Introduction

Have you ever encountered a group of people who work really well together and come up with innovative solutions to shared problems? It might be a group of lobbyists, aid workers, civil servants, amateur photographers, or the participants to a research seminar at your university. If the group ‘works well’, then it is probably a community of practice (CoP).Footnote 1 CoPs are groups of people knit together by a common passion or endeavour, who enjoy doing it well and develop a set of tools to continue doing it well. A practice brings them together, but the existence of a CoP is essential to promote, anchor, and innovate upon that same practice in the face of ever-changing circumstances. This article analyses what CoPs do, arguing that a CoP fundamentally contributes to its founding practice by timing it and placing it, and by doing so with humour. Practices are embedded in time and space, while contributing to sensemaking,Footnote 2 of which humour is an aspect. By resolving uncertainty in the here-and-now, and through humour, a CoP maintains a practice alive. When no CoP exists to support it, a practice is hampered in its capacity to renew itself, even if there is a network of practitioners or an institutional setting tasked with performing it. CoPs are ‘the vanguards’ of ‘social structures across functional and geographical boundaries’Footnote 3 and thus belong to the analytical toolkit alongside networks, institutions, and other categories through which International Relations (IR) scholars analyse sources of stability and change in international politics.

CoPs have been brought to IR on the back the so-called practice turn,Footnote 4 but their utility is broader and their promise remains, so far, partly unfulfilled. In the original interpretation proposed by Etienne Wenger,Footnote 5 CoPs displayed three characteristics: a shared practice, a common engagement forged in participating in a practice together, and a set of tools developed to help in the practice's performance. They are defined as ‘like-minded groups of practitioners who are informally as well as contextually bound by a shared interest in learning and applying a common practice’.Footnote 6 A CoP's perspective thus brings to the fore how sociality among practitioners impacts on the way in which practices are learned, enacted, and innovated.Footnote 7 While practices constitute CoPs, CoPs constitute practices by performing them. They simultaneously promote, anchor, and change practices. Social orders ‘originate, derive from, and are constituted constantly by practices, the background knowledge bound with them, and the communities of practice that serve as their vehicles’.Footnote 8 CoPs are not empty vessels, though. They are agential too, and this article aims to show how this part of the story unfolds.

To advance this debate, the article analyses what CoPs actually do. It identifies three key dimensions of CoPs, namely their sense of timing, sense of placing, and sense of humour. These three not only are part of what CoPs are, but also represent what CoPs do everyday, that is, they time, place, and make sense of their shared practice. This can refer to any practice under scrutiny, from diplomacy to aid distribution to war rapes to protests. The argument presented here suggests that IR scholars can better interpret social reality through the lenses of CoPs and observing how they time, place, and (re)centre contemporary practices. A CoPs framework operationalises the ‘feel for the game’. Practices are temporally and spatially bound, and so are CoPs, that is, existing in a specific time and place. But more specifically, CoPs also bring a social and shared sense of timing and placing, as in the ‘right time’ and the ‘right place’ to perform a practice. In fact, the former depends on the latter: the objective dimension of time and space (when and where a practice is performed) derives from the qualitatively different, subjectively shared conception of timing and of placing, which identifies the ‘right’ time and place for a practice's performance. The local and timely performance of a practice thus depends on the practitioner's ‘feel for the game’ that is socially honed within a CoP. CoPs are also made of humour, which is a broader practice to which CoPs anchor their doing. A sense of humour is a sensemaking tool, as well as an affective and social mechanism. Ridicule, jokes, banter, etc. in a CoP are a way to centre or recentre the attention on the practice at stake and on a specific interpretation of it, while providing affective identification and indulging in an aesthetic performance. Even though it might seem over-ambitious to bring together these three aspects of timing, placing, and humour (libraries could be filled with the related literature), my point here is that CoPs are a useful analytical tool through which to look at our being in the world, which also depends on time, space, and sensemaking.

To illustrate the relevance for IR of these dynamics (explored in section 1), this article will address similarities and differences between CoPs and three proxy concepts: institutions, networks, and epistemic communities (section 2). It will then relay dynamics of timing, placing, and humour in the example of EU foreign policy towards the Israeli-Palestinian conflict (2010–14), when the EU developed one of its most original contributions to the debate (section 3).

On time, place, and humour

While CoPs were originally conceived to account for the social aspect of learning in organisations,Footnote 9 they are a useful analytical device in and of themselves. In the original interpretation proposed by Wenger, CoPs rested on a practice, a common engagement emerging from performing the practice, and the set of tools developed to improve on the practice's performance. The reference to tools and innovation inspired literature in Management, in the attempt to harness the potentially rich dividends in terms of knowledge creation. This article takes a different approach and suggests that a CoP's performative aspect occurs primarily through the CoP's shared sense of timing, placing, and sensemaking, as exemplified by humour. A CoP is thus a group of people sharing not only a practice and an identity, but also (and because of them) a sense of what is the right time, the right place, and the right thing to do. Time and place have been understood in different ways, the most significant distinction being between objective and subjective definitions. The argument here is that CoPs share the latter, subjective, qualification, on which the former, objective, view actually depends. A more complex aspect is sensemaking, which I will analyse through humour, to capture dynamics that are simultaneously affective and cognitive. Therefore, this section will focus on the sense of timing and of placing, before addressing sense of humour in a CoP.

A good place to start is the distinction between chronos, as an abstract and exact quantification of passing time (for example, clock-time), and kairos, as the ‘right moment’ to do something (a ‘transformational time of action’).Footnote 10 This distinction mirrors two different notions of space, namely chora, as a space clear of something, and topos, which indicates a definite place. Both the more abstract conceptions and the more situated ones are relevant to CoPs, but the latter ones are particularly significant: not only CoP's members meet at the same time in a given place, but they do so because they consider that time and place appropriate for the task at hand. It is their shared view of the right time and place (a subjective sense of timing and placing) that affects the arrangement in time and space (an objective space-time),Footnote 11 as well as their practical doings. I am here building on Thoedore R. Schatzki, as well as on temporal-spatial scholarship in IR,Footnote 12 to suggest that it is the shared sense of timing and placing that defines CoPs doings, both their content and format.

