Why do some groups of individuals mobilize to advocate for what they understand to be their interests? Given that public engagement in politics is a critical driver of social evolution, scholars have developed a variety of explanations for when, how, and why certain individuals choose to become politically active. Rationalist explanations emphasize how circumstances or actors can alter incentives for action, leading individuals to overcome the desire to free ride on the efforts of others (Olson Reference Olson1971; Nownes Reference Nownes2013). Social constructivists have demonstrated how institutions and norms inform group identities, shaping what individuals perceive to be in their interests and spurring them to ensure that those interests are protected or realized (Chandra Reference Chandra2001; Paul Reference Paul2000). In turn, scholars of human behavior and psychology have identified the existence of different personality types that influence the underlying willingness of individuals to collaborate in the pursuit of common goals (Ostrom Reference Ostrom2000).

We posit that existing explanations do not provide an exhaustive understanding of the processes that shape the likelihood that individuals become politically engaged. In particular, we argue that prior scholarship has not accounted for the international dimensions of domestic mobilization. In this vein, we examine the mobilization of diaspora communities in their countries of residence, focusing on the United States. Using newly collected data on all diasporas present in the United States and their association with formal foreign policy interest groups, we find that, of communities from 110 countries, only 38, or 34.55%, have mobilized to influence U.S. foreign policy.

Given that certain prominent interest groups, such as those representing the Israeli-American and Cuban-American communities, are widely understood as having successfully shaped U.S. foreign policy—as well as the fact that the United States wields enormous global influence as the world’s only superpower—this relatively limited mobilization of diasporas is highly puzzling. In turn, we identify two conditions that spur diaspora mobilization: democratic experience and conflict in the country of origin. Experience with democratic governance fosters knowledge of the ability for citizens to shape political outcomes and enables action. Violent conflict motivates individuals to get engaged to raise awareness about the issue. Given these conditions, we argue that political entrepreneurs with the necessary knowledge, networks, and resources drive top-down mobilization.

Specifically, we study diaspora mobilization in the United States that aims to influence American foreign policy. In the United States, interest groups are a regular feature of the democratic process wherein citizens with similar preferences come together to petition the government to act in ways that are beneficial to their group (Gilens and Page Reference Gilens and Page2014). Diasporas in the United States have also made use of lobbying to further the interests of their communities. Past studies have shown that these efforts have often been effective in shaping U.S. priorities and aid flows (Bermeo and Leblang Reference Bermeo and Leblang2015; Paul and Paul Reference Paul and Paul2009). For instance, the Armenian-American lobby influenced the U.S. Congress’s perspective on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia in the 1990’s (Ambrosio Reference Ambrosio2002a), while the Greek-American lobby successfully persuaded Congress to impose an arms embargo on Turkey after Turkey’s invasion of Cyprus in 1974 (Kitroeff Reference Kitroeff and Tziovas2009). Moreover, the fact that India went from being a nuclear pariah slapped with sanctions after its 1998 nuclear tests to signing a civil nuclear agreement with the United States within ten years can be partly explained by the successful lobbying of the U.S.-India Political Action Committee (USINPAC).

However, while some diasporas in the United States have attempted to influence U.S. foreign policy, not all have followed suit. We examine why certain diasporas form interest groups and others do not, a pattern that is inherently puzzling given the United States’ global power and its ability to shape international affairs. As a result of America’s predominance worldwide, every diaspora has an incentive to attempt to influence U.S. foreign policy—succeeding could bring substantial benefits to a community and its country of origin. Even in cases where the United States recognizes few direct interests of its own, a diaspora could draw greater attention to its country of origin, which could ultimately result in greater economic aid, investment, or military resources directed to that country in a manner that benefits the community or their kin abroad. Although certain countries may seem insignificant to the United States, the United States is significant to every country in the world. Moreover, it is surprising that diaspora organizations such as the American Israeli Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) and the Cuban American National Foundation (CANF), which are widely recognized as having successfully influenced U.S. foreign policy, have not inspired widespread mobilization of other diaspora communities.

Since the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, the United States has been experiencing a historic third wave of mass immigration that continues to this day. In the fifty years from 1965–2015, nearly fifty-nine million immigrants settled in the United States, swelling the country’s foreign-born population from 4.8% to 13.9% (Passel and Rohal Reference Passel and Rohal2015). Unlike previous migratory waves where almost all voluntary migrants were of European origin, since 1965 individuals from all over the world have come to America (Grieco et al. Reference Grieco, Acosta, de la Cruz, Gambino, Gryn, Larsen, Trevelyan and Walters2012).

This dramatic global migration to the United States has raised numerous questions regarding how recent immigrant communities are both integrating into as well as transforming U.S. society. Since the end of the Cold War, there has been an extensive debate over the influence that diasporic interest groups exert over U.S. foreign policy.Footnote 1 When the United States had to reevaluate its foreign policy objectives in the 1990s, some argued that its government had fallen prey to diasporic interest groups seeking to shape American priorities (Huntington Reference Huntington1997; Smith Reference Smith2000). These concerns arose from a longstanding view that American foreign policy is beholden to “the primal facts of ethnicity” (Glazer and Moynihan Reference Glazer and Moynihan1975, 23) and have inspired numerous analyses showing that diasporas have, under certain conditions, indeed influenced U.S. foreign policy on a diverse set of issues (Paul and Paul Reference Paul and Paul2009).

We take a step back from existing studies on the effectiveness of diasporic lobbies and ask why some diasporas in the United States form interest groups with the aim of influencing U.S. foreign policy while others do not. Although there has been substantial examination of interest group efficacy, little has been written on why some diasporas mobilize while others eschew any such effort. This selective focus is a concern since exclusive examination of diasporas that effectively influence U.S. foreign policy can exaggerate the extent to which diasporas are mobilizing to this end.

We argue that two factors significantly increase the likelihood of diaspora mobilization: a community’s experience with democratic governance and violent conflict in its country of origin. Experience with democratic governance, and the accompanying knowledge of the civic power it provides, enables mobilization. Conflict motivates communities to draw America’s attention toward the issues of concern. Given these conditions, we further argue that the mobilization of diasporas is the result of a top-down process, as opposed to a bottom-up grassroots movement. Political entrepreneurs—individuals with the knowledge, networks, and resources to navigate the challenges associated with establishing a formal interest group organization and engaging in political activities—catalyze mobilization.

