1.1 Introduction: The Third Era in Global Biodiversity Governance

This book is written at a vital time for biodiversity around the world. Biodiversity is threatened more than ever before in human history, and nature and its vital contributions to people are deteriorating worldwide, as highlighted by various recent reports (CBD, 2020a; EEA, 2019; IPBES, 2019; Reference Almond, Grooten and PetersenWWF, 2020). This is not only a problem for these ecosystems and their inhabitants, but also for humans, since we depend on biodiversity for many vital processes such as food production and provision of natural resources. These risks of biodiversity loss are increasingly recognized among policymakers, academics and society at large (IPBES, 2019; WEF, 2021).

The worldwide deterioration of biodiversity is taking place despite over half a century of efforts to combat biodiversity loss by governments, civil society and, increasingly, business, at all levels of governance from the local to the global. Past and ongoing efforts are therefore not effectively supporting the conservation and sustainable and equitable use of biodiversity, and this worldwide failure to address biodiversity loss has created a growing consensus that fundamental, transformative changes are needed in order to reverse these trends, or “bend the curve of biodiversity loss” (IPBES, 2019; Reference Mace, Barrett and BurgessMace et al., 2018).

This increasing attention for transformative change can be seen as the start of a new, third era in global biodiversity governance. During the first era, early nature conservation policies were developed in silos – the focus was on conserving biodiversity and developing and better managing protected areas. These older intergovernmental processes, such as the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands and the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS), date back to the 1970s.

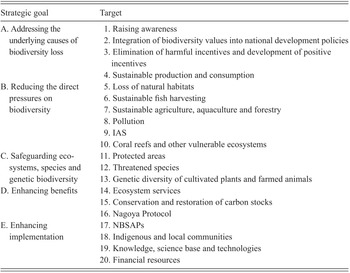

The central intergovernmental biodiversity process, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), was adopted in 1992 at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), along with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) (Reference Le PrestreLe Prestre, 2002). The CBD has three main objectives, namely the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of its components and the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources (CBD, 1992). In 2002, parties to the CBD agreed on targets to significantly reduce of the rate of biodiversity loss by 2010. After this target was not met, the CBD developed new targets for 2020, the Aichi targets, as part of its Strategic Plan 2011–2020 (Table 1.1). With this strategic plan, a second era started as attention shifted toward mainstreaming biodiversity in the most relevant policy domains and sectors, such as forestry and fisheries. However, most of these targets, again, were not met (CBD, 2010; 2020b) (also see Chapter 3).

