Adolescence, the period of transition from childhood to adulthood, is commonly regarded as the second window of opportunity for nutrition intervention to reverse growth retardation and the intergenerational effects of malnutrition(Reference Prentice, Ward and Goldberg1). The 2016 UNICEF report showed that there are currently 1·2 billion adolescents in the world(2), 90 % of whom reside in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC)(3). In sub-Saharan Africa(2), including Ethiopia(4), adolescents account for a quarter of the population. The 2018 Global Nutrition Report indicated that malnutrition is unacceptably high across many countries, including Ethiopia. Moreover, as many LMIC are undergoing rapid nutritional and lifestyle transition, countries are faced with the coexistence of adolescent undernutrition and obesity(5). This double burden during adolescence has negative health consequences for adolescents now, in the future and for their offsprings(6).

Influences on adolescent nutrition are multiple(Reference Fanzo7) and involve complex interactions between individual, familial, community and environmental level factors(Reference Verstraeten, Leroy and Pieniak8-Reference Keats, Rappaport and Shah13). Although adolescents’ undernutrition is the main problem in LMIC, there has been a recent shift in the dietary habits of adolescents with the rise in consumption of energy-dense, packaged foods(Reference Keats, Rappaport and Shah13) alongside a steep decline in energy expenditure, both of which contribute to an increased risk of adolescent obesity(Reference Wiklund14). To date, no research has explored perceptions of these influences among adolescents living in Jimma, Ethiopia.

Despite its importance to health throughout the life course, adolescent nutrition and physical activity have either been neglected(6) or given limited emphasis in LMIC research(Reference Mates and Khara15), including that from Ethiopia. Existing studies of adolescent nutrition in Ethiopia have focused on quantitative outcomes like the prevalence of, and factors associated with, malnutrition. To date, there has been limited qualitative research exploring the views, motivations and influences on these broad determinants(Reference Morrow, Tafere and Chuta16). Adolescents may have different experiences, perspectives and explanations regarding their nutrition and physical activity than adults, so hearing adolescents’ voices is important to gain insights into their lives and behaviours if we wish to design effective interventions. Our study aimed to fill this knowledge gap by using a qualitative research design to capture the voices of adolescents and caregivers living in Jimma, Ethiopia. Contextual information was also gathered using a survey of socioeconomic status, growth (height and weight) and dietary diversity score (DDS). This study formed part of Transforming Adolescent Lives through Nutrition (TALENT); an international collaboration aiming to understand adolescents’ dietary behaviour and opportunities for physical activity.

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted in Jimma city, Ethiopia, between June and July 2018. Jimma is situated in the southwestern region of the country, 352 km from the capital, Addis Ababa. It is one of the oldest cities in Ethiopia, established around 1830. The town is known for its multi-ethnic and diverse religious inhabitants living together harmoniously. Jimma is growing rapidly through an expansion of construction and infrastructure like roads, public facilities (e.g., schools and hospitals) and modern facilities (e.g., gymnasiums and swimming pools). There is high inward migration from the surrounding rural areas because people are searching for better-paid jobs, education for their children and a better quality of life. Although Ethiopia is classified as a lower income country, the lifestyle of the Jimma population can be described as that of a LMIC setting. Some of the population live in extreme poverty, with an inadequate income to account for the cost of living including education, food and other basic daily needs. There are also many segments of the population that live in better conditions whereby they earn enough for their children to be educated and to cover the cost of basic needs. These individuals live in large compounds or apartments. Based on the 2011 population estimation, a total of 205 163 (nearly 0·2 % of the total population in Ethiopia) people reside in Jimma city; 40 418 (19·7 %) of whom are 15–24 years and 97 679 (47·6 %) are below 15 years. The majority of adolescents (nearly 80 %) in Jimma attend school. However, approximately 20 % of adolescents leave school to get jobs to support themselves and their parents financially.

