1.1 Introduction

Most people who regularly use the Internet will be familiar with words like “misinformation,” “fake news,” “disinformation,” and maybe even “malinformation.” It can appear as though these terms are used interchangeably, and they often are. However, they don’t always refer to the same types of content, and just because a news story or social media post is false doesn’t mean it’s always problematic. To add to the confusion, not all misinformation researchers agree on the definition of the problem or employ a unified terminology. In this chapter, we discuss the terminology of misinformation, guided by illustrative examples of problematic news content. We also look at what misinformation isn’t: What makes a piece of information “real” or “true”? Finally, we’ll look at how researchers have defined misinformation and how these definitions can be categorized, before presenting our own definition. Rather than reinventing the wheel, we’ve relied on the excellent definitional work by other scholars. Our working definition is therefore hardly unique; we and many others have used it as a starting point for study designs and interventions. We do note that our views are not universally shared within the misinformation research community. We can therefore only recommend checking out other people’s viewpoints with respect to how to define the problem of misinformation or related terms such as fake news, disinformation, and malinformation (Altay, Berriche, et al., Reference Altay, Berriche and Acerbi2022; Freelon & Wells, Reference Freelon and Wells2020; Kapantai et al., Reference Kapantai, Christopoulou, Berberidis and Peristeras2021; Krause et al., Reference Krause, Freiling, Beets and Brossard2020; Lazer et al., Reference Lazer, Baum, Benkler, Berinsky, Greenhill, Menczer, Metzger, Nyhan, Pennycook, Rothschild, Schudson, Sloman, Sunstein, Thorson, Watts and Zittrain2018; Pennycook & Rand, Reference Pennycook and Rand2021; Tandoc et al., Reference Tandoc, Lim and Ling2018; Tay et al., Reference Tay, Hurlstone, Kurz and Ecker2021; Vraga & Bode, Reference Vraga and Bode2020; Wardle & Derakhshan, Reference Wardle and Derakhshan2017).

1.2 Fake News, Misinformation, Disinformation, Malinformation…

On the surface, “misinformation” seems easy to define. For instance, you might say that misinformation is “information that is false” or tautologically define fake news as “news that is fake.” Or, to use David Lazer’s more comprehensive phrasing, fake news is “fabricated information that mimics news media content in form, but not in organisational process or intent” (Lazer et al., Reference Lazer, Baum, Benkler, Berinsky, Greenhill, Menczer, Metzger, Nyhan, Pennycook, Rothschild, Schudson, Sloman, Sunstein, Thorson, Watts and Zittrain2018, p. 1094). An example of a news story that would meet Lazer’s definition is a hypothetical headline from www.fake.news that reads “President drop-kicks puppy into active volcano.” This headline is false (that we know at least), and www.fake.news mimics news content but is not universally considered to be a trustworthy source of information (and presumably doesn’t follow the ethical guidelines and editorial practices used in most newsrooms). Many would also agree that this headline may have been written with malicious intent in mind (assuming the authors weren’t joking): If someone were to believe it, they would be left with an inaccurate perception of another person, in this case the president, which might inform their decision-making (e.g., leading them to vote for somebody else or disengage from the political process altogether). However, things aren’t always this straightforward: Not only is it sometimes difficult to discern what is true or false, but true information can also be used in a malicious way, and false information can be benign and sometimes hilarious. Take, for example, the headline from Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Example of a false but relatively harmless news headline (The Onion, 2012).

The Onion is an American satirical news site that publishes humorous but false stories which mimic regular news content. The rather wonderful part about this specific story is that the online version of the People’s Daily, the Chinese Communist Party’s official newspaper, apparently believed that it was real, and reposted the article along with a fifty-five-page photo reel of the North Korean leader (BBC News, 2012). But despite the story being entirely false, it was benign, even though some people believed it (though we recognize some feelings may have been hurt when people found out that Kim Jong-Un wasn’t named 2012’s sexiest man alive). If anything, the ability to make fun of powerful people through satire is often seen as a sign of a healthy democracy (Holbert, Reference Holbert2013), and as far as satire goes the Onion story was rather mild.

