1.1 The Licensing Industry

Students of intellectual property (IP) law are often steeped in the theory and practice of IP litigation. Record labels sue parodists and illegal downloaders, patent owners sue infringers, luxury brands sue counterfeiters, employers sue employees who leak their valuable secrets. All of these cases and the doctrines that they create could lead to a view of the world of IP as a battlefield. Like armaments, firms acquire IP rights solely to attack others, to bludgeon competitors or extract rent from consumers.

But this view is wrong. It arises from the unfortunate fact that legal education emphasizes reported judicial decisions over all else, and judicial decisions arise from litigation. The reality, however, is that the vast majority of economic activity involving IP arises from transactions – business arrangements among firms and with consumers and, sometimes, the government.

According to one industry group, global revenues for product licensing – the licensing of brands, images and logos for products of various kinds – were nearly $300 billion in 2019.Footnote 1 In 2019, recorded music sales, including digital streaming, were approximately $20 billion,Footnote 2 sales of enterprise software were $439 billion,Footnote 3 and global sales of smartphones exceeded $400 billion. All told, trillions of dollars every year change hands on the basis of IP licenses and transactions – far more than the total sum of all the IP litigation that has ever been brought.

Whichever of these figures most resonates with you, it is undeniable that IP licensing is a major economic activity with far-reaching implications both in the United States and worldwide. Virtually every product, every financial transaction and every communication on Earth depends, in some way, on an IP license.

This chapter lays the groundwork for the detailed study of IP licensing that follows in this book. It describes the business and economic motivations behind IP transactions, and seeks to give the reader an appreciation for the scope and range of IP licensing in the marketplace.

1.2 Why License?

The government grants the owner of an IP right the exclusive authority to exploit that right in its jurisdiction. At first blush, this seems like a golden opportunity for the IP owner to go into business. It can make, use, sell, display and perform the IP-protected thing with no competition from others for the entire duration of the relevant right. Build the better mousetrap, show the new masterpiece, storm the market with the new brand.

A moment’s thought, however, dispels these aspirations to grandeur. In reality, many owners of IP cannot, or are not willing to, exploit their IP to the fullest degree, if at all.Footnote 4 The author of the next Great American Novel would be foolish to self-publish her work using nothing but a laser printer or a personal website. She needs a publisher that can exploit the full range of print and electronic distribution channels that exist today. The university researcher who develops an improved method of satellite navigation can’t afford the hundreds of millions of dollars necessary to launch a satellite into orbit – her invention is best utilized by a company or government that is already in the satellite business. The producer of an independent animated film can’t be expected to open a factory to produce the myriad lunchboxes, backpacks, T-shirts and action figures demanded by the fans of the film. Those tasks are best left to others already in the manufacturing trade. The list goes on.

The fact is that IP owners are often not in the best position to exploit their own IP. They need help. And the way to get that help is through licensing. Through a license, an IP owner legally grants somebody else – a “licensee” – the right to exploit some or all aspects of a particular IP right. In return, the IP owner – the “licensor” – usually receives some form of compensation, often money, but sometimes services, equity in a company, or a license to IP held by the licensee. All of these arrangements have as their goal a more efficient allocation of rights among the owner and others who may be in a better position to exploit those rights. The result of that allocation is the most efficient use of the IP rights, maximizing the profit that can collectively be achieved by the licensor and its licensees. As such, we can say that the goal of nearly all IP licensing transactions is to optimize allocative efficiency among IP owner and users. When this is accomplished properly, the greatest overall value will result, thus maximizing the social value of a given IP right.

“the goal of nearly all IP licensing transactions is to optimize allocative efficiency among the IP owner and users.”

With the principle of allocative efficiency in mind, consider the following economic rationales that motivate IP licensing from the perspectives of the IP owner (the licensor) and the potential user of that IP (the licensee).Footnote 5

1.2.1 Market Expansion (Divide and Conquer)

The owner of an IP right – whether a patent, a copyright, a trademark or something else – may not have the internal capacity to exploit that right to its fullest extent, or at all. By licensing that IP right to someone with different capabilities and resources, segments of the market that are otherwise unaddressed may be addressed. For example, a small biotech company discovers a new process for detecting DNA variants. The process will be valuable to the company’s own research on diabetes therapies, but could be used in many other applications as well. When different licensees use the process in their own research, its use is expanded far beyond that of the original IP owner. Likewise, the creator of a popular comic book character may not manufacture consumer goods. But if it licenses the copyright in the character to consumer product companies, the character will appear on lunchboxes, backpacks and self-adhesive stickers that otherwise would not exist. Nor does a famous auto maker like Ferrari or Porsche produce T-shirts, key chains or sunglasses, but by licensing its marks to manufacturers of those products, it can satisfy consumer demand that would otherwise go unfulfilled. Some IP owners, such as universities and government laboratories, are unable to go into business at all, making licensing one of the only routes to commercialization of their IP.Footnote 6 Each of these examples illustrates the creation of new product and service markets for IP rights that might not exist without the IP owner’s ability to license its rights to others.Footnote 7

Figure 1.1 Auto makers like Ferrari do not manufacture the merchandise that bears their famous logos. This merchandise exists thanks to licensing.

1.2.2 Geographic Expansion

Like market expansion, IP licensing enables IP owners to expand the territorial reach of their IP rights.Footnote 8 Many products and services have international appeal, but local markets are often difficult to enter without assistance. Depending on the product and the market, significant regulatory approvals and clearances may be required, advertising and packaging materials must be localized, and adequate distribution channels must be identified and secured. Large multinationals sometimes do all of this by themselves, but most IP owners, even those of considerable size, cannot. Thus, in order to distribute products and services worldwide, local manufacturing, distribution, sales, support and agency partners are often needed. And to the extent that these local partners will be manufacturing, reproducing, modifying or displaying anything covered by IP rights, licenses will be required.

“Licensing for market expansion raises the issue of cannibalization. The licensor company will analyze at what point its licensees’ product sales may eat into (cannibalize) its own profits. Apple Computer faced this difficult challenge in the 1990s when it considered licensing its proprietary operating system to PC system manufacturers such as Dell, Vobis, Olivetti, and Acer. If Apple licensed to these companies for cloning, they would reduce the cost of manufacture, eliminate extras like design features, and drag the Apple technology and pricing – and possibly its brand – into commodity status. No one at Apple was able to assess systematically the cannibalization risk, or suggest ways to limit it, other than to exclude Apple’s most profitable geographic markets from the licenses. But those markets were precisely the markets that attracted the potential licensees. At the time they were not interested in making Apple clones only for the “rest of world” or “ROW” market (not Asia, Europe, or the United States). The potential licensees also wanted freedom to innovate based on Apple’s operating system, a competition that was potentially frightening to Apple. Apple ultimately decided not to pursue licensing its operating system.”

Cynthia Cannady, Technology Licensing and Development Agreements 51–52 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2013).

1.2.3 Capacity Expansion

In many cases, an IP owner may not possess the internal resources needed to exploit its rights fully, and can only do so with the financial or other assistance of others. A small biotech company does not have hundreds of millions of dollars required to conduct the clinical trials necessary to obtain regulatory approval for a new drug, nor do most screenwriters have the means to produce a television series based on a new script. In other words, an IP right may have value, but it is incomplete or not ready for market without further inputs – money, expertise, resources or additional innovation. In order to put these IP rights to productive use, assistance from others is often required. To do so, the biotech company can license its IP to a large pharmaceutical firm, and the screenwriter can license her script to a film studio or production company. In both cases, a product will be produced where none might exist otherwise, and the licensee and licensor will share the profits of the result.

