Emotion regulation is an important component of everyday life. Successfully modulating or altering when and how we express emotions significantly influences our social lives and how we experience and engage with the world around us. Deficits in emotion regulation often underlie many common psychological conditions, including depression and drug and alcohol use disorders (Beauchaine & Cicchetti, Reference Beauchaine and Cicchetti2019; Cole & Hall, Reference Cole, Hall, Beauchaine and Hinshaw2008; Garland et al., Reference Garland, Bell, Atchley and Froeliger2020), and some suggest that emotion dysregulation perpetuates intergenerational manifestations of psychopathology within families (e.g., Han & Shaffer, Reference Han and Shaffer2013; Han et al., Reference Han, Lei, Qian, Li, Wang and Zhang2016; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Kaliush, Conradt, Terrell, Neff, Allen, Smid, Monk and Crowell2019), particularly among parents with psychiatric conditions that are associated with emotion (e.g. Cheetham et al., Reference Cheetham, Allen, Yücel and Lubman2010). Thus, given its importance in influencing our well-being and its ubiquity in our lives, it is necessary to understand the developmental roots of and processes through which emotion regulation emerges, particularly among families at pronounced risk for emotion-regulation difficulties.

Since early emotion-regulation problems can alter an individual’s mental health trajectory, significant interest has surrounded emotion regulation’s influences on children’s well-being and psychological functioning (e.g., Compas et al., Reference Compas, Jaser, Bettis, Watson, Gruhn, Dunbar and Thigpen2017; McRae et al., Reference McRae, Gross, Weber, Robertson, Sokol-Hessner, Ray, Gabrieli and Ochsner2012; Pitskel et al., Reference Pitskel, Bolling, Kaiser, Crowley and Pelphrey2011). One important and distinct aspect of emotion regulation (Derryberry & Rothbart, Reference Derryberry and Rothbart1988; Putnam & Rothbart, Reference Putnam and Rothbart2006) is emotional reactivity which has been defined as “the extent to which individuals experience emotions, respond to a variety of emotional stimuli, the intensity of the response, and the duration of arousal” (Shapero et al., Reference Shapero, Dale, Archibald, Pedrelli and Levesque2018, p. 2). From a developmental perspective, the development of emotional reactivity is a complex and dynamic process, one that is highly influenced by many multifaceted individual and environmental factors (Braungart-Rieker et al., Reference Braungart-Rieker, Hill-Soderlund and Karrass2010). Emotional reactivity is often characterized as frequent and intense in infancy and early childhood, when children typically lack independent emotion-regulation capacities (Kopp, Reference Kopp1989). Infants and toddlers may be highly responsive to emotional stimuli and therefore may be highly reactive to people, situations, and events in their environments. Infants, for example may display frequent and intense distress and feelings of hunger, sadness, or fear. As they receive greater exposure to and familiarity with emotional stimuli, and as their independent regulatory capacities and coping strategies broaden in early childhood, emotional reactivity may naturally decrease (Somerville & Casey, Reference Somerville, Casey, Gazzaniga and Mangun2014). Importantly, unlike previous developmental periods, middle childhood may bring with it increased abilities to understand, process, express, and respond to complex and nuanced emotions, like shame and empathy specifically since cognitive abilities, which also facilitate and underlie emotions and behaviors, rapidly develop from infancy to middle childhood (Harter, Reference Harter1986; LeDoux, Reference LeDoux1989). Consequently, young children are increasingly able to recognize, process, and understand others’ emotions, emotional stimuli and situations, but also their own emotional repertoire and patterns of responding in and coping with distinct emotional settings (Band & Weisz, Reference Band and Weisz1988; Campos et al., Reference Campos, Campos and Barrett1989; Creasey et al., Reference Creasey, Ottlinger, Devico, Murray, Harvey and Hesson-McInnis1997; Fischer et al., Reference Fischer, Shaver and Carnochan1990). For example, children may recognize feeling heightened levels of fear or nervousness at home (or in the presence of family conflict), and they may employ specific coping strategies to address those feelings in that context, while recognizing feelings of happiness in a different setting.

Importantly, individual differences impact the nature and trajectory of the development of emotional reactivity processes (Mauss et al., Reference Mauss, Levenson, McCarter, Wilhelm and Gross2005; Noroña-Zhou & Tung, Reference Noroña-Zhou and Tung2021). Specifically, there is much variability in the factors that influence the development and trajectory of emotional reactivity (Calkins, Reference Calkins1994; Cole et al., Reference Cole, Zahn-Waxler, Fox, Usher and Welsh1996; Davidson, Reference Davidson1998; Eman et al., Reference Eman, Khalid and Nicolson2019; Panlilio et al., Reference Panlilio, Harring, Harden, Morrison and Duncan2020; Picoito et al., Reference Picoito, Santos and Nunes2021), with age and developmental period and developmental environment being some of the common factors that have been studied (Banerjee, Reference Banerjee1997; Lincoln et al., Reference Lincoln, Russell, Donohue and Racine2017; Picoito et al., Reference Picoito, Santos and Nunes2021; Sanchis-Sanchis et al., Reference Sanchis-Sanchis, Grau, Moliner and Morales-Murillo2020; Zimmer-Gembeck & Skinner, Reference Zimmer-Gembeck and Skinner2016). Much heterogeneity and variability also exist within the construct of emotional reactivity, including (A) how, why, and when individuals experience emotions; (B) why the type, intensity, and duration of emotion differs from person to person; and (C) why some individuals – based on their emotional reactivity – might be at heightened risk for psychopathology (e.g., Nock et al., Reference Nock, Wedig, Holmberg and Hooley2008). This work demonstrates the utility in parsing traditional or typical notions of the development of emotional reactivity, by delineating specific predictors, mechanisms, and trajectories or pathways that might influence children’s emotional reactivity.

Early childhood may be a particularly salient developmental period for emotion-regulation development. Young children typically rely on others (primarily caregivers) for emotion-regulation support since they are developmentally incapable of independently and consistently modulating their own emotions (Crockenberg & Leerkes, Reference Crockenberg and Leerkes2004; Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Cumberland and Spinrad1998; Kopp, Reference Kopp1989). Consequently, very young children may have a limited repertoire of independent regulatory strategies available to enact during times of intense of emotional arousal. During early childhood (between ages 2 and 5), children become more adept at understanding, processing, and internalizing contextual norms around emotional expressions – including the social desirability or appropriateness of certain emotions when expressed in certain places or around certain people (e.g., caregivers) (Banerjee, Reference Banerjee1997). These socially and contextually-influenced emotional display norms may confer to children that emotions and emotional expressions function to facilitate social connections and relationship bonds (e.g., children may learn that crying elicits sensitive responses from caregivers, which may help children feels emotionally secure and connected to their parents) (Cole & Jacobs, Reference Cole and Jacobs2018; Gross & Ballif, Reference Gross and Ballif1991). As children gain more experience expressing emotions and navigating emotional contexts, internalization of these emotional display norms may encourage children to independently regulate their emotions and effectively navigate emotional contexts (Cole & Jacobs, Reference Cole and Jacobs2018). This motivation may be particularly strong for young children who experience emotion-related stress or trauma, such as emotional abuse or neglect since harmful or insensitive caregiver responses to their emotional needs may evoke, intensify, or prolong negative emotions like sadness or anger (Leerkes et al., Reference Leerkes, Nayena Blankson and O’Brien2009). For these children, certain patterns of emotional reactivity may reflect intense and/or prolonged dysregulated emotional reactions to environmental stress (Davies & Martin, Reference Davies and Martin2013; Davies et al., Reference Davies, Cummings and Winter2004). In other words, distressing experiences with caregivers or within a family’s emotional climate (e.g., receiving frequent emotional invalidations from parents or receiving messages that your emotions do not matter) may impact children’s emotional reactivity (e.g., Buckholdt et al., Reference Buckholdt, Parra and Jobe-Shields2014; Denham et al., Reference Denham, Mitchell-Copeland, Strandberg, Auerbach and Blair1997; Shenk & Fruzzetti, Reference Shenk and Fruzzetti2011), with some children possibly displaying frequent, intense emotions (e.g., Miu et al., Reference Miu, Szentágotai-Tătar, Balazsi, Nechita, Bunea and Pollak2022) while others may display more muted, controlled, and less intense displays (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Schaller, Fabes, Bustamante, Mathy, Shell and Rhodes1988, Reference Eisenberg, Fabes, Schaller, Carlo and Miller1991, Reference Eisenberg, Fabes, Carlo, Troyer, Speer, Karbon and Switzer1992; Fabes et al., Reference Fabes, Leonard, Kupanoff and Martin2001). Moreover, during early childhood, theory-of-mind develops and children begin to view themselves as distinct emotional beings from other people, including caregivers (Grolnick et al., Reference Grolnick, McMenamy and & Kurowski1999; Stack & Lewis, Reference Stack and Lewis2008; Stack & Poulin-Dubois, Reference Stack, Poulin-Dubois, Pushkar, Bukowski, Schwartzman, Stack and White1998). When considered together, young children may begin to internalize caregivers as sources of emotional distress who may be unreliable or ineffective external emotion regulators and thereby be more motivated to regulate their own emotions (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Cumberland and Spinrad1998).

