Introduction

In 2008, the archaeologist M.L. Smith, looking from a global perspective, pointed out that pre-modern urban areas were never fully built up.Footnote 1 She used the term empty space to describe areas created as zones in which construction was prohibited or which were the temporary and unintended result of destruction, clearance and abandonment. They might be permanently empty (like plazas) but might also be empty on a seasonal or temporary basis. These short-term empty spaces (in the order of years or decades) could be used as playing spaces, meeting grounds, squatter settlements or zones of economic value such as gardens. The issue of ‘empty’ space in Central and northern European towns has generally been overlooked due to the dominance of traditional images of the town, as an urban-architectural complex enclosed by walls and fully developed both physically and conceptually, which has existed since the Middle Ages.Footnote 2 Nevertheless, the problem of ‘empty’ space has been noticed and discussed by several authors. Important observations were made by J. Piekalski from an archaeological perspective in his book about medieval urbanization in Central Europe.Footnote 3 He emphasized that the urban fabric inside town boundaries was not created in a single action, but was developed slowly over time as vacant land was taken up for building purposes. Some of those undeveloped areas stayed empty for a long time. Such empty spaces could be found between older urban cores in polycentric towns or on the peripheries of built-up areas around the market square and main streets in planned chartered towns. Case-studies of peripheral intramural areas in Freiburg im Breisgau (Germany) and Bern (Switzerland) were provided by A. Baeriswyl.Footnote 4 He noticed that peripheral areas were built up a few decades after the towns were established, while before that they belonged to communes or were used as private gardens. The reverse process, of urban decline, was described M. UntermannFootnote 5 who emphasized that archaeologists do not concentrate enough on evidence of decline, which results in a lack of data for further analysis. He provided several examples of how a town could shrink and change functions of land by recreating urban layout or changing terrain into gardens. The issue of urban decline and contracting urban space in English towns was addressed in the volume Towns in Decline AD 100–1600, in which G. Astill drew attention to the importance of tracing abandonment in a larger spatial context, not limited to a single plot,Footnote 6 while K.D. Lilley proposed tracking deserted land through urban morphology analysis. He also established why certain parts of towns became vacant, showing that it was not always a result of decline but of changes in the social and economic composition of urban centres.Footnote 7

In the light of this research, we identified a gap in the common understanding of medieval urban space – the un-built areas. We call these types of space ‘empty’ to stress the contrast between them and the densely built-up zones of a medieval town. As these places were mostly peripheral, negligible and difficult to trace, they have not been studied as a separate research problem, which makes them ‘empty’ also in terms of their historiographical treatment. They are, however, important for understanding the dynamic of changes and contemporary perceptions of urban space. In our survey, we introduce three categories of ‘empty’ space found inside towns’ physical boundaries: (1) emptiness (places without any traces of permanent utilization), (2) deserted/abandoned spaces and (3) green spaces (areas covered with utility crops, such as gardens, fields, vineyards, etc.). We aim first to establish how the three categories of ‘empty’ space can be traced through an interdisciplinary approach based on combining different categories of historical sources (material, written, pictorial), second to discuss the applicability of such an approach, third to discuss how the issue of ‘empty’ space should be addressed in urban studies and fourth how addressing it can change our view of medieval urban space.

Chronological and geographical scope

In order to achieve these aims and demonstrate the ubiquity of the phenomenon, we used examples from a period between the thirteenth and seventeenth centuries, studying towns of various sizes, in different locations and displaying varying degrees of urban culture from a region of Central Europe including today's Germany, Poland and Czechia. Medieval urban centres in this region shared a common legal and spatial model, which emerged in the Holy Roman Empire and was subsequently transferred to the east to the kingdom of Bohemia, Pomerania, Silesia, Poland, Hungary and beyond.Footnote 8 Their spatial organization was characterized by an urban layout divided into regular plots, which were grouped in blocks, with central market spaces and physical town boundaries, whether it was the regular urban grid of a Lokationsstadt or the more asymmetrical structure found in older towns. Most of those towns developed in similar ecological conditions in a temperate climate, meaning that their interaction with the environment in terms of water supply, waste disposal, protection from weather conditions and access to resources would have been similar. Both the spatial layout and the environmental conditions would have been comparable, regardless of the size of the settlement, which means that the proposed method of studying ‘empty’ space can also be applied to smaller towns with a lower level of urbanization and a less-developed legal culture. We have also drawn additional examples from western and northern Europe. The extended chronological perspective is dictated by the long duration of spatial structures of medieval towns. Unlike Smith, we do not consider spaces like squares or streets, because although technically ‘empty’, they were planned as deliberate and permanent features of a town.

Methods and sources

‘Empty’ space is an immanent, albeit elusive, part of the urban structure, which can be reconstructed using material, written, pictorial and cartographic sources, and by employing archaeological methodologies (including auxiliary disciplines such as archaeobotany and geoarchaeology), history and combined approaches such as urban morphology. The following section will characterize each method, and its advantages and disadvantages in reconstructing the urban structure.

