When the American Teacher appeared in January 1912, its editors, New York City teachers financing the periodical from their own pay envelopes, announced an intention of “cooperation” with their “official superiors.” Though humble to the point of deference, this tone was strategic, easing the periodical's reception with two distinct audiences: New York's many thousands of schoolteachers, cautious if not conservative and needing to be coaxed into taking action for themselves, and administrators, whose power advised tactical restraint. Yet for all its conciliatory connotations, the word “cooperation” coursed with vibrations of change. Since Board of Education members, superintendents, and principals were not the only ones “giving their time, energy, and spirit to the social obligation of educating the young,” proposed the American Teacher, “a large portion of the constructive ideas presented for general consideration should come from the teachers themselves.” This was a significant demand upon a male-dominated educational hierarchy in an era when most teachers were women who lacked the right to vote or hold public office. “Cooperation” implied twin aspirations: power for women and teacher power.Footnote 1

The American Teacher led directly in 1913 to the Teachers’ League of New York, which in 1916 became the Teachers Union of the City of New York. That same year, the Teachers Union became Local 5, one of the first six locals of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT). The American Teacher became the national publication of the AFT, Local 5 its largest local. These were significant developments in the history of public-sector unionism and American education, but the genesis of New York City teacher unionism within the Teachers’ League between 1912 and 1916 is barely mentioned in general histories of American teacher unionism, which concentrate instead upon the Chicago Teachers Federation (CTF), founded in 1897, and its leader Margaret Haley.Footnote 2 As for studies of New York teacher unionism, they chiefly concern its midcentury storyline. In 1935, during the Great Depression, a struggle for Local 5 culminated in its takeover by Communist Party members, causing the union's founders to form the breakaway Teachers Guild. In 1941, the AFT expelled Local 5, which lingered on as the Teachers Union until destroyed by McCarthy–era investigations. The AFT recognized the Teachers Guild, which in 1960 fused with another organization to form the United Federation of Teachers (UFT), soon dominated by Albert Shanker, a fierce Cold War liberal who later became AFT national president. The UFT confined teacher interests to bread-and-butter contractual bargaining, an approach that reached a flashpoint with the bitterly divisive 1968 Ocean Hill-Brownsville strike that pitted Jews against blacks over community control of schools.Footnote 3

That event excited historians’ interest in the history of teacher unionism—and in the relationship between educational history, labor history, race and ethnicity, and the history of social movements—while simultaneously conditioning how that past was imagined. Memories of the 1960s were fresh when young historians in the 1970s and early 1980s began to explore the origins of New York City teacher unionism. Shanker still dominated the AFT, helping to explain why the most extensive published account of early New York City teacher unionism was unrelentingly critical of it. In Why Teachers Organized (1982) and a companion article, Wayne J. Urban—an admirer of the “tough, pragmatic trade unionism under Albert Shanker”—delivered a thoroughly negative verdict against the Teachers’ League and Teachers Union of the Progressive Era. Their radicalism, he held, “put them out of touch with the concerns of most of the city's teachers.” Their leaders were unrepresentative male high school teachers and “heavily Jewish, surely an impediment to membership among Anglo-Saxon and Irish Catholic elementary school teachers.” Urban believed teacher unions succeeded only when they adhered to a self-interested, economistic union model that pursued “material improvements, salaries, pensions, tenure, and other benefits” and institutionalized “experience, or seniority, as the criterion of success in teaching.” Since neither the Teachers’ League nor the Teachers Union fit this mold, Urban classified them as aberrations, praising instead the Interborough Association of Women Teachers led by Grace C. Strachan as New York teachers’ authentic representative.Footnote 4

Early New York City teacher unionism could look very different when viewed through another prism, the example of 1960s radicalism. Lana Muraskin, who completed her dissertation on the Teachers’ League and Teachers Union in the New Left atmosphere of the University of California–Berkeley, offered an approach far more receptive to dissenting social movements, but because she left academia to pursue educational policy research, her historical work went mostly unpublished.Footnote 5 Left unchallenged, Urban's perspective took hold. The view that early New York teacher unionism was ineffective due to its radical strategy and limited composition of male high school teachers, heavily Jewish, has strongly influenced subsequent narratives, even of historians otherwise open to left-wing unionism.Footnote 6 Today, however, a fresh context exists for posing the question of why teachers organized. The decline since the 1980s of the type of unions long cast as realistic by conventional labor officials; the rise of unprecedented wealth and income inequality; the revival of socialist politics in the United States in the campaigns of Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez; and the eruption of militant teacher unionism as exemplified by the Chicago Teachers Union and mass teacher strikes in West Virginia, Arizona, and Oklahoma all create space to reconsider the history of teacher unionism.Footnote 7

Drawing upon neglected source materials to reconstruct for the first time the whole history of the Teachers’ League and the founding of the Teachers Union, this article recasts the history of New York City teacher unionism in the Progressive Era. The Teachers’ League and early Teachers Union were indeed spearheaded by a cohort with political views distinct from the mass of teachers, but, like other successful militant minorities, wove common complaints and aspirations into programs that won mass support. While two male high-school teachers initiated the American Teacher, women wrote for it from the start and were central in the Teachers’ League and Teachers Union, whose leaderships were typically composed of elementary school teachers and women. These organizations welcomed Jews but were not predominantly Jewish in this period, their claim to distinction being inclusivity and heterogeneity. More conservative educators—Strachan in particular—did oppose them, but that did not prevent the Teachers’ League and Teachers Union from becoming popular organizations comparable in size to, if not larger than, other teacher organizations in New York City and teacher unions elsewhere. Their leaders’ socialist commitment drew repression, but it also enabled them to craft a powerful analysis of workplace discontents, launch unionism in the schools, and persevere through the tumult of the First World War and its aftermath, even as those developments nearly destroyed the union.

The founders of New York City teacher unionism aspired to supplant what they perceived as the autocracy of the educational officialdom with democratic decision making. This confutes any claim that business unionism, or the pursuit of sectoral self-interest in contractual bargaining, was the sole legitimate form of teacher unionism, or its most effective form. Early New York teacher unionism was social unionism, subscribing to the view that unions should advance the interests of the whole working class to transform society. Its leaders, both men and women, were feminists active in campaigns for women's suffrage who identified with the broader labor movement in the belief that teachers had a professional obligation to seek a more egalitarian society.

While pensions and pay were salient in the organizing drive of New York City teachers, a bread-and-butter template misses the potency of other issues, all rooted in teachers’ work lives and connected to the aspiration of self-management. One was a prototype of body politics and reproductive rights: the freedom of women teachers to marry, have children, and continue to work. The others included freedom of speech, teacher ratings, and representation on the Board of Education. These objectives recommend a more expansive understanding of material interest. As educational centralization and expansion drove New York City school administrators to emulate corporate efficiency, teachers’ calls for greater democracy and women's equality in work life pointed to a reconstitution of the political economy of education, with implications for capitalism itself. As one teacher wrote, “The aims of education and the economic order are incompatible.”Footnote 8

The Teachers’ League and Teachers Union point to the embryonic aspiration for the transcendence of gender within a highly gendered American cultural frame. Historians of the early twentieth century have identified a cult of masculinity in response to the consolidation of corporate capitalism, as personified by Theodore Roosevelt, champion of strenuous virility, progressive reform, white supremacy, and empire.Footnote 9 In the Progressive Era, writes Kimberly A. Hamlin, “gender binarism” was pervasive; Victorian separate spheres broke down as women entered education, employment, and reform movements, but the gender order reconstituted itself such that the period's political and reform organizations were overwhelmingly “sex-segregated and gender-based.”Footnote 10 The Teachers’ League and Teachers Union instead emphasized the unity of a common humanity, manifesting June Sochen's characterization of the era's feminists as seeking “an egalitarian society … both classless and, in a sense, sexless.”Footnote 11