Young children (infants and toddlers) may also lack the verbal and linguistic ability to articulate their emotions or (importantly) what they need in order to effectively regulate, process, or address their emotions (e.g., they cannot ask for a hug or tell someone that they are sad or scared) (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Armstrong, Pemberton, Calkins and Bell2010; Roben et al., Reference Roben, Cole and Armstrong2013). Also in early childhood, developmental advancements in other elements of cognition and self-regulation, including executive functioning and inhibitory further enable expressive suppression. Interestingly, even before age 2, children start to gauge the authenticity and congruence of both positive and negative emotional expressions in other children and adults (Serrat et al., Reference Serrat, Amadó, Rostan, Caparrós and Sidera2020; Sidera et al., Reference Sidera, Amadó and Serrat2013; Walle & Campos, Reference Walle and Campos2014). Thus, early on, children may not only start detecting emotional (in)congruence in others’ expressions, but may also begin learning that inauthentic or incongruent expressions may serve a social or behavioral function (Pala & Lewis, Reference Pala and Lewis2021; Walle & Campos, Reference Walle and Campos2014). This builds on prior work that demonstrates that toddlers (e.g., 3- and 4-year-olds) can differentiate discrete emotions (e.g., understand the difference between fear, sadness, anger, etc.) and they may also understand the utility or benefit of using different emotion-regulation strategies when modulating discrete emotions (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Dennis, Smith-Simon and Cohen2009). For example, Berlin and Cassidy (Reference Berlin and Cassidy2003) found that preschool-aged children whose mothers were more controlling and less receptive to their emotional expressions were ultimately less likely to display emotions or share their feelings with their mother; this may further indicate that even before middle childhood, children may modulate or alter their emotional reactions based on information from their surrounding environment, including prior experiences they may have had with caregivers that impacted their sense of safety, security, and freedom to express their emotions (e.g., Davies et al., Reference Davies, Winter and Cicchetti2006). When collectively considered, these factors illustrate that infants and toddlers are capable of concealing emotions, dampening their emotional reactivity, and initiating less cognitively demanding behavioral regulation strategies, like emotional suppression (or masking) compared to older children who are better able to leverage more sophisticated and cognitively involved regulatory strategies.

Family environments and interactions with caregivers play major roles in the development of emotion regulation among young children (Eisenberg & Fabes, Reference Eisenberg, Fabes and Clark1992b; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers and Robinson2007). Parenting behaviors, family dynamics, and overall family emotional climate have been shown to impact children’s emotional lives and experiences, and consequently, the way they process, modulate, and express emotions (e.g., (Bariola et al., Reference Bariola, Gullone and Hughes2011; Criss et al., Reference Criss, Morris, Ponce‐Garcia, Cui and Silk2016; Lambie & Lindberg, Reference Lambie and Lindberg2016; Lavi et al., Reference Lavi, Katz, Ozer and Gross2019; Little & Carter, Reference Little and Carter2005; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Criss, Silk and Houltberg2017; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Morris, Heller, Scheeringa, Boris and Smyke2009). Psychopathology within the family, particularly among primary caregivers can directly and indirectly undermine children’s emotion regulation development and emotional well-being in complex and unique ways (Enlow et al., Reference Enlow, Kitts, Blood, Bizarro, Hofmeister and Wright2011; Han et al., Reference Han, Lei, Qian, Li, Wang and Zhang2016; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers and Robinson2007; Seddon et al., Reference Seddon, Abdel-Baki, Feige and Thomassin2020; Shadur & Hussong, Reference Shadur and Hussong2020; Shaffer et al., Reference Shaffer, Suveg, Thomassin and Bradbury2012; Suveg et al., Reference Suveg, Shaffer, Morelen and Thomassin2011; van der Pol et al., Reference van der Pol, Groeneveld, Endendijk, van Berkel, Hallers-Haalboom, Bakermans-Kranenburg and Mesman2016). Interestingly, less research has examined distinct elements of emotion regulation – such as emotional reactivity – or the processes through which they manifest among children of mothers with alcohol dependence symptoms. Thus, it remains unclear how parents’ substance use problems may impact emotional reactivity in children from these family environments.

The present study was designed to clarify lingering unknowns about links between maternal alcohol dependence symptoms, parenting, and children’s emotional reactivity. Given known associations between maternal substance use and insensitive caregiving during emotional parent-child situations (e.g., Jacques et al., Reference Jacques, Sturge-Apple, Davies and Cicchetti2021), and given the salience of maternal responsivity to children’s long-term emotional development and well-being (e.g., Leerkes et al, Reference Leerkes, Nayena Blankson and O’Brien2009), maternal insensitivity to children’s emotional distress (expressions of vulnerable emotions like sadness or fear) was examined as a mediator of the relationship between maternal alcohol dependence symptoms and child emotional reactivity. Additionally, several theoretical and conceptual frameworks are discussed in tandem to better unpack how parent alcohol dependence symptoms and family risk factors may influence the developmental processes of emotional reactivity within young children.

Theoretical approaches to studying child emotional reactivity

Several prominent theories on emotion regulation exist and have been used within and across disciplines to bolster our understanding of emotional development and well-being during early childhood. Within the child development field, the main theories are based on familial and contextual influences on the development of emotion regulation and emotional reactivity (e.g., Morris et al., Reference Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers and Robinson2007; Thompson & Meyer, Reference Thompson, Meyer and Gross2007). According to emotion socialization perspectives and similar conceptual frameworks (e.g., Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Cumberland and Spinrad1998; Maccoby, Reference Maccoby, Parke, Ornstein, Rieser and Zahn-Waxler1994; Paley & Hajal, Reference Paley and Hajal2022), children’s regulatory skills are largely molded by parents’ behaviors, specifically through their emotional expressions, responses to children’s emotions, and how they discuss and describe emotions to children (Chaplin et al., Reference Chaplin, Cole and Zahn-Waxler2005; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Raikes, Virmani, Waters and Thompson2014). Specifically, parents’ emotional displays model different ways to express emotions, such as yelling when angry or crying when sad, and they also convey the types of emotional expressions that might be appropriate to display in that situation or setting (Boyum & Parke, Reference Boyum and Parke1995; Cole et al., Reference Cole, Dennis, Smith-Simon and Cohen2009; Denham et al., Reference Denham, Mitchell-Copeland, Strandberg, Auerbach and Blair1997; Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Cumberland and Spinrad1998). These parental behaviors, also known as socialization behaviors, help teach children about how emotions function and their role and importance via a broad array of social interactions (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Dennis, Smith-Simon and Cohen2009). Aside from modeling, children may also internalize messages about emotions and their appropriateness from parents’ responses to their emotions (Banerjee, Reference Banerjee1997; Berlin & Cassidy, Reference Berlin and Cassidy2003). Maladaptive or insensitive caregiving behaviors, such as ignoring a child’s emotional needs or punishing a child for expressing emotions may instill harmful messages about emotions and undermine children’s comfort with their emotions and how they express them (Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Halberstadt, Castro, MacCormack and Garrett-Peters2016). Similarly, children whose parents seem less emotionally available or present to sensitively respond to children’s emotions may, over time, demonstrate decreased emotional competence and well-being (Diener et al., Reference Diener, Mangelsdorf, McHale and Frosch2002; Volling et al., Reference Volling, McElwain, Notaro and Herrera2002). This may negatively alter the trajectory of children’s development of emotion regulation and increase their risk of psychological, behavioral, and social problems (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Spinrad and Eggum2010).

