Nutrition is a major determinant of physical, cognitive and socio-economic development during adolescence(Reference Black, Victora and Walker1,Reference Patton, Sawyer and Santelli2) . In low- and middle-income countries, a nutrition transition is ongoing. With economic development, populations are slowly shifting from traditional diets to ‘Western’ diets, rich in high-energy foods and are more likely to adopt sedentary lifestyles. This is leading to a double burden of malnutrition, with under-nutrition persisting as a major public health problem, and with concomitantly a rise in the prevalence of overweight and obesity, accompanied by a higher risk of non-communicable diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular disorders(Reference Muthuri, Francis and Wachira3). The West African region is currently at the early stages of this nutrition transition. This manifests as a rapid increase in urbanisation (projection to 62 % in 2050 v. 42 % in 2010) associated with changes in diet quality and quantity, but with for now small moderate increases in average daily energy intake (from 2002 to 2699 kcal between 1985 and 2013) compared with other regions(Reference Bosu4).

With a population of 22 million, one-fifth living in the district of Abidjan, the economic capital, Côte d’Ivoire is a growing developing country. In 2014, 42 % of its population was aged <15 years(Reference Lassi, Moin, Bhutta, Bundy, Silva de and Horton5). Among children under 5 years of age, the prevalence of wasting and stunting was, respectively, 21·6 and 6·1 % in 2018, and 1·5 % were overweight(6). It is estimated that 15 % of the population is living in moderate food insecurity, at a stressed level, where households have minimally adequate food consumption(7). Micronutrient deficiencies such as Fe deficiency are also highly prevalent in Côte d’Ivoire, resulting from insufficient micronutrient intake and sometimes also from infections such as hookworm infestation, schistosomiasis or malaria(Reference Camaschella8). In 2016, 16 % of children aged 6–59 months and 66 % women aged 15–48 years had anaemia in Côte d’Ivoire, with higher rates in regions with lower economic development(9). Research into adolescent health in Côte d’Ivoire is relatively under-developed, focusing mainly on sexual and reproductive health and HIV/AIDS(10–Reference Dahourou, Masson and Aka-Dago-Akribi12). Adolescent nutrition is not currently a priority for the National Multisectoral Nutrition Plan 2016–2020, except for adolescent girls of childbearing age, who represent a target population for the reduction of undernutrition, anaemia and Fe deficiency. The aim of targeting this population is mainly to break the inter-generational cycle of malnutrition(13).

Adolescent nutritional care remains a neglected topic worldwide, whereas this is a crucial period of development, with high energetic energy and nutrient requirements. Poor nutrition and multiple micronutrient deficiencies can hinder their physical, cognitive and psychosocial development(14). Worldwide, between 10 and 14 years of age, Fe deficiency anaemia is responsible for 1161 and 1365 disability-adjusted life years lost per 100 000 female and male adolescent, respectively(15). Other key micronutrients such as Zn, Ca and vitamin D play a role in the adolescent development, promoting adequate growth, ensuring lifelong bone health while also enhancing immunity and sexual maturation(Reference Akseer, Al-Gashm and Mehta16). While transitioning to adulthood, adolescents may experience lifestyle and eating behaviour change that may increase the risk of food disorders and overweight and obesity(Reference Das, Salam and Thornburg17), but important research gaps persist and factors influencing this nutrition transition in adolescents are insufficiently addressed(Reference Stok, Renner and Clarys18).

The TALENT (Transforming Adolescent Lives through Nutrition) collaboration aims to conduct qualitative and quantitative nutritional research among adolescents in five low-and middle-income countries (India, The Gambia, Ethiopia, South Africa and Cote D’Ivoire) and to develop interventions to improve adolescent nutrition. This literature review sought to describe what is known from recent research about the nutritional status of adolescents in Cote D’Ivoire and identify knowledge gaps in order to plan the most relevant future research.

Methods

Search strategy

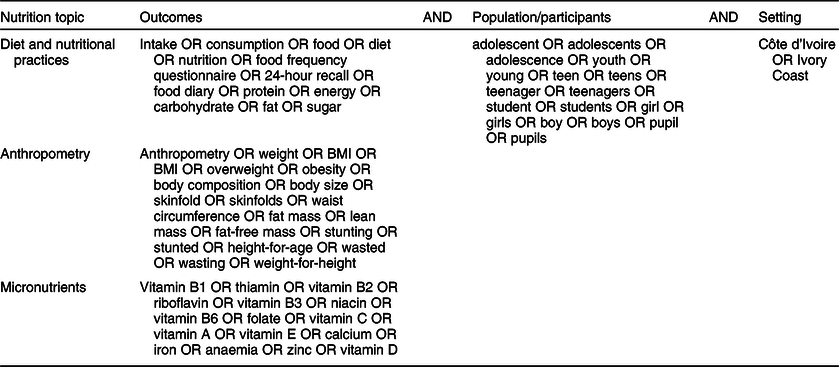

This review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement (Supplement 1). As part of a multiregional initiative, the keywords of interest were defined by a working group within the TALENT collaboration (Table 1). Three aspects of nutrition were covered: diet and nutritional practices, anthropometry and micronutrients. The study population (adolescents) was defined using another group of keywords which was added to each search strategy, as well as the country setting (Côte d’Ivoire or Ivory Coast), combining each group using ‘AND’. We implemented this search strategy in the PubMed database and also looked for grey literature, searching relevant studies from libraries in Abidjan and in other web-based sources such as Google Scholar.

Table 1 Keywords used for the search strategy to identify nutritional studies conducted among adolescents aged 10–19 years in Côte d’Ivoire between 2000 and 2019

Inclusion criteria were as follows: all quantitative studies conducted in Côte d’Ivoire, among girls and boys aged between 10 and 19 years, published in English or French from the 1 January 2000 to the 1 May 2019. Any quantitative study design was accepted (observational, analytical, interventions, clinical trials); qualitative studies were not included, as these were the subject of a separate review (see Hardy-Johnson et al., this issue).

