CLINICIAN'S CAPSULE

What is known about the topic?

Expedient electrocardiogram (ECG) identification of ST-elevation myocardial infarction in patients with chest pain improves outcomes.

What did this study ask?

This systematic review assessed emergency department (ED) interventions that lead to improvements in door-to-ECG times for adult chest pain patients.

What did this study find?

This study found that having a dedicated ECG technician, providing triage education, and improved triage disposition procedures bundled together improved times.

Why does this study matter to clinicians?

Because many EDs do not obtain door-to-ECG within the 10-minute target, this study informs how to optimize door-to-ECG processes.

INTRODUCTION

Chest pain represents the second most common presentation to Canadian emergency departments (EDs),1 accounting for over 5 million presentations to EDs in the United States.Reference Bhuiya, Pitt and McCaig2 Expedient identification of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in patients with chest pain is crucial to reduce morbidity and mortality. The diagnosis of STEMI is made by obtaining an electrocardiogram (ECG) and as such, the timely acquisition of an ECG can lead to a prompt diagnosis. The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends that, “a 12-lead ECG should be performed and presented to an experienced emergency physician within 10 minutes of ED arrival for all patients with chest discomfort (or anginal equivalent) or other symptoms suggestive of STEMI.”Reference Anderson, Adams and Antman3

An analysis of over 7,500 patients from a tracking registry in the United States and Canada demonstrated that only 40% of STEMI patients received an ECG within 10 minutes (median time 14 minutes) and that a door-to-ECG time greater than 10 minutes was associated with increased risk of recurrent myocardial infarction or death (odds ratio 3.95, 95% confidence interval, 1.06–14.72, p = 0.04).Reference Diercks, Kirk and Lindsell4 Increased door-to-ECG times are associated with increased door-to-balloon times for primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)Reference Shavelle, Chen and Matthews5 and door-to-needle times for fibrinolysis.Reference Atzema, Austin, Tu and Schull6 Bradley et al. shows that delaying PCI, from the AHA recommendation of less than 90 minutes to greater than 150 minutes, showed an increased mortality rate of 4.4%.Reference Bradley, Herrin and Wang7

This systematic review attempts to identify ED interventions that lead to improvement in door-to-ECG times compared with institution's baseline, for adults presenting with symptoms suggestive of acute coronary syndrome.

METHODS

Protocol

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for systematic reviews.

Eligibility criteria

We included studies that involved adults (18 years of age or older) presenting to an ED with symptoms suggestive of acute coronary syndrome (P), where any identifiable intervention (I) led to a reduction in door-to-ECG time (O) when compared with the institution's baseline (C). The inclusion criteria consisted of studies in adult EDs, an ED intervention(s), and an identifiable method to reduce door-to-ECG times. We included randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, and quality improvement projects. We excluded non-English publications, conference proceedings, and abstracts and studies without both pre-intervention and post-intervention door-to-ECG times reported. An increasing amount of STEMI care is done through emergency medical services interventions (e.g., STEMI by-pass), but prehospital interventions were excluded to focus on ED interventions. Our review was not limited to prospective studies and there were no geographic restrictions.

Data sources

Two medical librarians conducted a comprehensive search using Medline, Embase, CINAHL, and Cochrane CENTRAL from inception to April 28, 2018. The search strategy is included in Appendix A. Reference selection and housing were managed using Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia). This software organized the citations and removed duplicates.

Study screening and selection

The primary outcome, inclusion criteria, and exclusion criteria were defined a priori. Two investigators (SC, DE) independently assessed all abstracts for eligibility. Discrepancies were flagged in Covidence, and eligibility was resolved by consensus. All included abstracts were then reviewed as full articles by a single investigator (SC), which compared with a representative sample of 60% of studies completed by a second reviewer (DE). The studies that conformed to inclusion and exclusion criteria based on a full-text review were included in the final analysis.

