1 Introduction

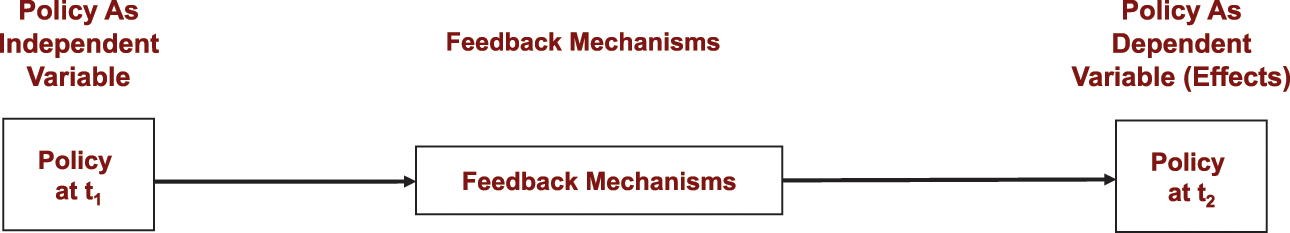

The claim that existing policies shape the politics of policy development is hardly new and can be traced back to the work of scholars such as Reference SchattschneiderE. E. Schattschneider (1935: 288), who, more than eighty-five years ago, famously wrote that “new policies create a new politics.” Yet the concept of policy feedback that is widely used today to explore how existing policies shape politics and policy development over time is much more recent (Reference OrloffOrloff 1993; Reference PiersonPierson 1993; Reference SkocpolSkocpol 1992; Reference Weir, Orloff and SkocpolWeir, Orloff, and Skocpol 1988). What is specific about policy feedback is its temporal emphasis on policy development and its claim, in policymaking and politics more generally, that policies are not only effects but potential causes (Reference PiersonPierson 1993, Reference Pierson2004a). Over the last three decades, in exploring new empirical and theoretical grounds, the scholarship on policy feedback expanded to focus on the variety of causal mechanisms through which existing policies shape politics and policymaking over time (Reference Béland and SchlagerBéland and Schlager 2019a, Reference Béland and Schlager2019b; Reference CampbellCampbell 2003, Reference Campbell2012; Reference Jacobs and WeaverJacobs and Weaver 2015; Reference MettlerMettler 2005; Reference Mettler, SoRelle, Sabatier and WeibleMettler and SoRelle 2018; Reference PatashnikPatashnik 2008; Reference Patashnik and ZelizerPatashnik and Zelizer 2013; Reference WeaverWeaver 2010).

The main objective of this Element is to review and assess early and more recent contributions to the literature on policy feedback to clarify the meaning of this concept and its contribution to both political science and policy studies. This Element focuses on three related bodies of literature, which cover the most central aspects of the scholarship on policy feedback. Each of the following three main sections features a critical literature review and, in the case of Sections 3 and 4, an agenda for future research on the topics covered.

Section 2 reviews the early literature on policy feedback. As suggested, the concept of policy feedback emerged within historical institutionalism (HI), which has made a strong contribution to both political science and policy studies. Simultaneously, while the section shows that turning to HI is essential to understand the genesis of policy feedback as a concept, it also suggests that other traditions such as punctuated equilibrium (PE) theory and the social construction of target populations have also contributed directly to the field.

Section 3 discusses the evolving literature on policy feedback and the political behaviors and attitudes of mass publics. The section suggests that public policies can influence the behaviors and attitudes of members of the public, with effects on subsequent politics, because (1) they heighten or diminish levels of political participation among those affected, increasing or diminishing political inequality within or between politically relevant groups, and (2) they affect attitudes toward the role of government (sometimes versus the market), support for incumbents and parties, and perceptions of program recipients. These feedback effects vary in their strength and durability.

Section 4 focuses on how policy feedback affects policy change. As suggested, policy feedback mechanisms that affect prospects for policy change are of several distinct types, including economic returns, sociopolitical mechanisms, informational and interpretive mechanisms, fiscal mechanisms, and state capacity mechanisms. Within each of these categories, both self-reinforcing and self-undermining mechanisms exist. Simultaneously, these policy feedback mechanisms can operate in both strong and weak forms, with their impact conditional both on the exact nature of those feedbacks and on how they interact with “exogenous” contextual factors that vary widely across political systems and policy sectors.

The final section turns our attention to the potential contribution of policy feedback research to the world of practice, with a particular focus on policy design. As argued, each of the policy feedback mechanisms outlined in Section 4 can be used by both those seeking to reinforce and those seeking to undermine the status quo to advance their interests. Moreover, efforts to use feedback mechanisms to achieve policy objectives are subject to several constraints, notably the necessity of compromise to achieve policy change and the difficulty of anticipating the effects of some policies. Some strategies, such as “frontloading” policy benefits to secure public support, are likely to be employed by proponents of changes to current policy.

2 Theoretical Perspectives on Policy Feedback

2.1 Historical Institutionalism and the Concept of Policy Feedback

The concept of policy feedback emerged in the 1980s within and at the same time as HI, a broad approach to politics and public policy that is distinct from two other contemporary types of new institutionalism: organizational institutionalism, which focuses on cultural legitimacy and the institutional development of organizations, and rational-choice institutionalism, which focuses on institutional constraints on individual choice (Reference CampbellCampbell 2004; Reference Hall and TaylorHall and Taylor 1996; on new institutionalism, see Reference CampbellCampbell 2004; Reference LecoursLecours 2005; Reference PetersPeters 2011). As the label implies, HI focuses in large part on the evolution and impact of institutional processes over time. It is particularly attentive to the temporal sequence of institutional processes as they unfold over time (Reference PiersonPierson 2004b).

Intellectually, HI is closely related to the idea of Bringing the State Back In, the title of a widely cited edited volume published in the mid-1980s (Reference Evans, Rueschemeyer and SkocpolEvans, Rueschemeyer, and Skocpol 1985). Developed in reaction against behavioralist and structuralist approaches that focus on systems theory and class power, respectively, this idea is closely related to the claim that states have a certain level of autonomy vis-à-vis economic and social forces located outside of it (e.g., Reference CampbellCampbell 2004; Reference Fioretos, Falleti and SheingateFioretos, Falleti, and Sheingate 2016; Reference ImmergutImmergut 1998; Reference Steinmo, Thelen and LongstrethSteinmo, Thelen, and Longstreth 1992).

Historical institutionalism emerged in the United States, a country where systems theory and other behavioral approaches to politics had somewhat marginalized the study of the state (Reference Evans, Rueschemeyer and SkocpolEvans, Rueschemeyer, and Skocpol 1985). Yet drawing on existing US scholarship on the state and public policy helped historical institutionalists bring the state back in. The work of Reference HecloHugh Heclo (1974), who emphasized the role of bureaucrats and policy learning in the development of public policies, proved especially influential. Reference DerthickMartha Derthick’s (1979) study of Social Security development in the United States drew attention to the role of bureaucrats in defining and expanding the program, a practice closely related to state autonomy. Reference SkowronekStephen Skowronek’s (1982) book Building a New American State, which documented the creation of an administrative state in the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, moved the concept of the state to the center of what became known as American Political Development (APD), a historically minded scholarship on politics and public policy closely related to what would become HI (on APD, see Reference Orren and SkowronekOrren and Skowronek 2004; Reference Valelly, Mettler and LiebermanVallely, Mettler, and Lieberman 2016).

While born in the United States, HI strongly emphasizes the importance of comparative and international research, stressing how institutions – which are broadly defined as norms and rules that typically include public policies themselves – vary from country to country, which makes comparative research highly relevant. Even some of the early HI studies focusing on the United States have a comparative angle, in part because their objective is to explain what is specific to the United States (e.g., Reference AmentaAmenta 1998; Reference OrloffOrloff 1993; Reference SkocpolSkocpol 1992; Reference WeirWeir 1992). Early HI scholarship focused primarily on fiscal and social policy (Reference ImmergutImmergut 1992; Reference OrloffOrloff 1993; Reference PiersonPierson 1994; Reference Pierson, Weaver, Kent and Rockman WeaverPierson and Weaver 1993; Reference SteinmoSteinmo 1996).