Literature selection, data extraction and synthesis

This narrative review was conducted in an exploratory way, without excluding papers due to poor quality in terms of methodology, sample size or results. We only excluded studies which did not allow us extracting specific data for adolescents aged 10–19 years. Two independent reviewers (J.J. and K.K.) conducted the search and discussed discrepancies before agreeing on the final papers to be included. Each of the three search strategies (diet and nutritional practices, anthropometry and micronutrients) was carried out in PubMed, and duplicates were removed. Potentially relevant titles and abstracts were then screened; the full text articles were obtained and reviewed to finalise the selection. Main reasons for exclusion of articles were documented. The reference lists of included articles were manually searched for potential additional articles.

Data extraction was done using a standardised form that collected the following from each article: the first author and year of publication, main study objectives, study design and study period, sample size (specifically for the study population aged between 10 and 19 years if provided, as well as for Côte d’Ivoire only in the case of multiregional studies), setting (rural/urban), age range, percentage of girls, main results and a final column reporting limitations and remarks of the person in charge of the data extraction (J.J.). Articles were ordered in the data extraction table by topic and then by year of publication. A narrative summary was presented for each selected study and a thematic synthesis described consecutively descriptive, analytical and interventional results related to nutritional status.

Results

Literature search and study characteristics

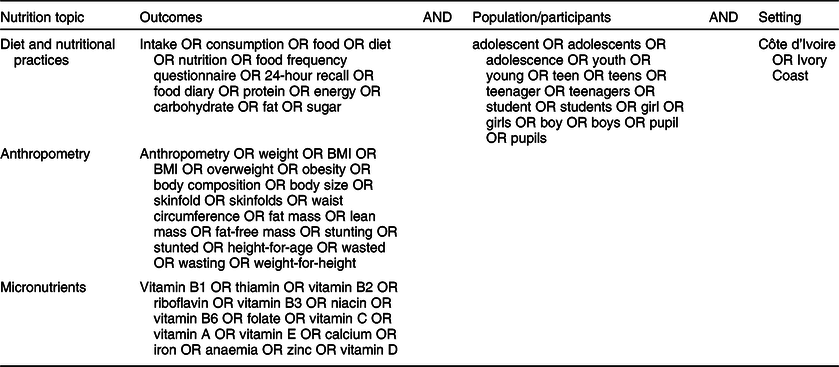

The three search strategies identified 285 potentially relevant articles regarding the topic of diet and nutritional practices, 108 on anthropometry and eighty four on micronutrients (Fig. 1). After deleting duplicates, 384 articles were obtained; screening their titles and abstracts resulted in forty four full-text articles to review. The main reason for exclusion on title and abstract screening was that the topic of the study was unrelated to nutrition or showed no applicable data. After carefully reading the remaining articles, twenty five were selected. The main reason of exclusion at this step was that the article did not describe relevant data on adolescents. Additionally, five studies from the grey literature search(Reference Muthuri, Francis and Wachira3) and Google Scholar(Reference Patton, Sawyer and Santelli2) were included. No additional articles were obtained from screening the references of the selected articles. Finally, thirty articles were analysed for this review.

Fig. 1 Flow-chart of the literature selection process to identify nutritional studies conducted among adolescents aged 10–19 years in Côte d’Ivoire between 2000 and 2019, TALENT collaboration

