Management Implications

Since their introduction in the early 1900s, invasive submersed plants have adversely affected lakes and waterways on both islands of New Zealand. Some of the worst plant invaders in the country are from the “oxygen weed” (Hydrocharitaceae) family and yield high biomass plant canopies that displace native flora and fauna and obstruct the recreational use and economic activities in affected lakes. Water resource managers regularly utilize herbicides to control aquatic weeds to restore invaded lakes and waterways. However, there are only two aquatic herbicides currently registered in New Zealand for submersed weed control, which limits the scope of management opportunity. Registration of the synthetic auxin herbicide, florpyrauxifen-benzyl, in the United States has provided another chemical option for aquatic weed control. However, limited data are available for florpyrauxifen-benzyl concentrations required to effectively control frequently managed Hydrocharitaceae in New Zealand. A dose–response study was conducted to examine the sensitivity of three New Zealand invasive species [oxygen-weed, Lagarosiphon major (Ridley) Moss; Brazilian waterweed, Egeria densa Planch.; and Canadian waterweed, Elodea canadensis Michx.] and one native submersed plant (watermilfoil, Myriophyllum triphyllum Orchard) to the herbicide. Among early invasion scenarios, native plants are frequently found cohabitating with invasive weed species. Therefore, herbicides that provide selective control with minimal impact to native plant species are desired. Following the 21-d growth chamber evaluations, we found the native plant M. triphyllum to be the species most sensitive to herbicide. The invasive plant L. major was also sensitive to florpyrauxifen-benzyl. The invasive plants E. canadensis and E. densa displayed a sublethal response from herbicide, and control was not achieved at any florpyrauxifen-benzyl concentration labeled for submersed plant applications (48 µg ai L−1). Therefore, targeted concentrations deployed for invasive plant control within mixed communities would likely injure the native Myriophyllum spp. However, native species do recover from seedbanks following invasive plant removal. Future research should evaluate additional native and introduced invasive species for best management guidance in New Zealand and investigate approaches, including concentration and exposure time relationships, to provide effective control of submersed aquatic weeds.

Introduction

Preservation of native submersed aquatic plants is vital for conserving biodiversity within waterways (Hofstra et al. Reference Hofstra, Clements, Rendle and Champion2021; Kovalenko et al. Reference Kovalenko, Dibble and Slade2010), as macrophytes are essential for numerous ecosystem services (Carpenter and Lodge Reference Carpenter and Lodge1986; Cyr and Downing Reference Cyr and Downing1988; Madsen et al. Reference Madsen, Chambers, James, Koch and Westlake2001; Petr Reference Petr2000; Valley et al. Reference Valley, Cross and Radomski2004). Conversely, the intrusion of invasive submersed plants into aquatic biomes can displace endemic flora and fauna through structural and resource competition resulting from the formation of aggressive monotypic stands that limit light, carbon, and nutrient availability (Hofstra et al. Reference Hofstra, Clayton, Champion, de Winton, Hamilton, Collier, Quinn and Howard-Williams2018; True-Meadows et al. Reference True-Meadows, Haug and Richardson2016; Wells et al. Reference Wells, de Winton and Clayton1997). Similarly, invasive submersed macrophytes that produce high biomass yielding canopies (e.g., Hydrocharitaceae) commonly obstruct navigation, clog water intakes for irrigation and hydroelectric generation, and impede recreation and economic opportunities (Carpenter and Lodge Reference Carpenter and Lodge1986; Clayton and Champion Reference Clayton and Champion2006; Langeland Reference Langeland1996). In New Zealand, some of the most problematic invasive submersed plants are known as the “oxygen weeds” (Clayton Reference Clayton1996), which includes the species oxygen-weed [Lagarosiphon major (Ridley) Moss], Canadian waterweed (Elodea canadensis Michx.), and Brazilian waterweed (Egeria densa Planch.). Water resource managers regularly seek effective control methods to eradicate or manage invasive aquatic plants to enable the recovery of desirable native habitats.

While biological, physical, and mechanical control options do exist, herbicides are largely the most economic, effective, and selective management tool utilized to control invasive aquatic weeds (Hussner et al. Reference Hussner, Stiers, Verhofstad, Bakker, Grutters, Haury, van Valkenburg, Brundu, Newman, Clayton, Anderson and Hofstra2017; Muller et al. Reference Muller, Hofstra and Champion2021). It is important to recognize that applying herbicides for aquatic weed management requires several factors to be considered, some of which include regulatory and economic constraints, herbicide efficacy and selectivity, and public support for the treatment (Champion et al. Reference Champion, Clayton and Rowe2002; Clayton Reference Clayton1996; Madsen Reference Madsen2000; Stallings et al. Reference Stallings, Seth-Carley and Richardson2015). Combinations of these factors influence initiatives used to broaden application strategies for restoring native plant populations within invaded waterways (Getsinger et al. Reference Getsinger, Netherland, Grue and Koschnick2008; Weber et al. Reference Weber, Wainger, Harms and Nesslage2020). When considering herbicide-based management strategies, it is critical to understand target and non-target plant responses. Further, these data will help to provide appropriate recommendations for management action in mixed assemblages of native and invasive species, especially because most available herbicides do not provide uniform control of aquatic weeds.

