As we reported in Chapter 3, most individuals are exposed to trauma at some point in their life. Yet lifetime posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) prevalence is only 1.3% to 8.8% in community epidemiological surveys of the general population (Atwoli et al., Reference Atwoli, Stein, Koenen and McLaughlin2015b). This discrepancy raises questions about the determinants of PTSD after trauma exposure. One line of research shows that PTSD prevalence is highest for traumas involving interpersonal violence (Breslau et al., Reference Breslau, Peterson and Schultz2008; Caramanica et al., Reference Caramanica, Brackbill, Stellman and Farfel2015; Fossion et al., Reference Fossion, Leys and Kempenaers2015). Another suggests that a history of prior trauma is a risk factor for subsequent PTSD, particularly any prior trauma involving interpersonal violence (Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Walsh, Uddin, Galea and Koenen2014; White et al., Reference White, Pearce and Morrison2015; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Summers, Dillon and Cougle2016). However, these studies did not examine prior traumas comprehensively, leaving numerous questions unanswered such as whether the special importance of prior traumas involving interpersonal violence is limited to personal victimization or includes witnessing violence (Atwoli et al., Reference Atwoli, Platt, Williams, Stein and Koenen2015a), and whether all types of prior traumas are equally important (Breslau et al., Reference Breslau, Peterson and Schultz2008; Breslau & Peterson, Reference Breslau and Peterson2010) or only those involving interpersonal violence (Cougle et al., Reference Cougle, Resnick and Kilpatrick2009). Likewise, it's also unclear whether re-exposure to similar traumas plays any role in the onset of subsequent PTSD (Green et al., Reference Green, Goodman and Krupnick2000; Nishith et al., Reference Nishith, Mechanic and Resick2000), and whether some prior traumas may instead inoculate against future PTSD by building resilience (Shiri et al., Reference Shiri, Wexler, Alkalay, Meiner and Kreitler2008; Palgi et al., Reference Palgi, Gelkopf and Berger2015). To address these assorted questions, we examined the associations of disaggregated trauma types and histories with PTSD in the large World Mental Health (WMH) sample.

Methods

The analyses focused on the 22 WMH surveys that assessed lifetime PTSD after random traumas, using the procedures described in Chapter 2. Logistic regression – with controls for surveys, respondent ages at both random trauma exposure and at interview, and for sex – was used to estimate associations of random trauma type and trauma history with PTSD. Logistic regression coefficients for random trauma types were scaled to have a sum of 0.0. As in other chapters, these coefficients and their design-based standard errors were exponentiated to create odds-ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The scaling of the logistic regression coefficients led to the ORs for trauma types having a product of 1.0 and to ORs significantly different from 1.0 being significantly different from the average PTSD odds across all trauma types. This model was then elaborated to include information about prior trauma exposure. In an effort to evaluate the strength of overall model fit, a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was calculated from each set of predicted probabilities (Zou et al., Reference Zou, O'Malley and Mauri2007) and area under the curve (AUC) computed to quantify overall prediction accuracy (Hanley & McNeil, Reference Hanley and McNeil1983). The method of replicated tenfold cross-validation with 20 replicates (i.e., 200 separate estimates of model coefficients) was used to correct for over-estimation of prediction accuracy when both estimating and evaluating models in a single sample (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Seaman, Wood, Royston and White2014).

Results

Trauma Prevalence and Trauma-Specific PTSD Prevalence

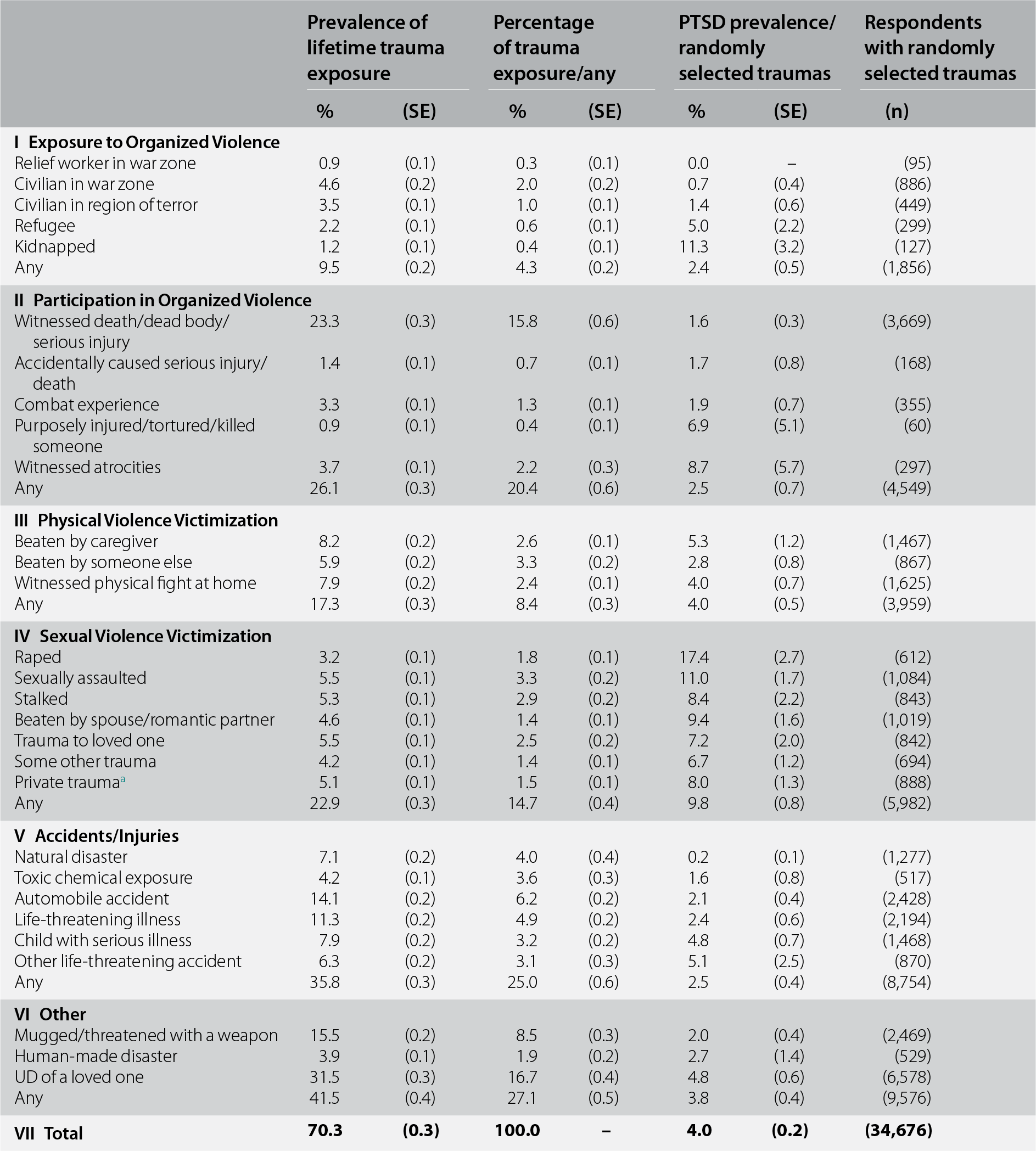

Exposure to lifetime traumas was reported by a weighted 70.3% of Part II respondents in the WMH sample considered in this analysis (n = 34,676). Mean number of lifetime exposures among those with any exposure to trauma was 4.5. As in Chapter 3, the most common traumas were unexpected death of loved one (16.7% of all exposures) and direct exposure to death or serious injury (15.8%) (see Table 9.1). Accidents/injuries were the most common trauma group (25.0%) followed by traumas associated with participating in organized violence (20.4%).