In a time when many unions were exclusively male, most schools sex-segregated, and social reform organizations and clubs sex-specific, the Teachers’ League and Teachers Union drew men and women together in common cause and vigorously opposed discrimination against women. In a time when coercive assimilation, xenophobia, and nativism were on the rise in reaction against immigration from southern and eastern Europe, immigrants and Jews played a role from the beginning in the teachers’ movement, while all its members saw their educational mission as one of supporting their polyglot, heavily immigrant, and largely working-class pupils. In a time when the middle class frequently attempted to restore social control by disciplining the urban masses, these college-educated, white-collar employees, chafing at arbitrary managerial authority, considered themselves “brain workers” and identified with the cause of labor, fusing professional and class consciousness. Moreover, in a time when many progressive reformers and much of the women's suffrage movement bought into white supremacy, the Teachers’ League dispensed with vocabularies of race and exclusive nationalism, and the Teachers Union, once formed, opposed racial segregation and inequality in education forthrightly.

Radical egalitarianism was paramount both to these teachers’ methods of organizing and to their core position of opposition to authoritarianism in the school system. If the Teachers Union was, as one writer declared at its birth in 1916, an organization of “the free teacher, the teacher relieved of supervisory persecution,” and “a power towards democracy in our schools,” it was equally a project to transform and deepen democracy in American society.Footnote 12

The American Teacher

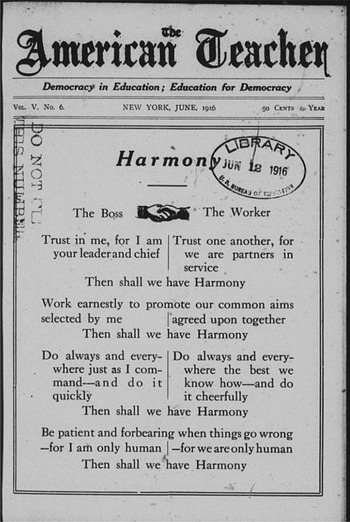

“Democracy in Education; Education for Democracy” was the slogan that ran under the masthead of every issue of the American Teacher, a periodical that provided a forum for teachers to clarify objectives, reflect on pedagogy, and probe patterns of educational management, all in a spirit of social idealism and educational reconstruction. “The name America has stood for nearly a hundred and forty years as the symbol of Democracy,” its first editorial stated. “To be sure, it has also stood for raw culture, for the spirit of brag, for graft and for dollars. But to millions abroad, as well as to millions here, it has meant Democracy.” Teachers had a special role to play in realizing that ideal, for imbuing democratic consciousness in pupils is “the main purpose of the public school.” The problem, observed the editors, was that “the teacher and the pupil, the principal and the superintendent find themselves enmeshed in a system that restricts initiative, stratifies intercourse, suppresses individuality, frowns upon originality, cultivates servility and penalizes sincerity.”Footnote 13

About a dozen New York City teachers produced the American Teacher (Figure 1). At its heart were editor-in-chief Henry Richardson Linville, a 45-year-old Missouri-born science teacher at Jamaica High School who graduated from the University of Kansas and held a doctorate in biology from Harvard University, and managing editor Benjamin Gruenberg, a 37-year-old Russian Jewish immigrant raised in Minnesota who held a doctorate from Columbia University, published a number of scientific articles, and was a biology teacher at the High School of Commerce. They knew one another from their days at DeWitt Clinton High School in Manhattan, where Linville chaired the department of biology between 1897 and 1908, pioneering a nationally influential curriculum reflective of modern scientific method. Gruenberg's vocal criticism of principal John T. Buchanan led to a negative teaching rating and the denial of his teaching license by the Board of Education. Linville came to his defense, and the Board relented and granted Gruenberg's license, but it transferred both men away from the school—a bitter experience that infused them with a passion for democracy in education.Footnote 14

Figure 1. The June 1916 issue of the American Teacher, published shortly after the birth of the Teachers Union and American Federation of Teachers, illustrating the ambition of early New York City teacher unionism to replace managerial authoritarianism and bring about a democratic, cooperative, self-managed school system “agreed upon together.” Library of Congress.

“At present,” wrote Linville in 1912 of the American Teacher, “all the editors are members of the Socialist Party, but we may soon become associated with others who are ‘progressive,’ meaning those who are following rapidly behind.”Footnote 15 This confidence of being in the forefront of social transformation reflected the Socialist Party of America's rapid advance. Founded in 1901, it was by 1912 a national force boasting hundreds of newspapers, more than a thousand elected officials, strength at the polls in such cities as Milwaukee and states as Oklahoma, and a popular presidential candidate in Eugene V. Debs, the former railway union leader who garnered almost one million votes that year. In New York, the Socialist Party had a significant presence in the campaign for women's suffrage, in the garment trades, and among Jewish immigrants of the Lower East Side, who two years later would elect socialist Meyer London to represent them in Congress.Footnote 16

Although socialists were at its core, the American Teacher was never a socialist periodical, aiming to attract as many teachers as would take interest in a self-managed school system. As Linville put it, “Undoubtedly these are socialistic ideals, but we have not branded them as such ourselves.”Footnote 17 The editors came together spontaneously rather than at the call of the Socialist Party; indeed, direction flowed the other way as the teachers influenced the Party's municipal planks, which on education included smaller class size, increased teacher salaries, free school lunches, and new school buildings.Footnote 18 Yet from the outset, the American Teacher sought to connect teaching to the great stirrings of social reform in the Progressive Era. In “Teaching Social Science Through Newspapers,” Mark Hoffman, a Stuyvesant High School teacher born in Russia, advocated that teachers convey a “sense of the social unrest” through classroom use of newspaper articles on such topics as trust-busting and strikes. Although “the teacher must beware of committing himself to any propaganda,” he wrote, exposure to “events which mean ultimate social reconstruction or betterment” would mean that students would no longer graduate from high school believing “that they have no other work in this world than to pounce on their fellow human beings and get a bigger share of the world's goods.”Footnote 19

In the 1890s, New York City's schools had been centralized at the initiative of Nicholas Murray Butler, with elite support, so as to remove education from ward politics, reorient the curriculum to support the needs of industry, and produce cost efficiencies. A new Board of Superintendents now managed teaching staff, complementing the Board of Education that oversaw the system's business aspects. The result was to subject teachers to a powerful, remote bureaucracy.Footnote 20 The American Teacher sought to reconstitute this system. In the first year, it scrutinized “efficiency,” the Progressive Era managerial ideal, criticizing its application to educational settings as a pretext for overbearing dictation from above, and holding that only cooperative processes could produce optimal educational outcomes.Footnote 21 “Naturally, we are starting the movement for the democratic management of the schools with more enthusiasm than resources,” Linville wrote to John Dewey, the Columbia University philosopher who would write for the American Teacher and learn from it in shaping his own ideas about American education, culminating in Education and Democracy (1916). “But we are willing to wait for the teachers to begin to pay attention, and later, for them to begin to think.”Footnote 22 Questioning of administrative prerogative became bolder and bolder. By the third issue, an editorial on “Democracy and the Teacher” called for “a voice and a vote in the government of our schools,” filling the entire front page and holding that teachers’ work was “so low in the scale of trades or professions” as to make them “hirelings and underlings”: “Teachers are underpaid and overworked and are treated with scorn and ridicule. Even if it were true that they have not measured up to the highest efficiency, the fault is rather with their training and with the miasmatic environment of servility and slavish obedience.”Footnote 23

