Introduction

In the first part of this book (Chapters 3–7) I outlined a personal perspective and approach to the dynamics of human long-term coevolution with the environment, grounded in the evolution of human cognition. In Chapter 8 I have presented a narrative indicating the perspective on the history of human–environmental coevolution that this approach leads to, and in Chapter 9 I presented an outline conception of the interaction between society and its environment in terms of dissipative flow structures. Chapter 10 presented a more detailed case study of the dynamics of long-term evolution in a socioenvironmental system. In Chapter 11 I added a theoretical underpinning to that perspective and Chapters 12 and 13 presented my approach to the process of invention that is at the core of social and technological change. In Chapter 14, I showed how modeling dynamical systems can help us understand the emergence of urbanization.

These chapters have tried to pave the way for a focus on another central theme of the book: the present and its relationship to the future. In this part of the book, I will move our focus from the distant past toward the more recent past, the present, and the future. Chapters 16–18 argue that the information and communications technology revolution is an underestimated accelerator of the sustainability conundrum in which we find ourselves. Chapters 19–21 are dedicated to a discussion of potential futures.

The Rise of Western Europe 600–1900

To prepare the way, I will first present the last 1,500 years or so of western European history from the dissipative flow structure perspective. During that millennium and a half, we see a gradual strengthening of the urban (aggregated) mode of life, but this millennial tendency has its ups and downs and manifests itself in different ways. A second long-term dynamic is that of European expansion and retraction. Both reflect different ways in which the European socioeconomic system strengthened itself vis-à-vis the external dynamics that it confronted. To quantify these attributes, we will emphasize changes in the following proxies, where available:

The demography of the area concerned: relative population increases and decreases;

The spatial extent of European territorial units, as a measure of the area that a system can coherently organize;

The spatial extent and nature of trade flows as a measure of the information-processing potential between the center and the periphery, and thus of the area from which raw resources are brought to the system – its material footprint;

The density and extent of transport (road, rail, water) and communication (telephone, etc.) systems as a proxy for the density of information flows;

The degree and gradient of wealth accumulation in the system, as an indicator of innovation and the value gradients between the center and its periphery;

The innovativeness of particular towns, regions, and periods.

Many of these proxies cannot comparably be measured for each and every historical period and region. Moreover, they operate at different rates of change. But proxies are for the moment all we have if we want to cover the whole period. For subsets of it, interesting datasets are found in Piketty (Reference Piketty, Saez and Stantcheva2013) but also in Le Roy-Ladurie (Reference Le Roy Ladurie1966 [1974], Reference Le Roy Ladurie1967 [1988]), Slicher van Bath (Reference Slicher van Bath1963), and many others involved in agrarian history, particularly represented in the French journal Annales: Économies, Sociétés, Civilisations.

The Dark Ages

After the end of the Roman Empire we observe across Europe a weakening of society’s structure and coherence (e.g., Lopez Reference Lopez1967). Between 600 and 1000 CE, the fabric of society reached a high level of entropy (both in the sense of growing disorder and in the sense of reduced dissipation of the flow structure governing the dynamic) in western Europe, where the traditions of Greco-Roman urban culture were only conserved to a minimal extent. In South-Eastern Europe, under the Byzantine emperors, appropriate decentralization ensured that more of the culture developed for another millennium.

We will in this chapter mainly focus on western Europe. In this period, there was an enormous loss of knowledge, in crafts and trades for example, as well as an abandonment of infrastructure. The flow structures exchanging organization for energy and matter were limited to the immediate environment. Trade and long-distance contact virtually disappeared, towns saw their population dwindle (the city of Arles was for some time reduced to the perimeter of its Roman arena), and most villages were abandoned. Society fell back on local survival strategies and much of Roman culture was lost. Only the Church maintained some of the information-processing skills it had inherited, especially writing and bookkeeping, and a semblance of long-distance interaction.

The First Stirrings: 1000–1200

This was a period of oscillation between different small systems, in which cohesion alternated with entropy even at the lowest levels. In Northern Europe, trade connections forged in the (Viking) period before 1000 CE led to the transformation of certain towns into commercial centers, later loosely federated into the Hanseatic League. But these towns remained essentially isolated islands in the rural countryside, linked by coastal maritime traffic.

Duby’s classic study (Reference Duby1953) shows how, from about 1000 CE, society in Southern France began to rebuild itself from the bottom up. Although the urban backbone of the Roman Empire survived the darkest period, a completely new rural spatial structure emerged, even relatively close to the Mediterranean. There, in a couple of centuries of local competition over access to resources, various minor lords climbed the social ladder by conquering neighboring resources and positions of potential power, leading to the emergence of a new (feudal) social hierarchical structure.

The local leaders with the best (information-processing and military) skills were able to attract followers by providing protection for peasants who bought into the feudal system. The peasants in turn provided surplus matter and energy to support a small army and court. In the process, more wealth accrued to the favored, and we see the resurgence of a (very small and localized) upper class with a courtly culture in the so-called “Renaissance of the twelfth century that included tournaments, troubadours, and other (mostly religious)” artistic expressions in Southern France and adjacent areas. A similar process occurred in the Rhineland, where a separate cultural sphere (Lotharingia, named after Charlemagne’s son Lotharius who inherited this part of his father’s empire) developed on both banks of the river. Further east, in Germany, this period saw the decay of whatever central authority the Holy Roman Empire had and the rural colonization of Eastern Europe. At this time parts of Europe began to look outward: it was the time of the crusades against Islam (1095–1272) that culminated in 1204 in the (short-lived) conquest of Constantinople, which brought large amounts of information to western Europe in a – for the times – very efficient manner.

The Renaissance: 1200–1400

Three major phenomena characterized the next period: (1) the establishment of a durable link between the southern and the northern cultural and economic spheres, (2) the major demographic setback of the Black Death in the fourteenth century, and (3) the beginnings of the Italian Renaissance. The link between south and north was established in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, overland from Italy to the Low Countries via Champagne, and then connecting with the maritime British and Hanseatic trade systems. In the thirteenth century this connection became the main axis of a continent-wide trading and wealth creation network, enabling urban and rural population growth (Spufford Reference Spufford2002) and eventually driving rural exploitation in many areas to the limits of its carrying capacity, as well as pushing farming out toward more distant and less fertile or less convenient areas.

The impact of the bubonic plague was very uneven. Where it hit badly, it profoundly affected both cities and the surrounding countryside, bringing people from the periphery into the traditionally more populous urban areas (where the plague had hit hardest), thus increasing both the degree of aggregation of the population and its average per capita wealth (see Abel Reference Abel1966). Other profound changes occurred in the cultural domain, including a reevaluation of the role of religion, life and death, society and the individual, together shaking society out of its traditional ideas and patterns of behavior. (Some of these are mentioned in Chapter 3.)

These phenomena contributed to a localized era of opportunity in Northern Italian cities, where the interaction of cultural, institutional, technical, and economic inventions led to a uniquely rapid increase in the information-processing gradient between the urban centers and the rest of the continent. In this Renaissance, architecture and the arts flourished, while the foundations were laid for modern trade and banking systems. Padgett (Reference Padgett, Arthur, Durlauf and Lane1997), for example, describes brilliantly how financial and social innovations went hand in hand to transform the Florentine banking system, drawing in more and more resources and investing them in an ever–widening range of commercial and industrial undertakings that, in turn, transformed practices in these domains. Long-distance trade reemerged as a major force in development, for example between Venice and the Levant; the travels of William of Rubruck, John of Montecorvino, and Giovanni ed’ Magnolia are examples of these contacts, from the mid-thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries.

Many of the ideas developed in northern Italy were relatively quickly adopted in the trading centers in the Low Counties, such as Ghent and Bruges, which became rich and powerful based on the wool and cloth trade with England.

The emergence of a bourgeoisie in these places set the scene for systemic change: from this time onward, reaching the top of the heap was limited to geographic areas where urbanization led to concentrations of more – and more diverse – resources, as well as more effective information processing because towns were linked in Europe-wide information flows.

The Birth of the Modern World System: 1400–1600

This period marks the central phase in the continent-wide transition from a rural, often autarchic, barter economy to a monetized economy driven by towns, in which craft specialization and trade set the trend (Wallerstein Reference Wallerstein1974–1989). The transition introduced fundamentally different system dynamics. The dominant cities are increasingly market- and trade-based heterarchical structures, as opposed to the egalitarian and hierarchical ones in the rural landscape. Simon (Reference Simon1969) defines such structures as those emerging, in the absence of hierarchy and overall control, from the interaction of individual and generally independent elements, each involved in the pursuit of separate goals, and with equal access to (incomplete) information; competition for resources characterizes such organizations. As we saw in Chapter 11, contrary to hierarchical systems, heterarchical ones do not strive to optimize behavior; they can link much larger numbers of people, especially if they are organized as networks with nodes, and they are more flexible.

In this first phase of urban dominance, the world of commerce and banking expanded across different political entities, cultures and continents. Much of both southern and northern Europe, including Britain, Scandinavia, and the Baltic, were now integrated into the European world system. Rural areas saw their interaction with towns increase. Cities began to look attractive to farmers in an overpopulated countryside continually disturbed by armies acting out others’ political conflicts, and this led to a wave of rural emigration to towns, relieving the population pressure in the countryside and keeping the urban labor force cheap. That in turn enabled industrial expansion.

This period is the heyday of city power. Urban centers were not controlled by political overlords; rather, they controlled these overlords’ purse strings, as in England (London) and the Netherlands (Amsterdam). Urban elites put to work the enormous gains in information-processing capacity made during the Renaissance. Through relatively unregulated commerce and industry, commercial houses (e.g., the Fuggers) amassed enormous wealth, used it to bankroll the political conflicts and wars that disrupted the continent, and thus extended their economic and political control over much of the continent. To this effect, they created extensive information-gathering networks linking every important commercial, financial, and political center.1

This is also the period of the first voyages to other continents. By investing in these distant parts, European traders added new areas along the information-processing gradient, in which the commonest European product (such as glass beads) had immense value in faraway territories, while the products from those regions (such as spices) had a high value in the traders’ homelands. The huge and immediate profits made up for the risks, and this long-distance trade initiated for the trading houses centuries of control over an increasingly important resource-rich part of the world. As a result, this period has the steepest information gradient from the center of the European World System to its periphery, and the steepest value gradient in the reverse direction. But toward the end of the period that gradient began to level off in the European core, as cities in the hinterland, and eventually territorial overlords, began to seriously play the same game.

The Territorial States and the Trading Empires: 1600–1800

The rulers of Europe had inherited legitimacy, or something approaching it, from the Roman Empire, but that did not pay the bills. Their need to keep up a certain status was a financial handicap until they could leverage their legitimacy against financial support by exchanging loans for taxes as their principal source of income. A degree of territorial integration and unity was achieved in many areas by 1600,2 transforming the heterarchical urban systems into hybrid heterarchical-hierarchical ones including both towns and their hinterlands.

The regions that first achieved this (Holland, England, and Spain) had the most extensive long-distance trade networks providing the steady income necessary to maintain rulers’ armies and bureaucracies. As a result, the city-based economic system was transformed into one that involved the whole of the emerging states’ territory. Inevitably, the value gradient leveled out as the Europeans in the colonies assimilated indigenous knowledge and shared their own knowledge with the local populations, but this was for some time counterbalanced by the discovery of new territories, the introduction of new products in Europe, the improvement of trade and transport, and the extension of the reach of the trading empires. But ultimately the leveling of the information gradient led toward independence, as in the case of the USA, or, as in the East Indies or Africa, to the transformation of the trading networks into colonies under military control. These saw the local production of a wide range of necessities for the colony as well as western-controlled production systems for products needed in Europe, and a degree of immigration from Europe. As a result, the European core and the colonies became economically more dependent upon one another.

The same leveling off occurred in Europe as more people began to share in the production of wealth and its benefits. The profits from long-distance trade enabled an increase in the industrial base of the main European nations, achieved by involving more and more (poor) people in production and transformation of goods. The tentacles of commerce and industry spread into the rural hinterlands, aided by the improvement of the road systems. As a result of both these systemic changes, the flow structure that had driven European expansion became vulnerable to oscillations between rich and poor, separated by a growing wealth gap.

An important milestone in this process, which I consider in Chapter 18, is the Treaty of Westphalia (1648), which established the structure of European international relations for several centuries, until very recently. It was based on the principle that rulers of nations would not interfere in other rulers’ territories, and was thus a way to help stability in “interesting times.”

Using the term that I introduced in Chapter 7, one could say that with this event the European nations solidified themselves as Bénard cells, independent, coterminous units that were each driven by dissipative flows of energy and information.

The Industrial Revolution and its Aftermath: 1750–2000

But as the overall structure of the European system began to fray at the edges, the massive introduction of fossil energy as a resource and the concomitant Industrial Revolution reestablished the information gradient across the European empires and the value gradient between the colonies and the heartland. The resulting shift was profound (Figure 15.1). It gave European dominance a new lease of life, but at the expense of major changes. From a zone in which internal consumption of high-value goods imported from elsewhere generated most of the wealth, Europe became the mass-producer of a wide range of goods for export to the rest of the world.

Figure 15.1 With the discovery and use of fossil energy and the Industrial Revolution that followed, our global energy consumption exploded. At present, whereas humans need about 100 Wh for their biological functioning, US per capita energy use is around 11,000 Wh. At present, per capita, an average North American uses 1.5 times the energy of an average Frenchman, 2.2 times the per capita energy of Japan or Britain, 2.6 times the energy of a German, 5 times the energy of a South African, 10 times the energy of a Chinese person.

To maintain this system, it had to create wealth in the periphery that would allow the local populations to acquire European goods. It did so by creating in the colonies large-scale production systems for raw materials that were transformed in Europe into products sold to the same colonies. Thus, the status of these colonies changed – from producers of goods that had relatively little value locally but high value in Europe, to areas mass-producing low value goods for export to Europe and serving as markets for low-value European products. Maintaining this system required improved political control over the colonies concerned, as it brought large numbers of local people into the system as low-paid labor.

In Europe, the invention of new technologies in both the core and the periphery created much wealth, but ultimately undermined the flow structure by disenfranchising large groups of people. Industrialization tied a large working class into (mechanized) production in low-paid, often dangerous, jobs that gave little satisfaction.3 Social movements were quick to emerge in the core (from 1848), and up to World War II. Countries that had not been part of the early flow structure aspired to create similar dynamics. The French thus occupied areas of Africa and Southeast Asia. Italy, Germany, Japan, and Belgium – born as nations in the late nineteenth century – had to satisfy themselves with the leftovers of the colonial banquet. This contributed to the causes of the two world wars: these countries sought expansion in Europe (and in Japan’s case in Asia) because it was denied them elsewhere.

Finally, between 1940 and 2019, the control over large parts of the world that Europe had thus far enjoyed spread to North America, Australia, Japan, South Africa, and more recently to Southeast Asia, China, and India. Europe and the United States are no longer in sole control of the information gradient responsible for the continued wealth creation, innovation, and aggregation of the World System, but have to compete with these other regions. The world has become multipolar.

Summary

I argue here that the European system has undergone three major transformations to date, dividing its history into four phases. In the first phase, after a predominantly flat, entropic, period (c. 800–1000 CE), in which whatever flow structures there were occurred essentially at the scale of individuals’, families’, or villages’ subsistence strategies, we see (roughly between 1000 and 1300) structures that involve information processing by larger (though still small) local units; most of these small rural principalities emerging in Southern Europe, but in northern Europe a few urban ones (the Hanseatic towns) emerged as well. Later in the period, several such rural flow structures were often subsumed under a larger one, leading to feudal hierarchies. But the hierarchical structure of the information networks structurally limited their opportunities of expansion (see van der Leeuw & McGlade Reference van der Leeuw, McGlade, van der Leeuw and McGlade1997).