| Strategic goal | Target |

|---|---|

| A. Addressing the underlying causes of biodiversity loss |

|

| B. Reducing the direct pressures on biodiversity |

|

| C. Safeguarding ecosystems, species and genetic biodiversity |

|

| D. Enhancing benefits |

|

| E. Enhancing implementation |

|

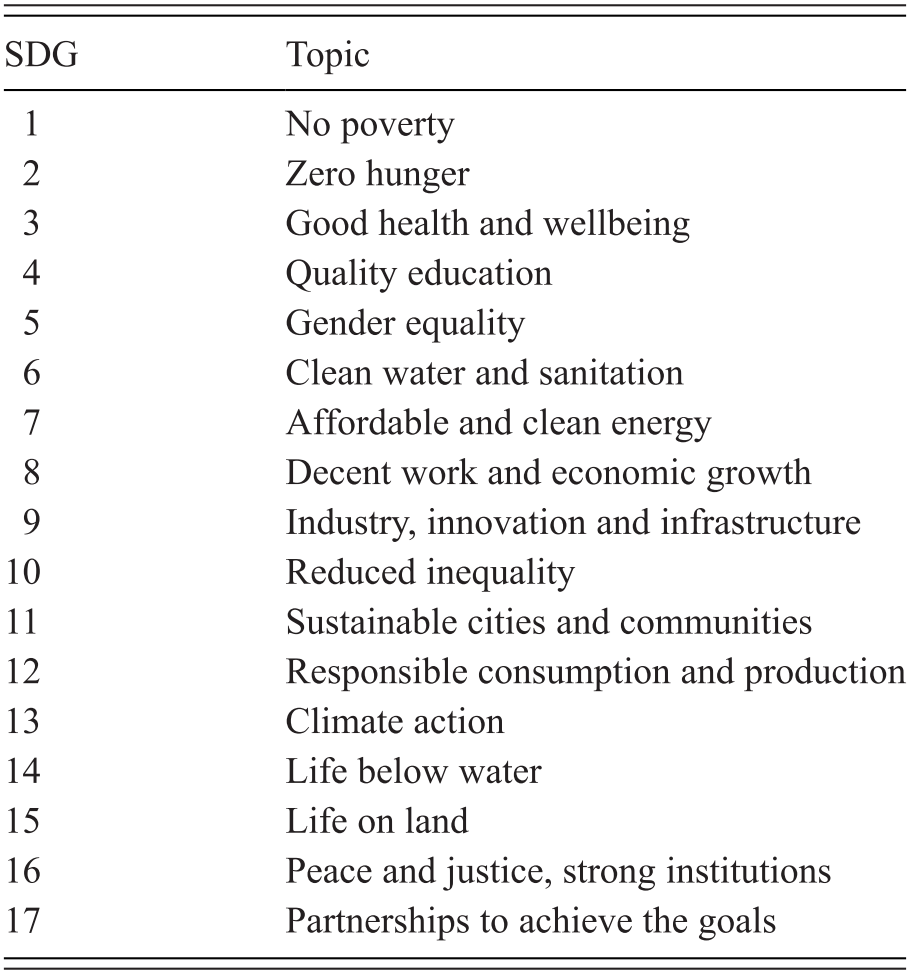

The adoption of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015 can be seen as the start of the third biodiversity governance era. Biodiversity concerns are well integrated into the SDGs (See SDG 14 and 15 in Table 1.2), and are part of a broader transformative change agenda for sustainability and environmental justice. The focus of biodiversity policy has thus broadened over time, and the call for transformative change now recognizes the need for deepening such efforts. In this third era, all three strategies are recognized as vital: stepping up protection and restoration of nature, broadening biodiversity efforts across society and deepening effects to enable transformative change (as elaborated in Section 1.3 below). With the COVID-19 pandemic, discussions on the urgency of such transformative change and changing our relationship with nature have further intensified (see e.g. Reference Platto, Xue and CarafoliPlatto et al., 2020 and Chapter 5).

Table 1.2 The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (UN, 2015)

| SDG | Topic |

|---|---|

| 1 | No poverty |

| 2 | Zero hunger |

| 3 | Good health and wellbeing |

| 4 | Quality education |

| 5 | Gender equality |

| 6 | Clean water and sanitation |

| 7 | Affordable and clean energy |

| 8 | Decent work and economic growth |

| 9 | Industry, innovation and infrastructure |

| 10 | Reduced inequality |

| 11 | Sustainable cities and communities |

| 12 | Responsible consumption and production |

| 13 | Climate action |

| 14 | Life below water |

| 15 | Life on land |

| 16 | Peace and justice, strong institutions |

| 17 | Partnerships to achieve the goals |

Despite growing societal and academic interest in transformative change, it is far from clear how to enable, achieve or accelerate transformative change for biodiversity. This book aims to provide and further develop a governance perspective on achieving such transformative change. The book captures the state-of-the-art knowledge on transformative biodiversity governance and further explores its practical implications in various contexts and issues relevant for the long-term biodiversity policy agenda.

The book is written against the backdrop of the development of the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), the new global framework following the CBD Strategic Framework 2011–2020 and its Aichi targets. At the time of writing, the GBF was expected to be adopted in 2022 at the 15th Conference of the Parties of the CBD (COP15) in Kunming, China. COP15 was originally due to be held in 2020 but was postponed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The GBF represents the guiding policy framework for biodiversity action across societies and governments, and, in our view, should provide a global answer to shaping transformative change in the multilateral system, and through implementation at the national and subnational levels by state and nonstate actors. We hope that the book will contribute to transformative action for biodiversity in the implementation of the Post-2020 GBF around the world over the coming years.

This first chapter is organized as follows. We first set the stage by providing an overview of the current state of biodiversity, causes of biodiversity loss and its implications. We then introduce the concepts of transformative change and governance. The two final sections explain the book’s logic and organization, and provide an overview of the book.

1.2 The Problem of Biodiversity Loss and the Potential for Transformative Change

According to the Global Assessment of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES GA),Footnote 1 “nature, and its vital contributions to people, which together embody biodiversity and ecosystem functions and services, are deteriorating worldwide” (Reference Díaz, Settele and BrondízioDíaz et al., 2019: 10). Most indicators of the state of nature are declining, including the number and population size of wild species, the number of local varieties of domesticated species, the distinctness of ecological communities and the extent and integrity of many terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Around one million species are threatened with extinction. Biodiversity in areas owned, managed or used by Indigenous People and local communities (IPLC) is declining less rapidly than elsewhere (Reference Díaz, Settele and BrondízioDíaz et al., 2019).

This biodiversity loss has accelerated over the past fifty years (the period analyzed by the IPBES GA), and is caused by the following direct drivers: land and sea use change, with agricultural expansion representing the most important form of land-use change; direct exploitation, and especially overexploitation, of animals, plants and other organisms, mainly through harvesting, logging, hunting and fishing; climate change, which is becoming an increasingly important driver; pollution and invasive alien species. Land-use change is the main direct driver in terrestrial areas, and direct exploitation is the most important one in marine systems. These trends in nature and its contributions to people are projected to worsen over the coming decades, unevenly in different regions. These direct drivers are influenced by indirect drivers, or underlying causes, which can be demographic (e.g. human population dynamics), sociocultural (e.g. consumption patterns), economic (e.g. production and trade), technological, or relating to institutions, governance, conflicts and epidemics. These indirect drivers are underpinned by societal values and behaviors (Reference Díaz, Settele and BrondízioDíaz et al., 2019).

Biodiversity issues are an integral part of broader sustainable development debates, and are intertwined with many other sustainability issues, including climate change. Humans depend on nature and biodiversity for human health through the production of food, medicines and clean water, among others, and the provision of natural resources, such as timber. Nature also provides regulatory ecosystem services that are vital for humans, including regulating air quality and climate. Nature is thus essential for achieving the SDGs, and biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation will undermine progress toward the vast majority of the SDG targets, as the capacity of nature to provide these services has declined significantly over the last decades.

