Introduction

This paper describes rich Middle and Late Jurassic radiolarian faunas from four localities in the Hallstatt Mélange near Bad Mitterndorf in Austria. Radiolarian assemblages are well preserved, suitable for taxonomic studies, and precise biostratigraphy.

Middle and Late Jurassic low-latitude radiolarians have been relatively well studied in terms of species-level systematics and biochronology (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Bartolini, Carter, Conti, Cortese, Danelian, De Wever, Dumitrica, Dumitrica-Jud, Goričan, Guex, Hull, Kito, Marcucci, Matsuoka, Murchey, O’Dogherty, Savary, Vishnevskaya, Widz and Yao1995a, Reference Baumgartner, O’Dogherty, Goričan, Dumitrica-Jud, Dumitrica, Pillevuit, Urquhart, Matsuoka, Danelian, Bartolini, Carter, De Wever, Kito, Marcucci and Steigerb); however, the systematics of genera and families has not been sufficiently elaborated yet. O’Dogherty et al. (Reference O’Dogherty, Carter, Dumitrica, Goričan, De Wever, Bandini, Baumgartner and Matsuoka2009) presented an illustrated catalogue of type species of Jurassic and Cretaceous genera described so far. All genera were revised, and many were considered as invalid (synonyms, homonyms, nomina dubia). Another group of radiolarians that needs taxonomic revision are those Mesozoic species that still bear inappropriate names of Recent genera. The structure of the catalogue, consisting exclusively of illustrations and synonymy, did not allow us to discuss the distinguishing characteristics of the valid genera or to describe new taxa. The primary aim of this paper is to move towards a more natural taxonomy of Jurassic radiolarians. Six new genera are described, a replacement name for a homonym is proposed, the diagnoses of six valid genera are emended, and remarks for several other genera are provided to clarify their definition. For all new and revised genera, a list of included species is presented. Two new families are erected and two new species are described.

In addition to radiolarian taxonomy, this paper contributes to the biostratigraphic data of the Hallstatt Mélange in the Northern Calcareous Alps. Extensive radiolarian dating over the last 15 years has provided a wealth of age constraints in deep-water sediments of the Tirolic units and the Hallstatt Mélange (Suzuki and Gawlick, Reference Suzuki and Gawlick2003, Reference Suzuki and Gawlick2009; Missoni and Gawlick, Reference Missoni and Gawlick2011a, Reference Missoni and Gawlickb and references therein). These data had important implications for the reconstruction of the Jurassic tectonostratigraphy and distinguished several trench-like basins that formed progressively during the propagation of thrusting (see Missoni and Gawlick, Reference Missoni and Gawlick2011a, Reference Missoni and Gawlickb; Gawlick et al., Reference Gawlick, Missoni, Schlagintweit and Suzuki2012 for the latest reviews). However, the structure of this area, especially that of the Hallstatt Mélange, is extremely complex and the proposed tectonostratigraphic model can still be refined with additional biostratigraphic data.

Geological overview

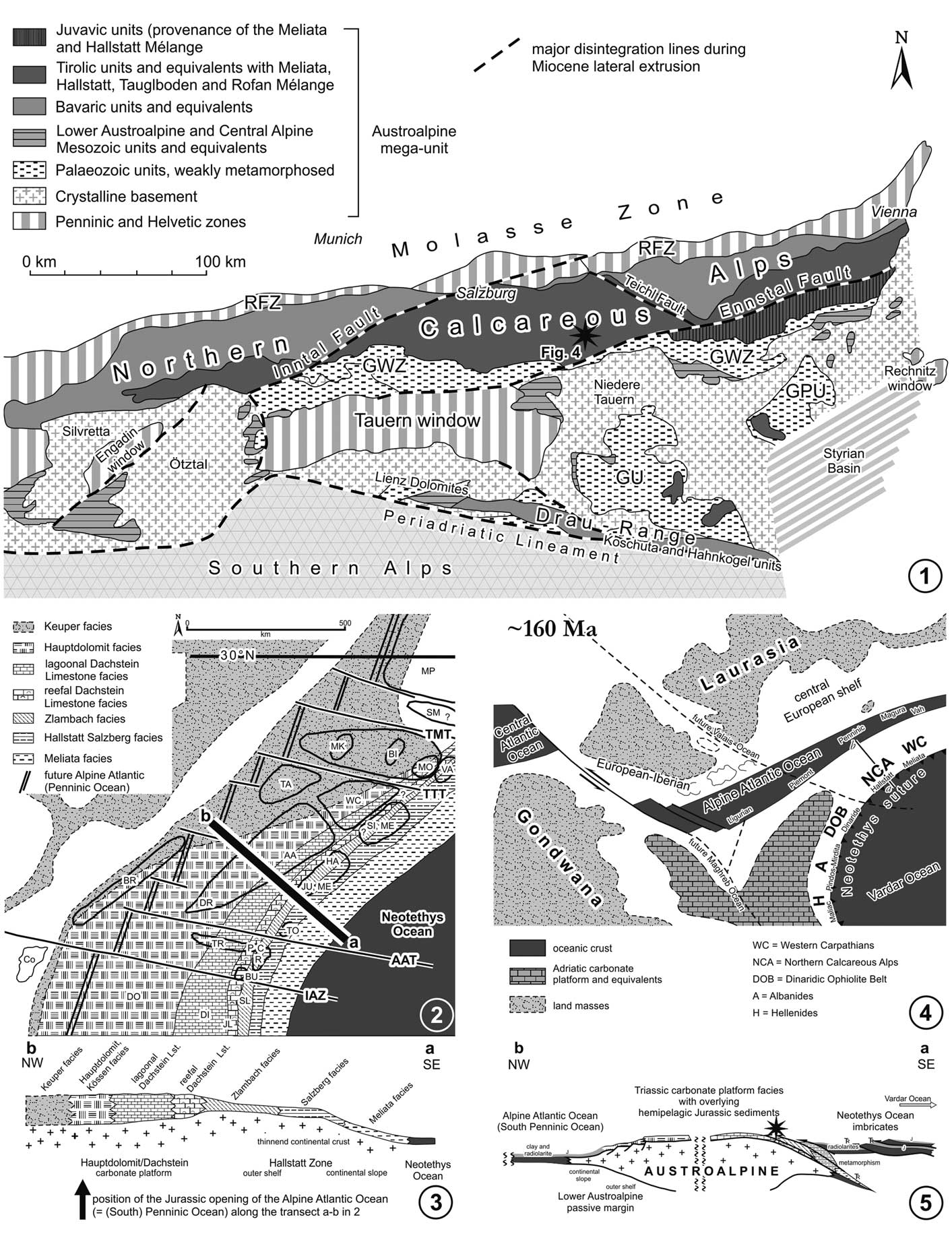

The study area is located in the central Northern Calcareous Alps around 100 km southeast of Salzburg (Fig. 1.1). The Northern Calcareous Alps represent a far travelled nappe system in the highest structural position of the Eastern Alps (Tollmann, Reference Tollmann1985) and belong palaeogeographically to the Austroalpine domain (Fig. 1.1).

Figure 1 Tectonic and paleogeographic maps. (1) Tectonic sketch map of the Eastern Alps and study area (after Tollmann, Reference Tollmann1987; Frisch and Gawlick, Reference Frisch and Gawlick2003); GPU Graz Palaeozoic Unit; GU Gurktal Unit; GWZ Greywacke Zone; RFZ Rhenodanubian Flysch Zone. Star indicates study area (Fig. 3). (2) Late Triassic paleogeographic position and facies zones of the Austroalpine domain as part of the northwestern Neotethys passive margin; IAZ=Iberia-Adria Zone transform fault, AAT=future Austroalpine-Adria transform fault, TTT=future Tisza-Tatra transform fault, TMT=future Tisza-Moesia transform fault, AA=Austroalpine, BI=Bihor, BR=Briançonnais, BU=Bükk, C=Csovar, Co=Corsica, DI=Dinarides, DO=Dolomites, DR=Drau Range, HA=Hallstatt Zone, JU=Juvavicum, JL=Julian Alps, ME=Meliaticum, MK=Mecsek, MO=Moma unit, MP=Moesian platform, P=Pilis-Buda, R=Rudabanyaicum, SI=Silicicum, SL=Slovenian trough, SM=Serbo-Macedonian unit, TA=Tatricum, TO=Tornaicum, TR=Transdanubian Range, VA=Vascau unit, WC=central West Carpathians (modified after Haas et al., Reference Haas, Kovacs, Krystyn and Lein1995; Gawlick et al., Reference Gawlick, Frisch, Vecsei, Steiger and Böhm1999, Reference Gawlick, Frisch, Hoxha, Dumitrica, Krystyn, Lein, Missoni and Schlagintweit2008). (3) Schematic cross section (for position, see line a-b in 2) showing the typical passive continental margin facies distribution across the Austroalpine domain in Late Triassic time (after Gawlick and Frisch, Reference Gawlick and Frisch2003). (4) Palaeogeographic position of the Northern Calcareous Alps as part of the Austroalpine domain in Late Jurassic time (after Frisch, Reference Frisch1979; Gawlick et al., Reference Gawlick, Frisch, Hoxha, Dumitrica, Krystyn, Lein, Missoni and Schlagintweit2008). In this reconstruction the Northern Calcareous Alps are part of the Jurassic Neotethyan Belt (orogen) striking from the Carpathians to the Hellenides. The Neotethys suture is equivalent to the obducted West-Vardar ophiolite complex (e.g., Dinaric Ophiolite Belt) in the sense of Schmid et al. (Reference Schmid, Bernoulli, Fügenschuh, Matenco, Schefer, Schuster, Tischler and Ustaszewski2008)=far-travelled ophiolite nappes of the western Neotethys Ocean in the sense of Gawlick et al. (Reference Gawlick, Frisch, Hoxha, Dumitrica, Krystyn, Lein, Missoni and Schlagintweit2008) (see Robertson, Reference Robertson2012 for discussion). The eastern part of the Neotethys Ocean remained open=Vardar Ocean (Missoni and Gawlick, Reference Missoni and Gawlick2011a). Toarcian to Early Cretaceous Adria-Apulia carbonate platform and equivalents according to Golonka (Reference Golonka2002), Vlahović et al. (Reference Vlahović, Tišljar, Velić and Matičec2005), and Bernoulli and Jenkyns (Reference Bernoulli and Jenkyns2009). (5) Schematic cross section reconstructed for Middle to Late Jurassic times showing the passive continental margin of the Lower Austroalpine domain facing the Penninic Ocean to the northwest (e.g., Tollmann, Reference Tollmann1985; Faupl and Wagreich, Reference Faupl and Wagreich2000) and the lower plate position and imbrication of the Austroalpine domain in relation to the obducted Neotethys oceanic crust (after Gawlick et al., Reference Gawlick, Frisch, Hoxha, Dumitrica, Krystyn, Lein, Missoni and Schlagintweit2008; compare with Frisch, Reference Frisch1979). Star indicates position of study area (compare Figure 3).

In Middle–Late Triassic times the Austroalpine domain as part of the central and southeastern European shelf show a typical carbonate passive continental margin facies distribution (Fig. 1.2–1.3), whereas in Jurassic times the Austroalpine realm was situated between the Penninic Ocean to the northwest and the Neotethys Ocean in the southeast (Fig. 1.4–1.5).