Currently, only two herbicides are labeled for submersed aquatic plant control in New Zealand, diquat-dibromide (WSSA Group 22; photosystem I inhibitor) and endothall dipotassium salt (WSSA Group 31; protein phosphatase inhibitor). For perspective, 16 herbicides are presently labeled for aquatic weed management in the United States (Gettys et al. Reference Glomski and Netherland2020). A limited herbicide portfolio restricts management options and prompts selection pressures, which can select for herbicide-resistant plant populations that further complicate future invasive plant control (Richardson Reference Richardson2008). While endothall dipotassium salt and diquat-dibromide effectively control L. major (Wells and Champion Reference Wells and Champion2010; Wells et al. Reference Wells, Champion and Clayton2014), only diquat-dibromide is efficacious on E. canadensis and E. densa (Glomski et al. Reference Glomski, Skogerboe and Getsinger2005; Hofstra and Clayton Reference Hofstra and Clayton2001; Sesin et al. Reference Sesin, Dalton, Boutin, Robinson, Bartlett and Pick2018; Skogerboe et al. Reference Skogerboe, Getsinger and Glomski2006). Previous studies have examined additional herbicide sites of action (SOAs) including triclopyr (WSSA group 4; synthetic auxin), dichlobenil (WSSA Group 29; cellulose synthase inhibitor), and fluridone (WSSA Group 12; phytoene desaturase inhibitor) to control invasive submersed plants; however, these herbicides are not efficacious on L. major, E. canadensis, and E. densa in mesocosm or field studies (Hofstra and Clayton Reference Hofstra and Clayton2001; Wells et al. Reference Wells, Coffey and Lauren1986), nor are these herbicides registered for aquatic weed control applications in New Zealand (Champion et al. Reference Champion, Hofstra and de Winton2019). While endothall dipotassium salt has shown some selectively on desirable native plants in the United States and New Zealand (Hofstra and Clayton Reference Hofstra and Clayton2001; Skogerboe and Getsinger Reference Skogerboe and Getsinger2002), diquat-dibromide is a nonselective contact herbicide, and applications are prone to off-target injury to native plants. Wells and Champion (Reference Wells and Champion2010) have suggested diquat had transient injury on native charophytes in New Zealand following invasive plant eradication efforts, though recovery was not immediate. Nevertheless, there remains a need to evaluate new herbicides as they become available to enhance current invasive aquatic plant management programs, while protecting native plant species like watermilfoil (Myriophyllum triphyllum Orchard), which may be frequently intermixed or adjacent to invasives (Rattray et al. Reference Rattray, Howard-Williams and Brown1994).

Florpyrauxifen-benzyl (WSSA Group 4; synthetic auxin) is a relatively new herbicide initially introduced for rice (Oryza sativa L.) production (Epp et al. Reference Epp, Alexander, Balko, Buysse, Brewster, Bryan, Daeuble, Fields, Gast, Green, Irvine, Lo, Lowe, Renga and Richburg2016) and registered for aquatic use in the United States in 2018. Synthetic auxins have been utilized for crop and non-crop weed management since development in the 1940s (Peterson et al. Reference Peterson, McMaster, Riechers, Skelton and Stahlman2016). This class of herbicides is frequently cited for their favorable management characteristics compared with other herbicide SOAs (Glomski and Netherland Reference Glomski and Netherland2010; Grossmann Reference Grossmann2010; Heap Reference Heap2022; Sprecher et al. Reference Sprecher, Getsinger and Stewart1998). Synthetic auxin herbicides like florpyrauxifen-benzyl are unique in both selectiveness and phloem mobility within susceptible plants, as they mimic the natural plant growth hormone indole-3-acetic acid (Epp et al. Reference Epp, Alexander, Balko, Buysse, Brewster, Bryan, Daeuble, Fields, Gast, Green, Irvine, Lo, Lowe, Renga and Richburg2016). Endogenous auxin compounds are essential for plant cell elongation and division, phototropism, apical dominance, and additional developmental processes (Gaines Reference Gaines2020; Grossmann Reference Grossmann2010). Susceptible plants treated with synthetic auxins undergo rapid growth complexes when transcription factor proteins responsible for plant regulation become overwhelmed, triggering uncontrolled gene expression (Grossmann Reference Grossmann2010; McCauley et al. Reference McCauley, McAdam, Bhide, Thimmapuram, Banks and Young2020; Parry et al. Reference Parry, Calderon-Villalobos, Prigge, Peret, Dharmasiri, Itoh, Lechner, Gray, Bennett and Estelle2009). Eventually, the process of uncontrolled gene expression initiates abscisic acid, hydrogen peroxide, and ethylene accumulation, leading to leaf senescence, cell death, and loss of turgor through multifaceted processes that are still undergoing investigation (Grossmann Reference Grossmann2010; McCauley et al. Reference McCauley, McAdam, Bhide, Thimmapuram, Banks and Young2020). Synthetic auxin overload in susceptible plants characteristically results in apical epinasty, twisting, and curling of leaf tissues. In the United States, florpyrauxifen-benzyl has provided an additional herbicide for selective invasive aquatic plant management among several common invasive weeds including hydrilla [Hydrilla verticillata (L.f.) Royle], watermilfoils (Myriophyllum spp.), and crested floatingheart [Nymphoides cristata (Roxb.) Kuntze.] while having limited activity on native Potamogeton spp. (Beets and Netherland Reference Beets and Netherland2018; Mudge et al. Reference Mudge, Sartain, Sperry and Getsinger2021; Netherland and Richardson Reference Netherland and Richardson2016; Richardson et al. Reference Richardson, Haug and Netherland2016; Sperry et al. Reference Sperry, Leary, Jones and Ferrell2021). Additionally, florpyrauxifen-benzyl was classified by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency as a reduced-risk herbicide (USEPA 2017) with favorable toxicological profiles (Buczek et al. Reference Buczek, Archambault, Cope and Heilman2020).