In this context, it is important to address biodiversity loss coherently with climate change mitigation and adaptation, since there are both synergies and trade-offs among biodiversity and climate change efforts. Limiting climate change to well below 2 degrees Celsius is crucial to reducing the impacts on nature and ecosystem services, but some large-scale land-based climate change mitigation measures, such as large-scale afforestation and reforestation or bioenergy crop development, will have negative impacts on biodiversity. Other efforts, such as ecosystem restoration or avoiding and reducing deforestation, can provide synergies between climate and biodiversity goals (Reference Díaz, Settele and BrondízioDíaz et al., 2019; Reference Pörtner, Scholes and AgardPörtner et al., 2021).

As discussed above, biodiversity policy has so far not been able to deliver the intended results, and it is clear that conservation efforts need to be improved, broadened and deepened: “Goals for conserving and sustainably using nature and achieving sustainability cannot be met by current trajectories, and goals for 2030 and beyond may only be achieved through transformative changes across economic, social, political and technological factors” (Reference Díaz, Settele and BrondízioDíaz et al., 2019: 14). Explorative scenario-projections, covering a wide range of plausible socioeconomic pathways and biodiversity policies, indicate that global biodiversity will continue to decline, even under optimistic socioeconomic pathways oriented toward sustainability. Only specific solution-oriented scenarios that step up ambition levels in conservation and restoration, address indirect drivers of biodiversity loss and capitalize on nature-based solutions, which use nature to address societal challenges, are able to bend the curve while also mitigating climate change (Kok et al., under review; Reference Leclère, Obersteiner and BarrettLeclère et al., 2020). However, many of the social dimensions of such scenario analyses require further attention to evaluate the equity implications of these future pathways (Reference Ellis and MehrabiEllis and Mehrabi, 2019; Reference Mehrabi, Ellis and RamankuttyMehrabi et al., 2018; Reference Otero, Farrell and PueyoOtero et al., 2020; Reference Schleicher, Zaehringer and FastréSchleicher et al., 2019). Transformative change is thus urgently needed.

1.3 Understanding, Shaping and Delivering Transformative Change and Governance

1.3.1 Transformative Change

As accurately noted by Reference OtsukiOtsuki (2015: 1): “Current debates on sustainable development are shifting their emphasis from the technocratic and regulatory fix of environmental problems to more fundamental and transformative changes in social-political processes and economic relations.” However, discussions on societal transformations are of course not new (see for a detailed overview of the literature on sustainability transformations Reference Linnér and WibeckLinnér and Wibeck [2019]). The concept of social transformation generally “implies an underlying notion of the way society and culture change in response to such factors as economic growth, war, or political upheavals” (Reference CastlesCastles, 2001: 15). Often-named examples include the “great transformation” (Reference PolanyiPolanyi, 1944) in Western societies brought about by industrialization and modernization, or more recent changes such as decolonization (Reference CastlesCastles, 2001).

Reference Scoones, Stirling and AbrolScoones et al. (2020) distinguish structural, systemic and enabling approaches to conceptualizing transformations, with structural approaches focused more on societal change, systemic approaches on transitions in specific socioecological systems, and enabling approaches on developing capacities for change. Others differentiate between discussions on transformations and transitions (Reference Grin, Rotmans, Schot, Geels and LoorbachGrin et al., 2010), with the former focused on societal change and the latter on change in subsystems (e.g. the food, energy or mobility systems). These two approaches are also rooted in different literatures (Reference Hölscher, Wittmayer and LoorbachHölscher et al., 2018; Reference Loorbach, Frantzeskaki and AvelinoLoorbach et al., 2017). In our view, all these different approaches can be seen as complementary (see Chapter 4 for a more elaborate overview of the literatures on transformations and transitions, and their governance).

Transformative change can be differentiated from incremental or gradual change, which often occurs as a result of disturbances and is often aimed at resolving problems without changing existing systems or structures, although there are incremental changes that can contribute to transformations (Reference Termeer, Dewulf and BiesbroekTermeer et al., 2017). Transformative change incorporates both personal and social transformation (Reference Chaffin, Garmestani and GundersonChaffin et al., 2016; Reference OtsukiOtsuki, 2015), and includes shifts in values and beliefs, and patterns of social behavior (Reference Chaffin, Garmestani and GundersonChaffin et al., 2016).

Reference Burch, Gupta and InoueBurch et al. (2019) highlight that transformations can be studied analytically, normatively and critically. Although debates among academics and policymakers on transformative change toward sustainability have often remained rather apolitical, a more critical perspective has emerged that incorporates politics, power and equity issues in the debates on transformation (see e.g. Reference Chaffin, Garmestani and GundersonChaffin et al., 2016; Reference Lawhon and MurphyLawhon and Murphy, 2012). Transformations include the making of “hard choices” by decision-makers (Reference MeadowcroftMeadowcroft, 2009: 326). Reference Blythe, Silver and EvansBlythe et al. (2018) highlight the potential risks of apolitical approaches to transformative change, arguing that consideration of the politics of transformative change is necessary to address these risks, which include: shifting the burden of response onto vulnerable parties; the transformation discourse may be used to justify business-as-usual, pays insufficient attention to social differentiation and excludes the possibility of non-transformation or resistance; and insufficient treatment of power and politics can threaten the legitimacy of the discourse of transformation. In this book we recognize these risks and actually place them center stage by focusing on the governance of and for such transformations.