A sense of timing

Time influences politics in many ways, from the contemporary ‘crisisification’ of politicsFootnote 13 to the idea that the everyday matters.Footnote 14 A shared sense of timing, however, is different as it shifts our analytical gaze to the ‘activity of timing’Footnote 15 and how it affects the practice's enactment. It is the art of grasping the right moment for the right political action. In Policy Analysis, this has been compared to a surfer aiming to catch a big wave.Footnote 16 A sense of timing lies in the surfer's capacity to read the waves, and time her/his efforts accordingly. In practice parlance, the practitioner reads the ever-evolving landscape of practices, and imagine and produce dynamic processes.Footnote 17 A sense of timing in a CoP is about a group of people sharing a sense of when to do what, in the face of mixed external signals and political uncertainty. It is at the basis of the CoP's capacity to turn the complexity into action. It is about the sense of occasion that transforms the storyline and the rhythm that allows political activity to unfold, affecting both political stability and change.Footnote 18

For instance, as I have shown in the case of the CoP of EU diplomats communicating via the secure telex system COREU, the members’ sense of timing makes it possible to reach decisions via the assent procedure, which foresees that a circulated proposal will be considered agreed upon if no objections are raised by a given time. This is a notable decision-making system, even more so because the rulebook excluded use of the COREU system for taking decisions. The system relies on CoP members sharing a sense of when the assent procedure via COREU is the right procedure for which proposal, which deadline is appropriate, and acting (or reacting) to that purpose in such a way that the system can produce a decision. It is an informal mechanism for getting the job done, in reaction to uncertainty and time pressure, to keep the discussion going.Footnote 19

Other examples of timing or ‘right time’ can be seen when different senses of timing clash. When Sweden joined the EU, its diplomats were faced with a different sense of timing: they had ‘much less time to prepare’.Footnote 20 The perceived scarcity of time was due to the need for the Swedes to learn a new sense of timing for their policy initiatives within the EU context, how to phrase what and when, in order to have a political impact. The same experience occurred to Polish diplomats at the time of Poland's accession to the EU. At first the difference in sense of timing was so strident that Poles believed they were not taken seriously by their EU partners, who gave them so little notice on important matters.Footnote 21 This was resolved, as officials were socialised into not just a different rhythm, but also a different sense of how to act on it and what to do.

This aspect is generalisable beyond European diplomacy. A similar dynamic can be seen in early colonial Algeria, where different understandings of ‘right time’ clashed on a bigger scale.Footnote 22 The French colonial project aimed at establishing a new, linear, and progressive development, which justified the abolition of traditional institutions (so the French CoP colonising Algeria oversaw their ‘timely’ abolition). However, these predatory governmental practices clashed with the local CoP's sense of timing, based on the Islamic injunction to contribute every year to traditional institutions in aid of the poor in order to minimise inequality across Algerian society.Footnote 23

A CoP's perspective thus points to the extent to which the CoP's members share not only the same time, but also the same sense of timing, directing the analytical gaze to explore time, timing, and its practical consequences.

A sense of placing

A CoP shares a sense of place or, more accurately, of placing, an aspiration towards the most appropriate spatial collocation for the constitutive practice, which in turn affects the practice with its physicality. Place differs from space,Footnote 24 and from site too.Footnote 25 While space is abstract and everywhere, place is specific and somewhere: it is ‘a space with attitude’.Footnote 26 The same location can be both place and space depending on the perspective involved, place being at a lower level of abstraction.Footnote 27 A focus on place ‘brings out the delicacy of situated relationships’Footnote 28 and prompts us to consider how practitioners act in space to impress an ‘attitude’ to it, and how the ‘attitude’ impresses the practice and the practitioners. ‘[A]ll practices in the landscape have a fundamental “locality”.’Footnote 29 Moreover, place differs from site, the latter being where practices occur. Practices are performed in a site and sites are where practices can be captured analytically. A site is a place ‘where something happens’.Footnote 30 Revolutions tend to occur in streets, war in a theatre, diplomacy at the table, be it a negotiating or a dining one. Members of a CoP are likely to be at the site where the practice is enacted, as this is part of their sense of place, but their sense of place (of placing the practice) is what actually creates the site. Therefore, CoPs define the region to which the practice applies and its boundaries, designing a new territory and a new practice landscape.

In the case of diplomats, for instance, their ‘diplomatic sense of place’ means that they know where they, and the countries they represent, stand in the international ‘pecking order’,Footnote 31 which in turn involves their place in a funeral procession or when (if) to sit at a negotiating table. In the case of counter-piracy, for instance, security communities drew technical maps and patrol zones, as well as collaborative practices to police them,Footnote 32 and the latter would not have happened without the former.Footnote 33 The EU ‘sofagate’ scandal of April 2021 also illustrated this point, by showing divisions inside the EU: Turkey's president Erdogan managed to (literally) physically divide the EU delegation that came to negotiate a relaunch of EU-Turkey relations by providing only one chair, which European Council president Michel took, leaving European Commission President von der Leyen on the sofa. Therefore, a sense of placing defines the sense of one's own position in a physical sociopolitical context. It is central to the ‘feel for the game’ and it affects a practice's performance.Footnote 34 It is a way of being in the world, which is socially embedded, as well as geographically bound.

The second analytical contribution of a CoP's perspective pertains not only to sites in which the practice is enacted, but also to the sense of placing that CoP members share in identifying the sites, and its consequences. Similar considerations apply to other, iconic sites: the negotiating table (when diplomats reach it, they are under pressure to make something happen, something that will be affected by a CoP's sense of placing and timing, which might be, for example, more dramatic);Footnote 35 the water fountain (where compromises are often struck, if the CoP considers it appropriate to strike compromises in corridors); the cafeteria (where sociality hones a CoP's skills), etc.Footnote 36 A sense of placing thus ‘stems from a stock of tacit know-how acquired from experience’Footnote 37 and CoPs are particularly relevant here, given their nature as learning environment.Footnote 38

Timing and placing are related, and both pertain to CoPs.Footnote 39 A sense of the ‘right time’ and ‘right place’ are a way of being in the world. They represent not only an ‘arrangement’ structured by past practices, but also something relevant in structuring future pathways of practice development.Footnote 40 Schatzki expresses this by unifying time and space in ‘activity timespace’, which is constitutive of human activity.Footnote 41 Others have aimed to capture their relationship by analysing their rhythm,Footnote 42 or by highlighting how to capture them in ‘micromoves’ of international politics.Footnote 43 My point is that CoPs simultaneously time and place a practice, while displaying and refining a sense of time and place. Learning happens in time and across places, and over time the ‘regime of competence’ associated with a CoP ‘implies a sort of colonisation of the social space: it defines what counts as competence there’.Footnote 44 This is particularly topical for IR because contemporary politics is often characterised as composed of increasingly desynchronised rhythms of everyday life and the perceived compression of time and space.Footnote 45 A CoP's perspective thus provides the analytical tools to assess such a claim and informal practices of resistance and participation to the global trend.

