Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Love and defection

- 2 The enemy within

- 3 Projecting a prophet for profit

- 4 Of gods and moguls

- 5 Negotiable dissent

- 6 Turning a negative into a positive

- 7 A cowboy in combats

- 8 Secrets and lies

- 9 The empire strikes back

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Film Index

- General Index

7 - A cowboy in combats

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 August 2013

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Love and defection

- 2 The enemy within

- 3 Projecting a prophet for profit

- 4 Of gods and moguls

- 5 Negotiable dissent

- 6 Turning a negative into a positive

- 7 A cowboy in combats

- 8 Secrets and lies

- 9 The empire strikes back

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Film Index

- General Index

Summary

Perhaps you remember the scene from ‘The Alamo’, when one of Davy Crockett's Tennesseans said: ‘What are we doing here in Texas fighting — it ain't our ox that's getting gored.’ Crockett replied: ‘Talkin’ about whose ox gets gored, figure this: a fella gets in the habit of gorin ‘oxes, it whets his appetite. May gore yours next.’ Unquote. And we don't want people like Kosygin, Mao Tse-Tung, or the like, ‘gorin’ our oxes.

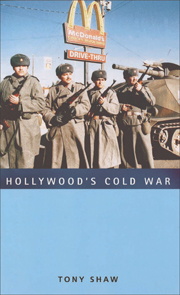

John Wayne to President Lyndon B. Johnson, 28 December 1965So far, this study has centred on those engaged in Cold War propaganda behind the screen — Hollywood producers, directors and scriptwriters, and government bodies like the USIA and CIA. But what of the part played in the battle for mass opinion by those who appeared in front of the camera? Ever since the creation of Hollywood's ‘star system’ in the 1920s, America's cinema-goers had developed a close affinity with Hollywood's leading actors and actresses. By 1945, for millions of Americans, film stars were little less than life coaches: in everything from fashion to family life, from language to politics. In the 1960s, despite the emergence of television celebrities, the deaths of ‘Hollywood greats’ like Spencer Tracy, Vivien Leigh and Montgomery Clift were the occasion for national mourning. Even in the Cold War's twilight years of the 1980s, the social and cultural influence of Hollywood's fewer but more economically powerful stars remained immense. Mega-salaried actors like Tom Cruise and Harrison Ford were global icons, American brand names as identifiable as Coca-Cola and McDonald's.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Hollywood's Cold War , pp. 199 - 233Publisher: Edinburgh University PressPrint publication year: 2007