From the start, the American Teacher offered a platform for women's voices, including Charlotte Perkins Gilman, then American feminism's most distinguished intellectual and a staunch socialist-feminist proponent of women's economic independence.Footnote 24 In the magazine's core editorial circle, the most prominent woman was Henrietta Rodman, born into a venerable American family to become a free-spirited socialist, paradigmatic “new woman,” and instructor at Wadleigh High School who advocated vocational education for girls in an age when numerous obstacles impeded women's entrance into the workplace.Footnote 25 Kate E. Turner, assistant principal at Erasmus High School, Brooklyn, also advocated girls’ vocational education in the American Teacher.Footnote 26 Adele Miln Linville—born in New York to English immigrants, active in the Equal Franchise League and Woman's Suffrage Party, and spouse of Henry Linville—contributed articles on Maria Montessori's new preschool and kindergarten method, exemplifying the American Teacher's desire to involve elementary school teachers and early childhood educators.Footnote 27

“We want to draw every branch of the profession into this, from the grades up,” Henry Linville confided to a correspondent, “but naturally there are very few in the so-called lower ranks who are doing any thinking.”Footnote 28 The qualification “so-called” signaled Linville's dissent from those administrators and high-school teachers with advanced degrees who considered primary school teachers lesser, but his simultaneous view that only those around the American Teacher were “doing any thinking,” like his earlier presumption that progressives trail socialists, displayed his tendency to conceive of the band around the journal as a moral elite—an outlook rife with potential pitfalls. Subsequently, his fair-minded leadership style would prove that Linville's dour appraisal of grade-school teachers’ consciousness was not condescension but the organizer's vexation at trying to rouse a cowed, docile constituency to act on its own behalf. Anna Yiezierskaya, a schoolteacher later to gain renown as a novelist, had come to much the same conclusion, writing that because of the “deadness” instilled by the system, “the average school teacher does not think.”Footnote 29

This speaks to a paradox faced by those aspiring to wrest greater structural involvement for teachers in decision-making: the very bureaucratic hierarchy that denied teachers power left many apathetic, dull, or fearful—and consequently unwilling to assert themselves. “In our campaign we have already learned that the great majority of teachers regard with dumb or indifferent interest the rather new proposition that they might some time take a hand in deciding out of the abundance of their experience what policies are best for making education effective,” wrote Linville, “although these same people will spend hours discussing the educational government when it happens to tread on their particular corns.”Footnote 30 Some teachers, fearing reprisal from their principals, hesitated to subscribe to the American Teacher.Footnote 31 Others had such a “deepseated hatred and disgust of our educational officialdom,” wrote one, that they declined even to read the American Teacher, wondering, “What's the use?”Footnote 32 Inertia, fatalism, timidity, and cynicism were not universal. The American Teacher's devotion to improving working conditions and achieving a deeper democracy had begun to attract excitement among enough teachers that the editors in the beginning of their second year readied for a special print run of 12,000.Footnote 33 Tremors of change began to reverberate. At a men's teachers’ association banquet, a Board of Education commissioner, asked whether the board should add a teacher representative, responded affirmatively—and one elected by the teachers. An astonished Linville wrote, “The motto Democracy in Education was a practically unused phrase in New York before the paper began to make it known a year ago. Now it seems it belongs to practically everybody.”Footnote 34 It was a moment ripe for organization.

Creating the Teachers’ League

On January 18, 1913, eighteen teachers gathered by the American Teacher and “representing the various radical interests,” as Linville put it, met at the Finch School, a private girls’ preparatory school founded on the Upper East Side by Jessica Finch, a socialist and feminist.Footnote 35 Two weeks later, the cohort met at the East 22nd Street office of the Women's Trade Union League (WTUL).Footnote 36 Their link to the WTUL was through Rodman and Caroline L. Pratt, a Teachers College graduate, manual training school teacher, Socialist Party national education committee member, and lifelong companion of Helen Marot, WTUL secretary. Pratt would play a significant part in the teachers’ movement until the following year, when her energies turned to founding the Play School in Greenwich Village, which became the legendary City and Country School.Footnote 37

From these two meetings came a call signed by twenty teachers to launch a new organization, soon to be known as the Teachers’ League, with the stated objective of achieving teacher representation on the Board of Education. Seven signatories came from elementary schools, one from a manual training school, one from a teachers’ training school, and eleven from high schools. Five were women: Rodman, Pratt, Turner, Mary K. Smith, Jamaica Training School, and Mary S. Marot, PS 76, Manhattan (sister of Helen Marot).Footnote 38 The participation of such women, none Jewish, and the feminist surroundings of these meeting places contradict the widespread assumption, beginning with the union's in-house historian Thomas R. Brooks, that Jewish male high-school teachers largely created the Teachers Union.Footnote 39 Of the twenty signers, only six (30 percent) were Jewish. Gruenberg alone taught high school, the others being Polish-born Joseph B. Fish, PS 10, Manhattan; J. Greenberg, PS 9, Bronx; Russian-born Simon Hirdansky, principal of PS 4, Bronx; Russian-born Gabriel R. Mason, PS 62, Manhattan; and Galician-born J. E. Mayman, PS 84, Brooklyn.Footnote 40 Not the preponderance of Jews but equal Jewish involvement was the noteworthy aspect of this composition in an era when dominant racial-nationalist ideology distinguished Jews not only from Protestants and Catholics but as “Hebrews” from “Anglo-Saxons” and “Teutons”—or even “Americans.”Footnote 41

What distinguished the League, besides its demand for Board representation, was its capacious inclusivity. New York City already had dozens of teacher's organizations—clubs, effectively—organized by borough, subject, sex, or level of instruction: the Association of Elementary Teachers of Modern Languages, the Women's Educational Council of Queens, the Men High School Teachers Association, the Assistants to Principals Association. The new initiative proposed to transcend such parochialism. “I have no toleration for a male teachers or female teachers association, or for a Bronx-first-to-third-grades-unmarried-male-teachers association,” Gruenberg wrote to L. H. White, PS 3, Brooklyn. “… All grades, sexes, subjects, ranks and localities must be forgotten. We must stand or fall together as members of a profession, and not as residents of Flatbush or Harlem; as public servants, and not as supervisors and supervised; as skilled workers, and not as males or females.”Footnote 42

On February 28, 1913, at 8:15 p.m., two thousand teachers met the call for a new teacher organization by attending a meeting at Milbank Chapel, Teachers College, on 128th and Broadway. With Linville presiding, they heard addresses by Dewey on “Professional Spirit,” Gilman on “The Teacher and the State,” Independent editor Edwin E. Slosson on “Uniform Education,” and Superintendent Albert Shiels on “Democracy.” Although the last speaker rejected Board of Education teacher representation, several hundred teachers nonetheless remained for a business meeting to discuss forming a Teachers’ League with that aim.

