Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) is characterised by severe recurrent temper outbursts in the context of persistent irritable mood. This disorder has been introduced in DSM-5 1 as a new diagnostic category to address concerns about the overdiagnosis of bipolar disorder in children. Reference Birmaher and Axelson2–Reference Carlson6 However, the possibility that DMDD may represent an early manifestation of liability to bipolar disorder remains a topic of debate. Reference Fristad, Wolfson, Algorta, Youngstrom, Arnold and Birmaher7,Reference Mitchell, Timmins, Collins, Scavone, Iskric and Goldstein8 DMDD is typically diagnosed in school-aged children. The prevalence of DMDD is uncertain since its estimates rely on proxy criteria adapted from diagnostic interviews not designed to assess DMDD and range from 0.12 to 3.3%. Reference Althoff, Crehan, He, Burstein, Hudziak and Merikangas9,Reference Copeland, Angold, Costello and Egger10 As DMDD is a relatively new diagnosis, there are no published prospective studies on its association with psychiatric disorders in adulthood. However, longitudinal data are available on closely related earlier concepts, including severe mood dysregulation and chronic irritability. These data suggest that DMDD-related constructs are on a developmental continuum with major depressive disorder rather than with bipolar disorder. Severe mood dysregulation and chronic irritability (a core DMDD symptom) often precedes major depressive disorder, Reference Brotman, Schmajuk, Rich, Dickstein, Guyer and Costello11 but rarely converts to bipolar disorder. Reference Stringaris, Cohen, Pine and Leibenluft12–Reference Copeland, Shanahan, Egger, Angold and Costello14 Evidence from genetic studies provides support for longitudinal association between depression and irritability. A recent meta-analysis reveals that irritability is moderately heritable, and its overlap with depression is explained mainly by genetic factors. Reference Vidal-Ribas, Brotman, Valdivieso, Leibenluft and Stringaris15 Twin studies have shown that adolescent irritability has a significant phenotypic relationship with depression Reference Stringaris, Zavos, Leibenluft, Maughan and Eley16 and that irritability strongly predicts anxiety and depression in late childhood and early adolescence. Reference Savage, Verhulst, Copeland, Althoff, Lichtenstein and Roberson-Nay17 There is also a strong association between irritability, emotional disorders in the child and history of depression and suicidality in the mother. Reference Krieger, Polanczyk, Goodman, Rohde, Graeff-Martins and Salum18 Children with severe irritability trajectories are more likely to have mothers with recurrent depression. Reference Wiggins, Mitchell, Stringaris and Leibenluft19 Childhood irritability may mediate the link between prenatal maternal depressive symptoms and adolescent depression. Reference Whelan, Leibenluft, Stringaris and Barker20 On the contrary, parental bipolar disorder is uncommon in parents of youth with severe mood dysregulation and clustering in families suggests that familial disposition to bipolar disorder is largely distinct from that for irritability. Reference Brotman, Kassem, Reising, Guyer, Dickstein and Rich21 However, there are few data on the familial transmission of DMDD.

In the absence of long-term follow-up of individuals diagnosed with DMDD, family studies can provide insight into the aetiological relationships between DMDD and other mood disorders. Specifically, if the causal factors for DMDD overlap with those for bipolar disorder or major depressive disorder, DMDD would be expected to be overrepresented in the offspring of parents with that disorder. However, there are few data on DMDD in offspring of parents with mood disorders and the available information appears contradictory. Although population-based studies suggested that chronic irritability in children is associated with depression and anxiety in parents, Reference Wiggins, Mitchell, Stringaris and Leibenluft19,Reference Whelan, Leibenluft, Stringaris and Barker20,Reference Dougherty, Smith, Bufferd, Stringaris, Leibenluft and Carlson22 a family high-risk study reported that offspring of parents with bipolar disorder are more likely to meet criteria for DMDD (6.7% v. 0.8%) and have higher rates of chronic irritability than community controls. Reference Sparks, Axelson, Yu, Ha, Ballester and Diler23 However, the latter study has two major limitations. First, DMDD was not diagnosed according to the DSM-5 criteria, instead the diagnoses were approximated based on a DSM-IV diagnostic instrument. Second, since the study only included offspring of parents with bipolar disorder and control offspring of healthy parents, it did not allow distinguishing a specific familial association between bipolar disorder and DMDD from a general association with any mood disorder. Thus, although the results of the family high-risk study may appear to be at odds with prior longitudinal data, the discrepancies may be accounted for by differences in concepts and methodology. To resolve the apparent discrepancy, we aimed to examine the specificity of familial association between DMDD and major mood disorders in offspring of parents with bipolar disorder, offspring of parents with major depressive disorder and comparison offspring, assessed with a DSM-5 diagnostic instrument.

