Introduction

From the mid-second millennium bc, the Mediterranean was the hub of intense cultural and economic transactions. During the Early Iron Age and the Orientalizing period (c. 1200–500 bc), it was dominated by the Greeks and Levantines. Coinciding with the increasingly expansionist commercial policy of Tyre in the ninth century bc, the Phoenicians looked for new trade opportunities, especially in metals, namely iron, silver, and tin (Aubet, Reference Aubet, López-Ruiz and Doak2019; López-Ruiz, Reference López-Ruiz2021). By the eighth–seventh centuries bc, they had established numerous outposts in the Western Mediterranean, including the Balearic Islands and along the Atlantic coasts of the Iberian Peninsula and north-western Africa (Dietler & López-Ruiz, Reference Dietler and López-Ruiz2009a). It is generally understood that such commercial interactions led local peoples to adopt urban and centralized political systems, and commodity-based or prestige-good economies, typical of the Eastern Mediterranean (Aubet, Reference Aubet2001).

Research has preferentially centred on the earliest Phoenician ‘contact zones’ around coastal outposts (Arruda, Reference Arruda2000; Aubet, Reference Aubet2001) and on those belonging to the later so-called Punic period (González-Ruibal, Reference González-Ruibal2006). Cross-cultural dynamics in the uncolonized mainland settings are far less well known. Recent fieldwork in inland Iberia is yielding increasing evidence of the exploitation of sought-after metals, and of the integration of rural communities into long- and short-distance exchange networks at least since the Late Bronze Age (Vilaça, Reference Vilaça and García-Bellido2011; Rodríguez-Díaz et al., Reference Rodríguez-Díaz, Pavón-Soldevila and Duque-Espino2019). Such societies were often assumed to be isolated and stagnant, seen as providers of raw materials or passive recipients of sporadic, Mediterranean imports, and typically envisaged as aristocratic societies based on prestige-goods economies (Almagro-Gorbea et al., Reference Almagro-Gorbea, Arroyo, Corbí, Marín and Torres2009). This is beginning to change, with some scholars advocating the active role of such communities (e.g. Vilaça, Reference Vilaça, Aubet and Pau2013), but the impact of such interactions remains ill-defined.

The discovery of unique vitreous imports at a seventh-century bc rural settlement in central Spain contributes substantially to this complex discussion. These unprecedented findings indicate that inland communities were not as isolated as once thought. They point to the transmission of esoteric know-how and an awareness of symbolism (at least to a degree), attesting to the transcultural hybridity that characterizes the orientalizing phenomenon (van Dommelen, Reference van Dommelen1997; Dietler & López-Ruiz, Reference Dietler, López-Ruiz, Dietler and López-Ruiz2009b; Hodos, Reference Hodos2020). The Phoenician footprint in western and inland Iberia should thus not be considered as merely representing a demand for ostentatious objects by local aristocrats.

The Site of Cerro de San Vicente

The Early Iron Age (900–400 bc) site of Cerro de San Vicente (CSV hereafter) in Salamanca lies in the highlands of central Iberia, an area rich in metal ores, especially tin and iron. It is sited at a strategic point on several long-distance routes, such as the south–north ‘Vía de la Plata’ that crosses western Iberia and others connecting the Central Plateau to the east with the Portuguese Beira and the Atlantic coast to the west (Figure 1a). It was a long-lived walled settlement built of mudbrick, inhabited by a few hundred villagers who lived in scattered roundhouses (Blanco-González et al., Reference Blanco-González, Alario and Macarro2017). The open spaces between the houses contained domestic refuse dumps (ashy middens) and small ancillary structures such as storage buildings, pens, and silos (Figure 1c–d). Excavations in 2017–2021 focused on its later occupation, when houses were arranged in compounds. On CSV's uppermost plateau (Figure 1b), one such compound (600 m2) was excavated, revealing roundhouses aggregated around a communal patio. The centre of this compound was occupied by several granaries, rectangular religious buildings (Buildings 3 and 7), and was dominated by House 1 (Blanco-González et al., Reference Blanco-González, Padilla-Fernández, Alario-García, Macarro-Alcalde, Alarcón and Martín-Seijo2022, Reference Blanco-González, Padilla-Fernández, Alario-García, Macarro-Alcalde, Dorado-Alejos and Pazos-García2023a, Reference Blanco-González, Padilla-Fernández and Dorado-Alejos2023b).

Figure 1. a: location of Cerro de San Vicente (1), Tell el-Amarna (2), and Abydos (3) (base map: Natural Earth); b: aerial view of the site of Cerro de San Vicente, with the excavated sector highlighted in red; c: overhead of the excavated sector in 2021; d: Buildings 3 and 7 in 2022.