Given the limited number of registered herbicides in New Zealand, there remains a need to evaluate additional selective herbicides that provide different SOAs than those currently registered. Registration of such a herbicide would promote herbicide stewardship and increase treatment options for controlling invasive submersed plants. The objective of this study was to implement a small-scale screening method for evaluating relative sensitives to florpyrauxifen-benzyl of native and invasive plant species found in New Zealand using dose–response protocols. Based on previous screening studies (e.g., Beets et al. Reference Beets, Heilman and Netherland2019; Howell et al. Reference Howell, Hofstra, Heilman and Richardson2021; Netherland and Richardson Reference Netherland and Richardson2016; Richardson et al. Reference Richardson, Haug and Netherland2016), we hypothesize the native species, M. triphyllum, will be the most sensitive to the herbicide; however, we anticipate the invasive species tested to display comparable sensitivity to florpyrauxifen-benzyl.

Materials and Methods

A growth chamber experiment was conducted at the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) Ruakura Campus, Hamilton, New Zealand in fall (April to May) 2018. The experimental design closely followed a modified version of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) protocol described by Netherland and Richardson (Reference Netherland and Richardson2016) to evaluate the sensitivity of M. triphyllum, L. major, E. canadensis, and E. densa to florpyrauxifen-benzyl. Tested species were collected from on-site stock tanks or field harvested locally within the Waikato basin in March and April 2018. Plant species were then propagated in aerated outdoor tanks under ambient environmental conditions (µ = 18.5 to 20.0 C) with 50% shade fabric and monitored twice weekly to ensure adequate population vigor before testing.

At experiment initiation, apical shoot tips (6 cm) of each species were removed from the outdoor tanks. The basal portions of the apical shoots were secured with lead weights to ensure submersion during propagation. Weighted plant shoots were then placed in aerated 6-L bins containing dechlorinated tap water. Bins were subsequently placed in the growth chamber and monitored for 7 to 10 d for confirmation of plant root generation and shoot elongation. Growth chamber conditions were set to a constant 16-h light:8-h dark photoperiod, 21.5 C temperature, and light intensity of 130 to 160 µE m−2 s−1 at bench level. Following rooting confirmation, one shoot of each species was planted in a 20-ml vial filled with 16 cm of washed sand (i.e., a single shoot per vial). At minimum, 3 cm of the shoot was buried in the sand. Seven days before treatment, 1-L jars were filled with 750 ml of Smart and Barko solution, and each jar was provided with supplemental aeration (Smart and Barko Reference Smart and Barko1985). Vials containing plants were then placed in the respective treatment jars. Prior studies noted Myriophyllum spp. to be highly sensitive to florpyrauxifen-benzyl (Netherland and Richardson Reference Netherland and Richardson2016; Richardson et al. Reference Richardson, Haug and Netherland2016). As such, M. triphyllum plants and the Hydrocharitaceae evaluated in this study were isolated in separate treatment jars to evaluate herbicide concentration response endpoints based on the recognized sensitivity. Stock solutions of florpyrauxifen-benzyl suspension concentrate (ProcellaCOR SC, SePRO, Carmel, IN, USA) were produced for treatment and injected into the water column to achieve desired serial dose–response concentrations. Treatments consisted of static exposure to a geometric series of rates ranging from 0 to 107.86 µg ai L−1 (Table 1). Pretreatment water pH was 8.2 (SD ± 0.2) and temperature was 22.2 C (SD ± 1.4). All treatments were replicated five times (one jar was considered as one replication) following a randomized complete block design, and experiments were repeated in time (two consecutive runs). At treatment, five nontreated jars were removed to determine pretreatment weight and shoot length of each species. Trials lasted 21 d, and dechlorinated water was added to the jars as water loss occurred. Visual observations of auxin herbicide symptoms (e.g., chlorosis, epinasty, leaf-shattering) were documented throughout experimentation. At 21 d after treatment (DAT), above-sediment green plant tissue was harvested and blotted dry with paper towels, and then fresh weight (g) and shoot length (cm) were immediately recorded. Plants were then oven-dried at 60 C for 72 h to obtain a constant dry weight. Plant dry weights were measured using an analytical-grade balance with 0.001 g accuracy.