Archaeology

Archaeology studies urban space through analysis of chronology and functions of material remains. The crucial issue is the precise reconstruction of a chronology. The relative chronology of a site is established from the stratigraphic relations between archaeological contexts (stratigraphic units) i.e. layers and structures.Footnote 9 It can be developed into an absolute chronology by analysing chronological markers found in layers (e.g. coins providing a terminus post quem for the formation of a particular archaeological context)Footnote 10 or by dendrochronological or radiocarbon dating.Footnote 11 However, archaeologists often date stratigraphic units on the basis of a chronology derived from artefacts (pottery, stove tiles or small finds such as pieces of clothing, etc.) established during previous studies. Because of its near ubiquitous presence, pottery is most widely used. As its chronology is never very accurate, it gives information about the long time intervals in which it was used rather than specific dates.Footnote 12 The chronology of an archaeological site might vary therefore from a very accurate sequence of changes to a broad idea about when things happened. Nevertheless, it is crucial for establishing how long a studied area was deserted or undeveloped. A functional reconstruction of urban space is based on tracing remaining constructions, analysing portable material culture found in their context, finding analogies from previous research and ethnography and performing specialist laboratory analysis (e.g. of slags in case of furnaces, craft by-products, etc.). The absence of any indication of activity in archaeological layers might suggest the presence of ‘empty’ space, but it is not conclusive evidence. Finding traces of agriculture and horticulture is important in identifying green spaces, which can be done by applying geoarchaeological and paleoenvironmental techniques to study the composition and structure of soil.Footnote 13 Such microscopic analyses may completely change the understanding of stratigraphic sequences, and, therefore, the interpretation of urbanization processes. Unfortunately, they are rather rarely employed in urban excavations.

Urban written sources and topographical reconstruction

The majority of written sources used to study urban space were produced for or by municipal authorities. Their character and content depended on the administrative structure and organization of the town, which varied depending on time, location and the size of the town in question. Usually, the larger the town, the bigger and more specialized its administration was, and the spheres of urban life that it documented were more diverse. Over time, urban archives (kept by civic officials) gathered various types of acts and deeds (charters, privileges, correspondence with other centres and central government), court and administrative records (criminal, trade and property transactions, tax, building and development surveyors’ registers, accounts, wills, testaments and inventories, financial bills, ordinances, etc.).Footnote 14 Urban charters, registers of real-estate transactions, tax rolls and building surveys are especially useful for reconstructing urban space. With the exception of charters, they mostly consisted of short, formulaic notes written in Latin or vernacular languages.

Most information about urban space found in municipal sources concerns single plots – the basic unit of both a town's spatial structure and its governing and taxation systems. Establishing whether recorded plots were built up, undeveloped, abandoned or derelict might be crucial for distinguishing between the three categories of ‘empty’ space. Therefore, it is necessary to identify the usage of the words commonly employed to describe urban plots. Analysis of this terminology shows the limited potential of written evidence, as the terms used had multiple meanings and were applied differently depending on a location, time, local administrative traditions and even an individual clerk's education and proficiency in Latin and vernacular languages. A plot might be described with one of the following nouns: curia, area, hereditas, domus, terra, fundus, hof, erbe. Footnote 15 Town charters, products of non-urban chanceries, written mainly in Latin most often used curia to mark plots given to burghers as a dwelling, ownership of which was associated with the possession of urban citizenship and was dependent upon the payment of annual rent. The term, therefore, encompassed a measured plot ready for development with all the buildings to be constructed on it in the future and all the burdens and privileges associated with it. In Bohemia area was used with the same meaning and in the same context as curia. Although the word curia was generally employed to denote a measured plot ready for development, in the same records it could also be used to denote a palace, a mansion or another kind of property belonging to noblemen or clergy, in or outside a town.Footnote 16 Sometimes, especially in German towns, it also indicated a town hall (praetorium, Rathaus) or a royal, ducal palace. Nonetheless, it was used to mark space, which was, or at least should have been, built up. Vernacular terms used in urban records in much the same context as curia were hof and erbe. They both described a plot, which was the hereditary dwelling of burghers (connected with possessing urban citizenship). The first word is an exact German translation of curia, with all the variant meanings of the Latin one. The latter term literally means ‘inheritance’ (lt: hereditas). In Wrocław it was used in records of real-estate transactions. A plot referred to as an erbe was the basic unit in land exchange as it marked hereditary rights to a piece of land. It could also be leased to someone for building a house (hus, heus) – in that situation, the land and the house belonged to different owners.Footnote 17 The erbe was also the basic unit in tax rolls of other Silesian urban centres. However, in land transaction records of Silesian towns the erbe was rarely applied; instead, the term hus (heus) – meaning a house – was much more common and was used to describe the whole property – both land and buildings together.Footnote 18 The same practice was widespread in the administrative records of Polish towns. There, the Latin word domus (house) often marked a built-up plot in real-estate transactions, encompassing both land and buildings.Footnote 19 The Latin term area (synonyms terra, fundus) was the most universal and had the broadest meaning.Footnote 20 In all the regions of this study, it denoted a dwelling plot, although it could be used to mark both a measured building plot and one which was already built up.Footnote 21 In the records of the small town of Kamionka (Poland), clerks described built-up dwelling plots with the term domus, while generally reserving the word area for those which were empty or deserted.Footnote 22 However, there were inconsistencies in usage. In one note, the same plot was named first as area and in the next sentence as domus. Footnote 23 In the urban registers of Old Warsaw (Poland), its clerk used predominantly the term domus when the object of a property transaction was a built-up plot. Nevertheless, sometimes this clerk described the same type of property with the phrase domus et area (a house and a plot).Footnote 24 In a few cases, he also employed the phrase area cum edificiis (a plot with buildings on it),Footnote 25 which probably meant that there were buildings other than a house on this particular plot. Therefore, these terms are useful in identifying actual empty areas only when some descriptive words were added, for example phrases such as area vacua, area vacans (an empty plot) seem to indicate plots with no buildings.