Controversy soon erupted as Frances Isabel Davenport, a teacher of psychology at the New York Training School for Teachers, objected that the proposed constitution should have emerged from the assembly, not a set group. Next, the realism of allowing teachers to choose Board of Education representatives was called into doubt by Interborough Association president Grace Strachan (Figure 2). Did any American school system, she asked, permit that? Charles A. Tonsor, Jr., PS 17, Brooklyn, responded, saying that a draft of the new organization's constitution was required to provide a basis for discussion; that in Fall River, Massachusetts, all women, teachers included, had the right to vote in school board elections; and that since the meeting was about whether to form a Teachers’ League it should be one of teachers. This last point implied criticism of Strachan's presence, since she was superintendent of two Brooklyn districts in the city system. Strachan countered by attacking the proposed constitution for setting a quorum of only twenty-five among New York City's 17,000 teachers and accusing the organizers of seeking to boost circulation of the American Teacher, which the draft constitution would make the League's official organ. Strachan then walked out, taking her supporters with her and causing “pandemonium to break loose,” according to a news article subtitled “Quits Meeting in a Huff”: “There was yelling from every quarter of the hall and the situation was momentarily beyond the control of the chairman.” Once calm was restored, the 200 remaining teachers approved the constitution, but only after altering it to require a fifty-member quorum for League meetings and expand the proposed executive board to include four officers and fifteen other members: five from high schools and ten from elementary schools. The American Teacher remained independent, never to be the League's official voice, despite their clear association.Footnote 43

Figure 2. Grace Strahan, president of the Interborough Association of Women Teachers and a district superintendent, led the teachers’ campaign for equal pay for equal work but proved a strong conservative feminist opponent of the Teachers’ League and Teachers Union. Library of Congress.

The Teachers’ League had permitted its structure to be revised in open assembly and guaranteed that its leadership would have a higher proportion of elementary schoolteachers than the group that initiated the League.Footnote 44 Strachan's behavior, however, showed the challenges that lay before a new organization conceived on universalist principles in a landscape already dotted with sectoral teacher organizations. Strachan was a formidable presence in New York teachers’ consciousness, having led the Interborough Association on a crusade beginning in 1907 to eliminate the words “men” and “women” from the city's salary schedule for teachers. That equal-pay campaign proved highly popular with women teachers and had the support of most of the city's trade unions.Footnote 45 Although opposed by a rapidly formed Association of Men Teachers and Principals of New York, the conservative New York Times, and the Board of Education, an equal-pay measure was enacted by the state legislature, governor, and mayor in 1911. It set an important precedent in the legal principle of gender equality, but made far more difference at the level of principals and superintendents than elementary schoolteachers, where starting men teachers’ salaries were sharply reduced and women's raised by token amounts.Footnote 46

The Teachers’ League opposed legal discrimination on the basis of sex but equally manifested the desire of many teachers—women and men—to unify and move toward a broader agenda. The American Teacher held that “the work of teaching must be done by men and women of high purpose, without narrowness and without sex-antagonism.”Footnote 47 Leaders of single-sex organizations such as Strachan perceived the League as a threat to their mission, base, and power, and historians have speculated that the divergence of the Teachers’ League and Strachan may owe to a gulf between male high-school teachers and women elementary teachers.Footnote 48 The ferocity of Strachan's intervention at the League's founding meeting, however, combined with the challenge to her from the floor by an elementary school teacher, indicates the welter of cross-currents at work, including hierarchy, class, and politics. The Teachers’ League, as the New York Tribune reported, had “as members teachers in both high and elementary schools, and of both sexes, throughout the city.”Footnote 49 Strachan, for her part, was a reformist but equally an ambitious administrator with often deeply conservative impulses.

By its second meeting, held a week later at the High School of Commerce, the Teachers’ League had 400 members. Despite a meeting time conflicting with that of the Interborough Association, prompting some teachers who belonged to both groups to tack between the two, the League's 230 attendees were at near parity with the Interborough Association's 250 that night. The League elected Linville president; Isabel A. Ennis, PS 27, Brooklyn, vice president; Della Marsh, PS 9, Brooklyn, treasurer; Arthur A. Bryant, DeWitt Clinton High School, secretary; and fifteen executive committee members. Of nineteen leaders in total, ten were primary school teachers, nine women, and three Jewish—one of whom, Hoffman, was a high-school teacher.Footnote 50 Those elected included Davenport, suggesting an organizational culture that welcomed dissent, given her objection at the first League meeting; the following year, she would be elected League vice president. The League began to address working conditions by establishing fourteen committees tasked with issues such as the poor physical condition of schools, classroom overcrowding, teacher salaries and ratings, “the excess of clerical labor,” the status of women teachers, ongoing professional training, and schools’ “relation to the real needs of life in the present era.”Footnote 51

The Teachers’ League conceived of itself not as a union but as a broad educational association seeking democratic transformation of the educational system. While it meant to assist in “the struggle of the teachers against overbearing rule,” it was open to principals (even, in theory, to superintendents) so long as they were willing to accept the principle of teacher participation in management and welcome teacher assertiveness on matters such as curricular reform.Footnote 52 “Teachers Want to Upset Old System” and “Teachers Seeking Power” read headlines in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, a newspaper that produced detailed coverage of education and looked favorably upon the Teachers’ League because it was owned by William Randolph Hearst, then still in his quasi-radical phase.Footnote 53 The League's widely reproduced “revolutionary programme of reform” proposed that each school elect its principal and that school policies be submitted to teachers’ votes, replacing what the League called the “ideal dominant today,” namely “autocracy—sometimes benevolent, very often lax, and frequently tyrannical.”Footnote 54 In May 1913, two moderates who sought a merely consultative role for teachers resigned from the League's executive committee, one being Tonsor. The rest remained resolute, with Davenport telling a reporter, “We will advocate the appointment of an actual classroom teacher to the district board, now made up mostly of doctors and lawyers.”Footnote 55

As the cause of teacher representation gained momentum, the Board of Education at the end of the school year announced the creation of a Teachers’ Council of elected representatives drawn from all the many teachers’ organizations.Footnote 56 The Teachers’ League sent dozens of delegates to the Council's establishing conference that autumn.Footnote 57 At the same time, it objected to the Teachers’ Council's advisory status, with all final decisions left to the Board of Education and Board of Superintendents.Footnote 58 “It may make a thousand suggestions,” wrote Linville, “but it has no power to carry out a single one of them.”Footnote 59 At the individual school level, the League was heartened by some principals introducing councils that allowed teachers a share in management, although one League member, David O'Keefe, fought charges of gross insubordination filed against him by his principal at Jamaica High School.Footnote 60 League members continued to bridle at arbitrary authority and lack of control over work, as indicated by the titles of announced talks in May 1914: “The Prevalence of Large Classes and the Effect of Them Upon the Teacher's Work and Health” by Sarah H. Fahey, PS 147, Brooklyn, and “The Effect of Unintelligent and Petty Supervision Upon the Rating of Teachers” by Grace E. Spurr, PS 81, Queens.Footnote 61

Self-management guided the League's vision. The vexed issue of teacher ratings presented one opportunity for its implementation. Some members proposed that rather than principals and superintendents conducting ratings, teachers evaluate one another, but the League as a whole passed a unanimous resolution in favor of abolishing ratings altogether. As J. Edward Mayman, PS 64, Manhattan, put it, “No human being should have such power over another.”Footnote 62 Close attention to social and class analysis also characterized the League. Alexander Fichandler, a League member and principal at PS 165, Brooklyn—where a renowned teachers’ council held genuine democratic power—ascribed overcrowded school facilities to “the opposition of the real estate interests to the increased tax budget.”Footnote 63 Social awareness extended to pedagogy, as when Sam Schmalhausen, an English teacher at DeWitt Clinton High School who was born to Jewish immigrant parents on the Lower East Side, contributed an American Teacher article advising teachers to guard against their inner capacity to become unduly punitive against miscreant students, instead recommending a sympathetic, humane search for “the motives behind the act, and more important still, the offender's personal and environmental history.”Footnote 64

Pregnancy, Free Speech, and Pensions: Precipitants of Unionism

That the Teachers’ League would convert itself from a broad association into a labor union was not premeditated but arose out of a confluence of developments, local and national, that came to a head by 1915 and 1916. Compensation was a factor: the League joined other New York City teacher associations in protest against a move to compel the teaching of summer school without additional pay in 1914, and the American Teacher ran occasional articles on salaries.Footnote 65 What propelled unionism most, however, was a controversy over the freedom of women teachers to opt for motherhood. Second and closely related was the right of teachers to freedom of speech, including criticism of the Board of Education. Pensions were a third variable. On each of these crucial points, the Teachers’ League not only contested Board policy but also staked out a position substantially different from that of other teachers’ associations, in particular that of Strachan and the Interborough Association. Insofar as these differences correlated to a division between high school and elementary teachers, it was the Teachers’ League, not the Interborough Association, that attracted the most support from women and primary school teachers.

