Adolescence is increasingly recognised as a sensitive period of growth and development, during which a child’s health trajectory may be modified for long-term health benefits(Reference Patton, Sawyer and Santelli1,Reference Patton, Coffey and Cappa2) . While non-communicable diseases such as type 2 diabetes mellitus and CVD commonly emerge in adulthood, associated risk factors such as poor diet and activity behaviours, as well as obesity, are often established and/or advanced during the adolescent years(Reference Viner, Ozer and Denny3). In addition, as the next generation of parents, ensuring optimal nutritional health in adolescents (i.e. pre-conception) may be important to the health and well-being of their offspring(Reference Patton, Olsson and Skirbekk4).

In South Africa, rapid urbanisation and a transition towards diets high in saturated fat, sugar, salt, processed and convenience food products and edible oils, but low in essential micronutrients, alongside low levels of physical activity have been associated with the obesity epidemic(Reference Popkin and Gordon-Larsen5–Reference Kac and Pérez-Escamilla7). With approximately 27 % of girls and 9 % of boys either overweight or obese by 15–17 years of age, this generation is vulnerable not only to obesity and non-communicable diseases in the long term, but to propagating the intergenerational cycle of risk to their offspring(Reference Patton, Sawyer and Santelli1,Reference Patton, Olsson and Skirbekk4,8) . While current trajectories in adolescent health are a concern, the shifting health determinants and growing levels of autonomy experienced during this phase of life provide an opportunity to reshape the lifestyle habits that South Africans carry into adulthood(Reference Viner, Ozer and Denny3).

South African studies suggest that the urbanisation-associated rise in adolescent adiposity – particularly affecting girls – is partly driven by the adoption of obesogenic behaviours including irregular breakfast consumption and fewer family meals, increased snacking and consumption of purchased/fast-food products, and reduced levels of physical activity(Reference Feeley and Norris9,Reference Feeley, Musenge and Pettifor10) . In addition, qualitative data show that urban girls perceive affordability, convenience, peer influence and food item popularity to be key drivers of their dietary choices, with a lack of facilities and safety concerns influencing their ability to be physically active(Reference Sedibe, Feeley and Voorend11,Reference Voorend, Norris and Griffiths12) . However, these data fail to explore potential differences in the determinants of diet and activity behaviours between boys and girls, and between younger and older adolescents, or the role that caregivers play in influencing decision making and lifestyle behaviours across this period.

Studies from high-income countries have shown that the obesogenic behaviours of children and adolescents vary according to age and gender(Reference Leech, McNaughton and Timperio13). Specifically, older adolescent girls exhibit distinct clusters of behaviour defined by low levels of physical activity, with differences in sedentary behaviour also being evident(Reference Leech, McNaughton and Timperio13). Given the substantial differences in the overweight and obesity prevalence rates between South African girls and boys as they age, understanding what may be driving the divergence in adiposity by gender – as well as between younger and older adolescents – may be a critical component of effective, targeted future interventions. Similarly, research has highlighted the role that parents or caregivers can have in influencing diet and activity behaviours in adolescents, for example through shaping household food environments and role modelling healthy physical activity practices(Reference Anderson Steeves, Johnson and Pollard14).

The aim of the present study was therefore to: (i) understand facilitators and barriers to healthy eating practices and physical activity in younger and older urban adolescent boys and girls in South Africa; and (ii) understand how the views of caregivers interact with those of adolescents, as well as how they influence adolescent behaviours.

Methods

Setting

The present study was conducted at the South African Medical Research Council/Wits Developmental Pathways for Health Research Unit (DPHRU) at Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital in Soweto, Johannesburg. Soweto is one of the most well-known historically disadvantaged townships in South Africa, linked to the anti-apartheid struggle and political riots(Reference Ndimande15). The township covers more than 200 km2 and has a population of approximately 1·3 million(16). Economic change over the past decade has transformed the landscape of food availability and choice, largely linked to the rapid emergence of shopping malls and fast-food chains(Reference Moodley, Christofides and Norris17). The present study was a qualitative study using focus group discussions (FGD); a quantitative survey was also included to capture participants’ sociodemographic and anthropometric characteristics. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of the Witwatersrand’s Research Ethics Committee (Medical) (approval number M170680) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Participants

Recruitment

A purposive sampling method was used to recruit adolescents and their caregivers from the Diepkloof, Orlando and Mofolo areas of Soweto. Research assistants entered the communities to issue recruitment letters, which outlined the purpose and details of the study, as well as providing contact information for DPHRU. Prospective participants provided their information directly to the research assistants and/or contacted the research unit using the details provided. Additionally, in some cases, information about the study was shared between community members and those interested in participating contacted the research unit for further information. Research assistants at DPHRU collated the information on prospective participants who were then called back to make appointments. All participants were reimbursed for their transport costs and received refreshments when attending the FGD.

Selection criteria

The selection criteria for the study were specified as adolescent girls and boys aged between 10 and 12 years or 15 and 17 years. These age categories were used in order to clearly distinguish between younger and older stages of adolescence and therefore to allow comparison of diet and activity behaviours according to adolescent age. Each adolescent was accompanied by his/her caregiver; for example, parent, grandparent, aunt or uncle. Ten adolescents per age and gender group, as well as their ten caregivers, were recruited over a 5-week period to achieve a sample size of eighty. Two FGD were conducted on the same day each week, one with adolescents and another with caregivers. The adolescent FGD took place first on each day, as it was felt that the adolescents were likely to tire easily if their FGD was conducted later in the day.

Data collection

Eight FGD were conducted between 2 July and 29 July 2018 using a semi-structured FGD guide (see online supplementary material). Initial development of the guide was carried out by four researchers based on previous research and identification of gaps in knowledge around adolescent nutrition in South Africa. All authors then reviewed the guide in an iterative manner and provided suggestions on how to improve it.

The FGD were arranged by participants’ age and gender as follows: one for young boys and one for young girls (10–12 years); one for older boys and one for older girls (15–17 years); one each for the caregivers of young adolescent boys and girls, respectively; and one each for the caregivers of older adolescent boys and girls, respectively. FGD were conducted in English, with flexibility for the participants to use vernacular languages, and were audio recorded. The duration of the FGD ranged between 45 and 60 min for adolescents and 60 and 90 min for the caregivers. A facilitator conducted the FGD while an observer wrote comprehensive field notes based on observations from the FGD to supplement the audio files. After the discussions, the audio files and field notes were transcribed verbatim and translations done where necessary. All transcripts were then checked against the recordings to verify accuracy.