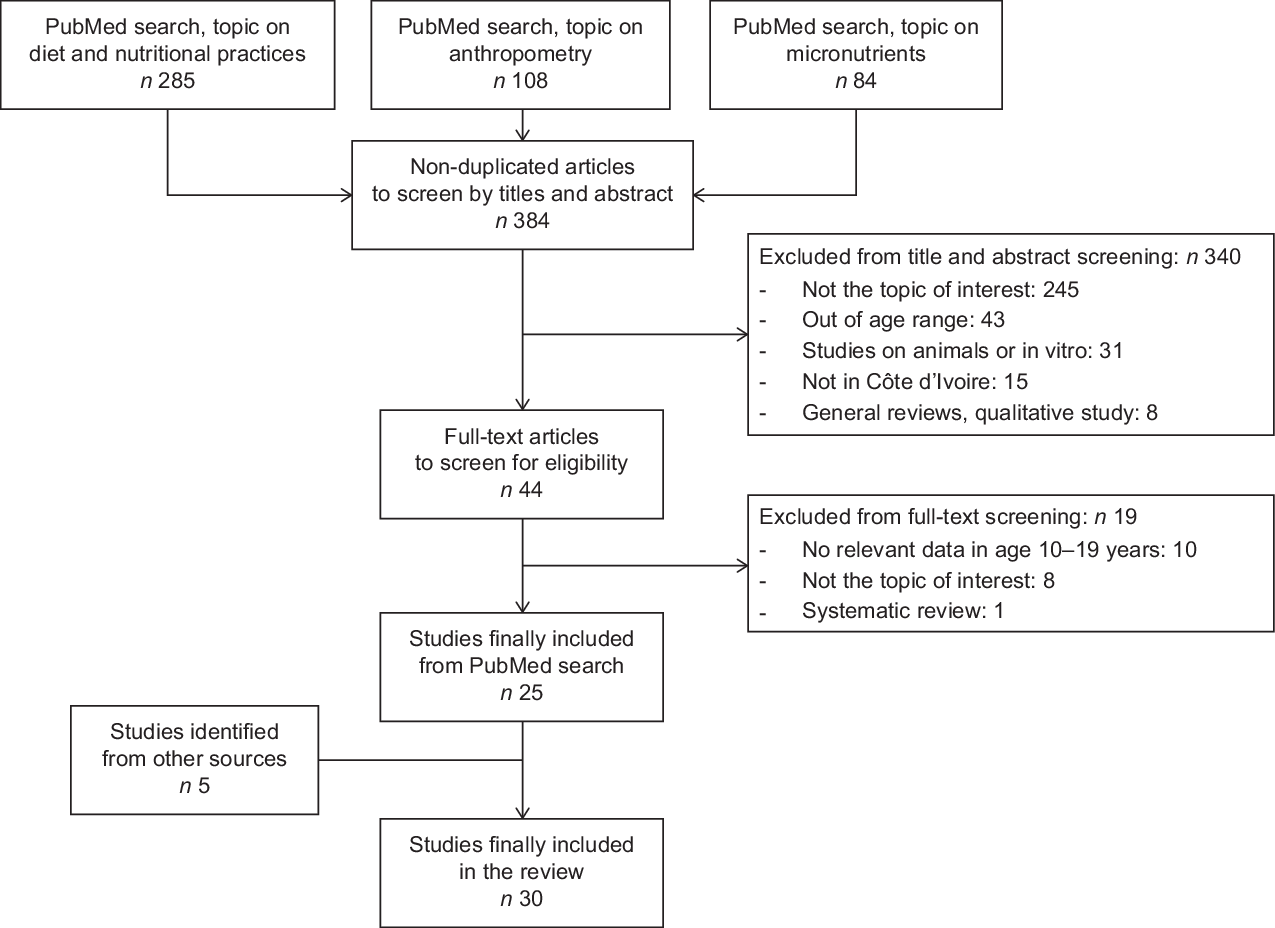

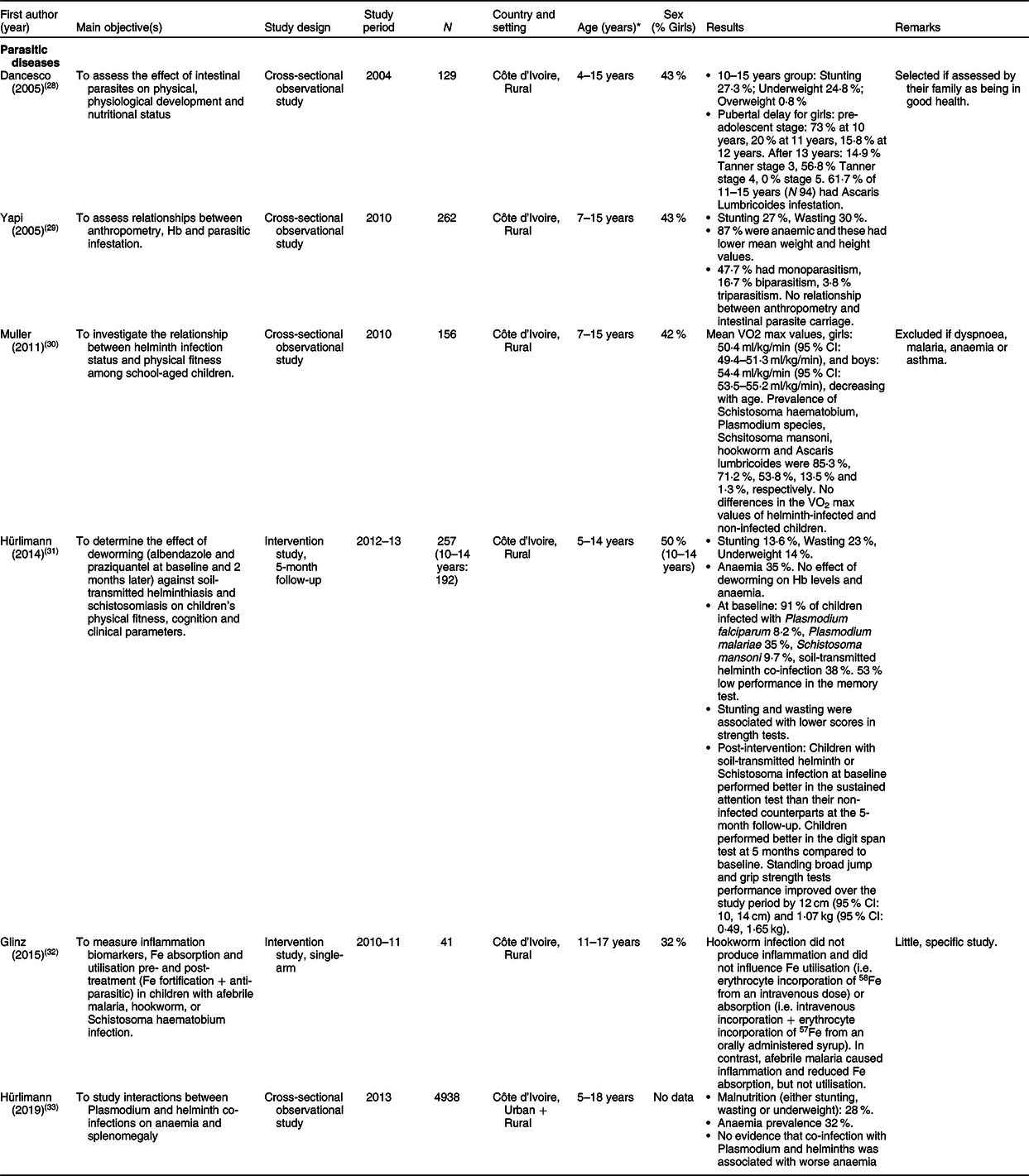

Among the thirty articles selected(Reference Asobayire, Adou and Davidsson19–Reference Tiehi48), twenty were cross-sectional observational studies(Reference Asobayire, Adou and Davidsson19–Reference Yapi, Ahiboh and Yayo22,Reference Righetti, Koua and Adiossan25,Reference Dancesco, Akakpo and Iamandi28–Reference Müller, Coulibaly and Fürst30,Reference Hürlimann, Houngbedji and Yapi33,Reference Peltzer and Pengpid38–Reference Tiehi48) , seven were intervention studies(Reference Rohner, Zimmermann and Amon23,Reference Zimmermann, Chassard and Rohner24,Reference Hürlimann, Houngbedji and N’Dri31,Reference Glinz, Hurrell and Righetti32,Reference Hess, Zimmermann and Adou34,Reference Zimmermann35,Reference Wegmüller, Camara and Zimmermann37) with three of them being randomised controlled trials(Reference Rohner, Zimmermann and Amon23,Reference Zimmermann, Chassard and Rohner24,Reference Hess, Zimmermann and Adou34) and three were longitudinal observational studies(Reference Bleyere, Amonkan and Kone26,Reference Righetti, Adiossan and Ouattara27,Reference Zimmermann, Hess and Adou36) . A third were conducted before 2010 and another third after 2013. Thirteen were conducted partially or exclusively in the city of Abidjan and fifteen exclusively in rural regions of Côte d’Ivoire, while three studies took place in multiple countries(Reference Zimmermann, Molinari and Staubli-Asobayire20,Reference Peltzer and Pengpid38,Reference Jesson, Masson and Adonon44) . Overall, 12 279 children and adolescents were included, more than half of them being involved in studies assessing anaemia and/or parasitic diseases. The age range was wider than the 10–19-year interval for twenty six of the studies, most of them enrolling younger children, and disaggregated data by age group were not always provided for every outcome. Gender-stratified data were also lacking in seven studies(Reference Asobayire, Adou and Davidsson19,Reference Yapi, Ahiboh and Yayo22,Reference Hürlimann, Houngbedji and Yapi33,Reference Zimmermann35,Reference Wegmüller, Camara and Zimmermann37,Reference Houphouët, Yapo and Dodehe43,Reference Beda46) . Three studies were conducted exclusively among girls; one