Data extraction

Two authors (SC, DE) independently extracted data of included studies on a predesigned data collection, Microsoft Excel form. The following general information was abstracted: last name of the first author, publication journal, publication year, study country, study design, sample size, ED characteristics, and study inclusion criteria. For the primary outcome, intervention type(s), primary outcome(s), pre-intervention times, post-intervention times, change in door-to-ECG times and statistical significance were collected. Any other outcomes and possible confounders, such as other significant changes at the study sites at the time of interventions, were noted. Attempts were made to contact primary authors where additional data were required. Abstracts were excluded if no data could be obtained.

Quality analysis

All included publications were quality improvement studies and were analysed for quality following the Quality Improvement Minimum Quality Criteria Set critical appraisal tool for quality improvement studies.Reference Hempel, Shekelle and Liu8 Quality analysis was completed by a single investigator (SC) for all included studies and was compared with a representative sample of articles completed by a second investigator (EK). This sample was identified by arranging the articles in alphabetical order, then using a random number generator until 25% of articles were selected for comparison. No discrepancies were identified between reviewers.

Data synthesis

The primary outcome of interest was the absolute reduction in median door-to-ECG times as calculated by the difference between the post-intervention time and pre-intervention time. Where studies used mean door-to-ECG times as their primary outcome, we reported their median times wherever possible, given skewed distributions of door-to-ECG times. Each study implemented a collection of interventions, often as bundled interventions. These data were therefore not appropriate for combining for meta-analysis. The data are presented as the pre-intervention door-to-ECG time, post-intervention door-to-ECG time, absolute difference between the two, and statistical significance (p < 0.05).