Data analysis

The eight transcripts were divided between four researchers who read and re-read their allocated set to familiarise themselves with the content. A combined deductive and inductive approach was used for theme identification and analysis. The deductive approach was based on pre-identified themes focusing on the research questions, while the inductive approach was undertaken for all emerging themes from the transcripts and field notes. Initial theme identification was followed by meetings of the research group to compare, contrast and discuss emerging themes, while incorporating the principles of the immersion-crystallisation method(Reference Borkan, Crabtree and Miller18). This qualitative approach consists of individual-level review of the FGD recordings and transcriptions and subsequent group discussion to determine emerging themes. Based on the identified themes, the research team developed, tested and refined a data codebook that was used for coding and analysis. A constant comparative method was used to compare between participant groups and observe similarities and differences in the emerging themes(Reference Boeije19). An independent qualitative researcher tested reliability and internal validity of the data coded from the FGD and differences were established and reported. Discrepancies were then discussed and resolved as a group to ensure that codes and text reflected the definitions generated by the team. Following coding, group meetings were held to complete data analysis and interpretation of themes until the point that no new themes emerged. Exemplar quotations were excerpted to illustrate the themes that had emerged from the discussions. Finally, data were presented in two broad categories: healthy eating and physical activity.

Results

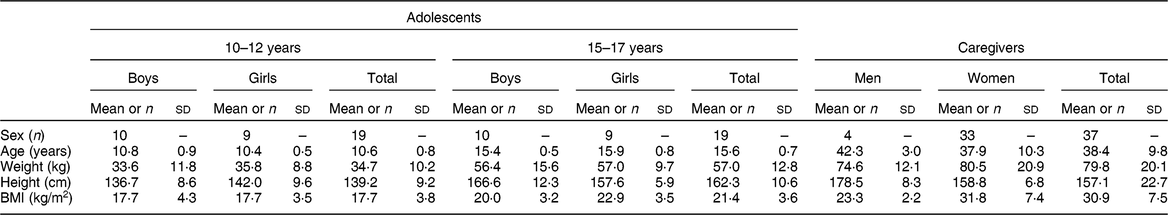

A total of ten boys and nine girls were included in each of the younger and older adolescent FGD, with their caregivers participating in the FGD that followed. The characteristics of the adolescents and caregivers included are summarised in Table 1. The mean age of younger and older adolescents was 10 and 15 years, respectively. Mean BMI was comparable between 10–12-year-old boys and girls (17·7 kg/m2); however, at 15–17 years of age boys had a mean BMI of 20·0 kg/m2 and girls of 22·9 kg/m2. Male (n 4) and female caregivers (n 33) were, on average, 42 and 38 years old, respectively, with mean BMI of 23·3 kg/m2 (male) and 31·8 kg/m2 (female).

Table 1 Characteristics of adolescents and caregivers included in focus group discussions, Soweto, Johannesburg, South Africa, July 2018

Data are presented as mean and standard deviation unless indicated otherwise.

