Impact statement

Coastal communities, Indigenous peoples, and small-scale fishers are intimately connected with the ocean. Yet, these historically and structurally marginalized groups often bear a disproportionate distribution of coastal and marine harms, and are culturally and politically excluded from marine decision-making. In response, calls for blue justice are emerging. Here, we review key perspectives, new developments, and gaps in the emerging blue justice scholarship. We also synthesize existing case studies of blue injustices and review some of the many successful examples of grassroots resistance efforts to help define what blue justice entails. We aim to help center the knowledge, strength, and agency of coastal communities responding to blue injustices. Ultimately, concerted efforts are needed by all to support and empower coastal communities to reject blue injustices and to achieve their diverse aspirations for blue justice.

Introduction

“We are not drowning, we are fighting!!” read a fabric banner held by members of the Pacific Climate Warriors in Tokelau on March 2, 2013. The banner was part of the Pacific Warrior Day of Action in protest of the impacts of climate inaction on coastal nations. One year later, 12 cargo ships were due to collect coal from the world’s largest coal port in Newcastle, Australia, but only four succeeded (McNamara and Farbotko, Reference McNamara and Farbotko2017). The other eight ships were blocked by activists from a dozen Pacific Island nations in traditional canoes who gathered to oppose Australia’s continuing commitment to coal and to call for immediate climate action (McNamara and Farbotko, Reference McNamara and Farbotko2017). At the 2021 Conference of Parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Brianna Fruean, a Samoan youth climate activist, told the international community, “[t]he climate crisis and social inequities are all symptoms of a world shaped by colonialism and then by capitalism […] [f]or hundreds of years my people have […] fought back against our colonisers […] we can teach you how to fight back like us” (Fruean, Reference Fruean2021).

Local activism in defense of the ocean is not new. Rather, the examples above are reflective of a long history of coastal peoples’ fight for justice (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Le Billon, Belhabib and Satizábal2022). For example, 120 years ago Indigenous peoples living along the Gulf of Mexico defended their rights to subsistence livelihoods against powerful and violent foreign oil companies (Santiago, Reference Santiago2012). In the 1960s, Native Hawaiian surfers formed “Save Our Surf,” a grassroots organization that campaigned to maintain their rights to the surf zone against neo-colonial development and associated environmental degradation, such as dredging to expand the beaches of Waikīkī for tourists (Walker, Reference Walker2011; Ingersoll, Reference Ingersoll2016). In the 1970s, more than 10 million small-scale fishers in India mobilized to stop factory fishing, the use of mechanized trawls and the forces of neoliberal globalization in fisheries more broadly (Sinha, Reference Sinha2012). The World Forum of Fisher Peoples, a social movement of small-scale fisher people from across the world, was founded in the late 1990s by a group of organizations from the Global South and has advocated for the rights of small-scale fisher for the last three decades. Across our blue planet, coastal communities have long mobilized to defend their rights, to oppose harmful projects and to redefine their collective futures.

What is new is the emerging scholarship on blue justice that is developing alongside local resistance efforts. The term blue justice was introduced into academic circles by Moenieba Isaacs in 2018 (Jentoft et al., Reference Jentoft, Chuenpagdee, Said and Isaacs2022). Since then, academic engagement with the concept has grown rapidly (e.g., Isaacs, Reference Isaacs2019; Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Blythe, White and Campero2021a; Jentoft and Chuenpagdee, Reference Jentoft and Chuenpagdee2022; Jentoft et al., Reference Jentoft, Chuenpagdee, Said and Isaacs2022). Most blue justice scholars share a common interest in issues of equity and justice for coastal people. Yet, the term and scholarship remain relatively new. As Engen et al. (Reference Engen, Hausner, Gurney, Broderstad, Keller, Lundberg and Fauchald2021, p. 3) recently observed, “(i)n the absence of a coherent understanding of blue justice, there is a critical need to elucidate the concept.” While literature using the term blue justice is new, there is a long history of research on marine and coastal injustices and grassroots resistance efforts that can inform our thinking about blue justice and help define its scope. In this paper, we conduct a qualitative and narrative review of the blue justice scholarship, cases of blue injustice, and grassroots resistance efforts (see Supplementary Material).

We begin with a review and synthesis of emerging perspectives, new developments, and gaps in the blue justice literature. Second, we review case studies of blue injustice to highlight the disproportionate exposure of oppressed and marginalized people in coastal communities to marine environmental harms and hazards, and how historical and structural inequalities and various forms of social, political and economic power (re)produce blue injustices. Third, we review cases of grassroots resistance efforts that have stopped exploitative practices and proposed alternative coastal futures, focusing especially on the insights that successful blue justice movements provide. The article concludes with a discussion of blue justice theory and practice, as well as with some implications for understanding and supporting blue justice now and into the future.

The rise of blue justice scholarship

The term “blue justice” was coined by Moenieba Isaacs in 2018 during the 3rd World Small-Scale Fisheries Congress in Thailand (Jentoft et al., Reference Jentoft, Chuenpagdee, Said and Isaacs2022). Isaacs’ argued that blue justice is a concept situated in social justice for small-scale fisheries that contest the exclusion and marginalization of small-scale fishers (Isaacs, Reference Isaacs2019). For Isaacs, blue justice is also a call for collaborative research between academics, civil society, nongovernmental organizations and practitioners (Isaacs, Reference Isaacs2019).

Building on these ideas, much of the initial academic work on blue justice was led by members of the Too Big to Ignore (TBTI) network (http://toobigtoignore.net/). Members of the network have long advocated for the rights of small-scale fishers (Jentoft, Reference Jentoft1989; Isaacs, Reference Isaacs2012). Following the 2018 World Small-Scale Fisheries Congress and Isaacs’ introduction of the term, members of TBTI began using the term blue justice to advocate for the recognition of small-scale fishers’ rights to access and participate equitably in the blue economy (Chuenpagdee, Reference Chuenpagdee, Kerezi, Kinga Pietruszka and Chuenpagdee2020; Jentoft and Chuenpagdee, Reference Jentoft and Chuenpagdee2022; Jentoft et al., Reference Jentoft, Chuenpagdee, Said and Isaacs2022). Later that year, TBTI launched an initiative called “Blue Justice for Small-Scale Fisheries.” The initiative involved the development of an online platform collecting and sharing stories about blue injustices called “Blue Justice Alert” (http://toobigtoignore.net/blue-justice-alert-project/) (Kerezi et al., Reference Kerezi, Kinga Pietruszka and Chuenpagdee2020). Global case studies compiled through the initiative were published in 2022 in a book called “Blue Justice: Small-Scale Fisheries in a Sustainable Ocean Economy” (Jentoft et al., Reference Jentoft, Chuenpagdee, Said and Isaacs2022). The book represents the first significant compilation of case studies of blue (in)justice. The authors argue that realizing blue justice will require radical changes in how blue justice is perceived, institutionalized and practiced on the ground (Chuenpagdee et al., Reference Chuenpagdee, Isaacs, Bugeja-Said, Jentoft, Jentoft, Chuenpagdee, Said and Isaacs2022).

Other groups have also been central in advocating for justice for small-scale fisheries, although they have not always used the term blue justice explicitly. For example, the World Forum of Fisher Peoples and the World Forum of Fish Harvesters and Fish Workers have campaigned for the rights of small-scale fishers for decades (WFFP, 2014; WFFP and WFF, 2015). They have mobilized – through publications, meetings and protests, among other activities – to protect the livelihoods and commons of small-scale fishers from exploitation and encroachment. The WorldFish Centre has also been a leading voice in support of small-scale fishers’ rights (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Allison, Andrew, Cinner, Evans, Fabinyi, Garces, Hall, Hicks, Hughes, Jentoft and Ratner2019).