The second phase (c. 1200–1400), was dominated by the death and later a new aggregation of the population in both old and new towns as a result of the Black Death, which caused innovation to take off. It drove a rapid expansion of the urban interactive sphere through long-distance trade and communication. The resulting urban networks that emerged from c. 1400 were independent of the rural lords and probably had a novel, heterarchical information processing structure (see van der Leeuw & McGlade Reference van der Leeuw, McGlade, van der Leeuw and McGlade1997), facilitating the growth of interactive groups and the systems’ adaptability. In the next two centuries, these cities drove the establishment of colonial trading networks.

But in the sixteenth century that dynamic led to a second tipping point inaugurating a third phase: the beginnings of the European World System, initiated by the discoveries of other continents by European seafarers. New resources were identified in faraway places and fed the accumulation of wealth that was going on. Between c. 1600 and c. 1800, urban and rural systems were forced to merge by rural rulers who needed to acquire in the towns the funds to increase control over their territories. This led to the formation of (systemically hybrid) states and the transformation of the urban trading networks into colonial exploitation systems. Toward the end of this period (c. 1800), these flow structures seemed to reach their limits: innovation stalled in the cities, and the energy and matter flows from the colonies were limited by the structure of their exploitation systems. Europe had reached a third tipping point.

At that point (c. 1800) a new technology inaugurated a fourth phase – the use of fossil fuel to drive steam engines, lifting the energy constraint that had limited the potential of all western societies thus far. The innumerable innovations that followed enabled transformation of the European production system at all levels, rapidly increasing the information-processing and value gradients across the European empires again. Girard (Reference Girard1990) outlines how in that process, the term “innovation” changed its value, from something to be ignored or even despised, to the ultimate goal of our societies. As part of this process, our societies became so dependent on innovation that one may currently speak of an addiction that resembles a Ponzi scheme in that innovation has to happen faster and faster to keep the flow structure intact.

I insist on emphasizing two lessons learned from this history. First, wealth discrepancy may well be a societal counterpart to the environmental planetary boundaries that were highlighted in the paper by Rockström et al. (2009), as it seems that wealth discrepancies were at their widest just before the three major transitions in European history: the Black Death, the discovery of the rest of the world, and the Industrial Revolution.

Secondly, in hindsight the progression from the agricultural societies of the Middle Ages to the trading empires of the early modern world, and ultimately to the industrial and post-industrial economies of the last century or so may seem inevitable, but like any story, or history, it is in effect a post-facto narrative that reduces the dimensionality and complexity of what really happened.

From the ex-ante perspective that we are introducing here, at each of the three transition moments mentioned European societies could potentially have engaged in different trajectories, and this continues to be true for the present. Rome could for example theoretically have followed a different trajectory in the second century CE. History is not inevitable. There are times when processes dominated by strong drivers make change very unlikely, and there are moments when unexpected events or people can indeed change the course of history. It is the thrust of this book that we seem currently to be living a moment in history that opens a window of opportunity for the world to change. Hence there are choices to be made. Making those choices requires that as individuals and as a society we retake responsibility for our collective future, instead of leaving that responsibility to a small group of people who are currently, knowingly or not, misusing it.

Another important thing to conclude from all this is that globalization is not new at all, but has been going on since the sixteenth century. We need to take this fact into account when we think and act in the present. In effect, all that has happened is that we have entered a new stage of globalization; a stage that has interesting parallels with the sixteenth- to eighteenth- century colonization of large parts of the world – in that trade was enabled to expand as the political structure of Europe was very fragmented, allowing nascent trade organizations such as the Dutch and English West and East Indies companies to drive the spread of European ideas worldwide. In some ways, states latched onto these trade organizations to bring wealth into their coffers, for example by issuing permits to pirate vessels of enemy nations.

The Changing Roles of Government and Business

I would like to use this section to look more closely (but still in general terms) at the current phase of globalization from a historical perspective, with an emphasis on the respective roles of government and business. As we have seen, beginning in around 1800, the introduction of ways to massively use fossil energy, and the Industrial Revolution it enabled, changed both the economy of European countries and of their colonies. In a nutshell, as the European countries developed industrial mechanization, they also changed their interaction with their colonies, developing governance, plantations, and markets for European products.

Thus, until around 1800 there was an enterprise-driven low-volume but high value flow from the colonies to Europe, with very little in the way of organizational and information processing capacity flowing toward the colonies. After that date, the flow structure involved national administrations, which triggered a much more important flow of organization and information-processing toward the colonies, transforming the latter into western-administered and -run territories owing to an influx of western-educated men and women.

This system essentially continued and expanded during all of the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century, facilitated by the discovery of oil, the spread of electricity, and the invention of new modes of transportation (railroads, steam- and later oil-powered shipping, aviation, etc.) and communication (mail, telegraph, telephone, telex), facilitating larger and larger, faster and faster flows of information between the European countries and their colonies, and thus slowly integrating those colonies into the overall information-processing apparatus of their home countries. It is important to be aware that during the nineteenth century and up to World War II, in the colonies business and government worked together and kept each other in balance.

Decolonization began in the late nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century in Latin America, and followed in the forty years after World War II in very large parts of Southeast Asia and Africa. It severed the political link between European countries and their colonies, and cut the ex-colonies off from the information flow that had until then “organized” them. But it did not stop the trade flows between the European countries and their ex-colonies. It merely separated (once more) the governmental and the commercial domains, allowing business a freer hand in the new overseas nations after their independence, while governance was still in its infancy.

At the same time, the USA had achieved military and political dominance over much of the world, and because of its liberal philosophy facilitated, if not encouraged, the concentration of economic power in private hands. The so-called Pax Americana of the second half of the twentieth century enabled corporations – which equaled the economies of many countries in size – to dominate industrial production, trade, and communication, slowly leading to a situation in which they became as powerful, or more so, than most countries. In the process, some countries managed to organize themselves to achieve a rapid rise in wealth and economic power (Germany, Japan, Korea, later China and other countries in the BRICS grouping – Brazil, Russia, India, South Africa), often initiated by government-sponsored, large industrial and business clusters that captured markets owing to the initially much lower salaries than those paid in Europe and the USA. The world thus evolved into a multipolar communication and information flow structure.

For the moment, the main lesson to take away from this brief and superficial history is that we have not only seen balance of power shifts between countries, but also a recurring shift in the balance of power between governments and business, since the Reagan and Thatcher era (the early 1980s) to the advantage of business and finance. That development has also hugely increased the value and wealth differentials between the core and the periphery of the system (the haves and the have-nots), as recently brought to everyone’s attention by Piketty (Reference Piketty, Saez and Stantcheva2013), and thereby reduced the chances that outsiders could become insiders, creating an extraction-to-waste economy (in terms of raw materials, but also human capital) that is close to reaching (or has reached) its limits in the sense that our planet can no longer deal with it.

Because of the territorial limitations of governance, this system’s spread around the globe has enabled, but has also been driven by, the growth of large multinational corporations. The impact of these corporations outside the core of the western world has, slowly but surely, over the last century or so, incorporated regions that were culturally and socially fundamentally different into that extraction-to-waste economy and made that economy truly global – driving individuals, groups, and countries to gradually adopt mindsets, activities, and institutions that are compatible with its underpinning an urban and wealth-driven logic. In the last thirty years, this process has accelerated, and is now reaching the conurbations of China, Indonesia, India, and other countries.

Crises of the Twentieth Century

As part of this process, a number of fields of tension were generated that ultimately caused major crises. The first such to hit western society in the twentieth century was World War I. As we all know by now, it was triggered by a seemingly minor event, the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, which occurred after a spate of similar assassinations of princes and high nobility. It sparked a release of the tensions that had built up between four major societal configurations in Europe, the Austro-Hungarian, French, German, and British Empires, and inside these empires between rich and poor. The huge destruction it wrought in human and material capital reduced these tensions for a while. The next crisis, however, began not long thereafter in the financial domain, in 1929, being caused by the control of the financial markets by very few people, particularly in the USA. It triggered a major destruction of wealth, increased social tensions in the countries involved, and also coincided, in the USA, with major environmental destruction (the so-called dust bowl). The financial capital lost was not really reconstituted until the run-up to World War II, which was driven (in a revanchist way) by some of the same social tensions that had caused World War I, particularly in Germany.

After the war, a major restructuring of the western world was set in motion, entailing a new financial structure (Bretton Woods, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank), a new attempt at a global political structure (the United Nations), a new military structure (the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the Warsaw Pact, the Alliance of South-East Asian Nations, etc.), the opening up of trade flows worldwide (leading to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and the World Trade Organization, and more recently to regional customs unions such as the North American Free Trade Agreement, the European Union, and similar but less integrated regional pacts). Importantly but less visibly, this also caused a shift toward a material wealth model that exported the core of societal tensions from the western world to the rest of the Earth by using human and resource capital in the periphery to accumulate wealth in the western core of the system, thereby minimizing tensions in the western democracies. A large part of this development was driven by the technological innovations facilitated by the plentiful availability of fossil (and later to a limited extent nuclear) energy. These developments ultimately led to the current consumer society and helped create a period of relative social peace in the developed nations.

After about twenty years of rebuilding the parts of the world that had been destroyed by war, in the 1970s and 1980s unintended consequences of the new order, including the dismantling of the colonial empires, began to surface again in the west as well as elsewhere. In the financial domain, dealing with rapid growth in the financial system led to the abolition of the gold standard (1976), which was followed by the “big bang” (1986) that removed (national) policy constraints that had thus far kept the financial markets within bounds, in particular in the USA and Britain. The Reagan and Thatcher regimes contributed to the collapse and the change of regimes in Russia (1989) and in some of the western periphery of the Russian Empire, in countries that had been weakened by the unintended consequences of their communist philosophy of management. In a number of ex-colonies, a revolution of rising expectations led to profound regime changes (e.g., in Indonesia, India, Pakistan, Zimbabwe, and many others; much later South Africa) to the advantage of (small groups among) the original inhabitants.

Underneath all of this, and surfacing particularly from the 1980s onwards, globalization was a major driver of the process, on the one hand increasing trade and the wealth of the core as well as reducing regional risks by subsuming them under global ones, but on the other hand leading to more dependencies between different parts of the world, and thus increasing the chances that minor events in one place could have major consequences for the world system as a whole (the ‘butterfly’ effect).

Conclusion

From our information-processing dissipative flow perspective, globalization is the latest stage in a process driven by an imbalance between our global societies’ capacities to process energetic and material resources on the one hand and information on the other. Information-processing needs over time brought more and more people together, and this required more and more resources. In this process, the information-processing capacity of growing communities increased sublinearly with the number of people owing to the limitations of human short-term working memory and inefficiencies in alignment and communication. But the material and energetic flows increased at first linearly with the number of people, and later maybe even geometrically when the growth of group sizes required increasing investment in infrastructure. As a result, the resource needs of western society drove it to expand its extraction networks across the globe, but without concomitantly expanding the dimensionality of its information processing toolkit. Over an ever-widening area, the globe was exploited in the western way, disregarding the many dimensions of local information processing that were related to local customs, environments, challenges, solutions, and values. Integrating these was beyond the capacity of western societies’ information processing, and thus globalization proceeded on an increasingly narrow dimensional basis, around wealth, ever since the discovery and harnessing of fossil energy in the nineteenth century (coal) and twentieth century (oil and later gas) facilitated innovation and an expansion of the western value space. This expansion was based on an elaboration of the same set of core dimensions that had governed the west’s information processing earlier.

The forcible geographical expansion of western information processing was not able to integrate the very high number of different dimensions inherent in the different ways in which non-western populations processed their information. The western flow structure therefore spread across the world, maintaining its own ways of processing information, facilitated by a few shared languages worldwide: English, Spanish, and French. This rapidly widened the gap, worldwide, between the dominant (western) information processing system and the cultures and environments it confronted, and thus generated a rapidly growing tension between the available information processing and the kind of information processing that would have optimized local (natural and human) resource use, leading to an explosion of unintended and unanticipated consequences that ultimately caused a series of crises (which in my opinion will continue to occur with increasing frequency and amplitude).

Of course, this tension will impact differentially on the vulnerability, resilience, and adaptability of different scales of the system (Young et al. 2006). But the expansion of the western information-processing system will increasingly undermine societal diversity and the diversity in thought and action that has until now characterized the different cultures on Earth and acted as a buffer against their hyper-connectedness. And finally, I think it will limit, if not render impossible, the expansion of the value space that I discuss in Chapter 16.

It is my contention that these dynamics have not sufficiently been explored, in part because they have been looked at from a national or corporate perspective, in which expansion was viewed as an advantage because it increased financial and economic flows and values.4 In order to explore them properly, it is essential to take a global and holistic perspective, to develop a “Global Systems Science” that looks at the causes and effects of globalization at the scale at which the phenomenon happens, rather than only looking at the advantages of globalization for individual countries and companies in competition.

As I outline in Chapter 18, in the current age of big data gathering, the information needed for such an approach is fundamental to the continued existence of our societies, and its importance exceeds that of any national interests. We are beginning to see such collection, but it is essentially in private hands (of Google, Facebook, Tencent, and others like them), while governments do not really seem able to compete on the same scale because (apart from the superpowers who are mainly collecting it for defensive and military purposes) they still maintain a national perspective.

The Present Conundrum

A central theme of the book is the relationship between the present and the future, and in particular the conundrum in which we find ourselves in the modern world with respect to our environment and the survival (or not) of our current ways of life in a globalizing world. Let us therefore take a look at some of the trends that characterize our current societies globally. Doing so will rapidly show us that although greenhouse gas emissions have been targeted by international politics as the focus of our battle against the destruction of our environment, this is woefully insufficient and actually misleading because it ignores the roots of the problem and oversimplifies the challenge.1

If we view the current challenges as societal rather than environmental in origin, there are a number of essentially societal dynamics that are threatening to exceed their own safe operating spaces: demography, food security, financial stability, wealth distribution, urbanization, etc. Fortunately, as part of the efforts of the United Nations (UN) to define sustainable development goals (SDGs) in 2015 and to propose an agenda to reach those goals, the realization has quickly grown in the scientific community that, indeed, the challenge is in large part a societal one (see Chapter 19 for a more detailed discussion of the SDG research effort). Moreover, the recent focus on SDGs has shifted efforts toward viewing the core sustainability challenges through the lens of a multidimensional systemic approach. This is beginning to have an impact on governments as well, with efforts to coordinate ministries and agencies now also including central government functions, such as the ministries of finance, planning, and/or the prime minister’s office. Yet the engagement of the social science community is still in its infancy compared with that of the natural and life sciences. For one, because it was initially called upon to respond to issues that the natural sciences defined, it was as it were backed into its main topic: societal dynamics. As a result, much effort has been spent by social scientists studying such topics as climate and society, water and human needs, food (in)security, rather than focusing on studying the internal dynamics of society that have brought us to the current situation. Moreover, there has to date not been enough of a coordinated effort at developing the results of different sectoral approaches to dynamics in various societal domains into a more holistic, scientifically coherent one, based on intellectual fusion between the efforts of disciplinary communities. Neither have the scientific and the economic, financial, and political communities looked closely at the role of unintended, unanticipated consequences of earlier choices.

