Book contents

- War, States, and International Order

- Cambridge Studies in International Relations: 159

- War, States, and International Order

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Context, Reception, and the Study of Great Thinkers in International Relations

- Part I Gentili’s De iure belli in Its Original Context

- Part II Gentili’s De iure belli and the Myth of “Modern War”

- Bibliography

- Index

- Cambridge Studies in International Relations

- References

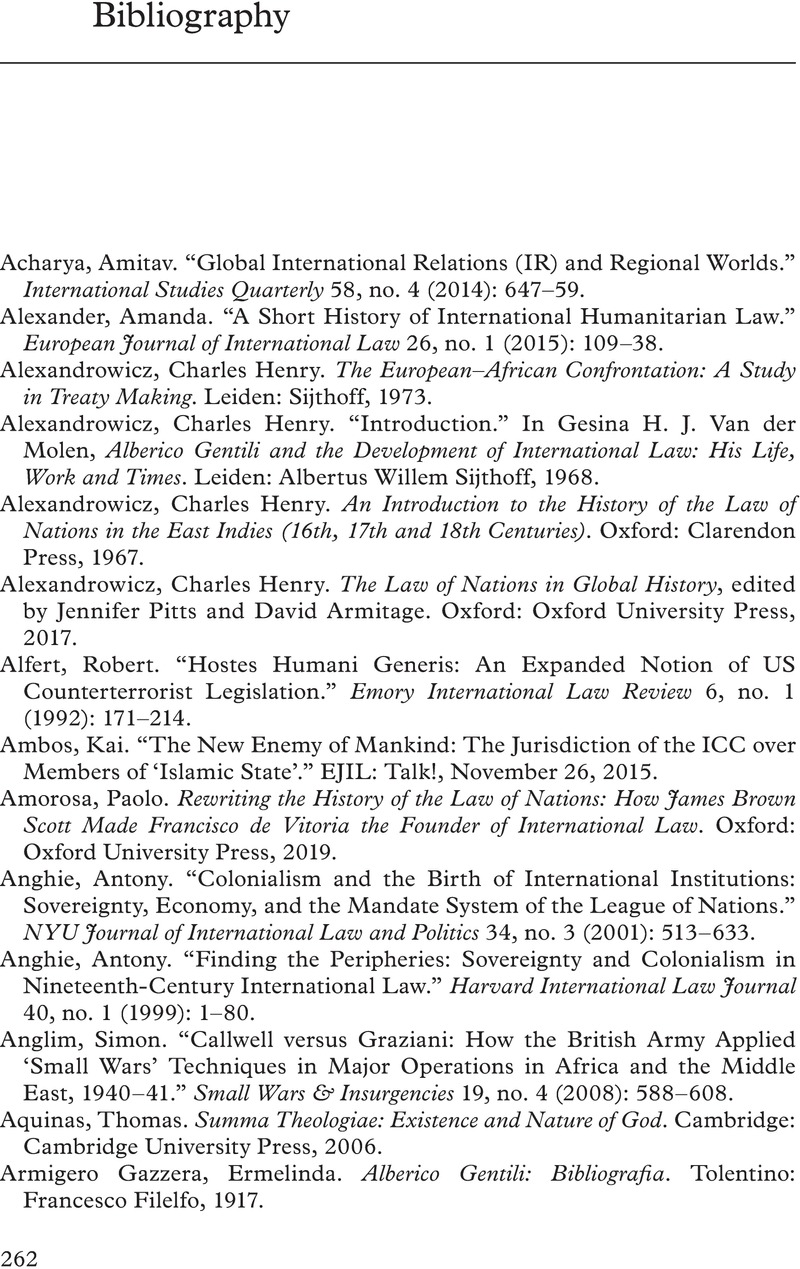

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 July 2022

- War, States, and International Order

- Cambridge Studies in International Relations: 159

- War, States, and International Order

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Context, Reception, and the Study of Great Thinkers in International Relations

- Part I Gentili’s De iure belli in Its Original Context

- Part II Gentili’s De iure belli and the Myth of “Modern War”

- Bibliography

- Index

- Cambridge Studies in International Relations

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- War, States, and International OrderAlberico Gentili and the Foundational Myth of the Laws of War, pp. 262 - 292Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022