A Colombian human rights activist describes the threats and frustrations faced because of her activism, and the impact these had upon her, as follows:

I have experienced threats, break-ins at my house, and plans to kill me. I am thinking of stepping back, to accompany other processes maybe, I won’t withdraw totally, that’d be impossible.… I accompany victims 365 days a year. I’m tired, physically, mentally, and psychologically, of seeing the anxiety of people, of the pressure of cases that don’t go anywhere. What do the victims do? They vote for their aggressors! I can’t understand that. Maybe it’s the poverty.

(A4)This quote makes evident how activists working in high-risk environments have to cope with a range of dispiriting emotions that affect their well-being and ability to sustain their commitment. Moreover, it highlights the complex relationship between individual emotional states and exposure to repressive tactics and difficult adversarial environments. As such, it points to three understudied questions in the study of collective mobilization and contentious politics: What are the emotional challenges faced by activists working in complex high-risk environments? How are these emotional challenges exploited by state and opposition actors? How do emotional states, contextual factors, and repression interact to shape the extent of individual (dis)engagement?

To explore these questions, we propose the concept of emotional attrition, defining this as the process by which sustained threats, attacks, risks, and deprivations impose demands for emotion work by committed activists, such that if these demands become overwhelming, they will lead to emotional exhaustion and, potentially, to their partial or full disengagement. We argue that this process plays a major, yet little understood, role in the functioning of repression and in the evolution of contentious politics dynamics. This is because we understand emotional attrition not just as an individual-level cognitive process but also as a relational one regulating how individuals and groups perceive and react to targeted and routine adversity: it shapes how they perceive opportunities and evaluate risks, it conditions their inclination to trust and to be in solidarity with others, and it modulates the motivating appeal of calls to action. Moreover, because emotional states and their effects operate continuously and not just episodically, emotional attrition is central to understanding the challenges to political action and activism beyond the more visible instances of mass mobilization and political confrontation that generally attract the interest of political scientists and social movement scholars. As such, it emerges as a powerful notion to capture the situated realities of political action and to inform what Fu and Simmons (Reference Fu and Simmons2021, 19) call “one of the most difficult questions in contentious politics—why people do not mobilize.”

By considering emotional attrition relationally, we embrace a perspective that supports the study of contention mobilization, radicalization, and repression in an effort to correct the “structural bias” of the process model tradition (McAdam and Tarrow Reference McAdam, Tarrow, Snow, Soule, Kriesi and McCammon2019, 21): our approach highlights the encounters and dynamic interactions between individuals, groups, and institutions in the variegated, coevolving arenas where actual politics occur and where activists and protesters work and live (Balcells and Justino Reference Balcells and Justino2014; Della Porta Reference DellaPorta2018; Fligstein and McAdam Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012; Goldstone Reference Goldstone2004; Jasper Reference Jasper, Duyvendak and Jasper2015). Concretely, our conceptualization of emotional attrition integrates one internal and one external mechanism—emotional exhaustion and attrition, respectively—which have been left unconnected in the study of contentious action. First, emotional exhaustion, usually conceived in terms of prolonged stress and burnout, is generally treated as an individual occupational hazard that predominantly affects people in professions characterized by high normative expectations, such as political activists, but where success is limited or delayed, potentially resulting in emotional (and behavioral) disengagement from work (Chen and Gorski Reference Chen and Gorski2015; Pines Reference Pines1994). Attrition, in contrast, has been presented as a modality of “soft” repression repertoire suited to deal with protest groups that cannot be openly coerced, involving the “gradual undermining of protesters’ claims and group strength through the proactive and sustained use of pressure while avoiding the use of repression” (Yuen and Cheng Reference Yuen and Cheng2017, 617; see Bishara Reference Bishara2015). We expand the functioning and implications of both this hazard and mode of repression into a model that considers how dispiriting emotional states and adversarial factors intertwine and reinforce each other to dampen political activism and protest dynamics over time.

This article tackles an important gap regarding the role of emotions in the politics of protest and repression and in the lifecycle of contentious mobilization. Although we agree with Pearlman (Reference Pearlman2013, 391) that emotions are key mechanisms “cutting to the foundations of political science” and that they are constitutive of patterns of political action and inaction, their contribution to collective mobilization has been largely discussed in positive terms. Thus, whereas the sociological literature tends to focus on how emotions grant “ideas, ideologies, identities, and even interests their power to motivate” and are used by political entrepreneurs and social movement actors to cope with repression and resist closed opportunity structures (Jasper Reference Jasper1998, 420; Reference Jasper2018), political science and comparative studies have been more interested in how emotions influence the more visible (and measurable) upward side of contention, as well as their impact on processes of radicalization, revolutionary regime change, and political violence (Della Porta Reference DellaPorta2018; Johnston Reference Johnston, Demetriou and Bosi2016; Petersen Reference Petersen2011). As such, only a limited and rather recent literature has investigated what happens when protesters fail to cope with fear, anguish, or despair and how dispiriting emotions contribute to demobilization and the deactivation of contentious opposition (Fillieule Reference Fillieule, Della Porta and Diani2014; Van Ness and Summers-Effler Reference Van Ness, Summers-Effler, Soule, Kriesi, McCammon and Snow2018; Van Troost, van Stekelenburg, and Klandermans Reference Van Troost, van Stekelenburg, Klandermans and Demertzis2013). The lack of attention to the affective dimension is also observable in the literature on repression and countermovement tactics (Davenport Reference Davenport2015; Earl Reference Earl2011; Peterson and Wahlström Reference Peterson, Wahlström, Della Porta and Diani2014; Robertson Reference Robertson2011). Although there is often an implicit recognition that both hard and soft tactics bank on complex negative emotions and collective moods such as cynicism and despair, which lower expectations of change, the centrality of emotional mechanisms in shaping the workings of state repression and the conditions enabling regime persistence has been sparsely elaborated (Bishara Reference Bishara2015; Pearlman Reference Pearlman2013; Young Reference Young2019).

By elaborating how adversarial conditions generate damaging, even pathological, emotional states in political activists and citizens, we contribute to two difficult and related “how” questions about movement dynamics and patterns of political contention: how repression actually works and how people live under repression (Fu and Simmons Reference Fu and Simmons2021). We outline a more comprehensive treatment of repression beyond the state, regime structures, and protest, as we provide evidence that activists can suffer emotional attrition not only because they are strategically targeted by security actors during a contentious episode but also because of the complex challenges of living and conducting their everyday activism in environments marked by durable and intersecting deprivations and risks. Consequently, tactics that may not cause direct physical harm can have major damaging effects in the context of serious institutional deficiencies, patterns of social antagonism and prejudice, and economic constraints or organizational, community, and family pressures.

At the same time, while emotional attrition can potentially affect committed activists because of the demanding nature of their work, the concept goes beyond the internal or workplace-related experience of activist burnout (Hopgood Reference Hopgood2006). We argue that emotional attrition serves to illuminate the “reality of movement participation” (McAdam Reference McAdam1986, 66) and how adversity (including repression) entails relational dynamics emerging from activists’ embeddedness in multiple and interacting arenas. Not only resources but also vulnerabilities and constraints spill over from one arena to another, such as when repression tactics or job insecurities poison activists’ intimate relations with their family and friends, or sow mistrust among collaborators and other institutions in society, such as the media or courts.