Because of the variations in the terminology and its usage, it is not feasible to identify ‘empty’ space in towns without thorough analysis of the context and more importantly different types of evidence. The written sources can provide a starting point and help to identify areas of particular interest, which should then be compared and examined using archaeological data and techniques.

Pictorial sources

Pictorial sources, especially post-medieval town views, provide direct information about a town's topography, the shape and form of buildings, the road networks, etc. The first realistic views and plans of towns started to appear in late medieval Italy.Footnote 26 The sixteenth century brought the introduction of the bird's-eye view, which depicted towns in a form something between a plan and a profile. Presenting distinctive spatial and material features of individual sites, these new images reveal a complex urban system of infill buildings, monuments, squares, roads, walls and various landscape features.Footnote 27 Although renaissance depictions were often quite realistic, it is vital to remember that sometimes their authors intended to idealize or allegorize the represented world. Streets and squares shown on town views were often cleared of people, and shapes of buildings were changed to form a better composition.Footnote 28 Town views might also have been instruments of propaganda sponsored by governments or commercial ventures, designed to present an urban centre in a particular way.Footnote 29 Moreover, it is difficult to use them for tracing changes in a specific urban space as engraved plates were often re-used for years and old views became a source for new pictures.Footnote 30

Among the landscape features that were commonly depicted were gardens, fields and unbuilt-up areas, etc., which might provide evidence of existing ‘empty’ space or indicate where it might have occurred. Moreover, they also provide clues about how urban space was perceived at the time, suggesting that contemporaries did not necessarily view towns as homogeneous densely built-up areas.

Urban morphology

Urban morphology is a research method that identifies different types of urban landscapes through study of their morphological characteristics, formation and transformation of urban fabric and spatial patterns.Footnote 31 It combines fieldwork and map analyses. Maps made by professional surveyors in the nineteenth century are one of the principal sources, as they were the first accurate plans to register structures existing before the changes of the industrial revolution and the twentieth century.Footnote 32 The method, as Lilley summarized it,Footnote 33 consists of four stages. The first is preparation of a town plan derived from the earliest most accurate map. The second stage is the process of plan analysis which involves defining ‘plan units’: plots and streets that share similar morphological character (size, shape, etc.). These units are the basis for further analysis of historical evidence. In the third stage, the historical material (archaeological structures, urban tax registers, etc.) is integrated into the town plan and is used to provide a relative chronology of topographical features. In stage four, the individual plan units and their morphological histories are all pieced together to create a map of the changing urban landscape. Retrospective analysis of available town plans (although these are not always accurate) can be applied to help establish the chronology of the changes.

In the case of ‘empty’ space, urban morphology can help with tracing areas that were unoccupied (or covered with vegetation) for a long time and which continued to be visible much later in the urban layout. In contrast to densely built-up centres with regular narrow plots, what was once ‘empty’ space manifests itself on modern plans as areas with different street patterns, not necessarily regular, with larger buildings, but also as land covered with vegetation, gardens and wastelands.

Emptiness

The first type of ‘empty’ space is emptiness: terrains that had never been built up and for which there is no indication of any permanent human activity. This kind of ‘empty’ space was ephemeral and could quickly disappear, which makes it difficult to trace. We assume that the emptiness was created when a new town was founded in order to ensure a reserve of building land for future development. It can be identified through a large-scale urban morphology analysis and on a smaller scale through circumstantial evidence.

Empty areas as building reserves

Piekalski assumed that empty areas occurred on the peripheries of built-up zones and were treated as building reserves. Their existence has been observed in Central European chartered towns, which were often founded on uninhabited land. The nucleus of these towns, its communal and commercial centre, was a market square (German Ring).Footnote 34 According to the accepted model of urban development,Footnote 35 the market square was the first delimited element of a new regular urban layout, around which the first burghers settled, while subsequent newcomers occupied main and later side streets. Since the creation of a new town required a border to be established separating the town's area from outside,Footnote 36 this was probably done at an early stage.Footnote 37 As the town gradually developed (assuming that not all the plots inside the boundaries were inhabited when it was chartered), all unoccupied areas could be considered as empty. To establish their extent and the dynamics of urban development, it is necessary to trace the chronology of the oldest artefacts and structures in an urban area.