To understand the status of policy feedback within both HI and political analysis more broadly, we can turn to the distinction between the synchronic and the diachronic effects of institutions (Reference Jacobs, Fioretos, Falleti and SheingateJacobs 2016: 341). First, according to Reference Jacobs, Fioretos, Falleti and SheingateAlan Jacobs (2016: 341),

A synchronic institutional argument identifies a short-run effect of prevailing political-institutional arrangements on the relative political influence of political actors. Arguments about synchronic institutional effects … take actors’ political capacities and policy demands as given and then assess the ways in which the “rules of the game” favor or disadvantage particular types of actors and demands over others.

An early example of synchronic analysis within HI is the work of Reference ImmergutEllen Immergut (1992) on “veto points.” Studying the politics of health care reform in three European countries, Reference ImmergutImmergut (1992) suggested that, compared to France and Sweden, the institutional configuration of the Swiss political system, especially federalism and direct democracy, created more institutional opportunities for physicians in Switzerland to successfully oppose health care reforms that they opposed. In general, veto points concern how formal “political institutions shape (but do not determine) political conflict by providing interest groups with varying opportunities to veto policy” (Reference KayKay 1999: 406). This is clearly an example of synchronic analysis that stresses how stable “rules of the game” such as federalism and direct democracy shape the constraints and opportunities of political actors involved in the policy process. This type of synchronic analysis about how formal political institutions influence policy behavior has been applied to different policy areas (e.g., Reference Bonoli and PiersonBonoli 2001; Reference Immergut, Anderson and SchulzeImmergut, Anderson, and Schulze 2007; Reference TsebelisTsebelis 2002).

In contrast, Reference Jacobs, Fioretos, Falleti and SheingateJacobs (2016: 344) draws our attention to diachronic factors and processes in political and policy analysis. “Central to diachronic institutional analysis is a fundamentally historical analytical move: the examination of how political structures have, over time, shaped the political capacities and the policy demands that actors bring to the political battlefield” (Reference Jacobs, Fioretos, Falleti and SheingateJacobs 2016: 344). Just as the concept of “veto points” is an example of synchronic institutional analysis, policy feedback is an example of diachronic institutional analysis (Reference Jacobs, Fioretos, Falleti and SheingateJacobs 2016: 345). For HI, policy transforms policies into institutions that have much explanatory power in and of themselves. As an exploratory mechanism, therefore, policy feedback is about the diachronic (temporal) political effects of policies, which are no longer seen only as the effects of politics but also as a potential cause of it, over time (Reference PiersonPierson 1993).

The claim that existing policies can shape politics and policymaking antedates the advent of the concept of policy feedback, including Reference HecloHeclo’s (1974) abovementioned work on policy learning. Policy learning suggests that existing policies affect the ways in which political actors perceive potential policy alternatives. This discussion about policy learning leads the HI scholar Reference OrloffAnn Shola Orloff (1993: 89), when introducing the concept of policy feedback, to quote Reference HecloHeclo (1974: 315): “What is normally considered the dependent variable (policy output) is also an independent variable … Policy inevitably builds on policy, either in moving forward what has been inherited, or amending it, or repudiating it.” This quote not only points once more to the shift from policy as an effect to policy as a cause (Reference PiersonPierson 1993) but also suggests that the institutional effects of existing policies over time can lead to both self-reinforcing and self-undermining processes, depending on the context (Reference Jacobs and WeaverJacobs and Weaver 2015). In other words, the development of these policies is not always about path dependence, which generally refers to how institutions reproduce themselves over time in a specific direction that becomes harder and harder to change as these institutions mature (Pierson 2000). Yet, as we will discuss more systematically in Section 4, most of the scholarship on policy feedback has focused on self-reinforcing rather than self-undermining mechanisms. Thus, the focus has been much more on how policy institutions can foster continuity rather than path-departing change (Reference Jacobs and WeaverJacobs and Weaver 2015). This situation is reflected in the literature review provided in the present section, which focuses primarily on self-reinforcing feedback effects.

Within the HI literature, the term “policy feedback” first appeared in a volume titled The Politics of Social Policy in the United States coedited by Reference Weir, Orloff and SkocpolMargaret Weir, Ann Shola Orloff, and Theda Skocpol (1988). Yet this volume does not explore policy feedback in a systematic manner, something that will only be done a few years later (Reference OrloffOrloff 1993; Reference PiersonPierson 1993, Reference Pierson1994; Reference SkocpolSkocpol 1992). Taking a closer look at some of these seminal publications from the early to mid 1990s is appropriate because it allows us to illustrate three focal points of the early policy feedback literature, which are explicitly discussed and theorized in it: state capacities, interest groups, and lock-in effects (Reference PiersonPierson 1993; Reference SkocpolSkocpol 1992).

2.1.1 State Capacities

In Protecting Soldiers and Mothers, Reference SkocpolSkocpol (1992: 58) explains how policy feedback can take the form of an expansion of state capacities (on this issue, see also Reference OrloffOrloff 1993: 90). This is the case because, as they are being implemented, “policies transform or expand the capacities of the state,” while changing “the administrative possibilities for official initiatives in the future, and affect later prospects for policy implementation” (Reference SkocpolSkocpol 1992: 58). According to Reference SkocpolSkocpol (1992: 59), a policy can be understood as successful if it leads to an expansion of the “state capacities that can promote its future development, and especially if it stimulates expansion.” Here, the idea is that newly established policies can contribute to state-building in a way that, through self-reinforcing processes, promotes future policy expansion.

In Protecting Soldiers and Mothers, Reference SkocpolSkocpol (1992) illustrates this type of policy feedback with the development of the Bureau of Pensions, which was tasked with administering benefits for Union veterans in the aftermath of the US Civil War (1861–5). Because of the gradual expansion of these benefits, Reference SkocpolSkocpol (1992: 58) suggests, “the Bureau of Pensions became one of the largest and most active agencies of the federal government.” The development of Civil War pensions increased state capacities while creating a bureaucratic lobby within the federal government that supported the expansion of the program over time. In the end, however, the relationship between partisan patronage and Civil War pensions weakened support for them and even political momentum for the creation of a broader system of old-age pensions in the United States before the New Deal (Reference SkocpolSkocpol 1992).

An even more striking case of how policy feedback can increase state capacities and stimulate the formation of bureaucratic lobbies that support the expansion of existing policies is the case of US Social Security, which Reference DerthickDerthick (1979) documented long before the concept of policy feedback emerged as an analytical concept. Later scholars have further documented policy feedback related to state-building in the case of Social Security (Reference BélandBéland 2005). Enacted in 1935, Social Security is an earnings-related pension program operated by the federal government. Soon the bureaucrats in charge of the management of Social Security emerged as knowledgeable and skillful allies of the program, which they protected against cutbacks during World War II, when the program faced much political opposition from both within and outside the federal government, at a time when the relatively new program had yet to build a strong constituency of beneficiaries (Reference CatesCates 1983; Reference DerthickDerthick 1979). Later, during the post–World War II era, bureaucrats and political appointees operating within the Social Security Administration (SSA) promoted the expansion of the program by framing the agenda of the regularly held advisory councils tasked to evaluate and make recommendations about the then growing federal social insurance program (Reference DerthickDerthick 1979). Over time, SSA officials lobbied Congress and presidents in support of Social Security expansion and the enactment of new social programs such as Medicare, which was adopted in 1965 (Reference BerkowitzBerkowitz 2003; Reference DerthickDerthick 1979). Other factors also contributed to the expansion of Social Security and the federal welfare state in the post–World War II era, but the state capacities and internal lobbying power of SSA, itself a by-product of Social Security development, played a major role in the politics of social policy in the United States (Reference BélandBéland 2005; Reference DerthickDerthick 1979).

