Introduction

What legislators can say and do in any given context is heavily influenced by the rules and norms of their institution (Mackay, Kenny, and Chappell Reference Mackay, Kenny and Chappell2010; March and Olsen Reference March and Olsen1984). In Westminster-style parliaments, party discipline has been shown to be a constraining factor in the substantive representation of women (Childs Reference Childs2004; Rayment Reference Rayment2024; Tremblay Reference Tremblay1998; Young Reference Young, Arscott and Trimble1997). This is due in part to the system of responsible government, where the executive sits in the legislature; to stay in power, the government must maintain 50%+1 of the votes in the lower house, leading to strict codes of behavior for legislative voting. Passing legislation is a high-stakes game. Thus, party discipline is paramount, meaning that it mediates policy outcomes for women.

But this article turns its attention away from policy outcomes and toward the policy making process (see Celis and Childs Reference Celis and Childs2020; Franceschet and Piscopo Reference Franceschet and Piscopo2008). I examine legislators’ inclination to discuss women in a relatively relaxed policy making environment, where policy makers face little influence from party discipline and have a lot of latitude to pursue their own policy interests. The Canadian Senate offers a low-partisanship environment outside the media glare, due to its appointed nature and its position as the weaker house in Canada’s bicameral parliament. Because the government does not need to maintain the confidence of the majority of the Senate to stay in power, it has historically been a less-partisan institution. But its membership has long relied on party patronage appointments, leading to critique over the legitimacy of senators in the legislative process. Reforms to the Senate in 2015 created a less-partisan, merit-based appointment process. As part of the reforms, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has only appointed senators on the condition that they do not join a political party. As a result, independent members are now the majority in the Senate. This article studies transcripts from Canadian Senate committee meetings to determine the effects of partisanship (and lack thereof) on legislators’ willingness to discuss women’s interests.

Using Siow’s (Reference Siow2023) concept of constitutive representation, I examine legislators’ willingness to bring up women and their issues in parliament. Is gender an important factor in policy making discussions? Are women, as a constituency, considered in policy making discussions? And who is bringing their issues and interests to the table? In this study, I examine the frequency of senators’ discussions about women during their committee meetings. The article develops and tests hypotheses related to senators’ frequency of speech about gender and women, including whether senators’ sex or partisanship affects their willingness to talk about women and whether the reforms have caused any changes in this regard. It finds that senators’ sex is the key predictive factor here; women senators talk about gender and women more than their colleagues do, regardless of party, age, or tenure. Moreover, women senators who sit on committees with a critical mass of women members (30% or greater) are more likely to talk about gender and women.

Though the Canadian case is the focus here, the article is instructive for other contexts, including legislatures with a high number of independent members (such as the British House of Lords), nonpartisan municipal councils common in North America, and less-partisan supranational institutions (such as the European Parliament). The findings shed light on the value of low-party discipline legislatures when it comes to the representation of women. Moreover, they offer insight into the constraining factors that limit the representation of women in legislative contexts with strong party discipline.

Constraining and Promoting Women’s Representation

Critical Mass: Enabling Substantive Representation?

Theorized by Pitkin (Reference Pitkin1967), substantive representation is defined as a representative “acting for” her constituents and their interests. Pitkin contrasts this with descriptive representation, which is the number of representatives that look like, or “stand for,” their constituents. For Pitkin, substantive representation is the most important type of representation because it bridges a representative and her constituents. The study of substantive representation turns an eye toward the actions of legislators, especially whether they work toward favorable policy outcomes for their constituents.

Phillips (Reference Phillips1995) advances the idea of the “politics of presence,” which maintains that women can only be substantively represented in a legislature if they are physically present there. Mansbridge (Reference Mansbridge1999) further develops this idea, suggesting that women are in a better position to use their experiential knowledge to represent women’s interests and that their presence in the legislature creates a stronger connection between the government and women in society. In brief, the politics of presence relies on the inclusion of women’s diverse worldviews in policy making processes and the symbolism of their place in the legislature, resulting in improved outcomes for women in the polity.

The critical mass theory of substantive representation emphasizes the politics of presence and the link between descriptive and substantive representation. Critical mass suggests that when a certain threshold of women is reached in the legislature (usually estimated at 30%), a chain reaction will begin, enabling women to more effectively advocate for women’s interests (Dahlerup Reference Dahlerup1988). The 30% threshold follows previous literature on the critical mass of women in legislatures (Chaney Reference Chaney2012; Dahlerup Reference Dahlerup1988, Reference Dahlerup2007). Although 30% has become the critical mass standard in political science literature, it should not be viewed as a definitive answer to the critical mass question. Childs and Krook (Reference Childs and Krook2006) discuss the idea of “critical masses,” noting that different proportions of women might be able to accomplish different types of changes depending on their context. For the purposes of this paper, I follow the 30% standard set in the existing literature, which allows me to categorize environments into those that meet the critical mass standard and those that do not for the purpose of the quantitative study. When women’s inclusion in political institutions surpasses tokenism, their work plays a role in re-gendering the institution away from masculinized norms; they have the opportunity to work individually and collectively to advance their policy goals. But the link between women’s descriptive and substantive representation is probabilistic, and contingent on the conditions under which they work in their parties and legislatures (Childs Reference Childs2004; Dodson Reference Dodson2006).

Though the link between a greater number of women in the legislature and the representation of women’s interests is probabilistic, the literature shows that women’s descriptive representation does matter for the advancement of women’s interests on the substantive level. For one, women legislators tend to hold more gender-equal attitudes than their men colleagues (Alexander, Bohigues, and Piscopo Reference Alexander, Bohigues and Piscopo2023; Espírito-Santo, Freire, and Serra-Silva Reference Espírito-Santo, Freire and Serra-Silva2020), and they are more likely than their men colleagues to pursue policy initiatives that advance women’s interests (Chaney Reference Chaney2006; Childs and Withey Reference Childs and Withey2004; Osborn and Mendez Reference Osborn and Mendez2010; Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2006). As women increase in numbers in their parties, the policy positions of the party begin to shift toward concerns about the welfare state (related to women’s socialization into caring roles) (Espírito-Santo, Freire, and Serra-Silva Reference Espírito-Santo, Freire and Serra-Silva2020; Kittilson Reference Kittilson2011). Moreover, increasing numbers of women in a party or legislature appears to have some effect on men’s behavior — whether it is an increasing overall focus on women’s issues (Bratton Reference Bratton2005), a respectful stepping back to allow women to represent their own group (Höhmann Reference Höhmann2020), or the development of strategies to represent women in typically “masculine” policy areas (Kroeber Reference Kroeber2023). These findings about the importance of women’s presence, coupled with the probabilistic nature of women’s substantive representation, suggest that restructuring institutions is an important step in enabling the representation of women’s interests. The literature on critical mass underlies the article’s first two hypotheses:

H1: Women senators are more likely to talk about gender and women than their male colleagues overall.