Research design and participants

Adolescents and their parents were recruited through convenience sampling. Accordingly, forty-one adolescents participated in five focus group discussions (FGD) and twenty-two parents in three FGD. Urban health extension workers, already working in the communities, recruited participants by approaching families they already knew. Capitalising on the rapport that existed between participants and researchers maximised the success of the recruitment process. A heterogeneous sample of adolescents was recruited from low- and lower-middle-income families. The health extension workers were not involved in conducting the FGD.

Initially, adolescents completed a quantitative socio-demographic questionnaire and provided anthropometric data to contextualise the qualitative data. A sub-sample of survey respondents was invited to take part in a FGD. FGD were chosen as the most appropriate data collection method to obtain insights from adolescents and their parents, as well as a sense of the social norms arising from group discussion(Reference Krueger, Casey and Mary17).

Socio-demographic questionnaire: Information on maternal education and job status, head of household, occupational status of the head of household, household information, sources for drinking water and use and ownership of various household goods were collected.

Anthropometric measurements: Height was measured to the nearest of 0·1 cm using a stadiometer (SECA), while weight was measured in kg to the nearest of 0·1 kg using Tanita 418 (Tanita Corp.) scale.

FGD guide: The FGD guide aimed to facilitate discussions to explore adolescent diet and physical activity (which includes walking, running, physical exercise, sports, gyms, playing ball and chores), from the perspectives of both adolescents and their caregivers.

Data collection

Prior to data collection, researchers attended a 5-d training workshop on qualitative data collection methods as part of the TALENT collaboration. The FGD guide was developed by the primary researcher and members of the TALENT team (S.W., M.B. and P.H.J.) during the workshop and subsequently piloted and revised based on feedback and discussions (see the FGD guide in the online supplementary material).

FGD groups included both younger (aged 10–12 years) and older adolescents (aged 15–17 years). Each FGD was conducted by one facilitator and one observer. Boy and girl FGD were conducted separately.

The time and location of the FGD were arranged based on participants’ convenience. Once consent/assent was obtained, researchers began by introducing themselves, reiterating the study aims and procedures and ensuring that the participants were happy for the FGD to be recorded. FGD lased approximately 90 min.

Data analysis

Focus group discussions

The FGD were conducted in participants’ local language to facilitate better rapport and understanding. The data were transcribed verbatim, translated into English to aid comparison across the TALENT collaboration and checked against the audio recording to ensure accuracy. Thematic analysis following Braun & Clarke’s(Reference Braun and Clarke18) step-by-step guide was conducted, with the aid of qualitative analysis software (NVIVO version 12). Transcripts were re-read until the researchers were immersed in the data. Emerging themes were noted down to form the beginning of the coding framework. Transcripts were coded inductively, and the coding framework was revisited and revised. Codes were checked by members of the TALENT collaboration (S.W., P.H.J. and M.B.). Once all of the data had been coded, similar codes were merged together and categorised. Categories were revisited and revised, discussed among the research team and developed into main themes. These themes are presented below, with direct quotes from the participants used throughout, to retain participants’ voices in the report.

Contextual survey data

Frequencies and percentages were computed for categorical data, and mean, median and sd were computed for continuous data. The WHO Anthroplus software was used to generate adolescent growth standard (z-score) and compared with WHO 2007 reference data.

Results

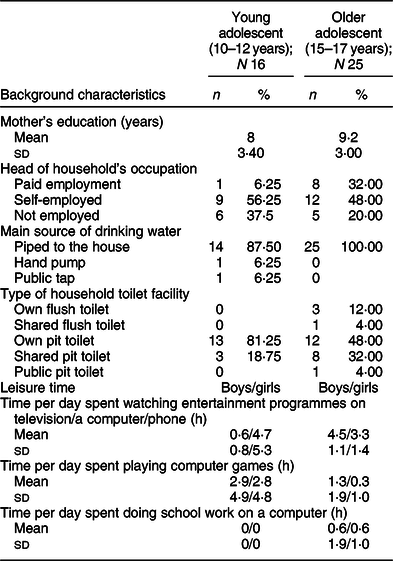

A total of eight FGD were conducted including five with adolescents (n 41; twenty-five older and sixteen younger). Ten and fifteen of the older and seven and nine of the younger adolescents were boys and girls, respectively. Three additional FGD for parents included nine fathers and thirteen mothers, separately. A detailed description of the socio-economic profile of the participants is presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1 Description of participants in each focus group discussion (FGD), Jimma, Ethiopia

