Introduction

Ever since the first discussions over the founding of the Canadian federation, the country has faced an uneasy trade-off between accommodating diversity and promoting unity (see Cairns, Reference Cairns1992; LaSelva, Reference LaSelva1996; McRoberts, Reference McRoberts1997). This challenge has marked the country's political development and fascinated scholars of Canadian politics. Diversity in all its forms is now a key focus of Canadian politics scholarship, and one of its ramifications focuses on regional and provincial diversity in political culture. The qualitative literature on the topic is especially rich, with numerous book-length treatments of political values, beliefs and norms focused on identifying every specificity of how residents of each province relate to politics in their everyday life (Henderson, Reference Henderson2008; Lipset, Reference Lipset1950; MacPherson, Reference MacPherson1962; McRoberts, Reference McRoberts1993; Wesley, Reference Wesley2011; Wiseman, Reference Wiseman2007).

Unfortunately, the quantitative literature on the topic is much sparser. Simeon and Elkins provided a seminal contribution to the field, investigating survey data to find provincial patterns in levels of political efficacy and political trust (Elkins and Simeon, Reference Elkins and Simeon1980; Simeon and Elkins, Reference Simeon and Elkins1974). Since then, a few studies have focused on provincial differences in political efficacy and trust, taking Simeon and Elkins’ conclusions as the baseline against which to compare their results. Those studies have reached inconsistent results but typically failed to fully replicate Simeon and Elkins’ conclusions. These inconsistencies raise numerous questions, among which the validity of Simeon and Elkins’ findings comes to mind first. Indeed, the field has mostly built upon their findings without re-examining or calling them into question. Reflecting on the study of political culture in Canadian political science numerous decades after his seminal contributions with David Elkins, Richard Simeon himself lamented the lack of replication of their original work (Simeon, Reference Simeon2010). The reasons why the field might benefit from a re-examination of their findings are plentiful. Notably, the small sample sizes that the authors had to work with forced them to use simple analytical tools whose results might not be as robust as those of more recent, statistically sophisticated analyses. Further, their time frame was very small, using only data from the late 1960s and early 1970s. It is quite startling that the patterns of provincial differences in political culture that were found during such a specific period have been elevated to the status of an almost gold standard against which any subsequent results need to be compared and contextualized. As Nelson Wiseman underscored when reviewing Simeon and Elkins’ work: “Trust and efficacy appear inherently volatile, affected by current events. What people say on a given day does not necessarily or very well reflect their deeper, more stable values” (Wiseman, Reference Wiseman2007: 52). Accordingly, to identify those deeper values through survey data, one needs to focus on a longer time frame, which allows us to neutralize the impact of contextual factors—such as shifting economic conditions and support for government—and identify deep-rooted trends in trust and efficacy.

This issue is becoming glaring, as studies that replicate Simeon and Elkins’ analysis systematically find widely discrepant patterns. Using similar methods and data sources but focusing on different time periods, these studies find important—sometimes even dramatic—differences in provincial patterns of political culture. These inconsistencies suggest these studies are falling prey to the same limitation as Simeon and Elkins’ work: interprovincial comparisons are blurred by provincial contextual idiosyncrasies that studies have been unable to account for. Indeed, most studies rely on one, two or, exceptionally, three cross-sectional surveys to create a picture of political culture across the country (Baer et al., Reference Baer, Grabb and Johnston1993; Cochrane and Perrella, Reference Cochrane and Perrella2012; Elkins and Simeon, Reference Elkins and Simeon1980; Gidengil, Reference Gidengil1989, Reference Gidengil1990; Henderson, Reference Henderson2004; Héroux-Legault, Reference Héroux-Legault2016; Ornstein et al., Reference Ornstein Michael, Michael Stevenson and Paul Williams1980; Wilson, Reference Wilson1974). With such a short time frame, those studies are inherently vulnerable to the influence of contextual idiosyncrasies, as interprovincial differences could potentially be entirely spurious—that is, they could reflect different contexts rather than profound and enduring differences in political orientations.

The present article seeks to palliate the shortcomings of the literature by offering the broadest re-examination of Simeon and Elkins’ conclusions, which have guided our understanding of provincial differences in political efficacy and political trust for nearly half a century. Using survey data collected over five decades (1974–2019), this study intends to replicate the authors’ analysis as closely as possible, in order to answer three questions. First, does the Simeon and Elkins interpretation still hold when using a much larger sample, or was it dependent on the peculiarities of their small sample? Second, were their conclusions dependent on their short time frame, or do they successfully extrapolate beyond their sample? Finally, do their results hold when accounting for contextual factors that could plausibly influence political efficacy and cynicism?

The results presented in this article suggest that the image of provincial political cultures painted by Simeon and Elkins deserves to be updated. Their depiction of provincial political cultures may have been valid for the late 1960s and early 1970s, but it fails to capture provincial patterns that can be found when extending their time frame. Four key findings are worth pointing out. First, the analysis fails to find any support for the stereotype of Atlantic provinces being “disaffected” from the political process. Second, similar to Simeon and Elkins, I find a significant level of heterogeneity within western provinces. Yet, taken together, the four provinces are found to be somewhat less optimistic and trusting of the political process than Simeon and Elkins claimed. Third, Quebec appears considerably more efficacious than the authors’ depiction of the province. Finally, Ontario was described by Simeon and Elkins as particularly efficacious and trusting of the political process, but my findings suggest the province lies more toward the middle of the pack of all provinces with regard to those two characteristics.

The article starts with a brief overview of the literature on Canadian political culture. It is followed by a discussion of how the prevailing survey-based approach to studying political culture in Canada fails to yield conclusive results. The data and method used in the analysis are then presented, followed by the results of the investigation. A brief discussion of their implications concludes the article.