H2: Both men and women senators are more likely to talk about gender and women in contexts that have a critical mass of women (at least 30%).

Parties and the Representation of Women’s Interests

Scholars of women’s substantive representation have conceived of the process as deeply context-dependent (Celis Reference Celis2006; Celis et al. Reference Celis, Childs, Kantola and Krook2014; Celis and Childs Reference Celis and Childs2020; Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009; Tremblay Reference Tremblay2003, Reference Tremblay2006; Trimble Reference Trimble, Sawer, Tremblay and Trimble2006). The critical actors theory of substantive representation suggests that individuals, not institutions, are responsible for the substantive representation of women. This means that for substantive representation to occur, there may or may not be a certain proportion of women legislators present. But, as Childs and Krook (Reference Childs and Krook2006, Reference Childs and Krook2009) argue, the key to women’s substantive representation is not merely a magic number of women in the legislature, but the presence of individuals who are willing to perform critical acts that advance women’s interests. Contexts with a critical mass of women are more likely to produce critical actors, but the efficacy of the critical actor depends on how she interacts with the critical mass (Chaney Reference Chaney2012).

Yet critical actors do not operate in isolation; they must work within their institutional context to pursue their policy goals. Party structures are an institutional factor that can enable and constrain opportunities for legislators to substantively represent women. Once potential critical actors are in office, many are subject to the constraints of party discipline, and it can become very difficult for them to effect change and to act in women’s policy interests (Childs Reference Childs2004; Dahlerup Reference Dahlerup2006; Rayment and McCallion Reference Rayment and McCallion2023; Tremblay Reference Tremblay1998; Young Reference Young, Arscott and Trimble1997). Party discipline has proven to be a particularly constraining factor in Westminster-style parliaments, where the executive must maintain the majority of the votes in the legislature to stay in power. Conversely, in the United States’ congressional system where the executive is separate from the legislature, party discipline is relatively weaker. There, women legislators are known to pursue policy initiatives for women (though partisanship plays a role in limiting the scope of the women’s issue bills introduced, as will be discussed below) (Brown Reference Brown2014; Swers Reference Swers2016). Party discipline is a constraining factor in Westminster-style parliaments, but not in legislatures with low party discipline. Given the low party discipline in the Canadian Senate, which is a chamber within a Westminster-style parliament, I advance the third and fourth hypotheses:

H3: Independent senators will speak more about gender and women than partisan senators do.

H4: Senators will speak more about gender and women following the loosening of party discipline in the 2015 Senate reforms.

The Interaction of Sex and Partisanship in Women’s Representation

In discussing women’s representation by party-affiliated political actors, Erzeel and Celis (Reference Erzeel and Celis2016) stress the importance of differentiating between partisanship and ideology. The authors find that left-right ideology on both economic and post-materialist scales have an effect on parties’ willingness to represent women’s interests. Other studies have also shown that left-wing parties are more likely to advance gender equality and advocate for marginalized groups (Kittilson Reference Kittilson2011; Sevincer et al. Reference Sevincer, Galinsky, Martensen and Oettingen2023; Wagner Reference Wagner2019). Women’s interests have traditionally been viewed as progressive feminist interests, but women legislators can hold diverse ideological standpoints (Tate and Arend Reference Tate and Arend2022). Both feminist and traditionalist claims to represent women’s interests have been made by parties on the ideological left and right (Celis and Erzeel Reference Celis and Erzeel2013; Childs and Webb Reference Childs and Webb2012; Erzeel and Celis Reference Erzeel and Celis2016). However, the framing of women’s issues varies by party and ideology, and qualitative analyses are required to assess the content of these claims (Celis and Childs Reference Celis and Childs2012).

Not only are there partisan differences among women, but there are sex differences within parties too. Right-wing women are ideologically positioned to the left of their men colleagues on issues such as women’s equality and abortion, among others (De Geus and Shorrocks Reference De Geus and Shorrocks2020). Women are also more likely than their men colleagues to frame traditionally “masculine” issues, such as war and defense, as being related to women’s interests (Atkinson, Mousavi, and Windett Reference Atkinson, Mousavi and Windett2023). Given the literature’s findings about the intersection of sex and partisanship, this article’s fifth and sixth hypotheses are as follows:

H5: Progressive and conservative senators will speak about women at similar rates.

H6: Women senators will speak more about gender and women than the men in their parties do.

Constitutive Representation

Siow (Reference Siow2023) disaggregates the concept of representation further. She asks researchers to distinguish between legislators speaking on behalf of women (substantive representation) and just speaking about women (which she calls constitutive representation). Up to now, the literature about parliamentary speech has not often distinguished between substantive and constitutive representation, but Siow’s (Reference Siow2023) argument presents an important turning point for the study of substantive representation. This article places itself in conversation with the existing literature on women’s substantive representation, much of which includes observations about previously undifferentiated constitutive representation. In an effort to turn toward a more accurate disaggregated concept of women’s representation, I use the term constitutive representation to refer to legislators’ discussions about women. Although some of the legislators’ speech may, in fact, express positions on behalf of women, a more granular qualitative analysis is required to confirm that. For that reason, this quantitatively focused paper is mainly concerned with whether legislators are bringing up women when they are engaging in policy discussions.