Second, we make advances toward a more integral theorization of role disengagement, activist defection, and the decline phase of the protest cycle. Considered by Koopmans (Reference Koopmans, Snow, Soule and Kriesi2004, 37) to be one of the weakest chains in social movement research, movement decline has remained conceptually sidelined as an uninteresting and obvious “part of the natural, and seemingly inevitable, sequences movements move through” (Owens Reference Owens2009, 16). But just as repression can operate beyond protest, we consider that decline can be in play beyond fatalistic treatments of movement death as complete demobilization. Our study of emotional attrition brings analytical coverage to “partial” forms of demobilization, which are conceivably more common and representative of the concrete dilemmas faced by local activists in many locations around the world, who remain at work but live at risk, forced to moderate or suspend their activities to recover their health or protect themselves and their families. By considering how emotional attrition can damage activists’ motivation and make them more fearful (and perhaps risk averse in the longer term), we extend conceptualizations of demobilization and decline to involve not only the end of activism but also the progressive and durable deterioration of its intensity and effectiveness.

To sum up, through a relational treatment of emotional attrition, this article illustrates the manner in which complex intersections between individual, social, and strategic adversarial factors can erode activists’ emotional and social well-being and, with it, their capacity to work and exercise their activism. Although a micro-level psychosocial mechanism lies at the core of the proposed process, our argument contributes to a more nuanced and sensitive understanding of the politics of (de)mobilization and of the causal mechanisms regulating the quality and intensity of meso- and macro-level dynamics of contentious politics. To do so, we draw on the notion of emotion work, a concept sociologists developed to explore situations in which individuals have to regulate and bring their emotions in line with role-related expectations and display rules in their professional and personal lives. In the first part of the article, we outline a novel conceptual proposition that underlines how excessive emotion work results from the mutually reinforcing effect of the emotional demands inherent to activism and of pressures stemming from multiple adversarial characteristics, present both in the activists’ immediate and extended areas of action. In the second part, and following a detailed methodological discussion, we ground our analytical proposition against an extensive qualitative analysis of interview data on the experiences of more than one hundred committed activists working on human rights issues in Colombia, Kenya, and Indonesia, corroborating how adverse contexts, repression, and demands associated with activists’ lives interact to generate experiences of attrition.

The Process of Emotional Attrition

This section outlines a composite model of emotional attrition that considers the strain activists experience that results from the significant emotional demands they encounter in their work and daily lives. These demands follow from the interaction of internal personal expectations and activists’ ethical and emotional ties to their cause with three external relational arenas: the field of repression of activism, populated by diverse opposition actors; the activists’ immediate social circles, in particular their families, colleagues, and local communities; and the broader sociopolitical, economic and cultural environment in which activists and their families, as well as their opponents, operate. A general schema of the emotional attrition process is presented in figure 1.

Figure 1 The Process of Emotional Attrition

We understand this process as multicausal and contingent on the interaction of multiple mechanisms and the situated combination of personal- and external-level variables. Thus, not all activists subject to repression or working in adversarial contexts will experience emotional attrition in the same way, because a range of coping mechanisms modify the type, intensity, temporality, and demands for emotion work. In addition, not all of those who experience emotional attrition necessarily will disengage, whether partially or fully, because one can continue working while being demotivated, depressed, or sick, albeit likely in a reduced capacity. This contingency is indicated in figure 1 with dotted arrows linking emotion work, emotional exhaustion, and disengagement. Lastly, emotional attrition tends to manifest over time rather than immediately, as indicated with the circular arrow at the center of the figure.

Emotional Exhaustion, Political Activism, and Adversarial Arenas

Emotions are ubiquitous in daily life, as is the need for their regulation. Both consciously and subconsciously, we regulate and transform our emotional experiences constantly through “changes in emotional responding such as increasing, decreasing, or maintaining of positive and negative emotions” to ensure everyday functioning and to comply with social rules (Katana et al. Reference Katana, Röcke, Spain and Allemand2019, 2). Arlie Hochschild (Reference Hochschild1979, 561) put forward the concept of emotion work and defined it as “the act of trying to change the degree or quality of an emotion or feeling,” highlighting two types of emotion work: evocation, to produce desired feelings, and suppression, to reduce undesirable feelings. Central to her work is the insight that emotion management is particularly demanding in specific professions, particularly the helping occupations and service industries where a high amount of empathy and emotional involvement is required and where interaction control is low, because people can rarely pick when and with whom to deal with.Footnote 1 The demands for emotion work, usually combined with high initial expectations by the practitioner, limitations in resources, and delayed or short-lived rewards, can lead to protracted feelings of physical and emotional exhaustion.

These ideas are supported by findings in psychological and clinical studies demonstrating that individuals have a limited capacity for emotional regulation processes and that the repeated and effortful suppression of negative emotions constitutes a heavy drain on cognitive resources needed for memory, decision making, self-control, and overall social functioning (Wright and Cropanzano Reference Wright and Cropanzano1998, 486). In particular, excessive emotion work has been linked with modern occupational malaises such as long-lasting emotional exhaustion or burnout, a “psychological syndrome in response to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job” through which the individual gradually loses the capacity to cope with the effort of emotion work (Maslach, Schaufeli, and Leite Reference Maslach, Schaufeli and Leite2001, 399). These malaises are characterized by a multiplicity of symptoms conducive to decreased performance and role disengagement: emotional ones, mainly in the form of depersonalization, cognitive distancing, and sentiments of inefficacy; physical ones, such as problems of concentration, chronic fatigue, and psychosomatic disorders; and sociobehavioral symptoms like isolation and enhanced insecurity (Schaufeli and Buunk Reference Schaufeli, Buunk, Schabracq and Winnubst1996, 323–25).

An emerging but rather niche strand of scholarship has extended findings about emotional well-being and burnout to political activism, noting that the “existential significance” activists attach to their work and to their moral commitments exposes them to feelings of anger, disappointment, or cynicism (Gorski Reference Gorski2015; Nah Reference Nah2021; Rodgers Reference Rodgers2010). In this article, we focus on how the potential for emotional exhaustion is increased by the dangers of operating in high-risk environments, because activists not only challenge existing norms, practices, and traditions in society but also get in the way of the interests of powerful and resourceful opponents who may seek to deter them through a variety of means (Goodwin and Pfaff Reference Goodwin, Pfaff, Goodwin, Jasper and Polletta2001). This opposition can come not only from state actors and security forces but also from civil society and nonstate actors, ranging from business and radicalized faith-based actors to paramilitaries and criminal groups (Forst Reference Forst2018). Moreover, even when overt violence against political activists is by no means a rare strategy—according to data collected by Front Line Defenders (FLD 2020), 304 human rights activists were killed in 2019, a number that has been rising over the years—physical violence is just one of the repressive repertoires deployed to punish and deter activism. Increasingly, so-called soft or low-intensity forms of repression are being used by authoritarian and democratic states to deprive activists of valuable resources—time or money mainly, but also personal security or allies—and elicit a variety of discouraging sentiments (Earl Reference Earl2011; Robertson Reference Robertson2011; Yuen and Cheng Reference Yuen and Cheng2017).