Table 9.1 Lifetime prevalence of exposure to specific trauma types, distribution of randomly selected trauma types among those with any lifetime trauma exposure, and associations of randomly selected trauma types with DSM-IV/CIDI PTSD across all WMH surveys (n = 34,676)

| Prevalence of lifetime trauma exposure | Percentage of trauma exposure/any | PTSD prevalence/randomly selected traumas | Respondents with randomly selected traumas | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (SE) | % | (SE) | % | (SE) | (n) | |

| I Exposure to Organized Violence | |||||||

| Relief worker in war zone | 0.9 | (0.1) | 0.3 | (0.1) | 0.0 | – | (95) |

| Civilian in war zone | 4.6 | (0.2) | 2.0 | (0.2) | 0.7 | (0.4) | (886) |

| Civilian in region of terror | 3.5 | (0.1) | 1.0 | (0.1) | 1.4 | (0.6) | (449) |

| Refugee | 2.2 | (0.1) | 0.6 | (0.1) | 5.0 | (2.2) | (299) |

| Kidnapped | 1.2 | (0.1) | 0.4 | (0.1) | 11.3 | (3.2) | (127) |

| Any | 9.5 | (0.2) | 4.3 | (0.2) | 2.4 | (0.5) | (1,856) |

| II Participation in Organized Violence | |||||||

| Witnessed death/dead body/serious injury | 23.3 | (0.3) | 15.8 | (0.6) | 1.6 | (0.3) | (3,669) |

| Accidentally caused serious injury/death | 1.4 | (0.1) | 0.7 | (0.1) | 1.7 | (0.8) | (168) |

| Combat experience | 3.3 | (0.1) | 1.3 | (0.1) | 1.9 | (0.7) | (355) |

| Purposely injured/tortured/killed someone | 0.9 | (0.1) | 0.4 | (0.1) | 6.9 | (5.1) | (60) |

| Witnessed atrocities | 3.7 | (0.1) | 2.2 | (0.3) | 8.7 | (5.7) | (297) |

| Any | 26.1 | (0.3) | 20.4 | (0.6) | 2.5 | (0.7) | (4,549) |

| III Physical Violence Victimization | |||||||

| Beaten by caregiver | 8.2 | (0.2) | 2.6 | (0.1) | 5.3 | (1.2) | (1,467) |

| Beaten by someone else | 5.9 | (0.2) | 3.3 | (0.2) | 2.8 | (0.8) | (867) |

| Witnessed physical fight at home | 7.9 | (0.2) | 2.4 | (0.1) | 4.0 | (0.7) | (1,625) |

| Any | 17.3 | (0.3) | 8.4 | (0.3) | 4.0 | (0.5) | (3,959) |

| IV Sexual Violence Victimization | |||||||

| Raped | 3.2 | (0.1) | 1.8 | (0.1) | 17.4 | (2.7) | (612) |

| Sexually assaulted | 5.5 | (0.1) | 3.3 | (0.2) | 11.0 | (1.7) | (1,084) |

| Stalked | 5.3 | (0.1) | 2.9 | (0.2) | 8.4 | (2.2) | (843) |

| Beaten by spouse/romantic partner | 4.6 | (0.1) | 1.4 | (0.1) | 9.4 | (1.6) | (1,019) |

| Trauma to loved one | 5.5 | (0.1) | 2.5 | (0.2) | 7.2 | (2.0) | (842) |

| Some other trauma | 4.2 | (0.1) | 1.4 | (0.1) | 6.7 | (1.2) | (694) |

| Private traumaa | 5.1 | (0.1) | 1.5 | (0.1) | 8.0 | (1.3) | (888) |

| Any | 22.9 | (0.3) | 14.7 | (0.4) | 9.8 | (0.8) | (5,982) |

| V Accidents/Injuries | |||||||

| Natural disaster | 7.1 | (0.2) | 4.0 | (0.4) | 0.2 | (0.1) | (1,277) |

| Toxic chemical exposure | 4.2 | (0.1) | 3.6 | (0.3) | 1.6 | (0.8) | (517) |

| Automobile accident | 14.1 | (0.2) | 6.2 | (0.2) | 2.1 | (0.4) | (2,428) |

| Life-threatening illness | 11.3 | (0.2) | 4.9 | (0.2) | 2.4 | (0.6) | (2,194) |

| Child with serious illness | 7.9 | (0.2) | 3.2 | (0.2) | 4.8 | (0.7) | (1,468) |

| Other life-threatening accident | 6.3 | (0.2) | 3.1 | (0.3) | 5.1 | (2.5) | (870) |

| Any | 35.8 | (0.3) | 25.0 | (0.6) | 2.5 | (0.4) | (8,754) |

| VI Other | |||||||

| Mugged/threatened with a weapon | 15.5 | (0.2) | 8.5 | (0.3) | 2.0 | (0.4) | (2,469) |

| Human-made disaster | 3.9 | (0.1) | 1.9 | (0.2) | 2.7 | (1.4) | (529) |

| UD of a loved one | 31.5 | (0.3) | 16.7 | (0.4) | 4.8 | (0.6) | (6,578) |

| Any | 41.5 | (0.4) | 27.1 | (0.5) | 3.8 | (0.4) | (9,576) |

| VII Total | 70.3 | (0.3) | 100.0 | – | 4.0 | (0.2) | (34,676) |

a A private event is a trauma that some individuals reported in response to a question asked at the very end of the trauma section that asked if they ever had some other very upsetting experience they did not tell us about already (and this includes in response to a prior open-ended question about “any other” trauma) because they were too embarrassed or upset to talk about it. Respondents were told, before they answered, that if they reported such a trauma we would not ask them anything about what it was, only about their age when the trauma happened.