House 1 was a remarkable roundhouse, as indicated by its ritualized destruction and its mudbrick furnishings and contents. It was filled with the mudbricks from its walls after a violent and purposeful conflagration that took place in c. 650–575 bc (García-Redondo et al., Reference García-Redondo, Calvo-Rathert, Carrancho, Goguitchaichvili, Iriarte and Blanco-González2021). Instead of the single bench common in other houses, it contained two continuous benches (over 3 m long) that could accommodate twenty people, a trampled-earth floor periodically refurbished and covered with matting, and a central fireplace unparalleled in the region with an ox-hide-shaped plan echoing Tartessian examples and much larger than the ordinary rectangular hearths. The assemblage from House 1 included numerous quern fragments (c. forty pieces representing a minimum of fifteen querns), an unusually large quantity of local fine wares for drinking (over 150 bowls)—some painted with orientalizing motifs such as palmettes, stars, or lotus flowers—plus imported objects, including Phoenician red slip ware and Egyptian vitreous items. This suggests that House 1 hosted extensive commensal activities and was probably used as a meeting hall.

Building 3 was a rectangular mudbrick structure measuring 3 × 5 m, its entrance oriented on the summer solstice sunrise (Figure 1c–d). Building 7 was similar, but smaller (3.2 × 2.9 m), opening onto the central compound, as do the remaining structures (Figure 1c); it yielded two spindle-whorls made of bone (indicating a high-quality and specialized craft, as opposed to the more commonplace ceramic) and a pair of antler horse bits, the latter indicative of aristocratic equestrian habits in this region. This sector is interpreted as representing the coexistence and maintenance of household, artisan, and prestige elements, as well as commensal ceremonies and activities devoted to the spiritual maintenance of the household and its visitors (Blanco-González et al., Reference Blanco-González, Padilla-Fernández, Alario-García, Macarro-Alcalde, Dorado-Alejos and Pazos-García2023a, Reference Blanco-González, Padilla-Fernández and Dorado-Alejos2023b).

Eight vitreous items were recovered in 2017 and 2021 from House 1 and its adjoining middens (Items 1, 3, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 14). The context suggests that they were used and discarded in a domestic and liturgical milieu, swept or thrown away and preserved in ashy dumps or trapped in the fills of House 1 and Building 3. Despite not having been recovered from a closed context, their discard can be dated confidently to before the sealing of these structures. Six further items were found in 2022 in and around Building 3, as well as in the fill of Building 7 (Items 2, 4, 5, 8, 12, 13). Those from inside Building 3 were intentionally deposited within the mud strata from the mudbrick walls that sealed the building after its desertion. Such a practice was widespread in contemporary sites and may be regarded as the ritual demise of this cultic building. The abandonment of these structures appears to coincide with the ritual conflagration of House 1 in the late seventh century bc.

The inhabitants of CSV practised agriculture and husbandry. They were also engaged in metallurgical and probably mining activities (Blanco-González et al., Reference Blanco-González, Padilla-Fernández, Alario-García, Macarro-Alcalde, Dorado-Alejos and Pazos-García2023a). Tools and by-products of bronze smelting, i.e crucibles and slags, are relatively abundant on the site compared to other contemporary settlements.

The Vitreous Assemblage

The analyses detailed below show that most glassy items from CSV are faience, an artificial vitreous material (Friedman, Reference Friedman and Friedman1998; Nicholson, Reference Nicholson and Wendrich2009; Henderson, Reference Henderson2013). In antiquity, it was a low-cost but highly-prized material, which served to make a variety of artefacts, including amulets, scarabs, beads, rings, figurines, and vessels (e.g. Pinch, Reference Pinch1993; Friedman, Reference Friedman and Friedman1998; Caubet & Pierrat-Bonnefois, Reference Caubet and Pierrat-Bonnefois2005).