In academic circles, the term blue justice is often intentionally deployed as a counter-narrative to the blue economy (Schutter et al., Reference Schutter, Hicks, Phelps and Waterton2021). Chuenpagdee et al. (Reference Chuenpagdee, Isaacs, Bugeja-Said, Jentoft, Jentoft, Chuenpagdee, Said and Isaacs2022) explain that the “blue” part of the term blue justice was included as a direct response to growing endorsement of “blue” economy initiatives by many governments, ocean-based industries and financial institutions. In the United States, scholars have proposed blue justice as a framework for promoting sustainable and equitable governance of the blue economy (Axon et al., Reference Axon, Bertana, Graziano, Cross, Smith, Axon and Wakefield2022). Case studies and reviews have shown how blue economy policies and the accompanying changes in rules and authority can lead to injustices, for example, the spatial displacement of small-scale fishers and Indigenous peoples, exclusion from decision-making, and inequitable distribution of benefits and costs (Barbesgaard, Reference Barbesgaard2018; Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Blythe, White and Campero2021a). Perspectives that position blue justice as a counter-narrative to the blue economy are important since policy frameworks that account for the uneven distribution of social and environmental costs and benefits of blue economy or blue growth initiatives remain largely absent (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Cisneros-Montemayor, Blythe, Silver, Singh, Andrews, Calo, Christie, Di Franco, Finkbeiner, Gelcich and Sumaila2019).

From its initial focus on justice for small-scale fishers, blue justice scholarship has begun to highlight injustices experienced by other marginalized coastal groups, including women, Indigenous Peoples, and low-income populations and nations. For example, through their case studies in Tanzania, Chile, France and the United Kingdom, Gustavsson et al. (Reference Gustavsson, Frangoudes, Lindström, Ávarez and de la Torre Castro2021) find that gendered power inequities in fisheries and women’s marginalized participation in fisheries governance are associated with procedural injustices. They argue that in “developing the Blue Justice concept, there is a need to avoid reproducing ongoing and historical omissions of gender issues” (Gustavsson et al., Reference Gustavsson, Frangoudes, Lindström, Ávarez and de la Torre Castro2021, p. 1). An international group of early career researchers recently proposed that “[b]lue justice is an approach to interrogate how the blue economy affects [I]ndigenous marine users’ historical rights” (von Thenen et al., Reference von Thenen, Armoškaitė, Cordero-Penín, García-Morales, Gottschalk, Gutierrez, Ripken, Thoya and Schiele2021, p. 4., emphasis added). Bennett et al. (Reference Bennett, Blythe, White and Campero2021a) highlight that the economic benefits of blue growth initiatives tend to be concentrated among wealthy and powerful actors, while low-income populations are often further marginalized. This literature is drawing more explicitly on the environmental justice literature, which argues that exposures to environmental harms are distributed unevenly by race and class (Bullard, Reference Bullard1990, Reference Bullard1994; Agyeman et al., Reference Agyeman, Schlosberg, Craven and Matthews2016; Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Alava, Ferguson, Blythe, Morgera, Boyd and Côté2023). For example, Anbleyth-Evans et al. (Reference Anbleyth-Evans, Prieto, Barton, Garcia Cegarra, Muslow, Ricci, Campus and Francisca2022) argue that “[b]lue justice, simply, is defined as achieving environmental justice in the marine environment.” Yet, explicit engagement with race and blue injustices remains a gap for blue justice scholarship. Taken together, these developments suggest that the blue justice scholars are expanding their analysis of which individuals and groups experience blue injustice from a focus on small-scale fishers to broader notions of intersecting identity characteristics.

Some blue justice scholars and movements are framing blue justice as food sovereignty (Barbesgaard, Reference Barbesgaard2018). For example, small-scale fishers’ movements are increasingly framing their opposition to the blue economy in terms of broader struggles for food sovereignty (Barbesgaard, Reference Barbesgaard2018). Jonas (Reference Jonas2021), a member of the Australian Food Sovereignty Alliance, argues that blue justice entails grassroots movements of peasants and fishers rejecting corporate capture of food systems and food systems discourses, and proposes radical transformations in food production systems. In 2015, the World Forum of Fisher Peoples’ and the World Form of Fish Harvesters and Fish Workers issued a statement highlighting the essential role of small-scale fishers in supporting livelihood and food security for millions of people and demanding food sovereignty and justice (WFFP and WFF, 2015).

To date, blue justice scholars have primarily employed case studies to provide empirical evidence for the assertion that small-scale fishers and other marginalized coastal groups bear an inequitable share of the costs of coastal and marine harms, and are excluded from the benefits of marine resource use and decision-making (e.g., Engen et al., Reference Engen, Hausner, Gurney, Broderstad, Keller, Lundberg and Fauchald2021; Jentoft et al., Reference Jentoft, Chuenpagdee, Said and Isaacs2022). Ertör (Reference Ertör2021) employed a unique approach by examining 120 fishers’ conflicts that have been recorded in the environmental justice atlas (https://ejatlas.org/). Schreiber et al. (Reference Schreiber, Chuenpagdee and Jentoft2022) have called for the blue justice methodologies to expand beyond descriptive analyses of the unequal distributions of impacts to include the development of new words and vocabularies that give voice to marginalized groups and address blue injustices. In addition to these methods, we suggest that blue justice scholarship needs to explore cases of blue injustices and grassroots resistance movements.

