Of the approximately 16 500 psychiatric in-patients in the UK at any time, around one-quarter are parents of dependent children, with similar figures reported internationally.Reference Benders-Hadi, Barber and Alexander1,Reference Maybery and Reupert2 Parents in in-patient care are not a homogenous group; however, for the majority, hospital admission requires separation from their children. In many cases, this follows a period of acute mental illness and sometimes a difficult or non-voluntary admission process, which is distressing to parent and child.

For most adults with children, parenthood is an integral part of their identity, bringing both reward and challenge. This is no different for parents with serious mental health problems.Reference Hine, Maybery and Goodyear3 However, this parenting role is rarely acknowledged by services.Reference Lauritzen, Reedtz, Van Doesum and Martinussen4 Adults experiencing serious mental illness can provide nurturing parenting and derive satisfaction from this.Reference Diaz-Caneja and Johnson5,Reference Campbell, Hanlon, Galletly, Harvey, Stain and Cohen6 However, the challenges of parenting are understandably greater for those with severe mental illness. The ability to provide appropriate care may be compromised by symptoms and treatment, behavioural and relational challenges, financial hardship and isolation from the networks that parents call upon.Reference Strand, Boström and Grip7 Furthermore, mental health difficulties are often associated with specific parenting attributes, such as challenges containing children's emotions, boundary setting and overprotection.Reference Stepp, Whalen, Pilkonis, Hipwell and Levine8,Reference Wan, Abel and Green9 Consequently, having a parent with severe mental illness is sometimes associated with impaired psychosocial outcomes for children.Reference Argent, Kalebic, Rice and Taylor10

Although there has been limited research focusing on outcomes for children whose parents are in-patients in psychiatric units, there is evidence that such children are at risk of adverse outcomes, including being re-housed, (e.g. into foster care), poor school readiness and abuse.Reference Bell, Bayliss, Glauert, Harrison and Ohan11,Reference Konishi and Yoshimura12 Such parents also report increased psychological and behavioural problems in their children.Reference Markwort, Schmitz-Buhl, Christiansen and Gouzoulis-Mayfrank13

Parents who have received in-patient care largely characterise their experience as negative: hospital admission is seen as having a detrimental impact on the parenting role.Reference Scholes, Price and Berry14 For some, this rupture may continue beyond discharge, owing to child removal or because the relationship is perceived to be irretrievably damaged. Such parents also report low confidence in parenting and considerable parenting challenges.Reference Dolman, Jones and Howard15 Children report profound disruption to their lives, including negative experiences when visiting parents in hospital.Reference Källquist and Salzmann-Erikson16

However, negative outcomes are not inevitable, with many parents providing excellent care to their children as they manage their mental health and some children reporting positive aspects to parental mental ill health.Reference Drost, van der Krieke, Sytema and Schippers17

The provision of parenting support to parents with mental health difficulties (regardless of whether they are in-patients) is rare but likely to have cascading benefits for the family, including reducing the intergenerational transmission of mental health difficulties. A growing body of research suggests that effective interventions can be delivered to parents who experience a range of diagnoses.Reference Siegenthaler, Munder and Egger18,Reference Loechner, Starman, Galuschka, Tamm, Schulte-Körne and Rubel19 Furthermore, the literature suggests that parents overwhelmingly want support in their parenting role, want this support to occur preventively rather than in response to crisis and want it to exist beyond the perinatal period.Reference Dunn, Cartwright-Hatton, Startup and Papamichail20

Despite the challenges faced by parents in in-patient psychiatric care and the corollary risks to their children, there have been limited efforts to develop an evidence base of interventions for this vulnerable group. In a systematic review of interventions to support parents with severe mental illness, only two of 18 studies were delivered to parents during in-patient or residential treatment, with one delivered post-discharge.Reference Schrank, Moran, Borghi and Priebe21 Of the in-patient studies, one comprised a case-note review of co-admitted parents and children, with no reported change statistics.Reference Rothenburg, Cranz, Hartmann and Petermann22 The second focused on mothers with comorbid substance misuse and mental illness, with limited information about the intervention or outcomes.23 The third, delivered as post-discharge home visits for mothers with psychosis, focused on minimising readmission and did not specifically engage with parenting.Reference Cohler and Grunebaum24

There is a similar lack of research exploring the experience of being admitted to psychiatric care as a parent: a recent review of the experiences of in-patients included no mention of parenthood. An earlier review, which focused on support needs of families when a parent is admitted to hospital, included just six papers (of 18) that focused on the specific experience of parents.Reference Foster, Hills and Foster25

The current review extends the evidence base on support for parents using psychiatric in-patient care in two complementary areas of research:

(a) interventions to support the parent–child relationship within these settings;

(b) the experience of parents in in-patient settings.

Method

This systematic review is reported in line with PRISMA guidelines.Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann and Mulrow26 This paper is based on a doctoral thesis (PhD) by A.D.Reference Dunn27

Protocol registration

The protocol was registered the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (reference CRD42022309065).

Ethical statement

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and the Code of Conduct as set out by the British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP) and the British Psychological Society (BPS).

Eligibility

Broad inclusion criteria were applied (Table 1). Papers were considered if they included primary research published in any country between January 1980 and July 2022. All designs were eligible.

Table 1 PICOs schema used to inform eligibility criteria

For studies reporting parents’ experience of being psychiatric in-patients, past or present psychiatric in-patients with a child aged 12 months to 18 years at the time of treatment were included. Where both in-patients and community patients were included, data were extracted only for in-patients. For intervention studies, interventions had to be focused on supporting the parenting role and or the parent–child dyad, where the child was aged 12 months to 18 years, and the parent was in current psychiatric in-patient care.

Papers were excluded if they had no English-language abstract and/or the full paper was unavailable in English or German.

Information sources

PubMed, SCOPOS, Web of Science and PsychINFO were searched for papers from 1 January 1980 to 4 December 2021 with an extension to cover 4 December 2021 to 26 July 2022.