To test our hypotheses, we employ a multi-method research design. First, having collected new data regarding all formal diasporic interest groups active in the domain of foreign policy, we quantitatively estimate the relationship between different characteristics of diasporas and their countries of origin with the existence of those organizations. Second, we conduct the first in-depth case studies of the historical and contemporary Indian-American lobby to assess the mechanisms behind mobilization. With respect to the India League of America (ILA), active in the mid-twentieth century, we analyze primary archival sources from the Library of Congress (Washington, D.C.), the British Library (London), and the National Archives of India (New Delhi). We also interviewed the founding members of the current U.S.-India Political Action Committee (USINPAC). By examining what motivated the leaders of the ILA and USINPAC to engage in foreign policy lobbying, we establish how experience with democratic governance and conflict in origin countries lead political entrepreneurs to mobilize and establish interest groups.

Diasporic Interest Groups

Diasporic lobbies are a specific type of interest group in U.S. politics that try to influence policy-making (King and Melvin Reference King and Melvin2000). In general, diasporas comprise “a people with a common origin who reside, more or less on a permanent basis, outside the borders of their ethno-religious homeland” (Shain Reference Shain2007, 130). More specifically, diasporic interest groups are “institutionalized, nongovernmental actors whose members share a collective cultural identity, to which belonging to the same immigrant community is central” (Rytz Reference Rytz2013, 15). An organized diasporic interest group may draw on the support of its broader affiliated community, but not all members of a diaspora are necessarily members of a formal lobby organization, or even tacit supporters. Diasporic interest groups represent their constituents and raise awareness about political issues throughout the associated community (Wilcox and Berry Reference Wilcox and Berry2009). We focus on the activities of those groups that aim to influence U.S. foreign policy regarding their respective countries of origin or issues that affect those countries.

Past research regarding diasporic interest groups has typically comprised case studies of prominent organizations and the influence that they wield on U.S. foreign policy (Ambrosio Reference Ambrosio2002b; Rubenzer Reference Rubenzer2008; Smith Reference Smith, DeWind and Segura2014). Historic trends in immigration and diaspora engagement with U.S. foreign policy in different periods have been compared (Connolly Reference Connolly and Ueda2006; DeConde Reference DeConde1992). Most prominently, scholars have sought to assess whether or under what conditions diasporic interest groups are actually effective at influencing foreign policy (Haney and Vanderbush Reference Haney and Vanderbush1999; McCormick Reference McCormick, Wittkopf and McCormick2012; Milner and Tingley Reference Milner and Tingley2015; Moore Reference Moore2002; Paul and Paul Reference Paul and Paul2009; Rubenzer and Redd Reference Rubenzer and Redd2010). They have also explored the normative implications of their influence for U.S. society and the pursuit of its interests abroad (Huntington Reference Huntington1997; Mearsheimer and Walt Reference Mearsheimer and Walt2007; Smith Reference Smith2000; Yin and Koehn Reference Yin, Koehn and Ueda2006), taking into consideration potential effects that such influence may have on homeland societies (Shain Reference Shain1994, Reference Shain1999; Shain and Barth Reference Shain and Barth2003). While these research agendas provide numerous insights—most notably that diasporas have successfully shaped U.S. foreign policy in numerous instances—they have not examined in detail how individuals of a particular diaspora overcome the collective action problem to form an interest group (Haney Reference Haney, Hook and Jones2012). As the number of diasporic interest groups and their political skills increase (Thurber, Campbell, and Dulio Reference Thurber, Campbell and Dulio2018), the question of diaspora mobilization merits greater attention.

Interest Group Mobilization

Diasporas face the same mobilization challenges as other groups. A significant body of scholarly work has been devoted to determining when and how group mobilization occurs. Truman’s (Reference Truman1951) “disturbance theory” asserts that interest groups form if social or economic crises “disturb” latent interests, motivating affected groups to become politically engaged. Koinova (Reference Koinova2013) argues that diasporas that are created due to displacement from conflict in their homelands can mobilize and pursue “radical” or “moderate” objectives depending on the level of violence experienced. Additionally, she finds that the strength of these movements is tied to the extent of a diaspora’s linkages with elites in the country of origin. However, disturbances do not always lead to mobilization due to the collective action problem. Individuals realize that if others form a group, one can benefit from its activities without incurring costs, creating an incentive to free-ride (Olson Reference Olson1971). When it comes to interest group formation, the same concerns regarding free-riding exist (Lowery and Gray Reference Lowery and Gray2004).

Much scholarship has focused on the ways that groups overcome the collective action problem and spur mobilization.Footnote 2 Scholars have identified three types of “selective benefits” that organizations can provide to individuals as inducements for involvement: material, solidarity, and expressive benefits (Clark and Wilson Reference Clark and Wilson1961; Nownes Reference Nownes2013). As Nownes (Reference Nownes2013, 45) explains, “material benefits are benefits that have tangible economic value,” solidarity benefits are social rewards like meetings, outings, and group gatherings, while expressive benefits are intangible gains derived from working for a cause. Organizations that can provide these benefits have a greater chance at overcoming the free-rider problem.

An important consideration tied to mobilization is the initial capital needed to establish an interest group, as well as to provide material and other benefits to group members. Thus, many groups form and are sustained because of the support of patrons. Patrons are typically individuals, although they can also be foundations, firms, or even government agencies (Nownes and Neeley Reference Nownes and Neeley1996). Citizen and non-profit groups which do not have an occupational prerequisite for membership particularly benefit from patronage (Walker Reference Walker1983). Patrons have a tendency to support issues that are politically salient at a given point in time, which has significant implications for groups that rely on them (Jenkins and Eckert Reference Jenkins and Eckert1986; Jenkins and Perrow Reference Jenkins and Perrow1977; McCarthy and Zald Reference McCarthy and Zald1977).

Patronage alone, however, does not necessarily guarantee group formation. “Entrepreneurs” are often critical for overcoming the collective action problem and utilizing the resources at their disposal to organize groups (Kingdon and Thurber Reference Kingdon1984; Nownes and Neeley Reference Nownes and Neeley1996). While crises can mobilize people, effective leadership is required to attract members and sustain organized action (Salisbury Reference Salisbury1969). One example of this type of charismatic entrepreneurial leadership tied to diaspora communities is CANF’s founding member, Jorge Mas Canosa. CANF refers to him as “a Cuban symbol of liberty…who represented the successes and hopes of generations of Cubans who had left the island” (Cuban American National Foundation 2021). He has also been characterized as “an exceptional figure in his ability to organize, lead, fundraise and lobby” (Haney and Vanderbush Reference Haney and Vanderbush1999 in Rytz Reference Rytz2013, 60). “The importance of leadership cannot be overstated,” (Nownes and Neeley Reference Nownes and Neeley1996, 138) since it plays an important role in the initial phases of group development (Berry Reference Berry1978; Hrebenar and Scott Reference Hrebenar and Scott2015).