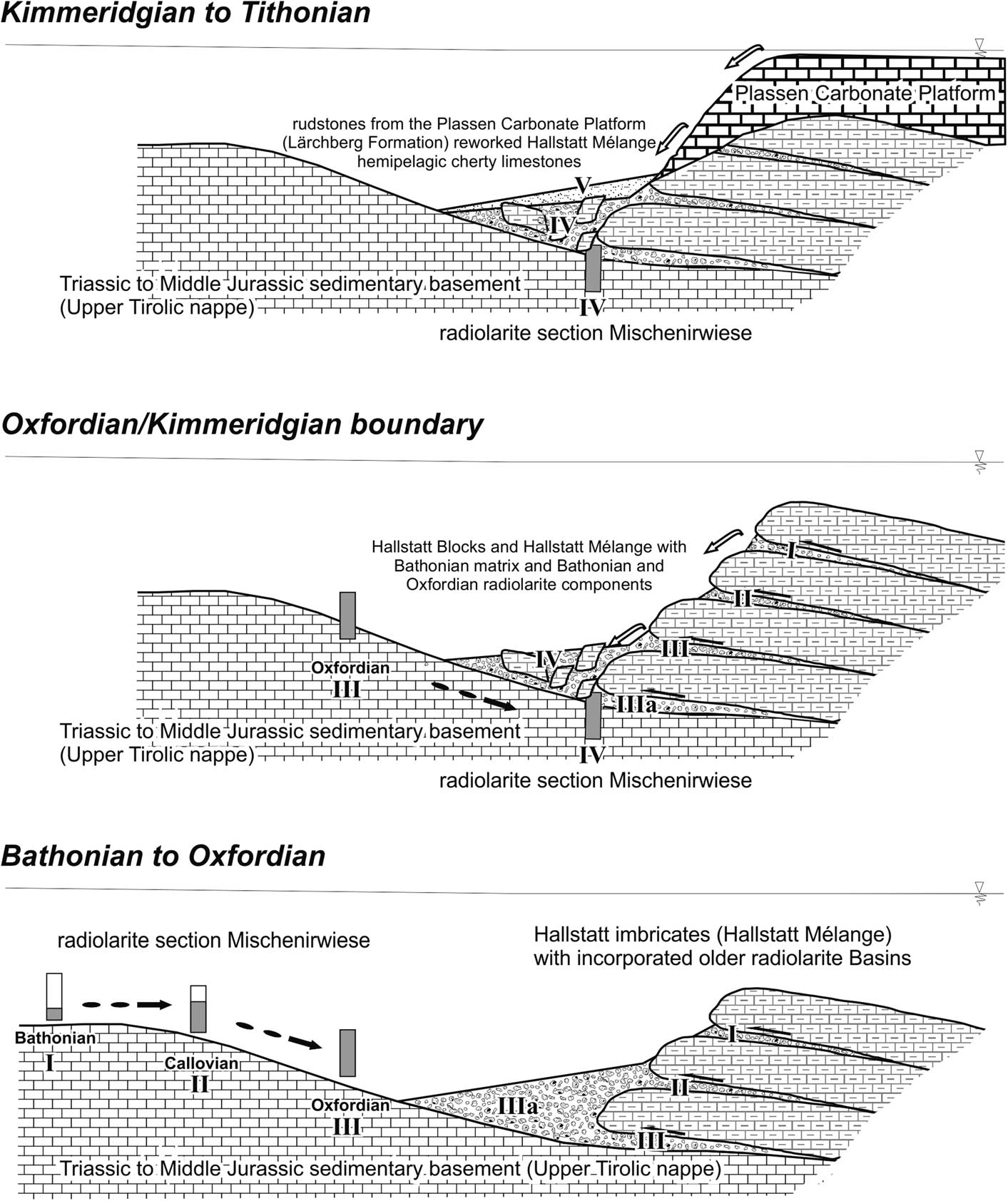

Contemporaneous with progressive Jurassic extension and opening of the Alpine Atlantic Ocean (and the Penninic realm as part of it; see Missoni and Gawlick, Reference Missoni and Gawlick2011a for details) as an eastward continuation of the Central Atlantic Ocean, closure of parts of the Neotethys Ocean with formation of the Neotethys ophiolite imbricates started in the late Early Jurassic and prevailed until the early Late Jurassic (Karamata, Reference Karamata2006). Obduction of the Neotethys ophiolite imbricates started in the Middle Jurassic and the Austroalpine and its northern and southern equivalents attained a lower plate position (Frisch and Gawlick, Reference Frisch and Gawlick2003, Gawlick et al., Reference Gawlick, Frisch, Hoxha, Dumitrica, Krystyn, Lein, Missoni and Schlagintweit2008, Schmid et al., Reference Schmid, Bernoulli, Fügenschuh, Matenco, Schefer, Schuster, Tischler and Ustaszewski2008). Westward to northwestward propagating Middle to early Late Jurassic compression led to the imbrication of the Austroalpine domain and its equivalents along the Neotethys suture and resulted in the Neotethyan orogeny (Missoni and Gawlick, Reference Missoni and Gawlick2011a). A characteristic feature of this orogenesis is the formation of deep-water radiolaritic basins in front of the westward propagating nappe stack. Sediment supply in these basins derived from the nappe fronts.

Gawlick et al. (Reference Gawlick, Frisch, Vecsei, Steiger and Böhm1999) interpreted this sedimentation pattern as a reflection of nappe movements in the Northern Calcareous Alps in the late Middle to early Late Jurassic and related it to the Kimmeric orogeny according to earlier authors (see ‘Jurassic gravitational tectonics’ in Plöchinger, Reference Plöchinger1974, Reference Plöchinger1976; Tollmann, Reference Tollmann1981, Reference Tollmann1985, Reference Tollmann1987; Mandl, Reference Mandl1982). This orogenic event (Lein, Reference Lein1985, Reference Lein1987a, Reference Leinb) was related to the closure of the western half of the Neotethys Ocean, today named the Neotethyan orogeny (Missoni and Gawlick, Reference Missoni and Gawlick2011a).

In the southern and therefore highest nappe group (Tirolic units and equivalents, Fig. 1.2–1.3) of the Northern Calcareous Alps the remains of this orogenic event are well preserved with a series of deep-water radiolaritic basins which were formed in sequence in front of the advancing nappe front (e.g., Gawlick et al., Reference Gawlick, Frisch, Vecsei, Steiger and Böhm1999, Missoni and Gawlick, Reference Missoni and Gawlick2011b). These southernmost radiolarite basins contain the Hallstatt Mélange as an erosional product of the Juvavic nappes, which are mainly eroded today. Subsequently the trench-like basins became overthrusted and incorporated into the accretionary prism (Missoni and Gawlick, Reference Missoni and Gawlick2011b). This Hallstatt Mélange was therefore formed in the late Early to early Late Jurassic interval as a result of successive shortening of the Triassic to Jurassic distal shelf area (Hallstatt Zone).

Jurassic evolution of the southern Northern Calcareous Alps

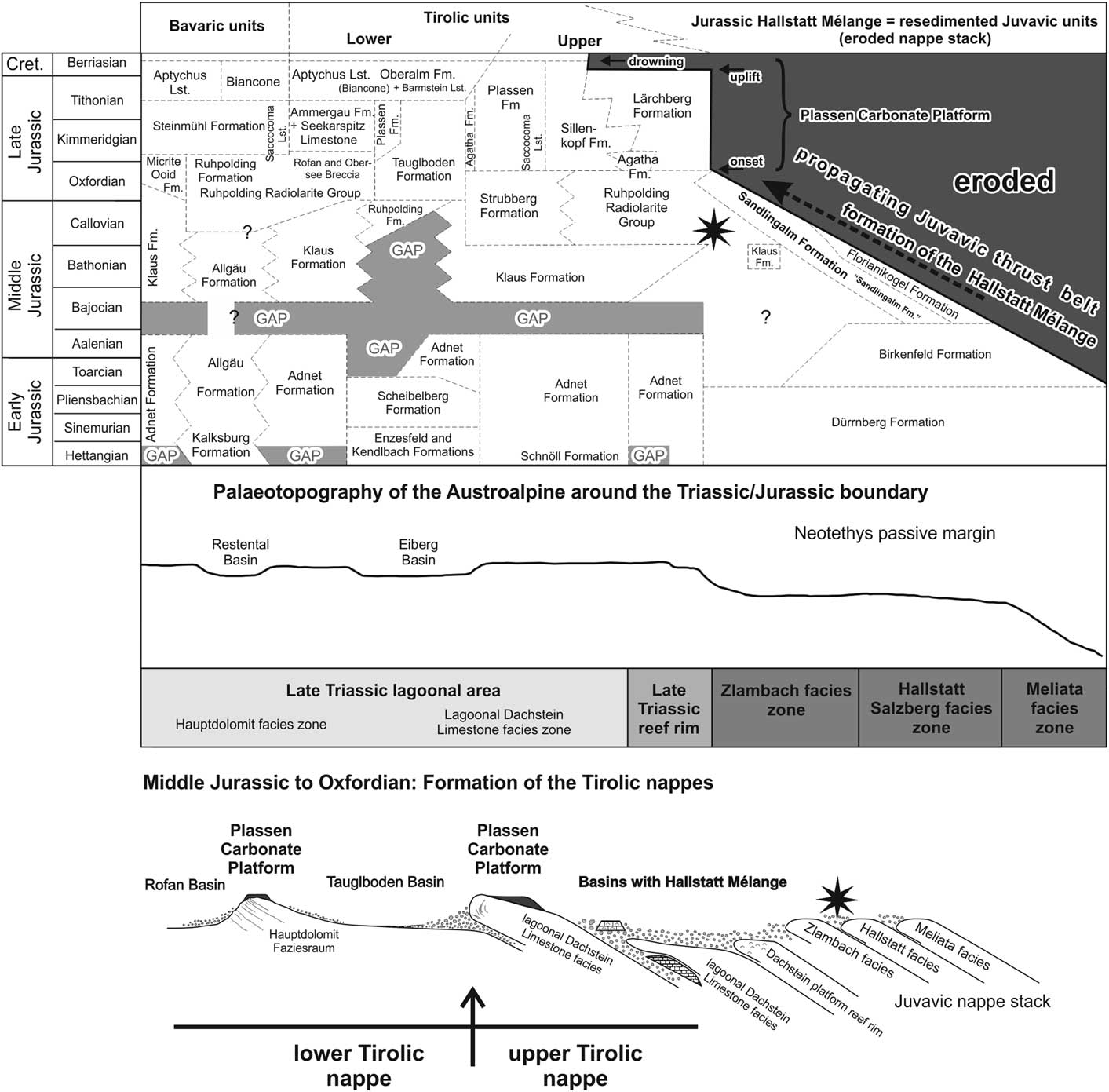

In the early Early Jurassic, sedimentation was generally controlled by the topography of the Late Triassic Hauptdolomit/Dachstein carbonate platform (Böhm, Reference Böhm2003, Gawlick and Frisch, Reference Gawlick and Frisch2003; Figs. 1, 2). On top of the Rhaetian shallow-water carbonates, red condensed limestones of the Adnet Group (?late Hettangian/Sinemurian to Toarcian: Böhm, Reference Böhm1992, Reference Böhm2003) were deposited, mostly separated by a gap of sedimentation (mainly early Hettangian, partly also late Hettangian; Fig. 2). On top of the Rhaetian Kössen Formation (e.g., Eiberg Basin, Restental Basin, Fig. 2) cherty and marly bedded limestones (Kendlbach Formation; Scheibelberg Formation: Böhm, Reference Böhm1992, Reference Böhm2003; Krainer and Mostler, Reference Krainer and Mostler1997; Ebli, Reference Ebli1997) were deposited, while in marginal areas of the basins crinoidal or sponge-spicule rich limestones of the Enzesfeld Formation were laid down (Böhm, Reference Böhm1992). In the late Pliensbachian to early Toarcian a horst-and-graben morphology developed (Bernoulli and Jenkyns, Reference Bernoulli and Jenkyns1974, Krainer et al., Reference Krainer, Mostler and Haditsch1994) and triggered breccia formation along submarine slopes and escarpments (Böhm et al., Reference Böhm, Dommergues and Meister1995). The Toarcian and most of the Middle Jurassic are characterized by starved sedimentation, ferro-manganese crusts, or a hiatus on the horsts, whereas the grabens were filled with deep-water carbonates and breccias, which latter formed near fault scarps. Neptunian dykes are found on the horsts. In the newly formed basinal areas gray bedded limestones of the younger Allgäu Formation were deposited, while condensed red limestones of the Klaus Formation formed on the top of the topographic highs (Krystyn, Reference Krystyn1971, Reference Krystyn1972; Fig. 2).

Figure 2 Stratigraphic table with lithostratigraphic names and main tectonic events of the Jurassic in the Austroalpine realm with their variations depending on the palaeogeographic position (after Gawlick et al., Reference Gawlick, Missoni, Schlagintweit, Suzuki, Frisch, Krystyn, Blau and Lein2009); star indicates investigated sequence. Note that this sequence is thrust further northward to its present position during younger shortening events. Bavaric units, Tirolic units, and the Hallstatt Mélange belong to the Northern Calcareous Alps.

This sedimentation pattern changed dramatically in the late Middle Jurassic (Gawlick and Frisch, Reference Gawlick and Frisch2003). Sedimentation resumed with the deposition of radiolarian cherts and radiolaria-rich marls, shales, and limestones of the Ruhpolding Radiolarite Group (Diersche, Reference Diersche1980; Gawlick and Frisch, Reference Gawlick and Frisch2003; Fig. 2).

In the Bajocian the sedimentary evolution in the southern (palaeogeographically southeastern, Fig. 1.4–1.5) part of the Tirolic realm as well as in the Hallstatt realm (Fig. 2) differed from that in the northern part (palaeogeographically in the northwestern, see Fig. 1.4–1.5). Deep-water trench-like basins formed in front of advancing nappes. The first basin group in the southern parts of the Northern Calcareous Alps received mass-flow deposits and large slides up to nappe size, which derived from the Hallstatt Zone (= Hallstatt Mélange; Gawlick and Frisch, Reference Gawlick and Frisch2003). The thickness of the basin fills may reach 2000 meters (Gawlick, Reference Gawlick1996, Reference Gawlick1997, Gawlick et al., Reference Gawlick, Schlagintweit and Suzuki2007b). The nappe stack carrying the Hallstatt Mélange is defined as the upper Tirolic nappe (group) (Frisch and Gawlick, Reference Frisch and Gawlick2003). The second basin group (Fig. 2), the Tauglboden and the Rofan trench-like basins in the north, was subjected to high subsidence and sedimentation rates in the Oxfordian to earliest Kimmeridgian (Schlager and Schlager, Reference Schlager and Schlager1973, Gawlick and Frisch, Reference Gawlick and Frisch2003). The nappe stack carrying the Tauglboden Mélange is defined as the lower Tirolic nappe (Frisch and Gawlick, Reference Frisch and Gawlick2003). These two basin groups are different: the huge mass flows of the Hallstatt Mélange trench-like basins formed earlier from material derived from the outer shelf facing the Neotethys Ocean (Hallstatt Zone, Fig. 1.2–1.5), whereas the Tauglboden Mélange trench-like basin formed later from material derived of the lagoonal part of the Hauptdolomit/Dachstein carbonate platform (Fig. 1.4, 1.5). However, both basins formed syntectonically and suggest a substantial relief between the basin axis and the source area. A third type of radiolarite basin, the Sillenkopf Basin (Missoni et al., Reference Missoni, Steiger and Gawlick2001), remained in the southern part of the Northern Calcareous Alps as a starved basin in the Kimmeridgian (Fig. 2). This basin contains the earliest ophiolitic detritus from the accreted and obducted Neotethys Ocean floor (Missoni, Reference Missoni2003).