In this regard, we distinguish three sets of soft repressive approaches, which overlap with each other and rely on different emotional and relational effects. Intimidatory tactics operate by forcing activists to shift their attention from external objectives and considerations to the internal consequences of their actions, resulting in enhanced concerns about personal and in-group collective safety (Boykoff Reference Boykoff2007). These concerns may induce fear, making individuals more risk averse and uncertain while reinforcing the salience of repression and other stressors: scared individuals can feel insecure even when not directly threatened (Young Reference Young2019). The state of uncertainty can also contribute to the erosion of trust, reducing confidence in institutions and networks of support and complicating the formation of solidarity and intra- and intergroup alliances. Stigmatizing tactics instead draw on dominant social stereotypes to discriminate or reduce the status of certain individuals or groups. They seek to elicit negative emotions such as shame, which are common when individuals internalize their negative social status, as well as wider feelings of anxiety, resentment, and humiliation that may contribute to patterns of withdrawal, concealment, and disconnectedness (Britt and Heise Reference Britt, Heise, Stryker, Owens and White2000). At the same time, in places where stigmatization is institutionalized, as in certain composite regimes divided along ethnonational lines, discrimination and stigmatization can legitimize the application of additional repressive measures by security forces and civil society actors (Alimi and Hirsch-Hoefler Reference Alimi and Hirsch-Hoefler2012). Lastly, resource deprivation tactics are aimed at the “systematic hindering of [social movement organizations’] efforts to generate the human and financial resources necessary to continue engaging in challenging behavior” (Davenport Reference Davenport2015, 23). As such, they involve repertoires aimed at making activist work difficult, ranging from criminalization and imprisonment of leaders and members (the most reported violation by human right activists, which often subjects them to lengthy, stressful, and expensive legal proceedings), to bureaucratic barriers and censorship, to semiformal measures such as the sponsoring of countermovements or restrictions of NGO funding (FLD 2020; Protection International 2015). By turning the process of mobilization into a form of punishment, these tactics deny activists rewards or meaningful experiences and foment sentiments of frustration, inefficacy, and hopelessness (Lit Yew Reference Lit Yew2016, 561). Moreover, competition for scarcer resources contributes to organizational atomization and weakened solidarities, in addition to inducing partial disengagement because some groups may moderate their strategies to avoid penalties.

Repression techniques, however, not only affect individual activists and protest organizations but also create ripple effects across activists’ personal networks, the second relational arena in figure 1. Colleagues, family members, and friends are among the first to be affected by any repression tactic, whether directly or indirectly, because they are exposed to physical dangers, financial hardship, and social stigma, as well as the negative externalities that may follow from the protection measures activists may adopt (i.e., movement restrictions, relocation, exile; Amnesty International 2017). This extended vulnerability not only augments sentiments of guilt and responsibility but also creates further tensions within the family and community groups. Although these social circles can function as safe spaces where activists can find solace and support, family-related security concerns, as well as feelings of guilt about the detrimental impact of their activism on loved ones, create additional emotional demands on activists, especially when they work in the same communities in which their families live. Moreover, these tensions and sentiments strongly intersect with contextual social identities and role inequalities. Women activists can be further stigmatized for putting their children in danger and being “bad wives and mothers”; minority or LGBTIQA+ activists may be accused of bringing shame to their family, elders, and community (Womens Human Rights Defenders International Coalition 2012, 16).

The last arena in the model is the most encompassing, if we consider that the previous ones are part of the overall context where activists operate. Hence, on the one side, the application and effectiveness of repressive repertoires are conditioned by regime type and general institutional features, including factors such as regime ideology, the degree of security of the officeholder, and the politicization of cleavage structures (Aytaç, Schiumerini, and Stokes Reference Aytaç, Schiumerini and Stokes2017; Tilly Reference Tilly2006). Although scope conditions such as the rule of law, high state capacity, and democratic institutions can lead to successful activist outcomes, situations where people distrust the state or security forces, where there is widespread crime or an entrenched culture of impunity, or where civil society is marked by high levels of political antagonism and discrimination can contribute to a sense of institutional and personal isolation expected to increase activists’ emotional load.Footnote 2 Moreover, in many places there is a generalized attitude of mistrust and even hostility toward political and human rights activists, not just from the authorities but also from the media and even major segments of the public; in such situations activists can be viewed as “foreign agents” touting values that run counter to national interests or culture, or as radical ideological figures seeking to alter deep-seated practices and norms. This situation aggravates insecurity, isolation, and anomie, because activists may feel that large segments of society are against them, and politicians, journalists, or the police may have limited interest in helping when acts of aggression are committed against them.

These three arenas are constantly interacting with each other, conditioning the emotion work that activists have to do to navigate the injustices and violations they experience or witness, the environmental threats and dangers, and the pressures from personal relations. As we note in figure 1, the intensity of the emotion work is constantly regulated by coping mechanisms and resources. Although a detailed discussion of these mechanisms is beyond the scope of this article, a few considerations drawn from the clinical literature are important to our argument. First, coping strategies perform two functions: they deal with the situation that is causing distress (problem-focused coping) and regulate the associated emotion (emotion-focused coping; Folkman et al. Reference Folkman, Richard, Lazarus and Delongis1986, 572). At the same time, there are two main types of coping strategies: active (“control”) and passive (“escape”); that is, actions and cognitive (re)appraisals oriented toward taking charge of the situation or problem or toward avoiding it. With reference to our argument, we can assume that local activists in high-risk environments, who usually possess limited resources to change the negative circumstances they confront, can be expected to be more reliant on emotion-focused coping strategies (Downton and Wehr Reference Downton and Wehr2019). However, if for some reason these opportunities and resources are scarce, unavailable, or depleted—and evidence indicates that many activists pay limited attention to their psychological well-being and can rarely access specialized therapy or mentoring schemes (Satterthwaite et al. Reference Satterthwaite, Knuckey, Singh, Wightman, Bagrodia and Brown2019)—the alternative left to them would be coping by escape: to the extent that they fail to see a way out, individuals would seek to numb or detach themselves emotionally, leading to emotional exhaustion and attrition.

Methodology and Data

This article draws from extensive interview data collected as part of a larger research project designed to examine how human rights activists navigate risk and manage their security in different political and cultural environments.Footnote 3 Although exposure to different forms of risk and dangers was a primary selection criterion for participants, the original project was not aimed at studying emotional attrition or disengagement as such. Thus, our study performs a secondary analysis of a preexisting dataset, conducted on the basis of different research questions, a distinct conceptual approach, and a separate coding technique (Heaton Reference Heaton1998). Although secondary analyses present several methodological and ethical considerations, and not all datasets may be amenable to this approach, we consider our data to be well suited for a robust analysis of emotional attrition dynamics. A major factor contributing to this robustness is that references to emotion work and symptoms of emotional exhaustion emerged as part of general “feeling-thinking” reflections by activists on hardships associated with their actions and their routine interactions with state institutions, their families, and local communities—without being asked directly about this topic. Moreover, even though all participants were involved in human rights activism at the time, more than one-third linked their insecurities and emotional state to instances of partial disengagement, ranging from demotivation, chronic stress, and task demotion (i.e., abandoning risky activities for safer ones) to relocation, temporal suspension of work, and medical leave. In this sense, although we cannot comment on the situation of fully disengaged activists, our data cover the experiences of committed activists who were struggling with adversity or who would have liked to “take a break” but could not do so.