Democracy, Conflict, Entrepreneurship, and Diaspora Mobilization

Although past studies have generated numerous key insights, we posit that none can holistically explain why only certain diasporas mobilize politically. In turn, we develop a unique theoretical framework regarding diaspora mobilization based on the characteristics of countries of origin. First, we argue that there are two key conditions which make diaspora mobilization for foreign policy lobbying more likely: democratic experience and violent conflict. Experience with democratic governance provides community elites with knowledge regarding how to engage in politics as well as a recognition that such engagement may shape policy outcomes, while conflict is a factor that motivates individuals to become politically active. Second, we emphasize the role of political entrepreneurs as a mechanism leading to the top-down mobilization of diaspora communities for foreign policy lobbying. In short, democratic experience and conflict in origin countries are correlated with diaspora mobilization in the United States because they make it more likely that political entrepreneurs will engage their communities as opposed to instigating bottom-up grassroots activism.

Democratic Experience and Violent Conflict

First, we argue that a diaspora’s past experiences with mobilization for collective action in their respective countries of origin will influence the likelihood of their mobilization in the United States. In particular, societies where elites are familiar with civic engagement and its ability to shape political outcomes will be more likely to form interest groups in the American context. Some scholars have already claimed that “the cultural baggage immigrant groups carry with them have a potential impact on their identities and experiences in the U.S.” (Connolly Reference Connolly and Ueda2006, 59; Ramakrishnan and Espenshade Reference Ramakrishnan and Espenshade2001). For example, Aleksynska (Reference Aleksynska2011) finds that immigrant civic engagement in their states of residence is associated in part with the vibrancy of civil societies in their respective countries of origin.Footnote 3 It is thus plausible that experiences with some form of democratic governance will be associated with diaspora mobilization. Importantly, given that we argue that entrepreneurs are the drivers of mobilization, democratic governance in countries of origin need not be entrenched, but at a minimum familiarize elites with the democratic process and the power to engage in politics as independent citizens.Footnote 4

In contrast, one might argue that individuals who come to the United States fleeing autocratic persecution might have a greater incentive to mobilize and petition the U.S. government to sanction repressive regimes governing their countries of origin. However, while this may apply to a few cases, all else equal, we argue that socialized democratic experience has a greater impact than the desire to punish autocratic governments. Desire to mobilize does not necessarily translate into the ability to mobilize. Democratic experience in the country of origin affects the capacity of a particular community to be politically active and makes mobilization more likely. Our first hypothesis is thus:

H1: The more democratic a diaspora’s country of origin, the more likely that the community is associated with a formal foreign policy interest group.

Second, we build upon the classic “disturbance theory” and argue that one reason diasporas may organize interest groups could be a pressing need to raise awareness of and support for or against certain actions regarding a conflict in their country of origin. It is recognized that socio-political disturbances can instigate mobilization in certain cases and even lead individuals to attempt to achieve transitional justice for conflict-affected societies (Koinova Reference Koinova2018; Nownes Reference Nownes2013; Orjuela Reference Orjuela2018). We assert that conflict involving a country of origin therefore engenders the formation of interest groups in the United States. Conflict is the most visceral form of crisis and the one most likely to lead to the mobilization of diaspora communities. As a superpower since the end of World War II, the United States has had a disproportionate influence over international politics. If diasporas in the United States manage to successfully mobilize and appeal to U.S. policymakers on critical security issues relating to their country of origin, they stand the best chance of having an impact.Footnote 5

As an illustration, the CANF claims that it was established because its founders “refused to accept the idea of the permanent loss of freedom and democracy for their native island” following the victory of Fidel Castro’s revolutionary forces (Cuban American National Foundation 2015). Thus, the Cuban lobby in the United States has been united by a strong political commitment based on the situation in Cuba. The crisis of Cuba’s communist revolution triggered diaspora mobilization that continues to this day. Our second hypothesis is thus:

H2: Conflict in a diaspora’s country of origin makes it more likely that the community is associated with a formal foreign policy interest group.

Political Entrepreneurs

Ultimately, we argue that these structural conditions instigate top-down elite mobilization as opposed to bottom-up grassroots mobilization, leading to the establishment of interest groups.Footnote 6 Political entrepreneurs drive diaspora mobilization because they have the knowledge, resources, and personal networks to navigate the challenges associated with forming interest groups and engaging in lobbying activities. The unique situation of immigrant groups in the United States makes entrepreneurship particularly important. Being populated by relatively recent arrivals, diaspora communities are unlike native-born populations in that they are less likely to be familiar with the U.S. political system or comfortable engaging in politics. Furthermore, diasporas will typically be smaller than sub-groups of the native-born population; any salient sub-set of the U.S. population will be larger than most diaspora communities, which on average constituted only 350,000 people in 2010.

Interest group formation requires specialized knowledge and resources. Immigrant transnational entrepreneurs play an important role in deepening linkages between their countries of residence and origin (Kloosterman and Rath Reference Kloosterman and Rath2001; Zapata-Barrero and Rezaei Reference Zapata-Barrero and Rezaei2020), so are well equipped to understand foreign policy challenges. This is particularly the case in the U.S. context, where an actor needs substantial political and financial resources in order to successfully obtain access to policymakers. Moreover, foreign policy is a niche domain that leads to mass mobilization, even among the broader native-born public, only in specific circumstances. As a result, diaspora mobilization is contingent upon individuals who have the capacity, knowledge, and motivation to establish an interest group. We thus argue that the existence of diasporic interest groups is likely the result of a top-down process driven by political entrepreneurs.

Research Design

In order to test our theoretical framework and hypotheses, we deploy a multi-method research design since “qualitative and quantitative methods offer complementary but distinctive forms of analysis that combine to offer a more comprehensive, multidimensional” account of a theory (Ahram Reference Ahram2013, 281). We quantitatively assess whether democratic experience and conflict in countries of origin are systematically correlated with the existence of diasporic foreign policy interest groups. To do so, we identified all currently active diasporic interest groups and collected data on relevant characteristics of diaspora communities. However, we are unable to quantify political entrepreneurship for two reasons. First, we do not believe that any single diaspora community is inherently more entrepreneurial than any other. Thus, we cannot have a formal estimate of the likelihood of entrepreneurship for each diaspora we identify. Second, it is impossible for us to determine what happened to those communities which did not form an interest group. It is theoretically possible that entrepreneurs from some of those communities existed but failed to establish an organization. There is no way to identify all failed attempts at entrepreneurship with a high degree of certainty.Footnote 7 Thus, we leverage the strengths of a multi-method research design to overcome this challenge (Mahoney and Goertz Reference Mahoney and Goertz2006) by including case studies that provide us with the ability to assess invariant factors that could shape political phenomena (Gerring Reference Gerring2004, 349). We explain the role of political entrepreneurship in diaspora mobilization for foreign policy issues given experience with democratic governance and conflict in the country of origin using case studies with original qualitative data.