Table 2 Characteristics of the adolescent participants in the qualitative study

Table 2 shows that the mothers of adolescents in the current study averaged 3 years of formal education, and the majority were self-employed. Other socio-demographic characteristics of the adolescents are presented in Table 2.

Adolescent characteristics

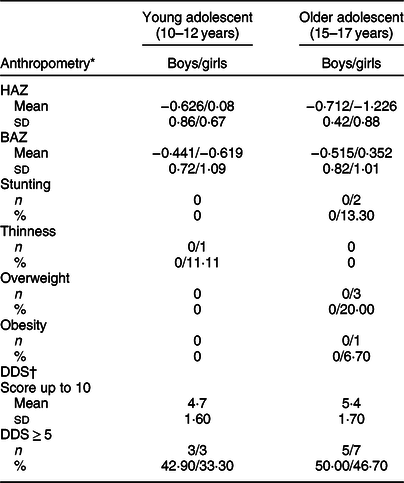

As can be seen from Table 3, there were age and gender differences in the nutritional status of adolescents. Among our sample, stunting was only present among the older adolescent girls (13 %) and underweight was only present among the younger adolescent girls, compared with the other groups. In addition, overweight and obesity were present (20 and 6·7 %, respectively) in the older girls and not reported among the boys or younger girls.

Table 3 Growth characteristics and dietary diversity score for adolescent participants in the qualitative study

HAZ = height-for-age z-score, BAZ = BMI-for-age z-score; DDS = dietary diversity score.

Stunting = HAZ < −2 sd; Thinness = BAZ < −2 sd; Overweight or obese = BAZ > +2 sd.

* WHO 2007 growth standards.

† Minimum dietary diversity score for women, FAO 2016.

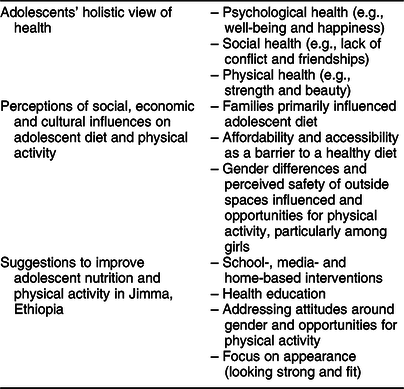

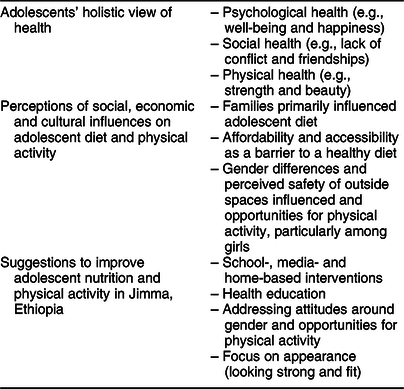

The dominant themes from the discussions with adolescents and their caregivers included adolescents’ holistic view of health and perceptions of the social, economic and cultural influences on adolescent diet and physical activity. Adolescents and caregivers also provided some suggestions for effective interventions to improve adolescent diet and physical activity.