The Artefacts

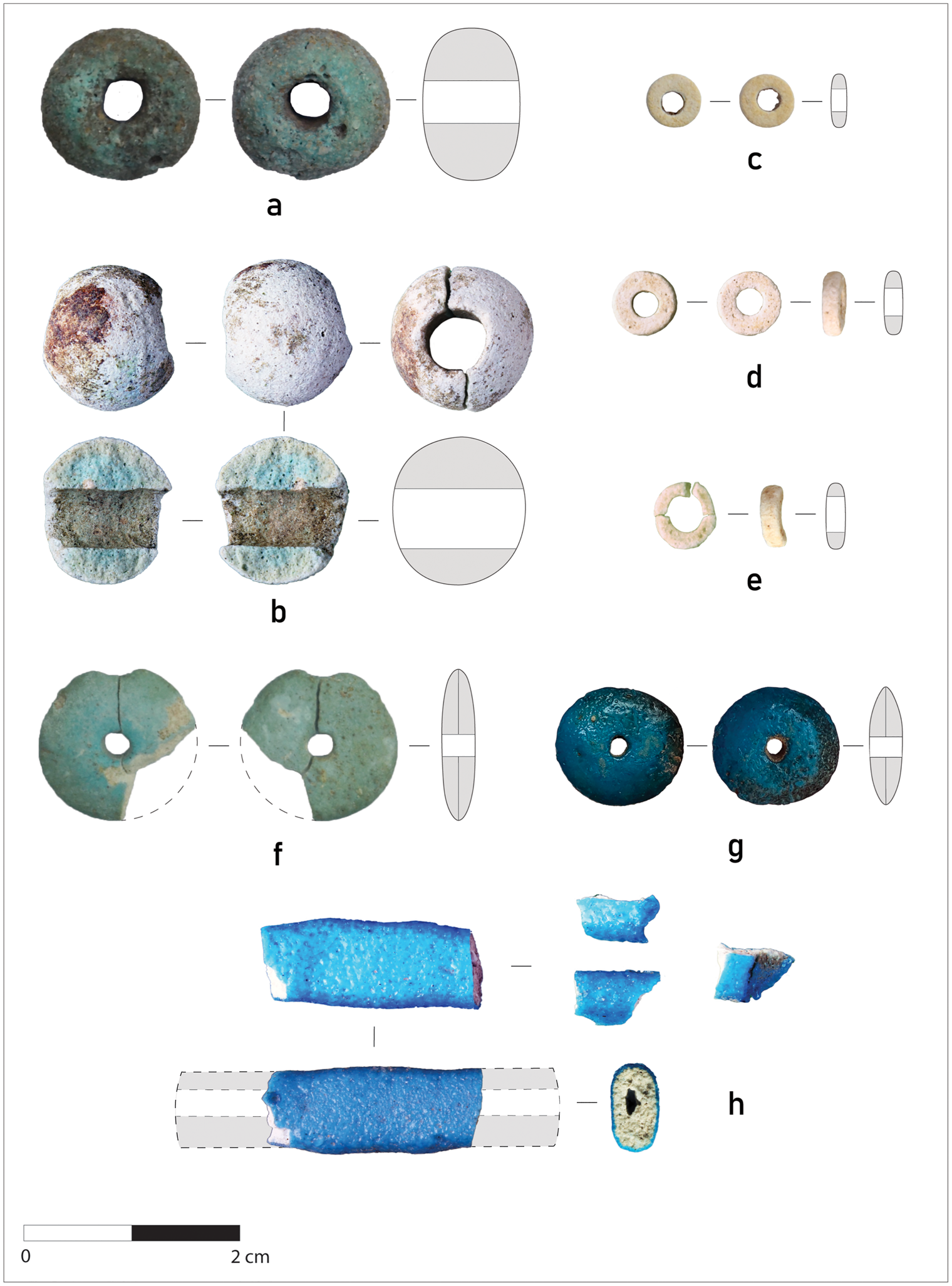

Faience beads (Items 1–8)

The eight faience beads are morphologically varied (Table 1). Ancient beads are generally difficult to date, but the types represented here were common in ancient Egypt from the Middle Kingdom (end of the third–beginning of the second millennium bc) onwards. Similar beads have been found in New Kingdom sites (c. 1500–1000 bc) devoted to Hathor, combined with amulets and other elements in necklaces or bracelets used as jewellery or votive elements (Pinch, Reference Pinch1993: 265–69, 276–77). These beads are frequent throughout the Mediterranean basin and were in high demand (Ingram, Reference Ingram2005). In the Iberian Peninsula, beads such as those recovered at CSV have been found in the Balearic Islands (e.g. Lull et al., Reference Lull, Micó, Rihuete and Risch1999: pl. 57b), on Phoenicians sites on the eastern Iberian coast (e.g. González-Prats, Reference González-Prats1990: 92, fig. 58, Reference González-Prats and González-Prats2014; Martínez-Mira & Vilaplana-Ortego, Reference Martínez-Mira, Vilaplana-Ortego and Lorrio2014), on southern sites in the area of Murcia, Almeria, and Granada (e.g. Lorrio, Reference Lorrio2008: 179–87), and in Portugal (Santos et al., Reference Santos, Antunes, Grilo, de Deus, Pérez and Romero2009; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Barrulas, Margarida-Arruda, Barbosa, Vandenabeele and Mirão, &2022; Vilaça & Gil, Reference Vilaça, Gil and Garrido-Anguita2023). Evidence of their presence on indigenous sites in the northern half of Iberia, on the other hand, hardly exists.

Table 1. Description of the eight faience beads (Items 1–8).

Figure 2. Faience beads. a: spheric bead (Item 1); b: spheric bead (Item 2); c: small barrel disc bead (Item 3); d: small barrel disc bead (Item 4); e: broken small barrel disc bead (Item 5); f: fragments of a disc bead (Item 6); g: disc bead (Item 7); h: cylindrical flat bead (Item 8).

