Why do the ancient Maya fascinate us so much? The field of Maya studies is filled with stories of a single site visit or artwork that changed the course of someone’s life – suddenly we must know all we can about this very foreign culture located so close to home. There are scores of Maya conferences open to the public, and magazines like National Geographic or Archaeology seem to run a story about the ancient Maya in nearly every other issue. Is it because they are mysterious and unknown? Or because they mastered a challenging tropical environment for over a thousand years? Is it that many Americans travel to Mexico and become familiar, even if only in a passing sense, with the deep history of Indigenous Mexico? Or is it simply the superb artwork and architecture of Classic Maya culture, with its graceful lines and intricate stonework? This book sets out to introduce the new student or admirer of ancient Maya society to the best approximation that current scholarship has to offer of the glorious achievements and challenges of this unique ancient society. To those who have already visited the ancient cities of the Maya scattered throughout southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras, this book will help the reader see the people who populated those wonderfully diverse and complex cities, and the countryside in between. To those who are new to this culture, I hope to share some of the excitement scholars like myself have for the rich history of Maya society, and to bring you a few steps closer to what life was like in ancient Maya times.

Nature of the Data

If you know anything about the ancient Maya you likely know that archaeologists are very fond of excavating the ancient tombs of Maya kings and queens. Every few years a new undisturbed Maya tomb with all its riches is opened from deep within a pyramid. These discoveries remind us of the sense of wonder we had as children, when the world was filled with unknown treasures from days gone by. Because the ancient Maya had a strong belief in the afterlife, like Pharaonic Egyptians they filled a royal burial with all that a royal ruler would need in the underworld – things such as ritual tools, delicious food and drink, and elaborate jewelry befitting their status – many of which were made by expert craftspeople and today are justly considered masterpieces of art. In the later chapters of this book we will explore what daily life was like for the royalty, or the ruling families, and those who surrounded them to perform courtly activities. Their palace life was filled with intrigue, luxury, and dynastic competition much as the lives of Medieval European royalty or Chinese dynastic royalty. These people created the only system of full literacy in the ancient New World, and used these hieroglyphs to commemorate their accomplishments in books and carved stone. The writing and calendrical systems of the ancient Maya are unsurpassed in ancient New World history, and the Maya are one of a handful of ancient cultures that created a fully phonetic written language like our own. Why wouldn’t these accomplishments fascinate us?

But in order for those elites to have time to learn how to read and write hieroglyphs, many, many other people had to grow the food they ate, weave fabric for their clothing, build palaces and patios where they lived, and defend their cities from often aggressive neighbors. Fortunately, in addition to excavating ancient Maya tombs, the field of Maya studies is rich in data on all these other people as well, often labeled “commoners,” and described as the vast and diverse bulk of Maya society who were not discussed in writing and had less access to resources and state power. This book will try to bring them to life also, and to show how the life of a humble farmer was interconnected with the lives of the royalty that appear much more frequently in popular media. Increasingly, we are able to discern more about the lives of the vast middle of Maya society: the bureaucrats, administrators, merchants, skilled tradespeople, architects, and healers – those who were neither royalty nor commoners (Figure 1.1). Scholars are slow to adjust their models of ancient societies, but today we acknowledge the importance of moving beyond a binary of inequality that includes only the nobles and the poor. One useful suggestion is that we relinquish “elite” and “commoner” in favor of more specific terms such as the occupational categories listed above, which better capture systematic measures of wealth, status, and power.Footnote 1

Figure 1.1 Wealthy merchant known as the “Woman in Blue,” from a Classic period mural on the Chiik Nahb structure sub 1-4, Calakmul, Mexico.