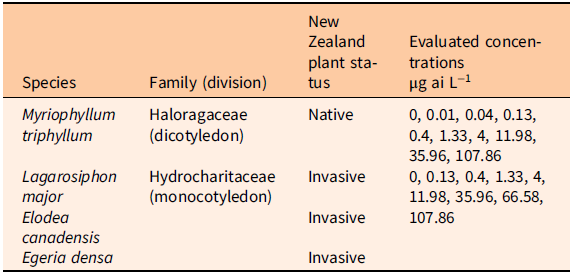

Table 1. Herbicide concentrations used to evaluate species sensitivity to florpyrauxifen-benzyl in the growth chamber study.

Data Analysis

There was no significant run effect according to ANOVA (P > 0.05), so treatment data were pooled over experiments to account for inherent response variability in the growth chamber studies. Plant shoot length, fresh biomass, and dry biomass metrics were transformed to percent inhibition (%In) of the nontreated control to standardize plant response to tested florpyrauxifen-benzyl concentrations tested using Equation 1:

Where (µc) is the mean of the nontreated group and (µt) is the mean value of the treatment group. Percent inhibition (%In) was limited to the logical extremes (0% to 100%) to achieve appropriate parameters for modeling plant response to herbicide concentrations tested, as plant inhibition cannot physically exceed a 100% threshold. Following similar statistical procedures as Netherland and Richardson (Reference Netherland and Richardson2016), nonlinear regression analyses were performed in SigmaPlot v. 14.0 (SigmaPlot v. 14.0.3.192, Systat Software, Point Richmond, CA, USA) to estimate 50% effective dose concentrations (EC50). Equation 2 is the four-parameter log-logistic regression curve used to estimate EC50 shoot length and dry weight inhibition metrics at tested florpyrauxifen-benzyl concentrations as described in detail by Ritz et al. (Reference Ritz, Kniss and Streibig2015) and Seefeldt et al. (Reference Seefeldt, Jensen and Fuerst1995).

For Equation 2, the parameters y o and a represent the limit extreme and difference values, b is the slope of the inflection point, x is the herbicide concentration, and x EC50 is the herbicide concentration providing 50% inhibition of the maximum (i.e., 100% In). Equation 3 is the Weibull four-parameter model used to estimate EC50 fresh weight inhibition metrics at tested florpyrauxifen-benzyl concentrations as described in detail by Price et al. (Reference Price, Shafii and Seefeldt2012) and Brown and Mayer (Reference Brown and Mayer1988).

For Equation 3, the parameter a is the upper asymptote, b is the slope of the inflection point, c is the shape of the curve, x is the herbicide concentration, and x EC50 is the herbicide concentration providing 50% inhibition of the maximum (i.e., 100% In). The Weibull model is suitable when asymmetric data, like plant fresh weight, define a response variable at a different rate than could be described using a log-logistic curve (Price et al. Reference Price, Shafii and Seefeldt2012). Selected models were chosen when they converged across the applicable dataset(s) and when the Shapiro-Wilks normality assumptions were met (α = 0.05). For each species by metric modeled, lack-of-fit tests were performed to ensure the selected model was appropriate. Graphical outputs from the models used log-transformed values of tested florpyrauxifen-benzyl concentrations for each species response.

A Dunnett’s test (P < 0.05) was performed in RStudio (R v. 4.0.3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) to establish the lowest observed effect concentration (LOEC) between the nontreated and treated plant dry biomass at the select florpyrauxifen-benzyl concentrations using the base and multcomp packages (Horthorn et al. Reference Horthorn, Bretz and Westfall2008; R Core Team 2022). An index comparing the estimated herbicide tolerance of invasive plants to the estimated herbicide susceptibility of the native plant (I/N ratio) was also calculated. The I/N ratio was defined as the estimated dry weight EC50 value of invasive plant species (Hydrocharitaceae; I) divided by the corresponding native species (M. triphyllum; N) dry weight EC50 value (EC50 invasive species/EC50 native species).

Results and Discussion

Nontreated reference plants exhibited shoot elongation and axillary branching during the 21-d static exposure. Nontreated plant biomass increased by 2.5 to 9.5 times that of the pretreatment biomass, which conforms to experiment validation standards of the OECD protocol (OECD 2014). The tested florpyrauxifen-benzyl concentrations evaluated in this study ranged 0.02% to 225% of the commonly recommended formulated product maximum use rate (48 µg L−1) for submersed plant applications; therefore, plant control was compared directly using predicted EC50 values of shoot length, fresh weight, and dry weight metrics.