Faience sherd (Item 9)

This sherd is 41 mm wide, 51 mm high, 11 mm thick at the top, and 15 mm thick at the bottom where the vessel starts to widen towards the base (Figure 3). Both sides are bright blue and have motifs painted in black manganese, recalling Egyptian ‘marsh bowls’. These shallow open vessels of blue and blue-green faience appeared in the Middle Kingdom and became popular in the early Eighteenth Dynasty (c. 1550/1549–1292 bc). They range from 10 to 40 cm in diameter, but most are comparable to the reconstruction proposed for our sherd, i.e. 15–21 cm in diameter and 4–8 cm high (Figure 3d–f). The painted decoration combines linear designs with a highly symmetrical, radial organization. The interior is usually composed of lotus and papyrus flowers, as well as fishes and other Nilotic elements, and the exterior exhibits the petals and sepals of an open lotus. This kind of bowl is common in religious settings, in shrines dedicated to Hathor or related goddesses, and in funerary contexts, but are rare in domestic contexts. Their decoration and contents—water, wine or milk, oils, perfumes, food offerings, and flowers—are related to fertility, rebirth, and regeneration. The blue colour connects these vessels to Hathor, Lady of Turquoise (Pinch, Reference Pinch1993: 308–15; Allen, Reference Allen and Roehrig2005). In mining sites such as Serabit el-Khadim (Sinai, Egypt), Hathor was revered as the protector of mines.

Figure 3. Pottery sherd of a manganese-painted faience ‘marsh bowl’ (Item 9). Views (left) and reconstruction (right). a: interior; b: exterior; c: section; d: reconstructed section; e: interior; f: exterior.

During the late New Kingdom, another kind of vessel appeared in domestic and funerary contexts in Egypt, as well as in indigenous sites and Egyptian garrisons in the Levant (Peltenburg, Reference Peltenburg, Braun-Holzinger and Matthäus2002). Such so-called ‘common bowls’ are smaller, deeper, rounder, and only decorated on the inside. It is unclear whether both types of bowl were exported from Egypt or were manufactured locally elsewhere, perhaps by Egyptian artisans (McGovern et al., Reference McGovern, Fleming and Swann1993). Be that as it may, their Egyptian and Hathor-related symbolism is beyond doubt and indicates the presence and importance of these products outside Egypt. In the Bronze Age and Iron Age, ‘common bowls’ are known in Cyprus, where Hathor had an important following, especially around copper exploitation (Peltenburg, Reference Peltenburg2007; Carbillet, Reference Carbillet2011). Remarkably, the vessel from CSV is decorated on both sides, resembling the earlier New Kingdom ‘marsh bowls’.

Amulet featuring a Hathor mask (Item 10)

This object, 6.5 mm wide, 8 mm high, and 2 mm thick, has an intense blue colour with specks of darker blue (Figure 4a). Hathor is represented as a cow with a distinctive looped hairstyle, with heavy tresses framing the face and falling on either side of the neck, ending in rolls (black lines are added to Figure 4a to make this clear). A podium (missing) is likely to have been present on the head. This artefact, thought to be a pendant, was meant to be worn as an amulet on a necklace or a bracelet and was probably pierced or fitted with loops.

Figure 4. Faience objects. a: small Hathor mask (Item 10); b: figurine fragment (Item 11); c: faience inlay (Item 12), the area with remains of the gold thread is marked with the red box and it can be seen in more detail in the enlarged image indicated by the red line; d: unidentified faience piece (Item 13).

In ancient Egypt, Hathor mask amulets made of stone, faience, glazed steatite, metal, or gold are known from all periods. Those resembling the amulet from CSV are widespread from the end of the Middle Kingdom and throughout the New Kingdom. Together with the moulds to manufacture them, they were particularly frequent on sites devoted to the goddess Hathor. They were, in general, 20 to 60 mm high and poorly made (Pinch, Reference Pinch1993: 135–59). Pendants comparable to our Iberian specimen also appear along the Syro-Palestinian coast (Hermann, Reference Hermann1994). In the Eastern Mediterranean, examples made of gold have been found in Cyprus (Carbillet, Reference Carbillet2011). Unlike objects featuring Hathor or related goddesses, such as plaques showing a cow in profile, Hathor masks are few in the Western Mediterranean. Only one faience amulet is known from southern Iberia (at Alcalá del Río, Seville, eighth–seventh centuries bc; García-Martinez, Reference García-Martínez2001: 108, 14.01, pls. IV, XV); it is larger and different from the amulet found at CSV. A gold exemplar was also recovered from Carthage (Vercoutter, Reference Vercoutter1945: pl. XXIV, no. 898–900).

Fragment, possibly from a figurine (Item 11)

This piece is 16 mm wide, 17 mm high, and 77 mm thick, with well-preserved blue colour (Figure 4b). It might have formed part of a small zoomorphic figurine. Items made of bright turquoise-blue faience are found in ancient Egyptian contexts in all periods. Figurines of cows related to Hathor are also common in New Kingdom sites (Pinch, Reference Pinch1993: 160–62). In the Iberian Peninsula, faience figurines are rarer than other elements such as amulets.