Search terms

The search terms were: Parent*OR mother*OR father*AND inpatient*OR ‘mental health unit*’OR‘psychiatric unit*’OR ‘psychiatric ward*’OR‘psychiatric hospital*’OR‘mental health rehabilitation unit'OR‘mental health residen*’OR‘mental health hospital*’. Reference lists of prior reviews and of final included papers were searched. Relevant academics were asked to identify additional papers and/or unpublished materials.

Study selection

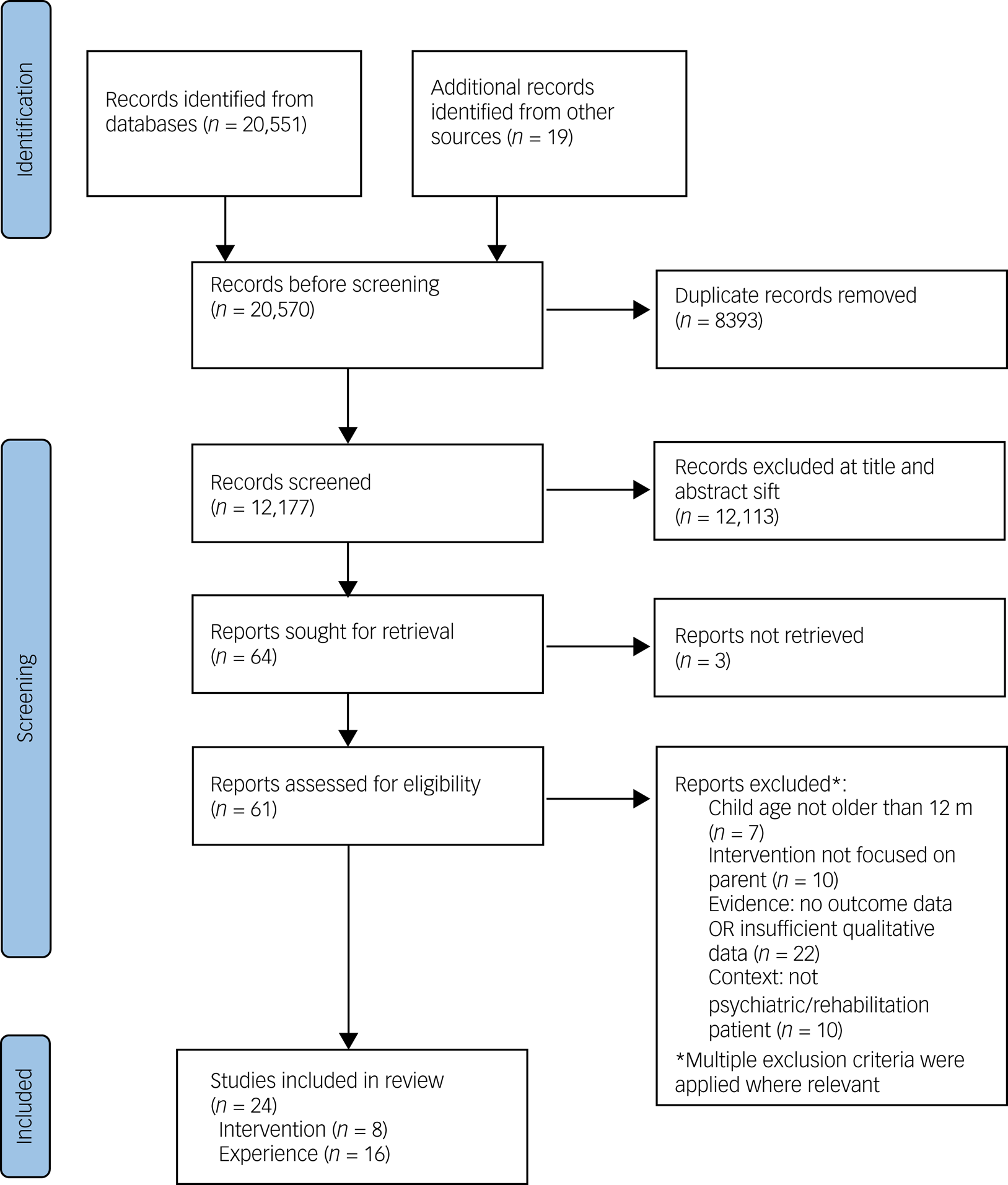

Following de-duplication, two reviewers from a pool of six independently screened 20% of titles and/or abstracts against the inclusion criteria. Disagreement was below 1% and was resolved via discussion. The remaining were screened by a single reviewer. See Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of studies included in the results.

Where possible, full-text papers were obtained for all studies that were retained following title/abstract screening. These were independently screened by two reviewers from a pool of three, with discrepancies resolved in consultation with a fourth. German-language papers were doubled-coded by two fluent German speakers, with additional discussion with the first author to reach consensus. For 61 full-text papers, there was a concordance rate of 95%. Three papers were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction

Data were extracted using either a qualitatively or a quantitively orientated data-extraction form (included in the Supplementary materials available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.67) generated by the team. All papers were extracted twice (by two members of a pool of six), with discrepancies resolved collaboratively.

Methodological quality

Methodological quality was assessed following data extraction, to evaluate the risk of bias. No papers were removed as a result. All papers were assessed by two coders (from a pool of four). For four of 26 papers where ratings were not in perfect agreement, ratings were resolved via discussion.

Intervention studies were appraised by two reviewers (from a pool of four) using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) 2018, which comprises two screening questions and five criteria focused on the paper type (i.e. randomised controlled trial (RCT) or descriptive study) using three response categories (Yes = 2; No = 0; Can't Tell = 0).

Qualitative papers (exploring experiences of parents) were assessed for quality using the 2018 Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool for qualitative research by two raters. This ten-item checklist uses three response categories (No = 0; Can't Tell = 0; Yes = 2). To increase sensitivity, an additional response category (Somewhat = 1) was included.Reference Long, French and Brooks28 See Tables 2 and 4.