Maya studies has a vast assortment of data available, because the ancient Maya not only left written records and pyramids; they left material evidence and art that speaks to every aspect of ancient lives. We can excavate the gardens where they grew papaya and chili peppers and find evidence of those plants in the soil. Animal bones left over from daily meals and ceremonial feasts can be identified to help us know how they hunted, what they ate, and what foods held ritual significance. While royals went into death accompanied by a rich assortment of their favorite items, ancient Maya people of all social levels wore their favorite jewelry when they were buried. Often their families sent them into the afterlife with a ceramic plate or obsidian blade that helps us understand how their identity was symbolized by the tools they used every day. Archaeologists study the homes of farmers and merchants of all social levels to see how their living environment differed from (or was similar to) the lives of the elite. Art historians look for patterns in figurines found in the homes of nearly all ancient Maya people just as often as they look for patterns in elite portraiture. Epigraphers decipher hieroglyphic inscriptions and help us understand who was literate and who was not, as well as how those who held political power used writing to uphold that power. Ethnohistorians translate documents written in Maya languages from the period when Europeans first arrived in this part of the world and show how Maya people quickly adapted to new systems of authority as well as how they resisted or embraced Spanish culture. Finally, we are truly fortunate that today in Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras, millions of people speak Mayan languages and keep Maya cultural practices alive in their own 21st-century way. These modern Maya people are not a uniform culture by any means, and there are thrilling differences between what a person who speaks Maya as their native language in rural Belize or the modern city of Merida thinks, believes, and knows about Maya history. But our understanding of ancient Maya life is undoubtedly much richer because certain elements of modern Maya life, such as the value placed on corn in the diet and as a ritual food, the importance of gender-specific work in the household but also in factories or hotels, and the value of learning and speaking Mayan languages, persist today.

These manifold data speak to different ancient lives and tell different stories about the ancient people who lived in the Maya area during the Classic period (200–800 CE). For the most part hieroglyphic inscriptions and texts concern the lives of the “1 percent” – the most powerful and privileged members of society, who were fully literate and controlled tightly their access to the historical record. These texts were written for posterity, for other members of the 1 percent, and as magical incantations to attempt to control the weather, land, deities, and fortunes of each polity or dynastically ruled city-state. Art history tells us stories of the elite as well, as they controlled the production of the most elaborate and formal artistic works, but art was not only the province of the wealthy. Even members of modest households made clay figurines and personal ornaments, and there are wonderful stories hidden in crafts, such as pottery and cloth, that were made in every household. In Maya studies archaeology is the great democratizer, and the techniques of archaeological research can speak to all members of ancient Maya society, although scholars today acknowledge we have often overlooked certain populations like women, children, or elders, due to our own cultural prejudices. In short, there are many stories to tell about daily life in ancient Maya society, and no one book or analytical technique can hope to capture them all. However, by utilizing current data as skillfully as possible, and acknowledging that we do not have enough information on certain understudied groups, this volume attempts to convey a wide swath of the astounding stories available to us today about ancient Maya people. Their lives were rich and complex, full of happiness as well as stress. Some had vast material advantages over others, while some had greater freedom of movement and self-determination. This volume seeks to bring the reader closer to the actual experiences of living in Classic Maya culture by emphasizing the human experiences to which we all are subject, whether we live in an ancient city carved out of the tropical jungle or a small apartment in a contemporary urban jungle. It is not an act of fantasy to try to blur the distinctions between present and past – it can be an exercise in appreciating the common experiences all humans share while learning from the great accomplishments and failures of societies just as elaborate as our own.

The book you are reading is also shaped by my own experiences and life story. I have directed archaeological excavations in the Maya area for over thirty years, and collaborated with Yucatec Maya speakers from Yaxunah, Mexico, for most of that time (Figure 1.2). I was trained by archaeologists who worked closely with art historians and museum professionals because they had an appreciation for how profoundly art speaks to Maya cultural values. I was fortunate to have an undergraduate professor who grew up in Mexico and spent his career working at Maya cities of the Yucatan, a strong influence on my choice to center my research in the northern Maya lowlands. I am a white cis-gendered woman from a middle-class family who spent their discretionary funds on travel and would probably describe themselves as animists, taking spiritual lessons from nature. My archaeological research in the Maya area continued while I had two sons, and they accompanied me to the field. I improvised how to balance field research and parenting, and we experienced the extraordinary kindness of many Maya people and Mayanist scholars who rescued me from my improvisations. I have written about how taking my kids into the field transformed my understanding of modern Maya life, as once I had kids, Maya women felt we had a lot more in common and started talking to me about their lives. I am fortunate to teach at a university and my choices about what to include in this volume are shaped by the decades of students I have taught about the Maya and their questions about this amazing culture. I am also deeply committed to sharing the knowledge my field produces with the interested public, and through museum exhibits, public lectures, and articles I have developed a sense of what questions visitors to the Maya area ask the most. Everything I have to say about the ancient Maya is shaped by my friends and colleagues in Yaxunah.