We analyzed 133 one-to-one interviews with human rights activists in Colombia, Kenya, and Indonesia who had experienced risk, threats, or attacks within the past five years. In each country, we used a similar purposive nonrandom sampling strategy to identify and recruit a variety of activists, who were diverse in terms of their place of activism (urban vs. rural), gender, age, level of experience, and areas of activism (including civil and political rights; economic, social, and cultural rights; environmental governance; rural and indigenous rights; and the rights of women, LGBTIQA+ communities, minorities, and postconflict victims and political prisoners). Efforts were made to include an equivalent number of men and women activists and a minority of trans persons. Because trust in the interviewer was critical to participation, activists were selected and interviewed by trained local research teams familiar with the human rights community in each country: each team comprised a man and a woman, and each received the same interview guidelines. Interviews were conducted in Spanish (Colombia), Kiswahili or English (Kenya), and Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesia) and took place between July 2015 and April 2016. We then uploaded the translated transcripts to NVivo to code, aggregate, and compare the data. Importantly, given that all interviewees were considered at risk, the participants’ details have been fully anonymized, including the location and date of the interviews.

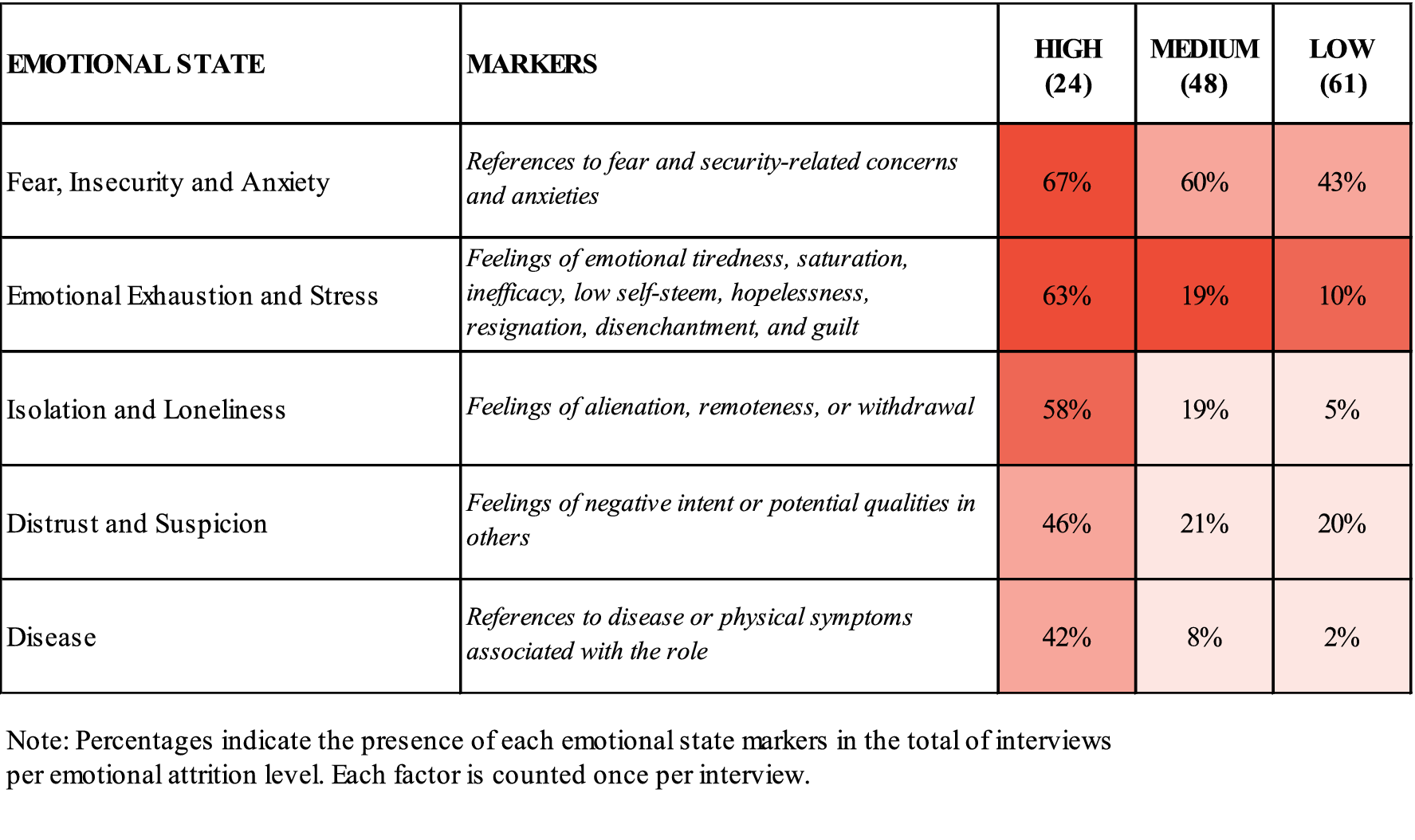

The coding process was iterative, combining inferential coding, preset codes, and interpretive adjustments (Elliott Reference Elliott2018). In the first round we organized interview data according to broad themes and categories, which allowed us to identify the three arenas discussed in the theoretical section and to develop a scheme of codes to map specific factors and dynamics. We relied on the literature on repression and political violence to define codes for perpetrators, tactics, and adversarial contextual factors, and on clinical literature to identify responses associated with emotional exhaustion— which we then grouped into five aggregate emotional states: fear, insecurity, and anxiety; emotional exhaustion and stress; distrust and suspicion; isolation and loneliness; and disease. As much as the transcripts allowed, this first-level coding followed Retzinger's (Reference Retzinger1995) approach to verbal, visual, and paralinguistic “markers” in interview communication—recognizing, for example, that codewords for shame can include the use of many other terms, such as “rejected,” “alone,” “inept,” or “jittery.”Footnote 4 Recognizing that emotional attrition varies in intensity as a continuum, and to draw out differences and explore patterns and relationship between variables, in a second round of coding we classified interviewees into three categories according to the intensity of emotional attrition they experienced/expressed: high, medium, and low. To do so, we combined a formal approach that considered the number of emotional markers mentioned by each activist with more qualitative considerations about the intensity of their experiences and “symptoms.” This was done to distinguish between instances where different individuals refer to similar emotional markers but with different severity or cases where no explicit markers are present but there are aggravating contextual or behavioral clues, such as serious experiences of repression, “exiting desires,” or health-related leave. Figure 2 shows the results of this process, with 24 participants coded as high-attrition activists (HAAs), 48 as medium-attrition activists (MAAs), and 61 as low-attrition activists (LAAs)—respectively, 18%, 36%, and 46% of the dataset.

