possible” and “subject to other existing international/national legislation,” which essentially renders these provisions “soft” (Reference Harrop and PritchardHarrop and Pritchard, 2011: 477). Decisions, including strategic plans and targets, of the CBD COP are “soft” obligations. Significant gaps in national implementation suggest the design of targets is problematic due to their ambiguity, lack of quantifiability, complexity and redundancy (Reference Butchart, Di Marco and WatsonButchart et al., 2016), and therefore they lack institutional fit at the national level (Reference Hagerman and PelaiHagerman and Pelai, 2016).

However, states can take nonbinding or “soft” international environmental legal obligations seriously.Footnote 7 If soft law can guide or influence behavior (Reference BodanskyBodansky, 2016), then different explanations for what makes law effective must be considered. Interactive law blends law with constructivist understandings (Reference Brunnée and ToopeBrunnée and Toope, 2010), and is relevant to understanding the CBD with its plethora of soft law provisions. It recognizes that law (hard or soft) can draw compliance: (i) through the fulfillment of certain internal criteria of legality; (ii) when it is based on genuine shared understandings formed by broad participation of all relevant actors in legal decision-making fora and (iii) when a practice of legality is established that reenforces and revisits the legal obligation. When applied to the CBD ATs, new explanations for implementation gaps arise:

Clarity: Many targets are unquantifiable and complex;

Achievability: Some ATs ask the impossible,Footnote 8 yet are still not ambitious enough to achieve the CBD’s conservation objective;

Promulgation: General lack of awareness of biodiversity issues and the biodiversity targets. The CBD COP fails to attract some relevant actors, and this influences the adopted shared understandings;

Lack of a compliance mechanism: This poses a challenge to creating a clear practice of legality (Reference SmallwoodSmallwood, 2019).

Practical challenges for implementation include: the CBD’s broad scope, expanding subject-matter and failure to identify priority targets (Reference Mace, Barrett and BurgessMace et al., 2018), thus allowing parties to cherry pick on implementation; the complexity of biodiversity as a subject-matter, coupled by lack of data, capacity and funding; power asymmetries in relation to trade-related treaties (see Section 3.3.1); lack of vertical mainstreaming to production sectors at the domestic level (Section 3.4.1); lack of coordination between ministries, state and local authorities at the national level; and a general lack of prioritization (Reference Morgera and TsioumaniMorgera and Tsioumani, 2010).

Another key challenge for the CBD is for state parties to effectively implement global decisions into national obligations that are relevant to the localized context in which biodiversity loss and change happens. The CBD has a system of designated national focal points (representatives of state parties) to facilitate implementation through coordination, information sharing and planning at the national level, but they lack the capacity and support needed to inspire action across sectors to achieve national contributions toward global biodiversity targets (Reference Smith and MaltbySmith and Maltby, 2003).

Reference Redgwell, Bodansky, Brunnée and HeyRedgwell (2007) sees the top-down vertical journey toward national implementation as key to ensuring compliance with international obligations. As international obligations such as the ATs travel to the domestic level, they pass through different layers of governance and are exposed to different practices that shape and reinterpret them in different contexts. These layers are important because international obligations, such as those arising from the CBD, are an ongoing challenge rather than a “fait accompli,” and each stage of the journey can strengthen or weaken them (Reference SmallwoodSmallwood, 2019).

Scholars argue that domestic levels of governance can also shape and influence international processes from local to global (Reference Newell and BumpusNewell and Bumpus, 2012; Reference SmallwoodSmallwood, 2019). The connections between international and regional/domestic governance are poorly understood despite their indivisible nature (Reference KohKoh, 1997; Reference Koh1998; Reference SmallwoodSmallwood, 2019). The domestic level can strengthen global biodiversity governance during implementation without the ongoing constraints of achieving global consensus at the international level. Understandings formed at the domestic level may feed back to the CBD COP and influence and push forward shared understandings at the international level (Reference SmallwoodSmallwood, 2019; Reference Smallwood, Booth and Mounsey2021).