Figure 1.2 The author excavating ceramic vessels from a burial context at Xuenkal, Mexico.

Scholars make choices about what data to utilize – even social scientists who follow the scientific method of hypothesis testing – and I consider myself one of those scientists, gravitate toward certain questions or aspects of ancient cultures. This book is the result of a conversation between my particular research interests and experiences alongside what my students and friends have wanted to know about the ancient Maya that draws on the latest and best scholarly research. I say all this to demystify the process by which archaeologists and other scholars create the depictions of ancient societies we put out into the world. My story is not the only story about ancient Maya lives and I embrace that fact.

Environmental Factors

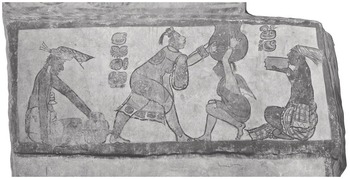

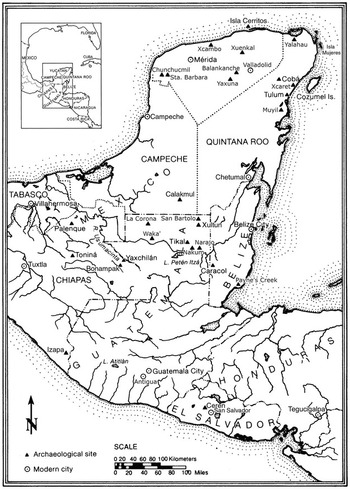

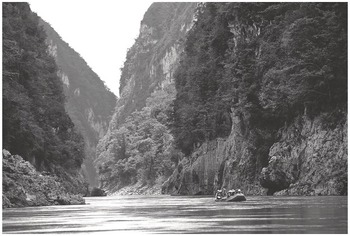

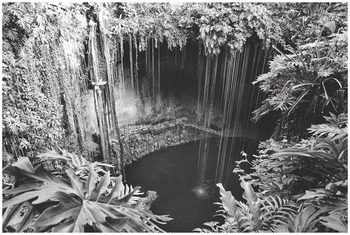

You also might know that the ancient Maya lived in the tropical rainforests, where thick vines cover pyramids and wild jaguars roam the cities. This is partly true. Another well-earned fascination with the Maya stems from their success in a challenging tropical environment. Long ago, archaeologists and other scholars of ancient history thought a complex state could not succeed in the tropical regions of the world. This misconception was based on incomplete information about the stunning accomplishments of ancient people in the tropics of Southeast Asia, the Amazon, and Mesoamerica, the area from Mexico south through Central America. Yet living in the tropics does pose many challenges, especially to a complex state facing issues such as food storage, maintenance of infrastructure, and widespread agriculture. We are still discovering how the ancient Maya managed their environments, or how they were managed by them – but by any measure it is certainly an impressive story. The Maya region is usually defined as southern Mexico: the modern states of Chiapas, Campeche, Yucatan, and Quintana Roo that make up the Yucatan peninsula; all of Guatemala and Belize; and northern Honduras (Figure 1.3). This is a large area that was never brought under a single authority but where cultural traits are shared in a patchwork of independent but allied city-states. Within this area there are both highlands that run parallel to the Pacific Coast and stretch into lower Guatemala, and lowlands that run from where the highlands end up through the tip of the Yucatan peninsula. Resources and terrain vary in predictable ways between the highlands and the lowlands, with granite, obsidian, and jade found in the mountainous region, while tropical animals and plants are found in the lowlands (Figure 1.4). Add to this the longest coastline of any ancient society, with approximately 1,500 kilometers of inlets, bays, and shallow beaches. Coastal resources such as shell and dried fish made their way deep inland throughout almost the entire Maya area (Figure 1.5). In the middle of the peninsula, the lowlands are cut through with rivers that often run over dangerous rapids or through narrow gorges that made the ancient cities perched on nearby escarpments easy to defend (Figure 1.6). Toward the northern part of the peninsula the rivers disappear but are replaced by natural sinkholes that provide access to underground freshwater reservoirs (Figure 1.7). The seasons in the entire Maya area, as in most tropical regions, are governed by the presence or absence of daily rains. In the summer it often rains every day and powerful storms or hurricanes blow through the region. In the winter it is drier and it rains less frequently.