The gradual development of an urban layout is visible in Wrocław (Poland). On a cadastral plan of the city made in 1902–12,Footnote 38 we can distinguish differences in the structure of the medieval parts of the town. The inner city, around the market square, consists of densely built-up city blocks varying slightly in shape. The area on the peripheries (close to the external fortifications) is characterized by larger blocks with a looser structure. The view from 1572 depicts similar differences in the urban plan (Figure 1). M. Chorowska studied the process that led to these differences,Footnote 39 using archaeological data and metrological and architectural analyses of street blocks and tenements. The town's development started at the beginning of the thirteenth century, when the communal town (German Lokationsstadt, Grundungstadt) was established with a regular layout next to the early medieval settlement.Footnote 40 The oldest houses were concentrated around the market square, which was established during the first decades of the thirteenth century. Tenements behind that first ring of plots remained empty until they were inhabited during the first half of the thirteenth century. The areas directly adjacent to the first established town border were not occupied before the second half of the century. The process was repeated again after 1261 when lands located to the south and the west of the central core were incorporated into the town by surrounding them with the second fortification line.Footnote 41 The chronology of archaeological remains discovered in that newly enclosed area indicates that its development was even slower, with some spaces remaining empty for a longer time. The oldest artefacts on particular sites are post-thirteenth century (Figure 2). The existence of ‘empty’ space for building reserves probably resulted in the different layout of the outer parts of the town, characterized by irregular urban blocks and the presence of tenements and houses with gardens in the later period.

Figure 1. Comparison of cadastral plan from 1902–12 with view from 1562 (R. Eysymontt and M. Goliński (eds.), Historical Atlas of Polish Towns, vol. IV, 13: Wrocław (Wrocław, 2017), map 2; Barthel and Georg Weihner (1562), copy of J. Partsch (1826), https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Breslau1562Weihner.jpg, accessed 26 Mar. 2020).

Figure 2. Wrocław – central urban layout from the thirteenth century and chronology of archaeological remains in the area incorporated in 1261. (a) Mikołajska 25–6 (P. Janczewski, ‘Zmiany zagospodarowania przestrzeni dawnej działki mieszczańskiej przy ul. św. Mikołaja 25–26 we Wrocławiu’, Śląskie Sprawozdania Archeologiczne, 44 (2002), 301–13); (b) – Św. Mikołaja 48 (C. Lasota, J. Piekalski and I. Wysocki, ‘Działki mieszczańskie przy ul. Św. Mikołaja 47/48 i 51/52 na Starym Mieście we Wrocławiu’, Śląskie Sprawozdania Archeologiczne, 43 (2001), 345–64); (c) – Św. Antoniego (C. Buśko and J. Piekalski, ‘Stratygrafia nawarstwień w obrębie ulicy Św. Antoniego we Wrocławiu’, Śląskie Sprawozdania Archeologiczne, 37 (1996), 243–53); (d) – Kazimierza Wielkiego 27a (C. Buśko and J. Niegoda, ‘Badania archeologiczno-architektoniczne przy ul. Kazimierza Wielkiego 27A we Wrocławiu’, Śląskie Sprawozdania Archeologiczne, 43 (2001), 577–83); (e) – Świdnicka 21/23 (L. Berduła, ‘Wyniki badań architektoniczno-archeologicznych we Wrocławiu przy ul. Świdnickiej 21/23’, Silesia Antiqua, 36/7 (1994), 77–94); (f) – Widok (J. Piekalski, ‘Z badań zewnętrznej strefy Starego Miasta we Wrocławiu, Plac Teatralny i ul. Widok’, Śląskie Sprawozdania Archeologiczne, 41 (1999), 307–24); (g) – Wierzbowa 2–4 (P. Konczewski, Działki mieszczańskie w południowo-wschodniej części średniowiecznego i wczesnonowożytnego Wrocławia (Wrocław, 2007)); (h) – Nowa 2a (J. Romanow, ‘Wyniki badań archeologiczno-architektonicznych prowadzonych w latach 1998 i 2000 na terenie posesji 2a przy ulicy Nowej we Wrocławiu’, excavations report in archive of The Voivodeship Conservator of Historical Monuments in Wrocław) (plan based on M. Chorowska, C. Lasota, T. Kastek and J. Połamarczuk, ‘Map 5 Wrocław around 1300’, in R. Eysymontt and M. Goliński (eds.), Historical Atlas of Polish Towns, vol. IV, 13: Wrocław (Wrocław, 2017), modified by authors).

Prague New Town (Czechia) developed similarly to Wrocław. Its foundation in 1346, just outside the gate of Prague Old Town, was a part of a larger programme of Emperor Charles IV, who created his capital city as a symbol of his rule and power.Footnote 42 The area for the new town was reclaimed by the emperor and partially cleared of older settlements and farmlands. A new urban layout with large market squares was created in connection with the existing road network. Its whole area (360 ha) was surrounded by a defensive wall soon after the foundation. According to architectural and morphological analyses, initial development of the town took place around those squares and main streets, leaving large parts of the enclosed urban space unoccupied.Footnote 43 In the southern part of the town, a few ecclesiastical institutions were established, receiving substantial quantities of land inside the town walls. This spatial structure seems to have been long lasting. A very accurate cadastral plan from 1842 (Imperial Stabile Cadastre), made before major changes in the urban layout,Footnote 44 depicts substantial, irregular blocks of green spaces and large buildings located mostly in peripheral zones, close to the town walls (Figure 3). The green spaces might be interpreted as gardens, some of which originated after the partial destruction of the town during the Swedish siege of 1648.Footnote 45 Others were, however, much older, being mentioned in the written records in the late Middle Ages.Footnote 46

Figure 3. Prague New Town – a fragment of the imperial cadastral plan from 1842 (Czech Office for Surveying, Mapping and Cadastre, www.cuzk.cz).