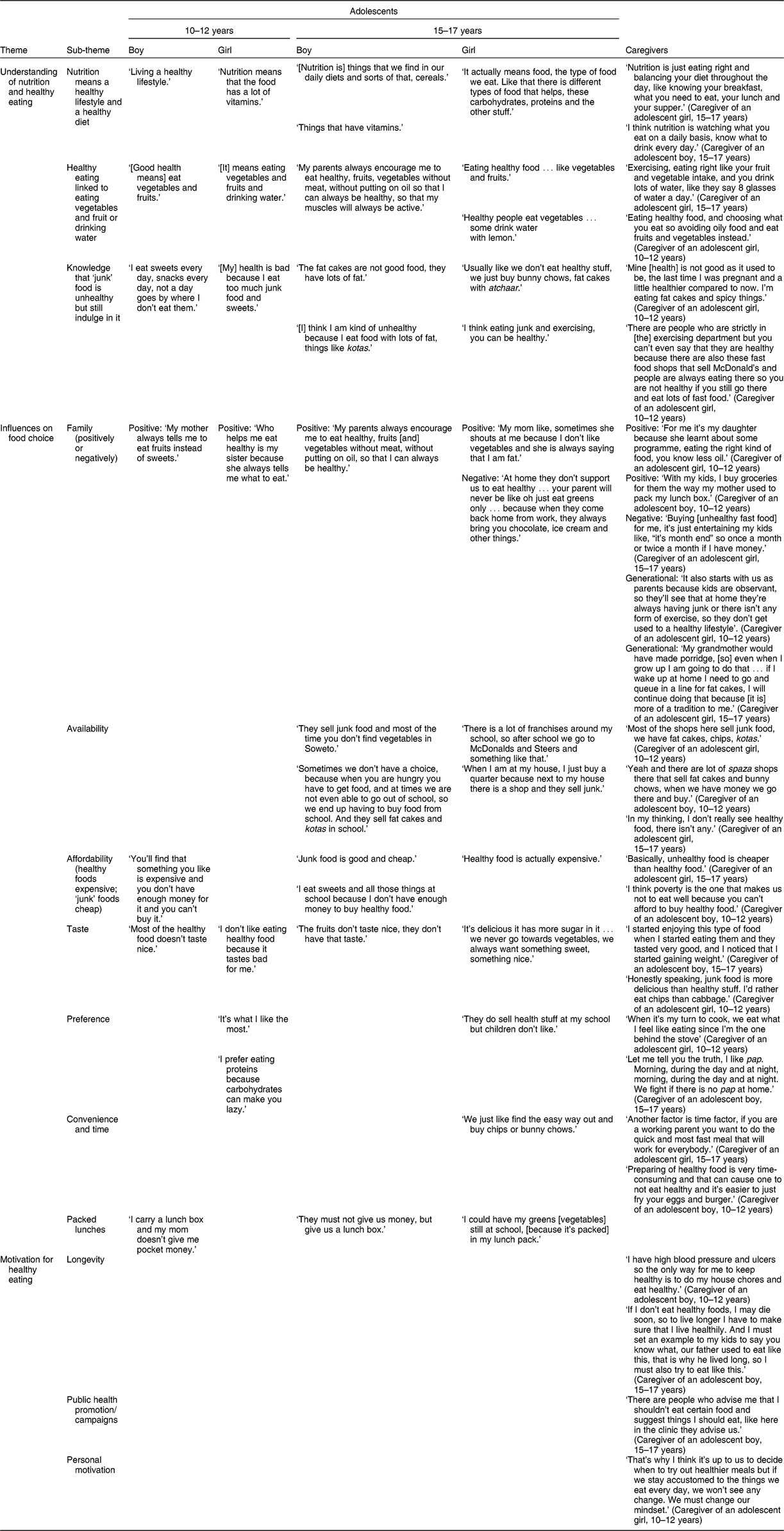

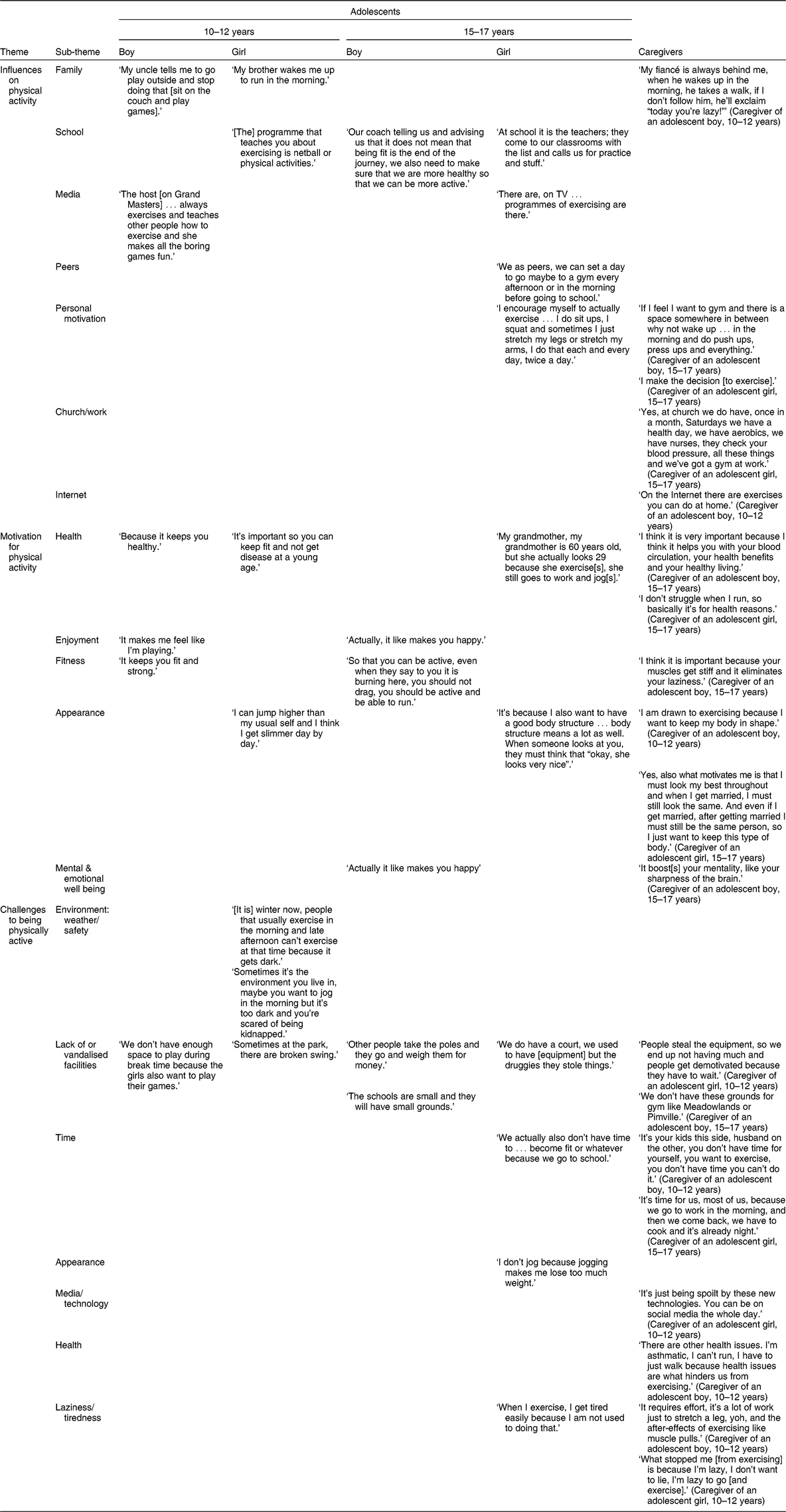

Twenty main themes were identified, with numerous sub-themes. The main themes included: context in which participants lived; their nutritional knowledge; food choices and factors influencing this; opportunities and challenges for healthy eating; physical activities engaged in by participants; motivation for physical activity; and opportunities for and challenges to being physically active (see Tables 2 and 3 for a complete description of themes and sub-themes).

Table 2 Emerging themes and sub-themes related to healthy eating for adolescents and caregivers participating in focus group discussions, Soweto, Johannesburg, South Africa, July 2018

Table 3 Emerging themes related to physical activity for adolescents and caregivers participating in focus group discussions, Soweto, Johannesburg, South Africa, July 2018

Understanding of nutrition and healthy eating

Young and older adolescents, as well as their caregivers, expressed similar understandings of the concept of ‘nutrition’. These understandings were related to ‘living a healthy lifestyle’ accompanied by healthy dietary practices. Across all groups, nutrition was understood to describe individuals’ daily diets, including cereal staples and vegetables, as well as other high-vitamin foods:

‘[Nutrition is] things that we find in our daily diets and sorts of that, cereals.’ (Adolescent boy, 15–17 years)

‘Nutrition means that the food has a lot of vitamins.’ (Adolescent girl, 15–17 years)

Unlike the adolescents, caregivers acknowledged the need for a balanced diet across specified mealtimes as exemplified below:

‘Nutrition is just eating right and balancing your diet throughout the day, like knowing your breakfast, what you need to eat, your lunch and your supper.’ (Caregiver of an adolescent girl, 15–17 years)

All groups associated healthy eating with consuming fruit and vegetables, as well as with drinking water in some cases:

‘[It] means eating vegetables and fruits and drinking water.’ (Adolescent girl, 10–12 years)

‘Eating healthy food, and choosing what you eat so avoiding oily food and eat fruits and vegetables instead.’ (Caregiver of an adolescent girl, 10–12 years)