The IPBES GA defines transformative change as a fundamental, system-wide reorganization across technological, economic and social factors, including paradigms, goals and values (Reference Díaz, Settele and BrondízioDíaz et al., 2019). Building on this definition, we here define transformative change as follows:

a fundamental, society-wide reorganization across technological, economic and social factors and structures, including paradigms, goals and values.

With this renewed definition, we emphasize changes in generic, societal structures. Such a society-wide transformation encompasses transitions in specific subsystems or sectors, and is necessary, since current societal structures inhibit sustainable development – they actually represent the underlying causes of biodiversity loss. Thereby, transformative change addresses both generic societal underlying causes and underlying causes in specific transitions (see Chapter 4 for an extensive discussion on the relationships between transformations, transitions, transformative change and transformative governance).

Transformative solutions are often synergistic: By focusing on the indirect drivers, they simultaneously address multiple sustainability issues, since the same indirect drivers simultaneously cause various problems. An example is the development of healthy and sustainable food systems, including through reducing production and consumption of animal products (especially in developed and newly industrialized countries), which can support progress on the majority of SDGs, and also addresses animal interests (Reference Visseren-HamakersVisseren-Hamakers, 2020). With this emphasis on the societal underlying causes of environmental problems, environmental policy becomes less “environmental” and increasingly integrated into mainstream policy and politics, becoming an integral part of discussions on the economy, innovation, development and societal values (also see Reference BiermannBiermann, 2021).

While this book is focused on transforming biodiversity governance, we explicitly reflect on this issue as embedded in discussions on transformative change toward sustainability more broadly. We do so because biodiversity and other environmental and social justice issues are interwoven, and broader societal transformations are necessary to address all of these sustainable development issues.

1.3.2 Transformative Governance

While a burgeoning literature discusses transformative change, less research investigates how to govern such transformations (Reference Chaffin, Garmestani and GundersonChaffin et al., 2016; Reference Patterson, Schulz and VervoortPatterson et al., 2017), and very few authors have specifically used the concept of transformative governance (Reference Chaffin, Garmestani and GundersonChaffin et al., 2016; Reference Colloff, Martín-López and LavorelColloff et al., 2017; Reference Visseren-Hamakers, Razzaque and McElweeVisseren-Hamakers et al., 2021). Reference Chaffin, Garmestani and GundersonChaffin et al. (2016: 400) define transformative environmental governance as “an approach to environmental governance that has the capacity to respond to, manage, and trigger regime shifts in coupled socio-ecological systems at multiple scales.” It thus has the capacity to shape nonlinear change. An important literature related to transformative governance is work on “transition management,” defined as “the attempt to influence the societal system into a more sustainable direction, ultimately resolving the persistent problem(s) involved” (Reference Grin, Rotmans, Schot, Geels and LoorbachGrin et al., 2010: 108). The thinking on governing transformative change has thus so far focused on systemic – and not necessarily societal – change.

Hence, there is a difference between the concepts of transformative change and transformative governance, with change referring to the actual shift and governance to “steering” the shift, although some authors do not clearly differentiate between the two concepts (e.g. Reference Chaffin, Garmestani and GundersonChaffin et al., 2016). An important question is the extent to which the shift can actually be governed (Reference MeadowcroftMeadowcroft, 2009), with some authors noting that transformative sustainable development “is a contingent and creative process, which cannot be readily planned” (Reference OtsukiOtsuki, 2015: 4). Reference Chaffin, Garmestani and GundersonChaffin et al. (2016) list several constraints and opportunities for transformative governance, with constraints including: entrenched power relations, capitalism and dominant economic and political subsystems, and cognitive limits of humans; and opportunities including: law, formal institutions and governmental structure, previous success of adaptive governance, and human agency and imagination (Reference Chaffin, Garmestani and GundersonChaffin et al., 2016: 411). Interestingly, all of these opportunities and constraints are part of the underlying causes of biodiversity loss that need to be addressed through transformative change.

Transformative governance is deliberate (Reference Chaffin, Garmestani and GundersonChaffin et al., 2016), and inherently political (Reference Blythe, Silver and EvansBlythe et al., 2018; Reference Patterson, Schulz and VervoortPatterson et al., 2017), since the desired direction of the transformation is negotiated and contested, and power relations will change because of the transformation (Reference Chaffin, Garmestani and GundersonChaffin et al., 2016). Current vested interests (including in dominant technologies) are expected to inhibit, challenge, slow or downsize transformative change, among others, through “lock-ins” (see e.g. Reference Blythe, Silver and EvansBlythe et al., 2018; Reference Chaffin, Garmestani and GundersonChaffin et al., 2016; Reference MeadowcroftMeadowcroft, 2009). Transformative governance is about framing and agenda setting, and requires leadership, financial investment and capacity for learning. Also, the change needs to be increasingly institutionalized (Reference Chaffin, Garmestani and GundersonChaffin et al., 2016).