Identifying emptiness on a smaller scale

In both cases, the large-scale approach based on chronological analysis of urban development gives us only a broad idea where the un-built zone was located. However, determining the precise extent of emptiness is challenging. Pictorial sources, for example, the numerous town views of Braun and Hogenberg, depict densely built-up centres gradually merging into ‘rural’ peripheries. We cannot be certain, however, that those areas were empty. It might simply reflect contemporary conventions of representing urban space. Moreover, town views are generally late and show well-established towns, in which the initial emptiness had already been developed. Nor do written sources offer much evidence, as generally there are no fiscal or real-estate records for the initial period of towns’ functioning. To identify emptiness in an archaeological context, a very accurate chronology is necessary. As noted above, this is not always available, as the intervals of an archaeological chronology might be longer than the existence of ‘empty’ space. However, analysing some types of indirect evidence may help with its identification. Patterns of refuse disposal serve as a good example. Some refuse was disposed of where it was created (e.g. production waste), but some was removed to other places (cesspits).Footnote 47 For instance, in Esslingen (Germany), in Mühlenstrasse, archaeologists identified dumping grounds for latrine filling dated to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries in the area behind the built-up housing zone.Footnote 48 The refuse layers were partially covered with sand sediments formed by flooding,Footnote 49 which may be the reason why the area was uninhabited. In many parts of Lübeck, archaeologists recorded a layer dated to the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, which contained large amounts of refuse with no specific concentration. In subsequent strata, however, there were no comparable traces of refuse.Footnote 50 Similar observations were made in Braunschweig. Of the artefacts dated to 1065–1200, 19 per cent were discovered in latrines, 41 per cent in various types of pits and 39 per cent in settlement layers. For assemblages of artefacts from 1200 to 1350, the period of the town's intensive growth, the pattern was different: 76 per cent were found in latrines, 8 per cent in pits and 10 per cent in layers.Footnote 51 One possible interpretation is that in the period when the town was not densely built up there were no specific places for waste disposal, but later, when the urban fabric became denser and perceptions of urban space changed, new cleaning regulations were introduced.

Employing geoarchaeological and paleoenvironmental techniques can be very helpful in identifying emptiness or cultivated land and all other macroscopically invisible forms of land utilization. For example, studies conducted in Antwerp (Belgium) revealed that for a profile in which two stratigraphic units were identified during excavations, microstratigraphic analysis identified seven. These included area covered with cut grass (interior of a building?) and traces of possible pasture.Footnote 52

Deserted/abandoned spaces

Emptiness was connected with urban growth, but ‘empty’ space was also formed in the reverse process: that is, the shrinkage of built-up areas. Parts of a town could be deserted and abandoned as a result of natural disasters (e.g. fires), depopulation (due to plagues, starvation, migration or transformation of the economy) or changes in land management.

