Major Incidents, Pandemics and Mental Health

Major Incidents, Pandemics and Mental Health Book contents

- Major Incidents, Pandemics and Mental Health

- Major Incidents, Pandemics and Mental Health

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Boxes

- Contributors

- Foreword by Dr Adrian James

- Foreword by Professor David Lockey

- Section 1 The Nature and Impacts of Twenty-First-Century Healthcare Emergencies

- Section 2 Clinical Aspects of Traumatic Injuries, Epidemics, and Pandemics

- Section 3 The Role of the Public in Emergencies: Survivors, Bystanders, and Volunteers

- Section 4 Responses to Meet the Mental Health Needs of People Affected by Emergencies, Major Incidents, and Pandemics

- Section 5 Sustaining and Caring for Staff During Emergencies

- Section 6 Designing, Leading, and Managing Responses to Emergencies and Pandemics

- Section 7 Key Lessons for the Way Forward

- A Glossary of Selected Key Terms Used in This Book

- Index

- References

Section 4 - Responses to Meet the Mental Health Needs of People Affected by Emergencies, Major Incidents, and Pandemics

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 January 2024

- Major Incidents, Pandemics and Mental Health

- Major Incidents, Pandemics and Mental Health

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Boxes

- Contributors

- Foreword by Dr Adrian James

- Foreword by Professor David Lockey

- Section 1 The Nature and Impacts of Twenty-First-Century Healthcare Emergencies

- Section 2 Clinical Aspects of Traumatic Injuries, Epidemics, and Pandemics

- Section 3 The Role of the Public in Emergencies: Survivors, Bystanders, and Volunteers

- Section 4 Responses to Meet the Mental Health Needs of People Affected by Emergencies, Major Incidents, and Pandemics

- Section 5 Sustaining and Caring for Staff During Emergencies

- Section 6 Designing, Leading, and Managing Responses to Emergencies and Pandemics

- Section 7 Key Lessons for the Way Forward

- A Glossary of Selected Key Terms Used in This Book

- Index

- References

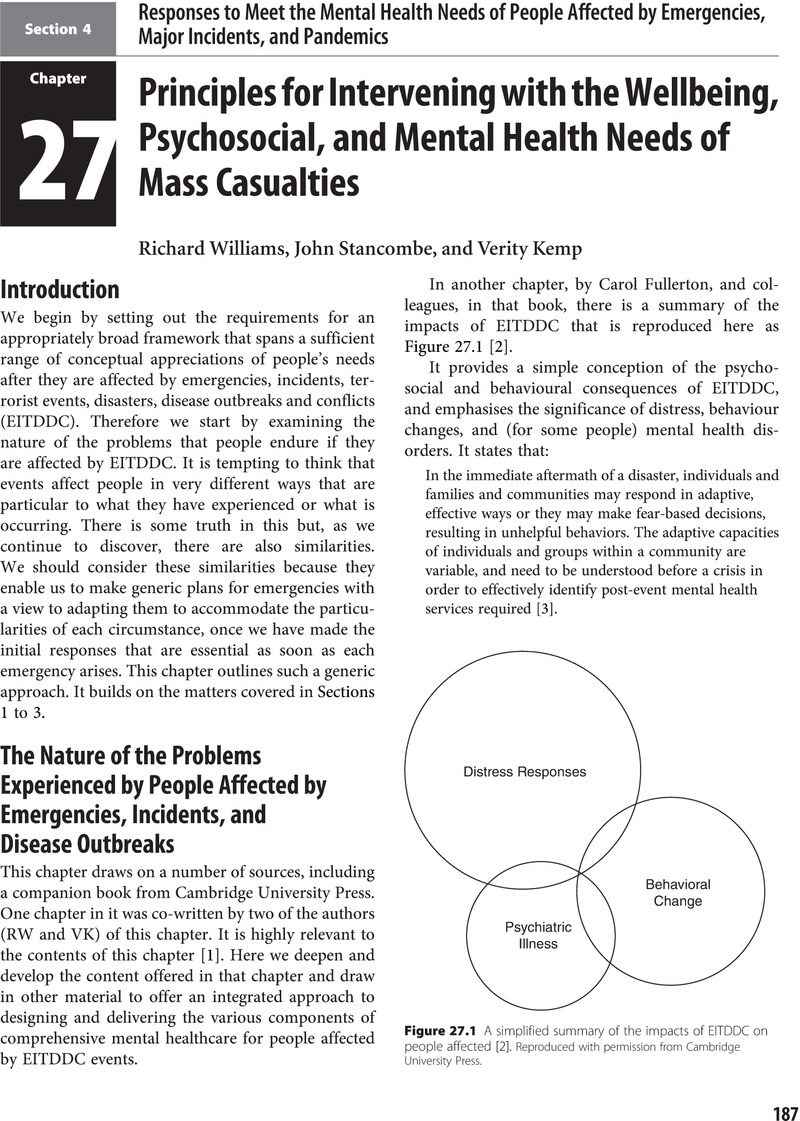

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Major Incidents, Pandemics and Mental HealthThe Psychosocial Aspects of Health Emergencies, Incidents, Disasters and Disease Outbreaks, pp. 187 - 272Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2024