In the Tirolic units of the Northern Calcareous Alps the establishment of the shallow-water Plassen Carbonate Platform started at the frontal parts of the rising and advancing nappes (Gawlick et al., Reference Gawlick, Frisch, Missoni and Suzuki2002, Reference Gawlick, Schlagintweit and Missoni2005). From this position, the progradation of several independent platforms took place towards the adjacent radiolarite basins (Gawlick and Frisch, Reference Gawlick and Frisch2003; Gawlick and Schlagintweit, Reference Gawlick and Schlagintweit2006; Gawlick et al., Reference Gawlick, Schlagintweit and Missoni2005, Reference Gawlick, Schlagintweit and Missoni2007a, Reference Gawlick, Missoni, Schlagintweit and Suzuki2012). This resulted in a complex basin-and-rise topography with different types of sediments in shallow-water and deep-water areas (Gawlick and Schlagintweit, Reference Gawlick and Schlagintweit2006). In the Kimmeridgian a huge carbonate platform was formed in the upper Tirolic unit, whereas in the lower Tirolic unit shallow-water carbonates were restricted to its northern part (Gawlick et al., Reference Gawlick, Schlagintweit and Missoni2007a). The whole Plassen Carbonate Platform cycle lasted from the Kimmeridgian until the late early Berriasian platform drowning (Gawlick and Schlagintweit, Reference Gawlick and Schlagintweit2006).

Description of the studied localities

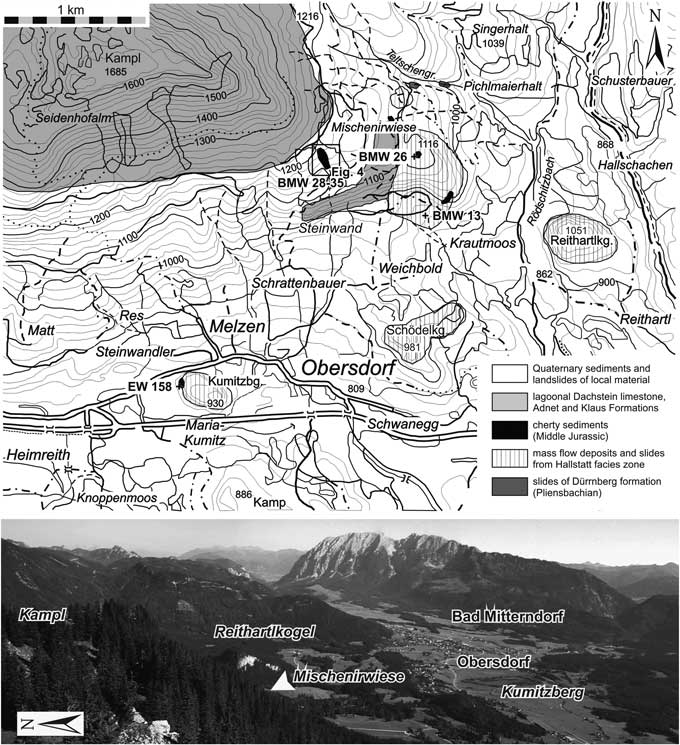

All studied localities belong to the Hallstatt Mélange around the village of Obersdorf north of Bad Mitterndorf (Fig. 3). For a more detailed description of the geology of the area, the Late Triassic to Late Jurassic sedimentary succession, and radiolarian and conodont dating, see O’Dogherty and Gawlick (Reference O’Dogherty and Gawlick2008).

Figure 3 Topography and simplified geology of the study area, showing sample locations (after O’Dogherty and Gawlick, Reference O’Dogherty and Gawlick2008). The plus signs indicate positions of the investigated samples below the Kumitzberg, northwest of Krautmoos, and southeast of the Mischenirwiese and north of the Steinwand. Photo below the map shows the study area as viewed from Mount Kampl to the southwest. The hilly area with dense forest and grassland consists of Jurassic cherty sediments with incorporated mass flows and slides of Hallstatt Limestones. The contact between matrix and blocks or complete sections is visible only in areas with steeper slopes or valleys, or anthropogenic excavations.

Kumitzberg

The Late Triassic Hallstatt Limestone block of Mt. Kumitzberg is surrounded by a grassland area without outcropping sedimentary rocks (Fig. 3). Only small pieces of dark-gray to black radiolarites can be found at the western base of Mt. Kumitzberg. During the reconstruction of a small bus station in the excavation hole the contact between the Hallstatt Limestone block and the underlying dark-gray to black radiolarite was visible. The contact between the Hallstatt Limestone block and the radiolarite is erosive. This clearly indicates that the massive limestone block cut deep into the radiolarite succession. Therefore the age of the radiolarites is slightly older than the time of its emplacement. The unlaminated and massive dark-gray radiolarite beds are intercalated by thin layers of cherty shales. Only one sample (EW-158) was collected from this locality.

Steinwand north

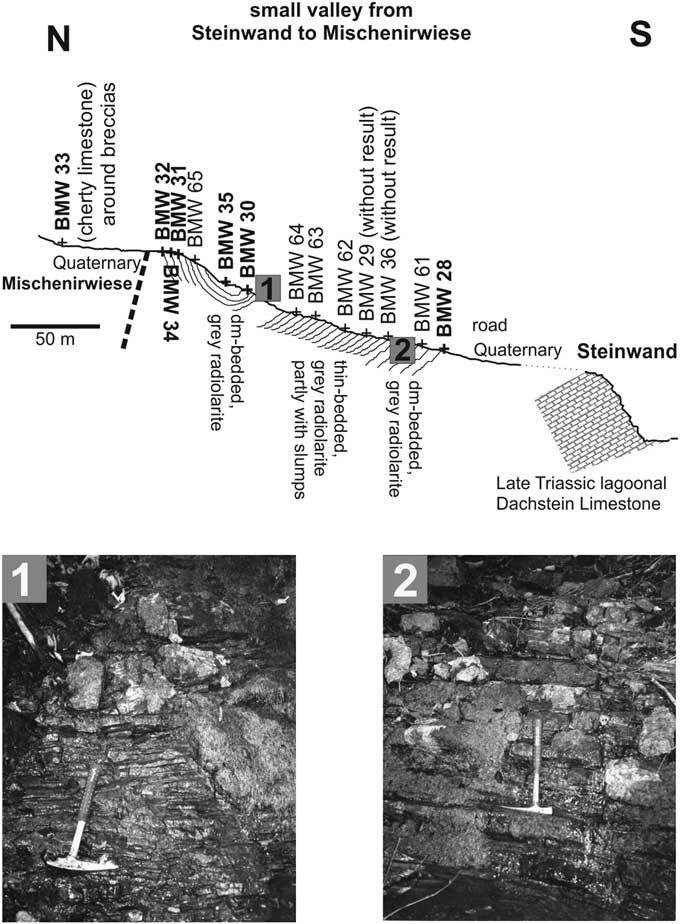

A slightly folded, relative thick radiolarite succession is preserved in a valley between the Steinwand and the Mischenirwiese (Fig. 3), on the southeastern slope of Mount Kampl. This succession occurs on top of the Late Triassic (Rhaetian) lagoonal Dachstein Limestone of the Steinwand (Fig. 4). The overlying Early Jurassic interval is covered by Quaternary deposits, but in rare cases some relics of the red nodular limestones of the Adnet Formation occur in the grassland below the dark-gray bedded radiolarite succession. Lower to Middle Jurassic condensed red limestones are well preserved on the southeastern slope of Mount Kampl on top of the Norian/Rhaetian lagoonal Dachstein Limestone. This series represents the northeastern part of the syncline structure between the Steinwand and Mount Kampl.

Figure 4 Cross-section in the small valley from Steinwand to Mischenirwiese, with the location of studied samples. Pictures 1 and 2 are details of the radiolaritic facies at lower (uppermost Bajocian–lower Bathonian) and upper (Oxfordian–?Kimmeridgian) part, respectively.

The lowermost part of the radiolarite succession (sample BMW-28, Fig. 4) outcrops near the entrance of the valley and yielded the oldest assemblage, whereas the youngest part is preserved in the core of the syncline (sample BMW-35, Fig. 4). The thickness of this black radiolarite succession is nearly 100 meters. Intercalated mass-flow deposits are missing in contrast to equivalent successions to the east. Radiolarian dating proves a continuous radiolarite deposition from Bathonian to the Oxfordian. At the end of the valley, near a spring, a small outcrop of gray bioturbated cherty limestones yielded the youngest radiolarians in this area (sample BMW-33). This clearly demonstrates that the radiolarite succession in the valley is separated from the area of the Mischenirwiese by a young fault.

Area between Krautmoos and Mischenirwiese

The area northwest of Krautmoos (Fig. 3) is characterized by a thick succession of mass-flow deposits with intercalated radiolarite matrix. In a few outcrops, below and between the amalgamated mass-flows matrix, radiolarians are well preserved, mainly in gray massive radiolarites. Two productive samples were taken, one from below the first mass flow (a massive dark-gray radiolarite, BMW-26) and another derived from the higher part of the mass-flow succession (sample BMW-13c).

The components of the different mass-flow deposits consist exclusively of different (gray and red) Hallstatt Limestone components, predominantly of Late Triassic age. Whereas in the lower part of the succession (near the top of the “Krautmoos hill”) the size of the components does not exceed a few decimeters (e.g., near the sample BMW-26), the component size increases upsection. The succession is finally topped by slide blocks of half a kilometer in size, also near Krautmoos. Interestingly in these higher mass-flow deposits radiolarite components occur in addition to the Hallstatt Limestone clasts.

Methods

Samples were selected by examination of thin sections for well-preserved radiolarians. Radiolarite samples were crushed to fragments <2–3 cm in size and placed in 1-liter plastic jars with concentrated hydrochloric acid (32%) until the reaction ceased and all the exposed calcium carbonate was dissolved. Then, the samples were rinsed and processed in the lab with diluted (4%) hydrofluoric acid for a period of 24 hours to extract radiolarians. The samples were wet-sieved through 200-μm and 63-μm sieves and the residues were rinsed and dried in an oven at 40°C. Eleven samples yielded diverse and relatively well-preserved assemblages (see Table 1 for species inventory), in part due to the low thermal overprint of these rocks (estimated by Conodont Color Alteration Index: CAI 1,0, see O’Dogherty and Gawlick, Reference O’Dogherty and Gawlick2008).

Table 1 Chart showing radiolarian taxa occurrences in studied samples; only absence or presence is noted. Solid circles indicate figured specimens; stars indicate unfigured specimens.