Importantly, parents with mental health or substance use problems may engage in maladaptive socialization behaviors that ultimately harm children’s emotional well-being and may undermine children’s emotional development (Jacques et al., Reference Jacques, Sturge-Apple, Davies and Cicchetti2021; Seddon et al., Reference Seddon, Abdel-Baki, Feige and Thomassin2020). Substance use interferes with emotional functioning, which puts parents with substance use disorders at high risk to experience significant struggles navigating emotions and contexts in which emotions are elicited, such as times when children are highly emotional and seeking emotional support from caregivers (Frigerio et al., Reference Frigerio, Porreca, Simonelli and Nazzari2019; Goldman Fraser et al., Reference Goldman Fraser, Harris-Britt, Leone Thakkallapalli, Kurtz-Costes and Martin2010; Porreca et al., Reference Porreca, Biringen, Parolin, Saunders, Ballarotto and Simonelli2018; Rossen et al., Reference Rossen, Mattick, Wilson, Clare, Burns, Allsop, Elliott, Jacobs, Olsson and Hutchinson2019). Parents with substance use disorders have been shown to be dismissive, neglectful or disengaged, and harsh during emotional parent-child interactions, such as when responding to children’s emotional needs (e.g., Breaux et al., Reference Breaux, Harvey and Lugo-Candelas2016; Jacques et al., Reference Jacques, Sturge-Apple, Davies and Cicchetti2021; Shadur & Hussong, Reference Shadur and Hussong2020). Others have found that these parents may struggle to accurately identify and/or fully process their own and others’ emotions due to substance-related neurological deficits (e.g., Kim et al., Reference Kim, Iyengar, Mayes, Potenza, Rutherford and Strathearn2017; Rutherford & Mayes, Reference Rutherford and Mayes2017). Collectively considered, these findings imply that parents with symptoms of substance use disorders may struggle to help children’s optimal development of emotion regulation which may negatively affect how children experience and express emotions and thereby increase their risk for future psychosocial problems.

Parental influence on the development of emotional reactivity during early childhood

Parental insensitivity to children’s emotional experiences may be uniquely detrimental to children’s emotional development and well-being, particularly in early childhood (Fabes et al., Reference Fabes, Leonard, Kupanoff and Martin2001; Leerkes et al., Reference Leerkes, Nayena Blankson and O’Brien2009, Reference Leerkes, Weaver and O’Brien2012; Lyons-Ruth et al., Reference Lyons-Ruth, Bureau, Easterbrooks, Obsuth, Hennighausen and Vulliez-Coady2016; Roberts & Strayer, Reference Roberts and Strayer1987). Insensitivity is often all-encompassing construct that includes caregiving behaviors that are inappropriately attuned to their child’s needs, interests, or capabilities (Ainsworth & Wittig, Reference Ainsworth, Wittig and Foss1969; Bretherton, Reference Bretherton2016). Insensitivity to children’s expressions of vulnerable emotions, such as sadness, fear, worry, and others that indicate emotional vulnerability may be particularly hurtful and could erode children's trust, confidence, or emotional security in their caregivers or family environments (Berlin & Cassidy, Reference Berlin and Cassidy2003; Leerkes et al., Reference Leerkes, Nayena Blankson and O’Brien2009). Children may internalize insensitive reactions, such as parental emotional disengagement to mean that their emotions are invalid, unwanted, undeserving of attention or support, which essentially fractures children’s relationship with their emotions and their view of themselves as emotional beings (Lambie & Lindberg, Reference Lambie and Lindberg2016). These reactions may negatively influence children’s emotional development and well-being (Krause et al., Reference Krause, Mendelson and Lynch2003; Shipman et al., Reference Shipman, Schneider, Fitzgerald, Sims, Swisher and Edwards2007). Studies have shown that mothers with mental health challenges may be less responsive, warm, or sensitively attuned to young children’s emotional needs which may subsequently harm their psychosocial well-being (e.g., Dix & Yan, Reference Dix and Yan2014; Garai et al., Reference Garai, Forehand, Colletti, Reeslund, Potts and Compas2009; Jacques et al., Reference Jacques, Sturge-Apple, Davies and Cicchetti2021; Maughan et al., Reference Maughan, Cicchetti, Toth and Rogosch2007; Norcross et al., Reference Norcross, Leerkes and Zhou2017; Velleman & Templeton, Reference Velleman and Templeton2007). Thus, given the high risk for parents with psychological and substance use disorders (including alcohol use disorders) to engage in insensitive caregiving (Jacques et al., Reference Jacques, Sturge-Apple, Davies and Cicchetti2021; Mayes & Truman, Reference Mayes and Truman2002; Velleman & Templeton, Reference Velleman and Templeton2007) and given the negative developmental outcomes associated with this type of caregiving (Lyons-Ruth et al., Reference Lyons-Ruth, Bureau, Easterbrooks, Obsuth, Hennighausen and Vulliez-Coady2016; McElwain & Booth-LaForce, Reference McElwain and Booth-LaForce2006), it remains important to further examine these processes among young children of mothers with histories of alcohol and substance use problems and substance use disorders.

Morris et al. (Reference Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers and Robinson2007) and others expound on familial and contextual-based theories of emotion regulation development by emphasizing the broader role family context plays on children’s emotion regulation development. Recent work has recognized the need to better integrate and discuss context since different families have different expectations and working models/standards of emotional expressions, and the benefits and consequences of expressing emotions also vary within and across families (Aldao et al., Reference Aldao, Sheppes and Gross2015; Aldao, Reference Aldao2013; English et al., Reference English, Lee, John and Gross2017). For example, children may learn that expressing sadness around emotionally insensitive parents may yield backlash or punishment while expressing those emotions around siblings elicits emotional support and comfort (e.g., Grolnick et al., Reference Grolnick, Bridges and Connell1996; Roque et al., Reference Roque, Veríssimo, Fernandes and Rebelo2013). Other work has examined family context as an ecosystem in which emotion regulation develops by focusing on types of family risk that may threaten children’s emotion regulation and emotional expression (e.g., Carreras et al., Reference Carreras, Carter, Heberle, Forbes and Gray2019; Davies et al., Reference Davies, Winter and Cicchetti2006; Grolnick et al., Reference Grolnick, Bridges and Connell1996; Kiel & Kalomiris, Reference Kiel and Kalomiris2015; Lavi et al., Reference Lavi, Katz, Ozer and Gross2019; Shaffer et al., Reference Shaffer, Suveg, Thomassin and Bradbury2012; Weissman et al., Reference Weissman, Bitran, Miller, Schaefer, Sheridan and McLaughlin2019). These findings provide clear evidence that maladaptive family environments, such as those featuring child maltreatment, family violence, and parent psychopathology pose significant risks to children’s emotional functioning and have far-reaching implications for children’s risk for psychopathology (Kaufman et al., Reference Kaufman, Puzia, Mead, Crowell, McEachern and Beauchaine2017; Lavi et al., Reference Lavi, Katz, Ozer and Gross2019; McLaughlin & Lambert, Reference McLaughlin and Lambert2017; Shields & Cicchetti, Reference Shields and Cicchetti1998; Weissman et al., Reference Weissman, Bitran, Miller, Schaefer, Sheridan and McLaughlin2019). Despite these considerations, less attention has been focused on developmental processes of and outcomes associated with distinct aspects of emotion regulation among children of parents with substance use disorders, particularly emotional reactivity.

Theories and frameworks such as emotion socialization are especially important and beneficial when considered within a developmental perspective (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Cumberland and Spinrad1998). Parents play crucial roles in young children’s emotional development largely because young children rely on them for help regulating their emotions since they often lack the emotion regulation skills needed to do so independently (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Cumberland and Spinrad1998; Kopp, Reference Kopp1989). However, as they age, young children develop more sophisticated and nuanced understanding of emotions and emotional expressions, largely through parental emotion socialization but also through lived experiences (Graziano et al., Reference Graziano, Keane and Calkins2010; Izard & Malatesta, Reference Izard, Malatesta and Osofsky1987). In this regard, children may be able to discern the benefits and consequences of expressing certain discrete emotions (e.g., anger, sadness) around specific people or in specific contexts, and through the development of effortful control and other regulatory skills, may better modulate their emotions reactions to successfully navigate their environment (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Ashana Ramsook and Ram2019; Graziano et al., Reference Graziano, Keane and Calkins2010; Zimmermann & Stansbury, Reference Zimmermann and Stansbury2003). For example, children may reduce or entirely conceal their expressions of sadness if such expressions are consistently ignored or met with parental harshness (e.g., Berlin & Cassidy, Reference Berlin and Cassidy2003). Children may also mask such sadness with disingenuous expressions of positive, “desirable,” or neutral emotions, or those that are more favorably or at least not negatively received by caregivers or others (Malatesta & Haviland, Reference Malatesta and Haviland1982; Zeman & Garber, Reference Zeman and Garber1996).