2.1.2 Interest Groups

The second type of policy feedback discussed in Protecting Soldiers and Mothers is about how existing public policies can shape the “social identities, goals, and capabilities of groups that subsequently struggle or ally in politics” (Reference SkocpolSkocpol 1992: 58). This type of policy feedback concerns the impact of existing policies on the development over time of interest groups that have a stake in the policy process (Reference PiersonPierson 1993: 598–605). As Reference SkocpolSkocpol (1992: 59) puts it, “public social or economic measures may have the effect of stimulating brand-new social identities and political capacities” that may mobilize to preserve existing policies.

In Protecting Soldiers and Mothers, Reference SkocpolSkocpol (1992: 59) shows how the development of Civil War pensions fostered the emergence of interest group organizations organically tied to these public policies. The key organization was the Grand Army of the Republic, the largest organization representing Union veterans. In her analysis, Reference SkocpolSkocpol (1992: 111) suggests that the expansion of Civil War pensions over time stimulated an increase in the membership of the Grand Army of the Republic, which, in turn, “intensified the interest” of this organization “in pension legislation and administration.” This feedback loop led the Grand Army of the Republic to “set up a Washington-based Pensions Committee to lobby Congress and the Pension Bureau” (Reference SkocpolSkocpol 1992: 111).

More generally, the work of Reference SkocpolSkocpol (1992) and others (Reference PiersonPierson 1993) suggests that the nature of existing public policies shapes the formation of interest groups and their political mobilization over these policies and within the policy arena. Clearly massive economic and social programs that allocate benefits to large segments of the population are more likely to stimulate the emergence of large and powerful constituencies associated with important interest group organizations that are likely to get involved in the debates over the future of these programs. Conversely, more targeted programs might generate weaker constituencies and related interest groups that have less political clout when the time comes to discuss the future of these programs (Reference PiersonPierson 1994).

These general remarks are illustrated by the HI scholarship on US social policy concerning the contrast between social assistance benefits directed at “dependent” populations and social insurance benefits directed at “advantaged” populations. For instance, Reference SkocpolSkocpol (1990) wrote about the political weakness of social assistance programs such as Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), which would end in 1996 as a consequence of the controversial federal “welfare reform” (Reference WeaverWeaver 2000). For Reference SkocpolSkocpol (1990), programs for the poor such as AFDC are “poor programs” that should be replaced by measures offering universal coverage that create broader constituencies and, consequently, more resilient social policies in the long run. Although evidence suggests that some targeted programs such as US Medicaid, which provides health insurance to disadvantaged families and citizens, can grow to generate broader political support over time (Reference HowardHoward 2007), massive social insurance programs that create large constituencies can prove more resilient in the longer term under certain conditions. For instance, this is likely to be the case when these programs generate powerful third-party allies such as governors. The case of the US Medicaid program for low-income people (Reference RoseRose 2013) suggests that even programs with weak beneficiaries can become resilient over time if they generate strong political allies. Large social insurance programs are especially likely to become resilient when they target politically “advantaged” groups like older people, as is the case with US Social Security (Reference CampbellCampbell 2003; Reference PiersonPierson 1993). The example of the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP), one of the most powerful interest groups in the United States, illustrates this reality; this interest group organization expanded at the same time as Social Security, before getting involved in the politics of the Social Security reform (on the AARP, see Reference LynchLynch 2011). Policy feedback can also shape concrete interest group organizations over time, a topic studied by Reference GossKristin Goss (2012) in her book The Paradox of Gender Equality: How American Women’s Groups Gained and Lost Their Public Voice. In this qualitative analysis of the collective mobilization of women in the United States over more than a century, Reference GossGoss (2012: 18) looks at the impact of policy feedback on concrete social movement organizations, an approach that allows her to explore “how different types of feedback effects interact to affect the scope and nature of groups’ policy engagements.” Reference GossGoss (2012: 184) demonstrates how policies created in the 1960s shaped the collective action of women in the United States by offering “tangible antidiscrimination protections that women’s groups rallied to defend and expand” as well as “resources (networks, conferences, money) to support women’s organizing.”

2.1.3 Lock-In Effects

Within the HI tradition, the most widely cited publication on policy feedback is Reference PiersonPaul Pierson’s (1993) article “When Effect Becomes Cause: Policy Feedback and Political Change.” Although it appeared only a year after Protecting Soldiers and Mothers (Reference SkocpolSkocpol 1992), one of the books Pierson engaged with, this review essay provided a much more systematic take on policy feedback than anything that had been published on the topic before. In his article, Reference PiersonPierson (1993) explored issues such as the cognitive side of policy feedback associated with policy learning and the potential influence of existing policies on mass politics, thus anticipating what would become a central avenue for policy feedback research in the years and decades to come.

Another key contribution of Pierson’s seminal article was to introduce the concept of “lock-in effects” to the policy feedback literature. Drawing on a recently published book by the economist Reference NorthDouglass North (1990), Reference PiersonPierson (1993: 608) showed how

Policies may create incentives that encourage the emergence of elaborate social and economic networks, greatly increasing the cost of adopting once-possible alternatives and inhibiting exit from a current policy path. Individuals make important commitments in response to certain types of government action. These commitments, in turn, may vastly increase the disruption caused by new policies, effectively “locking in” previous decisions.

Reference PiersonPierson (1994) applied the concept of policy feedback as lock-in effects in his book Dismantling the Welfare State? Reagan, Thatcher, and the Politics of Retrenchment. In this influential book, lock-in effects are especially central to the discussion about pensions reform, with reference to US Social Security. As Reference PiersonPierson (1994: 172) suggests in his analysis of lock-in effects, “sunk costs resulting from previous decisions in pension policy created lock-in effects that greatly constrained Reagan’s options on Social Security.”

2.1.4 The Multiple Faces of Policy Feedback

Over time, HI generated other perspectives on policy feedback that built on the early scholarship discussed in Sections 2.1–2.1.3 to explore the multifaceted nature of how existing policies can shape the politics of public policy (Reference BélandBéland 2010; Reference Béland and SchlagerBéland and Schlager 2019b). One of these approaches concerns the claim that, just like public policies, state-regulated private social benefits can shape politics over time. Particularly influential here is the work of Reference HackerJacob Hacker (2002) on how, in the United States, the development of private health and pension benefits has led to the emergence of a “divided welfare state” (the title of his book), in which feedback effects from both public and private social benefits are closely intertwined in both their social functions and the political effects they generate over time. Therefore, it is possible to argue that private benefits “may impact political mobilisation and public expectations in much the same way that widely distributed public benefits do, creating strong political incentives for the maintenance or encouragement of existing private networks of social provision” (Reference Béland and HackerBéland and Hacker 2004: 46). The example of health care in the United States perfectly illustrates this claim, as both public policies such as Medicaid and Medicare and private institutions such as health insurance have shaped the politics of reform, including the enactment in 2010 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) (Reference Jacobs and WeaverJacobs and Weaver 2015). More generally, even when it does not explicitly refer to the concept of policy feedback, the extensive literature on welfare state development demonstrates that the private side of policies can shape and constrain public policy reform over time (Reference Béland and GranBéland and Gran 2008; Reference Esping-AndersenEsping-Andersen 1990; Reference HowardHoward 1997; Reference KleinKlein 2003).

