Against the background of thawing cross-Strait relations post-2009, the Republic of China (ROC), under the Ma Ying-jeou 馬英九 administration (2008–2016), cautiously advanced the opening of Taiwan's economy to direct investments from mainland China, enabling many mainland Chinese companies to legally establish subsidiaries in Taiwan. Beijing and Taipei signed an Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (ECFA) in 2010 and concluded and ratified a Cross-Strait Bilateral Investment Protection and Promotion Agreement (cross-Strait BIA) in 2012.

The extension of cross-Strait economic integration to accommodate mainland Chinese investments in Taiwan was a bold and far-reaching manoeuvre. Direct investments are not just one-off transactions, as seen in trade, but rather involve companies making strategic, commercial and entrepreneurial decisions that result in the long-term economic presence of an entity from the home economy – the People's Republic of China (PRC or mainland hereafter) – in the host economy, Taiwan. The lasting presence of an entity from a political competitor, as the PRC is for the ROC, could raise concerns about repercussions for the host economy's security, politics and society. Such concerns have already induced many governments to strengthen investment screening procedures and contemplate bans on Chinese companies such as Huawei and Hikvision in sensitive sectors to protect national security. Such worries are particularly acute in the ROC, owing to its unique political and security situation, as Beijing ultimately seeks to unify the island with the mainland. The extreme position in which Taiwan finds itself makes the island a particularly insightful case study for the exploration of the implications of cross-border direct investment for both politics and security.

Economic statecraft offers a useful concept for such an analysis. It is defined as the intentional manipulation of economic interactions to achieve political ends.Footnote 1 This article examines mainland Chinese direct investments in Taiwan from 2008 to 2016 to assess their use by Beijing as an instrument of economic statecraft. Neither academic nor policy literature has offered strong, clear and conclusive evidence on the manipulation of Chinese or other cross-border direct investments to achieve political ends. The existing literature is vague about how direct investments are concretely used for such purposes and how effective this strategy is in the case of Chinese investments. Perspectives on the Chinese state's involvement in cross-border investments range from assumptions that such investments are completely state driven to views that Chinese companies are motivated by profits and are largely independent of the state.

This article takes an important step forward in addressing these shortcomings in the literature. It draws on the concept of economic statecraft, using information gathered from official documents, government statistics, public databases and media reports, as well as first-hand data collected in Taiwan and mainland China between 2014 and 2017. The findings suggest that cross-border direct investments are comparatively ill-suited for deployment as a tool of economic statecraft. Their excessive politicization and the recognition that such investments could be used by Beijing for economic statecraft purposes resulted in a considerable pushback by the government, bureaucrats and civil society in Taiwan against large and sensitive investments. This pushback began under the Ma administration and has continued during the Tsai Ying-wen 蔡英文 presidency. The agency on the Taiwan side prevented Beijing from using mainland Chinese direct investments for political purposes, and Beijing has not openly promoted or supported mainland direct investments in Taiwan. Moreover, cross-border direct investments are by nature less exploitable for political purposes because they involve company-level commercial and entrepreneurial decisions. This sets them apart from other practices that have been used for economic statecraft, such as sanctions or trade restrictions, over which the state has greater influence. Mainland Chinese companies have had limited commercial interests in Taiwan, and the investments that have been made there do not appear to have triggered meaningful political or security externalities in Taiwan. In sum, mainland Chinese direct investments do not represent a particularly effective tool for Beijing to achieve its political ends in Taiwan. Taipei, assuming there was the risk that such investments could be used for economic statecraft purposes, introduced corresponding safeguards and restrictions, and Beijing's strategies to “use business to steer politics,” “use citizens to force the government” and “use economics to promote unification” have not been appropriate in this context.Footnote 2

These findings make important advancements to the research on economic statecraft and multinational enterprises’ cross-border foreign direct investments (FDI). While traditional tools of economic statecraft such as sanctions or trade have been well documented in the literature, the feasibility of FDI as a tool of economic statecraft has been insufficiently examined. Studies on FDI, predominantly in business and management, have focused primarily on its economic impact, but further insights are needed on the political and security implications of such investments.Footnote 3

In addition, we offer a new perspective to the literature on cross-Strait investments, which has to date focused entirely on Taiwanese investments on the mainland. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first detailed scholarly examination of investments in the opposite direction, from mainland China to Taiwan, and the first study to examine the constraints on mainland Chinese investments as they encounter the agency of the government, bureaucrats and civil society in Taiwan.

The rest of this article is structured as follows. The next section examines the concept of economic statecraft and its application in the cross-Strait context. This is followed by an introduction of the research design. Three sections then analyse the feasibility of using mainland Chinese direct investments in Taiwan as a tool of economic statecraft, focusing on the relaxation of rules and policies on cross-Strait investments post-2009, the role of the PRC government and mainland companies, and the political and security externalities of such investments. A final section concludes with an assessment of FDI as a tool of economic statecraft.