1.2.4 Modularization

Even for large firms that theoretically have the capacity to take all the steps necessary to commercialize their IP, it may not be efficient for them to do so. First, there is substantial evidence that firms can increase efficiency and save costs by allocating specific tasks along the production chain to specialized (and lowest cost) suppliers, rather than performing these tasks internally.Footnote 10 This approach is sometimes referred to as “modularization” – the division of a multi-step process into discrete modules that can be performed by independent actors. For example, suppose that FryCo has developed an innovative, environmentally friendly coating for nonstick cookware. FryCo could, conceivably, purchase a fleet of delivery trucks to ensure that every consumer and retailer in the country had access to its wares. But unless FryCo’s sales volume is huge, it would be far more efficient to allocate delivery to a specialized service such as FedEx or UPS, allowing FryCo to focus on its core competencies. Likewise, if FryCo’s principal contribution is its secret nonstick coating, then it could focus its manufacturing efforts on production of that coating, while allocating the production of iron skillets to an established manufacturer of such products and granting it a license to apply FryCo’s proprietary coating to their surfaces. As Professor Jonathan Barnett observes, “licensing enables firms to select the sequence of ‘make/buy’ transactions that deliver innovations (or products and services embodying innovations) at the lowest possible cost.”Footnote 11

A related benefit of supply chain modularization is risk mitigation. Put simply, if FryCo manufactured its own iron skillets and its skillet factory burned down, it would suffer a significant business interruption. However, if FryCo sourced skillets to its specifications from, say, three different vendors in different locations, then the loss of any one of them would not be catastrophic. Modularization enables the producer to reduce its reliance on any single source of necessary components, thereby reducing risk in the production process.Footnote 12

Finally, modularization can enable firms to invest in multiple projects concurrently, rather than focusing all of their resources on one project at a time. As a result, a firm can spread its risk among a portfolio of projects, some of which may succeed and some of which may fail.Footnote 13

Figure 1.2 Jonathan Barnett illustrates how licensing enables motion picture firms to divide distribution rights among multiple entities, each with a specific role in the supply chain.Footnote 14

1.2.5 Monetization: Direct

In some cases an entity acquires IP rights primarily to earn revenue from licensing them. This is the case with research universities, which spend large sums on research, but which never intend to bring products or services to the commercial market. Their primary goal in obtaining IP rights – usually patents – is to license them to the private sector so that others can exploit them in exchange for payments. This business model is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 14.

Commercial entities can also find themselves in possession of IP rights that they do not have the capacity or desire to exploit themselves, but which they can profitably license to others. Sometimes, this occurs when business priorities shift, or when product lines that were covered by patents are no longer successful in the marketplace, leaving behind few product sales, but a rich portfolio of patent rights to license. Prominent product manufacturers like Palm, Blackberry, Nokia, Motorola and Ericsson saw the virtual evaporation of their product markets (mostly phones and other handheld communications devices), but were left with sizeable portfolios of patents representing substantial opportunities for licensing income.

Licensing for income generation is also practiced by companies that remain active in product markets, but which find themselves with portfolios of valuable patents that can be licensed. IBM, for example, earned more than $723 million in annual IP licensing revenue in 2018, and chip maker Qualcomm earns between $1 billion and $1.5 billion from its licensing business per quarter. This type of licensing revenue need not be related to products sold by the IP owner. For example, from about 2011 to 2015, Microsoft aggressively asserted and licensed patents covering Google’s Android operating system against smartphone makers such as Samsung, LG, HTC and Foxconn, earning Microsoft billions of dollars in revenue in a market segment in which it was a marginal player, at best.Footnote 15

Many IP licenses involve the payment of ongoing royalties to the licensor. In some cases these royalties can be quite high. But sometimes a licensor needs cash quickly, and cannot afford, or does not want, to wait for years to collect the total value of its IP. Licensors may thus resort to well-known financial instruments used in industries such as equipment leasing and mortgage financing to “sell” future royalty streams for an immediate, up-front sum.

Who buys IP royalty streams? One publicly traded firm, Royalty Pharma (RPRX – NASDAQ), specializes in pharmaceutical royalties. According to one source, Royalty Pharma spent $3.3 billion to acquire a share of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s royalties from Vertex Pharmaceuticals’ cystic fibrosis treatments, and $1.24 billion for the University of California’s royalties from the prostate cancer drug Xtandi, among many others.Footnote 16 Likewise, the Canadian Pensions Plan Investment Board agreed to pay LifeArc $1.3 billion for its royalty interest in Merck’s Keytruda cancer immunotherapy drug.

In some cases, royalty streams can be auctioned to the public. A share of the famous “perpetual” Listerine royalty (see Section 12.2.3) earning $32,000 per year was sold to an anonymous bidder for $560,000 at an auction in 2020.Footnote 17

But perhaps the most creative IP royalty sale was the 1997 securitization and public offering of 7.9 percent coupon bonds backed by the income from twenty-five pre-1990 recordings by singer David Bowie. The so-called “Bowie Bonds,” all of which were purchased by The Prudential Insurance Co., earned Bowie $55 million in a single transaction, and by 2016 had reportedly served as the model for more than 100 similar transactions in the music industry.Footnote 18

More recently, with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the indefinite suspension of live musical performances, an increasing number of artists, including legendary performers like Neil Young and Bob Dylan, have sold off the rights in their song catalogs to make ends meet.Footnote 19

1.2.6 Monetization: Indirect

Sometimes, the owner of an IP right may lack the ability and the resources to commercialize that IP right. For example, an individual inventor may make a breakthrough discovery in a field dominated by large players with which he or she cannot effectively compete, a start-up company may fail to raise sufficient funding to stay afloat, a company with a rich IP portfolio may be liquidated in bankruptcy, a company may be acquired by another firm that offers a competing product and a large firm may decide to discontinue a business line to which it holds IP rights. In all of these cases, the IP owner holds an asset that it spent valuable resources to create, but which it can no longer utilize productively. As a result, the IP owner’s best (or only) option may be to license or sell the underutilized IP right to an entity that can make productive use of it. But finding such an entity may be difficult, and the small inventor, the failed start-up, the bankruptcy trustee and the disinterested acquirer may lack the ability to do so.

Enter the middlemen, known variously as patent licensing firms, nonpracticing entities (NPEs), patent assertion entities (PAEs) and patent “trolls.”Footnote 20 These entities acquire IP rights from any of the sources described above and then seek to license them to others purely for economic gain, without creating or selling products or developing IP of their own. Despite the heated rhetoric that pervades this discussion, there is nothing inherently illegal or immoral about seeking to monetize IP assets, just as there is nothing wrong with financial institutions transacting in portfolios of consumer loans, mortgages or credit card debt.

“Patent troll” is a pejorative moniker commonly assigned to [non-practicing entities] (NPEs) because they allegedly wait for an industry to develop, then appear to exact a toll on companies who commercialize the technology. According to the detractors’ narrative, trolls are recent fly-by-night shops that assert business-method and internet patents. Trolls assert low-quality patents in low-quality litigation. They obtain patents from failed companies in fire sales. Worse, because trolls do not make anything, their patents do not provide anything of value to society. In short, according to their critics, patent trolls represent a significant break from past practices and foreshadow the downfall of innovative society.

NPEs are not, however, without their defenders. According to their proponents, NPEs create patent markets, and those markets enhance investment in start-up companies by providing additional liquidity options. NPEs help businesses crushed by larger competitors – competitors who infringe valid patents with impunity. NPEs allow individual inventors to monetize their inventions. These functions, the proponents argue, justify the existence of NPEs.

We need not delve into the debate over NPEs, PAEs and patent trolls, which has been ongoing for years. It involves questions well beyond the scope of this book, including the appropriateness of certain litigation tactics and the underlying quality of many patents that are asserted in litigation. While some PAEs shoot first and negotiate later, others would seemingly prefer to license their IP assets without resorting to expensive and risky litigation. The common motivating factor for licensing among these entities is the generation of financial returns.