Specifically, we examine the historic and contemporary interest groups associated with the Indian-American community, the India League of America (ILA) and the U.S.-India Political Action Committee (USINPAC), respectively. Through our case studies we assess the relative importance of political entrepreneurs and the relationship between the variables that we identify as tied to diasporic interest group existence in our quantitative analyses. Our objective is to assess whether these interest groups were formed as a result of top-down or bottom-up processes, as well as whether democratic experience and conflicts in India instigated mobilization. Although we cannot demonstrate that political entrepreneurship is behind every single instance of diaspora mobilization in the United States, through qualitative analyses we can trace the mechanism behind Indian-American mobilization in both the historical and contemporary cases. While small-N case studies might not appear generalizable, “it is not true to say [they] cannot provide trustworthy information about the broader class” of cases they represent (Ruddin Reference Ruddin2006, 799). The findings of the Indian-American cases can offer a framework for future examination of mobilization by other diaspora communities. Ultimately, our qualitative data can allow us to describe the mechanism behind our quantitative results.

Quantitative Analysis

To systematically test our hypotheses, we develop cross-sectional logistic regression models to assess the likelihood a diaspora is associated with a foreign policy interest group. To construct our models, we draw on numerous sources and create an original dataset. This involved original data collection to identify all diaspora communities in the United States as well as all formal diaspora organizations engaged in foreign policy lobbying.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable (DV) for this study constitutes an indicator of whether diaspora communities are affiliated with an existing, formal diasporic interest group.Footnote 8 We define diasporic foreign policy interest groups as

formal organizations established by individuals who consider themselves to be part of a community of Americans with ties to a country of origin from which they or their relatives emigrated, whose primary purpose is to influence the foreign policy of the United States through engagement with the electoral process or the lobbying of American policymakers.

This definition has three primary components, focusing on organizations that 1) are associated with a diaspora community, 2) aim to influence U.S. foreign policy, and 3) engage in electoral activities or the lobbying of U.S. policymakers.

In practice, our definition leads us to focus on two types of groups: political action committees (PACs) and 501(c)4 nonprofit organizations. PACs are defined as organizations established “for the purpose of raising and spending money to elect and defeat candidates” (Center for Responsive Politics 2020). The objective of PACs is to influence the outcome of elections by lending financial support to specific candidates. We identify those PACs that are associated with diaspora communities and that seek to influence U.S. foreign policy through electoral politics, lending support to candidates with specific stances on relevant policy questions. In turn, an organization registered under 501(c)4 of the U.S. tax code is defined by the IRS (2020) as a “social welfare organization” which “may further its exempt purposes through lobbying as its primary activity without jeopardizing its exempt status.” Thus, 501(c)4 organizations retain their non-profit status while being able to engage in lobbying.Footnote 9

In order to establish our DV, we first identified the complete universe of potential diasporic interest groups in the United States using census data regarding the population of all foreign-born individuals by country of birth (U.S. Census Bureau 2017).Footnote 10 We then independently identified all existing diasporic interest groups involved with foreign policy lobbying in the United States. In sum, we identified sixty-three relevant organizations associated with thirty-eight diasporas.Footnote 11 We then created a dichotomous variable indicating whether a foreign-born community is associated with a foreign policy interest group, coded 1 if yes and 0 if no, which serves as the first DV in our models.Footnote 12

In order to assess the validity of our results, we construct a second DV using the list of communities affiliated with diasporic foreign policy lobbies identified by Paul and Paul (Reference Paul and Paul2009). This DV is likewise a dichotomous variable coded as 1 if a formal interest group organization associated with a diaspora community exists and 0 otherwise. Paul and Paul collected their data in 2004–2006 and their list of organizations differs slightly from the new data we collected in 2018–2020. Given the differences, it is important to test the robustness of our models using this alternative DV. In online appendix 1 we provide more details regarding Paul and Paul’s data on diasporic lobbies.

Figure 1 illustrates the results of our data collection and identifies all the foreign-born communities in the United States, as well as all those associated with foreign policy interest groups. In total, there are diasporic communities of over 20,000 people who hail from 110 countries from all over the world.Footnote 13 Of the 110 diasporas, we found that thirty-eight (34.55%) are associated with a lobby while seventy-two are not. In turn, twenty-nine (26.3%) are associated with foreign policy interest groups as identified by Paul and Paul, while the remaining eighty-one are not. Given these discrepancies, we develop models with DVs based on both our own data and Paul and Paul’s data.

Figure 1 Diasporas in the U.S. associated with formal interest groups

COUNTRY LISTS

Interest Group Identified (both): 25 Countries of Origin

Albania; Armenia; Colombia; Croatia; Cuba; Eritrea; Ethiopia; Greece; India; Iran; Ireland; Israel; Italy; Japan; Lebanon; Lithuania; Mexico; Pakistan; Philippines; Poland; South Korea; Taiwan; Turkey;* Ukraine; Vietnam

Interest Group Identified (new data only): 13 Countries of Origin

Azerbaijan;** Bosnia and Herzegovina; Cambodia; China; Cyprus;** Egypt; Libya;** North Macedonia; Morocco; South Sudan;** Sri Lanka; Syria; Yemen

Interest Group Identified (Paul and Paul data only): 4 Countries of Origin

Czechia; El Salvador; Serbia; Somalia

No Interest Group Identified (diaspora present): 72 Countries of Origin***

Afghanistan; Argentina; Australia; Austria; Bahamas; Bangladesh; Barbados; Belarus; Belgium; Belize; Bolivia; Brazil; Bulgaria; Cameroon; Canada; Cape Verde; Chile; Costa Rica; Denmark; Dominica; Dominican Republic; Ecuador; Fiji; France; Germany; Ghana; Grenada; Guatemala; Guyana; Haiti; Honduras; Hong Kong; Hungary; Indonesia; Iraq; Jamaica; Jordan; Kazakhstan; Kenya; Kuwait; Laos; Latvia; Liberia; Malaysia; Moldova; Myanmar; Nepal; Netherlands; Nicaragua; Nigeria; Norway; Panama; Peru; Portugal; Romania; Russia; Saudi Arabia; Sierra Leone; Singapore; South Africa; Spain; St. Vincent and the Grenadines; Sudan; Sweden; Switzerland; Thailand; Trinidad & Tobago; United Kingdom; Uruguay; Uzbekistan; Venezuela, West Indies*****