Interprovincial Differences in Political Culture

There are two approaches to studying Canadian political culture. The longest standing perspective is qualitative in nature and focuses on the deep-rooted and progressive impact of historical phenomena. Hartz's (Reference Hartz1955, Reference Hartz1964) fragment theory, Innis’ (Reference Innis1930) staples theory and Lipset's (Reference Lipset1968) work on formative events are pioneering work in this line of research. A second perspective relies on survey data to assess political culture, building upon the work of Almond and Verba (Reference Almond and Verba1963). Rather than probing history, their work aggregates individual political attitudes and treats them as indicators of political culture.

The two perspectives both seek to identify, describe and account for patterns of political culture. Yet they adopt distinct epistemological perspectives that warrant the different theoretical and methodological approaches they use. Simeon and Elkins’ seminal pieces (Simeon and Elkins, Reference Simeon and Elkins1974; Elkins and Simeon, Reference Elkins and Simeon1980) relied on the civic culture approach pioneered by Almond and Verba, importing the framework in Canadian political science. This approach defines political culture as a macro-level phenomenon that appears through the aggregation of a group of individuals’ basic orientations, norms, values and assumptions about politics (Elkins and Simeon, Reference Elkins and Simeon1979). It embodies a set of orientations toward the political world widely shared among its group members (Almond and Verba, Reference Almond and Verba1963).Footnote 1 Those who replicated Simeon and Elkins’ work also relied on the civic culture (quantitative) approach to studying political culture, and this study takes the same path.

Political culture is conceptualized as an enduring aspect of societies, which exerts a lifetime impact on individuals. Political culture certainly evolves over time (Almond and Verba, Reference Almond and Verba1980) but typically does so very slowly, constantly reproducing itself through each new generation of citizens (Wiseman, Reference Wiseman2007: 13). This sets it apart from public opinion: while the latter fluctuates rapidly in close connection to short-term political developments, political culture evolves only very slowly over time. Accordingly, although political attitudes can vary in reaction to salient events, a clear pattern should be discernable through the noise of short-term fluctuations. By looking for such long-term patterns, which wash away short-term fluctuations, we should be able to identify the deep-rooted differences in political culture across groups.

A variety of groups can be said to have a political culture of their own. In Canadian scholarship, the locus of attention has typically been placed on provincial and regional political cultures (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Pammett, Stewart, Archer and Young2002; Cooper, Reference Cooper, Archer and Young2002; Elkins and Simeon, Reference Elkins and Simeon1980; Fafard et al., Reference Fafard, Rocher and Côté2010; Gibbins, Reference Gibbins1980; Kornberg and Clarke, Reference Kornberg and Clarke1994; Leuprecht, Reference Leuprecht2003; McGrane and Berdahl, Reference McGrane and Berdahl2013; O'Neill and Erickson, Reference O'Neill and Erickson2003; Schwartz, Reference Schwartz1974; Simeon and Elkins, Reference Simeon and Elkins1974; Wesley, Reference Wesley2011; Wiseman, Reference Wiseman2007), although studies have also assessed political culture from a subcontinental (Baer et al., Reference Baer, Grabb and Johnston1993; Grabb et al., Reference Grabb, Anderson, Hwang and Milligan2009), national (Horowitz, Reference Horowitz1966; Lipset, Reference Lipset1990; Nevitte, Reference Nevitte1996) and gender (O'Neill, Reference O'Neill, Everitt and O'Neill2002) perspective. Some have even focused on geographically noncontiguous clusters of culture (Gidengil, Reference Gidengil1990; Henderson, Reference Henderson2004). This study builds on these important contributions but intends to provide empirical evidence to debates over provincial and regional differences in political culture. To even the most casual observer, such differences abound. Richard Simeon and David Elkins were among the first to try to precisely estimate the extent of those differences, which they grouped under the concept of “regional political cultures,” by using survey data to investigate the extent to which “the population of the Canadian provinces differ in some basic orientations to politics” (Simeon and Elkins, Reference Simeon and Elkins1974: 397; see also Schwartz, Reference Schwartz1974). Analyzing the 1965, 1968 and 1974 Canadian Election Studies (CES), the authors found wide differences across provinces with regard to their citizens’ sense of political efficacy and political trust. Both trust and efficacy were found to be particularly high in Ontario and British Columbia, whereas citizens of the Atlantic provinces exhibited much lower levels of trust and efficacy (Elkins and Simeon, Reference Elkins and Simeon1980; Simeon and Elkins, Reference Simeon and Elkins1974).

Simeon and Elkins’ work created a very sticky image of provincial political cultures. Decades later, research on the topic still tends to treat the authors’ conclusions as the baseline upon which to build empirical expectations or as the appropriate point of comparison for results (see Anderson, Reference Anderson2010; Henderson, Reference Henderson2004; Reference Henderson2010; Héroux-Legault, Reference Héroux-Legault2016; McGrane and Berdahl, Reference McGrane and Berdahl2013; O'Neill and Erickson, Reference O'Neill and Erickson2003; Wesley, Reference Wesley2015; Wiseman, Reference Wiseman2007). Yet the authors’ conclusions have been much debated, as many who addressed similar research questions using survey data found discrepant, sometimes even completely opposite, regional patterns to those identified by Simeon and Elkins (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Pammett, Stewart, Archer and Young2002; Henderson, Reference Henderson2004; McGrane and Berdahl, Reference McGrane and Berdahl2013; Ornstein et al., Reference Ornstein Michael, Michael Stevenson and Paul Williams1980; Wesley, Reference Wesley2015). Some therefore claim that the patterns identified by the authors are now outdated (Stewart, Reference Stewart1994). Others have discussed the possibility that provincial political cultures may have changed over time, in order to justify the discrepancy between their findings and those of Simeon and Elkins (Henderson, Reference Henderson2004; McGrane and Berdahl, Reference McGrane and Berdahl2013).