PTSD occurred after a weighted 4.0% of random traumas. Being a relief worker is a war zone (0.3% of all traumas) was the only trauma type not associated with any PTSD cases in the sample. Significant variation in PTSD prevalence was found across the remaining 28 trauma types (χ227 = 237.1, p < 0.001), with highest weighted PTSD prevalence for rape (17.4%), kidnapped (11.3%), and other sexual assaults (11.0%) and lowest (other than for being a relief worker) for natural disasters (0.2%) and being a civilian in a war zone (0.7%) or region of terror (1.4%).

Differential Associations of Trauma Types with PTSD

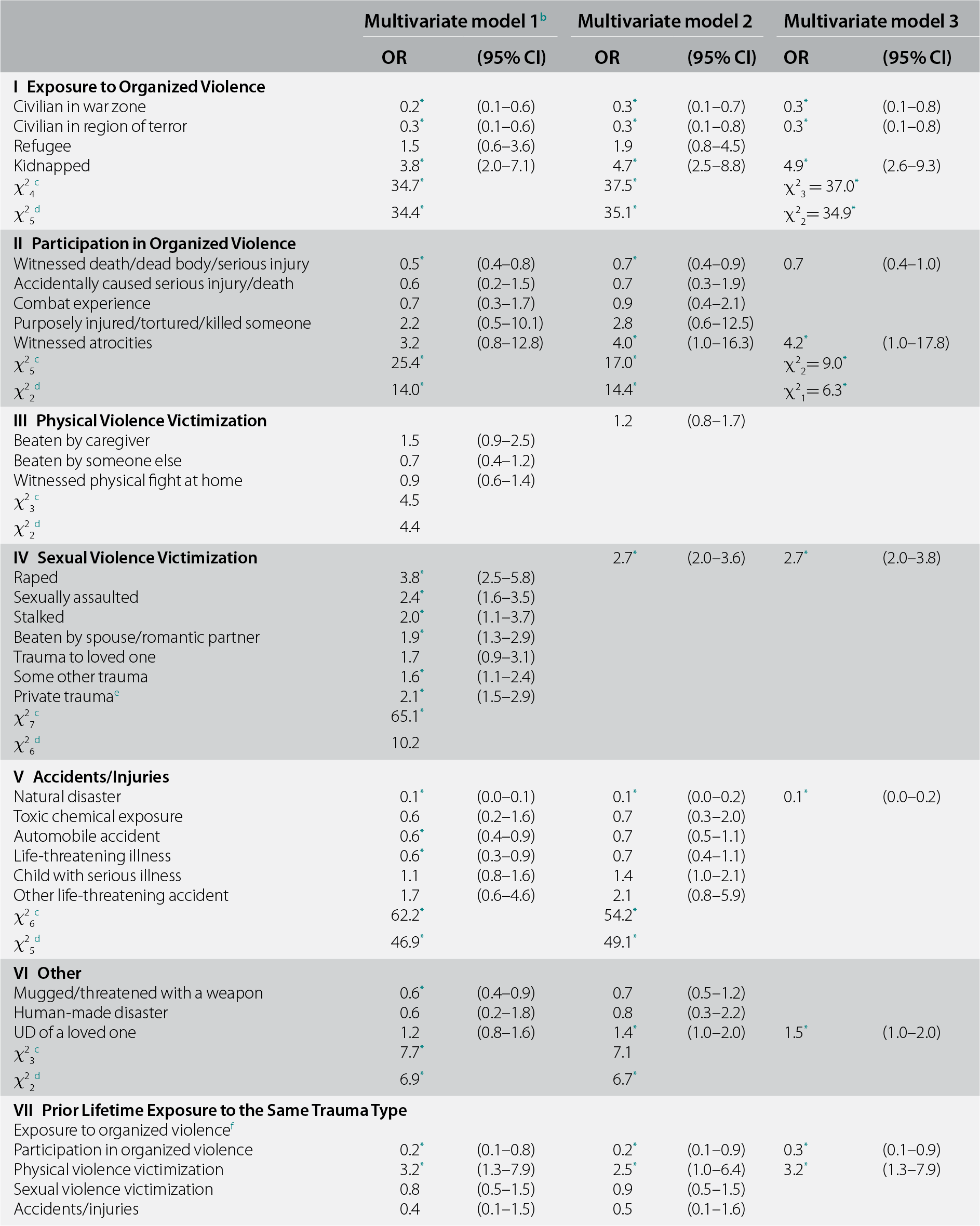

The first model (Model 1, Table 9.2) estimated relative odds of PTSD across random trauma types when controlling for prior same-type exposures. Given the rarity of prior same-type exposures, the latter were coded at the level of the six trauma groups described in Chapter 3, with all respondents having prior same-type exposures in a single group collapsed into a group-level measure. Only five of the six such group-level measures were analyzed, though, because too few respondents previously experienced same-type traumas involving exposure to organized violence for analysis.

Table 9.2 Associations of DSM-IV/CIDI PTSD associated with randomly selected trauma type and prior lifetime exposure of the same trauma type among people exposed to one or more lifetime traumas across all WMH surveys (n = 34,581)a

| Multivariate model 1b | Multivariate model 2 | Multivariate model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |

| I Exposure to Organized Violence | ||||||

| Civilian in war zone | 0.2* | (0.1–0.6) | 0.3* | (0.1–0.7) | 0.3* | (0.1–0.8) |

| Civilian in region of terror | 0.3* | (0.1–0.6) | 0.3* | (0.1–0.8) | 0.3* | (0.1–0.8) |

| Refugee | 1.5 | (0.6–3.6) | 1.9 | (0.8–4.5) | ||

| Kidnapped | 3.8* | (2.0–7.1) | 4.7* | (2.5–8.8) | 4.9* | (2.6–9.3) |

| χ24c | 34.7* | 37.5* | χ23 = 37.0* | |||

| χ25d | 34.4* | 35.1* | χ22= 34.9* | |||

| II Participation in Organized Violence | ||||||

| Witnessed death/dead body/serious injury | 0.5* | (0.4–0.8) | 0.7* | (0.4–0.9) | 0.7 | (0.4–1.0) |

| Accidentally caused serious injury/death | 0.6 | (0.2–1.5) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.9) | ||

| Combat experience | 0.7 | (0.3–1.7) | 0.9 | (0.4–2.1) | ||

| Purposely injured/tortured/killed someone | 2.2 | (0.5–10.1) | 2.8 | (0.6–12.5) | ||

| Witnessed atrocities | 3.2 | (0.8–12.8) | 4.0* | (1.0–16.3) | 4.2* | (1.0–17.8) |