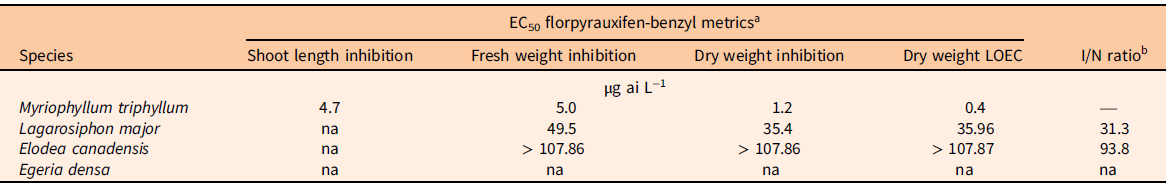

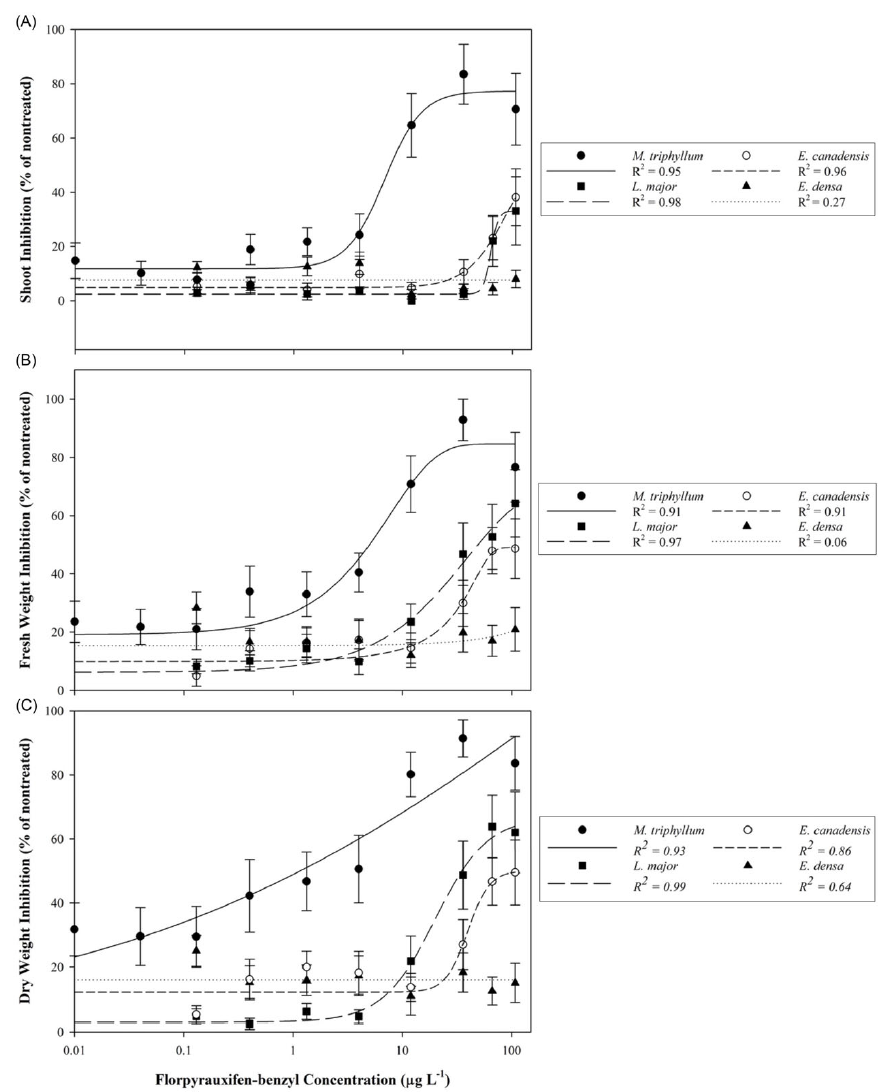

The native species, M. triphyllum, was the most sensitive plant evaluated in this study, with a dry weight EC50 value of 1.2 µg L−1 and LOEC of 0.4 µg L−1 (Table 2; Figure 1). Within 1 to 2 DAT, M. triphyllum exhibited auxin herbicide exposure symptoms, with epinasty appearing as the first sign of plant injury (data not shown). At the 2 wk after treatment (WAT) evaluation, plant symptoms had progressed to necrotic shoots with black nodes at concentrations >1.33 µg L−1. Following plant harvest, M. triphyllum treated with >11.98 µg L−1 had <20% biomass remaining, and shoot lengths were reduced by 65% relative to the nontreated plants (Figure 1). These results confirm our hypothesis that M. triphyllum is highly sensitive to florpyrauxifen-benzyl, as the EC50 values in this study align well with previous small-scale herbicide-screening observations among other Myriophyllum spp. (Netherland and Richardson Reference Netherland and Richardson2016; Richardson et al. Reference Richardson, Haug and Netherland2016).