The Canadian Senate as a Case

Here, I describe the low-partisan environment in the Canadian Senate, illustrating the usefulness of the institution as a case for the study of partisanship, independence, and women’s representation. The Senate is the second chamber in Canada’s bicameral parliament. It is modeled after the United Kingdom’s House of Lords, and it is meant to provide sober second thought for legislation passed by the highly partisan House of Commons. The Senate has the same constitutional powers as the House of Commons; it can introduce, amend, delay, defeat, and pass bills. But in practice, the Senate introduces far fewer bills than the House of Commons, and historically, it has seldom amended or defeated bills (Franks Reference Franks and Serge2003; Godbout Reference Godbout2020; Macfarlane Reference Macfarlane, Goodyear-Grant and Hanniman2019a). This is because senators lack democratic legitimacy, and as a result, the Canadian Senate is often painted as an impotent political institution. Senators are chosen by the prime minister for appointment, and they sit until age 75. They do not seek election, and they do not need to win party approval for endorsements and resources. Thus, party discipline in the Senate is difficult to enforce and is much looser than in the House of Commons, the confidence house.

Reforms to the Senate’s appointment process in the mid-2010s sought to increase the Senate’s legitimacy in the eyes of Canadians by reducing partisanship in the upper house even further. The reforms created a large group of independent senators, who are analogous to crossbenchers in the British House of Lords. On January 29, 2014, Liberal leader Justin Trudeau released all senators from the Liberal party caucus. Although they remained senators, they no longer caucused with the Liberal party, and they were not subject to party discipline (though they still identified ideologically as Liberals and governed their own behavior accordingly) (Macfarlane Reference Macfarlane2019b). Then, after winning government in 2015, Trudeau introduced a new appointment process, meant to replace the previous appointment process whereby the prime minister usually made patronage appointments. The Independent Advisory Board for Senate Appointments (IABSA) now reviews applications to the Senate and forwards recommendations to the prime minister (Stos Reference Stos2017). This shift was meant to improve the legitimacy of senators by removing the element of party patronage from the appointments process and by placing a stronger focus on merit-based appointments.

During the 42nd Parliament (2015–2019), the first parliament following the reforms, there were no senators in the Liberal government caucus, though Conservative senators viewed themselves as the opposition. Without the use of party discipline in the Senate following the reforms, the government had to work hard to secure senators’ votes to support its legislation (Macfarlane Reference Macfarlane2019b). Independent senators did vote overwhelmingly with the Liberal government in recorded votes (Godbout Reference Godbout2020; VandenBeukel, Cochrane, and Godbout Reference VandenBeukel, Cochrane and Godbout2021), which some critics have used to suggest that independent senators are secretly partisan. Yet those statistics also demonstrate that senators are not overstepping their role as appointed legislators by defeating legislation from the elected house. Moreover, independent senators have driven an increase in the scrutiny of government legislation. There was a 4400% surge in amendments from the pre-reform period to the post-reform period, and this increase was driven by independent senators (McCallion Reference McCallion2022). In theory, then, the senators who are not subject to party discipline might be freer to respond to other representational demands (Rayment and McCallion Reference Rayment and McCallion2023). And indeed, independent senators have been disproportionately targeted by lobbyists who recognize that they have no party obligations (Bridgman Reference Bridgman2020).

As the second chamber, the Senate is meant to represent interests not represented by majority rule in the House of Commons. Originally, these were the interests of minority (less populous) regions, who feared that their concerns would be overrun in the House of Commons by the more populous provinces of Ontario and Quebec (Ajzenstat Reference Ajzenstat and Serge2003). But with the falling salience of regional identities, Canadians have become much more concerned with representation based on gender, race, language, religion, and other identities (Anderson and Goodyear-Grant Reference Anderson and Goodyear-Grant2005; Cairns Reference Cairns1993). Now, the Senate is often conceived as a venue for the representation of marginalized group interests (Mullen Reference Mullen, Arscott, Tremblay and Trimble2013; Smith Reference Smith2003), though little empirical research has actually tested that claim. Rayment and McCallion (Reference Rayment and McCallion2023) contend that the low party discipline and absent electoral imperative in the Senate might create a context where senators, who are not bound by other representational demands, can actually represent marginalized groups.

Gender and Committees

Despite the Senate’s often negative reputation, it is known for its strong committee work. Because members of committees study the bills in depth and become familiar with their subject matter, committees can focus on the policy issues at hand, and not on partisan jabs (Docherty Reference Docherty2005; Smith Reference Smith2003). This article looks at committees in the Senate because they are a low-party-discipline environment. Though senators’ ideology may play a role in how they frame women’s interests, the Canadian case offers an opportunity to study legislators’ representation of women when they are virtually (or entirely, in many cases) free from the constraints of political parties.

As discussed in more depth below, this article focuses its attention on four Senate committees that spoke about women the most. Because of the high volume of conversations about women in this dataset, this approach allows for an in-depth analysis of latent content related to women and gender, which can later be applied to a larger sample of data. The committees under study here are the Senate Standing Committees on Human Rights (RIDR); Legal and Constitutional Affairs (LCJC); Social Affairs, Science and Technology (SOCI); and Aboriginal Peoples (APPA — more recently renamed to Indigenous Peoples).

Given the unique environment of committees within the legislature, it is worth exploring the gendered nature of committee interactions. The norms of behavior are different in committees; they are less structured than floor debates in the legislature, yet they are still formal arenas. Importantly, turn-taking with speeches structures dialogue in the institution, and the chair of the committee has power over whose turn it is to speak. In Canadian Senate committees, the members elect the chair from among themselves, and the chair is expected to behave in a nonpartisan manner to ensure fairness. But the sex of the committee chair can have an effect on the committee environment, particularly when it comes to aggressive communications and interruptions (women committee chairs are more likely to acknowledge diverse perspectives and behave as facilitators rather than inserting their personal opinion) (Kathlene Reference Kathlene1994). Of the committees under study, the sex of the chairs was balanced across the data but varied by committee: RIDR had women chairs for the duration of the study, LCJC had men chairs for the duration of the study, and SOCI and APPA both had men chairs in the first half of the time period under study and women chairs in the second half. Leadership style depends in part on personality, and also on institutional context. In professionalized legislatures like the Canadian Senate, both men and women committee chairs do not engage in particularly inclusive styles of leadership; rather, they are governed by the existing rules and norms of their institutions (Rosenthal Reference Rosenthal1997). In the Senate, this means that the course of the dialogue is set by senators rather than allowing for the inclusion of witnesses on equal grounds. There is a clear power dynamic at play: senators ask questions of witnesses, and in that respect, they get to choose the topic and steer the conversation.