Faience inlay (Item 12)

This item, 28 cm wide, 45 mm long, and 5 mm thick, and featuring traces of gold leaf, is likely to be an inlay (Figure 4c). The back is bevelled, presumably to fit the piece onto an object. The faience paste is unusually hardened and is reddish in colour, maybe due to the application of some adhesive. This inlay is likely to correspond to the lower part of the looped hairstyle of the goddess Hathor. Two fine layers of gold leaf were applied directly onto the piece to delineate the loop and its edge (Figure 4c, top right).

Unidentified element (Item 13)

This vitreous piece, 9 mm thick, has a glazed surface 17 mm wide (maximum). Its surface is flat, and it seems to be the base of a portable object (Figure 4d).

Amorphous glass flake (Item 14)

This chipped fragment of vitreous material measures 19.0 × 16.5 mm (Figure 5). No parallels are known; glass beads are frequent in Iberia, but this large, much broken piece is unmatched.

Figure 5. Chipped fragment of glass paste (Item 14).

Technological Analysis

Ancient faience is a non-clay-based synthetic material obtained from a mixture of silica (quartz), alkali (soda), and lime, ingredients which react together during firing (Friedman, Reference Friedman and Friedman1998; Nicholson, Reference Nicholson and Wendrich2009; Henderson, Reference Henderson2013). Different recipes are known, resulting in varying compositions (Tite et al., Reference Tite, Freestone and Bimson1983; Vandiver, Reference Vandiver, Kaczmarczyk and Hedges1983; Nicholson & Peltenburg, Reference Nicholson, Peltenburg, Nicholson and Shaw2000). The paste obtained was then shaped by moulding or modelling. Copper gives the faience its blue-green colour. Faience was first produced in the Near East and Egypt in the late fourth millennium bc and demand increased up to Roman times. Outside these areas, faience products with Egyptian iconography or Egyptian inspiration are known across the Mediterranean and produced on its eastern coasts. In the Western Mediterranean, faience workshops appeared by the mid-first millennium bc, and their products differed qualitatively from their third–second millennium bc Egyptian counterparts (López-Grande et al., Reference López-Grande, Vélazquez, Fernández and Mezquida-Ortí2014). Glass has a more solid texture, in which the siliceous material is perfectly homogenized (Henderson, Reference Henderson2013) through the optimum temperature reached by the silica sand (SiO2), the sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), and the added limestone (CaCO3), and the few voids identified in its matrix result from the slow cooling process.

Here, macroscopic observation (Figure 6) and microphotographs (Figures 7 and 8) of the CSV items are supported by chemical characterization (Figure 9). The analyses confirm that they are all faience except for one glass fragment (Item 14), all of which are most likely to have been produced in Egypt. The results are comparable to samples from the New Kingdom workshops at Tell el-Amarna in Middle Egypt (c. 1550–1050 bc; Shortland, Reference Shortland2000; Nicholson, Reference Nicholson2007). The oldest examples of Egyptian vitreous objects in Spain are eight glass paste beads found at the eighth-century bc site of Fuente Alamo (Murcia), also resembling examples from Tell-el-Amarna (Mata-Carriazo, Reference Mata-Carriazo and Menéndez-Pidal1947). Further parallels exist among the beads from Boliche (Martínez-Mira & Vilaplana-Ortego, Reference Martínez-Mira, Vilaplana-Ortego and Lorrio2014) and La Fonteta (González-Prats, Reference González-Prats and González-Prats2014) on the south-eastern Spanish coast.

Figure 6. Photomicrographs of faience (a–j) and glass (k–l) objects from CSV. a: Item 11; b–d: Item 9; e: rounded quartz in the matrix of Item 9; f; details of the surface and matrix of Item 9; g: surface of Item 7; h: surface of Item 11; i–j: surface of Item 9; k–l: surface of glass Item 14.

Figure 7. Scanning electron microscope microphotographs. a–b: faience (Item 9); c–d: glass (Item 14).

Figure 8. Scanning electron microscope microphotographs of the faience inlay (Item 12). Spectrum 1 is a specific point represented by a cross. Spectra 2 to 6 are wider areas of analysis represented as a square.

Figure 9. Chemical results of vitreous items obtained by pXRF. Principal component analysis of the elements Ca, Al, Mg, K in the sample was compared with published results from sites in the Central Mediterranean and Egypt. Numbers correspond to faience (Items 1–13) and glass paste (Item 14) samples from CSV.

The composition of the faience items is quite homogeneous. Macrophotographs (see Supplementary Material S1) show the presence of small quartz dispersed in the matrix, with a high sphericity and isometry (Figure 6a–e) (Nicholson & Peltenburg, Reference Nicholson, Peltenburg, Nicholson and Shaw2000). Moreover, the presence of tiny charcoal remains (<0.1 mm) regularly scattered in the matrix indicate the use of carbonized plant ash to obtain sodium oxide necessary to achieve an optimum piece at lower temperatures (Figure 6f–j). The piece of glass (Item 14) is different, far more cohesive and has fewer voids (Figure 6k–l).