Destruction

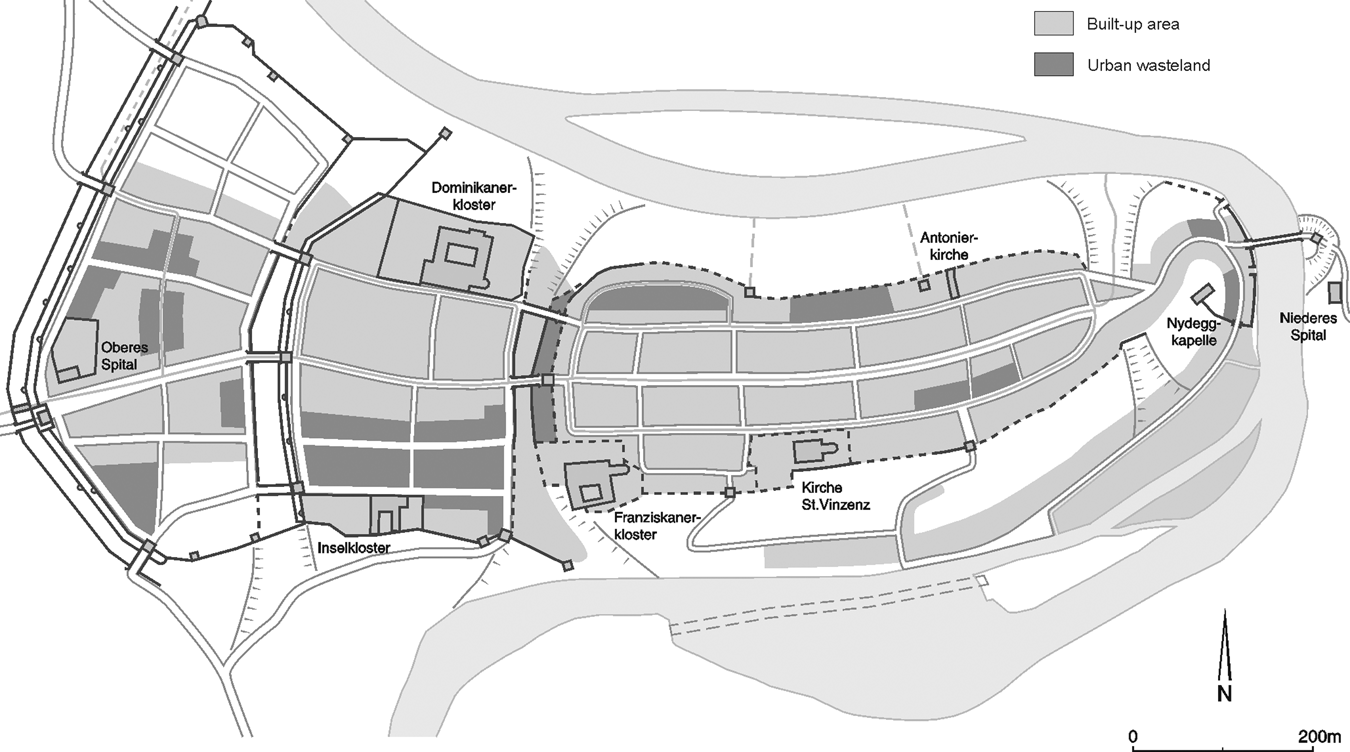

Urban fires, frequent in a pre-modern town, are visible as layers of burned residues. In the case of wooden buildings, the layers often consist of large quantities of burned construction clay (daub), pieces of carbonized wood and ash. Combusted masonry structures leave bricks that might be re-burned and deformed and stones and mortar with surfaces tinted with brown or red colour. All artefacts that were inside burning buildings display some marks of fire, like deformation in the case of pottery.Footnote 53 Such artefacts were discovered in Bern (plot Brunngasse 7/9/11). The chronology of the archaeological material suggests that the plot was unoccupied between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries.Footnote 54 It corresponds with information about the fire in 1405, which severely destroyed this part of Bern.Footnote 55 The area was not rebuilt after the fire, probably as a result of a crisis and depopulation due to the Black Death in the fourteenth century (Figure 4).Footnote 56

Figure 4. Bern – burned areas inside town walls (A. Baeriswyl, Stadt, Vorstadt und Stadterweiterung im Mittelalter. Archäologische und historische Studien zum Wachstum der drei Zähringerstädte Burgdorf, Bern und Freiburg im Breisgau (Basel, 2003), Abb. 170).

Abandonment

It is also possible to register abandonment that was unconnected with the rapid destruction of the built environment. In Offenburg (Germany), in the area adjacent to the town wall, archaeologists discovered relics of houses and accompanying infrastructure which they dated to the period from the thirteenth to the fifteenth century. At a specific point, all those buildings were demolished, leaving cellars filled with rubble. The absence of artefacts and remains from the later period suggest that the area was unoccupied until the end of the seventeenth century.Footnote 57 A similar situation occurred in Freiburg im Breisgau (Germany), where archaeologists found abandoned plots on Gauchstraße and on Grünwälderstraße. In both cases, existing buildings were torn down and cellars were filled with rubble and earth. Both places stayed abandoned until the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries.Footnote 58 Another case is Visby on Gotland. Since the fourteenth century, it had been losing its position as a major trading post, its population was declining and in the 1520s it was destroyed during the conflict for the Danish throne.Footnote 59 The abandonment is visible on a sixteenth-century view of Visby by Braun and Hogenberg, which depicts the town centre surrounded by deserted areas with some ruins (Figure 5b).

Figure 5. Fragments of the town views from Braun and Hogenberg, Civitatis orbis terranum. (a) – Cologne 1572; (b) – Visby 1598 (views from http://historic-cities.huji.ac.il, accessed 30 Jul. 2019).

Problems of inconclusive and missing evidence

The examples described above were long term and large scale. Astill pointed out, based on evidence from British towns, that decline can be observed only on a larger scale, concerning multiple plots, blocks or a neighbourhood.Footnote 60 Such large-scale shrinkage occurred only in towns affected by serious events that led to changes in space utilization. But in many places, there were various local changes, like abandonment of single plots or smaller fires. The main reason why they are difficult to trace is that the intramural space was limited and valuable. In towns not affected by an economic crisis, buildings or infrastructure that were destroyed were quickly repaired or rebuilt.Footnote 61 In Central Europe, monarchs often granted a tax-free period to towns devastated by fires or floods to facilitate restoration of the ruined urban fabric.Footnote 62 Similarly, town councils tried to keep the area within the walls fully developed by ordering owners of plots to build a house within a certain time after acquiring the land and then to maintain it properly.Footnote 63 In Wrocław, in 1506, even the bishop was ordered to rebuild his property under the threat that his plot would be repossessed by the town council.Footnote 64