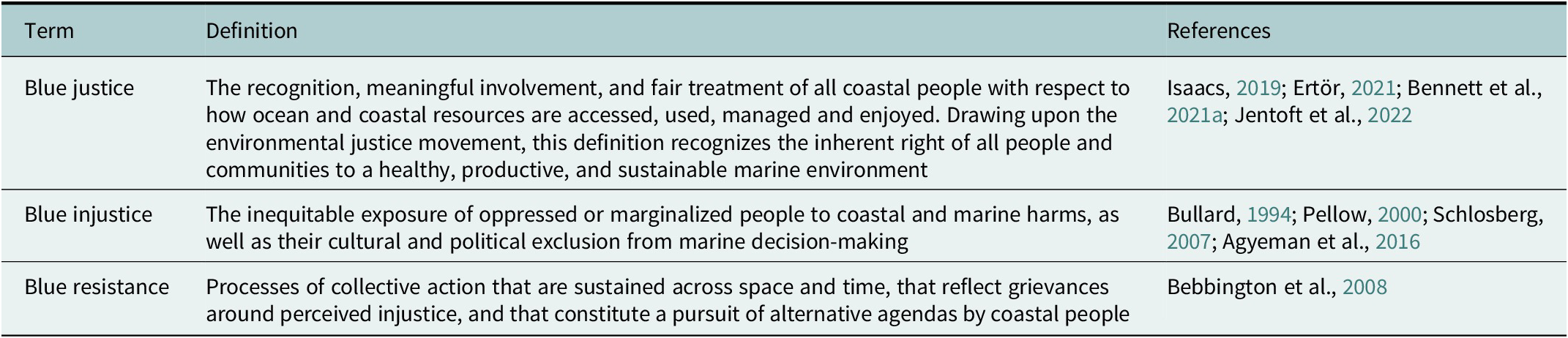

Building on this scholarship, we propose that blue justice refers to the recognition, meaningful involvement and fair treatment of all coastal people with respect to how ocean and coastal resources are accessed, used, managed and enjoyed (Table 1). This working definition is informed by the existing blue justice literature reviewed here, and the work of environmental justice scholars and activists who argue that justice includes all three elements of justice – recognition, procedure and distribution. Recognition in this context refers to acknowledging and respecting the legitimacy of rights, cultural identities, different values, worldviews, knowledge systems, ontologies, institutions and human dignity (Franks and Schreckenberg, Reference Franks and Schreckenberg2016; Zafra-Calvo et al., Reference Zafra-Calvo, Pascual, Brockington, Coolsaet, Cortes-Vazquez, Gross-Camp, Palomo and Burgess2017). Procedural justice means that people have an opportunity to meaningfully participate in and influence decisions about activities that may affect their coastal and marine environment (Franks and Schreckenberg, Reference Franks and Schreckenberg2016; Zafra-Calvo et al., Reference Zafra-Calvo, Pascual, Brockington, Coolsaet, Cortes-Vazquez, Gross-Camp, Palomo and Burgess2017). Justice in distribution means that no group of people, including current and future generations, should bear a disproportionate share of environmental harms and all should receive a fair share of the benefits of marine resources, activities, and their governance (Franks and Schreckenberg, Reference Franks and Schreckenberg2016; Zafra-Calvo et al., Reference Zafra-Calvo, Pascual, Brockington, Coolsaet, Cortes-Vazquez, Gross-Camp, Palomo and Burgess2017). We refer to this as a working definition to acknowledge that notions of justice are contextual, diverse, and evolve overtime (Gurney et al., Reference Gurney, Mangubhai, Fox, Kim and Agrawal2021).

Table 1. Key terms and definitions

Contextualizing blue injustices through a review of published case studies

A review of cases of environmental injustice can provide useful analytical entry points for understanding the complex interactions between people and marine resources, historical and structural inequalities, and various forms of social, political and economic power that introduce or perpetuate blue injustices (Martinez-Alier et al., Reference Martinez-Alier, Temper, Del Bene and Scheidel2016; Bavinck et al., Reference Bavinck, Jentoft and Scholtens2018; Ertör, Reference Ertör2021; Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Alava, Ferguson, Blythe, Morgera, Boyd and Côté2023). Indeed, “there is a need to enrich the concept [of blue justice] empirically based on how people experience and conceptualize injustice” (Jentoft and Chuenpagdee, Reference Jentoft and Chuenpagdee2022, p. 1268; Schreiber et al., Reference Schreiber, Chuenpagdee and Jentoft2022). We define blue injustice as the disproportionate exposure of marginalized people to coastal and marine harms, as well as their cultural and political exclusion from coastal and marine decision-making (Table 1). As above, this definition is informed by the work of environmental scholars who argue that justice extends beyond concerns with distributional equity, to include recognitional and procedural equity (Bullard, Reference Bullard1994; Pellow, Reference Pellow2000; Schlosberg, Reference Schlosberg2007 Reference Schlosberg). In this section, we review empirical research on three types of blue injustice to contribute to understandings of why blue injustices arise in the first place.

Hazardous waste and toxic pollution

The environmental justice movement in the United States was triggered by protests in response to the proposed dumping of 120 million pounds of hazardous waste in Warren County in 1982, the county with the highest proportion of African Americans in North Carolina (Bullard, Reference Bullard1990). Since then, decades of scholarship have shown that race is often the most significant predictor of where hazardous waste facilities are located (Mohai et al., Reference Mohai, Pellow and Roberts2009; Martinez-Alier et al., Reference Martinez-Alier, Temper, Del Bene and Scheidel2016). Patterns of unfair exposure of Black, Indigenous and other socially, politically and economically marginalized communities to hazardous waste have also been documented in marine and coastal spaces (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Alava, Ferguson, Blythe, Morgera, Boyd and Côté2023).

Oceans have long served as both a means and an end for dumping hazardous waste. Take, for example, the infamous case of the cargo ship called the Khian Sea. Loaded with thousands of tons of ash from incinerated municipal waste from the city of Philadelphia in the United States, the ship sailed around the world for nearly 2 years (1986–1988) in search of a location for dumping the toxic cargo (Pellow, Reference Pellow2007). After being refused entry into ports from the Caribbean to Western Africa, the Khian Sea eventually dumped nearly 4,000 tons of falsely labeled hazardous waste on a beach in Haiti (Pellow, Reference Pellow2007). When the Haitian government became aware that the waste was hazardous, the ship fled under cover of darkness and dumped the remaining waste somewhere in the Indian Ocean (Pellow, Reference Pellow2007). At the time, Haiti was the poorest nation in the hemisphere, while the United States was the wealthiest (Pellow, Reference Pellow2007).

Triggered by blatant examples of environmental injustice, like the case of Khian Sea, the international community adopted the Basel Convention in 1989 to stop the transnational movement and disposal of hazardous waste. Yet, today marginalized coastal communities remain a receptacle for many kinds of toxic pollution and waste. Poor countries continue to be targeted by wealthy nations’ waste brokers (Thapa et al., Reference Thapa, Vermeulen, Deutz and Olayide2022). For example, in 2006 a European-based multinational oil company called Trafigura knowingly dumped hazardous waste in the coastal city of Abidjan, Cote D’Ivoire, after their request was rejected by the Netherlands. Following the dumping, over 100,000 people experienced nausea and vomiting, 69 people were hospitalized and 15 people died (UN News, 2009). Moreover, local food security and political stability were undermined by the incident (Okafor-Yarwood and Adewumi, Reference Okafor-Yarwood and Adewumi2020). The exploitative transboundary nature of hazardous waste, from wealthy to poor nations or communities, and the blatant disregard for coastal people have led scholars to claim that “pollution is colonialism” (Liboiron, Reference Liboiron2021).

The exposure of coastal communities to toxic materials extends beyond hazardous waste dumping to include the placement of heavily polluting industries. Consider Quintero-Puchuncaví Bay, Chile, for example (Valenzuela-Fuentes et al., Reference Valenzuela-Fuentes, Alarcón-Barrueto and Torres-Salinas2021; Figure 1a). The town is referred to as a “sacrifice zone” or a place where the communities’ quality of life is knowingly compromised in the name of capitalist growth and accumulation (Valenzuela-Fuentes et al., Reference Valenzuela-Fuentes, Alarcón-Barrueto and Torres-Salinas2021; Anbleyth-Evans et al., Reference Anbleyth-Evans, Prieto, Barton, Garcia Cegarra, Muslow, Ricci, Campus and Francisca2022). The town hosts 15 heavy industries within a 5 square-mile radius, including copper smelting, an oil terminal, a coal-fired thermoelectric plant, and other refinery operations. Unsafe levels of arsenic and cadmium have been confirmed in the area (Anbleyth-Evans et al., Reference Anbleyth-Evans, Prieto, Barton, Garcia Cegarra, Muslow, Ricci, Campus and Francisca2022). During 1 month in 2018, nearly 1,400 people residents were treated for gas poisoning (Larsson, Reference Larsson2020). In addition to the negative human health consequences, pollution from these extractive industries also causes damage to marine life in the area, undermining coastal livelihoods, culture and well-being (Oyarzo-Miranda et al., Reference Oyarzo-Miranda, Latorre, Meynard, Rivas, Bulboa and Contreras-Porcia2020; Anbleyth-Evans et al., Reference Anbleyth-Evans, Prieto, Barton, Garcia Cegarra, Muslow, Ricci, Campus and Francisca2022).

Figure 1. Examples of blue injustice (a) Children playing in front of the coal-fired thermoelectric plant in Quintero-Puchuncaví Bay, which is known as one of Chile’s “sacrifice zones” (photo: Pablo Vera for Wired). (b) Oil spills out of the MV Wakashio after it was run aground on a coral reef in Mauritius on July 25, 2020, resulting in the worst oil spill to date in the Indian Ocean (photo: wiki commons).