Topics Under Study by the Committees

Through both parliaments, the committees focused on various issues related to women’s interests. Notably, government legislation takes precedence in the Senate, so the issues at hand were in large part influenced by the Conservative government of Stephen Harper during the 41st Parliament (2011–2015) and by the Liberal government of Justin Trudeau during the 42nd Parliament (2015–2019). However, the Senate can also initiate its own studies into policy concerns, and these studies are undertaken by Senate committees who hear witnesses and produce reports. Table 1 provides an overview of issues discussed by the committees during each parliament, with key government priorities marked by an asterisk. The list is meant to be illustrative of the committees’ main focuses, and it is not exhaustive.

Table 1. Examples of key issues discussed by committees in the 41st and 42nd Parliaments

* Key government priority

Methods

Measuring Constitutive Representation

I use the frequency with which senators discuss gender and women to indicate their concerns for women’s interests and the differential effects of policies on women. Blaxill and Beelen (Reference Blaxill and Beelen2016) and Rayment (Reference Rayment2024) use a similar approach in studying the substantive representation of women. They (respectively) study speech in parliamentary debates and treat mentions of women as instances of substantive representation. This approach is agnostic about the content of the speeches (i.e., whether the claims made for women are emancipatory or traditionalist) and agnostic about the speaker (i.e., it does not consider women legislators’ speech to be more representative of women in society). Admittedly, this is a high-level approach to studying women’s substantive representation, and to be sure, content and speaker are relevant to the quality of representation. The purpose of this study is to obtain a broad overview of claims-making on behalf of women in the Canadian Senate, opening the door for later qualitative analysis about the content of the claims.

In line with Siow’s (Reference Siow2023) concept of constitutive representation, I embark on a quantitative study of how frequently senators constitute women as a political group by raising women’s concerns in various policy making discussions (see also Celis et al. Reference Celis, Childs, Kantola and Krook2014). Thus, I refer to mentions of women and gender as instances of constitutive representation, whereas previous researchers of parliamentary speech might have referred to them as instances of substantive representation. Constitutive representation may speak about, on behalf of, or against a group (Siow Reference Siow2023), though determining which category the speech falls into requires a finer-grained qualitative analysis. I use mentions of gender and women in Senate committee meetings as an indicator that political actors are talking about women in their policy making discussions.

Time Period under Study

To assess the frequency of speech about women in Senate committee meetings, I completed a multistage analysis to identify and target rich data. I focused on the time periods immediately before and after the Senate reforms: the 41st Parliament (2011–2015) and the 42nd Parliament (2015–2019). Many of the actors remained the same in the Senate before and after the reforms, whereas some were only present for a portion of the time period. Seventy-nine senators served for part or all of both the pre- and post-reform periods, whereas 23 served only in the pre-reform parliament, and 44 served only in the post-reform parliament.

Sampling and Identification of Rich Data

In the first step of the study, I aimed to narrow down the scope of the research by identifying committees that were most likely to talk about women. To unearth latent content relevant to gender, sex, and women, I sought rich data. That is to say, I targeted meetings with a high number of discussions about women. I analyzed a random sample of all committee meeting transcripts from the period under study. Of the 17 committees in the Senate, I found that four committees clearly spoke about women more than others, with two committees mentioning women very often. The Human Rights committee (RIDR) averaged 35 references to women per meeting (over 169 meetings). The Legal and Constitutional Affairs committee (LCJC) averaged 25 references to women per meeting (over 336 meetings). The Social Affairs, Science, and Technology committee (SOCI) averaged 16 references to women per meeting (over 324 meetings). Finally, the Aboriginal Peoples committee (APPA) averaged 15 references to women per meeting (over 289 meetings).

Critical mass theory does not seem to have an effect on the committees’ frequency of discussion about women. There is no correlation between committees that have at least 30% women and those who speak about women the most; RIDR and SOCI had at least 30% women throughout the entire period under study, whereas LCJC and APPA did not. The data here represent policy discussions about women in some women-dominated contexts (mainly RIDR and SOCI meetings) and some men-dominated contexts (mainly LCJC and APPA meetings).

The remainder of this article focuses on the above-mentioned four committees and their discussions during the 41st and 42nd Parliaments. To study whether senators spoke about women when discussing these diverse issues, I collected every meeting transcript from the four committees of interest in the 41st Parliament (2011–2015) and the 42nd Parliament (2015–2019), which comprised the corpus. I coded all the transcripts by speaker and assigned senators attributes according to their parties and sexes.

Developing Codes: Gender and Sex and Women

In this analysis, I examine senators’ mentions of both a Gender and Sex code and a Women code. Gender and sex are conceptually distinct, with sex being assigned at birth (usually based on physical attributes) and gender being a performative expression of one’s own choosing (Bittner and Goodyear-Grant Reference Bittner and Goodyear-Grant2017; Butler Reference Butler1999). But senators (and much of society) often conflate the two in discourse. Rather than coding the literal meaning of senators’ words when they mention sex or gender, I aim to code their intended meaning: are senators intending to talk about gender, sex, or women, even if their terminology is a bit inaccurate? Thus, I have collapsed the concepts of gender and sex into one code — Gender and Sex — to conduct an accurate analysis of senators’ intended meanings.

Though Women is a sub-code of Gender and Sex, it is also conceptually distinct. Discussions under the Gender and Sex code can include senators talking about trans issues, issues that affect men specifically, and gender mainstreaming (known in Canada as Gender Based Analysis +, which is a bureaucratic tool designed to illuminate the gendered and intersectional effects of policies). In brief, the Gender and Sex code covers broad concepts of gender and sex, including specific claims for women. But the Women code captures senators’ speech about women as a constituency; it references a group of people whose interests are politically salient and can be addressed by the policy makers in the room. Studying both codes enriches this analysis by examining both the concept of gender and the constituency of women.

I expect that men senators might be more willing to speak about Gender and Sex than they are about Women. They might be more comfortable expressing opinions about men’s issues, trans issues, and gender mainstreaming than they are with making claims about women as a constituency, which they might feel is better left to their women colleagues (see Höhmann Reference Höhmann2020).