In addition, study participants had some knowledge of what constituted unhealthy eating practices – specifically linking them to the consumption of high-sugar and high-fat foods, often termed ‘junk’ food items. However, regardless of this understanding, both adolescents and caregivers described regularly eating these foods. The most commonly consumed items were ‘fat cakes’ (deep-fried dough balls), kotas (quarter loaves of white bread filled with fried potatoes, processed cheese and processed meat), other forms of fried potatoes, sweets, condiments and sugar-sweetened beverages:

‘[My] health is bad because I eat too much junk food and sweets.’ (Adolescent girl, 10–12 years)

‘[I] think I am kind of unhealthy because I eat food with lots of fat, things like kotas.’ (Adolescent boy, 15–17 years)

‘Mine [health] is not good as it used to be, the last time I was pregnant and a little healthier compared to now. I’m eating fat cakes and spicy things.’ (Caregiver of an adolescent girl, 10–12 years)

Older adolescent girls also believed that exercising could negate some of the effects of unhealthy dietary practices:

‘I think eating junk and exercising, you can be healthy.’ (Adolescent girl, 15–17 years)

This was in contrast to caregivers who understood that exercise could not compensate for unhealthy eating behaviours:

‘There are people who are strictly in [the] exercising department but you can’t even say that they are healthy because there are also these fast-food shops that sell McDonald’s and people are always eating there so you are not healthy if you still go there and eat lots of fast food.’ (Caregiver of an adolescent girl, 10–12 years)

Influences on food choice

The family was one of the most commonly reported influences on food choice, especially among adolescents. However, family members – and caregivers in particular – were described as having both a positive and negative influence on food choice, thereby encouraging healthy and unhealthy food consumption:

‘My mother always tells me to eat fruits instead of sweets.’ (Adolescent boy, 10–12 years)

‘My parents always encourage me to eat healthy, fruits [and] vegetables without meat, without putting on oil, so that I can always be healthy.’ (Adolescent boy, 15–17 years)

‘At home they don’t support us to eat healthy … your parent will never be like oh just eat greens only … because when they come back home from work, they always bring you chocolate, ice cream and other things.’ (Adolescent boy, 15–17 years)

‘Buying [unhealthy fast food] for me, it’s just entertaining my kids like, “it’s month end” so once a month or twice a month if I have money.’ (Caregiver of an adolescent girl, 15–17 years)

Similarly, adolescents recognised that if caregivers provided them with a packed lunch for school, they would be more likely to eat healthy food during the day:

‘They must not give us money, but give us a lunch box.’ (Adolescent boy, 15–17 years)

‘I could have my greens [vegetables] still at school, [because it’s packed] in my lunch pack.’ (Adolescent girl, 15–17 years)

Closely linked to the family, a cycle of intergenerational factors was described by the caregivers to influence food choice and how eating practices tracked through subsequent generations. For example, they recognised how their current dietary behaviours had been shaped by their parents and that they were now modelling the same dietary practices for their own children:

‘My grandmother would have made porridge, [so] even when I grow up I am going to do that … if I wake up at home I need to go and queue in a line for fat cakes, I will continue doing that because [it is] more of a tradition to me.’ (Caregiver of an adolescent girl, 15–17 years)

‘It also starts with us as parents because kids are observant, so they’ll see that at home they’re always having junk or there isn’t any form of exercise, so they don’t get used to a healthy lifestyle.’ (Caregiver of an adolescent girl, 10–12 years)

Across groups, taste and preference influenced the food choices made by participants. Adolescents and their caregivers felt that unhealthy or ‘junk’ food was more ‘tasty’ than healthy food, with most groups adding that they tended to choose types of food that they either liked the most or that they preferred on a particular day:

‘Most of the healthy food doesn’t taste nice.’ (Adolescent boy, 10–12 years)

‘They do sell health stuff at my school but children don’t like.’ (Adolescent girl, 15–17 years)

‘Honestly speaking, junk food is more delicious than healthy stuff. I’d rather eat chips than cabbage.’ (Caregiver of an adolescent girl, 10–12 years)

Both affordability and availability were perceived as strong drivers of food choice for older adolescents and their caregivers. These groups described unhealthy food as being cheaper and more readily available than healthy food, which was scarce in their communities and expensive when available. However, these influences were minimally or not described by the younger adolescent groups:

‘They sell junk food and most of the time you don’t find vegetables in Soweto.’ (Adolescent boy, 15–17 years)

‘In my thinking, I don’t really see healthy food, there isn’t any.’ (Caregiver of an adolescent girl, 15–17 years)

‘I eat sweets and all those things at school because I don’t have enough money to buy healthy food.’ (Adolescent boy, 15–17 years)

‘Basically, unhealthy food is cheaper than healthy food.’ (Caregiver of an adolescent girl, 15–17 years)

Time and convenience predominantly influenced caregivers’ food choices, with older girls being the only adolescent group to discuss these factors. Participants perceived healthy food as being time-consuming to prepare, with unhealthier food options being quick and convenient:

‘Another factor is time factor, if you are a working parent you want to do the quick and most fast meal that will work for everybody.’ (Caregiver of an adolescent girl, 15–17 years)

‘Preparing of healthy food is very time-consuming and that can cause one to not eat healthy and it’s easier to just fry your eggs and burger.’ (Caregiver of an adolescent boy, 10–12 years)

Motivation for healthy eating

Only caregivers described being motivated to eat healthily, with the desire to maintain or improve their health and, thereby, live longer being the most common motivating factor:

‘If I don’t eat healthy foods, I may die soon, so to live longer I have to make sure that I live healthily. And I must set an example to my kids to say you know what, our father used to eat like this, that is why he lived long, so I must also try to eat like this.’ (Caregiver of an adolescent boy, 15–17 years)

Public health promotion and health experts or campaigns that provided advice or information were also seen to motivate the consumption of healthy foods:

‘There are people who advise me that I shouldn’t eat certain food and suggest things I should eat, like here in the clinic they advise us.’ (Caregiver of an adolescent boy, 15–17 years)

Furthermore, caregivers perceived mindful eating habits and a personal drive to eat well as necessary motivators of healthy eating:

‘That’s why I think it’s up to us to decide when to try out healthier meals but if we stay accustomed to the things we eat every day, we won’t see any change. We must change our mindset.’ (Caregiver of an adolescent girl, 10–12 years)

Physical activity

Participants acknowledged the importance of being physically active; however, only older adolescents and caregivers emphasised a link between exercise and health benefits. Older adolescents believed that ‘being physically active’ was a key component of a healthy lifestyle and caregivers described exercising as a way to ‘take care of your health’. However, as with eating behaviours, some older adolescent girls did not see the independent benefits of being physically active and believed that it was not necessary if they were following a healthy diet:

‘I think I would rather eat healthy and not exercise,’ (Adolescent girl, 15–17 years)

Study participants described partaking in a range of physical activities; types of activities differed significantly between the adolescents and caregivers. For adolescents, physical activity commonly referred to organised sport and/or recreational exercise such as netball, soccer, rugby, basketball and running. The younger adolescents also discussed group play, including skipping and hide-and-seek, as keeping them active. For caregivers, while leisure-time activities were mentioned, the emphasis was on the routine activity required in their daily lives; including working, walking for transport, household chores and generally ‘keeping busy’.