Theoretical process models of emotion regulation and reactivity

The idea that individuals can alter their emotional displays is the basis of Gross’ highly influential process model of the development of emotion regulation (Gross & Thompson, Reference Gross, Thompson and Gross2007). According to this model, expressive suppression in one way we can modulate our emotions and it involves the behavioral inhibition of emotional expression, or the process of hiding your emotions or altering how you express them (Shapero et al., Reference Shapero, Abramson and Alloy2016). It is important to note that suppression-style strategies do not imply a lack or absence of emotions, only the restriction or concealment of emotional display (e.g., Peters et al., Reference Peters, Overall and Jamieson2014). Many studies have shown that individuals who hide their emotions are just as likely to experience intense and/or frequent emotions as those who do not suppress (Niedenthal & Ric, Reference Niedenthal and Ric2017), however they refrain from displaying or expressing these emotions. Suppression is a response or reaction-focused strategy wherein the individual is trying to manage an emotion they are already feeling or starting to feel (Gross & Thompson, Reference Gross, Thompson and Gross2007). The emotion has already been elicited and experienced but the individual is grappling with whether or how to express their emotions, and this may depend on context-specific and individual characteristics, such as their location, the people around them, and the benefits and consequences of expressing their emotions in a certain way or with a certain intensity (Cutuli, Reference Cutuli2014; Peters et al., Reference Peters, Overall and Jamieson2014; Rogier et al., Reference Rogier, Garofalo and Velotti2019; Sun & Lau, Reference Sun and Lau2018; Troy et al., Reference Troy, Shallcross and Mauss2013). For example, expressing high levels of anger at school may result in more permanent negative consequences such as suspension or expulsion whereas there might be fewer consequences associated with expressing these same emotions at home (Grolnick et al., Reference Grolnick, Bridges and Connell1996).

Hiding or suppressing emotions is typically associated with longstanding negative consequences in both child and older populations (Butler et al., Reference Butler, Egloff, Wlhelm, Smith, Erickson and Gross2003). Suppressive strategies have consistently been linked with emotion dysregulation and subsequent emotional and psychological disorders such as depression (Dryman & Heimberg, Reference Dryman and Heimberg2018), anxiety and stress-related symptoms (Hosogoshi et al., Reference Hosogoshi, Takebayashi, Ito, Fujisato, Kato, Nakajima, Oe, Miyamae, Kanie and Horikoshi2020; Moore et al., Reference Moore, Zoellner and Mollenholt2008; Seligowski et al., Reference Seligowski, Lee, Bardeen and Orcutt2015), and suicide and non-suicidal self-injury (Forkmann et al., Reference Forkmann, Scherer, Böcker, Pawelzik, Gauggel and Glaesmer2014; Turner et al., Reference Turner, Chapman and Layden2012). Hiding or masking emotions has also been linked with impairments in interpersonal functioning and may interfere with an individual’s ability to forge or strengthen emotional or social bonds with others, partially because a core component of these relationships involve empathy, trust, emotional reciprocity, and feelings of connectedness (Howard Sharp et al., Reference Howard Sharp, Cohen, Kitzmann and Parra2016; Jacob et al., Reference Jacob, Suveg and Whitehead2014). Thus, hiding emotions may not only increase children’s risk for mental health challenges but they may also undermine children’s ability to build social network that could provide emotional support especially during times of psychological distress (Calkins et al., Reference Calkins, Gill, Johnson and Smith1999). During childhood, this may increase feelings of loneliness, isolation, diminished sense of belonging or worthiness, and/or sense of security or safety in interpersonal relationships (Howard Sharp et al., Reference Howard Sharp, Cohen, Kitzmann and Parra2016; Qualter & Munn, Reference Qualter and Munn2002).

Aside from understanding the outcomes associated with different patterns of emotional reactivity and emotion regulation, it is also important to identify how they develop and how they function in regards to children’s well-being. Studies are increasingly adopting more nuanced approaches that stem from or integrate developmental psychopathology frameworks to more robustly pinpoint relations between emotional reactivity and child functioning across different domains (e.g., Martin & Ochsner, Reference Martin and Ochsner2016; Tan et al., Reference Tan, Oppenheimer, Ladouceur, Butterfield and Silk2020; Ursache et al., Reference Ursache, Blair, Stifter and Voegtline2013). Specifically, it is ostensibly accepted that hiding emotions (or reducing your level of reactivity) can be both adaptive (or beneficial in some ways) and maladaptive or consequential and harmful in other ways (Aldao et al., Reference Aldao, Jazaieri, Goldin and Gross2014; Cole et al., Reference Cole, Ashana Ramsook and Ram2019; Juang et al., Reference Juang, Moffitt, Kim, Lee, Soto, Hurley and Whitbourne2016; Soto et al., Reference Soto, Perez, Kim, Lee and Minnick2011; Su et al., Reference Su, Lee and Oishi2013). Children from potentially traumatic family environments may use or over-rely on suppressive-style strategies to help them “fly under the radar” in their family environments, circumvent harmful or maladaptive interactions with caregivers (e.g., refraining from crying which may trigger a parent’s aggression), and otherwise reduce the potential for negative interaction that might cause psychological harm or distress (Punamäki et al., Reference Punamäki, Flykt, Belt and Lindblom2021). Growing up in emotionally unstable or aversive family contexts, where the child’s emotional expressions may do more harm than good, might promote emotional suppression or reduced affect displays, thereby turning a traditionally maladaptive strategy into one that is contextually adaptive or beneficial (Troy et al., Reference Troy, Willroth, Shallcross, Giuliani, Gross and Mauss2023). Indeed, children of parents with substance use problems have reported hiding emotions in order to “get by” and survive in their families (e.g., Kroll, Reference Kroll2004; Meulewaeter et al., Reference Meulewaeter, De Pauw and Vanderplasschen2019). However, despite these potential benefits, suppression may be fundamentally counterproductive, since it can prolong or intensify internal emotions (e.g., keeping emotions bottled up without diffusing or addressing them) and individuals may look to other more maladaptive outlets to express their emotions, such as via heightened aggression or substance use (Rogier et al., Reference Rogier, Garofalo and Velotti2019; Stellern et al., Reference Stellern, Xiao, Grennell, Sanches, Gowin and Sloan2022; Velotti et al., Reference Velotti, Garofalo, Bottazzi and Caretti2017). Additionally, bottling up emotions may also force children to overly rely on themselves for emotion regulation and emotional support, which may overwhelm or erode already vulnerable and developing regulatory systems (Suveg & Zeman, Reference Suveg and Zeman2004). From a developmental perspective, it may also rob children of opportunities to develop or strengthen healthy ways to process and express their emotions, which may influence children’s emotional understanding and broader emotional well-being (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Dennis, Smith-Simon and Cohen2009).

Suppressing emotions as an emotion regulation strategy is an understudied topic among child development fields (Gross & Cassidy, Reference Gross and Cassidy2019); most work is done with adolescents and adults. Thus, there may be a unique benefit in better understanding whether, how, and why pre-adolescent children (particularly young children) may engage in emotional masking, and the proximal and distal developmental outcomes that may be associated with masking/suppression (Fan et al., Reference Fan, Liu, Gao, Han, Jiang and Liu2023; Gross & Cassidy, Reference Gross and Cassidy2019; Gullone et al., Reference Gullone, Hughes, King and Tonge2010; McClain et al., Reference McClain, Younginer and Elledge2020; Weissman et al., Reference Weissman, Bitran, Miller, Schaefer, Sheridan and McLaughlin2019). Despite this lack of research, some suggest that young children may be more likely to suppress and use reactionary emotional strategies than antecedent-focused strategies like reappraisal (Gullone et al., Reference Gullone, Hughes, King and Tonge2010; Zimmer-Gembeck & Skinner, Reference Zimmer-Gembeck and Skinner2016). This notion largely stems from the fact that appraisal is more cognitively demanding and requires more sophisticated, robust, and dynamic neurocognitive skills that young children are yet to possess (e.g., DeCicco et al., Reference DeCicco, Solomon and Dennis2012). Yet, while young children may be unable to effectively engage in cognitive reframing and more advanced regulatory strategies, developments in executive functioning and effortful and inhibitory control across early childhood make it possible for children to effectively engage in emotional suppression and masking (Carlson & Wang, Reference Carlson and Wang2007; Kochanska et al., Reference Kochanska, Murray and Harlan2000; Moriguchi & Hiraki, Reference Moriguchi and Hiraki2013; Williams, Reference Williams2018). The few studies that focus on emotional reactivity and regulatory strategies among children of parents with mental health conditions show that expressive suppression is linked with increased risk of psychopathology and decreased emotional functioning across developmental periods (Miu et al., Reference Miu, Szentágotai-Tătar, Balazsi, Nechita, Bunea and Pollak2022). However, while extant research on childhood adversity and trauma has linked higher levels of emotional reactivity to symptoms of psychopathology (e.g. Dvir et al., Reference Dvir, Ford, Hill and Frazier2014; Shapero et al., Reference Shapero, Farabaugh, Terechina, DeCross, Cheung, Fava and Holt2019; Weissman et al., Reference Weissman, Bitran, Miller, Schaefer, Sheridan and McLaughlin2019), future studies may benefit from integrating more process models of emotion regulation with process models of parenting and family functioning and developmental psychopathology to better identify whether and how other forms or patterns of emotion regulation develop and may influence children’s emotional well-being (Gross & Cassidy, Reference Gross and Cassidy2019).