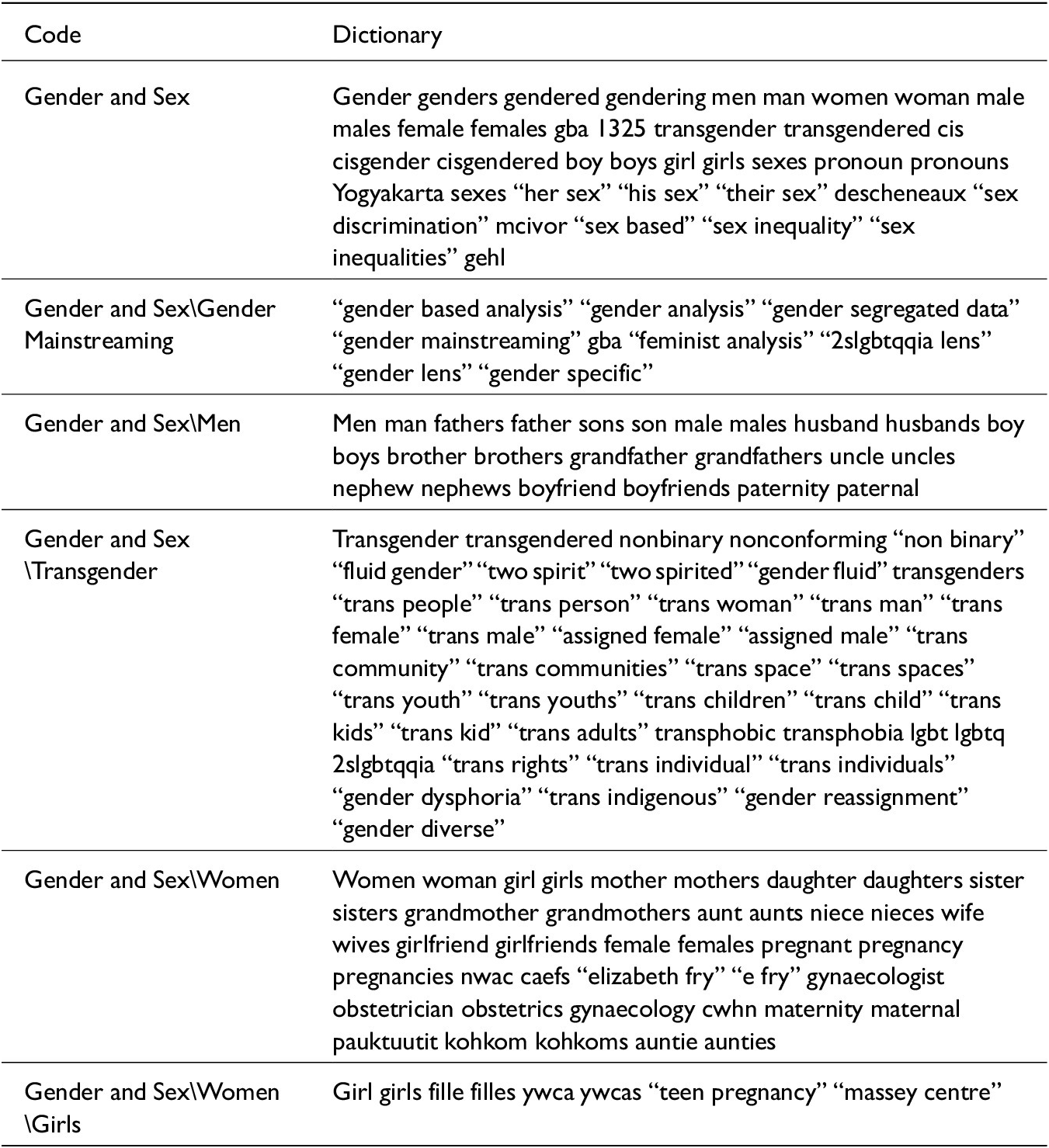

Table 2 lists the words related to women in the top 1,000 words of the corpus, which I used as search terms to identify transcripts of meetings where women were discussed. An in-depth reading of those discussions exposed a number of additional words, not in the top 1,000 words in the corpus, which imply discussions of women or gender. Table 3 presents the dictionaries I built for the Gender and Sex code and its child codes, including the Women code. The Gender and Sex and Women codes aggregate coding from their children (i.e., passages coded to Gender and Sex\Women are also coded to Gender and Sex, and passages coded to Gender and Sex\Women\Girls are also coded to Gender and Sex\Women).

Table 2. Search terms to identify transcripts with the most references to women

Table 3. Dictionaries for gender and sex and its child codes

I then applied the dictionaries I developed to the corpus. The unit of analysis was individual words (or phrases in quotation marks as they appear in the dictionaries). Any word in the transcript that matched one in the coding dictionary was assigned to that code. Studying individual words as a unit of analysis, rather than speeches, allows me to capture the frequency with which senators talk about women across all their speeches, long or short. It also does not require a cutoff to determine what type of speech is long enough to constitute representation, acknowledging that important substantive impacts can be made on a conversation with very short interventions. To study the frequency of speech about gender and women by senators, I matrixed the Gender and Sex and Women codes with individual senators as speakers, who were assigned attributes according to sex and party.

Analyzing Uneven Frequencies of Speech by Senators

I made comparisons using senators’ average references per calendar year to the Gender and Sex or Women codes (for the time that they were appointed to the Senate in the time period of 2011–2019). This accounts for the fact that not all senators attend committee meetings at the same rates, and not all senators were in the upper house for the entire time period under study. It is not just that most of their speeches mention women, which is easy to achieve with just a small number of speeches. Rather, they speak often about women in committees that deal with gender issues. Those senators may be potential critical actors for women’s representation given their interest in talking about gender and women’s issues at the committees that deal with those issues most often.

Senators’ Partisanship, Independence, and Ideology

The Canadian Senate offers a case where party discipline can be separated from partisanship, which is rare in Westminster-style democracies where party discipline is a defining feature. This study analyzes senators by their parties and groups, but given the low (or absent) party discipline, these groupings are really more indicative of ideology. The groups in this study are listed below.

-

• Conservative senators (n=105).Footnote 1 They are considered partisan senators under low party discipline. They ascribe to the center-right-wing ideology of the Conservative Party of Canada (CPC) and sit in the party’s national caucus.