Influences on physical activity

Adolescent boys and caregivers described family members as positively influencing physical activity behaviours. In these cases, parents, siblings and partners not only promoted physical activity through encouragement and reminders, but also actively participated in the exercise themselves:

‘My brother wakes me up to run in the morning.’ (Adolescent boy, 15–17 years)

‘My fiancé is always behind me, when he wakes up in the morning, he takes a walk, if I don’t follow him, he’ll exclaim “today you’re lazy!”’ (Caregiver of an adolescent boy, 10–12 years)

Similarly, older adolescent girls believed that peers could motivate each other to be more physically active in future:

‘We as peers, we can set a day to go maybe to a gym every afternoon or in the morning before going to school.’ (Adolescent girl, 15–17 years)

School strongly influenced whether adolescents were physically active across groups, with school-based programmes and classes, as well as teachers and/or coaches, encouraging physically active behaviours:

‘[The] programme that teaches you about exercising is netball or physical activities.’ (Adolescent girl, 10–12 years)

‘At school it is the teachers; they come to our classrooms with the list and call us for practice and stuff.’ (Adolescent boy, 15–17 years)

Likewise, for caregivers, the provision of health-related programmes and services at work and/or church were seen to support physical activity. These varied between the direct provision of opportunities to be active – via classes and gym facilities – and regular health monitoring to improve individuals’ health awareness and to promote healthy behaviours:

‘Yes, at church we do have, once in a month, Saturdays we have a health day, we have aerobics, we have nurses, they check your blood pressure, all these things and we’ve got a gym at work.’ (Caregiver of an adolescent girl, 15–17 years)

Younger adolescent boys and older girls saw the media as a positive influence on their desire to be physically active, as well as an avenue to do so via exercise programmes:

‘The host [on Grand Masters] … always exercises and teaches other people how to exercise and she makes all the boring games fun.’ (Adolescent boy, 10–12 years)

For 15–17-year-old girls and adolescent caregivers, personal motivation was seen as the most important influence on whether or not they participated in physical activity in some cases:

‘I encourage myself to actually exercise … I do sit ups, I squat and sometimes I just stretch my legs or stretch my arms, I do that each and every day, twice a day.’ (Adolescent girl, 15–17 years)

‘If I feel I want to gym and there is a space somewhere in between, why not wake up … in the morning and do push ups, press ups and everything.’ (Caregiver of an adolescent boy, 15–17 years)

Motivation for physical activity

Participants reported deriving their motivation for physical activity as a way of keeping healthy and fit. This was predominantly emphasised by caregivers who may have already been struggling with health issues:

‘I think it is very important because I think it helps you with your blood circulation, your health benefits and your healthy living.’ (Caregiver of an adolescent boy, 15–17 years)

For adolescents – particularly the boys – exercise was more often associated with short-term benefits, such as their enjoyment and physical appearance. One boy stated that physical activities made him feel like he was ‘playing’ (adolescent boy, 10–12 years). Similarly, boys perceived activity as being beneficial for their emotional well-being by making them ‘happy’ (adolescent boy, 15–17 years).

Appearance strongly motivated both younger and older adolescent girls, as well as adolescent caregivers, to be physically active:

‘I can jump higher than my usual self and I think I get slimmer day by day.’ (Adolescent girl, 10–12 years)

‘It’s because I also want to have a good body structure … body structure means a lot as well. When someone looks at you, they must think that “okay, she looks very nice”.’ (Adolescent girl, 15–17 years)

‘I am drawn to exercising because I want to keep my body in shape.’ (Caregiver of an adolescent boy, 10–12 years)

Challenges to being physically active

The biggest reported challenge to being physically active across groups was related to facilities being unavailable or not usable at both school and in the community. Both adolescents and caregivers described either a lack or shortage of space and facilities to be physically active:

‘We don’t have enough space to play during break time because the girls also want to play their games.’ (Adolescent boy, 10–12 years)

‘We don’t have these grounds for gym like Meadowlands or Pimville.’ (Caregiver of an adolescent boy, 15–17 years)

In addition, where space and facilities were provided for exercise in the community, the equipment was vandalised and/or stolen, making use of this impossible:

‘Other people take the poles and they go and weigh them for money.’ (Adolescent boy, 15–17 years)

‘We do have a court, we used to have [equipment] but the druggies have stolen things.’ (Adolescent girl, 15–17 years)

‘People steal the equipment, so we end up not having much and people get demotivated because they have to wait.’ (Caregiver of an adolescent girl, 10–12 years)

For young adolescent girls, environmental factors – namely weather and safety concerns – were a substantial challenge to partaking in exercise. These girls reported feeling unsafe engaging in community-based activity when it was winter and when it was too dark to be outside before or after school:

‘[It is] winter now, people that usually exercise in the morning and late afternoon can’t exercise at that time because it gets dark.’ (Adolescent girl, 10–12 years)

‘Sometimes it’s the environment you live in, maybe you want to jog in the morning but it’s too dark and you’re scared of being kidnapped.’ (Adolescent girl, 10–12 years)

Time constraints and laziness/tiredness were discussed as challenges to being physically active by older adolescent girls and caregivers. In these groups, some participants mentioned that their busy work schedules and household responsibilities did not allow them the time to exercise:

‘We actually also don’t have time to … become fit or whatever because we go to school.’ (Adolescent girl, 15–17 years)

‘It’s time for us, most of us, because we go to work in the morning, and then we come back, we have to cook and it’s already night.’ (Caregiver of an adolescent girl, 15–17 years)

This was contrasted by those who attributed their lack of physical activity to their own laziness or to feeling tired when engaging in exercise:

‘When I exercise, I get tired easily because I am not used to doing that.’ (Adolescent girl, 15–17 years)