Method

Participants

The participants were youth aged 6–18 years who were assessed for DMDD while taking part in the Families Overcoming Risks Building Opportunities for Wellbeing (FORBOW) project. Reference Uher, Cumby, MacKenzie, Morash-Conway, Glover and Aylott24 Offspring of parents with bipolar disorder and offspring of parents with major depressive disorder were enrolled through affected parents receiving in-patient and out-patient psychiatric services in Nova Scotia, Canada, where clinicians systematically enquire whether patients with major mood and psychotic disorders have biological children in the eligible age range. Participants were enrolled irrespective of whether any psychopathology was present in the offspring. Comparison offspring of parents without major mood disorders were enrolled through schools serving the geographic areas from which high-risk offspring were recruited. Inclusion criteria were availability of at least one biological parent for assessment and age 6–18 years, the recommended age range for DMDD diagnosis. Exclusion criteria were brain injury or severe intellectual disability of a degree that would preclude valid assessment. The study protocol was approved by the Nova Scotia Health Authority Research Ethics Board. All participants with capacity provided written informed consent. For children who did not have the capacity to make a fully informed decision about participating, a parent or guardian provided a written informed consent and the child gave an assent.

Parent assessments

Parents and children were assessed by separate teams of assessors. We established parent DSM-IV and DSM-5 diagnoses with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS) Reference Endicott and Spitzer25 and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders (SCID), Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams26 followed by clinical consensus with a psychiatrist masked to child psychopathology. Participants provided consent to access their medical notes and relevant information extracted from the notes was presented at the consensus meeting alongside the results of the semi-structured interviews. In the majority of cases, the parent diagnoses were supported by long-term follow-up and confirmed by collateral information obtained from the relatives and available medical records. The diagnosis of major depressive disorder is never final since it can convert to bipolar disorder at any time. Reference Angst, Sellaro, Stassen and Gamma27 However, given the age of the parents, the combination of diagnostic interviews and clinical notes permits reliable distinction between bipolar disorder and unipolar major depressive disorder. To establish reliability, we completed a second diagnostic interview with a different interviewer who was masked to results of the prior interview with a subset of 25 parents, including 6 with bipolar disorder and 11 with major depressive disorder. In this reliability sample, we have seen perfect agreement on the diagnosis of bipolar disorder (kappa (κ) = 1.00) and good agreement on the presence v. absence of major depressive disorder (κ = 0.76).

Youth assessments

Youth assessors masked to the referral source and parent diagnosis interviewed the youth participants and their parents or other caregivers with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Aged Children for DSM-5, Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL). Reference Kaufman, Birmaher, Axelson, Perepletchikova, Brent and Ryan28 The DMDD module of the K-SADS-PL was administered to all participants in full. This module establishes the presence of each symptom of DMDD, including frequent (three or more times per week) severe temper outbursts inconsistent with developmental level, persistent irritability and onset before the age of 10 years. Each symptom is rated as 1, absent; 2, present at subthreshold level; or 3, present at threshold level. Lifetime diagnosis of DMDD and other mental and behavioural disorders was then established in consensus meetings with licensed child and adolescent psychiatrists presented with all available information on offspring but masked to information on parents. The diagnoses were recorded without hierarchy, so that if a participant met diagnostic criteria for DMDD and for oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), both diagnoses were recorded. We measured socioeconomic class as a sum of five binary indicators: mother's education greater than high school, father's education greater than high school, family income $40 000 or more, ownership of family residence, ratio of bedrooms to household member one or higher.