-

• Liberal senators (n=30). They are also partisan senators under low party discipline. They ascribe to the center-left-wing ideology of the Liberal Party of Canada (LPC) and sit in the party’s national caucus. They are only present in the study until they were released from caucus by Trudeau in 2014.

-

• Senate Liberal Caucus (SLC) (n=40). They are partisan senators under low party discipline who ascribe to the center-left-wing ideology of the Liberal Party of Canada. They are the same individuals who sat as Liberal senators, but they are not members of the party’s national caucus. They are only present in the study after they were released from the LPC caucus in 2014.

-

• Independent Senators Group (ISG) (n = 51). They are independent, nonpartisan senators under no party discipline. Though they contain a few conservative-minded members who were appointed pre-reform and joined the Independents, they are overwhelmingly made up of left-leaning legislators appointed by Trudeau following the reforms.Footnote 2

-

• Non-affiliated senators (NA) (n = 6). A small number of senators who do not sit with any party or with the ISG.Footnote 3 They are not characterized by one ideological leaning, but they represent a small group in the study overall.

Results

The results presented here make it clear that senators’ sex is the primary indicator when it comes to their frequency of speech about gender and women. Women senators are much more likely to speak about gender and women than their men colleagues, and these results hold firm against a number of control variables. Of the 998 committee meetings under study, 86% of them mentioned the Gender and Sex code at least once, and 78% of them mentioned the Women code at least once. This shows that women’s issues were regularly considered in the committees under study. The committees have a sustained interest in women and gender, not just a high number of discussions about them related to only one or two studies.

Comparison of Speech across Committees

The discussions of Gender and Sex and Women were not uniform across committees. A one-way analysis of variance showed that there was a significant difference between the frequency with which committees discussed the two codes of interest (p <0.01). The significant difference really lay with one committee; it is clear that RIDR spoke about Gender and Sex and Women significantly more than any other committee (p <0.01). There were no statistically significant differences in how frequently Gender and Sex and Women were mentioned across the other three committees.

Comparison of Individual Senators’ Speech

In terms of individual senators’ inclinations to speak about gender and women, they were not uniform: out of 232 cases, 22% of them did not mention the Gender and Sex code, and 30% of them did not mention the Women code at all during the period under study (in the meetings of the Senate Standing Committees on Aboriginal Peoples, Legal and Constitutional Affairs, Human Rights, or Social Affairs, Science, and Technology).Footnote 4 Clearly, some senators talk about women and gender more than others, particularly women senators.

Sex as a Primary Indicator in the Constitutive Representation of Women

The results show that sex, more than any other factor, structures senators’ willingness to speak about gender and women (p <0.01). This indicates preliminary support for H1, which held that women would speak about gender and women more than their men colleagues. Women senators talk about Gender and Sex 2.5 times as often as their men colleagues do, and they talk about Women three times as often as their men colleagues do. Figure 1 shows that, as expected, men are more likely to talk about Gender and Sex than Women. They talk about Gender and Sex about twice as much as they talk about Women, whereas their women colleagues talk about Gender and Sex about 1.5 times as much as they talk about Women. In other words, compared to their women colleagues, a greater proportion of men’s speech about gender is not specifically related to women’s issues.

Figure 1. Average mentions of gender and sex and women codes per year, by senators’ sex.

Does the correlation between sex and frequency of speech about women hold up under multivariate analyses? And what factors might explain why or under what conditions women senators provide this representation? The next step was multivariate analyses of senators’ mentions of Gender and Sex and Women using individual senators as the unit of analysis (Table 4). This was done in a series of stages, represented by the 3 ordinary least squares (OLS) models reported in Table 4.Footnote 5 Model 1 shows that sex correlates with senators’ tendency to speak about gender. The next step was to introduce individual and contextual factors anticipated to correlate with gender-focused speech among senators (model 2, Table 4).

Table 4. Predictors of senators’ average mentions of gender/sex per year, 2011–2019

Column entries are OLS coefficients with standard errors in parentheses.

* p<0.05 **p<0.01 ***p<0.001

Model 2 shows us that the effect of senators’ sex persists when additional controls are added. Partisanship and independence do not have significant effects on senators’ frequency of speech about gender and women, indicating no support for H3 (that independent senators would speak about gender and women more than partisan senators). And moreover, the reforms do not seem to have had a direct effect on senators’ speech about women; variables indicating pre- and post-reform speech returned no statistically significant results. This means there is no support for H4 (that senators would speak more about gender and women following the loosening of partisanship in the reforms).

Regarding partisanship, there is support for H5 (that senators in the Conservative and Liberal parties will speak about women at similar rates). No significant difference was found in senators’ speech about Gender and Sex and Women across all groups, including the Conservative and Liberal parties, as well as the Senate Liberal Caucus, the Independent Senators Group, and the non-affiliated senators (results not shown). This finding highlights the need for qualitative analysis to assess the content of these constitutive claims for women by legislators across the ideological spectrum (explored further in the discussion below).

As a final step, model 3 presents results with the addition of a variable interacting sex with membership on a critical mass Senate committee, the idea being to assess whether such membership provides a particularly conducive environment for women legislators to represent gender-based interests, as predicted by the critical mass hypothesis. Women senators who sat on at least one committee in which 30% or more of the membership was women were more likely than both men who sat on such committees and women who did not sit on such committees to mention women and gender in their speech acts.Footnote 6 Women who sat on committees with a critical mass made an average of nine more mentions of Gender and Sex (Table 4, model 3) and seven more mentions of Women per year (result not shown). This provides partial support for H2 (that both men and women who sat on committees with a critical mass of women would speak more about women).

Additional interactions were assessed but were found to be statistically insignificant (results not shown). This includes an interaction between sex and the post-reform dummy, which suggests that neither men nor women senators boosted their speech about women following the reforms. Similarly, within-party analyses comparing women and men in the same caucus or group also turned up no significant effect, providing no support for H6 (that women senators will speak more about gender and women than men in their parties do). The finding that sex is the primary factor affecting senators’ willingness to speak about gender and women holds true even when control variables are included, including senator age, tenure, and membership on at least one Senate committee that had a critical mass (30% or greater) of women members.