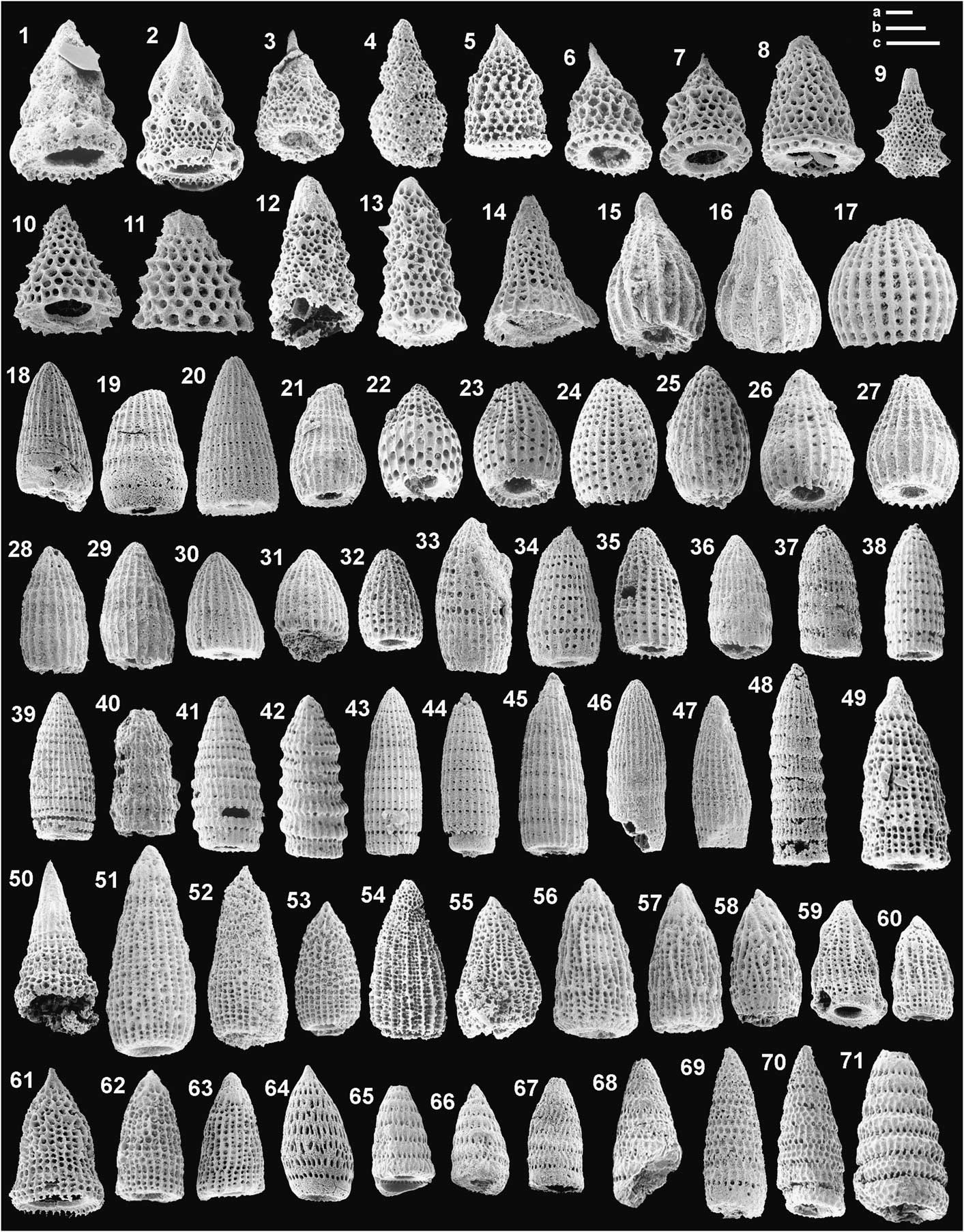

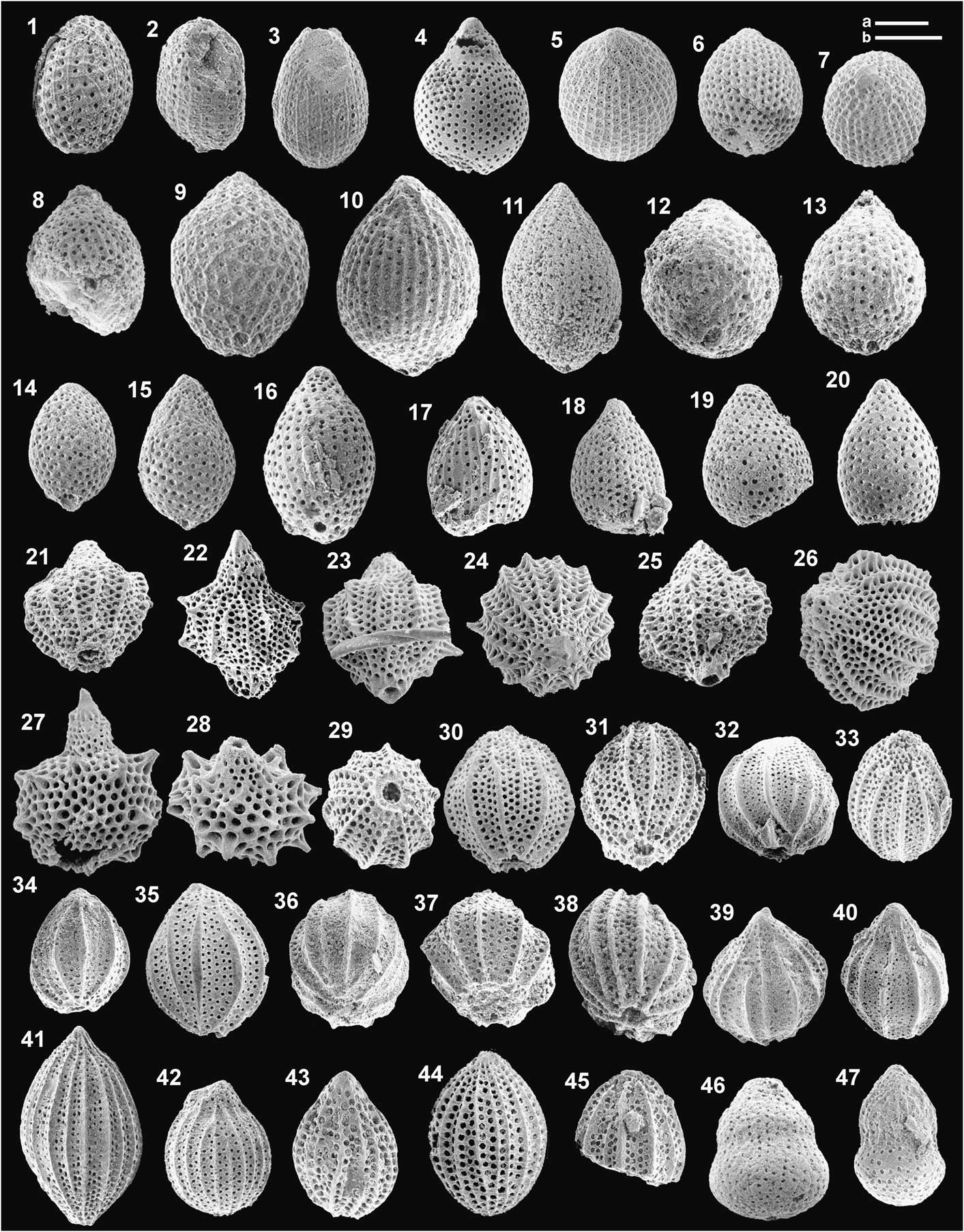

Generic and suprageneric systematics used in this work follows De Wever et al. (Reference De Wever, Dumitrica, Caulet and Caridroit2001) and O’Dogherty et al. (Reference O’Dogherty, Carter, Dumitrica, Goričan, De Wever, Bandini, Baumgartner and Matsuoka2009). Radiolarian taxonomy is based on the Middle Jurassic–Early Cretaceous catalogue of the InterRad Jurassic–Cretaceous Working Group (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, O’Dogherty, Goričan, Dumitrica-Jud, Dumitrica, Pillevuit, Urquhart, Matsuoka, Danelian, Bartolini, Carter, De Wever, Kito, Marcucci and Steiger1995b) for 44 species. Age assignment is based on the Unitary Association Zones (UAZ) established by Baumgartner et al. (Reference Baumgartner, Bartolini, Carter, Conti, Cortese, Danelian, De Wever, Dumitrica, Dumitrica-Jud, Goričan, Guex, Hull, Kito, Marcucci, Matsuoka, Murchey, O’Dogherty, Savary, Vishnevskaya, Widz and Yao1995a), but in order to increase the resolution of this zonation a significant quantity of supplementary species (75 described species and 33 in open nomenclature) are introduced.

Systematic paleontology

Class Radiolaria Müller, Reference Müller1858

Subclass Polycystina Ehrenberg, Reference Ehrenberg1838

Order Nassellaria Ehrenberg, Reference Ehrenberg1876

Monocyrtids

Family Poulpidae De Wever, Reference De Wever1981

Genus Saitoum Pessagno, Reference Pessagno1977a

Type species

Saitoum pagei Pessagno, Reference Pessagno1977a.

Occurrence

Lower Pliensbachian to upper Barremian.

Saitoum pagei Pessagno, Reference Pessagno1977a

1977a Saitoum pagei Reference PessagnoPessagno, p. 98, pl. 12, figs. 11–14.

2003 Saitoum pagei; Reference Dumitrica and ZügelDumitrica and Zügel, p. 28, figs. 16A–B.

2003 Saitoum pagei; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 175, fig. 5.38.

2006 Saitoum pagei; Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and MassonO’Dogherty et al., p. 458, pl. 11, figs. 6–8. [See for complete synonymy]

Saitoum trichylum De Wever, Reference De Wever1981

1981 Saitoum trichylum Reference De WeverDe Wever, p. 11, pl. 1, figs. 5–8.

1995b Saitoum trichylum; Reference Baumgartner, O’Dogherty, Goričan, Dumitrica-Jud, Dumitrica, Pillevuit, Urquhart, Matsuoka, Danelian, Bartolini, Carter, De Wever, Kito, Marcucci and SteigerBaumgartner et al., p. 488, pl. 3021, figs. 1–6. [See for complete synonymy]

2002 Saitoum trichylum; Reference Beccaro, Baumgartner and MartireBeccaro et al., pl. 2, fig. 14.

2003 Saitoum trichylum; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 176, fig. 5.37.

‘Dicyrtids’

Family Gongylothoracidae Bak, Reference Bak1999

Genus Gongylothorax Foreman, Reference Foreman1968

Type species

Dicolocapsa verbeeki Tan, Reference Tan1927.

Occurrence

Upper Bajocian to upper Maastrichtian.

Gongylothorax favosus Dumitrica, Reference Dumitrica1970

1970 Gongylothorax favosus Reference DumitricaDumitrica, p. 56, pl. 1, figs. 1a–c, 2.

1995b Gongylothorax favosus; Reference Baumgartner, O’Dogherty, Goričan, Dumitrica-Jud, Dumitrica, Pillevuit, Urquhart, Matsuoka, Danelian, Bartolini, Carter, De Wever, Kito, Marcucci and SteigerBaumgartner et al., p. 230, pl. 6131, figs. 1–7.

2003 Gongylothorax favosus; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 205, fig. 6.96. [See for complete synonymy]

2009 Gongylothorax favosus favosus; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 180, fig. 5.31A–C, 32A–B; fig. 6.21A–B. [See for complete synonymy]

Gongylothorax marmoris Kiessling in Kiessling and Zeiss, Reference Kiessling and Zeiss1992

1992 Gongylothorax (?) marmoris Reference KiesslingKiessling in Reference Kiessling and ZeissKiessling and Zeiss, p. 190, pl. 2, figs. 8−10.

2003 Gongylothorax cf. marmoris; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, fig. 5.47.

Remarks

Originally this species was questionally attributed to Gongylothorax because the internal structure of the cephalis was not observed, but otherwise all characteristics match with the diagnosis of the genus.

Gongylothorax sp. A

Remarks

The ridges around the hexagonal areas are more elevated in relief than the pores commonly observed in Gongylothorax (see Gongylothorax sp. aff. G. favosus in Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, O’Dogherty, Goričan, Dumitrica-Jud, Dumitrica, Pillevuit, Urquhart, Matsuoka, Danelian, Bartolini, Carter, De Wever, Kito, Marcucci and Steiger1995b, p. 232=Gongylothorax favosus oviformis Suzuki and Gawlick Reference Suzuki and Gawlick2009, p. 180, fig. 5.33A–34C; fig. 6.22A–26B).

Genus Kilinora Hull, Reference Hull1997

Type species

Stylocapsa? spiralis Matsuoka, Reference Matsuoka1982.

Occurrence

Lower Bathonian to middle Callovian.

Kilinora? oblongula (Kocher in Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, De Wever and Kocher1980)

1980 Stylocapsa oblongula Reference KocherKocher in Reference Baumgartner, De Wever and KocherBaumgartner et al., p. 62, pl. 6, fig. 1.

2006 Kilinora (?) oblongula; Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and MassonO’Dogherty et al., p. 443, pl. 8, figs. 25–29. [See for complete synonymy]

2007b Stylocapsa oblongula; Reference Gawlick, Schlagintweit and SuzukiGawlick et al., fig. 17.25.

2013 Kilinora (?) oblongula; Reference Chiari, Baumgartner, Bernoulli, Bortolotti, Marcucci, Photiades and PrincipiChiari et al., fig. 13c.

Remarks

According to O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and Masson2006, the genus is queried because this species does not exhibit a linear arrangement of pores, and clearly lacks costae. It may belong to a new genus.

Kilinora? sp. aff. K. oblongula (Kocher in Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, De Wever and Kocher1980)

Remarks

This form strongly resembles Kilinora (?) oblongula as illustrated by O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Goričan and Dumitrica2006 on pl. 8, figures 25−26, but possesses a somewhat pointed basal appendage.

‘Multicyrtids’

Family Diacanthocapsidae O’Dogherty, Reference O’Dogherty1994

Genus Theocapsomella O’Dogherty, Goričan, and Dumitrica in O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Goričan and Dumitrica2006.

Type species

Theocapsomma cordis Kocher, Reference Kocher1981.

Remarks

This genus was misspelled as Theocapsommella in all descriptions of the species originally included under this genus (O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Goričan and Dumitrica2006). According to ICZN Art. 24.2.3, the selection of the correct original spelling should be Theocapsomella. This was the original name followed by the expression n. gen. (O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and Masson2006, p. 454) and was also fixed as the correct original spelling by the first reviser (O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Carter, Dumitrica, Goričan, De Wever, Bandini, Baumgartner and Matsuoka2009).