Figure 2 Emotional Experiences by Level of Attrition

Because the participant sampling was purposive, these data do not aim to be representative probabilistically. However, the extensive breath and diversity of our sample, which are rare in qualitative studies, enabled us to combine the “intimacy of analysis” of qualitative comparative analysis (Tarrow Reference Tarrow2010, 243)—facilitating the identification and tracing of similar mechanisms in different geographical, cultural, and sociopolitical circumstances—with attention to diverse scope conditions of large-N studies, reinforcing the generalizability and validity of our observations and findings.

The Relational Dynamics of Emotional Attrition

Committed political activists display a broad range of dispiriting emotions when describing their challenges and negative experiences at work. The intensity of the emotional effort needed to manage these emotions is heavily conditioned by the context in which this work is done, with adverse environments expected to increase the effort of managing negative emotions. In our analysis we found that participants discussed seven aspects of their contexts in relation to the emotional demands they faced: a state they could not trust, impunity, economic constraints and deprivation, political antagonism, generalized crime and violence, corruption, and discrimination and social stigma. Figure 3 reflects the extent to which high-, medium-, and low-attrition activists mentioned these grievances and indicates how activists with different levels of intensity of emotional attrition focused on different factors.Footnote 5

Figure 3 Relevance of Contextual Factors by Level of Attrition

Indeed, across all three national contexts, both economic problems and incidences of violence, crime, and antagonism between different social groups, including the state, were widespread and were noted to have important detrimental consequences for activists. This was particularly true for Colombia, where a long-lasting civil war (1964–2016) created an environment of continued violence, significant political polarization, and the damaging presence of clandestine nonstate actors across the territory. Working on land issues or the rights of displaced persons or of war victims in such a conflictual context is often perceived as siding with “the other side”—be this the state, the guerrillas, or the paramilitaries. Similarly, in Kenya, where tribal lines matter, support for some victims of human rights violations may be interpreted as siding with the particular tribe the victim belongs to, exposing activists to threats and discrimination by other community actors.Footnote 6 In Indonesia, the combination of past separatist conflicts and ongoing religious radicalism creates a hostile environment for activists where “people can be easily provoked to conduct violent acts in the name of religion” (C22), and state security forces are often unwilling and incapable of guaranteeing their safety.

However, it is interesting to see in figure 3 that HAAs attribute greater weight to “indirect” factors involving more generalized and institutional-level grievances, such as lack of trust in the state, impunity, and political antagonism, than to more immediate factors that could affect their person or in-groups, such as targeted violence or discrimination. This would be consistent with the appraisal effects expected from emotional exhaustion and the dispiriting emotional and behavioral symptoms discussed in the prior section, insofar as HAAs can be expected to consider their environment in more holistic and “structural” negative terms than MAAs and LAAs. Thus, although violence and crime are major adversities for all types of activists, HAAs are considerably more suspicious of state agents and institutions and express highly cynical views of the state as a whole. As a Colombian activist opined, “Colombian law is absurd, risible.… Human rights exist on paper; they’re not for real. It’s not effective asking for help. No one ever bothers to find out what happens. So, it’s just not worthwhile asking” (A4). A Kenyan activist described a similar feeling: “I know what kind of state I deal with, insidious in attitudes towards critics, observance of the rule of law is poor, such record of abuse.… I went public and recorded a statement with the police—but this is always part of the motion, because we know that nothing happens” (B4). This distrust in turn relates to the salience problems of impunity and political antagonism, because HAAs see violence and crime not as occasional events but as permanent and pervasive features of the institutional context and attribute responsibility for them to the complicity of the state and security forces. Thus, they highlight how reports of threats or attacks against them or their family members were often dismissed or not taken seriously; in some cases, activists were even blamed for their own victimization by state authorities. Given the taken-for-granted “collusion” of perpetrators and state institutions, some activists decide not to report attacks; going to the police could endanger their families and bring their actions under the spotlight of authorities while having no meaningful consequences for perpetrators. As discussed later, impunity and distrust for state institutions perpetuate feelings of hopelessness, futility, and isolation: activists find themselves “numb with threats” (C5), as an activist in Indonesia described, and where “they’ve got you where they want to,” as shared by a Colombian activist (A12).Footnote 7

This position of institutional isolation and distrust is exacerbated by an enhanced sense of economic vulnerability, with around half of HAAs and MAAs mentioning economic constraints and insecurities as major factors affecting their capacity to deal with risks and emotional strain. This was particularly the case for those with lower socioeconomic status and those who did human rights activism as volunteers or in very small organizations, meaning that they sustained themselves and their families through other, often precarious jobs. Thus, a Kenyan activist reported, “In Kenya, many don’t have the resources to take real steps that would alter their circumstances (home, office security, etc.). We don’t have the resources and we are often not paid for our work” (B4), whereas a Colombian activist declared that few of them had social security (A15). This precariousness negatively affects activists’ sense of autonomy and, as we later explain, gives rise to considerable stress and anxiety, while making them particularly sensitive to resource deprivation tactics or reputational threats that could affect their own or their families’ work opportunities. An Indonesian participant also pointed to the pressures of balancing her advocacy for the freedom of religion with her job as a university lecturer and the lack of support given to her when she is exposed to risks:

I wrote a blog in 2014 about my experiences bringing my students to visit a church and a Buddhist temple in [place] to teach them about the relationship between men and women in other religions outside Islam.… I then received a call from the Rector of the [university] saying “You, a stupid lecturer, do not respect local wisdom.… I heard that [an Islamic civil organization] want to kill you.” I was asked to move and teach in a different university.… I felt depressed.

(C14)The lack of organizational support is particularly problematic when activists confront situations of grave and imminent danger: they not only risk losing their jobs but also need to rely on their limited financial resources (or their families’ or friends’) to fund additional security measures, such as temporary relocation or even exile. As put by a Kenyan activist, “Even the money spent when you are at risk, sometimes it is a lot and you don’t have a lot and you are forced to … because you need to do something and it is not planned” (B2). This problem becomes even more pronounced given the insufficient or inadequate formal protection mechanisms available in the three countries and the activists’ limited access to international protection initiatives, which are generally inaccessible for low-profile activists working in remote, rural areas.

Repression, Perpetrators, and Insecurities

Needless to say, repression has a major impact on the emotion work activists have to do. In our sample, 54% of HAA activists reported experiencing direct violent attacks (compared to 39% of the total number of participants), and 92% described one or more incidences of harassment (compared to 80% among all participants). Hence, even though experiences of violence and harassment proved common among most activists, HAAs were exposed to a greater number of incidents and more extreme episodes of harm, including beatings, the murder of family members, rape, or break-ins of their houses. This sense of extreme exposure was explicitly described by a campesina activist in Colombia when talking about an incident that followed her refusal to pay money to a paramilitary fighter: “He must have informed his boss, and when I went back the next day, people came looking for me. I was beaten and raped. They did to me what you don’t do to any human. … I looked like a piece of meat” (A10).