These inconsistencies raise questions about the ability of previous studies on the topic to identify long-term patterns of political culture. Importantly, these discrepancies could potentially be the result of extraneous factors confounding the results of those studies. Indeed, political attitudes can vary swiftly over time. As most studies rely on a short time period to conduct their analyses, they are vulnerable to mistaking contextual idiosyncrasies with enduring patterns of political culture. The first potential confounding factor that comes to mind is the economic condition of provinces, as many have identified this issue as a significant determinant of political attitudes (Cochrane and Perrella, Reference Cochrane and Perrella2012; Gidengil, Reference Gidengil1989, Reference Gidengil1990). Importantly, Gidengil's work claims that this is not merely a composition effect, as the location of one's province in the centre-periphery system is claimed to impact political attitudes independently of one's personal socio-economic status. Accordingly, while individual material status does matter in influencing political orientations, the provincial economic context also shapes citizens’ attitudes, thus fostering provincial patterns of political culture.

Partisanship constitutes another factor that could blur results across studies. Indeed, after receiving some initial pushback (see Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Jane Jenson and Pammett1984; Meisel, Reference Meisel1975), the idea that partisanship exerts the determinant influence depicted by the authors of the Michigan model (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960) has now made its way into Canadian politics (Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Neil Nevitte, Everitt and Fournier2012). Accordingly, it appears likely that varying levels of support for federal and provincial governments could contribute to profound shifts in provinces’ levels of political trust and efficacy.

This study thus accounts for these two important contextual factors (economic conditions and partisanship) to better identify the underlying patterns of political culture prevailing within each province.

Data and Methods

Two issues with earlier studies of provincial political cultures potentially account for the discrepant findings in the literature: small sample sizes and short time frames. The first issue is the most straightforward. Focusing on provincial political cultures necessarily implies stratifying one's dataset in 10 smaller provincial groups, thus substantially reducing the sample size for each province, especially the smaller ones. For example, Simeon and Elkins’ (Reference Simeon and Elkins1974) study relied on only 48 respondents from Newfoundland. Studies thus become plagued by a substantial amount of sampling variance, which has often not been considered in the literature given its focus on descriptive comparisons of provincial averages.

Some recent investigations address the issue by relying on larger sample sizes allowing researchers to use statistical tools (regression or ANOVA) to infer about provincial differences (Cochrane and Perrella, Reference Cochrane and Perrella2012; Henderson, Reference Henderson2004; McGrane and Berdahl, Reference McGrane and Berdahl2013). Yet these studies fall prey to the second limitation: their datasets are collected over short time frames. This is especially worrisome given that political culture cannot be measured directly and can only be inferred through attitudes that, aggregated together, form political culture. Unfortunately, these individual attitudes tend to exhibit high volatility, whereas the underlying political culture is, in comparison, extremely stable. Political attitudes can thus vary differently from one province to the other, in reaction to political events that are salient in each province. Accordingly, by relying on short time frames, studies cannot distinguish between idiosyncratic fluctuations in political attitudes and underlying patterns of political culture. This study intends to overcome this challenge by relying on surveys collected over a lengthy time frame, which allows idiosyncratic fluctuations in indicators of provincial political cultures to average out. In doing so, our analysis provides a quantitative estimation of political culture prevailing within each province over the whole period. Yet it also needs to be underscored that such an approach is inherently unable to identify temporal changes, as it averages out those potential changes. Accordingly, results need to be interpreted as providing a snapshot of political culture within each province for the whole period, but these results cannot necessarily be extrapolated to any individual year included in the sample. Although we expect changes in political culture to be slow and moderate, their potential occurrence cannot simply be dismissed. They constitute an extension of this analysis that I encourage others to study in order to deepen our understanding of provincial political cultures.

The empirical analysis used here relies on three datasets: the Canadian Election Study (CES),Footnote 2 the Comparative Provincial Election Project Survey (CPEPS)Footnote 3 and the Provincial Diversity Project (PDP).Footnote 4 Data for the CES cover the period 1974–2019, with a cross-sectional survey conducted for every federal election during the period, although inconsistencies in the questions included in each survey mean that some surveys are left aside for each model that is estimated.Footnote 5 The CPEPS, for its part, is a repeated cross-sectional survey covering a period from 2011 to 2015, surveying respondents of each province during one provincial election—or occasionally two provincial elections. Finally, the PDP is a cross-sectional survey that was fielded between December 2013 and February 2014 and was not tied to any election campaign. All three surveys are probabilistic and designed to be representative of their underlying population. Appendix A in the online supplementary information provides information on the sample size of each survey.

The outcome variables that are investigated were selected to reflect as closely as possible the original analysis of Simeon and Elkins (Reference Simeon and Elkins1974), in order to maximize the comparability of their results and those obtained in this re-examination of their work. I thus listed the nine survey items they use in their analysis and investigated how consistently they were asked in the datasets used in the analysis. Four items were selected based on the consistency of their presence in the surveys used. These were then grouped into three concepts: political cynicism, internal political efficacy and external political efficacy. Political cynicism is measured by combining answers to two questions, one asking respondents whether they believe that the government cares about what people like them think, and a second measuring their perception of members of Parliament losing touch with them after their election.Footnote 6 Internal political efficacy is measured by using a question asking respondents whether they think government and politics are too complicated for them to understand. Finally, external political efficacy is measured through a question asking respondents their agreement with the statement that people like them have no say about what the government does.

I slightly depart from Simeon and Elkins with regard to the conceptualization of the outcome variables. Whereas they combine their items to form two indicators of political culture (political trust and efficacy), I opted for a three-pronged approach (political cynicism, external efficacy and internal efficacy). The current analysis focuses on political cynicism rather than political trust, since the latter is conceptualized as a broad orientation toward government actions meeting (or not) citizens’ expectations (Hetherington, Reference Hetherington2005). Political cynicism, in contrast, is merely one ramification of political trust, capturing citizens’ evaluations of political officials’ integrity and individual actions (see Dancey, Reference Dancey2012: 412–13). The two indicators of political trust that were consistently asked in surveys used in the present analysis relate to politicians’ actions and integrity; thus I find it more appropriate to conceptualize the outcome variable as measuring the specific concept of political cynicism rather than the broader notion of political trust.

Finally, in contrast to Simeon and Elkins, I separate internal and external political efficacy, given that one indicator directly measured respondents’ perception of their ability to understand politics, whereas another indicator relates to their ability to have their grievances taken into consideration by elected officials. Considering the different target of the two survey items—respondents’ understanding of politics (internal efficacy) and influence on politics (external efficacy)—I find it more appropriate to keep the two items separate in order to clarify the interpretation of the results.