A sense of placing and timing explains for instance why visa practices of the Belgian, French, and Italian consulates in Morocco have converged.Footnote 46 Officials from these countries, tasked with Schengen visa provision, represent a CoP meeting on Tuesdays at a restaurant in Casablanca, at times also joined by Spanish officials. The site is a restaurant, the day is Tuesday. Thanks to this meeting practice, diplomats exert the same sense of placing of visa stamps on specific passports in a timely fashion. Over lunch, officials share the tricks of the trade and make sense of their work, engaging in and producing local knowledge about to whom to grant a visa and why. An interesting aspect emerges in comparison to the formal meetings of representatives from all Schengen countries, the so-called Local Schengen Cooperation group. This group meets at the EU Delegation and discusses basically the same topic. However, informal interactions at a restaurant between members of a selected group constituted as a CoP better achieve their countries’ formal objectives, leading practitioners to perform visa granting in a specific way.

In a similar case, the CoP composed of European diplomats in JerusalemFootnote 47 relies on its sense of placing and timing, which includes the EU Delegation's anonymous building (with a temporary lease and no EU flag), as well as the experience of time-consuming Israeli checkpoints to reach it. Foreign policy practices that emerge from this CoP (some of which analysed in section 3) are informed by the CoP's shared sense of timing and placing, which includes a more explicit call for urgent action and a clearer reference to spatial coordinates where precise initiatives are to be taken.

A sense of humour

The ridicule that takes aim at a practice can certainly do some harm to ideas or feelings of targeted practitioners, but it will always bring one of two advantages: either it destroys the practice, if it is redundant, or it will improve it, if it is useful or too strong to be destroyed. Ridicule always leads to seriousness because the ridiculed wants to prove himself worthier, either by dropping the practice or by seeking the practice's most veritable and sensible part, for which he cannot be ridiculed.Footnote 48

A last key aspect characterising CoPs, together with a sense of timing and placing, is a sense of humour. Defined in various ways, humour can serve a range of purposes.Footnote 49 It is relevant in this discussion of CoPs because, as an overarching practice, humour not only ‘does’ the community, but also ‘does’ (anchors) the CoP's practice. In my case, for instance, I set out to investigate the humorous side of EU foreign policy (the illustrative example in the next section) because I believed that the CoP behaved as a ‘community of laughter’ and humour was a reinforcing mechanism of the social aspect – which it was, but as we are going to see in section 3, alongside the social aspect humour was also used by key CoP members to define the practice itself, the interpretation to be preferred and the support it received in a long negotiating process.

First, humour ‘does’ the community, in various ways. It is social and as such, it is a discursive and affective tool, contributing to the CoP's existence and its boundaries. Supportive humour expresses solidarity and integrates participants into a learning environment that accepts them as novices.Footnote 50 Contestive humour serves as an acceptable vehicle for venting aggressive feelings and can be used to negotiate challenges inside the CoP. Subversive humour creates distance and identifies outsiders, sanctions members, and discriminates against alternative practices. Therefore, humour ‘is performative of agency within problematic social structures’.Footnote 51 It can replicate the authority of established practitioners, who are to be respected if they are to be seen as masters of their art. It can also be part of the ‘arts of resistance’.Footnote 52 It is ‘a coping mechanism’, helping to both maintain and disrupt social order.Footnote 53 It strengthens a CoP's core while also constructing the boundary that separates insiders from outsiders. The boundary towards outsiders establishes resistance to order imposed from above, a key aspect in the constitution and maintenance of an interpretative community in a broader institutional setting.

Second, and most importantly, humour ‘does’ the practice too. It is part of the sensemaking work that occurs in a CoP, which allows it to meet uncertainty. As exemplified in the quote above by Alessandro Manzoni, humour is effective in (re)centring a practice, thus making the practice possible. It is a way in which sensemaking occurs, by reinforcing some aspects and downplaying others. Through humour a CoP updates its definition of the founding practice and negotiates meaning: ‘under the moral smokescreen supplied by humour’, practitioners ‘express the ambiguity that they feel’Footnote 54 and try to resolve it by identifying the main components. As shown by Joanna Tidy in the case of banter in the production of military violence,Footnote 55 humour makes violence palatable and socially legitimate, as well as meaningful and intertwined with (men's) fun. Humour thus works as a tool to negotiate what the practice is (or should be) about. It occurs because repertoires remain partly ambiguous and thus open-ended, relying on ongoing participation and continuous negotiation of meaning.Footnote 56

Humour enlivens the repertoire of resources that is continuously created and re-enacted in a CoP, turning the unexpected into normality and maintaining the practice alive. This can also lead to quite aggressive humouring tactics. In an early analysis of a CoP composed of technicians repairing photocopiers, for instance, practitioners were recorded as working very hard at adding humour to their ‘war stories’ of repairing machines despite wrong error codes, often at the expense of their fellow practitioners – those same fellow practitioners they encouraged with advice and emotional support.Footnote 57 Therefore, humour in a CoP's perspective composes the social and cognitive texture of a CoP and affects its founding practice. It testifies to the robustness of the CoP and of its core practice, as well as the limits the CoP's and the practice's social acceptability. The scholarly task is thus to understand how humour unfolds in relation to a community and to its founding practice.

Humour ‘does’ the community and the practice simultaneously, as well as with a sense of timing and placing. For instance, the EU has supported the creation of ‘international law enforcement coordination units’ to foster police cooperation in the Western Balkans.Footnote 58 This instrument was successful in a variety of ways, leading to what was arguably a transnational CoP of police officers. A major effect of this was the involvement of Kosovars and Serbs in the same group, despite the persisting absence of diplomatic relations between the two countries. In these units, law enforcement was understood in an expansive way. The CoP coordinated police operations extraditing suspects between Kosovo and Serbia, despite the absence of an official extradition agreement between them. The subjective and shared understanding of timing and placing determined the when and where of what was de facto a prisoners’ handover between two non-mutually recognised states.Footnote 59 The CoP made it look as if prisoners ‘happened’ to be there at the right time in the right spot. Footnote 60 Therefore, thanks also to the EU support, law enforcement created the disposition of practitioners and a CoP. The CoP in turn anchored and innovated on the founding practice through its sense of timing and placing. Moreover, the most trust-inducing component occurred in ‘the unofficial part of the programme and informal interactions during breaks’.Footnote 61 As I discussed this case with one of the researchers, the socialising element of jokes during the break came up, and the researcher remarked the key importance of humour in ‘doing’ community and practice work between Kosovars and Serbians over a cigarette in the break. This is also the environment in which a former KFOR military official joked about ‘happy-hour networks’ involving local and international practitioners.Footnote 62