1.2.7 Rights Aggregation

In some cases an entity’s IP protects only a portion of an overall product, or constitutes an improvement on somebody else’s IP. In these cases an entity’s IP cannot practically be exploited without the cooperation of others. Sometimes, no one entity can act in a field without obtaining permissions from others – such fields are said to be characterized by “blocking” positions. For example, in Standard Oil Co. (Indiana) v. United States, 283 U.S. 163 (1931), four large oil companies each held patents necessary to perform the process of “cracking” crude oil to make gasoline. Each company’s patents were blocking – none could perform the process without the cooperation of the others.Footnote 21 Likewise, in Nadel v. Play-By-Play Toys & Novelties, Inc., 208 F.3d 368 (2d Cir. 1999),Footnote 22 an independent toy designer created a spinning plush toy based on Warner Bros. “Tazmanian Devil” character. He could not market his toy without the permission of Warner Bros., nor could Warner Bros. market the toy without his permission.

Figure 1.3 The debate over “patent trolls” has been raging for over a decade.

One important function of IP licensing is enabling entities to overcome these blocking positions, so that they may operate productively in the field. That is, without licensing an entity would have to acquire ownership of all blocking rights or create an entirely new product or service that does not infringe the IP of others. Both of these alternatives are often impossible, making licensing the best and only option for the productive use of one’s own IP. Licensing of this nature can occur through individual licensing negotiations, cross-licenses (in which each party grants parallel licenses to the other), or pursuant to IP pools in which the rights of multiple IP owners are licensed on an aggregated basis (discussed in Chapter 26). While these transactions are often quite different in nature, they share the common feature of eliminating barriers to the efficient utilization of IP within a market sector.

1.2.8 Platform Leadership

In some instances the developer of a technology or creative platform may wish to license rights to others to encourage the broad use of its platform. This approach was adopted early by the makers of video game consoles (Sony, Nintendo, Microsoft), which sought to encourage game developers to write games optimized for their platforms. Today, the Apple App Store and Google Play exemplify a similar approach.Footnote 23 Similar motivations are at work in the area of open source software (Section 19.2), technical interoperability standards (Chapter 20) and many patent “pledges” (Section 19.4).

In each case, the owner of a platform technology makes it available, often without charge, to encourage the independent development of products and services compatible with the platform. With a platform’s growth and adoption, the IP owner can sell ancillary products and services, effectively using the broadly licensed rights as “loss leaders” to promote other revenue-generating activities. For example, IBM’s open source licensing of its Linux-based operating system led to substantial revenue from the sale of Linux servers and professional services, and Google’s release of its Android operating system on an open source basis led to its widespread adoption and substantial ad revenue for Google.Footnote 24 Likewise, the developers of important interoperability standards such as Bluetooth and USB license patents covering these standards on a royalty-free basis, as the broad adoption of these standards enables them to sell more products and services (e.g., laptops, routers, chips, network services) that rely on those standards.

Notes and Questions

1. Cannibalization. What is cannibalization of a market? Why did cannibalization concerns deter Apple from licensing its operating system to other manufacturers, as Microsoft had done?

2. Unplugging bottlenecks. As noted in note 7, Professors Contreras and Sherkow claim that “even if the IP owner has the theoretical capability to address all of the different markets that can be addressed by an IP right, it is likely that licensing rights to others in some of those markets will result in the more rapid deployment of new products and services (i.e., retaining all rights in the original IP owner could create bottlenecks in the development of new products and services).” Why would an IP owner’s retention of rights create developmental bottlenecks? How can these bottlenecks be avoided?

3. The troll debate. What objections can be raised to the monetization of IP rights? Is there anything inherently wrong with using IP as a money-making investment? What types of litigation behavior might have made PAEs unpopular in many circles?

4. Platforms. How do the Apple App Store and Google Play exemplify a platform leadership strategy? What goals do you think Apple and Google have with respect to these platforms? What other online platforms have a similar strategy?

5. Giving it away. What would motivate the holder of a valuable IP right to give it away for free? Is this behavior irrational? How would you decide when a “give away” strategy is worth pursuing? Consider these issues when you read about open source software and patent pledges in Chapter 19.

Problem 1.1

Which IP licensing model would you recommend for each of the following companies? State any assumptions about the company’s business that support your recommendation.

a. FryCo, a small chemical company that has developed an environmentally friendly nonstick cooking surface.

b. Twenty-First Century Films, an independent documentary film producer.

c. DeLuxe, a luxury brand known for its high-end leather accessories such as handbags, wallets and belts.

d. Droplet Labs, a start-up company that has patented a process for testing a single drop of a patient’s blood for twenty different pathogens.

Problem 1.2

Your client Fizzy Cola is a producer of craft soft drinks based in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Fizzy tells you that it would like to expand internationally to South America, the European Union, China, Japan and South Korea. What licensing and internationalization strategy would you recommend for Fizzy?

Summary Contents

The owner of an intellectual property (IP) right, whether a patent, copyright, trademark, trade secret or other right, has the exclusive right to exploit that right. Ownership of an IP right is thus the most effective and potent means for utilizing that right. But what does it mean to “own” an IP right and how does a person – an individual or a firm – acquire ownership of it? This chapter explores transfers and assignments of IP ownership, first in general, and then with respect to special considerations pertinent to patents, copyrights and trademarks. Assignments and transfers of IP licenses, another important topic, are covered in Section 13.3, and attempts to prohibit an assignor of IP from later challenging the validity of transferred IP (through a contractual no-challenge clause or the common law doctrine of “assignor estoppel”) are covered in Chapter 22.

2.1 Assignments of Intellectual Property, Generally

Once it is in existence, an item of IP may be bought, sold, transferred and assigned much as any other form of property. Like real and personal property, IP can be conveyed through contract, bankruptcy sale, will or intestate succession, and can change hands through any number of corporate transactions such as mergers, asset sales, spinoffs and stock sales.

The following case illustrates how IP rights will be treated by the courts much as any other assets transferred among parties. In this case, the court must interpret a “bill of sale,” the document listing assets conveyed in a particular transaction. Just as with bushels of grain or tons of steel, particular IP rights can be listed in a bill of sale and the manner in which they are listed will determine what the buyer receives.

228 Fed. Appx. 854 (11th Cir. 2007) (cert. denied)

Per Curiam

Following the settlement of a dispute between Systems Unlimited, Inc. and Cisco Systems, Inc. over the ownership of certain intellectual property, Cisco agreed to covey the property to Systems. In the resulting bill of sale, Cisco:

granted, bargained, sold, transferred and delivered, and by these presents does grant, bargain, sell, transfer and deliver unto [Systems], its successor and assigns, the following:

Any and all of [Cisco]’s right, title and interest in any copyrights, patents, trademarks, trade secrets and other intellectual property of any kind associated with any software, code or data, including without limitation host controller software and billing software, whether embedded or in any other form (including without limitations, disks, CDs and magnetic tapes), and including any and all available copies thereof and any and all books and records related thereto by [Cisco]

Cisco never delivered [copies of] any of the software to Systems. Alleging that it had been damaged by the non-delivery, Systems sued Cisco for breaching the bill of sale contract and for violating the attendant obligations to deliver the software under the Uniform Commercial Code.

Systems contends that the district court erred in granting summary judgment in favor of Cisco because: (1) the plain language of the bill of sale required Cisco to deliver the software; (2) the bill of sale, when read in conjunction with other contemporaneous agreements, required delivery; and (3) the UCC, which governs the bill of sale, requires that all goods be delivered at a reasonable time. Systems is wrong on each point.

The bill of sale is interpreted in accord with its plain language absent some ambiguity. Here, the parties agree that the bill of sale is clear and unambiguous.