The main predictors of interest are the province dummy variables, which capture provincial differences in our three outcome variables of interest. I am also interested in the impact of economic conditions, as the literature suggests that poor economic conditions make citizens become more disaffected, and vice versa when conditions are good. Accordingly, measures of provinces’ unemployment and growth rate when each survey was fielded are included in the models (both measures taken from Statistics Canada's database). Socio-demographic indicators commonly used in Canadian political behaviour research are also included in the models as control variables (see Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Neil Nevitte, Everitt and Fournier2012)—age, education, gender, native language and religion. Respondents’ party identification—both at the federal and provincial levels—is also accounted for, as it seems possible that those identifying with more successful parties could be less cynical toward politics and have a greater sense of efficacy. Given the importance attributed in the literature to individuals’ early socialization context and how attitudes developed during early adulthood persist over time, an indicator capturing whether respondents were born in Canada is also included.

The analysis proceeds in three steps, taking inspiration from the approach used by Cochrane and Perrella (Reference Cochrane and Perrella2012). For each of the three outcome variables, a first model—called the base model—incorporates all the variables listed above, except for provincial economic indicators and provincial partisanship. This base model thus provides a description of interprovincial variation on each of the three outcomes when accounting for individual-level socio-demographic indicators and federal partisanship. This specification controls for a composition effect—where interprovincial differences could merely be due to the distinctive socio-demographic makeup of each province.

The base model is estimated in the following way:

where y i is one of three outcome variables and α is a constant. ${\bf Provinc}{\bf e}_{\bf i}$![]() is a vector of province dummy variables, ${\bf FedPI}{\bf D}_{\bf i}$

is a vector of province dummy variables, ${\bf FedPI}{\bf D}_{\bf i}$![]() is a vector of federal partisanship dummy variables (Liberal, Conservative, New Democrat, other or none) and ${\bf X}_{\bf i}$

is a vector of federal partisanship dummy variables (Liberal, Conservative, New Democrat, other or none) and ${\bf X}_{\bf i}$![]() is a vector of socio-demographic controls. ${\bf \lambda }_{\bf i}$

is a vector of socio-demographic controls. ${\bf \lambda }_{\bf i}$![]() represents a vector of year fixed effects, while ${\bf \gamma }_{\bf i}$

represents a vector of year fixed effects, while ${\bf \gamma }_{\bf i}$![]() constitutes a vector of survey fixed effects.

constitutes a vector of survey fixed effects.

A second model specification keeps all the covariates included in the base model but also incorporates provincial economic indicators (unemployment and growth rate). Incorporating these economic indicators in a second model specification allows us to compare our point estimates for the province dummy variables before and after accounting for economic conditions in each province. In doing so, we can evaluate whether macro-level economic factors, which have largely been overlooked in the literature, contribute to decreasing or magnifying cross-provincial differences. This approach is similar to the block-recursive modelling strategy that was pioneered by Miller and Shanks (Reference Miller and Merrill Shanks1996) and that has become commonplace in voting behaviour analyses, including within Canadian political science (see Anderson and Stephenson, Reference Anderson, Stephenson, Anderson and Stephenson2010; Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Neil Nevitte, Everitt and Fournier2012).

Accounting for provincial economic conditions is critical, given that there are systematic differences in the performance of provincial economies and such differences could potentially translate into differences in political outlooks. Yet political culture relates to deeply held beliefs and values independent of contextual circumstances. Considering how the literature on Canadian provincial political cultures puts a lot of emphasis on diverging economic conditions to account for interprovincial variation in political culture, it is worth investigating exactly how economic conditions contribute to such variation.

The second model takes the following form:

where provincial unemployment and growth rates are added to the base model.

Finally, a third model incorporates provincial party identification. While most of the observations used come from the CES, which is conducted during federal election campaigns and focuses mostly on national politics, the survey items used never refer explicitly to “federal” governments and politicians. It thus seems possible that citizens who identify with their provincial government might have a generally more optimistic outlook on politics that could carry over to the three outcome variables. Further, the CPEPS was fielded right after provincial elections, which might have primed respondents to think about provincial politics when answering it.

Provincial party identification (PID) is left aside until the third model, given that provincial party identification is asked inconsistently in the CES, and thus incorporating it considerably decreases the number of surveys included in the analysis, which makes the estimates less robust to idiosyncratic fluctuations.

The third model is estimated as follows:

where provincial partisanship is added to the list of covariates. The latter variable is operationalized as a binary variable indicating whether the respondent identifies with the party that formed the government in their province when they were interviewed.

The inclusion of economic conditions and provincial partisanship in the models allows this study to expand upon the original analysis conducted by Simeon and Elkins (Reference Simeon and Elkins1974) and its subsequent replication by others (Henderson, Reference Henderson2010; McGrane and Berdahl, Reference McGrane and Berdahl2013). Using a much shorter time frame, the authors could not test the potential impact of these two important factors on provincial differences in political culture. In doing so, this study can paint a clearer picture of each province's underlying political culture, filtering away the potentially substantial impact of contextual factors that might bias the results.

Whereas the PDP and CPEPS surveyed respondents only once, most CES surveys used in the analysis incorporated three waves (campaign-period, post-election and mailback surveys), where respondents to the campaign-period survey were recontacted for both the post-election and mailback surveys. Some questions used were asked in the post-election or mailback surveys, which tend to have lower response rates. Given that answering the post-election and mailback surveys is unlikely to be randomly determined, the analysis cannot assume that observations are all independent and identically distributed, which invalidates some of the assumptions on which test statistics rely in regression analysis. To address this issue, bootstrapped standard errors are used instead of the conventional asymptotic standard errors.Footnote 7 This more conservative approach relaxes the assumption of random sampling while providing more robust estimates of the uncertainty surrounding our regression coefficients.