In the year 1913, when the Teachers’ League formed, the word feminism broke through in American culture.Footnote 66 These developments were more directly related than is generally appreciated. Early in 1913, at its inception, the Teachers’ League established a committee on the status of married women chaired by executive committee member Henrietta Rodman (Figures 3 and 4).Footnote 67 Teaching was often undertaken by young, unmarried women who were expected to resign should they marry. In New York, the supposition that women teachers would be “inefficient” in their professional duties if distracted by obligations to husband and children—and, conversely, that married teachers working outside the home would neglect their maternal and wifely duties—led the Board of Education to forbid the hiring of married women, to allow women teachers to marry only after a definite period of service, and to discourage motherhood.Footnote 68 In 1913, Bridget C. Peixotto, a married teacher at PS 14, Bronx, was discharged for going absent from school to give birth.Footnote 69 “Time was when women who married and took up the burdens of the conjugal relation expected thereafter to devote themselves to the care of their children,” editorialized the New York Times, lamenting that “our public school system is a victim of that comparatively new and distressing malady called feminism.”Footnote 70 Peixotto appealed in the courts while other teacher-mothers resigned in fear and the Board of Education identified fourteen more elementary and two high-school teachers for discharge.Footnote 71 The circle around the American Teacher editorialized for the right of these women to keep their positions in the belief, as Sophie Matsner Gruenberg expressed it in the socialist newspaper the Call, that “anything that interferes with the normal sexual or maternal life of women is socially undesirable.”Footnote 72

Figure 3. Henrietta Rodman, a Teachers’ League executive committee member who also served as vice president of both the Teachers’ League and Teachers Union, was a Wadleigh High School teacher and advocate of vocational education for girls. Courtesy Inez Haynes Irwin Papers, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

Figure 4. Rodman, circa 1914, shown striding in the long tunic she favored as “rational dress.” A socialist-feminist and prominent Greenwich Village radical, Rodman championed the rights of women teachers to marry, have children, and exercise freedom of speech. Library of Congress.

Rodman, thirty-five, was an originator of the new feminism who created her own League for the Civic Service of Women in 1913 to advocate for the rights of teachers to be married, with Linville an active member.Footnote 73 As socialist as she was feminist, Rodman simultaneously chaired the League's committee on vocational guidance, which proposed a radical new curriculum covering wages, industrial conditions, labor movements, and workers’ rights.Footnote 74 In October 1914, as Peixotto's appeal and Board reprisals against pregnant teachers crescendoed, Rodman propelled the Teachers’ League to become the first of the city's forty-five teacher associations to support the reproductive and maternal rights of teachers. As the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported, “The teacher-mothers have the support of one teachers association, the Teachers’ League.”Footnote 75

The League's resolution stated, “Bringing charges of neglect of duty against teachers who are absent in the fulfillment of their God-given duty, maternity, is contrary to the interests of the teachers, the schools, and the community.”Footnote 76 If the phrase “God-given” suggests traditionalism, or at least a gambit to disarm cultural conservatism, it must be understood that even Greenwich Village feminist avant-gardists such as Crystal Eastman viewed motherhood as the central experience in a woman's life. Feminists revered motherhood while refusing to be confined to the home.Footnote 77 By contrast, Strachan of the Interborough Association objected to married teachers in the schools and supported the prohibition against pregnancy. “If a vote were taken among the women teachers in the city today, 95 percent of them would vote in favor of the Board's decision,” she posited to an audience of 400 gathered to discuss the policy, evoking hisses and laughter. “I declare that the married woman who teaches and at the same time attempts to bear children is both unwise and immoral in attempting to serve two masters.”Footnote 78

Entirely free of such bourgeois propriety, Rodman was a Greenwich Village radical and the subject of colorful press coverage for founding a Feminist Alliance to build an apartment house that would include on-site childcare, as well as for retaining her name after a matrimony that she defiantly kept secret for a few months from the Board of Education. Floyd Dell, an editor at The Masses, credited Rodman with the genesis of Greenwich Village as a bohemian center for art and radical politics by moving the Liberal Club there in 1913. “People laughed at her a good deal,” he wrote, “and loved her very much indeed, and followed at her beck into the beautiful and absurd schemes she was forever inventing.”Footnote 79

As the Board of Education moved to discharge mother-teachers in 1914, Rodman published a letter in the New York Tribune accusing its all-male commissioners of “mother-baiting,” a “game” she termed “rather rough”: “Like wife-beating, which used to be so popular, it is always played for the good of the woman.”Footnote 80 Her principal charged her with insubordination and gross misconduct, suspending her without pay for the remainder of the school year.Footnote 81 The Board sustained that decision on December 22 over her objection that it violated her democratic rights. Although League members thought Rodman had been “over-enthusiastic,” they considered the loss of salary unduly harsh.Footnote 82 A few days later, an undaunted Rodman presided over the Feminist Alliance's Christmas ball, at which women dressed in trousers or as they otherwise pleased. In attendance was Linville—who also belonged to the Men's League for Woman Suffrage—and it was announced that the next Teachers’ League meeting would address freedom of speech.Footnote 83

At “Free Speech in the Public Schools,” on January 22, 1915, more than 600 League members approved a resolution committing each to contribute $10 a month to restitute Rodman's projected $1,800 salary loss, and recommending that the Teachers’ Council, not the Board of Education, should judge her case.Footnote 84 Gilman faulted the Board: “We have here an instance of the offended party acting as prosecutor, judge, and executioner—an arrangement quite incompatible with justice.”Footnote 85 Linville warned that freedom of speech would merely create a “misleading” situation for teachers who would remain vulnerable unless democracy replaced autocracy.Footnote 86 At stake, then, were the rights of mothers to remain employed, the rights of teachers to criticize the administrative hierarchy, and the crying need, amplified by the Interborough Association's abdication, for an effective organization of teacher self-defense—all showing the necessity of educational self-management.