The bill of sale provides that Cisco will “grant, bargain, sell, transfer and deliver unto [Systems] … [a]ny and all of [Cisco]’s right, title and interest in any copyrights, patents, trademarks, trade secrets and other intellectual property of a kind associated with any software, code or data.” As the district court explained, this language unambiguously means that Cisco was required by the bill of sale to transfer to Systems all of its rights in intellectual property associated with certain software and data. There is no mention in the plain language of the contract itself of Cisco being obligated to transfer the actual software, and we will not imply any such obligation absent some good reason under law.

Systems says there are two good reasons to imply an obligation by Cisco to transfer the software. First, Systems argues that the bill of sale must be interpreted in conjunction with the settlement agreement between Systems and Cisco and other documents relating to the intellectual property. These other agreements, Systems claims, include an obligation by Cisco to deliver the software with any conveyance of intellectual property.

Assuming without deciding that the other agreements include language requiring Cisco to deliver the software, they are not relevant here because Systems has never alleged Cisco violated these other agreements. Systems’ complaint alleges only a violation of the bill of sale contract, and there is no obligation in that contract to deliver the software. The bill of sale does not reference or incorporate any other agreement.

To get around this point, Systems argues that “when instruments relate to the same matters, are between the same parties, and made part of substantially one transaction, they are to be taken together.” It is true that this is one of the canons for construing a contract under California law. But it is also true that this canon, as with most others, is inapplicable where the contract that is alleged to have been breached is unambiguous. Here, the language of the bill of sale is unambiguous. Thus, there is no need to apply any canons of construction.

Systems also argues that the UCC imposes a duty on Cisco to deliver the software. We will assume without deciding that Systems’ reading of the UCC is correct. Even so, the provisions of the UCC only apply to contracts that deal predominately with “transactions in goods.” The sale of intellectual property, which is what is involved here, is not a transaction in goods. Thus, the UCC does not apply. Accordingly, the plain language of the bill of sale governs and, as the district court held, it does not include a provision requiring Cisco to deliver any software.

AFFIRMED.

Notes and Questions

1. IP and the UCC. The court in Systems v. Cisco holds that IP licenses and other transactions are not governed by Article 2 of the UCC, which pertains to sales of goods. In Section 3.4 we will discuss whether and to what degree Article 2 applies to IP licenses. But this case relates not to a license, but to a “sale” of software. Why doesn’t UCC Article 2 apply? Should it?

2. Delivery of what? What does this language from the bill of sale refer to, if not delivery of software: “including any and all available copies thereof”? Does this language represent a drafting mistake by Systems’ attorney? Or an intentional omission by Cisco?

3. The need for software. Why is Systems so upset that Cisco has allegedly refused to deliver the software in question? How useful is an assignment of copyright and other IP to someone who is not in possession of the software code that is copyrighted? Has Cisco “pulled a fast one” on Systems and the court, or is there a valid business reason that could justify Cisco’s failure to deliver the software?

4. Statute of frauds. Assignments of copyrights, patents and trademarks must all be in writing (17 U.S.C. § 204(a), 35 U.S.C. § 261, 15 U.S.C. § 1060(3)). Why? This requirement does not apply to most licenses, which may be oral. Can you think of a good reason for this distinction?

5. State law and mutual mistake. Despite the federal statutory nature of patents, courts have long held that the question of who holds title to a patent is a matter of state contract law.Footnote 1 This issue arose in an interesting way in Schwendimann v. Arkwright Advanced Coating, Inc., 959 F.3d 1065 (Fed. Cir. 2020). In Schwendimann, the plaintiff’s former company purported to assign her a patent application in 2003. Due to a clerical error by the law firm handling the matter, the assignment document filed with the patent office listed the wrong patent name and number. In 2011, the plaintiff filed an action asserting the patent against an alleged infringer. The defendant, discovering the incorrect assignment document from 2003, moved to dismiss on the ground that the plaintiff did not hold any enforceable rights at the time she filed suit and thus lacked standing. The district court, interpreting applicable state law, held that the 2003 assignment was the result of a “mutual mistake of fact” that did not accurately reflect the intent of the parties. Accordingly, the erroneous document could be reformed and was sufficient to support standing to bring suit. The Federal Circuit affirmed. Judge Reyna dissented, reasoning that, irrespective of the district court’s later reformation of the erroneous assignment, the plaintiff’s failure to own the patent at the time her suit was filed necessarily barred her suit under Article III of the Constitution. Which of these positions do you find more persuasive? Notwithstanding the holding in favor of the plaintiff, is there a claim for legal malpractice against the law firm in question?

2.2 Assignment of Copyrights and the Work Made for Hire Doctrine

Under § 201(a) of the Copyright Act, copyright ownership “vests initially in the author or authors of the work.” A copyright owner may assign any of its exclusive rights, in full or in part, to a third party. The assignment generally must be in writing and signed by the owner of the copyright or his or her authorized agent (17 U.S.C. § 204(a)).

If a work of authorship is prepared by an employee within the scope of his or her employment, then the work is a “work made for hire” and the employer is considered the author and owner of the copyright (17 U.S.C. § 201(b)). In addition, if a work is not made by an employee but is “specially ordered or commissioned,” it will be considered a work made for hire if it falls into one of nine categories enumerated in § 101(2) of the Act: a contribution to a collective work, a part of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, a translation, a supplementary work, a compilation, an instructional text, a test, answer material for a test, or an atlas. Commissioned works that do not fall into one of these nine categories (for example, software) are not automatically considered to be works made for hire, and copyright must be assigned explicitly through a separate assignment or sale agreement.

328 F.3d 1136 (9th Cir. 2003)

HAWKINS, Circuit Judge.

In this dispute between plaintiff-appellant Richard Warren (”Warren”) and defendants-appellees Fox Family Worldwide (“Fox”), MTM Productions (“MTM”), Princess Cruise Lines (“Princess”), and the Christian Broadcasting Network (“CBN”), Warren claims that defendants infringed the copyrights in musical compositions he created for use in the television series “Remington Steele.” Concluding that Warren has no standing to sue for infringement because he is neither the legal nor beneficial owner of the copyrights in question, we affirm the district court’s Rule 12 dismissal of Warren’s complaint.

Warren and Triplet Music Enterprises, Inc. (“Triplet”) entered into the first of a series of detailed written contracts with MTM concerning the composition of music for “Remington Steele.” This agreement stated that Warren, as sole shareholder and employee of Triplet, would provide services by creating music in return for compensation from MTM. Under the agreement, MTM was to make a written accounting of all sales of broadcast rights to the series and was required to pay Warren a percentage of all sales of broadcast rights to the series made to third parties not affiliated with ASCAP or BMI. These agreements were renewed and re-executed with slight modifications in 1984, 1985 and 1986.

Warren brought suit in propria persona against Fox, MTM, CBN, and Princess, alleging copyright infringement, breach of contract, accounting, conversion, breach of fiduciary duty, breach of covenants of good faith and fair dealing, and fraud.

Warren claims he created approximately 1,914 musical works used in the series pursuant to the agreements with MTM; that MTM and Fox have materially breached their obligations under the contracts by failing to account for or pay the full amount of royalties due Warren from sales to parties not affiliated with ASCAP or BMI; and that MTM and Fox infringed Warren’s copyrights in the music by continuing to broadcast and license the series after materially breaching the contracts. As to the other defendants, Warren claims that CBN and Princess infringed his copyrights by broadcasting “Remington Steele” without his authorization. Warren seeks damages, an injunction, and an order declaring him the owner of the copyrights at issue.

Defendants argu[ed] that Warren’s infringement claims should be dismissed for lack of standing because he is neither the legal nor beneficial owner of the copyrights. The district court dismissed Warren’s copyright claims without leave to amend and dismissed his state law claims without prejudice to their refiling in state court, holding that Warren lacked standing because the works were made for hire, and because a creator of works for hire cannot be a beneficial owner of a copyright in the work. Warren appeals.