Figure 1.3 Map of the Maya area, showing archaeological sites and modern cities mentioned in the text.

Figure 1.4 Agua Volcano, near Antigua, Guatemala, in the Maya highlands. Volcanic activity created the abundant obsidian resources used by ancient Maya people, but remains a risk to modern occupants of the Maya highlands.

Figure 1.5 Rainforest meets the Gulf of Mexico along the western coast of the Yucatan peninsula, Bay of Campeche.

Figure 1.6 Usumacinta River canyon, the border between Guatemala and Mexico.

Figure 1.7 Cenote Ik Kil, near Valladolid, Mexico.

Maize, or what North Americans call corn, was domesticated in the dry highlands of central Mexico thousands of years before Maya centers emerged. Scholars agree maize agriculture was already widely practiced by the time of the first Maya rulers. But agriculture in a tropical zone is fraught with risks – pests, droughts, and storms are more common than they are in temperate highland climates. Because ancient Maya society was completely dependent on maize agriculture, the arrival of daily rains at a predictable time of the year so seeds could sprout and crops ripen, was a huge preoccupation in Classic Maya culture. Maya royalty portrayed themselves in elite art dressed as the Maize Deity, a beautiful, youthful, gender-fluid figure that embodied the potential of a young maize plant. Rituals were performed in urban centers to call in the power of the mighty storm god Chac, when maize fields needed moisture. Temples were decorated with images of a native honeybee deity who helped pollinate the cornfields. Many of the major deities of Maya culture corresponded to aspects of the natural world that facilitated the growth of maize. But the lowlands in particular provide a wealth of other foods to feed the large urban populations of Maya cities. In addition to corn, which was planted by hand with beans and squash, Maya people domesticated the turkey and duck for food and hunted deer, peccary, iguana, turtle, and fish to round out their meals. Native fruit such as papaya, guava, and avocado added calories and flavor to the Maya diet, and nearly every household grew vegetables and herbs such as chili peppers, bush spinach, and cucumber. The wetter regions of the Maya area were conducive to growing cacao, or chocolate, and even modest households in places like the river valleys of Belize had cacao on hand.Footnote 2 The vanilla orchid is also native to the Maya area and likely was added to cacao drinks, along with chili powder and/or honey.

Chronology, Political Systems, and Modern Maya People

No matter how much you know about the ancient Maya you might be a little uncertain about whether or not they were living in cities when the Spanish arrived in the 16th-century New World. This uncertainty is understandable because the great encounters between kings of the Indigenous states in the New World and Spanish conquistadors are well known and shape how we think about the ancient history of the Americas. In the case of the ancient Maya, the story is a little more complex, and while Maya people certainly met Cortes and probably even Columbus when Europeans first traveled into Mexican waters, the elaborate Maya cities discussed in this book were not occupied when those meetings occurred. The chronology of ancient Maya culture is centered around their urban florescence – a word that was used by early Mayanists, or scholars of the Maya, to describe what they saw as the most interesting period of Maya history. Today we generally stick to slightly more neutral periodization terms, and organize Maya history into the Preclassic (also still called the Formative period by some scholars, 800 BCE–200 CE), the Classic (200–800 CE), the Terminal Classic (800–1100 CE), and the Postclassic (1100–1521 CE). The Preclassic period sets the stage for the urban explosion of the Classic, but also for the emergence of endemic or entrenched social stratification, the separation of farmers from rulers, and all the associated hierarchy that made the state-level social organization of the Classic period possible. During the Preclassic period Maya people transitioned from living in small egalitarian settlements to building the largest stucco-covered pyramids of their entire history. Shamans and healers evolve into royal kings and queens, and dynasties are founded that last for over 500 years, well into the Classic period. The writing system is codified, and images of divine rulers become standardized across the Maya area. It is a time of tremendous innovation and expansion.