RESULTS

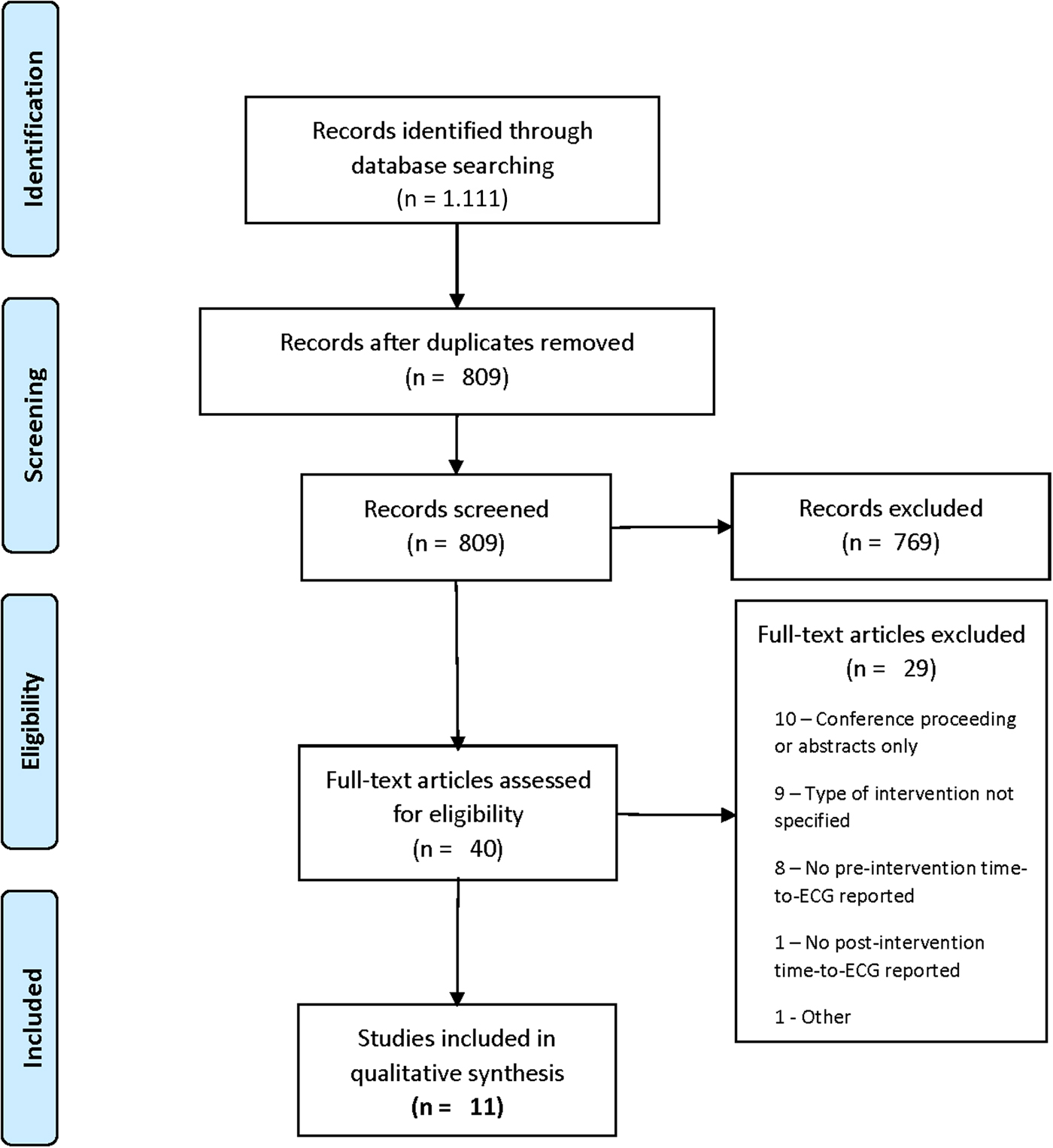

The results of the screening process are shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). The comprehensive search strategy of the Medline (343), Embase (597), CINAHL (149), and Cochrane CENTRAL (222) yielded 1,111 articles, providing 809 unique articles; 11 articles were included in the qualitative synthesis (kappa = 1.0). The reasons for exclusion are included on the PRISMA flow diagram.

Figure 1. Flow diagram.

Study demographics

The majority of interventions occurred in large, urban EDsReference Coyne and Bio9 with an international representation from the United States,Reference Atzema, Austin, Tu and Schull6 Canada,Reference Bhuiya, Pitt and McCaig2 Colombia, Saudi Arabia, and Taiwan. The median sample size was 225 (range: 72–11,518). All 11 were quality improvement studies with a before-after intervention study design.

Interventions

Each study describes a bundled approach to interventions. The most commonly reported interventions are grouped together and summarized in Table 1 in alphabetical order.

Table 1. Study characteristics and interventions by domain

Dedicated ECG technician and machine in triage

The most commonly reported intervention was a dedicated mechanism in triage for ECG completion. Five studies implemented this strategy, often as a bundled approach with other interventions.

1) CoyneReference Coyne and Bio9 moved the ECG technician and machine to triage and created a “Cardiac Triage” designation, which will be discussed later. They report a pre- and post-intervention time of 23 minutes and 14 minutes (p < 0.01; 10/16 quality domains) and comment that this continued to decrease beyond the study period, suggesting sustainability.

2) KailaReference Kaila, Bhagirath and Kass10 introduced a dedicated ECG machine in the ED and provided feedback on the previous year's data to emergency staff. Despite these interventions, they were unable to demonstrate a statistically significant reduction in door-to-ECG times. They report a pre- and post-intervention time of 22 minutes and 10 minutes (p = 0.07; 9/16 quality domains).

3) PiggottReference Piggott, Weldon, Strome and Chochinov11 relocated the ECG technician and ECG machine to triage from within the hospital. They created a dedicated ECG room equipped with two stretchers and relocated chairs, electrical outlets, and IV pumps. They report a pre- and post-intervention time of 53 minutes and 11 minutes (p < 0.0001; 14/16 quality domains). They reported continued adherence to the interventions nearly a year after the study, suggesting sustainability.