Exploring the potential of written sources for evidence of small-scale shrinkage, we tried to identify words that might suggest abandonment. The phrases such as area vacua, area vacans (an empty plot), area deserta, hereditas deserta, domus deserta (deserted, empty), area desolata (deserted, empty) are particularly significant and interesting. The first two seem to be used to mark plots with no buildings. The attributive deserta (desertata), however, suggests rather a plot, which was abandoned, deserted, left without an owner.Footnote 65 It could be built up, even if only with derelict buildings. In Wrocław, hereditas deserta was used in the context of the town's expenses and losses, while listing plots with no owners, bringing in no income, so vacant in a legal, proprietary sense.Footnote 66 In the Old Warsaw urban records, the phrase manus defuncta sive desertata was used to mark an escheat to the dukes of Mazovia.Footnote 67 Councillors of Kamionka gave ‘a plot deserted for nineteen years and, hence, bringing no income’ (‘aream eam a decem novem annis desertam et ita ne censibus…devolutam et spectantam’) to a burgher with the condition that he would develop it.Footnote 68 In the last example, the plot was empty or derelict, but the word deserta was used by a clerk to signify that it was without an owner and thus bringing in no income, rather than being simply unbuilt-up. The adjective desolatus is more ambiguous as it could mean both being physically empty and without an owner.Footnote 69 The term area deserta was mentioned several times in written records from Prague New Town. Thanks to reconstruction of urban space made by V.V. Tomek,Footnote 70 it was possible to map those deserted plots (Figure 6). However, no specific distribution is observed, as they appear all over the town in different years during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. They might mark fluctuations of the urban structure, but, unfortunately, with no other type of evidence available to study them, it is only a conjecture.

Figure 6. Localization of plots described as area deserta according to reconstructions of V.V. Tomek (redraw of plan from V.V. Tomek, Mapy staré Prahy k letům 1200, 1348 a 1419 (Prague, 1892), localization based on V.V. Tomek, Základy starého místopisu Pražského II. Nové Město pražské (Prague, 1870)).

Ambiguous green spaces

The third category of ‘empty’ space is the most diverse and complex as it includes literally undeveloped areas (green wastelands) and those which were cultivated. Moreover, green spaces could be both purposefully planned elements of the urban structure and results of an impromptu or temporary utilization of available land. In the latter case, they occupied spaces pertaining to one of the other categories (emptiness or abandonment). Whatever their origin was, large unbuilt-up areas within town walls provided crops or space for temporary infrastructure (e.g. lime kilns, brickyards, sandpits) and communal activities (e.g. festivities, militia training). However, they could be easily converted into building plots. Therefore, because of their potential for development and peripheral position, both spatially and formally, they share the character of the previous categories of ‘empty’ space.

Gardens on plots

The existence of gardens in towns since their foundation is rather obvious, but unfortunately little is known about them.Footnote 71 In Central European chartered towns, burghers commonly received not only a plot but also a garden.Footnote 72 The latter was indicated in written sources by the Latin term (h)ortus or the German garten.Footnote 73 Gardens were usually located on the peripheries of the towns, but sometimes urban registers recorded them also in rear parts of dwelling plots, behind houses. Domus cum orto (a house with a garden) was a common object of registered real-estate transactions.Footnote 74 Archaeological studies of the dwelling plot organization suggested that gardens were typically found to the rear of the property.Footnote 75 This spatial structure is visible in the case of abandoned towns that existed only for a short period of time, where the remains of buildings are concentrated to the front of plots, while their posterior areas are empty, suggesting the presence of gardens.Footnote 76 With time, in developing urban centres, buildings were expanded into backyards and plots were often divided as the available building space shrank. Finally, parcels became fully built up, with no space for gardens. However, there are incidental examples of the reverse process – the transformation of a built-up space into a green one. In Freiburg, some derelict houses and developed plots were converted and used as gardens (often with added utility structures and buildings), much to the annoyance of the town council.Footnote 77

Large green spaces

Urban peripheries, especially in larger towns, were covered with vegetation, as depicted on sixteenth-century views of, for example, Aachen, Duisburg and Frankfurt am Main by Braun and Hogenberg.Footnote 78 Cologne serves as a great example. In the prospect view dated 1572, between the inner and the outer lines of fortification, there are large, irregular, urban blocks marked with a regular pattern, which represent green spaces (Figure 5a).Footnote 79 Those areas were vineyards and gardens that, according to the written records, existed in the outer part of the city from the Middle Ages up to the nineteenth century. The first survey conducted in the seventeenth century registered that they covered about 30 per cent of the intramural land.Footnote 80 Their existence was an effect of Cologne's specific urban development. That post-roman city had been extended on a small scale several times until in 1180 the town authorities decided to surround all urban areas and also three neighbouring church institutions with an 8 km long fortification line, thus expanding the town from 210 ha (in 1106) to 387 ha.Footnote 81 The decision to build such an imposing wall is considered a symbolic move in the struggle between the urban commune and the bishop of Cologne.Footnote 82 In Prague New Town, gardens and vineyards were recorded inside the town walls in the late medieval registers: for example domus cum vinea in Benatska Street,Footnote 83 area cum ortulo, ortus cum vinea close to St Catherine's church.Footnote 84 Their presence on the cadastral plan from 1842 might suggest their long-term existence, as archaeological evidence indicates their presence since the town's foundation. In several places, researchers have discovered traces of ‘garden layers’ (Figure 7): thick layers of dark soil with a small number of artefacts, mostly pottery sherds, dated to between the fourteenth and seventeenth/eighteenth centuries.Footnote 85 Significantly, there were not many remains of buildings or infrastructure. In Wrocław, we are lacking the archaeological evidence, but the fifteenth-century sources typically record gardens between the inner and the outer town walls: ‘garten an der Ole’ (1438); ‘garten mit dem hawse dorynne gelegen in dem seidenbewtel’ (1474).Footnote 86 The gardens are also visible on the town view from 1562.