In the original description (O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and Masson2006), Theocapsomella included also some four-segmented nassellarians (e.g., Stichocapsa himedaruma Aita). On the other hand, a phylogenetic relationship of Stichocapsa himedaruma Aita and Stichocapsa convexa Yao was also assumed (see O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and Masson2006, p. 441). New findings are in favor of the latter opinion (see Šegvić et al., Reference Šegvić, Kukoć, Dragičević, Vranjković, Brčić, Goričan, Babajić and Hrvatović2014, pl. 1, figs. 21, 22).

Occurrence

Lower Bathonian to lower Berriasian.

Theocapsomella cordis (Kocher in Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, De Wever and Kocher1980)

1980 Stylocapsa cordis Reference KocherKocher in Reference Baumgartner, De Wever and KocherBaumgartner et al., p. 62, pl. 6, fig. 1.

2006 Theocapsommella cordis; Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and MassonO’Dogherty et al., p. 443, pl. 8, figs. 25–29. [See for complete synonymy]

2009 Theocapsomma cordis; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 181, figs. 5.37A–B, 6.28A–B.

2013 Theocapsomella cordis; Reference Chiari, Baumgartner, Bernoulli, Bortolotti, Marcucci, Photiades and PrincipiChiari et al., fig. 14e.

Theocapsomella medvednicensis (Goričan in Halamić et al., Reference Halamić, Goričan, Slovenec and Kolar-Jurkovsek1999)

1999 Theocapsomma medvednicensis Reference GoričanGoričan in Reference Halamić, Goričan, Slovenec and Kolar-JurkovsekHalamić et al., p. 37, pl. 1, figs. 12–16.

2003 Theocapsomma medvednicensis; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 206, fig. 6.87.

2006 Theocapsommella medvednicensis (Goričan); Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and MassonO’Dogherty et al., p. 456, pl. 8, figs. 30, 33–37. [See for complete synonymy]

2008 Theocapsomma sp. aff. T. medvednicensis; Reference Baumgartner, Flores, Bandini, Girault and CruzBaumgartner et al., pl. 4, fig. 10.

2009 Theocapsomma medvednicensis; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 181, figs. 5.38A–B.

Family Minocapsidae new family

Type genus

Minocapsa Matsuoka, Reference Matsuoka1991a.

Other genera

Crococapsa new genus; Doliocapsa new genus; Hemicryptocephalis Li, Reference Li1988; Hiscocapsa O’Dogherty, Reference O’Dogherty1994; Praewilliriedellum Kozur, Reference Kozur1984 (syn. Hemicryptocephalis); and Quarkus Pessagno, Blome, and Hull in Pessagno et al., Reference Pessagno, Blome, Hull and Six1993.

Diagnosis

Pyriform to ovoidal shell consisting in usually four segments. Last segment with or without an aperture. Lattice shell composed of small rounded to large polygonal pore frames.

Etymology

After type genus.

Occurrence

Early Pliensbachian to Middle Albian.

Remarks

This family is erected for genera included in the unnamed family pro Stichocapsidae used by O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Carter, Dumitrica, Goričan, De Wever, Bandini, Baumgartner and Matsuoka2009. The genus Aitaum Pessagno and Hull, Reference Pessagno and Hull2002 is an exception because it has a multisegmented test composed of three to four post-abdominal segments. Aitaum has more affinity with the genus Lantus Yeh, Reference Yeh1987a and other eucyrtidiid-type nassellarians.

Genus Crococapsa new genus

Type species

Sethocapsa hexagona Hori, Reference Hori1999.

Other species

Cyrtocapsa asseni Tan, Reference Tan1927; Minocapsa aitai Hull, Reference Hull1997; Minocapsa truncata Wu, Reference Wu2000; Minocapsa? tansinhoki Hull, Reference Hull1997; Sethocapsa accincta Steiger, Reference Steiger1992; Sethocapsa horokanaiensis Kawabata, Reference Kawabata1988; Sethocapsa kitoi Jud, Reference Jud1994; Sethocapsa lagenaria Wu and Li, Reference Wu and Li.1982; Sethocapsa pseudouterculus Aita in Aita and Okada, Reference Aita and Okada1986; Sethocapsa? subcrassitestata Aita in Aita and Okada, Reference Aita and Okada1986; Sethocapsa? zweilii Jud, Reference Jud1994; Sethocapsa hashimotoi Tumanda, Reference Tumanda1989; Theocapsa simplex Tan, Reference Tan1927; and Theocapsa uterculus Parona, Reference Parona1890.

Diagnosis

Tetracyrtid nassellarian having a globose postabdominal segment. Lattice meshwork with polygonal pore frames lacking nodes or tubercles on its surface. Closed antapically or having a discrete number of small pores grouped into a depression (see Sethocapsa uterculus in Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, O’Dogherty, Goričan, Dumitrica-Jud, Dumitrica, Pillevuit, Urquhart, Matsuoka, Danelian, Bartolini, Carter, De Wever, Kito, Marcucci and Steiger1995b, p. 505, pl. 5462, fig. 2). Collar and lumbar strictures slightly recognizable or indistinct externally. Large and globose postabdominal segment is well distinguished from the abdomen by a marked stricture.

Etymology

From the latin croco (saffron) and capsa (box); feminine gender.

Occurrence

Bathonian to middle Albian.

Remarks

O’Dogherty (Reference O’Dogherty1994) erected the genus Hiscocapsa for a heterogeneous group of tetracyrtid nassellarians displaying a wide variety of pore frame arrangement. However, many species assigned originally to Hiscocapsa are clearly separated by lacking a distal aperture and bearing no tubercles on the surface.

Crococapsa n. gen. differs from Minocapsa Matsuoka, Reference Matsuoka1991a, by its distinct fourth segment, which is globose and well differentiated from the abdomen by a marked stricture. Crococapa n. gen. also differs from Lantus Yeh, Reference Yeh1987a by having only one postabdominal chamber.

Crococapsa tansinhoki (Hull, Reference Hull1997)

1997 Minocapsa(?) tansinhoki Reference HullHull, p. 148, pl. 38, figs. 4, 6.

2006 Minocapsa(?) tansinhoki; O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and Masson2006, p. 444, pl. 6, figs. 16, 17. [See for complete synonymy]

Remarks

O’Dogherty et al. (Reference O’Dogherty, Goričan and Dumitrica2006, p. 444) first questioned the placement of this species to Minocapsa because the basal aperture was absent and the phylogentic relationship with early Jurassic representatives was not demonstrated. This species fits well in the general description of the new genus Crococapsa.

Crococapsa sp. aff. C. tansinhoki (Hull, Reference Hull1997)

Remarks

These forms differ from Hull’s material by having smaller and more numerous pores on the abdomen.

Crococapsa sp. aff. C. truncata (Wu, Reference Wu2000)

aff. 2000 Minocapsa truncata Reference WuWu, p. 304, pl. 2, figs. 1, 5–6.

Remarks

This specimen differs from the Tibetan specimens by displaying a proportionally larger last segment.

Crococapsa sp. A

Remarks

These specimens resemble Crococapsa sp. aff. C. truncata (Wu, Reference Wu2000), but the proximal part of the shell is relatively longer and elongated.

Crococapsa sp. B

Remarks

This specimen is closely related to other congeneric forms included in this paper, but differs by the well-marked polygonal pore frames on almost all the shell surface.

Crococapsa sp. C

Remarks

These specimens are very close to Crococapsa tansinhoki but they display more cylindrical and smoother thorax.

Genus Doliocapsa new genus

Type species

Stichomitra (?) stecki O’Dogherty, Goričan, and Dumitrica in O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Goričan and Dumitrica2006.

Other species

Hiscocapsa acuta Hull, Reference Hull1997; Hiscocapsa minuta Yeh, Reference Yeh2011; Hiscocapsa planata Wu, Reference Wu2000 (syn. Stichocapsa magnipora); Sethocapsa lugeoni O’Dogherty, Goričan, and Dumitrica in O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Goričan and Dumitrica2006; Sethocapsa taukhaensis Kemkin and Taketani, Reference Kemkin and Taketani2004; Solenotryma keni Kocher, Reference Kocher1981; Stichocapsa magnipora Chiari, Marcucci, and Prela, Reference Chiari, Marcucci and Prela2002; Stichomitra doliolum Aita in Aita and Okada, Reference Aita and Okada1986; and ?Quarticella hunzikeri O’Dogherty, Goričan, and Dumitrica in O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Goričan and Dumitrica2006.

Diagnosis

Shell with four segments (rarely more), generally thick-walled. Cephalis small, spherical, poreless, without apical horn. Other segments latticed with polygonal pore frames and lacking tubercles or nodes. Last segment somewhat inflated and having an aperture.

Etymology

From dolium (barrel) and capsa (box); feminine gender.

Occurrence

Lower Toarcian to Tithonian.

Remarks

This new genus is differentiated from Praewilliriedellum Kozur, Reference Kozur1984, by having very distinct strictures and well-differentiated segments.

Doliocapsa matsuokai (Yeh, Reference Yeh2009)

1998 Stichocapsa sp. F Reference ArakawaArakawa, p. 63, pl. 6, fig. 274.

2005 Stichocapsa sp. Reference Šmuc and GoričanŠmuc and Goričan, pl. 3, figs. 22a−b.

2009 Hiscocapsa matsuokai Reference YehYeh, p. 67, pl. 21, figs. 1, 8, 20, 22.

2011 Hiscocapsa matsuokai; Reference YehYeh, p. 16, pl. 7, figs. 10−13.

2011 Hiscocapsa cf. matsuokai; Reference YehYeh, p. 16, pl. 5−7.

Remarks

The proximal part in our specimens is slightly longer than in the type material. This species differs from all others representatives herein illustrated by having smaller and more numerous polygonal pores, less marked strictures at joints, and longer proximal conical part.

Doliocapsa keni (Kocher, Reference Kocher1981)

1981 Solenotryma keni Reference KocherKocher, p. 91, pl. 16, figs. 11−12.

2006 Stichomitra (?) keni (Kocher); Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and MassonO’Dogherty et al., p. 442, pl. 5, fig. 6.

Doliocapsa planata (Wu, Reference Wu2000)

2000 Hiscocapsa planata Reference WuWu, p. 303, pl. 1, figs 7–8.

2002 Stichocapsa magnipora Chiari, Marcucci and Prela, p. 76, pl. 3, figs. 13−17.

Genus Hiscocapsa O’Dogherty, Reference O’Dogherty1994

Type species

Cyrtocapsa grutterinki Tan, Reference Tan1927.

Other species

Sethocapsa aitai Chiari, Marcucci, and Prela, Reference Chiari, Marcucci and Prela2002; Sethocapsa kodrai Chiari, Marcucci, and Prela, Reference Chiari, Marcucci and Prela2002; Stichocapsa pseudornata Tan, Reference Tan1927; and Stichocapsa rutteni Tan, Reference Tan1927.

Emended diagnosis

Hiscocapsa is emended in order to include only tetracyrtid nassellarians having a globose postabdominal segment with tubercles. A large distal aperture is also presented and sometimes, when preserved, an appendage. We note that terminally closed species with tubercles (e.g., Sethocapsa kaminogoensis Aita in Aita and Okada, Reference Aita and Okada1986; Sethocapsa spp., pl. 5, fig. 15 in Aita and Okada, Reference Aita and Okada1986; Sethocapsa sp. 8, pl. 2, fig. 32 in Matsuoka, Reference Matsuoka1998) should belong to a new genus, which is not described herein.

Occurrence

Upper Bathonian to upper Aptian.

Hiscocapsa kodrai (Chiari, Marcucci, and Prela, Reference Chiari, Marcucci and Prela2002)

2002 Sethocapsa kodrai Reference Chiari, Marcucci and PrelaChiari, Marcucci and Prela, p. 74, pl. 3, figs. 1−7.

2003 Quarticella ovalis Takemura; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 199, fig. 5.40.

2005non Sethocapsa kodrai; Reference Nakae and KomuroNakae and Komuro, fig. 4.47.

2012 Hiscocapsa kodrai; Reference Djerić, Schmid and GerzinaDjeric et al., pl. 1, fig. 23.

Remarks

This species is very similar to Quarticella ovalis Takemura, but its aperture is much narrower. The larger postabdominal segment also displays well-differentiated tubercles instead of the typical spiny surface of Quarticella ovalis. Hiscocapsa kodrai might belong to Quarticella, but study of the internal structure is required before this new generic assignation is proposed. In the type material, a flattened base with a constricted aperture is clearly distinct (see Chiari et al., Reference Chiari, Marcucci and Prela2002, pl. 3, fig. 3). This flattened base is never present in representatives of Quarticella.

Genus Praewilliriedellum Kozur, Reference Kozur1984

Type species

Praewilliriedellum cephalospinosum Kozur, Reference Kozur1984.

Other species

Stichocapsa? pseudoconvexa Kemkin and Taketani, Reference Kemkin and Taketani2004; Stichocapsa convexa Yao, Reference Yao1979; Stichocapsa robusta Matsuoka, Reference Matsuoka1984; and Theocorys renzae Schaaf, Reference Schaaf1981.

Emended diagnosis

Praewilliriedellum is emended in order to allocate clear tetracyrtid forms (e.g., Stichocapsa robusta Matsuoka). Many representatives of this genus have an abdomen partially encased in the postabdominal segment, making it hard to differentiate externally. The degree of encasement is nevertheless much lower than in Williriedellum and other genera assigned to Williriedellidae.