among pregnant adolescent girls(Reference Bleyere, Amonkan and Kone26) and the other two among young non-pregnant women aged 15–25 years(Reference Righetti, Koua and Adiossan25,Reference Righetti, Adiossan and Ouattara27) . For the remaining studies, the percentage of girls included ranged from 30 to 62 %. The main topics of interest addressed in these articles were anaemia and Fe deficiency in nine studies(Reference Asobayire, Adou and Davidsson19–Reference Righetti, Adiossan and Ouattara27) (Table 2), parasitosis in six studies(Reference Bleyere, Amonkan and Kone26–Reference Hürlimann, Houngbedji and Yapi33) (Table 3) and iodisation and salt fortification in four studies(Reference Hess, Zimmermann and Adou34–Reference Wegmüller, Camara and Zimmermann37) (Table 4). Three studies focused on food intake and nutritional practices(Reference Peltzer and Pengpid38–Reference Gbogouri, Dakia and Traore40), two on diabetes and overweight and obesity(Reference Agbre-Yace, Oyenusi and Oduwole41,Reference Kramoh, N’goran and Aké-Traboulsi42) (Table 5) and the last six studies were on different topics including the impact of nutritional status on immunity and inflammation(Reference Houphouët, Yapo and Dodehe43), prevalence of malnutrition in children and adolescents living with HIV(Reference Jesson, Masson and Adonon44), associations between nutritional status and school performance(Reference Zahe, Méité and Ouattara45) and living conditions, associations between body image/perception and eating behaviours and the association between sleep duration and nutritional status(Reference Beda46–Reference Tiehi48) (Table 6).

Table 2 Summary table of studies included in the present scoping review related to anaemia and iron deficiency in adolescents living in Côte d’Ivoire

EAR, estimated average requirements; IDA, Fe deficiency anaemia; IPT, intermittent preventive treatment; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

* Unless age sub-groups are specified, results are given for the whole age group.

Table 3 Summary table of studies included in the present scoping review related to parasitic diseases and nutrition in adolescents living in Côte d’Ivoire

* Unless age sub-groups are specified, results are given for the whole-age group.