These three characteristics – a shared sense of timing, placing, and humour – represent the key performative aspects of CoPs, that is, of how CoPs perform and constitute practices. They place, time and (re)centre the practice, while probing a CoP's social and cognitive boundaries. In other terms, they contribute to tackle challenges at the local level and anchor/innovate on the constitutive practice. As Emmanuel Adler put it, ‘[b]y facilitating both the innovation and stabilization of practices, communities structure consciousness and intention, constitute agency, and encourage the evolution or spread of social structure.’Footnote 63 And, as it has been shown, this happens in time, space, and affection/cognition, thanks to a CoP's shared sense of timing, placing, and humour.

CoPs, institutions, networks, and epistemic communities

While the general utility of CoPs for IR scholars lies in the analysis of the practical and informal side of international politics, their specific role emerges in relation to proxy concepts. More specifically, CoPs add on to both institutional analysis and network analysis in IR, while they overlap with epistemic communities, as we are going to see. CoPs ‘do’ the institution ‘in practice’: they embody the practical side of formal structures, capturing a more realistic story. Institutions are relevant to international affairs because practitioners embody them. A CoP's relation to social networks is instead different. Social networks, and especially cliques, might be CoPs. But there is a fundamental difference in the analytical purpose brought to bear, as practice approaches do not share the positivist endeavour of a large part of Social Networks Analysis (SNA), which characterises also Management Studies. There is a near complete overlap with epistemic communities and security communities. I will explore these three aspects (a CoP's relations with institutions, networks, and epistemic communities) in turn, while also highlighting origins, evolution and possible death of CoPs.

First, it is not a coincidence that the vast majority of analyses of CoPs in an international environment have been conducted with reference to an institutional setting. CoPs are to institutions what practice approaches are to norm-based constructivist analyses, namely a more practical way to express what institutionalists have been attributing to institutions. CoPs enliven the practice that institutions were created to support, while institutions provide opportunities and sites that CoPs can exploit. The iconic example here is Adler's analysis of NATO's expansion in the 1990s.Footnote 64 While other explanations of NATO enlargement stressed interests or rhetorical entrapment,Footnote 65 Adler sees it as the expansion of a CoP based on cooperative security and self-restraint. It occurred as NATO involved Central and Eastern European countries’ officials into shared training and military exercises, transforming their security identity and embedding them into the CoP.

While Adler suggests a cooperative relationship between the institutions and the CoP, Benjamin Schulte, Florian Andresen, and Hans Koller track a different trajectory in their analysis of how a CoP changed the practice of the Germany Federal Armed Forces.Footnote 66 Here the CoP emerged against the institution, as single practitioners became aware of the Army's limitations in handling intercultural issues in military missions abroad. Practitioners thus started to reach out and connect across hierarchical boundaries, outside (and partially against) the formal institution. As reported by an interviewee, ‘[we] sat down together after official duty with a beer and a cigarette and discussed about how to better structure a network’ with the aim to introduce intercultural training. In a second stage, the CoP benefited from the support of the institution, as CoP members’ superiors bestowed legitimacy and material resources onto the CoP. This case thus shows that CoPs, by definition informal and horizontal, can emerge even in a most formal and hierarchical organisation such as the German Army, as long as in the beginning practitioners enjoy (or appropriate) a degree of autonomy. On the other hand, some subsequent structuration contributes to integrate the practice in the wider institutional setting.

While institutions can contribute to a CoP's origin and/or evolution, they cannot create them if practices are not aligned. For instance, mirroring NATO's expansion, the EU also tried to spread cooperative security by reaching out to Morocco, as analysed by Niklas Bremberg.Footnote 67 It provided sites where practitioners could meet and discuss solutions to shared problems. But practitioners diverged about the practice's definition (such as the legitimacy of monitoring ‘potential social crises’) and the endeavour fostered the creation of transgovernmental networks rather than a CoP based on a shared security identity across the Mediterranean. In the case of EU climate security, Niklas Bremberg, Hannes Sonnsjö, and Malin Mobjörk suggest that a CoP might be in the making, but there are substantial differences in practices of diplomacy, development, and security and defence even though all practitioners belong to EU institutions.Footnote 68 Some competition is, however, innate in the way the practice shapes the community and thus at times CoPs can accommodate it. For instance, Nina Græger analyses EU and NATO cooperation, which is usually seen as paralysed by the Cyprus-Turkey dispute. She shows a landscape of thick staff-to-staff practical cooperation on the ground, entailing operational and tactical informal cooperation in a CoP composed of EULEX and KFOR practitioners in Kosovo, despite a degree of competition among members.Footnote 69

CoPs ultimately originate in the practice alignment of CoP members, in the shadow of institutions. Kiran Banerjee and Joseph MacKay have examined the case of two CoPs composed of military attachés in Japan and in Russia at the time of the Russo-Japanese war (1904–05).Footnote 70 They argue that the two CoPs emerged as the practice of military attachés spread across the world, itself a part of the globalisation of Western forms of military discipline. The CoPs provided a fundamental contribution not only to the understanding of the war itself, but more generally to the reassessment of Japan and Russia in the global security hierarchy, with Japan increasing in relevance and Russia decreasing. Christian Bueger's analysis of counter-piracy CoPs also stresses the key centrality of security alignments, driven by concrete problems and shared understandings of best practices.Footnote 71 Patricia Goff too stresses the relevance of mutual engagement around the task of public diplomacy, as well as of previous meetings devoted to clarify the foundational concepts from which the UN initiative ‘Alliance of Civilization’ was born.Footnote 72 Other cases from ASEAN,Footnote 73 the South American Defense CouncilFootnote 74 and the spread of early warning systemsFootnote 75 further stress the point. As a flip side, CoPs are seriously weakened when practices diverge or when institutions lead to practices’ decay. When practitioners are transferred, for instance, the CoP might be unable to recompose the fracture.