Table 2 Description of included quantitative papers

MMAT, Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Intervention data synthesis

Owing to the small number of quantitative studies, heterogenous outcome measures and lack of reported effect sizes, a meta-analysis was inappropriate. Descriptive results are presented below.

Qualitative data synthesis

Qualitative data were subject to thematic synthesis employing a three-step approach.Reference Thomas and Harden29 In stages one and two, data were line-by-line coded by two raters. Codes were created iteratively and inductively and revised to generate a hierarchical code-set. The order by which papers were coded was shaped by the results of the quality assessment, so high-quality papers (those scoring >17 on CASP) were used to develop codes, and lower-quality papers were then incorporated.Reference Long, French and Brooks28 The text contained under each code was examined to check consistency. The third stage, carried out by A.D. in discussion with the team, generated analytic themes, informed by the research question, using an iterative process of refinement. Data forms, extracted data and data used for analyses are available from A.D.

Results

Study characteristics

A total of 20 551 titles were initially identified, with a further 19 from citation-chaining. Following de-duplication, 12 177 abstracts were screened, of which 64 progressed to full-text assessment. Subsequently, 24 papers met the inclusion criteria and were retained for data extraction. Of these, 16 focused on parents’ experiences, and eight were intervention studies. Eighteen studies were English-language and six were German-language (all intervention studies). See Fig. 1. Results are reported independently for the two parts of the study.

Interventions

Eight intervention papers met the criteria for inclusion (Table 2). Seven were published in Germany (six German-language, one English-language). One was published in the UK in English. Four included an all-female sample, and the remaining four included mothers and fathers. The methodological quality of papers varied, with four achieving >80% MMAT criteria but two achieving only 20%.

Study design and outcomes

Two papers reported RCTs.Reference Tritt, Nickel, Nickel, Lahmann, Mitterlehner and Leiberich30,Reference Lenz and Lenz31 In both, the intervention was co-admission of mother and child, and the control group was parents admitted without children.Reference Tritt, Nickel, Nickel, Lahmann, Mitterlehner and Leiberich30,Reference Lenz and Lenz31 Four studies employed a within-group pre–post or pre–post–post design.Reference Besier, Fuchs, Rosenberger and Goldbeck32–Reference Fritz, Domin, Thies, Yang, Stolle and Fricke35

Participants

Aggregating data from the eight intervention papers generated a sample of 428 participants. Demographic information was variable across papers (Table 3).

Table 3 Participant characteristics of included intervention studies. Includes data on participants in intervention group, and intervention group and control group where control is parent–child admission

a. Includes only data on participants included in follow-up assessment in Fritz (2018).

Summary of interventions

In all studies, the intervention was the co-admission of parent and child. We found no studies where the active intervention involved parents being admitted alone. In two studies, co-admission was the sole described intervention;Reference Tritt, Nickel, Nickel, Lahmann, Mitterlehner and Leiberich30,Reference Lenz and Lenz31 it was the treatment-as-usual condition in two further studies.Reference Fritz, Domin, Thies, Yang, Stolle and Fricke33,Reference Fritz, Domin, Thies, Yang, Stolle and Fricke35

In six studies, parent–child co-admission was supplemented with work on parenting or the parent–child relationship.Reference Besier, Fuchs, Rosenberger and Goldbeck32–Reference Verbeek, Schnitker and Schüren37 In one study, this comprised activities to promote parent–child interaction (e.g. movement therapy).Reference Besier, Fuchs, Rosenberger and Goldbeck32 In the single UK-based paper, parent–child co-admission was supplemented by provision of a family nurse who supported parenting and liaison with external agencies.Reference Healy and Kennedy36 The Leuchtturm–Elternprogramms comprised a 4-week mentalisation-oriented course, which included sessions designed to explore the parent's attachment experience, to foster positive attachment, including through relationship-repair and management of difficult situations.Reference Verbeek, Schnitker and Schüren37 Volkert and colleagues piloted a mentalisation-based intervention which incorporated individual and group psychoeducation and skills training.Reference Volkert, Georg, Hauschild, Herpertz, Neukel and Byrne34

Two papers evaluated the SEEK intervention.Reference Fritz, Domin, Thies, Yang, Stolle and Fricke33,Reference Fritz, Domin, Thies, Yang, Stolle and Fricke35 This 5-week group-based programme comprised stress reduction, psychoeducation focused on children's needs, mental health reciprocity, and increasing sensitivity to the impact of parental mental health on the child. In these papers, treatment-as-usual comprised parent–child co-admission.

In two papers, children also received psychological treatment.Reference Healy and Kennedy36,Reference Verbeek, Schnitker and Schüren37

Intervention effectiveness

Co-admission

Parent outcomes

In two studies, parent–child co-admission was associated with significant improvements in parental distress and mental health symptoms compared with baseline, with results stable at 6 months.Reference Fritz, Domin, Thies, Yang, Stolle and Fricke33,Reference Fritz, Domin, Thies, Yang, Stolle and Fricke35 Parents in one study reported significantly higher levels of satisfaction with treatment following co-admission compared with parents admitted alone.Reference Lenz and Lenz31 However, one paper reported no significant differences in symptoms compared with a group admitted alone.Reference Tritt, Nickel, Nickel, Lahmann, Mitterlehner and Leiberich30

Child outcomes

In two studies, there was a significant post-intervention improvement in child behaviour (hyperactivity, distractibility, adaptability) but no significant improvement in behavioural or emotional problems as identified by the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL).Reference Fritz, Domin, Thies, Yang, Stolle and Fricke33,Reference Fritz, Domin, Thies, Yang, Stolle and Fricke35