| χ25c | 25.4* | 17.0* | χ22= 9.0* | |||

| χ22d | 14.0* | 14.4* | χ21= 6.3* | |||

| III Physical Violence Victimization | 1.2 | (0.8–1.7) | ||||

| Beaten by caregiver | 1.5 | (0.9–2.5) | ||||

| Beaten by someone else | 0.7 | (0.4–1.2) | ||||

| Witnessed physical fight at home | 0.9 | (0.6–1.4) | ||||

| χ23c | 4.5 | |||||

| χ22d | 4.4 | |||||

| IV Sexual Violence Victimization | 2.7* | (2.0–3.6) | 2.7* | (2.0–3.8) | ||

| Raped | 3.8* | (2.5–5.8) | ||||

| Sexually assaulted | 2.4* | (1.6–3.5) | ||||

| Stalked | 2.0* | (1.1–3.7) | ||||

| Beaten by spouse/romantic partner | 1.9* | (1.3–2.9) | ||||

| Trauma to loved one | 1.7 | (0.9–3.1) | ||||

| Some other trauma | 1.6* | (1.1–2.4) | ||||

| Private traumae | 2.1* | (1.5–2.9) | ||||

| χ27c | 65.1* | |||||

| χ26d | 10.2 | |||||

| V Accidents/Injuries | ||||||

| Natural disaster | 0.1* | (0.0–0.1) | 0.1* | (0.0–0.2) | 0.1* | (0.0–0.2) |

| Toxic chemical exposure | 0.6 | (0.2–1.6) | 0.7 | (0.3–2.0) | ||

| Automobile accident | 0.6* | (0.4–0.9) | 0.7 | (0.5–1.1) | ||

| Life-threatening illness | 0.6* | (0.3–0.9) | 0.7 | (0.4–1.1) | ||

| Child with serious illness | 1.1 | (0.8–1.6) | 1.4 | (1.0–2.1) | ||

| Other life-threatening accident | 1.7 | (0.6–4.6) | 2.1 | (0.8–5.9) | ||

| χ26c | 62.2* | 54.2* | ||||

| χ25d | 46.9* | 49.1* | ||||

| VI Other | ||||||

| Mugged/threatened with a weapon | 0.6* | (0.4–0.9) | 0.7 | (0.5–1.2) | ||

| Human-made disaster | 0.6 | (0.2–1.8) | 0.8 | (0.3–2.2) | ||

| UD of a loved one | 1.2 | (0.8–1.6) | 1.4* | (1.0–2.0) | 1.5* | (1.0–2.0) |

| χ23c | 7.7* | 7.1 | ||||

| χ22d | 6.9* | 6.7* | ||||

| VII Prior Lifetime Exposure to the Same Trauma Type | ||||||

| Exposure to organized violencef | ||||||

| Participation in organized violence | 0.2* | (0.1–0.8) | 0.2* | (0.1–0.9) | 0.3* | (0.1–0.9) |

| Physical violence victimization | 3.2* | (1.3–7.9) | 2.5* | (1.0–6.4) | 3.2* | (1.3–7.9) |

| Sexual violence victimization | 0.8 | (0.5–1.5) | 0.9 | (0.5–1.5) | ||

| Accidents/injuries | 0.4 | (0.1–1.5) | 0.5 | (0.1–1.6) | ||

| Other | 0.7 | (0.4–1.5) | 0.8 | (0.4–1.5) | ||

| χ25c | 14.2* | 11.3* | χ22 = 10.8* | |||

| χ24d | 13.4* | 10.4* | χ21 = 10.1* | |||

| VIII Design-Adjusted AIC | 3,326.2 | 3,283.4 | 2,943.3 | |||

* Significant at the 0.05 level, two-sided test.

a Coefficients are based on multiple logistic regression equations with the 34,581 respondents who had a lifetime trauma (exclusive of the 95 whose randomly selected trauma was being a relief worker in a war zone) as the unit of analysis. All models control for respondent sex, age at interview, age at time of exposure to the trauma, and 21 dummy variables to distinguish among the 22 surveys.

b Given that all respondents experienced a trauma, a model containing a separate unrestricted OR for each of the 28 trauma types would be under-identified. The constraint we imposed to achieve identification was for the sum of the 28 logits to equal 0.0, which is equivalent to the product of the 28 ORs equaling 1.0. An OR significantly greater than 1.0 for a given trauma type in this model consequently can be interpreted as showing that the odds of PTSD associated with that trauma type are significantly greater than for the average trauma (noting that each trauma is given equal weight when defining the average).

c The joint significance of the set of ORs for traumas in the group.

d The significance of the differences among the ORs within the group.

e A private trauma is a trauma that some individuals reported in response to a question asked at the very end of the trauma section that asked if they ever had some other very upsetting experience they did not tell us about already (and this includes in response to a prior open-ended question about “any other” trauma) because they were too embarrassed or upset to talk about it. Respondents were told, before they answered, that if they reported such a trauma we would not ask them anything about what it was, only about their age when the trauma happened.

f There were no PTSD cases for those who had exposure to organized violence as their random event and experienced exposure to organized violence in the past.

Odds of PTSD differed significantly across trauma types in Model 1 (χ227 = 224.1, p < 0.001) due to a significant between-group difference in average odds (χ25 = 73.9, p < 0.001) and significant within-group differences in odds for traumas in each of the four groups: exposure to organized violence (χ23 = 34.4, p < 0.001); participation in organized violence (χ24 = 14.0, p = 0.007); accidents/injuries (χ25 = 46.9, p < 0.001); and the residual “other” trauma group (χ22 = 6.9, p = 0.032). In the two remaining groups, ORs were either not significant as a set (physical violence victimization; χ23 = 4.5, p = 0.22) or significant as a set, but not significantly different from each other (sexual violence victimization, with seven trauma types in the set; χ27 = 65.1, p < 0.001; χ26 = 10.2, p = 0.12).

Prior lifetime group-level same-type trauma exposure was a significant predictor of PTSD in Model 1 (χ25 = 14.2, p = 0.014) due to a significantly higher odds of PTSD after physical violence victimization in the presence vs. in the absence of a prior same-type trauma (OR = 3.2) and a significantly lower odds of PTSD after participation in organized violence in the presence vs. in the absence of a prior same-type trauma (OR = 0.2). The other three group-level ORs for prior same-type traumas were nonsignificant.

The predictors in Model 2 were based on Model 1 results to include each trauma type within the four groups having significant within-group OR differences in Model 1, a single measure for any sexual violence victimization, and measures of prior same-type participation in organized violence and physical violence victimization. Four random trauma types/groups had significantly elevated ORs and four others had significantly reduced ORs in Model 2. Three in each set of four were substantially elevated (OR = 2.7–4.7; kidnapped, witnessed atrocities, sexual violence) or reduced (OR = 0.1–0.3; civilian in a war zone or region of terror, natural disaster), while the other significant ORs were modest in magnitude, but associated with very common trauma types (unexpected death of loved one, 16.7% of all traumas; OR = 1.4; direct exposure to death/serious injury, 15.8% of all traumas; OR = 0.7). Based on these results, we estimated Model 3 with only the eight significant trauma measures in Model 2, plus dummy variables for prior same-type participation in organized violence and physical violence victimization. Model 3 (AIC = 2,943.3) was superior to Models 1 (AIC = 3,326.2) and 2 (AIC = 3,283.4). Results were similar to Model 2.