Violence and harassment tend to be carried out by different types of perpetrators for different types of activists. Participants working on LGBTIQA+ rights, sex workers’ rights, and some types of women’s rights mostly reported attacks by community actors. Often gatherings of LGBTIQA+ people, such as at marriages or funerals, or rumors and smear campaigns about their “abnormal” sexual practices led community members to launch spontaneous mob attacks on these groups. When trying to intervene, activists tended to get caught up in the violence or were targeted as accomplices who allegedly were promoting tabooed identities and sexual practices. A trans activist in Kenya shared a harrowing experience:

Last year, a gay porn movie leaked out. The actor in that film was a neighbor boy, we were good friends.… People got wind of it, saw it, and decided to take action: “These gay people rub it in our face”.… They followed the boy to his premises … and broke his legs. Then they marched up to my home, demanding that I should go out for them to deal with me. They threatened they would burn the house down if I did not come out, saying that “he is the one campaigning for gay rights and he is their mentor and protector.”

(B29)Similarly, activists working on incest or domestic violence are often violently assaulted and harassed by community and family members when they publicize cases. In contexts where effective state protection is lacking, the local and personalized character of communal threats leads to activists experiencing extreme forms of distrust and isolation, because they are forced to be suspicious of their own neighbors and their immediate surroundings. A woman activist in Kenya said, “I focus on sexually exploited children.… The perpetrator will have to face the court of law if I get them, and most of them don’t want that, so I am not safe.… I am always afraid because I don’t know when I can meet the perpetrator” (B6). In contrast, assaults and intimidation of activists focusing on land rights, corruption, or postconflict issues tend to be carried out predominantly by state security forces, such as the police or intelligence agencies or by militant or criminal groups acting as proxies for business interests or influential individuals. A woman activist in Colombia, who works for the rights of small farmers, reported how she was assaulted by the local administration: “They sent someone after me. They caught me off guard. They said to me ‘A bullet costs 2,000 pesos”’ (A10). This activist described how constant intimidatory phone calls worsened her permanent state of fear and anxiety:

It happened so often. They called from private numbers. They would speak to me as if through gritted teeth, calling me “guerrilla” and then hang up. Sometimes they would make the sounds of a shot being fired. I was being intimidated. I was terrified, troubled.

(A10)In this regard, a more sophisticated but highly effective form of repression is surveillance, which further contributes to feelings of constant exposure, insecurity, and anxiety. As Zald (Reference Zald1978, 91) discussed, surveillance compresses space, both physical and tactical, making people feel less able to act freely. Moreover, if highly visible, it contributes to “a perception that the probability of sanctions is increased,” which can lead to the moderation or disengagement of activists without the need for more direct threats and punishments. Across the three contexts, activists pointed to a perceptible shift in recent years from direct forms of repression to more covert tactics of surveillance (interceptions, wiretapping, and the like) that an Indonesian activist described as “psycho war” (C6) and a Colombian one as “psychological persecution” (A13). Similarly, an Indonesian participant observed, “I guess it is not possible for them to kill me as I am a journalist and I have networks. So, what they want is to destroy my concentration” (C5). These descriptions confirm a trend identified in the political violence literature indicating that both authoritarian and democratic regimes have become increasingly sophisticated in the use of psychologically oriented policing methods, which are not only less resource intensive but, because they often operate clandestinely, also prevent incidences of moral outrage associated with more indiscriminate and public forms of repression (Deng and O’Brien Reference Deng and O’Brien2013; Gillham, Edwards, and Noakes Reference Gillham, Edwards and Noakes2013). As a result of the growing relevance of social media for activism, platforms such as Facebook and Twitter have become effective channels through which repressive actors harass or monitor activists’ lives.

In this sense, soft forms of repression can have devastating consequences because they are not only terrorizing emotionally but are also very difficult to confront and manage. This is particularly true for stigmatization, a tactic that is subtler than direct violence or intimidation but has serious and damaging effects on activists’ lives and work, because it relies on widespread societal and political prejudices that are impossible to change in the immediate term. A male Colombian activist, for example, emphasized that this moral harm is particularly severe when propaganda messages and prejudices are amplified in the media, because “there is no means to combat it, no way of reaching the broadcasters to say it’s not true, that corrections should be made” (A11). Moreover, stigmatization erodes the self-esteem of activists and discredits them in the public eye and among their personal networks (Ferree Reference Ferree, Davenport, Johnston and Mueller2005), aggravating their sense of isolation and distrust because they come to believe that much of society sees the violence they experience as legitimate and expected.

Lastly, repression not only has major consequences for the physical and mental well-being of activists but can also have devastating effects on the functioning of entire activist communities. As a Colombian activist noted, constant exposure to repression results in distrust against state institutions and can have a corrosive effect on the solidarity of civil society networks, because “all organizations that are working in the promotion of rights for communities censor themselves in some way … you never know who is involved in an armed group. You never know who might be seeing you as the enemy” (A29). As expected, this distrust exceeds the boundaries of work and feeds back into the personal lives of activists, further increasing their emotion work.

The Ambivalent Role of Families and Communities

The final relational arena we bring attention to is the activists’ immediate social circles, such as family and friends, that are affected by their high-risk activism. Although it is quite evident that intimate ties are an invaluable source of support for human rights activists as much as for everybody else, activists’ personal relations merit a closer look, given that more than half of the interviewed HAAs related their anxiety and insecurities to explicit family pressures and concerns for their well-being.Footnote 8 For many participants, threats and intimidations directed against their families were the most damaging and troublesome, with those experiencing attacks against loved ones showing deep emotional trauma and enhanced insecurity. For example, a woman activist in Colombia described threats against her daughter in the following terms: “The only day when I felt like I couldn’t do it, when I couldn’t fight back, when I wanted to die—was when they threatened my daughter. This event marked me a lot” (A9). For many participants the knowledge that their activism exposed family and friends to potentially deadly risks constituted a paramount moral dilemma that was emotionally very draining, with one participant going as far as saying, “To do this work, you can’t have a family” (A5). Moreover, breakups of intimate relationships and forced separations were a very common experience of HAAs, who related them to the risks and burdens their activism imposes on partners. Often, for activists, these breakups constituted decisive turning points that made them question themselves and their convictions. Their insecurity also led to constricted social lives where normal everyday activities become increasingly difficult to maintain, because “you lose things like going out to drink and being in the street at night” (A1).

Because of their intimate association with activists, family and friends also have to cope with communal stigmatization, political antagonism, and a potential loss of status. An activist in Indonesia, concerned about his wife’s job tenure, shared, “I am not sure whether at some point her boss will sack her because of me” (C6). In severe cases, tensions about the detrimental consequences of activists’ work even led families to turn against them. This was more common among LGBTIQA+ activists, who tended to be the most severely stigmatized in terms of family rejection and isolation across the three countries in our sample. As a participant in Kenya described,

There was a time, when I came out and said that I want to defend the rights of LGBTIQA+, my family and friends threw me out in the street. It was a tough time…. When I started having sexual relationships, they disowned me…. My aunt supported me … but then she threw me out after she spoke to my dad, and he threatened her as well.