Figure 7. Prague New Town - ‘garden layer’, Opatovická Street no. 160 (photo by T. Cymbalak).

Different functions of green spaces

The cultivated land inside town walls was put to a diverse use. Written sources sometimes allow us to determine its specific purpose. Grasslands, vineyards, herb gardens and orchards were identified in the seventeenth-century survey of Cologne.Footnote 87 Types of specialized gardens were also recorded, for example, a medical garden in Prague New Town.Footnote 88 Furthermore, there are examples of gardens with permanent or semi-permanent structures: ortum cum edificiis (a garden with buildings),Footnote 89 ortum cum promptuario (a garden with a granary)Footnote 90 or ortum cum brasiatorio (a garden with a maltings/malt house), which show yet another (and not obvious) use of the green spaces.Footnote 91 However, in most cases, a green space is called simply a garden (ortus, garten), with no indication of its specific function. Archaeology often provides more information about how the space was cultivated. Horticulture is visible archaeologically in marks made by spades, combined sometimes with enclosures or drainage ditches. Triangular or crescent-shaped marks in bedrock under the soil are left when a spade was dug deep into the natural soil, leaving darker remains of the original topsoil that flaked off the humus layer.Footnote 92 Such traces of triple- and double-depth digging with a spade were found at the suburb of Wrocław. The horticultural character of the layer was confirmed by geochemical analyses.Footnote 93 Discovering an empty area enclosed with drainage ditches might also suggest gardening activities. One from the thirteenth century was identified in a backyard of a plot in Greifswald's market square. It was surrounded by fences and ditches. Access was provided by wood-paved tracks and water supply by wells dug in the yard. Inside the garden, archaeologists found a pear tree.Footnote 94 Remains of plants may also help in identifying gardens and other green spaces. For example, in Neuss (Germany) remains of weeds were discovered in a latrine in the rear part of a plot. Researchers concluded that they were disposed of after garden weeding, because it would have been illogical to bring useless plants into a town.Footnote 95 As the spade marks indicate horticulture, so traces of ploughing suggest field cultivation. In Stralsund (Germany), on a plot adjacent to the town wall, archaeologists identified plough marks: long and narrow ditches filled with humus, which were dated to the 1260s–70s.Footnote 96

Summary and conclusions – why does ‘empty’ space matter?

The issue of ‘empty’ space concerns the type of urban space that defies a strict definition, because of its dynamic character and what at first glance might seem to be of marginal importance for urban inhabitants. We demonstrated that ‘empty’ space, intended, deserted and/or covered with vegetation, was a typical and inherent element of the medieval urban structure. It allowed for further town development, food production and communal activities. For researchers, it might be an indicator of major urban changes. Specifically, we state that: (1) certain peripheral areas were intentionally left empty as a land reserve when towns were first laid out and were later developed with different dynamics according to need; (2) deserted areas are visible only in cases of major population changes, smaller abandoned spaces were quickly redeveloped; (3) green spaces were an immanent feature of the urban landscape that provided food and space for temporary activities; (4) while empty and abandoned spaces are mutually exclusive categories, they could both function as green spaces.

As ‘empty’ space is by nature dynamic and ephemeral, identifying it in the urban environment requires a large spatial and chronological scope and a multidisciplinary approach. Urban morphology is the most appropriate framework for such an investigation. Combined with an examination of visual sources, it can suggest the presence of a particular category of ‘empty’ space. Ambiguous and imprecise written records have very limited potential in tracing emptiness. They are, however, more useful in tracking decline and abandonment and are probably most valuable for locating green spaces (especially gardens). Analysis of how contemporaries described the urban environment also shows how ‘empty’ space was perceived. Archaeology, often restricted by the limited scope for excavations within urban areas, is chiefly valuable in identifying long-lasting ‘empty’ space. Although new approaches, such as microstratigraphy, and auxiliary disciplines (archaeobotany and geoarchaeology), can reveal how a particular area was used and confirm the existence of green and deserted/abandoned spaces. As no single method alone proves successful, we propose here a multi-step, interdisciplinary protocol for tracing ‘empty’ space in the urban context. Research should start with analyses of iconographic and cartographic sources, as this is the easiest way to designate areas that might be considered as ‘empty’ spaces. Second, all the available written material should be studied to determine if there is any indication of gardens, abandoned buildings, empty plots, etc. The final stage should encompass an evaluation of archaeological evidence (supported by environmental methods) to establish possible breaks in occupation or traces of agricultural practices. The outcomes should then be analysed in the wider urban context to estimate how densely built up a town was and how its urban fabric changed.

The physical identification and functional analysis of ‘empty’ space is the first step for exploring it. This leads to questions concerning social, economic and ecological issues of medieval urban life. This study demonstrates that such undeveloped land, despite not being easily visible in sources, played an important role in town growth. It could be an instrument of generating and accumulating wealth in the hands of patricians and as such create a prerequisite for growing inequality and social tensions. Therefore, studying ‘empty’ space can bring new insights not only into the physical fabric of towns but also their social framework. Moreover, the ‘discovery’ of ‘empty’ space shows that the medieval town was much more heterogeneous than it is commonly thought to have been, and the patchwork structure comprising built-up and undeveloped areas provided space for interactions between the town and the wider environment.