The first agreement [between the parties], signed on February 25, 1982, states that MTM contracted to employ Warren “to render services to [MTM] for the television pilot photoplay now entitled ‘Remington Steele.’” It also is clear that the parties agreed that MTM would “own all right, title and interest in and to [Warren’s] services and the results and proceeds thereof, and all other rights granted to [MTM] in [the Music Employment Agreement] to the same extent as if … [MTM were] the employer of [Warren].” The Music Employment Agreement provided:

As [Warren’s] employer for hire, [MTM] shall own in perpetuity, throughout the universe, solely and exclusively, all rights of every kind and character, in the musical material and all other results and proceeds of the services rendered by [Warren] hereunder and [MTM] shall be deemed the author thereof for all purposes.

Figure 2.1 Warren claimed that he created 1,914 musical works for the popular 1980s TV series Remington Steele.

The parties later executed contracts almost identical to these first agreements in June 1984, July 1985, and November 1986. As the district court noted, these subsequent contracts are even more explicit in defining the compositions as “works for hire.” Letters that Warren signed accompanying the later Music Employment Agreements provided: “It is understood and agreed that you are supplying [your] services to us as our employee for hire … [and] [w]e shall own all right, title and interest in and to [your] services and the results and proceeds thereof, as works made for hire.”

That the agreements did not use the talismanic words “specially ordered or commissioned” matters not, for there is no requirement, either in the Act or the caselaw, that work-for-hire contracts include any specific wording. In fact, in Playboy Enterprises v. Dumas, 53 F.3d 549 (2d Cir. 1995), the Second Circuit held that legends stamped on checks were writings sufficient to evidence a work-for-hire relationship where the legend read: “By endorsement, payee: acknowledges payment in full for services rendered on a work-made-for-hire basis in connection with the Work named on the face of this check, and confirms ownership by Playboy Enterprises, Inc. of all right, title and interest (except physical possession), including all rights of copyright, in and to the Work.” Id. at 560. The agreements at issue in the instant case are more explicit than the brief statement that was before the Second Circuit.

In this case, not only did the contracts internally designate the compositions as “works made for hire,” they provided that MTM “shall be deemed the author thereof for all purposes.” This is consistent with a work-for-hire relationship under the Act, which provides that “the employer or other person for whom the work was prepared is considered the author.” 17 U.S.C. § 201(b).

Warren argues that the use of royalties as a form of compensation demonstrates that this was not a work-for-hire arrangement. While we have not addressed this specific question, the Second Circuit held in Playboy that “where the creator of a work receives royalties as payment, that method of payment generally weighs against finding a work-for-hire relationship.” 53 F.3d at 555. However, Playboy clearly held that this factor was not conclusive. In addition to noting that the presence of royalties only “generally” weighs against a work-for-hire relationship, Playboy cites Picture Music, Inc. v. Bourne, Inc., 457 F.2d 1213, 1216 (2d Cir. 1972), for the proposition that “[t]he absence of a fixed salary … is never conclusive.” 53 F.3d at 555. Further, the payment of royalties was only one form of compensation given to Warren under the contracts. Warren was also given a fixed sum “payable upon completion.” That some royalties were agreed upon in addition to this sum is not sufficient to overcome the great weight of the contractual evidence indicating a work-for-hire relationship.

Warren also argues that because he created nearly 2,000 musical works for MTM, the works were not specially ordered or commissioned. However, the number of works at issue has no bearing on the existence of a work-for-hire relationship. As the district court noted, a weekly television show would naturally require “substantial quantities of verbal, visual and musical content.”

The agreements between Warren and MTM conclusively show that the musical compositions created by Warren were created as works for hire, and Warren is therefore not the legal owner of the copyrights therein.

AFFIRMED.

Notes and Questions

1. Employee v. Contractor. In Warren v. Fox the musical compositions created by Warren fell into one of the nine categories of “specially commissioned works” that qualify as works made for hire under § 101(2) of the Copyright Act (audiovisual works), even if they were not made by employees of the commissioning party. They will thus be classified as works made for hire so long as they can be shown to have been “specially commissioned” – the focus of the debate in Warren. A slightly different question arose in Community for Creative Non-Violence v. Reid, 490 U.S. 730 (1989). In that case Reid, a sculptor, was engaged by a nonprofit organization, CCNV, to create a memorial “to dramatize the plight of the homeless.” Sculpture is not one of the nine enumerated categories of commissioned works. Thus, even if Reid’s sculpture were “specially commissioned” (as it probably was), it would not be classified as a work made for hire under § 101 unless Reid were considered to be an employee of CCNV. CCNV argued that it exercised a certain degree of control over the subject matter of the sculpture, making it appropriate to classify Reid as its employee. The Court disagreed:

Reid is a sculptor, a skilled occupation. Reid supplied his own tools. He worked in his own studio in Baltimore, making daily supervision of his activities from Washington practicably impossible. Reid was retained for less than two months, a relatively short period of time. During and after this time, CCNV had no right to assign additional projects to Reid. Apart from the deadline for completing the sculpture, Reid had absolute freedom to decide when and how long to work. CCNV paid Reid $15,000, a sum dependent on completion of a specific job, a method by which independent contractors are often compensated. Reid had total discretion in hiring and paying assistants. Creating sculptures was hardly regular business for CCNV. Indeed, CCNV is not a business at all. Finally, CCNV did not pay payroll or Social Security taxes, provide any employee benefits, or contribute to unemployment insurance or workers’ compensation funds.

Does the structure of the works made for hire doctrine under § 101(2) of the Copyright Act make sense? Why should specially commissioned works be considered works for hire only if they fall into one of the nine enumerated categories? Why is a musical composition treated so differently than a sculpture?

2. Manner of compensation. The form of compensation received by the author is mentioned in both Warren v. Fox and CCNV v. Reid. Why is this detail significant to the question of works made for hire? Are the courts’ conclusions with respect to compensation consistent between these two cases?

3. Software contractors and assignment. For a variety of professional, financial and tax-planning reasons, software developers often work as independent contractors and are not hired as employees of the companies for which they create software. And, like the sculpture in CCNV v. Reid, software is not one of the nine enumerated categories of works under § 101(2) of the Copyright Act. Thus, even if it is specially commissioned, software will not be considered a work made for hire. As a result, companies that use independent contractors to develop software must be careful to put in place copyright assignment agreements with those contractors. And because contractors often sit and work beside company employees with very little to distinguish them, neglecting to take these contractual precautions is one of the most common IP missteps made by fledgling and mature software companies alike. If you were the general counsel of a new software company, how would you deal with this issue?

4. Recordation. Section 205 of the Copyright Act provides for recordation of copyright transfers with the Copyright Office. Recordation of transfers is not required, but provides priority if the owner attempts to transfer the same copyrighted work multiple times:

§ 205(d) Priority between Conflicting Transfers.—As between two conflicting transfers, the one executed first prevails if it is recorded, in the manner required to give constructive notice … Otherwise the later transfer prevails if recorded first in such manner, and if taken in good faith, for valuable consideration or on the basis of a binding promise to pay royalties, and without notice of the earlier transfer.

As students of real property will surely observe, this provision resembles a “race-notice” recording statute under state law. As such, the second transferee of a copyright may prevail over a prior, unrecorded transferee if the second transferee records first without notice of the earlier transfer. Note also that this provision is applicable only to copyrights that are registered with the Copyright Office.

5. Statutory termination of assignments. Sections 203 and 304 of the Copyright Act provide that any transfer of a copyright can be revoked by the transferor between 35 and 40 years after the original transfer was made.Footnote 2 This remarkable and powerful right is irrevocable and cannot be contractually waived or circumvented. It was intended to enable authors who were young and unrecognized when they first granted rights to more powerful publishers to profit from the later success of their works. For example, in 1938 Jerry Siegel and Joseph Shuster, the creators of the Superman character, sold their rights to the predecessor of DC Comics for $130. Siegel and Shuster both died penniless in the 1990s, while Superman earned billions for his corporate owners.