Data analysis

After data quality control, we examined the relationship between parent diagnosis (bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, no mood disorder) and three dichotomous outcomes in offspring: frequent temper outbursts, persistent irritability and lifetime DMDD diagnosis. Because of zero prevalence rates in one or more groups, logistic regression was not applicable. Therefore, we examined the relationship between parent diagnosis and offspring outcomes using a bootstrap version of the chi-squared test (χ2), which has been shown to be more accurate than standard χ2 or Fisher's exact test and provide adequate type I error rates across the full range of outcome frequency. Reference Lin, Chang and Pal29 For each test, the contingency table is resampled (with replacement) 10 000 times to obtain a distribution of χ2 estimates and a corresponding non-parametric P-value. Results with P = 0.05, two tailed, are reported as significant. Analyses were carried out in Stata 14.

Results

Participants

Between October 2013 and May 2016, we completed the K-SADS and the DMDD module with 180 participants (85 males and 95 females) aged 6–18 years (mean age 11.6 years, s.d. = 3.5), including 82 offspring of parents with major depressive disorder, 58 offspring of parents with bipolar disorder and 40 comparison offspring of parents with no mood disorder. The youth included in this sample had high rates of psychopathology, including consensus-confirmed lifetime diagnoses of multiple externalising and internalising disorders (Table 1).

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics by parent diagnosis

| Parent diagnosis | No mood disorder (n = 40) |

Bipolar disorder (n = 58) |

Major depressive disorder (n = 82) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at assessment, mean (s.d.) | 11.35 (3.02) | 12.25 (3.60) | 11.29 (3.69) |

| Socioeconomic status (range 0–5), mean (s.d.) | 3.10 (1.28) | 3.02 (1.26) | 2.76 (1.46) |

| Gender, female: n (%) | 17 (42.5) | 44 (53.7) | 34 (58.6) |

| Ethnicity, White: n (%) | 35 (87.5) | 54 (93.1) | 71 (86.6) |

| Living with both biological parents, n (%) | 23 (57.5) | 36 (62.1) | 47 (57.3) |

| Lifetime diagnoses, a n (%) | |||

| Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder | 3 (7.5) | 19 (32.8) | 22 (26.8) |

| Oppositional defiant disorder a | 2 (5.0) | 7 (12.1) | 7 (8.5) |

| Conduct disorder | 0(0) | 2 (3.4) | 2 (2.4) |

| Depression | 1 (2.5) | 15 (25.9) | 13 (15.9) |

| Anxiety | 13 (32.5) | 33 (56.9) | 28 (34.1) |

| Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (7.3) |

| Any diagnosis | 14 (35.0) | 34 (58.6) | 40 (48.8) |

Depression, includes lifetime diagnosis of major depressive disorder or persistent depressive disorder; anxiety, includes lifetime diagnosis of generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, agoraphobia or other anxiety disorder.

a. All diagnoses were lifetime and established without hierarchies. Therefore, diagnosis of oppositional defiant disorder is recorded if symptomatic criteria were met at any time, even if the disruptive mood dysregulation disorder diagnosis is present.