Another perspective available in the HI literature is the less developed but promising concept of “ideational policy feedback” (Reference LynchLynch 2006: 199). This concept refers to how specific ideas and symbols embedded in existing policy institutions can shape the politics of policy reform over time (Reference BélandBéland 2010). For instance, in a book on US social policy, Reference SteenslandBrian Steensland (2008) argued that the negatively connotated term “welfare” embedded in US social assistance policies contributed to reform failure in this policy area during the 1970s. This was the case because new reform proposals were seen in the mirror of the unpopular and controversial idea of “welfare,” which reduced support for them (Reference SteenslandSteensland 2008). As Reference SteenslandSteensland (2008: 10) suggests, his case study stresses the role of “interpretative feedback mechanisms,” which contrast with the “resource/incentive dimension of policy feedback processes” associated with lock-in effects (for a recent discussion of ideational policy feedback, see Reference Béland and SchlagerBéland and Schlager 2019b).

For many of the HI scholars cited so far, feedback effects from existing policies appeared as only one type of institutional process among others worth studying to explain policy development. While the expansion of the literature on policy feedback suggests that it now constitutes a stand-alone theory of the policy process (Reference Mettler, SoRelle, Sabatier and WeibleMettler and SoRelle 2018), returning to the early HI literature has the advantage of reminding us how feedback effects from existing policies do not always tell the whole story about the relationship between institutional processes and policy development. This is something we should keep in mind as we turn to the growing literature on mass politics, policy feedback, and public policy, which is discussed in Section 3.

2.2 Beyond Historical Institutionalism

The discussion so far on HI and policy feedback should not obscure the contribution of other theoretical traditions to the early analysis of how existing policies shape politics and policy development. In this section, we discuss several other approaches that helped shape this analysis.

First, we should mention the work of Reference LowiTheodore Lowi (1964), a US political scientist who explained how specific types of public policy generate distinct forms of politics. His typology is based on the distinction among four types of policy: constituent, distributive, redistributive, and regulatory policies (Reference LowiLowi 1972: 300). Grounded in the assumption that “policies determine politics” (Reference LowiLowi 1972: 299), his framework articulates the relationship between these four types of policy with related types of coercion and of politics. In this context, each type of policy is associated with a particular “arena of power” (Reference LowiLowi 2009) characterized by specific political dynamics. In the United States, this work generated much critical scholarship, including the widely cited work of Reference WilsonJames Q. Wilson (1973), who revisited Lowi’s typology.

In his review essay, Reference PiersonPierson (1993: 625) explicitly mentions both Lowi and Wilson when he rejects what he calls “extremely parsimonious theory linking specific policy ‘types’ to particular political outcomes.” According to Reference PiersonPierson (1993: 625), their typologies are flawed for two reasons: “First, … individual policies may have a number of politically relevant characteristics, and these characteristics may have a multiplicity of consequences. Second, … policy feedback rarely operates in isolation from features of the broader political environment (e.g., institutional structures, the dynamics of party systems).” From this perspective at least, the emergence of policy feedback as a concept stems in part from a rejection of the abovementioned early policy typologies by Lowi and Wilson (for a critical discussion, see Reference Kellow, Colebatch and HoppeKellow 2018).

Another stream of scholarship relevant for policy feedback scholarship is the work of the US political scientists Anne Schneider and Helen Ingram on the social construction of target population theory, which stresses the relationship between policy designs and how certain groups are advantaged or disadvantaged in society. Central to the work of Reference Schneider and IngramSchneider and Ingram (1993) is a typology of target populations based on two criteria: whether these groups are weak or powerful and whether these groups are positively or negatively perceived. This leads to a fourfold typology: advantaged (powerful and positively perceived), dependents (weak but positively perceived), contenders (powerful but negatively perceived), and deviants (weak and negatively perceived). This typology helps scholars understand how policies targeting specific populations are likely to be designed, and how the social constructions embedded in concrete institutional and programmatic designs might shape later policy development through feedback effects.

The final theoretical tradition we turn to in this section, the PE approach, is especially relevant for the development of policy feedback theory, which is why it requires systematic attention. Punctuated equilibrium is associated with the work of Frank Baumgartner and Bryan Jones (see, e.g., Reference Baumgartner and JonesBaumgartner and Jones 1993/2009, Reference Baumgartner, Jones, Baumgartner and Jones2002; Reference Jones and BaumgartnerJones and Baumgartner 2005, Reference Jones and Baumgartner2012). Based initially on US experience, the PE approach argues that “Policymaking at equilibrium occurs in more or less independent subsystems, in which policies are determined by specialists located in federal agencies and interested parties and groups. These interests reach policy equilibrium, adjusting among themselves and incrementally changing policy” – a process that they acknowledge “can be profoundly undemocratic” (Reference Baumgartner and JonesBaumgartner and Jones 1993/2009: xvii–xviii). Also critical to the PE approach is the flow of information in a policy sector, as well as the limited cognitive capacity and attention spans of policymakers, which tend to filter out information deemed extraneous and policy options that do not fit with dominant policy paradigms favored by actors in the policy subsystems where policy is usually made (Reference Jones and BaumgartnerJones and Baumgartner 2005). The result, Baumgartner and Jones argue, is likely to be “periods of stability and incremental drift punctuated by large-scale policy changes” (Reference Baumgartner and JonesBaumgartner and Jones 1993/2009: xviii) that are “oftentimes disjoint, episodic and not always predictable” (Reference Jones and BaumgartnerJones and Baumgartner 2012: 1). These punctuations are frequently initiated when dissident – often newly emergent – groups manage to involve other political actors, widen the scope of political conflict (often by redefining the issue), and shift the political venues where political decisions are made. Policy crises and other “focusing events” often play an important role in these disruptions. Yet these disruptions do not always result in policy change; the interests that benefit from the status quo will use their resources to try to reassert their dominance over policymaking and limit policy changes that harm their interests.

There is much that is shared by the HI and PE perspectives on policy feedback, notably with respect to difficulties in moving away from the status quo that are generated by the unequal distribution of resources as well as shared definitions of policy problems and appropriate responses that are shared by key policy actors. Both incorporate elections and partisan ideological differences, but they are not the primary focus of either the HI or the PE perspective (Reference Jones and BaumgartnerJones and Baumgartner 2012: 5–6). There have been important dialogues between the two (see Reference PiersonPierson 2004b), but there are also important differences in the two approaches – some terminological, some merely of emphasis, and others more central to the research endeavor.

One of the most important – and most confusing – differences is in terminology. Historical institutionalists generally refer to elements of current policy that cause it to be stable or expand over time as “positive feedbacks” and those that undermine it, causing it to become less stable or expansive (e.g., lower spending on environmental enforcement or decreased eligibility and lower benefits for public income transfers), as “negative feedback.” Writers in the PE tradition, drawing on systems theory approaches, define negative feedback processes as those in which “a disturbance is met with countervailing actions, in a thermostatic-type process” that generally leads to a reversion to the status quo ante, while positive feedback involves disturbances to the status quo in which “change begets change, generating a far more powerful push for change than might have been expected” (Reference Jones and BaumgartnerJones and Baumgartner 2012: 3). To reduce terminological confusion, we will largely follow the language of Reference Jacobs and WeaverJacobs and Weaver (2015), drawing on Reference Greif and LaitinGreif and Laitin (2004), in labeling elements of the policy status quo that tend to hold it in place or lead to its expansion as “self-reinforcing” and those that tend to make current policy more subject to reduction, termination, or transformation as “self-undermining.”

Other differences between the two perspectives are more in emphasis. The PE approach gives more attention to the bounded rationality and attention limitations of policy elites. More generally, it gives greater emphasis to the micro-foundations of policymaking in information-processing practices, while HI researchers tend to focus more on macro-level forces. Historical institutionalist researchers tend to focus more on relatively slow-moving adaptions of the policy status quo (e.g., the phenomenon of policy drift), while PE researchers give more attention to short-term disruptions, which are often interpreted as exogenous shocks and being subject to fading away rather than processes that are internally generated by the policy itself and likely to be durable (Reference Jacobs and WeaverJacobs and Weaver 2015). But these differences are increasingly of terminology and degree rather than kind. Recent PE scholarship has, for example, devoted increased attention to dysfunctional elements of policies – generally referred to as “error accumulation” (Reference Jones and BaumgartnerJones and Baumgartner 2012: 8) – that are not remedied because of resistance from beneficiaries of the status quo, while HI scholarship has moved away from the concept of “lock-in” toward more nuanced views that emphasize both self-reinforcing and self-undermining aspects of policy.