The accumulation of toxins in seafood can also be understood as a form of blue injustice. Small-scale fishing and coastal Indigenous communities that depend on fish and seafood are often more exposed to ocean pollution than other groups (Landrigan et al., Reference Landrigan, Stegeman, Fleming, Allemand, Anderson, Backer, Brucker-Davis, Chevalier, Corra, Czerucka, Bottein and Rampal2020). For example, women in the Faroe Islands have been found to have unusually high concentrations of toxic industrial chemicals in their breast milk (Fängström et al., Reference Fängström, Strid, Grandjean, Weihe and Bergman2005). The Faroe Islands are far from the sources of industrial or chemical pollution; however, the chemicals were coming from the seafood that makes up an important part of the islanders’ diet (Fängström et al., Reference Fängström, Strid, Grandjean, Weihe and Bergman2005). Inuit women living in the Canadian Arctic have also been found to have higher levels of pollutants in their blood than the general population of Canada, predominantly due to their marine-based diet (Schaebel et al., Reference Schaebel, Bonefeld-Jørgensen, Vestergaard and Andersen2017). Exposure of Indigenous women to these toxins has been linked with breast cancer, among other health issues (Wielsøe et al., Reference Wielsøe, Tarantini, Bollati, Long and Bonefeld‐Jørgensen2020). Cancer in Marshall Islanders, resulting from exposure to nuclear weapons testing, is another example of the disproportionate exposure of marginalized coastal communities to hazardous materials (Takahashi et al., Reference Takahashi, Schoemaker, Trott, Simon, Fujimori, Nakashima and Saito2003).

Nonrenewable and renewable resource extraction

Coastal populations are often unfairly affected by the unsustainable extraction of both nonrenewable (e.g., oil and gas) and renewable (e.g., industrial fishing) resources. Extractive industries focused on nonrenewable resources, such as oil and gas, are more likely to be located in low-income and marginalized communities (Malin et al., Reference Malin, Ryder and Lyra2019). People who live near extractive industries often face acute and long-term health problems associated with these activities (Johnston and Cushing, Reference Johnston and Cushing2020). Moreover, power disparities between extractive industries and marginalized communities lead to acute procedural injustice in which local communities are unable to meaningfully participate in decisions that will shape their lives or access essential resources (Martinez-Alier et al., Reference Martinez-Alier, Temper, Del Bene and Scheidel2016). These patterns are well-documented in coastal communities (Hemmerling et al., Reference Hemmerling, DeMyers and Parfait2021).

Oil and gas extraction brings the risk of spills, which can have substantial impacts on small-scale fishers’ livelihoods and well-being in coastal communities (Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Bennett, Le Billon, Green, Cisneros-Montemayor, Amongin, Gray and Sumaila2021). In 2020, a bulk carrier called the MV Wakashio ran aground on a coral reef in Mauritius, leading to the worst ecological disaster the island nation has faced, and the worst oil spill to date in the Indian Ocean (Figure 1b). The oil spill had significant impacts on nearby coastal communities who depend on the ocean for their subsistence and livelihoods (Naggea et al., Reference Naggea, Wiehe and Monrose2021). Gender inequities within small-scale fishing communities in Mauritius were exacerbated as women gleaners, who tend to be part of the informal sector, did not automatically receive compensation following the disaster (Naggea et al., Reference Naggea, Wiehe and Monrose2021). When such environmental disasters occur in vulnerable, small island nations, it also emphasizes critical global power imbalances (Naggea and Miller, Reference Naggea and Miller2023). Small island nations like Mauritius, which have neither an oil industry nor a history of oil spills, tend to rely on external expertise for such low frequency-high risk disasters (Hebbar and Dharmasiri, Reference Hebbar and Dharmasiri2022). Moreover, while the negative social, economic and ecological impacts from an oil spill are instant, reparations may take months to years, if ever, to be fulfilled (Naggea and Miller, Reference Naggea and Miller2023).

Following the work of Latin American scholars on neo-extractivism (Svampa, Reference Svampa2015; Valenzuela-Fuentes et al., Reference Valenzuela-Fuentes, Alarcón-Barrueto and Torres-Salinas2021), we extend our review of the harms of extractive industries to those associated with renewable resource extraction, particularly to industrial fishing. Starting in the 1950s, commercial fishing has been transformed through processes of capitalization, global industrialization and intensification (Campling et al., Reference Campling, Havice and McCall Howard2012; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Longo, Clausen, Auerbach, Frey, Gellert and Dahms2019). The intensification of capture fisheries “reshaped the class dimensions in fishing and led to a highly capitalist class in fisheries dominated by a few industrial fishers” and “led to the deepening of inequalities between industrial and small-scale fishers” (Ertör, Reference Ertör2021, p. 4). For example, many fisheries management policies are based on defining, strengthening and enforcing private property rights (Campling and Havice, Reference Campling and Havice2014). In practice, these policies often allow license holders to harvest a portion – or a quota – of a total allowable catch (e.g., individual transferable quotas). These approaches tend to concentrate marine harvesting rights in the hands of a few wealthy fishers or companies and away from small-scale fishers (Nayak, Reference Nayak2021), and can be drivers of blue injustice (Isaacs, Reference Isaacs2012).

Distant water fishing fleets are another example of blue injustice. Distant water fleets are large-scale fishing fleets operating beyond the maritime boundaries of their home states. Usually, these fleets are owned by high-income countries and operate in low-income countries, which do not necessarily benefit from increased fish supplies or higher government revenues (Nash et al., Reference Nash, MacNeil, Blanchard, Cohen, Farmery, Graham, Thorne-Lyman, Watson and Hicks2022; White et al., Reference White, Baker-Médard, Vakhitova, Farquhar and Ramaharitra2022). Some of these fleets are known to operate illegally, either fishing without permits in other countries’ jurisdictional waters or hiding their position by turning off their monitoring systems. For example, a recent study documented almost 900 Chinese vessels fishing illegally in North Korean waters (Park et al., Reference Park, Lee, Seto, Hochberg, Wong, Miller, Takasaki, Kubota, Oozeki, Doshi and Midzik2020). In addition to illegal practices, distant water fleets may operate legally but in an unsustainable way by targeting overexploited fishing stocks (Nolan et al., Reference Nolan, Delabre, Menga and Goodman2022). In both cases, illegal or legal, unsustainable fishing practices can promote conflicts between international and small-scale fisheries and perpetuate blue injustices. For example, a fishing agreement between Mauritius and the European Union allows commercial fishing vessels from wealthy nations to exploit profitable stocks, while perpetuating injustices for small-scale fishers (WFFP, 2014). Moreover, the profitability of distant water fleets often relies on harmful subsidies (Skerritt and Sumaila, Reference Skerritt and Sumaila2021). Harmful subsidies reduce the costs of fuel, taxes or technology, among other costs and promote overcapacity and overfishing of the fleets far from their home states, threatening the local fisheries’ sustainability and contributing to unequal competition between small-scale fishers and industrial fishing fleets (Cisneros-Montemayor et al., Reference Cisneros-Montemayor, Sinan, Nguyen, Da Rocha, Sumaila, Skerritt, Schuhbauer, Sanjurjo and Bailey2022).