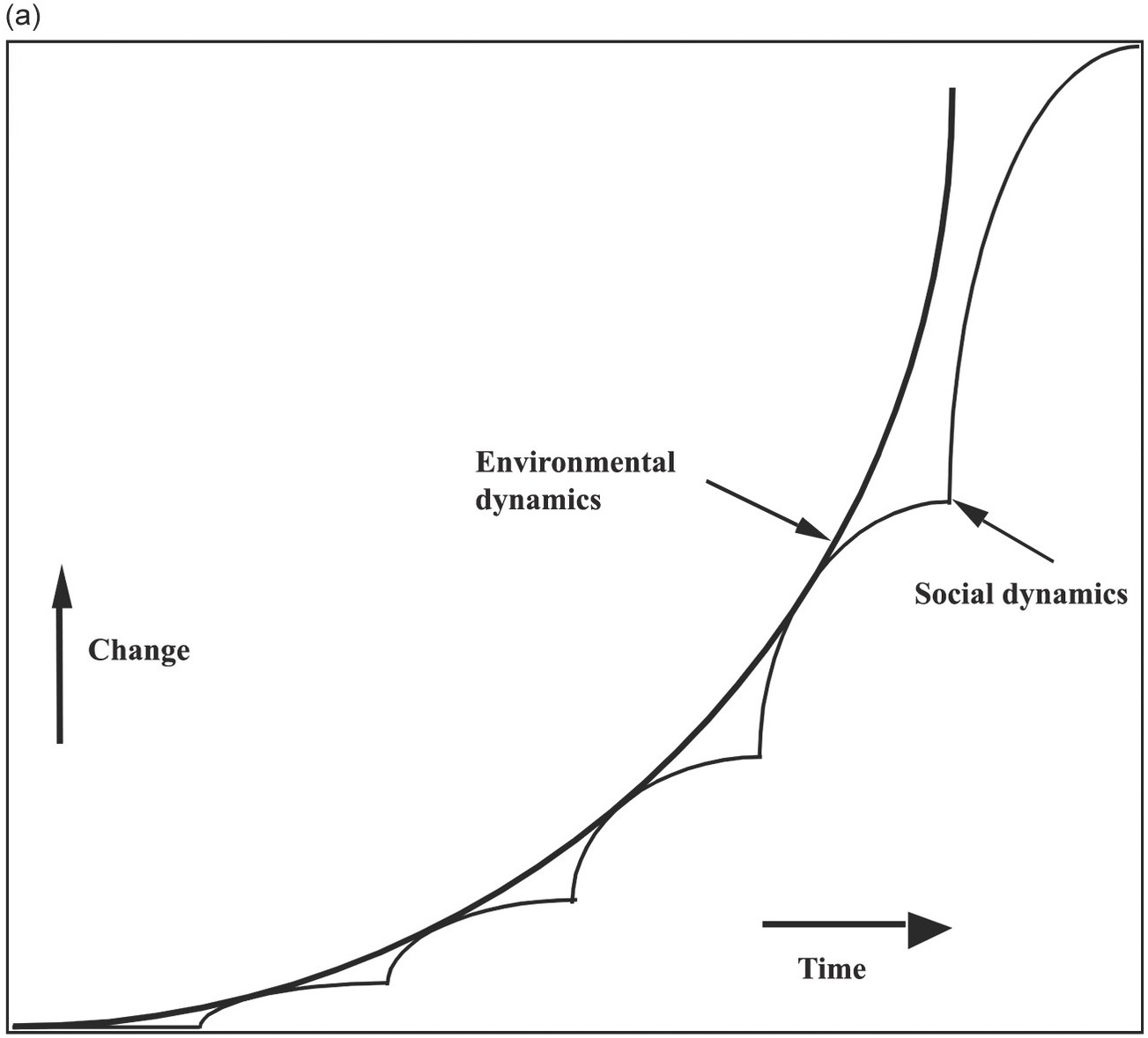

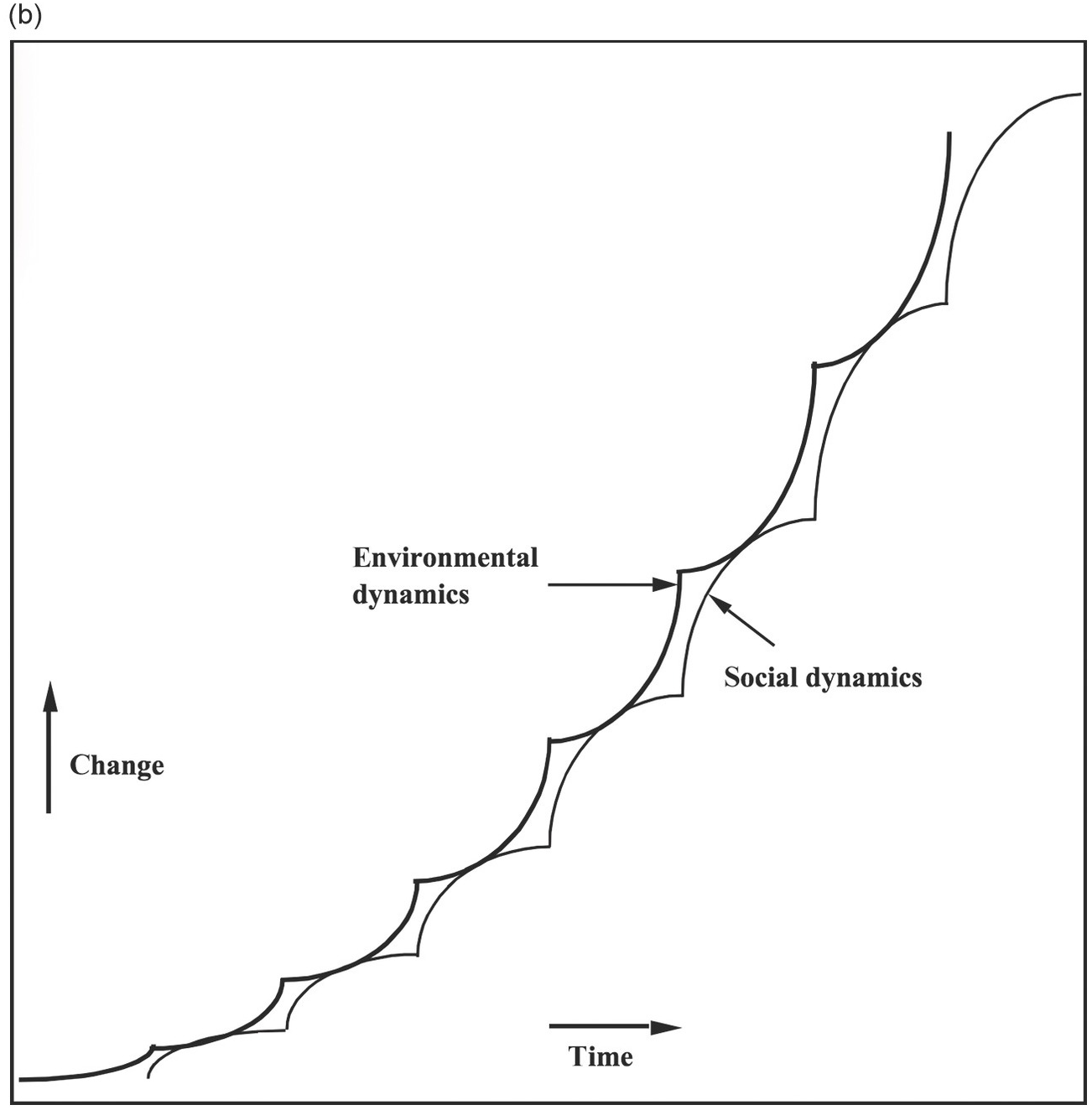

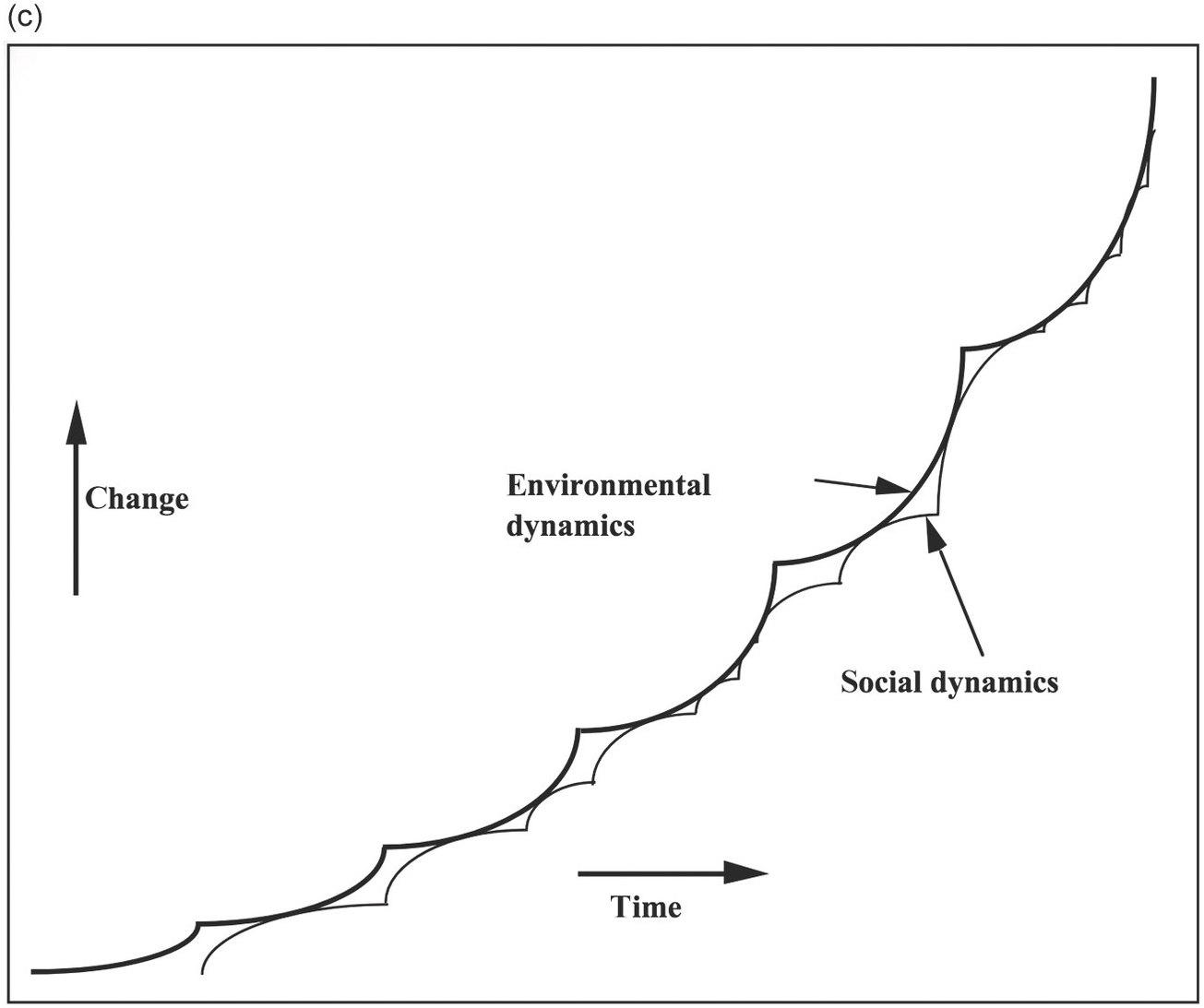

Briefly discussing some of the main sustainability challenges just mentioned, this chapter probes the depth to which an analysis of our current multidimensional predicament must go. It emphasizes the complexity of the challenge and the need to begin to view it from a complex systems perspective. Finally, it will emphasize that our current situation is due to the effects of unexpected and unanticipated consequences of earlier choices made by our western societies, which are in my opinion the root cause of tipping points throughout history. With that perspective, a “crisis” or “tipping point” is a (usually temporary) situation in which the information-processing capacity of a society is no longer able to deal with the highly complex dynamics in which the system finds itself owing to the shift in risk spectrum that it has undergone over time.

The Environment

Our actions over many centuries have ultimately transformed our environment to the point that the relative stability of the Earth system dynamics that we have, as humans, enjoyed over some 10,000 years, may be coming to an end within this century. Over the last hundred years or so, many indicators of the expansion of the socioeconomic system, both globally and locally, have gone exponential, and so have indicators of its impact on the environment.

Steffen et al. (Reference Steffen, Sanderson and Tyson2005, Reference Steffen, Richardson, Rockström, Cornell, Fetzer, Bennett, Biggs, Carpenter, de Vries, de Wit, Folke, Gerten, Heinke, Mace, Persson, Ramanathan, Reyers and Sörlin2014) illustrate that transformation in a single figure (Figure 2.1). In the last thirty years, moreover, numerous signs have emerged that our current society is close to hitting, or actually has hit, a series of planetary environmental risk barriers (Rockström et al. 2009) (Figure 2.2). After some thirty years of research on changes in the environment that saw our challenge essentially as an environmental one, awareness is growing that we are in effect dealing with a societal challenge. After all, society defines its environment, identifies environmental challenges, and proposes solutions for them. Societal action is therefore the only kind of action that can have caused, and may change, the current trend.

This leads me to argue that as scientists we may until recently have been looking under the streetlights to find the key that we have lost somewhere in the dark beyond the reach of those streetlights. To determine why this has happened would be a highly interesting and important topic of research in its own right. Instead of mainly looking at socioenvironmental dynamics to see where there are dangers lurking, and how we might mitigate these so that we could retain our current western lifestyle, we should have been looking more closely at the societal dynamics that created the current conundrum and how we might change that lifestyle.

Might some of the signs that Steffen has collected also indicate that we are crossing, or at least approaching, a set of societal planetary boundaries? In this chapter I will try to explore that question. I will briefly enumerate a number of the dimensions in which our societies are threatening their own safe operating space. Most, if not all, of these are known, but because of the disciplinary and sectoral fragmentation of our worldview and our science, many of them have not sufficiently been linked in a holistic perspective to see what they really mean for our future. Others have not been discussed because they derive from such fundamental values and assumptions in our culture that they are our sacred cows.