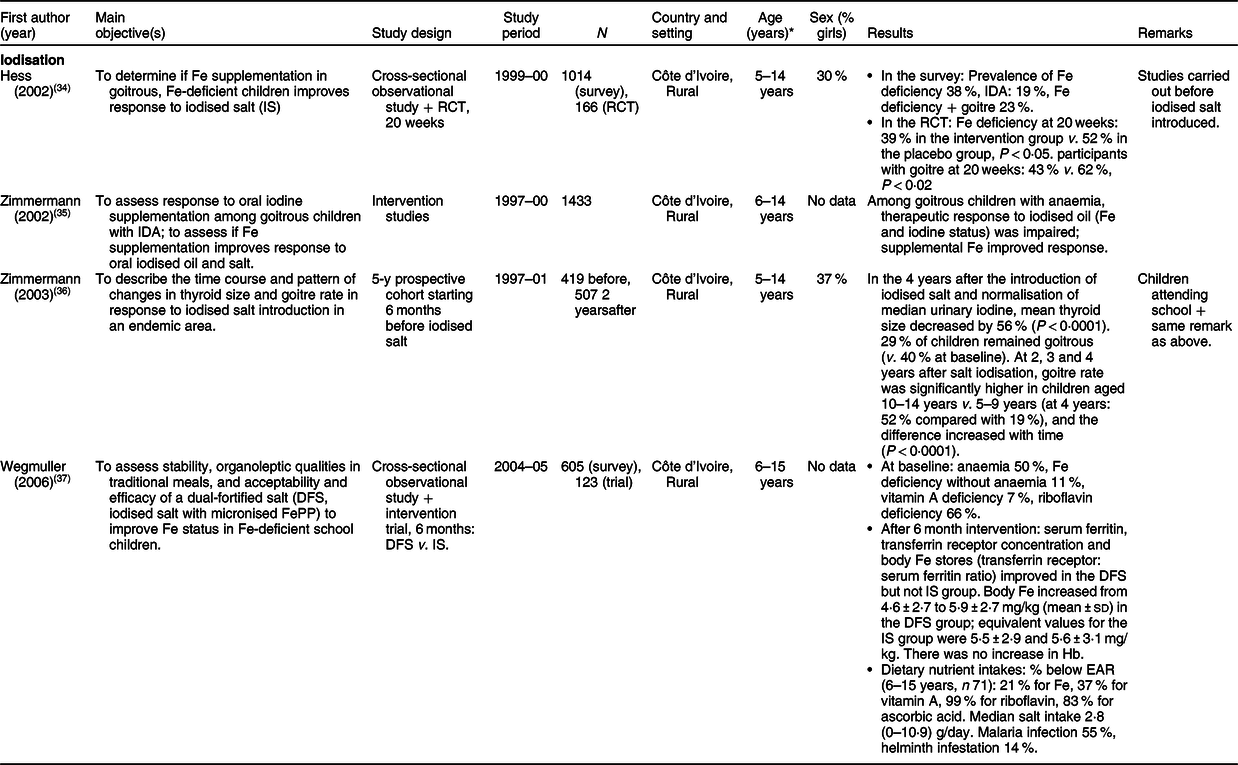

Table 4 Summary table of studies included in the present scoping review related to iodisation and salt fortification in adolescents living in Côte d’Ivoire

DFS, dual-fortified salt; EAR, estimated average requirements; IDA, Fe deficiency anaemia; IS, iodised salt; RCT, randomised control trial; suppl, supplementation.

* Unless age sub-groups are specified, results are given for the whole age group.

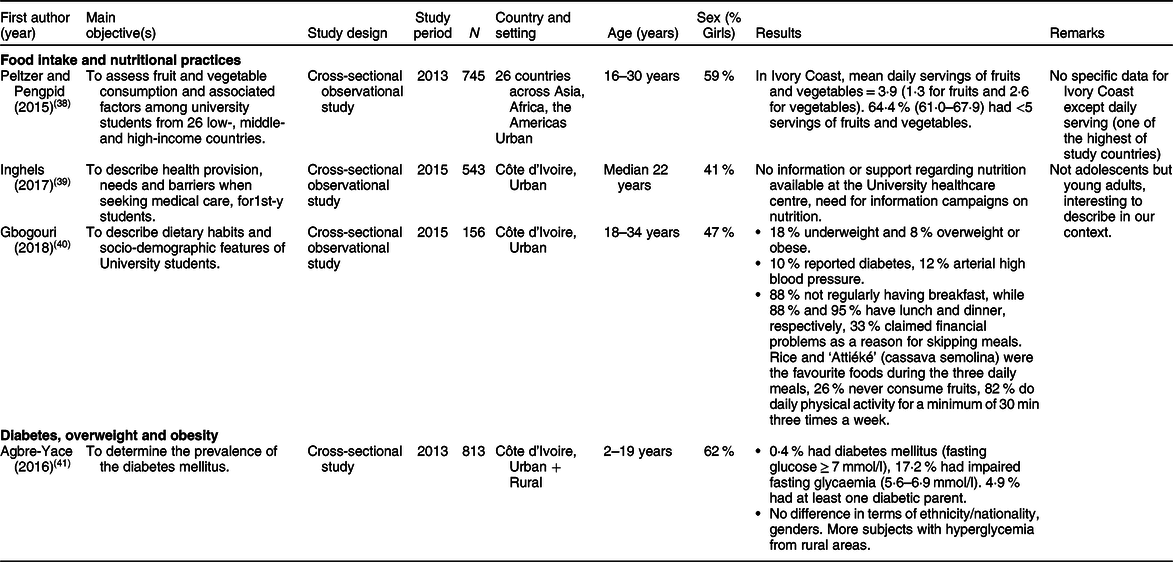

Table 5 Summary table of studies included in the present scoping review related to food intake and nutritional practices, diabetes, overweight and obesity in adolescents living in Côte d’Ivoire

* Unless age sub-groups are specified, results are given for the whole age group.

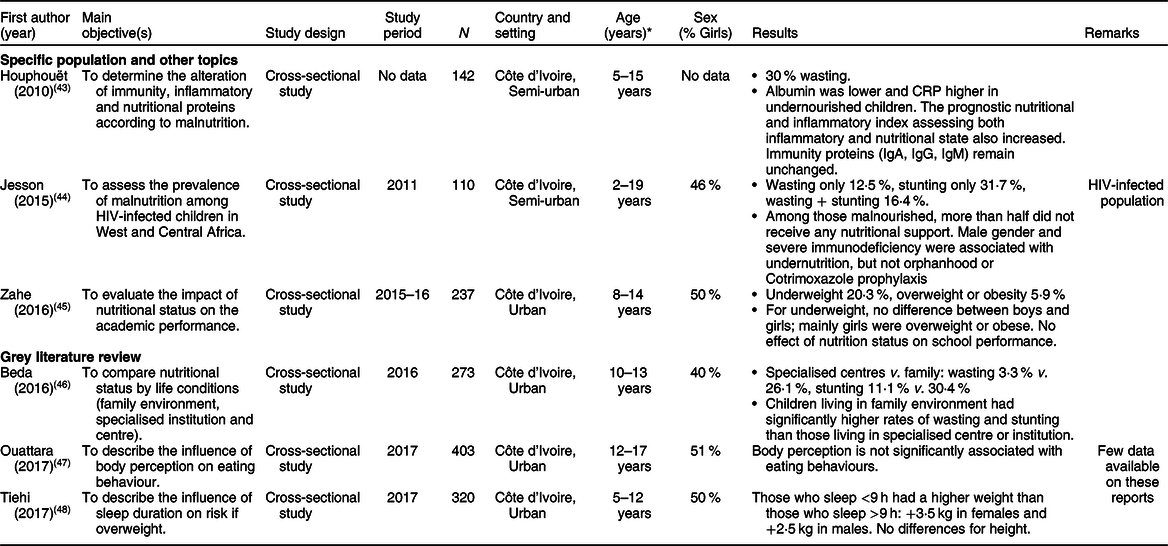

Table 6 Summary table of studies included in the present scoping review related to nutrition in adolescents living in Côte d’Ivoire, covering specific populations, topics and grey literature

CRP, C-reactive protein.