Co-admission plus further intervention

Parent outcomes

One intervention was associated with significant pre–post improvements in parent symptoms and quality of life.Reference Besier, Fuchs, Rosenberger and Goldbeck32 Another was associated with improvement in maternal depression in a case series.Reference Verbeek, Schnitker and Schüren37 Two SEEK trials showed significant main effects in a pre–post design, though no within-group effects were reported. The first trial reported significant reductions in parental strain and mental health symptoms and in depression and anxiety.Reference Klein, Späth, Schröder, Meyer, Greiner and Hautzinger38 These were replicated in the second trial, with a significant improvement in parental strain and overall mental health symptoms after 6 months. The Lighthouse Parenting Program was associated with significant improvement in parental stress.Reference Volkert, Georg, Hauschild, Herpertz, Neukel and Byrne34 The intervention of Healy and colleagues was associated with a descriptive account of improvement in family functioning, but no statistical analysis was reported.Reference Healy and Kennedy36

Child outcomes

There were significant improvements in children's behavioural and emotional symptoms and quality of life associated with the intervention of Besier and colleagues.Reference Besier, Fuchs, Rosenberger and Goldbeck32 SEEK was associated with significant reductions in child internalising and externalising symptoms and in behavioural and emotional problems.Reference Fritz, Domin, Thies, Yang, Stolle and Fricke33 Effects were maintained at 6 months for overall behavioural and emotional symptoms but not for internalising and externalising subscales.Reference Fritz, Domin, Thies, Yang, Stolle and Fricke35 In the case-series study, co-admission was associated with clinician reports of improved child sleep, social interaction, separation anxiety, and reduced temper tantrums and impulsivity compared with children who were not co-admitted with parents.Reference Verbeek, Schnitker and Schüren37

Parents’ experiences of in-patient care

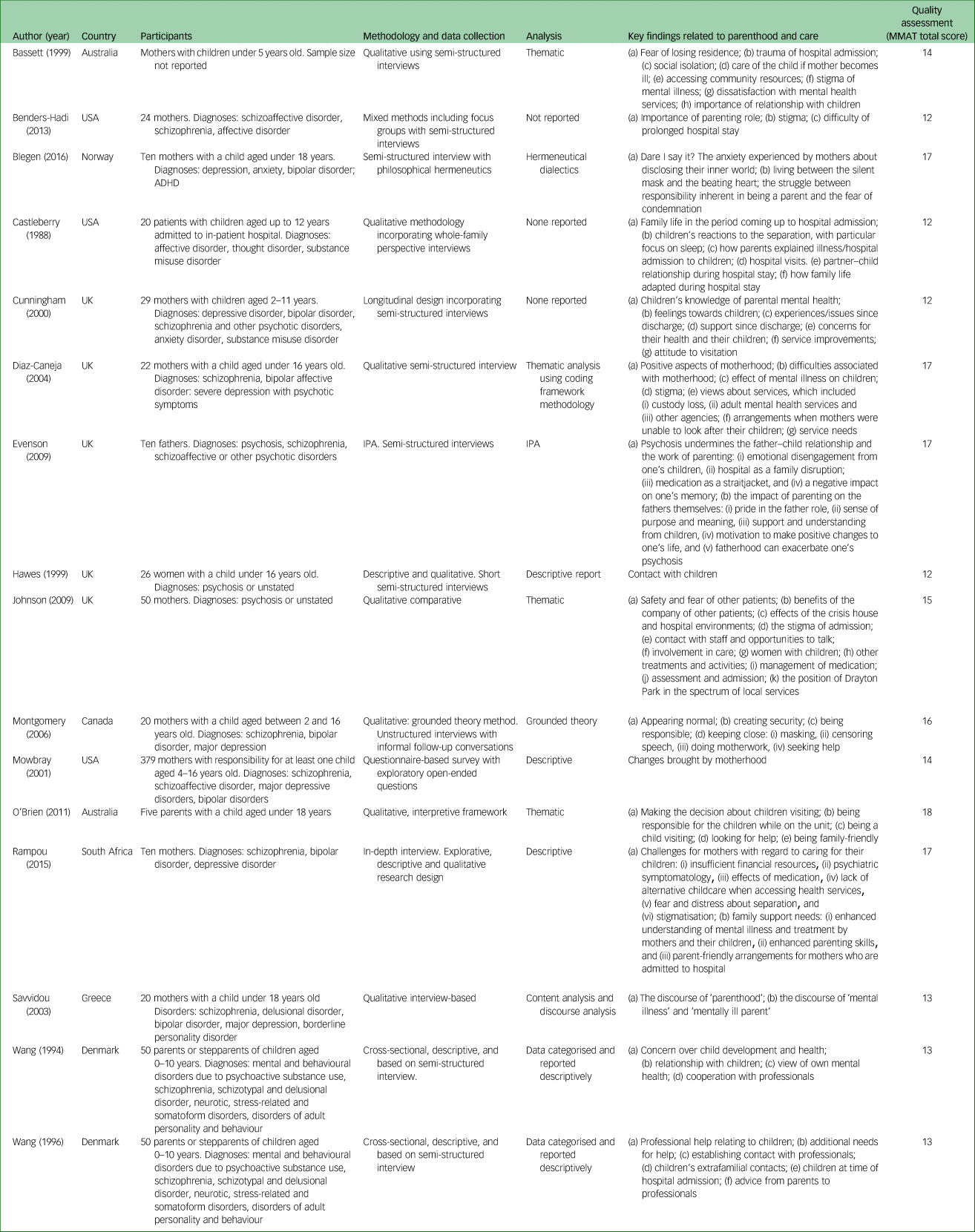

Sixteen papers were included, all published in English (described in Table 4). Papers were published in the following countries: UK (five papers), USA (three), Denmark (two) Canada (one), South Africa (one), Australia (two), Greece (one) and Norway (one). Fourteen recruited from in-patient settings or in-patient settings plus community settings, and two recruited exclusively from community mental health services.Reference Diaz-Caneja and Johnson5,Reference Evenson, Rhodes, Feigenbaum and Solly39 Ten papers reported exclusively on mothers, one only on fathers and four on mothers and fathers. One study used focus groups; the remainder used individual interviews. Where stated, the analysis was descriptive (five papers), thematic (four), discourse (one), interpretative phenomenological analysis (one), grounded theory (one) and hermeneutics (one). Seven papers were identified as of low quality according to the CASP checklist. See Table 4.