At the same time, false information is not always benign, nor does it always try to mimic regular news content. Figure 1.2 shows an example of a Facebook post which got quite a bit of traction in 2014 and again in 2016.

Figure 1.2 Example of a false and malicious social media post (Snopes, 2016).

The post is associated with #EndFathersDay, a fake hashtag movement started by members of the 4chan message board some time in 2014. Some 4chan users wanting to discredit feminist activists came up with a talking point that they thought would generate significant outrage and tried to get it trending on Twitter (Broderick, Reference Broderick2014). These kinds of artificial smear campaigns imitate the language and imagery of a group in order to bait real activists and harm their credibility. The image from Figure 1.2 was manipulated to make it look like there were women on the streets protesting for the abolition of Father’s Day. But if you look closely, you’ll see that the image was photoshopped. The demonstration where the original picture was taken was about something entirely unrelated. Nonetheless, this post is an example of how easy it is to manufacture outrage online using very simple manipulation tactics. Its creators didn’t even have to bother setting up a “news” website to spread their content or mimic media content in form: All they had to do was photoshop a picture of a demonstration and spread it on social media.

To add another layer of complication, the intent behind the production of (mis)information also matters a great deal. It can happen that someone creates or spreads misinformation unintentionally (analogously to a virus spreading among asymptomatic people). For example, a journalist could write a news article fully believing it to be true at the time, only for the information in the article to later turn out false. Simple errors can and do happen to the best of us. Similarly, someone may share something on social media that they either erroneously believe to be true or don’t believe but share anyway because they’re distracted (Pennycook & Rand, Reference Pennycook and Rand2021). Oftentimes, however, misinformation is produced intentionally. In February 2022, just after the start of the Russian invasion in Ukraine, Melody Schreiber at the Guardian noticed a drop-off in the activity of Twitter bots that were spreading misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines (Schreiber, Reference Schreiber2022). The reasons behind this reduced activity were varied, but it appears that a significant number of Twitter bots that were spreading COVID-19 misinformation were run from within Russia. These bots went dormant for a while, but soon became active again to pivot their attention away from COVID-19 and toward the war in Ukraine. Building a Twitter bot and programming it to spread misinformation takes some time, effort, and money, and it’s reasonable to assume that the people who created the bots intended for them to spread false and misleading information. This type of deliberate, organized misinformation is often referred to as disinformation (Dan et al., Reference Dan, Paris, Donovan, Hameleers, Roozenbeek, van der Linden and von Sikorski2021; Freelon & Wells, Reference Freelon and Wells2020). What this phenomenon also shows is that a substantial amount of misinformation on social media may be not only inorganic (spread by bots rather than real humans) but also topic-agnostic: The topics about which misinformation is spread can be contingent on what happens in the world (such as a pandemic or a war), rather than being driven by a public demand for misinformation content.

In the earlier examples, it’s arguable that the producer’s intent behind the misinformation was malicious: for example, by getting people to doubt the safety and efficacy of vaccines (Loomba et al., Reference Loomba, de Figueiredo, Piatek, de Graaf and Larson2021). Similar to the Kim Jong-Un story from before, however, it is also possible for intentional misinformation to have benign motivations behind it. For instance, in the early days of the Russian invasion in Ukraine in February 2022, stories began to circulate about a mystical fighter pilot, the “Ghost of Kyiv,” who was said to have single-handedly shot down six Russian planes during the first night of the invasion. The Ukrainian ministry of defense even tweeted a video in celebration of the pilot’s alleged heroism. The “Ghost” thus became a symbol of Ukraine’s heroic resistance against a much larger invading force. Later on, however, the Ukrainian Air Force Command admitted on Facebook that the story was nothing more than war propaganda: The “Ghost” was a “superhero-legend” who was “created by the Ukrainians.” The Facebook post even urged Ukrainians to check their sources before spreading information (L. Peter, Reference Peter2022). However, although the story was a deliberate lie, the motivations behind its creation are arguably defensible: It served as a rallying cry and morale booster during a time when it looked like Ukraine was about to be overrun and capitulation seemed imminent (Galey, Reference Galey2022). This isn’t to say there were no negative consequences. For example, the story may have increased distrust in the accuracy of Ukraine’s reports about its performance on the battlefield (although we don’t know this for sure). Also, people who don’t support Ukraine are probably less likely to agree that the lie was benign, and even some pro-Ukrainian commentators might not find it all that defensible. Here, again, the complexities behind a seemingly straightforward question like “what is misinformation?” become visible: Intentional lies are often malicious, but not always, and the motivations behind the deliberate creation of misinformation can sometimes be understandable from a certain point of view. All of this leaves us with the following possibilities when it comes to false information:

| Intentional | Unintentional | |

|---|---|---|

| Malicious |

|

|

| Benign |

|

|

This is already a complicated categorization, but it gets worse: Some types of content are not false but can nonetheless fall under a reasonable definition of “misinformation.” We discuss this “real news problem” in the next section.

1.3 The Problem with “Real News”

Just like with misinformation, defining “real news” seems easy but isn’t. After all, isn’t real news simply “novel information that is true?” In many cases, this definition is reasonable: Statements such as “the earth is a sphere” and “birds exist” are seemingly uncontroversial and verifiable with a wealth of empirical evidence.Footnote 1 And indeed, many news headlines are unambiguous: “Parliament passes law lowering taxes on middle incomes,” “Senator from Ohio supports Ohio sports team,” “China–Taiwan tensions on the rise,” and so on (we made these specific headlines up, but you get the point).

However, there are several considerations that offer nuance to such a seemingly simple problem. What counts as “true” is often contested, particularly in the context of politics (Coleman, Reference Coleman2018). Former White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer was widely mocked in early 2017 for asserting that US President Donald Trump’s inauguration ceremony had “the largest audience ever to witness an inauguration, period, both in person and around the globe” (Hunt, Reference Hunt2017), despite footage clearly showing that more people were in attendance for Barack Obama’s inauguration in 2009 (see Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Comparison between Trump’s (2017, left) and Obama’s (2009, right) inauguration attendance. Photos released by the US National Park Service (Leopold, Reference Leopold2017; National Park Service, 2017).

When pressed, Spicer stood by his claims, insisting that Trump’s inauguration was the “most watched” in US history. He asserted that he had never meant to imply that the in-person ceremony had a higher attendance than Obama’s, but rather that the overall audience (including television and online) was the largest ever (Gajanan, Reference Gajanan2017). Whether Spicer was correct or incorrect in his original comments is therefore ambiguous: What does “witness” mean in this context? What did Spicer mean by “both in person and around the globe”? That both the number of people attending in person and the number of people watching the inauguration in some other way were the highest ever (which would mean his initial comments were incorrect), or was he talking about both numbers added together? And did Spicer already have both online and television audiences in mind when he made his original comments, or did he later realize he messed up and only afterward thought of it as a possible defense? In the absence of objective answers, what you believe to be true probably depends to some extent on your personal beliefs: It’s safe to say that Spicer’s political opponents are less likely to accept his explanation than his supporters. In other words, what counts as true can sometimes (but certainly not always) depend on your perspective;Footnote 2 this phenomenon of political or emotional considerations overriding a calculated assessment of the evidence is called motivated reasoning (Van Bavel et al., Reference Van Bavel, Harris, Pärnamets, Rathje, Doell and Tucker2021), which we will get back to in Chapter 4.

A second problem with “real news” is that news that is factually correct can nonetheless be misleading. A famous example of this occurred in 2021, when the news story from Figure 1.4, originally by the South Florida Sun Sentinel, went viral and was shared millions of times on social media (Parks, Reference Parks2021).