Therefore, a CoP approach can contribute to better understand how practices and CoPs enliven or modify institutional goals, bringing to the fore their informal aspects. While institutional approaches might imply that rules are all there is to see, a CoPs perspective underscores instead that what matters is above and below the rules, and does not necessarily coincide with them, as CoPs can exist within and across institutional boundaries. An institutional boundary ‘may therefore correspond to one community of practice, to a number of them, or to none at all’.Footnote 76

Differently from institutions, the relationship between CoPs and networks has come under less scrutiny and retains a degree of uneasiness. From a practice perspective, this does not have to be so. A first possibility is to distinguish between a network of practice (NoP) and a CoP, with the former designating ‘the collective of all practitioners of a particular practice’Footnote 77 and the latter instead the learning environment within the practice. NoPs thus highlight which practitioners are sharing in the same practice. Learning in a NoP does occur, but distant practitioners exchange global know that, rather than know how. NoPs can include one or several CoPs, which are the point of entry for the NoP:

The central distinction between the CoP and the NoP turns on the control and coordination of the reproduction of a group and its practice. Newcomers enter the network through a local community. You become an economist by entering an economics department in Chicago, or Berkeley, or Columbia – a route that may mark you for life, in part because the tacit knowledge of the local community profoundly shapes your identity and its trajectory.Footnote 78

A second possibility is to recognise that much of network analysis, especially in the form of communities or cliques, tackles the same phenomenon as CoPs, but with a fundamental difference in analytical gaze. In IR, networks have gained a large following, with an emphasis on a positivist epistemology. They have been defined as ‘sets of relations that form structures, which in turn may constrain or enable agents’.Footnote 79 Their defining feature is the link among nodes (or agents). Their focus is on ‘formal properties of social relations and the investigation of the configurations of social relations that result from the interweaving of actions in social encounters’.Footnote 80 The type, quality, and content of the relationship is largely open, which provides the opportunity to also consider more cohesive groups within a network such as cliques. Social interaction patterns show ‘thick spots – relatively unchanging clusters or collections of individuals who are linked by frequent interaction and often by sentimental ties … surrounded by thin areas – where interaction does occur, but tends to be less frequent and to involve very little if any sentiment’.Footnote 81 Therefore, a network is said to have community structure if it ‘divides obviously into groups of nodes with dense connections internally and sparser connections between groups’.Footnote 82 The measure of ‘modularity’ was developed to capture the degree to which each partition of a network embodies a community-like form and ‘strong’ communities are said to occur when every node has more within group ties than cross-cutting ones.Footnote 83 Links can be weighed with a numeric value to indicate the connections’ strength, as in groups of mutual acquaintances, subsets of Web pages on the same subject and citation groups in networks.Footnote 84

While CoPs and cliques thus seem to identify very similar phenomena, the analytical gazes of network analysis and practice approaches generally involve different research trajectories. Much of network analysis is devoted to quantify networks’ shapes and properties. From a practice perspective, however, network analysis stops when things become interesting, that is, having identified a potential cluster of people. A CoP's perspective comes into being exactly at this point, to show how practitioners interact, learn, promote, or innovate on the practice, zooming in on the local empirical details that can illuminate the broader picture. CoPs differ from networks ‘mainly because they involve not only the functional interpersonal, inter-group, and inter-organisational transmission of information as networks do, but also processes of social communication and identity formation through which practitioners bargain about and fix meanings, learn practices, and exercise political control.’Footnote 85 Practice approaches favour an in-depth look at where CoPs are coming from, how they work, and where they are evolving to, via, for example, ethnographic studies (though not as a panacea) or less traditional forms of interviewing, if possible, such as shadowing and the interview-to-the-double.Footnote 86

The bottom line here is that a CoP perspective relies on an interpretive epistemologyFootnote 87 according to which analysing a social context is an art rather than a science.Footnote 88 Too strong a vocabulary, such as ‘where does a practice end? Who's in and who's out?’, would be misleading, as practice approaches privilege flow over definite, well-bounded units. The emphasis is on processes and ‘the emergence and creation of (provisionally) identifiable units (individuals, groups, organisations) as the thing to be explained’.Footnote 89 The aim is to open a conversation, more than close it. Scholars working in the practice perspective caution against ‘the fixation of many empirical researchers who, on the basis of the features described by Wenger, have debated the issue of whether or not a certain set of workers can be defined a community of practice, assuming that the term CoP designates an entity endowed with “real” existence.’Footnote 90 The concept is better used as a metaphor and an analytical tool, which still entrusts it with ‘real’ effects, but the substance of what is under scrutiny is at least inspired by critical realism, if not anti-foundationalist altogether. These ontological and epistemological differences should not be reified, though. Poststructuralism has engaged with positivist methodologies and is amenable to some form of (thin) explanatory analysis.Footnote 91 A liberating aspect of practice perspectives is the emphasis on bricolage and patchwork methods, which suggests that there is potential to build on network analysis.Footnote 92

Finally, there are several similarities between a CoP's perspective and analyses focusing on ‘other’ communities, namely epistemic communities and security communities.Footnote 93 Epistemic communities and security communities can be considered CoPs when the analytical focus is on the practice that underpins the community, as well as on the learning element that keeps that practice alive. Peter M. Haas, who coined the term of ‘epistemic community’, defined it as a ‘network of professionals with recognized expertise and competence in a particular domain and an authoritative claim to policy-relevant knowledge within the domain or issue area’.Footnote 94 The knowledge-producing aspect of epistemic communities, for instance, can be conceptualised in two ways: first, there is a sharing of information and knowledge that, which is the aspect most generally under scrutiny, especially in the literature addressing policymaking; second, there is a more intimate aspect of knowing how, which drives the social underpinnings of knowledge considered objective – and this is done in a CoP. The literature has predominantly embraced epistemic communities to emphasise scientific knowledge as the main source of cognitive authority and of transnational cooperation.Footnote 95 This is not a necessary component, though, as the community's professionalism and robust internal cohesion can be taken as actually the main characteristics.Footnote 96

Therefore, a CoP analysis adds a focus on how learning in a group affects the practice they all perform, to the point that, as I suggest, the vitality of a practice depends on the existence of a CoP to keep it fresh in the face of changing circumstances. The purpose here is not to convince IR scholars to abandon well-established terms such as institutions, networks, security communities or epistemic communities, but rather to include CoPs to their analytical repertoires, in order to be able to recognise a CoP if they see one.