Occurrence

Upper Aalenian to upper Barremian.

Praewilliriedellum convexum (Yao, Reference Yao1979)

1979 Stichocapsa convexa Reference YaoYao, p. 35, pl. 5, figs. 14–16; pl. 6, figs. 1–7.

2003 Stichocapsa convexa; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 212, fig. 6.51.

2006 Stichocapsa convexa; Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and MassonO’Dogherty et al., p. 441, pl. 6, fig. 35. [See for complete synonymy]

2007b Stichocapsa convexa; Reference Gawlick, Schlagintweit and SuzukiGawlick et al., figs. 7.15, 8.32, 17.23, 18.10.

2008 Praewilliriedellum convexum; Reference Beccaro, Diserens, Goričan and MartireBeccaro et al., pl. 2, fig. 26.

2009 Stichocapsa convexa; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 186, figs. 5.54A–B.

2013 Praewilliriedellum convexum; Reference Chiari, Baumgartner, Bernoulli, Bortolotti, Marcucci, Photiades and PrincipiChiari et al., fig. 13n.

Praewilliriedellum robustum (Matsuoka, Reference Matsuoka1984)

1984 Stichocapsa robusta Reference MatsuokaMatsuoka, p. 146, pl. 1, figs. 6–13; pl. 2, figs. 7–12.

2003 Stichocapsa robusta; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 213, fig. 5.44.

2006 Stichocapsa robusta; Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and MassonO’Dogherty et al., p. 441, pl. 6, figs. 31–34. [See for complete synonymy]

2007b Stichocapsa robusta; Reference Gawlick, Schlagintweit and SuzukiGawlick et al., fig. 8.34.

2008 Praewilliriedellum robustum; Reference Beccaro, Diserens, Goričan and MartireBeccaro et al., pl. 2, fig. 27.

2013 Praewilliriedellum robustum; Reference Chiari, Baumgartner, Bernoulli, Bortolotti, Marcucci, Photiades and PrincipiChiari et al., fig. 13p.

Genus Quarkus Pessagno, Blome, and Hull in Pessagno et al., Reference Pessagno, Blome, Hull and Six1993

Type species

Quarkus madstonensis Pessagno, Blome, and Hull in Pessagno et al., Reference Pessagno, Blome, Hull and Six1993.

Other species

Stichocapsa japonica Yao, Reference Yao1979.

Occurrence

Lower Bajocian to upper Callovian. A very similar specimen, but questionable to this genus, was found in upper Berriasian material of the Mariana Trench (Stichocapsa sp. 8 Matsuoka, Reference Matsuoka1998, pl. 2, fig. 24). We do not assign this species to Quarkus because continuous record from the Callovian to the Berriasian has not been demostrated yet.

Quarkus japonicus (Yao, Reference Yao1979)

1979 Stichocapsa japonica Reference YaoYao, p. 36, pl. 6, figs. 8−12; pl. 7, figs. 1−15.

2006 Stichocapsa japonica; Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and MassonO’Dogherty et al., p. 441, pl. 6, fig. 6. [See for complete synonymy]

2009 Stichocapsa japonica; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 186, figs. 5.53.

2012 Praewilliriedellum japonicum; Reference Goričan, Pavšič and RožičGoričan et al., pl. 1, fig. 20.

2013 Praewilliriedellum japonicum; Reference Chiari, Baumgartner, Bernoulli, Bortolotti, Marcucci, Photiades and PrincipiChiari et al., fig. 13o.

Remarks

This species has always been assigned to the genus Stichocapsa (considered as a nomen dubium by O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Carter, Dumitrica, Goričan, De Wever, Bandini, Baumgartner and Matsuoka2009, p. 330), however we note that this commonly illustrated species is very close to Quarkus madstonensis, the only difference being the less-expanded fourth segment. Judging from the stratigraphic distribution, Quarkus japonicus may be the ancestor of Quarkus madstonensis. An intermediate form (Stichocapsa sp. aff. S. japonica Yao) was illustrated by Chiari et al., Reference Chiari, Marcucci and Prela2002 (pl. 3, figs. 18−22) from the upper Bajocian−lower Bathonian of Albania.

Quarkus madstonensis Pessagno, Blome, and Hull in Pessagno et al., Reference Pessagno, Blome, Hull and Six1993

1993 Quarkus madstonensis Reference Pessagno, Blome and HullPessagno, Blome, and Hull in Reference Pessagno, Blome and HullPessagno et al., p. 159, pl. 8, figs. 9, 13–15, 24.

2006 Williriedellum madstonense; Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and MassonO’Dogherty et al., p. 446, pl. 6, figs. 9–10.

2008 Williriedellum madstonense; Reference Danelian, Asatryan, Sosson, Person, Sahakyan and GaloyanDanelian et al., pl. 1, fig. 11.

Family Arcanicapsidae Takemura, Reference Takemura1986

Subfamily Arcanicapsinae Takemura, Reference Takemura1986

Included genera

Arcanicapsa Takemura, Reference Takemura1986; Fultacapsa Ožvoldová in Ožvoldová and Frantová, Reference Ožvoldová and Frantová1997; Religa Whalen and Carter, Reference Whalen and Carter2002; Squinabollum Dumitrica, Reference Dumitrica1970; Trisyringium Vinassa de Regny, Reference Vinassa de Regny1901; and the group of species assigned to Dorypyle Squinabol, Reference Squinabol1904. Dorypyle should be regarded as a nomen dubium that requires a new genus for taxonomic stability.

The genera Arcanicapsa Takemura, Reference Takemura1986 and Yamatoum Takemura, Reference Takemura1986 were questionably placed under this family in the recent revision by O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Carter, Dumitrica, Goričan, De Wever, Bandini, Baumgartner and Matsuoka2009, but, as stated by Takemura Reference Takemura1986, the cephalic structure has more affinities with the genus Unuma Ichikawa and Yao, Reference Ichikawa and Yao1976. In this paper we follow the same opinion. In the same revision by O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Carter, Dumitrica, Goričan, De Wever, Bandini, Baumgartner and Matsuoka2009, the genus Solidea Whalen and Carter in Carter et al., Reference Carter, Whalen and Guex1998 was erroneously placed in this subfamily, but its correct placement should be in Favosyringiinae.

Genus Arcanicapsa Takemura, Reference Takemura1986

Type species

Arcanicapsa sphaerica Takemura, Reference Takemura1986.

Other species

Sethocapsa aculeata Cortese, Reference Cortese1993; Sethocapsa congduensis Li and Wu, Reference Li and Wu1985; Sethocapsa echinata Li and Wu, Reference Li and Wu1985; Sethocapsa leiostraca Foreman, Reference Foreman1973b; Sethocapsa trachyostraca Foreman, Reference Foreman1973b; Sethocapsa funatoensis Aita, Reference Aita1987; and Zhamoidellum? exquisita Hull, Reference Hull1997.

Occurrence

Lower Toarcian to lower Aptian.

Remarks

Arcanicapsa as originally described has a stout apical horn (Takemura Reference Takemura1986, p. 54). In this paper we broaden the definition to include morphologically closely similar species without apical horn. Such tricyrtids, having a closed abdomen ornamented with spines or nodes, have been traditionally ascribed to Sethocapsa (e.g., Sethocapsa funatoensis Aita), which is considered nomen dubium (O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Carter, Dumitrica, Goričan, De Wever, Bandini, Baumgartner and Matsuoka2009). Some species were questionably assigned to Zhamoidellum (e.g., Zhamoidellum? exquisita Hull). Here we assign to Zhamoidellum only species without tubercles (see discussion under Zhamoidellum). Species with a clear distinction between upward-directed spines proximally and downward-directed spines distally belong to Trisyringium Vinassa de Regny (see O’Dogherty, Reference O’Dogherty1994, p. 208; O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Carter, Dumitrica, Goričan, De Wever, Bandini, Baumgartner and Matsuoka2009).

Arcanicapsa exquisita (Hull, Reference Hull1997)

1997 Zhamoidellum (?) exquisita Reference HullHull, p. 132, pl. 38, figs. 5, 16–17, 21.

2000 Zhamoidellum (?) exquisita; Reference WuWu, pl. 1, figs. 14–15.

2003 Zhamoidellum exquisita; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 204, fig. 6.55.

Arcanicapsa funatoensis (Aita, Reference Aita1987)

1987 Sethocapsa funatoensis Reference AitaAita, p. 73, pl. 2, figs. 6a–7b.

2005b Arcanicapsa funatoensis; Reference Nishihara and YaoNishihara and Yao, fig. 5.1.

2006 Zhamoidellum funatoense; Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and MassonO’Dogherty et al., p. 445, pl. 10, fig. 32. [See for complete synonymy]

2009 non Zhamoidellum funatoense; Reference YehYeh, p. 68, pl. 21, figs. 10–11, 17, 25.

2011 Hiscocapsa funatoense; Reference YehYeh, p. 16, pl. 7, figs. 19–20, 23, 26.

Arcanicapsa sp. aff. A. funatoensis (Aita, Reference Aita1987)

Remarks

The specimens resemble A. funatoensis, but differ by having stronger spines and larger shell size.

Arcanicapsa undulata (Heitzer, Reference Heitzer1930)

1930 Lithobotrys undulata Reference HeitzerHeitzer, p. 390, pl. 28, fig. 22.

2003 Tricolocapsa undulata; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, figs. 5.41, 6.39.

2006 Tricolocapsa undulata; Reference Auer, Gawlick and SuzukiAuer et al., fig. 6.44.

2007b Tricolocapsa undulata; Reference Gawlick, Schlagintweit and SuzukiGawlick et al., fig. 8.41.

2008 Tricolocapsa undulata; Reference Auer, Gawlick, Suzuki and SchlagintweiAuer et al., fig. 9.78.

2009 Tricolocapsa undulata; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 183, figs. 5.44A–B, 5.45A–B, 6.18A–B, 6.19A–B.

Remarks

Arcanicapsa undulata differs from A. funatoensis by having a smoother surface. Circular pores are present only on tubercles.

Arcanicapsa sp. A

Remarks

This specimen is similar to Arcanicapsa exquisita but possesses a smaller abdomen; the constriction between thorax and abdomen (lumbar stricture) is less pronounced.

Subfamily Favosyringiinae Steiger, Reference Steiger1992

Genus Spinosicapsa Ožvoldová, Reference Ožvoldová1975

Type species

Spinosicapsa ceblienica Ožvoldová, Reference Ožvoldová1975.

Occurrence

Upper Carnian to lower Aptian.

Spinosicapsa basilica (Hull, Reference Hull1997)

1997 Podobursa basilica Reference HullHull, p. 100, pl. 41, figs. 7–8, 10, 18, 20–21.

Spinosicapsa lata (Yang, Reference Yang1993)

1993 Syringocapsalata lata Reference YangYang, p. 132, pl. 24, figs. 1–2, 16, 20–21; pl. 26, figs. 7, 11, 15.

1997 Podobursa lata; Reference HullHull, p. 102, pl. 42, fig. 6.

2007b Syringocapsa lata; Reference Gawlick, Schlagintweit and SuzukiGawlick et al., fig. 19.37.

Spinosicapsa spinosa (Ožvoldová, Reference Ožvoldová1975)

1975 Heitzeria spinosa Reference OžvoldováOžvoldová, p. 78, pl. 101, fig. 2.

1995b Podobursa spinosa; Reference Baumgartner, O’Dogherty, Goričan, Dumitrica-Jud, Dumitrica, Pillevuit, Urquhart, Matsuoka, Danelian, Bartolini, Carter, De Wever, Kito, Marcucci and SteigerBaumgartner et al., p. 426, pl. 3230, figs. 1–4. [See for complete synonymy]

Spinosicapsa sp. cf. S. triacantha (Fischli, Reference Fischli1916)

2006Podobursa triacantha; Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and MassonO’Dogherty et al., p. 437, pl. 7, fig. 4. [See for complete synonymy]

Remarks

The assignment to S. triacantha is queried because the lateral spines are broken off in this specimen.

Family Eucyrtidiellidae Takemura, Reference Takemura1986

Genus Eucyrtidiellum Baumgartner, Reference Baumgartner1984

Type species

Eucyrtidium? unumaensis Yao, Reference Yao1979.

Occurrence

Lower Pliensbachian to upper Tithonian.

Eucyrtidiellum nodosum Wakita, Reference Wakita1988

1988 Eucyrtidiellum nodosum Reference WakitaWakita, p. 408, pl. 4, fig. 29; pl. 5, fig. 16.

2003 Eucyrtidiellum nodosum; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 217, figs. 5.20, 6.24–6.25, 6.29.

2006 Eucyrtidiellum nodosum; Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and MassonO’Dogherty et al., p. 442, pl. 3, fig. 3. [See for complete synonymy]

2007b Eucyrtidiellum nodosum; Reference Gawlick, Schlagintweit and SuzukiGawlick et al., fig. 8.9; fig. 17.8.

Eucyrtidiellum ptyctum (Riedel and Sanfilippo, Reference Riedel and Sanfilippo1974)

1974 Eucyrtidium ptyctum Reference Riedel and SanfilippoRiedel and Sanfilippo, p. 778, pl. 5, fig. 7; pl. 12, fig. 14, not fig. 15.