These accomplishments provide the foundation of the Classic period, when Maya culture becomes the familiar ancient state often depicted in popular media. Most Maya art in museums around the word originated at the hands of artists working during the Classic period, when there were thousands of Maya cities each filled with thousands of people. Semi-divine dynastic rule was well established and nearly all ruling families were allied with one of a few large and powerful sovereign lines. Rural farmers had the responsibility of providing food for urban elites, and markets emerged for the exchange of commodities as well as exotic trade items. Alliances based on tenuous claims to kinship kept the lower social ranks indebted to the elites, who were understood to have divine or holy blood running through their veins. Large rituals in urban centers kept the majority of the population invested in their system of governance, although those who did not have faith were free to leave the cities and settle somewhere quieter. Competition for territory to support such an administrative burden was fierce, and boundary warfare became a constant feature of life. After six centuries the infrastructure that made the Classic period possible started to fray – the delicate tropical environment was overtaxed, the cities were full of too many people living too closely together, and unending wars had taken a toll on the population. We call this period the Terminal Classic. This ominous term attempts to capture some of the social changes underway in the 300-year period when the Maya state as it was known in the Classic period began to fail in a systematic way. Our first clue to the changes that took place in the Terminal Classic period was the evidence that many cities in the southern lowlands were abandoned at this time – or at least there was no new construction or inscriptions, and existing infrastructure was no longer maintained. Some scholars call this the Maya Collapse, although since we know Maya people lived on for many centuries, and survive today, it was really just a collapse of their Classic period political structure, not of the culture as a whole. “Postclassic” might sound like everything that happened after the party was over, but in fact this was another hugely dynamic period when almost everything changed and Maya people reinvented their society yet again. The Postclassic Maya era is contemporary with the rise of the Aztec Empire, which had a profound impact from the US Southwest all the way down into lower Central America. But the changes that define the Postclassic Maya period were not due to Aztec influence but rather were Maya responses to challenges and opportunities in their own area. Urban cities had largely failed and the population moved back to smaller, more sustainable settlements. The few cities that flourished did so due to impressive trade connections that brought goods and ideas together from throughout Mesoamerica. Art changed to reflect ideas and themes common throughout the region from which exotic trade goods flowed. So while the Maya never disappeared, as popular media often suggest, they did abandon an urban way of life and probably lost faith in their semi-divine royalty, opting instead for an even more decentralized form of political autonomy and individual self-reliance. This resilience was needed again at the end of the Postclassic period when the Spanish arrived in the early 16th century seeking converts and gold. Despite a brutal 500 years of colonial occupation, Maya people survived as many other New World Indigenous people did, by removing themselves from contact with the strangers and living as deeply within the jungle as possible, far from Spanish settlements. They mounted resistance movements that drew large numbers of Indigenous people together, and they made alliances with foreign powers. Today there are 7 million Maya-speaking people in Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras, with a diaspora that spreads throughout the United States and Canada. They are lawyers and politicians, professors and Nobel laureates, as well as subsistence farmers, weavers, and fisherfolk. Modern class differences influence how much modern Maya-speaking people know about their ancient ancestors, but Indigenous oral history and centuries of scientific research have demonstrated a clear line of cultural connection between the people who built the ancient cities in the jungle described in this book, and the modern people who farm, work, and govern the countries of the Maya region today. More and more Maya authors who write in one of the thirty modern Mayan languages, whether they are archaeologists, poets, or priests, are making their work available for Spanish or English readers curious about the ancient roots of this rich Indigenous culture.Footnote 3

Cosmology

Almost anyone who has visited Tulum, Antigua, or the other popular tourist destinations within the Maya world knows there was a large pantheon of Classic Maya deities. It can be confusing to try and learn their names and attributes, especially when these names vary in spelling and importance from region to region. Earlier scholars tried to organize the ancient Maya pantheon so that it corresponded to Western mythological systems like the ancient Greeks and Romans, but this was an artificial imposition on a very non-Western New World religious tradition. Today we understand that the best sources for learning how ancient Maya people thought about the universe is the evidence they left us in texts, ritual locations, and religious or mythological art. Ancient Maya art has helped us understand the belief system of Classic Maya people, and we are fortunate that Maya elites often commissioned artwork that depicted important mythological scenes. When we combine these sources with a 16th-century document that recorded, in K’iche’ Maya language, a much earlier origin myth, we actually know quite a lot about the very complex religious ideology of ancient Maya culture.Footnote 4