Talk of unionism gained momentum. When the wealthy suffragist Mrs. O. H. P. Belmont held a benefit for Rodman, her statement about a union, which the New York Times placed atop its front page, suggested Rodman's coaching: “Let the teachers form a union, and then if a teacher-mother is obliged to absent herself from her school duties and the School Board will not give its consent the teachers can go on strike. If the teachers all strike together, the Board of Education will come to terms very quickly. With a union they would also very soon get women teachers on the board, where they ought to be.”Footnote 87 The glare of public criticism led the Board to reverse course by February 1915, restoring all dismissed mother-teachers to employment and allowing maternity leave. It was a tremendous victory except that the mandatory leave was two years—a sanction in its own right, leaving the American Teacher to object that women should be able to set their own maternity leave duration.Footnote 88 On free speech, the teachers did not even achieve a half-victory; Rodman remained suspended, although she took up writing a column for the New York Tribune in which she promoted the League and continued criticizing various Board policies, the income obviating any need for teachers to pay her salary. The League grew to 600 members.Footnote 89

Across the same span of years, the League carried out a parallel campaign to reform the city's pension fund for teachers. Founded in 1901 to complement those for police and firefighters, the fund become insolvent in 1913. The League's pension committee was initially chaired by thirty-seven-year-old Davenport (Figure 5). Never married, Davenport would by 1920 reside with Margaret E. Sterling, a dress designer, in Greenwich Village at 49 West 12th Street.Footnote 90 Pensions mattered to every teacher, but gender pay discrepancies made them especially vital for women such as Davenport (and Pratt) who formed same-sex households with “devoted companions.”Footnote 91 Davenport exemplified the increasingly credentialed quality of the teaching profession. Schooled in Phelps, New York, she attended Cornell University in 1894–1895, graduated from the New York state normal school at Cortland in 1898, and taught in the high schools of Herkimer and Conatosta, New York, and in the state normal school in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, before studying a year under psychologist G. Stanley Hall at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. Obtaining a Bachelor of Science degree from Teachers College, Columbia University, in 1904, she directed a West Virginia state normal school in 1905–1907 before taking a position at the New York Training School for Teachers. Subsequently, she obtained a Master of Arts in psychology from Columbia in 1912.Footnote 92 Prior to joining the Teachers’ League, Davenport established the Teachers’ Pension Publicity Bureau. As its president and chair of the League's pension committee, she spoke at Education Hall on Park Avenue and 59th Street, together with Gruenberg and Pratt, at a four-hour hearing in December 1913 that drew 1,000 teachers objecting to a new pension bill introduced in the state legislature.Footnote 93

Figure 5. Frances Isabel Davenport, an instructor at the New York Training School for Teachers, served as vice president of the Teachers’ League from 1913 to 1915, president of the Teachers’ Pension Publicity Bureau, and chair of the League committee on pensions. From “Miss Isabel Davenport,” Fairmont West Virginian, June 30, 1906, p. 1. (Newspapers.com).

Even as the Teachers’ League sought a teacher representative on the Board of Retirement, Davenport struck a cautious tone: “Our pension bill must be sound. It must be sufficiently reasonable in its demands upon the city and state as to insure its support by the mayor and governor. It must be sufficiently fair in its demands upon the salaries of the teachers so as to secure their approval.”Footnote 94 By August 1915, the crisis mounted as city controller William A. Prendergast halved the pensions of all 1,549 retired teachers while the system disallowed new retirements.Footnote 95 That year, League pension committee leadership passed to Frederick Z. Lewis, a science teacher at Boys High, Brooklyn, who also chaired the Central Pension Committee, a 150-teacher body advisory to the Board of Education.Footnote 96 Lewis blamed the crisis on the Board spending $2 million of the teachers’ pension fund for extraneous purposes.Footnote 97

In the intricate debate that ensued, the Teachers’ League backed a pension bill that would entail one-third of the cost being borne by teachers and two-thirds by the system, compensate those withdrawing from the system after five years of service or because of disability, and allow a varied payout based on an elective retirement age from forty-eight to seventy after thirty years of service, rather than a fixed age.Footnote 98 Strachan, through the Interborough Association and the Federation of Teachers Associations (FTA), whose committee on pensions she chaired, recommended that teacher contributions be gradated by rank and pensions based on final salary. She maintained that what teachers sought was a pension and not an insurance annuity.Footnote 99 The American Teacher saw only “hazy ideas” and “confusion” in such a distinction, since pensions are annuities. It advocated a “scientific” approach, or actuarial soundness, rather than wish-list postulations.Footnote 100 The League and Strachan differed crucially over whether all teachers should pay an equal percentage of salary and receive the same “flat pension” based on years of service, as Lewis and the League judged most equitable, or contribute by grade of service and receive a pension at half-salary, as Strachan and the FTA advocated, which would mean substantial, even extravagant, pensions for the upper echelons and inadequate ones for most teachers.Footnote 101

The first clash in this policy dispute erupted within the Teachers’ League itself, which had a new president in David H. Holmes, an Eastern District High School teacher of Latin. (The reason Linville stepped down is unclear.) Holmes was a League stalwart, having made the motion that teachers should absorb Rodman's salary loss and having spoken out for teacher representation as chair of the League committee on organization, but his presidency was tempestuous and brief. When Holmes took office in May 1915, Fahey was vice president and Linville remained on the executive committee along with Gruenberg and Rodman; the nineteen leaders in total included eleven women and eleven elementary school teachers.Footnote 102 At the height of the pension crisis, in January 1916, Holmes launched an ad hominem attack on Lewis, stating that the flat-pension proposition would be “gratifying to the insurance companies of New York” and to city leaders—“with both of which groups of altruists Mr. Lewis confesses he has been in close touch for several months, if not years past.”Footnote 103 At a Teachers’ League membership meeting a few days later, Lewis branded this a falsehood and the two men “nearly came to blows,” according to one report. The League upheld Lewis against its president, passing a resolution advocating that “the pension should not be dependent on the amount of value received, but should be alike for all after a definite period of service and at the same age of retirement.”Footnote 104

This position was to be sent to the FTA pension committee, on which Holmes sat alongside Strachan, but Holmes refused. (It may have bearing that Strachan was Holmes's district supervisor, and that as a longtime high-school teacher he would have benefited more from her pension solution.) When the executive committee criticized his failure to carry out the will of League members, Holmes resigned, and the remaining committee members chose Linville as interim president. The League grew increasingly estranged from the FTA, calling it “undemocratic” because most presidents of teachers’ associations were principals and superintendents, a composition reflected in the FTA's preferred form of pensions, which an anonymous circular called a “principals’ measure.”Footnote 105 For all the tumult, the moment was not without humor, as when the American Teacher, in an advertisement most likely the work of Schmalhausen as circulation manager, declared itself in favor of “pensions (before dying).”Footnote 106

Launching the Teachers Union

At a meeting on February 25, 1916, hundreds of Teachers’ League members unanimously repudiated the pension bill favored by the FTA, accepted Holmes's resignation, and elected Linville to serve out the full presidential term. The League then called upon all New York City teachers to join the two million workers in the American Federation of Labor (AFL), with Linville announcing an upcoming teachers’ meeting with Samuel Gompers, AFL president. Not only were pensions on teachers’ minds, so were job security and salary. With a budget crisis looming, the city controller threatened school staff reductions and openly contemplated salary cuts of 10–20 percent, against which the League countered with a demand of tenure and salary preservation. The labor movement, Linville posited, was a logical ally in this fight given its longstanding support for free public education: “The fact that the trade unions in this country, as in England, have always opposed retrenchments in education should be remembered by teachers who have tried the method of gaining support from political bodies in power and have found that method uncertain and rapidly diminishing in value.” At the same time, the League continued to press its core original aim of a democratic school system, unanimously passing a resolution calling upon the Board of Education “to establish the rule of submitting propositions affecting the interests of teachers to a referendum vote of the entire teaching staff.”Footnote 107

The first issue of the American Teacher in 1912 had included an article on “Teachers’ Movements Abroad,” informing readers of a European union federation of more than half a million teachers in fourteen countries, including Germany, England, and France.Footnote 108 Subsequent articles reported on England's National Union of Teachers and teacher unions in Cleveland.Footnote 109 Such unions served as promising beacons rather than models for actual emulation until autumn 1915, when Gompers urged all American teachers to join unions.Footnote 110 Alone out of New York's teacher associations, the Teachers’ League took up Gompers's call, while the American Teacher trumpeted the Chicago success story and ran articles by AFL officials.Footnote 111