3.5 Transforming Global Biodiversity Governance

Based on the review of global biodiversity governance provided above, we identify the following four lessons learned for the transformative potential of global biodiversity governance.

3.5.1 Strengthen the Integration of International Treaties through Integrative Governance

Despite repeated attempts by the CBD COP to mainstream and attract political actors from agriculture, trade and development, it has made little progress in reaching out beyond international biodiversity-related institutions. In this respect, the Liaison Group of the Biodiversity-Related Conventions has organized several international workshops, known as the Bern I and Bern II processes, to collaborate jointly for the post-2020 biodiversity agenda.

Within the environmental regime, an integration of agendas that is also essential, yet to be realized, is between the global biodiversity and the climate change agendas. Despite many interrelated issues, the UNFCCC is largely absent from the biodiversity regime complex, with silos between climate and biodiversity responses remaining in science, international governance and civil society, thereby undermining opportunities for synergies in addressing climate change while also preserving ecosystems (Reference Deprez, Vallejo and RankovicDeprez et al., 2019). The focus on nature-based solutions at the 2019 UN Climate Summit marked an emerging understanding of the need for convergence between climate and biodiversity within the international political agenda. The chairs of two main science–policy international interfaces, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, have expressed their will to work together, and their first meeting was held in December 2020, resulting in a joint report (Reference Pörtner, Scholes and AgardPörtner et al., 2021). These efforts should be pursued and multiplied.

Besides the environmental regime, the main regime impacting biodiversity is the trade regime, due to large-scale trade in natural resources. Since its initiation, the CBD has called for integrative biodiversity governance through a comprehensive ecosystem approach, rather than focusing solely on species or genetic resource conservation (see above). However, the true realization of this comprehensive approach has been neglected due to an emphasis on profits from trade in individual species and genetic resources. Critiques of the biodiversity regime suggest that it is too much in line with trade agendas and therefore lacks the ability to achieve transformative change by implicitly supporting neoliberal globalization, especially embedded in the trade regime, as opposed to challenging it (Reference Brand and WissenBrand and Wissen, 2013; Reference Brand, Görg, Hirsch and WissenBrand et al., 2008; Reference MacDonaldMacDonald, 2010) with broader, ecosystemic approaches.

Attempts have been made to mainstream biodiversity in the trade, agriculture, cultural and development regimes. The CBD has aimed to influence the agendas of other international initiatives and conventions within the regime complex through global targets (Reference Harrop and PritchardHarrop and Pritchard, 2011). While the strategic plan and global target for 2010 was adopted for the CBD only, the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020, including the ATs, was adopted as an overarching framework on biodiversity reaching out to the other biodiversity-related conventions, the entire UN system and all other partners engaged in biodiversity conservation and sustainable development policy. Although most of the ATs have not been met, the wide endorsement by these partners showed a sign of broadened recognition of the role of biodiversity conservation and sustainable use for human well-being.

This recognition was further broadened by the adoption of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development by the UN General Assembly in 2015, with its seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Biodiversity appears as an important component of these goals: Goals 14 and 15 explicitly address life below water and on land with sub-targets consistent with the ATs (see Chapter 1). Biodiversity also plays an essential role in the achievement of most of the other SDGs, including climate action with forests as climate adaptation and mitigation options, or zero hunger with agricultural genetic resources being essential for food security (CBD Secretariat, 2017). This political upgrading of biodiversity, as expressed by the SDGs, is one important step for potentially obtaining transformative change to reverse the negative trend for biodiversity, even if the effectiveness of Agenda 2030 is yet to be shown. All in all, coordination attempts exist at the international level to mainstream biodiversity, but should be strengthened for transformative change.