Table 4 Description of included qualitative papers

ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; IPA, interpretative phenomenological analysis.

Participants

Participant data from 14 papers were aggregated (one paper failed to report sample size,Reference Bassett, Lampe and Lloyd40 and one was excluded because the study employed a sample that had been reported elsewhere and already included in the countReference Wang and Goldschmidt41 to generate a combined sample of 629 participants. Gender, diagnoses care-giving responsibilities and marital status of participants are reported in Table 5.

Table 5 Participant characteristics of in-patient parent ‘experience’ studies

Key themes

Parents’ experiences were categorised into six themes: ‘who is looking after my child?’; ‘maintaining connection from hospital’; ‘impact on self as a parent’; ‘discharge is not the end’; ‘perceived child experience’; and ‘what needs to change’. Together, these represent the impact of hospital admission in terms of the parent's physical separation from their children as well as its effects on the parenting role, on the child, and on the parent's self-concept. The final theme integrates views on improvements that could be made to better support parents.

Who is looking after my child?

This theme, present in seven studies, focuses on care arrangements in place for children while their parent is in hospital. Many parents expressed worry, confusion or anger about these arrangements, as described by one mother:

‘On the ward, there were women who were very distressed by the fact that their children were in care somewhere and they couldn't see them, and I just think that it is so damaging.’Reference Diaz-Caneja and Johnson5

Parents identified difficulties in arranging care or having no-one to care for their children during their hospital stay, and, in cases where children were under the care of social services, not knowing who was looking after their child was a source of distress:Reference Diaz-Caneja and Johnson5,Reference Rampou, Havenga and Madumo42

‘When I was admitted at the hospital I was thinking of my children, where are they? Who is taking care of them? Who is bathing and making food for them?’Reference Rampou, Havenga and Madumo42

Even when co-parents or family members were looking after children, it was a source of worry or ambivalence.Reference Montgomery, Tompkins, Forchuk and French43 The exception was one study where four parents said they felt their children were looked after well.Reference Cunningham, Oyebode and Vostanis44

A number of parents associated hospital admission with a risk of permanent removal of children.Reference Diaz-Caneja and Johnson5,Reference Bassett, Lampe and Lloyd40,Reference Rampou, Havenga and Madumo42,Reference Montgomery, Tompkins, Forchuk and French43,Reference Savvidou, Bozikas, Hatzigeleki and Karavatos45,Reference Blegen, Eriksson and Bondas46 The threat of child-removal was a source of extreme distress in all accounts. Some parents reported worrying that the alternative care arrangements during their hospital stay made the subsequent removal of their child more likely, whether into the care of a co-parent as in the example below or into the care of the state.Reference Bassett, Lampe and Lloyd40,Reference Rampou, Havenga and Madumo42,Reference Montgomery, Tompkins, Forchuk and French43

‘I'm the one who fears that he [father] might take them from me saying that I'm an unfit mother.’

Another stated that:

‘I was scared when I was admitted at the hospital that they would take my children from me. I don't want them to stay with somebody or be taken away from me … ’ Reference Rampou, Havenga and Madumo42

Parents who had experienced removal of a child characterised it as highly distressing and detrimental to their recovery.Reference Diaz-Caneja and Johnson5,Reference Rampou, Havenga and Madumo42,Reference Savvidou, Bozikas, Hatzigeleki and Karavatos45

Maintaining connection from hospital

Ten studies featured parental accounts that discussed maintaining connection. For most, hospital admission involved a physical separation from their children, which was accompanied by a desire to maintain some form of connection, for example, through regular telephone contact.Reference Diaz-Caneja and Johnson5,Reference Evenson, Rhodes, Feigenbaum and Solly39,Reference Bassett, Lampe and Lloyd40,Reference Castleberry47–Reference O'Brien, Anand, Brady and Gillies49

Child visitation was mentioned in several studies.Reference Diaz-Caneja and Johnson5,Reference Evenson, Rhodes, Feigenbaum and Solly39,Reference Castleberry47,Reference Hawes and Cottrell48,Reference O'Brien, Brady, Anand and Gillies50,Reference Johnson, Bingham, Billings, Pilling, Morant and Bebbington51 However, visits were ambivalently represented. In two papers, children were described as making regular visits to parents, including eating meals with them.Reference Castleberry47,Reference Hawes and Cottrell48 However, for many parents, the desire to see children conflicted with concerns about the risks of visiting, including the suitability of the ward environment, owing to the lack of appropriate visiting facilities, and about exposure to other unwell patients.Reference Diaz-Caneja and Johnson5,Reference Evenson, Rhodes, Feigenbaum and Solly39,Reference Hawes and Cottrell48,Reference O'Brien, Anand, Brady and Gillies49,Reference Johnson, Bingham, Billings, Pilling, Morant and Bebbington51

‘I'm a little cautious about having them in to see me, the ward, cause . . . some people are quite disturbed and it can be quite upsetting for them.’Reference Evenson, Rhodes, Feigenbaum and Solly39

Some parents did not want their child to see them while they were unwell.Reference Evenson, Rhodes, Feigenbaum and Solly39,Reference Castleberry47,Reference O'Brien, Anand, Brady and Gillies49 One father described having been admitted to hospital annually for periods in excess of a month but refusing visits from his child for this reason.Reference Evenson, Rhodes, Feigenbaum and Solly39

For some, the distance afforded by admission offered a break from the stresses of parenting and/or family life, after which the parent was able to ‘return to bond with their children as a “new mom”.’Reference Montgomery, Tompkins, Forchuk and French43,Reference Johnson, Bingham, Billings, Pilling, Morant and Bebbington51