Figure 1.4 Example of a true but misleading headline that went viral (Boryga, Reference Boryga2021).

Every word in the headline is technically correct: The doctor did die, and the CDC (US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) did investigate whether his death was related to the vaccine. However, the reason this article was shared so many times was presumably not because of the headline’s factual content but rather because of what it implied: that the doctor died because he got vaccinated. However, as the Chicago Tribune now notes at the top of the article, “a medical examiner’s report said there isn’t enough evidence to rule out or confirm the vaccine was a contributing factor.” You wouldn’t know this just from reading the headline, however; it’s fair to say that the headline is at the very least misleading (employing the correlation = causation fallacy) despite being factually correct and published by a legitimate news source. But while the Chicago Tribune story may have been accidentally misleading, this isn’t always the case: Malinformation is information that is true or factual, but intentionally conveyed in such a way that it may cause harm or pose an imminent threat to a person, organization, or country (Wardle & Derakshan, 2017).

Another, perhaps more practical way to define “real news” is through source credibility: One can assume that a news story is true if it was published by a legitimate source. And indeed, some news outlets have (much) higher quality standards than others, so as a heuristic (a rule of thumb) it isn’t a bad idea to rely on prior knowledge about the credibility and trustworthiness of the source of a story. However, even credible outlets sometimes publish information that’s misleading (such as in the example from Figure 1.4) or outright false.Footnote 3 As we discuss in Chapters 2 and 3, misinformation coming from reliable or trusted sources can potentially have serious consequences. Also, an underlying assumption here is that traditional media operate independently from the government. This is the case (or tends to be) in democracies, but not so much in autocratic and semi-autocratic countries, where the most credible sources are often not part of the mainstream media.

Furthermore, in many cases you don’t know a source’s credibility. A lot of social media content is spread by individuals, not news outlets, and it’s difficult to know whether any given person tends to share reliable information. Platforms such as YouTube also feature thousands of content creators who discuss politics and world events, and despite their non-status as traditional media outlets, they can (but don’t always) produce high-quality news and opinion content. Dismissing such creators as untrustworthy simply because they aren’t a television channel, newspaper, or news site is not entirely reasonable. You could argue that established media sources have editorial practices in place that make the source generally more reliable (and are often better than the alternative), but nonestablished media channels can also give a voice to people who are underrepresented in more traditional media, which can in some cases be problematic but in other cases enriches public debate.

To complicate matters even further, scientific research is generally speaking subject to rigorous peer review and many types of quality checks before publication, and scientists are trained to disregard their personal biases as much as possible. But at the same time, there are high-profile examples of scientific fraud and questionable research practices, and the “replication crisis” has cast doubt on quite a few findings that we used to believe were robust. Does this mean that science is therefore unreliable? The answer is no; healthy skepticism can be productive, and at the same time blind trust in any scientific finding is probably not too helpful. But the scientific method, with all its built-in checks and balances, remains an excellent way to arrive at robust conclusions that hold up to independent scrutiny, even if it isn’t (and can never be) foolproof.Footnote 4