Economic Statecraft and Cross-Strait Relations

Economic statecraft happens when the state intentionally manipulates the strategic, political or security externalities generated by commercial actors to further its objectives.Footnote 4 Such manipulation often occurs via economic policies such as incentives or restrictions. Originally, the concept of economic statecraft was applied to coercive measures such as sanctions.Footnote 5 It was then expanded to include many other economic activities, such as taxation, trade agreements, embargos, the freezing of assets, currency manipulation, tariffs or special subsidies.Footnote 6 However, applying the concept of economic statecraft to cross-border direct investments and FDI still requires further specification, an ambition this study pursues. Evidence on whether such investments can be an effective deployable tool of economic statecraft is still lacking.

In parallel with its increasing power and international reach, China has a growing ability to use economic statecraft to support its geopolitical ambitions. Many examples have been provided in which the PRC government has used traditional forms of economic statecraft, both globally and in its relations with Taiwan. For instance, Beijing downgrades trade relations with countries whose governments or individuals are viewed as having offended China. For example, the PRC reduced trade with Lithuania following a dispute over the terminology used for the Taiwanese Representative Office in Vilnius, and China's economic enticements to countries along the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) have been interpreted as acts of economic statecraft.Footnote 7

In its relations with Taiwan, Beijing has traditionally used both sticks and carrots, deploying coercive means while also offering enticements and favours to select economic actors, with mixed success. For example, Taiwanese firms on the mainland have been offered preferential treatment and tax benefits since the 1980s.Footnote 8 However, around the turn of the century, Taiwanese companies whose managers were too close to the pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and who advocated for Taiwanese independence were also threatened and coerced by Beijing.Footnote 9 From the mid-2000s, focus shifted away from sanctions and moved much more firmly towards enticements and favours, as the Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 administration adopted a strategy to “win over the hearts and minds of the Taiwanese people” through positive engagement and economic integration.Footnote 10 This strategy targeted companies and people directly in Taiwan – for example, farmers and fish farmersFootnote 11 – who were offered preferential trade arrangements in an attempt to sway them from voting for the DPP.Footnote 12 Some have suggested that such efforts could, to some extent, have influenced changes in public sentiment.Footnote 13 Others, however, are more sceptical about the effectiveness of these attempts at economic statecraft.Footnote 14 Moreover, the literature has yet to examine or determine whether mainland Chinese direct investment in Taiwan has become another tool of PRC economic statecraft.

Although the concept of economic statecraft is widely used, recognizing when it is being implemented can be difficult.Footnote 15 This study addresses this challenge by illuminating three necessary prerequisites for effectively engaging in economic statecraft: intentionality, state control and the generation of security externalities.

Cross-border direct investments can become a tool of economic statecraft if the home government intentionally manipulates the associated commercial actors, such as investing companies, to achieve political ends. Establishing whether such intentionality is present can be straightforward with many traditional forms of economic statecraft. For example, a government introducing sanctions expresses its intentions to achieve political ends by laying out the conditions to be fulfilled for sanctions to be lifted. The PRC's policies in the mid-2000s to open up its fruit markets to Taiwanese farmers were initiated amid historically unprecedented visits by leaders of the Kuomintang to mainland China. This was, therefore, an obvious attempt to bolster opposition to the DPP in Taiwan.Footnote 16 But when such intentionality cannot be immediately established, as is usually the case for cross-border direct investments, verifying the presence of economic statecraft becomes trickier. Companies and their investments can generate political and security externalities on their own, so only when the home government deliberately seeks to nurture and generate their externalities can economic statecraft be considered present.Footnote 17

Moreover, the home government must control the relevant commercial actors, directing or manipulating them to advance the generation of political and security externalities.Footnote 18 In the case of cross-border direct investments, the state needs to persuade companies to invest. In democratic societies and liberal market economies, governments have limited command over the actions and decisions of companies, beyond the possibility to influence behaviour through incentives or subsidies. Because most multinational enterprises have originated from such economies in the past, there was little need to examine if or how FDI was being used as a tool of economic statecraft. However, in China's authoritarian state capitalist economic system, where the government interacts more closely with domestic business groups, control over commercial actors may be more likely.

Yet even in China, despite widespread state and mixed ownership, greater coordination of the enterprise sector and state intervention in markets, there has been mixed evidence on the extent to which the state controls mainland companies. State–enterprise relations in the PRC are complex and, in many instances, the state cannot operate as a central actor controlling all its commercial actors in a top-down fashion.Footnote 19 Some studies have demonstrated the state's inability to monitor its state-owned enterprises (SOEs) so they conform with Beijing's policy objectives when overseas.Footnote 20 Moreover, a considerable number of Chinese companies are private and profit driven and have limited interest or ability to follow government directives. Private companies are generally subject to less state control compared to SOEs,Footnote 21 yet the relationship between private entrepreneurs and the Chinese government can be close, with companies still dependent on the party-state.Footnote 22

Finally, investing companies need to actually generate the corresponding political and security externalities within the host economy.Footnote 23 Mainland Chinese direct investment could generate political and security externalities in Taiwan if it advances Beijing's objective to achieve interest transformation within Taiwanese society to curtail moves towards independence, or if it undermines Taiwanese politics and security.Footnote 24 The extent of externalities generated may vary by the amount of capital invested, the size of the investing mainland firms, the entry mode (for example, greenfield, acquisition or sales office), ownership of the investing firm (state-owned, mixed or privately owned) and industrial sector. An acquisition of a strategically important firm in the semiconductor or media industries would, for example, bring greater political and security implications than would establishing a sales office to import and market manufactured goods from the mainland. Yet here again, the link between cross-border direct investments and political and security externalities is not well established in the literature.