Industrial fishing is also driving blue injustices through violence and slavery (Marschke and Vandergeest, Reference Marschke and Vandergeest2016; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Longo, Clausen, Auerbach, Frey, Gellert and Dahms2019). As described by Allison et al. (Reference Allison, Ratner, Åsgård, Willmann, Pomeroy and Kurien2012, p. 15), vulnerable workers aboard commercial fishing vessels often “operate under ‘conditions akin to slavery’, exposed to physical abuse, unsafe and unsanitary conditions and are prevented from returning ashore for months or even years at a time.” Clark et al. (Reference Clark, Longo, Clausen, Auerbach, Frey, Gellert and Dahms2019) connect slavery at sea, and exploitation of children and migrant workers in processing plants, to the expansion of the global capitalist economy. They argue that the growth of fishing, aquaculture and fishmeal production provides incentives to exploit the labor of vulnerable coastal communities and is “embedded within a system predicated on the constant accumulation of capital that creates global social and ecological inequalities” (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Longo, Clausen, Auerbach, Frey, Gellert and Dahms2019, p. 195). In many low-income countries, fishing vessels operating under flags of convenience operate outside of the law, with crew members lured by promises of attractive pay and then trapped by debt (Allison et al., Reference Allison, Ratner, Åsgård, Willmann, Pomeroy and Kurien2012).

Appropriation, displacement and ocean grabbing

Appropriation describes the coercive reallocation of marine space or resources away from local communities toward foreign agents and national governments in ways that endanger local livelihoods, food security, resource rights and coastal ways of life. While the drivers of appropriation are diverse (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Johnson, McCay, Danko, Martin and Takahashi2010; Havice and Campling, Reference Havice and Campling2021), most instances are legitimized through the false narrative that customary marine tenure systems are unproductive or unsustainable (e.g., Hardin’s “tragedy of the commons” myth), and that private property regimes will promote increased efficiency, economic growth and environmental sustainability (Villamayor-Tomás and García-López, Reference Villamayor-Tomás and García-López2021). In many cases of appropriation, customary marine tenure and rights are not recognized at all (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Kaplan-Hallam, Augustine, Ban, Belhabib, Brueckner-Irwin, Charles, Couture, Eger, Fanning, Foley and Bailey2018). Appropriation can lead to the loss of access rights and/or physical displacement of certain user groups (e.g., small-scale fishers, women, Indigenous populations) or entire communities from areas that they had rights to historically (Blythe et al., Reference Blythe, Flaherty and Murray2015).

Appropriation of marine spaces and resources has been a weapon of domination since the beginning of colonial rule, and for much longer in many places (Campling and Colás, Reference Campling and Colás2018). There are many examples of appropriation during the turbulent transition from colonial rule to independence. For example, Mozambique fought for and won independence from Portugal in 1975. Two years later, the country descended into civil war. Weakened by the war and a faltering economy, the new government turned to the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund who implemented structural adjustment programmes and their associated free-market regulations, including market liberalization and privatization (Armitage et al., Reference Armitage, Andrews, Blythe, Dias, Nayak, Pittman and Sultana2021). Government licenses for natural resource extraction were sold to foreign private companies, and profits from the licenses went back to government elites, while coastal communities bore the burden of resource extraction (Armitage et al., Reference Armitage, Andrews, Blythe, Dias, Nayak, Pittman and Sultana2021). The first private shrimp farm was established in Mozambique in 1994 and produced the high-value tiger prawn (Penaeus monodon), so-called “pink gold.” The luxury shrimp were exported to European markets, while local communities were physically displaced from land that they used for making salt, an important subsistence livelihood activity (Blythe et al., Reference Blythe, Flaherty and Murray2015).

The rapid development of export-oriented shrimp aquaculture has driven the loss of access to ecological resources, deterioration of local livelihoods and loss of food security and social services (Dunaway and Macabuac, Reference Dunaway and Macabuac2007; Blythe et al., Reference Blythe, Flaherty and Murray2015). In the Philippines, the national government issued long-term leases that granted shrimp farm owners sole control over mangroves and coastal waters, which delegitimized fishers’ traditional access to these important fishing grounds (Dunaway and Macabuac, Reference Dunaway and Macabuac2007). The harmful impacts of appropriation of mangroves and coastal waters were particularly acute for women, who tend to rely on these habitats for fishing, agriculture, and handicrafts and were more exposed to diseases, pollutants and parasites spilling from intensive shrimp ponds (Dunaway and Macabuac, Reference Dunaway and Macabuac2007). The scale and scope of appropriations and dispossessions are increasing as a result of accelerating development and blue growth activities (Jouffray et al., Reference Jouffray, Blasiak, Norström, Österblom and Nyström2020; Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Blythe, White and Campero2021a).

Ocean grabbing is a term that has been applied to describe different forms of dispossession and appropriation (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Govan and Satterfield2015; Barbesgaard, Reference Barbesgaard2018). The term has been used to describe actions, “policies or initiatives that deprive small-scale fishers of resources, dispossess vulnerable populations of coastal lands, and/or undermine historical access to areas of the sea” (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Govan and Satterfield2015, p. 61). In Chile, for example, small-scale fishers have been forced out of marine spaces required for their livelihoods by the infrastructure required for desalination projects (Campero et al., Reference Campero, Bennett and Arriagada2022). Similarly, small-scale fishers have been displaced and excluded from coastal governance processes by the commodification of the Lagos Lagoon in Nigeria (Fakoya et al., Reference Fakoya, Oloko, Harper, Jentoft, Chuenpagdee, Said and Isaacs2021).

Stories like this one have played out in countries around the world, from India (Nayak, Reference Nayak2021) to Chile (Valenzuela-Fuentes et al., Reference Valenzuela-Fuentes, Alarcón-Barrueto and Torres-Salinas2021). While the specificities of each case are unique, in almost all cases the appropriation of coastal commons for economic and conservation activities, such as aquaculture or coastal tourism, has led to the displacement of marginalized communities and the dismantling of their commons arrangements, leading to negative environmental and human health, livelihood and well-being impacts (Campling and Colás, Reference Campling and Colás2018; Nayak, Reference Nayak2021).

Expanding explanations of who experiences blue justices and why blue injustices exist

Much of the early scholarship on blue justice focused on injustices experienced by small-scale fishers. In contrast, more recent writing and the empirical cases reviewed here suggest that intersecting forms of oppression and marginalization render certain coastal individuals and groups vulnerable to blue injustices (Gustavsson et al., Reference Gustavsson, Frangoudes, Lindström, Ávarez and de la Torre Castro2021; Anbleyth-Evans et al., Reference Anbleyth-Evans, Prieto, Barton, Garcia Cegarra, Muslow, Ricci, Campus and Francisca2022). For example, Indigenous women in the Arctic have higher levels of toxins in their blood than the general population (Schaebel et al., Reference Schaebel, Bonefeld-Jørgensen, Vestergaard and Andersen2017). Poor, migrant fishers are disproportionately vulnerable to slavery at sea (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Longo, Clausen, Auerbach, Frey, Gellert and Dahms2019). The impacts of the oil spill in Mauritius played out along intersecting lines of race, poverty and gender (Naggea et al., Reference Naggea, Wiehe and Monrose2021). As articulated by Ertör (Reference Ertör2021, p. 12) individuals and communities are exposed to “increased marginalization due to their ‘intersectional’ minority and ‘vulnerabilized’ identities,” which drives experiences of blue injustice. While these dynamics are often discussed alongside one another in the blue justice literature (e.g., Gustavsson et al.’s, Reference Gustavsson, Frangoudes, Lindström, Ávarez and de la Torre Castro2021 analysis of gender), we argue that future research should delve more deeply into the complex ways in “which these injustices are embedded in, inseparable from, and often exacerbated by particular conditions of social inequality, injustice and oppression that precede environmental injustice concerns” (Malin and Ryder, 2018, p. 4). Compounding blue justice issues reviewed here include transboundary inequalities, toxic seafood, energy production, Indigenous and human rights, slavery, appropriation and ocean grabbing, natural resource extraction and climate change, among others. These developments signal an expansion of the blue justice literature to a broader set of issues and affected groups.