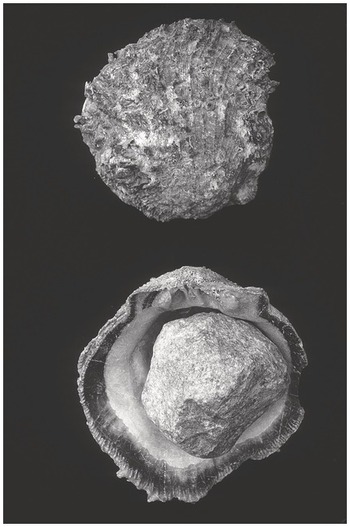

It is important to remember that like most non-Western cultures of the past and today, religion was not something easily separated from daily life in ancient Maya times. Small rituals permeated the chores and leisure activities of most people, and while there were certain full-time religious specialists at elite social levels, most people shared what we might today call religious or spiritual activities with their families and neighbors. The ancient Maya lived in an animistic world, meaning that all entities, living (in the Western sense) and not, held soul force. A mountain held tremendous soul force, as much as or more than a divine king – but so did a tiny jade bead, wild monkey, or beehive. Certain substances had a particularly valued form of soul force, for example, jade, which the ancient Maya prized above gold or silver, and cacao or chocolate beans. These were substances that inherently embodied the divine, like the royalty who governed Maya cities. Much of ancient Maya ritual was concerned with the movement of soul force found in certain substances like royal blood, copal incense, or sacred animals, from humans to a deity or venerated ancestor. Offerings of these precious substances were made by the devout on calendrically important days like the beginning of a new year or the anniversary of a king’s death, as well as when a special occasion demanded it such as in preparation for war or at the accession of a new queen (Figure 1.8).

Figure 1.8 Cache offering of a complete spiny oyster shell with greenstone, both substances that contained exceptional life force to the ancient Maya. Structure A8, Caracol, Belize.

Within this animate world, ancestors held tremendous influence. All ancient Maya people practiced some form of ancestral worship or veneration. Maya royalty would often commission long hieroglyphic texts that recounted their descent from a distinguished lineage founder or some other illustrious ancestor. Nonelite craftspeople and farmers maintained ancestral shrines near their homes where the cremated remains of ancestors could be interred and visited frequently, or they buried their beloved dead under the floor of their home in a family crypt that was used over and over again. These examples demonstrate that existence and agency did not end at physical death within the ancient Maya belief system, and the spirits of ancestors could be petitioned for assistance with earthly matters when necessary. Deities were also called upon and Maya royals often performed ceremonies where they attempted to embody the nature and appearance of a deity in order to bring themselves into contact with a particular soul force. Major Classic Maya deities will be discussed throughout the book as we touch on the areas of life they governed.

All Indigenous Mesoamerican peoples, including the ancient Aztecs, Maya, Zapotecs, and others, shared a broadly similar origin story about how the world came to be, how humans came to inhabit the world, and the relationship between humans and the rest of the natural world. In each specific culture the names of major heroes and deities changed, and there were regional differences in how the story was told, but the overall perspective was one in which time is cyclical and creation arose from the unpredictable force of transformation. Creation did not happen once; it happened multiple times, and was not perfect. Deities sometimes acted in unison but more often they acted in opposition. Their actions appear in the mythological narratives as cautionary tales about the power of creative inspiration, conflict, and transformation. As in many mythological systems, Maya creation deities appear as a primordial creator couple who take female and male form, and who work in concert each with their own skills, to create living creatures. Gender was a primary way in which Maya people ordered the universe, explained difference, and structured production of goods, families, and rituals. Gender appears often in Maya mythology as a clue to the importance of an activity: creation occurs when both male and female are balanced and in cooperation, young corn plants are bigendered, and the Maya maize deity is likewise gender-fluid, incorporating a youthful beauty that is neither fully male nor female. Old male gods of the underworld trap young goddesses in Maya myths that reflect cultural values about the vitality and fertility of the earth during the rainy season. Gender was not a limiting factor in expressions of the divine, as it can be in modern Western belief systems, but rather an essential component of the natural and supernatural world that conveyed important information to humans about how the universe was kept in balance.