1.4 Defining Misinformation

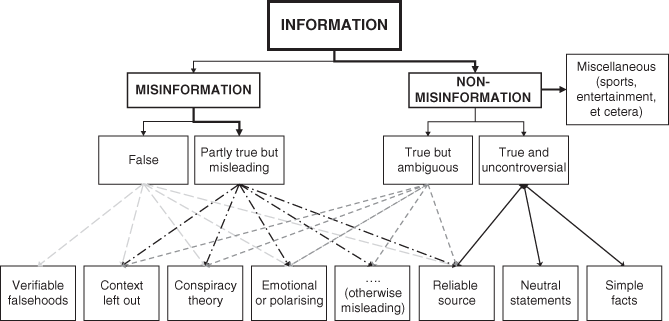

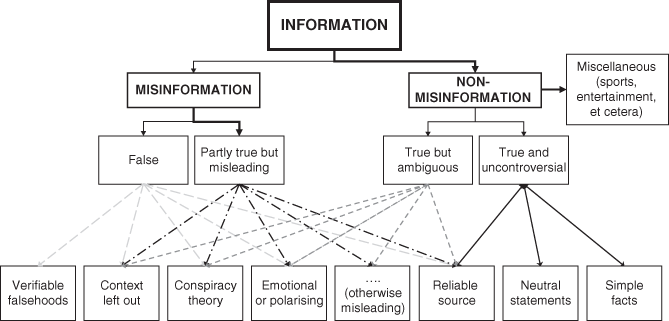

Although misinformation and “real news” may sound easy to define, people often disagree over what’s true and what isn’t, true information can nonetheless be presented in a misleading way, and relying on source credibility is often helpful but certainly not always. To illustrate this further, see Figure 1.5, which shows a flowchart to help distinguish between misinformation and non-misinformation.

Figure 1.5 A flowchart for defining misinformation and non-misinformation.

Note: Thicker arrows mean that type of content is likely to be more common: Non-misinformation is more common than misinformation, miscellaneous content is more common than news content, and misleading information is more common than information that is verifiably false (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Howland, Mobius, Rothschild and Watts2020; Grinberg et al., Reference Grinberg, Joseph, Friedland, Swire-Thompson and Lazer2019). We recognize that the four categories of misinformation and non-misinformation shown here are not mutually exclusive, and it’s not always clear which category best applies to a given piece of content. See also Chapter 8.

As the figure shows, classifying something as misinformation is easiest for information that is verifiably false. Most false information might be labelled “misinformation” (with some exceptions, as discussed earlier), but it can also have other cues of “misleadingness” such as missing context, conspiracist ideation, or a high degree of (negative) emotionality.Footnote 5 At the other end of the spectrum we have information that is both true and uncontroversial (such as the fictitious “Senator from Ohio supports Ohio sports team” headline from earlier). This can include simple facts, neutral statements, or factual news headlines from reliable sources. All relatively uncontroversial; so far, so good.

Our problems start when we look at the overlap between misleading but partly true misinformation and true but ambiguous non-misinformation. A good example is the headline from Figure 1.4 (about the doctor dying after receiving a COVID-19 vaccine). It’s arguably misleading because many people (probably) inferred a wrong conclusion from the headline, but is it misinformation? Two reasonable people might give different answers to this question. As Figure 1.5 shows, misleading information and ambiguous non-misinformation can (but don’t always) share features that can be seen as signs of manipulation or dubious argumentation, such as a (formal or informal) logical fallacy, a high degree of (negative) emotionality, a lack of context, a conspiracy theory, or a personal attack (Piskorski et al., Reference Piskorski, Stefanovitch, Nikolaidis, Da San Martino and Nakov2023). This makes the distinction between (some kinds of) misinformation and non-misinformation fuzzy and subjective.

To give an example, moral-emotional language is a known driver of virality on social media (Brady et al., Reference Brady, Wills, Jost, Tucker and Van Bavel2017), and emotional storytelling is often used by people who are seeking to spread doubts about vaccine safety (Kata, Reference Kata2010, Reference Kata2012). Does this therefore mean that any news headline that uses moral-emotional language is misinformation? Of course not: (Negative) emotions can be and often are leveraged to lead people to false conclusions, but they can also be used for benign purposes (think of charity drives or some political appeals). At the same time, you could argue that a claim that includes an emotional appeal (e.g., “Trump’s racist policies have horribly devastated the USA”) is of lower epistemic quality than the same claim phrased in a more neutral fashion (e.g., “Trump’s policies have negatively impacted US race relations”), assuming that the goal is to inform but not necessarily persuade message receivers. But here we’re talking about epistemic quality and not necessarily truth value, and so the label “real news” may not be very helpful.