‘What stopped me [from exercising] is because I’m lazy, I don’t want to lie, I’m lazy to go [and exercise].’ (Caregiver of an adolescent girl, 10–12 years)

For 15–17-year-old girls only, concerns around their appearance prevented them from exercising, with fears of weight loss and a desire to maintain a fuller figure being important barriers to activity:

‘I don’t jog because jogging makes me lose too much weight.’ (Adolescent girl, 15–17 years)

Although participants thought exposure to the media and the Internet provided motivation and opportunity for being physically active, caregivers blamed such advancements in media and technology for inactivity in adolescents. They believed that the substantial amount of time their children spent indoors using mobile phones and social media prevented them from engaging in physical activity:

‘It’s just being spoilt by these new technologies. You can be on social media the whole day.’ (Caregiver of an adolescent girl, 10–12 years)

Discussion

The novel findings from the present study were that, unlike their caregivers, South African adolescents were not motivated to eat healthily and did not recognise the need to develop consistent patterns of healthy eating and physical activity for their long-term health. In addition, adolescents failed to appreciate that both healthy eating and physical activity were necessary for a healthy lifestyle and believed that engagement in one could compensate for a lack of the other. Although adolescents gain independence as they age, the study showed that they commonly blame a lack of autonomy in making household decisions – and thereby caregiver influence – for their unhealthy food choices. With regard to physical activity, adolescents and caregivers had distinct perceptions of what this comprised of within their daily lives and, therefore, breaking down the siloes of recreational v. routine activity between groups may encourage increased engagement across activity ‘domains’. While some drivers of healthy eating and physical activity behaviours were consistent across participants, key differences were expressed between adolescent age and gender groups, as well as between adolescents and caregivers, that can be targeted in intervention strategies.

Healthy eating

Adolescents and caregivers across all age and gender groups expressed a basic understanding of nutrition and related this to patterns of healthy eating and to healthy lifestyle choices overall. However, while participants consistently identified certain types of food as ‘healthy’ or ‘unhealthy’, there were clear distinctions between participants’ descriptions of healthy eating practices and their day-to-day behaviours. For example, all groups reported regular consumption of unhealthy foods despite their acknowledgement of the health implications. Similar understandings of healthy eating behaviours have previously been demonstrated in rural and urban South African girls, with urban girls particularly expressing strong disparities between their knowledge of healthy/unhealthy foods and their regular consumption of ‘junk’ food items(Reference Sedibe, Feeley and Voorend11,Reference Voorend, Norris and Griffiths12,Reference Sedibe, Kahn and Edin20) . Our study adds to these results by confirming that a basic understanding of healthy eating does not necessarily facilitate these behaviours, regardless of age or gender.

Although an understanding of nutrition was evident in all study groups, the depth of knowledge and prioritisation of healthy eating practices differed substantially between adolescents and caregivers. Unlike their caregivers, adolescents failed to appreciate that long-term health benefits required the development of consistent and lasting dietary habits. In some cases, they also overlooked the independent importance of diet within a healthy lifestyle, believing that exercise could compensate for unhealthy eating. Additionally, while adolescents discussed a range of facilitators and barriers to healthy eating, only caregivers described any level of motivation to eat healthy foods. This motivation was predominantly driven by a desire to either improve their health or prevent adverse health outcomes, as well as to model healthy lifestyles to their children. This is supported by previous studies which show adolescents to make substantially poorer lifestyle and food choices than adults(Reference Andrade de, Previdelli and Cesar21). In addition, research suggests that the intention to consume healthy food is stronger in adults with diagnosed co-morbidities, suggesting that the need for healthy eating is often only prioritised by those with personal experience of adverse effects(Reference Wang and Chen22).

Across study groups, the adolescent–caregiver relationship was described as having the strongest influence on adolescents’ eating practices. Due to a lack of autonomy described by adolescents in household food preparation, their consumption of healthy v. unhealthy food was often driven by their caregivers’ own priorities. Older adolescents particularly reported a lack of support for healthy eating in the home. This may be influenced by the level of perceived responsibility that caregivers have for their children’s lifestyle choices as they age. However, caregivers did acknowledge their influence on adolescent food choice, with some recognising an opportunity to model healthy eating behaviours and others reporting that they provided adolescents with ‘junk’ food to please them. In addition, caregivers described an intergenerational aspect to the adoption of eating behaviours, attributing their lifestyle choices to their own parents or to family traditions. Experiences of positive caregiver influence have been previously demonstrated in a rural South African setting, where female caregivers were reported to encourage consumption of locally grown vegetables and to regularly cook these in the home(Reference Sedibe, Kahn and Edin20).

Although taking a packed lunch to school was seen to facilitate healthy eating, this also depended on the caregivers’ own prioritisation of healthy lifestyle choices and their commitment to packing a healthy lunch for the adolescent. Previous qualitative studies have supported the benefit of home-packed lunches to promoting healthy food consumption by adolescent girls(Reference Sedibe, Feeley and Voorend11,Reference Voorend, Norris and Griffiths12) . Adolescents in our study believed that by providing them with money to purchase food at school, caregivers were facilitating ‘junk’ food consumption; either due to less healthy food available in schools and/or to enjoyment of processed foods and snacks. This is supported by previous data in which adolescent girls expressed a desire for greater variety in the food items available at school, but also admitted they would continue to buy ‘junk’ foods because they were filling, enjoyable and easy to share between friends(Reference Sedibe, Feeley and Voorend11).

The literature supports the predominant role of parental control and/or modelling in determining the food choices of children and adolescents(Reference Scaglioni, De Cosmi and Ciappolino23–Reference Spronk, Kullen and Burdon25). It also highlights that the level of control and/or influence caregivers have decreases with adolescent age(Reference Scaglioni, De Cosmi and Ciappolino23,Reference Williams, Veitch and Ball26,Reference Videon and Manning27) . It is therefore important that healthy eating behaviours are modelled early in adolescents’ lives to ensure that they develop and maintain healthy preferences as they age and gain autonomy. Living in obesogenic settings where access to unhealthy foods is dominant has been shown to create confusion among parents/caregivers when making nutritious, affordable and convenient food choices for their children(Reference Bathgate and Begley28). In addition, caregivers across settings have reported being highly influenced by adolescents’ taste preferences and demands(Reference Bathgate and Begley28). Therefore, supporting them to make informed and appropriate decisions within adolescent–caregiver dynamics and community contexts is necessary.