Table 2. Metrics of 50% effective concentrations (EC50) derived from log-logistic four-parameter or Weibull four-parameter dose–response models following plant exposure to florpyrauxifen-benzyl at 0 to 107.86 µg ai L−1, the lowest observed effect concentration (LOEC) calculated from Dunnett’s test at the 0.05 significance level, and invasive-to-native plant tolerance index.

a EC50 values were not achieved (na) if species exhibited low inhibition (µ < 50%) for the metric tested.

b Estimated invasive species (Hydrocharitaceae; I) dry weight EC50 value divided by the native species (M. triphyllum; N) dry weight EC50 value.

Figure 1. Native (Myriophyllum triphyllum) and invasive (Lagarosiphon major, Elodea canadensis, and Egeria densa) plant responses following 21-d static exposure to tested florpyrauxifen-benzyl serial concentrations expressed as percent inhibition of the nontreated control: (A) shoot inhibition, (B) fresh weight inhibition, and (C) dry weight inhibition. Data points with standard error bars represent mean response of the metric evaluated. Herbicide concentration is provided on a log10 scale. Regression analyses implemented for plant shoot and dry weight inhibition correspond to the log-logistic four-parameter model equation: Y = y o + {a/[1 + (x/x EC50) b ]}, while fresh weight inhibition was modeled using the Weibull four-parameter equation: Y = a × {1 − exp[−(x − x EC50 + b + ln(2)1/c ))/b) c ]}.

The most sensitive invasive species tested was L. major, which had an estimated dry weight EC50 value of 35.4 µg L−1 and LOEC of 35.96 µg L−1 (Table 2; Figure 1). Nevertheless, an EC50 for shoot length was not achieved (shoot inhibition µ < 50%). Lagarosiphon major injury from florpyrauxifen-benzyl was also rapid, with proximal bending and minor chlorosis observed within 1 to 3 DAT (data not shown). Leaf abscission from the apical shoots ensued ca. 7 DAT, when plants were gently agitated using forceps, with apical shoots fragmenting at concentrations >11.98 µg L−1 2 WAT. Howell et al. (Reference Howell, Hofstra, Heilman and Richardson2021) noted a similar response to herbicide in an outdoor mesocosm study in which L. major exposed to florpyrauxifen-benzyl at 30 and 50 µg ai L−1 displayed proximal leaf abscission and stem fragmentation at 5 to 7 DAT. At harvest, biomass of L. major shoots treated with concentrations >66.58 µg L−1 was reduced more than 62% compared with the nontreated plants. Though sensitive, the calculated I/N ratio suggests L. major would require 31.3 times more herbicide to produce EC50 values similar to that of the native species, M. triphyllum (Table 2).

Elodea canadensis was not as sensitive to florpyrauxifen-benzyl as L. major, with fresh and dry weight EC50 value estimates greater than the highest concentration tested of 107.86 µg L−1. Consequently, the LOEC for E. canadensis was also >107.86 µg L−1. Shoot length inhibition did not meet the criteria for estimating an EC50 at any tested concentration (shoot inhibition µ < 50%) (Table 2; Figure 1). While response metrics suggest low sensitivity in this study, plant injury and growth abnormalities were present. Shoots became brittle, with necrotic tissue forming at the nodes with exposures to concentrations >11.98 µg L−1 at 2 to 3 WAT (data not shown). Conversely, a slight increase in axillary branching was noted at harvest among several plants treated at ≤11.98 µg L−1. Based on the I/N ratio, E. canadensis would require >90 times more herbicide to produce an EC50 value comparable to that of M. triphyllum (Table 2). Similarly, Beets et al. (Reference Beets, Heilman and Netherland2019) noticed E. canadensis biomass was not affected when testing florpyrauxifen-benzyl at 3 to 27 µg ai L−1 in a 60-d concentration and exposure (CET) study.