PTSD Risk Associated with Prior Lifetime Exposure to Other Traumas

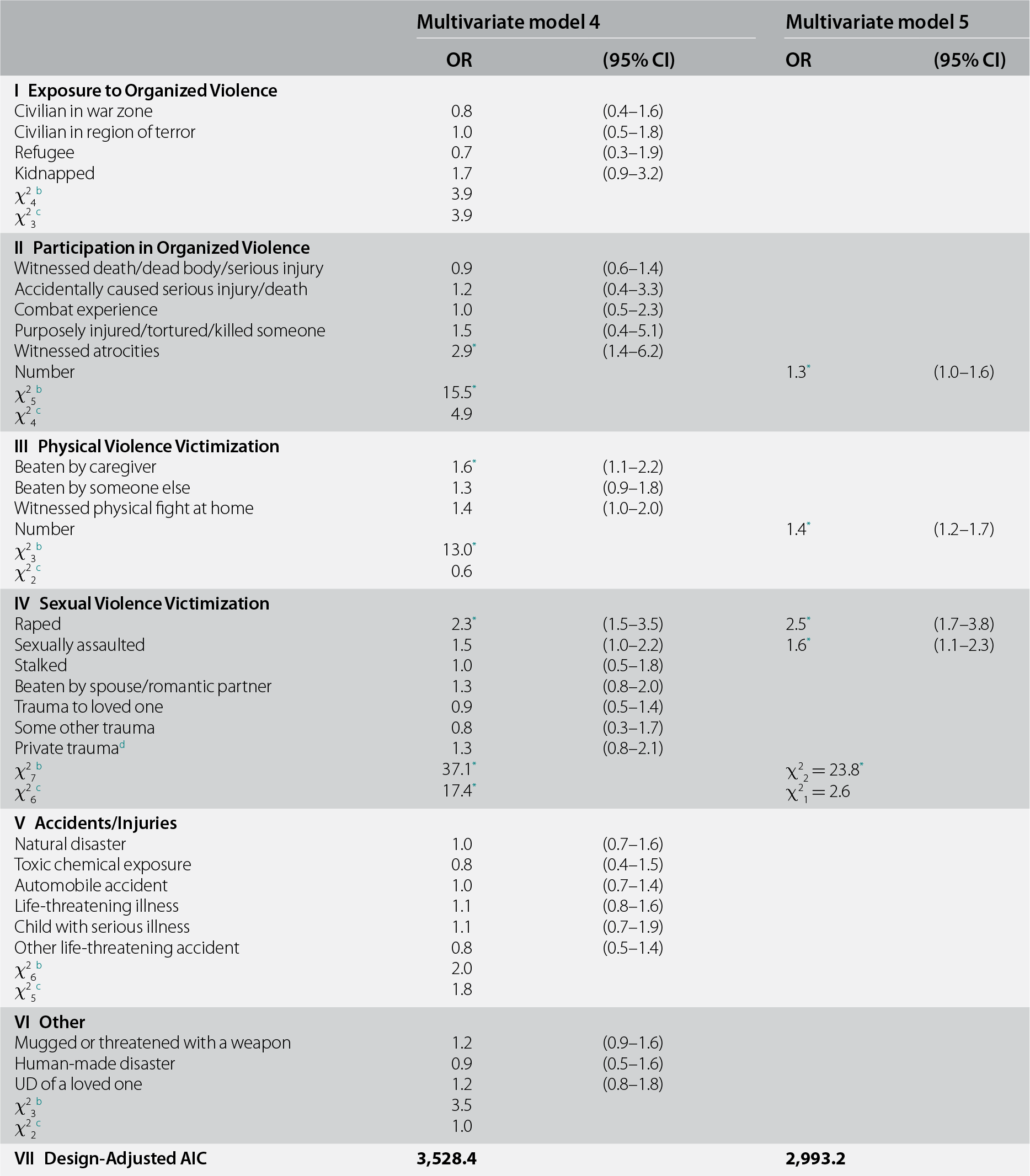

Significant Model 3 predictors were used as controls in Model 4 (see Table 9.3), which evaluated associations of prior lifetime traumas other than the random trauma with random-trauma PTSD. Prior traumas were significant overall (χ228 = 165.6, p < 0.001) and significantly different across types (χ227 = 56.7, p < 0.001). ORs in the prior sexual violence group were significant overall (χ27 = 37.1, p < 0.001) and significantly different within the group (χ26 = 17.4, p = 0.008). ORs for two other trauma groups were significant overall, but not significantly different within the group: participation in organized violence (χ25 = 15.5, p = 0.008; χ24 = 4.9, p = 0.30); and physical violence victimization (χ23 = 13.0, p = 0.005; χ22 = 0.6, p = 0.75). Based on these results, Model 5 included a count of prior lifetime trauma types experienced in each of the two groups where the Model 4 trauma-specific ORs were significant overall, but not significantly different within the group. The model also included separate dummy variables for the two significant lifetime sexual violence victimization traumas in Model 4 (rape and other sexual assault). The fit of Model 5 was superior to that of Model 4 (AIC = 2,933.2 vs. 3,528.4). All four ORs for prior trauma exposure in Model 5 were significantly elevated (OR = 1.3–1.4 for traumas involving participation in organized violence and physical violence victimization; OR = 2.5 for rape; OR = 1.6 for other sexual assault). We also evaluated the possibility that the four ORs associated with prior lifetime trauma exposure varied, depending on random trauma type, but that model (results not shown) performed less well than Model 5 (AIC = 3,076.9 vs. 2,933.2).

Table 9.3 Associations of DSM-IV/CIDI PTSD associated with randomly selected trauma types as a function of prior lifetime trauma exposure across all WMH surveys (n = 34,581)a

| Multivariate model 4 | Multivariate model 5 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |

| I Exposure to Organized Violence | ||||

| Civilian in war zone | 0.8 | (0.4–1.6) | ||

| Civilian in region of terror | 1.0 | (0.5–1.8) | ||

| Refugee | 0.7 | (0.3–1.9) | ||

| Kidnapped | 1.7 | (0.9–3.2) | ||

| χ24b | 3.9 | |||

| χ23c | 3.9 | |||

| II Participation in Organized Violence | ||||

| Witnessed death/dead body/serious injury | 0.9 | (0.6–1.4) | ||

| Accidentally caused serious injury/death | 1.2 | (0.4–3.3) | ||

| Combat experience | 1.0 | (0.5–2.3) | ||

| Purposely injured/tortured/killed someone | 1.5 | (0.4–5.1) | ||

| Witnessed atrocities | 2.9* | (1.4–6.2) | ||

| Number | 1.3* | (1.0–1.6) | ||

| χ25b | 15.5* | |||

| χ24c | 4.9 | |||

| III Physical Violence Victimization | ||||

| Beaten by caregiver | 1.6* | (1.1–2.2) | ||

| Beaten by someone else | 1.3 | (0.9–1.8) | ||

| Witnessed physical fight at home | 1.4 | (1.0–2.0) | ||

| Number | 1.4* | (1.2–1.7) | ||

| χ23b | 13.0* | |||

| χ22c | 0.6 | |||

| IV Sexual Violence Victimization | ||||

| Raped | 2.3* | (1.5–3.5) | 2.5* | (1.7–3.8) |

| Sexually assaulted | 1.5 | (1.0–2.2) | 1.6* | (1.1–2.3) |

| Stalked | 1.0 | (0.5–1.8) | ||

| Beaten by spouse/romantic partner | 1.3 | (0.8–2.0) | ||

| Trauma to loved one | 0.9 | (0.5–1.4) | ||

| Some other trauma | 0.8 | (0.3–1.7) | ||

| Private traumad | 1.3 | (0.8–2.1) | ||

| χ27b | 37.1* | χ22 = 23.8* | ||

| χ26c | 17.4* | χ21 = 2.6 | ||

| V Accidents/Injuries | ||||

| Natural disaster | 1.0 | (0.7–1.6) | ||

| Toxic chemical exposure | 0.8 | (0.4–1.5) | ||

| Automobile accident | 1.0 | (0.7–1.4) | ||

| Life-threatening illness | 1.1 | (0.8–1.6) | ||

| Child with serious illness | 1.1 | (0.7–1.9) | ||

| Other life-threatening accident | 0.8 | (0.5–1.4) | ||

| χ26b | 2.0 | |||

| χ25c | 1.8 | |||

| VI Other | ||||

| Mugged or threatened with a weapon | 1.2 | (0.9–1.6) | ||

| Human-made disaster | 0.9 | (0.5–1.6) | ||

| UD of a loved one | 1.2 | (0.8–1.8) | ||

| χ23b | 3.5 | |||

| χ22c | 1.0 | |||

| VII Design-Adjusted AIC | 3,528.4 | 2,993.2 | ||

* Significant at the 0.05 level, two-sided test.

a Coefficients are based on multiple logistic regression equations with the 34,581 respondents who had a lifetime trauma (exclusive of the 95 whose randomly selected trauma was being a relief worker in a war zone) as the unit of analysis. Both models control for respondent sex, age at interview, age at time of exposure to the trauma, 21 dummy variables to distinguish among the 22 surveys, and the predictors in Table 9.2, Multivariate model 3.

b The joint significance of the set of ORs for traumas in the group.

c The significance of differences among the ORs within the group.

d A private trauma is a trauma that some individuals reported in response to a question asked at the very end of the trauma section that asked if they ever had some other very upsetting experience they did not tell us about already (and this includes in response to a prior open-ended question about “any other” trauma) because they were too embarrassed or upset to talk about it. Respondents were told, before they answered, that if they reported such a trauma we would not ask them anything about what it was, only about their age when the trauma happened.