All study groups saw taste and/or preference as determining food choices, with desirability aspects of food often predominating over those related to health. Youth have been previously found to prioritise their like or dislike for certain foods over what is ‘good’ for them, associating fast food with pleasure, social interaction and friendship(Reference Shepherd, Harden and Rees29). However, our data show that, even in caregivers, consistent prioritisation of healthy eating is compromised by preference regardless of a deeper understanding and appreciation of dietary health consequences.

Affordability and availability played a role in food choices in older adolescents and caregivers only. These groups described unhealthy food as being cheaper and more readily available to them, with their access to healthy fruit and vegetables being limited at school and/or in the community. Similarly, busy schedules and time restrictions, as well as the inconvenience of preparing home-cooked meals, were viewed as barriers to healthy eating by older adolescent girls and caregivers. While these are commonly reported barriers to healthy eating in qualitative studies, their relevance clearly differs by age and gender. For example, limited access to money and lower buying power at younger ages may mask the influence of cost and access to certain food items(Reference Dennisuk, Coutinho and Suratkar30). Additionally, while adolescent girls often become more involved in household chores as they age, boys and younger girls may not be affected by time restraints and inconvenience due to minimal involvement in meal preparation(Reference Berge, MacLehose and Larson31). However, adolescent involvement in food preparation and more frequent family meals have been associated with healthy household food availability, improved diet quality and reduced obesity risk(Reference Berge, MacLehose and Larson31–Reference Hammons and Fiese34). In addition, data show positive effects of cooking/food preparation interventions on food intakes, with a predominant effect on the consumption of fruit and vegetables, fibre, fat and salt(Reference Reicks, Trofholz and Stang35).

Physical activity

The perceptions of what constituted physical activity differed substantially between adolescents and caregivers. Adolescents reported participation in organised school-based or recreational sports as their predominant source of activity, with younger adolescents also acknowledging engagement in play as a form of exercise. In contrast, caregivers engaged in physical activity as a result of day-to-day work and household tasks or as a form of transportation, with little mention of recreational exercise. These differences are important as they highlight key focal points for intervention between the groups. For example, in adolescents, education and promotion around opportunities for physical activity within their daily lives – through walking, doing chores and limiting sedentary time – may be beneficial in facilitating more regular engagement in activity. It may also provide opportunities for exercise to those who either dislike or struggle to participate in sport or for whom facilities to engage in sport are lacking. In caregivers, prioritisation of recreational physical activity should be a focus, particularly for those who lead increasingly sedentary lives due to urbanisation-associated changes in work, household and transportation environments(Reference Gassasse, Smith and Finer36).

The value of physical activity was recognised across study groups; however, the reasons for this differed according to age and gender. Specifically, adolescents prioritised more short-term benefits – such as appearance and enjoyment – than caregivers who were more concerned with longer-term health consequences. While appearance motivated activity in females regardless of age, this was most influential in adolescent girls who described wanting to be ‘slim’ and to maintain a ‘good body structure’. Many studies have supported a greater desirability for slimness in girls compared with boys, with boys being more motivated by strength, power and a muscular physique(Reference Tatangelo and Ricciardelli37,Reference Silva, Taquette and Coutinho38) . This was demonstrated in our FGD, during which boys focused on the fitness-related benefits of exercise, namely being strong and active.

For older girls, appearance also acted as a barrier to activity in some cases, with fears of weight loss or of being too thin restricting their engagement in exercise. This is commonly reported in black South African women, for whom a fuller figure has been traditionally associated with beauty, happiness, health and affluence, and a low body weight with the presence of disease(Reference Mvo39–Reference Draper, Grobler and Micklesfield41). While urbanisation and improved knowledge of the health consequences of obesity have been associated with a shift in the desirability of a larger body size, cultural perceptions around weight loss seem to persist(Reference Draper, Grobler and Micklesfield41–Reference Gitau, Micklesfield and Pettifor44). This must be taken into account when targeting interventions towards healthy body images and behaviours.

Only boys discussed their enjoyment of being physically active as a motivator, with some mentioning that it made them happy or feel good. For boys, exercising was often perceived as being fun and as something that they wanted to do, rather than something that they needed to do for other reasons. This is supported in South African studies, with boys more likely to partake in physical activity and demonstrating a more positive attitude to being active(Reference van Biljon, McKune and DuBose45,Reference Uys, Bassett and Draper46) .

As with eating practices, while the health benefits of exercise were recognised by adolescents, they were more pertinent to the caregivers who were more likely to have experience of a lifestyle-related chronic condition. Prioritisation of prevention – rather than curative – strategies to promote healthy lifestyle choices is critical if long-term shifts in adolescent behaviour are to be achieved.

Family members and peers, as well as school/work environments, were seen as positive influences on participants’ engagement in physical activity. These support platforms not only provided participants with the encouragement and facilities needed to engage in activity, but also with health information and camaraderie during exercise. Previous studies have shown that intervention strategies which encourage teamwork and peer-to-peer interaction have been effective in increasing the motivation towards, and involvement in, physical activity within school environments and that this, in turn, increases peer support and enhances friendship dynamics among participants(Reference Brustio, Moisè and Marasso47,Reference Huang, Gao and Hannon48) . However, in cases where the space and/or facilities at schools were lacking, or where physical activity was not incorporated into the school curriculum, this was seen as a key barrier to being active by adolescents. Similarly, within the community, either a lack of facilities or facilities and equipment being vandalised or stolen prevented physically active behaviours in adolescents and caregivers. Specifically, in young girls, community environments and safety concerns were highlighted as barriers to being physically active. This has been previously shown in urban South African girls and emphasises that providing accessible environments for safe and supported activity at school and in the community is an important facilitator of physical activity(Reference Sedibe, Feeley and Voorend11). In addition, incorporating peer-to-peer dynamics and household-level support of, and engagement in, physical activity may be important in facilitating higher levels of enjoyment and participation, particularly in girls(Reference Salvy, Roemmich and Bowker49,Reference King, Tergerson and Wilson50) .

Technology and the media were described as both positive and negative influences on physical activity. Adolescents and caregivers mentioned that the Internet and media provided them with both the encouragement and the means to be active. Influencers on television programmes acted as role models for exercise and made activity seem more fun, while both television programmes and the Internet provided exercise programmes for individuals to follow within their own homes. However, caregivers also viewed technological advances as barriers to activity; they blamed screen time and social media for children not being active outdoors. High levels of screen time and sedentary behaviour are well documented in both urban and rural South African settings(Reference Micklesfield, Pedro and Kahn51,Reference De Vos, Du Toit and Coetzee52) . These behaviours not only limit the time available for active engagement in exercise, but are independently associated with obesity and non-communicable disease risk(Reference Tremblay, LeBlanc and Kho53). Health behaviour interventions must therefore have a dual focus which targets both participation in physical activity and reductions in sedentary time on a daily basis.