No Interest Group Identified (no diaspora present): 81 Countries of Origin*****

Algeria; Andorra; Angola; Antigua and Barbuda; Bahrain; Benin; Bhutan; Botswana; Brunei Darussalam; Burkina Faso; Burundi; Central African Republic; Chad; Comoros; Cote d’Ivoire; Democratic Republic of the Congo; Djibouti; Equatorial Guinea; Estonia; Eswatini; Finland; Gabon; Gambia; Georgia; Guinea; Guinea-Bissau; Iceland; Kyrgyzstan; Kiribati; Lesotho; Liechtenstein; Luxembourg; Madagascar; Malawi; Maldives; Mali; Malta; Marshall Islands; Mauritania; Mauritius; Micronesia; Monaco; Mongolia; Montenegro; Mozambique; Namibia; Nauru; New Zealand; Niger; North Korea; Oman; Palau; Papua New Guinea; Paraguay; Qatar; Republic of Congo; Rwanda; Samoa; San Marino; Sao Tomé and Principe; Senegal; Seychelles; Slovakia; Slovenia; Solomon Islands; St. Kitts and Nevis; St. Lucia; Suriname; Tajikistan; Tanzania; Timor-Leste; Togo; Tonga; Tunisia; Turkmenistan; Tuvalu; Uganda; United Arab Emirates; Vanuatu; Zambia; Zimbabwe

Notes: *The United States Census Bureau only presents data by nationality for independent states recognized by the United States government. Sub-national communities, such as the Kurdish diaspora from Turkey, are therefore not taken into consideration.

**These countries of origin have diaspora populations under 20,000 individuals and are therefore not included in the statistical analyses.

***Only countries of origin associated with a diaspora of over 20,000 individuals identified by the United States Census Bureau are listed. Territories not recognized as independent states by the United States are not listed.

****The United States Census Bureau exceptionally provides data for West Indies, which is not an official country but is included in the analyses.

*****These countries of origin do not have a community of over 20,000 individuals identified by the United States Census Bureau. Any small diaspora communities that do exist are not associated with any foreign policy interest group. Only member states of the United Nations are listed; dependent or disputed territories visible on the map are not listed.

Overall, Figure 1 shows the extreme diversity of diasporas in the United States as well as the remarkable variation in the political mobilization of diaspora communities. A majority of diasporas have not mobilized to influence U.S. foreign policy. Understanding why certain communities mobilize while others do not therefore promises to offer unique insights into popular mobilization, diaspora politics, and the effects of global immigration on the United States.

Independent Variables

We have two primary independent variables of interest: democracy and conflict. First, in our models we account for community experience with democracy by considering the degree to which individuals have emigrated from democratic states (Liberal Democracy). As a proxy, we adopt the measure of “liberal democracy” from the Varieties of Democracy (VDEM) dataset (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Staffan, Skaaning, Teorell and Altman2018). This measure offers a macro-level assessment of the degree to which democratic governance and the rule of law is institutionalized in a country.Footnote 14 Specifically, we calculate the average liberal democracy score for the period 1996–2005, as we posit that there is a lag between the years during which individuals were exposed to democratic governance and the existence of a lobby organization in the 2000s or 2010s.Footnote 15 All else equal, the higher the average score for a country of origin, the higher the likelihood that its diaspora is associated with a foreign policy lobby organization.

Second, we develop a measure of conflict in the countries of origin that could instigate diaspora mobilization (Violent Conflict). In particular, we focus on violent conflict as an issue that would most likely galvanize diasporas into political action. We construct a relevant measure using data from the UCDP–PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset (Gleditsch et al. Reference Gleditsch, Wallensteen, Eriksson, Sollenberg and Strand2002; Allansson, Melander, and Themnér Reference Allansson, Melander and Themnér2017).Footnote 16 In order to capture the severity of armed conflict across countries, we calculate the total number of conflicts that have cumulatively led to over 1000 deaths in countries of origin in each year from 1996–2005, aggregated for the decade. We posit that the number of deaths is an indicator of major upheaval that will most likely garner the attention of a country’s diaspora and motivate individuals to become politically engaged. Conflicts that have not reached a cumulative intensity of 1,000 deaths are less likely to galvanize attention. If a country of origin has multiple conflicts that have caused over 1,000 deaths in a given year, its plight is more likely to inspire mobilization than when there are fewer or no conflicts which have engendered such high levels of violence.Footnote 17 We anticipate that conflicts in the period 1996–2005 will be associated with interest group existence in the 2000s and 2010s.

In addition to our two primary independent variables of interest, we control for a variety of factors that could influence the existence of diasporic foreign policy interest groups. This includes a diaspora’s population size (Population), its geographic concentration (Geographic Concentration), integration into American society (Poor English), relative education levels (Bachelor’s Degree or More), and wealth (Income). Our models also account for diaspora social ties with countries of origin via the relative economic importance of remittances for each country of origin as a percentage of its GDP (Remittances) and the existence of formal diaspora-oriented public institutions in each country of origin (Diaspora Institutions). Economic and security relationships between the United States and countries of origin are also included. These last two factors are represented by the volume of trade (Trade) and the existence of a formal defense pact between the United States and respective countries of origin (Alliance). In online appendix 2 we discuss the data sources and measurements for these variables and in online appendix 3 we provide summary statistics for all variables in our models.

Analysis

We estimate cross-sectional logistic regression models for the years 2007, 2010, and 2015 to assess the validity of our hypotheses.Footnote 18 We selected these years as they bookend the data we collected from the Census Bureau. We do not have data for geographic concentration for the years 2007–2009, so only our 2010 and 2015 models include this variable.

In addition to certain temporal limitations, several of our variables limit our sample size to only a subset of all diaspora communities. Specifically, the Census Bureau only collects granular data about the characteristics of foreign-born populations that exceed 65,000 people. Thus, we only have measures pertaining to the wealth, education level, and language ability for seventy-two out of 110 diaspora communities.Footnote 19

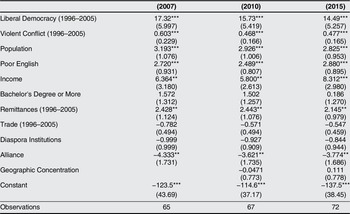

Tables 1 and 2 display the results of our quantitative analyses with the original data we collected and Paul and Paul’s data, respectively. The DV is a dichotomous variable indicating whether a diaspora is associated with a foreign policy interest group. The models in each table involve data for the three years indicated: 2007, 2010, and 2015. Data on violent conflict, liberal democracy, remittances, trade flows, and alliances are constant across models as they reflect values for the period 1996–2005. Population, English ability, education, geographic concentration, and the existence of a public institution for diaspora engagement vary across these models as values are unique to each given year.