DMDD symptoms

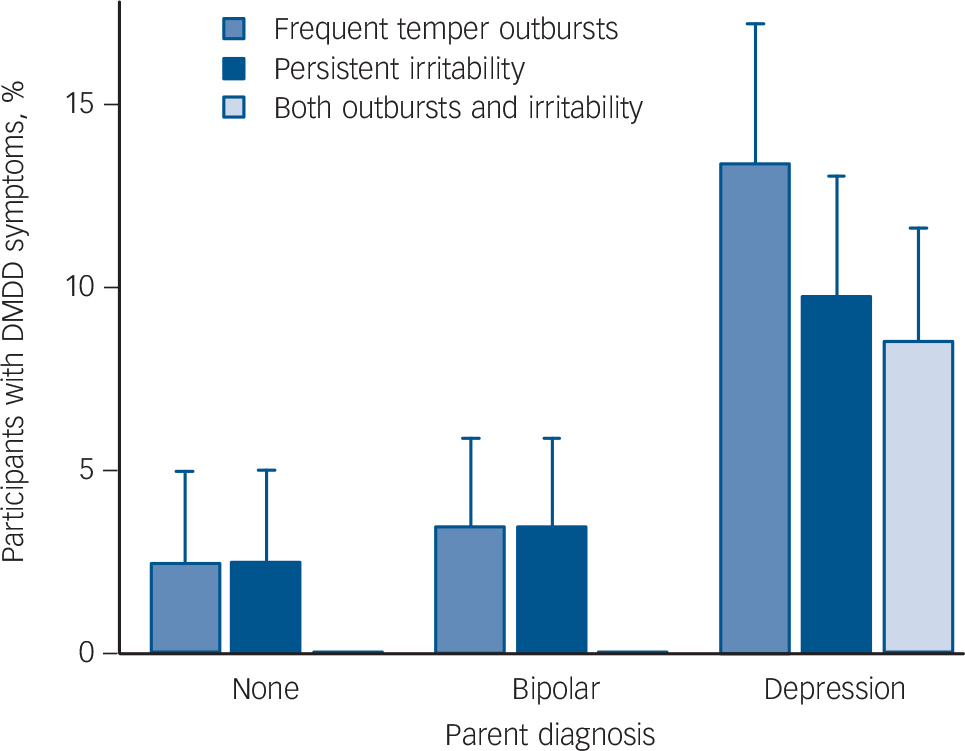

DMDD symptoms including frequent temper outbursts and persistent irritability were most common among offspring of parents with major depressive disorder (Fig. 1). Frequent temper outbursts were present in 2 (3.4%) of the 58 offspring of parents with bipolar disorder, 11 (13.4%) of the 82 offspring of parents with depression and 1 (2.5%) of the 40 comparison offspring. Frequent temper outbursts were significantly associated with family history across the three groups (χ2 bootstrap(2) = 6.70, P = 0.035) and were more common in offspring of parents with major depressive disorder than in offspring of parents with bipolar disorder (χ2 bootstrap(1) = 4.01, P = 0.045). Persistent irritability was present in 2 (3.4%) of the 58 offspring of parents with bipolar disorder, 8 (9.8%) of the 82 offspring of parents with depression and 1 (2.5%) of the 40 comparison offspring. Persistent irritability did not significantly vary with family history (χ2 bootstrap (2) = 3.52, P = 0.172). Only seven participants, all sons and daughters of parents with major depressive disorder, had both frequent temper outbursts and persistent irritability (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Prevalence of symptoms of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) in offspring of parents with bipolar disorder, parents with depression and a control group of parents with no mood disorders.

The height of each bar indicates the number of participants with symptoms above the clinical threshold level. Error bars indicate a standard error of the proportion.

DMDD diagnosis

Of the 180 participants only 6 (3.3%) met the diagnostic criteria for DMDD. All six participants with DMDD were offspring of parents with major depressive disorder (Table 2). In all six, the mother was affected with major depressive disorder. In one, both mother and father were affected with major depressive disorder. In all six participants, the youth also fulfilled criteria for other externalising and/or internalising disorders, including attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), ODD, conduct disorders, major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders (Table 2). One additional participant, also the offspring of a mother with major depressive disorder, fulfilled the symptomatic criteria A–E, but did not receive the diagnosis of DMDD because symptoms were not consistently present in multiple settings and, therefore, criterion F was not met. The diagnosis of DMDD varied significantly by family history (χ2 bootstrap(2) = 7.42, P = 0.025) and was significantly more common in offspring of parents with major depressive disorder than in offspring of parents with bipolar disorder (χ2 bootstrap (1) = 4.43, P = 0.035). None of the 58 offspring of parents with bipolar disorder fulfilled criteria for DMDD and none had a combination of frequent anger outbursts and persistent irritability (Fig. 1).