Research Design

Taiwan presents itself as an ideal case to examine the utilization of cross-border direct investment as an instrument of the PRC's economic statecraft. Beijing has explicit political objectives in Taiwan, viewing the island as a renegade province that must be brought closer into mainland China's orbit to enhance the prospects of future unification. Nowhere else are Beijing's political priorities so fundamental than in the cross-Strait relationship, a circumstance providing a particularly suitable context for exploring the utility of exploiting cross-border direct investments to achieve political ends. Analytically, the lower transaction costs in business relations across the Taiwan Strait owing to cultural and linguistic commonalities help to control other common factors influencing investment decisions, such as the liabilities and costs that result from doing business in a culturally, politically and economically unfamiliar environment.Footnote 25 Taiwan also provides an excellent case study to examine how smaller actors deal with the economic statecraft of strategic rivals and hegemons.

This research draws on a wide set of data and literature on mainland Chinese direct investments in Taiwan. Its most important data source is a set of 66 semi-structured interviews with actors from business, politics and civil society, which were conducted during fieldwork in mainland China and Taiwan from 2014 to 2016. In Taipei, 19 interviews were conducted at government ministries dealing with economic issues, semi-governmental economic research institutes and with mainland Chinese investors. Four interviews were conducted with individuals affiliated with the Hsinchu Science Park of Industrial Technology Research Institute. In Beijing, 12 interviews were conducted at mainland Chinese enterprises (both state-owned and private), with academics at the Research Institute of Taiwan Studies and also with Taiwanese businesspeople. Nine interviews were conducted in Shanghai and 22 in Kunshan 昆山市, mostly at mainland Chinese and Taiwanese enterprises, and with two local government officials in the commercial bureau in Kunshan. Each interview lasted between 60 and 90 minutes long and was conducted by the same interviewer. Eight interviewees were interviewed twice; three were interviewed three times.

The interviews were transcribed, systematically analysed and coded after the fieldwork. They were conducted in Chinese, and the quotes were translated into English. The names of the interviewees are concealed to guarantee anonymity. The information obtained from the interviews was complemented and verified with additional data and information from various sources, including relevant statistics, official documents such as laws and regulations, and an extensive list of specific investment cases that was compiled based on a large number of media articles, information from company websites and Bureau van Dijk's Orbis database. All this data provided rich and detailed information and offered a variety of stakeholder perspectives.

The analysis focuses on direct investments by companies, as they are more prone to generate externalities than portfolio investments or investments by individuals, and it examines the period of the Ma Ying-jeou administration (2008–2016). During this time, Taiwan opened its economy to mainland Chinese direct investments and concluded associated cross-Strait agreements. Prior to 2008, when Chen Shuibian 陳水扁 and the DPP were in power, mainland Chinese direct investment in Taiwan was very limited and confined to specific deals and some opening up for investments in specified sectors such as real estate.Footnote 26 Since the election of the DPP's Tsai Ing-wen 蔡英文 as Taiwanese president in 2016, official exchanges with the mainland have been cut.Footnote 27 There has been a freeze on further investment liberalization but no significant changes have been made to the regulations on mainland investment.Footnote 28 Because most investment liberalization and the associated influx of mainland investments occurred during the Ma Ying-jeou administration, it forms an ideal fixed time period for examining the utilization of mainland Chinese direct investments as an instrument of economic statecraft.

The Relaxation of Rules and Policies on Cross-Strait Investments Post-2009

On 30 June 2009, the Executive Yuan in Taiwan promulgated the “Regulations for mainland people coming to Taiwan for investment” (modified on 30 December).Footnote 29 This was the starting point for a series of rules, policies and cross-Strait agreements that further liberalized direct investments across the Taiwan Strait over the following years. But while many of these rules, policies and agreements presented themselves as significant moves towards welcoming investment from mainland China, they were often not fully implemented in practice. Moreover, they included substantial safeguards that gave Taipei considerable agency over the ability of mainland Chinese companies to make investments and prevented Beijing from utilizing such investments for economic statecraft purposes.

Although the ECFA, which was concluded on 29 June 2010, immediately lowered some trade barriers between mainland China and Taiwan, it was more significant as a framework within which more complex agreements, such as on investment and services, were to be negotiated. The ambition was to achieve greater economic integration, and mainland China and Taiwan likely aimed for these agreements to generate vested interests,Footnote 30 which would push the question of independence and unification off the cross-Strait political agenda.Footnote 31 For Beijing, after decades of a near-complete absence in Taiwan, having mainland Chinese companies present on the island likely symbolized an important strategic step forwards in its long-term political ambitions regarding Taiwan.

At the time the ECFA was concluded, the Taiwan government promoted mainland Chinese investments through a “Bridging cross-Strait economic cooperation” project.Footnote 32 This opened many sectors to mainland Chinese investment, as shown in Table 1. Mainland Chinese travel and tourism to Taiwan was also permitted from July 2008 onwards and was an important facilitator of investments.Footnote 33

Table 1. Liberalization in Taiwan towards Investment from Mainland China since 2009

Sources: Mainland Affairs Council, ROC 2013; “Taiwan readies for third wave of Chinese investment.” Taipei Times, 20 March 2012, http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/biz/archives/2012/03/20/2003528196. Accessed 13 February 2016.