Our review also shows that blue injustices have multiple intersecting causes, which suggests another development in the blue justice literature. With some exceptions (Ertör, Reference Ertör2021), most of the blue justice literature to date focuses on the blue economy as the central driver of blue injustice (e.g., Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Blythe, White and Campero2021a; Jentoft et al., Reference Jentoft, Chuenpagdee, Said and Isaacs2022). Yet, the cases reviewed here suggest that blue injustices have been experienced long before the blue economy and are driven by multiple processes. Drawing on the environmental justice literature, we argue that blue justice scholarship should engage more closely with intersecting drivers, including sociopolitical and racial discrimination, across historical and contemporary contexts and scales (Mohai et al., Reference Mohai, Pellow and Roberts2009). Understanding the root causes of blue injustices may help identify who is most responsible for injustice and what role they should play in reducing them.

Blue resistance: Synopsis of the blue justice movement

From pole to pole, coastal communities have long mobilized to defend their rights, to oppose harmful and extractive projects, and to reimagine their collective futures. Yet, with a few exceptions (Ertör, Reference Ertör2021), resistance efforts have been underemphasized in the blue justice scholarship, and from marine and coastal literature more broadly. Blue justice resistance movements have advanced more rapidly than their representation in the blue justice literature. In this section, we review some of the many successful examples of grassroots efforts led by coastal communities to stop their unfair exposure to environmental harms, to preserve their livelihoods and ways of life, to defend their culture and customary rights, to renegotiate power distributions and, ultimately, to propose alternative pathways.

Following scholarship on environmentalism of the poor, we aim to help center the knowledge, strength and agency of coastal communities responding to blue injustice (Nixon, Reference Nixon2011). We define blue resistance as “processes of collective action that are sustained across space and time, that reflect grievances around perceived injustice, and that constitute a pursuit of alternative agendas” by coastal people (Bebbington et al., Reference Bebbington, Bebbington, Bury, Lingan, Muñoz and Scurrah2008, p. 2892; Table 1). Resistance takes many forms and often involves complex negotiations between historical and structural inequalities and various forms of social, political and discursive power (Peet and Watts, Reference Peet and Watts2004). In this section, we review case studies of three types of blue resistance: protests, institutional tools and legislation and everyday practices.

Before moving on, we want to highlight several important caveats associated with our framing of blue resistance. First, by choosing to focus on grassroots initiatives and the strength of coastal communities, we recognize – and want to avoid – the risk of shifting the burden to respond to injustice onto already marginalized communities (Blythe et al., Reference Blythe, Silver, Evans, Armitage, Bennett, Moore, Morrison and Brown2018). We push back against neoliberal narratives that emphasize individual responsibility and absolve states of responsibility to protect their citizens (Joseph, Reference Joseph2013). Second, we want to avoid oversimplifying the complex and sometimes contested nature of resistance efforts or downplay internal conflicts within heterogeneous coastal communities (Chhotray, Reference Chhotray2016). These complexities can be illustrated, for example, by the breakdown of the World Forum of Fish Harvesters and Fish Workers network, which occurred due to irresolvable disagreements within a highly diverse global network of fish workers and harvesters (Sinha, Reference Sinha2012). Third, we have chosen to center grassroots resistance efforts in response to the underemphasis on resistance efforts in existing academic literature on blue justice and framings of vulnerability that strip coastal communities of their voice, power and agency. However, we recognize that in many instances communities do not act alone. Rather, support from other actors, including civil society groups, NGOs, academics, governments and others, are often integral to blue resistance processes and these actors feature throughout this section.

Protests

Protests, which describe public expressions of objection, are one of the most visible forms of blue resistance. For example, after decades of inaction by world leaders, Pacific Islanders are taking action to fight climate change. The Pacific Climate Warriors are a grassroots network of people from across the Pacific engaging in peaceful protests and spreading the message of strength and leadership (Figure 2a). Through a series of protests, they reject narratives that position Pacific Islanders as passive climate victims and migration as the only option to the impacts of climate-induced sea level rise, and they propose alternative futures where Pacific Islanders are warriors defending their rights to homeland and culture (McNamara and Farbotko, Reference McNamara and Farbotko2017). In addition, the Pacific Climate Warriors network is “recasting historical patriarchal figures (the male ‘warrior’) by evoking feminine characteristics, creating a blurring of gender identities” (McNamara and Farbotko, Reference McNamara and Farbotko2017, p. 17).

Figure 2. Examples of blue resistance (a) Members of the Pacific Climate Warriors protest climate inaction on the Pacific Warrior Day of Action, March 2, 2013 in Tokelau (photo: Jeff Tan Photography via 350 Pacific). (b) Members of the Coast Salish Nations lead a flotilla in protest against the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion in coastal Canada, July 16, 2018 (photo: Jennifer Gauthier).

Coastal Indigenous peoples have effectively engaged in protests in opposition to big oil (Widener, Reference Widener2018; Figure 2b). For example, on the west coast of Canada, the Northern Gateway pipeline proposal, which was to transport tar sand products from Alberta to coastal British Columbia for subsequent shipping to Asia, was met with widespread protests, many spearheaded by coastal Indigenous peoples who feared that oil spills would threaten their territories and ways of life (Veltmeyer and Bowles, Reference Veltmeyer and Bowles2014). Protests and testimony against the pipeline included arguments based on Indigenous rights, knowledge and governance authority, and were supported by environmental NGOs and civil society (Veltmeyer and Bowles, Reference Veltmeyer and Bowles2014). After a multi-year resistance effort, the proposed pipeline was ultimately canceled. In New Zealand, Māori-led protests caused the government to reverse its decision to grant offshore oil exploration rights to the Brazilian company Petrobras (O’Brien, Reference O’Brien2013). The use of small-craft flotillas to block and disrupt oil development was particularly effective as it drew on a history of successful flotilla protests against a number of blue injustices in New Zealand, including nuclear testing, toxic waste disposal and whaling, and as thus held deep emotional and symbolic meaning for the people of New Zealand (O’Brien, Reference O’Brien2013).

In 1984, small-scale fishers and their allies organized a protest in Rome during the World Conference on Fisheries Management and Development (Mathew, Reference Mathew, Jentoft, Chuenpagdee, Said and Isaacs2022). The protest was triggered by the “scale-agnostic treatment [of small-scale fisheries by the conference], in which trawlers were considered on par with canoes” (Mathew, Reference Mathew, Jentoft, Chuenpagdee, Said and Isaacs2022, p. vi). The protesters highlighted the need to protect traditional small-scale fishing grounds from the destructive practices of bottom trawlers. The protest represents one of the first times that a human rights-based approach was introduced into global fisheries discourses (Mathew, Reference Mathew, Jentoft, Chuenpagdee, Said and Isaacs2022).

The occupation of public spaces is another effective form of protest against blue injustice. For example, in 2018, close to 300 people, including local fishers and their allies, occupied the square in the city of Quintero (Chile) to protest after hundreds of people, including children, were hospitalized due to high pollution levels produced by an industrial park in one of Chile’s sacrifice zones (Valenzuela-Fuentes et al., Reference Valenzuela-Fuentes, Alarcón-Barrueto and Torres-Salinas2021). Residents of Quintero chained themselves to the pipes and buried themselves in the white ash slag (the bi-product of burning coal) from power plants in the region (Anbleyth-Evans et al., Reference Anbleyth-Evans, Prieto, Barton, Garcia Cegarra, Muslow, Ricci, Campus and Francisca2022). As with many other groups, coastal communities in Chile are not only resisting blue injustice, but they are proposing alternative visions and pathways for the future. They are calling for territorial sovereignty, the right to build their own processes of self-determination over the territories they inhabit, and practices of “buen vivir,” which center communities and the Earth, as anti-capitalist and anti-extractivist alternatives (Valenzuela-Fuentes et al., Reference Valenzuela-Fuentes, Alarcón-Barrueto and Torres-Salinas2021).