* Unless age sub-groups are specified, results are given for the whole age group.

Description of adolescent nutritional status

Prevalence of malnutrition

Anthropometric data were provided in eleven studies(Reference Rohner, Zimmermann and Wegmueller21,Reference Dancesco, Akakpo and Iamandi28,Reference Yapi, Ahiboh and Monnet29,Reference Hürlimann, Houngbedji and N’Dri31,Reference Hürlimann, Houngbedji and Yapi33,Reference Gbogouri, Dakia and Traore40,Reference Kramoh, N’goran and Aké-Traboulsi42–Reference Beda46) . The prevalence of stunting ranged between 8(Reference Rohner, Zimmermann and Wegmueller21) and 27 %(Reference Dancesco, Akakpo and Iamandi28), with variations both in rural and urban settings. Among adolescents living with HIV, the prevalence of stunting was higher at 27 %(Reference Jesson, Masson and Adonon44). The prevalence of underweight ranged from 11(Reference Rohner, Zimmermann and Wegmueller21) to 25 %(Reference Dancesco, Akakpo and Iamandi28) and wasting from 23 to 30 %, except for one study in Abidjan, where 65 % of children and adolescents attending school were thin or extremely thin(Reference Kramoh, N’goran and Aké-Traboulsi42). Four studies measured overweight and obesity (0·8 % overweight(Reference Dancesco, Akakpo and Iamandi28), 8 % overweight or obese(Reference Gbogouri, Dakia and Traore40), 4 % overweight and 5 % obese(Reference Kramoh, N’goran and Aké-Traboulsi42), 5·9 % overweight or obese(Reference Zahe, Méité and Ouattara45)). The prevalence of malnutrition varied greatly between studies, with no clear differences between rural and urban settings.

Micronutrients

Fourteen studies provided data on anaemia and Fe deficiency, defined using the international red cell parameter cut-offs from WHO (Table 1). Rates of anaemia were very high, from 32(Reference Hürlimann, Houngbedji and Yapi33) to 87 %(Reference Yapi, Ahiboh and Monnet29). Fe deficiency with anaemia was also very common ranging from 9·3(Reference Rohner, Zimmermann and Amon23) to 43 %(Reference Yapi, Ahiboh and Yayo22), and Fe deficiency without anaemia from 11(Reference Wegmüller, Camara and Zimmermann37) to 59 %(Reference Rohner, Zimmermann and Wegmueller21). Fe intakes were measured in three studies using 3-day weighed food records, and 21 % of participants had intakes below estimated average requirements (EAR)(Reference Rohner, Zimmermann and Wegmueller21,Reference Wegmüller, Camara and Zimmermann37) . Although absolute intakes of Fe in boys and girls were similar, 94 % of boys but only 44 % of girls reached the EAR(Reference Zimmermann, Chassard and Rohner24).

Three studies assessed the status and/or intake of other micronutrients. The prevalence of vitamin A deficiency was 1 % [21] and 7 % [37] in two studies. Two-thirds of participants were estimated to be riboflavin (B2) deficient in three studies(Reference Rohner, Zimmermann and Wegmueller21,Reference Righetti, Koua and Adiossan25,Reference Wegmüller, Camara and Zimmermann37) . In the study from Rohner et al. 2007(Reference Rohner, Zimmermann and Wegmueller21), median riboflavin intake was only 47 % of the EAR, and this was attributed to infrequent consumption of animal foods except smoked fish, and the negligible riboflavin content of cassava, the dietary staple. In another rural setting, 99 % were below the EAR for riboflavin and only 37 % achieved the EAR for vitamin A. Authors explained that this may be due to rare consumption of fresh fruit and the fact that vegetables are simmered for several hours, causing extensive losses of vitamin C(Reference Wegmüller, Camara and Zimmermann37).

In children aged 2–19 years, the prevalence of diabetes was reported to be 0·4 % (fasting glucose ≥ 7 mmol/l) and 17·2 % for impaired fasting glycaemia (between 5·6 and 6·9 mmol/l)(Reference Agbre-Yace, Oyenusi and Oduwole41). The prevalence of diabetes was 10 % among young adults attending University; 12 % also having high arterial blood pressure(Reference Gbogouri, Dakia and Traore40). Pubertal development was described in only one study(Reference Dancesco, Akakpo and Iamandi28).

Food intakes and nutritional practices

One study measured the consumption of fruits and vegetables among those aged 16–30 years. The mean number of servings per day of fruit and vegetables was 3·9, with 64 % having less than five servings per day(Reference Peltzer and Pengpid38). In another survey among university students, 26 % reported never consuming fruit(Reference Gbogouri, Dakia and Traore40). This study was the only one to document further diet practices, showing that 88 % did not regularly have breakfast and that financial problem was a reason for skipping meals in 33 % of cases. Another survey among a similar population highlighted the need for information campaigns on nutrition within the University Healthcare Center(Reference Inghels, Coffie and Larmarange39).