3.5.2 Strengthen Inclusive Governance through the Inclusion of Nonstate Actors

Polycentric governance processes including nonstate actors are increasing in global biodiversity governance, both within the CBD and more broadly across the biodiversity regime complex (Reference Kok, Widerberg, Negacz, Bliss and PattbergKok et al., 2019). Inclusion of various state, market and civil society actors would empower those whose interests are not sufficiently recognized, represent transformative values and facilitate co-construction of shared understandings and social learning between actors. The question for the implementation of the CBD Post-2020 GBF is how to best involve underrepresented actors into the hierarchical and state-led process.

Stronger representation of stakeholders, such as IPLC and NGOs, that have been underrepresented so far could enable true knowledge-sharing to inform international decision-making (Reference Tengö, Hill and MalmerTengő et al., 2017). So far, IPLC have been particularly successful in increasing their participation in the CBD and in strengthening their position. IPLC have been successful in challenging dominant discourses around biodiversity, including neoliberal valuations of nature (see Chapter 2), and in highlighting their possible contribution to the realization of the new post-2020 biodiversity targets, although this recognition at the global level is not always reflected during implementation at the domestic level.

The current role of governments in biodiversity governance may be challenged by nonstate and subnational actors to provide the stronger leadership needed to accelerate the momentum for biodiversity and to strengthen international and national policies. Civil society initiatives could scrutinize national government actions and their contributions to the realization of the goals and targets of the CBD and step up their ambition levels and increase action. Hybrid initiatives involving both public and private actors may also offer a point of leverage for transformation, although there are risks that inclusion of private business actors may preclude transformation. Analyses of international nonstate action initiatives for biodiversity show that to increase the legitimacy of their efforts, business actors usually prefer to cooperate with civil society and/or public actors rather than act alone (Reference Negacz, Widerberg, Kok and PattbergNegacz et al., 2020).

The development and implementation of the Sharm-el-Sheik to Kunming Action Agenda also poses challenges to the CBD (Reference Kok, Widerberg, Negacz, Bliss and PattbergKok et al., 2019). Solutions included in the action agenda aim to: ensure nonstate actors actively contribute to biodiversity goals; avoid overlaps and confusion in a plethora of nonstate actors and action to achieve biodiversity goals; and avoid the risk of national governments shirking established norms and responsibilities under the CBD, leaving action to nonstate and subnational actors. This would require that the CBD: provides a collaborative framework for nonstate action within the CBD and Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework that builds upon existing and emerging activities of nonstate action; organizes monitoring and review as part of an accountability framework of state and nonstate actors as part of the wider responsibility and transparency framework under the CBD; and provides for learning, capacity-building and follow-up action between state and nonstate actors (Reference Chan, van Asselt and HaleChan et al., 2015; Reference Kok and LudwigKok and Ludwig, 2021).

3.5.3 Improve Implementation

Barriers to CBD implementation include the use of poorly designed soft law, “political” targets (as opposed to scientifically informed binding targets or protocols), reliance on NBSAPs and national reports for implementation, lack of transparent means of review, the inability of the CBD to engage economic and production sectors and business more broadly and the lack of any consequences for failure to meet targets.

Implementation is severely hindered by the lack of accountability mechanisms. The CBD Art 27 dispute mechanism has never been used, no compliance committee has been adopted and there is no compliance mechanism, whether it be through an enforcement mechanism in the form of financial or trade sanctions, such as in CITES (under which countries risk trade sanctions) or facilitative in the form of “naming and shaming,” such as in the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change (under which individual countries can make voluntary pledges, with a comparison and review of each state party’s performance). Subsequently, if state parties fail to fulfill their obligations (reporting, implementation, contribution toward the ATs), there are no consequences (Reference Le PrestreLe Prestre, 2017). The absence of accountability and the lack of a compliance mechanism create an obstacle to effective implementation and efficient governance, and are ultimately a result of political choice, reflecting the low priority placed on biodiversity. The CBD needs to introduce a more structured approach to implementation than practiced so far to address biodiversity loss and decline on a global level.