The present study

Parents with substance use disorders may struggle with emotion regulation or emotional availability, thereby interfering with their ability to appropriately respond to and connect with their children’s emotions (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Chethik, Burns and Clark1991; Molitor et al., Reference Molitor, Mayes and Ward2003; Shadur & Hussong, Reference Shadur and Hussong2020). Additionally, children of parents with alcohol and substance use problems often exhibit difficulties regulating emotions, which could undermine their emotional development and increase their risk for psychopathology (Molitor et al., Reference Molitor, Mayes and Ward2003; Punamäki et al., Reference Punamäki, Flykt, Belt and Lindblom2021; Shadur & Hussong, Reference Shadur and Hussong2020). However, few studies focus on how specific elements of emotion regulation such as emotional reactivity may develop among children of mothers with symptoms of alcohol dependence, specifically the role that maladaptive parenting and family context may play on these developmental processes (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Martin and Dennis2004; Cole, Reference Cole2014; Cole et al., Reference Cole, Dennis, Smith-Simon and Cohen2009; Paley & Hajal, Reference Paley and Hajal2022). Moreover, since young children’s independent emotion regulation capacities are still developing, parents’ responses to children’s emotions are an important context through which children internalize emotion-regulation strategies (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Michel and Teti1994); however, the development of regulatory processes is also influenced by the contexts in which parents and children exist. Since some posit that more sophisticated regulatory abilities develop and thus are more salient beginning in middle childhood (Compas et al., Reference Compas, Jaser, Bettis, Watson, Gruhn, Dunbar and Thigpen2017; Zimmer-Gembeck & Skinner, Reference Zimmer-Gembeck and Skinner2016), and since younger children are presumed more likely to engage in antecedent-focused, reactive regulatory strategies, it is important to examine whether and how higher-risk developmental contexts (e.g., maternal alcohol dependence) may impact distinct aspects of children’s emotion regulation. To address these gaps, the present sought to examine maternal insensitivity to children’s distress as a mediator in the relationship between maternal alcohol dependence and children’s emotional reactivity. Moreover, recent scholars have emphasized the need for more contextually informed interpretations of associations between maternal psychopathology, maladaptive caregiving, affective developmental settings, and children’s emotional reactivity and regulatory processes (e.g., Cole, Reference Cole2014; Gross & Cassidy, Reference Gross and Cassidy2019; Hajal & Paley, Reference Hajal and Paley2020; Panayiotou et al., Reference Panayiotou, Panteli and Vlemincx2021; Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Zeman, Poon and Miller2015). Therefore, interpretation of findings will be conducted in line with parenting process models (e.g., Abidin, Reference Abidin1992;) and developmental psychopathology frameworks (e.g., Cicchetti & Aber, Reference Cicchetti and Aber1998; Cicchetti & Rogosch, Reference Cicchetti and Rogosch1996; Frankenhuis & Del Giudice, Reference Frankenhuis and Del Giudice2012) that highlight adaptive and maladaptive functions underlying parents’ and children’s behaviors.

Our study had several aims and hypotheses. One major aim was to expand on recent research showing that maternal psychopathology and substance use (including alcohol use) problems may negatively impact caregiving responses to children’s emotional cues (e.g., Jacques et al., Reference Jacques, Sturge-Apple, Davies and Cicchetti2021; Karl, Reference Karl1995; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Teti and Cole2012, Reference Kim, Iyengar, Mayes, Potenza, Rutherford and Strathearn2017; Lowell et al., Reference Lowell, Maupin, Landi, Potenza, Mayes and Rutherford2020; Romanowicz et al., Reference Romanowicz, Vande Voort, Shekunov, Oesterle, Thusius, Rummans, Croarkin, Karpyak, Lynch and Schak2019). Our second aim was to evaluate how mothers’ responses to children’s emotional distress may impact children’s emotional development and reactivity over time (e.g., Jacques et al., Reference Jacques, Sturge-Apple, Davies and Cicchetti2021). We also had two main hypotheses. First, since maternal substance use problems have been previously linked with decreased sensitivity to children’s emotional cues (e.g., Jacques et al., Reference Jacques, Sturge-Apple, Davies and Cicchetti2021; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Iyengar, Mayes, Potenza, Rutherford and Strathearn2017; Lowell et al., Reference Lowell, Maupin, Landi, Potenza, Mayes and Rutherford2020; Romanowicz et al., Reference Romanowicz, Vande Voort, Shekunov, Oesterle, Thusius, Rummans, Croarkin, Karpyak, Lynch and Schak2019); we predicted a positive association between maternal alcohol dependence symptoms and mothers’ insensitive responses to children’s emotional distress such that greater endorsement of alcohol dependence symptoms at Wave 1 (M child age = 2 years old) would predict increases in maternal insensitivity to children’s distress over time (from Wave 1 to Wave 2, when children were approximately 3 years old). Additionally, although the literature has focused on identifying how and why risk factors within the parent and family environment (e.g., parent substance use problems) may contribute to children’s emotional over-reactivity (e.g., highly emotionally reactive children who may struggle to effectively regulate their emotions or adapt to change in their environments) (e.g., Davis et al., Reference Davis, Alto, Oshri, Rogosch, Cicchetti and Toth2020; Fabes et al., Reference Fabes, Martin, Hanish, Anders and Madden-Derdich2003), we hypothesized that children may suppress their emotions (or become less emotionally reactive) over time if they encounter caregiving responses that are less sensitive to their emotional cues. We based this hypothesis on prior work showing that parental insensitivity or caregiving responses that are not appropriately attuned or calibrated to children’s emotional needs or expressions (especially negative emotions like sadness) may be aversive, emotionally harmful contexts for children, especially younger children who still developing and honing their emotion-regulation skills and experiences as emotional beings in a broader familial context (Eisenberg & Fabes, Reference Eisenberg and Fabes1994; Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Fabes and Murphy1996; Field et al., Reference Field, Vega-Lahr, Scafidi and Goldstein1986; Leerkes et al., Reference Leerkes, Nayena Blankson and O’Brien2009). Consequently, over time, some children may perceive and internalize emotionally dismissive, inattentive, and invalidating family environments as unsafe spaces to openly express or experience their emotions, and therefore, may show less emotion in those environments (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Hu, Lu, Ma and Zheng2022; Eisenberg & Fabes, Reference Eisenberg and Fabes1994; Gross, Reference Gross1999; Lindblom et al., Reference Lindblom, Punamäki, Flykt, Vänskä, Nummi, Sinkkonen, Tiitinen and Tulppala2016; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Criss, Silk and Houltberg2017). In other words, children may ultimately conceal their emotions as an adaptive, protective strategy to cope with increasingly maladaptive and emotionally challenging contexts. Thus, since we expected that maternal alcohol dependence symptoms would predict increases insensitivity to children’s emotional distress, we also predicted that this association would subsequently predict decreases in children’s emotional reactivity from Wave 2 (M child age = 3.08 years (37.05 months); SD = 1.917 months) to Wave 3 (M child age = 4.04 years (48.57 months); SD = 2.112 months). When considered together, we believed both study aims would help us better identify whether and how maternal alcohol dependence symptoms influence caregiving responses to children’s emotional distress and how said responses may impact children’s later emotional functioning.

Methods

Participants

201 mother-child dyads were enrolled at baseline. Child participants (44% female) were approximately 26 months old (M = 2.14 years old, SD = 1.69) at Wave 1, 37 months old (M = 3.08 years old) at Wave 2 (one year after data collection at Wave 1), and 48 months old (M = 4.04 years old) at Wave 3, one year after Wave 2. Mothers’ average age at Wave 1 was 26.24 years old (SD = 5.784 years). Most families (more than 95%) were living below the poverty line and were receiving public assistance. A majority (67%) self-identified as Black or African American (56%) or Hispanic or Latino/a/e (11%) with fewer participants self-identifying as white or European American (23%), multiracial or multiethnic (7%), and “other” (3%).