Global Demography and Health

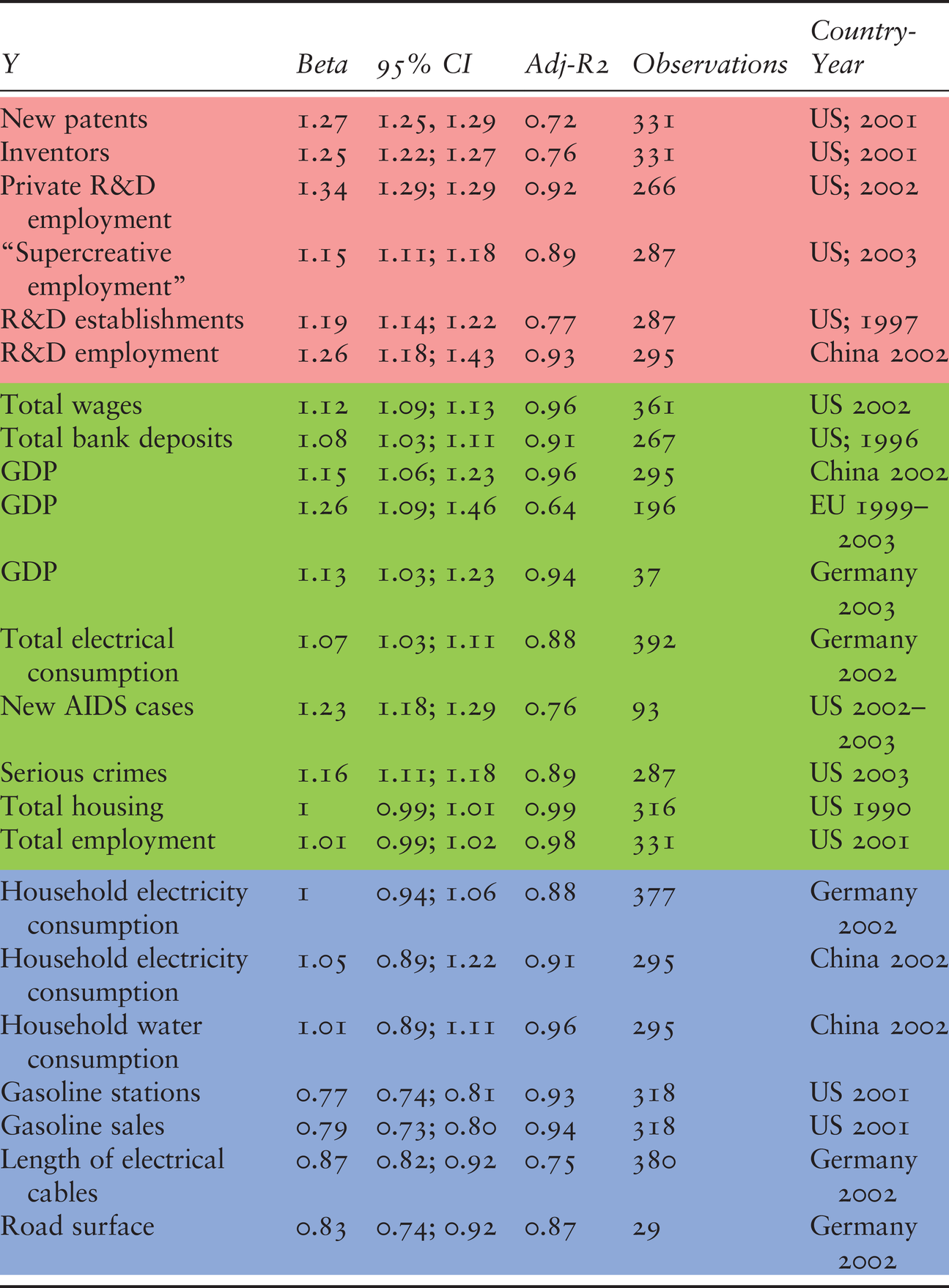

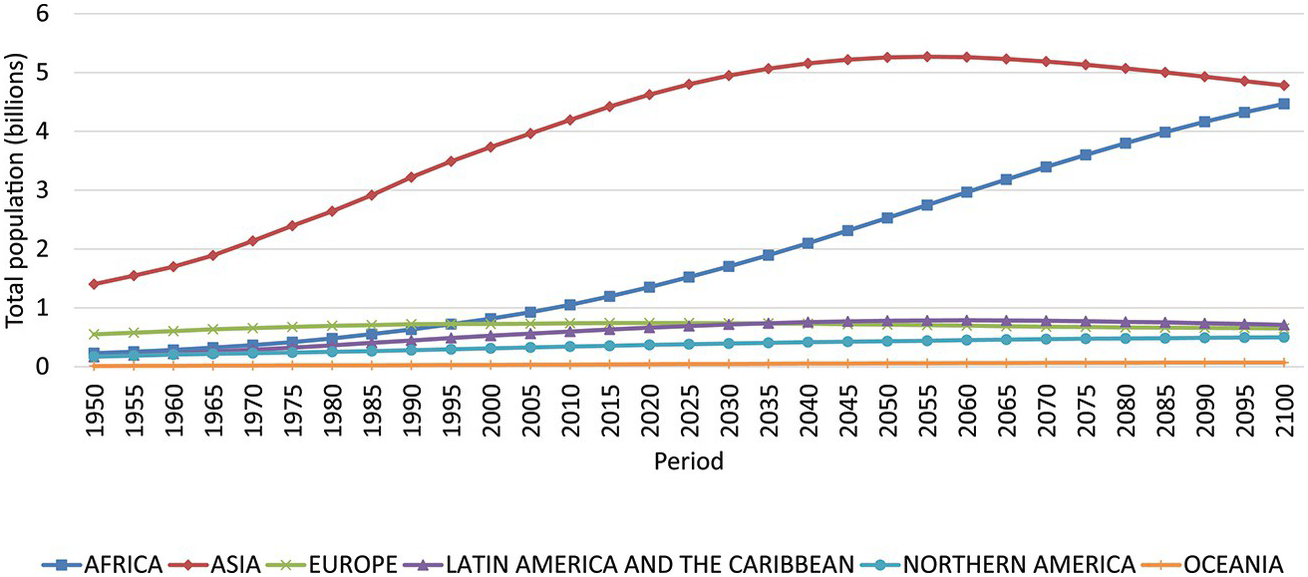

Figure 16.1 shows three different projections of the demographic tendencies currently observable worldwide. Notwithstanding the fact that it is difficult to predict the demographic evolution over a whole century, it is one of the most solid forecasts of all, even though in the past effective population growth has often tended to attain the higher ranges of the predictions. The predictions take increasing life expectancy in proportions related to wealth and healthcare into account, and also the fact that as populations grow wealthier they reduce their birthrates. But they do not take the potential nonlinearities into account that might be created by quantum jumps in healthcare, such as the healing of cancers, the potential of stem-cell therapy, etc.

Figure 16.1 Projected global population growth 2000–2100 as projected by the three Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP) scenarios and the probabilistic ranges given by the UN.

The wide divergence between the scenarios in Figure 16.1 clearly illustrates the difficulties of projecting so far into the future.

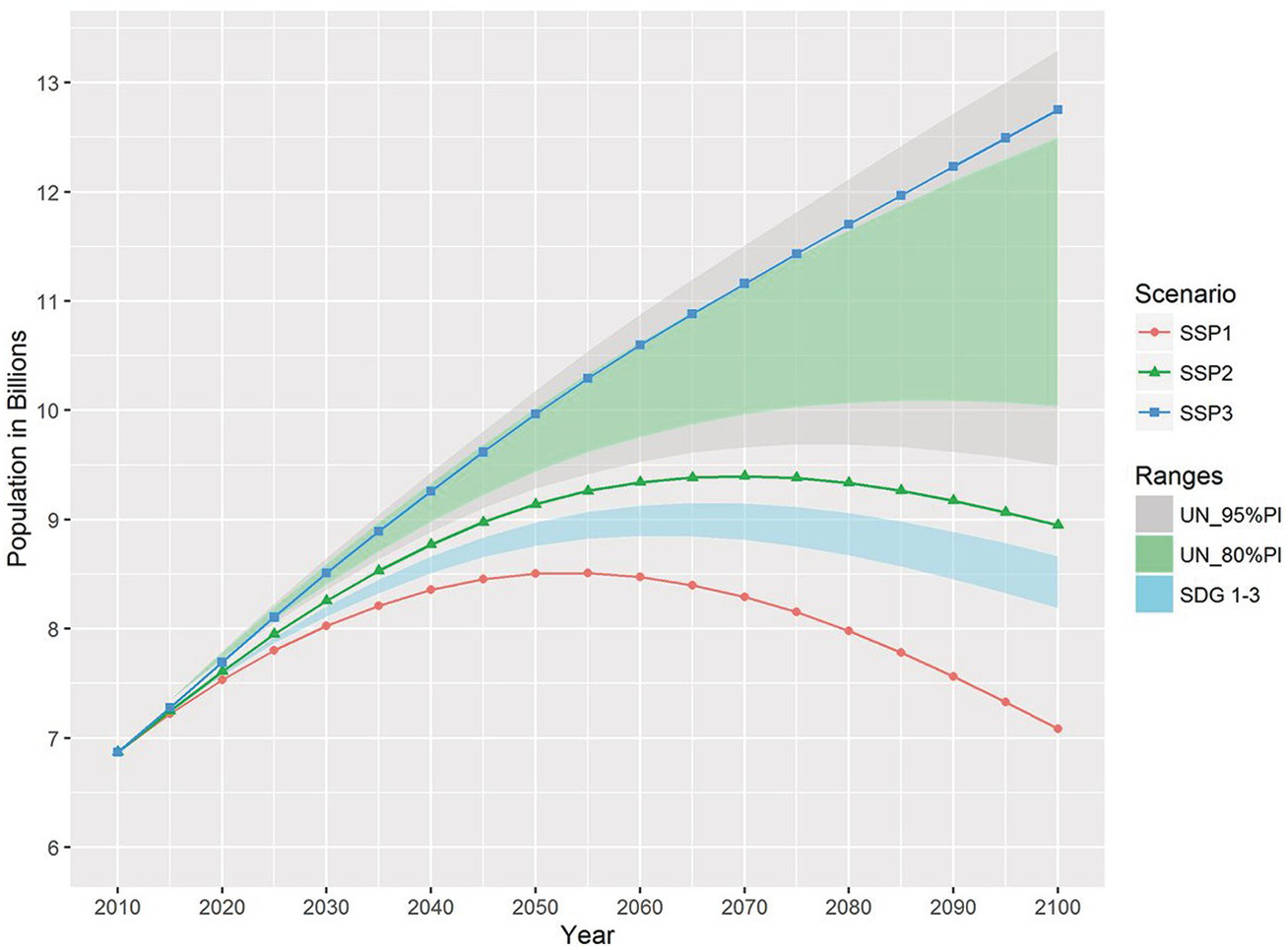

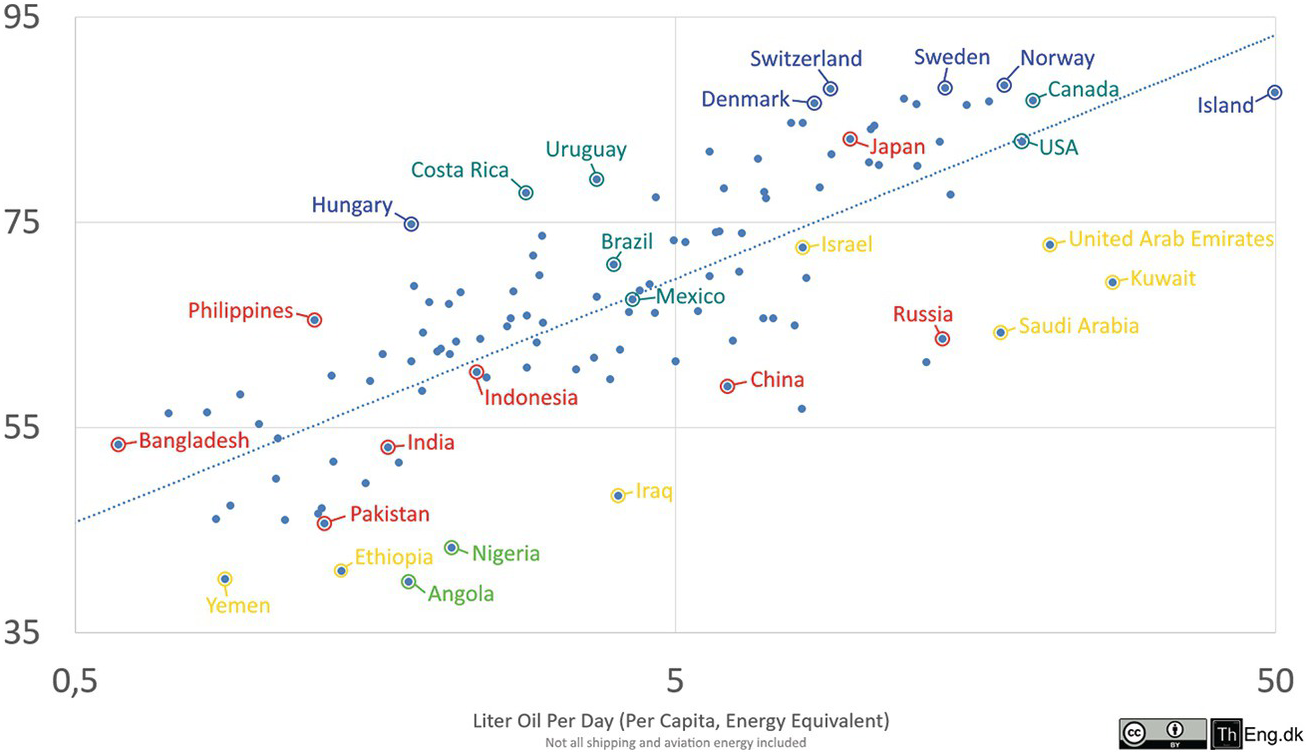

These population figures are only one part of the picture. Major differences in the distribution of health are the other. As shown in Figure 16.2, health, as represented by life expectancy at birth, is very unevenly distributed across the globe, and its distribution appears to be similar to that of wealth.

Figure 16.2 Life expectancy at birth (years) by region: estimates 1975–2015 and projections 2015–2050.

This has direct implications for overall global population growth, which in the coming decades is expected to be principally occurring in Africa (Figure 16.3).

Figure 16.3 Population growth by macro-region. Most population growth is predicted for Africa.

It is generally expected that with growing wealth in the developing world, the crude birth rate will go down as life expectancy increases. In 2018 the population of the world is growing at an average annual rate of 1.1 percent. This rate has been declining since 1965–1970, when it peaked at around 2.1 percent. The fact that world population growth is on the decline can be explained by the Demographic Transition Theory (Notestein Reference Notestein1954). Eventually, according to this theory, all societies evolve from a pretransition situation (stage 1), where fertility and mortality are unchecked and high, thus producing low population growth, to a stationary population (stage 4), when a society reaches low levels of fertility and mortality. This pattern is quite well established and exceptions have so far been of a temporary nature.

The crucial question is, however, whether growth in wealth and decrease in birth rate will manifest themselves at more or less the same rates or not. Another question is how these processes will play out in different parts of the world. No one knows, but it is clear that 200 years of western industrial economy have created important demographic discrepancies that may impact on global sustainability.

Aging

Behind these global figures lurks a potentially major challenge: aging. Generally, it is assumed that growing economies require growing working-age populations. Currently, in a number of developed countries, aging and a low birth rate combine to cause decreasing numbers of inhabitants of working age: Japan, China, Germany. Others still have an expanding population due, for example, to important immigration (the USA, Canada, Australia), but in a general political climate in which immigration is increasingly subject to xenophobia, those fluxes may well decrease. This will have an impact on the size of these economies, not so much from the supply side (where people will probably be replaced by automation), but on the demand side.

The opposite is the case for Southeast Asia and Africa, where birthrates are still higher and the working-age population will be growing for some time. There, the economies will continue to grow, and one of the interesting questions that raises is whether this will also entail a shift in global power balance toward the currently developing countries. That will in part depend on whether, and how far, these countries will be able to develop their technologies and economies, but also their institutions and legal systems. China has shown, over the past few decades, how this can be done.

Global Migration

Another fundamental characteristic of the current world, but with ancient origins, is large-scale migration. It is exceedingly difficult to obtain good quantitative data on the numbers of people involved, and a purely narrative description will have to suffice.

Current research indicates that on a global scale migration has not recently increased substantively, but at local and regional scales it has shifted demographies. According to the UN, during 2005–2050 the net number of international migrants to more developed regions is projected to be 98 million (UNDESA 2017). Such regional migration is likely to further accelerate in the foreseeable future owing to, for instance, climate change, sea level rise, and food and water availability. But there may also be increasing pressure toward migration for societal reasons, such as warfare, failing states, populism, ethnic cleansing, or criminal violence. The rapid spread of information through word of mouth, television and the Internet is contributing to migration in important ways. It triggers widespread “push” reactions in the developing world, driving people living in dangerous or economically difficult circumstances to migrate to the USA, Canada, the EU, and other (mainly developed) countries.