Timing, placing, and humour in the EU foreign policy towards the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

To further illustrate a CoP framework based on sense of timing, placing, and humouring, this section analyses EU decision-making in relation to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict during the period 2010–14, when the EU was particularly effective and innovated in fundamental ways on the existing practice. At the centre of the EU's effectiveness and innovation was a CoP composed of practitioners belonging to EU institutions and beyond, who met in Brussels and worked passionately on the EU foreign policy stance towards the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. In the word of a participant to the CoP, at its core this was a ‘group of people who knew well the topic and the situation on the ground – a group that was competent on the topic’.Footnote 97 As I am going to show, they worked by situating the practice of EU foreign policy in time and place, and through humour.

A brief backgrounder on the practice's landscape might be useful here. By 2010, the practice of EU foreign policy towards the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was at an impasse.Footnote 98 The broad EC/EU position had been roughly stable for three decades, since the Venice Declaration in 1980 codified the main tenets of what later became known as the two-state solution. This position was then practiced in a number of ways. There was an open channel for trade with the Palestinians, finalised in 1986.Footnote 99 There was a diplomatic track, by which the Europeans periodically reiterated that Israeli settlements were (and are) illegal under international law and any changes to the pre-1967 borders had to be agreed by both parties.Footnote 100 These practices became increasingly untenable, however, and vague. The so-called Middle East peace process further deteriorated, with the 2008–09 Gaza war and the election of Netanyahu in 2009. The European Court of Justice stressed in December 2009 the need to clarify the territorial basis of agreements between the EU, on the one hand, and third parties, on the other.Footnote 101 Member states, the European Parliament and civil society activists added their weight to request change, creating a permissive consensus and a favourable disposition in a number of practitioners.Footnote 102

The practice was revived by a group of people that emerged as a CoP working on the EU position vis-à-vis the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. There was a formal group, named the Inter-Service Group on Israel-Palestine and composed of representatives of EU institutions: the European Parliament, the European Commission, and the European External Action Service (EEAS).Footnote 103 Alongside this formal group, there was an informal group, which constituted a CoP and was much more crucial to policy developments. It brought together representatives of the EEAS and legal, financial, and external relations experts in the European Commission, as well as practitioners of the EU Delegation in Tel Aviv and the EU office in Jerusalem and two lobbyists belonging to different entities, with specific technical expertise. Interactions took place in Brussels, which emerged as the key site for policymaking. Practitioners based in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv flew more often than usual to Brussels to provide their contribution. In fact, this period marked the last period of ‘Brusselisation’ of EU foreign policy, that is, the concentration in Brussels of key decisions.Footnote 104 While member states’ capitals were soon to become more relevant, during 2010–14 Brussels was the site in which EU foreign policymaking occurred, as this CoP placed its practice around the Rond-Point Schuman in the European quarter of Brussels. There was an objective time and an objective space, which emerged from the CoP's sense of timing, placing, and humour.

The CoP's work led to significant innovations in EU foreign policy, through its sense of placing, timing, and humour. First, the CoP placed the abstract ideals of a two-state solution into a very fine-grained territorial picture, by literally geo-locating the practice. One of the big issues in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is where the border between the two countries is meant to lie. While international law has always been clear that the Green Line of the 1948 armistice is to be considered the border of Israel until the parties are to decide otherwise, international practice has been much more blurred. The CoP working on EU foreign policy retraced the Green Line and linked it to Israel's postal codes (which in Israel identify single buildings), thus providing a technical and relatively agile tool to differentiate the origins of goods and the location of actors. To do so, CoP members (and specifically officials from the EU Delegation in Tel Aviv) physically drove to contested locations to place the abstract policy to a specific site. They did so repeatedly, in an anonymous car, with no EU signs, to avoid being stoned in the process,Footnote 105 demonstrating how a local sense of practice is essential to the practice itself.

A set of technical measures then codified the EU position, the most famous of which were the so-called ‘Guidelines’ for Israeli actors applying to EU Horizon 2020 research funds, adopted in July 2013.Footnote 106 Israeli applicants were asked to declare they did not reside in settlements, and funded activities would not be held in settlements. Seemingly modest, this was the first ever act succeeding in having the Israeli state (which signed the related protocol about Horizon 2020) accept and declare publicly the difference between the state of Israel and Israeli settlements, while creating a legal mechanism for reclaiming funds in case of abuse.Footnote 107 This political and legal precedent, later renamed a ‘policy of differentiation’, has imprinted following measures and has become a staple of EU foreign policy. Other ‘placing’ acts occurred with the fact-finding visits that CoP members organised for other practitioners resorting from Brussels, Tel Aviv, and Jerusalem, to bring them to the sites in which the bordering practice of the EU was taking place (like in the case of member states’ doubtful trade attachées resorting from Tel Aviv).

While everyone interviewing practitioners about policy initiatives will be familiar with the list of (objective) dates, interviewees refer to when recounting policy developments, a CoP's sense of timing is most likely to underpin these dates. In this case, interviewed CoP members univocally mentioned 2009 as the turning point, when everyone agreed that ‘something had to be done’. The Gaza war, the election of Netanyahu, and the ECJ ruling contributed to create the CoP around a problem and to hone its sense of timing, which in turn brought people to the drawing board, to the negotiating table, and to Brussels cafeterias to discuss options. The record during the period 2010–14 is impressive, with more than ten measures adopted,Footnote 108 while measures have completely dried out since 2015. Notably, the CoP prepared Israel's reception of these proposals by using advance leaks. It would leak a stronger version than the agreed one in a discussion with individuals ‘close to Israel’, followed by the inevitable negative reaction, and then the originally agreed version or a slightly toned down one would be presented as a compromise. The proposal's practical details thus intertwined with the timeline and the momentum impressed by the CoP to the dossier. A further example of how the CoP shared a sense of timing is represented by the CoP's response to the looming EU accession of Croatia in July 2013. This posed a significant threat to the adoption of the Guidelines, because due to regulation adjustments it would have slowed down the process by c. six months, the equivalent of the time it took to draft them. The CoP thus worked around the clock to conclude the process before then, and they succeeded.

Humour comes in through a different trajectory, highlighting the composition of the CoP and its relation to the practice itself. In this case, master–apprentice roles were fluid, but there were key experts, and their capacity to organise informal contacts was crucial. A key expert cultivated the technical aspect. Upon this expert's invitation, for instance, one of the lobbyists came to Brussels to present a different narrative to EU officials, who at first struggled with the new, technical approach, but all practitioners involved were soon able to communicate thanks to the key expert's ‘translation’, as the expert laughingly reported.Footnote 109 Similarly, the early draft of a key document came back ‘unrecognisable’ to its creatorFootnote 110 because of the legal jargon applied by another CoP member, but this too was absorbed and the proposal progressed. This key expert, versed in all types of technicalities, took to share them with other EU officials with regular meetings at a nearby pub, on Thursday evenings, mirroring the previous examples about visas. The self-explained rationale for these meetings was that proposals would become EU law and they needed to be ‘understood, supported and implemented’ by everyone, so the aim was not just to instruct other officials, but ‘to enrich each other in understanding of how the different aspects could synergise’,Footnote 111 socially weaving a practical understanding of what the EU position could and should be.