Identifying Critical Actors

By a per-year average, 68 cases spoke about Gender and Sex more than the mean (n=235, M=9.9, SD=19.65), and 62 cases spoke about Women more than the mean (n=235, M=6.24, SD=14.17). The high variance in the data suggests, again, that some senators speak about gender and women much more than their colleagues. Two senators emerge as outliers who speak about Gender and Sex and Women a great deal more than any others; Senator Kim Pate (Independent Senators Group) spoke about Gender and Sex an average of 171 times per year and Women an average of 136 times per year, and Senator Mobina Jaffer (Liberal Party of Canada) spoke about Gender and Sex an average of 126 times per year and Women an average of 88 times per year. During her time in the Senate Liberal Caucus (after being removed from the national Liberal caucus) and before the Senate reforms, Senator Jaffer spoke about Gender and Sex 143 times per year on average and Women 108 times per year on average. Beyond that, no senator spoke about Gender and Sex more than 60 times per year on average or Women more than 36 times per year on average. Although Jaffer and Pate are standouts for their notable mentions of women, there are a number of potential critical actors who spoke more about women than their colleagues, and their legislative behavior is worthy of more in-depth, qualitative analysis to identify critical actors in future research.

Discussion

Sex as a Primary Indicator

The results of this analysis show that senators’ sex is a primary indicator that affects whether they talk about gender and women in the committees under study. This provides support for H1 (that women senators talk about gender and women more than men). Moreover, it is consistent with decades of research showing that although men can represent women’s interests, women legislators are much more likely to bring women’s issues to the agenda (Bratton Reference Bratton2005; Lovenduski and Norris Reference Lovenduski and Norris2003; Orey et al. Reference Orey, Smooth, Adams and Harris-Clark2007; Tremblay Reference Tremblay1998; Trimble Reference Trimble, Sawer, Tremblay and Trimble2006). The data show that most men senators do talk about gender and women, and at the same time, not all women senators talk about gender and women. But in general, women senators have done much more than their male colleagues to bring the concerns of women to the table.

Moreover, women senators are more likely to talk about women’s issues when they sit on committees with a critical mass of women. There is likely some interplay between the critical mass of women on a committee and the presence of critical actors, though other factors might affect the emergence of critical actors (see Chaney Reference Chaney2012). It may be that women senators are seeking positions on committees with critical mass, or certain policy discussions may lend themselves to a critical mass of women and the discussion of women’s interests. It seems that the topic of policy discussion might have an effect on the emergence of critical actors, given that a critical mass of women does not predict more discussions about women by the committee, but women within a critical mass context do speak about women more. These findings highlight, once again, the importance of women’s presence in the legislature. They add to the myriad of data showing that women legislators are key forces in the substantive representation of women.

Partisanship and Its (Lack of) Effects

Whereas the first two hypotheses revolved around the question of critical mass, the remaining hypotheses were related to the environments in which senators act — in particular, parties. The Canadian literature about parties and the substantive representation of women has found that party discipline can stunt feminist initiatives (Rayment Reference Rayment2024; Tremblay Reference Tremblay1998; Young Reference Young, Arscott and Trimble1997). And the global literature shows that party structure affects the type of substantive representation legislators can perform for women (Alexander, Bohigues, and Piscopo Reference Alexander, Bohigues and Piscopo2023; Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009; Espírito-Santo, Freire, and Serra-Silva Reference Espírito-Santo, Freire and Serra-Silva2020). The case of the Canadian Senate allows for the disaggregation of party discipline and partisanship. Absent party discipline, the results of this study show that partisanship and independence had little effect on senators’ participation in committees when it comes to their frequency of speech about women and gender.

Leaving aside party discipline and focusing on ideology, progressive and conservative senators do not differ significantly in their frequency of discussions about women. This supports H5 (progressive and conservative senators will talk about women at similar rates). Evidently, discussions about women are not exclusive to progressive politicians. Research on women’s substantive representation has endeavored to define “women’s interests” beyond just feminist emancipatory interests to include the interests of women who are not feminist, and those whose interests are more traditionalist (Celis and Childs Reference Celis and Childs2012; Celis and Erzeel Reference Celis and Erzeel2013; Gordon Reference Gordon2021; Rayment Reference Rayment2024). The results of this study demonstrate that conservative senators talk about women as much as progressive senators do.

Sex, Partisanship, and Constituting Women: Qualitative Considerations

A qualitative study of senators’ speech about women can unearth how ideology leads senators to differ in their claims to represent women’s interests. Although senators’ sex is the primary indicator of their frequency of speech about women, senators’ partisanship and ideologies drive differences in their framing of women.

Overwhelmingly, senators talk about women as vulnerable people. I observe that Conservative senators more often discussed women’s vulnerability while connecting it to protection from the state (e.g., advocating for prosecution of individual criminals to keep women safe). Senators’ discussions about the restriction of sex work provide a clear example of this framing. Senator Jean-Guy Dagenais (Conservative, Quebec) said in response to a witness’ testimony,

I was a bit surprised by your presentation, when you said that you find Conservatives to be moralists…. I do not think that wanting to provide some security to the most vulnerable members of our society is moralizing; instead, I think it has to do with wanting to provide them with some security, even if just a little. I am talking about the most vulnerable people and about victims of prostitution, including minors. (Canada 2014a)

Progressive senators more often framed women as vulnerable people who were victims of the state (e.g., highlighting biases in the criminal justice system that lead certain demographics of women to become criminalized). An example of this framing, also in the context of sex work, comes from Senator George Baker (Senate Liberal, Newfoundland), who asked a witness, “Do you see anything in the bill that would change the attitude of the police toward prostitution that may result in many more convictions of the prostitutes themselves?” (Canada 2014b). Here, he is trying to challenge the witness (a police officer) with the supposition that restricting sex work will ultimately harm sex workers by giving them criminal records. Neither of these frames were exclusive to either group of senators, but progressives and conservatives had tendencies toward how they framed the state in women’s lives.