Finally, an important methodological caveat needs to be addressed. When pooling multiple surveys, one needs to be aware of the possibility that peculiarities of each survey (such as sampling design, question wording, answer choices or sample size) could be driving the results. Several precautions were taken to alleviate this risk in the present study. First, only surveys whose question wording and answer choices were directly comparable were used. The coding of the answers was also standardized to ensure comparability.Footnote 8 Further, I rely on a two-way fixed effects strategy using both survey and year fixed effects, which models heterogeneity across time and surveys to prevent it from driving the results. The survey fixed effects are designed to capture the possibility that each of the three surveys (CES, CPEPS and PDP) could yield systematically higher or lower measures of the outcome variables, which could bias our results if unaccounted for. The year fixed effects are intended to capture the fact that political cynicism and political efficacy could systematically vary over time across the country and also potentially bias the estimates of interest. The two-way fixed effects strategy thus allows the models to distinguish between federal, provincial and survey-level variations in each outcome variable. In doing so, the analysis can distinguish between long-term patterns and idiosyncratic fluctuations. Finally, a leave-one-out analysis (results not shown) was conducted, where the models presented in the main text were estimated leaving out one survey at a time, to determine how sensitive to the inclusion of a given survey are to the results presented. The results unsurprisingly suggested some sensitivity to the 2019 CES, given its much larger sample size than other surveys. To resolve the issue, the two models that use data from the 2019 CES (both political efficacy models, as questions measuring political cynicism that are used in the analysis were not asked in the 2019 CES) were re-estimated using only a random subset of a quarter of the full 2019 CES sample. In doing so, we substantially reduce the weight of the 2019 CES on the results, bringing it in line with the weight of most other surveys. The results of this alternative specification are presented in Appendix E in the online supplementary information and mentioned in the main text whenever their interpretation differs from that of the results using the full sample.

Results

Regression results are presented using dotplots.Footnote 9 For each outcome variable, the results of all three model specifications are incorporated in a single plot to better visualize how the inclusion of additional covariates influences the results for province indicators. Ontario is used as the baseline for the provincial dummy variables, given the pervasive claim that it represents the archetypal Canadian province (Krause, Reference Krause, Krause and Wagenberg1995), which makes it a natural point of comparison. The results are separated in two facets, one displaying point estimates for the macro-level variables (provincial indicators and economic conditions) and another displaying point estimates for the individual-level variables (partisanship and socio-demographic indicators). The unemployment rate and economic growth variables have been standardized such that their mean is 0 and have unit standard deviations. Their coefficients can thus be interpreted as the impact of a one standard deviation increase in unemployment/growth. All other variables are binary; thus the magnitude of their point estimates can be directly compared.

Results of regression models predicting levels of political cynicism are shown in Figure 1. The results for individual-level variables appear to be robust to all three model specifications, which is not the case for the province indicators. Cross-provincial differences in levels of political cynicism appear modest in the base model specification (light grey). Including provincial economic conditions changes the patterns found in the base model specification, as some provinces (Alberta and the Atlantic provinces) become increasingly dissimilar to our baseline province, Ontario, while others’ distinctiveness fades away (Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Quebec). This result suggests that provincial economic conditions have a non-negligible impact on provincial levels of political cynicism, as it can either mask or enhance cross-provincial variation. This finding is in line with the widespread claim in the literature that economic conditions substantially contribute to shaping citizens’ outlook on politics (Gidengil, Reference Gidengil1989, Reference Gidengil1990). Incorporating provincial PID in the mix further reinforces the aforementioned pattern, as provinces whose point estimate was substantially altered by the inclusion of the macroeconomic variables all see a similar change of their point estimate—in the same direction—when incorporating provincial PID in the model. Simply put, including economic conditions in the model seems to better identify the deep-rooted time-invariant trends in provincial political culture that are not due to contextual factors such as good or bad economic conditions. Incorporating provincial PID furthers our ability to identify such deep-rooted trends, as it also filters away from the results the (seemingly substantial) impact that having one's preferred provincial party in power can have on political cynicism.

Figure 1 Regression results, impact of covariates on political cynicism index. Dots represent point estimates with .05 confidence intervals based on bootstrapped standard errors. Year and survey fixed effects are included in the models but not shown.

Interestingly, the results appear to contradict the claim that citizens of the Atlantic provinces are more politically disaffected than other Canadians. All else equal, respondents from Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland even appear to be the least cynical of all respondents. In contrast, respondents from the three Prairies provinces appear to be the most cynical when compared to the baseline province, Ontario. These results slightly contrast with those of others who found the Prairies provinces to be located in the middle of the pack in terms of political cynicism (Henderson, Reference Henderson2010; McGrane and Berdahl, Reference McGrane and Berdahl2013; Simeon and Elkins, Reference Simeon and Elkins1974) but are consistent with those found by Jared Wesley and his colleagues (Wesley, Reference Wesley2015). It is important to underscore that this finding is not merely the result of recent political developments, as all three models incorporate surveys going at least as far back as 1993. The questions used to form our political cynicism index also refer to abstract political concepts (“those elected” and “the government”), which further suggests that these results reflect genuine differences in political cynicism and do not simply capture attitudes about the way the federation operates (such as equalization payments) or a specific political context (the Trudeau government, for example).

Turning to Ontario (the baseline province), the results contradict those of Simeon and Elkins (Simeon and Elkins, Reference Simeon and Elkins1974; Elkins and Simeon, Reference Elkins and Simeon1980), who found it to score high on political trust, and also those of McGrane and Berdahl (Reference McGrane and Berdahl2013), who found it to score very low. The results of my analysis suggest a middle ground, as roughly half of provinces score higher than Ontario on political cynicism, with the other half scoring lower. This result echoes Ailsa Henderson's (Reference Henderson2010) findings.

Looking at the two variables capturing provincial economic conditions, higher rates of unemployment are found to be associated with greater political cynicism, whereas growth does not appear to have a substantial impact on political cynicism. This result possibly relates to the fact that higher unemployment leads individuals to develop a sense of hopelessness (Eisenberg and Lazarsfeld, Reference Eisenberg and Lazarsfeld1938), whereas growth potentially does not have such a large impact on individuals’ attitudes, given its less perceptible effect on citizens’ daily lives.