Institutional tools and legislation

Coastal communities have successfully leveraged formal and informal institutional tools and legislation to prevent, delay or stop extractive projects. In some regions, particularly where colonial legacies actively undermine the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities, coastal communities have asserted Indigenous and customary rights as a method of resistance (Ban and Frid, Reference Ban and Frid2018; Eckert et al., Reference Eckert, Ban, Tallio and Turner2018). In British Columbia, Canada, for example, the Kitasoo/Xai’xais people have drawn on their marine governance institutions, including principles of respect, reciprocity, intergenerational knowledge and interconnectedness, to resist external threats such as logging and changing fishing regulations (Ban et al., Reference Ban, Wilson and Neasloss2019). Thus, when the federal fisheries department presented new fishing regulations for the community, the hereditary chief asserted their right for self-determination in regard to harvesting decisions (Ban et al., Reference Ban, Wilson and Neasloss2019). Territorial User Rights in Fisheries (TURF) systems, which reserve spatial areas for small-scale fisheries, are enshrined in fisheries legislation in several countries and can be framed as a form of blue resistance (Gelcich et al., 2017). These types of resistance align with human rights-based approaches for fisheries governance (WFFP, 2014).

The FAO has argued that legislation provides the strongest possible framework for supporting the implementation of inclusive, participatory fisheries management policy, such as the Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Small-Scale Fisheries (FAO, 2015, 2020). As an example, the Haida Nation on Canada’s west coast successfully drew on litigative action to protect local herring stocks from a commercial fishery (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Rigg and Pinkerton2017). After decades of ongoing confrontation and negotiation, the Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations won a court case against Fisheries and Oceans Canada on the grounds that herring populations had not sufficiently recovered to support a commercial fishery and that the federal government had not negotiated an agreement with the nation based on their territorial rights (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Rigg and Pinkerton2017). The court found that there was “irreparable harm to Nuu-chah-nulth aboriginal rights because the Nuu-chah-nulth would ‘lose their position and opportunity to reasonably participate in negotiations for establishment of their constitutionally protected aboriginal rights to a community-based commercial herring fishery’” (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Rigg and Pinkerton2017, p. 158). Efforts by coastal communities also extend to influencing international arenas, with, for example, Indigenous peoples’ efforts to influence the Convention of Biological Diversity’s policy on protected areas (Corson et al., Reference Corson, Gruby, Witter, Hagerman, Suarez, Greenberg, Bourque, Grayh and Campbell2014). In Chile, fisher-led social movements have argued for the need to create laws for regulating marine pollution (Anbleyth-Evans et al., Reference Anbleyth-Evans, Prieto, Barton, Garcia Cegarra, Muslow, Ricci, Campus and Francisca2022).

Coastal communities have also drawn on combinations of institutional tools and legislation to resist blue injustice. In Ngarchelong, Palau, for example, chiefs and fishers implemented a customary ban on sea cucumber harvesting when an illegal fishery threatened overexploitation and violated their social norms and cultural values (Ferguson et al., Reference Ferguson, Bennett, Kostka, Richmond and Singeo2022). The national government quickly followed and passed a law banning the export of sea cucumber, which stopped the harvest nationwide (Ferguson et al., Reference Ferguson, Bennett, Kostka, Richmond and Singeo2022). These examples highlight how formal and informal institutional tools and legislative actions can support blue resistance efforts.

Everyday practices of resistance

Power to resist blue injustice is shaped by preexisting social inequality and deprivation. Many marginalized individuals and groups cannot engage in resistance. In his book “Weapons of the Weak,” anthropologist James Scott (Reference Scott1985) argues that subordinate classes have rarely been afforded the luxury of open, organized, and political activity. Speaking about the climate justice context for many minority communities in the United States, Ayana Elizabeth Johnson (Reference Johnson2020) says “it’s very hard to focus on the climate crisis when you’re dealing with the crisis of state-sanctioned violence and mass incarceration, and your friends and family being at risk for being murdered by the police for no reason, and fighting for your basic rights to live and breathe. That is the priority, unfortunately, for many communities, which means there are people who are not able to focus on being a part of climate solutions even though they care.” For some of these groups, blue resistance can take less visible forms, which can be referred to as everyday practices of resistance.

Food has been a way for communities to practice everyday resistance (Agyeman et al., Reference Agyeman, Schlosberg, Craven and Matthews2016). For example, local communities have used community gardens as a tool to attain food security, to resist industrialized food systems that discriminate against poor and marginalized groups, and to propose alternative food systems where inclusive and sustainable practices flourish (Agyeman et al., Reference Agyeman, Schlosberg, Craven and Matthews2016). In coastal and marine spheres, communities have asserted power through blue foods (Jonas, Reference Jonas2021). For example, the cultural practice of potlatch redistributes surplus food within First Nations communities on Canada’s Pacific coast outside of capitalist market systems and beyond the prescriptions of government welfare systems (Veltmeyer and Bowles, Reference Veltmeyer and Bowles2014). The active management of intertidal clam beds by Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Coast of North America could be described as another example of everyday resistance against colonial injustices and as a powerful way to maintain coastal ways of life and culture (Deur et al., Reference Deur, Dick, Recalma-Clutesi and Turner2015). In 2021, people from across Asia and the Pacific, including small-scale fishers, coalesced around the Peoples’ Autonomous Response to the United Nations Food Systems Summit and called for a radical transformation from industrial corporate food systems toward one rooted in local food sovereignty (Jonas, Reference Jonas2021). In these ways, traditional and local food systems could be described as acts of resistance to blue injustices associated with colonization and industrialization of coastal food systems.

Establishment of, and participation in, alternative economic models can be another everyday act of resistance. In the eastern United States, for example, small-scale fishers are engaging in community-supported fisheries as a method for reclaiming their food security, autonomy, self-empowerment, and a more equitable share of the profits from their catch (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Boucquey, Stoll, Coppola and Smith2014). Community-supported fisheries connect consumers more closely with fishers by allowing the consumer to subscribe to the harvest of a fisher or group of fishers, thus cutting out middle-men who draw income away from local communities (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Boucquey, Stoll, Coppola and Smith2014).

Women are often at the core of everyday practices of blue resistance (Gustavsson et al., Reference Gustavsson, Frangoudes, Lindström, Ávarez and de la Torre Castro2021). In 1937, the Chacahua-Pastoría lagoons, located on the Pacific coast of Oaxaca, Mexico, were declared a federally protected area, which meant that Black and Indigenous communities were left without legal ownership and with limited ability to practice traditional stewardship (Rodríguez Aguilera, Reference Rodríguez Aguilera2022). Eighty years later, the lagoons were hit by a 7.1 magnitude earthquake, which caused massive die-off of marine life within the lagoon (Rodríguez Aguilera, Reference Rodríguez Aguilera2022). In the aftermath of the earthquake, and in the context of colonial and racist legacies, Black and Indigenous women sustained their communities through growing medicinal plants, cooking food, taking care of children, domestic animals and plants, fishing for family consumption and engaging in lagoon stewardship (Rodríguez Aguilera, Reference Rodríguez Aguilera2022). Rodríguez Aguilera (Reference Rodríguez Aguilera2022) asserts that these acts of care, solidarity and reciprocity are forms of everyday resistance to injustice. In the Pacific, female Pacific Climate Warriors engage in prayer, kinship and connections to ancestors as everyday practices of resistance in the face of growing blue injustices (McNamara and Farbotko, Reference McNamara and Farbotko2017).