Moreover, whereas most senators focused on issues related to women and the justice system, right-wing women senators most often constituted women as mothers. Right-wing men and left-wing senators did discuss women in relation to their families very often, but it was a framing most commonly deployed by right-wing women. Most of these speeches indicate concerns for progressive feminist interests (though they are somewhat infused with neoliberal concerns about the economy and the workforce). For example, in a meeting about the national maternity assistance program, Senator Rose-May Poirier (Conservative, New Brunswick) said, “I assume that, once the baby is born, the mothers are entitled to maternity benefits under the employment insurance program. If the employee is gone for a year to a year and a half, is their job guaranteed when they come back?” (Canada 2018d). Poirier is expressing concern that parental leave might damage women’s job security and limit their ability to contribute to and benefit from the Canadian economy, and she wants to ensure that mothers on leave will not lose their employment. In the transcripts under study here, the mention of women as mothers was often infused into other policy discussions, but usually by briefly mentioning that someone affected by policy was a mother. Senators’ mentions of mothers in the committee meetings under study here do not indicate a reinscribing of maternalism into state policy (Jenson Reference Jenson2015); rather, it is consistent with research showing that Canadian social policy discourse is focused not on women but on “families,” and women are constituted as economic producers (Dobrowolsky Reference Dobrowolsky, Dobrowolsky and Mackay2020; Wallace and Goodyear-Grant Reference Wallace and Goodyear-Grant2020).

Although senators other than right-wing women mainly emphasized the justice system, left-leaning women senators often mentioned race, ethnicity, and culture in conjunction with women. Whereas men senators and right-wing women also discussed race, left-wing women were more likely to deploy this framing. In this data, they most often discussed the intersection of gender and Indigeneity; however, they usually used dominant groups as comparators. They tended to talk about the mistreatment of Indigenous women compared to white women or compared to Indigenous men, usually emphasizing one aspect as a primary identity. More infrequently, there were instances where senators talk about Indigenous and racialized minority women in a way that does not place their gender or their race as their primary identity, which some would argue is closer to a true intersectional understanding of identity (for example, see Hancock Reference Hancock2007; Hankivsky and Mussell Reference Hankivsky and Mussell2018). An example comes from a discussion that focused on whether criminal courts should consider it an aggravating factor for sentencing in murder cases if the victim is an Indigenous woman. Senator Frances Lankin (Independent Senators Group, Ontario) said, “Given the overall lack of equality and the profound discrimination in the criminal justice system writ large with respect to impacts on Indigenous girls and women … we will not tolerate and we will not give any leniency where the person murdered is an Indigenous girl or woman” (Canada 2019). As illustrated by this quote, the policy discussion did not highlight Indigenous women’s race or gender as the primary factor for their vulnerability but acknowledged that Indigenous women are uniquely vulnerable to becoming victims of criminals. Left-wing women’s emphasis on racialized and Indigenous women is consistent with findings in the literature, discussed above, that left-wing legislators and women legislators are more likely to bring the concerns of marginalized groups to the table.

Qualitative illustrations of this data demonstrate that although women talk more about Gender and Sex and Women than their male colleagues, they do not all frame women’s concerns and interests in the same way. The qualitative descriptions of the data here support the findings of previous researchers that legislators’ claims to represent women, and indeed, women’s interests, can be heterogenous, diverse, and even in conflict with one another.

No Changes through the Reforms?

The results of this study show that there was no difference in the frequency of discussions about gender and women between the pre-reform and post-reform period, meaning that H4 is not supported. This is despite the fact that the Conservative government under Stephen Harper and the Liberal government under Justin Trudeau had different legislative priorities, with Trudeau declaring his government Canada’s first feminist one. Though the policy focus of the government changed over the period of study, senators’ inclination to talk about gender and women remained constant. This points to important considerations about the unique circumstances of legislators operating in a house with no party discipline. In essence, partisan legislators in the pre-reform Senate were just as likely to discuss women’s interests as independent legislators. Given the established findings that party discipline tends to mediate women’s substantive representation, this new finding raises questions about the value of policy making contexts with low party discipline.

Although the reforms did not cause any direct change to individual senators’ mentions of women, the full effect of the reforms is yet to be seen. This article’s finding about sex as a primary indicator of the constitutive representation of women magnifies an important effect of the Senate reforms: there was a sharp increase in the number of women senators. The IABSA is mandated to consider sex parity in the Senate when they make candidate recommendations. The new appointment process has brought the Senate from around one-third women in the pre-reform period to approximate sex parity by 2021 (McCallion Reference McCallion2021). The Senate reforms have contributed to the increased descriptive representation of women, and in doing so, they offer the promise of improved constitutive and substantive representation. The reforms ensure that women senators will be appointed, and women senators are more likely to discuss gender and women’s issues in the Senate’s key policy making venues (committees).

Conclusion

Two key findings from this article support the critical mass and critical actors theories of representation, respectively. First, this article confirms that legislators’ sex remains a primary indicator of whether they will take an interest in gender issues and women’s issues, supporting the argument for women’s descriptive representation. Women senators are more likely to talk about gender and women, and they are even more likely to do so in environments where there is a critical mass of women. Second, and related to critical actors theory, the article finds that women senators talk about women and gender at different rates, and the way they constitute women varies with their ideology and partisanship. The study found outliers in women senators who mention women very frequently. Notably, one of the outliers (Senator Jaffer) was the chair of RIDR, suggesting that her leadership may have been a factor in the high number of discussions about gender and women at RIDR. The priorities of committee chairs are an area for further investigation in the study of women’s substantive representation. And there are other senators (mainly women) who do talk about gender and women more often than their average colleagues. Moving forward, future research can do more to connect these senators’ words to their legislative behavior to understand whether their institutional context enables them to act on their words.

The article offers an important distinction between party discipline and partisanship when it comes to women’s representation. Although previous research shows that parties mediate women’s substantive representation, these findings suggest that partisanship does not limit the quantity of women’s substantive representation where party discipline is low. In other words, it is party discipline, and not partisanship or ideology, that has had constraining effects on the substantive representation of women. This has implications for Westminster-style parliaments. Party discipline tends to be low in contexts where the stakes of government are low — in effect, where the actions taken have little chance of disrupting the status quo or threatening the government’s power. What does it say about Westminster systems when women’s constitutive (and substantive) representation is best performed in the low-stakes sphere? More research on the prime venues for women’s representation can help identify and correct instances where women’s interests may have been hindered by institutional context.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Elizabeth Goodyear-Grant for her guidance and help, as well as Keith Brownsey and the audience at the CPSA’s 2023 annual conference in Toronto for their insightful comments. She also wishes to thank the editor and three anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback that has benefited this article greatly.

Competing interest

No conflict of interest is declared.