Interestingly, when looking at individual-level variables, partisanship—both federal and provincial—stands out as having a sizable impact on political cynicism. Respondents who identify as Conservatives (the baseline condition) or Liberals score lower on political cynicism than those who identify as New Democrats, while those who identify as supporters of other parties and as independents score the highest on political cynicism. This is likely a reflection of the fact that Liberals and Conservatives have the greatest access to federal political power, as only iterations of those two parties have formed governments in the last century. Although the New Democratic Party (NDP) never held power at the federal level, it is a very stable and well-established third party, thus potentially explaining its supporters holding the middle ground in terms of political cynicism. Independents and supporters of other parties, for their part, possibly feel more poorly represented by their country's political system, which could translate into higher rates of political cynicism. The impact of provincial partisanship is consistent with this interpretation, as those who identify as supporters of the party forming the government in their province display much lower levels of political cynicism than those who do not identify with the governing party.

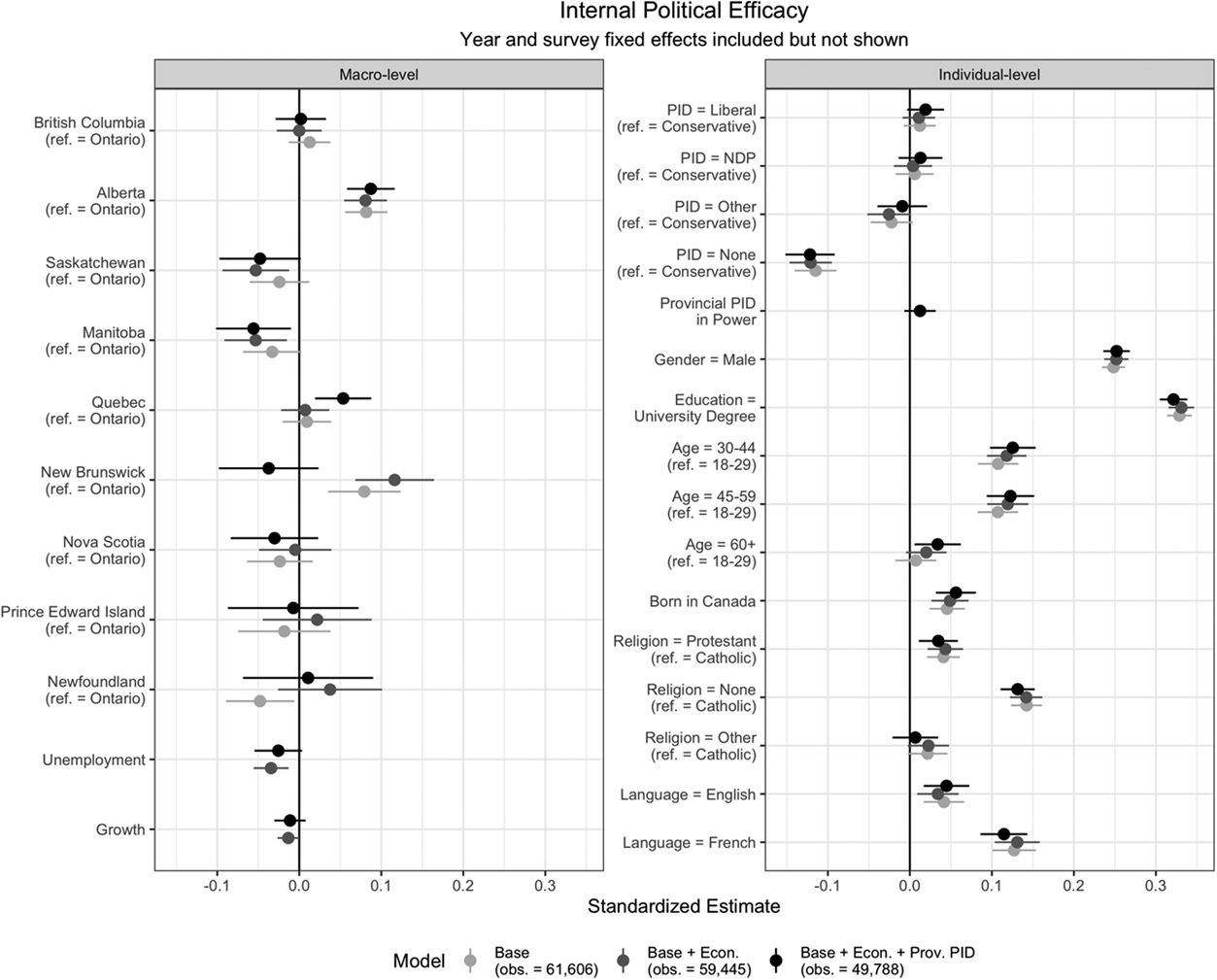

Figure 2 presents the results of models focused on internal political efficacy. Interestingly, this time the estimates for the province dummies are much less swayed by the incorporation of macroeconomic variables and provincial PID. Indeed, looking at the point estimates for the province indicators, there are only two estimates that change noticeably across model specifications: those of Quebec and New Brunswick. The greater stability of the estimates is likely due to internal political efficacy being less related to an individual's political environment and having more to do with an individual's cognitive abilities and self-confidence. This interpretation is consistent with the fact that individual-level variables—most notably education, gender, age, religion and language—have the largest impact on predicted levels of internal political efficacy. Interestingly, partisanship once again has a strong impact, yet it seems to operate somewhat differently than it did in the previous model. All partisan groups except the independents are not clearly distinct from the baseline category of Conservatives. Only independents are distinct, scoring much lower on internal political efficacy than all other partisan groups. This is likely due to the latter group lacking the partisan heuristic to make sense of political events (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960; Kam, Reference Kam2005; Lenz, Reference Lenz2009; Popkin, Reference Popkin1991; Schaffner and Streb, Reference Schaffner and Streb2002).