One way in which the Mesoamerican cyclical understanding of time appears in Maya belief is in the repeated patterns of creation and destruction of the world. In each iteration prior to the world we live in now, there were earlier races of humans, often of inferior quality. Animals were created first, then mud people, then wooden people, and each was destroyed due to their failure to correctly recognize and praise the gods. But each failure provided the impetus for a new creation of better and more successful creatures. This is a fundamental aspect of Mesoamerican belief – creation of the world and its creatures, just like the creation of a ceramic vessel or hieroglyphic text, was the result of constant experimentation, failure, and accumulated expertise. We see this process at work in the myths of the Hero Twins, supernatural brothers who, through their repeated adventures hunting and journeying to the underworld, defeat the demons that would prevent the sun and moon from rising and thus keep the universe moving in an orderly fashion.

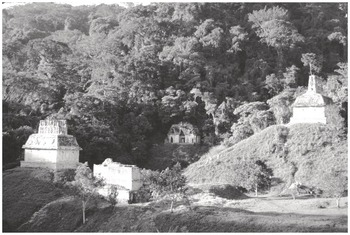

Sculptures from the important Maya site of Palenque contain long hieroglyphic texts and images describing the origins of the world and many of its major components from a Maya perspective such as the sun, warfare, maize, and the deities that provided the dynasty of Palenque with supernatural sanction (Figure 1.9). A passage at the Temple of the Cross details the importance of solar rebirth accompanied by imagery of the sacred World Tree growing from a plate marked with the sign for sun.Footnote 5 A nearby shrine known as the Temple of the Sun has imagery and text concerning sacred warfare, which we know was much more than warfare in terms of battles and weaponry (which were also important to Maya rulers, as we will see in Chapter 4). Warfare in this type of cosmological context was a metaphor for the cyclical processes of experimentation, failure, and eventual success described in the paragraph above. In the imagery of this shrine the Jaguar War God, who travels between the stars and the watery underworld, does battle in order to perpetuate creation. The final textual passage, found at the Temple of the Foliated Cross, is dedicated to the power of agriculture and the importance of water. Maize is shown growing from a mask that represents the cosmic sea and the text describes the birth of K’awiil, the god of lightning and dynastic power. From this one site, which admittedly has a very rich record concerning the origin of the world, we learn about the importance of natural phenomena like lightning and stars, how ancient Maya people took lessons from the observation of these natural phenomena, and the spiritual importance they placed on certain aspects of their lives such as agriculture and warfare.

Figure 1.9 The Cross Group at Palenque, Mexico. The Temple of the Cross, the Temple of the Sun, and the Temple of the Foliated Cross all record cosmological information about the origin of the world.

Maya cities are often described as haphazard in design or lacking a central plan, and it is true that they were never aligned to a single grid or arranged in the form of a sacred template like other cities of the ancient world. But this does not mean they lack an ideological basis or sense of order. Many household groups are arranged with a family shrine on the eastern side of the patio area. Settlements are often in sight of a significant natural landmark such as a sacred cave, mountain, or water source. The north-south axis is important in the arrangement of many Maya urban centers, with funerary pyramids more commonly in the northern neighborhood. Many Maya cities had architecture that was designed around astronomical phenomena such as the solstices and equinoxes, so the elites who moved through those buildings would have access to the particular soul force of an orderly universe. Clear ideas about how space should be used pervade all aspects of ancient Maya settlements.

How This Book Is Organized

This book presents my best estimation of what life was like in and around a Classic Maya city, using up-to-date information from a wide variety of sources. It is not meant to be a reconstructed history of a single city, but I drew extensively on the research to date at the Classic center of Coba, located in modern Quintana Roo, Mexico, to provide a data-centered basis for this narrative. Coba experienced a sixty-year period in the 7th century under three to four rulers including a very powerful royal queen who epitomized the ideal divine ruler of Classic Maya culture. Queen K’awiil Ajaw governed for many decades and grew the territory of her polity through wars of expansion, perhaps including the construction of a 100-kilometer-long road. She commemorated her military successes on huge carved stone monuments that display her captives and demanded that her portraits include full military regalia. Her court patronized the arts and sciences, and during this reign Maya scribes created highly advanced calendrical and mathematical inscriptions as well as the longest known Maya text on a stela. Her city-state had 50,000–70,000 citizens during this time and was one of the largest Classic Maya cities of the 7th century. It has the greatest number of carved stelae of any city in the northern lowlands, some of the tallest pyramids, and an extensive network of roads and causeways. In short, it provides ample inspiration as well as archeological and artistic data for an exploration of the daily lives of all social levels in the ancient period.