Adolescents’ holistic view of health

The adolescents in the current study displayed a holistic understanding of health. When asked about what made a person healthy, they gave a wide variety of answers including psychological, social and physical aspects of a person’s well-being. Psychological well-being was highlighted as an important aspect of health for many of the adolescents:

When someone has happiness both in and outside I call him/her healthy person. (Older girls, FGD 3)

Adolescents also felt that a sign of a healthy person was being able to maintain good relationships with others, including both peers and family members. Both loneliness and conflict were perceived to be associated with poor health, whereas altruism and open communication with people were seen to be allied with good health:

Those who talks and sit alone are unhealthy people. (Younger boy, FGD 2)

If individuals are happy while at home, plus if the family members understand them well and discuss everything, they are healthy. Arguing makes individuals unhealthy. (Older girl, FGD 3)

Many adolescents associated having a good physical appearance with both beauty and physical performance, both of which they considered indications of a healthy person:

Those with shiny faces and those who are strong are healthy people. (Younger boy, FGD 2)

We know about living a healthy life

Adolescents were well informed about the influence of health behaviours on health outcomes. Despite specifically being asked about their perceptions of health in relation to diet and physical activity, many emphasised the importance of avoiding substance abuse in being healthy.

Those who protect themselves from different addictions are healthy. (Older boy, FGD 4)

They understood the negative effects of cigarette smoking, alcohol, Khat (a psychoactive stimulant leaf from an evergreen plant cultivated in the horn of Africa) and other drugs.

Overall, adolescents demonstrated a detailed understanding of how nutrition and physical activity influence health outcomes. They perceived food as healthy if it contained more vegetables, less oil and was cooked hygienically:

…those which have positive impact on health… like fruits, vegetables - these are healthy food stuffs. (Younger boy, FGD 2)

Whereas, unhealthy foods were described as those resulting in some sort of illness:

What determines food choice is our health, e.g. when some eats peppery “wotFootnote 1 ” food, they might get sick so what determines our choice is our inner body and health. (Younger boy, FGD 2)

Participants viewed physical activity as being important for both physical and psychological well-being:

If someone performs and become physically active, then he/she can be physically and mentally competent and also prevent the occurrence of diabetes, hypertension and heart diseases. (Older boy, FGD 4)

Perceptions of social, economic and cultural influences on adolescent diet and physical activity

Generally, participants reported the most prominent influences on adolescents’ health behaviours to be social and cultural in nature. These included the family environment, socio-economic status and gender. In general, food choice and physical activity depended on cultural norms included what/where to eat, who decides and controls on family menus. Social factors included family economic status, access and availability of food stuffs and spaces for physical exercise. Moreover, differences in age and gender-determined capacity for food choice and access to physical activity were described as being both socially and culturally determined.

We eat together as a family

Both caregivers and adolescents reported that parents dictated adolescents’ diet, and as is the custom in Ethiopia, adolescents often ate their daily meals from the same plate as the rest of the family. Caregivers decided the menu at home, and adolescents were not allowed to prepare separate meals for themselves. Generally, it was accepted, as part of Ethiopian culture, that:

…food for the whole family is prepared together and all the family members eat from the same plate. (Older girl, FGD 1)

The purpose of this shared food preparation and consumption was to save time, labour, cost and resources:

the responsibility to prepare food in the household is on the shoulder of my mother. You can imagine how much time she needs to prepare different food for children, adolescents and adults …three times a day. So she prepares the meal together and [it is] shared from the same plate. (Older boy, FGD 4).

As parents have the authority to decide on the constituents of the family meals, the availability and variety of food for adolescents are mainly influenced by the family. Although adolescents felt that their diet was strictly dictated by their parents, caregivers felt that contemporary adolescents were much harder to ‘control’ than they used to be:

At this time compared to decades ago, it is becoming very difficult to control and manage adolescents eating habits, as adolescents are getting out of family control. (Mother, FGD6)

Parents were worried that this lack of control would result in children being exposed to unhealthy foods, like street and fast foods, and that this could have a negative influence on their weight and health. From all of the caregiver’s FGD, it was understood that older adolescents were more challenging and more likely than younger adolescents to challenge their parents over diets in favour of independent choices:

These days our adolescents are focusing on packaged food, chips and sweet things outside home. (Father, FGD 8)

In these circumstances, some of the older boys described making food choices which were driven by taste, colour and appearance of the food, rather than nutritional value. They also described how certain foods made them feel good:

It is my psychological response aroused from the taste of the food as well as satisfaction, and my drive to look for and eat some specific food items (older boy, FGD 4)