A multiphase recruitment process was used to help us better identify and subsequently enroll dyads who might be at higher risk to experience various types of adversity or risk. First, our research team recruited mother-child dyads from local agencies serving families in need and families who may experiencing various types of acute and chronic adversity, such as poverty and family conflict and domestic violence. One such organization was a consortium of 17 local agencies dedicated to families impacted by child maltreatment or family adversity, or those living in lower income, under-resourced environments. The next step involved recruitment from rosters of families receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families obtained from the local county office of the Department of Human and Health Services. Enrollment was contingent upon (a) the adult woman participant reported that they were the target child’s biological mother and primary caregiver, (b) mothers reporting that the target child had not been diagnosed with significant developmental or cognitive disabilities that would hinder study participation, and (c) the target child was 24-months old (+/− 7 months) at the time of data collection at Wave 1. Families not meeting these criteria, and families wherein the target child had been adopted, placed in foster care, or had known cognitive, developmental, or motor impairments were deemed ineligible and consequently excluded from participation. To maximize the feasibility of our recruitment strategy, mothers with children as young as 18 months were enrolled for subsequent visits when the child turned 24-months old.

Procedure

Data were collected in three waves, each spaced one year apart. Collection began when the focal child was approximately two-years-old (M W1childage = 2.14 years, SD = 1.69). For each wave of the of data collection, mother-child dyads visited a university laboratory, at which time mother and child participants completed standardized questionnaires and assessments, and dyadic interactions were observed, with select dyadic tasks being recorded for later coding by two trained experimenters. Children’s emotional distress and mothers’ responses to children’s distress were assessed via the Strange Situation (Ainsworth & Wittig, Reference Ainsworth, Wittig and Foss1969). Both reunions (the point in the procedure when the mother returns to the child) were coded for the nature, intensity, and frequency of children’s expressions of emotional distress as well as the nature of mothers’ responses to said distress. Although historically used to assess children’s attachment styles, and while acknowledging heterogeneity in the levels of distress that children display throughout the Strange Situation (e.g., Kochanska & Coy, Reference Kochanska and Coy2002; Shiller et al., Reference Shiller, Izard and Hembree1986), the reunions were selected for the child distress paradigm since the task often successfully elicits emotional distress among child participants and mothers are primed to respond to their child’s distress upon returning to the room (Ainsworth et al., Reference Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters and Wall2015; Ainsworth & Wittig, Reference Ainsworth, Wittig and Foss1969). Thus, it presents an optimal paradigm through which child distress and parental responses to distress can be examined. Moreover, recent studies have used the Strange Situation in novel ways to assess non-attachment constructs and associations, including but not limited to assessments of mothers’ responses to children’s distress (e.g., Sturge-Apple et al., Reference Sturge-Apple, Skibo, Rogosch, Ignjatovic and Heinzelman2011), children’s reactivity during stressful familial contexts (e.g., Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Allen and Laurent2018), long-term developmental and psychological outcomes associated with maternal insensitivity or lack of responsiveness to children’s distress (e.g., Behrens et al., Reference Behrens, Parker and Haltigan2011; Köhler-Dauner et al., Reference Köhler-Dauner, Roder, Krause, Buchheim, Gündel, Fegert, Ziegenhain and Waller2019), and as indicators of risky, dysregulated, and maladaptive parent-child dynamics (e.g., Kochanska & Coy, Reference Kochanska and Coy2002; Lyons-Ruth et al., Reference Lyons-Ruth, Connell, Zoll and Stahl1987), some of which have been linked to increased risk for child psychopathology (e.g., Guo et al., Reference Guo, Spieker and Borelli2021; Hollenstein et al., Reference Hollenstein, Granic, Stoolmiller and Snyder2004). Operationalizations of both child emotional distress and mothers’ responses to child distress are described below.

In addition to the two trained experimenters who coded the Strange Situation’s reunions, two different trained coders provided ratings of children’s emotional reactivity at Wave 2 (M Child Age = 3.08 years) and Wave 3 (M Child Age = 4.04 years) using the Caregiver- Teacher Report Form (C-TRF for Ages 1 ½-5)’s Emotional Reactivity subscale. These two experimenters were either (a) postbaccalaureate research assistants with educational and professional backgrounds in either child development, child mental health, family processes, and/or family intervention implementation or (b) doctoral students in developmental psychology with research training in child psychopathology. All experimenters who were rating children’s emotional reactivity received structured and monitored training on how to identify, interpret, and code commonly known symptoms or indicators of childhood internalizing problems. As part of their training, all research staff working with child participants watched videos that depicted various manifestations of child internalizing symptomatology (e.g., irritability, withdrawn behaviors) and were instructed to use this training when evaluating and rating children’s behaviors and emotional expressions. Following training, each experimenter kept detailed written notes and records of multiple domains of children’s functioning, including the nature and extent of their emotional reactions and the context in which children expressed various emotions (e.g., noting that the child would get upset if they were yelled at or noting that the child would become irritable if left alone with an unfamiliar adult). These records and the resultant ratings were based on cumulative observation and interaction with children at both Wave 2 (7.43 hours) and Wave 3 (6.08 hours), including observations during laboratory visits, transitions between study tasks, and transportation to and from various laboratory rooms. Both raters maintained such records at Wave 2 when children were approximately three years old, and Wave 3 when children were approximately four years old, and provided their rating on the child Emotional Reactivity subscale after each dyad completed their assessment battery for each respective wave of data collection.

All study procedures were standardized across all study participants, and the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Maternal alcohol dependence and maternal psychopathology

Mothers’ alcohol dependence symptoms and depressive, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress symptoms were assessed at Wave 1 using the revised fourth edition of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS-IV; Robins et al., Reference Robins, Cottler, Bucholz and Compton1995). Each of the aforementioned psychiatric conditions is represented by their own respective index which includes the diagnostic criteria featured in the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Participants respond “yes” or “no” when asked whether they have ever experienced the symptom in question, thus higher scores on respective indices reflect more severe psychiatric presentations. The DIS-IV is a full structured interview designed for use by non-clinicians and non-clinically trained interviewers and can be used to assess major psychiatric conditions (including major depression, generalized anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and drug and alcohol dependence symptoms) within socioeconomically and racially and ethnically diverse community samples (Breslau et al., Reference Breslau, Kessler, Chilcoat, Schultz, Davis and Andreski1998; Buu et al., Reference Buu, Dipiazza, Wang, Puttler, Fitzgerald and Zucker2009; Hwa-Froelich et al., Reference Hwa-Froelich, Loveland Cook and Flick2008; Segal, Reference Segal2010; Tabet et al., Reference Tabet, Flick, Cook, Xian and Chang2016).

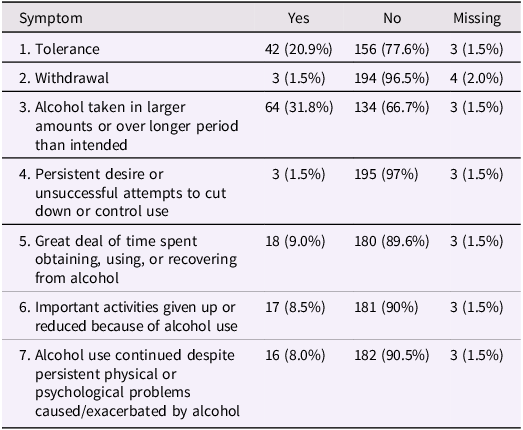

Symptoms of alcohol dependence were recorded via the seven-item Alcohol Dependence index which encompasses DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence. The subscale’s items are: (1) “alcohol tolerance,” (2) “alcohol withdrawal,” (3) “alcohol is often taken in larger amounts or over longer period than intended,” (4) “persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control alcohol use,” (5) “great deal of time spent in activities to obtain, use, or recover from alcohol”; (6) “important activities are given up or reduced because of alcohol”; and (7) “alcohol use is continued despite persistent physical or psychological problem that is caused or exacerbated by alcohol.” The mean of the inter-item correlations (M = .292) suggested good reliability (Clark & Watson, Reference Clark and Watson1995), and internal consistency analyses (seven items, α = .742, ω = .783) suggested good reliability in our sample (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti1994; McNeish, Reference McNeish2018). While this is a lifetime assessment of mothers’ alcohol dependence symptoms, we could not isolate mothers’ use or dependence symptoms to examine symptoms that emerged or changed during pregnancy, or subsequently examine any developmental effects of prenatal substance use or dependence.

Symptoms of Major Depressive Disorder were captured using the Major Depression subscale which included DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for said disorder. Symptoms featured on this subscale are: (1) feeling sad, empty, or depressed; (2) lost interest; (3) appetite problems; (4) sleep problems; (5) feeling slow or restless; (6) feeling tired of lacking energy; (7) feeling worthless or guilty; (8) having trouble thinking; (9) having thoughts about death; and (10) feeling “uninterested in everything” even if they did not endorse (2) lost interest. The average of the inter-item correlations (.566) suggested good to excellent reliability (Clark & Watson, Reference Clark and Watson1995). Reliability analyses revealed excellent internal consistency for this subscale (10 items, α = .942, ω = .954) (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti1994; McNeish, Reference McNeish2018).