(B8)Although the exclusion experienced by LGBTIQA+ activists was by far the most pronounced, communal suspicion, if subtler, was equally present in other HAA narratives. In Colombia this often takes the form of political polarization; certain communities are generally suspicious of human rights activists because they are seen as “guerrilla-friendly,” leading some activists to hide their work given that, as a participant noted, they are “not sure how people will react” (A13). Political and even class stigmatization are equally recognizable in the narratives of a Kenyan activist, who shared, “In Kenya this is a problem. The HRD [human rights defender] is alone, is seen as elitist, anti-government, anti-establishment. Sometimes it is difficult for HRDs to feel that the community is in solidarity with the struggle that the HRD is engaging in” (B7). Because of activists’ experience of exclusion, their family and immediate local communities emerge as a crucial relational domain in which emotional burdens, contextual difficulties, and hard and soft strategies of repression intersect more explicitly; it is in this domain in which the ultimate consequences of emotional attrition manifest themselves, because personal ties are possibly one of the last reservoirs of coping resources from which activists can draw.

Adversities, Emotions, and Insecurities

In this final section, we take a closer look at the emotional experiences of HAAs, which were summarized in figure 2, unpacking how attritional dynamics manifest in their narratives and focusing on the mutual reinforcement of different emotions, mechanisms, and factors across the three arenas previously examined.

As shown, human rights activists in high-risk environments not only have to cope with forms of human suffering that “normal” people are rarely exposed to but also are frequent targets of repressive acts themselves. This constant exposure to threat pervades their private lives as much as their activist roles, so that activists feel they had “to learn to live with anxiety,” get used to living locked “behind a closed door” (A7), and cope with permanent feelings of insecurity. That permanence was described by a trans sex workers rights activist in Kenya as feeling constantly as if one were “walking on thin ice” (B29) or in the following terms by an Indonesian women’s rights activist: “Nothing can make me secure. Perhaps when I sleep, I can forget the threats and risks” (C3).

Thus, the insecurity that activists experience goes beyond a sudden fearful reaction to a specific danger or threat; instead, it consists of a constant state of anxiety, uncertainty, and unpredictability that permeates their daily existence. Whereas fear requires a triggering stimulus, anxiety can become a chronic condition where the individual is in a constant state of tension and is permanently vigilant for diffuse, future-oriented threats (Barlow Reference Barlow2002, 65–66). Moreover, given that fear and anxiety activate precautionary reasoning, once in a state of anxiety people tend to process information and form beliefs to confirm the cognitive-appraisal aspects of the emotion, meaning they will privilege information about risks and perceive “more” dangers, thereby exacerbating their emotion work (Petersen Reference Petersen2010). We see this in our respondents, some of whom acknowledge feeling constantly observed, targeted, or both; for example, an activist in Kenya described how after having been attacked and threatened several times, he started to “believe I am a permanent target of state excesses” (B4), whereas an activist in Indonesia reported, “I always feel I have been followed. Somebody seems to be around the corner watching me. Where can I go?” (C6). This constant state of alertness affects the way activists relate to their social environment and their ability to establish trust bonds beyond their immediate acquaintances.

For Niklas Luhmann (Reference Luhmann and Gambetta2000), distrust has a similar complexity-reducing function as trust, but whereas the latter reduces social complexity by assuming desirable conduct as normality, suspicion or mistrust reduces uncertainty through a general expectation of injurious action, which produces a constant state of alienation and generalized risk aversion. Several activists described how they developed both a general suspicion of everyone they did not know personally and a growing inability to “trust people,” because “after a while you go into a tense mode and you don’t realize that you are in very high alert all the time,” as an activist in Kenya noted (B15). Increasing levels of anxiety and suspicion lead activists to consciously reduce the circle of people or organizations they interact with in pursuit of greater security. An activist in Colombia explained how she preferred not to tell anyone in her neighborhood that she had been attacked by unknown persons: “The truth is that the people in my neighborhood don’t know what happened to me. You have to be careful with the people that live in your neighborhood. I don’t know who those people were— I don’t know who the attackers were or who sent them” (A16). Other activists described how they started to withdraw more and more from people around them, both because of suspicion and of concerns about putting their family in danger.

As a result of these dynamics, HAAs experience isolation and loneliness to a higher degree than other activists, leaving them with very few people they could turn to when in need. As Cacioppo and Hawkley (Reference Cacioppo and Hawkley2009) note, perceived social isolation is tantamount to feeling unsafe, which sets off implicit “hypervigilance” for additional potential threats in the environment, resulting in a self-reinforcing loop in which isolated individuals distance themselves even more to avoid “new” risks and disappointments. A woman activist in Kenya reckoned, “I have chosen to be socially awkward – you don’t walk up to me and start talking to me. I’m very conscious when I walk into meetings or to what meetings I’m being invited to” (B33), whereas a Colombian activist succinctly described her main security strategy as “isolating oneself; you can’t be threatened if there is nobody to threaten you” (A2). Consequently, HAAs feel a discomforting loss of control, as they are forced to adopt practices that, instead of ameliorating their emotional strain, make life and work even harder; for example, they avoid routine behaviors such as speaking in public, walking alone, going out, answering unknown phone calls, or even speaking casually with people, because “you don’t know who’s listening” (A27).

Moreover, HAAs show clear and consistent markers associated with stress and burnout, as indicated by their reported feelings of tiredness, saturation, inefficacy, and resignation, in addition to various physical symptoms that they associate with work pressures: as shown in figure 2, disease is a marker that has a very limited presence among activists with medium and low attrition levels. Although distressing situations happen to all types of activists, HAAs emphasized feeling severe emotional (and physical) exhaustion because of their constant worries and state of alertness. However, threats are just one of the environmental constraints that leave activists with reduced opportunities, choices, or alternatives. As discussed earlier, a major source of stress is the omnipresence of societal and political factors beyond their control that make their work objectives and moral commitments difficult to achieve; for example, “If there is impunity, nothing will ever change. Of course, nothing ever does happen, you just do what you have do to,” said an activist in Colombia (A4). This constant investment of time and energy without rewards exposes certain HAA activists to feelings of hopelessness and disenchantment and justifies cynical views about their jobs and lives. Moreover, the limited resources that activists possess to deal with the emotional impact of strenuous circumstances considerably restricts the options available to them, further aggravating their emotional and physical fatigue. For example, an activist in Indonesia, shared, “I don’t have anywhere to escape.… I feel like [I am] living in a cage’ (C6), whereas a participant in Colombia described in more detail how her lack of economic and organizational resources affected her mental health:

As I said before, I would love to give everything up and take a break. It’s urgent. But for this, we need resources, and they would have to come out of my pocket. There’s no organization that would fund a two-month break and get away from it all.… But if your head or your heart is full, that’s no good. Last year I had a crisis and was hospitalized for a couple of days and was on sedatives for the days. It’s incredible the anxiety, and there’s nothing to treat it with.

(A4)This statement points to the therapeutic function that partial forms of disengagement may play for activists with high (and medium) levels of emotional attrition. Indeed, although our data include only engaged activists, and none of our participants saw full disengagement as a feasible option (for different reasons), many admitted this meant sacrificing their emotional and physical well-being out of a feeling of deep sense of responsibility. In particular, as noted by Chen and Gorski (Reference Chen and Gorski2015), activists who have experienced injustices themselves due to their marginalized identities feel a deep obligation to continue their activism, despite the heavy emotional burden: “I don’t want to have to run away every time I encounter homophobia. Where would that leave my dignity and my integrity? But the truth is that this has destroyed my life,” expressed one activist (A2). Despite these expressions of stoicism, more than 16% of HAAs participants explicitly stated they had considered quitting, 33% had relocated (abroad or internally), and more than 54% actually stopped working for short periods of time or moderated their activities, either because of security concerns or sickness, or because they felt the emotional strain was too high.Footnote 9 Partial forms of disengagement that are more or less voluntary emerge then as a form of intermediate coping, insofar as they allow activists to alleviate some of their emotional symptoms while continuing their activist tasks.