Parasitosis infections

Twelve studies documented infections with parasites, especially in rural areas, which could affect nutritional status (Table 1). Children and adolescents were infected with several types of parasitosis. The prevalence of malaria ranged from 30(Reference Righetti, Koua and Adiossan25) to 58 %(Reference Rohner, Zimmermann and Amon23), infections with hookworm from 13(Reference Müller, Coulibaly and Fürst30) to 54 %(Reference Zimmermann, Chassard and Rohner24) and with Ascaris Lumbricoides from <2(Reference Müller, Coulibaly and Fürst30) to 65 %(Reference Dancesco, Akakpo and Iamandi28). Soil-transmitted helminths were also commonly found from 14(Reference Wegmüller, Camara and Zimmermann37) to 55 %(Reference Rohner, Zimmermann and Amon23).

Factors associated with nutritional status among adolescents

Overall, most studies were descriptive. Among children living with HIV, being male and having advanced disease increased the odds of being undernourished(Reference Jesson, Masson and Adonon44). Children living in a family environment had significantly higher rates of wasting and stunting than those living in specialised centres or institutions for orphans(Reference Beda46). Sleeping <9 h per day was associated with a higher weight (+3·5 kg in females and +2·5 kg in males)(Reference Tiehi48). Obesity was found to be more common in girls than in boys(Reference Kramoh, N’goran and Aké-Traboulsi42,Reference Zahe, Méité and Ouattara45) and was related to high blood pressure but not physical activity(Reference Kramoh, N’goran and Aké-Traboulsi42). Nutritional status was not related to school performance(Reference Zahe, Méité and Ouattara45) and was not associated with mono- or multi-parasitism(Reference Yapi, Ahiboh and Monnet29). Finally, a report stated that body perception was not associated with eating behaviours(Reference Ouattara47).

Regarding micronutrients, no correlation was found between riboflavin intake and anaemia(Reference Rohner, Zimmermann and Wegmueller21). Fe absorption (measuring erythrocyte incorporation of 57Fe) was reduced by afebrile malaria due to inflammation but was not affected by hookworm infection(Reference Glinz, Hurrell and Righetti32). Parasitic infection was also not associated with anaemia(Reference Righetti, Adiossan and Ouattara27), and helminth-infected children had similar VO2 max values to non-infected children(Reference Müller, Coulibaly and Fürst30).

Interventions to modify nutritional status in adolescents

Most of the interventions were micronutrient supplementation or deworming. Three studies conducted in the early 2000s focused on goitrous children and young adolescents (<15 years of age), implementing Fe supplementation and salt fortification (iodised salt) (Table 1). Fe supplementation alone(Reference Hess, Zimmermann and Adou34) or combined with iodised salt(Reference Zimmermann35) reduced Fe deficiency and the proportion of goitrous children. In a 5-year prospective cohort following the introduction of iodised salt in Côte d’Ivoire in the 2000s, there was a significant reduction in mean thyroid size(Reference Zimmermann, Hess and Adou36). Following these studies, dual-fortified salt (with Fe and iodine) was compared with iodised salt and showed better improvement in Fe status, but no difference in Hb concentration(Reference Wegmüller, Camara and Zimmermann37).

A randomised controlled trial involving Fe-fortified biscuits resulted in two articles(Reference Rohner, Zimmermann and Amon23,Reference Zimmermann, Chassard and Rohner24) ; this intervention did not reduce anaemia or hookworm prevalence(Reference Zimmermann, Chassard and Rohner24) and did not increase Hb concentration, even when combined with malaria treatment(Reference Rohner, Zimmermann and Amon23). Finally, a study assessing deworming treatment showed no effect on Hb levels and anaemia but improved performance in physical fitness tests(Reference Hürlimann, Houngbedji and N’Dri31).

Discussion

This scoping review gives an overview of recent research into the nutrition of adolescents living in Côte d’Ivoire. Overall, some studies have been conducted specifically in this population, and most were cross-sectional observational studies. Nutrition-related topics covered were mostly anaemia and Fe deficiency as well as parasitosis; other studies were on diverse subjects with few results on food intakes, diabetes, overweight and obesity.

Studies assessing anthropometry showed that undernutrition is still highly prevalent in this country, in rural as well as in urban settings. Stunting rates found in adolescents were similar to the estimated prevalence among children under 5 years of age (21·6 % in 2018)(6). However, there were higher rates of underweight and wasting found in adolescents (at least 11 %) v. a 6·1 % estimated prevalence of wasting in under fives(6). Higher or similar rates of underweight for adolescents compared with children have been found in multiregional surveys(Reference Galloway, Bundy, Silva de and Horton49). Because no national estimate of malnutrition exists beyond 5 years of age in Côte d’Ivoire, it is not possible to compare these results within the adolescent population which justifies the need to advocate for further data and adolescent research. As adolescents have higher absolute energetic needs than during any other life period(Reference Gidding, Dennison and Birch50,Reference Das, Salam and Thornburg51) , a poor-quality diet cannot cover these and may result in higher rates of undernutrition than during childhood. Also, overweight and obesity are an emerging public health problem, which could worsen in the coming years, due to increasing consumption of sweets and saturated fat-rich food(Reference Patton, Sawyer and Santelli2,Reference Muthuri, Francis and Wachira3) . Indeed, a rising prevalence of overweight and obesity is observed worldwide, even in West Africa(52). Among adults in Côte d’Ivoire, higher rates of overweight and obesity are associated with higher socio-economic level. This has been attributed to more sedentary lifestyles and changes in dietary patterns, influenced by the introduction of fast foods and other westernised foods at the expense of the traditional diet(13). The prevalence of diabetes in Côte d’Ivoire estimated by the non-communicable disease Risk Factor Collaboration was 6·3 % for women and 7·3 % for men in 2014 and continues to increase(53). Although studies on diabetes and hyperglycaemia were not included in our search strategy initially, we reported two studies that show a prevalence of between 10 and 20 % for impaired glycaemia or diabetes in adolescents. No further data are available among adolescents in Côte d’Ivoire regarding diabetes.