Lifetime symptoms of Generalized Anxiety Disorder were measured using the Anxiety Disorder Subscale. Symptoms included on this subscale were: (1) feeling restless, keyed up, or on edge; (2) feeling easily fatigued; (3) experiencing difficulty concentrating or your mind going blank; (4) experiencing irritability; (5) experiencing muscle tension; (6) experiencing difficulty controlling worry; and (7) experiencing sleep disturbances. The average of the inter-item correlations (.746) indicated excellent reliability (Clark & Watson, Reference Clark and Watson1995). Further analyses revealed excellent internal consistency (seven items, α = .946, ω = .949) (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti1994; McNeish, Reference McNeish2018).

Lastly, the PTSD subscale captured lifetime symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. Symptoms assessed on this scale were: (1) difficulty falling or staying asleep; (2) irritability or outburst of anger; (3) difficulty concentrating; (4) hypervigilance; and (5) exaggerated startle response. The average of the inter-item correlations (.610) indicated good reliability (Clark & Watson, Reference Clark and Watson1995). Internal consistency (five items, α = .887, ω = .889) revealed excellent reliability (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti1994; McNeish, Reference McNeish2018).

Each psychopathology subscale – measuring depression, anxiety, and PTSD, respectively – were standardized and combined into a composite variable of “maternal psychopathology” which was used in all subsequent analyses.

Maternal insensitivity to children’s emotional distress

Mothers’ responses to children’s emotional distress were assessed using the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Systems’ Insensitive/Parent-Centered scale (IFIRS; Melby & Conger, Reference Melby, Conger, Kerig and Lindahl2001). This scale is conceptualized and has been used to capture broad and variable forms of parental insensitivity, specifically including any and all manifestations of caregiving that are parent-focused (meaning that they are more focused on or aligned with the parents’ needs, interests, goals, etc.) and inappropriately or maladaptively attuned to the child’s needs, interests, and/or capabilities (e.g., Sturge-Apple et al., Reference Sturge-Apple, Davies, Cicchetti and Manning2012). Maternal behaviors fitting this description may reflect a mothers’ lack of awareness of her child’s needs, interests, or abilities. Consequently, mothers’ behaviors may not be well-paced, well-timed, or otherwise calibrated to the child’s mood, needs, or desires. Also included are parents’ missed attempts to interact with or support children in both proactive (e.g., initiating contact) or reactive ways (e.g., a mother not picking a child up after a child reaches out for them, not responding to children’s questions, etc.). Mothers may also enforce rules, regulations, or restrictions upon the child without consideration for the child’s needs or autonomy. Importantly, insensitivity is recognized to possible manifest as both verbal (e.g., yelling or insulting a child) and/or nonverbal behavior (e.g., ignoring a child; walking away from children, etc.).

Two trained independent coders rated mothers’ insensitive responses on a 9-point Likert scale ranging from (1) “not at all characteristic,” meaning the mother displays no evidence of insensitive or parent-centered behavior, to (9) “mainly characteristic,” meaning the mother is consistently and typically insensitive and self-focused. Intraclass correlation coefficients produced in two-way mixed effects models ranged from .858 to .901 across 25% of the Strange Situation reunions from Waves 1 and 2, indicating excellent inter-rater agreement (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti1994). Raters’ scores were averaged and combined for subsequent analyses.

Child distress

Two independent coders rated the intensity and frequency of distress children exhibited throughout both reunions of the Strange Situation that was administered at Wave 1. We operationalized child distress as behavior that communicates emotional vulnerability such as anxiety, fear, nervousness, and sadness. This includes physical expressions (e.g., slumping, fidgeting), verbalizations (e.g., crying, whining), and actions (e.g., hiding from caregivers) since young children often express distress via both verbalizations and nonverbal behaviors (Kopp, Reference Kopp1989). All ratings were made along a 9-point Likert scale ranging from (1) “not at all characteristic” to (9) “mainly characteristic.” Intraclass correlation coefficients produced from two-way mixed effects models ranged from .92 to .94 across the Strange Situation’s two reunions, indicating excellent inter-rater agreement (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti1994). An average of both coders’ ratings from reunion 1 and reunion 2 of Wave 1’s Strange Situation was used in the final analyses.

Child emotional reactivity as a measure of expressive suppression

Children’s emotional reactivity was rated by two trained experimenters via the Emotionally Reactive Syndrome Scale from the Caregiver-Teacher Report Form for ages 1 ½ to 5 (C-TRF 1 ½-5; Achenbach & Rescorla, Reference Achenbach and Rescorla2000) at Waves 2 and 3. Behaviors on this subscale are meant to reflect the nature, intensity, and frequency of children’s emotional arousal. The scale’s items include: (1) being disturbed by change in routine; (2) nervous movements or twitching; (3) sudden changes in mood or feelings; (4) sulks a lot; (5) upset by new people or situations; (6) whining; and (7) worries. For each item, responses are recorded as (1) “not true (as far as you know)”; (2) “somewhat or sometimes true”; and (3) “very true or often true.” Prior work has used this scale as an indicator of children’s emotional functioning and as a predictor of children’s risk to experience later internalizing problems (e.g., Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Izard and Hyde2014). It has also been used and validated in studies featuring socioeconomically and racially and ethnically diverse samples and children of parents with psychopathologies (e.g., Cai et al., Reference Cai, Kaiser and Hancock2004; Gregl et al., Reference Gregl, Kirigin, Sućeska Ligutić and Bilać2014). Average inter-item correlations (across Waves 2 and 3 = .118) reflected good reliability. Two-way mixed effects models (ICCs across Waves 2 and 3 = .765) suggested very good to excellent inter-rater reliability among coders. Due to a lack of distinct observational assessments of early childhood expressive suppression (Gross & Cassidy, Reference Gross and Cassidy2019), children’s emotional reactivity served as a proxy measure of expressive suppression, with decreases across waves being interpreted as possible evidence for expressive suppression.

Child self-control

The Social Skills Rating System-Parent Form (SSRS-P; Gresham & Elliott, Reference Gresham and Elliott1990) is a robust parent-reported assessment of children’s social behavior across several domains of functioning. The 10-item Self-Control subscale of the Social Skills Scale was completed by the child’s mother at Wave 2 when the child was approximately three-years-old (MW1child age = 3.08 years) and was used to measure children’s ability to regulate and control their impulses, negative emotions, and behaviors in social settings. Exemplary items include “controls temper in conflict situations with you”; “ends disagreements with you calmly”; “controls temper when arguing with other children”; and “responds appropriately to teasing from friends or relatives of his or her own age”. For each item, mothers indicated how often their child displayed or engaged in the described behavior on a scale from (0) “never” to (2) “very often.” Test-retest reliability ranged from .65 to .93, internal consistency results (10 items, α = .831, ω = .830) suggested excellent reliability (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti1994; McNeish, Reference McNeish2018), and the average inter-item correlation (.331) also indicated good reliability (Clark & Watson, Reference Clark and Watson1995).

Parent and family sociodemographic variables

At Wave 1, mothers completed a demographics interview (Cicchetti & Carlson, Reference Cicchetti and Carlson1989) which included information regarding her and her child’s racial and ethnic identity, ages, and gender; total annual family income; and her highest level of education attained. This demographic measure was developed for and has been consistently used in research with lower income, higher-risk samples (e.g., Cicchetti et al., Reference Cicchetti, Rogosch and Toth2006; Davies et al., Reference Davies, Sturge-Apple, Cicchetti, Manning and Zale2009)