We eat what we can afford

Participants described family economic status as a strong driving force in determining adolescent diet. Generally, parents were influenced by the affordability and accessibility of certain foods when deciding what to cook for their families. Adolescents wanted a more varied diet, and mothers wanted to provide this for their children, though many felt that they did not have the financial capacity to do so:

I think when they grow-up, their needs become greater, but it depends on whether we can afford that or not. If we afford we can provide, if not, we can’t do anything. (Mother, FGD 6)

The mothers told a story of financial struggle, where they were, in some cases, unable to afford the very basics such as water for their families:

If you can afford it, you will be motivated to prepare different foods. Sometimes we can’t even afford to buy a single jerrican of water. (Mother, FGD 7)

The adolescents echoed this story. To be able to purchase foods outside of the family home, they had to work for the money:

I might want to eat meat but I might not afford it. So our economy decides…Rather I have to work hard to get money. (Older girl, FGD 3)

How can I let my daughter play outside with strangers?

Physical activity opportunities were heavily influenced by gender. Girls’ physical activity was primarily domestic work, whereas boys had the opportunity to participate in outdoor games. Younger boys ran and played football, while older boys joined centres for physical fitness and played in structured sport zones and clubs. The gaining of physical strength, maintaining good physical, mental and psychological health/wellbeing and socialising with peers were described by the boys as their main motivations for engaging in physical activity:

Those who do exercise will be well and strong. (Younger boy, FGD 2).

In contrast, despite wanting to play and exercise, adolescent girls were often restricted in relation to physical activity opportunities. They were often not permitted to leave the home, which obviously inhibited their use of outdoor spaces, and were aware of the contrast with boys’ experiences:

We want to do physical activity in school and use sports facilities in our leisure time. However our parents are very controlling and do not allow us to go outside of home for physical activity. So we don’t have the opportunity to be as physically active as our brothers. (Older girl, FGD 1)

Parents were fearful of permitting their daughters to share overcrowded outdoor spaces with strangers. They were deeply worried about their daughters’ safety, articulating very clearly this was the main reason for restricting their outdoor physical activity opportunities:

How can I send out my daughter to the field for the sake of exercise while there are mixtures of different people with good and bad character at the field who may take advantage of girl adolescents?… We see and fear that our daughters will be sexually exploited, abused or easily influenced with wrong information.… So unless there is a separate and safe place for girls, it remains difficult to send our daughter outside for exercise although we believe that the exercise is important. (Mother FGD 6)

Girls were therefore much more likely to report engaging in sedentary activities in their spare time, including sitting and watching movies and television programmes, as well as helping their mothers with domestic household activities.

Suggestions to improve adolescent nutrition and physical activity

Although the adolescents demonstrated good nutritional and health-based knowledge, when asked what interventions could help to improve adolescent diet and physical activity, they proposed school-based education, media information campaigns and home-based health information, communication and education:

Advice should have to be given. Especially for street children, training materials should have to be given for them. (Younger boy, FGD 2)

Parents, on the other hand, seemed unaware of their adolescents’ nutrition knowledge, suggesting that health education and communication programmes were needed to provide adolescents with the right information about nutrition to prevent them from consuming junk, fast and street foods. Community-based interventions to change attitudes and perceptions were suggested to improve opportunities for physical activity. Moreover, caregivers recommended the need for separate exercise areas for boys and girls, while older girl adolescents proposed health communication and information to change community attitudes towards physical activity or exercise. Adolescents also suggested that harnessing adolescents’ desire for good physical appearance would be effective in encouraging physical activity:

Men mainly spent their time on exercise but the problem is on girls, so you have to give advice on it by relating it with having good body posture. (Older girl, FGD 3)

Discussion

The aim of this qualitative study was to explore, from the perspectives of adolescents and caregivers in Jimma, Ethiopia, influences on adolescent diet and physical activity. Adolescents displayed a holistic understanding of health, nutrition and physical activity. A range of social, economic and cultural factors were perceived to be the key drivers of adolescent diet and physical activity (Table 4). One previous qualitative study of influences on the diets of adolescents in Ethiopia has been published.(Reference Mates and Khara15) This study explored the impact of socio-economic status on food insecurity in rural Ethiopia. Research presented in this paper is therefore the first to explore influences on adolescent nutrition and physical activity in urban settings in Ethiopia, from the perspectives of adolescents and their caregivers.