Note: *Initially, there were 192 categories in 2009; a further 12 were added in 2010 and another one category in early 2011. Figures in parentheses indicate the percentage of the total sector opened by that time.

Alongside this opening up to the PRC, the ROC government simultaneously introduced and kept various regulations and restrictions in place in its cautious approach to mainland investments, even under the Ma administration.Footnote 34 It can be argued that this approach was taken precisely to prevent Beijing from utilizing mainland investment for economic statecraft purposes and to forestall any potential political or security externalities that could emanate from mainland investments. In particular, there was a continuing mistrust of mainland investment among Taiwan's bureaucrats, resulting in a rift between the intentions of the presidential office and execution by bureaucrats.Footnote 35 Specifically, stringent limitations were placed on the degree of ownership and managerial control a mainland Chinese firm could exercise over a company in Taiwan, especially in high-technology sectors such as telecommunications and networks, semiconductors and machinery. In some cases, ownership was limited to a mere 10 per cent of a Taiwanese company, and the mainland Chinese firm was required to disclose its associated business strategies. Investments in sensitive sectors such as the media remained partially restricted or even fully prohibited. The Ministry of Economic Affairs (Overseas Chinese and Foreign) Investment Commission (MOEAIC) also instituted onerous investment screening, monitoring and approval procedures that were more rigid for mainland Chinese investments than for investors from elsewhere.Footnote 36 Assessment of any mainland investment involved the Mainland Affairs Council and other ministries.Footnote 37 This gave bureaucrats a determining role in deciding which investments to admit. Screening was especially stringent for larger investments, given their greater potential for political and security externalities; criteria for approval of smaller wholesale and retail activities were more relaxed. Such strict rules and procedures discouraged several potential mainland Chinese investors from investing in Taiwan;Footnote 38 others were blocked or did not proceed as intended.Footnote 39 “The key to the success of mainland investment lies in whether the investment application [was] approved by the Taiwanese government,” explained one interviewee.Footnote 40

In addition, despite travel from the mainland being permitted, regulations on the movement of mainland Chinese staff remained very rigid.Footnote 41 One mainland Chinese investor explained: “I [could] only get a 15-day visiting visa each time [I visited Taiwan]. This is extremely difficult for me as an investor in Taiwan. It is a very limited timeframe to set up a business.”Footnote 42

On 9 August 2012, the Cross-Strait BIA was signed. Its format was much like a standard international investment treaty, although some clauses considered the unique circumstances of the relationship between mainland China and Taiwan.Footnote 43 At least on paper, the Cross-Strait BIA cautiously liberalized investments between both sides, particularly by offering mainland investors similar conditions to those offered to companies from Taiwan and elsewhere (for instance, post-establishment national treatment and pre-establishment most favoured nation treatment, respectively). But the agreement left many loopholes concerning the speed and extent of liberalization – in line with the cautious approach being taken by the ROC. For example, it allowed laws, regulations and restrictions that did not conform with the commitment to liberalization to be maintained indefinitely. Moreover, new restrictive laws were enacted when necessary for security reasons. In addition, the Cross-Strait BIA continued to allow the Taiwan authorities to review and approve or block new mainland Chinese investments via the vigorous screening procedure. All this enabled Taipei to control the speed at which restrictions on mainland Chinese investments were relaxed.

The Cross-Strait BIA did not face significant civil society opposition in Taiwan, as it also supported Taiwanese investors in mainland China. But the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement (CSSTA), subsequently negotiated by the Ma administration and signed on 21 July 2013, was met with considerable opposition. The agreement committed Taiwan to opening 64 sectors to mainland Chinese investment, including more sensitive areas such as tourism, hotels, printing and medical services.Footnote 44 But attempts to push the agreement, allegedly negotiated secretly, through the ratification process without prior public consultation, triggered student protests that culminated in the occupation of the Legislative Yuan for 24 days. These protests and the associated “Sunflower” movement, which were mobilized out of concerns that Beijing could use investments and increased economic links for political purposes and economic statecraft, eventually halted the CSSTA's ratification. The scuppering of the CSSTA resulted in Ma being viewed as a “lame duck president,” at least as far as economic liberalization towards mainland China was concerned, already before the end of his first term.Footnote 45

Mainland Chinese companies were faced with many obstacles in order to invest in Taiwan. Take, for example, Tsinghua Unigroup, which unveiled plans in December 2015 to purchase 25 per cent stakes in two Taiwanese chip-testing companies: Siliconware Precision Industries Co. (SPIL) and ChipMOS Technologies Inc.Footnote 46 Tsinghua Unigroup was a large and complex mainland Chinese semi-state-owned business group and chipmaker, partially financed and staffed by Tsinghua University in Beijing and supported by the government.Footnote 47 The proposed deals were welcomed by Taiwanese ICT design companies, which reasoned that “working with Tsinghua Unigroup would enable further integration of Taiwanese ICT design into the international market.”Footnote 48 However, despite the two deals involving acquisitions of minority stakes, they were strongly opposed by Taiwanese academics and civil society.Footnote 49 The Taiwan government viewed the deals as a national security issue because the semiconductor industry is a sensitive sector in Taiwan with a key role in assuring its industrial competitiveness.Footnote 50 To assuage such concerns, the chairman and CEO of Tsinghua Unigroup, Zhao Weiguo 趙偉國, expressed on many occasions that such cross-border acquisitions are generally motivated by market needs and not driven by the mainland Chinese government's instructions.Footnote 51 Tsinghua Unigroup pledged adherence to Taiwanese regulations on investment from the mainland by declaring its intention not to gain full control over SPIL and presenting an industry cooperation plan.Footnote 52 These assurances were not enough to convince Taipei, however, and both deals were eventually shelved.