Migration is thus likely to further accelerate in the foreseeable future. The counterpart may be a defensive reaction in developed countries, fed by local populism and identity issues, creating more barriers to migration and globalization such as is currently occurring in Southern Europe and the USA. But then, demographic and economic declines in developed countries may in the end overcome such sentiments. Major environmental disasters and ethnic cleansing will probably further complicate the situation. All in all, we can therefore expect major cultural, social, and economic challenges related to migration in the developed world as well as in the developing world, wherever state control is not willing or able to deal with, or prevent, mass migration.

Food (In-)Security

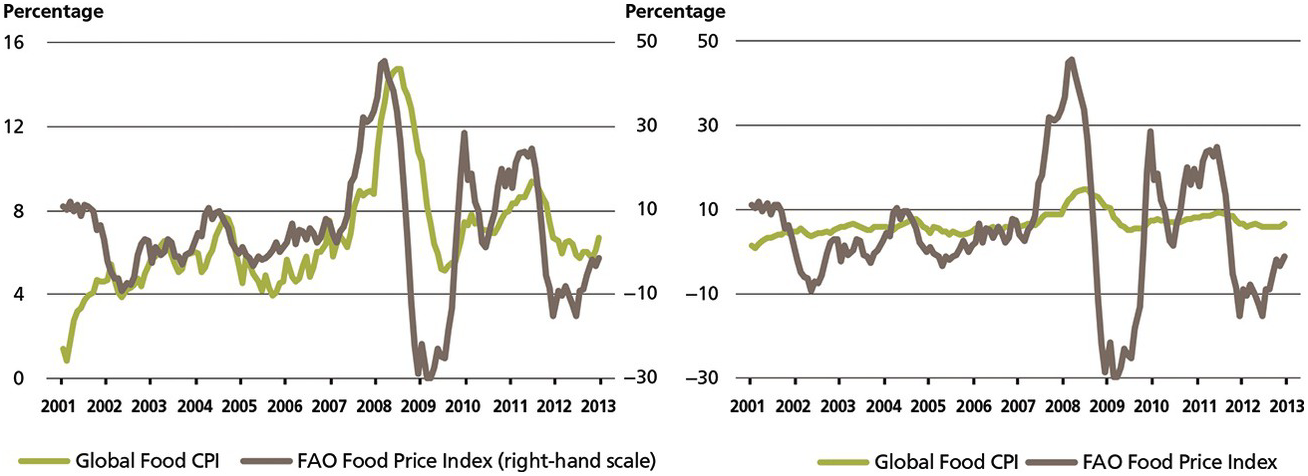

The importance of these demographic trends becomes clear if one compares them with the evolution of our resource footprint as a global population. One consequence of major innovations in healthcare, and the spread of technologies to make human beings healthier across the world, has been that we are, as Tim Flannery (Reference Flannery2002, n.p.) put it, “eating our future.” We are facing a potential crisis in the provision of water and food for the world population that could very easily trigger major conflicts. Recent increases in food prices due to speculation are early warning signs that food security may, in the not-so-distant future, become a major challenge worldwide (Figure 16.4). No surprise, then, that the topic has in the past five years emerged as a major concern, both scientifically and politically.

Figure 16.4 Food prices remained relatively stable from the 1980s to 2005 thanks to the green revolution, but have recently spiked partly as a result of speculation and ethanol production

Individual countries are hedging against the possibility that food and water insecurity will threaten their populations, for example by buying large tracts of land in Africa. But as the population of Africa is growing faster than the population of any other area, one has to wonder whether this strategy will in the end be sustainable.

Fossil Energy

Energy has been a constraint on human societal evolution for most of the existence of the species, but that constraint was lifted with the harnessing of fossil energy in around 1800.

Since then, energy use has increased very rapidly, as was seen in Figure 15.1. Basically, the societal dynamics that are driving our societies have increased average global energy consumption from approximately 20 gigajoules (GJ) per capita per year at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution to approximately 80 GJ per capita per year now. Clearly this is very unevenly divided between the developed and the developing world. In the USA, in 2013, average per capita consumption was in the order of 290 GJ equivalent per year, while in India it was only about 25 GJ. Most of that difference is absorbed in building, maintaining, and running our material and institutional infrastructure. A growing need for energy is fundamental to the way in which the world is currently moving, and energy consumption, for political and economic as well as societal reasons, is not likely to decrease in the foreseeable future.

Yet the total quantity of exploitable fossil energy on earth is limited, and this has, since the 1970s, led to the conclusion that at some point in the future oil as a cheap resource will be exhausted. That point may recently have been pushed back owing to exploitation of new oil gas deposits (but see Day & Hall Reference Day and Hall2016), the discovery of large volumes of natural gas, and the expansion of renewable energy use, but traditional gas and oil exploration and exploitation is becoming more and more expensive because the superficial sources in accessible areas are being depleted and replaced by fossil fuel from very deep sources (presal in Brazil) or extreme climates (Arctic). Though there is coal for many more years, the fact that burning it is highly unadvisable from a greenhouse gas and global warming perspective is forcing us globally to reduce its use.

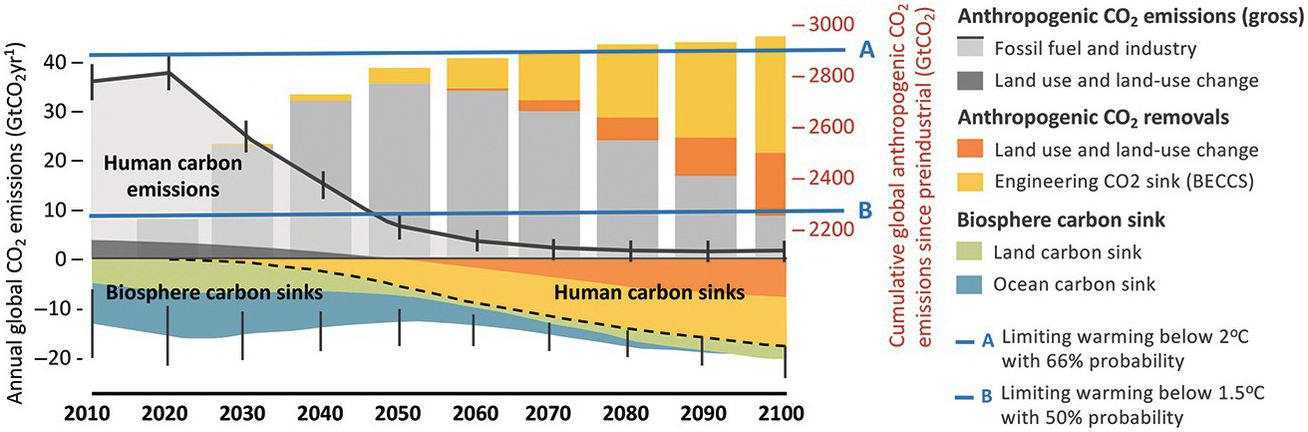

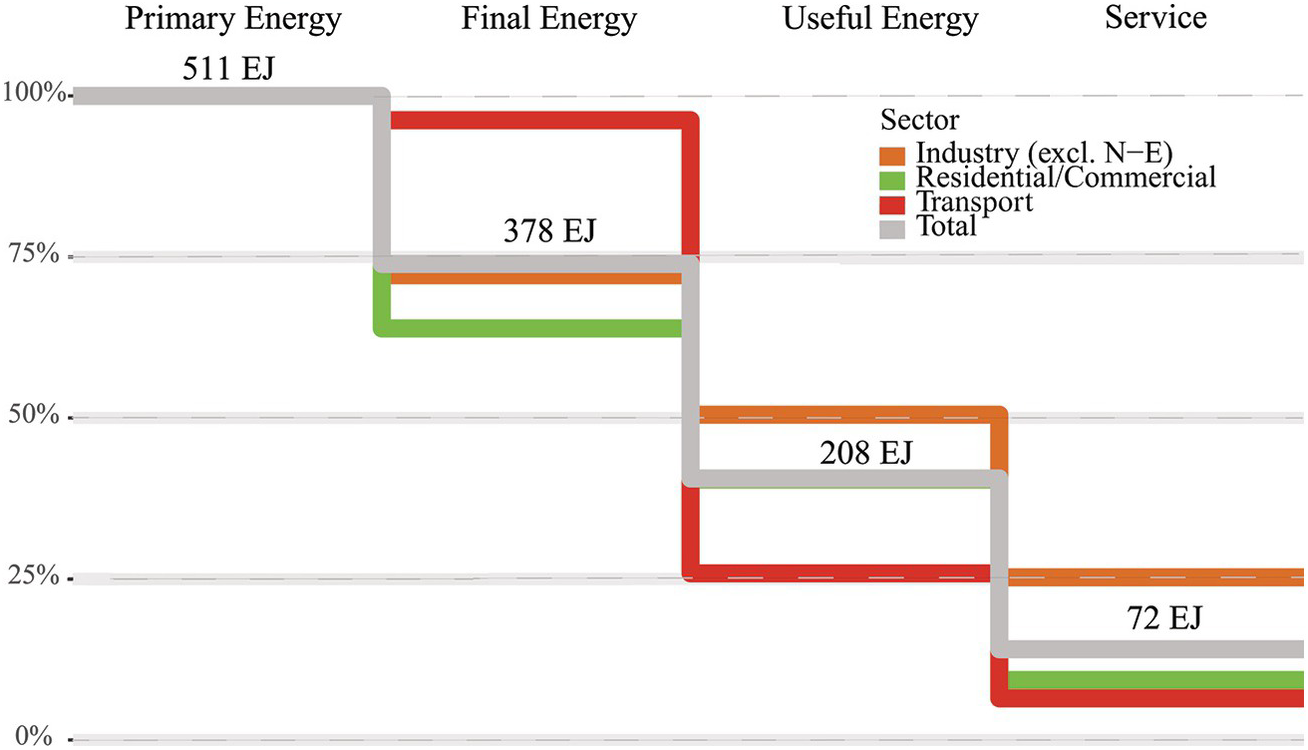

As energy has been an early target in the world’s efforts to reduce global CO2 emissions, major efforts have been deployed to reduce both the use of fossil fuels and of their CO2 emissions. Numerous approaches have been discussed and some of them undertaken. Technologies have been invented and improved, such as the application of digital information processing in grids. In particular, substantive measures have been taken to reduce CO2 emissions (by shifting from coal to oil, then gas, then renewables) and to increase the efficiency of energy use (in electricity generation; insulation of buildings; transport, etc.). But as Figure 16.5 shows, this is still woefully insufficient, partly because only a fraction of total energy ends up being useful (Figure 16.6 in the box below).