4) Sprockel'sReference Sprockel, Tovar Diaz and Omaña Orduz12 sole intervention was the permanent availability of an ECG machine in triage because their centre lacked an exclusive technician and machine for the ED. They report a pre- and post-intervention time of 26 minutes and 5 minutes (p < 0.001; 8/16 quality domains).

5) TakakuwaReference Takakuwa, Burek, Estepa and Shofer13 used a dedicated ED ECG technician that was pageable from triage. A “quick registration” was completed by registration staff, while an overhead page or direct call was placed to a dedicated technician, who would then complete the ECG in triage. They report a pre- and post-intervention time of 16 minutes and 9 minutes (p < 0.0001; 9/16 quality domains).

Triage education

The next most commonly reported category of interventions involved improved education for triage personnel in recognizing the signs and symptoms of acute coronary syndrome.

1) Keats’Reference Keats, Moran and Rothwell14 multicentre study implemented a bundle of interventions. “Triage education” interventions included training triage nurses to expedite ECGs if there are concerns for acute coronary syndrome and teaching them to perform ECGs themselves. This was done in conjunction with a series of personnel and information technology interventions that are described in Table 1. They report a pre- and post-intervention time of 6.6 minutes and 4.4 minutes (p < 0.001; 12/16 quality domains). They measure and report increased compliance to interventions after the study period and comment that their efforts were sustainable.

2) MeilsReference Meils, Kaleta and Mueller15 first created an ED algorithm to minimize “critical areas of delay,” but there is no description of the baseline process to understand the changes. Next, they improved staff education focusing on atypical patterns of presentation (e.g., shortness of breath, syncope, weakness, falls, presentations in women and minorities). They report a pre- and post-intervention time of 28 minutes and 11 minutes (p < 0.005; 7/16 quality domains), though it is not possible to determine the timing of the rollout of the interventions with respect to when the data were calculated. The group continued to measure sustained decreased times beyond the study period.

3) PhelanReference Phelan, Glauser and Smith16 educated nurses and paramedics to recognize signs and symptoms of acute coronary syndrome. They disseminated laminated cards attached to employee identification badges and posters that reinforced the education tools. In addition, they changed their process to obtain ECGs before registration, assigned paramedics rather than nonclinical personnel to triage, and data-feedback for times that fell outside of the 10-minute goal. They report a mean pre- and post-intervention time of 21.3 minutes and 9.5 minutes (p < 0.033); 11/16 quality domains) and that these times were sustained beyond the study period. There was no median time reported.

4) Takakuwa,Reference Takakuwa, Burek, Estepa and Shofer13 in addition to the interventions described previously, trained registration clerks to ask about symptoms that could be acute coronary syndrome related (e.g., weakness, shortness of breath, epigastric pain). A “quick-registration” of only name and birth was completed, and an ECG technician was paged to complete the ECG. They report a pre- and post-intervention time of 16 minutes and 9 minutes (p < 0.0001; 9/16 quality domains).

Improved triage disposition

Two studies reported modifications to the way that patients with symptoms suggestive of acute coronary syndrome were triaged.

1) CoyneReference Coyne and Bio9 implemented a “cardiac triage” designation in addition to “emergent” or “urgent,” which prioritized patients with chest pain, shortness of breath, or anginal equivalent. This was done concurrently with moving the ECG technician and machine to the triage area. The “cardiac triage” patients received an immediate ECG in the triage area, rather than being queued for expedited assessment in a patient-care area. They report a pre- and post-intervention time of 23 minutes and 14 minutes (p < 0.01; 10/16 quality domains).