In any case, our analysis makes clear that HAAs could hardly be said to be working well, not only because of the level of exhaustion, insecurity, distrust, and isolation they experience but also because of the constant but profound deprivations and miseries that they need to handle and ultimately accept. The burdens are sadly reflected in how one interviewee described her aspirations for normality: “being able to walk down the street holding my son’s hand and not being afraid, … the ability to sit in a park and enjoy my life; to share my life” (A11). This lingering state of feeling, working, and living in a restricted way, with fear and worry, requires a constant and very intense level of emotion work that some people simply cannot master and that leaves them with very few alternatives between resignation and exit. This points to a central issue at play in the process of emotional attrition—the role of emotions in the functioning of repression and the process of demobilization—and invites a more careful consideration of the interplay between adversity, repression, and the routine problems and risks that confronts activists who are embedded in high-risk environments.

Conclusion

By conceiving emotion work as integral to a wider process of emotional attrition, this article puts emphasis on the relational and temporal effect that composite emotional responses—involving a multiplicity of emotional symptoms, “feeling states,” and social behaviors—can play in the regulation of contentious politics and political activism. Therefore, we argue that this regulation extends beyond political opportunity structures and patterns of repression to involve the nested system of social, political, and economic relations that activists, protesters, and social movement actors inhabit, as well as the experiences of vulnerability that emerge from their specific locations within these systems and arenas.

In terms of repression, our study not only indicates the major emotional consequences of repressive tactics but also suggests that opponents seem to bank on emotional attrition for their efficacy, even using it strategically (Petersen Reference Petersen2011, 34), as the overall prevalence of anxiety-generating tactics such as intimidation seems to indicate. Moreover, because repressive actors and activists often inhabit the same sociopolitical milieus, our evidence points to a certain (a)moral economy of repression, where opponents calibrate their actions to amplify activists’ contextual stressors and emotional frailties. Given this context, our argument questions the extent to which certain repression tactics should indeed be considered as “soft,” given the emotional and psychological damage that ambiguous, obscure, and open-ended tactics and threats can produce, particularly in contexts marked by “diffuse anxieties” caused by political violence, high crime, impunity, or poverty. From this perspective, emotional attrition emerges as a complementary explanation to the deterring effect of dispiriting environments, as observed by Pearlman (Reference Pearlman2013, 400) and Young (Reference Young2019) in countries where disenchantment and pervasive fear create an “emotional climate” that increases ‘aversion to risk, and hence a tendency toward resignation rather than resistance,” as coercive measures become less necessary than practices aimed at confirming people’s negative appraisals and disengaged attitudes. Simultaneously, we recommend a reconsideration of the socio-institutional variables characterizing a “deterring” state or regime, such as in countries like Brazil and Colombia, which score relatively well in Freedom House’s Global Freedom ranking (74 and 65, respectively, against 83 for the United States and 20 for Russia), but are among the world’s most dangerous places for human rights activists (FLD 2020).

Interestingly, and although not directly explored in the text, our data suggest that people exposed to similar levels of severe repression can show very different levels of emotional attrition: for example, a prominent political prisoners’ lawyer in Colombia, who said he had been living “in a threatening climate of permanent fear since 1985” (A3) and had to take his family into exile several times, showed few markers of emotional exhaustion and attrition. This could be because repression’s emotional effects work “better” when complemented with extant vulnerabilities in activists’ lives, such as poverty, institutional isolation, family responsibilities, or serious discrimination. This hypothesis finds initial support in our data; high emotional attrition appears to be more prevalent among activists working alone or in small charities or who are dealing with heavily marginalized groups— 60% of activists working on LGBTIQA+ issues and 50% of those working with sex workers and political prisoners show high-attrition markers. At the same time, women activists showed more high-attrition markers than men (21% vs. 13% of each group’s total number), pointing again to the gendered operation of stressors.

Our findings also point to relevant aspects regarding the paradoxical impact that group dynamics and social identities can have on emotional exhaustion and disengagement. Although psychological and sociological studies have consistently demonstrated that shared social identities and thick social ties mitigate stress and provide important coping resources, our analysis underlines that high group identification can also contribute to sentiments of moral failure and lack of accomplishment, which increase stress and emotion work. Just as organizations can exploit the commitment of high group identifiers (Haslam Reference Haslam2004, 191), the strong identities and heightened sensitivities of committed activists can be a major cause of emotional strain, which can be targeted by repressive actors and opponents. As this occurs, high-risk activists confront a dilemma: they need to choose between privileging their commitment to oppressed groups or compromising the well-being of their family and closed ones. Moreover, when emotional attrition is considered, neither adversity nor repression ceases when activists return to the privacy of their homes, because their personal, community, and overall life context can very much contribute to increasing the emotional load of external challenges and dangers. Similarly, we observed a certain moral hazard in HAAs and MAAs with strong group identities—mainly indigenous and rural activists but also LGBTIQA+ ones—with emotional attrition incentivizing withdrawal into in-group securities and eroding their willingness to collaborate with “strangers” or to travel beyond “safe” territories; this withdrawal potentially narrows the space for collaboration and civic engagement and complicates the application of protection schemes. These negative externalities of coping and the pursuit of security require further investigation.

Finally, the notion of emotional attrition also points to intriguing new insights into how processes of demobilization and exiting work. As mentioned, although our sample does not allow us to examine the experiences of demobilized activists, we have evidence that HAAs engage in forms of partial disengagement: they admit taking time off, assuming less committed tasks, or working in highly demotivated moods. The extent to which this partial state of disengagement is transitory, providing activists with time and space to recover their emotional balance, or is conducive to more permanent forms of demobilization is something we cannot directly assess here and that needs further research. Recent findings in the clinical literature, however, indicate that partial disengagement may depend on the intensity of emotional exhaustion, noting that severe burnout symptoms are predictors of involuntary absenteeism and result in longer “sickness” absences, whereas milder symptoms, like demotivation, lead to more voluntary forms of absenteeism (Schaufeli, Bakker, and Van Rhenen Reference Schaufeli, Bakker and Van Rhenen2009). While reminding the reader that our sample is not representative, we observe that high attrition seems more common among activists with limited experience and that it decreases with seniority: 50% of HAAs had less than 5 years in activist work, a proportion falling to 21% and 12%, respectively, in those with 5–10 and more than 10 years of experience. This observation opens interesting questions about the relationship between attrition, adaptation, and disengagement: Do HAAs ultimately adapt and get better in time, becoming LAAs? Do they “maladapt,” becoming emotionally numbed and developing subtler emotional pathologies, as observed with some postconflict survivors? Or alternatively, do younger HAAs defect earlier on, leaving at work only the battle-hardened seniors? Answering these questions requires further empirical analysis to trace distinct trajectories of disengagement and demobilization and to evaluate their relationship to a wider set of emotional responses and states.