Figure 2 Regression results, impact of covariates on internal political efficacy. Dots represent point estimates with .05 confidence intervals based on bootstrapped standard errors. Year and survey fixed effects are included in the models but not shown.

Returning to the province indicators, the overwhelming conclusion appears to be that respondents of all provinces display similar levels of internal political efficacy. Only Albertans are consistently different from the baseline condition, expressing higher levels of internal political efficacy. This is arguably a reflection of what some have labelled its “populist” political culture (Pickup et al., Reference Pickup, Anthony Sayers and Archer2004: 634; Stewart and Archer, Reference Stewart and Archer2000: 13–15) that favours mechanisms of direct democracy over elite-centric processes. Respondents from New Brunswick initially display the same pattern, yet the difference vanishes in the third model specification. Overall, the provinces appear to be very similar to each other, with most differences being statistically or substantively inconsequential.

Figure 3 shows the final set of results, this time focusing on external political efficacy. This third outcome variable is of particular interest, since it captures respondents’ perception of having the ability to influence political decision making, a core feature of democracy. Also, it relates to a central topic in the literature on provincial political cultures, as many have debated whether some provinces feel left out of the political process more than others (see Wesley, Reference Wesley2015; Wiseman, Reference Wiseman2007). The patterns we notice across model specifications are comparable to those found when investigating political cynicism, as once again point estimates for the province dummies are substantially affected by the inclusion of additional covariates. In fact, the major differences lie in the results for three of the Atlantic provinces—Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland. The results from the base model suggest that these three provinces are not significantly different from our baseline province, Ontario, but incorporating economic conditions and provincial PID in the model substantially alters this result, as they display much higher levels of external political efficacy. Our alternative specification using only a subset of the 2019 CES—shown in Appendix E in the online supplementary information—provides a substantively similar result, yet the magnitude of the difference between the three provinces and the baseline province (Ontario) is substantially smaller. Nevertheless, no support is found for the widespread claim that Atlantic provinces are more disaffected from the political process than other provinces (see, for example, Henderson, Reference Henderson2010; Simeon and Elkins, Reference Simeon and Elkins1974; Elkins and Simeon, Reference Elkins and Simeon1980).

Figure 3 Regression results, impact of covariates on external political efficacy. Dots represent point estimates with .05 confidence intervals based on bootstrapped standard errors. Year and survey fixed effects are included in the models but not shown.

The point estimates for other provinces are not as strongly affected by the inclusion of additional covariates and, importantly, are not as consistent within regions. The other major takeaway from the results of this analysis concerns Quebec, which scores higher than most other provinces in levels of external efficacy, a result that is consistent across all model specifications. This finding is of particular importance, as Quebec's constitutional grievances do not appear to translate into a lower sense of external political efficacy—quite the opposite in fact.

Turning to western provinces, Saskatchewan and British Columbia appear to be less confident in their ability to be heard by politicians, but not Alberta and Manitoba. Taken together, western provinces appear to feel somewhat less efficacious than other regions, which contrasts with the findings of Simeon and Elkins (Reference Simeon and Elkins1974) and those of Henderson (Reference Henderson2010), who found that respondents from the region—along with those from Ontario—expressed the highest levels of efficacy. The estimates noticeably change across model specifications for two of the four provinces (British Columbia and Saskatchewan), but not profoundly so. Including economic factors and partisanship in the model once again reveals hidden patterns, as British Columbia and Saskatchewan are found to be less efficacious than our baseline category, Ontario, but the results are more inconsistent within the region than those of Atlantic Canada. Indeed, similar to our analysis of internal efficacy, nontrivial within-region differences are found, as respondents from Saskatchewan, and to a lesser extent those from British Columbia, express noticeably lower levels of efficacy than respondents from Alberta and Manitoba.

Looking at other covariates of interest, it is worth mentioning that higher unemployment rates are associated with lower levels of political efficacy. This result sheds light on the findings for Atlantic provinces, as the lower levels of political efficacy that some authors have attributed to them could potentially be due to economic hardships experienced by some of their citizens. Under similar economic conditions, residents of the Atlantic provinces might in fact be more confident in their ability to influence the political process than residents of Ontario and the western provinces.

Once again, partisanship seems to play a critical role in expressed levels of external political efficacy. Respondents who identify as partisans of any party are significantly more likely than independents to express high levels of efficacy, potentially because independents lack a partisan vehicle to channel their grievances in Ottawa. Interestingly, provincial partisanship does not have such an impact. This is potentially due to the bulk of the observations coming from the CES, which is conducted during federal election campaigns and likely primed the respondents to think about the federal government when answering the question, and thus made them differentiate between their sense of efficacy at the provincial and federal levels.

Results of models replacing province indicators with region indicators are shown in Appendix F in the online supplementary information. These results are consistent with the interpretation above, although they mask meaningful within-region variation and can thus make political culture appear artificially homogenous within regions.

Discussion

The analysis presented above challenges many claims made by Simeon and Elkins that have become firmly grounded in the provincial political cultures literature. First, I do not find any support for the depiction of Atlantic citizens as “disaffected” from the political process (Henderson, Reference Henderson2010; Simeon and Elkins, Reference Simeon and Elkins1974; Elkins and Simeon, Reference Elkins and Simeon1980). Similar to McGrane and Berdahl (Reference McGrane and Berdahl2013: 487), I find that depictions of Atlantic Canadians as politically disaffected are likely spurious, as accounting for important complementary determinants of political attitudes—economic conditions and partisanship—makes such stereotypical images unravel. The results presented in this article thus support the claim that this “mythology” is outdated (Stewart, Reference Stewart1994; Wesley, Reference Wesley2015), as Atlantic provinces are less cynical toward politics than other provinces and do not score lower on internal and external political efficacy. Recent research suggests that political culture in the region is “converging” with that of mainstream Canada (Adamson and Stewart, Reference Adamson, Stewart and G2001), and the results obtained in the present article support this claim.