2003 Eucyrtidiellum ptyctum; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 218, figs. 6.26–6.27.

2006 Eucyrtidiellum ptyctum; Reference Gawlik, Suzuki and SchlagintweitGawlick et al., figs. 8.10, 9.7.

2006 Eucyrtidiellum ptyctum; Reference Auer, Gawlick and SuzukiAuer et al., fig. 6.14.

2006 Eucyrtidiellum ptyctum; Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and MassonO’Dogherty et al., p. 442, pl. 3, figs. 1–2. [See for complete synonymy]

2007b Eucyrtidiellum ptyctum; Reference Gawlick, Schlagintweit and SuzukiGawlick et al., fig. 7.3; fig. 19.18.

2009 Eucyrtidiellum ptyctum; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 188, fig. 5.63.

Eucyrtidiellum pustulatum Baumgartner, Reference Baumgartner1984

1984 Eucyrtidiellum pustulatum Reference BaumgartnerBaumgartner, p. 765, pl. 4, figs. 4–5.

2003 Eucyrtidiellum unumaense pustulatum; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 217, figs. 5.20, 6.24–6.25, 6.29. [See for complete synonymy]

2007b Eucyrtidiellum unumaense pustulatum; Reference Gawlick, Schlagintweit and SuzukiGawlick et al., figs. 8.13, 17.12.

Eucyrtidiellum pyramis (Aita in Aita and Okada, Reference Aita and Okada1986)

1986 Eucyrtidium (?) pyramis Reference AitaAita in Reference Aita and OkadaAita and Okada, p. 109, pl. 6, figs. 8–13; pl. 7, figs. 1a–b.

1995b Eucyrtidiellum pyramis; Reference Baumgartner, O’Dogherty, Goričan, Dumitrica-Jud, Dumitrica, Pillevuit, Urquhart, Matsuoka, Danelian, Bartolini, Carter, De Wever, Kito, Marcucci and SteigerBaumgartner et al., p. 216, pl. 3019, figs. 1–2. [See for complete synonymy]

2010 Eucyrtidiellum pyramis; Reference Robin, Goričan, Guillocheau, Razin, Dromart and MosaffaRobin et al., fig. 4.14.

Eucyrtidiellum unumaense (Yao, Reference Yao1979)

1979 Eucyrtidium (?) unumaensis Reference YaoYao, p. 39, pl. 9, figs. 1–11.

2003 Eucyrtidiellum unumaense unumaense; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 216, fig. 6.28.

2006 Eucyrtidiellum unumaense; Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and MassonO’Dogherty et al., p. 443, pl. 3, figs. 4–6. [See for complete synonymy]

2007b Eucyrtidiellum unumaense unumaense; Reference Gawlick, Schlagintweit and SuzukiGawlick et al., figs. 7.5, 17.11, 19.19.

2009 Eucyrtidiellum unumaense; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 188, fig. 5.62.

Superfamily Williriedelloidea Dumitrica, Reference Dumitrica1970

Family Williriedellidae Dumitrica, Reference Dumitrica1970

Genus Hemicryptocapsa Tan, Reference Tan1927

Type species

Hemicryptocapsa capita Tan, Reference Tan1927.

Other species

Hemicryptocapsa nonaginta new species; Praezhamoidellum yaoi Kozur, Reference Kozur1984; Praezhamoidellum buekkense Kozur, Reference Kozur1984; Tricolocapsa tetragona Matsuoka, Reference Matsuoka1983; Williriedellum? marcuccii Cortese, Reference Cortese1993; Williriedellum carpathicum Dumitrica, Reference Dumitrica1970.

Emended diagnosis

Cryptothoracic tricyrtids lacking nodose outer surface are included in this genus. The shell surface can be ornamented with regular pore frames as in the type species, or smooth as in Hemicryptocapsa buekkensis. Also see extended discussion under the genus Williriedellum.

Occurrence

Upper Tithonian to upper Aptian.

Hemicryptocapsa buekkensis (Kozur, Reference Kozur1984)

1984 Praezhamoidellum buekkenses Reference KozurKozur, p. 54, pl. 3, figs. 1a−b.

1998 Tricolocapsa? bukkense; Reference CordeyCordey, p. 128, pl. 27, fig. 9.

2006 Williriedellum buekkense; Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and MassonO’Dogherty et al., p. 446, pl. 9, figs. 1−3

2008 Williriedellum buekkense; Reference Auer, Gawlick, Suzuki and SchlagintweiAuer et al., fig. 9.52.

2009 Praezhamoidellum buekkense; Reference Gawlick, Missoni, Schlagintweit, Suzuki, Frisch, Krystyn, Blau and LeinGawlick et al., figs. 5.50A–B.

2012 Hemicryptocapsa buekkensis; Reference Goričan, Pavšič and RožičGoričan et al., pl. 1, figs. 26, 34.

2012 Williriedellum buekkense; Reference Djerić, Schmid and GerzinaDjerić et al., pl. 3, fig. 2.

Hemicryptocapsa carpathica (Dumitrica, Reference Dumitrica1970)

1970 Williriedellum carpathicum Reference DumitricaDumitrica, p. 70, pl. 9, figs. 56a−b; 57−59; pl. 10, fig. 61.

1995b Williriedellum carpathicum; Reference Baumgartner, O’Dogherty, Goričan, Dumitrica-Jud, Dumitrica, Pillevuit, Urquhart, Matsuoka, Danelian, Bartolini, Carter, De Wever, Kito, Marcucci and SteigerBaumgartner et al., p 626, pl. 4055, figs. 1−3.

2003 Williriedellum carpathicum; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 200, fig. 6.74. [See for complete synonymy]

2008 Williriedellum carpathicum; Reference Beccaro, Diserens, Goričan and MartireBeccaro et al., pl. 3, fig. 29.

2012 Hemicryptocapsa carpathica; Reference Goričan, Pavšič and RožičGoričan et al., pl. 2, fig. 20.

Hemicryptocapsa marcucciae (Cortese, Reference Cortese1993)

1993 Williriedellum (?) marcuccii Reference CorteseCortese, p. 180, pl. 7, figs. 6−7.

2006 Williriedellum marcucciae; Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and MassonO’Dogherty et al., p. 446, pl. 9, figs. 28−36. [See for complete synonymy]

2008 Williriedellum marcucciae; Reference Auer, Gawlick, Suzuki and SchlagintweiAuer et al., fig. 11.46.

2008 Williriedellum (?) marcucciae; Reference Beccaro, Diserens, Goričan and MartireBeccaro et al., pl. 3, fig. 30.

2009 Williriedellum marcucciae; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, fig. 5.25; fig. 6.28.

2010 Williriedellum marcucciae; Reference Robin, Goričan, Guillocheau, Razin, Dromart and MosaffaRobin et al., pl. 3, fig. 11.

2014 Hemicryptocapsa marcucciae; Reference Šegvić, Kukoć, Dragičević, Vranjković, Brčić, Goričan, Babajić and HrvatovićŠegvić et al., pl. 1, figs. 28A–B.

Remarks

Like other species in this paper, the absence of tubercles or nodes on the surface of this species justifies the transfer from Williriedellum to Hemicryptocapsa.

Hemicryptocapsa nonaginta new species

1993 Tricolocapsa(?) sp A. Reference Pessagno, Blome and HullPessagno et al., p. 160, pl. 8, fig. 27.

1995b Tricolocapsa sp. S Reference Baumgartner, O’Dogherty, Goričan, Dumitrica-Jud, Dumitrica, Pillevuit, Urquhart, Matsuoka, Danelian, Bartolini, Carter, De Wever, Kito, Marcucci and SteigerBaumgartner et al., p. 602, pl. 4057, figs. 1−3.

2004 Tricolocapsa sp. S; Reference Ziabrev, Aitchison, Abrajevitch, Badengzhu, Davis and LuoZiabrev et al., fig. 5.25.

2006 Tricolocapsa sp. S; Reference Auer, Gawlick and SuzukiAuer et al., fig. 6.45.

?2008 Tricolocapsa sp. S; Reference Auer, Gawlick, Suzuki and SchlagintweiAuer et al., fig. 9.79.

2008 Williriedellum sp. cf. W. sp. S Reference Baumgartner, Flores, Bandini, Girault and CruzBaumgartner et al., pl. 1, fig. 4.

2009 Tricolocapsa sp. S; Reference Kokubo and MatsuokaKokubo and Matsuoka, figs. 4.4−4.6.

2009non Tricolocapsa sp. S; Reference NishiharaNishihara, pl. 11, fig. 270.

?2009 Tricolocapsa aff. ruesti Tan; Reference NishiharaNishihara, pl. 11, fig. 268.

2009 Tricolocapsa sp. S; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 183, figs. 5.47A–B.

Holotype

Specimen MA7647 from sample MKS7A (illustrated in Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, O’Dogherty, Goričan, Dumitrica-Jud, Dumitrica, Pillevuit, Urquhart, Matsuoka, Danelian, Bartolini, Carter, De Wever, Kito, Marcucci and Steiger1995b pl. 4057, fig. 3) from Kashibara section (MA9), south of Hichiso town, Japan (see Matsuoka, Reference Matsuoka1995).

Diagnosis

Large cryptothoracic tricyrtid with very well defined lumbar stricture and a large abdomen. Outer surface without nodes and covered by hexagonal pore frames. Distal aperture constricted circular without rim.

Occurrence

Upper Bajocian to lower Bathonian.

Description

Cryptothoracic subspherical form composed of three distinct segments. Cephalis and thorax partially incased in the abdomen, with a very well defined lumbar stricture. The thorax is truncate-conical and covered by small pores whereas the abdomen is quite large and spherical. The entire surface of the abdomen is covered by a latticed meshwork of polygonal pore frames and a constricted aperture is visible.

Etymology

The name Nonaginta means ninety, in honor of the prodigious decade in contemporary history of radiolarian research.

Measurements

(in micrometers; µm) maximum width of shell 112−142, mean 118; maximum length 113−133, mean 123, based on four specimens.

Remarks

Hemicryptocapsa nonaginta n. sp. was published in open nomenclature in the Mesozoic radiolarian atlas (Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, O’Dogherty, Goričan, Dumitrica-Jud, Dumitrica, Pillevuit, Urquhart, Matsuoka, Danelian, Bartolini, Carter, De Wever, Kito, Marcucci and Steiger1995b) and since then it has been illustrated in many publications. This species differs from H. yaoi by having larger circular pores in the middle of polygonal areas. It differs from H. carpathica by having a simple circular aperture without a rim.

Hemicryptocapsa yaoi (Kozur, Reference Kozur1984)

1984 Praezhamoidellum yaoi Reference KozurKozur, p. 53, pl. 3, fig. 3a−b.

2003 Williriedellum dierschei Suzuki and Gawlick; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 201, fig. 6.73. [premature name]

2004 Williriedellum dierschei Reference Gawlick and SuzukiSuzuki and Gawlick in Reference Gawlick, Schlanginweit, Ebli and SuzukiGawlick et al., p. 311, pl. 4, figs. 1–6.

2006 Williriedellum dierschei; Reference Auer, Gawlick and SuzukiAuer et al., fig. 6.52.

2006 Williriedellum yaoi; Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and MassonO’Dogherty et al., p. 446, fig. 9, figures 6−12. [See for complete synonymy]

2007b Williriedellum dierschei; Reference Gawlick, Schlagintweit and SuzukiGawlick et al., fig. 8.45, 17.32.

2009 Williriedellum dierschei; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 179, figs. 5.27A–B, 5.28, 6.48A–B.

2010 Williriedellum yaoi; Reference Robin, Goričan, Guillocheau, Razin, Dromart and MosaffaRobin et al., pl. 3, figs. 18, 20.

2012 Hemicryptocapsa yaoi; Reference Goričan, Pavšič and RožičGoričan et al., pl. 1, fig. 25; pl. 2, fig. 12.

Genus Williriedellum Dumitrica, Reference Dumitrica1970

Type species

Williriedellum crystallinum Dumitrica, Reference Dumitrica1970.

Included species

CryptamphoreIla crepida O’Dogherty, Reference O’Dogherty1994; Hemicryptocapsa polyhedra Dumitrica, Reference Dumitrica1970; Hemicryptocapsa prepolyhedra Dumitrica, Reference Dumitrica1970; Hemicryptocapsa tuberosa Dumitrica, Reference Dumitrica1970; Sethocapsa yahazuensis Aita, Reference Aita1987; Tricolocapsa clivosa Aliev, Reference Aliev1967; Tricolocapsa formosa Chiari, Marcucci, and Prela, Reference Chiari, Marcucci and Prela2002; Williriedellum? gilkeyi Dumitrica, Reference Dumitrica1970; Williriedellum crystallinum Dumitrica, Reference Dumitrica1970; Williriedellum nodosum Chiari, Marcucci, and Prela, Reference Chiari, Marcucci and Prela2002; Williriedellum peterschmittae Schaaf, Reference Schaaf1981; Williriedellum sujkowskii Widz and De Wever, Reference Widz and De Wever1993.