Table 2 Participants with a disruptive mood dysregulation disorder diagnosis

| Parents' primary diagnoses | Offspring | Other lifetime diagnoses in offspring a | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother | Father | Age | Gender | Medication | Drug use | ADHD | ODDa | Conduct | Depression | Anxiety |

| Depression | Anxiety | 6.2 | Male | None | None | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Depression | None | 7.3 | Male | None | None | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Depression | Depression | 8.1 | Female | None | None | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Depression | None | 12.0 | Male | None | None | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Depression | Not assessed | 14.0 | Male | None | None | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Depression | Substance use | 15.6 | Female | None | Cannabis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; ODD, oppositional defiant disorder; Conduct, conduct disorder; Depression, lifetime diagnosis of major depressive disorder or persistent depressive disorder; Anxiety, lifetime diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, agoraphobia or other anxiety disorder.

a. All diagnoses were lifetime and established without hierarchies. Therefore, diagnosis of ODD is recorded if symptomatic criteria were met at any time, even if the DMDD diagnosis is present.

Discussion

Main findings

This is the first study to apply a dedicated diagnostic instrument to study DMDD in youth at high risk for mood disorders and it suggests that DMDD diagnosis is uncommon. Although there were high rates of psychopathology in the present sample, only 6 of 180 participants (3.3%) met DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for DMDD. With all six occurring among offspring of parents with major depressive disorder and none in offspring of parents with bipolar disorder, our results do not support a specific association between DMDD and family history of bipolar disorder.

The diagnosis DMDD has only recently been introduced 1 and estimates of its prevalence in the general population Reference Althoff, Crehan, He, Burstein, Hudziak and Merikangas9,Reference Copeland, Angold, Costello and Egger10 or in high-risk youth Reference Sparks, Axelson, Yu, Ha, Ballester and Diler23 depend on proxies extrapolated from diagnostic questions that were designed to diagnose other disorders. We present the results of the first study that used a diagnostic instrument that was designed to assess DMDD. Our finding that the DMDD diagnosis is uncommon even in a sample of youth at high risk for psychopathology is consistent with the more conservative proxy estimates of DMDD prevalence rates. Reference Althoff, Crehan, He, Burstein, Hudziak and Merikangas9,Reference Copeland, Angold, Costello and Egger10 In addition, the finding that all individuals with DMDD also met diagnostic criteria for one or more other mental disorders suggests that the introduction of DMDD will not lead to more youth being diagnosed.

Comparison with findings from other studies

One of the major issues of debate has been the relationship between DMDD and bipolar disorder. Reference Leibenluft3,Reference Roy, Lopes and Klein4,Reference Carlson6 Longitudinal studies have reported developmental continuity between DMDD proxies and depression, but not bipolar disorder. Reference Stringaris, Cohen, Pine and Leibenluft12–Reference Copeland, Shanahan, Egger, Angold and Costello14,Reference Krieger, Polanczyk, Goodman, Rohde, Graeff-Martins and Salum18 In contrast, a family high-risk study reported high rates of DMDD among offspring of parents with bipolar disorder, established based on an extrapolation of questions designed to assess ODD. Reference Sparks, Axelson, Yu, Ha, Ballester and Diler23 Since the existing studies used varying proxy concepts of DMDD diagnosis and no previous study used an instrument designed to assess DMDD, the discrepancies may be a result of either different study design or different concepts and assessments.