Humour came further to the fore in the role played by a different expert, more devoted to administrative and political contacts across all institutional bodies in Brussels. Importantly, in this expert's view, the CoP (the ‘group’)Footnote 112 was born out of the difficulties engendered by the new institutional setting, which separated the EEAS from the European Commission, as well as from member states. Therefore, to measure de facto EU foreign policy's leeway on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, this expert reached out informally and bilaterally to all member states’ representatives for ‘a coffee’, a task that took ‘3–4 months’ but could not be done effectively by phone. After these bilateral informal meetings, policy proposals had to be sold in the multilateral institutional settings, where all member states were represented, and here humour was essential because ‘without humour, you are dead in the water’. Humorous interventions in debates included fake quotes from great men (for example, ‘as Clemenceau used to say …’) the main purpose of which was to ‘wrong-foot’ the opposition and to stress the need to ‘focus on substance, not on egos’. Emails directed to a multitude of stakeholders would include expressions like ‘the only one not in cc is baby Jesus’, again to invite a focus on the substance rather than on participants.

Humour also marked the end of this creative period, which was brought by the routine rotation of officials within the EU. After the Guidelines were passed, one of the experts gained significant notoriety for policy achievements. While travelling, the section boss jokingly said that thanks to this policy case ‘you had your 15 minutes of glory’.Footnote 113 From the interviewee's tone, it was clear that this was both praise and a way to stress that the 15 minutes of glory were over. In the framework of the regular EEAS mobility, the expert had just assumed a different post.

Adopting a CoP perspective thus allows us (as scholars) to identify the key elements in the evolution of the EU foreign policy towards the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The starting point is the practice (the EU foreign policy of this specific case), which evolves and delivers important innovations, presenting us with an empirical puzzle. This leads to research questions, the first of which is ‘who does it?’ with the aim to identify if there is a specific group of practitioners driving the dossier and performing the practice. If so, then three questions aim to clarify ‘how do they do it?’, namely about the CoP's sense of placing (‘where do CoPs members place the practice and how does that affect the practice?’), of timing (‘what timings are considered appropriate and how do they affect the practice?’), and of humour (‘what kind of humour is exercised and how does it affect the community and the practice?’). In the case examined above, during the 2010–14 period, the European position on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict (the practice) contributed to the engagement of a group of practitioners (the community) working through a set of legislative and administrative acts (the tools), which in turn innovated the practice by specifying Israel's territory to pre-1967 and the applicability of EU-Israel agreements only to that. A CoP analysis synthesises how this came about by arguing that the EU foreign policy towards the Israeli-Palestinian conflict during 2010–14 was driven by Brussels with a close attention to the local aspects of the border, with a quick succession of important measures negotiated in institutional venues only after an informal agreement to prepare the ground.

What is the added value of this approach compared to similar ones? An institutional analysisFootnote 114 miscalculates when real innovation stopped. In 2016, when the EU-based CoP had vanished due to staff mobility, member states still managed to pass two strongly worded declarations on the Middle East peace processFootnote 115 and in 2017 a new set of Guidelines was approved, in relation to labelling of goods. None of this was ever implemented, though. A CoP perspective thus more accurately identifies the moment, the group, and the ways in which change happens. Similarly, had this analysis been undertaken from the perspective of networks and cliques, it would have been difficult to identify the core group and understand its modus operandi, as practitioners were in constant contact. It would have been possible to define this CoP as an epistemic community, given its role in fostering new ideas and policy initiatives. A CoP perspective, however, shifts the emphasis from the cognitive dimension to the practical one, highlighting what practitioners actually do in relation to ideas, rather than assuming that practitioners rely solely on persuasion to move policy forward.

Therefore, a CoP perspective's analytical lenses allow scholars to identify and track how a practice evolves in the face of challenges and uncertainty through the appreciation of the time, place, and sociocognitive dimension of its members’ work. Since 2015, the CoP analysed above has disappeared, as members moved on, and the permissive consensus came to a halt. The emphasis has shifted towards member states and their capitals, with two groups of like-minded countries contending the EU's agenda, one in a more pro-Israel direction, the other in the opposite sense. As a consequence, EU foreign policymaking grounded to a strident halt and it remains to be seen if from either group of like-minded countries a CoP emerges to really innovate on the status quo.

Conclusion: IR and beyond

A CoP perspective captures the fleeting and ‘evaporative’Footnote 116 social dimension of international politics, as well as its impact. This article has argued in favour of including CoPs in the IR toolbox as a way to appreciate these informal dynamics. Whenever innovation and learning occur, CoPs are most likely to be at work. While CoPs emerge from a shared engagement in enacting a practice, they anchor, retain, and innovate on that same practice. How this happens, and to what effect, matters for IR and beyond. In this concluding section, I will review the argument presented, assess its relevance for IR, and suggest how a CoP perspective can contribute to debates also beyond IR.

The argument so far has built on Wenger's original work about CoPs, by analysing how CoPs affect their constitutive practice. Three analytical pathways have been indicated, based on CoPs’ sense of timing, placing, and humour. CoPs perform the practice in time and space, according to what its members consider an appropriate time and a right place. Every practice (as any political phenomenon more generally) is located in time and space, but CoPs enact and teach a specific subjective understanding of timespace, which is part of the ‘feel for the game’. CoPs appropriate the ‘transformational time for action’Footnote 117 and act on it, like diplomats sensing that the time is ripe for negotiations in a conflict, even though they are not certain of what negotiations will deliver. They situate the practice and turn space into a place and a site. A CoP's sense of humour contributes to the analysis, not just by expressing ‘a community of laughter’, but also by showing how CoP's members use humour to identify and promote a specific take on practice. A sense of timing, placing, and humour thus represent the three analytical devices which (together with Wenger's three criteria for a CoP, namely a shared practice, a common engagement, and a set of tools) can guide the research for IR scholars.