As for western provinces, some patterns emerge (higher cynicism, lower external efficacy), but we find significant within-region differences for each of the three outcome variables. These differences among western provinces are substantial enough to call into question the notion of a regional western political culture, or even Prairie political culture. A lot has been written about western Canada's political culture, with many studies using survey data stressing the region's homogeneity (Berdahl and Gibbins, Reference Berdahl and Gibbins2014; Henderson, Reference Henderson2010: 477; McGrane and Berdahl, Reference McGrane and Berdahl2013). Based on my analysis of political cynicism and efficacy, I do find some commonalities across the region, yet those are much less consistent than commonalities found in Atlantic provinces. Simeon and Elkins, in their seminal investigations on the topic, also found a moderate level of internal consistency within the western region (Elkins and Simeon, Reference Elkins and Simeon1980; Simeon and Elkins, Reference Simeon and Elkins1974). Notably, my analysis finds western Canadians to be somewhat more critical of politics than did Simeon and Elkins’ analysis, but the difference here is not as sharp as that regarding Atlantic provinces.

The results regarding Quebec are also worthy of being mentioned. Although the literature discussing the province's place in Canada focuses extensively on its unaddressed grievances and general dissatisfaction with the structure of Canadian federalism (for example, McRoberts, Reference McRoberts1997), it is interesting to note that Quebecers nevertheless express higher levels of external political efficacy than most other Canadians. This finding conflicts with previous survey-based analyses which found Quebec to score lower on political efficacy (Elkins and Simeon, Reference Elkins and Simeon1980; McGrane and Berdahl, Reference McGrane and Berdahl2013; Simeon and Elkins, Reference Simeon and Elkins1974).Footnote 10 Importantly, this result is not merely related to a potential linguistic difference in the wording of the question, as respondents’ native language is accounted for in all models. Rather, it is possibly due to Quebecers’ tendency to ascribe greater importance to their provincial government than do most other Canadians.Footnote 11 With only one survey explicitly linking the external efficacy question to the federal government, the bulk of respondents included in the analysis were free to pick whether they consider any government responsive to their demands. In Quebec, pro-sovereignty respondents are likely to think about the provincial government and its ability to represent their grievances, and their federalist counterparts are likely to think about the federal government. Accordingly, considering the historical importance of the question nationale in Quebec politics (see Pelletier, Reference Pelletier2012), respondents on both sides of the issue have the opportunity to feel represented by either the provincial or federal government.Footnote 12 This might explain why the protracted constitutional grievances of many Quebecers translate into a counterintuitively high level of external political efficacy.

Finally, the results for Ontario support the claim that the province is quite representative of Canada at large (Krause, Reference Krause, Krause and Wagenberg1995), at least with regard to our three outcome variables of interest. In each model, Ontario falls in the middle of the pack, not scoring particularly high or low on political cynicism and efficacy. This intuitive finding remains important to mention, as Simeon and Elkins (Reference Simeon and Elkins1974) found the province to be both very efficacious and trusting, a pattern that the analysis presented in this article fails to replicate.

The three-step approach used in this study allows us to visualize how much of the provincial and regional differences are accounted for (or hidden) by economic conditions and provincial partisanship. The results are striking. Accounting for economic conditions, and then accounting for provincial partisanship, reveals regional patterns in political cynicism that were otherwise hidden. It is only by doing so that we notice Atlantic residents’ lower levels of political cynicism and Prairies residents’ higher levels of cynicism. Similarly, regional patterns of external political efficacy are also revealed by this approach. Yet these results do not exactly align with the previous literature on the topic, which claims that economic differences across Canadian provinces drive differences in political culture (Gidengil, Reference Gidengil1989, Reference Gidengil1990). The results presented in this article instead suggest that economic differences hinder interprovincial differences in political culture. Indeed, provinces’ political outlooks seemed more similar before controlling for economic conditions. The findings obtained through this three-step process underscore how political attitudes used to measure political culture are influenced by a variety of contextual factors. Economic conditions constitute one such important factor, as experiencing unemployment—either directly or indirectly through the fear of being laid off in the wake of decreased economic activity—can influence the political outlook of a substantial number of citizens, enough so to mask the underlying political views prevailing within a province. The popularity of governments can also have a similar impact: if citizens from a province are overwhelmingly supportive of a government, it can artificially make the aggregated political outlook prevailing in their province appear more positive than it truly is. Accordingly, when researchers try to assess provincial political cultures, failing to account for such factors could potentially lead them to inaccurate conclusions.

Conclusion

The survey-based literature on provincial political cultures has extensively relied on Simeon and Elkins’ conclusions over the last decades. In this article, I claimed that it was necessary to re-examine those conclusions, as issues of small sample size and short time frame raise concerns over the capacity of their findings to extrapolate beyond their sample. This study has therefore replicated as closely as possible the authors’ original analysis, albeit relying on a much expanded dataset and incorporating into the analysis new contextual factors that Simeon and Elkins could not account for. The results differ markedly from Simeon and Elkins’ conclusions on numerous grounds. When provincial economic context and partisanship are incorporated into the analysis, the image of the disaffected Atlantic provinces unravels. So does the image of the particularly optimistic and trusting Ontario, whereas Quebec is found to be more efficacious than the authors claimed it to be. One key finding from Simeon and Elkins is successfully replicated: western provinces show a great deal of internal heterogeneity.

In concluding this article, I would like to acknowledge that political culture is a complex ensemble of political attitudes, values, beliefs and norms. To replicate Simeon and Elkins’ analysis, this study focused on only three such attitudes, but there are many more ramifications of political culture that were left unaddressed. I invite scholars to build on this study by incorporating other facets of political culture to broaden our understanding of it. Further, this project has provided a snapshot of provincial political cultures over the last five decades but has not investigated temporal changes in those patterns. Given the prevalence of discussions of temporal changes within the literature, I also invite scholars to find ways of assessing such changes using a similar strategy that neutralizes the influence of contextual factors. Finally, the analysis presented in this article has failed to distinguish between cynicism and efficacy toward provincial and federal governments. Doing so could contribute to further refine our understanding of the provincial differences uncovered in this article.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423923000124

Competing interests

The author declares none.