The CBD review mechanism could be strengthened. While most state parties submit national reports, the feedback given by the CBD on individual state party progress and their contribution to the realization of international targets lacks transparency. A strengthened review mechanism would facilitate a more structured approach to implementation, for example the provision by the CBD of basic information on who implements which provisions, and national progress toward global goals (Reference SmallwoodSmallwood, 2019). NGOs have taken the lead to break down data in relation to compliance in a more meaningful way to highlight individual state party progress toward the ATs (Reference SmallwoodSmallwood, 2019).

There are discussions within the CBD for adoption of a strengthened review and accountability mechanism.Footnote 9 Increased political will is needed to adopt such mechanisms, but if agreed to they would strengthen implementation. Negotiations to adopt compliance mechanisms can be quite time-consuming and burdensome (Reference Morgera, Tsioumani and BuckMorgera et al., 2014), but the successful agreement to create a compliance committee during the Paris Agreement climate negotiations (Reference BodanskyBodansky, 2016) shows that this may not be beyond the reach of the CBD. Agreement on strong means of compliance may be politically difficult, but increased transparency and introducing a system of accountability (including a compliance committee) through a “pledge, review and ratchet” mechanism would help facilitate CBD compliance (Reference Kok, Widerberg, Negacz, Bliss and PattbergKok et al., 2019).

Another approach could be through the adoption of a “naming but not shaming” approach, which, rather than punish noncompliance, aims to support state parties struggling to reach their goals through increased financial support and capacity-building. This could be achieved through the development of the NBSAP peer review mechanism (Reference SmallwoodSmallwood, 2019). Learning and accountability approaches may also be combined to further strengthen implementation.

Focus should also be given to strengthening multilevel governance processes to improve implementation. International obligations can be strengthened or weakened through inclusive and integrative practices during implementation; therefore, careful attention must be paid to their dynamics at all levels of governance. If resourced properly, the CBD national focal points and other relevant actors could play a greater role in implementation, and better catalyze action across sectors to achieve national contributions toward global biodiversity objectives, targets and goals. Failure to engage all relevant actors at the national level is largely because implementation of biodiversity policies falls upon conservation sectors with limited or no buy-in from production sectors. Strengthened integrative processes at the national level are essential to engage production sectors to address biodiversity loss.

3.5.4 Increase Anticipatory Adaptive Capacities

In some respects, the CBD has shown its ability to learn and adapt to the ongoing challenge of nature conservation, sustainable use and benefit sharing. It has gradually developed more defined strategic plans with targets, as well as specific work programs and guidance for state parties. While these efforts should not be underestimated, a key challenge for the CBD is to evolve more rapidly and counter the escalating rates of biodiversity loss.

The preparation of the Post-2020 Framework has been an important moment of reflection, deliberation and joint learning as a basis for changing course guided by the OEWG. Quite extensive regional and thematic consultations have been held in-person before the second meeting of the OEWG, and online thereafter, that have fed into the negotiations. They have highlighted important elements of the Convention, including mainstreaming, finance and capacity-building in further implementing the Post-2020 Framework. The results of the IPBES assessments and especially the Global Assessment (IPBES, 2019), and to a lesser extent also the CBD Global Biodiversity Outlook (SCBD, 2020) and the two Local Biodiversity Outlooks (Forest Peoples Programme et al., 2020), have played an important role in the process by informing the negotiations and strengthening the science–policy interface, including through its emphasis on the co-construction of transdisciplinary knowledge (Reference Díaz, Demissew and CarabiasDíaz et al., 2015).

Improved transparency of efforts of state parties and nonstate actors, and identification of ambition and implementation gaps, are key to strengthening the adaptive capacity of the CBD. Improved monitoring of implementation attributed to specific state parties (which has up to 2020 not been the case), stocktaking, review and possible follow-up in terms of a “ratchet” mechanism in the Post-2020 Framework (as discussed above) would allow for more timely course corrections and create a basis for joint learning between state parties, and between state parties and nonstate actors.