Table 1 Correlates of diasporic foreign policy mobilization (DV: New data on interest group existence)

Standard errors in parentheses

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

Table 2 Correlates of diasporic foreign policy mobilization (DV: Paul and Paul data on interest group existence)

Standard errors in parentheses

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

The results in both tables provide support for our two hypotheses. In every model the strength of liberal democracy and the scale of violent conflict are positively correlated with the existence of a formal diaspora foreign policy lobby. The correlations are statistically significant in all models except the third model of table 1, where liberal democracy is only significant at the 10% level. This is evidence that, all else equal, democratic experience and conflict provide individuals in diasporas with the desire and know-how to become politically active and attempt to reshape U.S. foreign policy. To offer a more legible interpretation of our results, we calculated the predicted probabilities of interest group existence given the scale of violence and democratic governance in countries of origin when we use data for the year 2010, as identified in the second model of table 1. First, the predicted probability of interest group existence is equal to 30.1% if a country of origin experienced only one conflict whose cumulative intensity surpassed 1,000 deaths in the period 1996–2005. The probability increases to 62.9% if a country of origin experienced ten such conflicts, and 96.6% if it experienced twenty-five such conflicts. Second, the predicted probability of interest group existence is equal to 17.6% if the average V-DEM liberal democracy score for the period 1996–2005 is equal to 0.1, indicating a highly illiberal regime, and rises to 72.5% if the score is 0.9, indicating a highly liberal democracy. In online appendix 5, we provide graphical representations of the marginal effects of our primary explanatory variables, and indicate the predicted probabilities given different levels of violent conflict when respectively considering only highly autocratic or highly democratic countries of origin.

Several of our control variables are also consistently correlated with interest group existence, including population size, English ability, income, remittances, and alliances. As expected, all are positively correlated with interest group existence except for defense pacts between the United States and countries of origin. Our sample of countries of origin varies across these models because the characteristics of certain diasporas are not evaluated by the Census Bureau unless their population exceeds 65,000. Nevertheless, our results hold despite the consideration of a smaller subset of countries in the earlier years. Given these findings, we conduct detailed case studies to identify the way democracy and conflict lead to mobilization.

The India League of America and USINPAC

An examination of the historical and contemporary Indian-American lobby in the United States provides additional support for our theoretical arguments. Through these case studies, we demonstrate that the catalyst for the formation of a foreign policy interest group is political entrepreneurship. Democratic experience and conflicts in the country of origin motivate entrepreneurial individuals within diasporas to engage in lobbying and lead them to mobilize other members of their community.

While the Israeli-American and Cuban-American lobbies have received extensive (and sometimes controversial) attention in both academia and policy circles, they are outliers in a pool of many diasporic interest groups in the United States. We have thus deliberately chosen to examine a lesser-known lobby that has enjoyed bipartisan support throughout its existence—the Indian-American lobby. The Indian-American diaspora has been studied for its impact on politics and economic development in India (Agarwala Reference Agarwala, Portes and Fernandez-Kelly2015; Agrawal et al. Reference Agrawal, Kapur, McHale and Oettl2011; Chakravorty, Kapur, and Singh Reference Chakravorty, Kapur and Singh2017; Kapur Reference Kapur2003, Reference Kapur2004, Reference Kapur2010; Sahay Reference Sahay2009); its identity politics (Biswas Reference Biswas2010; Kurien Reference Kurien and Koslowski2004); its partisan preferences (Raychaudhuri Reference Raychaudhuri2018, Reference Raychaudhuri2020); as well as its remittance, investment, and migration patterns based on the Indian government’s citizenship policies (Naujoks Reference Naujoks2013, Reference Naujoks, Carment and Sadjed2017). However, its foreign policy lobbying efforts within the United States have received little attention despite their relative success in shaping American policies towards India.

The Indian-American lobby in the United States has existed in two distinct phases, which allows us to test whether diasporic interest groups arise due to similar circumstances at different times holding the country of origin constant. The first phase began with the establishment of the India League of America (ILA) in 1937. The ILA was a lobby group established for promoting “the interests of our people [Indians] in America in every way.”Footnote 20 It lobbied extensively for the cause of Indian independence from British rule and its activities were a source of concern for British government authorities.Footnote 21 The ILA “informed and influenced American public opinion about India to an extraordinary degree for many years.”Footnote 22 By the late 1950s, the ILA’s activities diminished and it ceased to exist shortly after the retirement of its president in 1959. No organized Indian-American lobby existed for the next three decades.

The second phase began with the mobilization of a small group of Indian-American entrepreneurs in the late 1990s, culminating in the establishment of the U.S.-India Political Action Committee (USINPAC) in 2002. USINPAC claims to be “the voice of over 3.2 million Indian-Americans and works on issues that concern the community.”Footnote 23 USINPAC is the first and the longest active contemporary interest group for Indian-Americans. As the first Indian-American lobby since the 1960s, it serves as an excellent case to understand mobilization when there were no other foreign policy interest groups representing the community.

Using archival data for the former, and interviews with the founding members, media reports, and organizational documentation for the latter, we assess how the historic and contemporary Indian-American lobbies were formed, who formed them, and why. In both cases, highly educated, wealthy, and well-connected business entrepreneurs who were familiar with democratic governance in India prior to their settlement in the United States established the organizations. They were inspired to mobilize to influence U.S. foreign policy as a result of conflicts that were occurring in India. The two case studies validate our theoretical framework and support our argument that diasporic mobilization is a top-down effort driven by political entrepreneurs as opposed to a bottom-up grassroots affair.

Democratic Experience

I think the democratic process … is instilled at least in me, or in most of the people who come from the Indian region.

—Sanjay Puri, USINPAC president, August 28, 2018

The ILA and USINPAC demonstrate that the experience of elites with democratic governance in countries of origin can play an important role in spurring diaspora mobilization. Indian immigrants to the United States after Indian independence from British rule in 1947, and especially those who entered the United States since 1965, have all been exposed to a complex three-tiered democratic system. As the world’s largest democracy, India has consistently managed to extend its democratic governance to all parts of its territory, unlike many other developing countries. However, the ILA operated prior to Indian independence, so how did democracy play a role at that time?

Even though the ILA was active during British colonial rule, general elections in India were first held in 1920. Furthermore, the majority of the subcontinent’s elite fighting British rule were in agreement that independent India would be a democratically governed country. ILA built relationships with U.S. politicians based on their level of support for spreading democracy and sympathy for colonized subjects. For example, ILA president J.J. Singh’s letters to members of Congress like Emanuel Celler and Clare Booth Luce persistently drew attention to the plight of Indians under British rule and urged them to raise this issue publicly in the United States. Singh wrote to Luce in 1944 requesting her to help facilitate “the future freedom of India” as part of the Foreign Policy Plank of the Republican Party.Footnote 24 The ILA also circulated a periodical called India Today that carried the latest news on anti-British protests in India and constantly appealed to the American sensibility of equality and democracy as reasons to support India’s independence. The ILA kept highlighting the role the two countries could play as the world’s most powerful and populous democracies.Footnote 25 Thus, the democratic sensibilities of ILA’s leaders spurred mobilization to lobby members of Congress to support India’s fight against colonialism.