The same goes for conspiratorial reasoning: Some conspiracy theories later turn out to be true, and in some cases it can be reasonable to suspect that a conspiracy might be happening even when not all of the facts about an event are known. However, true conspiracies tend to be uncovered via “normal” cognition and critical thinking (e.g., the mainstream media reporting on Watergate), whereas most popular conspiracy theories are not only statistically implausible (Grimes, Reference Grimes2016) but also fall prey to predictable patterns of paranoid suspicion and conspiratorial reasoning (Lewandowsky et al., Reference Lewandowsky, Lloyd and Brophy2018). Then again, it’s also true that some conspiracies are misinformation even if their objective veracity can’t be determined (like how you can’t know for sure that psychologists didn’t invent mental illness to sell self-help books – it’s just that this is very likely to be false).

This discussion has substantial implications for when you want to start fighting misinformation: So do you only focus on “fake news” (as some scientists have done) or do you also include misleading information? If the latter, how do you define “misleading”? And how does your definition inform how you design your intervention? We return to this discussion in Chapters 6–8.

In the end, all of this might mean that an objective definition of misinformation that satisfies every observer is impossible, as there’s an inevitable degree of subjectivity to what should and shouldn’t be labelled as misinformation or “real news.” However, this doesn’t mean that we should simply give up: After all, some examples of misinformation are unambiguous, and as we will see later in this book, we don’t need a universally agreed upon definition as a starting point for intervention.

So with that being said, we have to start somewhere. Over the years, many researchers have attempted to arrive at a definition of misinformation that takes into account the complexities described earlier (Freelon & Wells, Reference Freelon and Wells2020; Kapantai et al., Reference Kapantai, Christopoulou, Berberidis and Peristeras2021; Krause et al., Reference Krause, Freiling, Beets and Brossard2020; Lazer et al., Reference Lazer, Baum, Benkler, Berinsky, Greenhill, Menczer, Metzger, Nyhan, Pennycook, Rothschild, Schudson, Sloman, Sunstein, Thorson, Watts and Zittrain2018; Roozenbeek & van der Linden, Reference Roozenbeek and van der Linden2022; Tandoc et al., Reference Tandoc, Lim and Ling2018). These definitions tend to fall under one of these four categories, or combine several of them:

Veracity-focused: Content can be classified as misinformation if it has been fact-checked and rated false, or if it goes against established scientific or expert consensus (Lewandowsky & Oberauer, Reference Lewandowsky and Oberauer2016; Pennycook & Rand, Reference Pennycook and Rand2019; Tay et al., Reference Tay, Hurlstone, Kurz and Ecker2021).

Source-focused: If a story or claim comes from a source that is known to be unreliable (e.g., www.fakenewsonline.com), it’s more likely to be misinformation (Pennycook et al., Reference Pennycook, Epstein, Mosleh, Arechar, Eckles and Rand2021).

Intention-focused: Misinformation is content is produced with a clear intention to manipulate or mislead, for example in the case of organized disinformation campaigns (Eady et al., Reference Eady, Pashkalis, Zilinsky, Bonneau, Nagler and Tucker2023; Silva et al., Reference Silva, Giovanini, Fernandes, Oliveira and Silva2023).

Epistemology-focused: Content can be classified as misinformation if it is epistemologically dubious, for example by making use of a documented manipulation technique or logical fallacy (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Lewandowsky and Ecker2017; Piskorski et al., Reference Piskorski, Stefanovitch, Nikolaidis, Da San Martino and Nakov2023; Van der Linden, Reference Van der Linden2023).

Each of these approaches has benefits and drawbacks. Veracity-focused definitions are more or less objective (because the veracity of a claim can sometimes be objectively established), but don’t incorporate content that’s misleading or otherwise manipulative (which is much more common than verifiable falsehoods). Source-focused definitions avoid the complications of establishing veracity but neglect the fact that unknown sources can provide high-quality information and high-quality sources can sometimes spread misinformation. Intention-focused definitions establish a clear motivation behind why content is produced but don’t account for the fact that the intentions of content producers can be hard and sometimes impossible to discern. And finally, epistemology-focused definitions retain a degree of objectivity without the burden of having to establish veracity, but the boundaries of what counts as misinformation (and what doesn’t) become fuzzy (see Figure 1.5). In practice, scientists are faced with constraints: for example, because they need to make choices about study design or what types of social media content they manage to get a hold of; sometimes the definition of misinformation used in a study depends on practical considerations more than theoretical ones.