Literature on earth system governance has explored different ways of conceptualizing the governance of transformations. Reference Burch, Gupta and InoueBurch et al. (2019) and Reference Patterson, Schulz and VervoortPatterson et al. (2017) differentiate between the following conceptualizations of governing transformations:

– Governance for transformations (i.e. governance that creates the conditions for transformation to emerge from complex dynamics in socio-technical-ecological systems),

– Governance of transformations (i.e. governance to actively trigger and steer a transformation process),

– Transformations in governance (i.e. transformative change in governance regimes).

Based on these insights and earlier definitions on environmental governance (Reference Biermann, Betsill and GuptaBiermann et al., 2010), we here define transformative governance as:

The formal and informal (public and private) rules, rule-making systems and actor-networks at all levels of human society (from local to global) that enable transformative change, in our case, towards biodiversity conservation and sustainable development more broadly

Since governing transformative change is inherently difficult because of its political character, transformative governance needs to take on board various lessons learned from the governance literature. We therefore propose that, based on Reference Visseren-Hamakers, Razzaque and McElweeVisseren-Hamakers et al. (2021), transformative governance includes five governance approaches, namely: integrative, inclusive, transdisciplinary, adaptive and anticipatory governance, which are based on various niches in the governance literature. These governance approaches have been studied separately in detail, and in the literature on sustainability transformations combinations of these approaches are often recognized as important (Reference Linnér and WibeckLinnér and Wibeck, 2019). We hypothesize that governance can only become transformative when the five governance approaches are (Reference Visseren-Hamakers, Razzaque and McElweeVisseren-Hamakers et al., 2021):

a) focused on addressing the underlying causes of unsustainability;

b) implemented in conjunction; and

c) operationalized in the following specific manners.

Thereby, in order to be transformative, governance needs to be:

1. Integrative, operationalized in ways that ensure solutions also have sustainable impacts at other scales and locations, on other issues and in other sectors (see e.g. Reference Castán Broto, Trencher, Iwaszuk and WestmanCastán Broto et al., 2019; Reference Chaffin, Garmestani and GundersonChaffin et al., 2016; Reference Visseren-HamakersVisseren-Hamakers, 2015; Reference Visseren-Hamakers2018a; Reference Visseren-Hamakers2018b; Reference Visseren-Hamakers, Razzaque and McElweeVisseren-Hamakers et al., 2021; Reference Wagner and WilhelmerWagner and Wilhelmer, 2017);

2. Inclusive, in order to empower and emancipate those whose interests are currently not being met and who represent values that constitute transformative change toward sustainability (see e.g. Reference Biermann, Betsill and GuptaBiermann et al., 2010; Reference Blythe, Silver and EvansBlythe et al., 2018; Reference Chaffin, Garmestani and GundersonChaffin et al., 2016; Reference Li and KampmannLi and Kampmann, 2017; Reference MeadowcroftMeadowcroft, 2009; Reference OtsukiOtsuki, 2015);

3. Adaptive, since transformative change and governance, and our understanding of them, are moving targets, so governance needs to enable learning, experimentation, reflexivity, monitoring and feedback (see e.g. Reference Blythe, Silver and EvansBlythe et al., 2018; Reference Chaffin, Garmestani and GundersonChaffin et al., 2016; Reference MeadowcroftMeadowcroft, 2009; Reference OtsukiOtsuki, 2015; Reference van den Bergh, Truffer and KallisVan den Bergh et al., 2011; Reference Wagner and WilhelmerWagner and Wilhelmer, 2017; Reference WolframWolfram, 2016);

4. Transdisciplinary,Footnote 2 in ways that recognize different knowledge systems, and support the inclusion of sustainable and equitable values by focusing on types of knowledge that are currently underrepresented (see e.g. Reference Blythe, Silver and EvansBlythe et al., 2018; Reference Colloff, Martín-López and LavorelColloff et al., 2017; Reference Chaffin, Garmestani and GundersonChaffin et al., 2016; Reference Keitsch and VermeulenKeitsch and Vermeulen, 2021; Reference MoserMoser, 2016; Reference Scoones, Stirling and AbrolScoones et al., 2020); and

5. Anticipatory, in ways that apply the precautionary principle when governing in the present for uncertain future developments, and especially the development or use of new technologies (see e.g. Reference Burch, Gupta and InoueBurch et al., 2019; ESG, 2018; Reference GustonGuston, 2014).Footnote 3

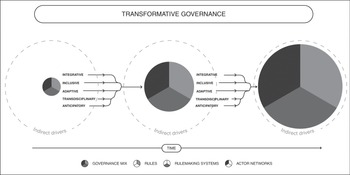

Figure 1.1 Transformative governance

Governance (including rules, rulemaking systems and actor networks) becomes transformative if integrative, inclusive, adaptive, transdisciplinary and anticipatory governance approaches are: 1) implemented in conjunction; 2) operationalized in a specific manner; and 3) focused on addressing the indirect drivers underlying sustainability issues. Over time, governance then becomes increasingly capable of addressing the indirect drivers (as indicated by the growth of the governance mix from left to right, i.e. over time).