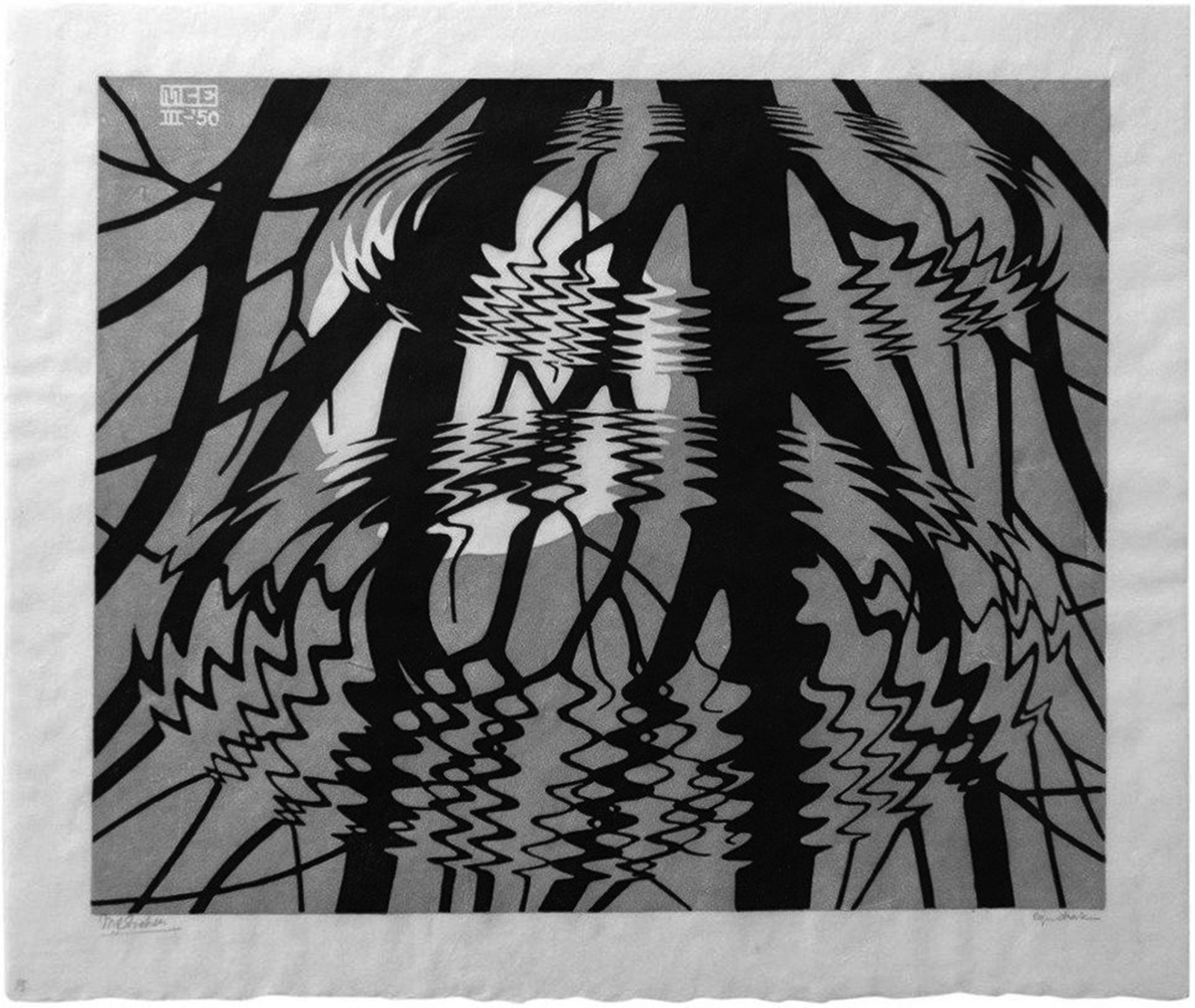

What type of research interest would benefit from adopting a CoPs perspective? In IR, CoPs and practice approaches more generally bring a fresh look to informal international politics, especially in a transnational context, thanks to their emphasis on how things actually happen in the everyday. To use an image by M. C. Escher (1950) (Figure 1), CoPs are the ripples that allow us to see the water.Footnote 118 Whereas some people might be interested in the moon and the trees, others will be keen to know more about the water and the stones (if they were stones) that were thrown and what story they (and the artist) tell.

Figure 1. M. C. Escher's Rippled Surface.

Source: © 2021 The M. C. Escher Company, the Netherlands. All rights reserved. Used by permission. See: {www.mcescher.com}.

As shown in empirical illustrations above, a CoPs perspective supplements and subverts institutional analysis of formal organisations. CoPs are a way to (literally) inject life into abstract forms, capturing the evolution of informal politics before it is codified. This is particularly relevant at a time when security and economic relations are ‘no longer characterized predominantly by formal organizational structures (if they have ever been)’.Footnote 119 A different rationale applies to the added value of CoPs vis-à-vis network analysis. While CoPs share with networks the capacity to summarise informal links, they emphasise what happens inside the group and to the endeavour that brought the group together in the first place. This does not necessarily lead to any broad generalisation, like network analysis tends to do, but opens up a conversation about the broad picture that local developments contribute to paint. Moreover, CoPs improve on tools generally employed by scholars interested in epistemic and security communities, suggesting ways to contextualise the specific practices and related effects in relation to science and security.

This approach to CoPs is valuable also beyond IR, in fact, and can lead to many interesting conversations. For instance, a specificity of IR, compared to other disciplines having engaged with CoPs such as Management and Social Policy, is the more prominent role of borders and a research interest in assessing how borders interact with political practices. Transnational CoPs represent the framework within which the vast majority of existing IR analyses of CoPs is situated, as in Adler's analysis of NATO's expansion and in Sondarjee's examination of how the World Bank came to include NGOs in its policymaking practices.Footnote 120 At the same time, CoPs also create borders, as Hofius forcefully shows in the case of EU diplomats in Ukraine, acting simultaneously as boundary spanners and boundary drawers.Footnote 121

As other disciplines also grapple with practices of inclusion and exclusion, these findings are likely to resonate and contribute to illuminate contexts other than international politics. Moreover, the added value of an IR CoPs framework extends beyond borders, to include issues such as materiality and the role of artefact, the importance of power, the nexus between practices and between CoPs, to name but a few. A CoP perspective has much to contribute to IR – and beyond.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank all interviewed practitioners for their generosity in sharing their time, experience, and knowledge. They are all in part co-authors of this article (but any mistakes remain mine). I also thank all colleagues with whom I have shared ideas and from whose comments I have benefited in a large number of occasions, including two very useful reviewers – may the conversation continue!