The microphotographs (Figure 9, Supplementary Material S2) and two samples selected for microstructural analysis show obvious differences in composition, indicating that, although made from very similar materials, the artefacts were manufactured in different ways, related to the temperatures reached in the production process (Tite et al., Reference Tite, Freestone, Meeks, Bimson, Olin and Franklin1982; Taber, Reference Taber2017). Glass requires higher temperatures to obtain a more cohesive structure (Figure 7k–l and Figures 8 and 9).

We employed Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) (Supplementary Material S3) to characterize the materials and their mineralogy. The FTIR spectra of the faience samples and the glass item (Supplementary Figures S1–S14) show typical quartz absorption bands (1084, 796, 779, 694 cm-1), but with a broad peak at 1090–1030 cm-1, which also indicates the presence of glass, linked with an amorphous siliceous phase (Moenke, Reference Moenke and Farmer1974) identified in other artefacts of faience analysed by this procedure (Toffolo et al., Reference Toffolo, Klein, Elbaum, Aja, Master and Boaretto2013; Liyahu-Behar, Reference Liyahu-Behar2017). Peaks related to the presence of copper compounds have been identified in 1160, 454–442, and 515–11 cm-1, related to the presence of Egyptian blue, a calcium-copper silicate analogue of the mineral cuprorivaite ((Ca,Cu)Si4O10; Eastaugh et al., Reference Eastaugh, Walsh, Chaplin and Siddall2008).

The microanalysis of the inlay (Item 12) shows the use of gold alloyed with less than twenty per cent silver (Figure 8, Supplementary Table S2). This alloy (electrum) lightens the colour of the gold, with more yellowish tones (Scheel, Reference Scheel1989: 15–16). Although silver and gold are complementary metals, their alloys maintain high solidification intervals (Montero & Rovira, Reference Montero and Rovira1991: 8). Their use may represent an improvement in the mechanical and physical resistance of the metal (Tylecote, Reference Tylecote1987), something that the metalworkers who made the piece certainly knew. Such alloys existed naturally in Nubia and were used in jewellery and other objects, such as vases or statues.

The result of chemical characterization by X-ray fluorescence (Supplementary Material S4) were compared with other datasets obtained from several Central Mediterranean areas (Arletti et al., Reference Arletti, Maiorano, Ferrari, Vezzalini and Quartieri2010, Reference Arletti, Ferrari and Vezzalini2012; Panighello et al., Reference Panighello, Orsega, van Elteren and Selih2012) and Egypt (Nicholson & Peltenburg, Reference Nicholson, Peltenburg, Nicholson and Shaw2000; Yunhui, Reference Yunhui2000; Shortland & Eremin, Reference Shortland and Eremin2006; Tite et al., Reference Tite, Manti and Shortland2007) (Figure 9). The samples show the highest values for Si (31.04 per cent), followed by Cu (1.64 per cent), due to the higher presence of Cu on the analysed surfaces (Figure 7). Other elements are represented by percentages between 0.1 and c. 1 per cent, such as Al (0.54 per cent), Fe (0.24 per cent), and Ca (1.07 per cent), K (0.62 per cent), Cl (0.4 per cent), S (0.32 per cent), and Mg (0.31 per cent). No values or very low values of Ba, Sb, Sn, Cd, Pd, Ag, Zr, Sr, As, Se, Pb, W, Zn, Mn, V, Ti, and P were detected (Supplementary Material Table S1). The general composition of the samples allows for the identification of two groups based on their Ca values, i.e. more than or less than five per cent. The first group (faience) is made up of samples from Items 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 12, 13, and 14 (surface), and Items 3, 6, 9, and 11 (matrix and surface), with no obvious differences linked to the colours. A second group is represented by one sample of glass (Item 14). When comparing these groupings with published datasets, the first cluster (faience) fits in with the samples from Tell-el-Amarna and Abydos (<5 per cent Ca). The glass sherd of the second group is related to samples linked to productions from Tell-el-Amarna, Malkata, or Nuzi (>5 per cent Ca). Copper contents varied widely within the pieces, being higher on their surfaces (values from 3.25 to 4.18 per cent), than in their matrices (values < 0.5 per cent) (Figure 7).

Although there may be a degree of statistical uncertainty in the data, it seems clear that the groupings detected are directly related to the production centres mentioned previously, independently of the analytical procedure used and any deviations from them. For this reason, we consider the results to be reliable indicators of the origin of our artefacts.