The numerous restrictions and obstacles installed by Taiwan's government, bureaucrats and civil society in response to fears that Beijing could use investments as devices of economic statecraft minimized the extent to which mainland Chinese firms were willing or able to make investments on the island.Footnote 53 After the public protests over the CSSTA, policy uncertainty and concerns about the stability of the investment environment became major issues of concern for mainland Chinese investors.Footnote 54 This has worsened since Tsai Ing-wen and the pro-independence DPP took power in 2016, with the subsequent cooling of cross-Strait relations and communications. As shown in Table 2, mainland direct investments in Taiwan peaked in the late Ma years and have been in decline since.

Table 2. ROC Investment Permits Granted to Mainland Chinese, 2009–2021 (US$ million)

Source: Ministry of Economic Affairs (ROC) Investment Commission, Monthly Report, February 2022.

Taiwan's cautious approach to opening the island's economy to mainland Chinese direct investments, combined with bureaucratic resistance and civil society opposition to excessive liberalization, is a factor that complicated, if not inhibited, any exploitation of cross-border direct investments for economic statecraft purposes. Indeed, the more the government, bureaucrats and civil society in Taiwan feared that Beijing might use such investments for PRC economic statecraft, the more they erected safeguards and opposed the investments. Direct investments are by nature easily politicized, as they involve a permanent foreign presence in the host economy and generate externalities there. Such politicization prompted the installation of government safeguards and intensified public opposition towards mainland Chinese investments in Taiwan, reducing any possibility that Beijing might use such investments to pursue its own political ends.

Government Backing and Firm-level Motivations

To establish the intentionality of the mainland Chinese government to use cross-border direct investments for economic statecraft purposes, it is useful to examine the extent to which Beijing has offered incentives, promotion or other support to cross-Strait investments that promised to further its political and security objectives. In the early 2000s, China introduced a “going out” policy, which encouraged outward investments that supported enhancing the country's energy security, technological capabilities and access to foreign markets and trade links. Beijing, spearheaded by the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM), introduced a complex and sophisticated system of institutions, laws and measures to encourage, support, manage and control outward FDI, with some of these incentives targeted at investments in specific countries and sectors.Footnote 55 The communicated intention of the policy and associated incentives has, however, been the development of the mainland Chinese economy through associated economic gains rather than political or security objectives.Footnote 56 These industrial policy ambitions should, analytically, fall outside the realm of economic statecraft, which seeks political rather than economic ends. An exception might be achieving greater energy security from mining investments abroad, although this goal would not apply to Taiwan with its limited natural resources.Footnote 57 The “going out” policy and its associated incentives also run counter to the established notion that the goal of economic statecraft is to “compel or deter policy changes in other states” and “influence policy choices elsewhere,” rather than to achieve outcomes in the home state such as energy security.Footnote 58

Under its “going out” strategy, MOFCOM offered companies detailed information about investing in most countries in the world; however, Taiwan was not covered by this scheme, nor was it on the list of investment destinations for which companies were eligible for incentives. Instead, the State Council's Taiwan Affairs Office (TAO) offered information on its own website that was specific to investing in Taiwan.Footnote 59 The website provided an introduction to Taiwan's general economic conditions and its main industrial sectors as well as contact information for mainland investors needing consultancy. This separation may be owing to Taiwan's special status in the eyes of Beijing. Several interviewed mainland investors in Taiwan confirmed the absence of any incentives offered by the PRC government to encourage them to invest in Taiwan.Footnote 60 They also clarified that their government had not provided them with any special preferential conditions.Footnote 61 Beijing's lack of promotion was even acknowledged by Taiwan's politicians. On the occasion of the tenth anniversary of Taiwan's opening up to mainland investments on 30 June 2019, the spokesman and deputy chairman of the Mainland Affairs Council in Taiwan confirmed that Beijing had so far not provided mainland businesses with any incentives to invest in Taiwan.Footnote 62

A number of consultancies and local government-affiliated entities did offer more detailed support and organized investment forums for mainland companies interested in Taiwan as an investment destination.Footnote 63 But these efforts were limited. An official of the Beijing Taiwan Affairs Office, whose job it was to search for investment opportunities for potential mainland investors in Taiwan, described the scant resources available to encourage mainland companies to invest in Taiwan: “This office [in Taipei] only has two people, me and the secretary, and my work is to search among all kinds of businesses in Taiwan to see whether there are suitable investment opportunities for mainland businesses.”Footnote 64