In this Element, we draw on both the HI and the PE perspectives. Although our primary focus is on the HI approach, important insights from the PE approach, including the bounded rationality and limited attention of generalist policymakers, the importance of focusing events, and the potential for exogenous disruptions to existing arrangements, are incorporated elsewhere in this Element, especially in Section 4.

3 Policy Feedback and Mass Politics

Public policies affect not only the interests and capacities of states and interest groups but also behaviors and attitudes among the mass public. A burgeoning literature explores the ways in which policies can increase or decrease political participation among program clienteles and how existing policy can alter attitudes among both the targets of those policies and other members of the public (for earlier reviews, see Reference BélandBéland 2010; Reference CampbellCampbell 2012; Reference LarsenLarsen 2019; Reference Mettler, SoRelle, Sabatier and WeibleMettler and SoRelle 2014; Reference Mettler and SossMettler and Soss 2004). Analyses have been growing in scope, with new case studies both within and beyond social welfare policy, where the literature had its starting point. The examination of mass feedbacks in US politics continues, with multiple analyses of the 2010 ACA and new policy areas such as social regulation and rights. To the pioneering work using European data by Reference SvallforsSvallfors (1997, Reference Svallfors2006, Reference Svallfors2007, Reference Svallfors2010), Reference KumlinKumlin (2004), and Reference MauMau (2003, Reference Mau2004), among others, scholars have added new analyses (Reference Bol, Marco, Blais and LoewenBol et al. 2021; Reference LarsenLarsen 2018, Reference Larsen2020; Reference ShoreShore 2019, Reference Shore2020; Reference WatsonWatson 2015; Reference Zhu and LipsmeyerZhu and Lipsmeyer 2015), while work extends to new locales such as Canada (Reference GidengilGidengil 2020; Reference Soroka and WlezienSoroka and Wlezien 2004, Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010), Africa (Reference HernHern 2017; Reference MacLeanMacLean 2011), Latin America (Reference De La ODe La O 2013; Reference Di Tella, Galiani and SchargrodskyDi Tella, Galiani, and Schargrodsky 2012; Reference Manacorda, Miguel and VigoritoManacorda, Miguel, and Vigorito 2011), and Asia (Reference Im and MengIm and Meng 2016; Reference Li and WuLi and Wu 2018; Reference LuLu 2014; Reference Ricks and LaiprakobsupRicks and Laiprakobsup 2021). Scholars are developing the theory of policy feedback and mass publics with new mechanisms and new contingencies. Methodological sophistication is growing as well with the incorporation of causal models that improve inference.

In this section, we discuss early theoretical perspectives on mass policy feedback, review the major findings on feedback effects in individual-level political behavior and attitudes, examine methodological issues, and suggest new research frontiers.

3.1 Resources, Interpretive Effects, and the Social Construction of Target Populations

Two theoretical perspectives have animated much of the subsequent work on policy feedback and mass politics, suggesting that policies are not just the outcomes of political processes but also important inputs that reshape the political environment by influencing political participation and preferences among members of the public. Reference PiersonPaul Pierson (1993) hypothesized that existing policies provide politically relevant resources and convey positive or negative “interpretive” messages to publics about their place in the polity, which affect individuals’ attitudes and their propensity to participate in politics. Policies that deliver generous benefits may foster “protective constituencies” that fight against retrenchment, an example of a self-reinforcing effect (Reference PiersonPierson 1994). Working in parallel, Reference Schneider and IngramSchneider and Ingram (1993) discussed the social construction of target populations, with policies’ designs defining clienteles’ access to the privileges of social citizenship (e.g., Reference MarshallMarshall 1964). Policies for positively constructed groups such as senior citizens tend to be generous and efficiently administered, sending the message that the state perceives these groups as deserving. In contrast, policies for negatively constructed groups such as the poor or criminals are meager and capriciously administered, suggesting that the state considers them marginal members of the polity. In their original formulation, the direction of causality is unclear: Do the policies create the group constructions or do preexisting group constructions lead to differing policy designs (Reference LiebermanLieberman 1995)? Recent empirical work has attempted to overcome these challenges with causal models, as we will see in Section 3.4. Much of the work testing for feedback effects has examined individual-level behavior and attitudes; in Section 4, we examine positive and negative (self-reinforcing or self-undermining) feedbacks at the aggregate level.

3.2 Policy Feedback and Mass Behavior

Feedback studies show that the designs of public policies can increase or decrease the political participation of individuals beyond what we would predict from their education, income, and other demographic correlates of behavior. Many such studies examine the effects of social welfare programs, although recent work has branched out into additional areas such as civil rights, regulations, and criminal justice. Research has sought to uncover the mechanisms by which policies affect behavior and the aspects of program designs that generate these mechanisms. In addition, scholars have explored how policies affect different types of participation as well as participatory level and equality.

3.2.1 Factors in Political Behavior

Political participation is a function of resources, mobilization, and political engagement, factors that arise from preadult socialization and education and from experiences in institutional settings such as work, voluntary organizations, and religious organizations (Reference Verba, Schlozman and BradyVerba, Schlozman, and Brady 1995). Policy feedback theory posits that policy experiences affect these drivers of political participation, as well as additional factors that influence political behavior, including stigma, norms, loss aversion, and traceability (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Policy feedback and political participation

Resources. Policies can confer politically relevant resources such as money, skills, free time, health, and financial stability, which increase participatory capacity and facilitate democratic acts such as voting, contacting elected officials, working on campaigns, attending political meetings, participating in rallies or protests, working with others on political problems, or making political donations. In the United States, Social Security, the federal old-age pension program, enhances the political participation of older US citizens by increasing their free time through retirement and boosting their incomes (Reference CampbellCampbell 2003). The 1944 G.I. Bill increased political participation among veterans through enhanced education attainment (Reference MettlerMettler 2005). More recently, Medicaid expansion under the ACA boosted voter turnout among target groups (Reference Clinton and SancesClinton and Sances 2018; Reference HaselswerdtHaselswerdt 2017), apparently by increasing financial stability and physical and mental health, which are associated with political participation (Reference OjedaOjeda 2015; Reference Pacheco and FletcherPacheco and Fletcher 2015). In Mexico, voter turnout is higher in villages randomly selected for the rollout of a new anti-poverty cash transfer program (Reference De La ODe La O 2013).

Mobilization. Citizens are also more likely to participate in politics when asked to do so (Reference Verba, Schlozman and BradyVerba, Schlozman, and Brady 1995). In conferring an age-related social welfare benefit, Social Security in the United States created a politically identifiable group that was subsequently mobilized by interest groups and political parties (Reference CampbellCampbell 2003). State laws in the United States that mandate collective bargaining increase the political participation of teachers, apparently through union mobilization (Reference Flavin and HartneyFlavin and Hartney 2015). Under the ACA, social assistance agencies that help customers access health insurance also provide voter registration services, perhaps generating the higher voter participation found in Medicaid expansion states (Reference Clinton and SancesClinton and Sances 2018).

Engagement. Political engagement, including political information, political interest, and political efficacy, is another factor driving political participation (Reference Verba, Schlozman and BradyVerba, Schlozman, and Brady 1995). Over time, in the United States Social Security increased seniors’ interest in politics by tying their well-being to a government program while also enhancing their external political efficacy, the sense that government listens to people like them (Reference CampbellCampbell 2003). Recipients of cash welfare who learn how to navigate a complex welfare bureaucracy have heightened levels of internal political efficacy, the sense that they have the competence to negotiate the political realm (Reference SossSoss 1999). In the United States, veterans who benefited from the G.I. Bill felt “reciprocity,” an obligation to participate in civic life in return for the gift of an unexpected education, which may be a form of efficacy as well (Reference MettlerMettler 2005).