Impact on self as parent

Nine studies explored the impact of hospital admission on parenting identity. The experience of hospital admission and the poor mental health preceding it appeared to diminish parents’ belief in their value as a parent.Reference Evenson, Rhodes, Feigenbaum and Solly39,Reference Rampou, Havenga and Madumo42,Reference Cunningham, Oyebode and Vostanis44,Reference Castleberry47,Reference Wang and Goldschmidt52 Hospital admission was described as preventing parents from fulfilling their parental responsibilities.Reference Evenson, Rhodes, Feigenbaum and Solly39,Reference Rampou, Havenga and Madumo42,Reference Castleberry47 It meant parents were ‘not available’,Reference Rampou, Havenga and Madumo42 as one father described:

‘I haven't been there for them sometimes because I've been in hospital . . . I miss out, and my son misses out on my contact.’Reference Evenson, Rhodes, Feigenbaum and Solly39

Some parents viewed their parenting negatively because of harms they felt they may have caused their children through exposure to their symptoms.Reference Montgomery, Tompkins, Forchuk and French43,Reference Cunningham, Oyebode and Vostanis44,Reference Castleberry47,Reference Wang and Goldschmidt52 For example, mothers in the study by Montgomery and colleagues felt they struggled to meet their ‘primary responsibility’, which was to protect their children from their illness.Reference Montgomery, Tompkins, Forchuk and French43 This was accompanied by the fear that they may have ‘inadvertently hurt’ their children. Rampou and colleagues describe parental concern about children being cast into a parental role by their parent's illness, in particular where a child took on caring responsibilities.Reference Rampou, Havenga and Madumo42

Parents also described the corrosive effect of stigma associated with hospital admission.Reference Benders-Hadi, Barber and Alexander1,Reference Evenson, Rhodes, Feigenbaum and Solly39,Reference Bassett, Lampe and Lloyd40,Reference Rampou, Havenga and Madumo42,Reference Cunningham, Oyebode and Vostanis44–Reference Castleberry47 For some, this was related to shame about being unwell and admitted to hospital; this self-stigma was related to their view of their own illness or the hospital environment:

‘inpatients in psychiatric units are mad and dangerous’. Reference Savvidou, Bozikas, Hatzigeleki and Karavatos45

Others felt that hospitalisation affected the way they were perceived and treated by others, including the access they were given to their children:Reference Benders-Hadi, Barber and Alexander1,Reference Evenson, Rhodes, Feigenbaum and Solly39,Reference Bassett, Lampe and Lloyd40,Reference Johnson, Bingham, Billings, Pilling, Morant and Bebbington51

‘And then it was treated like it was something to be ashamed of and I think that's why society's attitude that mental illness is something that it's sort of like having ‘crazy bitch’ stamped across my forehead and everybody treats you differently because you have been a patient in a psychiatric unit.’Reference Bassett, Lampe and Lloyd40

For some, this stigma, rather than illness or hospital admission, was represented as the thing which had most affected them as parents,Reference Benders-Hadi, Barber and Alexander1 as one mother expressed:

‘I'm probably afraid of being labelled a lunatic and then they will take my children away.’Reference Blegen, Eriksson and Bondas46

Discharge not the end

In six studies, parents described challenges after their hospital stay. Although returning to the parental role motivated engagement with treatment for several parents,Reference Benders-Hadi, Barber and Alexander1,Reference Diaz-Caneja and Johnson5,Reference Savvidou, Bozikas, Hatzigeleki and Karavatos45 discharge was not always viewed as straightforwardly positive.Reference Benders-Hadi, Barber and Alexander1,Reference Diaz-Caneja and Johnson5,Reference Bassett, Lampe and Lloyd40,Reference Cunningham, Oyebode and Vostanis44,Reference Johnson, Bingham, Billings, Pilling, Morant and Bebbington51 No paper explicitly discussed the threshold at which parents had been discharged; however, there were clear indications that many were still unwell and worried about their ability to cope with the practicalities of parenting.Reference Evenson, Rhodes, Feigenbaum and Solly39,Reference Rampou, Havenga and Madumo42,Reference Cunningham, Oyebode and Vostanis44,Reference Johnson, Bingham, Billings, Pilling, Morant and Bebbington51 In one example, a father found the intensity of family life too great and returned to hospital.

‘Four young children . . . all under 5 and that, and they're flying about, large as life all the time. You know, as soon as I got home, after coming out of a quiet hospital, you know it was too much for me. I had to go back in.’Reference Evenson, Rhodes, Feigenbaum and Solly39

The failure of in-patient settings to engage with the parenting role was felt to contribute to these difficulties.Reference Montgomery, Tompkins, Forchuk and French43,Reference Blegen, Eriksson and Bondas46 By focusing on symptoms and failing to give attention to the parental role and the specific needs of parents, treatment failed to support them in the resumption of that role:

‘Since I've been in treatment I'm not anxious, I'm thinking better, I'm sleeping, I can focus but what about when I leave to go home? I will keep seeing [the psychiatrist] but it is the other stuff that worries me … when I have to get up at night, when I have to play with them but I'm tired.’