Though Sections 203 and 304 were originally directed to artists, writers and composers, these provisions apply across the board to all copyrighted works including software and technical standards documents. The possibility that an original developer of Microsoft Windows could suddenly pull the plug on millions of existing licenses is somewhat ameliorated because the reversion does not apply to works made for hire or derivative works. Nevertheless, one must ask why these reversionary rights apply to software and technical documents at all. If such works of authorship are excluded as works made for hire under Section 101(2), why shouldn’t they also be excluded from Sections 203/304?Footnote 3 Is there any justification for allowing developers of copyrighted “technology” products to terminate assignments made decades ago?

6. Divisibility of copyright. Prior to the Copyright Act of 1976, copyright ownership was not divisible. That is, the owner of a copyright, say in a book, could not assign the exclusive right to produce a film based on that book to a third party. The right to produce a film could be licensed to a third party, but an attempted assignment of the right would potentially be invalid or treated as a license.Footnote 4 But today, under 17 U.S.C. § 201(d)(2), “Any of the exclusive rights comprised in a copyright, including any subdivision of any of the rights specified by section 106, may be transferred … and owned separately.” What do you think was the rationale for this change in the law? Why would, say, a film studio prefer to “own” the right to produce a film based on a book rather than have a license to do so?

Figure 2.2 The creators of the Superman character died in near poverty while the Man of Steel went on to form a multi-billion-dollar franchise. Sections 203 and 304 of the US Copyright Act were enacted to enable authors and their heirs to terminate any copyright assignment or license between 35 and 40 years after originally made in order to permit them to share in the value of their creations.

2.3 Assignment Of Patent Rights

As with other IP rights, patents, patent applications and inventions may be assigned. Patent rights initially vest in inventors who are, by definition, individuals. Unlike copyright, there is no work made for hire doctrine under US patent law. However, if an employee is “hired to invent” – that is, to perform tasks intended to result in an invention – then the employee may have a legal duty to assign the resulting invention to his or her employer.Footnote 5

Unfortunately, the “hired to invent” doctrine is murky and inconsistently applied.Footnote 6 Thus, most employers today contractually obligate their employees to assign rights in inventions and patents to them when made within the scope of their employment and/or using the employer’s resources or facilities. This requirement exists in the private sector, at nonprofit universities and research institutions, as well as government agencies. The initial assignment from an inventor to his or her employer is often filed during prosecution of a patent on a form provided by the Patent and Trademark Office. If such an assignment is not filed, the inventor’s employer obtains no rights in an issued patent other than so-called “shop rights” that allow the employer to use the patented invention on a limited basis.Footnote 7

Beyond the initial assignment from the inventor(s), the owner of a patent may assign it to a third party as any other property right. The following case turns on whether an inventor assigned his rights to his employer at the time the invention was conceived, or when the patent was issued.

939 F.2d 1568 (Fed. Cir. 1991)

PLAGER, CIRCUIT JUDGE

Allied-Signal Inc. and UOP Inc. (Allied), defendants-appellants, appeal from the preliminary injunction issued by the district court. The trial court enjoined Allied from “making, using or selling, and actively inducing others to make use or sell TFCL membrane in the United States, and from otherwise infringing claim 7 of United States Patent No. 4,277,344 [’344].” Because of serious doubts on the record before us as to who has title to the invention and the ensuing patent, we vacate the grant of the injunction and remand for further proceedings.

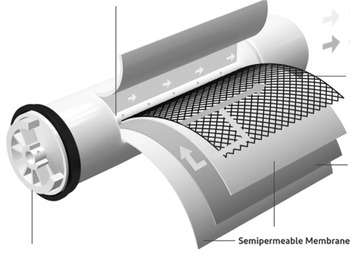

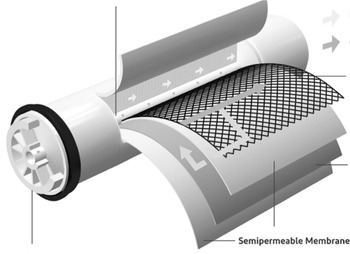

The application which ultimately issued as the ‘344 patent was filed by John E. Cadotte on February 22, 1979. The patent claims a reverse osmosis membrane and a method for using the membrane to reduce the concentration of solute molecules and ions in solution. Cadotte assigned his rights in the application and any subsequently issuing patent to plaintiff-appellee FilmTec. This assignment was duly recorded in the United States Patent and Trademark Office. Defendant-appellant Allied manufactured a reverse osmosis membrane and FilmTec sued Allied for infringing certain claims of the ’344 patent.

John Cadotte was one of the four founders of FilmTec. Prior to founding FilmTec, Cadotte and the other founders were employed in various responsible positions at the North Star Division of Midwest Research Institute (MRI), a not-for-profit research organization. MRI was principally engaged in contract research, much of it for the United States (Government), and much of it involving work in the field of reverse osmosis membranes.

The evidence indicates that the work at MRI in which Cadotte and the other founders were engaged was being carried out under contract (the contract) to the Government. The contract provided that MRI

agrees to grant and does hereby grant to the Government the full and entire domestic right, title and interest in [any invention, discovery, improvement or development (whether or not patentable) made in the course of or under this contract or any subcontract … thereunder].

It appears that sometime between the time FilmTec came into being in 1977 and the time Cadotte submitted his patent application in February of 1979, he made the invention that led to the ’344 patent. As we will explain, just when in that period the invention was made is critical.

Cadotte left MRI in January of 1978. Cadotte testified that he conceived his invention the month after he left MRI. Allied disputes this, and alleges that Cadotte conceived his invention and formed the reverse osmosis membrane of the ’344 patent earlier—in July of 1977 or at least by November of 1977 when he allegedly produced an improved membrane.

Allied alleges that the evidence establishes that the contract between MRI and the Government grants to the Government “all discoveries and inventions made within the scope of their [i.e., MRI’s employees] employment,” and that the invention claimed in the ’344 patent was made by Cadotte while employed by MRI. From this Allied reasons that rights in the invention must be with the Government and therefore Cadotte had no rights to assign to FilmTec. If FilmTec lacks title to the patent, FilmTec has no standing to bring an infringement action under the ’344 patent. FilmTec counters by arguing that the trial court was correct in concluding that the most the Government would have acquired was an equitable title to the ’344 patent, which title would have been made void under 35 U.S.C. § 261 by the subsequent assignment to FilmTec from Cadotte.

The parties agree that Cadotte was employed by MRI and that the contract between MRI and the Government contains a grant of rights to inventions made pursuant to the contract. However, the record does not reflect whether the employment agreement between Cadotte and MRI either granted or required Cadotte to grant to MRI the rights to inventions made by Cadotte. Allied argues that Cadotte’s inventions were assigned nevertheless to MRI. Allied points to the provision in the contract between MRI and the Government in which MRI warrants that it will obligate inventors to assign their rights to MRI.

While this is not conclusive evidence of a grant of or a requirement to grant rights by Cadotte, it raises a serious question about the nature of the title, if any, in FilmTec. FilmTec apparently did not address this issue at the trial, and there is no indication in the opinion of the district court that this gap in the chain of ownership rights was considered by the court.

Between the time of an invention and the issuance of a patent, rights in an invention may be assigned and legal title to the ensuing patent will pass to the assignee upon grant of the patent. If an assignment of rights in an invention is made prior to the existence of the invention, this may be viewed as an assignment of an expectant interest. An assignment of an expectant interest can be a valid assignment.

Figure 2.3 FilmTec reverse osmosis membrane filter.

Once the invention is made and an application for patent is filed, however, legal title to the rights accruing thereunder would be in the assignee, and the assignor-inventor would have nothing remaining to assign. In this case, if Cadotte granted MRI rights in inventions made during his employ, and if the subject matter of the ’344 patent was invented by Cadotte during his employ with MRI, then Cadotte had nothing to give to FilmTec and his purported assignment to FilmTec is a nullity. Thus, FilmTec would lack both title to the ’344 patent and standing to bring the present action.