Sensitivity Analysis

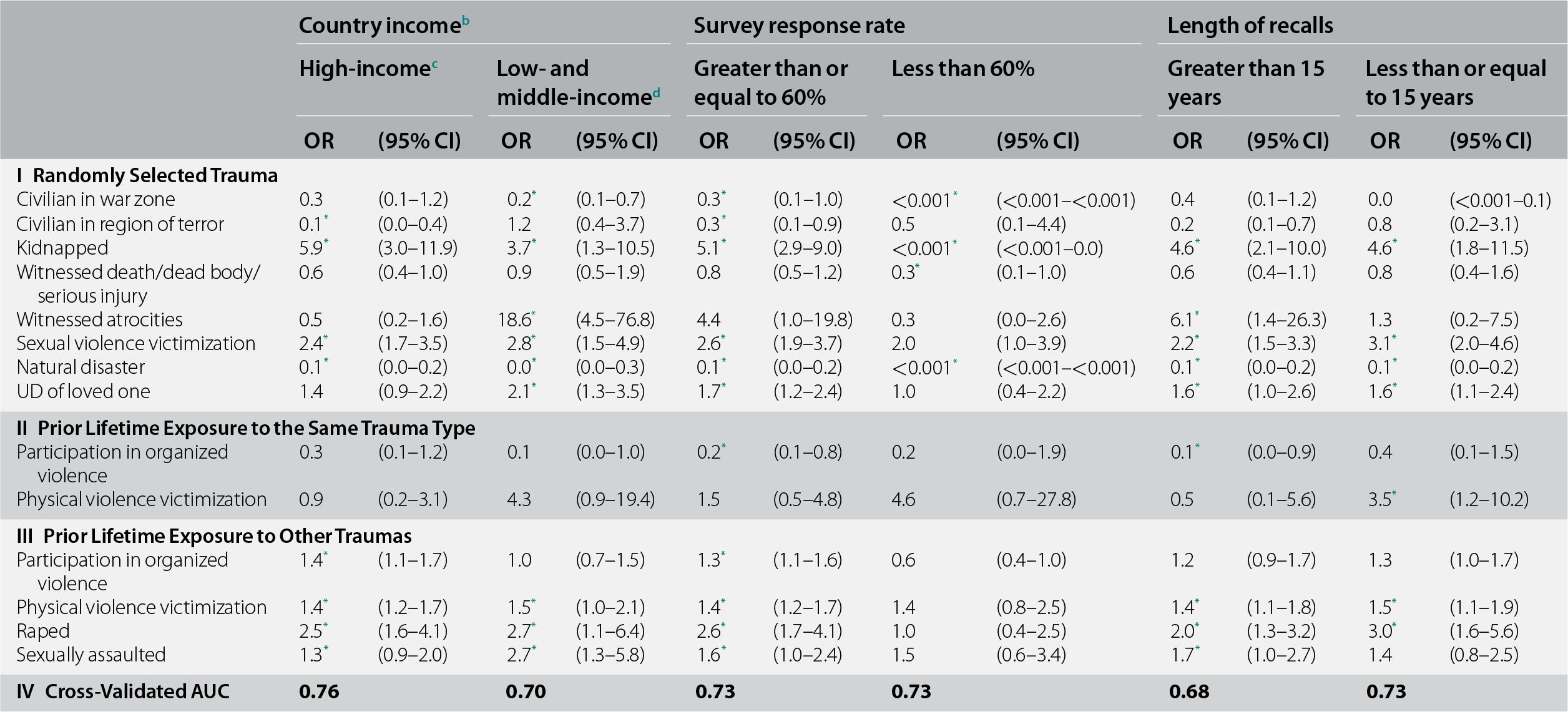

Model 5 was estimated separately in subsamples defined by country income (high- vs. low- and middle-income [LMIC]), survey response rate (lower than vs. higher than 60%), and median length of recall (0–15 vs. 16+ years between age of random trauma occurrence and age at interview) (see Table 9.4). Three of the 14 coefficients in the model (eight random trauma types, two same-type prior traumas, and four other prior traumas) differed meaningfully across subgroups in at least one comparison. The significantly reduced OR for being a civilian in a region of terror was confined to respondents who subsequently immigrated to a high-income country (OR = 0.1; 95% CI, 0.0–0.4 vs. OR = 1.2; 95% CI, 0.4–3.7 in LMICs; χ21 = 7.8, p = 0.005). The significantly elevated OR for witnessing atrocities was confined to respondents in LMICs (OR = 18.6; 95% CI, 4.5–76.8 vs. OR = 0.5; 95% CI, 0.2–1.6 in high-income countries; χ21 = 15.3, p < 0.001). And the significantly elevated OR associated with prior history of participation in organized violence was confined to surveys with response rates higher than 60% (OR = 1.3; 95% CI, 1.1–1.6 vs. OR = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.4–1.0 in surveys with low response rates; χ21 = 7.8, p = 0.005).

Table 9.4 Associations of DSM-IV/CIDI PTSD among people exposed to randomly selected trauma in cross-national sample by country income, survey response rate, and length of recalls (n = 34,581)a

| Country incomeb | Survey response rate | Length of recalls | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-incomec | Low- and middle-incomed | Greater than or equal to 60% | Less than 60% | Greater than 15 years | Less than or equal to 15 years | |||||||

| OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |

| I Randomly Selected Trauma | ||||||||||||

| Civilian in war zone | 0.3 | (0.1–1.2) | 0.2* | (0.1–0.7) | 0.3* | (0.1–1.0) | <0.001* | (<0.001–<0.001) | 0.4 | (0.1–1.2) | 0.0 | (<0.001–0.1) |

| Civilian in region of terror | 0.1* | (0.0–0.4) | 1.2 | (0.4–3.7) | 0.3* | (0.1–0.9) | 0.5 | (0.1–4.4) | 0.2 | (0.1–0.7) | 0.8 | (0.2–3.1) |

| Kidnapped | 5.9* | (3.0–11.9) | 3.7* | (1.3–10.5) | 5.1* | (2.9–9.0) | <0.001* | (<0.001–0.0) | 4.6* | (2.1–10.0) | 4.6* | (1.8–11.5) |

| Witnessed death/dead body/serious injury | 0.6 | (0.4–1.0) | 0.9 | (0.5–1.9) | 0.8 | (0.5–1.2) | 0.3* | (0.1–1.0) | 0.6 | (0.4–1.1) | 0.8 | (0.4–1.6) |

| Witnessed atrocities | 0.5 | (0.2–1.6) | 18.6* | (4.5–76.8) | 4.4 | (1.0–19.8) | 0.3 | (0.0–2.6) | 6.1* | (1.4–26.3) | 1.3 | (0.2–7.5) |

| Sexual violence victimization | 2.4* | (1.7–3.5) | 2.8* | (1.5–4.9) | 2.6* | (1.9–3.7) | 2.0 | (1.0–3.9) | 2.2* | (1.5–3.3) | 3.1* | (2.0–4.6) |

| Natural disaster | 0.1* | (0.0–0.2) | 0.0* | (0.0–0.3) | 0.1* | (0.0–0.2) | <0.001* | (<0.001–<0.001) | 0.1* | (0.0–0.2) | 0.1* | (0.0–0.2) |

| UD of loved one | 1.4 | (0.9–2.2) | 2.1* | (1.3–3.5) | 1.7* | (1.2–2.4) | 1.0 | (0.4–2.2) | 1.6* | (1.0–2.6) | 1.6* | (1.1–2.4) |

| II Prior Lifetime Exposure to the Same Trauma Type | ||||||||||||

| Participation in organized violence | 0.3 | (0.1–1.2) | 0.1 | (0.0–1.0) | 0.2* | (0.1–0.8) | 0.2 | (0.0–1.9) | 0.1* | (0.0–0.9) | 0.4 | (0.1–1.5) |

| Physical violence victimization | 0.9 | (0.2–3.1) | 4.3 | (0.9–19.4) | 1.5 | (0.5–4.8) | 4.6 | (0.7–27.8) | 0.5 | (0.1–5.6) | 3.5* | (1.2–10.2) |

| III Prior Lifetime Exposure to Other Traumas | ||||||||||||

| Participation in organized violence | 1.4* | (1.1–1.7) | 1.0 | (0.7–1.5) | 1.3* | (1.1–1.6) | 0.6 | (0.4–1.0) | 1.2 | (0.9–1.7) | 1.3 | (1.0–1.7) |

| Physical violence victimization | 1.4* | (1.2–1.7) | 1.5* | (1.0–2.1) | 1.4* | (1.2–1.7) | 1.4 | (0.8–2.5) | 1.4* | (1.1–1.8) | 1.5* | (1.1–1.9) |

| Raped | 2.5* | (1.6–4.1) | 2.7* | (1.1–6.4) | 2.6* | (1.7–4.1) | 1.0 | (0.4–2.5) | 2.0* | (1.3–3.2) | 3.0* | (1.6–5.6) |

| Sexually assaulted | 1.3* | (0.9–2.0) | 2.7* | (1.3–5.8) | 1.6* | (1.0–2.4) | 1.5 | (0.6–3.4) | 1.7* | (1.0–2.7) | 1.4 | (0.8–2.5) |

| IV Cross-Validated AUC | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.68 | 0.73 | ||||||

* Significant at the 0.05 level, two-sided test.

a Coefficients are based on multiple logistic regression equations with the 34,581 respondents who had a lifetime trauma (exclusive of the 95 whose randomly selected trauma was being a relief worker in a war zone) as the unit of analysis. All models controls for respondent sex, age at interview, age at time of exposure to the trauma, and 21 dummy variables to distinguish among the 22 surveys.

b The World Bank (2012) Data. Accessed May 12, 2012 at: http://data.worldbank.org/country. Some of the WMH countries have moved into new income categories since the surveys were conducted. The income groupings above reflect the status of each country at the time of data collection. The current income category of each country is available at the preceding URL.

c High-income countries: Belgium, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand, Northern Ireland, Spain, Spain–Murcia, United States.

d LMICs: Brazil–São Paulo, Bulgaria, Colombia, Colombia–Medellin, Mexico, Peru, Romania, South Africa, Ukraine.

Incremental Importance of Information about Prior Trauma Exposure

Incremental importance of information about prior trauma exposure in Model 5 was evaluated by estimating individual-level predicted probabilities of PTSD twice: once based on Model 5 and the second time on a model that excluded the Model 5 predictors for prior trauma exposure. An ROC curve for each set of predicted probabilities based on replicated tenfold cross-validation found AUC = 0.74 for Model 5 and AUC = 0.70 for the reduced model. Sensitivity among the 4% of respondents with highest predicted probabilities was 17.8% in Model 5 and 16.7% in the reduced model. (The 4% threshold was set because this is the prevalence of PTSD in the sample.)