Discussion

Our assemblage of vitreous materials can be divided into faience pieces (Items 1–13) from Abydos/Tell el-Amarna and a single glass flake (Item 14) from Tell el-Amarna. This technologically homogeneous group appears to originate in Eastern rather than Central Mediterranean workshops. The objects’ iconography suggests they belong to Middle and New Kingdom Egyptian production contexts and use, likely to be related to the goddess Hathor. Furthermore, there is ample scholarly consensus that Egyptian-like objects transported by the Phoenicians and found in Iberia on sites dating from the eighth/seventh to the fifth centuries bc were manufactured in Egypt (e.g. Vercoutter, Reference Vercoutter1945: 282, 341; Padró i Parcerisa, Reference Padró i Parcerisa1980–1983, Reference Padró i Parcerisa1995; López-Grande et al., Reference López-Grande, Vélazquez, Fernández and Mezquida-Ortí2014). Faience objects from Extremadura in south-western inland Iberia are of similar dates (Almagro-Gorbea et al., Reference Almagro-Gorbea, Arroyo, Corbí, Marín and Torres2009). We thus believe that the pieces from CSV could have been produced in Egypt and exported to the Levant or another Eastern Mediterranean area (Shortland et al., Reference Shortland, Nicholson, Jackson and Shortland2001) before reaching Iberia.

The spread of Egyptian motifs, conventions, deities, and rituals is evident from a range of material and textual evidence in the Eastern Mediterranean since even before the Late Bronze Age. The Egyptian presence in Syria-Palestine was particularly significant from the beginning of the New Kingdom; increasing military activity resulted in numerous Egyptian or Egyptian-like artefacts (beads, amulets, scarabs, and other articles) being found among the elite and sub-elite, especially between c. 1300 and 1100 bc (Higginbotham, Reference Higginbotham2000; Feldman, Reference Feldman2002: 6–29). In addition, a resurgence of strong Egyptian influence in the southern Levant during the Late Period (seventh–fourth centuries bc) is attested by intense cultural and economic interaction between Egypt and the Mediterranean. This led to an increase in the circulation of Egyptian objects and the creation of new faience production centres (Caubet & Pierrat-Bonnefois, Reference Caubet and Pierrat-Bonnefois2005). The Phoenician city of Byblos, and later Tyre, played a key role as a meeting point between Egypt and other Eastern Mediterranean areas. Furthermore, the Egyptian deity Hathor was particularly revered in the Levant (Hollis, Reference Hollis2009). Her role as the goddess of foreign lands, and protector of travellers and sailors, may help explain the prevalence and continuity of her cult in the Levant and other areas of the Eastern Mediterranean, as well as her assimilation to other local goddesses, such as Astarte or Anat.

How did Egyptian faience end up in a village as remote as CSV? Since the pieces were found in refuse dated to c. 600 bc, they probably ended up in this rural settlement in the interior of Iberia as long-lived valuables curated until the seventh century bc, many centuries after their manufacture. The beads, the Hathor mask pendant, the Hathor inlay piece, and liturgical ware may have initially been taken abroad as protection by travellers on their western voyages. The Hathor symbolism may also have contributed to the selection of these specific artefacts. This does not imply that they were not exchanged or given away when necessary. Such votive or apotropaic items were commonly deposited in Egyptian tombs or shrines dedicated to Hathor but, during the Egyptian Third Intermediate Period (c. 800–600 bc), many such religious and funerary contexts were plundered (Phillips, Reference Phillips and Orel1992), their contents dispersed, and Phoenician traders eventually acquired some of them. By the seventh century bc, the items from CSV were antiques that had circulated across the Mediterranean (Sherratt, Reference Sherratt, Bauer and Agbe-Davies2010; Ruiz-Gálvez, Reference Ruiz-Gálvez2013). At some point they may have been passed on as gifts exchanged through intermediaries or traded as commodities conveying a particular symbolic significance for local communities.

Faience amulets, scarabs, and beads abound in the Western Mediterranean basin, Ibiza (López-Grande et al., Reference López-Grande, Vélazquez, Fernández and Mezquida-Ortí2014), and on the Mediterranean coasts of Iberia. Examples are also known from southern Iberia, the Atlantic Iberian coast (Padró i Parcerisa, Reference Padró i Parcerisa1980–1983, Reference Padró i Parcerisa1995; Almagro-Gorbea et al., Reference Almagro-Gorbea, Arroyo, Corbí, Marín and Torres2009), and southern and central inland Portugal (Valério et al., Reference Valério, Araújo, Soares, Silva, Baptista and Mataloto2018; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Barrulas, Margarida-Arruda, Barbosa, Vandenabeele and Mirão, &2022; Vilaça & Gil, Reference Vilaça, Gil and Garrido-Anguita2023). Their distribution shows that some artefacts (e.g. scarabs) were more common than others, and not all Egyptian types are found in Iberia. No Egyptian objects had been identified in the northern half of Iberia before the finds from CSV.