Table 4 Summary of main themes identified in the focus group discussions

Adolescence is a key period of rapid growth and development which increases the demand for energy and nutrition(Reference Blum, Astone and Decker19). Addressing the nutritional needs of adolescents contributes to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 2 ‘Zero Hunger’, ending malnutrition by 2030. Understanding the perspectives of adolescents in relation to diet and physical activity is therefore vital if the intergenerational cycle of malnutrition and poor health is to be broken(Reference Mates and Khara15). In this study, adolescents reported that their diet was primarily dictated by their parents and they usually ate from the same plate as their family. A number of studies from high-income countries show that adolescents and young adults spend majority of their meal times with family(Reference Larson, Fulkerson and Story20-Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Larson and Fulkerson26). Whether it is from sharing meal times or food from the same plate, family meals are important because across all cultures they are associated with adolescents’ increased intake of nutritional food(Reference Larson, Fulkerson and Story20-Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Eisenberg and Fulkerson23,Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Larson and Fulkerson26) . Shared meals increase the likelihood of achieving national dietary recommendations(Reference Larson, Fulkerson and Story20). In addition, sharing meals from the same plate as their family may also have a positive effect on the psychosocial well-being of adolescents(Reference Neumark-Sztainer, Larson and Fulkerson26). However, sharing meal could affect adolescents’ wish to decide on their own choice of food.

Adolescents demonstrated good knowledge of the health benefits of a nutritious diet and regular physical activity. Research from both middle-income (Botswana) and high-income settings (USA) indicates that adolescents understand the benefits of good nutrition(Reference Brown27,Reference Croll, Neumark-Sztainer and Story28) . This study expands on this by showing that adolescents have a holistic understanding of health, including psychological well-being in their definitions. Despite good nutritional knowledge, the adolescents continued to consume junk food, a contradiction that might be explained by developmental theory. Adolescents may be less able to resist the temptations of highly palatable and socially desirable junk food than adults because they are hyper-sensitive to emotional and social influences and prioritise the immediate over the long term(Reference de Vet, de Wit and Luszczynska29). Moreover, other values such as food preferences and peer influence are given higher priority in health(Reference Bassett, Chapman and Beagan30). In addition, there are a complex set of social and environmental factors influencing adolescents’ health behaviours(Reference Verstraeten, Leroy and Pieniak8). In this study, there was a conflict between parental control over food and adolescents’ desire for autonomy. Parental decisions over family meals, however, prevailed due to limited resources and lack of adolescent purchasing power.

Opportunities for physical activity were heavily influenced by gender. Girls’ physical activity was primarily domestic work, whereas boys had more freedom and opportunity to participate in outdoor games. Studies in high-income settings also show that girls’ physical activity declines as they progress through adolescence(Reference Dumith, Gigante and Domingues31). In LMIC, this may be compounded by a culture of removing girls from public spaces as they become sexually mature. Adolescent girls in this study were not permitted the same level of freedom to use outside spaces as boys. Parents were particularly concerned for the safety of their daughters, not wanting them to engage with boys and men, through fear that they would be sexually exploited. Anthropometric data from the survey indicated that amongst adolescents in Jimma, only the girls demonstrated levels of both stunting and obesity. This hints at gender disparities in intra-household food allocation as well. This is a phenomenon widely documented in South Asia but not so frequently commented on in studies from Africa(Reference Harris-Fry, Shrestha and Costello32).