Emended diagnosis

The genus Williriedellum originally contained cryptothoracic tricyrtids with an aperture regardless of the external ornamentation of the shell. We restrict the name Williriedellum to species with raised ridges or nodes on the outer surface of the abdomen. Species with a regular distribution of circular pores (each pore may be bounded by a simple polygonal pore frame) are assigned to Hemicryptocapsa. The same differentiation between these two genera was applied by O’Dogherty et al. (Reference O’Dogherty, Carter, Dumitrica, Goričan, De Wever, Bandini, Baumgartner and Matsuoka2009). The concept of that publication, however, did not allow for written definitions and comments.

Occurrence

Upper Aalenian to lower Coniacian.

Williriedellum crystallinum Dumitrica, Reference Dumitrica1970

1970 Williriedellum crystallinum Reference DumitricaDumitrica, p. 69, pl. 10, figs. 60 a–c, 62–63.

2009 Williriedellum crystallinum; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 178, fig. 5.24. [See for complete synonymy]

Williriedellum sp. cf. W. formosum (Chiari, Marcucci, and Prela, Reference Chiari, Marcucci and Prela2002)

2002 Tricolocapsa formosa Reference Chiari, Marcucci and PrelaChiari, Marcucci, and Prela, p. 83, pl. 5, figs. 3−8.

2011 Williriedellum formosum; Reference Bandini, Baumgartner, Flores, Dumitrica, Hochard, Stampfli and JackettBandini et al., pl. 5, figs. 27–28.

2012 Williriedellum formosum; Reference Goričan, Pavšič and RožičGoričan et al., pl. 1, fig. 23.

Remarks

The external ornamentation of this species is very close to W. formosum but has a rounded aperture whereas in the type material the aperture is covered by a dish-like appendage. Moreover, some of our specimens also have groups of four small pores per frame area like occurring in W. gilkeyi.

Williriedellum yahazuense (Aita, Reference Aita1987)

1987 Sethocapsa yahazuense Reference AitaAita, p. 73, pl. 2, figs. 8a−9b; pl. 9, figs. 16−17.

1993 Williriedellum sujkowskii Reference Widz and De WeverWidz and De Wever, p. 88, pl. 1, figs. 7−10.

2005 Williriedellum yahazuense; Reference Šmuc and GoričanŠmuc and Goričan, p. 62, pl. 3, fig. 19.

Williriedellum sp. A

Remarks

These specimens show very small and pointed nodes on the outer surface of the abdomen.

Williriedellum sp. B

Remarks

This morphotype has very faintly developed ridges on the surface. These ridges do not build well-defined frame areas characteristic of W. crystallinum.

Williriedellum? sp. C

Remarks

The genus is queried because the presence of the aperture is not confirmed. The ridges on the surface of the illustrated specimens are only very faintly developed compared to other species of this genus.

Genus Zhamoidellum Dumitrica, Reference Dumitrica1970

1992 Complexapora Reference KiesslingKiessling in Kiessling and Zeiss.

Type species

Zhamoidellum ventricosum Dumitrica, Reference Dumitrica1970.

Included species

Complexapora kozuri Hull, Reference Hull1997; Complexapora tirolica Kiessling in Kiessling and Zeiss Reference Kiessling and Zeiss1992; Zhamoidellum argandi O’Dogherty, Goričan, and Dumitrica in O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Goričan and Dumitrica2006; Zhamoidellum boehmi Kiessling, Reference Kiessling1999; Zhamoidellum calamin O’Dogherty, Goričan, and Dumitrica in O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Goričan and Dumitrica2006; Zhamoidellum mikamense Aita, Reference Aita1986; Zhamoidellum ovum Dumitrica, Reference Dumitrica1970; Zhamoidellum ventricosum Dumitrica, Reference Dumitrica1970; Zhamoidellum yehae Dumitrica in Goričan et al., Reference Goričan, Carter, Dumitrica, Whalen, Hori, De Wever, O’Dogherty, Matsuoka and Guex2006.

Remarks

As stated by O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and Masson2006, the presence or absence of a sutural pore in Zhamoidellum can be regarded as character related to the intraspecific variability. Only species without tubercles are included. Species with spines and nodes are placed in Arcanicapsa.

Occurrence

Lower Pliensbachian? to upper Tithonian.

Zhamoidellum ovum Dumitrica, Reference Dumitrica1970

1970 Zhamoidellum ovum Reference DumitricaDumitrica, p. 79 pl. 9, figs. 52a–b, 53–54.

2009 Zhamoidellum ovum; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 179, fig. 5.30A–B, 6.33A–B. [See for complete synonymy]

Zhamoidellum sp. aff. Z. ovum Dumitrica, Reference Dumitrica1970

Remarks

These specimens are considered only affinis because they display less-pronounced constrictions and more elongated outline of the shell.

Zhamoidellum ventricosum Dumitrica, Reference Dumitrica1970

1970 Zhamoidellum ventricosum Reference DumitricaDumitrica, p. 79, pl. 9, figs. 55a–b.

2003 Zhamoidellum ventricosum; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 205, fig. 6.96.

2006 Zhamoidellum ventricosum; Reference Auer, Gawlick and SuzukiAuer et al., fig. 6.57.

2006 Zhamoidellum ventricosum; Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and MassonO’Dogherty et al., p. 445, pl. 9, figs. 13–25. [See for complete synonymy]

2009 Zhamoidellum ventricosum; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 179, fig. 5.29.

Zhamoidellum sp. A

Remarks

This morphotype differs from other Zhamoidellum by its smaller size. The cephalis and thorax are imperforate, but the abdomen is covered by small circular pores set in polygonal pore frames. The collar and lumbar strictures are well marked on these specimens.

Zhamoidellum sp. B

Remarks

This morphotype differs from Z. ovum by having a more deeply encased thorax. In addition, the collar stricture is very distinct and the thorax is not porous. The illustrated specimens display enough characters to be considered a new species. However, pictures showing the basal aperture are not available and for this reason this morphotype is not described as a new taxon in this paper.

Zhamoidellum sp. C

Remarks

These specimens are very close to Zhamoidellum sp. B, but they differ by having a porous thorax and a less-marked collar stricture. The pores are more widely open and the surrounding ridges are thinner than in Zhamoidellum sp. B.

Family Japonocapsidae Kozur, Reference Kozur1984

Genus Striatojaponocapsa Kozur, Reference Kozur1984

Type species

Tricolocapsa plicarum Yao, Reference Yao1979.

Occurrence

Lower Bajocian to upper Callovian.

Striatojaponocapsa conexa (Matsuoka, Reference Matsuoka1983)

1983 Tricolocapsa conexa Reference MatsuokaMatsuoka, p. 20, pl. 3, figs. 3–7; pl. 7, figs. 11–14.

2003 Tricolocapsa conexa; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 208, figs. 5.42, 6.43–45.

2006 Striatojaponocapsa conexa; Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and MassonO’Dogherty et al., p. 447, pl. 10, figs. 18–20. [See for complete synonymy]

2007 Striatojaponocapsa conexa; Reference Hatakeda, Suzuki and MatsuokaHatakeda et al., pl. 2, figs. 1–10.

2007 Striatojaponocapsa conexa; Suzuki and Gawlick, p. 182, figs. 5.40, 6.32A–B.

Striatojaponocapsa riri O’Dogherty, Goričan, and Dumitrica in O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Goričan and Dumitrica2006

2006 Striatojaponocapsa riri Reference O’Dogherty, Goričan and DumitricaO’Dogherty, Goričan, and Dumitrica in Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and MassonO’Dogherty et al., p. 447, pl. 8, figs. 14–15.

2007 Striatojaponocapsa riri; Reference Hatakeda, Suzuki and MatsuokaHatakeda et al., pl. 2, figs. 11–20.

Striatojaponocapsa synconexa O’Dogherty, Goričan, and Dumitrica in O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Goričan and Dumitrica2006

2006 Striatojaponocapsa synconexa Reference O’Dogherty, Goričan and DumitricaO’Dogherty, Goričan, and Dumitrica in Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and MassonO’Dogherty et al., p. 447, pl. 10, figs. 9–17. [See for complete synonymy]

2007 Striatojaponocapsa synconexa; Reference Hatakeda, Suzuki and MatsuokaHatakeda et al., pl. 1, figs. 11–20.

2008 Striatojaponocapsa synconexa; Reference Baumgartner, Flores, Bandini, Girault and CruzBaumgartner et al., pl. 4, fig. 18.

2012 Striatojaponocapsa synconexa; Reference Goričan, Pavšič and RožičGoričan et al., pl. 1, figs. 15, 35.

2013 Striatojaponocapsa synconexa; Reference Chiari, Baumgartner, Bernoulli, Bortolotti, Marcucci, Photiades and PrincipiChiari et al., p. 416, fig. 14c.

Striatojaponocapsa spp.

Remarks

Various elongated forms of Striatojaponcapsa have been found in our samples. The small number of specimens does not allow the description of new species. They differ from other Striatojaponocapsa by the elongated outline and small size.

Striatojaponocapsa? spp.

Remarks

The genus is queried because the distal part and the classical appendage on these forms are not preserved, but the surface ornamentation fits well with the general pore patterns of Striatojaponocapsa.

Genus Japonocapsa Kozur, Reference Kozur1984

Type species

Tricolocapsa? fusiformis Yao, Reference Yao1979.

Remarks

This form is close to Japonocapsa fusiformis (Yao, Reference Yao1979), but the basal dish-like appendage seems broken off in this specimen.

Family Unumidae Kozur, Reference Kozur1984

Included genera.—

Guttacapsa O’Dogherty, Reference O’Dogherty1994; Helvetocapsa O’Dogherty, Goričan, and Dumitrica in O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Goričan and Dumitrica2006; Protunuma Ichikawa and Yao, Reference Ichikawa and Yao1976; Quarticella Takemura, Reference Takemura1986; Spinunuma Ichikawa and Yao, Reference Ichikawa and Yao1976 (syn. Unuma); Turbocapsula O’Dogherty, Reference O’Dogherty1994; Unuma Ichikawa and Yao, Reference Ichikawa and Yao1976; and Yamatoum Takemura, Reference Takemura1986.

Remarks.—

According to De Wever et al., Reference De Wever, Dumitrica, Caulet and Caridroit2001 (p. 265) and O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, De Wever, Goričan, Carter and Dumitrica2011 (p. 112) this family was placed under the superfamily Archaeodictyomitroidea. However, the family Unumidae as stated by Takemura, Reference Takemura1986 (p. 36) does not share the same cephalic structure. In this paper, we prefer to consider this family as more closely related to the Japonocapsidae. We also tentatively reassign the genera Quarticella and Yamatoum under this family because the cephalic structure (Yamatoum-type) is the same as in Unuma. Genus Protunuma Ichikawa and Yao, Reference Ichikawa and Yao1976

Type species

Protunuma fusiformis Ichikawa and Yao, Reference Ichikawa and Yao1976

Occurrence

Middle Toarcian to upper Tithonian.

Protunuma europeus O’Dogherty, Goričan, and Dumitrica in O’Dogherty et al., Reference O’Dogherty, Goričan and Dumitrica2006

2006 Protunuma europeus Reference O’Dogherty, Goričan and DumitricaO’Dogherty, Goričan, and Dumitrica in Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and MassonO’Dogherty et al., p. 433, pl. 10, figs. 6–8.

Protunuma japonicus Matsuoka and Yao, Reference Matsuoka and Yao1985

1985 Protunuma japonicus Reference Matsuoka and YaoMatsuoka and Yao, p. 130, pl. 1, figs. 11–15; pl. 3, figs. 6–9.

1995b Protunuma japonicus; Reference Baumgartner, O’Dogherty, Goričan, Dumitrica-Jud, Dumitrica, Pillevuit, Urquhart, Matsuoka, Danelian, Bartolini, Carter, De Wever, Kito, Marcucci and SteigerBaumgartner et al., p. 434, pl. 3292, fig. 1–8.

2003 Protunuma multicostatus (Heitzer); Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 197, fig. 5.43. [See for complete synonymy]

Protunuma ochiensis Matsuoka, Reference Matsuoka1983

1983 Protunuma (?) ochiensis Reference MatsuokaMatsuoka p. 26, pl. 4, figs. 8–11; pl. 9, figs. 3–7.

2003 Protunuma ochiensis; Reference Suzuki and GawlickSuzuki and Gawlick, p. 197, fig. 6.90.

2006 Protunuma ochiensis; Reference O’Dogherty, Bill, Goričan, Dumitrica and MassonO’Dogherty et al., p. 433, pl. 7, figs. 11–13. [See for complete synonymy]

Protunuma turbo Matsuoka, Reference Matsuoka1983

1983 Protunuma turbo Reference MatsuokaMatsuoka, p. 24, pl. 4, figs. 4–7; pl. 8, figs. 16–18; pl. 9, figs. 1–2.

1995b Protunuma turbo; Reference Baumgartner, O’Dogherty, Goričan, Dumitrica-Jud, Dumitrica, Pillevuit, Urquhart, Matsuoka, Danelian, Bartolini, Carter, De Wever, Kito, Marcucci and SteigerBaumgartner et al., p. 436, pl. 4034, figs. 1–3. [See for complete synonymy]