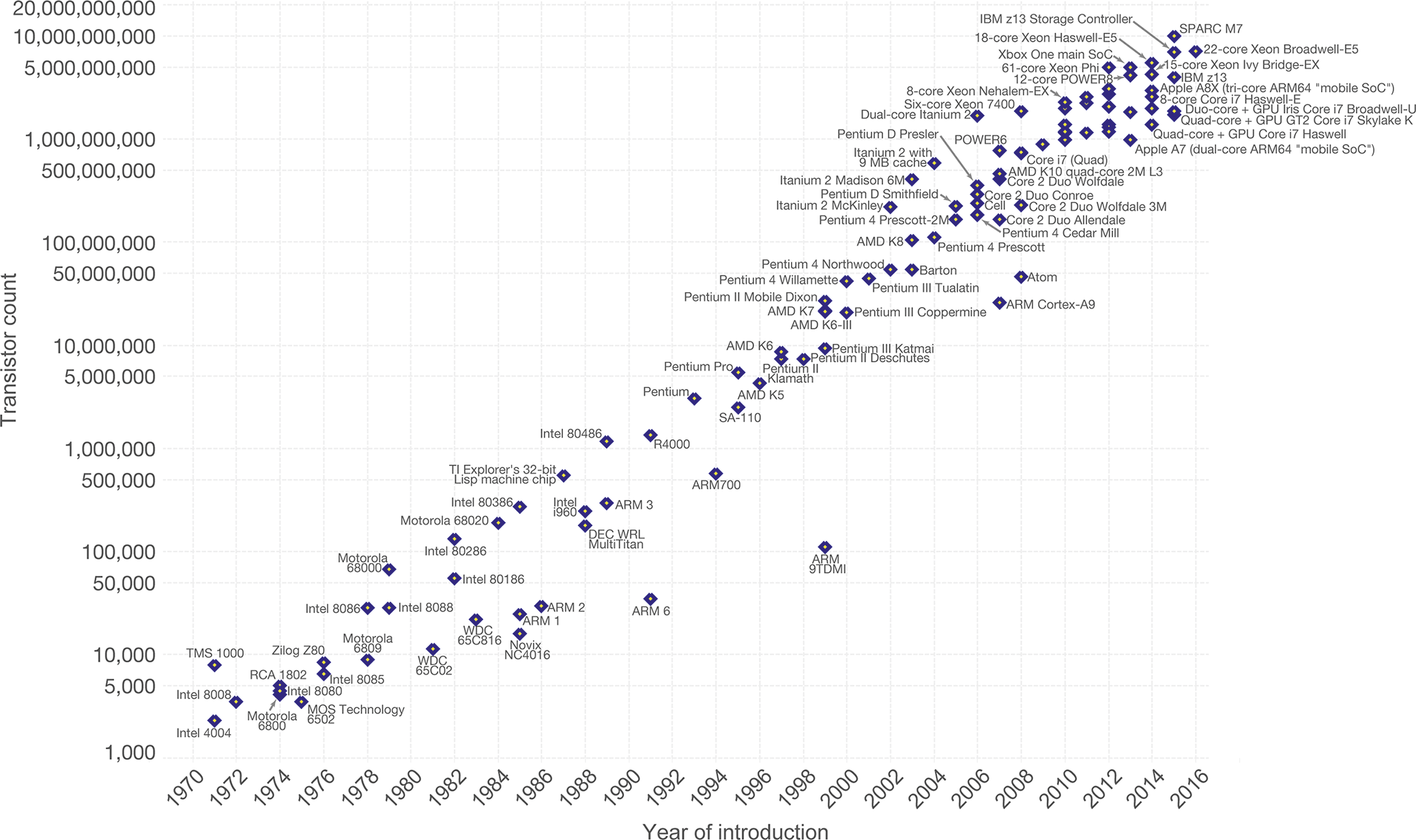

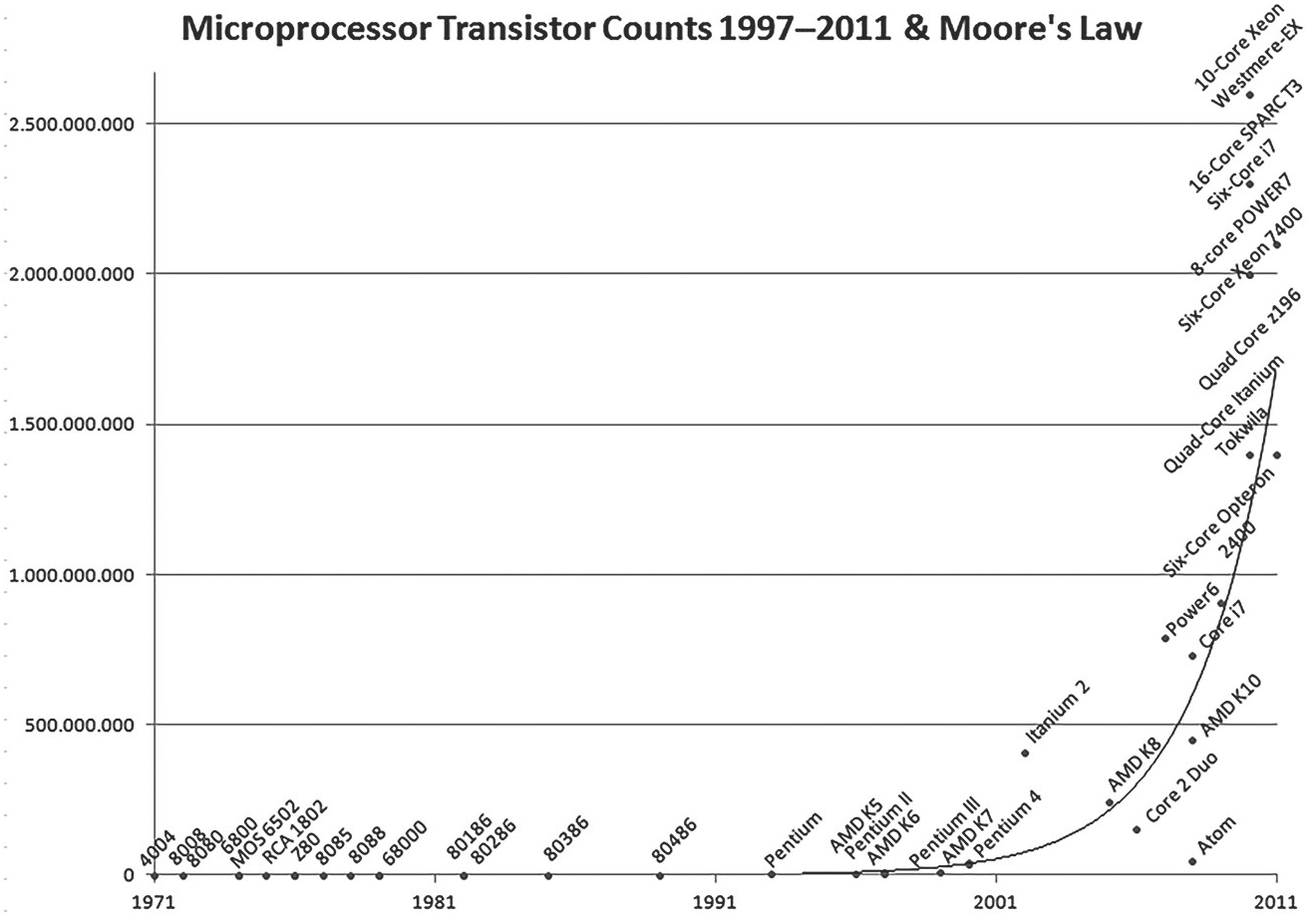

Figure 16.5 Cumulative and annual emissions and sinks of CO2 are shown for stabilizing global climate at below 2ºC and 1.5ºC. Most of the carbon emissions shown in gray are energy-related. Together with land-use emissions they need to decline toward zero by midcentury. The figure is called Carbon Law as a metaphor to Moore’s Law of semiconductors, where a number of transistors on a chip doubled every two and a half years. Carbon Law indicates that global emissions need to be halved every decade. In addition, human carbon sinks need to increase to almost half the magnitude of current positive emissions: This is a tall order. Carbon capture from biomass (bio-energy use with carbon capture and storage – BECCS) and land-use change are here the key. Third, biosphere carbon sinks need to be maintained as atmospheric concentrations decline. The vertical gray bars show cumulative emissions since the beginning of the industrial revolution of some 2,000 billion tons CO2. This budget, or carbon endowment of humanity, will be exhausted shortly as the remaining emissions for achieving stabilization at below 1.5ºC are essentially nil while we still emit some 40 billion tons CO2 per year. Net-negative emissions are needed to stay within this budget. The remaining budget for stabilizing at 2ºC is a bit more generous so that the demand on net-negative emissions can be significantly reduced. The Carbon Law can be seen as a roadmap toward making the Paris Agreement and the SDGs a reality. Pathways shown in this report such as the SSP1 variant focused at the 1.5ºC target or the alternative scenarios portray similar dynamics, whereas the latter is unique among stabilization pathways as it does not need net negative emissions because of vigorous changes in end-use technologies and behaviors.

Figure 16.6 Energy conversion cascades in the global energy system. Lines show percentage of extracted primary energy delivered as final energy, useful energy, and services respectively for three end-use sectors (industry, residential and commercial buildings, transport) and totals for the whole energy system in 2020. Energy flows exclude non-energy feedstock uses of energy (labeled as N-E). Total energy flows (EJ) are shown at each stage of the energy conversion cascade. Service efficiencies are first-order (conservative) estimates based on Nakićenović et al. (1990) and Nakićenović et al. (1993).

The world has currently achieved a total global efficiency improvement of about 2 percent per year. But as concluded by the “The World in 2050” team (TWI 2050, 62), all these efforts are quite insufficient to substantively reduce greenhouse gas emissions. As stated by the International Energy Agency (2017): “While carbon emissions have flattened in recent years, the report finds that global energy-related CO2 emissions increase slightly by 2040, but at a slower pace than in last year’s projections. Still, this is far from enough.”

This worrying situation is exacerbated by the fact that the decrease in return on investment in traditional energy capture risks leaving a substantial proportion of the theoretically available (identified) resources in the ground, potentially creating a major financial liability for the institutions that have lent money against those irrecoverable assets (the so-called stranded assets problem). This poses a threat to our current global financial system, as do some of the derived geopolitical risks involved in oil price fluctuations. If countries cannot make enough money on fossil fuels, their political structure becomes unstable (in Venezuela from 2016 to 2019, for example). Moreover, if we continue to reduce global poverty, one can reasonably expect energy needs to continue to grow. For example, in Saudi Arabia the national increase in energy use is such that the country may cease being a net oil exporter by 2032 (Leggett Reference Leggett2014). If we include in the calculations the energy needed to increase the living standard of the whole global population to a level that guarantees a comfortable life (without going into the excesses of the current West), we will clearly exceed all acceptable levels of fossil energy use from an atmospheric pollution perspective because this would almost certainly involve substantive use of coal, which is currently (and will so remain unless major technical innovations change the situation) the worst polluter among the fossil energies. Only renewable energy can avoid this energy squeeze, but though its installation is growing exponentially (it now produces about 20 percent of global energy), that is still not fast enough to compensate for emissions growth from fossil fuel (not to mention land clearance, saturation of the ocean’s absorption capacity, tundra melt leading to methane release, and so forth).

Finance

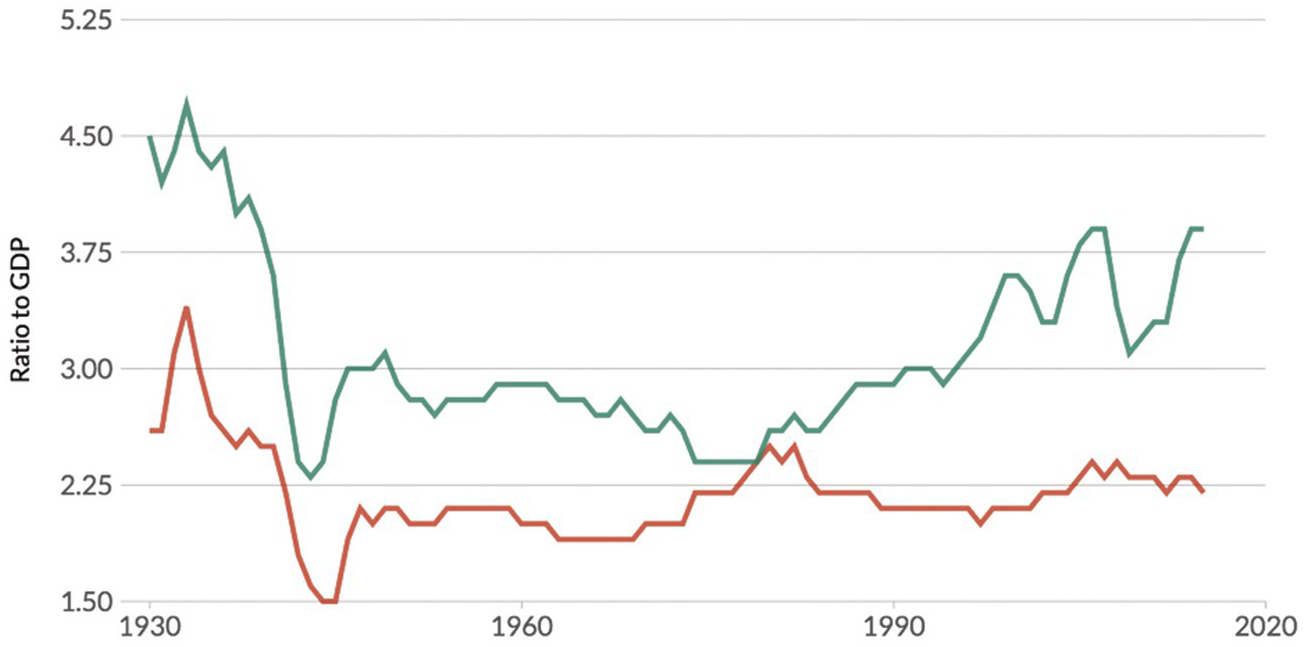

We can clearly see that in recent years a very important, and growing, proportion of total financial capital is no longer engaged in the production of goods or services, but entirely devoted to what amounts to speculation. Figure 16.7 shows how the proportion of available capital that is subject to capital gains tax and is therefore not productively invested has been increasing in the USA since the late 1940s and has recently in some years constituted close to 40 percent of total financial capital. As such speculative capital moves around with worrying (and increasing) speed, for example between developed and developing countries, but also between sectors, individual institutions, and forms of investment, the basis of our global financial systems is substantially, and increasingly, unstable.

Figure 16.7 Fraction of total gross domestic product (in the USA) invested in production (red line, without capital gains tax) and speculation (green line, with capital gains tax). The global recession of 2008 has depressed both trends, but the relationship is still the same.

The mobility of speculative capital associated with the fact that it is controlled by fewer and fewer people (see below on the “wealth gap”) and institutions (some of which are now considered “too big to fail”) has had the destabilizing effect of contributing to the rapid succession of financial crises that we have seen in the last sixty years (The Economist in 2014 ran the headline “The History of Finance in Five Crises”). There are many different aspects to this trend, but there are several that are so dangerous that we need to include them in our thinking about the future.

Trade, Protectionism, and Investment Flows

Several developed economies are currently moving toward protectionism, under the pretexts of protecting jobs, correcting bilateral trade imbalances, or even national security. This restricts economic growth in the long run, since it inhibits trade in intermediate goods and the creation of value chain niches. It also threatens the existing supply chains in our greatly interwoven global economy. Moreover, the uncertainty produced by the threat of protectionism slows down investment flows in global capital markets, as it generates uncertainty regarding future economic growth (Erokhin Reference Erokhin2017). This is aggravated by trends in international aid, migration, climate change, and geopolitics. Protectionism threatens food sustainability by drastically shifting value chains and forcing replacement of staples and other foods with less sustainable varieties. Trade has a major role in stabilizing food prices, as well as shifting production from areas of high environmental risk to less risky areas (IFPRI 2018). The effects of protectionism in developed countries will be felt most acutely in the least-developed countries (LDCs) (UNDESA et al. 2018). Many LDCs are dependent on external demand for commodity exports, as well as foreign aid for budget support (Timmer et al. Reference Timmer, Dailami, Irving, Hauswald and Masson2011). In a closed world economy, many LDCs will continue to lag behind more developed economies, and this will have important ramifications in other sectors. LDCs will not achieve the economic growth required for sustainable development without a significant increase in investment. However, many of these countries are unable to attract the levels of investment they require owing to institutional deficiencies, an overdependence on commodities subject to fluctuation in prices, and a dearth of basic infrastructure to support fledgling industries.

Debt

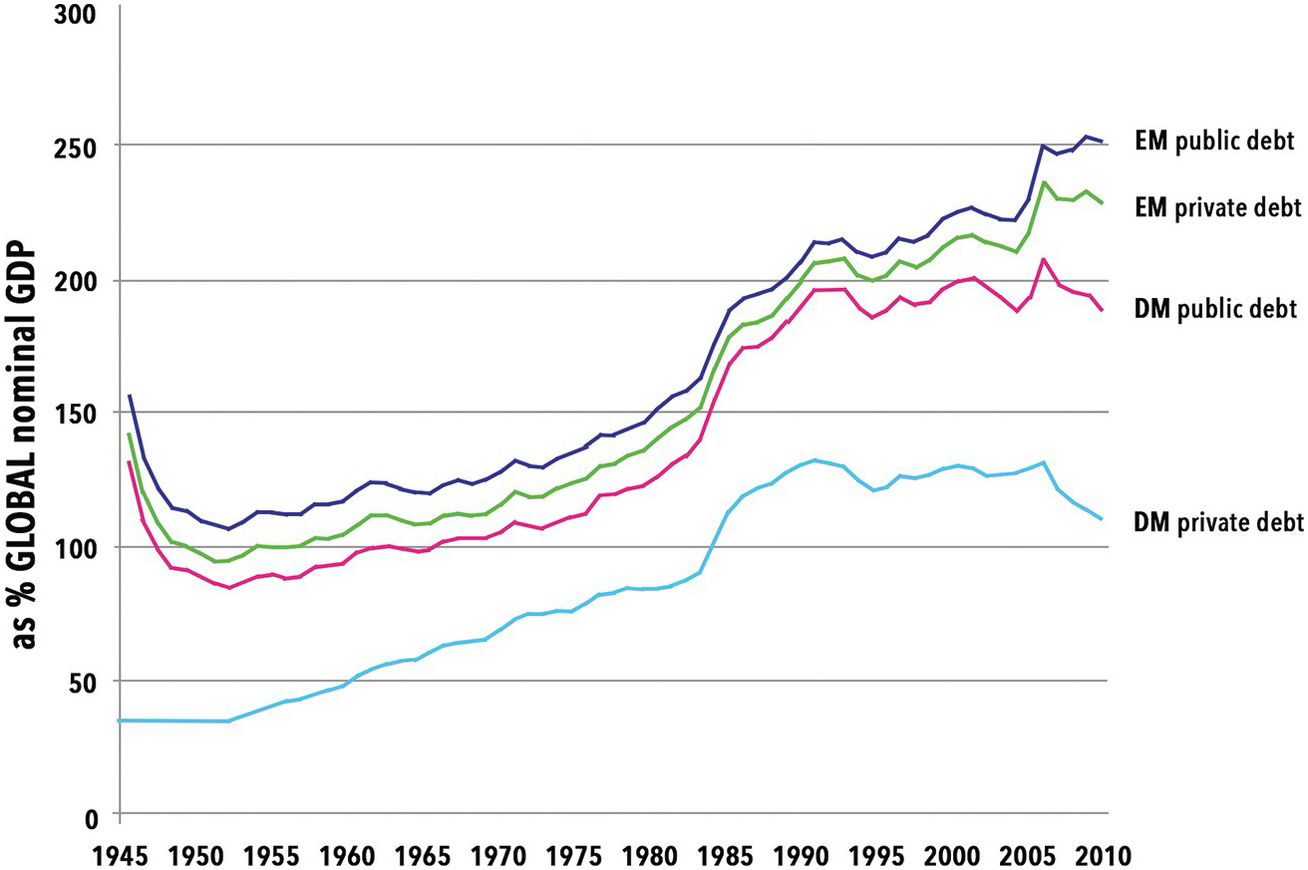

The rapid increase in global indebtedness (see Figure 16.8) is directly threatening overall financial and economic stability. Nominal global debt is currently around 250 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). This includes both government and private debt, and the percentage has been rising for most of the last fifty years, after a major deleveraging phase immediately following World War II. This debt is unevenly distributed among countries, and also between public and private debt, with the latter generally growing faster than the former. As long as the world is – and most countries are – on a growth trajectory this is not necessarily a financial problem, as people have enough confidence that much of this debt will in the end be reimbursed, and because inflation reduces the real debt load.