2) HigginsReference Higgins, Lambrew and Hunt17 modified the triage protocol for patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of acute coronary syndrome. The pre-intervention process assigned patients to one of five triage categories (1 – immediate; 2 – within 15 minutes; 3 – within 1 hour; 4 – within 4 hours; 5 – no limit). The intervention assigned patients to one of the triage categories but then moved all patients who were over 30 years old with non-traumatic chest pain to a patient care area, regardless of their assigned category. Here, an ECG was ordered immediately, and standard nursing evaluation and management occurred. All patients were expected to be evaluated by medical staff within 15 minutes. They report a pre- and post-intervention time of 21 minutes and 16 minutes (p < 0.01; 6/16 quality domains). They continued to see improvements, suggesting sustainability.

Data feedback

Two studies reported a mechanism to provide ED personnel with feedback regarding door-to-ECG times.

1) LinReference Lin, Hsu, Wu, Liau, Chang, Liu, Huang, Ho, Weng and Ko18 prospectively assessed the impact of data feedback on door-to-ECG and door-to-balloon times. Times were recorded and were mailed to the involved staff, which included the ED physician and ED nurse. They report a pre- and post-intervention time of 11 minutes and 3 minutes (p < 0.001; 8/16 quality domains).

2) Phelan,Reference Phelan, Glauser and Smith16 in addition to the previous triage education strategies, monitored times for all STEMI patients and provided feedback when door-to-ECG times were >10 minutes. This is in addition to the other strategies described previously. They report a mean pre- and post-intervention time of 21.3 minutes and 9.5 minutes (p < 0.033); 11/16 quality domains). There was no median time reported.

Others

The aforementioned domains represent the most commonly reported categories of interventions. Other interventions are identified in Table 1 and are reported by a single investigation. These include the following:

1) Keats,Reference Keats, Moran and Rothwell14 in addition to the previous triage education, modified their patient registration process to include a nurse at the reception desk, and they created information displays asking chest pain patients to alert the nurse. They ensured that a sufficient proportion of their triage nurses were female, trained technicians to rapidly perform ECGs, and ensured that their technical issues were resolved promptly.

2) Phelan,Reference Phelan, Glauser and Smith16 in addition to triage education and data feedback described previously, had patients with chest pain obtain an ECG before registration. Additionally, they had both paramedics and nurses performing ECGs.

3) Purim-Shem-TovReference Purim-Shem-Tov, Rumoro, Veloso and Zettinger19 focused on a single intervention of having a greeter trained in performing ECG stationed in the triage area. The greeter screened all patients for symptoms concerning acute coronary syndrome.

4) Takakuwa,Reference Takakuwa, Burek, Estepa and Shofer13 in addition to triage education and having a dedicated ECG machine/technician in triage, modified the process for obtaining the ECG technician. There was a specific technician ascribed to triage who could be called or paged overhead, who would then proceed to triage. Furthermore, they eliminated the need for reassessments by the triage nurse.

Quality appraisal

All 11 articles were quality improvement studies. The Quality Improvement Minimum Quality Criteria Set tool contains 16 domains that are most informative for quality improvement assessment and application. Quality assessment is summarized in Table 2, indicating how many quality domains have been achieved out of 16. The median and mean quality score is 9/16 with a range of 6–14, indicating moderate- to high-quality quality improvement studies.

Table 2. Quality Improvement Minimum Quality Criteria Set quality appraisal

DISCUSSION

This systematic review is a comprehensive search of four databases for studies describing ED strategies to reduce door-to-ECG times. We identified 11 relevant articles totaling 15,622 patients. All are quality improvement studies with moderate to high degree of quality as assessed by the Quality Improvement Minimum Quality Criteria Set. The included articles are published in an international representation of journals and include strategies that have been reported from community hospitals to tertiary academic centres, increasing the generalizability of the results. The bundled approach to interventions precluded the ability to complete a meta-analysis.