I want to introduce you to not only Queen K’awiil Ajaw but also other people that might have lived in the ancient city and its environs, including nearby farming and coastal settlements. I chose to give them Maya names, and their portraits in this book are drawn from the very best information we have about what life was like for women, men, non–gender binary people, children, elders, royals, farmers, artists, and so many more. Some of my colleagues may find these passages too fictionalized, and I am sensitive to the criticism that it is very hard to recover scientific information about specific individuals in the past. But it is far from impossible. I believe it is respectful and important to tell the individual stories and experiences of the ancient people who created the archaeological record we study today. They were grandmothers, explorers, and teachers in their time – not just numbers in an archaeological report. I hope these passages help erase the arbitrary line modern Western minds have drawn between the past and present.

We begin by considering the daily lives of the people who made the life of this queen possible. The majority of ancient Maya people lived on the outskirts of the exciting and bustling cities, close to the agricultural fields and forests that they tended. The crops grown outside the city and in their domestic gardens fed their families and were paid in tribute to the palace to feed royal families as well. In Chapter 2 we discover how domestic life was filled with crafting, gardening, and leisure. We will explore how ancient Maya families prepared daily meals, the animals and plants they kept in nearby gardens, the crafts they made, and how they spent leisure time in the evenings in the absence of modern illumination. Chapter 3 moves out of the domestic world and into the fields and forests nearby. What activities filled the days of an ancient Maya farmer? What rituals accompanied working a field and tending crops? The cornfield, or milpa, of Maya farmers was ideologically very important in Maya culture, and in many ways it was a microcosm of the settlement as a whole. Equally important was the boundary between cornfield and forest, and we will look at forest hunting practices as well as beekeeping along field/forest boundaries. Caves were also a ubiquitous part of the landscape and certain caves were reserved for ritual activities, which we look at in detail.

We move into the city in Chapter 4 by walking along the many paths and roadways that connected rural or suburban settlements to the urban center. The environment changes as one moves away from the agricultural sector and into the city – but so does the architecture and the activities performed on a daily basis. In this chapter we look at many of the craft specialties that took place inside the urban zone, including the marketplace that drew people in from the surrounding region. The ball game took place in the cities and we explore what we know about how it was played and the consequences at stake. Classic Maya culture is often seen as an urban culture but it was the interplay between rural and urban that kept the state functioning. Chapter 5 delves into daily life in the palace: the diplomatic visits and accompanying feasts that occupied royals, the dedicated work of the scribes who kept track of calendrical movements and recorded the activities of the royal family. Palaces were staffed with many specialists who helped keep the kingdom running, and yet members of the royal family had certain obligations to protect the spiritual fortune of their dynasties due to their special birth. Unequal access and institutionalized privilege was fundamental to ancient Maya society and it impacted the daily experiences of the elites as much as it did the rest of the population. Finally in Chapter 6 we explore what it was like to travel to a small Maya city at the sea, a port engaged in long-distance trade to provide inland polities with all the exotic goods they craved. From isotopic analyses we know that coastal settlements were filled with people of all social levels, often refugees from distant inland regions that left such places perhaps because they found them too predictable or maybe because they craved the adventurous life of a trader. The sea held a special place in Maya cosmology, as the origin of Maya people and the home of departed spirits. Traders enjoyed special privileges due to their connection to the sea, and religious pilgrimage sites were located on islands. As strongly as Maya people valued corn agriculture as a basis for their economy, they also depended on maritime trade for a wide variety of goods and services provided by traders who moved along the endless coastline in huge wooden canoes.

There is no single story of daily life in Classic Maya society, just as we could not tell a single story that captures the diversity of experiences in modern London or Miami. But by looking at evidence from the smallest rural settlement to the most elaborate palace, and the activities that were conducted every day in homes, fields, along the coast, and in the marketplace, I hope to capture some of the rich variety of lives that archaeologists and other scholars of the past are privileged to encounter.