It may seem odd that Gompers, the conservative embodiment of male-centered craft organization and pure-and-simple business unionism, might enter into a partnership with a group of teachers inspired by socialism and feminism. One way to reconcile this would be to follow recent creative interpretations and cast Gompers as a radical.Footnote 112 Given Gompers's demonstrable antipathy to socialism, however, the convergence is better understood as an alliance of convenience. The wily Gompers, knowing that New York would be but one local in a national teachers’ union, sought to use radicals to build the AFL, while the New York teachers, supportive of organized labor, knew that if they joined the AFL they could ally with its socialist-led unions such as the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) and contest Gompers's leadership.Footnote 113 As for Strachan, she repudiated unionization as unprofessional, preferring the management-centered National Education Association (NEA). “If we were in a union,” she told New York's teachers, “we might be asked to strike, and no matter how we may feel about the treatment we receive at the hands of the city or the state, we would never think of walking out and leaving these boys and girls without teachers.”Footnote 114 Superintendent William A. Maxwell also conjured the specter of strikes, and the press was uniformly hostile, with even the Brooklyn Daily Eagle editorializing against unionization.Footnote 115

Nonetheless, 2,000 teachers filled the auditorium of Washington Irving High School in Manhattan on March 10 to form a union. A few days before, Gompers spoke to 100 teachers who braved a severe storm to meet him at DeWitt Clinton High School, explaining that musicians, too, had resisted the idea that they were of the “laboring class” but found in unionism an expression of their profession, and that the AFL had a record of winning higher compensation and child labor laws, making it the natural ally of teachers.Footnote 116 “There is not the slightest danger of your union being called out on a sympathetic strike,” Gompers told them, saying strike decisions would always be made by teachers, not the AFL.Footnote 117 Later that night, at a dinner at the Longacre Hotel on 47th Street, Gompers gave an earthy rejoinder to worries that a union would lower the profession: “Hodcarriers get more money than teachers.”Footnote 118

At the March 10 mass meeting, Linville declared, “We must throw off the unjust domination of superiors and acquire a self-respecting independence by organizing.” He objected to budget cuts and the exploitation of substitute teachers, paid less than a living wage and unable to join the regular teaching force. Chicago Teachers Federation (CTF) founder Margaret A. Haley told New York teachers that, in thirteen years of unionism, Chicago teachers had never struck and recounted how the CTF exposed corporate tax evasion to help solve a budget crisis. Leonora O'Reilly of the WTUL, and Hugh Frayne, New York AFL organizer, also spoke. “Time and again,” the Daily Eagle reported, “there were spontaneous outbursts of applause showing that the orators had struck some responsive chord when they spoke of present evils in the educational system.” At a time when the Teachers’ League numbered six hundred members, more than one thousand teachers signed cards to join the new union.Footnote 119

According to Linville, the Teachers Union best represented “the rank and file of teachers.”Footnote 120 The unfolding pension dispute indicates this was no empty boast. Strachan and the FTA backed a pension bill in the state legislature that the Teachers Union, at a meeting of more than 500 teachers at DeWitt Clinton High School, opposed as a hardship upon the lowest-paid teachers, objecting that its salary deduction was “exorbitant” and that it made no provision for dependents in case of death.Footnote 121 The League's protestations that the bill had never been put before teachers led school officials to organize a referendum. Of 18,856 total votes cast in 480 schools, 10,847 opposed the pension bill and 7,901 favored it. All eight associate superintendents and all 26 district superintendents voted for it, as did 1,256 of 1,985 high school teachers and 120 of 153 training school instructors, while elementary school teachers opposed it by 10,104 votes of 16,684 total.Footnote 122 Clearly, the Teachers Union better represented the younger, lesser-paid, and heavily female workforce of elementary school teachers. Strachan blamed rejection of her agenda on “selfishness, socialism, envy, jealousy, and personalities,” while other observers remarked that the vote signified the eclipse of her once-great influence and the emergence of women teachers as an independent power more aligned with the union.Footnote 123 The FTA nevertheless kept pressing for its bill in Albany, where, according to socialist assemblyman Abraham I. Shiplacoff, Strachan “attempted to make a race issue of the bill, saying that the Jewish teachers opposed it.”Footnote 124 The Teachers Union, backed by the State Federation of Labor, prevailed when the legislature narrowly defeated the proposal.Footnote 125

The union's first elected president was Linville, with Lewis as vice president, Alexander Rosen, PS 27, Bronx, corresponding secretary, and Jennie Schmalhausen (Sam's sister), PS 4, Bronx, treasurer. The other executive board members were Mayman; Nathaniel Fogg, PS 169, Manhattan; Marion D. Kelley, PS 165, Brooklyn; Rose Lichterman, PS 47, Bronx; Sara McDermott, PS 171, Manhattan; and Aaron Keil, PS 70, Manhattan.Footnote 126 Thus, elementary school teachers were 80 percent of the first Teachers Union leadership, while women were 40 percent. The increase over the Teachers’ League in elementary school representation reflected support attracted in the pension fight. That half the new leadership—Keil, Lichterman, Mayman, Rosen, and Schmalhausen—was Jewish is explained by the ever-larger numbers of Jewish graduates of City College and Hunter College entering a teaching corps formerly dominated by Irish and German ethnics, and, simultaneously, the victorious mass strikes in the garment trades, which enhanced the prestige of unions and socialism among Jews.Footnote 127 Moreover, as Sherry Gorelick observed, “Just when Jews were moving into the teaching profession, it was being transformed into an administrative structure that diminished the power of teachers while professionalizing them.”Footnote 128 The Teachers Union, which sought to correct for this indignity, was distinct from most teacher organizations in its ethos of openness, internationalism, egalitarianism, and solidarity. This universalism and inclusivity set the stage for increasing Jewish density in coming decades.

Democracy and Unionism

The momentum of the Teachers’ League between 1912 and 1916 seemed to promise a bright future for the new Teachers Union. Instead, a terrible battering lay in store for it in 1917, just as the union celebrated its first anniversary as an organization of “brain workers.”Footnote 129 Many of its members opposed American intervention in the First World War—including Rodman, who spoke on the union's behalf at a suffragist peace rally—and dozens declined to sign a Board of Education loyalty oath, prompting Strachan to form a Woman Teachers’ Loyalty League and insinuate that disloyal teachers had fomented the pension resistance.Footnote 130 That May, the governor signed a measure largely identical to the pension bill she and the FTA sought. Rank-and-file teachers nevertheless elected three opponents of the bill, including Lewis, as their representatives on the new Teachers Pension Board, to which Lewis was re-elected for decades afterward.Footnote 131 Strachan, for her part, surprised everyone that summer with the announcement that she, in her fifties, had secretly married her twenty-four-year-old assistant—and would not give up her career. An Irish Catholic with links to Tammany Hall, she was appointed the first woman Associate Superintendent of Schools, serving until her death in 1922.Footnote 132

The most decisive crisis for the Teachers Union came in November 1917 with dismissal of three DeWitt Clinton High School teachers accused of disloyalty: Thomas Mufson, A. Henry Schneer, and Samuel D. Schmalhausen (Figure 6).Footnote 133 The press branded them seditious Jewish aliens.Footnote 134 Urban faults the Teachers Union for defending their freedom of thought, a position he believes isolated them from other teachers, but for a union built on free speech and democracy—one that continued to articulate the teacher's right to address matters of public controversy inside and outside the classroom—it would have been unthinkable to do otherwise.Footnote 135 Distrust of Allied war aims was widespread in the Irish, German, and Russian Jewish communities from which most teachers came, and that same month Morris Hillquit achieved 22 percent in the New York City mayoral vote, unprecedented for a socialist, largely due to his antiwar position.Footnote 136 What sealed the union's isolation, therefore, was less its stance than press hysteria, ferocious repression, and a resultant pall of fear and coercion. The three discharged teachers could not be saved—nor could Benjamin Glassberg in the 1919 Red Scare.Footnote 137

Figure 6. Late session faculty of the De Witt Clinton High School, a public school for boys, in 1917. Samuel D. Schmalhausen, an English teacher, Socialist Party member active in the Teachers’ League and Teachers Union, and one of three teachers fired during the First World War, is in the center, with prominent ears jutting out, just above the man with monocle. From The Clintonian (New York, 1917).