With this operationalization, transformative governance is focused on the underlying societal causes of unsustainability while being cognizant of relationships between issues, sectors, scales and places, aiming to emancipate those holding transformative sustainability values, governing through learning, incorporating different knowledge systems and taking a precautionary stance in situations of uncertainty. Any actor can contribute to transformative governance, and governance mixes can be polycentric in character, encompassing initiatives by actors operating in different places, sectors or at different levels of governance. All actors can regularly evaluate whether the governance mix includes the necessary governance instruments to address the indirect drivers underlying a specific sustainability issue, and governance mixes will need to evolve as sustainability transformations progress. Over time, governance will become increasingly transformative, and transformative governance will become easier, as societal structures increasingly become sustainable (see also Chapter 4).

As a whole, the book does not take a specific stance on the various academic and theoretical debates on transformative change and governance, but embraces the diversity of approaches. Although this first chapter highlights structural approaches to transformative change, given the definitions of transformative change and governance above, we see this structural change as embedding systemic and enabling approaches to transformations. The various chapters in the book can be positioned differently in the various approaches:

1.4 Characteristics, Aim and Research Questions of the Book

The aim of the book is to enhance our understanding of ways forward for transformative biodiversity governance. With this, the book aims to inform the development and implementation of transformative biodiversity policies and action.

The book addresses the following research questions:

What are lessons learned from existing attempts to:

a) Address the underlying causes of biodiversity loss?

b) Apply different approaches to, and instruments for, transformative governance (as operationalized in the above)?

The book is part of the Earth System Governance series at Cambridge University Press, which aims to draw lessons from the research of the global Earth System Governance Project, a global network of scholars in the social sciences and humanities working on governance and global environmental change. By drawing lessons from past, and explaining current, attempts for transformative biodiversity governance against the backdrop of the Post-2020 GBF, the book fits well into this series, especially since governance perspectives on biodiversity remain relatively underrepresented as compared to other sustainability issues such as climate change. One of the main added values of the book is its governance perspective on transformative change. As stated earlier, such a governance lens on transformative change is relatively new, and such insights from the perspective of the earth system governance community on transformative change for biodiversity conservation and sustainable development more broadly are urgently needed. Such a governance angle implies a multiactor perspective throughout the book, acknowledging and critically reflecting on the role of governmental, market and civil society actors in governing biodiversity. With this, the book builds on earlier contributions to the series, especially Reference Linnér and WibeckLinnér and Wibeck (2019), by further delving into the governance of transformative change.

The idea for a book on “transforming biodiversity governance” was born in discussions among members of the Rethinking Biodiversity Governance network, an informal network of academics and practitioners interested in biodiversity governance. Because our community includes both academics and policymakers, we have aimed to develop a book that is academic but policy-relevant.

1.5 Overview of the Book

The book is organized into five sections. Following this introductory part, Part II focuses on unpacking the central concepts of the book. Parts III and IV respectively focus on cross-cutting issues and key contexts that are vital to biodiversity conservation and its sustainable and equitable use. Part V strategically reflects on the insights developed throughout the book.

All chapters are built around broad, reflexive literature reviews. The chapters are focused on possible solutions, based on a critical reflection on past policies and practices. The book explicitly incorporates insights from different ontological, epistemological and theoretical perspectives to ensure coverage of various relevant literatures. The chapters include local, national, regional, global or multilevel lenses. All chapters have been peer reviewed by two reviewers.

In answering the research questions, each chapter focuses on one or multiple underlying causes of biodiversity loss, and/or one or more approaches to transformative governance. Each chapter includes an introduction of the issue (problem, main underlying causes), existing attempts to address the underlying causes of biodiversity loss, governance approach(es) and ways forward. In this way, the book provides rich insights into the diversity of current thinking on transforming biodiversity governance.

After this introductory chapter, Chapter 2 illustrates how nature has been defined in the context of shifts in biodiversity governance in recent decades, and how different stakeholders have engaged with these concepts. The chapter aims to show that nature is defined, and cannot be taken for granted as one objectifiable concept. The concepts of biodiversity, wilderness, intrinsic value and protected areas are introduced, and the concept of landscape is illustrated regarding ecosystem services and biocultural diversity. Furthermore, instrumental and relational values of nature are discussed. Conferring nature with legal rights (rights of nature) is introduced as a hybrid form of biodiversity governance merging Western and non-Western ontologies and definitions of nature. The chapter also discusses the importance of scenarios for nature in order to develop alternative pathways grounded on value pluralism. It concludes that defining nature is far from an objective and conflict-free exercise. Instead of reductionist approaches, the authors promote pluralistic approaches, highlight the importance of transparency and warn for the danger of treating concepts and approaches as truth-claims, making them less open to other perspectives.

Chapter 3 focuses on global biodiversity governance. The CBD is discussed as the main international treaty governing biodiversity. Its Post-2020 GBF aims to transform biodiversity governance to steer the necessary transformative change to halt biodiversity loss. For this undertaking, the CBD operates alongside multiple international conventions and international governmental and nongovernmental organizations at different scales that together form global biodiversity governance. The chapter presents what needs to be transformed within global biodiversity governance and discusses ways to achieve such transformation. It begins with a historical account of the evolution of global biodiversity governance. A “regime complex” lens is then used to show why biodiversity governance approaches have to intervene with sectors responsible for biodiversity loss such as agriculture, trade and development, and reflections are made on the implementation of global biodiversity law and policies. The conclusion considers how obstacles can be overcome to achieve true transformation.