Mainstreaming blue resistance efforts

In responses to blue injustices, coastal communities have engaged in grassroots resistance efforts, including protests, institutional and legislative actions and everyday resistance against destructive and discriminatory practices in ocean and coastal spaces. In the words of Ertör (Reference Ertör2021, p. 25), “[a]lthough they are utterly marginalized and made almost invisible by national, regional, and global policies in many places, they continue to organize, form alliances, and are able to stop part of the projects they fight against.” Here, we highlight several key findings from our review of blue resistance case studies.

First, our review shows that blue resistance movements can effectively stop or prevent injustices. For example, Indigenous-led opposition to the Northern Gateway pipeline in Canada was the deciding factor in the federal government’s rejection of the pipeline (Veltmeyer and Bowles, Reference Veltmeyer and Bowles2014). In New Zealand, Māori flotilla prevented offshore oil extraction (O’Brien, Reference O’Brien2013). Across the Pacific, traditional canoes have become a powerful symbol of postcolonial unity and resistance (McNamara and Farbotko, Reference McNamara and Farbotko2017).

Next, our review suggests that blue resistance movements are diverse, dynamic, and can take many forms. We show that the blue justice movement includes Pacific Islanders who peacefully protest blue injustice stemming from climate inaction, reject labels of passive climate victims, and reimagine Pacific futures (O’Brien, Reference O’Brien2013; McNamara and Farbotko, Reference McNamara and Farbotko2017; Ferguson et al., Reference Ferguson, Bennett, Kostka, Richmond and Singeo2022). It also encompasses diverse Indigenous communities concerned with the protection of their culture and the livelihoods and welfare of community members and their territorial rights and ways of living that are predicated on a relationship of harmony with the coastal environment (Veltmeyer and Bowles, Reference Veltmeyer and Bowles2014; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Rigg and Pinkerton2017; Ban and Frid, Reference Ban and Frid2018; Eckert et al., Reference Eckert, Ban, Tallio and Turner2018; Ban et al., Reference Ban, Wilson and Neasloss2019), as well as small-scale fishers and their allies, including civil society organizations, who resist class exploitation, the industrialization of fisheries, and their exclusion from ocean governance processes form another essential component of the blue justice movement (Valenzuela-Fuentes et al., Reference Valenzuela-Fuentes, Alarcón-Barrueto and Torres-Salinas2021; Jentoft et al., Reference Jentoft, Chuenpagdee, Said and Isaacs2022). Our review also highlights women who engage in overt acts of resistance and everyday practices of care, solidarity and reciprocity are central to the movement (McNamara and Farbotko, Reference McNamara and Farbotko2017; Rodríguez Aguilera, Reference Rodríguez Aguilera2022). Thus, the base of the blue justice movement is highly diverse. We argue the movement is broader than that described by much of the existing academic scholarship, which focuses primarily on the injustice experienced by small-scale fishers.

Finally, this review builds on existing blue justice scholarship by arguing that blue justice is about more than experiences of injustice and practices of resistance; it is also about creation, and the imagination and implementation of alternative coastal futures. In Chile, communities are advancing notions of “buen vivir” as anti-capitalist alternatives to extractivist development (Valenzuela-Fuentes et al., Reference Valenzuela-Fuentes, Alarcón-Barrueto and Torres-Salinas2021). In Canada, First Nations are asserting Indigenous values and management systems for fisheries (Ban et al., Reference Ban, Wilson and Neasloss2019). For many coastal communities, blue justice is about proposing interconnectedness with coastal seascapes as an alternative epistemology to powerful Western narratives which frame people as separate from the sea (Ingersoll, Reference Ingersoll2016). We argue communities’ creation of alternative coastal futures has been underemphasized in the blue justice and coastal and marine literature. Our review highlights that blue resistance efforts are effective, diverse and are proposing alternative futures. Going forward, centering these efforts into academic research and policy circles is an important area for future scholarship.

Conclusion

Looking forward, we can be confident that drivers of blue injustice will continue to accelerate; as will grassroots campaigns for blue justice. In this context, realizing and supporting blue justice will require a collaborative and multi-pronged approach. First and foremost, the blue justice movement is led by grassroots communities. Academics can support coastal communities in pursuing blue justice by coproducing sound and inclusive science describing the root causes of injustice faced by coastal communities, helping to develop solutions, and assessing their effects (Chuenpagdee et al., Reference Chuenpagdee, Isaacs, Bugeja-Said, Jentoft, Jentoft, Chuenpagdee, Said and Isaacs2022). Our review suggests that early blue justice literature focused on securing rights for small-scale fisheries in the context of the blue economy, while more recent literature is exploring intersecting forms of oppression and marginalization render certain coastal individuals and groups vulnerable and multiple drivers of blue injustices. We also show that grassroots resistance efforts can effectively stop or prevent injustices, that blue resistance movements are diverse, and that communities are suggesting alternative pathways to realizing blue justice. Governments, civil society organizations and NGOs can support community efforts through changes in funding systems, the devolution of decision-making power, and the adoption of ocean governance institutions that secure local rights and access to marine resources (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Katz, Yadao-Evans, Ahmadia, Atkinson, Ban, Dawson, de Vos, Fitzpatrick, Gill, Imirizaldu and Wilhelm2021b). Mainstreaming justice in coastal policy and practice across scales, and accepting communities’ requests for recognitional and procedural justice is essential (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Katz, Yadao-Evans, Ahmadia, Atkinson, Ban, Dawson, de Vos, Fitzpatrick, Gill, Imirizaldu and Wilhelm2021b). Ultimately, concerted efforts are needed by all to support and empower coastal communities to reject blue injustices and to achieve their diverse aspirations for blue justice now and into the future.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/cft.2023.4.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cft.2023.4.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the synthesis center CESAB of the French Foundation for Research on Biodiversity for facilitating a convening space for the authors to develop this work.

Author contributions

J.L.B. developed the main conceptual ideas for the paper with critical input from D.A.G., J.C., N.J.B. and G.G.G. All authors contributed to the review and provided critical feedback on the main conceptual ideas that shaped the current paper. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Financial support

This work is supported by the Blue Justice group funded by the synthesis center CESAB of the French Foundation for Research on Biodiversity (FRB; www.fondationbiodiversite.fr).

Competing interest

The authors declare none.

Comments

Dear Members of the Editorial Board,

We are pleased to submit our invited manuscript entitled "Blue Justice: Evidence of a Global Movement" for review.

In this Overview Review article, we take stock of the relatively new term 'blue justice'. The term was introduced into academic discourse in 2018; and while the concept of blue justice is expanding rapidly (as a counter-narrative to blue economy initiatives), its meaning, scope, and application are still emerging and warrant review. We review instances of blue injustices occurring across the planet and then highlight some of the many successful examples of grassroots resistance efforts to blue injustices. We argue that together, these cases testify to a global blue justice movement, led by Pacific Islanders, Indigenous peoples, small-scale fishers, and women, among other, who are not only resisting blue injustice, but are proposing alternative coastal futures.

We believe our review will make an important contribution to Cambridge Prisms: Coastal Futures for several reasons. First, our review provides the first global overview of the blue justice movement. Second, it adds to the existing literature by: 1) showing that blue justice responds to a broader suite of drivers than the blue economy alone; and, 2) demonstrating that the blue justice movement is more diverse than the small-scale fisheries community (which is how it is described in much of the existing literature). Finally, the paper deepens our understanding of how to realize more equitable coastal futures.

Thank you for inviting and considering our submission.

Sincerely,

Jessica Blythe