Our review demonstrated that the most commonly reported improvement strategy (5 of 11 studies) involved modifying the triage space to allow for a dedicated ECG technician, with significant improvement in 4 of those 5 studies. The second most reported strategy was improving triage education around signs and symptoms beyond chest pain that are concerning for acute coronary syndrome, such as anginal equivalents of shortness of breath, syncope, weakness, and epigastric pain (4 of 11 studies), with significant findings in all 4 studies. PiggottReference Piggott, Weldon, Strome and Chochinov11 showed the largest absolute reduction in median time of 42 minutes (p < 0.001) and was the highest quality paper reporting 14/16 quality domains. They, along with four other studies, specified a quality improvement tool (process mapping or Lean methodology) to determine either the current state of the door-to-ECG process, the proposed areas for improvement, or both. It is our recommendation that a quality improvement tool such as process mapping be the first step in understanding the institution's local practice with respect to ECG acquisition. This will enable groups to understand which of the published interventions may have the greatest impact on current processes.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review that attempts to summarize the literature for improvement strategies, offering any size institution an opportunity to refer to a series of approaches that may improve their local metric. Only one study by KaliaReference Kaila, Bhagirath and Kass10 failed to achieve a significant reduction in door-to-ECG times. The primary goal of their study was decreasing reperfusion times, with door-to-ECG times representing only one of many steps within the process they studied, and this may represent a sufficiently different study from the others. Despite statistically significant reductions, some groups are still unable to achieve the AHA target of < 10 minutes. Moreover, there is variation in absolute and relative reduction of door-to-ECG times with some groups showing more drastic reductions, despite similar interventions. This likely represents the difficulty with bundled interventions, where it is not possible to know which intervention was most significant. Our review, however, does offer a series of measures that can be trialed based on institutional need.

The search strategy for this comprehensive review was developed with two medical librarians and searched from inception of four prominent databases. This review includes studies from multiple countries and is unlikely to miss any studies from peer-reviewed journals. Limitations include being unable to strongly conclude on the most effective interventions for door-to-ECG time reduction because the studies applied a concurrent rollout of multiple strategies. However, the significant reduction in times in nearly all studies supports the selection of these identified interventions. No studies, however, included balance measures. This limits readers from understanding the potential repercussions of adopting any measures. There were two studies where only abstracts could be found with no supporting primary author contact information. It is possible that there was new or conflicting data to arise from these studies. Moreover, our review was limited to English-language texts. However, the international representation of included articles makes this less limiting. Quality improvement research inherently has publication bias because many centres complete quality improvement work without publishing their results. It is quite possible that these interventions did not work in some centres, or other creative but unsuccessful strategies are not available for review.

Timely acquisition of an ECG for a patient presenting with symptoms suggestive of an acute coronary syndrome is crucial for the morbidity and mortality of the patient. Database reviews and institutional publications demonstrate that this benchmark is not attained during the majority of the time and can be directly implicated with increased risk of adverse clinical events. This systematic review addresses a widespread concern and provides tangible, evidence-based strategies to improve institutional metrics. The plethora of interventions indicates that there is likely no one specific strategy that is the cure for prolonged door-to-ECG times, but rather a bundled approach is important for impactful implementation. Moreover, it stresses the importance of understanding the local context in order to anticipate whether a specific intervention will be of value.

CONCLUSION

This review shows that the most commonly reported quality improvement strategies to reduce door-to-ECG times include having a dedicated ECG machine and technician at triage, improved triage education for signs and symptoms suggestive of acute coronary syndrome, improved triage disposition, and a mechanism for data feedback. Institutions need to first understand their local context through the creation of a process map to understand where their delays occur, before considering a bundle of interventions that may be most impactful in their local settings. These changes can lead to a significant reduction in door-to-ECG times in line with best practice guidelines and timely access to care.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2019.342

Author contributions

Authors SC, DE, EK, and JP were responsible for developing the research question. SC and DE were independent reviewers for both stages of screening. SC and EK were responsible for quality analysis. All authors contributed to critical revision and approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Authors thank Alexandra Davis for her involvement in the development of the search strategy, as well as Lisa Schorr for her peer review of electronic search strategies (press review).

Competing interests

None declared.