Stigmatization and Authority Relations. Not all policy effects are positive. The “interpretive effects” that send messages to program clienteles about their place in the polity (Reference PiersonPierson 1993) have often been used to explain the diminished participation rates of those receiving targeted, means-tested social welfare benefits (Reference Schneider and IngramSchneider and Ingram’s (1993) concept of a negative social construction predicts a similar outcome). Cash welfare in the United States is conferred by gatekeeping case workers whose control over benefits and capricious application of rules undermine the external political efficacy of recipients, reducing their rates of political participation (Reference SossSoss 1999). Imposing conditionality, such as work requirements, further undermines political participation, as the needed monitoring sends the message that government does not trust the recipient, as the UK case shows (Reference WatsonWatson 2015). These negative interpretive effects can be passed on through socialization: Adolescents whose families receive means-tested assistance observe low levels of parental political participation and are less likely to participate in political activities available to youth, such as contacting public officials, boycotting, and discussing political issues (Reference Barnes and HopeBarnes and Hope 2017).

Targeted programs need not send negative citizenship messages, however. Early childhood programs in the United States and Denmark that incorporate low-income or minority parents into decision-making – allowing such parents to “coproduce” a service they receive from government – enhance parents’ skills and knowledge (a resource effect) and send positive interpretive messages that society views them as “capable and valuable” (Reference Hjortskov, Andersen and JakobsenHjortskov, Andersen, and Jakobsen 2018), increasing their efficacy and civic participation (see also Reference BarnesBarnes 2020; Reference Bruch, Ferree and SossBruch, Ferree, and Soss 2010; Reference SossSoss 1999). In the United States, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which supplements the wages of low-income workers by refunding their income and payroll taxes, generates “feelings of social inclusion” with administration through the universal tax system, not the welfare bureaucracy, and with provision as a lump sum, enabling “patterns of spending and saving that are not possible during other times of the year” and that resemble those of “ordinary” citizens, providing “at least partial access to the social rights of citizenship” (Reference Sykes, Kriz, Edin and Halpern-MeekinSykes et al. 2015, 244). Although this study does not examine the political behavior of EITC recipients, feedback theory would hypothesize higher participation rates among EITC recipients than among cash welfare recipients.

Norms. The messages that public policies send may also establish norms that influence political activity. Reference McDonaghEileen McDonagh (2010) argues that public policies that “represent maternal traits” send messages about “women’s suitability as political leaders”; in nations such as the United States, where maternal traits are demonstrated only in the home, not in the state, McDonagh asserts, fewer women are elected to political office. The provision of new rights may also establish norms enhancing participation. When female student athletes were reminded in an experiment of the purpose of Title IX (to reduce gender-based disparities in US higher education, including athletics), they reported a greater propensity to act to seek equity (although the study did not examine whether such students did act; Reference Druckman, Rothschild and SharrowDruckman, Rothschild, and Sharrow 2018).

Threats and Loss Aversion. Threats to policies may animate political participation as well, given individuals’ aversion to losses over equivalent gains (Reference Kahneman and TverskyKahneman and Tversky 1979). In the United States, senior citizens responded to proposed Social Security and Medicare cuts in the 1980s and 1990s with surges in letter-writing to elected officials, the only age group to do so, which helped defeat the proposed reductions (Reference CampbellCampbell 2003), an example of the protective constituency dynamic that Pierson posited. Threats emanating from policies may also spur participation. In states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA, voter turnout was enhanced not only among Democrats who approved of the law but also among Republicans who opposed it, an apparent “policy backlash” (Reference HaselswerdtHaselswerdt 2017). Policies can impose sheer bodily threat that mobilizes as well. The parents of draft-eligible sons in the Vietnam War era were more likely to vote in the 1972 presidential election if their sons drew “losing” draft numbers (although we cannot know from voter records how these parents voted; Reference DavenportDavenport 2015). Latinos were more likely to vote in areas where the Secure Communities program rolled out, a program that heightened immigration enforcement by encouraging information sharing between federal and local law enforcement (Reference WhiteWhite 2016). Although government trust fell among Latinos in these areas (see Section 4), the program constituted a threat to families with mixed immigration status and may also have boosted turnout because of mobilization by immigration activists (Reference WhiteWhite 2016). Policies threatening Latinos in California during the 1990s (including Proposition 187, championed by the Republican governor Pete Wilson, which would have banned undocumented immigrants’ use of health care, public education, and other services) boosted Latino voters’ subsequent turnout and increased identification with the Democratic Party (Reference Bowler, Nicholson and SeguraBowler, Nicholson, and Segura 2006; Reference Pantoja, Ramirez and SeguraPantoja, Ramirez, and Segura 2001).

Traceability. Whether policies generate feedback effects may depend on their visibility and proximity (Reference GingrichGingrich 2014; Reference Soss and SchramSoss and Schram 2007). The Vietnam draft effect in the United States that Reference DavenportDavenport (2015) found was concentrated in towns with at least one casualty, increasing the visibility and salience of draft policy. Conversely, when visibility and proximity are muted – for example, when public functions are privatized, obscuring the role of government even when it still funds or regulates the programs – policy effects may not materialize (Reference Gingrich and WatsonGingrich and Watson 2016). A causal model shows that voter turnout for school board elections in the United States is lower in districts with privately operated charter schools (Reference Cook, Kogan, Lavertu and PeskowitzCook et al. 2020). The ACA provision allowing people under the age of twenty-six to remain on their parents’ health insurance did not increase voter turnout among youth in the United States, despite being popular and widely used; that parental insurance plans are private and funded by the parent may have been more salient than the government’s regulatory role in facilitating young people’s access (Reference ChattopadhyayChattopadhyay 2017).

3.2.2 Behavioral Outcomes

Extant policy feedback studies have examined a variety of behavioral outcomes, including voter turnout, vote choice (see Section 3.3 for effects on incumbent support and favorability), and individual political acts beyond voting, often finding that the provision of benefits enhances participation rates. Scholars have also examined whether program provision can counteract inequalities of participation found in many democracies. Feedback effects on collective forms of political action or nonpolitical acts such as volunteering have been examined as well.

Voter Turnout. The most common behavioral outcome examined in feedback studies is voter turnout, both because of its normative centrality to democratic politics and because of data availability. Policies such as Social Security (Reference CampbellCampbell 2003) and the G.I. Bill (Reference MettlerMettler 2005) in the United States as well as experience with public schools and clinics in Africa (Reference MacLeanMacLean 2011) are associated with greater participation; researchers attribute the participation boost to both resource and positive interpretive effects. Programs in the United States that are means-tested, such as cash welfare, or that are punitive, such as the criminal justice system, are associated with lower turnout (Reference SossSoss 1999; Reference Weaver and LermanWeaver and Lerman 2010), apparently because they send negative citizenship messages and because, in the case of the low benefits in US means-tested programs, resource effects are too small to increase turnout. The US Medicaid program is also means-tested, although analyses of its effects on turnout have produced contradictory results. Reference HaselswerdtHaselswerdt (2017) and Reference Clinton and SancesClinton and Sances (2018) – the latter using a causal model – show that Medicaid expansion during the ACA modestly increased turnout, and the economists Reference Baicker and FinkelsteinKatherine Baicker and Amy Finkelstein (2019) find that the near-randomized expansion of Medicaid carried out by the Oregon Health Insurance experiment of 2008 boosted turnout in that year’s presidential election by 7 percent, with particularly strong effects for men (18 percent increase) and in Democratic counties (10 percent increase). But these turnout increases dissipated quickly, and, outside of the ACA, Reference MichenerMichener (2018) finds that Medicaid receipt is associated with lower turnout, while the economist Reference Courtemanche, Marton and YelowitzCharles Courtemanche and colleagues (2020) find with a causal model that the collective effect of all ACA provisions intended to expand health insurance coverage (Medicaid expansion, the creation of subsidized insurance marketplaces, and various regulations) was only a small and statistically insignificant increase in voter turnout. Reference GayClaudine Gay (2012) similarly finds that the Moving to Opportunity randomized experiment, which moved low-income people out of high-poverty neighborhoods, reduced voter turnout, with some evidence that disrupted social networks were to blame. Hence, findings on means-tested programs and turnout, both associational and causal, are mixed.