As a goddess related to fertility, regeneration rituals, and to mining, Hathor may have been particularly attractive to Iberian communities. Elements directly or indirectly related to Hathor are well known in Iberia, especially in the seventh century bc, when several bronze figurines representing feminine deities with the characteristic Hathor hairstyle are documented. Scholars generally consider them to be Iberian products in an orientalizing style, imitating Near Eastern goddesses, such as Astarte, Anat, or Hathor. The nearest iconographic parallel for the CSV pendant and the inlay piece are three bronzes from El Berrueco (Salamanca) (Padró i Parcerisa, Reference Padró i Parcerisa, Berger, Clerc and Grimal1994; Jiménez-Ávila, Reference Jiménez-Ávila2002; Almagro-Gorbea et al., Reference Almagro-Gorbea, Arroyo, Corbí, Marín and Torres2009), although their context of use and meaning are unclear. The CSV finds, with their Hathor symbolic associations, most likely represented meaningful objects for this community. The assemblage is unique in Iberia regarding provenance, material, typology, and context. The faience bowl was connected to rituals conducted in cultic contexts in Egypt and the Near East. It conveyed distant mythological, religious, and ideological notions as well as esoteric materiality. Its aesthetic aspect would also have played a role (Sinclair, Reference Sinclair2012); when complete, the bowl must have been eye-catching, given its dazzling blue glaze (Peltenburg, Reference Peltenburg2007). Finally, Hathor's connection with mining could have been attractive to the inhabitants of CSV, who probably engaged in mining and metallurgy.

Conclusion

In this article, we have focused on the provenance, biography, and social context of an unprecedented assemblage of vitreous materials from a seventh-century bc domestic and ritual context excavated at CSV in central Iberia. The likely origin of the faience and glass objects is Egyptian, most probably from Tell-el-Amarna. We suggest that such valuable items were used by Iberian peoples who were fully aware of their liturgical meaning and who used such imports in cultic and everyday activities. The CSV artefacts provide new insights into the incorporation of Eastern Mediterranean beliefs and rituals in the interior of Early Iron Age Iberia and add to our current understandings of Phoenician–local interactions. They demonstrate that some allegedly marginal inland regions were connected with the Mediterranean via overland routes.

This connectivity may have been direct—i.e. with the Phoenicians or their intermediaries—or indirect, through shorter-distance interactions between coastal Iberian populations and the interior. CSV may also have been part of long-distance trade routes due to the region's wealth in iron and especially tin, metals which were in high demand by Eastern Mediterranean societies and probably exchanged for commodities or gifts. This socio-political framework, combined with the movement of raw materials, commodities, knowledge, and people across western Iberia (Almagro-Gorbea et al., Reference Almagro-Gorbea, Arroyo, Corbí, Marín and Torres2009) provides a context for the arrival in central Iberia of items manufactured some 6000 km away. Central Iberia was reached via the Tagus and the ‘Vía de la Plata’ and was also connected with Phoenician sites on the Atlantic coast, of which the northernmost outpost was Santa Olaia (Figueira da Foz, Portugal) (Arruda, Reference Arruda2005), 350 km from CSV. Within a broader western Iberian context, the pieces found at CSV raise important questions regarding their itineraries, intermediaries, circulation routes, final destination, and variations in value.

In most premodern societies, fluid and mutual interaction over vast distances is only viable if supported by alliances, kinship, and ritual. In this perspective, the original meaning of our artefacts—closely related to Hathor—can be better understood. The striking blue colour of such imports, their arcane nature, and the orientalizing motifs are likely to have made them very attractive. How local groups received or adapted exogeneous beliefs, rituals, and material culture may have varied, but the particularities of the assemblage recovered at CSV suggest that its occupants were aware of symbolic and ritual connotations. We contend that they consciously appropriated such outlandish materials and iconographic repertoires. The artefacts’ original meaning may have changed over time, being altered to adapt to autochthonous beliefs and customs, as attested by orientalizing features displayed in local pottery (Blanco-González et al., Reference Blanco-González, Padilla-Fernández and Dorado-Alejos2023b). The faience and glass assemblage from Cerro de San Vicente is thus seen as further testimony of the assimilation of Mediterranean symbolism, which was incorporated into transcultural hybrid practices.

Acknowledgements

Cristina Alario and Carlos Macarro were co-directors in the 2017, 2021, and 2022 fieldwork campaigns at CSV. The authors thank Prof. Marisa Ruiz-Gálvez, Prof. Martín Almagro-Gorbea, and Dr Javier Jimenez Ávila for advice, and Prof. Andrew Shortland for sending his book. This work was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science (research project ARQPARENT, PID2019-104349GA-I00). Analyses were conducted at the Archaeometry Laboratory ‘Antonio Arribas Palau’ of the University of Granada funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science (EQC2018-004880-P). Linda Chapon is funded by the European Union's Horizon 2020 Programme under Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 101026680. Funding for open access charge: Universidad de Granada/CBUA.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/eaa.2024.1.