Data analysis plan

SPSS Version 29 (IBM Corp. Released, 2022) was used to obtain descriptive statistics, zero-order correlations between study variables, and to assess patterns of missing data. Little’s missing data test (1988) was selected to assess whether data were missing completely at random (MCAR), and to help us make an informed selection of the estimation method within subsequent structural equation modeling (SEM) analyses. AMOS Version 29 (IBM Corp. Released, 2022) was used for all SEM analyses. Latent difference score (LDS) analyses were modeled within SEM to parameterize change over time in mothers’ insensitivity to child distress and children’s emotional reactivity. See Figure 1 for a parameterization of the LDS model for change in maternal insensitivity to children’s distress from Wave 1 to Wave 2. The LDS parameterization for change in children’s emotional reactivity from Wave 2 to Wave 3 is presented in Figure 2. Several covariates were entered to better estimate pathways linking maternal alcohol dependence, maternal insensitivity to child distress, and children’s emotional reactivity. Specifically, family income and maternal age were included as covariates given their known influence on caregiving, mother-child interactions, and children’s developmental outcomes (Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Lee, Rosales-Rueda and Kalil2018; Highlander et al., Reference Highlander, Zachary, Jenkins, Loiselle, McCall, Youngstrom and Jones2021). Additionally, noting the literature’s lack of consensus regarding the role child gender plays in parents’ emotion socialization practices and early emotional development (see Chaplin & Aldao, Reference Chaplin and Aldao2013 for a deeper review), and the lack of rigorous examination of gender differences in young children’s use of suppressive emotion-regulation strategies (Gross & Cassidy, Reference Gross and Cassidy2019), child gender was entered as a covariate. Moreover, psychological distress and mental health conditions such as depression and post-traumatic stress are not only prevalent among Black and Latina populations (Alim et al., Reference Alim, Charney and Mellman2006; Himle et al., Reference Himle, Baser, Taylor, Campbell and Jackson2009; Williams, Reference Williams2018) but these disorders also often co-occur with substance dependence (Debell et al., Reference Debell, Fear, Head, Batt-Rawden, Greenberg, Wessely and Goodwin2014; Hasin et al., Reference Hasin, Sarvet, Meyers, Saha, Ruan, Stohl and Grant2018) and are known to directly and indirectly impact caregiving, family processes, and children’s psychological development (Leijdesdorff et al., Reference Leijdesdorff, van Doesum, Popma, Klaassen and van Amelsvoort2017; van der Pol et al., Reference van der Pol, Groeneveld, Endendijk, van Berkel, Hallers-Haalboom, Bakermans-Kranenburg and Mesman2016). Thus, we included these disorders, represented as a standardized composite termed “maternal psychopathology” as a covariate. This composite, created to preserve degrees of freedom and construct the most parsimonious model was built by standardizing each disorder’s respective DIS-IV subscale and summing said standardized results.

Figure 1. Parameterization of latent difference score modeling for change in maternal insensitivity to children’s emotional distress from wave 1 to wave 2.

Figure 2. Parameterization of latent difference score modeling of change in children’s emotional reactivity from wave 2 to wave 3.

Furthermore, since we wanted to use mothers’ caregiving responses and children’s distress levels from both of the Strange Situation reunions, we averaged mothers’ insensitivity and children’s distress ratings from Reunion 1 and Reunion 2 at each wave and used this score in subsequent analyses. Lastly, many emphasize that emotional reactivity is bidirectionally associated with an individual’s broader emotion and self-regulation abilities (Derryberry & Rothbart, Reference Derryberry and Rothbart1997; Fox, Reference Fox1989; Gross, Reference Gross1998; Mirabile et al., Reference Mirabile, Scaramella, Sohr-Preston and Robison2009). Specifically, an individual’s emotional expressions are partially dictated by their ability to monitor, process, and modulate their internal emotional experiences (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Spinrad and Eggum2010; Shapero et al., Reference Shapero, Abramson and Alloy2016; Sheppes et al., Reference Sheppes, Suri and Gross2015). For example, children with poor or impaired emotion-regulation skills may exhibit intense and prolonged emotional reactions when emotionally aroused, while a child with better emotion-regulation skills may show fewer or less intense emotions (Eisenberg & Fabes, Reference Eisenberg and Fabes1992a). Thus, since emotional reactivity is often dynamically influenced by emotion regulation more broadly (e.g., Ursache et al., Reference Ursache, Blair, Stifter and Voegtline2013), children’s social self-control at Wave 2 was entered as a covariate predicting subsequent change in children’s emotional reactivity.

Results

Since non-significant results on Little’s (Reference Little1988) MCAR test indicate that data are missing completely at random, our findings from Little’s MCAR test revealed that the data were MCAR, χ 2 (64) = 57.289, p = 7.11. Given families’ high mobility and relocation rates over time, combined with the sample’s frequent experiences of familial and socioeconomic adversity, not all families were able to contribute data at every timepoint throughout the study; however, retention remained relatively high, with 86% families returning across three annual data collection waves. Families who participated at baseline but were unable to participate a year later (Wave 2) were allowed to contribute data at Wave 3. Further examination into patterns of missing data on all study variables (including covariates) did not reveal evidence of selective attrition or significant differences between mother-child dyads who dropped out and those who remained in the study.

A detailed breakdown of frequencies for each of the lifetime alcohol dependence symptoms as reported by mothers at baseline are shown in Table 1. 75 mothers (37% of the sample) in total endorsed at least one symptom or indicator of lifetime alcohol dependence; 30 mothers (15% of the sample) endorsed one symptom of alcohol dependence, 22 mothers (11% of the sample) endorsed two symptoms of alcohol dependence, and 23 (11.5% of the sample) endorsed three or more symptoms of alcohol dependence. Moreover, of the 75 mothers reporting symptoms of alcohol dependence, 19 (25% of this subset of mothers) indicated that they had experienced symptoms of alcohol dependence within 12 months of Wave 1. 35 (46.7% of mothers reporting symptoms of alcohol dependence) reported that they were experiencing symptoms of alcohol dependence at Wave 1. Most mothers (81%) reported that they experienced their first symptom of alcohol dependence in adolescence or early adulthood, with the youngest age at first symptom appearance being 12 and the oldest being 37. Eight mothers (4% of the total sample) reported ever receiving treatment for alcohol dependence. While these statistics may seem low, they are aligned with prior work investigating alcohol use disorders and alcohol dependence in community samples with racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically underrepresented populations (e.g., Mulia & Bensley, Reference Mulia and Bensley2020). Prior to proceeding to SEM to examine the study’s main research questions, Maximum Likelihood Robust estimation was chosen as the estimator given its ability to handle non-normally distributed and missing data (Allison, Reference Allison2003; Enders & Bandalos, Reference Enders and Bandalos2001; Li & Lomax, Reference Li and Lomax2017). Descriptive statistics and correlations among all study’s variables are displayed in Table 2.

Table 1. Frequency distribution of mothers’ responses on the DIS-IV alcohol dependence symptom index

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations for study’s primary variables

Note. W1 = Wave 1; W2 = Wave 2; W3 = Wave 3. Ch. = child; Mat. = maternal; Alc. Dep. = alcohol dependence symptoms; Psychop. = psychopathology symptoms. Avg. = average; Ch. Dist. = child distress; Insens. = maternal insensitivity; Self-Cont. = self-control; Emot. React. = emotional reactivity. * p < .05. ** p < .01.

Findings from the process-oriented structural equation model are depicted in Figure 3. An evaluation of overall model and practical fit indices indicated excellent model fit, χ 2(4) = 3.28, p = .51; CFI = 1.0; RSMEA = .000, according to cutoff criteria outlined by West et al. (Reference West, Taylor and Wu2012). For our primary pathways of interest, the model revealed that over and above maternal age, family income, mothers’ non-substance-related psychopathology, and children’s baseline emotional distress, maternal alcohol dependence symptoms at Wave 1 predicted increased insensitivity to children’s distress from Wave 1 to Wave 2, β = .16, SE = .09, p = .013. Moreover, this increased insensitivity to children’s distress from Wave 1 to Wave 2 predicted decreases in children’s emotional reactivity from Wave 2 to Wave 3, β = −.29, SE = .12, p = .009. To test whether this mediational path linking maternal alcohol dependence to children’s emotional reactivity through maternal insensitivity was statistically significant, we computed Monte Carlo confidence intervals using Selig and Preacher’s (Reference Selig and Preacher2008) method to test for significant mediation since bootstrapped confidence intervals cannot be computed in AMOS for samples with missing data. The 95% Monte Carlo confidence intervals (computed with 2,000 repetitions) did not contain zero [−.173, −0.001], thereby indicating that maternal insensitivity to child distress is a significant mediator of the relationship between maternal alcohol dependence symptoms and children’s emotional reactivity.

Figure 3. Structural equation model examining longitudinal associations between sociodemographic variables, maternal psychopathology symptoms, maternal alcohol dependence symptoms, change in maternal insensitivity to children’s distress, and change in children’s emotional reactivity. Dashed lines indicate non-significant pathways. W1 = wave 1; W2 = wave 2; W3 = wave 3. * p < .05.

Additionally, several covariates were significant or marginally significant predictors of maternal insensitivity to child distress or child emotional reactivity. First, child gender predicted mothers’ insensitivity to child distress such that mothers became increasingly sensitive to girls’ distress over time, β = −.13, SE = .23, p = .03. Lastly, children’s social self-control at Wave 2 was marginally predictive of children’s emotional reactivity from Wave 2 to Wave 3 such that higher levels of self-control when children were approximately 3 years old predicted decreases in emotional reactivity between ages 3 and 4 years old, β = −.13, SE = .05, p = .08

Discussion