Anaemia and Fe deficiency are a major public health concern, widely documented in different age groups. Our review indicates that the prevalence of anaemia among adolescents remains high and could be explained by several factors, such as persistently high rates of infectious disease (malaria and other parasitosis), nutritional deficiencies (Fe, vitamin B12, folic acid, vitamin A) and low dietary Fe intakes(Reference Engle-Stone, Aaron and Huang54). Reducing the prevalence of anaemia is a priority of the current National Multisectoral Nutrition Plan in Côte d’Ivoire and the government aims to reduce it from 75 to 60 % in children and from 54 to 42 % in women of childbearing age between 2016 and 2020, promoting essential nutrition actions such as good nutritional practices and consumption of micronutrient-rich foods(13). However, studies of Fe fortification in our review showed only modest effects, whereas it has been effective in improving Hb and reducing anaemia in other contexts(Reference Gera, Sachdev and Boy55). As the burden of Fe deficiency anaemia has been shown to be detrimental in terms of economic losses and health impact, increasing disability-adjusted life years, food fortification and infectious disease prevention and control are urgently needed in Côte d’Ivoire(Reference Prieto-Patron, Hutton and Fattore56).

Other micronutrient deficiencies such as vitamin A and vitamin B2 were explained by insufficient nutritional intakes, due to a lack of dietary diversity and limited consumption of fruit and vegetables. Other sources of vitamin A or vitamin B2, such as red meat, eggs, fish or dairy intakes, were not explored. Iodine deficiency and associated thyroid dysfunction have been reduced since the introduction of iodised salt(13) (the iodine studies included in the literature review pre-dated the introduction of iodised salt). Overall, results on micronutrients were limited to Fe, vitamin A and vitamin B2. Other micronutrient deficiencies such as Zn, Ca and Mg have been insufficiently explored in Côte d’Ivoire, to our knowledge, constituting a major gap in research data.

High rates of parasitic infection were another important concern (malaria, helminths, hookworm). Deworming interventions did not show significant effects on nutritional status in adolescents(Reference Hürlimann, Houngbedji and N’Dri31), which is in line with a systematic literature review conducted in children aged 16 years or less(Reference Taylor-Robinson, Maayan and Soares-Weiser57). Parasitism may, however, lead to multiple co-morbidities requiring treatment(Reference Lo, Addiss and Hotez58). A cost-effectiveness modelling study based in Côte d’Ivoire demonstrated that expanded community-wide deworming interventions were highly cost effective in terms disability-adjusted life years averted(Reference Lo, Bogoch and Blackburn59). Deworming campaigns are part of the National Multisectoral Nutrition Plan in the country, targeting pregnant women and children aged 1–12 years, but largely missing the adolescent age group(13).

Study limitations

The main limitation of this review was that only one bibliographic database was used. As our aim was to scope research already conducted into adolescent nutrition, we did not use other databases; our hypothesis being that most of the relevant studies would be referenced on PubMed. Few reports from the grey literature were found. Indeed, the searching process for grey literature was difficult, as listing of reports in university libraries was lacking. This may have under-estimated existing literature, especially that done by students or as part of national programmes. The search strategy was limited to quantitative studies. Qualitative studies were not included as they required specific key words for the search strategy, and because the results obtained have to be summarised in a different way. A specific literature review on this topic looking at qualitative studies conducted in TALENT participating countries has been done for this themed issue.

The literature review resulted in a small number of studies, with considerable heterogeneity regarding topics of interest, and data and outcomes collected, making it impossible to conduct meta-analyses. Quality assessment was not conducted, because the aim was to document what has been done and what kind of nutritional studies have included adolescents. However, this is to our knowledge the first literature review exploring adolescent nutrition in Côte d’Ivoire, including articles published in English and French, allowing us to identify gaps and plan future research.

Whereas it might have been interesting to extend the scope of this review to West Africa as a whole and not to a single country, we felt that our results provide a comprehensive description of adolescent nutrition research studies in Côte d’Ivoire that would not have been possible in a regional review, this topic remaining highly neglected and under-studied so far. This review can be seen as a preliminary step to support further research, in order to get a better picture of the adolescent nutrition situation in West Africa in the coming years.

Implication of the results and perspectives

The main lesson of this review is that more research is needed into adolescent nutritional health in Côte d’Ivoire. Most of the studies identified were not focused on adolescents aged 10–19 years or did not provide disaggregated data by age. Research to understand the causes of Fe deficiency and anaemia and into the reasons for a poor response to supplementation or fortification are required. Data on micronutrient status going beyond Fe, vitamins A and B2 are markedly lacking. There is also a lack of information on dietary intakes and potential determinants of diet and nutritional status.

With the sub-region experiencing a nutritional transition, with greater access to unhealthy foods and the development of non-communicable diseases(Reference Audain, Levy and Ellahi60), leading to a double burden of malnutrition(Reference Caleyachetty, Thomas and Kengne61), new research documenting this transition and how it impacts adolescent health is needed. Availability and access to healthy food may become a systemic challenge in this region that will have to be addressed. Innovative interventional research is needed, including prevention messages on good nutritional practices and physical activity, as well as nutritional education and food/nutrient supplementation.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank our partners from Abidjan who help us to conduct this study and the TALENT collaboration for its support. Financial support: The TALENT collaboration was funded by a Global Challenges Research Fund/Medical Research Council pump priming grant (grant number: MC_PC_MR/R018545/1). The funding agency was not involved in the study design, data analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: J.J. wrote the manuscript which has been reviewed by all co-authors. J.J. and K.K. conducted the literature search independently and then discuss the discrepancies. E.K.V.K. conducted the grey literature search. S.V.W. established the initial literature search strategy, which has been revised and approved by the TALENT literature review working group. C.F. was the main investigator of the project, and L.A. and V.L. were the local investigators in Côte d’Ivoire. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020002621