Figure 16.8 Private debt in developed and developing countries exceeds public debt.

We have to remember, though, that this whole system is fiduciary, and that if trust in it is for some reason or other undermined it could collapse very easily, leading to major social unrest. As we saw in the 2007–2008 Great Recession, there are many hair triggers that may cause such a collapse. And because each crisis is countered by central banks with an increase in their debt levels, the underlying instability increases with each such event (Figure 16.9).

Figure 16.9 Public debt in the USA, other developed countries, and emerging markets. After the 2007 debt crisis, public debt increased rapidly, to level off (except in the USA) after 2010.

In recent years, we have also seen how several individual nations have seen trust in their financial systems collapse owing to mismanagement or actual cheating (Argentina, Greece, Ireland, Turkey).

That is not affecting world financial stability as long as there are other economies that can serve as lenders of last resort because they are bigger and in better shape. However, with the overall increase in debt level among both large and small countries this mechanism may itself be at risk.

Another aspect of the high debt level is the fact that an ever-larger percentage of GDP is devoted, by governments and individuals, to interest payments, which reduces the proportion of GDP that is available for spending. There is thus an incentive to promote a feedback spiral, increasing the debt to be able to both spend as necessary and pay the interest owed.

Ultimately, this may hit the total amount of funds available for investment and lead to reductions, notably, in infrastructure maintenance (as is currently occurring in a number of developed countries). In certain cases, this problem may even limit the potential for further investment in the expansion of productive capacity.

It is easy to see that the information revolution, which has reduced transaction times to milliseconds, and which has linked all financial markets in one large web, contributes further to the potential instability of the global system as a whole.

Aging Populations, Productivity, Savings, Debt, and Pension Systems

I have already mentioned that a major demographic trend is the aging of populations. It has tremendous economic implications that represent a challenge for the sustainability of welfare systems in developed and developing economies. This includes pension and healthcare systems, in addition to a possible decrease in savings and investments (Bosworth et al. Reference Bosworth, Bryant and Burtless2004). In developed countries, an increased burden will be placed on public transfer systems, owing to the concurrent trends of a growing proportion of pensioners and a diminished tax base. However, the majority of the increase in the population above the age of sixty will occur in the Global South (UNDESA 2017), where the elderly are less likely to have retirement savings plans or to be supported by public welfare systems, and instead depend on assets and labor income. Without the means to support themselves in retirement, many of these people are susceptible to poverty. An aging world population also means that the share of non-communicable diseases in the global disease burden will grow, increasing pressure on countries’ health expenditure, adding to the fiscal burden of government budgets.

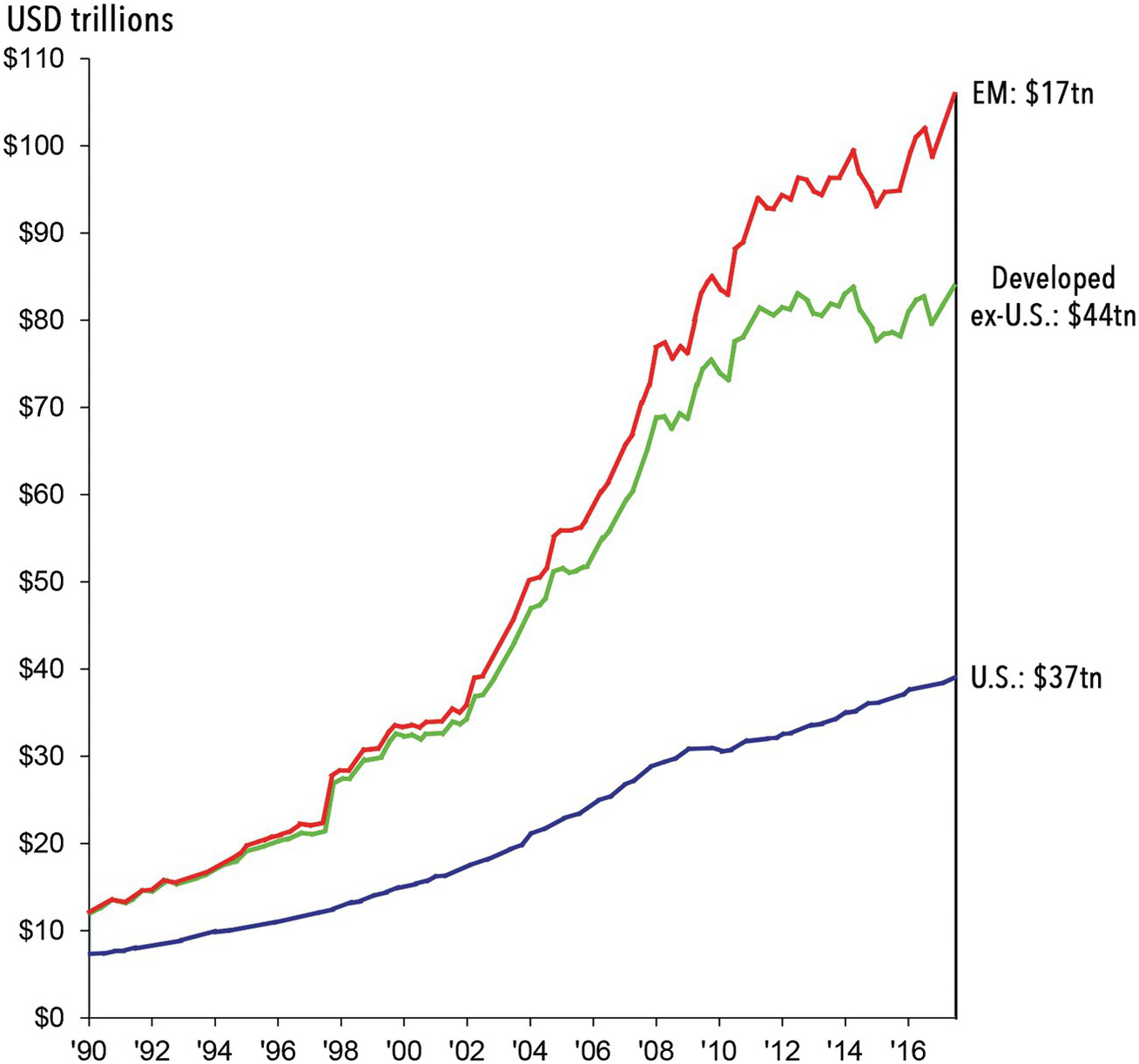

Low productivity growth in developed economies in recent years has been explained by aging workforces, a slowdown in total factor productivity in the information and communications technology (ICT) sector, declining contributions of trade to economic growth, and stagnation in levels of educational attainment (Adler et al. Reference Adler, Duval, Furceri, Sinem, Koloskova and Poplawski-Ribeiro2017). Between countries, global inequality has decreased in the last decade thanks to the contribution of China and India in their economic development process. As these and other emerging markets continue to grow, the economic hegemony of the United States and its western allies will gradually be replaced by a multipolar world economy, in which India, China, Indonesia, and Brazil become increasingly important economic hubs for financial services, manufacturing, and innovation (Timmer et al. Reference Timmer, Dailami, Irving, Hauswald and Masson2011).

However, this trend does not mean that economic growth will be evenly distributed. Many LDCs are at risk of continued vulnerability to economic shocks for the reasons previously mentioned. Their economic vulnerability is compounded by the fact that many of the LDCs are facing disproportionately high threats from climate change, have rapidly growing populations, and also have weak governments and vulnerable security situations. These trends are inhibiting the ability of LDCs to bridge the gap between themselves and the emerging and developed economies. Without appropriate economic growth and investment, their populations may continue to grow at unsustainable rates, they will not be able to provide adequate education to their youth, and the coverage of health services will remain incomplete and fail to tackle preventable causes of morbidity and mortality (UNDESA 2018).

Innovation and Societal Coherence

The societal implications of the innovation challenge, though major, are much less clearly perceived, and have probably differed across cultures and societies. In the case of the west, I mentioned in Chapter 12 that Girard (Reference Girard1990) argues cogently that between the seventeenth and the twentieth century, society’s perspective has shifted from one directed toward the past and therefore encouraging stability (“the future is more of the present”) to one that favors change and innovation. That is a fundamental change in our (western) values, and should not blind us to the fact that for many societies change may not have been a fundamental value.

Nevertheless, any society will ultimately lose coherence unless its members continue to see an advantage in being a member of the society (van der Leeuw Reference van der Leeuw, Costanza, Graumlich and Steffen2007). This means that the society must maintain a sense of comfort among its members. I would argue that over long-term time, even if ever so infrequently, some degree of innovation is necessary, because when societies reach tipping points in their dynamics, innovation is called upon.

Whether in the material and technical realm or in the socioeconomic one, every innovation requires energy for implementation, whether it is to change the structure of institutions, to change collective behavior, or to create or modify infrastructure. One of the consequences of the harnessing of fossil energy after 1750 has been that, for a considerable amount of time, it was relatively cheap in energy terms to innovate. We have therefore, over the last 250 years, seen an ever-accelerating spate of innovation in the material and technological realms, which has globally brought with it an important population growth (especially in the last seventy years), an emphasis on “progress,” an increase in life expectancy in many places, and a huge increase in trade leading to globalization. It is difficult to point to specific single causes for this very complex coevolution, but one argument that has a certain ring to it is that these phenomena are part of the ideology that capitalism (initially industrial, more recently financial) has developed to ensure profits through growth. I return to this topic in Chapter 18.

Whether this process can continue at a sufficient rate to keep our current societal institutions intact will of course in part depend on whether we continue to meet our society’s growing innovation needs. But there are some early signs that this is not as self-evident as some think.

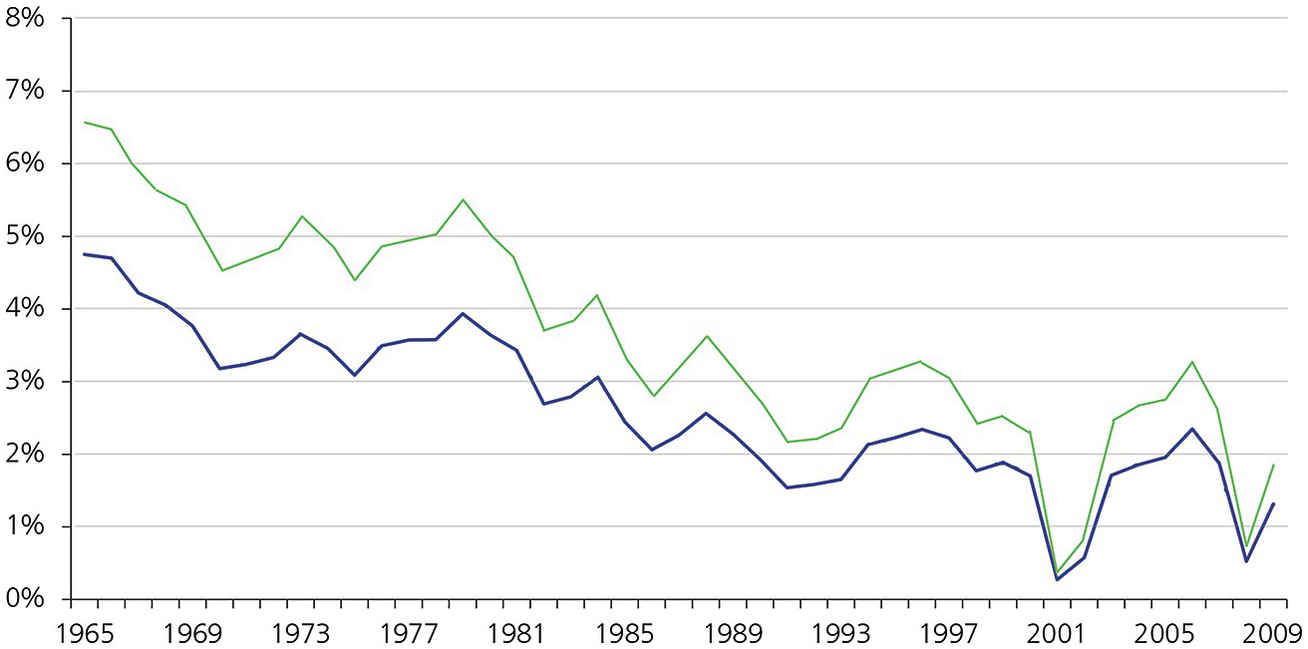

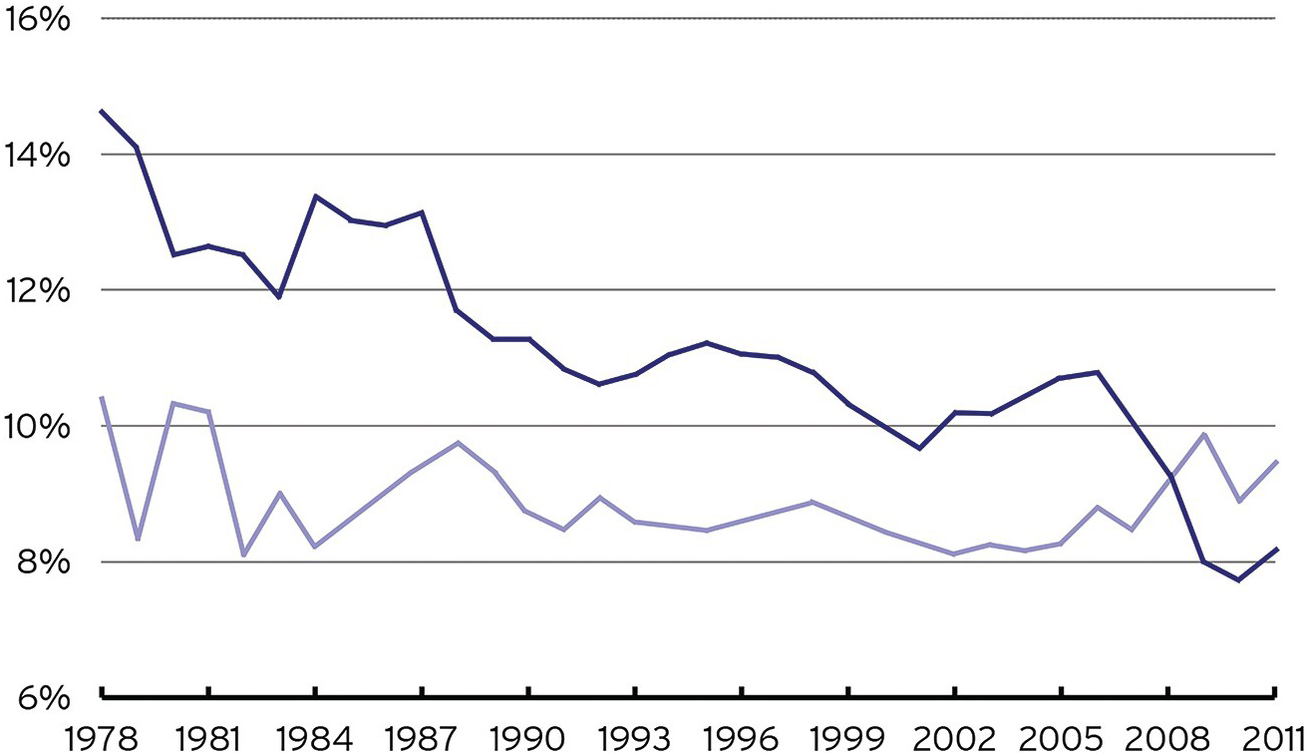

One observes in the USA an overall decrease in return on invested capital (Figure 16.10) as well as a decline in entrepreneurship (Figure 16.11), which might be linked to an overall decline in the frequency of major innovations.