A further underlying limitation of transformative governance by the CBD is its UN context, which requires consensus from all state parties on CBD COP decisions, thus allowing little room for adaptive governance through experimentation and reflexivity or anticipatory governance due to lack of political will. One actor of change could be the CBD Secretariat. CBD parties have indeed traditionally given a rather large leeway to the CBD Secretariat (Reference SiebenhünerSiebenhüner, 2007), although perhaps not in comparison to other biodiversity conventions such as Ramsar (Reference Bowman, Stokke and ThommessenBowman, 2002) and CITES.

Does the secretariat of the CBD provide institutional memory that lends itself well to the adaptability needed to achieve transformative governance? The secretariat interacts with informal expert and liaison groups to advise the COP, drafts background documents and agendas, and facilitates negotiations, and is thereby able to play a key role in the adaptability of the CBD. Yet the creation of the OEWG to develop the Post-2020 Framework marked a change to the freedom given to the secretariat, as the OEWG process is mostly managed by cochairs, representing state parties. The emphasis on the OEWG process to inform the Post-2020 Framework, led by state parties, suggests that the secretariat’s contribution to adaptability within governance processes has lessened. While the secretariat still has significance in intergovernmental cooperative processes (Reference Biermann and SiebenhünerBiermann and Siebenhüner, 2009), its roles as an emerging political actor and a “norm entrepreneur” (Reference JinnahJinnah, 2008; Reference Jinnah2011; Reference Jinnah, Chasek and Wagner2012) have been toned down and this may signify a challenge to the pace of adaptability within the CBD, unless political will for transformative change is deepened among state parties.

Reconfiguring how the CBD operates is complex and lengthy due to the restraints of the institutional mechanisms in place, such as gaining multilateral consensus and the adoption of protocols. However, procedurally it is possible and under the Convention there is a process for actors (state and nonstate) to identify new and emerging issues for future work programs relating to the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the use of genetic resources (Reference SiebenhünerSiebenhüner, 2007). This mechanism offers potential to advance and adapt governance processes at the CBD (Reference Le PrestreLe Prestre, 2017). Ambitious, anticipatory and innovative proposals can be introduced to the CBD as “new and emerging issues” with the potential to form future work programs (see Chapter 7). The agreement by state parties on the criteria for the adoption of new and emerging issues by the COP is an essential step forward to make this procedural mechanism workable, and their application has proved to be challenging in practice.

Another important change in how governance takes place through the CBD could be through initiating change in the scales of governance, for example by breaking down the “global” scale of the CBD and achieving agreement on the adoption of differentiated approaches according to regions, priority ecosystems, countries, sectors or themes, following the example of the Convention on Migratory Species. This would change the dynamics of agreement and operation and would be a step toward more meaningful large-scale action on biodiversity at a subglobal level, while still in a unified global framework.

3.6 Conclusion

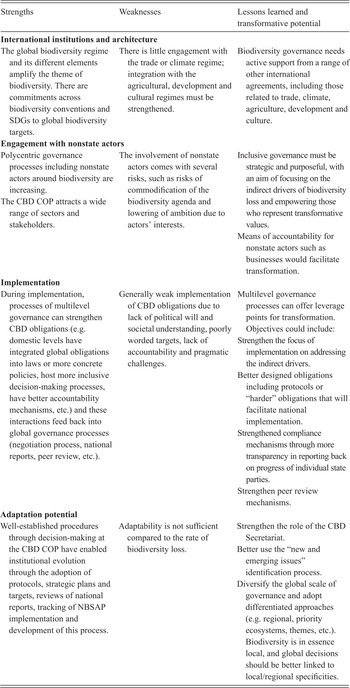

Currently, global biodiversity governance fails to address the indirect drivers of biodiversity loss, and is unable to confront the economic, political and social paradigms that drive the destruction of biodiversity globally. This chapter has presented the current state of global biodiversity governance and suggested how it could be improved, thus transforming biodiversity governance. We conclude with Table 3.2, which summarizes the strengths, weaknesses and transformative potential of global biodiversity governance.