Chapter 4 aims to understand why the current state of biodiversity is so fragile, despite over half a century of global conservation efforts, and develop insights for more effective ways forward. The chapter generates insights by integrating largely disconnected literatures that have sought to understand how to govern transformative change, transformations and transitions. It pays particular attention to the role of four distinct sustainability problem conceptions, namely commons, optimization, compromise and prioritization. Combining insights on transformations and transitions allows more focused attention to the generic societal underlying causes of sustainability issues and integrative governance of transitions. Through integrating problem type thinking, the chapter shows that treating biodiversity loss, and thereby ecocentric, compassionate and just sustainable development, as a priority is an essential part of transformative governance. Such prioritization radically changes governance: Governance mixes that combine instruments from all four problem conceptions will need to evolve over time for governance to become increasingly transformative.

The main aim of Chapter 5 is to discuss linkages between nature and generic health from a One Health as well as a transformative biodiversity governance perspective. The transformative governance ambitions of being integrative, inclusive, transdisciplinary, adaptive and anticipatory resonate quite well with One Health as an overarching concept for nature–health linkages. Especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, interest in One Health broadened. But what does, or can, it entail? What is the beauty of One Health in the eyes of different beholders? The chapter outlines different aspects and interpretations of One Health to illustrate both its potential and challenges. This includes integrative ambitions of including animal, human, plant and ecosystem health, as well as structural societal drivers of these “healths” and related complexity.

Chapter 6 critically discusses the role of innovative financial instruments in transformative biodiversity governance. These instruments are a subset of the broader spectrum of biodiversity finance instruments and directly mobilize financial resources for biodiversity conservation, compensate negative impacts of economic activity or manage risks of biodiversity loss. The chapter presents four general arguments: innovative financial instruments (1) conceptualize nature from an anthropocentric, mechanical and managerial perspective; (2) emphasize monetary values at the expense of others; (3) frame uncertainty as a manageable risk and (4) integrate different sectors, levels and stakeholders without challenging the foundations of existing systems and relations. These arguments underscore the limitations of innovative financial instruments in most dimensions of transformative governance (particularly inclusive and transdisciplinary governance), while offering some opportunities in others (i.e. integrative governance). The chapter’s assessment of these instruments critically challenges their capacity for fostering transformative governance, although they may be useful as component of broader and more fundamental developments.

Chapter 7 discusses the relationships between biodiversity and emerging technologies. Emerging technologies have potentially far-reaching impacts on the conservation and sustainable and equitable use of biodiversity. Simultaneously, biodiversity increasingly serves as an input for novel technological applications. The chapter assesses the relationship between the CBD regime and the governance of three sets of emerging technologies: climate-related geoengineering (carbon dioxide removal and solar radiation modification), synthetic biology (including gene drives) as well as bioinformatics and digital sequence information. It presents an overview of relevant applications of these technologies, including potential positive and negative impacts on the CBD’s objectives; explores the state of relevant deliberations under the CBD and other intergovernmental fora, including normative gaps and opportunities for action; and assesses the extent to which they could support transformative governance of technologies and biodiversity from the vantage points of adaptiveness, integration, anticipation, inclusion and transdisciplinarity.

Chapter 8 assesses how principles of justice and equity should be interpreted and upheld in efforts to pursue transformative biodiversity governance. Justice and equity are not only core social values but also key to addressing biodiversity decline. The chapter argues that the depth, scale and urgency of transformative change required demand heightened attention to both existing injustices and the advancement of multiple dimensions of justice, including procedural justice, recognition and distributive justice. It addresses questions of justice arising at three key stages of biodiversity governance: decision-making processes, resource mobilization and allocation, and implementation. Building on understandings of transformative governance as being both inclusive and integrative, the chapter highlights potential synergies and trade-offs between environmental sustainability and justice. The findings converge on the need for a “just transformation” of biodiversity governance.

Chapter 9 argues that transformative biodiversity governance requires mainstreaming the interests of the individual animal. Applying an integrative governance perspective, the chapter brings together debates from animal and biodiversity governance systems through a literature review and document analysis on animal rights and welfare, rights of nature (Earth jurisprudence), One Health and One Welfare, and compassionate conservation. It shows that, especially through rights-based approaches, moral and legal communities are expanding beyond humans to include nature and nonhuman animals. Since Earth jurisprudence does not explicitly recognize the interests of the individual animal, and the animal rights discourse does not include flora or natural objects, both approaches are necessary to complete the shift from dominant anthropocentric ontologies to a more holistic and ecocentric approach that includes recognition of individual animals. Such a shift is vital to enact the transformative change required for a biodiversity governance model in which justice between species is integral.