The district court was of the view that if the Government was the assignee from Cadotte through MRI, the Government would have acquired at most an equitable title, and that legal title would remain in Cadotte. The legal title would then have passed to FilmTec by virtue of the later assignment, pursuant to Sec. 261 of the [Patent Act]. Sigma Eng’g v. Halm Instrument, 33 F.R.D. 129 (E.D.N.Y. 1963).

But Sigma, even if it were binding precedent on this court, does not stretch so far. The issue in Sigma was whether the plaintiff, assignee of the patent rights of the inventors, was the real party in interest such as to be able to maintain the instant action for patent infringement. Defendant claimed that the inventors’ employer had title to the invention by virtue of the employment contract which obligated the inventors to transfer all patent rights to inventions made while in its employ. As the court expressly noted, no such transfers were made, however, and the court considered any possible interest held by the employer in the invention to be in the nature of an equitable claim.

In our case, the contract between MRI and the Government did not merely obligate MRI to grant future rights, but expressly granted to the Government MRI’s rights in any future invention. Ordinarily, no further act would be required once an invention came into being; the transfer of title would occur by operation of law. If a similar contract provision existed between Cadotte and MRI, as MRI’s contract with the Government required, and if the invention was made before Cadotte left MRI’s employ, as the trial judge seems to suggest, Cadotte would have no rights in the invention or any ensuing patent to assign to FilmTec.

Because of the district court’s view of the title issue, no specific findings were made on either of these questions. As a result, we do not know who held legal title to the invention and to the patent application and therefore we do not know if FilmTec could make a sufficient legal showing to establish the likelihood of success necessary to support a preliminary injunction.

It is well established that when a legal title holder of a patent transfers his or her title to a third party purchaser for value without notice of an outstanding equitable claim or title, the purchaser takes the entire ownership of the patent, free of any prior equitable encumbrance. This is an application of the common law bona fide purchaser for value rule.

Figure 2.4 Schematic showing possible assignment pathways for Cadotte’s invention.

Section 261 of Title 35 goes a step further. It adopts the principle of the real property recording acts, and provides that the bona fide purchaser for value cuts off the rights of a prior assignee who has failed to record the prior assignment in the Patent and Trademark Office by the dates specified in the statute. Although the statute does not expressly so say, it is clear that the statute is intended to cut off prior legal interests, which the common law rule did not.

Both the common law rule and the statute contemplate that the subsequent purchaser be exactly that—a transferee who pays valuable consideration, and is without notice of the prior transfer. The trial judge, with reference to FilmTec’s rights as a subsequent purchaser, stated simply that “FilmTec is a subsequent purchaser from Cadotte for independent consideration. There is no evidence presented to imply that FilmTec was on notice of any previous assignment.” The court concluded that, even if the MRI contract automatically transferred title to the Government, such assignment is not enforceable at law as it was never recorded.

“the bona fide purchaser for value cuts off the rights of a prior assignee who has failed to record the prior assignment in the Patent and Trademark Office by the dates specified in the statute.”

Since this matter will be before the trial court on remand, it may be useful for us to clarify what is required before FilmTec can properly be considered a subsequent purchaser entitled to the protections of Sec. 261. In the first place, FilmTec must be in fact a purchaser for a valuable consideration. This requirement is different from the classic notion of a purchaser under a deed of grant, where the requirement of consideration was a formality, and the proverbial peppercorn would suffice to have the deed operate under the statute of uses. Here the requirement is that the subsequent purchaser, in order to cut off the rights of the prior purchaser, must be more than a donee or other gratuitous transferee. There must be in fact valuable consideration paid so that the subsequent purchaser can, as a matter of law, claim record reliance as a premise upon which the purchase was made. That, of course, is a matter of proof.

In addition, the subsequent transferee/assignee—FilmTec in our case—must be without notice of any such prior assignment. If Cadotte’s contract with MRI contained a provision assigning any inventions made during the course of employment either to MRI or directly to the Government, Cadotte would clearly be on notice of the provisions of his own contract. Since Cadotte was one of the four founders of FilmTec, and the other founders and officers were also involved at MRI, FilmTec may well be deemed to have had actual notice of an assignment. Given the key roles that Cadotte and the others played both at MRI and later at FilmTec, at a minimum FilmTec might be said to be on inquiry notice of any possible rights in MRI or the Government as a result of Cadotte’s work at MRI. Thus once again, the key to FilmTec’s ability to show a likelihood of success on the merits lies in the relationship between Cadotte and MRI.

In our view of the title issue, it cannot be said on this record that FilmTec has established a reasonable likelihood of success on the merits. It is thus unnecessary for us to consider the other issues raised on appeal concerning the propriety of the injunction. The grant of the preliminary injunction is vacated and the case remanded to the district court to reconsider the propriety of the preliminary injunction and for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

Notes and Questions

1. Recording of title. As noted in Section 2.1, Note 4, assignments of patents may be recorded at the Patent and Trademark Office. As provided in 35 U.S.C. § 261,

An interest that constitutes an assignment, grant or conveyance shall be void as against any subsequent purchaser or mortgagee for a valuable consideration, without notice, unless it is recorded in the Patent and Trademark Office within three months from its date or prior to the date of such subsequent purchase or mortgage.

This provision is a modified form of the familiar “race-notice” recording statute that applies to real estate transactions.Footnote 8 Unlike the comparable provision of the Copyright Act (17 U.S.C. § 205(d), discussed in Section 2.2), the second assignee of a patent may prevail over a prior, unrecorded assignee if the second assignee records first without notice of the earlier assignment unless the first assignee records within three months of the first assignment. An assignee of a patent thus has a three-month grace period in which to record its transfer without fear of being superseded by a second assignment. What is the reason for this three-month grace period, which exists neither in copyright nor real property law?

2. Inquiry notice. The court in FilmTec borrows the notion of “inquiry notice” from the law of real property recording. What is inquiry notice?Footnote 9 How does it differ from actual notice and constructive notice?

3. Present v. Future Grants of Patent Rights. The court in FilmTec explains that “the contract between MRI and the Government did not merely obligate MRI to grant future rights, but expressly granted to the Government MRI’s rights in any future invention. Ordinarily, no further act would be required once an invention came into being; the transfer of title would occur by operation of law.” That is, disregarding MRI’s failure to record the transfer, MRI’s present grant of rights in a future patent to the government (assuming that MRI had previously obtained the requisite rights from Cadotte) would automatically convey those rights to the government as soon as an invention was made.

A similar fact pattern arose in Stanford v. Roche, 563 U.S. 776 (2011) (reproduced, in part, in Section 14.1). In that case, a Stanford researcher who was obligated under Stanford’s policies to assign inventions to Stanford also signed an agreement assigning his future invention rights to Cetus Corp. while visiting the company to use its equipment. The Federal Circuit ruled for Cetus, reasoning that, under FilmTec, the researcher’s present assignment of future patent rights to Cetus automatically became effective when a patent application was filed, leaving nothing for him to assign to the holder of a future promise of assignment (i.e., Stanford). Stanford successfully sought certiorari on different grounds (whether the Bayh–Dole Act overrode these contractual provisions), and the Supreme Court affirmed the judgment for Cetus without reaching the assignment issue.

