In May 2018 Camacho et al published a randomised controlled trial in this journal, the latest in a long line of studies establishing the long-term clinical and cost-effectiveness of collaborative care for people with physical–mental comorbidity.Reference Camacho, Davies, Hann, Small, Bower and Chew-Graham1 The study was a 24-month follow-up of a larger trial (COINCIDE) that had already demonstrated the short-term (4 months) clinical effectiveness of collaborative care. Yet despite the evidence, the intervention: ‘collaborative care’ has still not been widely adopted. We reflect on some of the reasons why that may be and how uptake can be facilitated given the clear policy laid out in the National Health Service (NHS) Long-Term Plan to pursue ‘new and integrated models of primary and community mental health care’ that can help improve the physical health of people with mental illness and vice versa.

What is it?

Collaborative care is a systematised way of managing care and treatment for people with chronic conditions. Based on a broader conceptual model for the longitudinal care of common chronic conditions, collaborative care espouses four key components:Reference Wagner, Austin and Von Korff2

(a) a multiprofessional approach to patient care;

(b) a structured management plan tailored to the individual needs of the patient;

(c) proactive follow-up delivering evidence-based treatments;

(d) processes to enhance interprofessional communication such as routine and regular team meetings and/or shared records.

The approach was operationalised in America in the 1990s as the ‘collaborative care model’ to facilitate multidisciplinary working between a triad of physicians, psychiatrists and clinical care coordinators.Reference Katon, Von Korff, Lin, Walker, Simon and Bush3 Variations exist in the structure and composition of teams, the range of evidence-based treatments offered and the nature of follow-up (for example telephone or in person) but there are five core elements of the collaborative care model.

(a) Patient-centred team care – care is patient-centred and provided by proactive teams using shared care plans that incorporate patient goals.

(b) Population-based care – patient populations targeted for collaborative care are defined in advance; then screened, stratified, tracked and closely followed for concordance and response to treatment.

(c) Measurement-based treatment to target – care is measured with standard tools and follows a stepped-care approach.

(d) Evidence-based care – treatments offered are based on clinical guidelines supported by reliable evidence of effectiveness and integrated into daily practice.

(e) Accountable care – providers can be held accountable for costs and quality outcomes.

Initially designed to improve depressive symptoms in primary care, the approach has been extended to a wide range of target populations and settings. Over the past two decades effectiveness of collaborative care has been established in settings outside primary care including in-patients, across a wide range of physical conditions and in the UK health system. A Cochrane review concluded 5 years ago that ‘collaborative care is associated with significant improvement in depression and anxiety outcomes compared with usual care and represents a useful addition to clinical pathways for adult patients with depression and anxiety’.Reference Archer, Bower and Gilbody4 In essence if collaborative care had been a drug, it would have been marketed decades ago and yet it has not been implemented out of well-resourced or academic centres.

Why is it difficult to implement?

In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends collaborative care for people with moderate-severe depression and physical illness, but it is not yet part of routine clinical practice. Collaborative care is a complex intervention as defined by the Medical Research Council, in that it comprises multiple interacting components that require behavioural change across different organisational levels. A well-conducted systematic review of 17 qualitative studies that explored how collaborative care is adopted identified a number of factors that act as barriers to implementation.Reference Overbeck, Davidsen and Kousgaard5

Coherence

With so many moving parts, those delivering collaborative care often struggle to fully understand the approach and its associated elements. Sometimes there were conflicting ideas among members of the multidisciplinary team as to what was involved and clinicians were often taken aback by the changes required.

Active participation

Successful implementation hinges on successfully engaging the clinicians delivering the approach; when there is a lack of intrinsic motivation or scepticism of the intervention it was difficult to deliver.

Skills and training

Professional and social skills of the clinicians delivering collaborative care, particularly of the care coordinator were important in bringing about positive outcomes, and where these were lacking, training was required to upskill members of the multidisciplinary triad. This training was not always provided by those championing the model.

Time and workload

Time was considered the most important resource needed to implement the model. Hard-pressed clinicians sometimes struggled to find the time necessary for the enhanced communication required.