Chapter 10 focuses on bioprospecting. While it has potential to create high-value products in the pharmaceutical, cosmetics, food and other life science-based industries, bioprospecting the deep oceans beyond national jurisdictions is cost-intensive and receives significant state funding. Moreover, it is dominated by multinational companies from a few developed nations. This has spurred debate on whether some of the benefits derived from these genetic resources should be more equitably shared among the international community. Legal regulation of the use of genetic material from areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ) is currently subject to negotiation in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Discussions are fueled by controversies over the principles of the freedom of the high seas versus principles stemming from the access and benefit-sharing regime that governs the use of genetic resources. This chapter examines variation in corporative response to the proposed regulations, thereby filling a gap, as commercial actors in bioprospecting are rarely studied academically.

Chapter 11 examines the need for transformative change in the governance of protected and conserved areas, with a focus on the Post-2020 GBF under the CBD. While progress has been made in designating sites under Aichi Target 11, this has not resulted in equitably and effectively managed or ecologically representative sites. Drawing from three case studies, the chapter proposes a new approach based on biodiversity and equity outcomes that incorporates integrative, inclusive and adaptive elements of transformative governance. Governance needs to go beyond including IPLC to focus on rights-based approaches and equity considerations. Adopting this type of approach at the global level will require a common understanding of biodiversity outcomes, redirecting of finance from high- to low-income countries, and complementary efforts by high-income countries to address the underlying causes of biodiversity loss by adopting sustainable trade and consumption patterns.

Increasingly heated debates concerning species extinction, climate change and global socioeconomic inequality reflect an urgent need to transform biodiversity governance. A central question in these debates is whether fundamental transformation can be achieved within mainstream institutional and societal structures. Chapter 12 argues that it cannot. Indeed, mainstream neoprotectionist and natural capital governance paradigms that do not sufficiently address structural issues, including an increase of authoritarian politics, might even set us back. The way out, the chapter contends, is to combine radical reformism with a vision for structural transformation that directly challenges neoliberal political economy and its newfound turn to authoritarianism. Convivial conservation is a recent paradigm that promises just this. The chapter reviews convivial conservation as a vision, politics and set of governance mechanisms that move biodiversity governance beyond market mechanisms and protected areas. It further introduces the concept of “biodiversity impact chains” as one potential way to operationalize its transformative potential.

Current forms of agriculture are a major driver of biodiversity loss. Prevailing threats to biodiversity in agricultural landscapes are linked to management choices and habitat conversion. Biodiversity conservation in agricultural landscapes requires both setting aside valuable ecological areas (land-sparing) and radically changing agricultural practices (land-sharing). Chapter 13 employs the concept of biodiversity policy integration (BPI) to assess to what extent biodiversity is integrated into agricultural governance in developed and developing countries. The chapter finds that biodiversity policies are predominantly “add-on” and neither directly address biodiversity-threatening agricultural practices, nor specifically support more “nature-inclusive” agriculture. Thus, existing knowledge of biodiversity-sound agriculture is not reflected in dominant agricultural policies and practices. The chapter argues that political will can target the following leverage points to transform existing governance structures: (a) working toward a clear vision for sustainable agriculture; (b) building social capital; (c) integrating private sector initiatives; and (d) better integrating knowledge and learning in policy development and implementation.

Chapter 14 explores how the governance of urban nature is transforming in response to the increasing urgency of this agenda, and the extent to which it is in turn becoming transformative for the governance of biodiversity. The chapter finds that urban biodiversity governance is being transformed both in terms of its focus (moving from only a concern with reducing the threat of cities to biodiversity to also realizing their benefits) and in terms of the forms that governance is taking (through the growth of governance experimentation in cities and the growth in transnational governance networks). Nonetheless, there remain significant challenges to address in terms of how matters of biodiversity can become mainstream to urban development and how cities come to be positioned within biodiversity governance, which forms of urban nature come to count in the pursuit of urban sustainability and how issues of social inclusion and justice can be addressed.

Chapter 15 analyzes the major underlying causes of marine biodiversity loss and focuses specifically on the lessons learned for transformative ocean governance in the context of area-based management and spatial planning. It illustrates the broad recognition of the vital need for integrative, anticipatory, adaptive and inclusive governance of ocean biodiversity. Fundamentally, however, the chapter underscores the need for transdisciplinary governance in supporting integration, inclusion and learning in ocean affairs for transformative change. An alternative governance approach is proposed: Building on the interdependencies between human rights and marine biodiversity, a broader approach to fair and equitable benefit-sharing can support institutionalized shifts toward more transdisciplinary, integrative, inclusive and adaptive governance for the ocean at different scales.

Chapter 16 wraps up the edited volume. Based on the contributions of the different chapters, it takes a next step in operationalizing the key concepts of the book, namely transformative change, transformative governance, transformations and transitions. It then discusses opportunities and challenges for transformative biodiversity governance in the context of the Post-2020 GBF and its implementation. The GBF has the ambition to develop a transformative framework for the next stage in biodiversity governance. This requires prioritizing ecological, justice and equity concerns in addressing the underlying causes of biodiversity loss and developing governance arrangements to make this happen. We apply the book’s transformative governance framework to further harness the transformative potential of a number of governance arrangements put forward for the GBF. We argue that in this manner, transformative biodiversity governance can contribute to ecocentric, compassionate and just sustainable development.