Cognisant of adolescence as a window of opportunity to break the intergenerational effect of malnutrition, policies and programmes is giving more emphasis to adolescent health and nutrition than before. Different national and international policies and recommendations are being formulated for improving adolescent nutrition. The national strategy for adolescent and youth health in Ethiopia recommends supporting adolescent participation and leadership in the planning and implementation of programmes for adolescent health and nutrition, enhancing innovative health education and prevention programmes using mass media, health extension programmes, schools and digital technologies.

Specific interventions in this national strategic plan include improving dietary diversity and balance, with an emphasis on locally available and iron-rich foods, promoting healthy dietary habits, imparting knowledge of the intergenerational effects of malnutrition, sensitising the community to gender bias in food distribution in the household, iron-folic acid supplementation, scaling-up facility-based nutrition assessment and counselling and advocacy and promotion of food fortification.

There are, however, challenges to developing effective, context-specific interventions such as the lack of empirical evidence and absence of the adolescent voice in considerations of what might be done to improve adolescent nutrition(Reference Mates and Khara15). This study addresses this gap by asking adolescents and parents what interventions they would recommend. Globally, WHO suggests that current missed opportunities in adolescent health and nutrition include intervention through schools, mass media and other sectoral interventions such as through health services(33). Our findings show that adolescents in Jimma do not just need information on how to improve nutrition and physical activity opportunities; they are already knowledgeable and understand the health benefits. A strategy is required which enables them to convert knowledge into practice. Moreover, adolescents need resources and support from parents and the community to develop healthy lifestyle habits in terms of diet and physical activity.

Strengths and limitations

The use of qualitative methods enabled the exploration of adolescent nutrition and physical activity from the perspectives of adolescents themselves and their caregivers in Jimma, Ethiopia. By using FGD, adolescents were able to share and discuss their experiences within one another. Also, being conducted within the communities that participants lived encouraged them to feel at ease. By using direct quotes in the report, the adolescent voice has been heard and given prominence. The current study provides new insights into the perspectives of adolescents and their caregivers. Although adolescents have a good understanding of health, their diet and physical activity behaviours are not health focused but are instead heavily influenced by their families, SES status and gender. Our findings can be used to inform the development of much needed, effective interventions to improve adolescent nutrition. A collaborative approach was taken to this research, pooling expertise to ensure that high-quality data were generated and that the approach to interpretation and analysis was robust.

Implication of the findings

In summary, despite adolescent’s good understanding and knowledge of the benefits of improved nutrition and increased physical activity, their diet and physical activity behaviours were not health driven. Instead, they were greatly influenced by developmental stage, gender disparity, socio-economic and cultural factors, suggesting the need for multifaceted interventions to target these areas if we are to improve their nutritional status. Both parents and adolescents reflected the need to improve adolescents’ nutritional status and opportunities for physical activity. In line with WHO recommendations, study participants suggested the use of mass media, school or community-based health information and communication programmes as a means for change(6). The current study addresses the need to identify ways of developing effective interventions to improve adolescent health in LMIC, also currently part of the WHO’s agenda. These findings indicate that adolescents are key agents and have a crucial role to play in improving the health and nutrition of their own and the next generation. Programmes and policies need to involve them in designing and developing interventions. The findings also highlight the need to involve parents in the co-design and implementation of programmes.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The researchers would like to thank the participants of the current study volunteering and for devoting their time to the study, Jimma University for facilitating the local arrangements and the TALENT collaboration for supporting the study technically. Financial support: The current study was funded by a Global Challenges Research Fund/Medical Research Council pump priming grant (grant no. MC_PC_MR/R018545/1). The funders had no involvement in the design, implementation, analysis or decision to prepare a manuscript or to publish the finding. Conflict of interest: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest. Authorship: M.A. and R.A. have collected, transcribed and translated the data. M.A., R.A. and A.W. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors had reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript. P.H.J., S.W., M.B. and C.F. had supported the data analysis. C.F. was the principal investigator of the overall project, A.H. was the principal investigator and M.A. was lead researcher for the local (Jimma) study. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The current study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the institutional review board of Jimma University (ID no. IHRPGO/406/2018). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020001664