These barriers exert varying effects according to the patient population for which collaborative care is applied and the health setting in which it is implemented. For example patient–clinician interactions are very important for people with serious mental illness such as psychotic disorders in which collaborative care is more likely to be successful when the physician is receptive to new working practices, the care coordinator engages with the patient proactively and the psychiatrist adopts a recovery-focused approach. In contrast, the organisational complexity of adopting collaborative care across numerous different providers represents the most significant barrier in primary care settings.

Well-conducted qualitative studies have shown the difficulties general practitioners face in providing holistic care to people with mental and physical comorbidity. To embed collaborative care into real-world settings, the system-level barriers and day-to-day realities facing primary care need to be appreciated.

In all settings, professional perception that mental and physical health as distinct entities are deeply ingrained and there can be attempts to normalise mental distress in the context of long-term physical health conditions when the model solutions offered are not locally relevant or are considered too complex to be implemented wholesale.

How can adoption be facilitated?

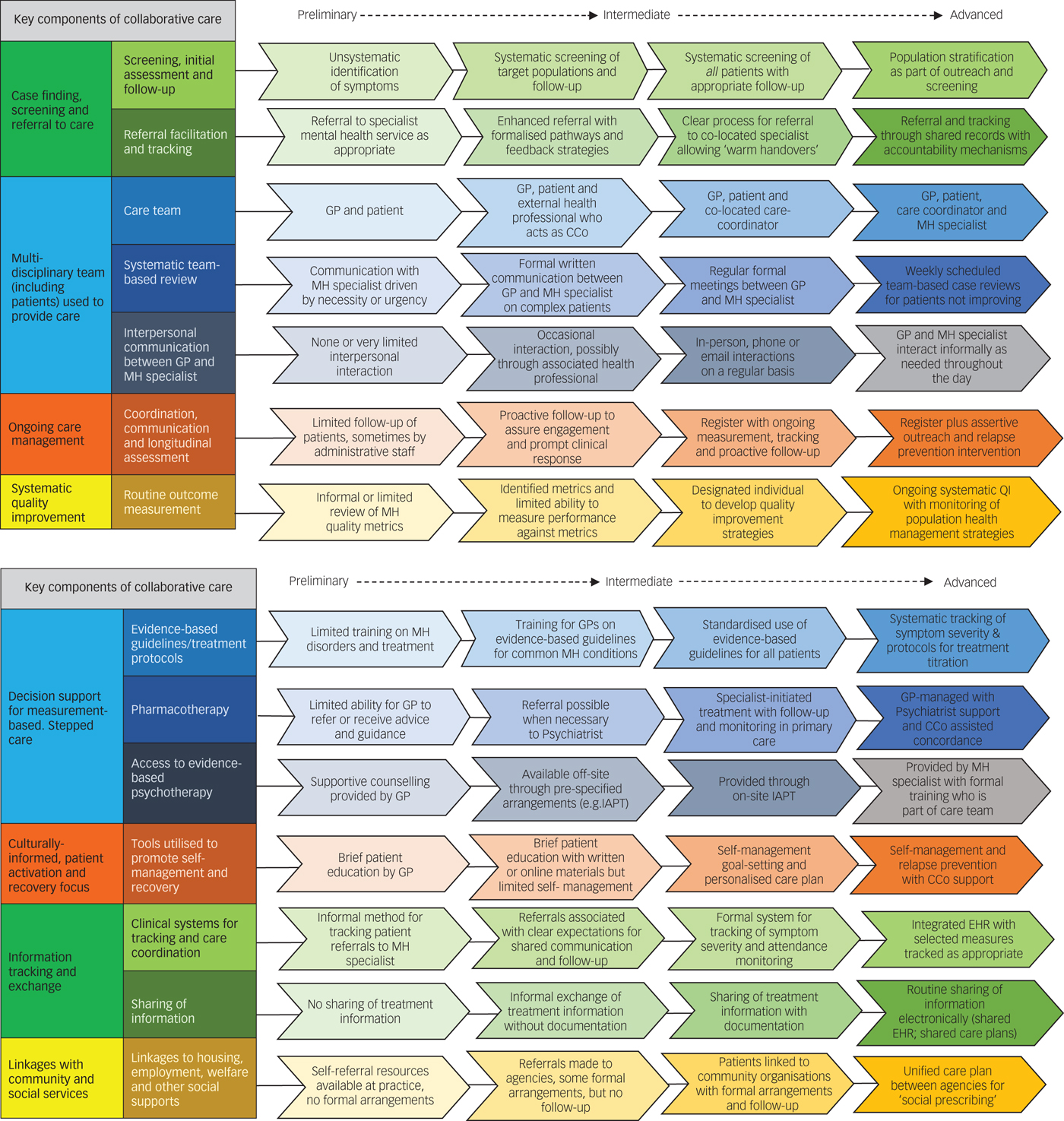

Evidence suggests that the more intense, integrated and systematic the collaborative care approach, the larger the effect size. However, this is difficult to deliver in a system that relies on several structural, procedural, internal and contextual factors working together to facilitate implementation. The old notion of collaboration between mental and physical healthcare moving along a single continuum from minimal to full integration is a fallacy. Rather the component parts of collaborative care (multidisciplinary working, use of routine outcome measurement, clinical care coordination, and so on) advance along several parallel pathways at different rates depending on the capabilities and the contextual factors acting on the delivery system trying to adopt the approach.

Taking this concept further, a group in New York including one of the authors (H.A.P.) has developed a continuum-based framework to provide guidance on the steps that primary care practices, particularly smaller and medium-sized practices can take to advance towards more effective collaborative care.Reference Chung, Rostanski, Glassberg and Pincus6 The framework uses a maturity matrix structure in which the core components of collaborative care are listed on the y-axis:

(a) case finding, screening, and referral to care;

(b) use of a multidisciplinary professional team – including patients – to provide care;

(c) ongoing care management;

(d) systematic quality improvement;

(e) decision support for measurement-based, stepped care;

(f) culturally adapted self-management support;

(g) information tracking and exchange among providers;

(h) linkages with community/Social Services;