Vote Choice. Policies conferring benefits can result in greater electoral support for incumbent governments. A causal study of state EITCs finds that governors are rewarded electorally for implementing an EITC program, with the largest effects for Republican governors and in counties with many benefiting voters, although the effects dissipate over time (Reference Rendleman and YoderRendleman and Yoder 2021). The implementation of an EITC in Italy similarly benefited incumbents electorally (Reference VannutelliVannutelli 2019). A causal analysis shows that a Romanian government program giving poor families coupons for computer purchase increased support for the incumbent governing coalition (Reference Pop-Eleches and Pop-ElechesPop-Eleches and Pop-Eleches 2012), while the Reference De La ODe La O (2013) causal study of the Progresa conditional cash transfer program in Mexico found both greater turnout and greater support for incumbents in villages with longer exposure to the program.

Political Activity beyond Voting. Some studies examine policy feedback effects for other political acts. The development of Social Security over time increased US seniors’ rates of contacting elected officials and of donating to and working on political campaigns (Reference CampbellCampbell 2003). Program receipt can heighten rates of “civic participation,” such as working with others in organized groups (e.g., Reference MettlerMettler 2005). Farmers receiving payments from the US Department of Agriculture are more likely than other agricultural producers to run for office (Reference Simonovits, Malhotra, Ye Lee and HealySimonovits et al. 2021).

Equalizing Effects. In many democracies, political behavior is stratified by income and education. Redistributive public policies can offset this effect by enhancing resources and other politically relevant factors for the less privileged. Because in the United States Social Security constitutes a higher share of poorer seniors’ incomes, they are more likely to vote, contact elected officials, and make campaign contributions with the program in mind than are higher-income seniors, making seniors’ overall political participation less unequal than it would otherwise be (Reference CampbellCampbell 2003). In that country, the educational benefits of the G.I. Bill had a curvilinear effect, boosting the civic participation of veterans from middle-income backgrounds more than those from lower-income families (for whom the resource boost was insufficient to spur great participation) or higher-income families (who would have enjoyed higher educational attainment anyway; Reference MettlerMettler 2005). The participatory effects that Reference MacLeanMacLean (2011) found in Africa are also offsetting: The most impoverished people in rural areas are the most likely to use public services and in turn are the most likely to participate in politics. Across European countries where greater early childhood expenditures and cash benefits increase voting among single mothers, the largest effects are for middle- and higher-income lone mothers, so these programs equalize participation between lone mothers and other demographic groups but not among such mothers (Reference ShoreShore 2020).

Behavioral Feedbacks beyond Individual-Level Political Participation. Finally, policies can affect nonpolitical participation. Across the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), government social welfare retrenchment is associated with more volunteering, a behavioral feedback outside of politics (Reference SuzukiSuzuki 2020). And policies can affect group behavior, for example in locales where government programs are inadequate. In Zambia, low levels of government service provision encourage higher levels of collective behavior in which communities organize to respond to the need left by the “gap the state left,” as opposed to individual-level feedback (Reference HernHern 2017).

3.3 Policy Feedback and Mass Attitudes

A second stream of research examines how existing policies affect attitudes among the public, both those policies’ target populations and other members of the public. The policy feedback literature argues that the designs of policies affect the drivers of attitudes, and as with studies of political behavior, research has sought to determine the mechanisms by which this effect materializes. The outcomes examined include attitudes toward programs themselves or their recipients and how policies affect attitudes toward government and toward the market.

3.3.1 Factors in Attitudes

Individuals’ attitudes toward political objects arise from preadult socialization; symbolic attachments including partisanship, ideology, and racial sentiment; group attachments; self-interest and material stakes; personal experiences; and elite framing and priming. The policy feedback literature argues that the designs and effects of public policies can also affect attitudes, either because they alter some of these factors, such as self-interest and personal experience, or because they alter the conditions that allow these factors to function, such as making more or less visible the material stakes in government activity (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Policy feedback and political attitudes

Self-Interest and Personal Experience. The resources that many public policies confer constitute a material stake that may enhance individuals’ support for a given program. Survey respondents using subsidies or gaining insurance through the Affordable Care Act are more likely to say that the law has had a favorable impact on health access (Reference Jacobs and MettlerJacobs and Mettler 2018); similarly, approval of the ACA is higher in Medicaid expansion states, with the largest increase among lower education nonsenior adults, the expansion’s target population (Reference Sances and ClintonSances and Clinton 2021). Universal policies are typically more popular than targeted ones (Reference Cook and BarrettCook and Barrett 1992), perhaps because more people see themselves as current or potential beneficiaries. A US-based survey experiment finds that support for tuition-free college falls when the benefit is targeted to low-income families relative to a universal program design (Reference BellBell 2020).

Personal policy experience may also counteract the influence of other predispositions such as party identification. In the United States, those receiving Medicare (those just over the age sixty-five eligibility threshold, compared to those just under) are more supportive of Medicare spending and the ACA, with the effect stronger among Republicans (Reference Lerman and McCabeLerman and McCabe 2017). Similarly, the gap between Republicans and Democrats in ACA favorability is smaller among those who gained insurance through an ACA marketplace compared to those with employer-based insurance (Reference McCabeMcCabe 2016).

Threats. The asymmetry of gains and losses (Reference Kahneman and TverskyKahneman and Tversky 1979) means that threats to policies, both proposed and realized, affect attitudes just as they do behaviors. In the United States, ACA approval was higher in Medicaid expansion states compared to non-expansion states but only after the 2016 election made Republicans’ repeal threats more credible (Reference Sances and ClintonSances and Clinton 2021). When reduced benefits and stricter requirements for a universal Danish educational grant were announced while the European Social Survey was in the field, those interviewed after the announcement expressed less satisfaction with government compared to those interviewed earlier, particularly among those more likely to be affected by the cuts (Reference LarsenLarsen 2018).

Proximity, Visibility, and Traceability. This last result suggests that proximity, visibility, and traceability affect the likelihood that public policies will shape attitudes. In cases where policy changes have not produced attitudinal changes, lack of proximity or visibility is usually suspected. For example, the 1996 welfare reform in the United States, which imposed time limits and work requirements on cash assistance precisely in line with public objections to the program, did not make citizens more supportive of program spending, warmer toward program recipients, or more supportive of the party that forged the reform, the Democrats (Reference Soss and SchramSoss and Schram 2007). Lack of proximity may explain the reform’s failure to induce attitudinal change: Many people do not participate in cash welfare or know someone who does.

Privatized policies may also hide the government’s role, shaping attitudinal feedbacks. Across European countries, there is less support for government spending on health care where health care is more privatized (Reference Zhu and LipsmeyerZhu and Lipsmeyer 2015). At the same time, in countries where health care is privately financed and where individuals must weigh different public or private alternatives, their personal experience matters more for their attitudes toward government; but where health care is entirely public and universal, personal experiences are divorced from perceptions of the role of government (Reference LarsenLarsen 2020).

“Interpretive” or Citizenship Messages. Reference PiersonPaul Pierson (1993) argued that policies could influence mass behaviors and attitudes not only through the resources they confer but also with the “interpretive” messages they send. Many analysts have pointed to such messages – which tell individuals how important or worthy they are in the view of the state – as the apparent mechanism linking policy designs with attitudinal outcomes, even though the data necessary to test for such mechanisms is rarely available in extant studies.