These highly publicized firings of male, radical, Jewish high-school teachers, along with Abraham Lefkowitz's appointment as the Teachers Union's legislative liaison, left an impression of the union's composition reinforced by historiographical repetition.Footnote 138 Urban's claim that the Teachers Union was predominantly male and Jewish, making Strachan's Interborough Association more representative, resurfaces in a recent article that lauds Strachan and Haley as compeers in New York and Chicago who were sidelined by male high-school teachers whose masculinity was threatened by employment in a traditional woman's occupation and by criticism from women teachers. Linville and other male teachers, this posits, sought affiliation with Gompers's AFL “to shift that balance of power and to affirm an image of self-made manhood.”Footnote 139 To the contrary, Linville was a consistent feminist ally who supported married women teachers, teachers’ maternity rights, and women's suffrage; shared a podium with Haley while Strachan denounced unionism; and retained the confidence of majority-woman executive committees, including the irrepressible Rodman.

The New York teacher unionists did not see the AFL through the lens of conservative male craft unionism. For them, the template was the socialist-led ILGWU with its “largely female rank and file and organization on the basis of industry rather than skill,” as Ann Schofield expresses it.Footnote 140 Women and elementary teachers remained highly active in the early Teachers Union. Minutes show participation by, among others, Mary T. Eaton, PS 11, Brooklyn; Ruth G. Hardy, Girls Commercial High School; Johanna Lindlof, PS 183, Manhatttan; and Ava L. Parrott, PS 115, Manhattan. Three of five Local 5 officers elected in 1920 were women, including Rodman as vice president, as were thirteen of twenty-three executive board members (57 percent). Just under half were Jewish, so far as can be determined, as were the two paid staffers, Joseph Jablonower and Lefkowitz.Footnote 141

More research is needed into the Teachers Union between the First World War and 1929, an understudied phase of its history, but evidence indicates a need to reconsider the historiography's tendency to imply that Local 5 took interest in racial equality only once the communist left pressed the point in the 1930s.Footnote 142 As early as 1918, the American Teacher, still edited by Linville in New York but now the AFT's official voice, condemned racial segregation and inequality.Footnote 143 Two factors may explain why white racism was not focused upon earlier. One is New York City's demography. In the 1910 census, 40 percent of New York City's population was foreign born and only 1.9 percent black, but the latter rose to 2.7 percent by 1920 and 4.7 percent by 1930 with the Great Migration of African Americans from the South.Footnote 144 As Harlem became a black mecca, more New York teachers had African American pupils in their classrooms. Second, the Teachers Union affiliated with black locals in the South when the AFT was born. The first AFT local chartered, Local 1, was the Dunbar-Armstrong Colored Teachers Union organized by black teachers at a Washington, DC, high school. Others followed, including the Howard University Teachers Union and Norfolk Colored Teachers Union.Footnote 145 The American Teacher under Linville published black educators, including a Virginian's proposal that southern school boards include black members and a Washington, DC, teacher's blistering denunciation of the 1919 white-instigated race riots as the logical consequence of segregated schooling.Footnote 146 Lefkowitz, a socialist who served on the National Urban League executive, authored a resolution that the AFL adopted at its 1920 national convention urging unions to appoint black organizers to organize black workers.Footnote 147 At the AFT 1929 convention, he set out motions from the Teachers Union urging the Federation to stand for abolition of Jim Crow educational segregation, equal expenditures for every child in American schools, equal pay for black and white teachers, the organizing of black teachers, and interracial AFT locals unionwide.Footnote 148

Across the 1920s, the Teachers Union struggled as political repression took its toll, feminism subsided, and the labor movement collapsed. When Rodman died of brain cancer at forty-five in 1923, obituaries conveyed her dedication to her black students, among other virtues.Footnote 149 However, her death came shortly after the Teachers Council branded her and the Teachers Union “un-American” for their refusal to testify before the Lusk Committee, instrument of the Red Scare.Footnote 150 The AFT relocated the American Teacher to Washington, where, no longer edited by Linville, it became a conventional union organ. Linville's suffragist wife, Adele Miln Linville, died of breast cancer not long before Rodman, and it is possible that their deaths combined with feminism's fading to unmoor Linville from gender radicalism and contribute to male dominance in the Teachers Union, just as communist maneuvering in the 1930s left Linville embittered.Footnote 151 Nevertheless Local 5 survived as the largest AFT local and was extraordinary in the 1920s for advocating a single salary schedule for all teachers, from primary to secondary school.Footnote 152 Linville continued to criticize the educational system for its “oligarchy” and “petty tyranny,” including arbitrariness in hirings, dismissals, ratings, and promotions.Footnote 153

Perhaps the Teachers Union's greatest accomplishment in the 1920s, given the times, was simply to survive. The Teachers Union did not achieve its primary initial aim of self-governance within a new school system, but it left a lasting legacy in the AFT's endurance. Despite fissures, teacher unionism endured until the first New York City teachers’ strikes in 1959–1962 produced collective bargaining.Footnote 154 In a sense, those walkouts represented an extension of early New York City teacher unionism's challenge of managerial rule. “An Appeal for a Teacher's Union,” issued in 1916, held, “A democratic community has no use for teachers afraid of their shadows, afraid of their Principals, of their Superintendents, of Boards of Education; afraid to criticize the existing order, afraid of reforms.”Footnote 155

Board representation, maternity leave, freedom of speech, ratings, and pensions: these are the issues that generated New York City teacher unionism between 1912 and 1916. Pay and job security were factors; the Teachers Union, supported by organized labor, helped wrest a 40 percent salary increase in 1919 to correct for salary erosion under wartime inflation.Footnote 156 Compensation, however, remained inextricable from power and self-governance. The centrality of radical democracy to the formation of the Teachers Union explains both why Linville was still viewed as a “dangerous agitator” by school authorities in the 1920s and why he rejected the Communist Party (which labeled him conservative) for its top-down structure.Footnote 157

While the founders of New York City teacher unionism were extraordinary in their thoroughgoing egalitarianism, their democratic idealism did not make them outliers. Democracy was arguably the theme of Progressive Era social reform.Footnote 158 Within the labor movement, many workers demanded industrial democracy, workers’ control, and freedom of speech.Footnote 159 Within teacher unionism specifically these were themes, which explains why Marjorie Murphy ascribes its Chicago genesis to resistance to centralization and describes the early AFT as “an organization of rank-and-file teachers opposed to administrative hierarchy and close supervision.”Footnote 160 That the democratic radicalism and social unionism that built New York City teacher unionism lost out by the middle of the twentieth century to bureaucratic consolidation and business unionism did not prevent similar visions of teacher power from resurfacing episodically. Even today, teachers can be found imagining, as does Chicago rank-and-filer Mueze Bawany, a public school “that doesn't have a principal…. It's teacher-led, teacher-run. I think that's where we're heading towards.”Footnote 161