Of the Hydrocharitaceae species evaluated, E. densa was the least sensitive, with EC50 and LOEC values not achieved with any test concentrations (Table 2). The trend in the data appeared linear with a shallow slope, indicating limited plant response to increased florpyrauxifen-benzyl concentrations during the 21-d exposure (Figure 1). Much like E. canadensis, apical portions of treated plants displayed auxin herbicide exposure characteristics, with slight epinasty, shoot twisting, and internode lengthening observed at 2 WAT at concentrations ≥35.96 µg L−1 (data not shown). However, these abnormal growth patterns did not appreciably reduce biomass or shoot lengths collected at harvest (Table 2). Howell et al. (Reference Howell, Hofstra, Heilman and Richardson2021) noted 80% E. densa visual control was not achieved until 7 WAT with florpyrauxifen-benzyl at 30 µg L−1 in outdoor mesocosm studies. Likewise, Haug et al. (Reference Haug, Ahmed, Gannon and Richardson2021) indicated E. densa had less shoot absorption and translocation than the Hydrocharitaceae species H. verticillata in a 14C experiment applying 10 µg ai L−1 florpyrauxifen-benzyl during a 192-h exposure period. These previous studies suggest longer static exposure periods (e.g., >4 wk) may improve control of E. densa, as indicated by the low sensitivity shown in the present study, especially at lower concentrations (e.g., <36.96 µg L−1). Consistent with this hypothesis, Madsen et al. (Reference Madsen, Morgan, Miskella, Kyser, Gilbert, O’Brien and Getsinger2021) showed E. densa dry biomass was reduced by approximately 50% compared with the nontreated plants following a 10-wk static exposure to 50 µg ai L−1 florpyrauxifen-benzyl.

Elodea canadensis and E. densa proliferation in axillary branching and shoot development at the lower treatment concentrations (≤11.98 µg L−1) further conveys the typical synthetic auxin properties of florpyrauxifen-benzyl, despite limited overall efficacy (personal observation). Hormesis, or augmented growth following sublethal herbicide concentrations, is characteristic of low-dose auxin injury (Belz and Duke Reference Belz and Duke2014; Cedergreen et al. Reference Cedergreen, Streibig, Kudsk, Mathiassen and Duke2007; Jalal et al. Reference Jalal, de Oliveira, Ribeiro, Fernandes, Mariano and Trindade2021). Hormesis was noted in a previous study that documented a stimulated increase in yield for E. densa treated with the auxin herbicide, 2,4-D, applied at 1 to 11 mg ai L−1 (Peres et al. Reference Peres and Della Vechia2017). Similarly, Mudge et al. (Reference Mudge, Sartain, Sperry and Getsinger2021) suggested potential hormesis occurred for E. canadensis in a 6-wk CET study when exposed to florpyrauxifen-benzyl at 3, 6, and 9 μg ai L−1. While macrophyte hormesis literature is limited for florpyrauxifen-benzyl, findings from these previous auxin herbicide screenings closely align with the observations of E. canadensis and E. densa response to treatment in the present study. Further, these data denote the perceptive effective dose thresholding, which can occur among auxin herbicides, and the varying sensitivity found even within the same plant family (e.g., L. major dry weight EC50 was ∼3-fold less than E. canadensis in the present study). Further research is required to specifically evaluate the lower florpyrauxifen-benzyl threshold concentrations and exposures that deter possible hormesis in common field application scenarios; notably in high water-exchange situations (e.g., flowing systems).

Though complexities of induced hormesis do exist with auxin herbicides (Belgers et al. Reference Belgers, Van Lieverloo, Van der Pas and Van de Brink2007; Peres et al. Reference Peres and Della Vechia2017), submersed plant tolerance and sensitivity to synthetic auxins is well documented (Getsinger et al. Reference Getsinger, Sprecher and Smagula2003; Haug and Bellaud Reference Haug and Bellaud2013; Hofstra and Clayton Reference Hofstra and Clayton2001; Parsons et al. Reference Parsons, Hamel, Madsen and Getsinger2001; Richardson et al. Reference Richardson, Haug and Netherland2016; Sperry et al. Reference Sperry, Leary, Jones and Ferrell2021; Wersal et al. Reference Wersal, Madsen, Woolf and Eckberg2010). Unlike nonselective herbicides like diquat-dibromide, synthetic auxin herbicides, like 2,4-D and triclopyr largely act as selective compounds, which typically do not adversely affect monocotyledons compared with dicotyledon (broadleaf species) counterparts (Gettys et al. 2020; Madsen Reference Madsen2000). However, as part of the arylpicolinate class of auxins, florpyrauxifen-benzyl associates with a binding-site receptor atypical of common predecessor auxin classes (e.g., 2,4-D belongs within the phenoxy-carboxylate class) (Epp et al. Reference Epp, Alexander, Balko, Buysse, Brewster, Bryan, Daeuble, Fields, Gast, Green, Irvine, Lo, Lowe, Renga and Richburg2016; Hoyerova et al. Reference Hoyerova, Hosek, Quareshy, Li, Klima, Kubes, Yemm, Neve, Tripathi, Bennett and Napier2018; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Sundaram, Armitage, Evans, Hawkes, Kepinski, Ferro and Napier2014). The mobility of florpyrauxifen-benzyl acid metabolites (Haug et al. Reference Haug, Ahmed, Gannon and Richardson2021) and subsequent auxin derivatives within susceptible aquatic plants denotes the unique activity levels of this herbicide, as several selectivity phenomena were evident in the present study. For example, Hofstra and Clayton (Reference Hofstra and Clayton2001) noted that M. triphyllum was not controlled in greenhouse trials using triclopyr at 0.25 to 2.5 mg L−1. Yet rapid sensitivity and plant death was observed for M. triphyllum at very low florpyrauxifen-benzyl concentrations (≤1.2 µg ai L−1). In the same trial, triclopyr did not provide adequate control of L. major in New Zealand (Hofstra and Clayton Reference Hofstra and Clayton2001), while L. major showed rapid sensitivity with no signs of recovery at florpyrauxifen-benzyl concentrations >35 µg ai L−1 in the present study.