However, Justices Breyer and Ginsburg dissented (joined by Justice Sotomayor, who concurred in the judgment) on the ground that the Federal Circuit’s 1991 rule in FilmTec seemingly contradicted earlier precedent. Citing one 1867 treatise and a 1958 law review note, Justice Breyer proposed that before FilmTec, “a present assignment of future inventions (as in both contracts here) conveyed equitable, but not legal, title” and that this equitable interest “grants equitable enforcement to an assignment of an expectancy but demands a further act, either reduction to possession or further assignment of the right when it comes into existence.” In other words, the researcher’s present “assignment” of his future patent rights to Cetus would give Cetus an equitable claim to seek “legal title” once an invention existed or a patent application was filed. On this basis, Justice Breyer concludes,

Under this rule, both the initial Stanford and later Cetus agreements would have given rise only to equitable interests in Dr. Holodniy’s invention. And as between these two claims in equity, the facts that Stanford’s contract came first and that Stanford subsequently obtained a postinvention assignment as well should have meant that Stanford, not Cetus, would receive the rights its contract conveyed.

Despite Justice Breyer’s dissatisfaction with the holdings of FilmTec and Stanford v. Roche, their approach to future assignments still appears to be the law.Footnote 10 Which approach do you think most accurately reflects the intentions of the parties? What policy ramifications might each rule have?

4. Shall versus does. The result in Stanford v. Roche turns on the wording of two competing legal instruments – Dr. Holodniy’s assignments to Cetus and Stanford. As noted by the Federal Circuit in the decision below, Holodniy’s initial agreement with Stanford constituted a mere promise to assign his future patent rights to Stanford, whereas his agreement with Cetus acted as a present assignment of his future patent rights to Cetus, thus giving the patent rights to Cetus (583 F.3d 832, 841–842 (2009)). As explained by Justice Breyer in his dissent:Footnote 11

In the earlier agreement—that between Dr. Holodniy and Stanford University—Dr. Holodniy said, “I agree to assign … to Stanford … that right, title and interest in and to … such inventions as required by Contracts and Grants.” In the later agreement—that between Dr. Holodniy and the private research firm Cetus—Dr. Holodniy said, “I will assign and do hereby assign to Cetus, my right, title, and interest in” here relevant “ideas” and “inventions.” The Federal Circuit held that the earlier Stanford agreement’s use of the words “agree to assign,” when compared with the later Cetus agreement’s use of the words “do hereby assign,” made all the difference. It concluded that, once the invention came into existence, the latter words meant that the Cetus agreement trumped the earlier, Stanford agreement. That, in the Circuit’s view, is because the latter words operated upon the invention automatically, while the former did not.

What could Stanford have done to avoid this problem? How do you think the result of Stanford v. Roche affected the wording of university patent policies and assignment documents in general?Footnote 12 Given this holding, should an assignment agreement ever be phrased in any way other than “Assignor hereby grants to Assignee … ”? Was Dr. Holodniy himself at fault in this situation? What, if anything, should he have done differently?

5. Breadth of employee invention assignments. As noted in the introduction to this section, employers who wish to obtain assignments of the inventions created by their employees must do so pursuant to written assignment agreements. But how broad can these assignments be? In Whitewater West Indus. v. Alleshouse, 2020 U.S. App. LEXIS 36394 (Fed. Cir. 2020), the Federal Circuit reviewed an employee assignment agreement that contained the following provision:

a. Assignment: In consideration of compensation paid by Company, Employee agrees that all right, title and interest in all inventions, improvements, developments, trade-secret, copyrightable or patentable material that Employee conceives or hereafter may make or conceive, whether solely or jointly with others:

(a) with the use of Company’s time, materials, or facilities; or (b) resulting from or suggested by Employee’s work for Company; or (c) in any way connected to any subject matter within the existing or contemplated business of Company

shall automatically be deemed to become the property of Company as soon as made or conceived, and Employee agrees to assign to Company, its successors, assigns, or nominees, all of Employee’s rights and interests in said inventions, improvements, and developments in all countries worldwide. Employee’s obligation to assign the rights to such inventions shall survive the discontinuance or termination of this Agreement for any reason.

This provision, on its face, appears to require not only that current employees assign their inventions to the company (a typical provision in employment agreements), but also that former employees continue to make such assignments indefinitely in the future, so long as such inventions are “in any way connected to any subject matter within the existing or contemplated business of Company.” Needless to say, this provision is quite aggressive.

Richard Alleshouse, a designer of water park attractions, was hired by Wave Loch, Inc., a company operating in California, in October 2007. In September 2008, Alleshouse signed a Covenant Against Disclosure and Covenant Not to Compete containing the above assignment clause. In 2012, Alleshouse left Wave Loch to cofound a new company in the same line of business. There, he continued to develop and patent features of surfing-based water park attractions. In 2017, Wave Loch (through its successor Whitewater West) sued Alleshouse for breach of contract and correction of inventorship, seeking to acquire title to three patents on which Alleshouse was listed as a co-inventor following his departure from Wave Loch.

In evaluating Wave Loch’s claim, the Federal Circuit considered California Business and Professions Code § 16600, which states: “Except as provided in this chapter, every contract by which anyone is restrained from engaging in a lawful profession, trade, or business of any kind is to that extent void.” This statutory provision has traditionally been interpreted to prohibit companies from imposing noncompetition restrictions on former employees. In this case, however, the Federal Circuit extended its reach to prohibit assignments of future IP rights not based on the company’s own IP. In assessing the over-breadth of the provision, the court noted that:

No trade-secret or other confidential information need have been used to conceive the invention or reduce it to practice for the assignment provision to apply. The obligation is unlimited in time and geography. It applies when Mr. Alleshouse’s post-employment invention is merely “suggested by” his work for Wave Loch. It applies, too, when his post-employment invention is “in any way connected to any subject matter” that was within Wave Loch’s “existing or contemplated” business when Mr. Alleshouse worked for Wave Loch.

Under these circumstances, the court invalidated the assignment provision, reasoning that it “imposes [too harsh a] penalty on post-employment professional, trade, or business prospects—a penalty that has undoubted restraining effect on those prospects and that a number of courts have long held to invalidate certain broad agreements with those effects.”

Interestingly, Wave Loch cited Stanford v. Roche in its defense, arguing that the court there interpreted § 16600 to uphold the invention assignment provision used by Cetus. The Federal Circuit rejected this argument, however, stating that in Stanford, unlike Whitewater, “there was simply no evidence of a restraining effect on [the researcher’s] ability to engage in his profession.” But as pointed out by Professor Dennis Crouch, “The weak point of the Federal Circuit’s decision [in Whitewater] is that it is seemingly contrary to its own prior express statement [in Stanford] that ‘section 16600 [applies] to employment restrictions on departing employees, not to patent assignments.’”Footnote 13

Which view do you find more persuasive? Should Alleshouse have been required to assign his post-departure patents to Wave Loch? What would the result be in a state that did not have an analog to California’s § 16600? Should this question be resolved under Federal patent law?

6. When does an assignable invention exist? Another twist relating to employee invention assignments involves the point in time when an “invention” actually comes into existence and can thus be assigned. In Bio-Rad Labs, Inc. v. ITC and 10X Genomics (Fed. Cir. 2021), two employees each agreed to assign to Bio-Rad, their employer, any IP, including ideas, discoveries and inventions, that he “conceives, develops or creates” during his employment. Both employees left Bio-Rad to form 10X Genomics, which competed with Bio-Rad. Four months later, 10X began to file patent applications on technology that the employees had worked on while at Bio-Rad. The employees claimed that, while their work at 10X was related to their work at Bio-Rad, they did not actually “conceive” the inventions leading to their patents until after they had joined 10X. The Federal Circuit, applying California employment and contract law, agreed, holding that the assignment clause in the Bio-Rad agreements related to “intellectual property” and that an unprotectable “idea,” even if later leading to a patentable invention, was not IP and could thus not be assigned. That is, the court found that the assignment duty under the agreement was “limited to subject matter that itself could be protected as intellectual property.” If this is the case, then why did the Bio-Rad agreement expressly call for the assignment of “ideas” in addition to inventions and other forms of IP?

Figure 2.5 Richard Alleshouse was the product manager for Wave Loch’s FlowRider attraction, shown here as installed on the upper deck of a Royal Caribbean cruise ship.