There is, therefore, no concrete indication of the PRC government's intention to use mainland Chinese direct investments as an instrument of economic statecraft. In fact, the government's reluctance to actively promote investments in Taiwan might indicate a desire to avoid creating the impression that mainland Chinese investments in Taiwan were state driven, an impression that could have provoked further restrictions and more opposition in Taiwan. Moreover, Beijing already had other options in its economic statecraft toolbox. As discussed above, trade and Taiwanese investments in mainland China have allowed the government to influence and coerce Taiwan.Footnote 65 More recently, new groups of commercial actors have emerged in cross-Strait relations that could be used for economic statecraft purposes. For example, Taiwanese factories on the mainland are increasingly being purchased and moved fully into mainland Chinese hands while still retaining Taiwanese management.Footnote 66 In addition, mainland firms have actively headhunted highly skilled Taiwanese engineers, enticing them with attractive salaries and employment packages.Footnote 67 In some cases, they lure entire teams away from the research and development departments of Taiwanese companies.Footnote 68 It is feasible that these Taiwanese managers and engineers – rather than mainland investments – could be more effectively used by Beijing to achieve its political ends in Taiwan, especially when the managers and engineers eventually return to Taiwan. The case of the Want Want Group, a Taiwanese company that prospered in the mainland in the 1990s, illustrates this point. Following the company's purchase of a major Taiwanese newspaper, China Times, in the 2000s, the paper took a positive stance in its reporting on mainland China, which helped the Want Want Group's chairman, Tsai Eng-Meng 蔡衍明, to consolidate his business interests on the mainland.Footnote 69

Mainland Chinese companies mirrored the PRC government's lacklustre approach to investment in Taiwan and were not particularly motivated to invest there. Mainland Chinese managers tended not to consider Taiwan as a particularly promising market. Despite offering 24 million relatively wealthy customers with potentially similar tastes and preferences to mainlanders, the market's isolated position reduced its overall potential for market-seeking investments, as there are no third markets nearby which could be serviced from Taiwan. As the CEO of a mainland Chinese private company explained: “We did not consider investing in Taiwan because Taiwan's domestic market is not big enough.”Footnote 70 A slightly more interested response from an SOE manager was: “we are still evaluating the possibility of investing in Taiwan.”Footnote 71 Moreover, Taiwan's proximity to the mainland could render a local presence unnecessary, as products and services could be offered and shipped directly from mainland China. Among the market-seeking investments made in Taiwan, the establishment of (arguably smaller) trade-supporting stores, branch offices for wholesale and retail (see Table 3), and maintenance and repair services for products shipped from mainland China dominated.Footnote 72