While literature documenting submersed plant control with florpyrauxifen-benzyl is still developing at the international scale, results from the present study corroborate the findings of Myriophyllum spp. sensitivity among previous studies (Beets et al. Reference Beets, Heilman and Netherland2019; Haug et al. Reference Haug, Ahmed, Gannon and Richardson2021; Richardson et al. Reference Richardson, Haug and Netherland2016). However, our findings do contradict those originally found by Netherland and Richardson (Reference Netherland and Richardson2016), which indicated greater sensitivity for E. canadensis with EC50 values of 6.9 and 13.1 μg ai L−1, as E. canadensis EC50 required more than twice the maximum labeled concentration of formulated herbicide in this 21-d study. Florpyrauxifen-benzyl degrades primarily through photolysis (1- to 2-d half-life), with secondary degradation occurring through hydrolysis with increasing pH (pH 7 to 9; 111- to 2-d half-life, respectively) (Heilman and Getsinger Reference Heilman and Getsinger2018; MDA 2018). Though unlikely, treatment pH in this study (µ = 8.2) could have nominally influenced herbicide activity on E. canadensis. A rapid conversion of florpyrauxifen-benzyl to the less-active parent acid under growth chamber conditions could have also reduced the observed herbicide activity on the more tolerant invasive plants, although this was not specifically tested for (Netherland and Richardson Reference Netherland and Richardson2016; Richardson et al. Reference Richardson, Haug and Netherland2016; Sperry et al. Reference Sperry, Leary, Jones and Ferrell2021). A more likely explanation for greater E. canadensis sensitivity in prior research is the potential for genotypic differences between naturalized plant populations in New Zealand versus the native range cohorts in North America. In New Zealand, E. canadensis accessions occur solely via clonal propagation, whereas viable seed production can occur within various regions in North America (Swearingen and Bargeron Reference Swearingen and Bargeron2016). Past genetic comparisons were performed within established Hydrocharitaceae populations in New Zealand (Lambertini et al. Reference Lambertini, Riis, Olesen, Clayton, Sorrell and Brix2010); however, this type of study typically focuses on species plasticity and invasion potential within invaded waterways rather than genetic parallels to the endemic plant populations. Further genetic screening comparing test species in the United States and New Zealand would allow for more relevant plant response comparisons for confirmation of this hypothesis.

In conclusion, this study indicates florpyrauxifen-benzyl would be a prospective candidate for L. major management, with further evaluation required to develop tactics that produce adequate control levels for E. canadensis and E. densa. Large-scale mesocosm trials would be beneficial in elucidating E. canadensis whole-plant response to validate plant tolerance metrics shown in this study, as previous outdoor mesocosm experiments showed more favorable results for E. densa control (Howell et al. Reference Howell, Hofstra, Heilman and Richardson2021). Given the sensitivity of M. triphyllum compared with the Hydrocharitaceae tested, any targeted concentration used for invasive plant control in field scenarios would likely seriously injure native Myriophyllum spp. However, resource managers should note that native species, such as M. triphyllum and red pondweed (Potamogeton cheesemanii A. Benn.), generally produce large seedbanks that could support reestablishment following invasive plant eradication programs (Hofstra et al. Reference Hofstra, Clayton, Champion, de Winton, Hamilton, Collier, Quinn and Howard-Williams2018; de Winton and Clayton Reference Clayton1996; de Winton et al. Reference Clayton and Champion2000). As documented in previous studies evaluating florpyrauxifen-benzyl for invasive submersed plant control (Beets et al Reference Beets, Heilman and Netherland2019; Richardson et al. Reference Richardson, Haug and Netherland2016; Sperry et al. Reference Sperry, Leary, Jones and Ferrell2021), future research is needed to test additional native species’ sensitivity for best management guidance. Similarly, future investigations should assess native and invasive species in mixed communities to show side-by-side confirmation of results in field-based plant management scenarios. While small-scale screenings can overestimate herbicide activity on plants (Richardson et al. Reference Richardson, Haug and Netherland2016), this study exemplifies the benefits of alternative small-scale trials for quickly gauging submersed plant response to new herbicide chemistries and provides a foundation for future screening activity that could prove expedient for herbicide registration purposes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Denise Rendle and Susie Elcock for their assistance with plant collection, propagation, and harvesting. Funding for NIWA trials provided through the Strategic Science Investment Fund. SePRO Corporation provided florpyrauxifen-benzyl material for testing. The authors recognize that the coauthor Mark Heilman is employed by SePRO Corporation. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.