Throughout this book, we will be talking about a range of news and social media content (along with other types of information) that we consider to fall under the “misinformation” umbrella, which requires us to establish what types of content we have in mind when we use this term. In our view, source-based and intention-based definitions are a bit too narrow. As we will see in Chapters 2 and 3, sources that are ostensibly of very high quality can sometimes become the source of highly impactful misinformation. Also, the intentions behind why a piece of misinformation was produced are often guesswork and can only be reliably discerned in relatively few cases. Finally, focusing on veracity alone fails to capture the (likely much larger) amount of problematic content that is not explicitly false. We will therefore use a definition that is both veracity- and epistemology-focused:

Misinformation is information that is false or misleading, irrespective of intention or source.

By “false or misleading” we mean that misinformation can be provably false as well as misleading (e.g., because important context is left out) or otherwise epistemologically dubious (by making use of a logical fallacy or other known manipulation technique). This allows us to incorporate both content that is verifiably false and content that is otherwise questionable (Piskorski et al., Reference Piskorski, Stefanovitch, Nikolaidis, Da San Martino and Nakov2023); in our view, lying is but one way to mislead or manipulate people; clever misinformers often don’t need to lie to get what they want. Importantly, we’re careful to not only focus on news content or content that is produced by media outlets, but rather to include any form of communication through which misinformation might spread (including, for example, content produced by regular social media users). As we will see, this definition captures a wide range of problematic content, while not accidentally flagging too much legitimate content as misinformation. Our definition is also in line with much of the rest of the research field. One study in which 150 experts were asked how they define misinformation found that “false and misleading” information was the most popular definition among experts, followed by “false and misleading information spread unintentionally” (Altay et al., Reference Altay, Berriche, Heuer, Farkas and Rathje2023). However, it also has several shortcomings. For instance, some statements are misleading even if no known manipulation technique is used. Without a comprehensive definition of “misleading” or “manipulative,” our definition is therefore also imperfect.Footnote 6

1.5 Conclusion

In this chapter we’ve given our perspective on how to define misinformation, drawing on the literature that has been published on this matter in recent years. False information can be created and shared for benign as well as malicious reasons, and shared both intentionally and unintentionally. Also, misinformation can sometimes be misleading but not outright false, but it can be very difficult to objectively determine whether information is misleading. We’ve therefore argued that defining misinformation is more complicated than focusing on whether a piece of information is true or false, and that the intent behind the creation of (mis)information matters but can’t always be accurately discerned. We’ve also tried to tackle the problem of defining “real news”: Whether something is true is often up for debate, particularly in the context of politics. With this discussion in mind, we have proposed our own definition of misinformation, which we will use throughout this book: Misinformation is information that is false or misleading, irrespective of intention or source. Of course, this definition kicks the can down the road a bit, as we, for example, haven’t offered a comprehensive definition of “misleading”; there are quite a few different ways to mislead people, including cherry-picking data, posing false dilemmas, leaving out context, and so on, but this kind of bottom-up approach also has its limitations. We therefore acknowledge that a degree of subjectivity is inevitable here: Not including misleading content means excluding the most impactful and potentially harmful misinformation (see Chapter 3), but it also doesn’t work to have an exhaustive list of all the different ways in which content can be presented in a misleading manner (there are simply too many). This is a difficult philosophical problem which we won’t attempt to offer a solution to here. We instead invite the reader to put their philosopher’s hat on for a while and think this matter through.Footnote 7 In the next chapter, we will discuss the history of misinformation: When did people start misleading each other? And how have technological inventions such as the printing press and the Internet affected this dynamic?