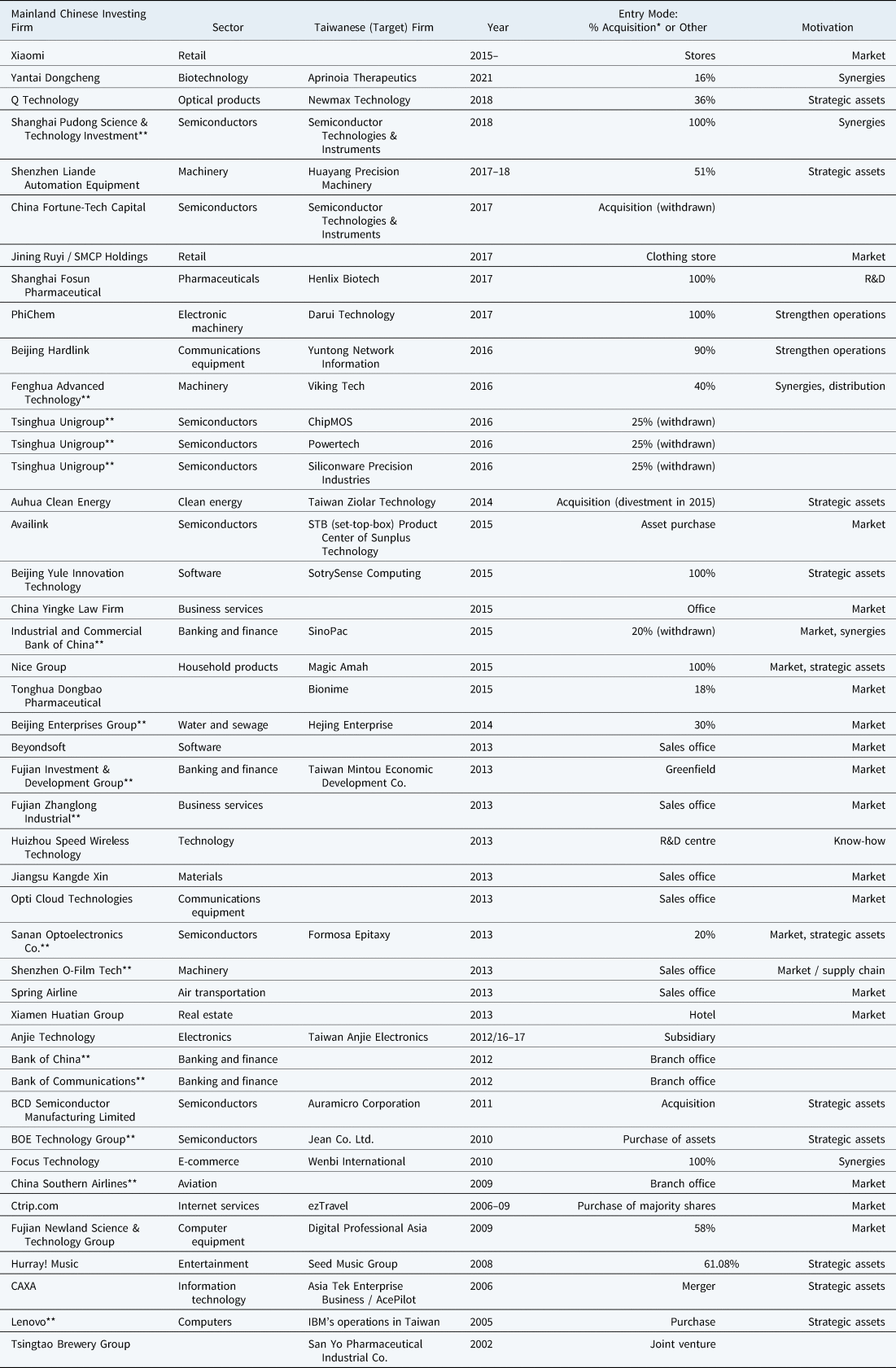

Table 3. Examples of Mainland Chinese Direct Investments in Taiwan

Source: Database compiled by authors based on media reports, company information and the Bureau van Dijk Orbis database.

Notes: *includes share purchases; ** state-owned or with state capital.

Second, although Taiwan had a technological edge over mainland China in key strategic industries such as semiconductors, its technology and innovation lagged behind the international technology frontier, reducing Taiwan's attraction as a destination for investment in technologies and strategic assets. The narrower technological gap between mainland China and Taiwan created a preference for more advanced science and technology hubs in other countries, such as Silicon Valley in the United States. “Although we have few cultural and language differences with Taiwanese firms, we didn't consider investing in Taiwan because … Taiwan's core technology is not that mature,” explained the CEO of a mainland Chinese IT firm.Footnote 73 Another mainland Chinese interviewee put it more bluntly: “The innovation capacity of Taiwanese factories has slowed down, therefore we would prefer to work with German, Japanese or American companies.”Footnote 74 Among the mainland Chinese investments that did seek advanced technologies and other strategic assets in Taiwan, many were minority stake acquisitions, as shown in Table 3.

Mainland Chinese investors’ interest in Taiwanese skills focused on the semiconductor industry, where investments could open access to the tight-knit groups of highly dedicated and well-trained engineers that characterize this industry.Footnote 75 According to some mainland investor interviewees, Taiwan's human capital was an attraction.Footnote 76 Management know-how is strong throughout Taiwan's services industries,Footnote 77 and highly skilled individuals are often cheaper to hire there than in mainland China.Footnote 78

Third, with low-skilled labour more available and cheaper in mainland China, it was not viable for mainland Chinese companies to seek cost advantages through investments in Taiwan. Further, as a small island of approximately 36,000 km2, Taiwan offers little space for large-scale construction and infrastructure projects and no significant opportunities for the mining of natural resources. All of these factors negatively affected the business case for investing in Taiwan among mainland Chinese companies.

State control is most likely to occur when the interests of the state are compatible with those of commercial actors, as these are circumstances under which companies follow government directives more willingly (or even implicitly).Footnote 79 However, mainland Chinese companies showed limited interest in investing in Taiwan. Combined with a lack of government backing for such investments, and the general uncertainty about how Beijing could manipulate its commercial actors, as discussed above, this suggests that state control over mainland Chinese direct investment in Taiwan was limited, diminishing the potential of such investments to be used as a tool of economic statecraft by Beijing.

Political and Security Externalities of Mainland Chinese Direct Investments in Taiwan

The trends and patterns of mainland Chinese direct investments in Taiwan suggest that the potential for the generation of political and security externalities has been limited. Because of the continuing restrictions and the low interest among mainland Chinese companies in investing in Taiwan, the magnitude and embeddedness of mainland Chinese investments in Taiwan have remained modest. As the Taiwanese official data in Table 2 indicate, mainland Chinese investment stock only surpassed the US$2.5 billion mark in 2021, which amounts to a mere 2.7 per cent of all overseas investments made in Taiwan since 2009.Footnote 80 MOFCOM data estimate this figure to be even lower, at US$1.25 billion in 2019, or approximately 0.06 per cent of the total accumulated assets owned by mainland Chinese multinationals worldwide.Footnote 81

This is not enough investment to make any meaningful contribution to boosting economic interdependence between the two sides of the Strait to the degree that widespread interest transformation is promoted in Taiwan. Although every investment would intensify person-to-person interaction between mainland Chinese and Taiwanese as staff circulate between company units on both sides of the Strait and mainland Chinese senior management or other charismatic individuals are presented with opportunities to influence the political views of Taiwanese employees, in aggregate any such effects are likely to be limited. Similarly, the engagement of relatively few mainland Chinese investors with broader communities in Taiwan, such as business partners, customers, local administrations and political actors, as part of their business activities, is unlikely to influence local values and political opinion.