and the steps needed to advance towards more effective integration for each of these components (from pre-implementation to early to intermediate and advanced integration) are articulated on the x-axis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 A continuum framework for collaborative care in primary care settings.

The framework helps address many of the challenges to implementation of collaborative care raised in the literature. It shows that benefits could be realised even at early or intermediate stages of implementation. Practices are guided to identify their own strengths and areas in need of development and so the framework helps anchor implementation in local context. As such it provides one elegant solution to the problem of adoption.

We have adapted the wording of the framework to a more NHS-specific context and this could serve as a good starting point to develop similar guidance for the NHS. At present, the framework, developed in America, has a particular focus on the identification of people with mental illness and on increasing their access to care. Although such factors would be useful in the NHS, we in the UK have a greater degree of baseline collaboration between primary and secondary care and a more robust system of community support and so we require a different set of implementation and improvement methods (for example streamlining referral pathways and ensuring best practice). Hence the framework requires adaptation and validation for a different public sector and healthcare system. It also requires attention to external factors to support and motivate organisational change such as learning platforms and technical assistance, care management and health information technology infrastructure, mechanisms and measures to assure shared accountability across general practitioners and mental health specialists, and financial and non-financial incentives. We would argue that such work has been given greater impetus by the NHS Long Term Plan, which requires clinicians, working collaboratively with their patients, to turn the policy of holistic care delivery into daily reality.

Despite our differences, one thing that remains clear both for America and the UK, is that the question when it comes to collaborative care needs to shift from the ‘what and the why should we do it’ to ‘how do we go about making this the routine care that people with co-occurring mental and physical disorders receive?’

Funding

H.A.P. was supported in this work by a grant from The Commonwealth Fund of New York. The views expressed here are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Commonwealth Fund.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Commonwealth Fund, the BMJ group, Professor Norquist (Emory University) and Professor Unützer (University of Washington), conversations with whom has shaped much of our thinking on the collaborative care model. We would also like to thank Dr Henry Chung at the Montefiore Medical Center, New York who led the development of the continuum-based framework. Finally, we would like to acknowledge the late Professor Wayne Katon who firmly established collaborative care as a viable method for improving patient care.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.