The present study has sought to resolve the discrepant findings by applying a diagnostic instrument designed to assess DMDD in offspring of parents with bipolar disorder and adding a comparison with offspring of parents with major depressive disorder. Our result that DMDD is associated with family history of major depressive disorder but not bipolar disorder is consistent with prior population-based studies. Reference Stringaris, Cohen, Pine and Leibenluft12–Reference Copeland, Shanahan, Egger, Angold and Costello14,Reference Wiggins, Mitchell, Stringaris and Leibenluft19,Reference Whelan, Leibenluft, Stringaris and Barker20,Reference Dougherty, Smith, Bufferd, Stringaris, Leibenluft and Carlson22 Our findings are in disagreement with a prior familial high-risk study. Reference Sparks, Axelson, Yu, Ha, Ballester and Diler23 In spite of high rates of both externalising and internalising psychopathology, the symptoms of frequent temper outbursts and chronic irritability were not particularly elevated and there was no diagnosis of DMDD among the offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. The difference between the present findings and those of Sparks and colleagues suggests that the divergence of results is unlikely to be the result of chance alone. One plausible explanation for the difference is the use of questions designed to diagnose ODD. The definition of symptoms and the frequency and persistency requirements differ substantially between DMDD and ODD. We found an elevated rate of ODD and more morbidity overall but not DMDD among offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. This finding is consistent with evidence for the association between severe irritability in youth and familial liability to depression reported in the literature. Reference Krieger, Polanczyk, Goodman, Rohde, Graeff-Martins and Salum18–Reference Whelan, Leibenluft, Stringaris and Barker20 We conclude that DMDD is a manifestation of familial disposition that overlaps with liability for major depressive disorder.

Limitations

The results have to be interpreted with regard to several limitations. First, to establish specificity of DMDD with familial history of bipolar disorder, we examined offspring of parents with bipolar disorder, offspring of parents with major depressive disorder and offspring of parents with no major mood disorder. However, we did not include offspring of parents with other psychiatric disorders, which limits our ability to generalise our findings to family history of other disorders. Second, our sample size was limited and only six participants met the full diagnostic criteria for DMDD. Although our sample was sufficient to establish statistically significant differences between groups, a larger sample is needed to provide accurate estimates of DMDD prevalence. The differences between the present and previously reported findings underlines the need for these samples to be assessed with instruments designed to establish the diagnosis of DMDD. The sample size and age range also limit the description of comorbidity. As expected the diagnosis of DMDD was highly comorbid, especially with ADHD. The rate of ADHD was high in both the offspring of parents with major depressive disorder and offspring of parents with bipolar disorder. We found a relatively low overlap between ODD and DMDD with only three of the six individuals with DMDD having an ODD diagnosis. This may indicate smaller overlap between rigorously assessed diagnoses of DMDD and ODD than that reported in previous literature. Reference Copeland, Angold, Costello and Egger10,Reference Freeman, Youngstrom, Youngstrom and Findling30 However, since the number of participants with DMDD in the present study was small, a conclusion on the rates of comorbidity may need to wait until more studies of DMDD with DSM-5-specific diagnostic instruments accumulate. The ODD diagnosis (as all other diagnoses) was established in consensus meetings and recorded only if the full criteria for the diagnosis were met. The most common reason for not giving the ODD diagnosis in the present study was that less than four of the A diagnostic criteria for ODD were established at clinical threshold.

Implications

Our results have implications for clinical practice and future research. Clinicians who use DSM-5 criteria may be relieved to know that the newly introduced DMDD diagnosis only captures a few patients who are severely affected, does not contribute to overdiagnosis of mental illness in children and does not carry implications regarding liability to bipolar disorder. Given the current state of knowledge, clinicians should avoid raising parallels with bipolar disorder when discussing temper outbursts and persistent irritability with patients and families. Regarding implications for future research, the present work emphasises the need for a dedicated diagnostic instrument and cautions against extrapolating symptom indicators from other diagnostic concepts to DMDD. Longitudinal follow-up of individuals diagnosed with appropriate instruments is needed to establish the predictive value of the DMDD diagnosis. In conclusion, the first familial high-risk study with directly established diagnosis of DMDD does not support a specific association between DMDD and familial liability to bipolar disorder. The results suggest that the DMDD and its symptoms may be more prevalent among offspring of parents with clinical depression.

Funding

This work has been carried out thanks to funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (funding reference numbers , , and ), the Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation, the Canada Research Chairs Program and the Dalhousie University Department of Psychiatry.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.