Implications

While many of the facilitators and barriers to healthy eating and physical activity are similar between adolescents and caregivers, as well as between age and gender groups, there are some key differences which need to be recognised for intervention development. For example, in boys who enjoy being active, issues around space and facilities to do so are often seen as primary barriers. However, in girls who do not see the enjoyment in exercising, building their desire to be active or less sedentary – whether for health or positive body image reasons – is an important first step. Also, providing more safe and desirable opportunities for girls in poor urban settings, like Soweto, is critical to enable more exercise. Due to changing priorities, responsibilities and schedules, and growing independence and financial freedom as adolescents age, tailoring interventions to the desires and means of the audience is critical. In addition, an understanding and appreciation of the importance of healthy lifestyle choices for longer-term benefits must be emphasised to adolescents. Finally, greater commitment to intervention messages and actions by caregivers is vital since they have the ability to either undermine or to support these strategies. Specifically, the adolescent–caregiver relationship must play an integral role in intervention development, with caregivers acting as motivators to, and role models for, healthy lifestyle choices.

Strengths and limitations

The present study benefited from the use of FGD in comparison to other qualitative methods of data collection. The FGD were cost-effective, as they allowed for collection of data from seventy-five participants within a short period of time, while accommodating the different opinions and views reflected in different group dynamics(Reference Krueger and Casey54). In addition, FGD were particularly suitable for the younger adolescents because they allowed for flexibility in the discussion and participants were able to build upon one another’s points, which resulted in further articulation of thoughts and ideas. The presence of a facilitator was useful in creating a relaxed and comfortable environment, especially for the younger adolescents, while the observer assisted in capturing non‐verbal communications. It is important to note that, unlike the caregiver and older adolescent groups, the younger adolescent groups were found to have shorter attention spans of between 20 and 25 min. To attend to this, the facilitator provided in-between breaks, including ice breakers, which helped to gain back their attention.

The study is not without limitations. The FGD were conducted within our research unit and not in a natural atmosphere where participants live and engage in their daily activities, thus we could not validate whether what was said was actually what happened in home, work or school environments. However, the composition of different FGD groups based on age and gender, together with rigorous data analysis strategies, revealed major themes that were consistent and cut across all groups, and this formed the basis of our findings. Use of FGD, especially with younger participants, has challenges in that the responses may be influenced by one or two dominant participants. While this could potentially bias the results in some cases, the use of a well-trained and experienced facilitator played an essential role in reducing this risk in our study. Additionally, the use of homogeneous groups allowed for free interaction between participants. The potential of FGD participants knowing each other is another common limitation that may influence biased results. In our study, this limitation was controlled by recruiting participants from three different areas in Soweto. In addition, although information was given to all community members, only those interested made contacts with our research assistants and were recruited for the study. This prevented the inadvertent introduction of error through a skewed selection. As only eighty participants were recruited, our findings may not be generalisable to the entire Soweto population. However, having representative samples or producing generalisable findings is not the aim of qualitative research. Instead, the intention is to generate an in-depth understanding of a phenomenon and explore ‘transferability’ to other contexts(Reference Ritchie and Lewis55). Considering the exploratory nature of our study, the eight FGD conducted within the four homogeneous groups were sufficient to capture perceptions of diet and physical activity behaviours and to reach code saturation during analysis(Reference Hennink, Kaiser and Marconi56).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the current study presents novel data on the various facilitators and barriers to healthy eating and physical activity between younger and older adolescent boys and girls, as well as their caregivers, which should be incorporated into future interventions. For example, the importance of the adolescent–caregiver relationship, as well as the growing responsibility of adolescents for their own health and lifestyle choices, must play integral roles. In addition, differing priorities by sex and age must be utilised to ensure that interventions address the needs and desires of specific target groups, while ensuring that opportunities for healthy lifestyle choices are available to all.

Further, our data illustrate that, in transitioning urban poor contexts such as Soweto, a complex interplay of determinants, desires and disablers impacts adolescents and their caregivers independently and interrelatedly around healthy living. Knowledge alone is therefore not enough to overcome barriers to healthier eating and living a physically active and less sedentary lifestyle, particularly as these urban environments become more obesogenic. Given the importance of the adolescent stage of the life course, a significant shift is needed in thinking about adolescent health. Ralston and colleagues argue that a new narrative about obesity is urgently needed. This new narrative would: (i) recognise that obesity prevention efforts require multiple sectors to partner and to utilise diverse entry points; (ii) shift responsibility beyond the usual suspect of individuals to include upstream drivers (e.g. market forces); (iii) prioritise childhood obesity in poor environmental contexts; and (iv) employ strategies that address both inequalities and the determinants of obesity(Reference Ralston, Brinsden and Buse57). Given the challenges faced by adolescents and caregivers in our context, strategies that address the obesity epidemic at each level are needed if we are to ensure affordable, accessible, safe and usable opportunities for healthy eating and physical activity in current and future generations.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: Transforming Adolescent Lives through Nutrition (TALENT) is a collaborative network for adolescent nutrition and health in sub-Saharan Africa and India and is funded by the UK Medical Research Council’s Confidence in Global Nutrition and Health Research award (grant number MC_PC_MR/R018545/1). The funder had had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: S.V.W.: conceptualisation and design, data analysis and interpretation, writing of original draft, review and editing of manuscript; E.N.B.: methodology, data analysis and interpretation, review and editing of manuscript; G.M.: project supervision, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, review and editing of manuscript; M.M.: data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, review and editing of manuscript; G.M.: data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, review and editing of manuscript; M.B.: conceptualisation and design, methodology, review and editing of manuscript; P.H.-J.: conceptualisation and design, methodology, review and editing of manuscript; C.F.: funding acquisition, conceptualisation and design, methodology, review and editing of manuscript; S.A.N.: funding acquisition, conceptualisation and design, methodology, review and editing of manuscript. All authors gave final approval of the version to be submitted. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all research involving study participants was approved by the University of the Witwatersrand’s Research Ethics Committee (Medical) (approval number M170680). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019002829