With respect to USINPAC, the case of one of its founding members, Robinder Sachdev, is most striking. As he described in our interview, during the 1990s, he was intimately involved in campaign efforts for the Congress Party in India, working on bringing new data-collecting techniques and information technologies into politics.Footnote 26 In turn, he asserted that his experiences in India helped him develop the necessary tools that allowed USINPAC to engage with the Indian-American diaspora as well as the U.S. Congress.Footnote 27 Although the other founding members of the organization did not have such immersive experiences with Indian democracy, several indicated that their awareness of democratic governance in India prior to their migration to the United States played a role in their desire and willingness to establish USINPAC and have an impact on U.S. politics. Thus, in both cases democratic experience played a critical role in engendering mobilization.

Conflict

Crisis empowers activism. Things are going great, activism goes down. I’m being very frank with you. If everything is good people generally say “I don’t need to do anything.”

—Sanjay Puri, USINPAC president, August 28, 2018

Along with elite democratic experience, conflicts in India resulted in the creation of the Indian-American lobby in both phases. In the 1930s, India was experiencing significant upheaval as public outcry for independence gained momentum. The civil disobedience movement was in full swing and Indian elites around the world were trying to appeal to influential figures to support India’s fight against the British on the grounds of equality and self-determination. Indeed, one of the ILA’s founders, N.R. Checker, asserted that the ILA would serve to supply accurate information about India and its quest for independence to Americans.

In turn, the ILA’s activities were primarily aimed at advancing the case for U.S. support for Indian independence. Singh regularly wrote to members of Congress, appeared on radio shows, and wrote editorials for major newspapers on the ills of colonialism and the violence inflicted on colonial subjects.Footnote 28 Thus, colonial violence and the independence movement in India motivated the Indian community in the United States to organize and advocate for a change in U.S. policy towards Britain’s colonies.Footnote 29

In the case of USINPAC, two conflicts preceded the formation of the organization. Sanjay Puri, the founder and chairman of USINPAC, mentioned India’s and Pakistan’s 1998 nuclear tests as a critical turning point, motivating the Indian-American community to counter the negative narratives regarding India that became widespread at the time.Footnote 30 This was the first crisis moment that mobilized the Indian-American community. Second, the inter-state Kargil conflict between India and Pakistan led to fears of nuclear instability in South Asia, which required mobilizing support in the United States for recognizing that India was a responsible nuclear power despite its absence from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). Actively lobbying for the India-United States Civil Nuclear dealFootnote 31 and its subsequent success are indicative of USINPAC’s efforts in the early stages of its existence (Marwaha Reference Marwaha2016). Thus, with respect to both the ILA and USINPAC, there is strong evidence that conflict played a significant role in instigating diaspora mobilization.

Political Entrepreneurs

From my perspective, as an entrepreneur, the joy of entrepreneurship is that you created something … In a sense, it [USINPAC] was a start-up, creating something even though it was international affairs.

—Robinder Sachdev, USINPAC founding member, January 28, 2019

Finally, both the historic and contemporary Indian-American lobbies demonstrate the importance of political entrepreneurship for diaspora mobilization. Both the ILA and USINPAC were founded by small groups of individuals who were mainly business entrepreneurs by profession, highly educated, and well-connected individuals. The ILA was established in 1937 by N.R. Checker, a businessman, along with other leading business and intellectual figures such as Haridas Muzumdar, Syud Hossain, Krishnalal Shridharani, and Anup Singh Dhillon (Malik Reference Malik1991).Footnote 32 The presidency was taken over by Sirdar J.J. Singh, another businessman. They all cultivated close ties to many politicians in Washington, DC, by the 1930s. For instance, it was noted that Hossain was charismatic and “brilliant in oratory,” which made “the most favorable impression” on American policymakers (Muzumdar Reference Muzumdar1962, 13).

The archival records of J.J. Singh’s two friends and Congresspersons, Emanuel Celler and Clare Boothe Luce, contain numerous personal and official letters and telegrams from Singh on the issue of U.S. support for Indian independence. Singh and Checker also had ties with the Indian National Congress (INC),Footnote 33 both prior to Indian independence and after. Singh had been actively involved in anti-colonial activities as a member of the INC, and had established a personal friendship with Jawaharlal Nehru’s sister, Vijaylaxmi Pandit.Footnote 34 He used his connection with the Indian elite to convey the political mood in India to U.S. policymakers to make a more convincing case for Indian independence.

The important point here is that Singh’s entire strategy was to reach out to influential politicians personally. Singh’s entrepreneurial spirit is evident in media descriptions of him as a “one-man lobby”Footnote 35 and India’s “unofficial envoy”Footnote 36 to the United States. He “assiduously courted Americans in and out of government” and “testified before Congress” as well (Clymer Reference Clymer2010, 23). Pearl S. Buck, Nobel laureate and Honorary President of ILA, referred to Singh as “the mainstay and backbone of the India League” whose success was due to his “courage, humor, and dynamism.”Footnote 37 The fact that the ILA shut down shortly after his departure further indicates that the organization did not emerge from a grassroots movement but rather constituted an elite enterprise.

USINPAC, in turn, was established by a small group of Indian-American businesspersons led by Sanjay Puri and his primary collaborators—Robinder Sachdev, Vikram Chauhan, Dolly Kapoor, Manish Antani, and Manish Thakur. Sachdev had participated in political campaigns in India and thus had experience with the democratic process and knowledge that would be extremely useful in the establishment and operation of a PAC. However, none of the founders had experience in U.S. politics prior to establishing USINPAC. They nevertheless had the resources and know-how to form new connections on Capitol Hill. According to Puri, they were “exceptionally passionate, exceptionally talented, [and] like me had zero background in U.S. politics” but were determined to lobby legislators in order to give them a more comprehensive understanding of India.Footnote 38

USINPAC’s top-down mobilization effort is evident on hearing accounts of their formation. Chauhan recounted their motivations for co-founding USINPAC with a small team as wanting to give Indian-Americans a voice. He said, “you live in the country, and you want to be part of the mainstream, and you complain that people walk over you— my voice isn’t heard—that is part of the reason we got into it.”Footnote 39 According to Sachdev, he was connected to Puri via a common acquaintance and “that is how we got together, Sanjay, I, and then a few others informally, and we hung out at Tysons and just brainstormed as to why and what was needed.” He added that “we were a small team initially, so we were all pitching in with everything.”Footnote 40 Antani asserted that all they wanted was to get Indian-Americans active and organized.Footnote 41