An additional complication of discharge related to difficulties in re-establishing relationships with children.Reference Benders-Hadi, Barber and Alexander1,Reference Diaz-Caneja and Johnson5,Reference Cunningham, Oyebode and Vostanis44,Reference Johnson, Bingham, Billings, Pilling, Morant and Bebbington51 One aspect focused on the child's understanding of the separation and feelings of rejection.Reference Diaz-Caneja and Johnson5 Other parents highlighted their inability to communicate their experiences of hospital admission or illness or to explain their absence.Reference Benders-Hadi, Barber and Alexander1,Reference Diaz-Caneja and Johnson5,Reference Castleberry47 One mother pulled these strands together when describing aspects of parenting that she felt she would have to re-learn:

‘It's like I have to learn how to be around my kids again … how to get along with them, how to tell them I love them, and how to explain that I wasn't there because I'm sick.’Reference Benders-Hadi, Barber and Alexander1

The potential of readmission was raised by some studies. For some parents, preventing future hospital admission motivated treatment adherence,Reference Mowbray, Oyserman, Bybee, Macfarlane and Rueda-Riedle53 whereas in other accounts, help-seeking was avoided owing to the risk of readmission and the accompanying separation from children.Reference Diaz-Caneja and Johnson5,Reference Wang and Goldschmidt41 Just as some parents experienced hospital admission as a ‘hostile’ act,Reference Montgomery, Tompkins, Forchuk and French43,Reference Savvidou, Bozikas, Hatzigeleki and Karavatos45 another expressed fear that the father of her children would use it as an aggressive act towards her:

‘I'm scared. I'm scared. I'm so scared.’Reference Bassett, Lampe and Lloyd40

Perceived child experience

Parents’ thoughts about their children's experiences was reported by eight studies, though in limited form.Reference Evenson, Rhodes, Feigenbaum and Solly39,Reference Rampou, Havenga and Madumo42,Reference Cunningham, Oyebode and Vostanis44,Reference Savvidou, Bozikas, Hatzigeleki and Karavatos45,Reference Castleberry47 In some cases, hospital admission of the parent was described as having a negative impact on the child's affect or behaviour:Reference Rampou, Havenga and Madumo42,Reference Cunningham, Oyebode and Vostanis44,Reference Savvidou, Bozikas, Hatzigeleki and Karavatos45,Reference Castleberry47

‘It looks like he's holding something, a worry inside. When he came to the hospital the next day to see me, he was so quiet and bashful. I could hardly get him to talk.’

However, other parents described their children as adapting to or having ‘an understanding’ of the situation.Reference Cunningham, Oyebode and Vostanis44,Reference Castleberry47

As for earlier themes, where parents discussed the impact of their hospital admission or health on their children, it was frequently associated with feelings of shame, and the focus of discussions was often on self-blame rather than the experience of the child.

What needs to change?

Nine studies highlighted a need for improved provision to better enable parents to maintain their parenting role while undergoing in-patient treatment. The clearest target for improvement was the development of appropriate facilities for children to visit parents during treatment.Reference Diaz-Caneja and Johnson5,Reference Rampou, Havenga and Madumo42,Reference Cunningham, Oyebode and Vostanis44,Reference O'Brien, Anand, Brady and Gillies49 This included ‘family rooms’ or private spaces away from the main ward:Reference Diaz-Caneja and Johnson5,Reference Cunningham, Oyebode and Vostanis44 ‘somewhere quieter’Reference Johnson, Bingham, Billings, Pilling, Morant and Bebbington51 and ‘away from other patients’.Reference Diaz-Caneja and Johnson5 In some studies, there was a call for co-admission of child and parent.Reference Diaz-Caneja and Johnson5,Reference Rampou, Havenga and Madumo42

The second key suggestion was that parental identity should be engaged with and supportedReference Wang and Goldschmidt41,Reference Rampou, Havenga and Madumo42,Reference Blegen, Eriksson and Bondas46,Reference Mowbray, Oyserman, Bybee, Macfarlane and Rueda-Riedle53 and that staff should engage with this with openness, persistence and empathy – in the words of one parent, ‘to show more love’.Reference Wang and Goldschmidt41 As described by one parent, therapists need to enable parents to share what they hold as important:

‘I feel I have much at heart, but when I arrive he asks me about how I have been since the last time, and continues with that, including techniques and exercises, and I have no opportunity to say what I was going to say.’Reference Blegen, Eriksson and Bondas46

Parents also proposed that greater effort should be made to identify that a patient is a parentReference Cunningham, Oyebode and Vostanis44 and that support should aim to strengthen parental functioning, promote parenting skills and ease transition home.Reference Wang and Goldschmidt41,Reference Rampou, Havenga and Madumo42,Reference Wang and Goldschmidt52,Reference Mowbray, Oyserman, Bybee, Macfarlane and Rueda-Riedle53

Discussion

The studies that explored the experiences of in-patient parents indicated that parents largely experience psychiatric in-patient care negatively and find that it has an impact on their ability to function in their parenting role. This impact arises as a consequence of several factors. Chief among these is the physical separation of parents and children, but the impact of stigma (self and external) was also clear. Parents’ concern about their ability to provide care once discharged and worry about the potential loss of their children also featured widely.

Where parents described what improvements should be made, the inappropriateness of facilities for child visits was emphasised. It is noteworthy that poor provision of visiting facilities was highlighted in the oldest included paper and continued to be flagged as a concern by parents 25 years later. This echoes a 2021 review where women identified a similar tension between the negative impact of separation and belief that hospital was unsafe for child visits.Reference Scholes, Price and Berry14 The lack of appropriate provision for children's visits has also been identified as a concern by psychiatric nurses and by children themselves.Reference O'Brien, Brady, Anand and Gillies50,Reference Houlihan, Sharek and Higgins54

However, although there has been some research interest in the experiences of parents who are in-patients, there has been comparatively little work attempting to develop or evaluate interventions for this group. Even employing broad search criteria, the results of this review include just a handful of interventions. Moreover, all of these studies examined an intervention that was centred on co-admission of parent and child, and all but one reported interventions that were delivered in the German health service. Co-admission was largely associated with positive outcomes for parents and children and with high treatment satisfaction. In Germany, co-admission exists within the broader health system through a network of ‘Mutter-Kind-Einrichtungen’ in which parents receive care alongside their child. However, these centres are not psychiatric wards; rather, they provide rehabilitative and preventive holistic treatment to parents who experience psychological and/or physical ‘exhaustion’.Reference Arnhold-Kerri, Sperlich and Collatz55 These settings reflect a wider, systemic engagement with the parent and child in addressing parental difficulties. By contrast, only one intervention study from elsewhere in the world (UK) was identified. This involved co-admission of parent and child, but this provision is now no longer offered.Reference Healy and Kennedy36 Although co-admission may not be a realistic ambition within the UK mental health system, supporting contact between parent and child is realistic and should clearly be prioritised.