Moreover, investments that were made are not necessarily the type that could generate significant security externalities. For example, as Table 3 shows, only some investments were in technology-intensive sectors and by SOEs, and many investments were by private firms in inconspicuous sectors. Many projects were just sales offices, branch offices or stores, with limited potential to generate externalities owing to their small size and focus on sales and marketing rather than productive activities. Acquisitions were infrequent and typically with only partial ownership stakes held by the mainland Chinese company. This reduces the possibility of meaningful technology transfer (or technology “theft”) from the acquired company to the parent company (in fact, technology transfer might not work unless facilitated by the Taiwanese workforce, who hold the necessary tacit know-how). More generally, there is insufficient documented evidence of mainland Chinese investments in Taiwan being used as a platform for malicious activities or espionage, with only some of the sectors in Table 3 offering any potential for the undertaking of such activities.

Conclusion

This study examines the effectiveness of utilizing cross-border direct investment as an instrument of economic statecraft through an analysis of mainland Chinese direct investments in Taiwan. The findings indicate that using such investments for economic statecraft purposes is challenging and fraught with problems and difficulties. In Taiwan, the politicization of cross-border direct investments, and the mere possibility that mainland Chinese direct investments could be an instrument of Beijing's economic statecraft, prompted stronger government safeguards, bureaucratic resistance and public opposition to such investments. Stakeholders in Taiwan, therefore, have the agency to prevent Beijing from using cross-border investments as an instrument of economic statecraft. Such agency is much less prevalent with other forms of economic statecraft. For example, sanctions or trade restrictions can only be responded to with countersanctions or retaliative restrictions, which would not be effective if the responding state were weak. But as direct investments require a company's presence in the host economy, local stakeholders have greater agency, undermining attempts to use such investments for political ends. It may be because of this reason that Beijing's backing of mainland Chinese direct investments in Taiwan has been lacklustre, suggesting limited intentionality to use cross-border direct investments for economic statecraft purposes. Taiwan responded to the risk of investments being used for economic statecraft with safeguards and restrictions, rendering any such attempts futile. Beijing would be better off focusing on the other forms of economic statecraft which Taipei has limited agency to prevent.

In addition, mainland Chinese companies expressed little interest in investing in Taiwan, which indicates that the behaviour of relevant commercial actors has not aligned with any ambition to be strongly involved in Taiwan for political purposes. It would have been hard for Beijing to control the investment behaviour of companies with limited business interests in Taiwan, regardless of the strength of state–enterprise relations in mainland China. The lack of a business case and the political and administrative hurdles facing mainland Chinese investors in Taiwan limited the size of their investments and prevented them from becoming embedded in Taiwan, inhibiting the generation of any widespread and transformative political and security externalities in Taiwan. As a result, mainland Chinese direct investments have not been an effective instrument of economic statecraft.

Few studies have taken on the challenge of offering systematic and evidence-based analysis of how companies and their cross-border direct investments can be utilized as instruments of economic statecraft. This study is among the first to provide such an investigation, offering important theoretical considerations and new empirical insights. It has examined a rather extreme case involving two economies experiencing severe political differences owing to unique historical circumstances, but many of the issues experienced by Taiwan in its investment relations with mainland China are being encountered elsewhere, even if to a lesser degree – for instance, Chinese investment in Malaysia.Footnote 82 The current mood in geopolitics is shifting towards greater strategic rivalry and growing mistrust between China, the West and other countries, with talk about decoupling becoming increasingly common and exacerbating concerns about Chinese investments in many countries, similar to those experienced in Taiwan.

Future studies need to identify whether other forms of cross-border direct investments and FDI – involving other countries and companies – offer additional or different insights on the effectiveness of their use as instruments of economic statecraft. An industry-specific analysis would be of great value, as economic statecraft may be particularly relevant in security-related and politically sensitive sectors. Differentiating by entry mode, especially comparing the political and security externalities of acquisitions versus greenfield investments, would be another worthwhile next step in researching this important issue. Many more studies on the political and security externalities of FDI are needed.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the generous funding support received from the CCK Foundation, research grant RG013-U-13. We would also like to thank Professor T.J. Cheng and all reviewers for their constructive suggestions on the article, Chang Su for providing research assistance, and the anonymous interviewees for taking the time to participate in the project.

Competing interests

None.

Chun-Yi LEE is an associate professor in the School of Politics and International Relations, and director of the Taiwan Research Hub at the University of Nottingham. Her first book, Taiwanese Business or Chinese Security Asset?, was published by Routledge in 2011. She is currently working on her second monograph, on semiconductor manufacturing and geopolitics. She is editor-in-chief of the online academic magazine, Taiwan Insight, and co-editor of the “Taiwan and World Affairs” book series with Palgrave.

Jan KNOERICH is a senior lecturer in the economy of China at the Lau China Institute, School of Global Affairs, King's College London. His research examines the business, political economy and development dimensions of Chinese outward direct investment. Dr Knoerich's work has appeared in leading academic journals such as New Political Economy, Journal of World Business and Chinese Journal of International Politics, and he has written several books and book chapters. His research has received funding support from the British Academy, Leverhulme Trust and the Economic and Social Research Council. Dr Knoerich has been a consultant for the United Nations, European Union and various think tanks. He holds a PhD in economics from SOAS University of London.