Discussion

Our finding that PTSD was elevated after traumas involving extreme interpersonal violence is broadly consistent with previous research (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes and Nelson1995; Bromet et al., Reference Bromet, Sonnega and Kessler1998; Karam et al., Reference Karam, Friedman and Hill2014; Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Walsh, Uddin, Galea and Koenen2014; White et al., Reference White, Pearce and Morrison2015; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Summers, Dillon and Cougle2016). In contrast, our findings of lower-than-average ORs among civilians in a war zone/region of terror and victims of natural disaster are perplexing, given our finding regarding atrocities and numerous focused studies of high PTSD after disasters (Neria et al., Reference Neria, Nandi and Galea2008; North, Reference North2014). However, further investigation provides plausible explanations. Many WMH respondents who were civilians in war zones/regions of terror were elderly residents reporting childhood experiences during World War II. Direct exposure to recent war-related traumas was rare among these respondents, and this factor may account for their low risk of PTSD. In contrast, studies of refugees from recent conflicts show that PTSD is often (Shaar, Reference Shaar2013; Bogic et al., Reference Bogic, Njoku and Priebe2015) but not always (Karam et al., Reference Karam, Mneimneh and Dimassi2008; Alhasnawi et al., Reference Alhasnawi, Sadik and Rasheed2009) common in populations exposed to war-related traumas. Our finding of low PTSD risk among such civilians consequently has to be interpreted narrowly. Likewise, the WMH finding of low PTSD prevalence after natural disasters is likely to differ from the results of disaster-focused studies because the latter studies over-represent highly traumatized survivors (Norris et al., Reference Norris, Galea, Friedman and Watson2006; Goldmann & Galea, Reference Goldmann and Galea2014). Consistent with this possibility, rigorous studies of representative disaster survivor samples find PTSD prevalence comparable to the WMH estimate (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Galea, Jones and Parker2006; Bromet et al., Reference Bromet, Atwoli and Kawakami2017).

Our finding that prior participation in sectarian violence predicts low PTSD after random-trauma participation is indirectly consistent with research documenting low PTSD prevalence among policemen (Levy-Gigi et al., Reference Levy-Gigi, Richter-Levin, Okon-Singer, Keri and Bonanno2016) and other first responders (Levy-Gigi & Richter-Levin, Reference Levy-Gigi and Richter-Levin2014) and among Israeli settlers exposed to repeated bombings (Somer et al., Reference Somer, Zrihan-Weitzman and Fuse2009; Palgi et al., Reference Palgi, Gelkopf and Berger2015). These results could be due either to selection bias and/or to prior exposures promoting resilience (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Jones and Fear2009). Both experimental animal studies (Liu, Reference Liu2015) and observational human studies (Rutter, Reference Rutter2012) support the resilience possibility, although research showing that intervening psychopathology due to prior traumas mediates the association between trauma history and subsequent PTSD (Sayed et al., Reference Sayed, Iacoviello and Charney2015) confirms that prior traumas are more likely to create vulnerability than resilience. Research on the “healthy warrior effect” supports the selection bias possibility (Larson et al., Reference Larson, Highfill-McRoy and Booth-Kewley2008; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Jones and Fear2009). These considerations suggest that both processes might be at work, although we have no way to assess their relative importance.

Our finding that prior physical violence victimization predicts elevated PTSD risk after re-victimization helps make sense of the fact that our initial models did not replicate previous findings that PTSD rates are especially high after physical violence victimization (Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Walsh, Uddin, Galea and Koenen2014; White et al., Reference White, Pearce and Morrison2015; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Summers, Dillon and Cougle2016). This failure presumably arose because the pattern applied only to repeat victimizations, which were controlled in our models. For sexual violence, in comparison, we found that prior victimization was not relevant. This might seem to contradict the results of studies showing that sexual assault re-victimization is associated with poor mental health (Classen et al., Reference Classen, Palesh and Aggarwal2005; Miner et al., Reference Miner, Flitter and Robinson2006; Das & Otis, Reference Das and Otis2016), but those studies typically focused on victims of childhood sexual assault who were – vs. those who were not – re-victimized as adults, whereas the WMH finding compared adult sexual assault victims who were – vs. those who were not – previously victimized.

We also found that prior exposure to some other traumas was associated with generalized vulnerability to subsequent PTSD. Although ongoing research is investigating pathways leading to such generalized vulnerability (Rutter, Reference Rutter2012; Daskalakis et al., Reference Daskalakis, Bagot, Parker, Vinkers and de Kloet2013; Levy-Gigi et al., Reference Levy-Gigi, Richter-Levin, Okon-Singer, Keri and Bonanno2016), we know of no work on the differential effects of trauma types in leading to generalized vulnerability. However, suggestive related evidence exists on differences in associations of childhood adversities with adult mental disorders across different childhood adversity types (Pirkola et al., Reference Pirkola, Isometsa and Aro2005; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, McLaughlin and Green2010) and profiles (Putnam et al., Reference Putnam, Harris and Putnam2013; McLafferty et al., Reference McLafferty, Armour and McKenna2015).

Our results are limited in several ways. First, the cross-sectional WMH design introduced the possibility of recall inaccuracy that could have biased estimates, as extensive research shows that individuals with PTSD differ significantly from others in their trauma memories (Moore & Zoellner, Reference Moore and Zoellner2007; Brewin, Reference Brewin2014; Crespo & Fernández-Lansac, Reference Crespo and Fernández-Lansac2016). Second, PTSD was assessed with a fully structured diagnostic interview that had imperfect concordance with clinical diagnoses. Third, no attempt was made to assess individual differences in vulnerabilities that could have influenced trauma exposure or PTSD, possibly introducing bias into estimates of the relative importance of trauma types. Intervening mental disorders associated with prior traumas, which we will consider in Chapter 11, are special cases (Breslau et al., Reference Breslau, Peterson and Schultz2008; Cougle et al., Reference Cougle, Resnick and Kilpatrick2009; Breslau & Peterson, Reference Breslau and Peterson2010).

Within the context of these limitations, the analyses refined previous evidence that PTSD is especially common after traumas involving either experiencing or witnessing interpersonal violence, but that this is limited to repeat exposures. We also confirmed that prior exposure to some traumas is associated more with resilience than with vulnerability. Finally, we confirmed the finding of previous studies that a broad trauma history is associated with generalized vulnerability to PTSD, but that this is limited to prior traumas involving interpersonal violence. Although our results leave unanswered questions about causal pathways and mechanisms, they both document the complex ways specific trauma types and histories are associated with PTSD and provide an empirical foundation for more focused investigations of these associations in the future.