Studies that offered parent-oriented interventions in addition to co-admission provided tentative evidence of effectiveness. These interventions, ranging from supporting parent–child interaction to structured multi-session psychoeducational interventions, were associated with improved outcomes for parent, child or parenting, or a combination of these.Reference Schrank, Moran, Borghi and Priebe21,Reference Radley, Sivarajah, Moltrecht, Klampe, Hudson and Delahay56

Clinical implications

The results of this review suggest three areas where improvements could have substantial impacts on in-patient parents and their children.

Family-friendly visiting rooms

In the UK, the Mental Health Act (1983) states that every effort should be made to support in-patient parents to maintain contact with relatives and to continue to support their children. It is clear that, in order to facilitate this, family-friendly spaces should be available in all psychiatric in-patient settings, and these, if managed well (ensuring privacy and safety), would be welcomed by parents. Unfortunately, a recent review by the Scottish Executive highlighted ‘patchy’ provision of child-friendly visiting spaces,57 and the situation is likely to be similar across the UK. In Australia, implementation of family-friendly rooms has been associated with cascading benefits, from maintenance of the parent–child relationship to promotion of parental recovery. Staff have also suggested that these spaces may be associated with a reduction in stigma experienced by parents.Reference Isobel, Foster and Edwards58 In creating an appropriate environment for children, family-friendly spaces could also address the negative attitudes and experiences children associate with their parent's mental health.Reference Källquist and Salzmann-Erikson16

‘Patient as parent’ thinking

It is clear that in-patient units could engage better with their patients’ identities as parents. Such ‘patient as parent’ thinking could include improved recognition of the parenting role in general ward care (e.g. asking about patients’ families, encouraging them to talk about their children and their concerns for them). In addition, it is likely that interventions that support parenting and, in particular, the parent–child relationship, would have benefits for both parent and child upon discharge. Currently, such engagement is ad hoc and uncommon: a recent survey of British mental health workers found that in-patient staff were the least likely of any professional group to engage with patients in terms of their parenting role.Reference Dunn, Cartwright-Hatton, Startup and Papamichail20 The willingness of staff to engage in this way is influenced by a range of factors including confidence and training.Reference Dunn, Cartwright-Hatton, Startup and Papamichail20 However, given that both staff and parents recognise the importance of validating a patient's parenting role, there is a need for services to do so.Reference Dunn, Cartwright-Hatton, Startup and Papamichail20,Reference Bartsch, Roberts, Davies and Proeve59 Furthermore, tentative evidence suggests that when staff do engage with their clients’ parenting role, there is potential for cascading benefits for the parent–child dyad.Reference Afzelius, Östman, Råstam and Priebe60

Parent and child co-admission

Several studies identified parent–child co-admission as a suitable method for supporting the parent–child relationship during hospital treatment. It was viewed positively by most parents who experienced it, although a minority described it as a potential impediment to treatment effectiveness. However, this approach is likely to be considerably more expensive than solitary admission of parents, and major changes to service infrastructure would be required.

Strengths and limitations

This review employed purposely broad inclusion criteria yet found only a small number of reports of interventions delivered to parents accessing in-patient care. As such, it may not represent the full range of experiences. Furthermore, the search strategy did not include grey literature, which may have excluded reports of small-scale interventions.

Strengths included the use of thorough and inclusive search terms and accessing of papers written in two languages (German and English) which, between them, are likely to capture a large amount of the literature. However, the failure to include papers in additional languages may have biased results towards research carried out in high-income countries. This limits exploration of the experience and support for in-patients in a wider range of health systems. High levels of heterogeneity in the data rendered meta-analysis inappropriate.

In drawing together literature from a range of nations, the review sought to engage with experiences of in-patient parenthood. Although the clear identification of common experiences and needs is a strength, there would be utility in engaging with the impacts of different health systems and cultural norms, which may affect the delivery and experience of care. Furthermore, individual, familial and treatment variables are likely to affect a parent's experience of care. Although there was not opportunity within this review to engage with these factors, they warrant further investigation.

Given the limited data, the variation in extent and form of engagement, and the reliance on within-groups analysis (including when a control group was present), the results of the current review should be interpreted cautiously. However, although this evidence gap is disappointing, it demonstrates the need for research in which interventions are scrutinised. Furthermore, in designing studies, researchers should incorporate standard outcomes relating to parent and child well-being, as well as the specific behavioural or functional targets of the programme.

Implications for in-patient provision

Bringing together the evidence on the parental experience of in-patient care and the provision offered to in-patient parents makes the unmet need within services clear. Hospital admission of a parent typically reflects a situation in which the parent's mental health precludes them from caring for their child. This may exist alongside other adversity such as socioeconomic disadvantage, lack of social and familial networks, housing instability, and interparental conflict or abuse.Reference Saraceno, Levav and Kohn61–Reference Suglia, Duarte and Sandel63 Whereas in-patient care cannot address the multiple vulnerabilities faced by some parents, it should not contribute to them by hindering the relationship between parent and child. Although this review is unable to provide recommendations on the form and content of future interventions, it can conclude that, at the very least, in-patient provision should identify and engage with the parenting identity of parents and offer appropriate facilities for patients’ children to visit.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2023.67.

Data availability

This study is a re-analysis of existing data which are openly available at locations cited in the ‘References’ section of this paper.

Author contributions

A.D.: conceptualisation, methodology, investigation, data curation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, supervision, project administration; H.C.: validation, writing – review and editing; C. E.-P.: validation, writing – review and editing; J.K.: validation, writing – review and editing; E.S.: validation, writing – review and editing; B.P.: methodology, writing – review and editing; S.C.-H.: methodology, validation, writing – review and editing.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC: ES/J500173/1). ESRC had no role in the study design; the collection, analysis or interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.