Figure 16.10 Evolution in return on invested capital in the USA, 1965–2011. The blue line represents the evolution of return on assets; the green line that of return on investment.

Figure 16.11 Annual new firm creations (dark blue line) and existing firm deaths (light blue line).

If we offset the number of patents per innovator against the growth in size of the teams involved in an innovation, we see that innovation involves more and more domains, and becomes more and more difficult and costly. Research on the wealth created by innovations registered at the US Patent and Trademark Office seems to point to the fact that, in terms of the return on investment on such innovations, their impact on the economy is slowing down (Strumsky & Lobo Reference Strumsky and Lobo2015). This may be because the explosion of patents over the last fifty years has made it more and more difficult to come up with something that is so new that it sets an innovation cascade in motion within or outside our current technologies. Another contributing factor could be that the shift toward short-termism in many industries makes it more difficult to develop innovations with long loss leaders. But there may be a more fundamental reason for this: has our value space (the total set of dimensions to which we accord economic value) reached a limit? I will return to this point in Chapter 17.

Wealth Discrepancy

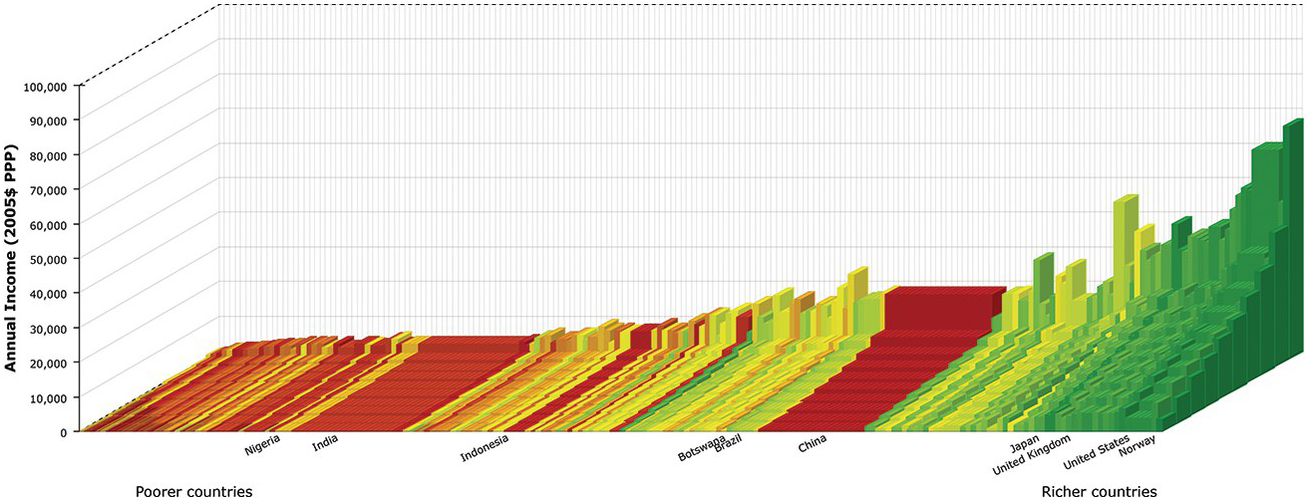

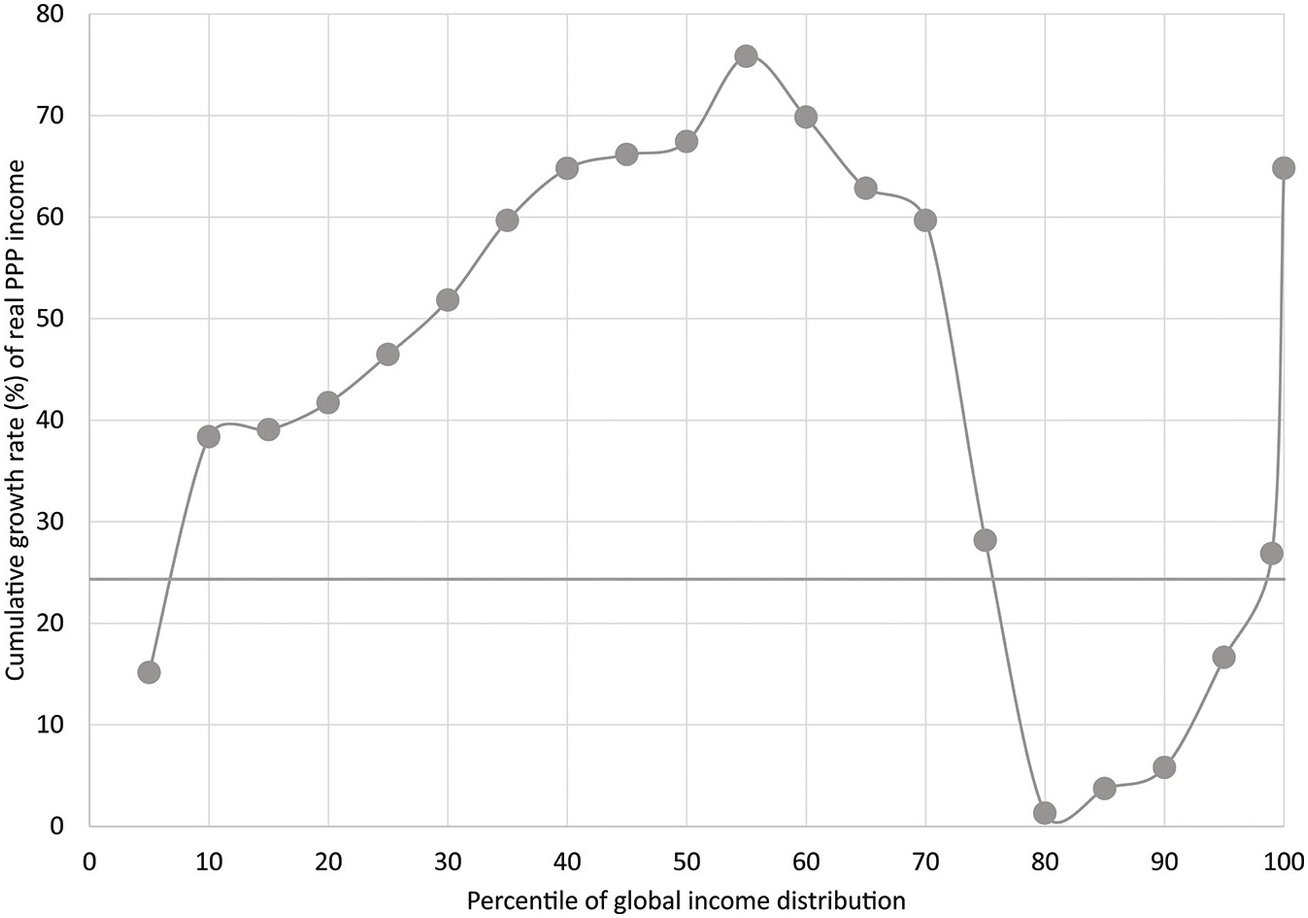

The global economy has created excessive material wealth differentials by concentrating most such material wealth in the hands of a relatively small, if growing, proportion of the world’s population, almost entirely in the developed countries (Figure 16.12). This causes a steepening of the wealth disparities within and between countries in another very long-term deep trend, as analyzed recently by Scheidel (Reference Scheidel2017), which is very difficult to invert, as his many case studies show.

Figure 16.12 Worldwide differences in wealth distribution

Recently, we observe two opposing trends in this dynamic: a leveling off of wealth disparities between developed and developing nations and an increase of wealth disparities within many countries. This is the statistical effect of the rich becoming richer in the developing countries (especially the BRICS countries), while within these countries – as well as in the developed world – the contrast between rich and poor becomes starker.

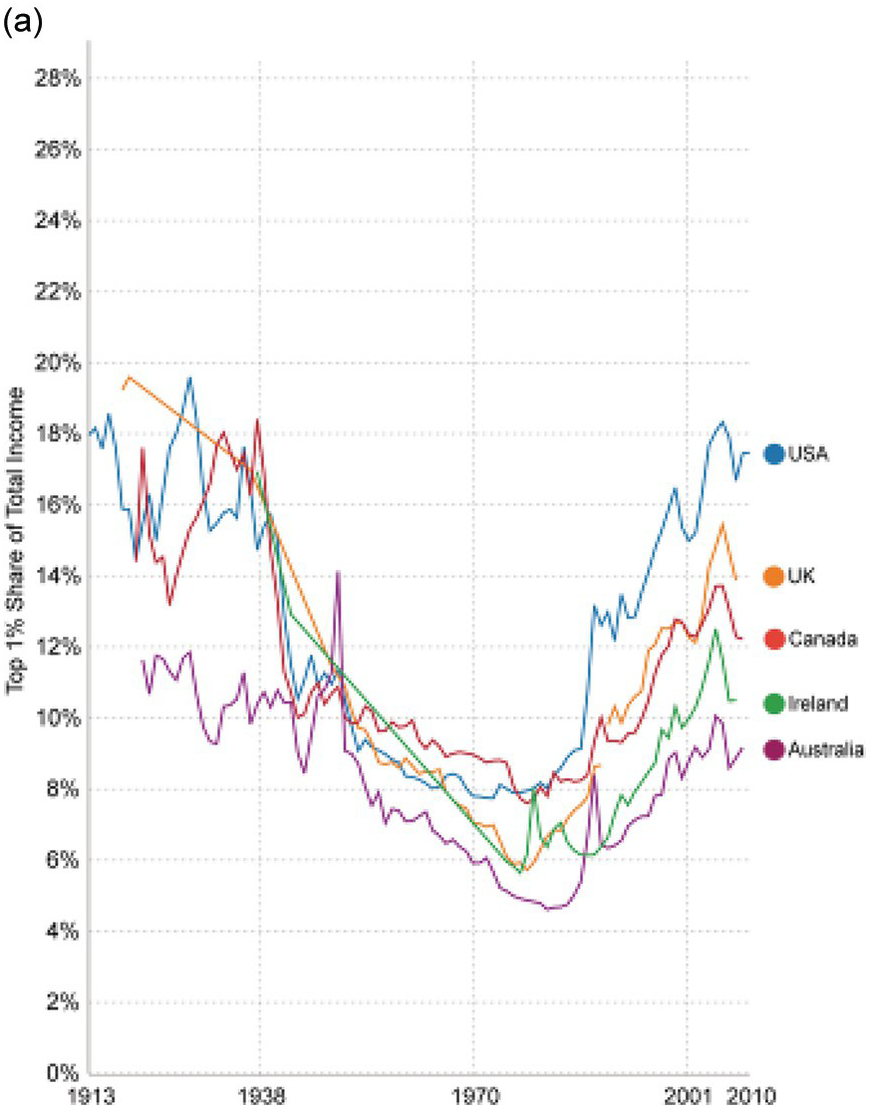

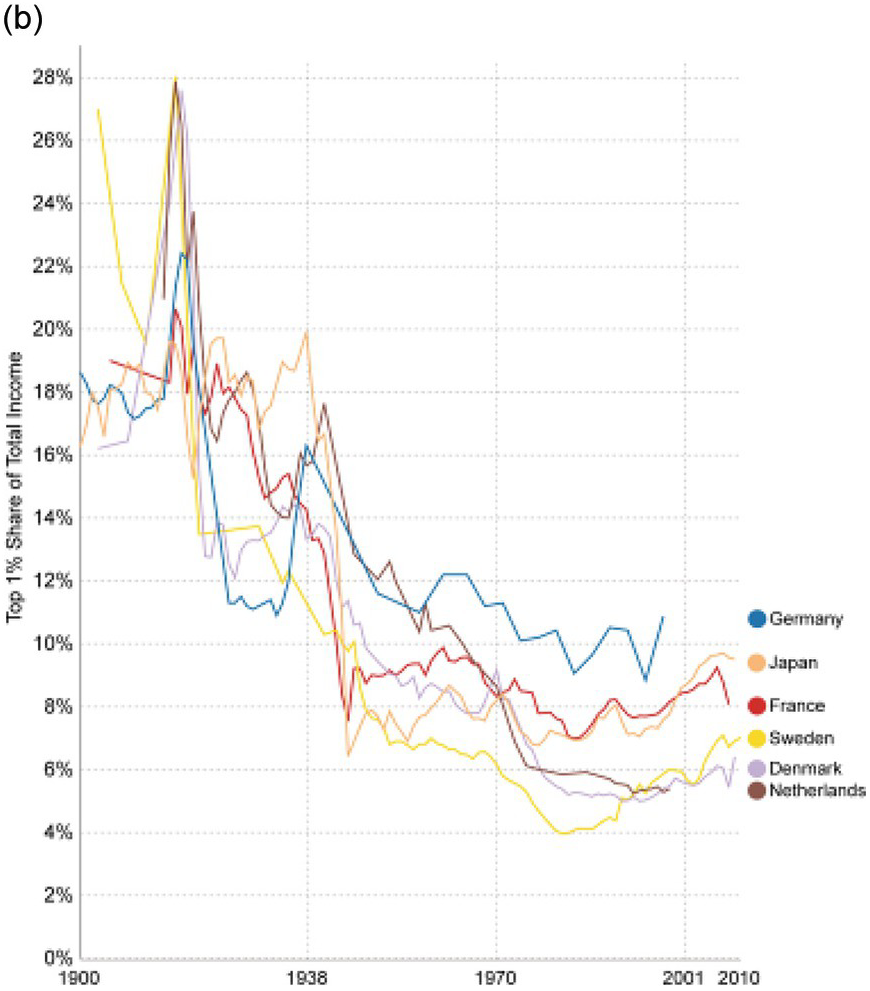

Recent publications, e.g., Piketty Reference Piketty, Saez and Stantcheva2013,2 have been drawing worldwide attention to this phenomenon, which some see as an early warning sign of major social adjustments – in the developed nations as a protest against the squeeze of the middle classes, and in developing nations as a revolution of rising expectations triggered by the fact that a small proportion of the population is getting (very) rich.

As is now discussed both in academia and in politics, the growing wealth discrepancy seems a manifest case of a societal planetary boundary that we are approaching, or have already crossed. Hence, I will use this section to discuss it at some length. To illustrate the scope of the phenomenon, I will present some statistics.3 In doing so, I use the USA and Europe as examples because there are much better data for the wealth gap here than in many other countries.

Particularly since the 1940s, income inequality in the USA has spectacularly risen, from a situation in which 90 percent of the population collectively made about 66 percent of total US income and the top 10 percent about 33 percent. At the beginning of the 1980s that trend was dramatically inverted, coinciding all too closely with the “big bang” in the New York stock exchange, a major deregulation under the Reagan government. In 2012, the top 10 percent of the population received about half the income of the USA.