Puri told us that India’s “story was being told from a one-dimensional lens and not from a multi-dimensional lens” on Capitol Hill. Though he felt that “the responsibility also is the Indian-American community’s” to come forward to correct the record, he claimed that it took a lot of effort to reach out to and raise awareness amongst Indian-Americans. He said that “educating the Indian-American community as to why there is a voice that is needed was as hard a challenge as educating members of Congress.” They would reach out to “50–60 people at least a day … We were doing a lot of events at that time because the awareness was not high. At least one or two events a month.”Footnote 42 “We had to go out, outreach, knock on doors, connect, talk to people, within the Indian community also, as to what are we doing and why—what is with this thing [USINPAC],” said Sachdev, corroborating Puri’s description.Footnote 43 The difficulty in keeping the broader Indian-American community engaged on foreign policy issues is understandable given that only 3% of Indian-Americans ranked U.S.-India relations as their most important election issue in 2020 (Badrinathan, Kapur, and Vaishnav Reference Badrinathan, Kapur and Vaishnav2020). Thus, the efforts of a handful of political entrepreneurs led to mobilization.

In both cases, there is no evidence that the ILA or USINPAC were founded as a result of broad-based grassroots mobilization. Indeed, in the 1930s, the Indian-American diaspora was quite small, making a grassroots movement unlikely. For USINPAC, all our interviews indicated that the founders were driven by their own personal initiative, motivations, and ideals. Their mobilization efforts were independent of any community-wide desire for lobbying. In fact, some indicated that the apathy in the Indian-American community to politically organize motivated them to start USINPAC. They all indicated that their primary challenge was to engage the broader Indian-American diaspora for the purposes of fundraising and obtaining other support. Their descriptions of the founding of USINPAC consistently indicated that mobilization was an entrepreneurial affair. Additionally, USINPAC had to create a database on Indian-Americans from scratch in order to reach out to the community. Dolly Kapoor, one of the first members of the organization, said that “my job was to make sure that the grassroots were getting involved. So I really started as the grassroot outreach person.”Footnote 44 Thus, USINPAC started with a small group of entrepreneurs who reached out to the larger Indian-American community.

Ultimately, while the conditions for interest group formation existed in both cases, entrepreneurs were critical in bringing together Indian-Americans and catalyzing support for their organizations. These leaders were able to capitalize on their entrepreneurial skills and sought to influence members of Congress on foreign policy issues related to India and Indians in America. Thus, democratic experience and conflict in the country of origin, India, made it more likely that political entrepreneurs would establish formal interest groups geared toward influencing U.S. foreign policy.Footnote 45

Conclusion

Unlike previous studies on diasporic interest groups that focus on the degree to which they effectively influence U.S. foreign policy, we examine why only certain diaspora communities choose to form an interest group in the first place. We argue that two key factors influence the likelihood of diaspora mobilization in the United States. First, elites’ experience with democratic governance in their countries of origin socialize them in a setting that allows for political engagement by citizens. The stronger the democratic governance of a country of origin, the more likely that a foreign policy interest group affiliated with its diaspora exists in the United States. Second, conflicts in countries of origin makes the existence of diasporic interest groups more likely. The desire to draw attention to political upheavals and influence United States policy vis-à-vis a country of origin increases the likelihood that diasporas mobilize to form an interest group.

Our hypotheses hold in both our quantitative and qualitative analyses. Quantitatively, democratic governance and the intensity of the conflicts in countries of origin are positively correlated with the existence of diasporic interest groups in the United States. Both variables are statistically significant across all our logit models. In our case studies of the Indian-American lobby—both in its historic incarnation from the 1930s to the 1960s and its present version since 2002—our hypotheses likewise hold. In addition, we draw out the mechanism through which policy entrepreneurs act as catalysts for diaspora mobilization. Through our cases, we show that diaspora mobilization is elite-driven and top-down as opposed to broad-based and bottom-up. Political entrepreneurship can thus play an important role in facilitating the formation of formal organizations for political engagement.

Our findings have both academic and policy implications. With respect to diasporic interest groups, our theory can be expanded to apply to other democratic countries that have highly diverse immigrant populations such as Australia, Canada, France, and the United Kingdom. Comparing the Indian diaspora’s mobilization (or lack thereof) in these countries would reaffirm the mechanism behind mobilization while holding the country of origin constant. Our theory also helps policymakers understand why diasporic interest groups would want to mobilize and petition the government in the first place. Studying the host government’s agency in encouraging diaspora mobilization would be beneficial as well.

Future research can build on intergenerational partisanship analysis (Raychaudhuri Reference Raychaudhuri2018) to examine variation on mobilization for diaspora lobbying as well as partisan preferences for foreign policy mobilization. The role of in-group cleavages is also worth exploring. Additionally, future research can examine under what conditions diasporic interest groups die out. Interest groups go through cycles (McFarland Reference McFarland1991) and studying that pattern of group evolution will help ascertain the conditions for their survival. Finally, we identify factors that influence public mobilization that have not been examined previously. Experience with democracy, political conflict, and the entrepreneurial spirit of certain individuals are important for understanding collective action in the United States and beyond.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592721000979.

-

1. Foreign Policy Interest Groups

-

2. Rationales and Data Sources for Control Variables

-

3. Summary Statistics

-

4. Sensitivity Analyses

-

5. Predicted Probabilities

-

6. Case Study: Discussion of Alternative Factors

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jesse Acevedo, Andrew Bennett, Charles King, Robert J. Lieber, Mirjana Maletic-Savatic, Inu Manak, Abraham Newman, Irfan Nooruddin, Alexander Sullivan, Erik Voeten, and four anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and feedback. They appreciate the input of conference and workshop participants at Midwest Political Science Association Annual Conference (2018 and 2019); International Studies Association Annual Convention (2019); Central and Eastern European International Studies Association-International Studies Association, Joint International Conference-Belgrade (2019); Politics of Race, Immigration, and Ethnicity Consortium (2018); University of Pennsylvania Andrea Mitchell Center Graduate Workshop (2018); and the Georgetown Department of Government Graduate Working Group (2018). In addition, they thank the Ethnicity, Nationalism, and Migration Studies Section of the International Studies Association for the Martin O. Heisler Award (2019). The authors are especially grateful to the USINPAC team—Sanjay Puri, Robinder Sachdev, Manish Antani, Dolly Kapoor, and Vikram Chauhan—for their interviews.