In the United States, welfare case workers’ arbitrary and capricious powers over benefits send messages to the recipients that they are unworthy, diminishing their political efficacy and leading them to view the entire government as arbitrary (Reference SossSoss 1999), while recipients of the universal Social Security program have higher efficacy than other citizens (Reference CampbellCampbell 2003). Similarly, Swedish citizens in universal programs that treat clients as empowered “customers” express greater trust in politicians, more support for increased social spending, more leftward ideological placements, and greater interpersonal trust than those experiencing income-targeted “client” programs (Reference KumlinKumlin 2004; Kumlin and Rothstein 2005). In the UK, making receipt of cash assistance conditional on working, and then monitoring recipients’ compliance, sends the even harsher message that government does not trust recipients (Reference WatsonWatson 2015).

Policies beyond the social welfare arena send interpretive messages too. An analysis combining survey data with the size and racial composition of jail inmate populations at the county level in the United States finds that, where criminal justice enforcement is more racially skewed, highly educated Black respondents are less likely to say government is responsive, have less trust in government, and become less participatory. At the same time, white respondents in areas with large Black populations and racially skewed enforcement exhibit higher trust, political interest, and nonelectoral participation. Criminal justice disparities apparently signal to Blacks that government is targeting them while signaling to whites that government is “looking out for them” (Reference MaltbyMaltby 2017: 544).

Elite Framing and Priming; Media and Party Effects. The ways in which political elites such as elected politicians and bureaucrats talk about programs and clienteles – and the considerations they prime in citizens’ minds – may affect attitudes as well. European analysts argue that existing policy regimes serve as channels of socialization and elite framing, with extant policies defining the national “moral economy,” a macro-level interpretive feedback that affects what publics support (Reference LindhLindh 2015; see also Reference MauMau 2003, Reference Mau2004; Reference SvallforsSvallfors 1997, Reference Svallfors2006, Reference Svallfors2007, Reference Svallfors2010). In the United States, studies show that citizens have certain racialized policy images in their heads, with universal programs like Social Security coded as “white” and cash welfare and many other means-tested programs coded as “Black,” in part because of elite framings (Reference WinterWinter 2006) and media portrayals (Reference GilensGilens 1999) that overrepresent those racial groups. The media may also increase the visibility of policies, increasing awareness and policy effects on attitudes above and beyond any resource effects, as studies of education reform in China (Reference LuLu 2014) and water privatization in Argentina (Reference Di Tella, Galiani and SchargrodskyDi Tella, Galiani, and Schargrodsky 2012) show.

The effects of policies on attitudes may also depend on the messenger. Reference LindhLindh (2015) finds that class differences in support for market models of welfare distribution are greater where there is more public delivery (in Nordic countries) and smaller where there is more private delivery (in Anglo-Saxon countries and Japan). The difference seems driven by the presence of unions and parties in the Nordic states, whose rhetoric emphasizes class-based politics, while such collective organizations and therefore class-based rhetoric are more muted in the other contexts.

3.3.2 Attitudinal Outcomes

Policy feedback scholars have examined a variety of attitudinal outcomes ranging from policy effects on attitudes toward programs and their recipients, toward the incumbent government that delivered the policy, or toward government in general (or toward market-based provision). Some of these effects are self-reinforcing, strengthening political support for subsequent rounds of policymaking, while some are self-undermining, undercutting support and leading to negative policy spirals. The discussion in Section 3.3.1 of factors in attitudes mentioned some attitudinal outcomes along the way; here, we cite additional studies on outcomes.

Program Support; Reinforcing and Thermostatic Effects. Policies may generate their own support, with attitudes toward programs becoming more favorable among those who benefit, as several studies of the Affordable Care Act have shown (Reference Hopkins and ParishHopkins and Parish 2019). Individuals receiving benefits from the relatively new Chinese welfare state become more likely to see the government rather than individuals as responsible for citizen well-being (Reference Im and MengIm and Meng 2016). Conversely, government spending can elicit a “thermostatic” effect, with the public responding to increased spending with preferences for cutting spending or responding to a reduction in spending with preferences for more government activity, as studies of the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada demonstrate (Reference Erikson, MacKuen and StimsonErikson, MacKuen, and Stimson 2002; Reference Soroka and WlezienSoroka and Wlezien 2004, Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010; Reference StimsonStimson 2004; Reference WlezienWlezien 1995). Thermostatic effects are stronger on issues of high salience and in unitary (rather than federal) systems and stronger for some issues in presidential rather than parliamentary systems (Reference Soroka and WlezienSoroka and Wlezien 2010).

Attitudes toward Program Recipients. Policies may also alter views about societal groups that ordinarily arise from preadult socialization or group orientations, with policies and their designs sending messages to other members of the public about the perceived worth and deservingness of public policy clienteles (Reference Schneider and IngramSchneider and Ingram 1993). In the United States, Reference BellBell’s (2020) survey experiment finds that support for tuition-free college is higher when a minimum high school grade point average is included as a requirement, apparently boosting the perceived deservingness of recipients. Also, in that country, Social Security Disability Insurance recipients, even though they are recipients of a contributory, earned social insurance program, are deemed as less deserving by experimental subjects when they are portrayed in vignettes as suffering from “harder-to-diagnose impairments” such as mood disorders (Reference Fang and HuberFang and Huber 2020).

Attitudes toward Incumbent Governments. Public policies may affect attitudes toward the government that produced the policy in question, as when satisfaction with the incumbent Danish government fell after education grant cuts were announced in the middle of the European Social Survey (Reference LarsenLarsen 2018). Conversely, support for government can rise with a policy intervention: Using survey data collected immediately before and after COVID-19 lockdowns were implemented in European countries in spring 2020, Reference Bol, Marco, Blais and LoewenBol and colleagues (2021) find that lockdowns increased satisfaction with democracy and vote intentions for the party of the incumbent prime minister or president. A causal study of a temporary anti-poverty cash transfer program in Uruguay found higher government support among recipients than among a control group, with the effect persisting after the program ended (Reference Manacorda, Miguel and VigoritoManacorda et al. 2011).

Trust in Government. The COVID-19 lockdowns that Reference Bol, Marco, Blais and LoewenBol and colleagues (2021) examined also increased trust in government. Across European countries, trust in government is greater where welfare spending is higher (Reference ShoreShore 2019). Reference Li and WuLi and Wu’s (2018) causal model shows that the rollout of a new rural pension scheme in China increased trust in both local and central government. In the reverse direction, negative policy experiences can undermine trust, as Reference MaltbyMaltby’s (2017) study of racial disparities in US criminal justice enforcement showed for Black respondents.

Issue Ownership. Related to incumbent support, policy feedbacks might affect “issue ownership,” citizens’ perceptions about which political parties are best at handling which issues (Reference PetrocikPetrocik 1996). A study examining forty-six issues across seventeen rich democracies (including many European countries, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand) found that issue ownership is quite stable, with right-of-center parties having ownership over public finance, law and order, immigration, and international affairs issues and left-of-center parties having ownership over the welfare state and the environment (Reference SeebergSeeberg 2017). One question is whether the implementation of new policies can shake up these patterns. An examination of a major Medicare reform in the United States suggests that the answer is no: Although majorities of panel survey respondents knew that Republicans had designed the popular new prescription drug benefit and had controlled government at the time of passage, that knowledge did not make them more likely to say that Republicans would do a better job managing entitlements or conducting health policy in the future (Reference CampbellMorgan and Campbell 2011). Issue ownership resembles attitudes toward program recipients in its stickiness: The images in people’s heads about political parties and about program recipients have proven largely impervious to policy feedbacks. Partisan shifts in vote share or party identification due to policy are typically ephemeral (Reference Galvin and ThurstonGalvin and Thurston 2018).